1. Introduction

Teleoperation systems enable humans to control robots remotely, providing essential capabilities in environments that are hazardous, inaccessible, or otherwise unsafe for direct human intervention. This paradigm has become a key enabler in domains such as disaster response [

1,

2], radioactive material handling [

3], underwater exploration [

4,

5], and medical robotics [

6]. These systems enhance human safety and operational efficiency by allowing operators to perform precise manipulations from a distance.

However, conventional teleoperation interfaces often suffer from limited depth perception, restricted situational awareness, and non-intuitive control schemes. These limitations can lead to reduced task performance and operator fatigue [

7], particularly when dealing with complex robotic systems, such as dual-arm manipulators. While some recent approaches have explored solutions using miniature replicas of the robot [

8] or body motion tracking for VR-based teleoperation [

9], these methods typically provide limited immersion and lack comprehensive 3D spatial understanding of the remote workspace when the manipulation occurs in a different room or environment. In contrast, immersive technologies, particularly Virtual Reality (VR), can significantly improve spatial understanding and user engagement in teleoperation scenarios by enabling natural 3D interaction, head-tracked viewpoints, and controller-based motion tracking [

10].

Despite these advances, integrating VR with real-world robotic systems remains challenging. Many existing frameworks are restricted to simulation environments, lack real-time feedback, or require specialized hardware setups that hinder reproducibility and scalability [

11]. Furthermore, synchronization between virtual and physical robots demands robust communication architectures to ensure low latency and reliable control. Although Unity-based solutions are commonly used for such integrations, recent studies have shown that Unreal Engine 5 (UE) provides superior rendering performance, lower latency, and more stable data synchronization for robotics and teleoperation applications [

12,

13].

In this work, we present a unified VR framework for teleoperating dual-arm robotic manipulators that bridges simulation and physical implementation. Our system combines the Webots robotics simulator with Unreal Engine 5.6.1 to deliver a highly realistic and responsive immersive interface. Users can manipulate each arm’s end-effector using VR controllers, seamlessly transitioning between simulated and real robotic platforms without altering the control paradigm. This unified design enables efficient testing, training, and operation within the same VR environment.

Our approach further emphasizes modularity and real-time perception: a middleware abstraction layer decouples the VR application from the underlying robotics framework, and the operator is immersed in a digital twin augmented with a large, colored point-cloud reconstruction of the remote environment rendered efficiently on the GPU. We validate the proposal through technical performance measurements and a user study with bimanual manipulation tasks, demonstrating the feasibility of immersive VR as a unified interface for simulation and physical robot control.

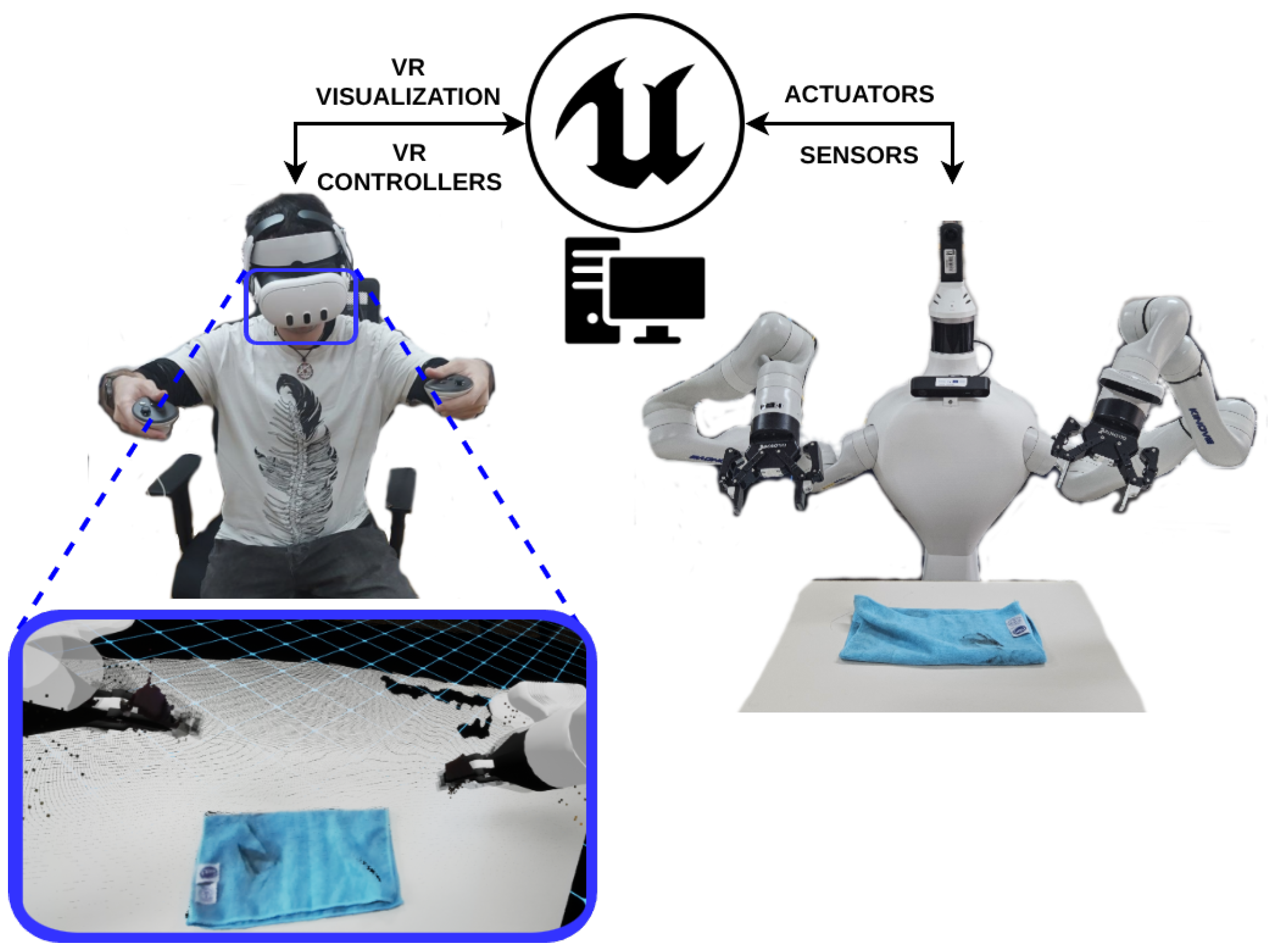

Figure 1 provides an at-a-glance overview of the proposed immersive teleoperation workflow. An operator equipped with a consumer VR headset and tracked controllers commands the end-effectors of a dual-arm system through a natural bimanual interaction, while being immersed in a synchronized digital twin of the remote scene. Crucially, the operator perspective is augmented with a dense 3D reconstruction (colored point cloud), which supports depth perception and collision-aware manipulation during contact-rich tasks such as cloth handling, and exemplifies the type of real-time feedback our framework maintains across both simulation-based development and real robot deployment.

The principal contributions of this paper are:

A unified VR teleoperation architecture that integrates Webots (simulation) and a physical dual-arm robot through the same Unreal Engine 5.6.1 immersive interface.

A modular communication design based on a middleware abstraction (static library) that enables replacing the robotics middleware (e.g., RoboComp/Ice, ROS2) without modifying the Unreal Engine application.

A real-time digital-twin workflow for dual-arm end-effector control using VR motion controllers, including continuous bidirectional synchronization and a safety-oriented dead-man switch mechanism.

A scalable 3D perception visualization pipeline that fuses multi-sensor point clouds and renders >1M colored points in VR via GPU-based Niagara, preserving interactive performance.

An experimental validation including (i) technical performance benchmarking of point-cloud rendering and (ii) a user study on six bimanual manipulation tasks reporting success and collision metrics.

Beyond its immediate applications in robotic research and industrial automation, our system opens possibilities for future extensions such as learning-based teleoperation, guided manipulation through mixed reality feedback, and multi-operator collaboration. The proposed architecture thus contributes to advancing VR-based teleoperation as a flexible and unified platform that integrates simulation, real-time perception, and physical robot control within a single immersive interface.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews recent work on XR-based teleoperation, digital twins, and 3D scene visualization for manipulation.

Section 3 presents the proposed system architecture and implementation, including the sim-to-real workflow, middleware abstraction, control loop, and dense point-cloud rendering pipeline.

Section 4 reports the technical benchmarks and the user-study results obtained with bimanual manipulation tasks. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the main findings, limitations, and directions for future work.

2. Related Works

Immersive and extended-reality (XR) interfaces have become a prominent direction to address long-standing limitations of classical teleoperation (e.g., restricted viewpoint control, weak depth cues, and high cognitive load). A systematic review by Wonsick and Padir highlights the rapid growth of VR interfaces for robot operation enabled by consumer-grade headsets and controllers, and discusses recurring design axes such as viewpoint management, control mapping, and scene representation fidelity [

14].

Several works since 2020 investigate VR as a more natural interface for dexterous manipulation. Hetrick et al. compared two VR control paradigms (positional/waypoint-like vs. trajectory/click-and-drag) to teleoperate a Baxter robot, and implemented a full VR environment that includes a live point-cloud reconstruction from a depth sensor alongside wrist-camera streams [

15]. De Pace et al. evaluated an “Enhanced Virtual Reality” teleoperation approach in which both robot and environment are captured with RGB-D sensors while the remote operator commands the robot motion through VR controllers [

16]. In industrial contexts, Rosen and Jha report that direct VR arm teleoperation becomes harder when low-level torque/velocity interfaces are not exposed and motion is mediated by proprietary position controllers; they propose filtering of VR command signals and demonstrate contact-rich manipulation on industrial manipulators [

17]. These studies strongly support VR’s usability benefits, but typically focus on a particular robot/control stack and do not target a unified pipeline that seamlessly spans simulation and physical execution under the same immersive interface.

A complementary line of work augments the operator’s perception through digital twins and reconstructed 3D scene cues. GraspLook proposes a VR telemanipulation system that replaces pure camera-based feedback with an augmented virtual environment, using an R-CNN to detect relevant instruments and render their digital twins; user results indicate reduced mental demand and faster execution in tube manipulation [

18]. IMMERTWIN introduces a mixed-reality framework built around a closed-loop digital twin, explicitly streaming a live colored point cloud (from multiple ZED cameras) into Unreal Engine 5.4, and reports a 26-participant evaluation across two robot platforms [

19]. For bimanual/dual-manipulator settings, García et al. propose an AR interface (HoloLens) combined with a gamepad to teleoperate bimanual industrial manipulators, aiming to reduce learning time and improve ergonomics relative to classic joystick-based interfaces [

20]. Gallipoli et al. propose a VR-based dual-mode teleoperation architecture with an explicit mode switch (“Approach” vs. “Telemanipulation”) to support safe and flexible remote manipulation [

21]. In parallel, configurable immersive baselines for online 3D reconstruction such as VRTAB-Map (built around RTAB-Map SLAM) further emphasize the importance—and practical difficulty—of presenting evolving dense 3D reconstructions to operators during teleoperation missions [

22]. Despite this progress, scaling dense 3D reconstruction to high point counts while preserving interactive frame rates in VR, and doing so in a framework that remains portable across simulation and real robots, remains an open engineering challenge.

Recent toolkits also emphasize teleoperation as a means to collect high-quality demonstrations for learning-based robotics. OpenVR (SoftwareX 2025) provides an open-source VR teleoperation method using an Oculus headset to control a Franka Panda, explicitly motivated by the cost and difficulty of collecting demonstrations [

11]. GELLO proposes a low-cost, kinematically equivalent physical replica controller (3D printed + off-the-shelf motors) and reports comparisons against common low-cost alternatives such as VR controllers and 3D mice; it also demonstrates complex bimanual/contact-rich tasks [

8]. Tung et al. present a VR teleoperation system aimed at collaborative dataset collection, emphasizing immersive stereoscopic egocentric feedback and a taxonomy of human–robot collaborative tasks [

23]. While these efforts are highly relevant for data generation, they do not primarily address a unified sim/real immersive digital-twin workflow for dual-arm manipulation with high-density reconstructed 3D scene feedback.

In contrast to prior work, our proposal targets a single immersive interface that (i) unifies simulation and real-robot execution without changing the operator’s interaction paradigm, (ii) emphasizes modular middleware decoupling of the XR front-end from the robotics back-end, and (iii) delivers scalable, GPU-friendly rendering of dense colored point clouds within a synchronized dual-arm digital twin, validated via technical benchmarks and bimanual user tasks.

To facilitate a compact yet readable comparison, we summarize the representative works discussed above in two complementary tables.

Table 1 reports the main descriptive attributes of each approach (publication year, XR modality, validation on real hardware and/or simulation, and the type of 3D scene representation).

Table 2 preserves the full qualitative commentary by pairing each work with its key aspects and its relation to our proposal. Together, these tables highlight where prior systems concentrate (e.g., interface design, scene augmentation, or demonstration collection) and clarify the gap addressed by our unified sim-to-real dual-arm framework with middleware decoupling and scalable dense point-cloud rendering.

3. System Architecture and Implementation

3.1. System Overview

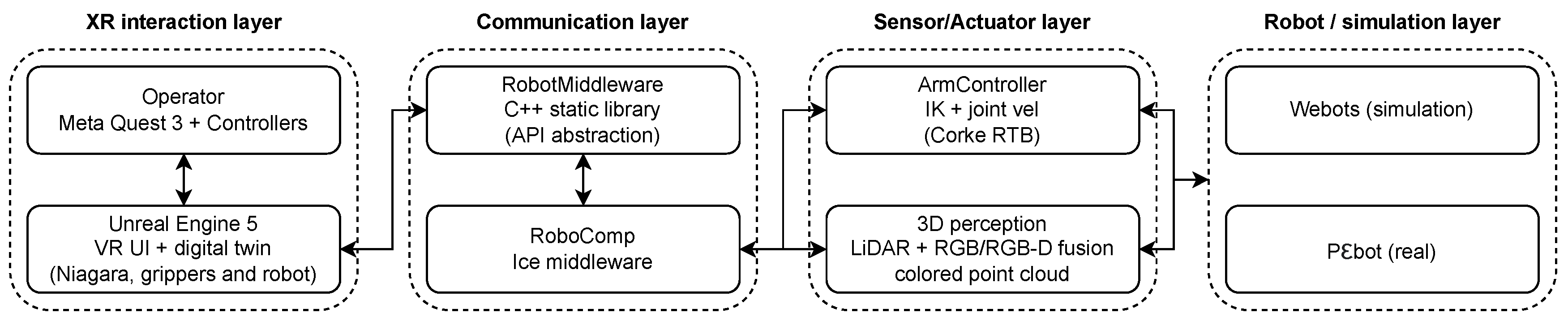

Figure 2 summarizes the proposed VR teleoperation framework and the data flow through four main layers: the XR interaction layer, the communication layer, the actuator/sensor layer, and the robot/simulator layer.

XR interaction Layer: The operator issues bimanual end-effector commands using a Meta Quest 3 headset and tracked controllers, while Unreal Engine renders the immersive interface. This interface includes the robot’s digital twin, the operator’s phantom grippers, and a dense colored point cloud rendered in real time via Niagara, providing the user with an intuitive control mechanism.

Communication Layer: Unreal Engine exchanges the target end-effector poses and feedback, such as robot state information, with a dedicated C++ abstraction layer, RobotMiddleware. This middleware bridges the XR front-end and the robotics back-end, such as RoboComp/Ice, ensuring seamless data transfer between the user interface and the robot.

Actuator/Sensor Layer: This layer is composed of two main components: the ArmController, which computes joint velocity commands via inverse kinematics with a safety mechanism (dead-man switch) for the end-effector, and the multi-sensor perception system, which fuses data into a dense colored point cloud.

Robot/Simulator Layer: The final layer consists of the physical robot Pbot or simulator Webots. It receives the commands from the Actuator/Sensor layer and executes them, performing the desired manipulation tasks.

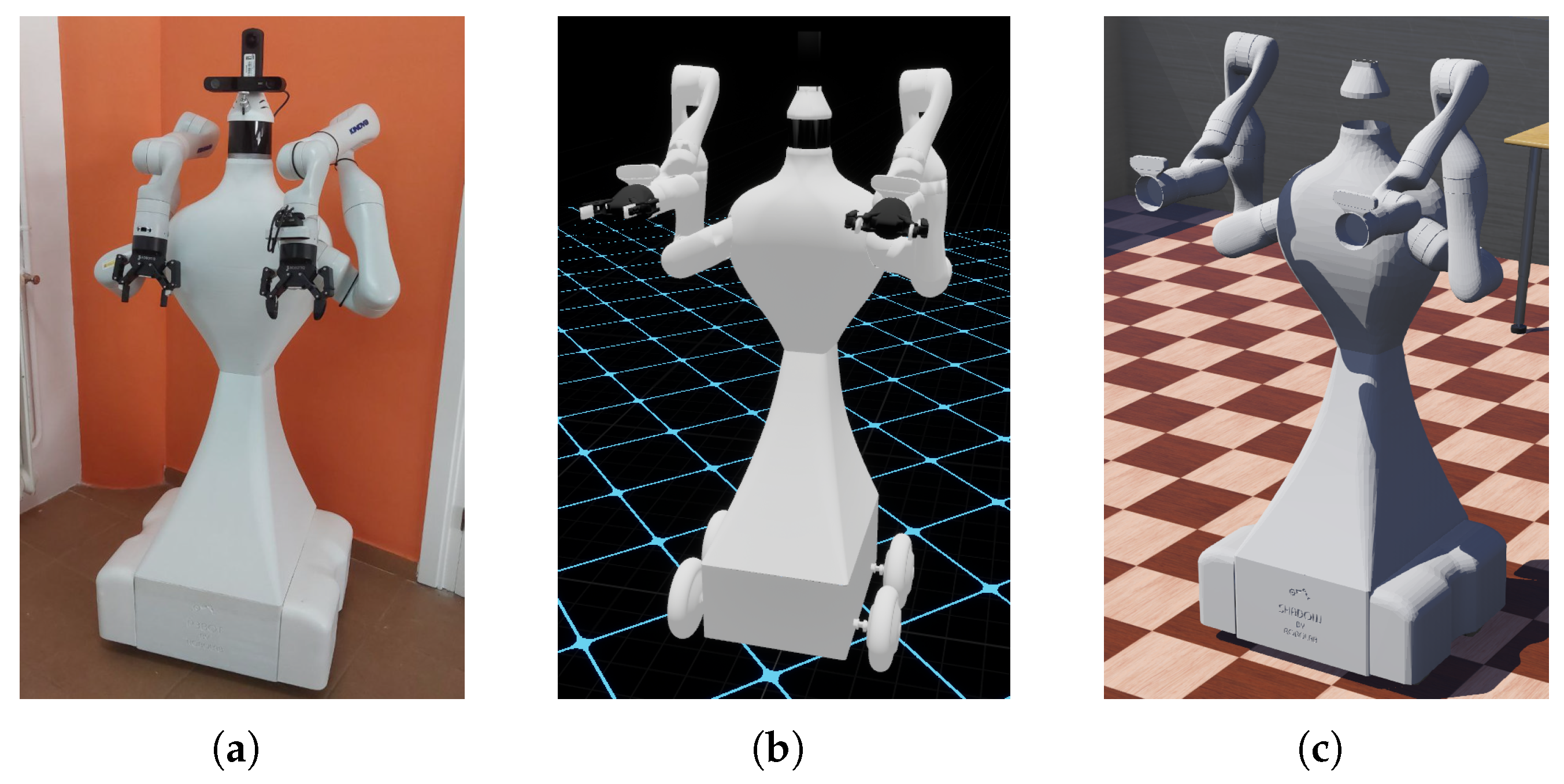

3.2. Robotic Platform and Digital Representations

We implemented our system on a custom dual-arm mobile robot, P

bot (

Figure 3a), equipped with two Kinova Gen3 7-DoF manipulators mounted on a mecanum-wheeled base. The sensory suite includes a Robosense Helios LiDAR, a ZED 2i stereo camera, and a Ricoh Theta 360° camera. All onboard computation runs under Ubuntu 24.04 with a Intel Core Ultra 9 Processor 185H and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Laptop GPU.

To support a unified workflow across simulation and real deployment, we created 3D assets of the robot for both Unreal Engine (

Figure 3b) and the Webots simulator (

Figure 3c). This alignment between the physical platform and its virtual counterparts enables the operator to interact through the same VR interface while maintaining coherent kinematics and visualization in both simulation and real-world teleoperation.

3.3. XR Runtime and Interaction in Unreal Engine

For immersive teleoperation, a Meta Quest 3 headset is used for Virtual Reality (VR) interaction. The headset connects to the main system via ALVR and SteamVR, which expose an API interface compatible with Unreal Engine 5.6.1.

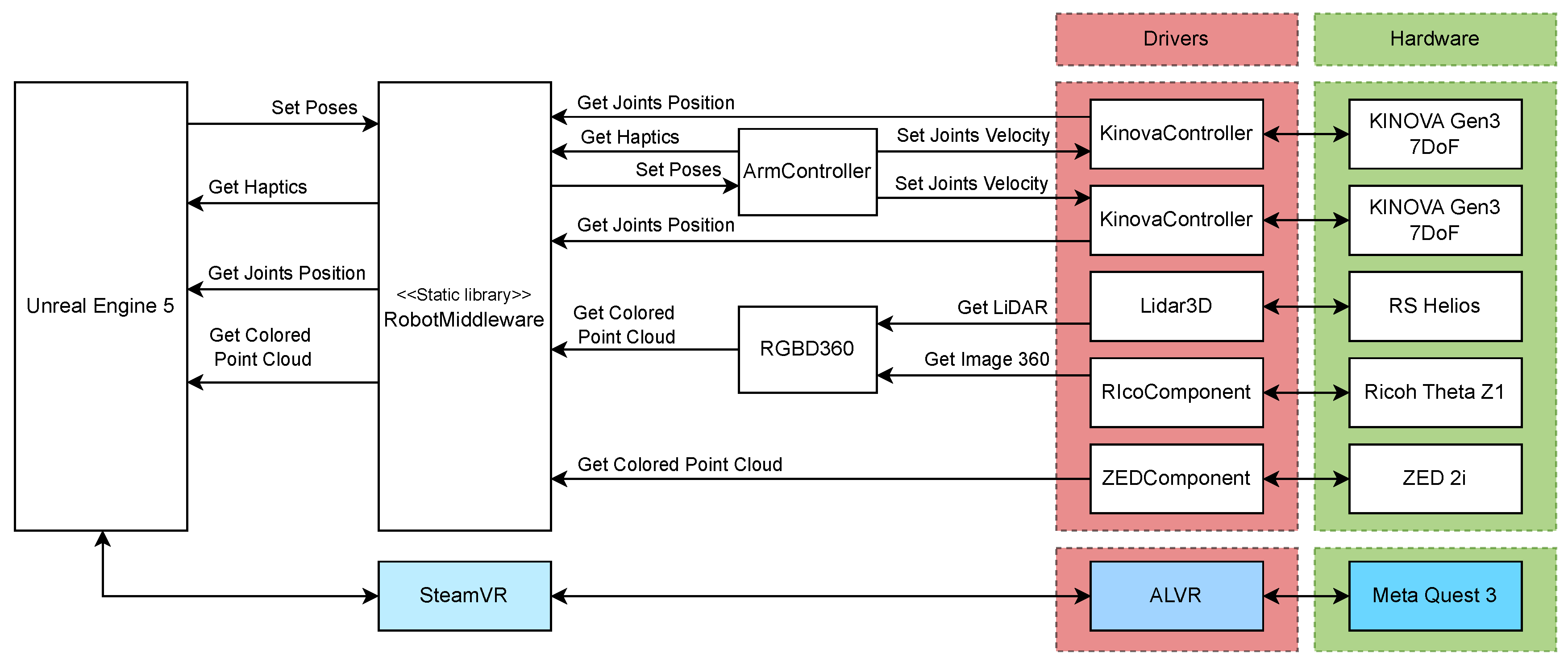

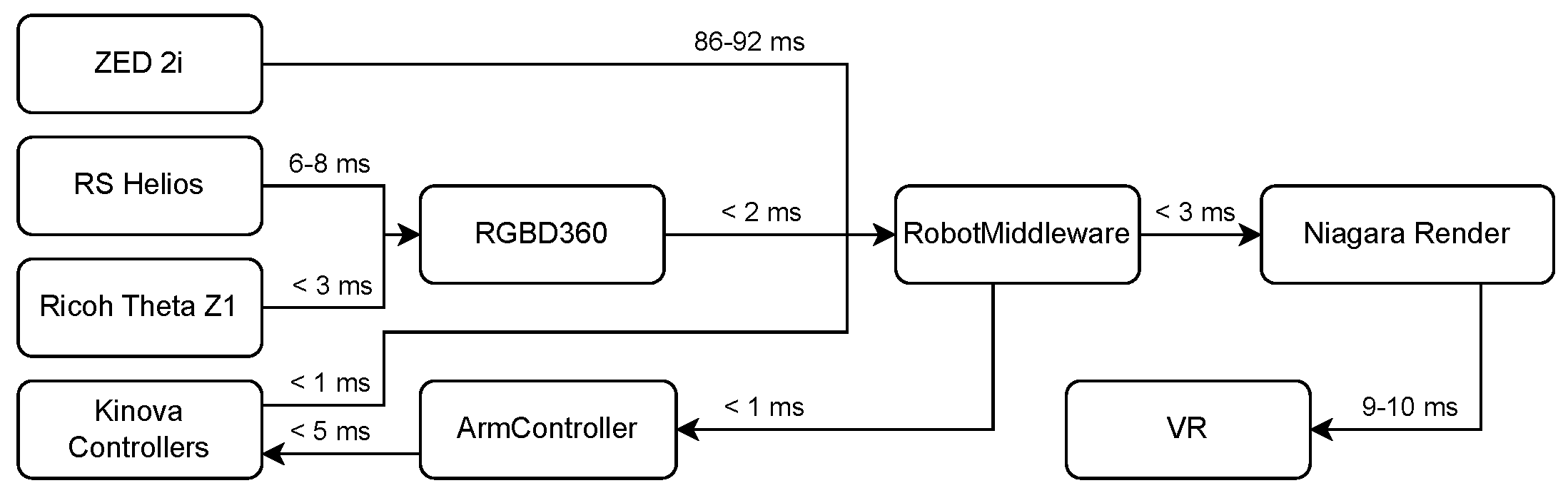

3.4. Communication Architecture and Middleware Abstraction

Figure 4 details the software/hardware stack and the main data flows of the proposed teleoperation system. The overall architecture is built upon the RoboComp robotics framework, which internally employs the Ice middleware; however, Unreal Engine 5.6.1 is kept independent from these back-end choices by communicating exclusively through

RobotMiddleware, a static C++ library that exposes a standardized API for command and sensing exchange. This abstraction layer can be re-targeted to alternative middleware (e.g., ROS 2) without modifying the UE application. UE acts as the XR front-end, receiving head/hand tracking and controller events through the SteamVR runtime, while the Meta Quest 3 is connected via ALVR.

On the control side, an ArmController module consumes target end-effector commands from UE and produces joint-level commands that are delivered to the robot through dedicated drivers; in particular, one KinovaController instance is used per manipulator to interface the two Kinova Gen3 7-DoF arms. On the perception side, sensor drivers provide the raw data streams used by the VR visualization pipeline: Lidar3D interfaces with the RS Helios LiDAR, RicoComponent interfaces with the Ricoh Theta camera, and ZEDComponent interfaces with the ZED 2i stereo camera. These sensing streams are queried by higher-level modules (e.g., the RGBD360 block) to obtain LiDAR scans and panoramic imagery (“Get LiDAR” / “Get Image 360”), enabling the colored point-cloud reconstruction that is rendered in UE.

3.5. Control Loop and Safety

Motion control is handled through the Robotics Toolbox by Peter Corke [

24]. Unreal Engine sends target controller poses (desired end-effector poses) to an ArmController module within the RobotMiddleware layer. This module computes the required joint velocities using an inverse kinematics solver and transmits the commands to the Kinova arms (or to the simulated arms when using Webots as backend).

A dead-man switch button located on the controller is required to enable motion commands, providing an operator-in-the-loop safety mechanism. In parallel, robot joint states are continuously read and fed back to UE to synchronize the virtual and physical models and to keep the operator’s view consistent with the active backend (simulation or real robot).

3.6. Perception Pipeline and Point-Cloud Rendering

Inside Unreal Engine, the remote workspace is represented as a large colored point cloud, enabling free viewpoint exploration without forcing the robot camera motion. The environment point cloud is obtained by fusing RS Helios LiDAR data with color information from the Ricoh camera and subsequently merging it with the point cloud provided by the ZED 2i camera. The resulting colored point cloud is rendered directly on the GPU through Unreal Engine’s Niagara system, enabling real-time visualization of more than 1,000,000 points while preserving interactive performance.

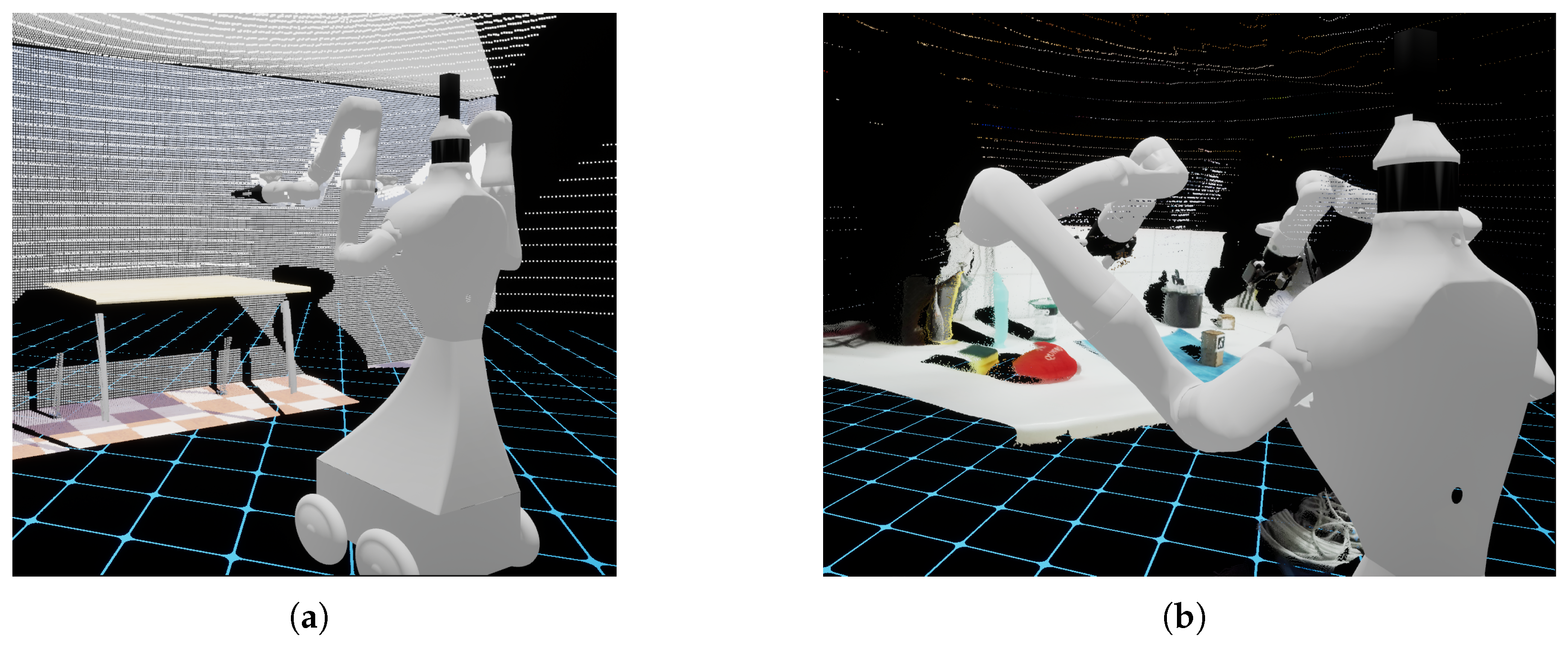

Figure 5 illustrates the resulting point-cloud visualization in Unreal Engine for both operation modes: a simulated scene in Webots and the corresponding real-world reconstruction. This comparison highlights that the same VR visualization pipeline and rendering strategy (Niagara-based GPU point sprites) is preserved across simulation and physical deployment, providing consistent 3D situational awareness to the operator.

3.7. Simulation-to-Real Operation

A central design goal of the proposed framework is to preserve the operator interaction paradigm across simulation and real deployment. The same UE VR interface (controller to end-effector mapping, visualization, and safety gating) is used with either Webots or the physical Pbot by switching the backend that receives joint velocity commands and provides state feedback. This sim-to-real consistency supports iterative development, safe testing, and user training in simulation before transferring the same workflows to the real robot.

4. Experimental Results

In this section, we present the experimental results from both technical performance evaluations and user studies. We divided our evaluation into two main areas: (1) a technical experiment involving system performance under various conditions using different point cloud sizes, ranging from 50K to 2M points and (2) a comparison of our VR-based teleoperation framework with existing solutions in terms of performance and usability.

4.1. Technical Experiment

To assess the performance of our VR framework, we measured system resource usage (CPU, GPU, RAM, and VRAM), frame rendering time, and frame rate (FPS). The tests were performed using an NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPU with 8GB of VRAM, a 1 Gbps communication network, and the MetaQuest 3 VR headset with a resolution of 2144x2240 per eye. The Niagara system was configured to 20Hz, with the UR limited to 90FPS. The tests were conducted with different point cloud sizes (50K, 500K, 1M, 1.5M, and 2M points) to assess the scalability and performance of the system in real-time rendering and interaction scenarios.

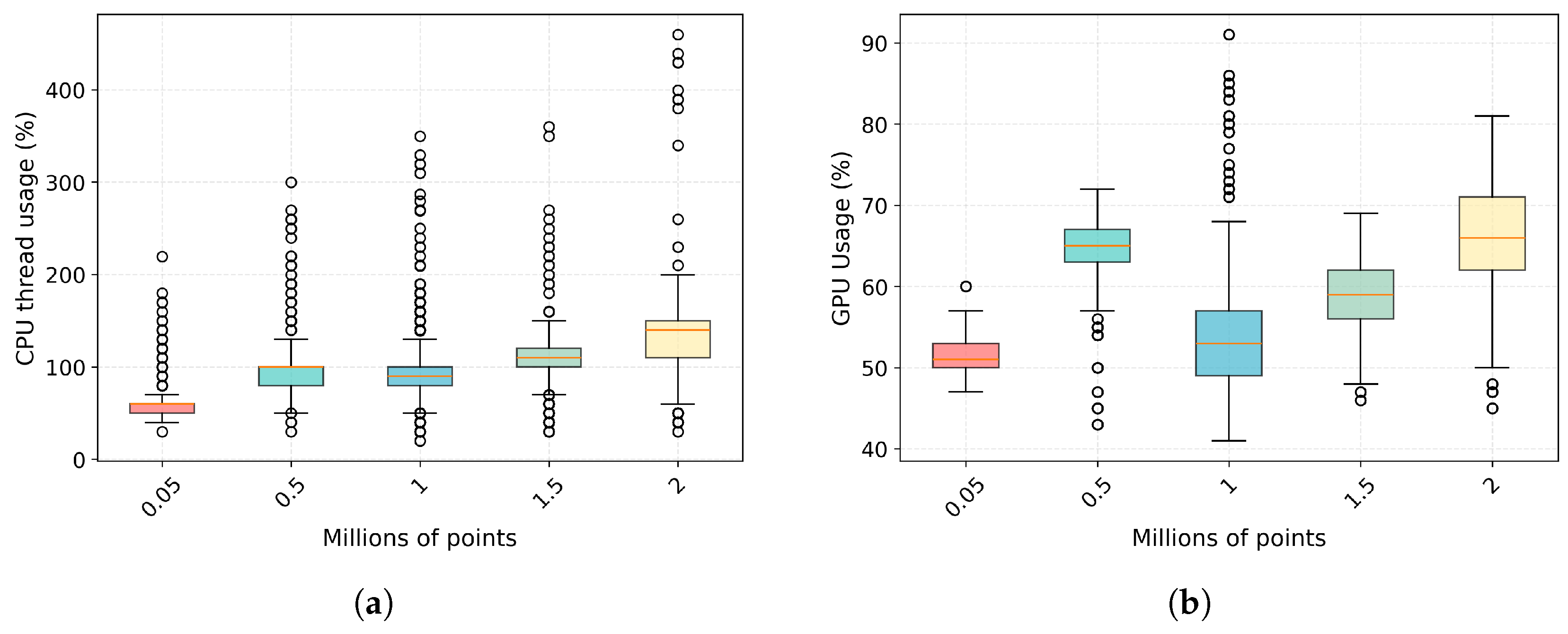

4.1.1. CPU and GPU Usage

Figure 6(a) presents the CPU usage statistics for different point cloud sizes. The average CPU usage increases as the number of points increases, with the highest usage recorded for the 2M point cloud. This demonstrates that the CPU usage increases as the point cloud density grows, with the system handling up to 2M points with a significant load.

The GPU usage, shown in

Figure 6(b), also increases as the number of points grows. However, the GPU is less stressed compared to the CPU, with utilization peaking at 81% for the 2M point cloud. The GPU handles the rendering load efficiently, with a manageable increase in utilization as the point cloud size increases.

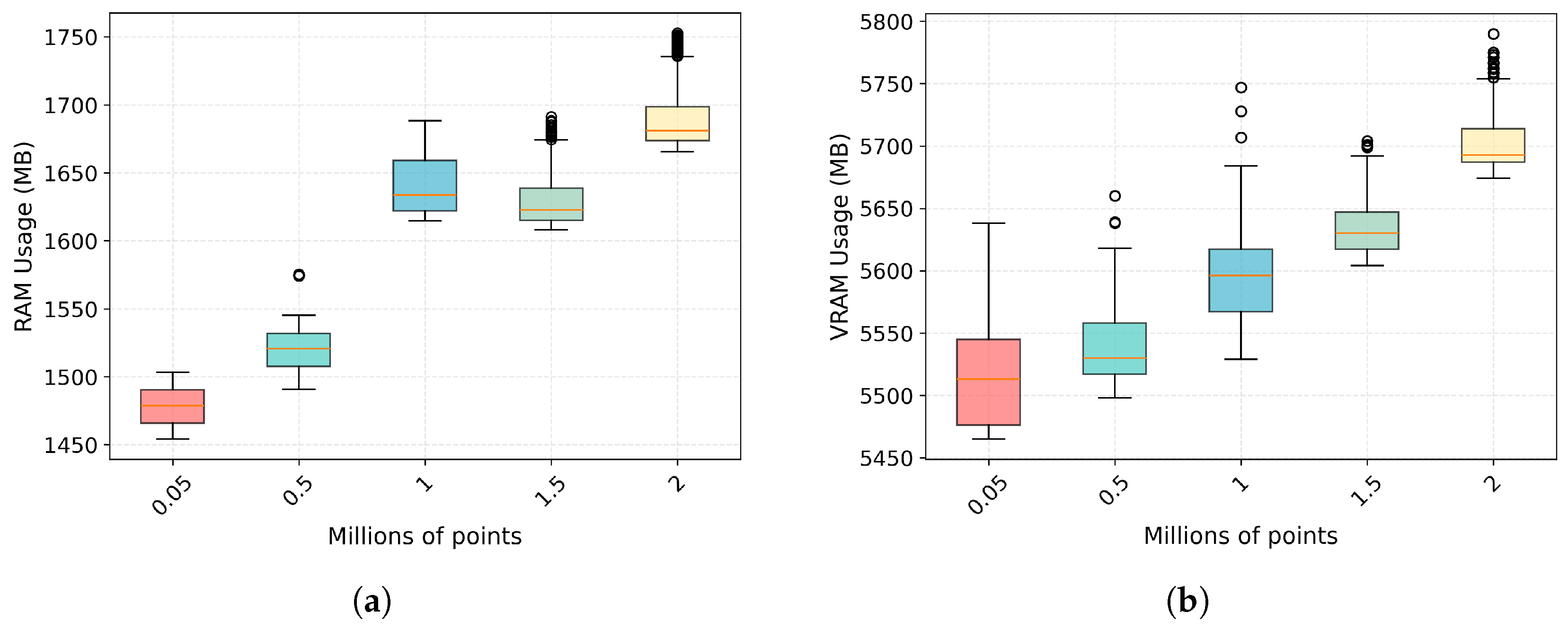

4.1.2. Memory Usage (RAM and VRAM)

Figure 7(a) and

Figure 7(b) show the memory usage for RAM and VRAM, respectively. As expected, the RAM and VRAM usage increases with larger point clouds.

This shows that the memory consumption increases with the number of points, with VRAM usage being a critical factor at higher point cloud sizes.

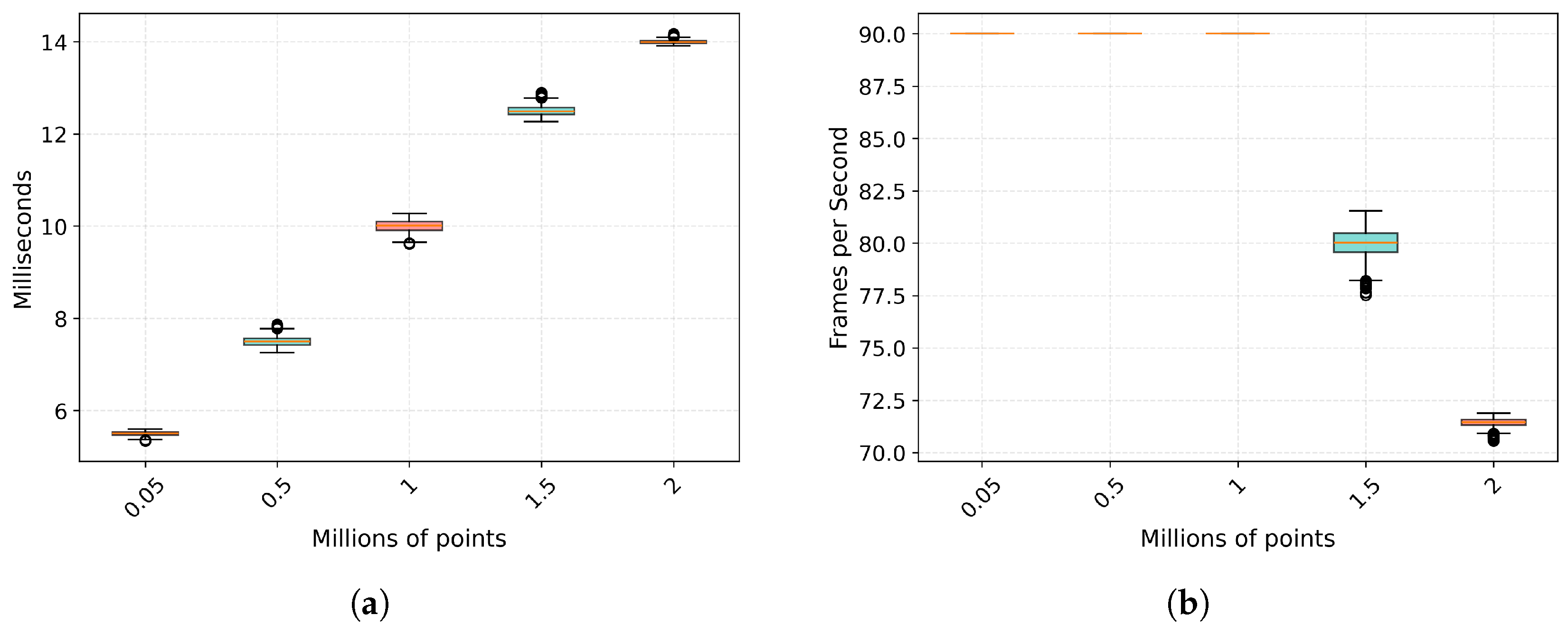

4.1.3. Latency and FPS

The frame rendering time (or frame period) and frame rate (FPS) metrics are crucial for evaluating the responsiveness of the VR environment. As shown in

Figure 8(a), the rendering period increases as the point cloud size grows, resulting in higher latency. For FPS,

Figure 8(b) shows that the system maintains a stable 90 FPS for point clouds up to 1M points. However, for larger point clouds, the FPS decreases.

The system starts to experience a slight drop in FPS with point clouds exceeding 1M points, but it still maintains a smooth user experience, with FPS remaining above 70 even for the heaviest point cloud tested. This stability helps mitigate one of the common issues in VR: motion sickness.

4.1.4. System Latency

Figure 9 illustrates the end-to-end latency breakdown of the proposed system. Each processing component is represented as a block, while arrows indicate the corresponding processing and communication delays between system modules.

The ZED stereo camera exhibits a total latency in the range of 86–92 ms, of which only approximately 7 ms correspond to onboard image processing. The remaining delay is primarily dominated by data transmission and synchronization over the network. At an operating frequency of 20 Hz, each frame carries approximately 64.8 Mbits, meaning that network bandwidth becomes a critical factor in the overall system latency. As a result, increasing the available network throughput could significantly reduce this component of the delay.

The impact of point cloud size on communication latency is further quantified in

Table 3. As shown, communication latency scales almost linearly with the number of transmitted points, ranging from 14-17 ms for 50K points (3.6 Mbits) up to 187-193 ms for 2M points (144 Mbits) on a 1 Gbps network. These results highlight the trade-off between visual fidelity and transmission latency, reinforcing the importance of balancing point cloud resolution with real-time performance requirements.

The LiDAR sensor introduces a latency of 6-8 ms, while the Ricoh camera contributes less than 3 ms. These sensor streams are fused within the RGBD360 module, which adds less than 2 ms of processing latency before forwarding the aggregated data to the middleware.

Regarding actuation, the Kinova manipulators exhibit a state transmission latency below 1 ms, while the reception and execution latency at the controller level is approximately 5 ms through the middleware interface. On the visualization side, data preprocessing for point cloud rendering in the Niagara pipeline requires less than 3 ms, while the VR rendering stage operates within 9–10 ms per frame. This rendering latency is consistent with the frame times reported in the technical evaluation in

Section 4.1.3.

Overall, although individual sensors, particularly the stereo camera, introduce non-negligible delays due to high data throughput requirements, the remaining components of the pipeline exhibit low and predictable latencies. The cumulative system latency remains within the bounds required for real-time VR teleoperation, enabling responsive interaction, stable visual feedback, and effective closed-loop control.

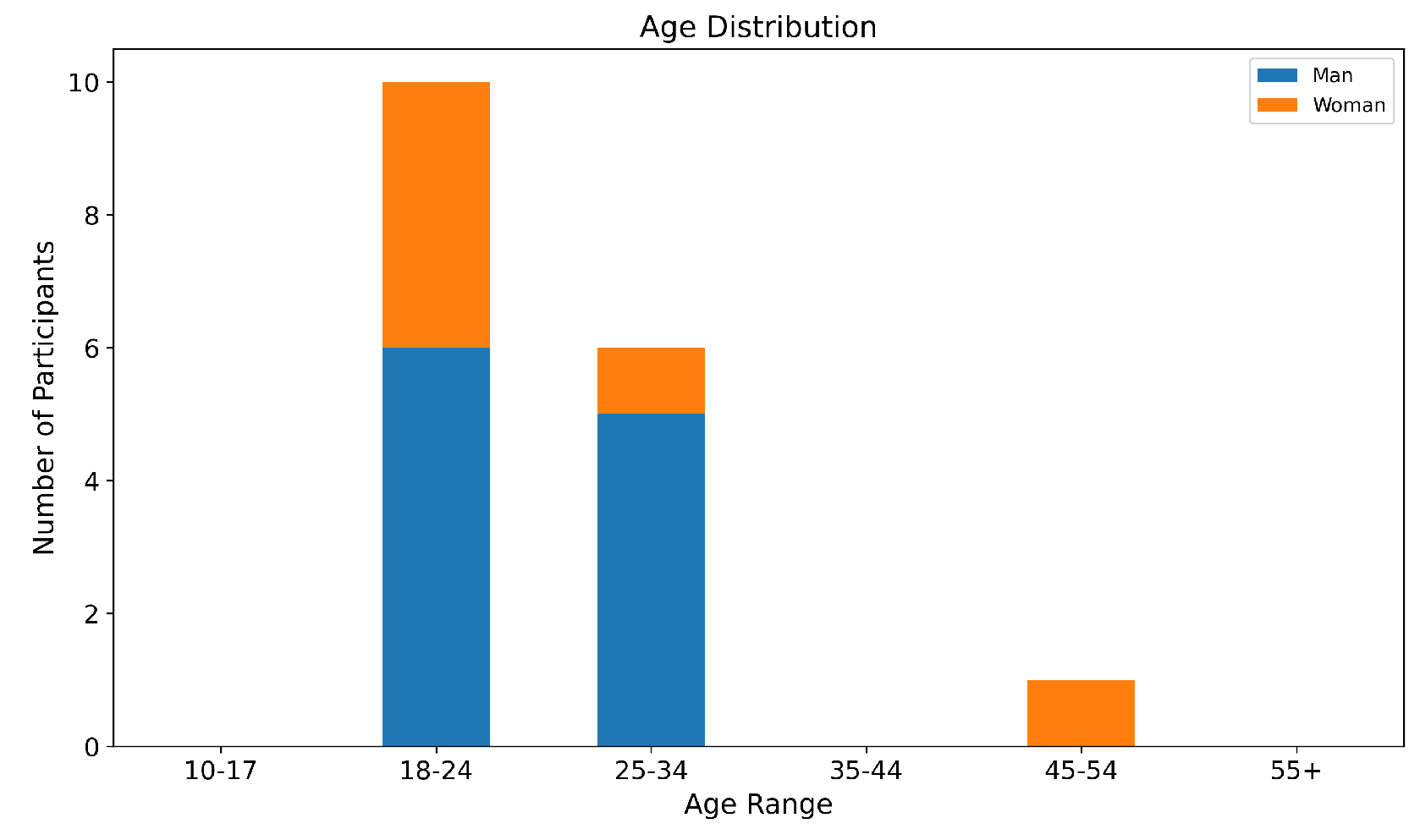

4.2. Real-World Tests: Teleoperation Evaluation

We conducted seven tests with 17 participants, consisting of 7 participants with experience in VR gaming and 10 without. The age and sex distribution of the participants is shown in

Figure 10. The goal was to evaluate the usability and ease of control of our VR teleoperation system. The 17 participants performed 6 tasks

1, in the same order and sequentially.

Prior to the tests, participants were given a self-paced adaptation period to familiarize themselves with the system, which did not exceed 300 seconds.

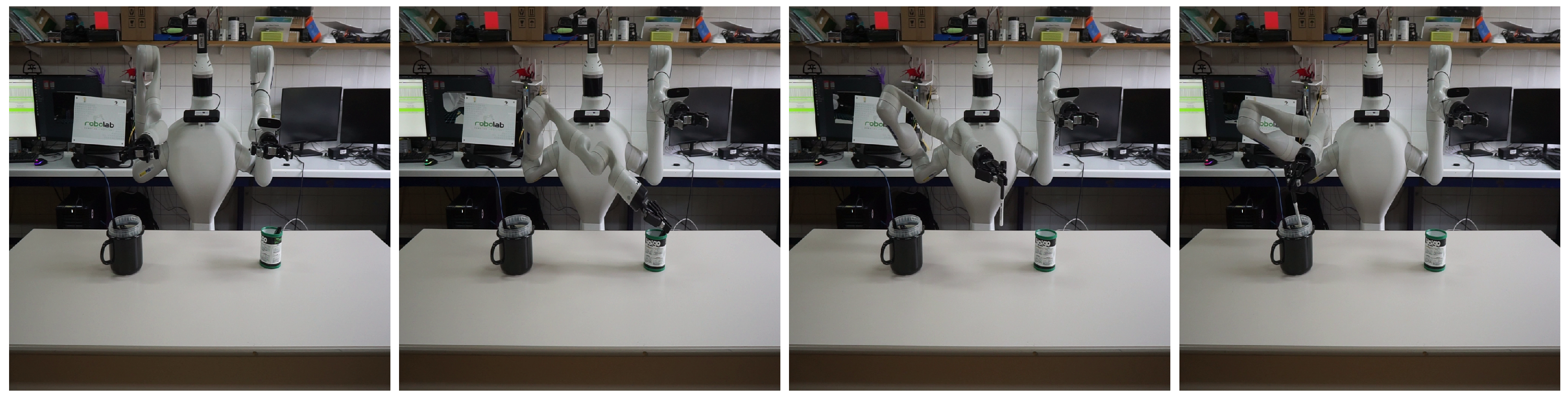

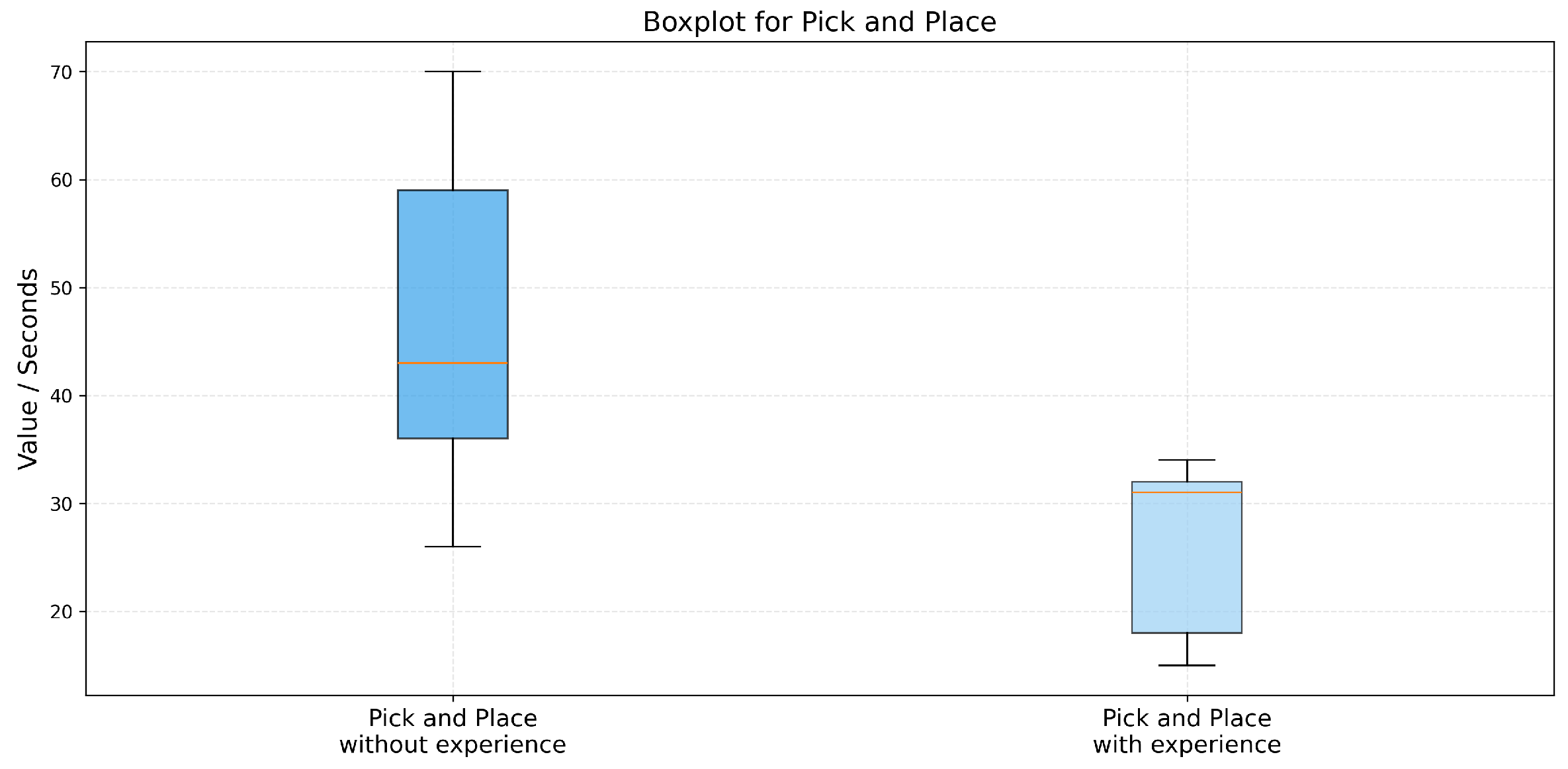

4.2.1. Pick and Place

In this task, participants were required to grasp a pencil and move it from one cup to another, as illustrated in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 12,, participants with prior VR experience achieved a lower mean completion time and exhibited a more compact distribution compared to participants without VR experience. This suggests that familiarity with VR environments positively influences early task performance, particularly for simple grasping and placement actions.

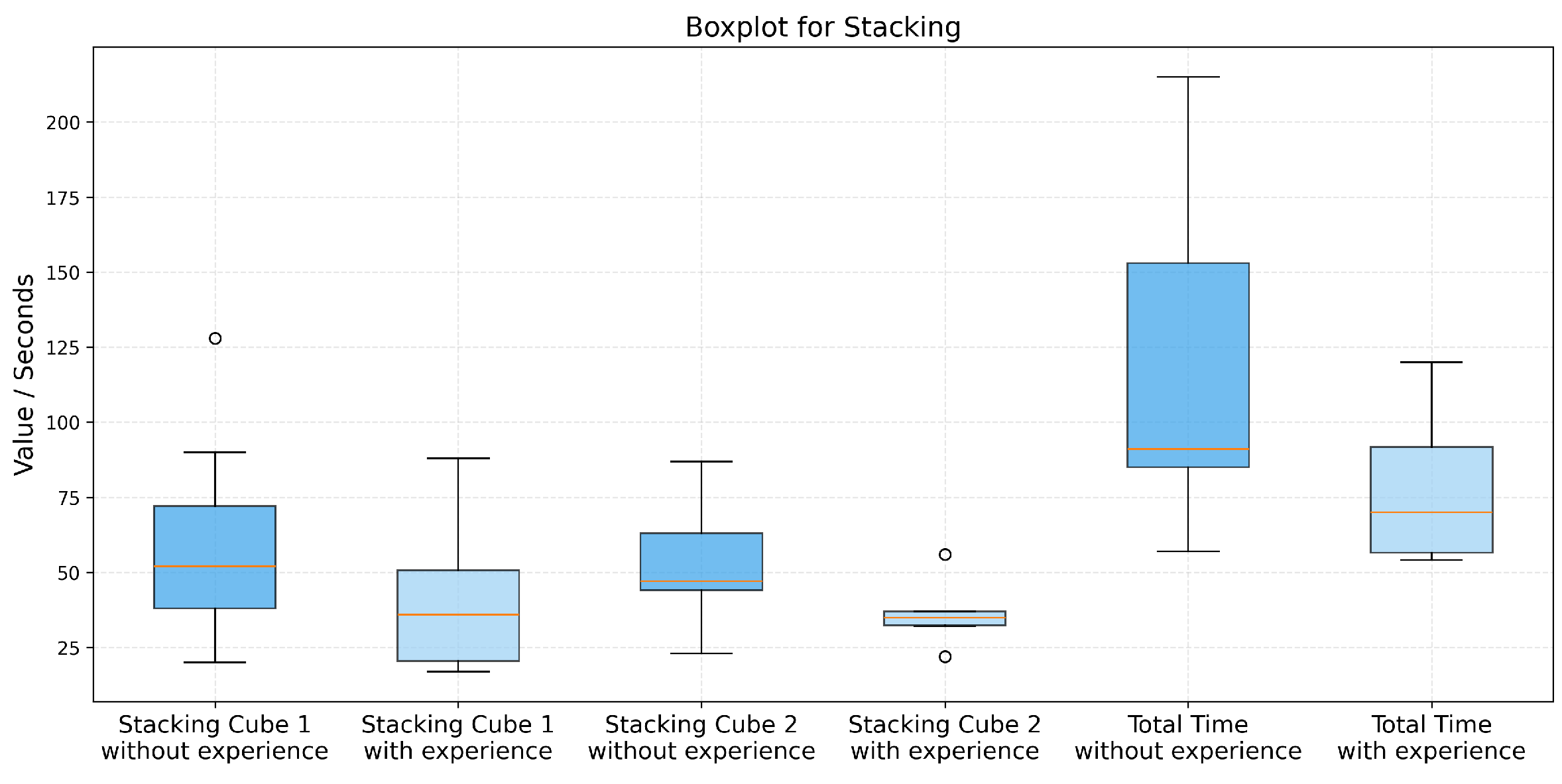

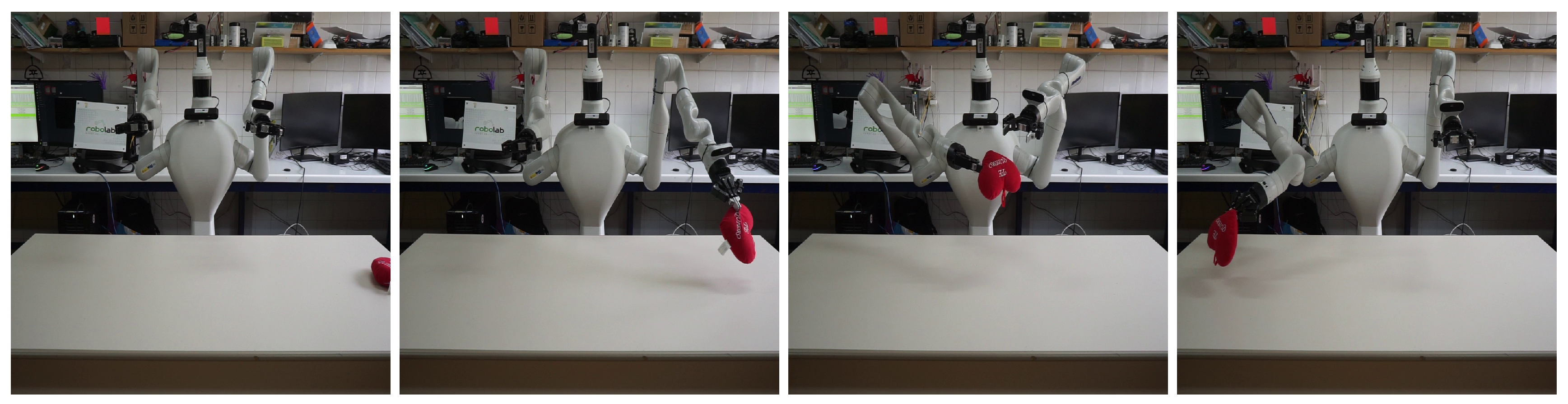

4.2.2. Stacking Cubes

In this task, participants were asked to build a tower using three cubes, as illustrated in

Figure 13.

As shown in

Figure 14, participants without VR experience slight reduction the relatively dispersion and mean across both stacking actions. In contrast, participants with VR experience preserved a similar mean time between both actions but showed a notable reduction in dispersion during the second stacking step. This indicates improved consistency as users adapted to the bimanual manipulation required by the task.

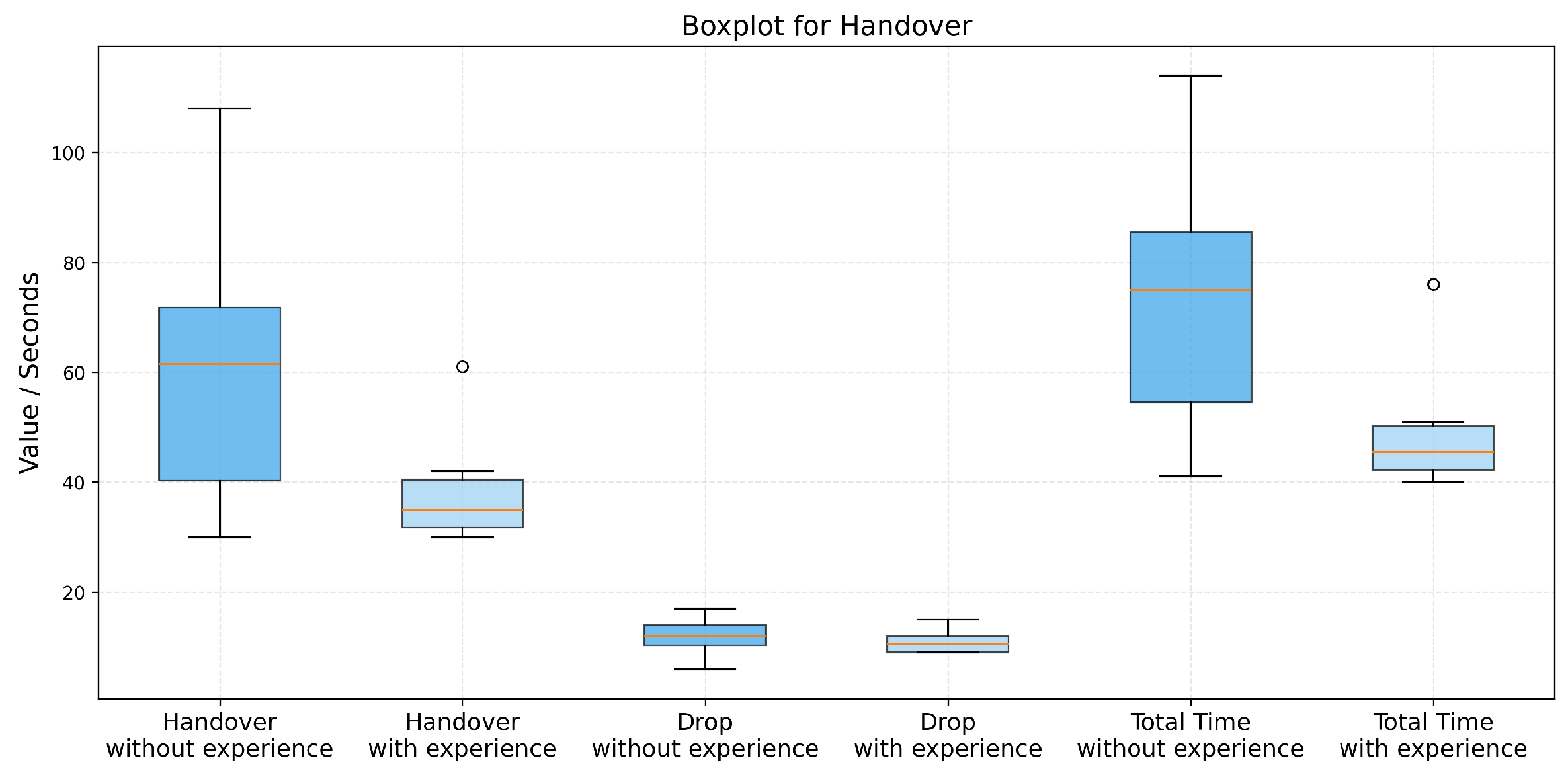

4.2.3. Toy Handover

In this task, participants were required to pick up a toy with one manipulator, transfer it to the other manipulator, and place it in a designated location, as illustrated in

Figure 15.

As shown in

Figure 16, participants with VR experience achieved significantly lower mean completion times and reduced dispersion compared to those without VR experience, particularly during the handover phase. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups when placing the toy on the right side of the table, suggesting that the drop action posed minimal difficulty regardless of prior VR familiarity.

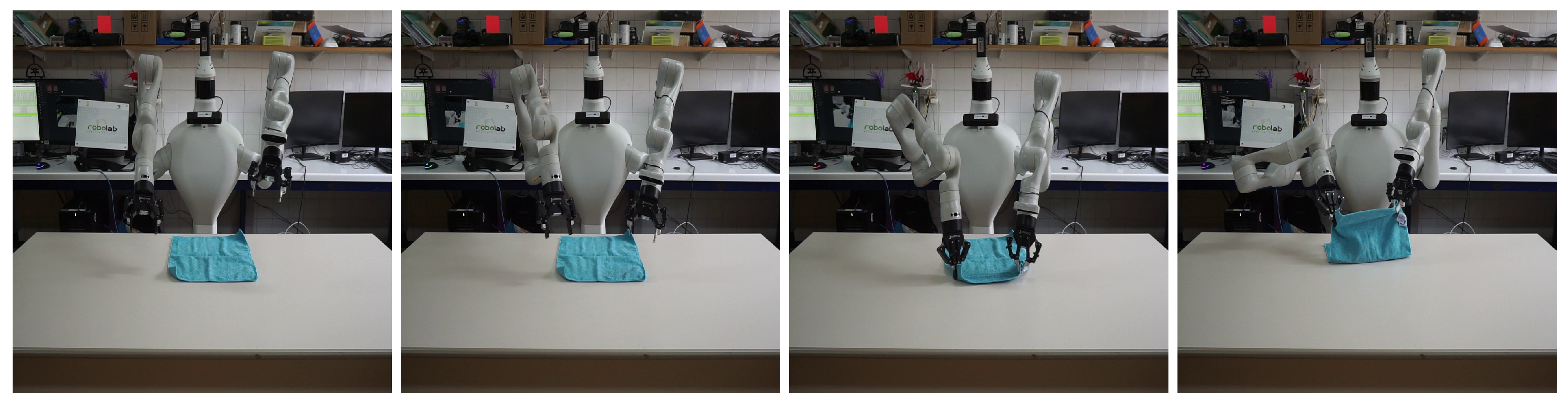

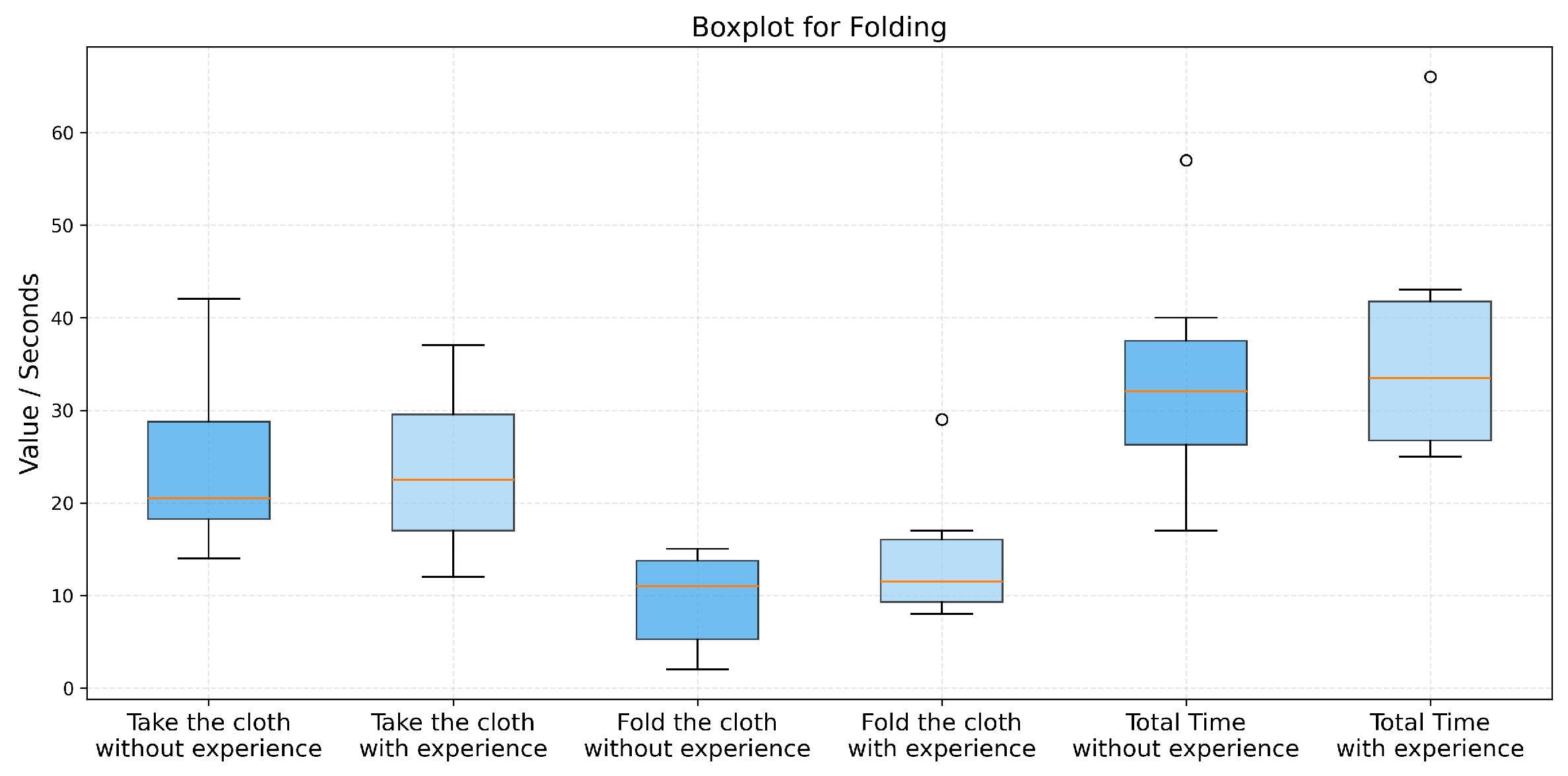

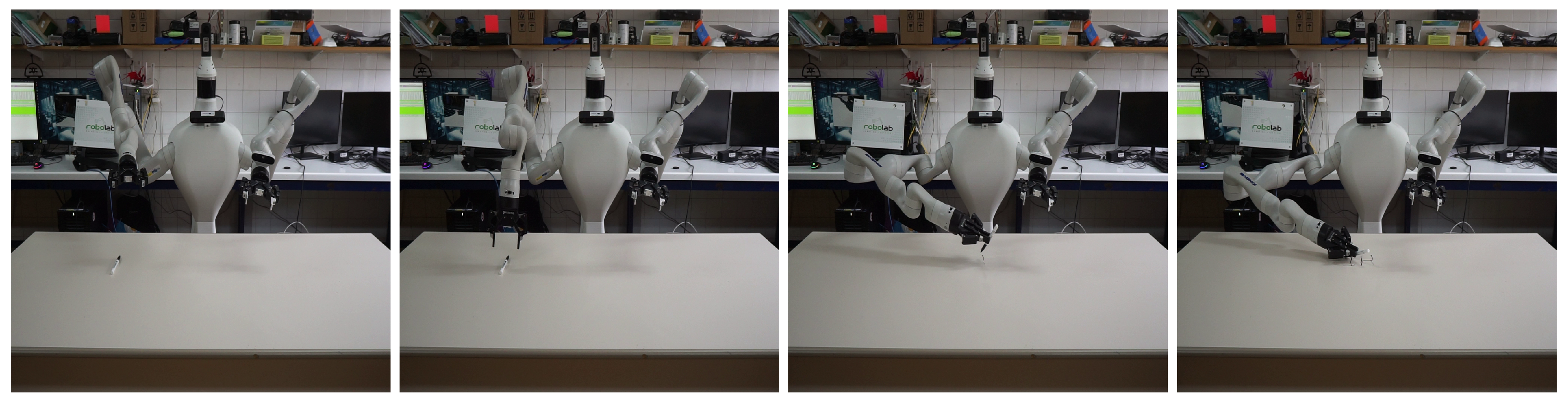

4.2.4. Folding Cloth

In this task, participants were required to fold a piece of cloth by moving both arms synchronously, as illustrated in

Figure 17.

As shown in

Figure 18, completion times were similar for both participant groups. This outcome may be attributed to the inherently bimanual and synchronized nature of the task, which requires coordinated motion of both robotic arms and limits the advantage typically provided by prior VR experience.

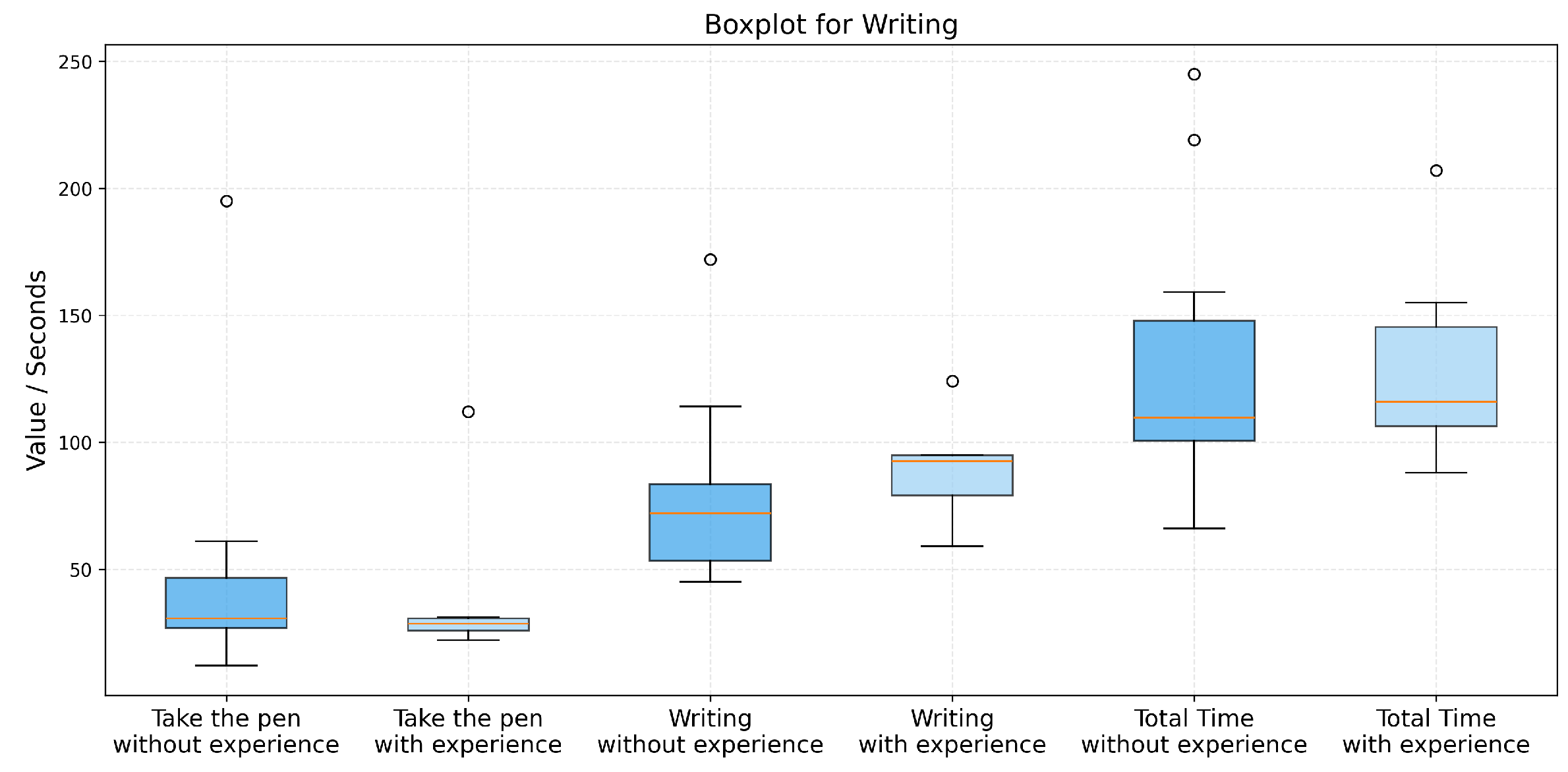

4.2.5. Writing “HI”

In this task, participants were required to grasp a pen and write “HI” on the table surface, as illustrated in

Figure 19.

As shown in

Figure 20, participants with VR experience demonstrated a more concentrated distribution when grasping the pen. However, during the writing phase, this group exhibited a slightly higher mean completion time compared to participants without VR experience. As a result, the overall task completion times for both groups were comparable. This may indicate that fine motor control during precise writing movements is influenced more by task-specific adaptation than by general VR familiarity.

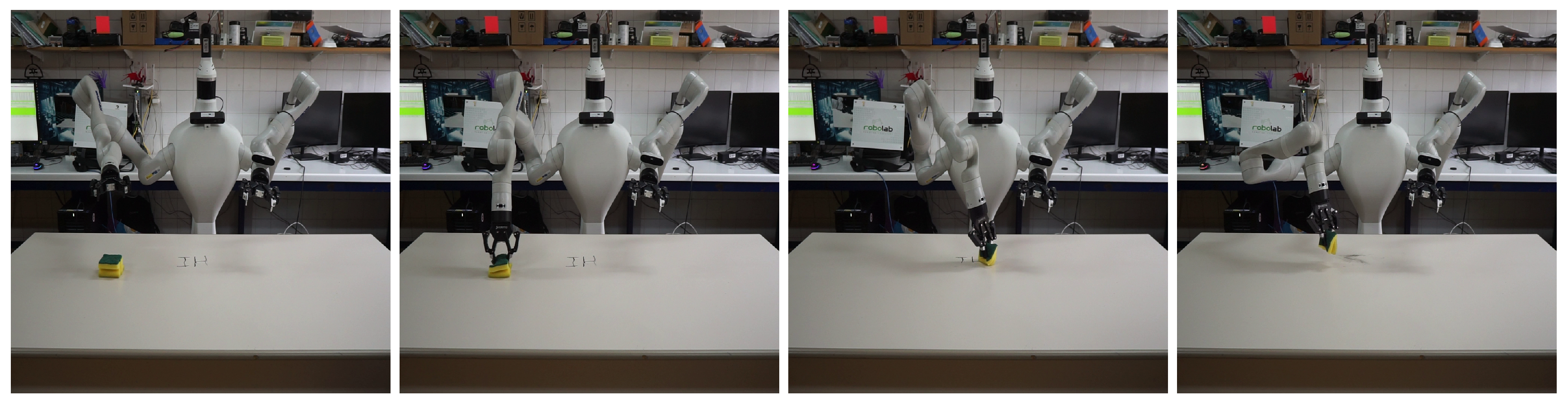

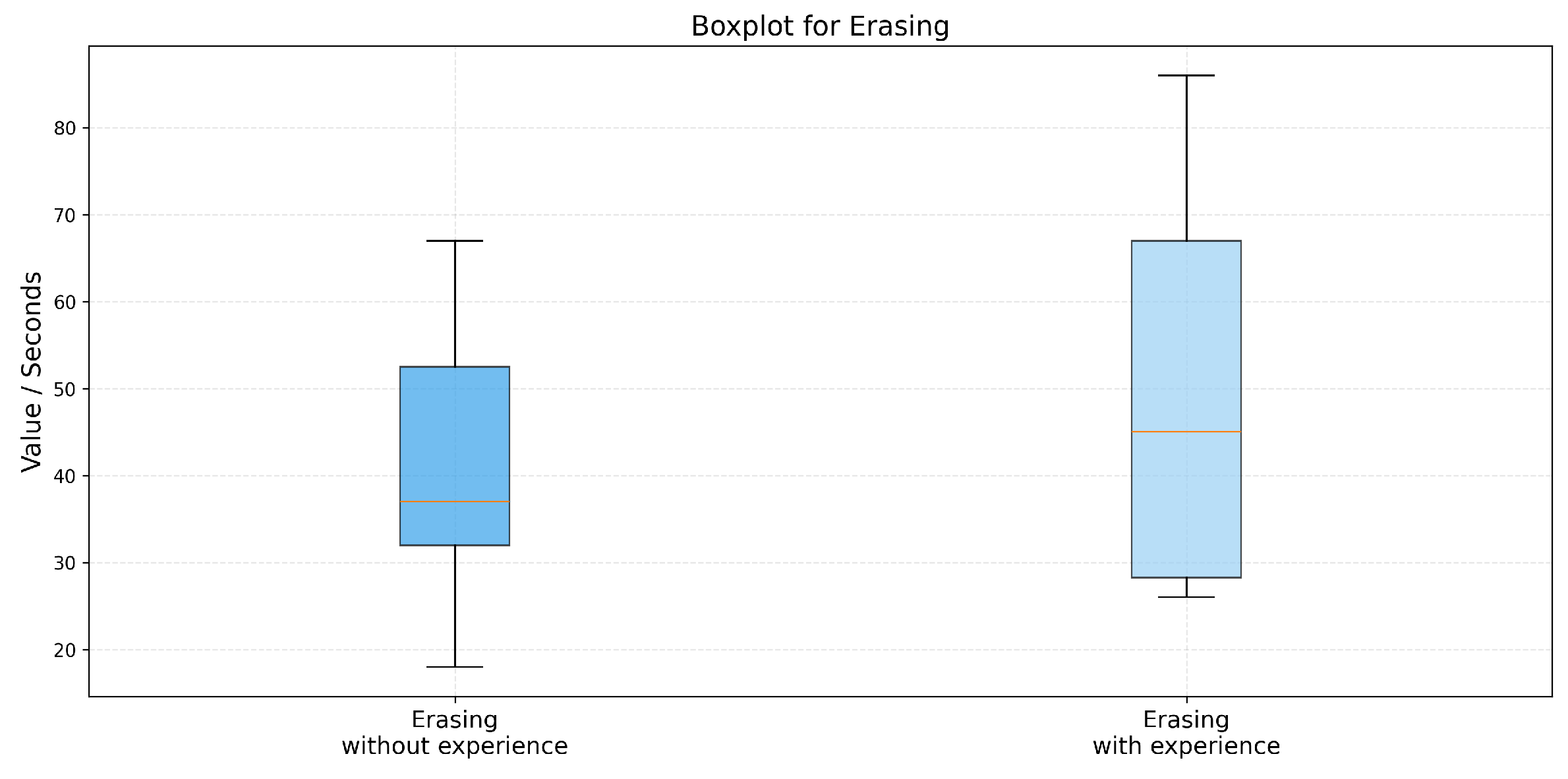

4.2.6. Erasing “HI”

In this task, participants were required to erase the written “HI” from the table using a sponge, as illustrated in

Figure 21.

As shown in

Figure 22, participants without prior VR experience unexpectedly achieved lower completion times than those with VR experience. This result may be explained by the simplicity and repetitive nature of the erasing action, which relies less on spatial awareness and more on continuous motion, thereby reducing the impact of prior VR exposure.

4.2.7. Summary Success Rate

In terms of task completion, all participants, particularly those with VR experience, completed the tasks with high success rates, especially in tasks involving simpler interactions, such as Toy Handover (96.41% success rate). On the other hand, tasks that required more precise and coordinated actions, such as Pick and Place (76.47%) and Cube Stacking (76.47%), showed slightly lower success rates, with some collisions occurring between the manipulators and the environment. This may be attributed to the fact that these were among the first tasks performed, and participants were still adjusting to the VR environment and system controls.

Table 4.

Task success rates and collision metrics.

Table 4.

Task success rates and collision metrics.

| Task |

Success Rate (%) |

Self-Collision Count |

Environment Collision Count |

Timeout |

| Pick and Place (Pencil) |

76.47 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

| Cube Stacking |

76.47 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| Toy Handover |

96.41 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Cloth Folding |

88.24 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| Writing |

82.35 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| Erasing |

100.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

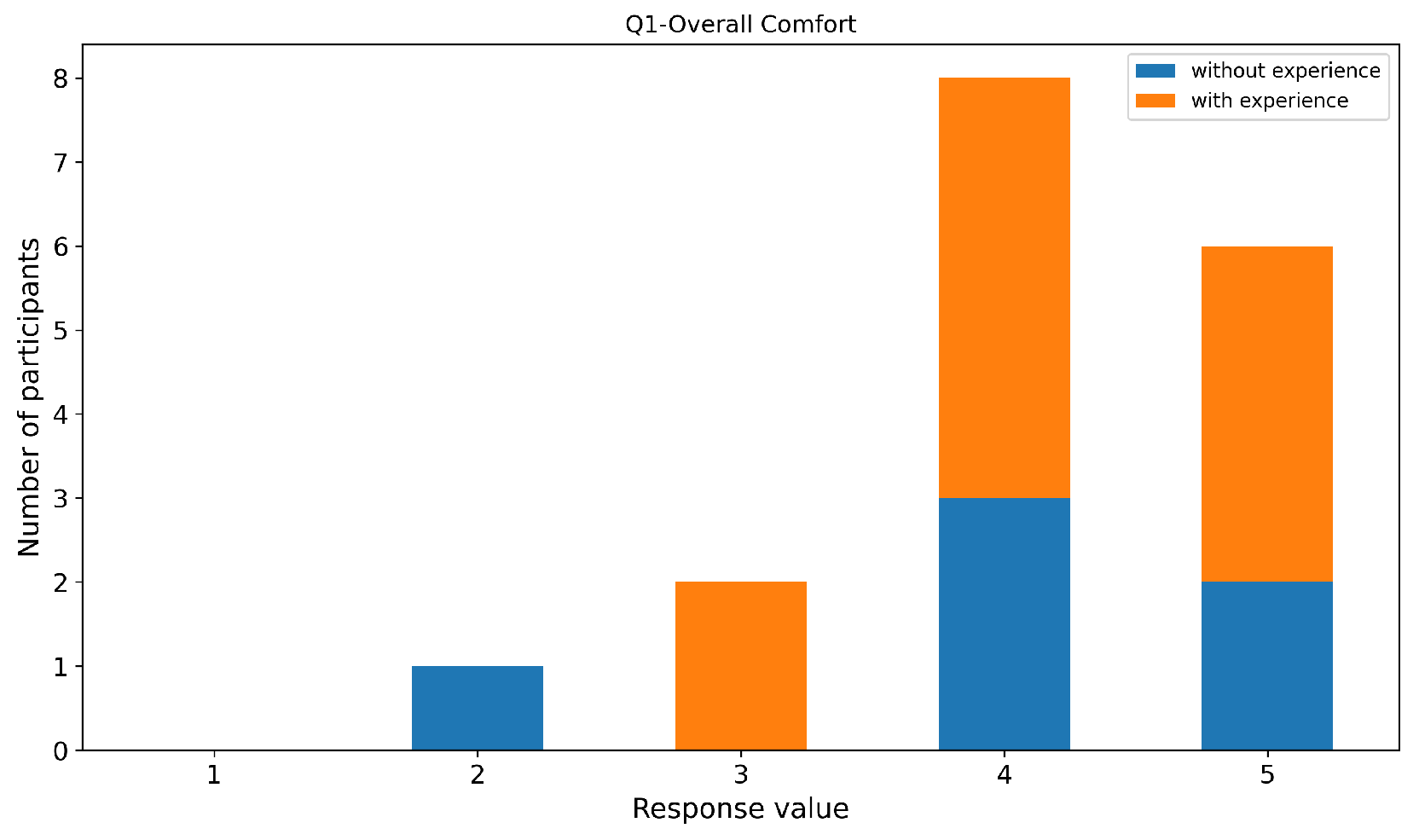

4.2.8. Post-Test User Feedback

A post-experiment subjective questionnaire was administered to assess user experience, usability, and perceived performance of the VR teleoperation system. Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale, where higher values indicate stronger agreement and lower values indicate stronger disagreement

-

The overall experience was comfortable in terms of hardware fit, weight, cables, and controllers.

Overall comfort received consistently high ratings (

Figure 23), with most participants scoring between 4 and 5. This indicates that the hardware setup (headset fit, weight, controllers, and cables) was well tolerated during the experiments.

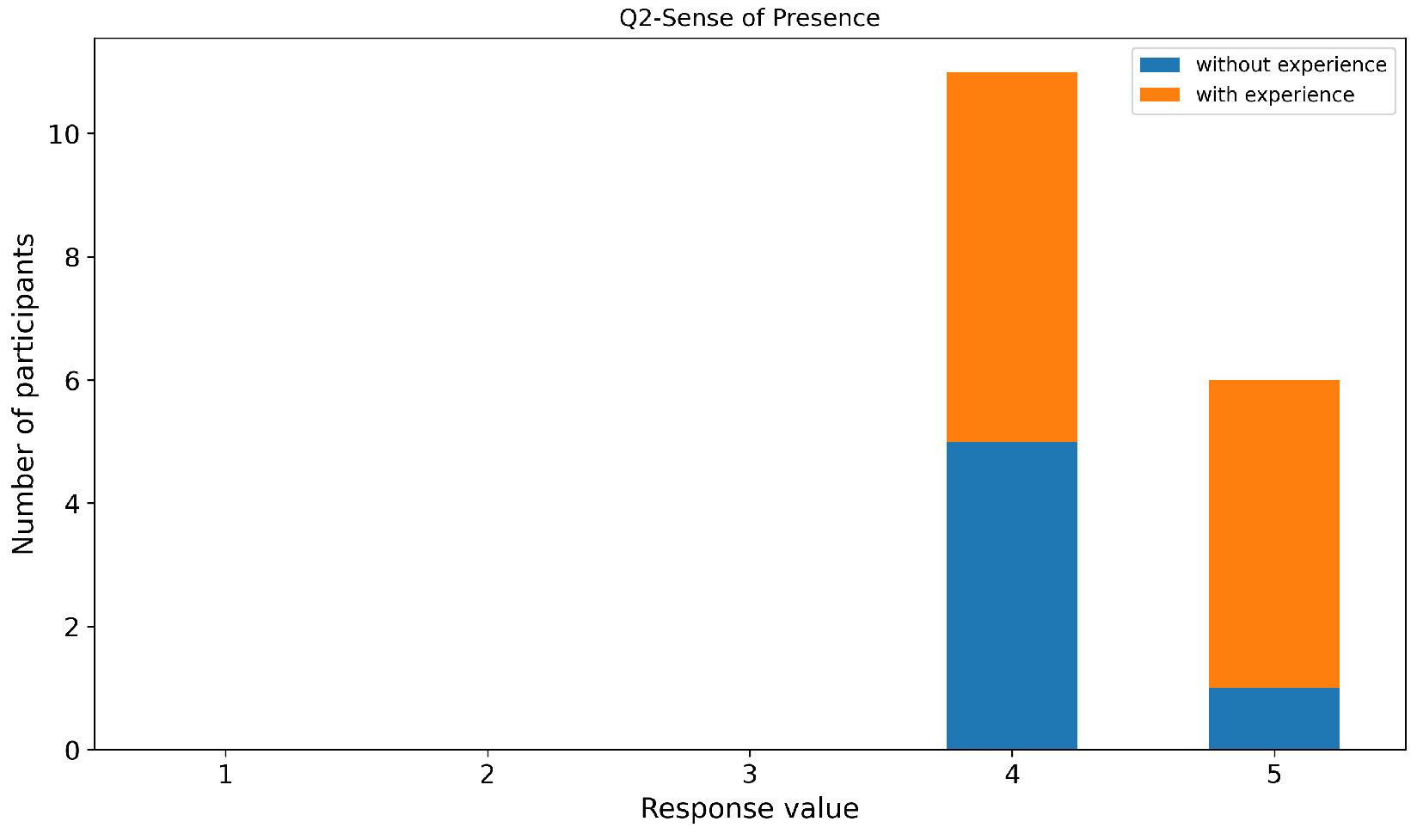

-

I felt a strong sense of presence, as if I were present in the robot’s environment or controlling the robot through its perspective.

Similarly to pervious question, the sense of presence was rated positively (

Figure 24), with the majority of participants reporting a strong feeling of being present in the robot’s environment or controlling the robot through its perspective. These results suggest that the immersive visualization and motion mapping effectively support embodiment in the teleoperation task.

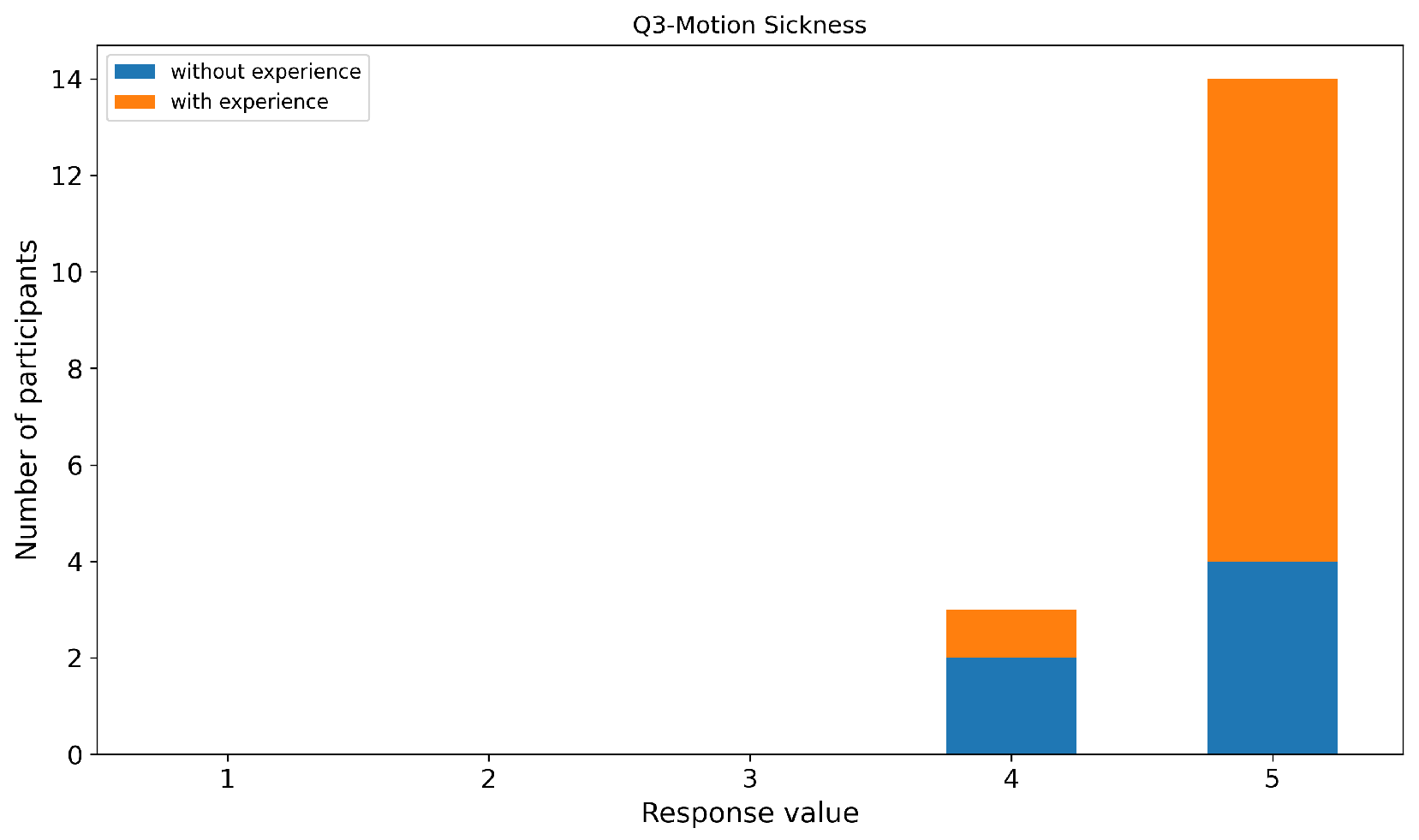

-

I did not experience symptoms of motion sickness (e.g., dizziness, nausea, or headache) during or after the experiment.

The system demonstrated very good tolerance in terms of motion sickness. As shown in

Figure 25, the vast majority of participants reported no symptoms at all, selecting the maximum score on the scale. Only three participants indicated mild discomfort, while no moderate or severe motion sickness symptoms were reported.

-

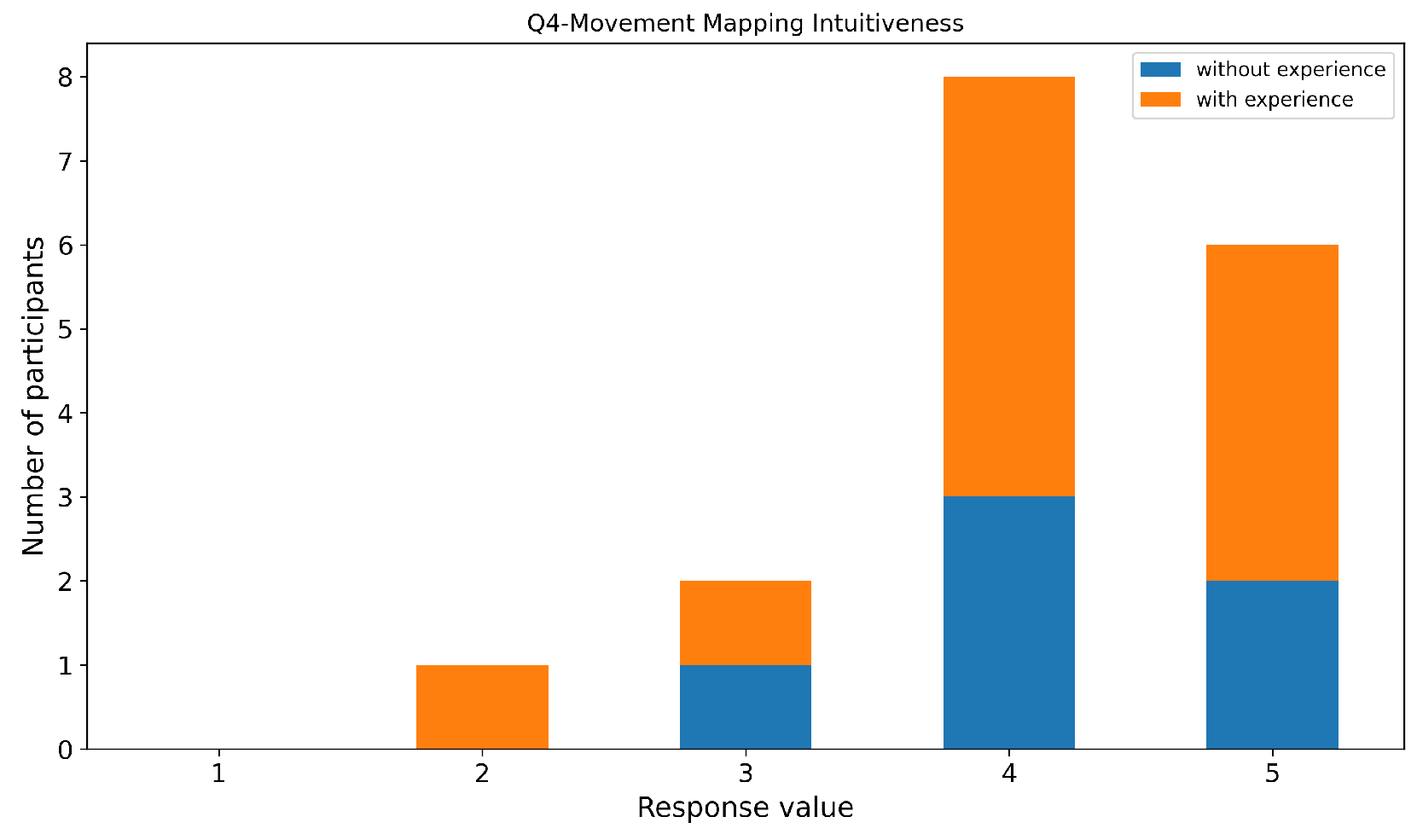

The mapping between my manual movements in VR and the movements of the robotic manipulator was intuitive.

The intuitiveness of the mapping between user hand movements and robotic manipulator motions was rated highly, with most participants scoring 4 or 5 (

Figure 26). This suggests that the control scheme was easy to understand and required minimal cognitive effort.

-

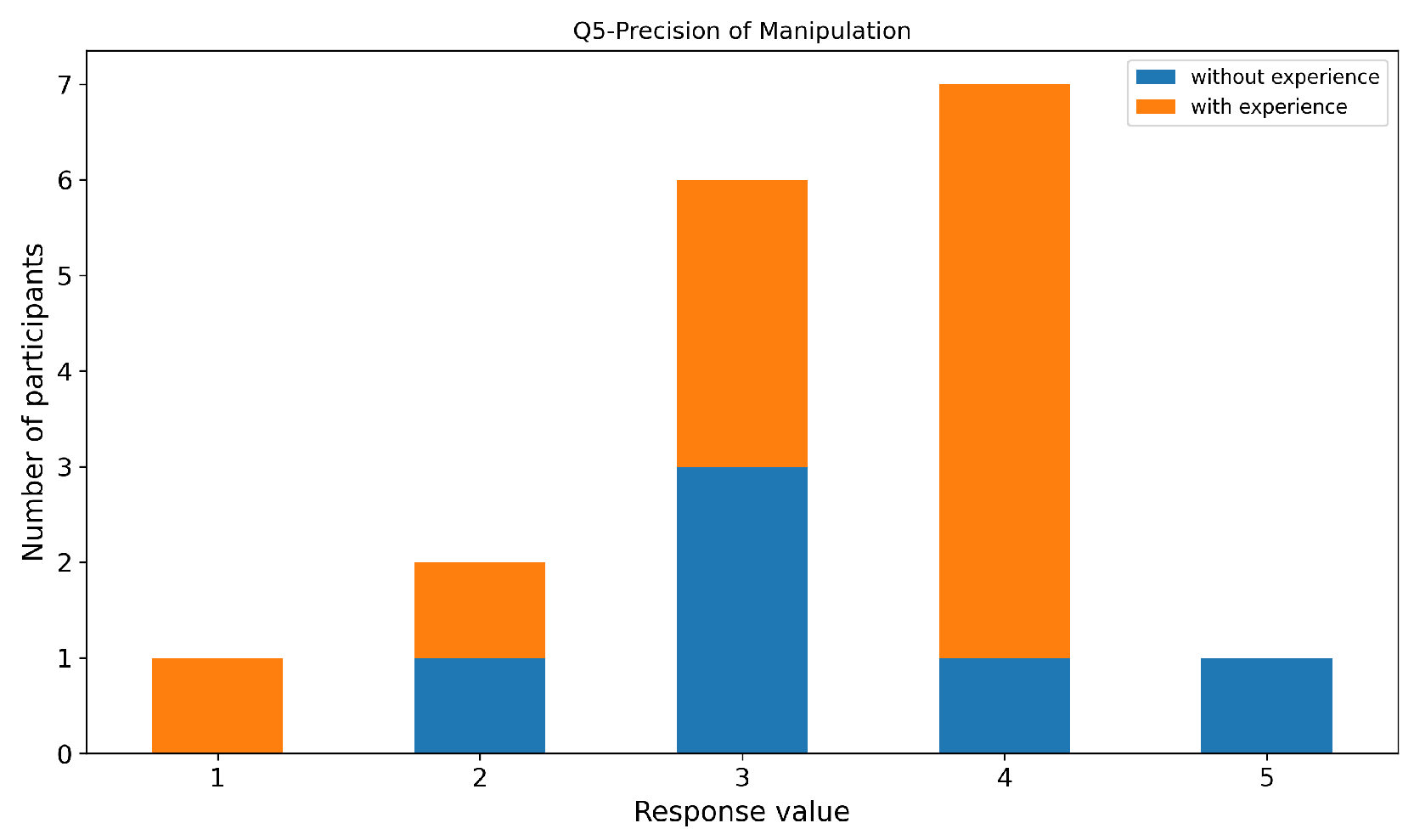

I was able to perform precise movements (e.g., picking up small objects or inserting them) with the accuracy I desired.

Perceived precision of manipulation received slightly more varied responses (

Figure 27). While many users felt capable of performing precise actions, some participants—particularly those without prior VR experience—reported moderate difficulty. This indicates that fine manipulation tasks may require additional adaptation time or enhanced visual feedback.

-

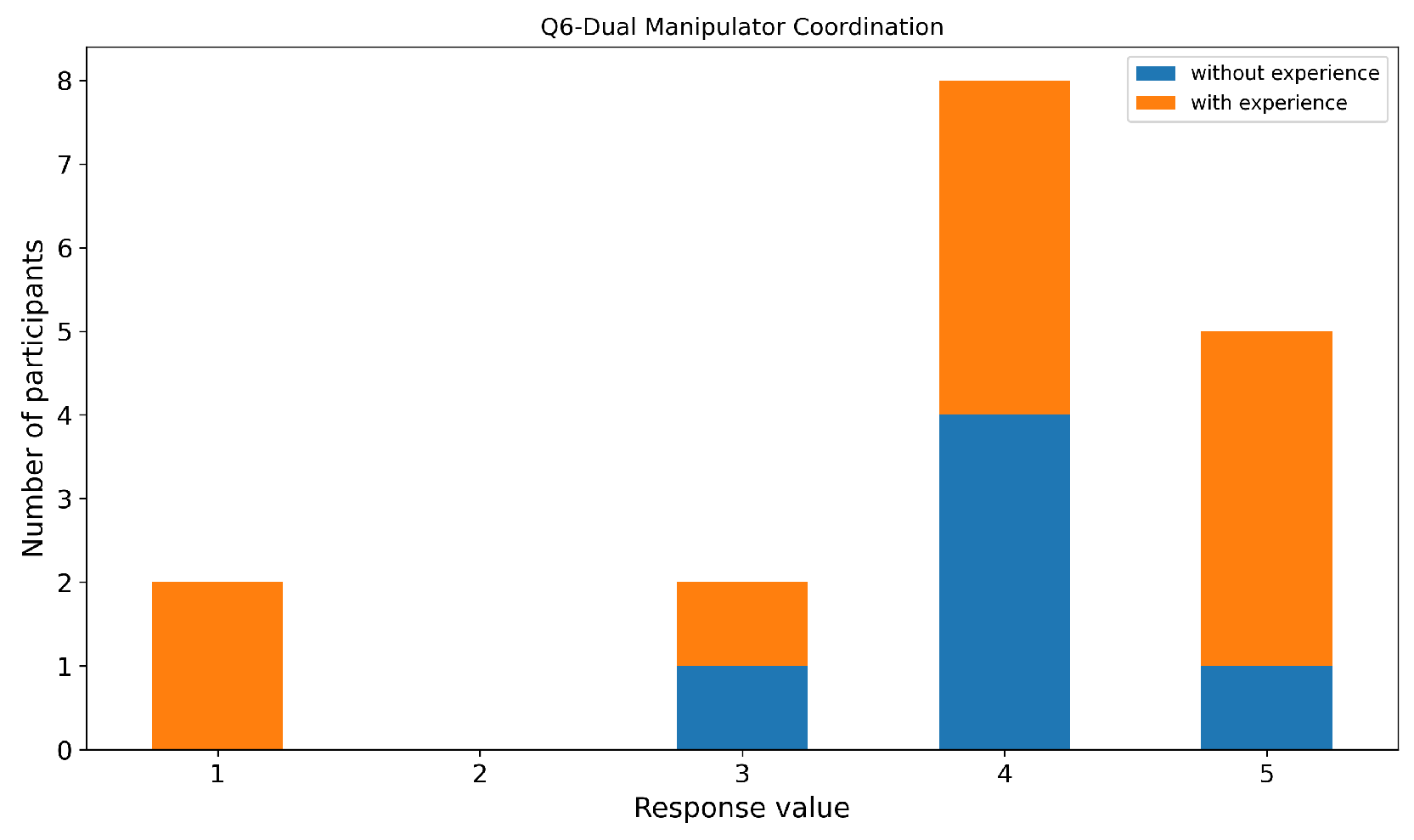

Coordinating the two manipulators simultaneously to perform the task was easy.

Coordination of the two manipulators simultaneously was identified as one of the more challenging aspects of the system. Although several participants rated this capability positively (

Figure 28), a noticeable portion reported moderate difficulty.

-

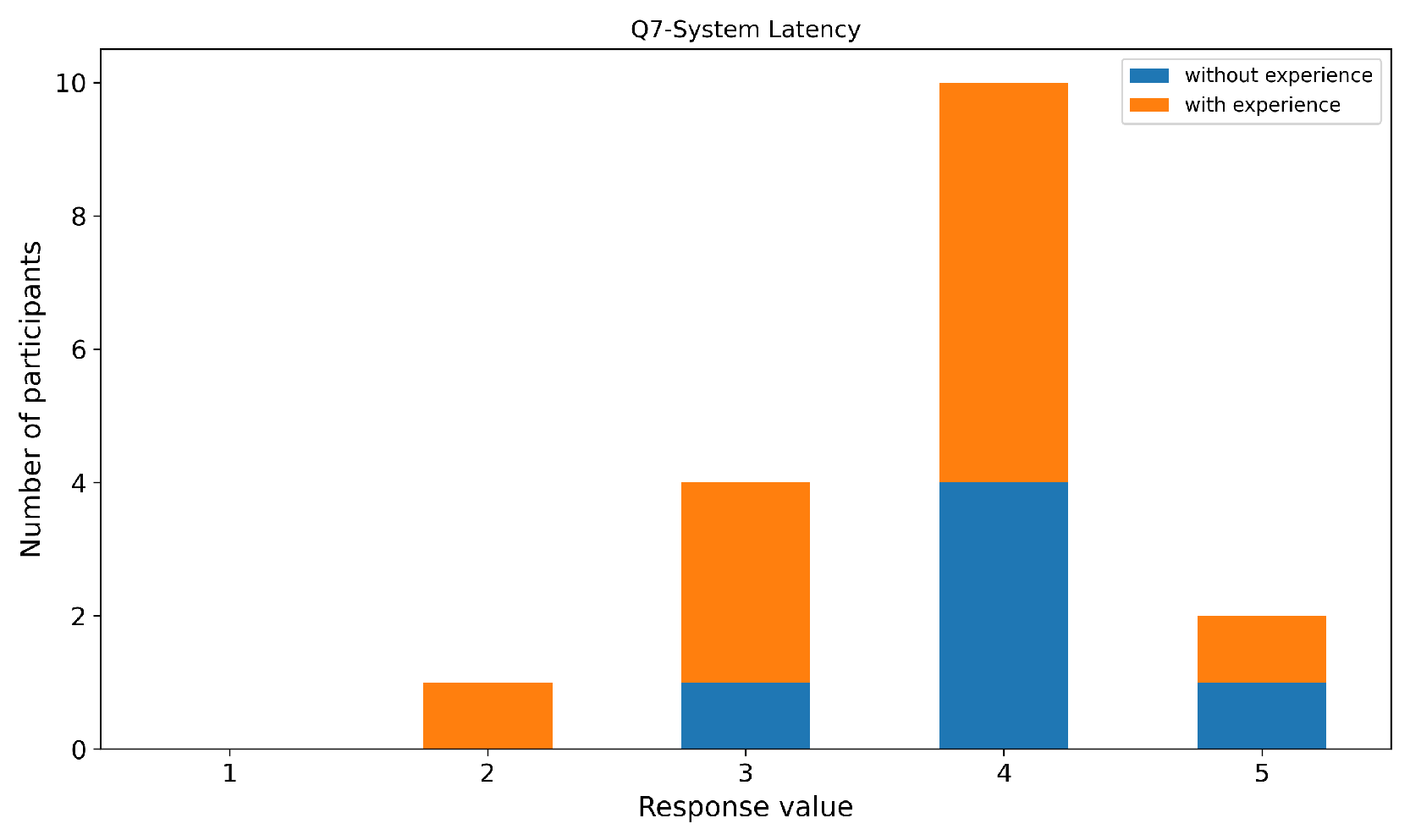

I did not perceive noticeable latency or delay between my actions and the robot’s response or visual updates.

Perceived system latency was generally rated as low. Most participants did not notice significant delays between their actions and the robot’s response or visual updates (

Figure 29). This subjective perception is consistent with the low frame rendering times measured in the technical evaluation. However, a small number of participants reported perceiving latency that was attributed not to communication or rendering delays, but to the intentionally limited physical motion speed of the robotic manipulators, which was lower than the users’ natural hand movements in VR.

-

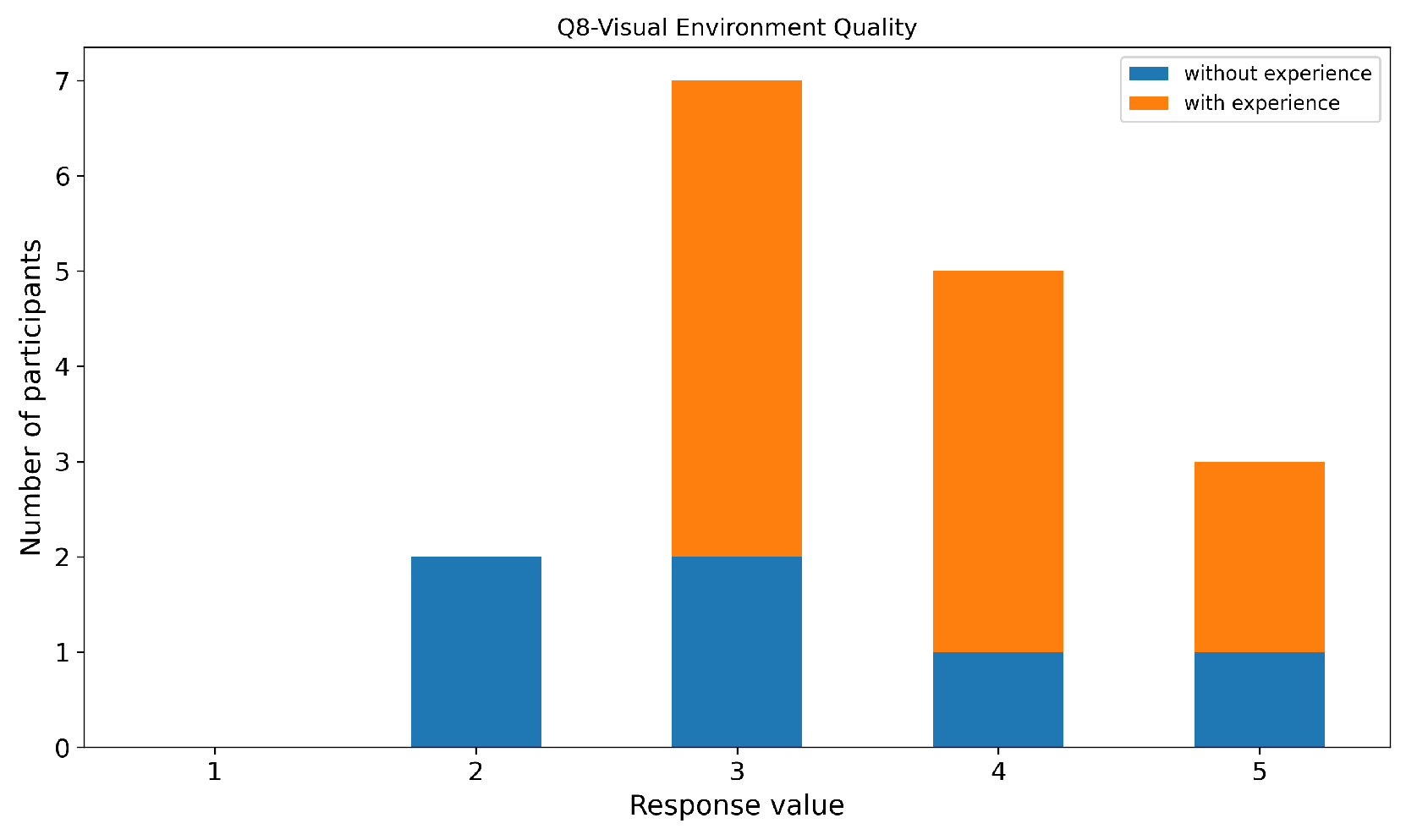

The virtual environment and point cloud visualization provided sufficient detail to judge distances, object sizes, and textures.

The quality of the virtual environment and point cloud visualization received mixed-to-positive ratings (

Figure 30). While a majority of participants reported that the visualization provided sufficient detail to accurately judge distances and object sizes, several users identified limitations related to object occlusion, and shadowing effects caused by the robotic arms.

-

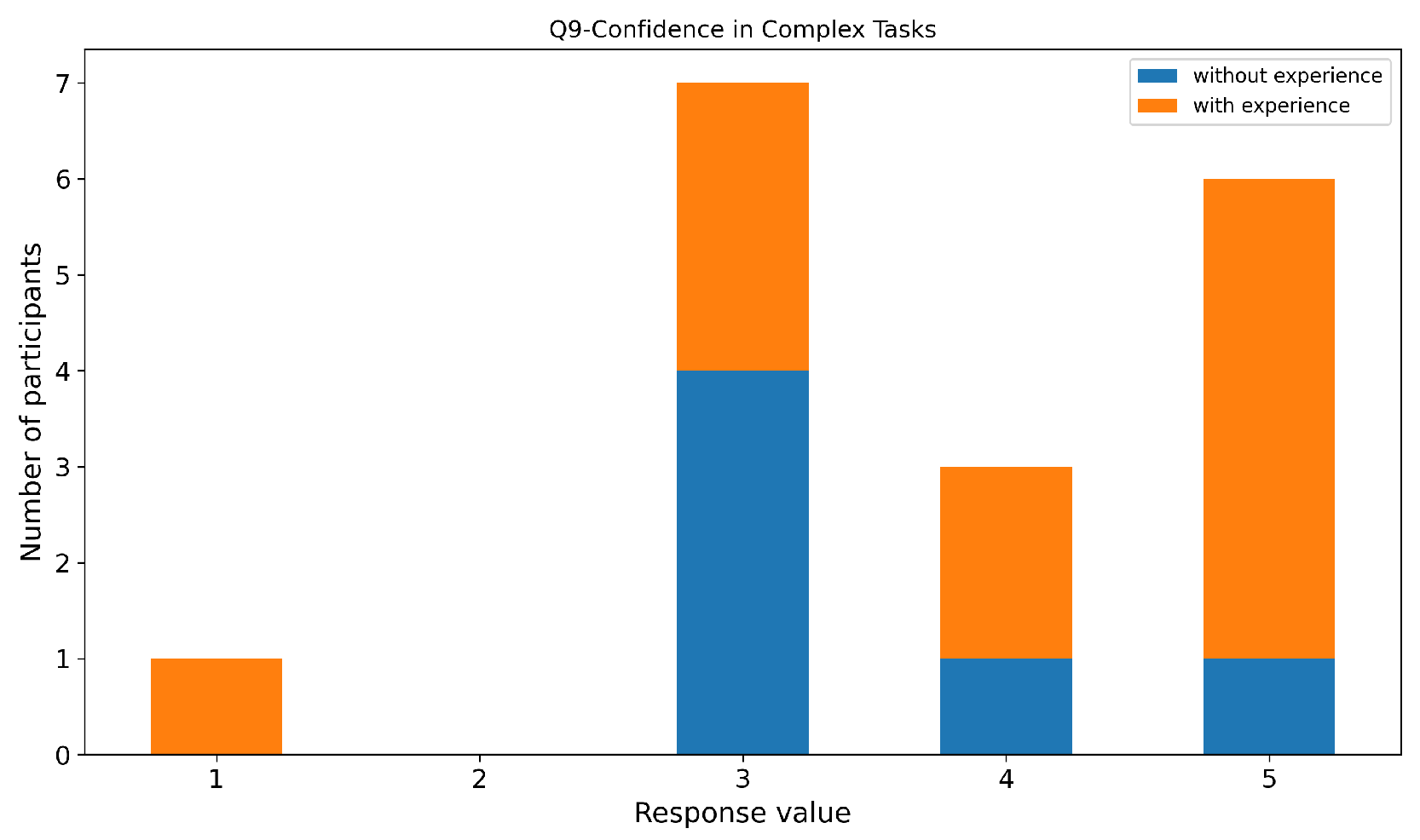

I felt confident when performing complex manipulations, trusting the visual feedback and the robot’s response.

User confidence during complex manipulations followed a similar trend (

Figure 31). Most participants reported feeling confident when performing tasks, though confidence was slightly lower in tasks requiring high precision or bimanual coordination.

-

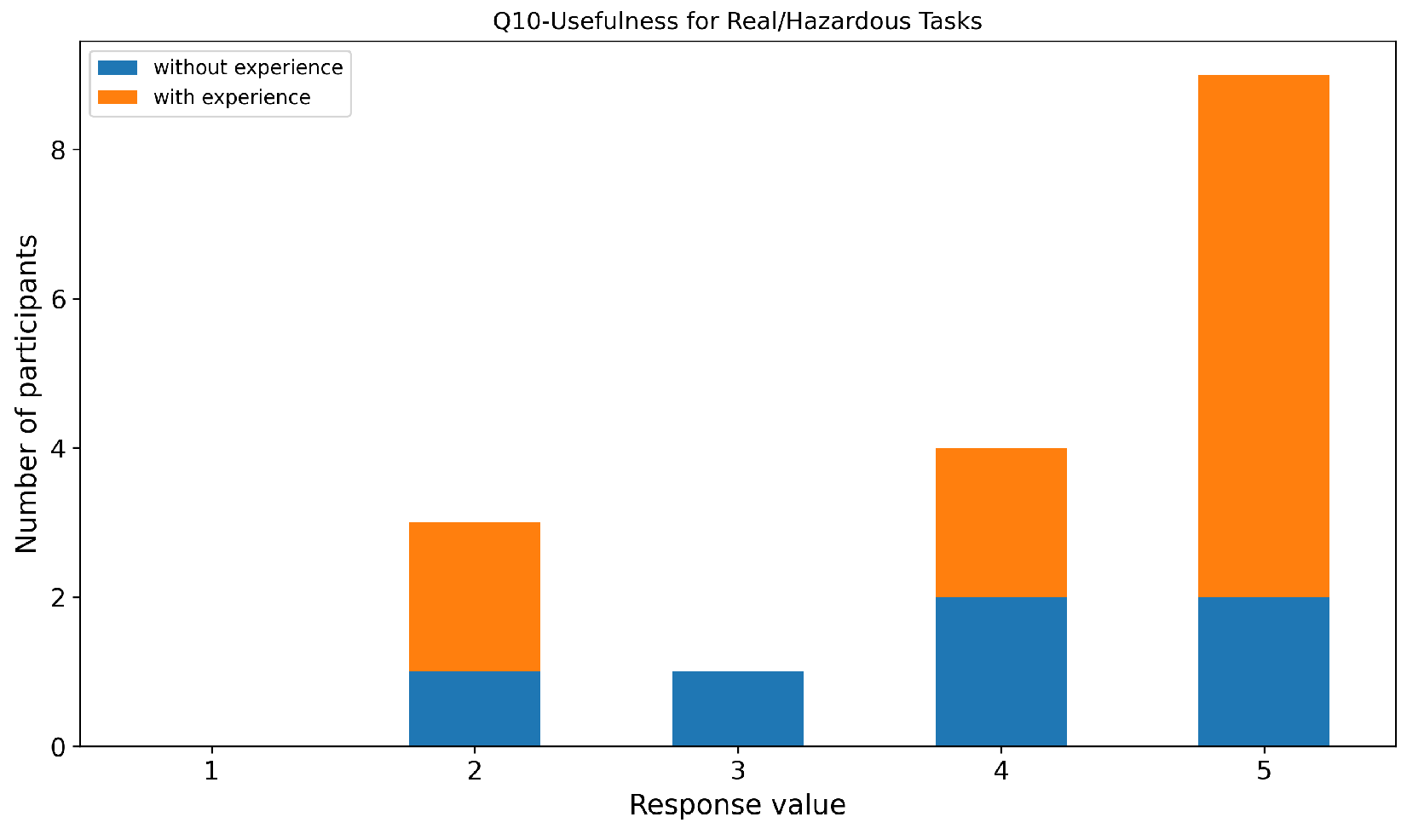

Considering ease of use and performance, this VR teleoperation system is useful for tasks in real or hazardous environments.

Finally, the system was rated as highly useful for teleoperation tasks in real or hazardous environments. The majority of participants selected values of 4 or 5 (

Figure 32), indicating strong perceived applicability of the system beyond the experimental setting.

The participants provided valuable insights into their experiences with the VR teleoperation system. Based on the feedback, we have identified several strengths of the system as well as areas that require further refinement.

Strengths

Low Latency and Precision: Several users highlighted the system’s low latency, which contributed to a smooth and responsive experience. The movements of the robotic arms, particularly the grippers, were praised for their precision and their ability to accurately follow the user’s hand orientation. This precision was especially notable in tasks that required fine manipulation, such as Writing and Folding.

Immersion and Visual Feedback: Many participants reported a strong sense of immersion and presence in the virtual environment. The system’s ability to provide realistic visual feedback, including the synchronized movement of the robot’s arms with the user’s hands, was cited as a key strength. Users felt they could easily estimate depth and object positioning.

Intuitiveness and Ease of Use: A recurring theme in the feedback was the intuitiveness of the system. Participants, regardless of their VR experience, found the controls to be easy to learn and use. The system’s simple and effective control scheme, allowing the manipulation of both arms simultaneously, was appreciated for its straightforwardness, especially by those with no prior VR experience.

Areas for Improvement

Shadows and Perception Issues: A significant number of participants pointed out that the shadows generated by the robot’s arms were problematic. These shadows often distorted their perception of the objects and the task environment, making it difficult to accurately position and manipulate objects, particularly in tasks requiring high precision. Many participants suggested that improving the handling of shadows or providing clearer visual cues for depth and object positioning would greatly enhance the experience.

In summary, participants found the VR teleoperation system to be immersive, intuitive, and responsive, with low latency and well-synchronized hand-arm movements. However, several areas for improvement were identified, particularly in terms of shadow handling. Addressing these issues will enhance the user experience, especially for tasks that require precise manipulation and depth perception.

4.3. Comparison with Related Work

In comparison with related works such as IMMERTWIN [

19], our system achieves competitive performance using more modest hardware. Specifically, our framework operates on an NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPU while generating a 1M-point cloud at 20 Hz, whereas IMMERTWIN relies on an RTX 4090 to render a 1.6M-point cloud at 10 Hz. Additionally, their experimental setup is not constrained to a fixed tabletop test scenario, making direct task-based comparisons less straightforward.

Compared to GELLO [

8], our approach demonstrates higher success rates in manipulation tasks such as handover and fold cloth when using the VR-based teleoperation mode. Furthermore, our system shows superior overall performance compared to OpenVR (SoftwareX) [

11], which may be partially attributed to implementation differences. While OpenVR is developed using C# with Unity and Python components, our framework is implemented entirely in standard C++23, emphasizing vectorized container-based iterations and avoiding unnecessary memory copies, resulting in improved computational efficiency and lower latency.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a VR-based teleoperation framework for dual-arm robotic manipulation

2, integrating immersive visualization through real-time point cloud rendering and intuitive motion mapping between the user and the robot. The system was evaluated through both objective technical measurements and a comprehensive user study involving participants with and without prior VR experience.

The technical evaluation demonstrated that the proposed framework achieves stable real-time performance, maintaining high frame rates and low rendering latency even with large point cloud sizes, using consumer-grade hardware. These results confirm the scalability and efficiency of the system for immersive teleoperation scenarios.

The user study results further indicate that the system offers high levels of comfort, presence, and intuitiveness, with minimal motion sickness reported by participants. Users perceived the control as responsive and reliable, and the majority considered the system highly suitable for teleoperation tasks in real or hazardous environments. Task-based performance analysis showed that prior VR experience can reduce completion times in certain tasks, particularly during initial interactions, while performance converges as task complexity increases.

Despite these positive results, several limitations were identified. Visual clarity during fine manipulation tasks was affected by depth perception challenges, object occlusions, and shadowing effects from the robotic arms. Additionally, coordinating both manipulators simultaneously posed difficulties for some users, especially those without prior VR experience. These findings highlight important directions for future work.

Future developments will focus on improving visual feedback, including enhanced depth cues and occlusion handling, as well as adaptive assistance mechanisms for bimanual coordination. Further studies involving more complex tasks and real-world deployment scenarios will also be conducted to validate the system’s applicability in operational environments.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed VR teleoperation system is an effective and scalable solution for immersive robotic manipulation, bridging the gap between intuitive human control and robust real-time robotic performance.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.T. and S.E.; methodology, P.B.; software, A.T and J.C.; validation, A.T. and P.N.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, A.T., S.E., J.C. and P.B.; resources, A.T.; data curation, A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.; writing—review and editing, A.T and P.N.; supervision, A.T. and P.N.; project administration, P.N.; funding acquisition, P.B. and P.N; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”, please turn to the

CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This work has been partially funded by FEDER Project 0124_EUROAGE_MAS_4_E (2021-2027 POCTEP Program) and by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation PID2022-137344OB-C31 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE.

Data Availability Statement

No aplicable.

Acknowledgments

Not aplicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UE |

Unreal Engine 5.6.1 |

| XR |

Extended Reality |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

References

- Tadokoro, S. (Ed.) Disaster Robotics, 1st ed.; Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics; Springer: Cham, 2019; p. 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinada, H.; Kurashiki, K.; Kondo, D.; Nagatani, K.; Kiribayashi, S.; Fuchida, M.; Tanaka, M.; Yamashita, A.; Asama, H.; Shibata, T. Dual-Arm Construction Robot with Remote-Control Function. In Disaster Robotics: Results from the ImPACT Tough Robotics Challenge; Tadokoro, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 195–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatani, K.; Kiribayashi, S.; Okada, Y.; Otake, K.; Yoshida, K.; Tadokoro, S.; Nishimura, T.; Yoshida, T.; Koyanagi, E.; Fukushima, M.; et al. Emergency response to the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants using mobile rescue robots. Journal of Field Robotics 2013, 30, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.T.; Becker, K.P.; Kurumaya, S.; Galloway, K.C.; Whittredge, G.; Vogt, D.M.; Teeple, C.B.; Rosen, M.H.; Pieribone, V.A.; Gruber, D.F.; et al. A Dexterous, Glove-Based Teleoperable Low-Power Soft Robotic Arm for Delicate Deep-Sea Biological Exploration. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 14779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakuba, M.V.; German, C.R.; Bowen, A.D.; Whitcomb, L.L.; Hand, K.; Branch, A.; Chien, S.; McFarland, C. Teleoperation and robotics under ice: Implications for planetary exploration. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Baishya, N.J.; Bhattacharya, B. A review on tele-manipulators for remote diagnostic procedures and surgery. CSI Transactions on ICT 2023, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, Y.T.; Hedlund-Botti, E.; Natarajan, M.; Heard, J.; Gombolay, M. The Impact of Stress and Workload on Human Performance in Robot Teleoperation Tasks. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2024, 40, 4725–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Shentu, Y.; Yi, Z.; Lin, X.; Abbeel, P. GELLO: A General, Low-Cost, and Intuitive Teleoperation Framework for Robot Manipulators. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; McCarthy, Z.; Jow, O.; Lee, D.; Chen, X.; Goldberg, K.; Abbeel, P. Deep imitation learning for complex manipulation tasks from virtual reality teleoperation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2018; pp. 5628–5635. [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa, K.; Sato, N.; Morita, Y. Considerations on interaction with manipulator in virtual reality teleoperation interface for rescue robots. In Proceedings of the 2023 32nd IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), 2023; IEEE; pp. 386–391. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.; Bartsch, A.; Barati Farimani, A. OpenVR: Teleoperation for manipulation. SoftwareX 2025, 29, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Tao, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Q. Comparative Performance Analysis of Rendering Optimization Methods in Unity Tuanjie Engine, Unity Global and Unreal Engine. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Smart World Congress (SWC) 2024, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, L.; Kaur, A. Merits and Demerits of Unreal and Unity: A Comprehensive Comparison. Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Green and Sustainable Technologies (ICCIGST) 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonsick, M.; Padir, T. A Systematic Review of Virtual Reality Interfaces for Controlling and Interacting with Robots. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, R.; Amerson, N.; Kim, B.; Rosen, E.; de Visser, E.J.; Phillips, E. Comparing Virtual Reality Interfaces for the Teleoperation of Robots. In Proceedings of the 2020 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), 2020; IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pace, F.; Manuri, F.; Sanna, A. Leveraging Enhanced Virtual Reality Methods and Environments for Efficient, Intuitive, and Immersive Teleoperation of Robots. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2021; IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.; Jha, D.K. A Virtual Reality Teleoperation Interface for Industrial Robot Manipulators. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomareva, P.; Trinitatova, D.; Fedoseev, A.; Kalinov, I.; Tsetserukou, D. GraspLook: a VR-based Telemanipulation System with R-CNN-driven Augmentation of Virtual Environment. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), 2021; IEEE; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audonnet, F.P.; Ramirez-Alpizar, I.G.; Aragon-Camarasa, G. IMMERTWIN: A Mixed Reality Framework for Enhanced Robotic Arm Teleoperation. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Solanes, J.E.; Muñoz, A.; Gracia, L.; Tornero, J. Augmented Reality-Based Interface for Bimanual Robot Teleoperation. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallipoli, M.; Buonocore, S.; Selvaggio, M.; Fontanelli, G.A.; Grazioso, S.; Di Gironimo, G. A virtual reality-based dual-mode robot teleoperation architecture. Robotica 2024, 42, 1935–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, H.; Kocer, B.B.; Kovac, M.; Pawar, V.M. VRTAB-Map: A Configurable Immersive Teleoperation Framework with Online 3D Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), 2022; IEEE; pp. 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.S.; Luebbers, M.B.; Roncone, A.; Hayes, B. Stereoscopic Virtual Reality Teleoperation for Human Robot Collaborative Dataset Collection. In Proceedings of the HRI 2024 Workshop on Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality for Human-Robot Interaction (VAM-HRI), Virtual, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Corke, P.; Haviland, J. Not your grandmother’s toolbox–the Robotics Toolbox reinvented for Python. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2021; IEEE; pp. 11357–11363. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Teaser of the proposed VR teleoperation framework for dual-arm manipulation. The operator uses an immersive VR headset and tracked controllers (left) to command a physical dual-arm robot (right). The VR interface includes a synchronized digital twin augmented with a dense colored point cloud (bottom-left), providing real-time spatial context to support depth perception and safe bimanual interaction during tasks such as cloth manipulation.

Figure 1.

Teaser of the proposed VR teleoperation framework for dual-arm manipulation. The operator uses an immersive VR headset and tracked controllers (left) to command a physical dual-arm robot (right). The VR interface includes a synchronized digital twin augmented with a dense colored point cloud (bottom-left), providing real-time spatial context to support depth perception and safe bimanual interaction during tasks such as cloth manipulation.

Figure 2.

System overview of the proposed VR teleoperation framework.

Figure 2.

System overview of the proposed VR teleoperation framework.

Figure 3.

Pbot platform and its virtual counterparts used in the proposed sim-to-real pipeline: (a) real robot, (b) Unreal Engine digital model, and (c) Webots simulation model.

Figure 3.

Pbot platform and its virtual counterparts used in the proposed sim-to-real pipeline: (a) real robot, (b) Unreal Engine digital model, and (c) Webots simulation model.

Figure 4.

Communication and component overview of the proposed system. UE interacts with the robotics back-end only through RobotMiddleware (static library), which bridges the XR application with RoboComp/Ice modules. Driver components (red) interface the physical devices (green): two Kinova Gen3 arms (via KinovaController), RS Helios LiDAR (via Lidar3D), Ricoh Theta camera (via RicoComponent), and ZED 2i stereo camera (via ZEDComponent). The Meta Quest 3 headset is connected through ALVR and exposed to UE via SteamVR.

Figure 4.

Communication and component overview of the proposed system. UE interacts with the robotics back-end only through RobotMiddleware (static library), which bridges the XR application with RoboComp/Ice modules. Driver components (red) interface the physical devices (green): two Kinova Gen3 arms (via KinovaController), RS Helios LiDAR (via Lidar3D), Ricoh Theta camera (via RicoComponent), and ZED 2i stereo camera (via ZEDComponent). The Meta Quest 3 headset is connected through ALVR and exposed to UE via SteamVR.

Figure 5.

Point-cloud rendering in Unreal Engine using the proposed GPU-based Niagara pipeline. (a) Webots simulation mode, where the reconstructed scene is visualized together with the robot digital model. (b) Real-robot operation, showing the colored 3D reconstruction of the workspace integrated into the same immersive interface, providing depth cues and spatial context for manipulation.

Figure 5.

Point-cloud rendering in Unreal Engine using the proposed GPU-based Niagara pipeline. (a) Webots simulation mode, where the reconstructed scene is visualized together with the robot digital model. (b) Real-robot operation, showing the colored 3D reconstruction of the workspace integrated into the same immersive interface, providing depth cues and spatial context for manipulation.

Figure 6.

Processor units measurement of Unreal points rendering (a) CPU thread usage. (b) GPU usage.

Figure 6.

Processor units measurement of Unreal points rendering (a) CPU thread usage. (b) GPU usage.

Figure 7.

Memory measurement of Unreal points rendering (a) RAM. (b) VRAM.

Figure 7.

Memory measurement of Unreal points rendering (a) RAM. (b) VRAM.

Figure 8.

Time measurement of Unreal points rendering (a) Frame period. (b)Frame per seconds.

Figure 8.

Time measurement of Unreal points rendering (a) Frame period. (b)Frame per seconds.

Figure 9.

End-to-end latency breakdown of the proposed VR teleoperation system.

Figure 9.

End-to-end latency breakdown of the proposed VR teleoperation system.

Figure 10.

Age and gender distribution of the 17 participants.

Figure 10.

Age and gender distribution of the 17 participants.

Figure 11.

Sequence of the first task: Pick and Place.

Figure 11.

Sequence of the first task: Pick and Place.

Figure 12.

Box plot showing Pick and Place task completion times.

Figure 12.

Box plot showing Pick and Place task completion times.

Figure 13.

Sequence of the second task: Cube Stacking.

Figure 13.

Sequence of the second task: Cube Stacking.

Figure 14.

Box plot showing times for stacking the first and second cubes. Stacking Cube 1: grasping the right cube and stacking it on the center cube. Stacking Cube 2: grasping the left cube and stacking it on top of Cube 1.

Figure 14.

Box plot showing times for stacking the first and second cubes. Stacking Cube 1: grasping the right cube and stacking it on the center cube. Stacking Cube 2: grasping the left cube and stacking it on top of Cube 1.

Figure 15.

Sequence of the third task: Toy Handover.

Figure 15.

Sequence of the third task: Toy Handover.

Figure 16.

Box plot showing times for toy handover and placement. Handover: grasping the toy, transferring it to the other hand. Drop: releasing the toy on the right side of the table.

Figure 16.

Box plot showing times for toy handover and placement. Handover: grasping the toy, transferring it to the other hand. Drop: releasing the toy on the right side of the table.

Figure 17.

Sequence of the fourth task: Cloth Folding.

Figure 17.

Sequence of the fourth task: Cloth Folding.

Figure 18.

Box plot showing times for picking up and folding the cloth. Take the cloth: both arms grasp the cloth in preparation for folding. Fold the cloth: both arms synchronously fold the cloth.

Figure 18.

Box plot showing times for picking up and folding the cloth. Take the cloth: both arms grasp the cloth in preparation for folding. Fold the cloth: both arms synchronously fold the cloth.

Figure 19.

Sequence of the fifth task: Writing “HI”.

Figure 19.

Sequence of the fifth task: Writing “HI”.

Figure 20.

Box plot showing times for taking the pen and writing on the table. Take the pen: the dominant arm grasps and lifts the pen from the table. Writing: the dominant arm writes `HI” on the table surface.

Figure 20.

Box plot showing times for taking the pen and writing on the table. Take the pen: the dominant arm grasps and lifts the pen from the table. Writing: the dominant arm writes `HI” on the table surface.

Figure 21.

Sequence of sixth task erase the written “HI”.

Figure 21.

Sequence of sixth task erase the written “HI”.

Figure 22.

Box plot showing times for erasing the text on the table.

Figure 22.

Box plot showing times for erasing the text on the table.

Figure 23.

Overall comfort survey results.

Figure 23.

Overall comfort survey results.

Figure 24.

Sense of presence survey results

Figure 24.

Sense of presence survey results

Figure 25.

Motion sickness survey results

Figure 25.

Motion sickness survey results

Figure 26.

Movement mapping intuitiveness survey results.

Figure 26.

Movement mapping intuitiveness survey results.

Figure 27.

Precision of manipulation survey results.

Figure 27.

Precision of manipulation survey results.

Figure 28.

Dual manipulator coordination survey results.

Figure 28.

Dual manipulator coordination survey results.

Figure 29.

Latency survey results.

Figure 29.

Latency survey results.

Figure 30.

Visual environment quality survey results.

Figure 30.

Visual environment quality survey results.

Figure 31.

Confidence in complex tasks survey results.

Figure 31.

Confidence in complex tasks survey results.

Figure 32.

Usefulness for real/Hazardous tasks survey results.

Figure 32.

Usefulness for real/Hazardous tasks survey results.

Table 1.

XR and teleoperation-related works (mostly 2020+): modality and setup. “N/S” denotes not specified.

Table 1.

XR and teleoperation-related works (mostly 2020+): modality and setup. “N/S” denotes not specified.

| Work |

Year |

XR |

Real |

Sim |

3D scene |

| Wonsick & Padir (Appl. Sci.) [14] |

2020 |

VR |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Hetrick et al. (SIEDS) [15] |

2020 |

VR |

Yes |

No |

Point cloud + cameras |

| De Pace et al. (ICRA) [16] |

2021 |

VR |

Yes |

N/S |

RGB-D capture |

| Ponomareva et al. (ICAR) [18] |

2021 |

VR |

N/S |

N/S |

Digital twins (R-CNN) |

| Stedman et al. (ISMAR Adjunct) [22] |

2022 |

VR |

Yes |

N/S |

Online 3D recon |

| García et al. (Appl. Sci.) [20] |

2022 |

AR |

Yes |

No |

Holographic overlays |

| Rosen & Jha (arXiv) [17] |

2023 |

VR |

Yes |

No |

N/S |

| Tung et al. (VAM-HRI) [23] |

2024 |

VR |

Yes |

N/S |

Stereo 2D video |

| Gallipoli et al. (Robotica) [21] |

2024 |

VR |

Yes |

N/S |

Digital twin (N/S) |

| Wu et al. (IROS) [8] |

2024 |

– |

Yes |

No |

No |

| George et al. (SoftwareX) [11] |

2025 |

VR |

Yes |

No |

N/S |

| Ours |

2025 |

VR |

Yes |

Yes |

Dense colored point cloud |

Table 2.

XR and teleoperation-related works (mostly 2020+): relation to our proposal.

Table 2.

XR and teleoperation-related works (mostly 2020+): relation to our proposal.

| Work |

Key aspects and relation to our proposal |

| Wonsick & Padir (Appl. Sci.) [14] |

Systematic review (2016–2020) summarizing design dimensions for VR robot operation; motivates XR interfaces but does not provide a unified sim/real system. |

| Hetrick et al. (SIEDS) [15] |

Compares VR control paradigms for dexterous tasks on Baxter; includes live point-cloud reconstruction in VR. Not focused on sim-to-real unification nor engine-agnostic modularity. |

| De Pace et al. (ICRA) [16] |

RGB-D capture of robot+environment with VR-controller teleoperation; strong perceptual angle, but not a dual-arm unified sim/real workflow. |

| Ponomareva et al. (ICAR) [18] |

Augmented virtual environment with object detection + digital twin rendering; improves operator workload/time. Not a general sim/real dual-arm architecture. |

| Stedman et al. (ISMAR Adjunct) [22] |

Configurable immersive teleoperation baseline using RTAB-Map for online reconstruction; highlights challenges of presenting evolving dense 3D data (often mobile-robot oriented). |

| García et al. (Appl. Sci.) [20] |

AR (HoloLens) + gamepad for bimanual industrial robot teleoperation; addresses ergonomics/learning, but not immersive VR with dense point-cloud digital twin or sim/real bridging. |

| Rosen & Jha (arXiv) [17] |

Shows constraints of industrial arms (black-box position controllers) and proposes VR command filtering; complementary to our focus on unified architecture + perception-rich digital twin. |

| Tung et al. (VAM-HRI workshop) [23] |

Targets dataset collection for human–robot collaboration with immersive stereoscopic egocentric feedback; not a dual-arm sim/real digital-twin framework with dense 3D reconstruction. |

| Gallipoli et al. (Robotica) [21] |

Dual-mode teleoperation architecture with mode switching for safety/flexibility; related in intent (safety + workflow), but does not emphasize high-density point-cloud rendering + sim/real unification. |

| Wu et al. (arXiv / IROS) [8] |

Low-cost kinematic replica improves demonstration collection vs. VR controllers/3D mice; supports bi-manual/contact-rich tasks, but lacks immersive digital-twin perception and sim/real XR unification. |

| George et al. (SoftwareX) [11] |

Open-source Oculus-based VR teleoperation for Franka Panda aimed at demonstration collection; complements our goals but does not provide a dense-3D digital twin nor a simulation+real unified interface. |

| Ours |

Unified UE interface spanning Webots+real dual-arm control, modular middleware abstraction, closed-loop digital twin with scalable GPU point-cloud rendering and empirical validation. |

Table 3.

Communication latency as a function of point cloud size over a 1 Gbps network.

Table 3.

Communication latency as a function of point cloud size over a 1 Gbps network.

| Number of points |

Communication latency |

Data size |

| 50K |

14-17 ms |

3.6 Mbits |

| 500K |

76-80 ms |

36 Mbits |

| 1M |

91-98 ms |

72 Mbits |

| 1.5M |

140-151 ms |

108 Mbits |

| 2M |

184-196 ms |

144 Mbits |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).