Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A Subsection Sample Shifts in Relational Orientation

1.2. Psychological Dimensions and Theoretical Deconstruction of Situationship

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Relational Uncertainly and Low-Commitment Relationships as Chronic Stressors

2.2. Adult Attachment a Driver of Insecurity in Situationships

2.3. Defining Situationships and Their Core Psychological Dimensions

2.4. Relational Ambiguity and Its Consequences for Psychological and Relational Well-Being

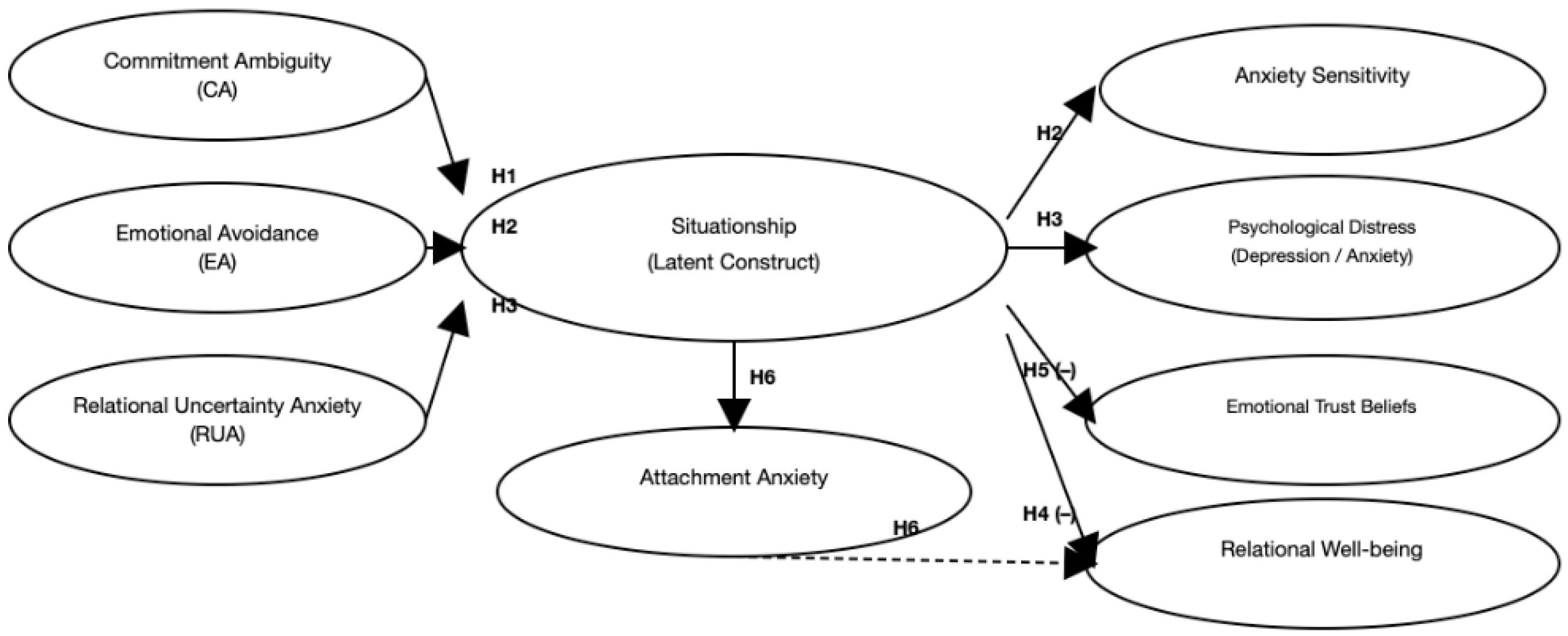

2.5. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Criterion Variables and Theoretical Rationale

3.4. Data Collection and Analytic Strategy

4. Expected Result

References

- Akbulut, Y.; Weger, H. Relational uncertainty and emotional responses in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2015, 32(6), 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V.; D’Aniello, G. E.; Fiorilli, C. Attachment insecurity, emotion regulation, and psychological distress in emerging adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2022, 39(4), 1032–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment 1995, 7(3), 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collibee, C.; Furman, W. Quality, confusions, and commitment in dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence 2015, 43, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W. A.; Horn, E. Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Handbook of Adolescence 2018, 2, 503–528. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżowska, N.; Gurba, E.; Czyżowska, D. Psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction in young adults. Health Psychology Report 2020, 8(3), 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, R. M.; LeFebvre, L.; Crook, B. Relational uncertainty, anxiety, and ambiguity in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2019, 36(11–12), 3676–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. F. Scale development: Theory and applications, 4th ed.; Sage, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Valente, G.; Bellizzi, F. Jealousy and relational ambiguity in romantic contexts. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 8456–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Mosquera, C.; Guzman, M.; Gómez, A. Emotional avoidance and intimacy regulation in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2022, 39(8), 2374–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Galdiolo, S.; Mikulincer, M. Attachment anxiety and emotional insecurity in ambiguous relationships. Personality and Individual Differences 2024, 213, 112356. [Google Scholar]

- Fahs, B.; Munger, K. Sex, love, and emotional regulation in noncommitted relationships. Journal of Social Issues 2015, 71(4), 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R.; Wegener, D. T. Exploratory factor analysis; Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley, R. C.; Waller, N. G.; Brennan, K. A. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2000, 78(2), 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T. R. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods 1998, 1(1), 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis. Structural Equation Modeling 1999, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrieri, R. C.; Margentina, J. Anxiety sensitivity and relational uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2017, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K.; Li, N. P.; Webster, G. D.; Schmitt, D. P. The dark triad and relationship preferences. Personality and Individual Differences 2015, 86, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindelberger, C.; Lydon, J. E.; Rholes, W. S. Commitment ambiguity and relational instability. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2020, 37(6), 1756–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mabilia, D.; Zaccagnino, M.; Biasi, V. Romantic stress and psychological distress in young adults. Psychology of Relationships 2019, 9(2), 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P. R. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.; Hawkley, L. C.; Cacioppo, J. T. Attachment anxiety and emotional insecurity in ambiguous relationships. Journal of Personality 2024, 92(1), 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, J. E.; Williams, K.; Ford, J. Public recognition and relational ambiguity in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2021, 38(9), 2687–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Segovia, J.; Rios, K.; Serrano, P. Attachment avoidance and emotional regulation strategies. Personality and Individual Differences 2019, 148, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocchi, N.; Cheli, S.; Cadorin, L. Trust beliefs and emotional security in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2020, 37(2), 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, H.; Henry, W.; Flynn, M. Ambiguous commitment and relational uncertainty in emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research 2021, 36(4), 468–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review 1986, 93(2), 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Wetzel, A. Factor analysis: A means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. International Journal of Medical Education 2020, 11, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-León, J.; Caycho-Rodríguez, T. The use of composite reliability and AVE in scale validation. International Journal of Psychological Research 2017, 10(2), 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, R. L.; Whittaker, T. A. Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist 2006, 34(6), 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Dimension | Sample Item | Measurement Focus | Font size and style | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CA | We have never clearly discussed our future together. | Lack of future planning | Powell, Henry, & Flynn (2021) | ||

| 2 | CA | We have never clearly discussed our future together. | Low social visibility and public recognition | Norris, Williams, & Ford (2021) | ||

| 3 | CA | There is little to no long-term planning in this relationship. | Avoidance of long-term commitment | Kindelberger, Lydon, & Rholes (2020) | ||

| 4 | CA | There is no clear agreement about exclusivity between us. | Absence of exclusivity | Fahs & Munger (2015) | ||

| 5 | CA | I feel uncertain about how to define our relationship. | Ambiguity of relationship status | Powell et al. (2021) | ||

| 6 | CA | We rarely talk about activities we might do together in the future. | Avoidance of future-oriented discussion | Collins & Horn (2018) | ||

| 7 | CA | I am unsure how long this relationship will last. | Uncertainty about relationship continuity | Collins & Horn (2018) | ||

| 8 | CA | I tend to avoid labeling this relationship clearly. | Avoidance of relationship definition | Jonason et al. (2015) | ||

| 9 | CA | My emotional investment feels disproportionate to the formality of this relationship. | Imbalance between emotional investment and commitment | Sternberg (1986) | ||

| 10 | EA | Even when the relationship feels close, I limit how much I share my personal thoughts. | Restriction of self-disclosure | Díaz-Mosquera, Guzman, & Gómez (2022) | ||

| 11 | EA | When my emotions fluctuate, I try to remain emotionally detached. | Emotional suppression and control | Fahs & Munger (2015) | ||

| 12 | EA | I dislike appearing vulnerable or dependent in this relationship. | Avoidance of emotional dependency | Núñez Segovia, Rios, & Serrano (2019) | ||

| 13 | EA | I doubt whether my partner’s emotional involvement is genuine or lasting. | Lack of emotional trust | Petrocchi, Cheli, & Cadorin (2020) | ||

| 14 | EA | When my partner becomes too emotionally close, I feel uncomfortable and want to distance myself. | Perceived threat from intimacy | Fraley, Waller, & Brennan (2000) | ||

| 15 | EA | Our conversations mainly focus on logistics rather than emotional exchange. | Instrumentalized communication | Collins & Horn (2018) | ||

| 16 | EA | As the relationship becomes closer, I instinctively pull back. | Regulation of emotional distance | Díaz-Mosquera et al. (2022) | ||

| 17 | EA | When we are temporarily apart, I feel relieved rather than distressed. | Relief following emotional disengagement | Fahs & Munger (2015) | ||

| 18 | RUA | I often worry that this relationship may end suddenly. | Anxiety about relationship termination | Müller, Hawkley, & Cacioppo (2024) | ||

| 19 | RUA | I frequently monitor my partner’s online activity to ensure the relationship is stable. | Hypervigilance and monitoring | Lafaita & Philippot (2023) | ||

| 20 | RUA | The uncertainty in this relationship makes me feel anxious and stressed. | Anxiety induced by uncertainty | Intrieri & Margentina (2017) | ||

| 21 | RUA | I need frequent reassurance that this relationship is stable. | Reassurance-seeking for security | Fraley et al. (2000) | ||

| 22 | RUA | I feel jealous when my partner behaves ambiguously toward others. | Jealousy in ambiguous relationships | Diotaiuti, Valente, & Bellizzi (2022) | ||

| 23 | RUA | I worry that I am more emotionally invested than my partner. | Jealousy in ambiguous relationships | Fahs & Munger (2015) | ||

| 24 | RUA | I repeatedly think about the meaning and status of our relationship. | Rumination about relationship ambiguity | Kindelberger et al. (2020) | ||

| 25 | RUA | I avoid clarifying the relationship because I fear an answer I may not want to hear. | Avoidance of relationship confirmation | Lafaita & Philippot (2023) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).