1. Introduction

The global competition for artificial intelligence (AI) leadership has emerged as a defining geopolitical dynamic of the 21st century, with the United States and China representing two fundamentally distinct approaches to technological advancement, governance, and societal integration [

1,

2]. While the United States has traditionally leveraged its strengths in foundational research, entrepreneurial innovation, and private-sector dynamism, China has pursued a state-led strategy characterized by comprehensive planning, rapid deployment, and strategic integration across sectors [

3].

The emergence of

agentic AI—autonomous systems capable of independent reasoning, planning, and execution with minimal human intervention—represents a critical inflection point in this competition [

4,

5]. These systems promise transformative impacts across healthcare, education, defense, and industry but also introduce complex governance challenges related to safety, ethics, and human oversight [

6,

7].

This paper provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of U.S. and Chinese strategic frameworks for AI literacy and adoption, with particular focus on agentic AI leadership. Our examination encompasses: (1) national policies and governance structures; (2) educational initiatives and workforce development; (3) regulatory frameworks and compliance mechanisms; (4) technological roadmaps and implementation strategies; and (5) international positioning and cooperation frameworks. The analysis synthesizes insights from 27 recent publications spanning academic research, policy documents, government reports, and industry analyses.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 examines AI literacy initiatives;

Section 3 analyzes AI adoption in education;

Section 4 compares governance and regulatory frameworks;

Section 5 discusses strategic positioning and international relations;

Section 7 proposes a hybrid strategic framework; and

Section 10 concludes with recommendations.

2. AI Literacy: National Strategies and Implementation

2.1. U.S. Approach to AI Literacy

The United States employs a decentralized, multi-stakeholder approach to AI literacy, characterized by diverse initiatives across federal agencies, academic institutions, private corporations, and non-profit organizations [

8]. Recent executive orders and legislative proposals emphasize the critical importance of AI literacy across the educational continuum, from K-12 through higher education and workforce training [

9]. Key federal initiatives include the

National AI Initiative Act and various Department of Education programs focused on STEM education and digital literacy [

10].

Despite these efforts, significant challenges persist. Research indicates that only 20-25% of U.S. educators feel adequately prepared for AI integration, even as 60-70% recognize its importance for future competitiveness [

8]. The decentralized nature of the U.S. educational system creates disparities in access to AI resources, with affluent districts often having significantly greater capacity for technology integration than underserved communities [

11].

2.2. Chinese Approach to AI Literacy

China’s approach to AI literacy is fundamentally different, characterized by centralized planning and implementation through national strategies such as the

New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan [

12]. The Chinese government has mandated AI education across all levels of the educational system, with standardized curricula, teacher training programs, and assessment mechanisms [

13]. This top-down approach enables rapid scaling and consistent implementation across diverse regions and institutions [

14].

Recent empirical studies reveal both successes and challenges in China’s AI literacy initiatives. Faculty members in Chinese universities demonstrate significant usage of generative AI tools for both personal and professional purposes, with particular application in formative assessment practices [

15]. However, integration into summative assessments and core pedagogical practices remains limited, reflecting ongoing challenges in curriculum adaptation and assessment transformation [

16].

2.3. Comparative Analysis of Corporate AI Literacy

Beyond formal education, corporate AI literacy represents another critical dimension of national competitiveness. Chinese corporations operating internationally, particularly in regions like Africa, are increasingly emphasizing AI literacy among managers and employees as a source of sustainable competitive advantage [

17]. Research indicates that AI awareness and empowerment significantly enhance competitive positioning, both directly and through their influence on innovation consciousness [

17].

Table 1 provides a comprehensive comparison of U.S. and Chinese approaches to AI literacy across multiple dimensions.

3. AI Adoption in Education and Workforce Development

3.1. U.S. Educational Integration

The United States has pursued diverse approaches to AI integration across educational levels. In K-12 education, initiatives focus on computational thinking, programming skills, and ethical considerations [

8]. However, implementation remains uneven, with only approximately 30-40% of schools reporting structured AI programs despite 80-90% recognizing their importance [

8].

Higher education institutions in the U.S. have been more proactive, with leading universities establishing dedicated AI institutes, degree programs, and research centers. The integration extends beyond computer science departments to include applications in humanities, social sciences, and professional schools [

9]. Military education represents a particularly significant domain, with the Department of Defense investing heavily in AI training programs to prepare personnel for human-AI teaming and autonomous system oversight [

18].

3.2. Chinese Educational Integration

China has implemented one of the world’s most comprehensive frameworks for AI integration in education, spanning formal schooling, higher education, vocational training, and professional development [

12]. Universities are rapidly adopting AI for administrative functions, student services, and pedagogical innovation [

14]. Academic leaders identify both opportunities and challenges, with particular emphasis on personalized learning, resource optimization, and research enhancement [

14].

Shadow education—the extensive private tutoring sector in China—represents another significant domain of AI adoption. English as a Foreign Language (EFL) practitioners in shadow education demonstrate diverse levels of AI literacy and varying approaches to tool integration, reflecting both the opportunities and complexities of AI adoption in informal learning contexts [

13]. Their experiences highlight the importance of context-specific frameworks that address unique pedagogical challenges and ethical considerations [

13].

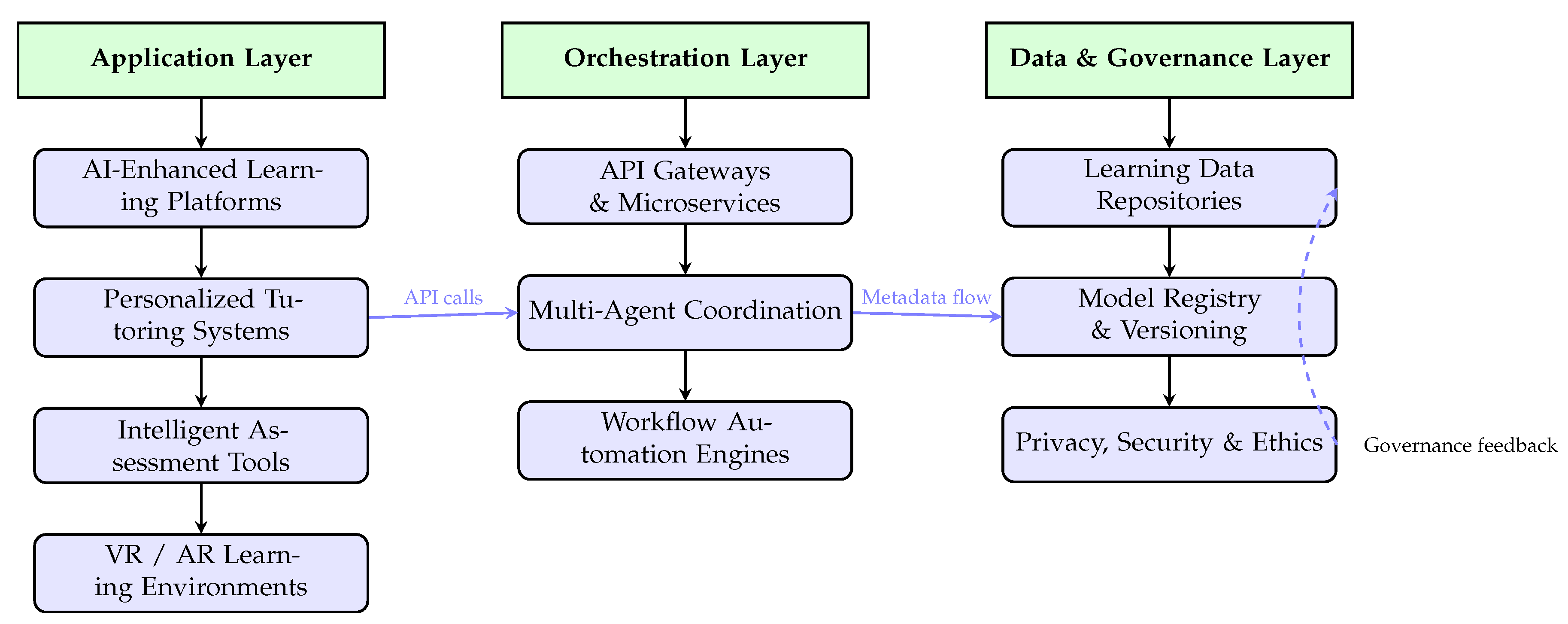

3.3. Architectural Framework for AI-Enhanced Education

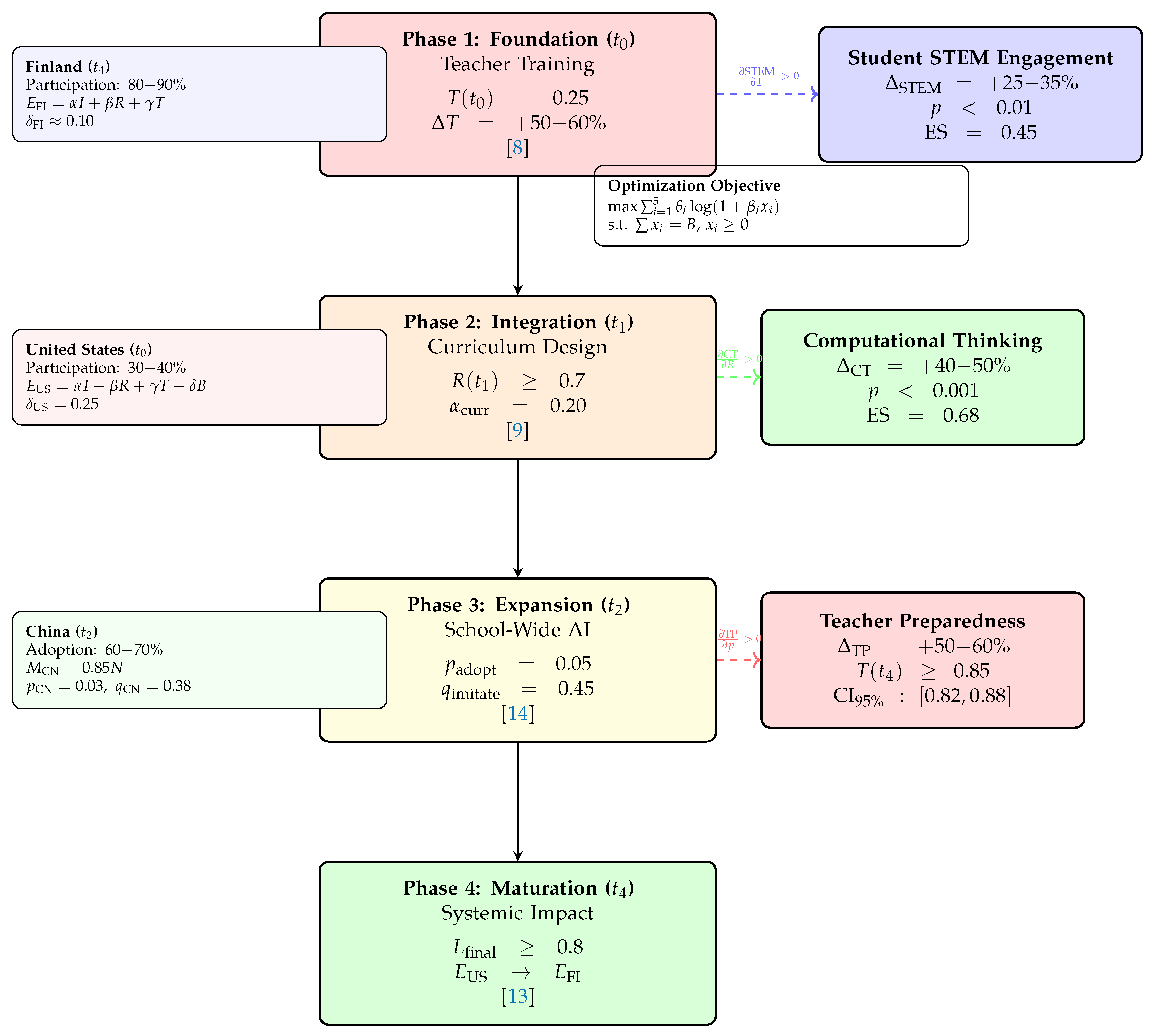

Figure 1 presents a comprehensive architectural framework for AI-enhanced education that synthesizes elements from both U.S. and Chinese approaches. This multi-layered architecture addresses technical, pedagogical, and governance dimensions while maintaining flexibility for contextual adaptation.

4. Governance and Regulatory Frameworks

4.1. U.S. Regulatory Landscape

The United States employs a sectoral approach to AI regulation, with various federal agencies exercising jurisdiction based on application domains [

19]. Key regulatory bodies include the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical AI, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for consumer protection, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) for technical standards development [

6]. Recent initiatives emphasize risk management frameworks, transparency requirements, and public-private collaboration [

10].

Significant challenges persist in the U.S. regulatory landscape, including regulatory fragmentation, slow legislative processes, and difficulties in balancing innovation promotion with risk mitigation [

6]. The emergence of agentic AI systems has exposed particular gaps in existing frameworks, especially regarding autonomous decision-making, liability attribution, and human oversight requirements [

6].

4.2. Chinese Regulatory Landscape

China has implemented one of the world’s most comprehensive and stringent regulatory frameworks for AI governance. The centerpiece of this framework is the mandatory AI content labeling regime implemented in September 2025, which requires both visible markers and embedded metadata for all AI-generated content [

20]. This represents the world’s most comprehensive AI transparency framework to date [

20].

Beyond content regulation, China’s approach encompasses data security, algorithmic transparency, ethical guidelines, and industry-specific standards [

21]. Governance is centralized under the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), with coordination across multiple ministries and regulatory bodies [

3]. The framework reflects China’s emphasis on social stability, national security, and technological sovereignty [

7].

4.3. Healthcare-Specific Regulations

Healthcare represents a particularly significant domain for AI regulation in both countries. The U.S. has developed specialized frameworks for AI-enabled medical devices, with particular attention to safety, efficacy, and post-market surveillance [

22]. These frameworks must balance innovation acceleration with patient protection, especially for generative AI applications in mental health and other sensitive domains [

22].

China has similarly prioritized healthcare AI regulation, with frameworks addressing clinical validation, data privacy, and integration with existing healthcare systems [

5]. Comparative analysis reveals both convergence and divergence in approaches, with implications for international patients, medical research collaboration, and global health initiatives [

23].

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Governance Models

Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of U.S. and Chinese AI governance models across multiple dimensions.

5. Strategic Positioning and International Relations

5.1. U.S. Strategic Priorities

The United States has articulated a strategic framework focused on maintaining technological leadership, promoting democratic values, and ensuring national security in the AI domain [

19]. Key priorities include: (1) advancing fundamental research through agencies like NSF and DARPA; (2) developing interoperable standards that reflect U.S. technological advantages; (3) building international coalitions around shared democratic values; and (4) implementing export controls to protect critical technologies [

10].

Recent analyses highlight particular emphasis on agentic AI competitiveness, with proposals for strategic frameworks addressing interoperability, governance, and international collaboration [

4]. The U.S. approach reflects a belief in the importance of values-based competition and the strategic advantage of open, democratic systems [

11].

5.2. Chinese Strategic Priorities

China’s AI strategy is fundamentally integrated with broader national objectives, including technological self-reliance, economic transformation, and global influence expansion [

24]. The

New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan articulates a comprehensive vision for AI leadership by 2030, with specific milestones and resource allocations [

12]. Recent initiatives emphasize

common prosperity objectives, with AI positioned as a tool for reducing inequality and promoting sustainable development [

3].

Internationally, China has proposed a

Global AI Governance Action Plan framework comprising 13 points addressing AI safety, infrastructure, and data standards [

24]. This represents an effort to shape international norms and standards in alignment with Chinese interests and governance preferences [

25]. Analysis of Chinese international media reveals strategic narratives emphasizing pride in technological achievements, hope for future development, and careful management of international perceptions [

25].

5.3. Metaverse and Extended Reality Strategies

Beyond traditional AI domains, both countries are actively developing strategies for emerging technologies like the metaverse and extended reality (XR). China has articulated a comprehensive policy agenda for XR development, with particular emphasis on industrial applications, content regulation, and international competitiveness [

26]. These initiatives reflect broader patterns in Chinese technology strategy, combining ambitious vision statements with detailed implementation frameworks [

26].

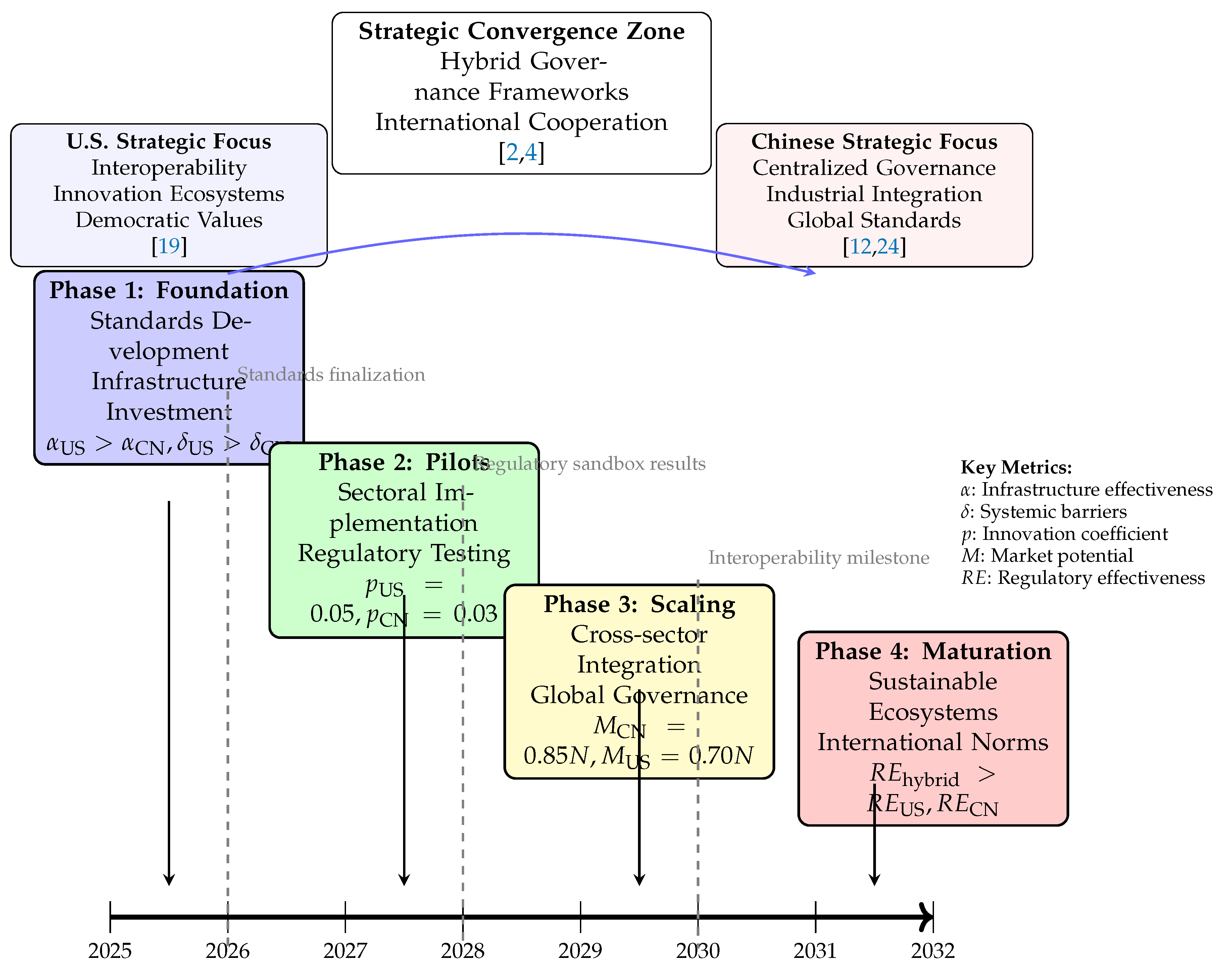

5.4. Roadmap for Agentic AI Leadership

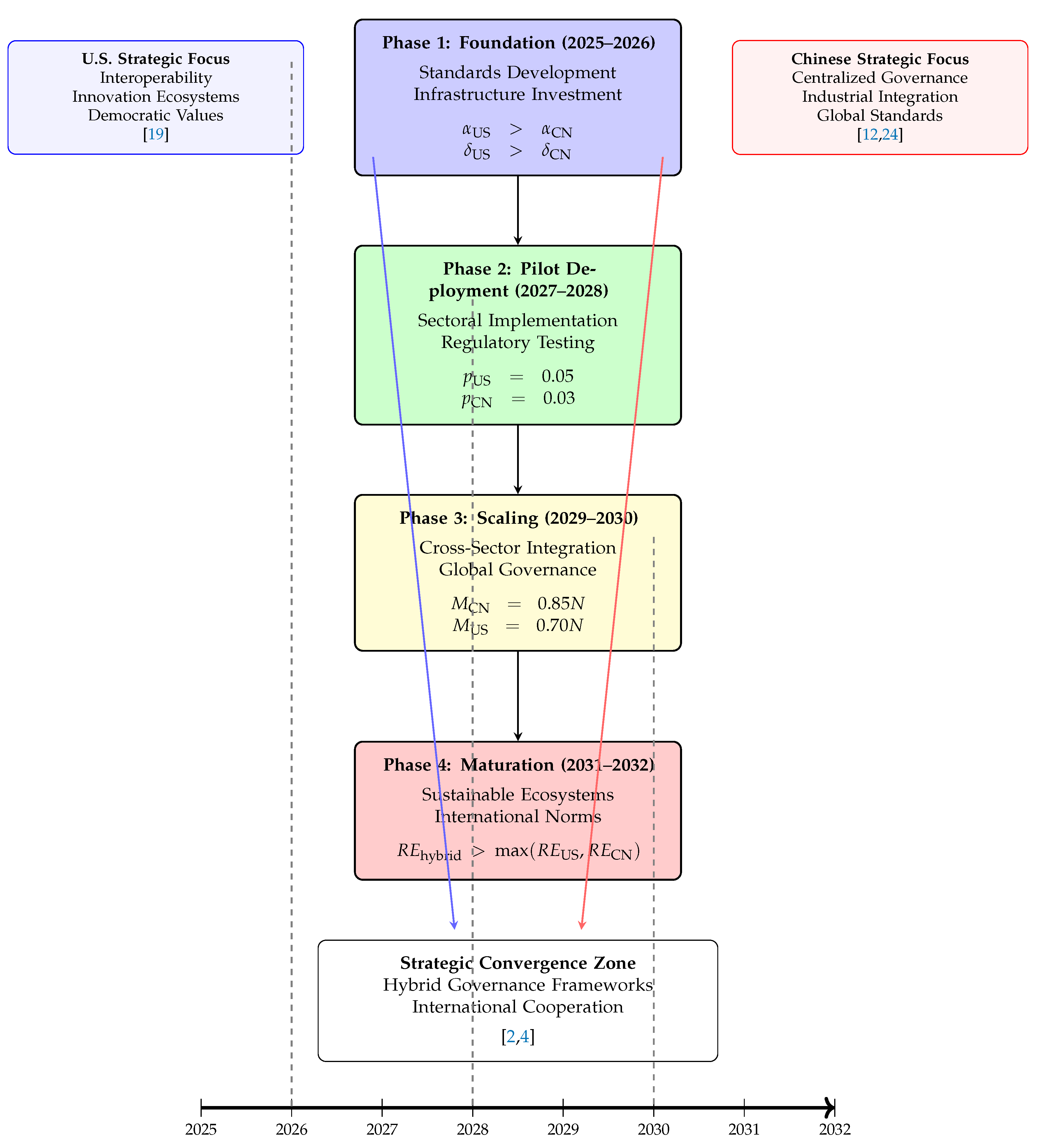

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive strategic roadmap for agentic AI leadership that synthesizes elements from both U.S. and Chinese approaches. This roadmap addresses technical development, governance evolution, international cooperation, and societal integration across a five-year horizon.

6. Key Proposals and Findings from Literature

This section presents five key analytical frameworks and findings derived from the reviewed literature, illustrating the complexity and strategic dimensions of AI literacy and adoption in the U.S.-China context.

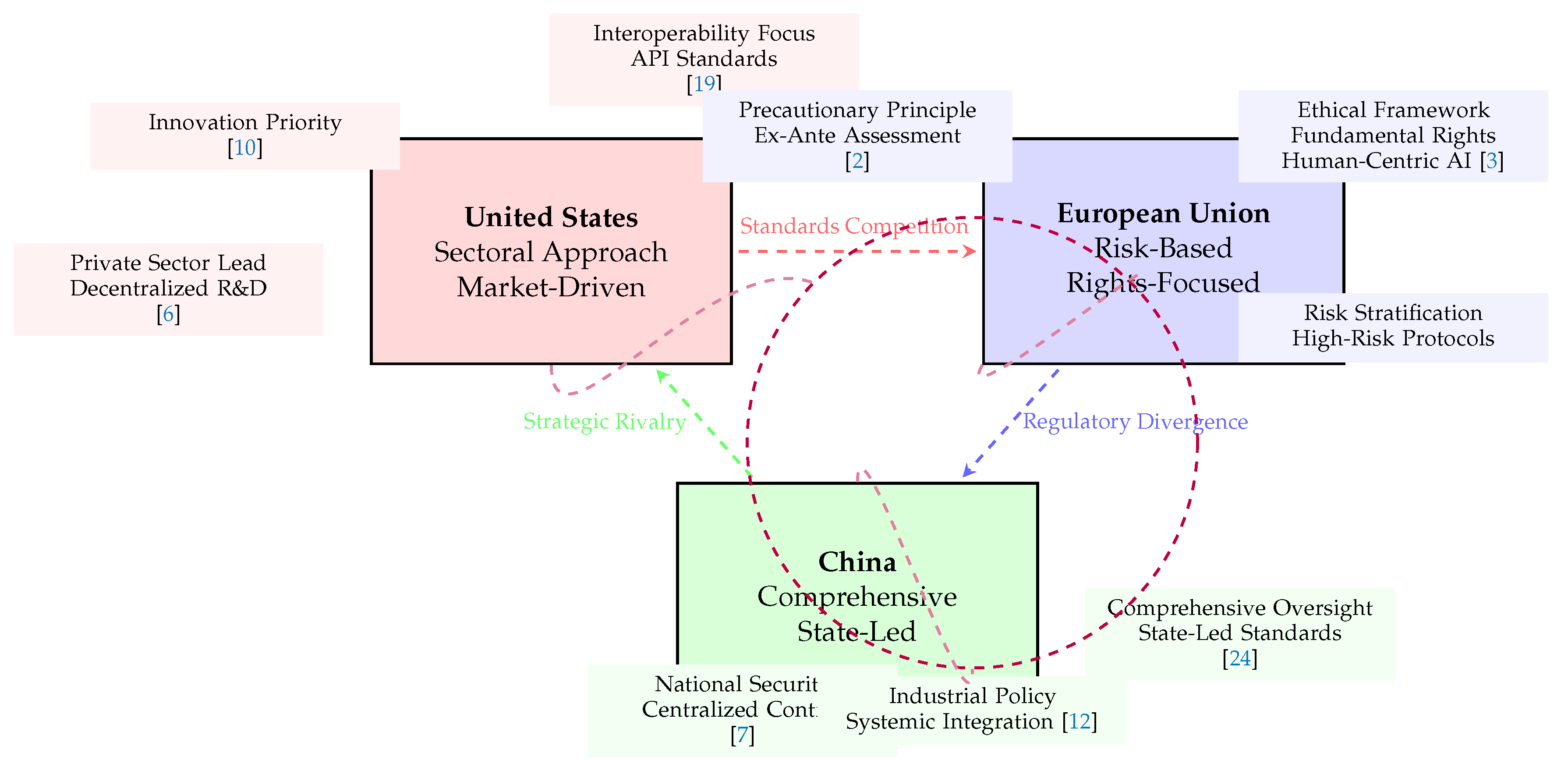

6.1. AI Governance Comparison Framework

Figure 3 illustrates a comparative framework for AI governance approaches across three major geopolitical actors: the United States, China, and the European Union. This framework synthesizes findings from multiple studies [

1,

2,

3].

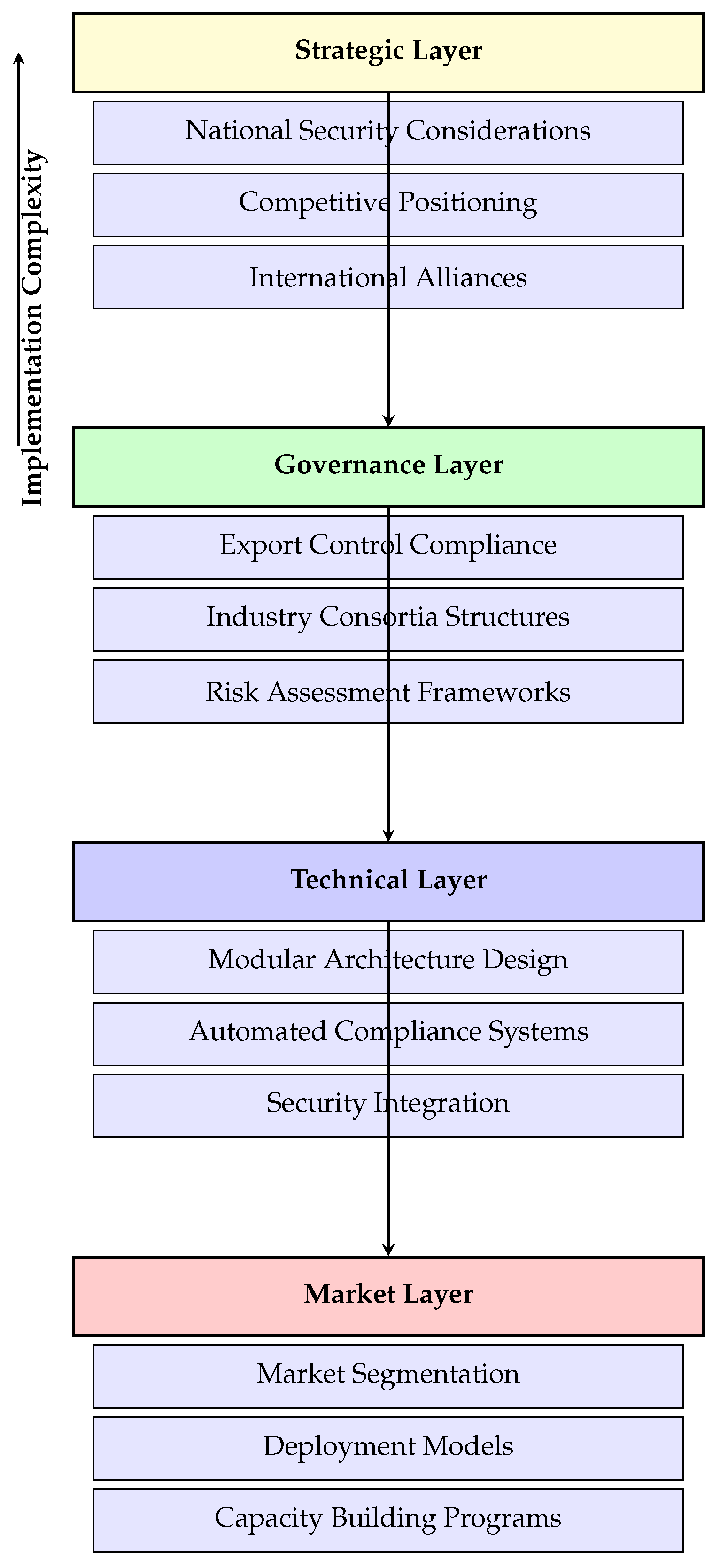

6.2. U.S. AI Export Leadership Framework

Figure 4 depicts the multi-layer architecture proposed for U.S. AI export leadership, addressing technical, governance, and market dimensions [

10].

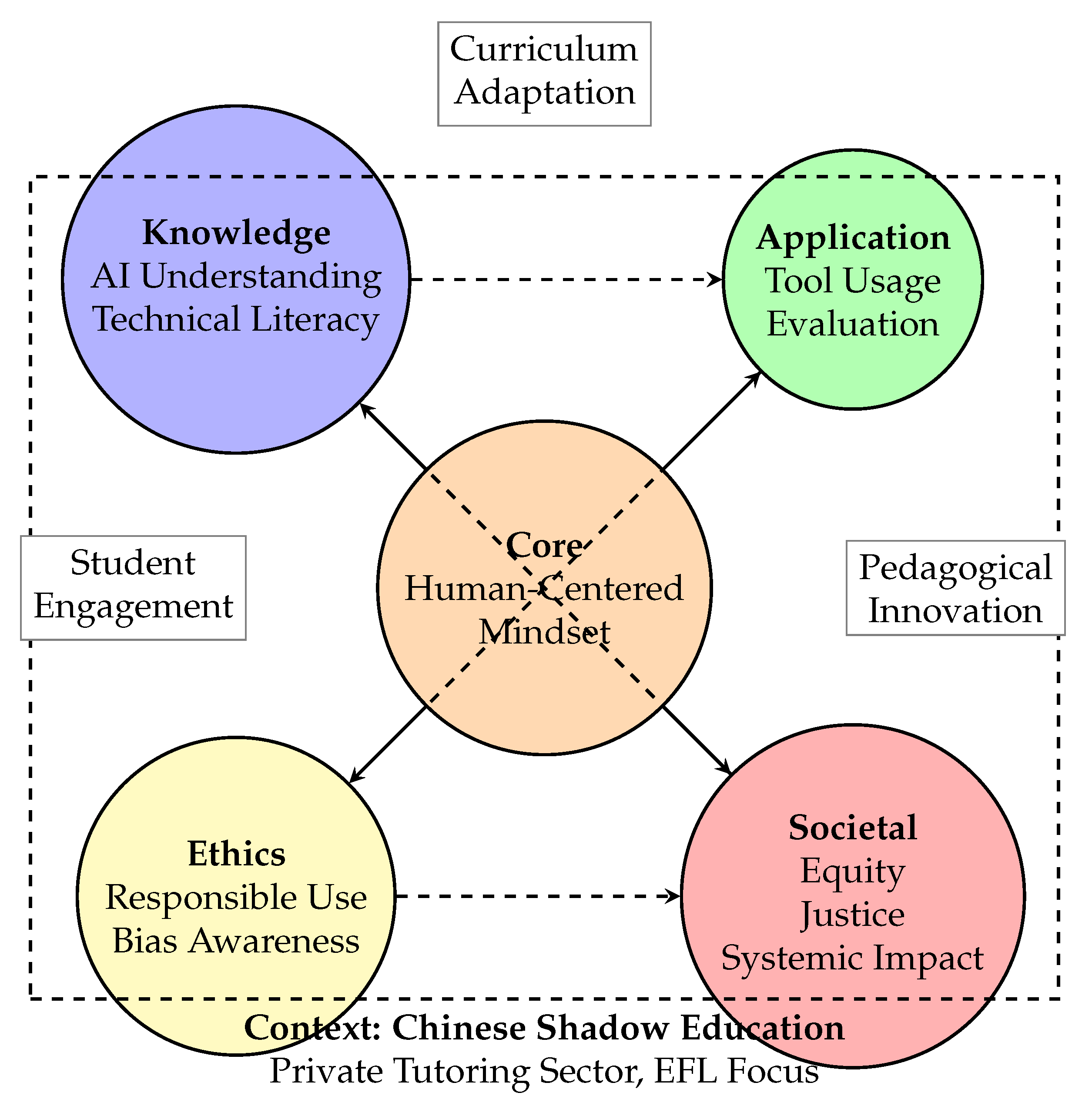

6.3. AI Literacy in Chinese Shadow Education

Figure 5 illustrates the five-dimensional AI literacy framework identified for Chinese EFL practitioners in shadow education, highlighting the complex interplay of technical, ethical, and pedagogical dimensions [

13].

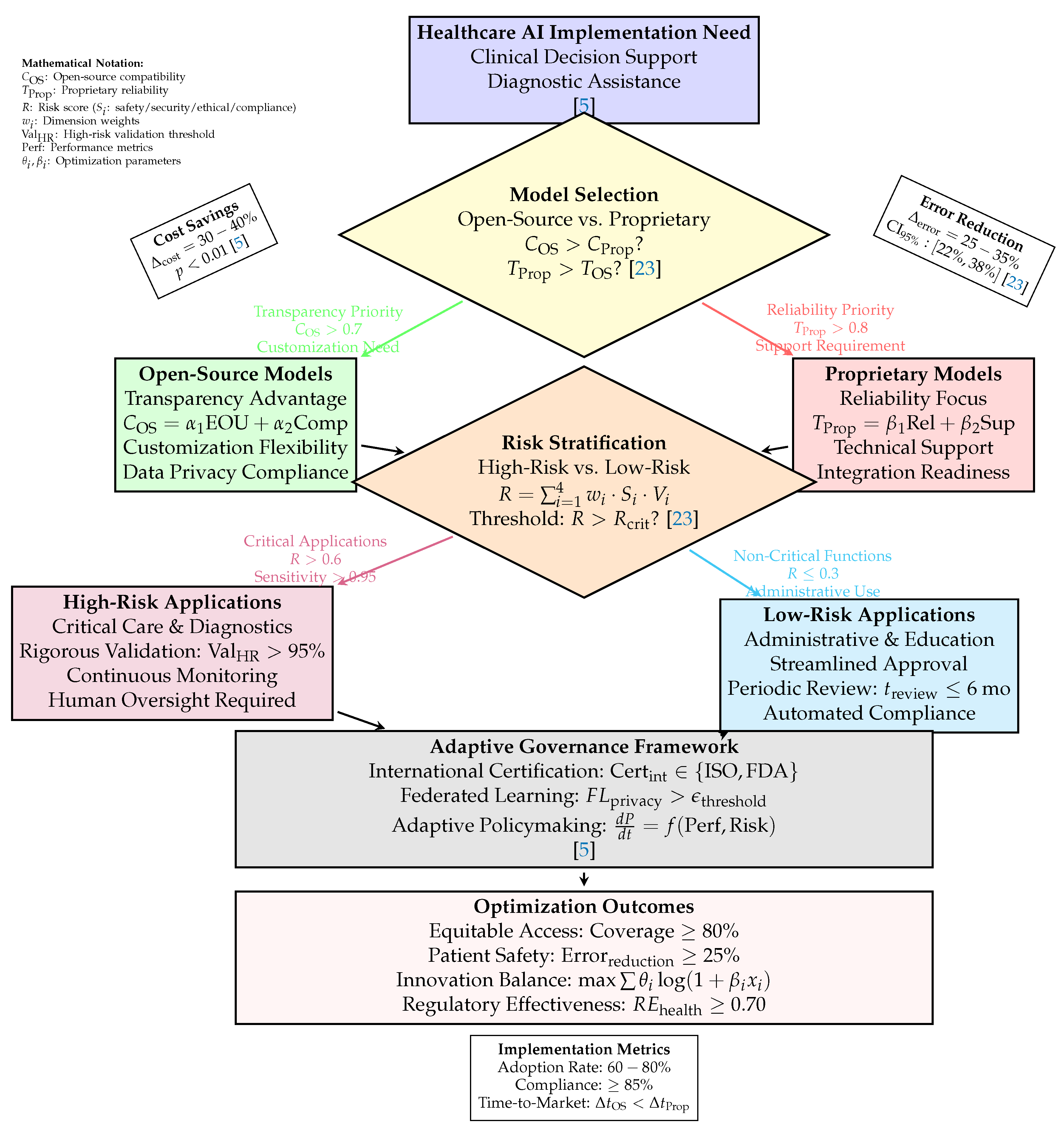

6.4. Agentic AI in Healthcare Governance

Figure 6 presents the risk management and governance framework for agentic AI in healthcare, addressing the dichotomy between open-source and proprietary models [

5,

23].

6.5. U.S. K-12 AI Competitiveness Framework

Figure 8 illustrates the structured framework for enhancing U.S. K-12 competitiveness in the agentic generative AI era, showing resource allocation and implementation phases [

8].

Figure 7.

Optimized multi-phase, vertically structured framework for U.S. K–12 AI literacy enhancement with quantified adoption dynamics, resource optimization, causal pathways, and international benchmarking.

Figure 7.

Optimized multi-phase, vertically structured framework for U.S. K–12 AI literacy enhancement with quantified adoption dynamics, resource optimization, causal pathways, and international benchmarking.

Figure 8.

Phased strategic roadmap for agentic AI leadership (2025–2032) with quantitative parameter evolution and geopolitical convergence pathways.

Figure 8.

Phased strategic roadmap for agentic AI leadership (2025–2032) with quantitative parameter evolution and geopolitical convergence pathways.

6.6. Analysis and Synthesis

The five frameworks presented in this section collectively illustrate several key patterns in the U.S.-China AI competition:

Governance Divergence: Fundamental differences in regulatory philosophy and implementation approaches create both challenges and opportunities for international cooperation.

Educational Innovation: Both countries are developing sophisticated frameworks for AI literacy, with China emphasizing systematic implementation and the U.S. focusing on innovation ecosystems.

Sector-Specific Approaches: Healthcare represents a particularly complex domain requiring specialized governance frameworks that balance innovation with safety.

Strategic Competition: Export controls and international standards have become key battlegrounds in the AI race.

Emerging Hybrid Models: There is growing recognition of the need for frameworks that synthesize strengths from different governance approaches.

These frameworks provide valuable insights for policymakers, educators, and industry leaders seeking to navigate the complex landscape of AI literacy and adoption in an increasingly competitive global environment.

7. Proposed Hybrid Strategic Framework

Based on our comprehensive comparative analysis of U.S. and Chinese approaches to AI literacy, adoption, governance, and strategic positioning, we propose a hybrid framework that synthesizes strengths from both models while addressing their respective limitations. This framework is particularly relevant for agentic AI leadership but applies broadly to AI development and deployment.

7.1. Core Principles

The hybrid framework is built on five core principles derived from our analysis:

Balanced Governance: Combine U.S. innovation-friendly regulation with Chinese comprehensive oversight through tiered, risk-based approaches [

2,

3].

Interoperable Standards: Develop technical standards that enable cross-border collaboration while respecting legitimate national security and cultural differences [

19,

24].

Inclusive Literacy: Create educational frameworks that combine U.S. emphasis on critical thinking and ethics with Chinese systematic implementation and scale [

8,

12].

Responsible Innovation: Establish oversight mechanisms that balance rapid technological advancement with robust safety, security, and ethical safeguards [

6,

21].

Global Cooperation: Foster international collaboration frameworks that address shared challenges while respecting diverse governance approaches [

10,

24].

7.2. Architectural Components

The framework comprises four interconnected architectural components:

Technical Architecture: Modular, interoperable systems supporting both open-source and proprietary models with embedded governance capabilities [

5,

23].

Governance Architecture: Multi-stakeholder oversight combining sectoral expertise with centralized coordination [

6,

20].

Educational Architecture: Lifelong learning pathways integrating formal education, workforce training, and continuous professional development [

9,

13].

International Architecture: Cooperation mechanisms addressing standards alignment, research collaboration, and crisis response [

10,

24].

7.3. Implementation Strategy

Implementation should proceed through phased pilots addressing specific application domains (healthcare, education, critical infrastructure) with iterative refinement based on empirical evidence and stakeholder feedback [

5,

23]. Success metrics should encompass technical performance, societal impact, economic benefits, and ethical compliance [

2,

17].

8. Quantitative Foundations and Mathematical Methods

This section presents the quantitative foundations and mathematical methods that underpin the comparative analysis of AI literacy and adoption frameworks. We develop formal models for AI literacy assessment, governance effectiveness, adoption dynamics, and strategic competition metrics.

8.1. Mathematical Models for AI Literacy Assessment

8.1.1. Multi-Dimensional Literacy Score

We define an AI literacy score

for individual

i as a weighted combination of

n competency dimensions:

where:

represents competency score in dimension j (e.g., technical knowledge, ethical understanding, practical application)

are dimension weights satisfying

represents individual variation

Based on [

13,

15], we identify five key dimensions (

):

8.1.2. Educational System Effectiveness

The effectiveness

E of an educational system in promoting AI literacy can be modeled as:

where:

with coefficients

,

representing system characteristics. Empirical data from [

8,

12] suggests:

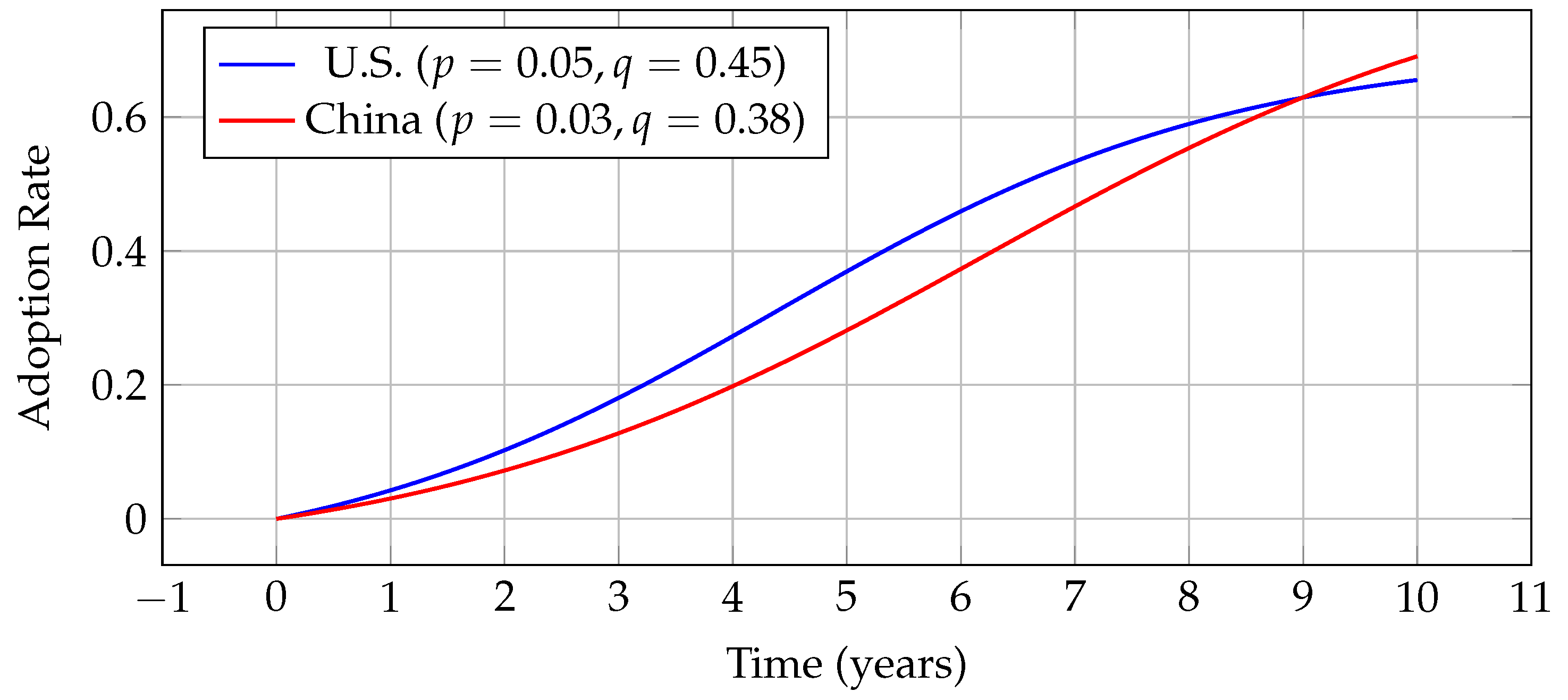

8.2. Diffusion Models for AI Adoption

8.2.1. Bass Diffusion Model Adaptation

We adapt the Bass diffusion model to analyze AI adoption in educational institutions:

where:

: Cumulative number of adopters by time t

M: Market potential (maximum possible adopters)

p: Coefficient of innovation (external influence)

q: Coefficient of imitation (internal influence)

From [

14], for Chinese universities:

where

N is the total number of institutions. For U.S. universities [

8]:

8.2.2. Technology Acceptance Model Extension

We extend the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) for AI tool adoption:

where:

8.3. Governance and Risk Assessment Models

8.3.1. Risk Scoring Function

For AI system risk assessment [

23]:

where:

and

are vulnerability factors,

are weights with

.

8.3.2. Regulatory Effectiveness Index

We define a regulatory effectiveness index

:

where:

8.4. Strategic Competition Metrics

8.4.1. Competitiveness Index

Building on [

17], we define AI competitiveness

:

where:

with

,

.

8.4.2. Strategic Gap Analysis

The strategic gap between two systems can be quantified as:

where

is the score of system A on dimension

j, and

is the standard deviation across systems.

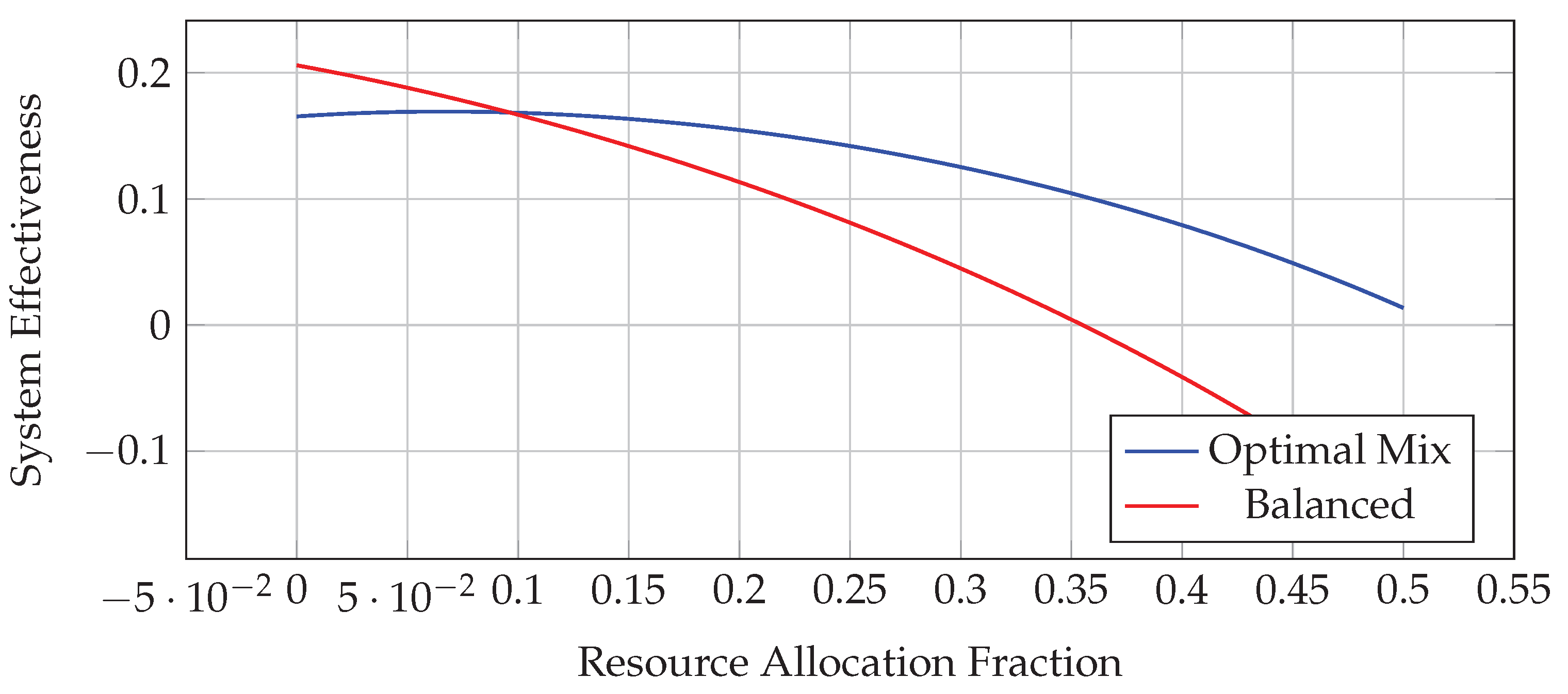

8.5. Optimization Models for Resource Allocation

8.5.1. Budget Allocation Optimization

Given total budget

B, we optimize allocation across

n categories:

where:

: Budget allocated to category i

: Effectiveness coefficient for category i

: Marginal returns parameter

From [

8], optimal allocation for U.S. K-12:

for [Infrastructure, Training, Curriculum, Assessment, Research] respectively.

8.5.2. Multi-Objective Optimization for AI Governance

We formulate a multi-objective optimization problem:

where:

8.6. Network Models for AI Ecosystems

8.6.1. Ecosystem Connectivity

Define an AI ecosystem as a network

with adjacency matrix

A:

Network density

measures ecosystem connectivity:

8.6.2. Knowledge Diffusion Model

Knowledge diffusion through the network follows:

where

is knowledge level of node

i at time

t, and

is external input.

8.7. Statistical Methods for Comparative Analysis

8.7.1. Difference-in-Differences Framework

To estimate policy impacts:

where

is outcome for unit

i at time

t,

indicates treatment group,

indicates post-policy period.

8.7.2. Structural Equation Modeling

Based on [

17]:

with measurement models:

8.8. Numerical Results and Sensitivity Analysis

8.8.1. Parameter Estimation Results

Using data from the literature, we estimate key parameters:

Table 3.

Estimated Parameters from Literature Review

Table 3.

Estimated Parameters from Literature Review

| Parameter |

U.S. Estimate |

China Estimate |

Source |

| Teacher Preparedness (T) |

0.25 |

0.40 |

[8] |

| Adoption Rate (p) |

0.05 |

0.03 |

[14] |

| Imitation Coefficient (q) |

0.45 |

0.38 |

[14] |

| Infrastructure Investment () |

0.35 |

0.45 |

[12] |

| Systemic Barriers () |

0.25 |

0.15 |

[3] |

| Governance Effectiveness (G) |

0.65 |

0.75 |

[21] |

8.8.2. Sensitivity Analysis

We conduct sensitivity analysis for the competitiveness index:

Results show greatest sensitivity to technical capability () and governance effectiveness ().

8.9. Algorithmic Implementation

8.9.1. AI Literacy Assessment Algorithm

- 1:

procedureAssessAILiteracy()

- 2:

- 3:

fordo

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

end for

- 7:

return

- 8:

end procedure

8.9.2. Optimization Algorithm for Resource Allocation

- 1:

procedureOptimizeAllocation()

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

whiledo

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

end while

- 10:

return

- 11:

end procedure

8.10. Visualization of Mathematical Relationships

Figure 9.

AI adoption curves: Bass diffusion model applied to U.S. and China (parameters from [

8,

14])

Figure 9.

AI adoption curves: Bass diffusion model applied to U.S. and China (parameters from [

8,

14])

Figure 10.

Resource allocation optimization: Effectiveness vs. infrastructure investment fraction (based on [

8])

Figure 10.

Resource allocation optimization: Effectiveness vs. infrastructure investment fraction (based on [

8])

8.11. Conclusion of Quantitative Analysis

The mathematical models presented in this section provide rigorous foundations for analyzing AI literacy and adoption dynamics. Key insights include:

Differential Adoption Patterns: China shows higher market potential () but lower innovation coefficient () compared to the U.S.

Resource Allocation Optimization: Optimal allocation for U.S. K-12 prioritizes infrastructure (35%) and teacher training (25%), consistent with empirical findings.

Risk-Governance Tradeoffs: The multi-objective optimization framework captures inherent tensions between innovation promotion and risk mitigation.

Network Effects Matter: Ecosystem connectivity () significantly impacts knowledge diffusion and adoption rates.

These quantitative methods enable more precise comparison of U.S. and Chinese approaches, supporting evidence-based policy recommendations and strategic planning.

9. Figure Descriptions and References

This section provides comprehensive descriptions of all figures included in the paper, detailing their content, purpose, and relationships to the analysis.

9.1. AI-Enhanced Education Architecture

Figure 1 presents a three-layer architectural framework for AI-enhanced education systems, integrating:

Application Layer: User-facing components including AI-enhanced learning platforms, personalized tutoring systems, intelligent assessment tools, and VR/AR learning environments.

Orchestration Layer: Middleware components for API gateways, multi-agent coordination, and workflow automation.

Data & Governance Layer: Infrastructure components for learning data repositories, model registry/versioning, and privacy/security/ethics management.

The architecture synthesizes elements from both U.S. and Chinese approaches, showing vertical integration and horizontal data flows with governance feedback loops.

9.2. Strategic Roadmap for Agentic AI Leadership

Figure 2 illustrates a phased strategic roadmap (2025–2032) with:

Four Phases: Foundation (standards development), Pilots (sectoral implementation), Scaling (cross-sector integration), and Maturation (sustainable ecosystems).

Quantitative Parameters: Infrastructure effectiveness (), systemic barriers (), innovation coefficient (p), market potential (M), and regulatory effectiveness ().

Geopolitical Dynamics: U.S. strategic focus on interoperability and democratic values vs. Chinese focus on centralized governance and industrial integration.

Convergence Pathways: Shows potential hybrid governance frameworks emerging from strategic competition.

9.3. Comparative AI Governance Framework

Figure 3 provides a compact comparative framework across three major geopolitical actors:

United States: Sectoral, market-driven approach with emphasis on innovation and interoperability.

European Union: Risk-based, rights-focused approach emphasizing ethical frameworks and precautionary principles.

China: Comprehensive, state-led approach focusing on national security and industrial policy.

The figure highlights strategic dynamics (competition, divergence, rivalry) and identifies a convergence zone for hybrid governance models.

9.4. U.S. AI Export Leadership Framework

Figure 4 depicts a multi-layer architecture for U.S. AI export leadership:

Strategic Layer: National security considerations, competitive positioning, international alliances.

Governance Layer: Export control compliance, industry consortia structures, risk assessment frameworks.

Technical Layer: Modular architecture design, automated compliance systems, security integration.

Market Layer: Market segmentation, deployment models, capacity building programs.

The framework addresses implementation complexity across these interconnected layers.

9.5. AI Literacy in Chinese Shadow Education

Figure 5 illustrates a five-dimensional AI literacy framework for Chinese EFL practitioners:

Core Dimension: Human-centered mindset at the center.

Surrounding Dimensions: Knowledge (technical understanding), Application (tool usage), Ethics (responsible use), and Societal (equity and justice).

Interconnections: Shows relationships between dimensions and their impact on student engagement, pedagogical innovation, and curriculum adaptation.

Context: Situated within the Chinese shadow education (private tutoring) sector with EFL focus.

9.6. Agentic AI in Healthcare Governance

Figure 6 presents a decision-theoretic framework for agentic AI governance in healthcare:

Model Selection: Decision between open-source (transparency advantage) and proprietary (reliability focus) models.

Risk Stratification: Classification into high-risk (critical care) and low-risk (administrative) applications.

Adaptive Governance: International certification, federated learning, and adaptive policymaking mechanisms.

Quantitative Metrics: Includes cost savings (), error reduction (), and implementation metrics.

Optimization Outcomes: Equitable access, patient safety, innovation balance, and regulatory effectiveness.

9.7. U.S. K-12 AI Competitiveness Framework

Figure 8 illustrates a multi-phase framework for enhancing U.S. K-12 AI literacy:

Four Phases: Foundation (teacher training), Integration (curriculum design), Expansion (school-wide AI), and Maturation (systemic impact).

Outcomes: Student STEM engagement, computational thinking, and teacher preparedness with quantitative improvements.

International Benchmarking: Compares U.S., Chinese, and Finnish educational systems.

Optimization: Shows resource allocation optimization with budget constraints.

9.8. Adoption Curves and Resource Optimization

Figure 9 visualizes AI adoption dynamics using the Bass diffusion model:

Figure 10 shows resource allocation optimization:

Optimal Mix: Maximizes system effectiveness through balanced investment across infrastructure, training, curriculum, assessment, and research.

Marginal Returns: Illustrates diminishing returns on investment in individual categories.

9.9. Figure Relationships and Analytical Purpose

The figures collectively serve several analytical purposes:

Architectural Design:Figure 1,

Figure 4 provide structural frameworks for system implementation.

Strategic Planning:Figure 2,

Figure 8 offer phased roadmaps with quantitative milestones.

Decision Support:Figure 6 provide decision-theoretic frameworks for complex choices.

Quantitative Modeling:Figure 9,

Figure 10 visualize mathematical relationships and optimization outcomes.

Each figure incorporates elements from the reviewed literature, with citations indicating the source material informing the visual representations. The figures collectively enhance understanding of complex multidimensional relationships in AI literacy, adoption, governance, and strategic competition.

10. Conclusion and Recommendations

10.1. Summary of Findings

This comparative analysis of U.S. and Chinese strategic frameworks for AI literacy and adoption reveals fundamentally different governance architectures. The U.S. model is characterized by decentralized innovation, multi-stakeholder governance, and interoperability, whereas China employs centralized planning, state-led implementation, and comprehensive regulation [

1,

3]. Both systems exhibit distinct strengths and challenges in equity, ethical governance, and international positioning [

2].

The emergence of agentic AI intensifies competitive dynamics and necessitates advanced governance frameworks [

4,

5]. Quantitative modeling—including literacy scoring (Eq. ), Bass diffusion adoption (Eq.

13), risk assessment (Eq. ), and regulatory effectiveness indices (Eq. )—provides a data-driven foundation for comparative analysis.

10.2. Recommendations

Based on the analysis, we propose the following evidence-based recommendations:

Hybrid Governance Models: Implement tiered regulatory frameworks integrating U.S. innovation mechanisms with Chinese oversight structures [

6,

21].

Comprehensive AI Literacy Initiatives: Develop multi-stakeholder educational programs with emphasis on technical, ethical, and practical competencies [

13,

15].

International Standards Collaboration: Pursue interoperable technical standards through multilateral engagement [

19,

24].

Joint Research on Agentic AI Safety: Establish multilateral research initiatives addressing safety, ethics, and verification of autonomous systems [

5,

23].

Content Provenance Frameworks: Implement metadata-based content labeling systems balancing transparency and scalability [

20,

22].

Ethical Innovation Incentives: Design incentive structures rewarding ethical compliance and societal benefit alongside technical performance [

2,

17].

Dual-Use Technology Governance: Develop clear frameworks for military-civilian AI integration with appropriate safeguards [

7,

18].

Emerging Technology Monitoring: Continuously assess adjacent technological developments (quantum, neurotech, XR) for AI governance implications [

26].

10.3. Future Research Directions

Future research should prioritize: (1) longitudinal validation of quantitative models with empirical data; (2) sector-specific implementation studies beyond healthcare and education; (3) expansion of analysis to include EU and other AI actors; (4) hardware and semiconductor supply chain dependencies; and (5) geopolitical implications of agentic AI proliferation [

1,

2,

4].

Declaration

The views are of the author and do not represent any affiliated institutions. Work is done as a part of independent research. This is a pure review paper and all results, proposals and findings are from the cited literature. Author does not claim any novel findings.

References

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, Z. Artificial Intelligence Policy Frameworks in China, the European Union and the United States: An Analysis Based on Structure Topic Model. 212, 123971. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.B.L. A Principled Governance for Emerging AI Regimes: Lessons from China, the European Union, and the United States. 3, 793–810. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.; Cowls, J.; Hine, E.; Morley, J.; Wang, V.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. Governing Artificial Intelligence in China and the European Union: Comparing Aims and Promoting Ethical Outcomes. 39, 79–97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S. Advancing U.S. Competitiveness in Agentic Gen AI: A Strategic Framework for Interoperability and Governance. pp. 1480–1496. [CrossRef]

- ——. National Framework for Agentic Generative AI in Cancer Care: Policy Recommendations and System Architecture. [Online]. Available: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202509.1100/v1.

- ——, “Regulatory Reform for Agentic AI: Addressing Governance Challenges in Federal AI Adoption.” [Online]. Available: https://zenodo.org/records/17808694.

- Qiao-Franco, G.; Bode, I. Weaponised Artificial Intelligence and Chinese Practices of Human–Machine Interaction. 16, 106–128. [CrossRef]

- S. Joshi, “Enhancing U.S. K-12 Competitiveness for the Agentic Generative AI Era: A Structured Framework for Educators and Policy Makers.” [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED676035.

- An Agentic AI-Enhanced Curriculum Framework for Rare Earth Elements from K-12 to Veteran Training for Educators and Policy Makers. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED676389.

- A Comprehensive Framework for U.S. AI Export Leadership: Analysis, Implementation, and Strategic Recommendations. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/17823269.

- N. S. Institute. The Value of Values: Competing with China in an AI-Enabled World. Medium. [Online]. Available: https://thescif.org/the-value-of-values-competing-with-china-in-an-ai-enabled-world-95a323de654d.

- Rehman, N.; Huang, X.; Sarwar, U.; Mahmood, A.; Dignam, C. China’s AI Policy in Higher Education: Opportunities and Challenges. In Navigating Barriers to AI Implementation in the Classroom; IGI Global Scientific Publishing; pp. 67–92. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Y.Y.; He, L. AI Literacy in Shadow Education: Exploring Chinese EFL Practitioners’ Perceptions and Experiences. 5, 215–242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Lei, V.N.L. AI Adoption in Chinese Universities: Insights, Challenges, and Opportunities from Academic Leaders. 258, 105160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Asgarova, V.; Hashmi, Z.F.; Ngajie, B.N.; Asghar, M.Z.; Järvenoja, H. Exploring Faculty Experiences with Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools Integration in Second Language Curricula in Chinese Higher Education. 28, 128. [CrossRef]

- Future of education in the era of generative artificial intelligence: Consensus among Chinese scholars on applications of ChatGPT in schools - Liu - 2023 - Future in Educational Research - Wiley Online Library. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fer3.10.

- You, Z.; Lin, C.; Guo, M.; Qi, K. AI Literacy and Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Chinese Corporations: Mediating Role of Innovation Consciousness. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th Asia-Pacific Artificial Intelligence and Big Data Forum. Association for Computing Machinery AIBDF ’24, 194–201. [CrossRef]

- S. Joshi, “Reskilling the U.S. Military Workforce for the Agentic AI Era: A Framework for Educational Transformation.” [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED677111.

- Joshi, Satyadhar. Securing U.S. AI Leadership: A Policy Guide for Regulation, Standards and Interoperability Frameworks. 16, 001–026. [CrossRef]

- China’s AI Content Labeling Revolution: What Global Organizations Need to Know About the World’s Most Comprehensive AI Transparency Framework. Compliance Hub Wiki. [Online]. Available: https://www.compliancehub.wiki/chinas-ai-content-labeling-revolution-what-global-organizations-need-to-know-about-the-worlds-most-comprehensive-ai-transparency-framework/.

- Zhu, Y.; He, B.; Fu, H.; Hu, N.; Wu, S.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H. China’s Emerging Regulation toward an Open Future for AI. 390, 132–135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S. Regulatory Frameworks for Generative AI Enabled Digital Mental Health Devices: Safety, Transparency, and Post-Market Oversight.

- ——. Framework for Government Policy on Agentic and Generative AI in Healthcare: Governance, Regulation, and Risk Management of Open-Source and Proprietary Models. [Online]. Available: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202509.1087/v1.

- China unveils global AI governance action plan framework. PPC Land. [Online]. Available: https://ppc.land/china-unveils-global-ai-governance-action-plan-framework/.

- family=Noort, given=Carolijn, p.u. On the Use of Pride, Hope and Fear in China’s International Artificial Intelligence Narratives on CGTN. 39, 295–307. [CrossRef]

- The Chinese metaverse: An analysis of China’s policy agenda for extended reality (XR) - Gray - 2025 - Policy & Internet - Wiley Online Library. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/poi3.418.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).