1. Introduction

The study of gravitational-wave (GW) polarizations provides a powerful way to distinguish General Relativity (GR) from alternative theories of gravity. In the classic classification by Eardley, Lee, and Lightman using the Newman–Penrose (NP) formalism [

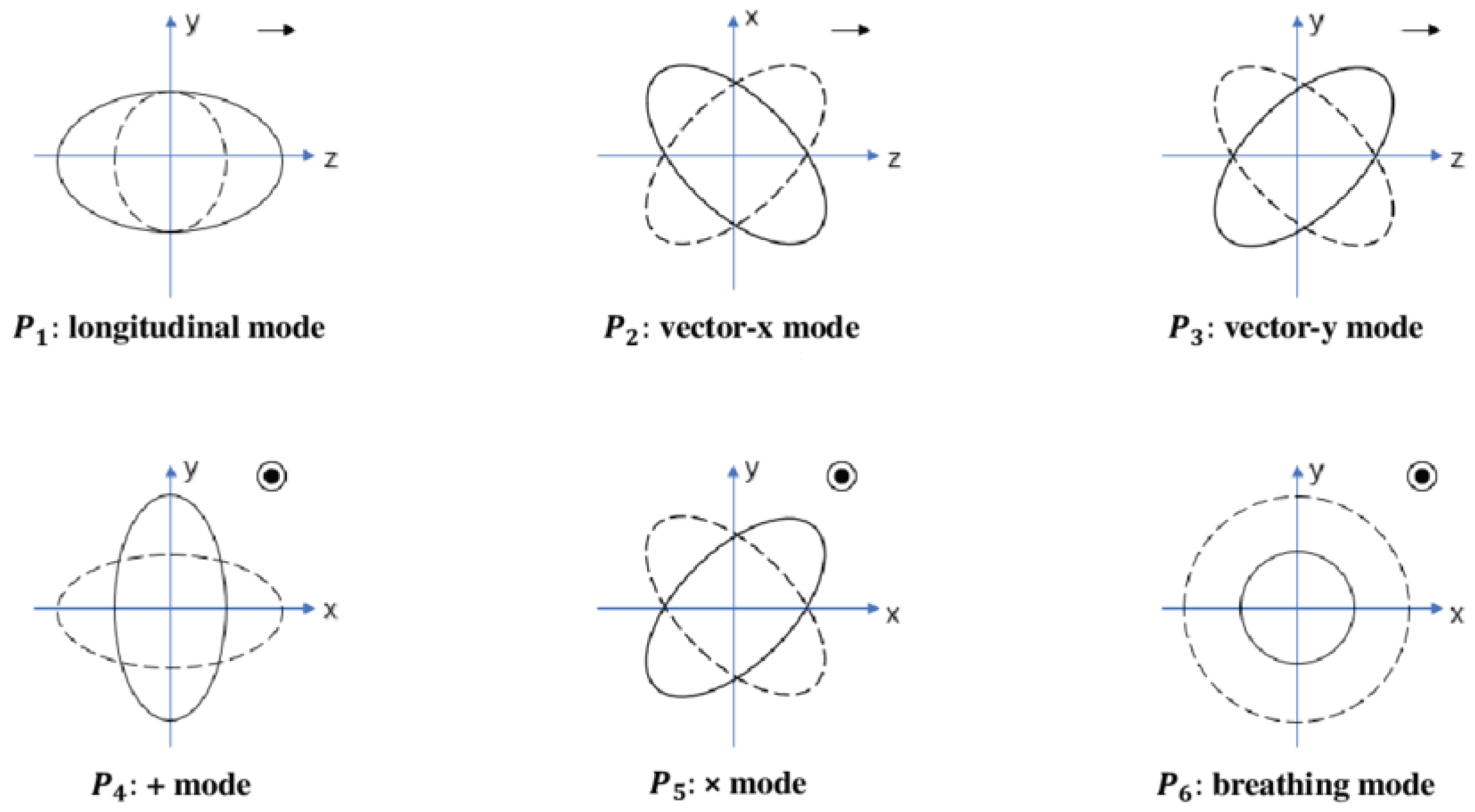

1], a general metric theory of gravity may contain up to six possible GW polarization states. In GR only two of these, the familiar tensor “plus” (⊕) and “cross” (⊗) modes, are present, corresponding to the two radiative degrees of freedom (DoF) of the metric. Extensions of GR often introduce additional scalar and/or vectorial modes whose presence modifies the relative displacement of freely-falling test particles.

A particularly well-known example is Brans–Dicke theory [

2], in which the scalar field gives rise to an additional transverse breathing mode. More generally, recent analyses using both the NP formalism and the irreducible (3+1) decomposition [

3,

4] have confirmed that the number of NP polarization states does not necessarily coincide with the number of radiative DoF in a theory. This mismatch appears naturally in scalar–tensor theories and in metric

gravity, where the Ricci scalar perturbation introduces a new massive scalar propagating mode that obeys a Klein–Gordon equation with an effective mass

[

5,

6,

7]. For massless propagation, this scalar mode produces a single independent polarization: a transverse breathing distortion of a ring of test particles. When the scalar mode is massive (

), however, the scalar sector induces a mixture of transverse breathing and longitudinal motion along the propagation direction; these two NP amplitudes are not independent but jointly encode a single scalar radiative DoF. Thus, metric

gravity contains three radiative DoF but may exhibit up to four NP polarization amplitudes in the massive case.

It is important to note recent discussions regarding the interpretation of NP quantities in theories containing massive modes. For gravitational waves whose group velocity differs from the speed of light, some NP components that vanish in GR no longer vanish identically, raising subtleties concerning the mapping between NP scalars and physical polarizations [

1]. This occurs because nonluminal propagation renders the wave vector non-null, so the standard NP null tetrad cannot be aligned with the direction of propagation, and the usual decoupling between radiative and non-radiative components breaks down [

3,

8]. These issues do not invalidate the NP approach but motivate complementary gauge-invariant formalisms.

Several modified gravity models exhibit similar features. In modified Gauss–Bonnet gravity

, for example, tensor waves propagate as in GR while an additional massive scalar mode appears [

9]. In massive gravity theories studied via Bardeen variables [

10], a normally non-radiative scalar mode becomes dynamical, constituting the helicity-0 component of a massive graviton. By contrast, quadratic theories such as Einstein–Dilaton–Gauss–Bonnet and dynamical Chern–Simons gravity can display the same polarization content as GR in their linearized limit [

11]. Extensions involving explicit matter–geometry couplings, including

and

gravity [

12], further illustrate the subtlety of polarization counting. Although

and

gravity share the same far-field polarization structure in vacuum (

), their source-dependent dynamics differ. The

theory, involving an additional scalar

, leads to distinguishable polarization patterns even in vacuum. These analyses also emphasize that the scalar mode

belonging to

gravity must be clearly distinguished from any additional matter scalar

.

Gravitational radiation in linearized metric

gravity has been studied in both power-series models

and in specific subclasses such as the Starobinsky model. Solar-system tests show that metric

gravity reproduces light deflection with the same post-Newtonian parameter

as GR, although perihelion precession can differ [

13]. Studies of waveform phases in extreme-mass-ratio inspirals suggest that deviations from GR may be detectable in some regimes. Polarization analyses performed in both

and Horndeski theories [

8] highlight the challenge of detecting longitudinal scalar modes with laser interferometers, whereas Pulsar Timing Arrays may offer greater sensitivity. The mixed longitudinal–breathing nature of the massive scalar propagating mode has been explicitly confirmed using the geodesic deviation equation [

14]. Additional applications of

gravity include the study of gravitational radiation from white dwarfs with sub- and super-Chandrasekhar masses, where all relevant polarization amplitudes were estimated using Green-function methods [

15].

A de Sitter background is particularly well motivated for analyzing the propagation of tensor and scalar modes in metric

gravity. It provides an excellent approximation to late-time cosmic acceleration driven by dark energy and also captures the quasi-exponential “slow-roll” inflationary phase in the early Universe. (Here “slow-roll” refers to the regime in which the inflaton’s kinetic energy remains small compared to its potential energy, yielding an almost constant Hubble parameter.) Background curvature affects dispersion relations, mode mixing, and asymptotic behavior of gravitational waves, which motivates studying the massive scalar mode and tensor modes directly on de Sitter space [

16,

17]. Because GR with a cosmological constant supports only two tensor polarizations, de Sitter space provides a clean setting for isolating any additional modes arising from

gravity and for making cosmological links between inflationary physics and late-time acceleration.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In

Section 2 we derive the field equations of metric

gravity on a de Sitter background and obtain the Klein–Gordon equation for the extra scalar mode with mass

.

Section 3 develops the perturbation of the Ricci tensor, and the resulting linearized field equations.

Section 4 performs the (3+1) irreducible decomposition into scalar, vector, and tensor sectors. In

Section 5 we specialize to the model

and present its explicit linearized dynamics.

Section 6 identifies the gauge-invariant Bardeen variables and derives the physical polarization content. Finally, in

Section 7 we verify these results using the geodesic deviation equation, demonstrating that the obtained polarization modes are physically realized in the relative acceleration of freely falling test particles.

2. Field Equations of Metric

Gravity on a de Sitter Background

In metric

gravity, the Einstein–Hilbert Lagrangian density

R is replaced by a general function

,

where

is the matter action,

collectively denotes the matter fields, and

in terms of the reduced Planck mass

(we use units

). Varying (

2) with respect to the metric and following, e.g., [

18], one obtains the metric

field equations

where

,

, and

is the matter stress–energy tensor. In vacuum we set

and (

4) reduces to

Taking the trace of (

4) yields the scalar (trace) equation

where

. In vacuum,

The trace equation will be the starting point for identifying the massive scalar propagating mode (the “scalaron”) and its effective mass.

2.1. Gravity, Scalar–Tensor form, and the Chameleon Mechanism

The field equations (

4) contain higher derivatives of the metric through

and

. A useful way to expose the extra scalar degree of freedom and to analyze screening—namely, the suppression of scalar-mediated fifth forces in high-density environments via an environment-dependent effective mass—is to recast metric

gravity as a scalar–tensor theory via a conformal transformation (see, e.g., [

6,

7]).

Define

where

is a scalar field. In metric

gravity the coupling parameter is fixed to

, reflecting the universal strength of the scalar coupling to matter. We then introduce the conformal transformation

which maps the

Jordan frame metric

to the

Einstein frame metric

. In the Jordan frame, matter is minimally coupled to

and freely falling test particles follow geodesics of

. In the Einstein frame, the gravitational sector takes the Einstein–Hilbert form plus a canonical scalar field, while matter acquires a

-dependent non-minimal coupling with respect to the Einstein-frame metric

.

In terms of

and

, the action (

2) becomes

where

and

are the covariant derivative and Ricci scalar of

, and

is the conformal factor relating the Einstein and Jordan metrics in the matter sector. The scalar potential is

The corresponding Einstein-frame field equations can be written as

where

is the scalar-field stress tensor and

is the Einstein-frame matter tensor. For a spatially homogeneous scalar field

in a spatially flat FRW background, this equation reduces to the standard cosmological Klein–Gordon equation

which in the vacuum limit (

) becomes

the equation solved in inflationary and background cosmological applications [

6,

19,

20]. This explicitly links the early-time inflationary dynamics of the model to its late-time cosmological implications.

The Jordan frame is the one in which matter is minimally coupled and experimental observables (such as test-particle trajectories and detector responses) are most directly interpreted. The Einstein frame is mathematically convenient for analyzing the dynamics of the extra scalar degree of freedom and for discussing stability, screening mechanisms, and cosmological evolution. Physical predictions are frame-independent provided one consistently transforms both the metric and matter variables. In this paper, we perform the gravitational-wave analysis in the Jordan frame (where the Bardeen variables and metric perturbations are defined), while the Einstein-frame description is used only to clarify the scalar–tensor structure and the chameleon mechanism.

The additional scalar degree of freedom in metric

gravity mediates a universal fifth force [

6,

7] through its coupling to the trace of the matter stress–energy tensor. The scalar field

in (

11) couples universally to matter via

and can mediate this fifth force unless its effective mass becomes large in high-density environments. The

chameleon mechanism exploits the density dependence of the effective potential

where

is the local matter density. In regions of high density,

develops a minimum at which the effective mass

is large, so that the scalar-mediated force is short-ranged and consistent with local tests of gravity. In low-density environments (cosmological scales) the minimum shifts and

can become small enough for the scalar to drive cosmic acceleration or leave imprints on structure formation [

21,

22,

23].

For an

model to exhibit viable chameleon behavior, the scalar potential

derived from (

13) must satisfy certain conditions in at least part of field space,

which translate into nontrivial constraints on the form of

and its derivatives [

22]. This ensures that the scalar field can be heavy in high-density regions while remaining light enough on cosmological scales to influence late-time acceleration.

2.2. Slow-Roll Inflation and Scalaron Dynamics in the Einstein Frame

The scalar–tensor reformulation of metric

gravity introduced above provides a natural framework for discussing early-Universe inflation driven by the scalaron. When written in the Einstein frame, the scalar field

obeys the field equation obtained by varying the Einstein-frame action (

11),

where

is given in Equation (

13). For a spatially homogeneous scalar field

evolving in a spatially flat FLRW background,

, this equation reduces to the standard cosmological Klein–Gordon equation [

6,

19,

20]

where

. The background expansion is governed by the Friedmann equation

Inflation occurs when the potential dominates the kinetic energy and the field slowly rolls along

. This is quantified by the slow-roll parameters

where inflation requires

and

. Under these conditions, Equation (

22) reduces to the familiar slow-roll equation

and the Hubble parameter satisfies

.

For the Starobinsky-type models considered in this work, the potential

possesses a nearly flat region at large curvature (

), ensuring that the slow-roll conditions (

24) are naturally satisfied. In this regime the scalaron behaves as an inflaton with an effective mass

, and the inflationary predictions coincide with those of the well-known

model [

5,

24]. Observationally, the slow-roll phase gives rise to a nearly scale-invariant spectrum of primordial curvature perturbations and a suppressed tensor-to-scalar ratio, in excellent agreement with current CMB constraints.

Although slow-roll inflation operates at curvature scales far above those relevant for present-day gravitational-wave detectors, the same underlying extra scalar degree of freedom of

gravity governs both regimes. In the inflationary context this degree of freedom is commonly referred to as the

scalaron, while at the level of linear perturbations it appears as a propagating massive scalar mode. In particular, the mass of the scalar perturbation at the de Sitter solution,

controls the propagation of the scalar polarization of gravitational waves and provides a link between the early-time inflationary dynamics of the model and its late-time cosmological implications.

We are particularly interested in constant-curvature de Sitter solutions and small perturbations around them. For a vacuum constant-curvature background with

and

, the trace equation (

8) reduces to the algebraic condition

Any function

that admits a solution of (

27) possesses a de Sitter solution with curvature

. (Anti–de Sitter solutions correspond to constant-curvature solutions with

and must be analyzed separately.) For the modified Starobinsky model

the de Sitter curvature

is determined by

which reduces to

in the late-time, low-curvature regime

.

1 Thus, constant-curvature solutions in

gravity provide a unified framework for modeling both early-time inflation and late-time dark-energy–dominated epochs, and they form the natural background for our gravitational-wave polarization analysis.

In the remainder of this paper, we will work in the Jordan frame and treat the extra propagating scalar mode directly in terms of the curvature perturbation . To avoid confusion of notation, we will use:

for the Einstein-frame scalar field entering the scalar–tensor and inflationary description in this subsection; and

(or, equivalently, a canonically normalized scalar perturbation with mass ) for the extra propagating scalar mode that appears in the linearized Jordan-frame field equations and in the Bardeen-variable analysis.

2.3. Metric Perturbations Around a de Sitter Background

We now consider small perturbations around a background solution

which solves the vacuum field equations (

6). In particular, we will later specialize to a de Sitter background satisfying (

27). The perturbed metric is written as

where indices on

are raised and lowered with the background metric

.

To linear order, the curvature quantities and the function

expand as

where

R is the background Ricci scalar and

is its perturbation.

It is convenient to separate background and perturbed covariant derivatives. Denoting by

the covariant derivative associated with

and by

the one associated with

, the difference between them acting on a generic tensor

is (see, e.g., [

25])

where the connection difference

is

All quantities without tildes refer to the background metric. These relations allow one to express perturbed curvature tensors and the perturbed trace equation in terms of

and

.

Varying the vacuum trace equation (

8) and keeping terms linear in the perturbations yields

where we have used (

31) and (

32). Equation (

34) is valid for a general background.

For the de Sitter backgrounds of interest in this work, the Ricci scalar is constant,

so that

and

,

are constants. In this case the second line of (

34) vanishes,

, and we obtain the simplified scalar perturbation equation

or, equivalently,

with

Here

is the effective mass of the scalar propagating mode associated with the curvature perturbation

in the de Sitter background. Equation (

37) is a Klein–Gordon equation for

and describes the propagation of a massive scalar mode in addition to the usual tensor modes of general relativity. In later sections we will relate

to a gauge-invariant Bardeen combination and denote the corresponding massive scalar propagating mode by

.

The mass scale

determines the range of the scalar-mediated interaction and the characteristic dispersion of the scalar polarization of gravitational waves in a de Sitter background. On sub-horizon scales with

, the scalar mode behaves effectively massless and can, in principle, contribute to additional polarization signatures. On scales

the mode is strongly suppressed, consistent with local gravity constraints. For the modified Starobinsky model (

28), one finds

in the high-curvature regime, linking the mass scale to both early-time inflationary dynamics and late-time modifications of gravitational-wave propagation in cosmology.

The detailed decomposition of the metric perturbations into scalar, vector, and tensor Bardeen variables, and the identification of the corresponding polarization modes, will be carried out in the following sections.

3. Perturbations of the Ricci Tensor and Scalar Dynamics in Gravity

The evolution of cosmological perturbations in

gravity influences both the expansion history of the Universe and the propagation of gravitational waves across different cosmological epochs [

26]. To understand how the gravitational field responds to small deviations from a background metric—whether a cosmological FRW background, a black hole spacetime, or, as in this work, a de Sitter background—it is necessary to compute the perturbation of curvature quantities. Since the Ricci tensor enters directly in the field equations, its perturbation represents the leading-order correction to the spacetime curvature and is essential for identifying the massive scalar propagating mode present in

theories.

Furthermore, gauge transformations in gravity are complicated by the presence of higher derivatives of R. A fully gauge-invariant description of perturbations therefore requires determining how the scalar curvature perturbation interacts with metric perturbations through . This provides a crucial intermediate step on the way to constructing the gauge-invariant Bardeen potentials in later sections.

To obtain the perturbed field equation, we expand the metric as

and linearize each term of the

field equation (

6). Using

and

, and recalling that

is constant, the variation of covariant derivative terms such as

must be treated carefully. In general,

However, on a constant-curvature de Sitter background one has

so the connection-variation term vanishes identically. As a result, at linear order

After accounting for this simplification, the variation of

yields the operator

.

Perturbing the vacuum field equation (

6) using a de Sitter background (

) yields the linearized equation

where

is the background de Sitter metric.

To obtain (

42), we decompose the metric as

with indices on

raised and lowered using

. Since de Sitter space is a constant-curvature solution of metric

gravity, the background satisfies

which follows directly from the constancy of

. This condition reflects the fact that

is a nonzero constant fixed by the chosen

model and represents the effective gravitational coupling on the background.

The nonperturbed trace equation (

8) evaluated on a constant-curvature vacuum background yields the algebraic de Sitter condition

which determines the allowed background curvature

of the

theory. Substituting (

45) into the background field equation (

6) and using

and

gives

which implies

Using (

45) once more yields

showing that the background is an Einstein space and, in fact, maximally symmetric.

For a spatially flat FLRW spacetime, the Ricci scalar is . In de Sitter space , so and .

A de Sitter Universe undergoes exponential expansion,

and this constant-curvature solution will serve as the background for our perturbative analysis.

Dividing (

42) by

and substituting

and

gives

At this stage, it is important to clarify the fate of the algebraic term

appearing in Equation (

50). On a constant–curvature de Sitter background, the trace condition (

45) implies

so that this contribution may be written as

. This term is proportional to the background curvature scale and contains no derivatives. For gravitational waves of wavelength

, corresponding to the local inertial (short–wavelength) limit relevant for detector-scale propagation, such curvature-suppressed algebraic terms do not contribute to the dynamical wave equation. They may therefore be consistently neglected, or equivalently absorbed into the background de Sitter curvature. With this understanding, the linearized field equation reduces to Equation (

54).

To evaluate (

50), we recall the general linearized Ricci tensor [

25,

27]

where

.

For gravitational-wave propagation at detector scales, the wavelength of the perturbation is much shorter than the de Sitter curvature radius

. One may therefore work in the local inertial frame of the background, in which

while still retaining the nonzero constants

and

. In this limit, curvature-suppressed algebraic terms proportional to

do not contribute to the dynamical propagation of high-frequency gravitational waves.

Under this approximation, (

50) reduces to

The linearized scalar curvature is

and the linearized Einstein tensor reduces to

Substituting (

55) and (

56) into (

54) yields the perturbed field equation

where the effective scalar mass

arises from the trace of the linearized field equations and is given by

In the Minkowski limit

, this reduces to

Once the effective scalar mass is identified, its physical meaning becomes transparent by considering a Fourier (plane-wave) decomposition of the gauge-invariant variables. In a constant-curvature background, linear perturbations admit the ansatz , which diagonalizes the spatial Laplacian. Substituting this into the Klein–Gordon–type equation yields the dispersion relation . Thus the extra scalar mode propagates as a massive mode, in contrast to the transverse tensor polarizations, which remain massless. This plane-wave form clarifies how the additional scalar polarization arises in metric gravity.

These expressions show that the scalar curvature perturbation propagates as a massive scalar field on the de Sitter background. The mass controls the range and dispersion of the scalar gravitational-wave mode and depends explicitly on the background curvature . Since changes across cosmological epochs, the behavior of the scalar mode encodes information about the underlying cosmic expansion and offers potential observational signatures beyond the standard tensor modes.

6. SVT Decomposition of the Perturbed Ricci Tensor in Metric Gravity

In this section we revisit the

decomposition in the presence of matter sources. Instead of starting from the vacuum perturbed field equation (

57), we now consider the linearized field equations of the modified Starobinsky model in a nearly Minkowski background, including the stress–energy tensor

:

where

is the

coupling,

is the scalar curvature perturbation, and

is the background Minkowski metric. Using the relation

the term proportional to

can also be written as

, in agreement with the vacuum analysis.

The Klein–Gordon equation for the massive extra scalar mode (

106) in vacuum generalizes in the presence of matter to

or equivalently

where

is the trace of the stress–energy tensor. Equation (

112) shows that

behaves as a massive scalar field (the massive scalar propagating mode) sourced by the trace

T; in the limit

we recover the vacuum equation.

Using the definition of the Einstein tensor in the flat background,

and eliminating

via (

113), the linearized field equation (

110) may be written as

or, equivalently,

Equations (

115) and (

116) are the starting point for the

decomposition with matter: the left-hand side contains the usual Ricci-tensor perturbation corrected by the massive scalar propagating mode

, while the right-hand side involves the traceless combination

.

6.1. Irreducible SVT Decomposition of the Metric and Matter

Following [

4,

10], the SVT decomposition of the metric perturbation

in a nearly Minkowski background reads

where we have defined the new quantities

with the assumption that

as

. The transverse and traceless conditions are

Both in [

4] and in our earlier Bardeen-variable work, it has been shown how the variables

transform under a gauge transformation generated by

with

as

. Such transformations are parametrized as

with

. Following the same procedure as in [

4], one obtains the gauge-invariant scalar and vector combinations

The tensor perturbation

is already gauge invariant.

We can perform a similar SVT decomposition of the matter stress–energy tensor

on the right-hand side of the field equations. We write

where

,

S,

,

P,

,

, and

are new scalar, vector, and tensor quantities with the constraints

along with boundary conditions

as

(spatial infinity). The overall minus sign in the isotropic part

in (130) will be tracked explicitly in the relations obtained from stress–energy conservation below.

The conservation law

determines relations between

,

S,

,

P,

,

, and

. In the nearly Minkowski background used throughout this section we have

, so (

135) reads

As a useful special case (and for later physical interpretation), we note that a perfect fluid at rest in Minkowski space has

so that

and

. Comparing with (129)–(130), this corresponds to vanishing momentum and anisotropic-stress components (

,

,

,

,

), while retaining the scalars

and

P. In particular, the trace is

The

component of (

135) gives

where we have used (129) and the constraint (

131). For

, it is convenient to separate the two pieces entering

. First, taking a spatial derivative of (130) yields

and the constraints (132)–(133) imply

. Second, taking a time derivative of (129) gives

Stress–energy conservation for

then combines (

140) and (

141) as

where we used

.

Taking one more spatial derivative of (

142) and applying the constraints on

and

, we obtain

Applying the boundary condition at spatial infinity for

S,

P, and

(which also guarantees the uniqueness of the decomposition), we conclude that

Inserting this condition into (

142) gives

Equation (

144) can also be rewritten as

Equations (

139), (

145), and (

146) are the required set of differential equations that relate the newly defined irreducible matter variables

,

,

S,

P,

,

, and

. These results match Eq. (23) of [

34], up to differences in notation.

6.2. (3+1) Decomposition of the Perturbed Ricci Tensor

In gravity the field equations contain higher-order derivatives of the metric through their dependence on the Ricci scalar R. Unlike in General Relativity, where the Einstein tensor alone determines the dynamics, theories introduce a massive scalar propagating mode, associated with the scalar curvature perturbation . To fully understand how this scalar mode interacts with the usual scalar, vector, and tensor components of the metric perturbation, it is necessary to go beyond the standard metric decomposition and analyze the perturbation of the Ricci tensor itself.

By expressing in terms of the gauge-invariant Bardeen variables and the scalar curvature perturbation, we obtain a set of decoupled differential equations that reveal how each mode behaves in the presence of matter. This decomposition provides a more complete and transparent description of the linearized dynamics in gravity and is particularly useful for identifying modifications to gravitational-wave propagation and structure formation due to the extra scalar mode.

Following the approach in [

4], the components of the Einstein tensor

were decomposed in GR to obtain a set of differential equations for the perturbation of the Einstein tensor in terms of the Bardeen variables. In the case of

gravity, we instead decompose the perturbed Ricci tensor

in terms of the Bardeen variables, to obtain a new set of differential equations. The components of

are

In terms of these Bardeen variables

, the field equation in the form of Equation (

116) can be recast into a set of differential equations, each corresponding to a component of

. For example, the 00 component of (

116) takes the form

Substituting the expression for

from Equation (

147), using

and

, we obtain

which gives the corresponding differential equation for the 00 component of

.

Next we consider the differential equations corresponding to the

component of the perturbation of the Ricci tensor. Equation (

116) gives

Substituting the expression (148) for

in Equation (

152), Equation (129) for

, and using

, we obtain

At spatial infinity (

), we impose

, so that

, and similarly

and

. Under these conditions Equation (

153) reduces to

Separating the longitudinal and transverse parts of (

153) and comparing the coefficients of

yields

Equations (

154) and (

155) are the differential equations based on the

component of

in terms of the Bardeen variables and the massive scalar propagating mode.

Finally, we consider the

component of the perturbation of the Ricci tensor, which is

Substituting the expression (149) for

and Equation (130) for

into Equation (

156), and equating coefficients of the independent SVT pieces, we obtain

These equations imply

and, using

,

Equations (

160)–(

163) are the set of differential equations corresponding to the

component of

in terms of the Bardeen variables and the matter SVT variables. These results are consistent with those derived in [

34], up to differences in notation.

6.3. Cosmological Interpretation of the SVT Equations with the Extra Scalar Degree of Freedom

The system of equations (

151), (

154), (

155), and (

160)–(

163) allows a direct physical interpretation in cosmology once the background is promoted from Minkowski to a slowly varying FLRW or de Sitter spacetime.

The

equation (

151) is a modified Poisson-type equation: the gravitational potential

is sourced not only by the energy density

, but also by pressure

P, time derivatives of the potential

, and the dynamics of the scalar curvature perturbation

[

35,

36]. In GR, the corresponding equation at linear order would involve essentially the Laplacian of

sourced only by

, with no extra scalar degree of freedom contribution. This modification leads to a scale- and time-dependent effective gravitational coupling, which directly affects the growth of cosmological structure and can be constrained by large-scale structure and weak-lensing surveys.

The

sector separates into a transverse (vector) part and a longitudinal (scalar) part. The transverse part, Equation (

154) together with Equation (

160), shows that vector perturbations

are sourced by the transverse momentum density

and anisotropic stress

, just as in GR. Thus

gravity does not introduce new propagating vector modes at linear order. The longitudinal scalar equation (

155), however, contains the time derivative of the additional scalar degree of freedom

, modifying the time evolution of

relative to GR. The time dependence of the gravitational potentials is directly probed by the integrated Sachs–Wolfe (ISW) effect and cross-correlations of CMB maps with large-scale structure.

The equations show that the tensor sector, Equation (161), obeys a wave equation structurally identical to that of GR, but with a source from anisotropic stress. In gravity, the background scalar degree of freedom and the modified expansion history can nevertheless change the amplitude damping and effective propagation of gravitational waves over cosmological distances, providing an additional channel to test modifications of gravity with standard sirens.

Finally, the scalar sector of the perturbed field equations provides a direct window into one of the characteristic phenomenological signatures of modified gravity. In linear cosmological perturbation theory, scalar metric perturbations are described by the gauge-invariant Bardeen potentials

and

, which coincide in General Relativity in the absence of matter anisotropic stress. Their inequality,

, is commonly referred to as

gravitational slip and signals a departure from GR caused either by imperfect fluids or by additional gravitational degrees of freedom [

36,

37].

In metric

gravity, the scalar part of the

equations, Equations (162) and (

163), reveals that gravitational slip arises generically even when the matter anisotropic stress vanishes (

, equivalently

). In this case, the difference between the two scalar potentials is instead sourced by the scalar curvature perturbation

, reflecting the presence of the propagating scalar mode. This modification of the relation between

and

is a robust signature of

models and can be observationally constrained through joint analyses of galaxy clustering, redshift-space distortions, and weak gravitational lensing [

36,

38]. The full SVT decomposition of

thus provides a unified framework for linking the gauge-invariant scalar dynamics of the theory to observable effects in both gravitational-wave physics and cosmology.

7. Geodesic Deviation Method to Find the Polarization Content

The geodesic deviation equation relates the Riemann curvature tensor to the relative acceleration of neighboring geodesics and therefore provides a direct probe of gravitational-wave polarizations in a given theory of gravity [

27,

39]. In this section we use the geodesic deviation equations to identify the polarization modes of gravitational waves in our specific metric

model,

for which the scalar curvature perturbation

obeys the massive Klein–Gordon equation

on a de Sitter background. The scalar perturbation

corresponds to the extra scalar degree of freedom, in addition to the usual tensor modes of GR.

We first work in the local Minkowski patch of the de Sitter background, which is appropriate for interferometric detectors whose size is much smaller than the background curvature radius. We then show how the same polarization structure appears when the calculation is formulated fully on a de Sitter FRW background.

7.1. Local Minkowski Patch of de Sitter

The general geodesic deviation equation is

where

is the separation vector between neighboring geodesics and

is proper time. For gravitational-wave detectors we work in the weak-field, slow-motion limit: the detector is at rest in the chosen coordinates and far from the source, so

and we can identify proper time with coordinate time,

In this regime the covariant derivatives in (

166) reduce to ordinary time derivatives, and the spatial components of the geodesic deviation equation become

where overdots denote derivatives with respect to

t.

In linearized gravity, the Riemann tensor is

where

is the metric perturbation on the local Minkowski background

. We decompose

into a transverse-traceless tensor part

and a scalar part associated with the scalar curvature perturbation

.

For the scalar mode, in a convenient gauge compatible with the Newtonian (longitudinal) gauge used in

Section 4, the scalar perturbation can be chosen proportional to the background metric:

where

C is an overall constant that only rescales the amplitude and does not affect the polarization pattern. For simplicity we set

below.

Substituting into the expression for the Riemann tensor and focusing on

, we find

Now consider a scalar wave propagating along the

direction,

In the transverse directions

x and

y,

so that

In the longitudinal direction,

Using the massive Klein–Gordon equation for the extra scalar mode in the local Minkowski patch,

which implies

we obtain

For a monochromatic plane wave

the tidal components become

The geodesic deviation equations

then give

These equations show that the extra scalar degree of freedom induces both a transverse breathing mode (in the X and Y directions) and a longitudinal mode (in the Z direction). This is precisely the expected polarization content for a massive scalar mode.

In pure GR, where only the transverse-traceless tensor is present, and the scalar-induced contributions vanish; only the familiar ⊕ and ⊗ tensor modes remain. In metric gravity, the nonzero generates additional breathing and longitudinal polarizations on top of the GR tensor modes.

7.2. Geodesic Deviation on a de Sitter FRW Background

We now sketch how the same polarization structure arises when the calculation is performed directly on the de Sitter background without passing explicitly to a Minkowski patch. In spatially flat FRW coordinates, the de Sitter metric can be written as

with constant Hubble parameter

in four dimensions.

We consider small perturbations around this background in Newtonian gauge. Restricting initially to the scalar sector, the perturbed metric takes the form

where equality of the Bardeen potentials

holds for metric

gravity on a de Sitter background (

Section 4), with

Thus the additional scalar degree of freedom is directly encoded in both the temporal and isotropic spatial perturbations of the metric.

To relate the geodesic deviation equation to the detector frame, it is convenient to introduce an orthonormal tetrad adapted to a comoving observer,

so that physical (proper) spatial separations are measured with hatted indices. In this orthonormal frame the geodesic deviation equation takes the form

The tidal tensor splits naturally into a background de Sitter contribution and a perturbation induced by scalar and tensor modes,

For the spatially flat de Sitter background, the nonvanishing Christoffel symbols are

and

which follow directly from the FRW line element. From these, the coordinate-basis Riemann component relevant for geodesic deviation is

For exact de Sitter expansion

, one has

, yielding

Projecting onto the orthonormal tetrad,

the factors of

from the tetrads cancel those implicit in the metric, leaving

We now include perturbations. Restoring both scalar and tensor modes, the perturbed FRW metric may be written as

where

denotes the transverse–traceless tensor perturbation. Introducing the Minkowski metric

, all perturbations can be collected into a single tensor

so that the metric assumes the conformal form

Expanding the Riemann tensor to first order,

the linearized part depends only on derivatives of

. Because the conformal factor multiplies both background and perturbation, one finds

Raising indices and projecting onto the orthonormal tetrad yields

where

is precisely the tidal matrix obtained in

Subsection 7.1.

Therefore, for the massive scalar propagating mode, we can directly carry over the Minkowski result, with careful attention to the overall sign,

for a monochromatic mode, and similarly for a generic wave packet using the Klein–Gordon equation (

180). The overall factor

dilutes the tidal amplitude due to cosmic expansion, while leaving the polarization pattern unchanged.

The geodesic deviation equations for physical separations

are therefore

The background term produces the isotropic de Sitter expansion, while the wave-induced part reproduces the same transverse breathing and longitudinal pattern as in the local Minkowski analysis. Thus, cosmological expansion modifies amplitudes but does not change the polarization content.

7.3. Polarization Classification via

The geodesic deviation equations derived above show explicitly that the additional scalar degree of freedom in our

model produces both breathing and longitudinal motion of test particles. For completeness, we now review a more formal method to classify the polarization modes using the components of

, following [

1,

40].

In a local inertial (Minkowski) patch of the spacetime, the perturbed metric may be written in terms of scalar, vector, and tensor perturbations as

where

and

are the scalar Bardeen potentials (with

in the present context),

encodes the vector (shear) perturbations, and

is the transverse–traceless tensor mode. To linear order in the perturbations, the Riemann tensor components entering the geodesic deviation equation are

The six possible GW polarization modes can be encoded by writing the tidal tensor

as a symmetric

matrix,

where

are the six independent polarization amplitudes (scalar longitudinal, two vector modes, two tensor modes, and scalar breathing). They correspond to the six standard polarization patterns shown in

Figure 1.

2

For a plane wave propagating along the

z direction, comparison of (

212) with the matrix form (

213) yields

Here

and

encode the vector (shear) polarizations,

represents the usual ⊕ and ⊗ tensor modes, and

are the scalar Bardeen potentials.

In metric

gravity we have generic vector perturbations

in vacuum, so the vector modes are absent and

. The tensor modes

and

coincide with those of GR and correspond to the ⊕ and ⊗ polarizations. The remaining scalar modes are encoded in

(longitudinal mode, involving both

and

) and

(breathing mode, involving only

). Because

in our model and are related to the additional scalar degree of freedom via

both

and

are nonzero, confirming that the model exhibits a mixed longitudinal and breathing scalar polarization in addition to the two tensor polarizations.

In summary, the geodesic deviation analysis—both in the local Minkowski patch and on the full de Sitter background—shows that the metric model supports:

two massless tensor modes , identical to those of GR;

one massive scalar mode (the massive scalar propagating mode), which decomposes into a transverse breathing polarization and a longitudinal polarization along the propagation direction.

This pattern agrees with the general expectation for metric gravity and provides the polarization content against which current and future GW observations can test this class of models.

8. Conclusion and Future Outlook

In this work we developed a unified and fully gauge-invariant analysis of gravitational-wave polarizations in metric gravity, with particular emphasis on the modified Starobinsky model Working on a constant-curvature de Sitter background, we reformulated the linearized field equations in terms of Bardeen gauge-invariant variables and the scalar curvature perturbation , thereby making the massive scalar propagating mode manifest. By deriving the Klein–Gordon equation for directly from the perturbed trace equation, we verified that the scalar mode behaves as a massive propagating field with mass on the de Sitter background. This establishes the scalar curvature perturbation as the source of the additional breathing and longitudinal polarizations absent in General Relativity.

We complemented the Bardeen-variable analysis with a full decomposition of the perturbed Ricci tensor, including the presence of matter sources. This approach revealed explicitly how scalar, vector, and tensor perturbations enter the modified field equations and how the scalar sector departs from its GR behavior. In particular, the decomposition demonstrated that (i) the vector sector remains nondynamical and identical to that of GR, (ii) the tensor sector continues to satisfy the standard transverse–traceless wave equation, and (iii) all modifications are encoded in the scalar sector through the dynamical curvature perturbation . The resulting coupled equations for , , and illustrate the origin of the gravitational slip, modified Poisson equation, and scale-dependent evolution of cosmological perturbations characteristic of models.

A complementary geodesic-deviation analysis was carried out in both the local-Minkowski patch of de Sitter spacetime and in the fully covariant de Sitter background. In both cases, the tidal tensor depends on the scalar curvature perturbation and yields the characteristic polarization pattern: two tensor modes (⊕ and ⊗), a breathing mode, and a longitudinal mode. This agrees with the general classification of metric theories admitting up to six polarizations and verifies, by two independent methods, that metric gravity predicts exactly three observable polarization sectors: two tensor and one massive scalar.

From a cosmological perspective, the mass of the massive scalar propagating mode sets the transition scale between GR-like behavior at high wavenumbers and modified gravity effects on large scales. Because the same massive scalar propagating mode controls the late-time background evolution, the growth rate of structure, and the propagation of gravitational waves, future multi-probe observations—combining large-scale structure, weak lensing, CMB anisotropies, pulsar-timing arrays, and gravitational-wave observatories—provide a coherent program for testing the viability of gravity on both astrophysical and cosmological scales.

Future Outlook

Several natural extensions follow from the framework developed here:

Beyond de Sitter backgrounds: The methods employed here can be generalized to slowly evolving FLRW backgrounds, permitting a direct link between gravitational-wave propagation and the time dependence of the mass of the massive scalar propagating mode in realistic cosmologies.

Mode mixing and GW propagation: A next step is the study of mode mixing between the tensor and scalar sectors, including amplitude damping and potential dispersion effects in late-time, low-density environments.

Constraints from forthcoming surveys: Current and future missions (Euclid, LSST, SKA, LISA, pulsar-timing arrays) will significantly improve constraints on gravitational slip, the mass of the scalar mode, and the scale-dependent growth of cosmological perturbations. The gauge-invariant formalism presented here is well suited for connecting theoretical predictions with these upcoming datasets.

Extension to broader modified-gravity families: The techniques developed in this paper—decomposition of the perturbed Ricci tensor, isolation of the massive scalar propagating mode, fully covariant GW polarization extraction, and geodesic-deviation analysis—can be applied to more general higher-curvature theories such as gravity, scalar–tensor Horndeski theories, and Einstein–dilaton–Gauss–Bonnet models.

Overall, the combination of gauge-invariant SVT analysis, Ricci-tensor decomposition, and geodesic deviation provides a robust framework for identifying and interpreting the polarization content of gravitational waves in metric gravity. This establishes a consistent pathway for future observational tests capable of distinguishing GR from its simplest and most theoretically motivated extensions.