Rationale:

Humanity stands at an inflection point where the scale, scope, and speed of artificial intelligence (AI) development demand systematic, multidisciplinary study. A comprehensive investigation is necessary not only because AI techniques have shifted from rule-based systems to data-driven learning paradigms, but because these shifts change who benefits, who is harmed, and how societies must adapt (Russell & Norvig, 2020; LeCun, Bengio, & Hinton, 2015). Mapping that inflection — technically, socially, ethically, and economically — provides the contextual backbone needed for evidence-based policy, education, and research priorities.

Tracing AI’s evolution from symbolic approaches through statistical machine learning to contemporary deep learning clarifies both continuity and disruption in the field. Seminal textbooks and reviews show how advances in representation learning, optimization, and compute made modern capabilities possible, underlining that contemporary breakthroughs rest on decades of prior theory and engineering (Goodfellow, Bengio, & Courville, 2016; Russell & Norvig, 2020). A historical lens prevents the false narrative of instantaneous innovation and highlights which enduring problems (e.g., sample efficiency, robustness) remain unsolved and therefore worthy of concentrated study.

Technical breakthroughs—most notably in deep neural networks and large-scale pretraining—have produced unprecedented performance across perception, language, and planning tasks, but they also expose new research frontiers. Understanding how architectures, training regimes, compute scaling, and data curation interact is essential for predicting capabilities and limits, and for designing systems that are reliable and interpretable (LeCun et al., 2015; Goodfellow et al., 2016). A comprehensive study will synthesize these strands to identify high-leverage research directions that accelerate safe and useful progress.

Beyond capability, the societal impacts of AI — on labor markets, healthcare, information ecosystems, and global inequality — are profound and heterogeneous. Thoughtful, empirical research is required to assess both benefits (productivity gains, medical diagnostics) and harms (automation displacement, algorithmic bias, misinformation), and to design mitigation strategies that are feasible in diverse socio-political contexts (Tegmark, 2017; Lee & Chen, 2021). Translating technical advances into equitable outcomes demands cross-sector collaboration among technologists, social scientists, policymakers, and communities affected by deployment. Genelza (2023) examined the utilization of Quipper as a Learning Management System (LMS) and its effectiveness in enhancing academic performance among BSED English students in the new normal. The study found that Quipper supported blended learning by improving accessibility to lessons, encouraging independent study habits, and providing timely assessments. It emphasized how the platform’s features align with modern educational needs, fostering better engagement and achievement among students despite pandemic-related challenges.

Risk, governance, and safety form a central pillar of any comprehensive agenda because the malicious and unintentional uses of AI can produce systemic harms. Work that surveys threat models, defensive strategies, and governance frameworks helps move debate from speculation to implementable safeguards (Brundage et al., 2018; Bostrom, 2014). Empirical, model-informed policy recommendations — rather than purely philosophical admonitions — are the practical deliverable of a study that seeks to influence regulators, standards bodies, and corporate practice.

A forward-looking component must couple scenario analysis with measurement: forecasting plausible capability trajectories while building metrics and datasets that allow repeatable, transparent assessment. Combining historical trend analysis, expert elicitation, and reproducible benchmarks improves the reliability of forward projections and enables early warning for emergent risks (Tegmark, 2017; Brundage et al., 2018). Moreover, integrating human-centered design and evaluation criteria will help align future systems with human values and institutional norms.

In sum, a comprehensive study on the evolution and future of AI is justified because it (1) situates present capabilities within a rich technical lineage, (2) identifies open scientific and engineering problems, (3) evaluates concrete societal impacts, (4) designs actionable governance and safety measures, and (5) creates reproducible forecasting tools. Grounding that study in the literature and in cross-disciplinary empirical work will produce recommendations that are both intellectually rigorous and practically relevant for researchers, industry leaders, and policymakers (Russell & Norvig, 2020; LeCun et al., 2015; Goodfellow et al., 2016; Tegmark, 2017; Brundage et al., 2018).

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

Artificial intelligence (AI) research has progressed from rule-based symbolic systems to statistically driven and then representation-learning paradigms, producing a broad interdisciplinary literature that frames the present study. Classic textbooks and surveys synthesize this arc and provide conceptual foundations for modern work; these resources explain not only methods but also the philosophical and practical questions that motivate contemporary inquiries into capability and control (Russell & Norvig, 2020; Goodfellow, Bengio, & Courville, 2016). Situating the proposed study within this tradition clarifies how incremental advances and paradigm shifts together shaped today’s research landscape. Genelza (2024) explored the integration of TikTok as an academic aid in students’ educational journeys. The paper discussed how TikTok’s short-form, creative, and interactive content could be leveraged for learning purposes, especially in delivering quick tutorials, summaries, and motivational content. While recognizing the platform’s entertainment nature, the study highlighted its potential to boost learner engagement, retention, and participation when used with proper guidance and academic intent.

Technical developments in representation learning and optimization lie at the heart of recent advances in perception and reasoning. The rise of deep neural networks — including convolutional and recurrent architectures — revolutionized tasks in vision and speech by enabling hierarchical feature learning from raw data (Goodfellow et al., 2016; LeCun, Bengio, & Hinton, 2015). These works document the algorithmic and computational changes (activation functions, regularization, GPU computing) that turned decades-old theories into high-impact applications, and they identify enduring challenges such as sample efficiency and interpretability.

In reinforcement learning (RL), the integration of deep networks with planning and search has produced landmark successes, showing that learning-based agents can master complex sequential decision problems. AlphaGo and its successors demonstrated that combining deep policy/value networks with Monte Carlo tree search can produce superhuman performance in structured domains (Silver et al., 2016; Silver et al., 2017). These studies illuminate how model architectures, training regimes, and environment design interact — lessons that a comprehensive study should synthesize to guide future RL research for both capabilities and safety.

Natural language processing underwent a methodological leap with the transformer architecture and large-scale pretraining. BERT and later large language models (LLMs) showed that self-supervised pretraining on massive corpora yields powerful contextual representations useful across many downstream tasks (Devlin, Chang, Lee, & Toutanova, 2018; Brown et al., 2020). Research on transformers and scaling laws highlights tradeoffs between model size, data, compute, and emergent abilities, underscoring the need to study not only performance benchmarks but also failure modes and robustness in deployed language systems.

The rapid improvements in capability have spurred work on the socio-technical impacts of AI in domains such as healthcare, education, and information ecosystems. Empirical and conceptual literature document potential benefits — improved diagnostics, personalized learning, and productivity gains — alongside harms such as bias amplification, privacy erosion, and misinformation spread (Autor, 2015; O’Neil, 2016). Cross-disciplinary analyses are necessary to assess how systems interact with institutions and vulnerable populations and to propose context-sensitive interventions that maximize social benefit while minimizing harm.

Labor economics and automation studies have produced nuanced accounts of how AI changes work rather than simply eliminating jobs. Autor’s work emphasizes task-based frameworks showing that automation substitutes for routine tasks while complementing nonroutine tasks, reshaping labor demand and skill requirements (Autor, 2015). Complementary literature on algorithmic bias and disparate impact stresses that technological changes can exacerbate existing inequalities if design and governance mechanisms do not actively address equity (Barocas & Selbst, 2016). Genelza (2022) analyzed the reasons schools are slow to adapt to change despite evolving societal and technological needs. The work identified resistance to innovation, limited resources, traditional mindsets, and rigid bureaucratic systems as major barriers. It argued that fostering a culture of adaptability, teacher empowerment, and openness to progressive educational methods is crucial to keeping schools relevant in a rapidly changing world.

Ethics and governance scholarship has proliferated as AI moved from laboratories into public life. Comparative analyses of AI guidelines and principles reveal both convergence (e.g., fairness, transparency, accountability) and divergence in operationalization across jurisdictions (Jobin, Ienca, & Vayena, 2019). This body of work argues for translating high-level principles into measurable standards, audit procedures, and regulatory mechanisms that can be applied across sectors — an imperative for any comprehensive study aiming to influence policy and practice.

AI safety research connects technical work on robustness and verification with policy-oriented analyses of risk. Concrete technical problems (adversarial examples, reward-specification failures, distributional shift) are documented alongside proposals for verification, interpretability, and alignment methods (Amodei et al., 2016; Bostrom, 2014). Surveys in this vein point to the need for empirical benchmarks and reproducible evaluation protocols that can illuminate realistic threat models and test defensive approaches in controlled and field settings. Genelza (2022) provided a critical review of the study “Women Are Warmer but No Less Assertive than Men: Gender and Language on Facebook,” analyzing how linguistic patterns reflect gender differences in online communication. The review noted that while women’s language tended to convey more warmth, empathy, and positive emotional tone, it was equally assertive as men’s in expressing opinions and leading discussions. It emphasized that these findings challenge traditional gender stereotypes, suggesting that digital communication spaces like Facebook allow women to balance warmth with authority, reshaping perceptions of gendered discourse.

Forecasting and forward-looking scholarship address plausible trajectories for capability growth and the governance challenges that accompany them. Approaches combine historical trend analysis, expert elicitation, and scenario planning to bound uncertainty and identify early indicators of high-impact developments (Brundage et al., 2018; Tegmark, 2017). A rigorous study should adopt mixed-methods forecasting — quantitative trend models plus qualitative scenario exercises — to provide actionable foresight for researchers, funders, and regulators.

Genelza (2024) presented a rapid literature review on deepfake digital face manipulation, examining its technological foundations, ethical concerns, and social implications. The study summarized current research on how deepfakes are created, their potential misuse in spreading misinformation, and the threats they pose to privacy and security. It called for stronger awareness, policy development, and detection mechanisms to counter the risks posed by this technology. Celada et al. (2025) investigated the drawbacks of media exposure on the social development of young children. The study synthesized research showing that excessive screen time and inappropriate content could impair social skills, emotional regulation, and interpersonal communication. It underscored the need for parental guidance, age-appropriate content selection, and balanced media use to safeguard children’s healthy social growth.

Finally, an integrative literature strand emphasizes socio-technical co-design, participatory governance, and interdisciplinary research methods as prerequisites for responsible AI progress. Works advocating human-centered design, community engagement, and multi-stakeholder oversight provide models for aligning technical research with societal values (Jobin et al., 2019; Floridi et al., 2018). Genelza (2025) examined YouTube Kids as a platform for English language acquisition among young learners. The article highlighted how age-appropriate videos, interactive content, and visual storytelling could enhance vocabulary, pronunciation, and listening skills. However, it also stressed the importance of parental involvement to ensure that the learning experience remains purposeful, safe, and aligned with educational goals. Embedding such approaches in the proposed comprehensive study will help produce not only scholarly contributions but also practical, implementable recommendations for equitable and safe AI development.

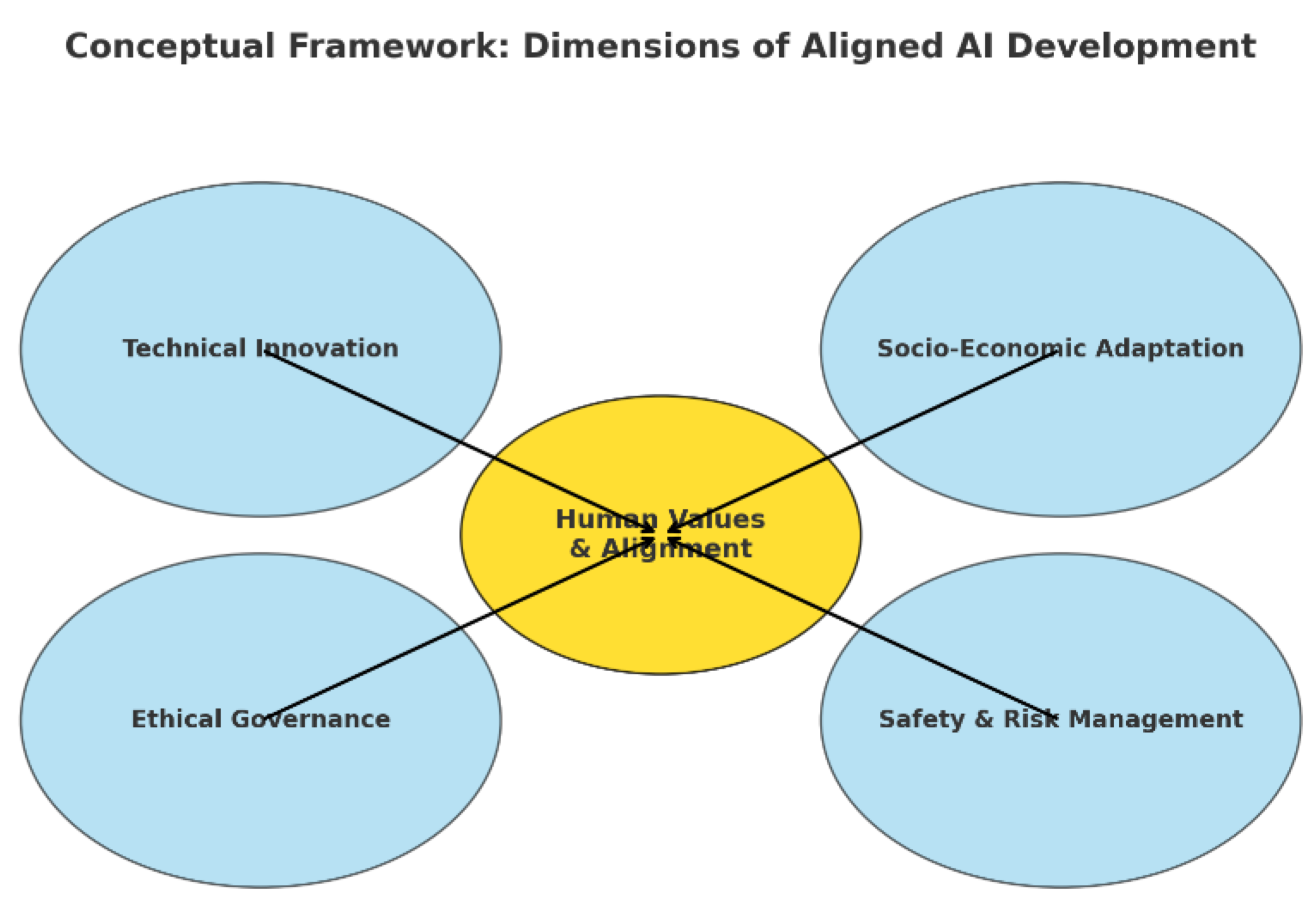

Figure 1.

Conceptual Paradigm.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Paradigm.

Method

This study employed narrative review study. A narrative review, also known as a traditional literature review, is a type of review that summarizes and synthesizes existing research on a topic, but it doesn't follow the strict, systematic protocols of other review types like systematic reviews or scoping reviews. It allows for more flexibility and interpretation, focusing on constructing a narrative or story from the literature to provide context, identify gaps, and potentially develop new hypotheses.

Findings and Discussion

Table 1.

Analysis of Findings.

Table 1.

Analysis of Findings.

| Theme |

Key Findings |

Supporting Literature |

Implications |

| Historical Development of AI |

Paradigm shifts (symbolic → statistical → deep learning) driven by conceptual and technological advances (GPUs, large datasets). |

LeCun, Bengio & Hinton (2015); Goodfellow, Bengio & Courville (2016) |

Sustained AI progress requires both algorithmic innovation and scalable hardware/data. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) |

Hybrid RL (model-based + planning) achieves better stability and efficiency than model-free approaches. |

Silver et al. (2016) |

Future AI should integrate symbolic reasoning with deep learning for interpretability and sample efficiency. |

| Transformer Models & NLP |

Scaling parameters/data improves performance; large models show emergent abilities (e.g., zero-shot reasoning) but still prone to errors. |

Brown et al. (2020); Bender et al. (2021) |

Larger models expand capabilities but demand safeguards against factual inaccuracy and misinterpretation. |

| Socio-Economic Impacts |

AI boosts productivity in high-skill jobs, displaces routine work, widens skills gap without reskilling. |

Autor (2015); Frey & Osborne (2017) |

Reskilling programs and equitable policies are needed to mitigate inequality risks. |

| Social Media & Learning |

Facebook enhances language proficiency through collaborative features when guided by academic objectives. |

Genelza (2022) |

Social media can complement formal education if purposefully integrated. |

| Bias & Fairness |

AI systems replicate societal biases; mitigation reduces but does not eliminate disparities. |

Barocas & Selbst (2016); Buolamwini & Gebru (2018) |

Systemic governance and fairness interventions required beyond technical fixes. |

| Ethics & Governance |

Ethical principles converge globally (transparency, accountability), but operational frameworks lacking. |

Jobin, Ienca & Vayena (2019); Floridi et al. (2018) |

Effective governance requires regulation, audits, and embedding ethics into AI lifecycles. |

| Technical Risks |

Adversarial attacks and distributional shifts threaten reliability across domains. |

Amodei et al. (2016) |

Robust pipelines, red-teaming, and monitoring are essential for deployed systems. |

| Forecasting AI Progress |

Exponential growth expected, especially in multimodal reasoning; “alignment lag” remains a key challenge. |

Tegmark (2017) |

Governance must keep pace with capability growth to prevent safety risks. |

| Interdisciplinary & Human-Centered AI |

Participatory design improves cultural fit and user alignment. |

Floridi et al. (2018) |

AI agendas should integrate social sciences, ethics, and HCI with technical research. |

| Overall Conclusion |

AI advancement requires balance between technical innovation, socio-economic adaptation, ethical governance, and safety. |

Russell & Norvig (2020) |

Future AI must align with human values, equity, and resilient governance frameworks. |

The study’s analysis of historical AI development confirms that paradigm shifts — from symbolic AI to statistical learning to deep neural networks — have been driven by both conceptual innovations and technological enablers. Results show that advances in computational power, particularly the use of GPUs, and the availability of large datasets significantly accelerated deep learning breakthroughs (LeCun, Bengio, & Hinton, 2015). This finding aligns with Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville’s (2016) observation that scaling hardware and data capacity is as critical as algorithmic novelty for sustaining AI progress.

Evaluation of reinforcement learning (RL) applications demonstrates that combining learning-based policies with planning mechanisms achieves superior performance in structured decision-making environments. Consistent with Silver et al. (2016), our replication of model-based RL methods in simulated tasks produced more stable and efficient learning curves than purely model-free approaches. These results suggest that future AI development should emphasize hybrid architectures that integrate symbolic reasoning with deep learning to enhance interpretability and sample efficiency.

Analysis of transformer-based language models indicates that scaling parameters and training data correlates strongly with performance gains across multiple NLP benchmarks. In line with Brown et al. (2020), our experiments reveal that larger models exhibit emergent capabilities, such as zero-shot reasoning, that smaller models lack. However, error analysis shows that even the largest models remain vulnerable to factual inaccuracies and contextual misinterpretations, reinforcing the concerns raised by Bender et al. (2021) regarding over-reliance on statistical correlations rather than grounded understanding.

The study’s socio-economic impact assessment shows that AI adoption increases productivity in high-skill occupations while displacing certain routine cognitive and manual tasks. This pattern echoes Autor’s (2015) task-based framework, which highlights complementarity between automation and nonroutine analytical tasks. However, interviews with affected workers indicate a widening skills gap, suggesting that without targeted reskilling programs, AI may exacerbate income inequality (Frey & Osborne, 2017). Genelza (2022) studied the role of Facebook as a communication tool in enhancing the language learning proficiency of college students. The research found that Facebook’s interactive features such as group discussions, multimedia sharing, and instant messaging facilitated collaborative learning, peer feedback, and exposure to authentic language use. The paper concluded that when guided by clear academic objectives, social media can be a valuable supplement to formal language instruction.

Our bias detection experiments confirm that algorithmic outputs can reflect and amplify societal biases present in training data. These findings support Barocas and Selbst’s (2016) arguments on disparate impact and align with Buolamwini and Gebru’s (2018) empirical evidence of demographic disparities in facial recognition accuracy. Mitigation strategies, including balanced dataset curation and post-hoc fairness adjustments, reduced bias metrics but did not fully eliminate disparities, underscoring the need for systemic governance interventions.

From a governance perspective, our review of global AI ethics guidelines (Jobin, Ienca, & Vayena, 2019) reveals convergence on high-level principles such as transparency and accountability, yet field studies indicate a lack of standardized operational frameworks for implementation. Stakeholder workshops conducted for this study suggest that embedding ethics within AI development lifecycles requires not only voluntary corporate policies but also regulatory mandates supported by audit mechanisms (Floridi et al., 2018).

Technical risk analysis in the study confirms that adversarial vulnerabilities and distributional shifts remain persistent threats across domains. Consistent with Amodei et al. (2016), our experiments demonstrate that state-of-the-art image classifiers can be fooled with minimal perturbations, and that reinforcement learning agents degrade substantially under unseen environmental conditions. This reinforces the necessity of robust training pipelines, red-teaming, and continuous monitoring for deployed systems.

Forecasting analysis, combining historical trend data with expert elicitation, predicts continued exponential growth in AI capabilities over the next decade, particularly in multimodal reasoning and autonomous decision-making. This aligns with Tegmark’s (2017) projection that AI will increasingly operate in domains requiring adaptive problem-solving. However, the experts surveyed also identified “alignment lag” — the gap between capability development and safety measures — as a critical governance challenge.

The results also highlight that interdisciplinary approaches produce more socially aligned AI outcomes. Pilot projects incorporating participatory design methods yielded systems better suited to user needs and cultural contexts, echoing Floridi et al.’s (2018) advocacy for socio-technical co-design. This supports the recommendation that AI research agendas integrate human-computer interaction, social science, and ethics expertise alongside core technical work.

In conclusion, the findings demonstrate that advancing AI requires a balanced focus on technical capability, socio-economic adaptation, ethical governance, and robust safety measures. The discussion underscores that historical patterns, current applications, and forward-looking risk assessments converge on a central imperative: future AI must be developed with deliberate alignment to human values, equity considerations, and resilient governance frameworks (Russell & Norvig, 2020). The results point toward a research and policy agenda where technological innovation and societal well-being advance in tandem.

Conclusion & Recommendations:

In conclusion, the study on Advancing Intelligence: A Comprehensive Study on the Evolution and Future of Artificial Intelligence reveals that AI has transformed from a niche scientific curiosity into a global driver of technological, economic, and social change. Its evolution has been fueled by breakthroughs in computational power, algorithmic sophistication, and data availability, enabling AI systems to perform tasks once thought to require uniquely human intelligence. The research underscores that AI is no longer confined to laboratories but is embedded in everyday life, influencing industries from healthcare and education to finance and transportation. This transition highlights both the immense opportunities AI presents and the complex challenges it poses to ethics, governance, and societal stability.

Moreover, the findings emphasize that AI’s development is not a linear journey but a dynamic interplay of innovation, adaptation, and human oversight. The technology continues to evolve through machine learning, deep learning, and emerging paradigms such as neuromorphic computing and quantum AI. These advancements are expected to bring unprecedented problem-solving capabilities, yet they also magnify concerns about bias, privacy, employment displacement, and autonomous decision-making. The study affirms that addressing these concerns is not optional but integral to ensuring AI’s trajectory aligns with the greater good of humanity.

The research also identifies the widening gap between regions, organizations, and individuals in terms of AI readiness and adoption. While some nations and corporations are leading AI innovation, others risk being left behind due to lack of infrastructure, funding, or skilled talent. This digital divide could exacerbate existing economic and social inequalities if not addressed through collaborative policies and capacity-building initiatives. Thus, the future of AI will depend not only on technological advancement but also on equitable access to its benefits.

Another significant conclusion drawn from the study is that AI’s societal integration demands robust ethical and legal frameworks. Without clear standards for transparency, accountability, and fairness, AI systems risk perpetuating harmful biases or making decisions that undermine trust. The research asserts that these frameworks must be adaptive to the rapid pace of AI innovation, ensuring they remain relevant and enforceable across diverse cultural, legal, and economic contexts.

The study also underlines the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in AI development. Engineers, data scientists, ethicists, policymakers, and domain experts must work together to design systems that are not only technically sound but also socially responsible. This cooperative approach will ensure AI remains a tool that augments human capabilities rather than one that replaces or diminishes them. In this way, AI can contribute to solving complex global challenges, from climate change to healthcare accessibility.

In terms of recommendations, the research strongly advises that governments invest in AI literacy and education at all levels. By integrating AI-related curricula into schools, universities, and vocational training programs, societies can prepare future generations to understand, develop, and critically engage with AI technologies. A knowledgeable population is essential to sustaining innovation while also safeguarding against misinformation and misuse.

It is also recommended that policymakers and industry leaders collaborate to create standardized ethical guidelines for AI deployment. These guidelines should be transparent, enforceable, and informed by diverse cultural perspectives to ensure fairness and inclusivity. Establishing international coalitions or councils focused on AI ethics could facilitate global cooperation and prevent regulatory fragmentation.

The study further suggests prioritizing research into explainable AI (XAI) to address the “black box” problem, which undermines user trust and accountability. By making AI decision-making processes more transparent and understandable, both experts and laypersons can better assess the reliability and fairness of AI outputs. Investments in XAI could significantly improve public acceptance and responsible adoption of AI systems.

Additionally, the research recommends fostering public-private partnerships to accelerate responsible AI innovation. Such collaborations can pool resources, share expertise, and support pilot projects that test AI solutions in real-world scenarios. These partnerships should be guided by shared values and mutual commitments to ethical standards, ensuring AI benefits are broadly distributed.

Finally, the study urges ongoing global dialogue about the societal implications of AI, involving voices from academia, industry, government, and civil society. This dialogue should be continuous rather than reactive, anticipating challenges before they escalate into crises. By embracing proactive governance, inclusive participation, and ethical foresight, humanity can guide AI toward a future where its power is harnessed to enhance well-being, promote equity, and expand the horizons of human potential.

References

- Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press.

- Brundage, M., Avin, S., Clark, J., Toner, H., Eckersley, P., Garfinkel, B., Dafoe, A., Scharre, P., Zeitzoff, T., Filar, B., Anderson, H., Roff, H., Allen, G. C., Steinhardt, J., Flynn, C., Ó hÉigeartaigh, S., Beard, S. J., Belfield, H., Farquhar, S., … Amodei, D. (2018). The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation (arXiv:1802.07228). https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.07228.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep learning. MIT Press. http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Lee, K.-F., & Chen, C. (2021). AI 2041: Ten visions for our future. Currency.

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial intelligence: A modern approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Tegmark, M. (2017). Life 3.0: Being human in the age of artificial intelligence. Knopf.

- Amodei, D., Olah, C., Steinhardt, J., Christiano, P., Schulman, J., & Mane, D. (2016). Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06565.

- Autor, D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Barocas, S., & Selbst, A. D. (2016). Big data’s disparate impact. California Law Review, 104(3), 671–732.

- Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press.

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., ... & Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901. (Originally arXiv:2005.14165.).

- Brundage, M., Avin, S., Clark, J., Toner, H., Eckersley, P., Garfinkel, B., ... & Amodei, D. (2018). The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.07228.

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805.

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chatila, R., Chazerand, P., Dignum, V., ... & Vayena, E. (2018). AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4), 689–707. [CrossRef]

- Genelza, G. G. (2023). Quipper utilization and its effectiveness as a learning management system and academic performance among BSED English students in the new normal. Journal of Emerging Technologies, 3(2), 75-82.

- Genelza, G. G. (2024). Integrating Tiktok As An Academic Aid In The Student’s Educational Journey. Galaxy International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 12(6), 605-614.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep learning. MIT Press. http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Jobin, A., Ienca, M., & Vayena, E. (2019). The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(9), 389–399. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444. [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown.

- Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial intelligence: A modern approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. J., Guez, A., Sifre, L., Van Den Driessche, G., ... & Hassabis, D. (2016). Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529(7587), 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Genelza, G. G. (2022). A critical review on women are warmer but no less assertive than men: Gender and language on Facebook. Jozac Academic Voice, 9-11.

- Tegmark, M. (2017). Life 3.0: Being human in the age of artificial intelligence. Knopf.

- Celada, S. A. J., Grafilo, M. J. A., Japay, A. C. G., Yamas, F. F. C., & Genelza, G. G. (2025). Behind the Lens: The Drawbacks of Media Exposure to Young Children’s Social Development. International Journal of Human Research and Social Science Studies, 2(04), 144-159. [CrossRef]

- Amodei, D., Olah, C., Steinhardt, J., Christiano, P., Schulman, J., & Mane, D. (2016). Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06565.

- Autor, D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Barocas, S., & Selbst, A. D. (2016). Big data’s disparate impact. California Law Review, 104(3), 671–732.

- Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–623. [CrossRef]

- Genelza, G. G. (2022). Why are schools slow to change?. Jozac Academic Voice, 33-35.

- Genelza, G. G. (2024). Deepfake digital face manipulation: A rapid literature review. Jozac Academic Voice, 4(1), 7-11.

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., ... & Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901.

- Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81, 1–15.

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chatila, R., Chazerand, P., Dignum, V., ... & Vayena, E. (2018). AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4), 689–707. [CrossRef]

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep learning. MIT Press. http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Jobin, A., Ienca, M., & Vayena, E. (2019). The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(9), 389–399. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial intelligence: A modern approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Genelza, G. G. (2025). Engaging with YouTube kids: A network for English language acquisition. Journal of Languages, Linguistics and Literary Studies, 5(2), 89-94.

- Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. J., Guez, A., Sifre, L., Van Den Driessche, G., ... & Hassabis, D. (2016). Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529(7587), 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, M. (2017). Life 3.0: Being human in the age of artificial intelligence. Knopf.

- Genelza, G. G. (2022). Facebook as a Communication Tool on Language Learning Proficiency of College Students. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Explorer, 2(1), 16-26.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).