1. Introduction

In the twenty-first century, the most pressing threats to cultural heritage sites arise not primarily from direct destruction or neglect, but from indirect and multi-layered transformation processes associated with large-scale development projects. Dams, energy infrastructure, new transportation corridors, and rural resettlement policies generate irreversible spatial and semantic disruptions, particularly for defensive structures located in rural landscapes. While such interventions do not always result in the complete physical loss of historic structures, they frequently detach them from their topographic context, visual control networks, and functional continuities, thereby increasing their vulnerability.

Within the international literature, these processes are commonly examined through frameworks that foreground the tension between development and conservation, with particular emphasis on the indirect impacts of large-scale infrastructure projects on heritage sites. In this context, it is widely argued that heritage management must be integrated with sustainable development objectives and that conservation instruments require corresponding adaptation (UNESCO, 2011). Similarly, the need for impact-assessment-based methodological frameworks capable of anticipating and evaluating the effects of major development projects on heritage assets has become a central concern of contemporary conservation discourse (ICOMOS, 2011). Recent studies further demonstrate that assessments limited to structural integrity alone are insufficient; spatial parameters such as topography, accessibility, visual relationship networks, and contextual continuity must also be treated as integral components of conservation decision-making. This requirement becomes particularly critical in the case of rural defensive heritage.

Rural fortresses constructed during the medieval and early modern periods were not merely military buildings but integral components of broader defensive systems that controlled valleys, passes, and settlement networks through strong visual and spatial relationships with their surroundings. The historical and cultural significance of these structures is therefore inseparable from the topography, fields of view, and access routes that defined their defensive logic. Consequently, the transformation or loss of this contextual framework leads to the erosion of defensive rationales and representational values, regardless of whether the structures themselves remain physically intact.

Despite this growing awareness, a substantial proportion of conservation approaches developed for rural defensive heritage under development pressure remain largely descriptive, offering limited analytical capacity for the comparative assessment of risks or the systematic definition of intervention priorities. In contexts shaped by large-scale infrastructure projects such as dams, there is a pronounced lack of transferable decision-support frameworks capable of jointly addressing topographic adaptation, anthropogenic threats, and material sensitivity within an integrated evaluative structure.

Accordingly, contemporary debates on the conservation of rural defensive heritage are no longer confined to the question of how structures should be repaired, but increasingly engage with which sites should be addressed, under which risks, with what level of priority, and through which intervention strategies. Responding to these questions necessitates the development of multi-criteria, comparable, and reproducible conservation models that support qualitative observations with quantitative or semi-quantitative assessment tools.

1.1. Dam-Induced Landscape Transformation and the Contextual Vulnerability of Rural Defensive Structures

Large-scale dam projects should be understood not only as hydraulic or energy infrastructures, but as spatial interventions that profoundly transform settlement patterns, transportation networks, and cultural landscapes. In mountainous and valley-based geographies in particular, dams generate multi-layered forms of vulnerability for defensive structures whose historical significance is inseparable from specific topographic relationships. Such interventions often produce heritage sites that remain physically intact yet are severed from their environmental and visual context, resulting in structures that are preserved in situ but detached from the spatial systems that once sustained their meaning.

Within international conservation discourse, the impacts of dams and energy infrastructures on cultural heritage are increasingly addressed through a critical lens. It is emphasized that the effects of large-scale development projects should not be assessed solely in terms of physical loss or structural damage, but also through indirect processes such as landscape fragmentation, the transformation of access networks, and the erosion of contextual continuity (UNESCO, 2011). To anticipate and manage these transformations, the development and implementation of impact-assessment-based approaches capable of systematically evaluating the effects of development projects on heritage values have been strongly advocated (ICOMOS, 2011). Accordingly, heritage conservation is increasingly defined as a holistic challenge that must be addressed at both the landscape and contextual scales, rather than being confined to the scale of individual structures (UNESCO, 2011).

In Türkiye, one of the most visible manifestations of this debate has been the case of Hasankeyf, where extensive portions of the historic settlement fabric and monumental heritage were submerged due to dam construction. However, the impacts of dams on heritage are not limited to sites that are entirely lost. Structures that remain above reservoir level may retain their physical presence while experiencing profound alterations in valley relationships, access routes, and visual control networks. This condition demonstrates that even “preserved” structures may undergo significant losses of identity and meaning.

The Yusufeli region provides a particularly instructive context for examining the indirect effects of dam-induced landscape transformation on rural defensive heritage. Constructed on the Çoruh River, the Yusufeli Dam necessitated the relocation of the district center and numerous rural settlements, fundamentally reshaping historical transportation corridors, settlement–fortress relationships, and visual dominance networks within the valley. The fortresses of Bahçeli, Çevreli (Peterek), Kılıçkaya (Ersis), and Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni), although remaining physically intact above the reservoir level, have lost substantial portions of the topographic and landscape relationships that once underpinned their defensive logic.

The vulnerability of rural defensive structures differs markedly from that of urban monumental buildings. Fortresses were conceived not as isolated architectural objects but as spatial systems operating in conjunction with valleys, passes, paths, and lines of sight. Transformations affecting any component of this system directly undermine the structures’ capacity to generate meaning. In the Yusufeli context, the artificial reservoir landscape, newly introduced transportation axes, and altered microclimatic conditions collectively produce a multi-layered vulnerability environment for these sites.

This condition necessitates a reconsideration of conservation approaches for rural defensive heritage. For fortresses that largely retain their physical integrity but have experienced severe contextual disruption, traditional restoration- and repair-oriented strategies are insufficient. Instead, there is a need for analytical frameworks that jointly address topographic adaptation, anthropogenic threats, and material sensitivity, enabling risks to be compared and intervention priorities to be explicitly defined (ICOMOS, 2011).

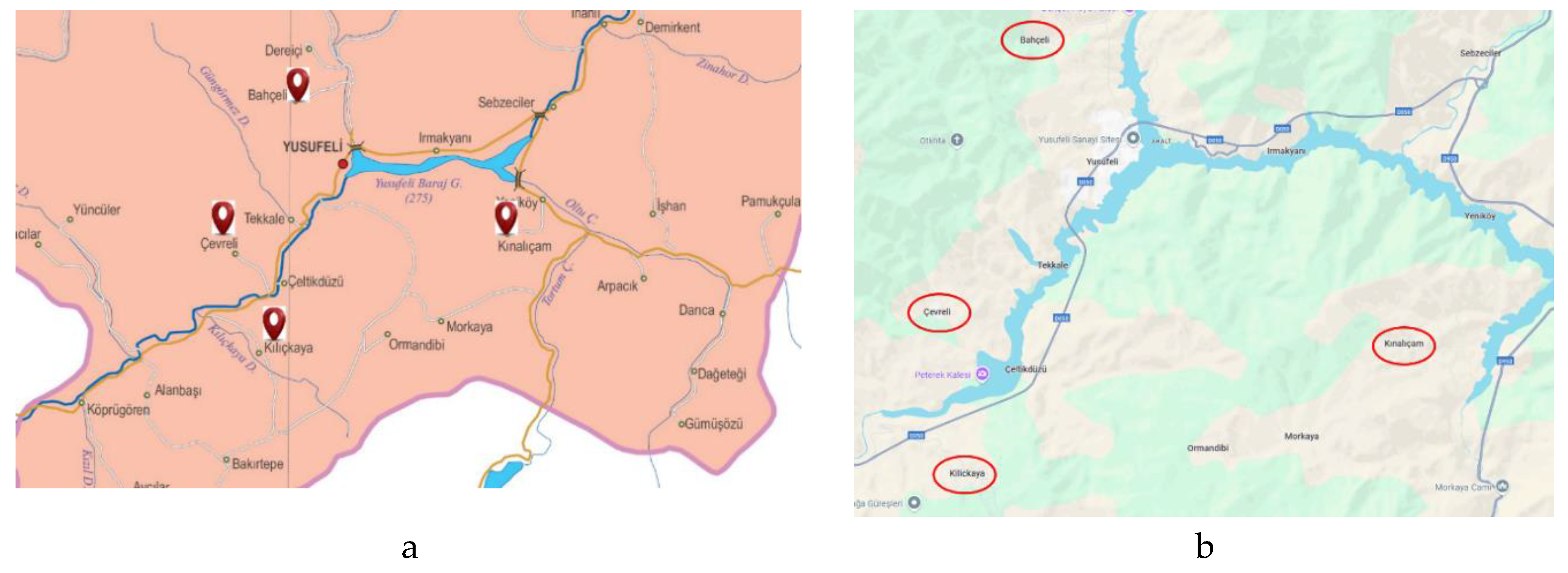

The Yusufeli district and its surrounding rural defensive structures constitute the empirical field in which this analytical framework is developed and tested. The spatial relationship between the four case-study fortresses (Bahçeli, Çevreli/Peterek, Kılıçkaya/Ersis, and Kınalıçam/Asparaşeni), the dam reservoir, and the primary transportation axes is presented in

Figure 1, which provides the spatial basis for the risk and vulnerability indicators—such as access, contextual disruption, and exposure to threats—discussed in subsequent sections (

Figure 1).

1.2. Research Question, Methodological Positioning, and Rationale for the Proposed Model

This study seeks to develop an analytical and comparable assessment framework for the conservation of rural defensive heritage under the influence of dam projects and similar large-scale development interventions. Existing approaches in the literature tend to address rural fortresses primarily through historical–typological analyses or building-scale restoration debates, while offering limited guidance on how vulnerabilities arising from disrupted relationships with topography, landscape, and access systems can be measured and prioritized.

From this perspective, the study is structured around the following research question:

Can a transferable conservation assessment model be developed for rural defensive structures affected by dam-induced landscape transformation, integrating topographic adaptation, anthropogenic threats, and material sensitivity within a unified analytical framework?

In response, the study aims to contribute at three methodological levels. First, it reconceptualizes the vulnerability of rural defensive heritage beyond physical deterioration alone, incorporating spatial parameters such as loss of topographic context, weakening of visual dominance, and transformation of access systems. Second, it proposes a multi-criteria risk assessment approach that renders anthropogenic pressures—such as post-dam microclimatic changes, new transportation infrastructures, and settlement reconfiguration—comparable at the building scale. Third, it directly links material analysis findings to intervention decisions, embedding a data-driven and locally material-sensitive conservation logic as an integral component of the model.

Within this framework, the Yusufeli fortresses are treated not merely as descriptive case studies but as an analytical laboratory in which the proposed assessment model is developed and tested. The fortresses of Bahçeli, Çevreli (Peterek), Kılıçkaya (Ersis), and Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni), characterized by differing topographic settings, varying degrees of dam impact, and diverse anthropogenic threat profiles, enable a comparative evaluation of the model’s performance. In this way, the study moves beyond site-specific conservation recommendations to propose a decision-support tool applicable to rural defensive heritage experiencing similar contextual transformations.

The proposed model is grounded in a multi-criteria evaluation logic that integrates qualitative and quantitative data. Anthropogenic threats are quantified through impact and probability parameters, while topographic risks, material sensitivity, and indicators of contextual disruption are weighted to generate structure-specific vulnerability and prioritization indices. This approach enables conservation decisions to be based not on intuitive or purely descriptive judgments, but on transparent, comparable, and traceable criteria.

In this respect, the study provides a methodological framework aligned with the principles of contextual integrity, risk-based conservation, and preventive approaches emphasized by UNESCO and ICOMOS. Rather than reiterating these principles at a conceptual level, the model translates them into operational indicators, tables, and graphical representations, thereby offering a practical and methodologically grounded contribution to the conservation of rural defensive heritage.

1.3. Rural Defensive Heritage, Development-Induced Risks, and the Methodological Gap in the Literature

The literature on the conservation of rural defensive structures has long been shaped by discussions of historical origins, typological characteristics, and military functions. Medieval fortresses and frontier defense systems, particularly in European and Caucasian contexts, have been examined primarily through political geography and power relations, while their relationship with topography has often been addressed at a descriptive level (Lang, 1966; Toumanoff, 1967; Rapp, 2014). Although these studies demonstrate the historical significance of defensive architecture, they offer limited insight into the vulnerability regimes generated under contemporary development pressures.

In recent years, the development-induced risk perspective has gained prominence within cultural heritage studies, critically addressing the direct and indirect impacts of large-scale infrastructure projects on heritage sites. Interventions such as dams, energy facilities, and transportation infrastructures are shown to transform not only the physical integrity of heritage assets but also cultural landscapes, spatial continuity, and representational values (González-Varas, 2018; Labadi, 2017). This approach has supported the institutionalization of risk-based conservation and preventive strategies at the international level, with concepts of context, landscape, and indirect impact occupying a central position in UNESCO and ICOMOS policy documents (UNESCO, 2011; ICOMOS, 2011).

The cultural landscape literature provides an important conceptual expansion of this debate by framing landscape as a dynamic cultural product shaped through long-term human–environment interaction, thereby necessitating the evaluation of heritage sites within broader networks of spatial relationships (Ashworth, Graham & Tunbridge, 2007; Fairclough et al., 2018). However, in the case of defensive structures, landscape is frequently treated as a visual backdrop rather than as an analytical object. Key components that directly structure defensive logic—such as topographic adaptation, lines of sight, and access systems—are rarely translated into measurable analytical parameters.

At the same time, risk-based conservation and vulnerability assessment models have been developed predominantly for urban heritage, monumental architecture, or individual historic buildings. While these models successfully quantify structural damage, material deterioration, and environmental factors through defined indicators, they inadequately represent the specific conditions of rural defensive structures that operate through integrated relationships with topography, access, and visual dominance (Jokilehto, 1999; Feilden, 2003; Letellier et al., 2007). As a result, the existing literature lacks a multi-criteria, transferable assessment framework capable of jointly addressing context, risk, and intervention priorities for rural defensive heritage.

This methodological gap becomes particularly pronounced in regions experiencing radical landscape transformation through dam projects. Defensive structures that remain physically intact yet lose their environmental, visual, and functional contexts are often treated as cases of “secondary loss,” without clear criteria for defining, measuring, or prioritizing such losses within conservation decision-making processes (González-Varas, 2018; Harrison, 2015). This condition underscores the need for conservation approaches that move beyond descriptive analyses toward comparable, measurable, and decision-oriented methodological frameworks.

Against this background, the present study addresses this gap through the case of the Yusufeli fortresses by integrating topographic adaptation, anthropogenic threats, and material sensitivity within a unified assessment system. Rather than reiterating existing theoretical debates, the study seeks to operationalize them through concrete indicators, analytical tables, and comparative evaluations, thereby proposing an applicable and transferable assessment model for the conservation of rural defensive heritage.

2. Materials and Methods

To address the methodological gap identified in the conservation of rural defensive heritage under development pressure, this study adopts a multi-layered analytical approach that integrates physical, spatial, and contextual data into a unified assessment framework. Rather than relying on descriptive field reporting, the method is designed as a decision-oriented and reproducible evaluation protocol capable of supporting comparative prioritization under conditions of landscape transformation.

The analytical framework was developed to assess both the current condition and the representational potential of historic fortresses affected by the Yusufeli Dam (2013–2023). The core dataset consists of laser-scanning-derived point cloud data and deterioration–intervention mapping produced for each fortress. These documentation outputs are systematically combined with plan–topography relationships, visual dominance analyses, and the classification of anthropogenic threats, enabling the translation of field observations into structured analytical indicators.

The method is grounded in a conservation–documentation approach that emphasizes the systematic integration of metric documentation into conservation decision-making processes (Letellier et al., 2007). Laser scanning and mapping data are not treated as illustrative material, but as primary analytical inputs informing the evaluation of topographic adaptation, contextual disruption, and exposure to anthropogenic risks. In this way, the methodology moves beyond building-scale condition assessment to incorporate landscape-level transformations, access reconfiguration, and altered visual relationships as measurable components of vulnerability.

Through this integrated structure, the study formulates a transferable assessment protocol that allows the direct and indirect impacts of large-scale infrastructure projects on rural defensive heritage to be evaluated in a comparable and traceable manner. The proposed methodological framework thus supports the generation of structure-specific vulnerability and prioritization outcomes, rather than site-specific descriptive narratives.

2.1. Data Sources and Scope

The study examines four rural fortresses located in the Yusufeli region: Bahçeli, Çevreli (Peterek), Kılıçkaya (Ersis), and Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni). For each site, a core documentation dataset is available, consisting of laser-scanning-derived point cloud data, deterioration and intervention mapping, and basic photographic documentation. This dataset enables the analysis of topographic positioning, access conditions, and visual dominance relationships at both site and landscape scales.

Material characterization data, including petrographic and XRD analyses, are available for the Bahçeli, Çevreli, and Kınalıçam fortresses. For Kılıçkaya Fortress, material analysis data are limited, requiring the material-related component of the model to operate with differentiated confidence levels. This approach is adopted deliberately to ensure that variations in data availability are explicitly and transparently represented within the assessment framework, rather than being obscured or normalized.

2.2. Five-Stage Assessment Protocol

The proposed model is structured as a five-stage sequential assessment protocol (

Figure 2). This methodological workflow follows a logic consistent with impact-assessment approaches developed for anticipating and managing the effects of large-scale interventions on cultural heritage (ICOMOS, 2011; ICCROM).

The assessment protocol comprises the following stages:

Definition of the historical and geopolitical framework

Field documentation and topographic modelling

Material characterization

Analysis of anthropogenic threats

Development of the conservation and intervention framework

This five-stage structure is designed to integrate heterogeneous data types into a coherent analytical process and to establish a comparable evaluation basis for each fortress.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the integrated analytical approach adopted in this study, illustrating the identification, scaling, and selection of physical, socio-cultural, and documentary layers to be represented within the assessment framework.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the integrated analytical approach adopted in this study, illustrating the identification, scaling, and selection of physical, socio-cultural, and documentary layers to be represented within the assessment framework.

2.3. Scoring Logic and Calculation Framework

This study translates standard risk management principles, including risk identification, analysis, and evaluation as defined in ISO 31000, into a numerical scoring system adapted to the contextual vulnerabilities of rural defensive heritage (ISO, 2018). The integration of different risk and vulnerability components within a single evaluation framework is based on a weighted summation approach commonly used in the multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) literature (Belton and Stewart, 2002).

Accordingly, anthropogenic risks, topographic–contextual vulnerabilities, and material sensitivity are calculated as separate modules for each fortress and then combined into a composite vulnerability index. The calculation logic is summarized below.

For each anthropogenic threat, the site-based risk value is defined as the product of impact and probability:

where

I represents the level of impact, and

P represents the probability of occurrence (1–3: low, medium, high).

The overall anthropogenic risk score for each fortress is calculated as the arithmetic mean of all identified threat-based risk values:

B. Topographic and Contextual Vulnerability (TC)

Topographic and contextual vulnerability is defined as the weighted sum of four normalized sub-indicators:

These sub-indicators represent visual dominance disruption (V), access fragmentation (A), landscape fragmentation (L), and microclimatic exposure (M). Each indicator is normalized within the 0–1 range.

For fortresses where petrographic and XRD data are available, material sensitivity is evaluated through the compatibility between original stone and mortar characteristics and existing or proposed interventions. In cases where material data are unavailable, this module is excluded from the calculation and explicitly addressed within the data completeness index.

The three main modules are integrated into a composite vulnerability index using a weighted summation approach:

where alpha + beta + gamma = 1.

Weight coefficients are defined according to the contextual priorities of the study.

To support the interpretability of the model outputs, a data completeness ratio is calculated for each fortress:

where k represents the number of available indicators and K denotes the total number of theoretically defined indicators.

An overview of the applied modules, indicators, scales, and data sources is provided in

Table 1.

2.4. Five-Stage Assessment Protocol

The proposed model operates through five sequential stages designed to translate documentation data into conservation decisions within a reproducible analytical workflow (

Figure 5). The framework follows a logic consistent with approaches developed for the identification, analysis, and management of the impacts of large-scale interventions, such as dams, transportation infrastructures, and landscape transformations, on cultural heritage. In particular, the methodological structure aligns with the Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) sequence of establishing context, analysing impacts, and generating decisions and monitoring strategies.

The investigated rural defensive structures are assessed not merely as physical remains, but within their broader contexts of frontier geography, administrative change, military and logistical networks, and local settlement relations. Through archival research and the interpretation of historical topography, the strategic rationale behind site selection and patterns of continuity or transformation in use are identified. This stage ensures that risk and vulnerability indicators produced in subsequent phases are grounded in contextual meaning rather than functioning as abstract numerical scores.

Measured drawings, photogrammetric field production, and laser scanning (point cloud) data are jointly evaluated to establish the fortress–topography relationship through a multi-scale documentation set. This documentation process is structured in accordance with metric survey specifications defined for cultural heritage structures, including criteria such as measurement accuracy, use of ground control points, data integrity, and output comparability (Historic England, 2018). The primary objective of this stage is to translate spatial characteristics such as approach routes, lines of sight, terrain integration, and rupture points into measurable and comparable representations. As a result, contextual indicators including access fragmentation, loss of visual dominance, and landscape fragmentation are analysed and reported through documentation-based spatial readings rather than qualitative observation alone.

Petrographic and XRD analyses conducted on mortar and stone samples are used to determine the composition of original materials, aggregate properties, and binder–aggregate relationships. The main objective of this stage is to transform laboratory findings into principles that inform compatible intervention strategies, rather than treating analytical results as purely descriptive data. As emphasized in technical guidelines for mortar analysis, the combined evaluation of mineralogical, petrographic, chemical, and proportional characteristics is critical to the reliability and applicability of the results.

Anthropogenic threats are classified to include dam and reservoir effects, new road construction and vibration, microclimatic changes and salt crystallization processes, geotechnical risks such as landslides and rockfall, and vandalism or illicit excavations. The aim of this stage is not only to identify threats, but to situate them within a comparable risk framework for each fortress, thereby producing analytical inputs for conservation prioritization. The use of shared terminology and classification systems, particularly for deterioration types such as salt crystallization, surface loss, and crack development, supports the traceability and comparability of risk assessments.

Topographic, material, and threat-related data generated in the preceding stages are integrated to define (i) intervention approaches compatible with local and original materials, (ii) implementation decisions sensitive to topographic access and logistical constraints, and (iii) monitoring and preventive maintenance strategies. This stage represents the point at which documentation and analytical outputs are directly translated into decision-making tools, enabling priority ranking among fortresses and the definition of long-term monitoring strategies. Subsequently, a modular assessment matrix is presented in tabular form, matching the applied indicators, scoring scales, and data sources. This table constitutes the structural backbone of the Methods section and ensures the transparency of the proposed model.

2.5. Score Integration, Uncertainty Management, and Prioritization Outputs

This section defines how the module scores produced in

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3 (AR, TC, MS, DCI) are rendered comparable across the investigated fortresses, integrated into a single priority ranking, and interpreted in a way that explicitly reflects uncertainty resulting from data gaps. The approach is consistent with the core logic of risk management, including the stages of identification, analysis, evaluation, and decision-making (ISO, 2018). The aggregation of module scores into a single composite index follows a weighted summation approach commonly applied in the multi-criteria decision analysis literature (Belton and Stewart, 2002).

2.5.1. Normalization and Comparability

As the different modules are defined on different numerical scales, the first step involves scale harmonization. Topographic and contextual vulnerability (TC), material sensitivity (MS), and the data completeness and confidence index (DCI) are defined within a 0 to 1 range. The anthropogenic risk score (AR), derived from the product of impact and probability, takes values between 1 and 3. To enable comparability with the other modules, AR is therefore normalized to a 0 to 1 range.

Normalization of AR is performed as follows:

The material sensitivity and intervention compatibility module (MS) is constructed according to a compatibility-based logic rather than a direct risk logic. Higher MS values indicate greater compatibility between original materials and proposed interventions, and thus lower potential risk. However, because the prioritization process is formulated in terms of risk and vulnerability, the MS module is transformed into a risk-oriented variable:

Through this transformation, cases with high material compatibility do not generate urgency in prioritization, whereas increasing incompatibility is directly reflected as a risk component. This approach is consistent with international conservation principles emphasizing compatibility, minimum intervention, and reversibility (Australia ICOMOS, 2013).

2.5.2. Composite Priority Index (PI)

Following normalization, a composite priority index is calculated for each fortress. This index is defined as the weighted sum of the three main modules:

Here, w_AR, w_TC, and w_MS represent the weighting coefficients assigned to each module, and their sum must equal 1. In the initial application of the model, an equal-weight approach may be adopted to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Alternatively, weights may be derived and reported through expert judgement-based methods, such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) (Saaty, 1980).

To evaluate the influence of weight selection on the results, a basic sensitivity check is recommended. Within this check, the stability of the fortress ranking is observed under scenarios in which the weighting coefficients are increased or decreased within limited ranges. This procedure allows an assessment of whether prioritization outcomes are robust or sensitive to changes in weighting assumptions.

2.5.3. Data Completeness (DCI) as an Uncertainty Filter

One of the core strengths of the proposed model is that it explicitly reports data gaps rather than obscuring them. The Data Completeness and Confidence Index (DCI) is designed as a separate evaluative layer indicating the reliability of the results produced for each fortress. This approach is consistent with international conservation principles that emphasize levels of evidence and documentation adequacy in decision-making processes (Australia ICOMOS, 2013).

The DCI can be applied in two different ways:

In this case, decisions are evaluated through a two-dimensional reading based on both priority and confidence.

- B.

PI is adjusted by DCI to produce a single “actionable priority” score:

While the second approach may offer practical advantages in applied contexts, the first approach generally provides a more robust academic interpretation. In cases where PI values are high but DCI values are low, comprehensive interventions are not immediately recommended. Instead, priority is given to data completion accompanied by parallel risk-reducing temporary measures. This logic is consistent with the “evidence first, irreversible decisions later” principle emphasized in heritage impact assessment and risk management literature (ICOMOS, 2011).

2.5.4. Decision Matrix: Interpreting PI and DCI Together

The model presents its results not merely as a numerical ranking, but as a decision-oriented interpretive framework. The proposed decision logic is as follows:

High PI and high DCI: urgent intervention package (stabilization, risk mitigation, monitoring)

High PI and low DCI: priority data completion combined with rapid risk-reduction measures

Moderate PI and high DCI: planned preventive maintenance and periodic monitoring

Low PI and low DCI: completion of inventory and evidence base

This decision matrix integrates uncertainty and evidence quality directly into the decision-making process, rather than reducing conservation priorities to a single numerical score. Such an approach provides a more rational and defensible planning framework, particularly in rapidly transforming landscapes affected by large-scale infrastructure projects (ICOMOS, 2011).

2.5.5. Output Set and Reporting Structure

The output set produced at the end of this section is standardized as follows:

Fortress-based priority ranking (PI or PI_adj)

Module-based identification of critical weaknesses (AR, TC, and MS components)

Intervention packages (urgent, medium-term, long-term)

Monitoring and preventive maintenance plans (periodicity defined by risk type)

Visual decision-support tools, including module tables, heatmaps, graphs, and mapping outputs

This study does not aim to produce a statistical prediction model. Instead, it develops a multi-criteria, semi-quantitative decision-support framework designed to inform conservation planning under conditions of uncertainty.

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained for the selected rural defensive structures in the Yusufeli region using the five-stage assessment protocol and the module-based scoring system (AR, TC, MS, DCI) (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The results are reported at two levels: (1) module-based scores that define each fortress’s profile in terms of threat exposure, contextual vulnerability, and material–intervention compatibility; and (2) the resulting priority ranking derived through normalization and aggregation procedures, accompanied by the associated data confidence levels (DCI).

3.1. Study Cases: Integrated Documentation of the Yusufeli Castles

Each fortress examined in this section is introduced through an integrated documentation panel in which field photographs, laser scanning–based surface models, and deterioration maps are read together. This visual synthesis establishes a shared reference framework for assessing the physical condition, material issues, and contextual characteristics of the structures before proceeding to quantitative evaluation and risk analysis.

Figure 3.

Integrated documentation panel of Bahçeli Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating loss of stone surface texture and plaster/mortar interventions.

Figure 3.

Integrated documentation panel of Bahçeli Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating loss of stone surface texture and plaster/mortar interventions.

The integrated documentation panel presented for Bahçeli Castle allows the simultaneous reading of the structure’s current physical condition and the traces of post-dam contextual transformation. The laser scanning–based surface model reveals the castle’s relationship with the surrounding topography and surface continuity, while field photographs document the current state of material loss, crack development, and surface deterioration. The full-elevation deterioration map further visualizes the spatial distribution of deterioration types, such as stone surface loss and plaster or mortar interventions, providing a foundational reference for the material sensitivity and risk assessments developed in subsequent sections.

The integrated documentation panel of

Çevreli (Peterek) Castle, by contrast, more explicitly demonstrates the effects of post-dam landscape transformation on the castle–valley relationship, access continuity, and surface deterioration patterns. In particular, the interaction between the castle’s topographic position and the reconfigured transportation axes, together with the observed deterioration types on stone surfaces, establishes a comparative basis for the subsequent risk and vulnerability analyses (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Integrated documentation panel of Çevreli Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating loss of stone surface texture, surface blackening, moss growth and vegetation, mortar joint erosion/loss, and moisture-related deterioration (salt crystallization, scaling, powdering).

Figure 4.

Integrated documentation panel of Çevreli Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating loss of stone surface texture, surface blackening, moss growth and vegetation, mortar joint erosion/loss, and moisture-related deterioration (salt crystallization, scaling, powdering).

The documentation panel prepared for

Kılıçkaya (Ersis) Castle enables an integrated reading of the defensive structure’s direct relationship with the bedrock and the ways in which this relationship has been transformed by post-dam microclimatic and geotechnical risks. The visual set particularly supports the interpretation of risk indicators through observed crack development, rock surface deterioration, and access fragmentation, providing an analytical basis for the subsequent assessment stages (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Integrated documentation panel of Kılıçkaya Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating cracks on stone wall surfaces, deep cracks on rock surfaces, loss of stone surface texture, plaster and mortar interventions on stone surfaces, mortar joint erosion/loss, and moisture-related deterioration (salt crystallization, scaling, powdering).

Figure 5.

Integrated documentation panel of Kılıçkaya Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating cracks on stone wall surfaces, deep cracks on rock surfaces, loss of stone surface texture, plaster and mortar interventions on stone surfaces, mortar joint erosion/loss, and moisture-related deterioration (salt crystallization, scaling, powdering).

The documentation panel of

Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni) Castle illustrates how physical deterioration, contextual disruption, and data limitations are addressed simultaneously in a case with more restricted documentation resources. This presentation provides a concrete example of why data completeness (DCI) is treated as a separate evaluative layer within the proposed model, making the implications of data gaps explicit in the assessment process (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Integrated documentation panel of Kınalıçam Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating loss of stone surface texture, plaster and mortar interventions on stone surfaces, moss growth and vegetation, deep cracks on rock surfaces, and moisture-related deterioration.

Figure 6.

Integrated documentation panel of Kınalıçam Castle showing (a) laser-scanning–derived surface model (D-RGB) and field photograph, and (b) full-façade deterioration mapping illustrating loss of stone surface texture, plaster and mortar interventions on stone surfaces, moss growth and vegetation, deep cracks on rock surfaces, and moisture-related deterioration.

The documentation panels prepared for the four castles enable a comparative reading of the impacts of the post-dam artificial reservoir landscape, reconfigured access routes, and newly imposed topographic conditions on rural defensive structures. At this stage, not only physical deterioration types, surface loss, and traces of past interventions are qualitatively identified, but also disruptions affecting visual dominance, access relationships, and landscape continuity, which are fundamental to the original defensive logic of the castles.

The visual documentation presented in this section provides a shared point of departure for the subsequent assessments of anthropogenic risk (AR), topographic–contextual vulnerability (TC), and material sensitivity (MS). In this way, numerical scores and prioritization outputs are not interpreted as abstract values, but are directly linked to observable spatial and material evidence.

3.2. Summary of Module-Based Scores (AR, TC, MS, DCI) and Comparative Logic

This subsection summarizes the scores derived from the AR, TC, MS, and DCI modules for the castles examined in the study and explains the logic of inter-module comparison. The objective is to provide a reference framework for the detailed findings presented in the following subsections and to make the composition of each castle’s “risk profile” immediately legible.

Scores are reported at two levels. The first level consists of module-based scores: AR represents a risk-based measure produced through the combination of impact and probability values for each threat type; TC reflects the translation of post-dam landscape transformation into contextual vulnerability; MS evaluates decision quality through material and intervention compatibility; and DCI indicates data completeness and the level of evidence available for each castle. The second level involves the transformation of these module scores into a single priority ranking through normalization and aggregation procedures. Accordingly, the summary table presented in

Section 3.1 is structured to facilitate the tracking of both individual module scores and the formation of the composite index.

Within this study, the TC, MS, and DCI modules are defined within a 0–1 range and are therefore directly comparable. As AR is initially scored within a 1–3 range, it is normalized to a 0–1 scale to ensure inter-module comparability. Because the MS module follows a compatibility-based logic, it is transformed into a risk-oriented variable for prioritization purposes and is expressed as 1 minus MS. This transformation prevents high compatibility scores from generating artificial urgency, while ensuring that situations involving incompatible interventions or inappropriate materials are directly reflected in the composite priority calculation.

The absence of MS data for all castles is not concealed as a limitation of the model; instead, it is explicitly rendered visible through the DCI. For this reason, the interpretation of results is based on a two-dimensional reading: PI (priority) and DCI (confidence). Where PI values are high but DCI values are low, the model indicates the need to prioritize data completion and rapid risk-reduction measures before implementing comprehensive interventions. Conversely, when both PI and DCI values are high, the model demonstrates that a sufficient analytical basis exists to proceed with defined intervention packages.

The summary table presented in this subsection comparatively illustrates the risk and vulnerability profiles of the four castles based on the AR, TC, MS, and DCI modules. In interpreting the findings, a dual-axis reading is essential: the Composite Priority Index (PI) expresses intervention urgency, while the Data Completeness Index (DCI) represents the level of evidence supporting that priority. For castles with high PI but low DCI values, data completion and immediate risk mitigation should precede extensive interventions. In contrast, where both PI and DCI are high, the model indicates that the analytical conditions required for intervention implementation have been met. The following subsection examines the first of the key components shaping the priority index, namely the anthropogenic risk module (AR), in detail for each castle.

Table 2.

Material sensitivity (MS) assessment of the castles based on documented deterioration patterns and available material analysis data.

Table 2.

Material sensitivity (MS) assessment of the castles based on documented deterioration patterns and available material analysis data.

| Castle |

Dominant deterioration types |

Dominant affected area |

Material analysis |

Critical finding |

MS interpretation |

| Bahçeli |

Salt crystallization, surface erosion |

Curtain walls |

Available |

Lime–trass mortar, high porosity |

Moderate compatibility |

| Çevreli (Peterek) |

Cracking, material disintegration |

Slope-facing elevation |

Available |

Magmatic stone, low binder compatibility |

Low compatibility |

| Kılıçkaya (Ersis) |

Biological deterioration, surface disintegration |

Upper levels |

Not available |

– |

NA |

| Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni) |

Cracking, detachment |

Slope line |

Available |

Heterogeneous aggregate, incompatible mortar |

Low compatibility |

The MS score was calculated only for castles for which laboratory-based material data were available. As no laboratory material characterization data exist for Kılıçkaya Castle, the MS module was not calculated for this case; instead, this limitation is explicitly reflected in the level of decision confidence through the DCI module.

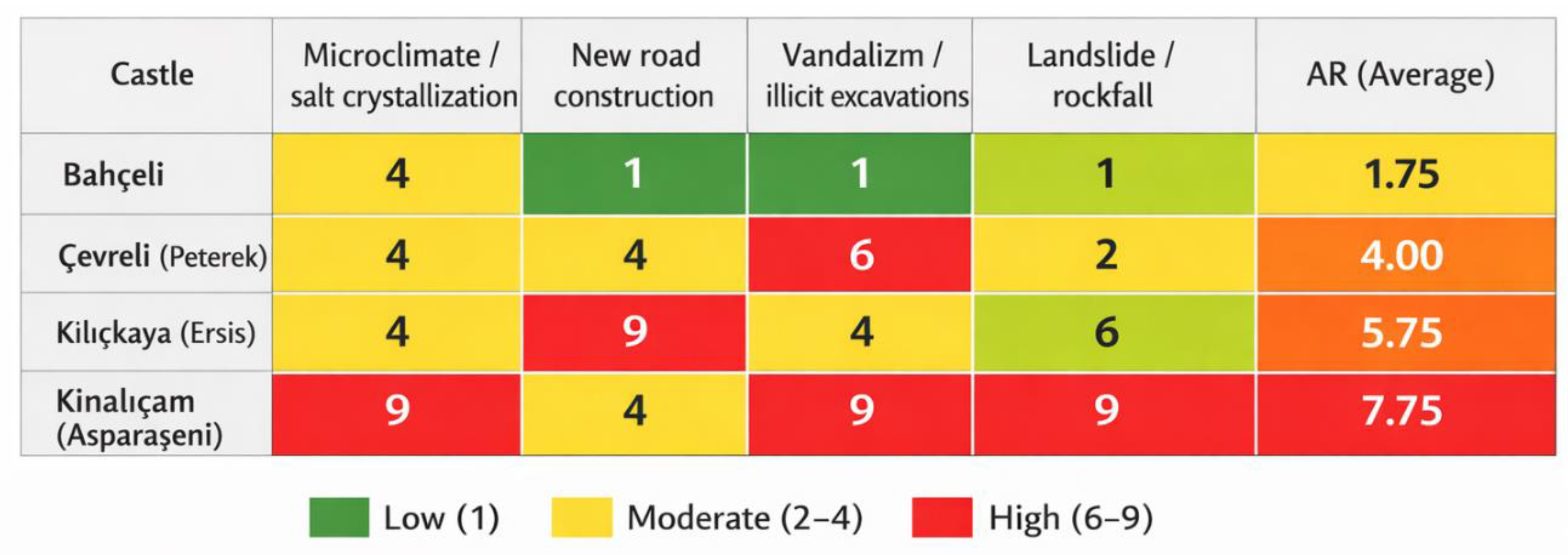

3.3. Anthropogenic Risk Module (AR): Threat Types and Site-Based Assessment

The anthropogenic risk module (AR) was developed to assess, within a comparable framework, human-induced and human-triggered threats that affect both the physical integrity and functional legibility of rural defensive structures. Within this module, risk is defined through the combined consideration of impact severity and probability of occurrence for each threat type. This approach aims to provide a holistic reading that encompasses not only existing damage conditions but also potential deterioration scenarios likely to emerge in the short and medium term.

In this study, the AR module is structured around four main threat categories:

- (A)

microclimatic processes and salt crystallization,

- (B)

new road construction and vibration effects,

- (C)

vandalism and illicit excavations, and

- (D)

geotechnical risks such as landslides and rockfall.

These threats were evaluated using deterioration and intervention maps, field observations, topographic and geomorphological readings, and transport network analyses. For each threat type, impact and probability values were defined on a 1–3 scale, and site-based risk scores were produced through the multiplication of these values, forming the basis of the AR module.

The impact and probability scores assigned within the AR module are not based on isolated or purely subjective judgments. Instead, they derive from the combined interpretation of evidence-based indicators, including documented deterioration types, field observations, topographic position, accessibility levels, and the intensity of ongoing human activities. Within this framework, scores are treated not as absolute values, but as relative indicators designed to produce a comparative risk profile among the castles within the same study area.

Table 3.

Anthropogenic risk (AR) module: threat types, impact and probability scores, and site-based AR results.

Table 3.

Anthropogenic risk (AR) module: threat types, impact and probability scores, and site-based AR results.

| Castle |

Threat type |

Impact (I) |

Probability (P) |

Risk score R = I x P |

| Bahçeli |

Microclimate / salt crystallization |

2 |

2 |

4 |

| |

New road construction / vibration |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Vandalism / illicit excavations |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| |

Landslide / rockfall |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| |

AR (mean) |

|

|

1,75 |

| Çevreli (Peterek) |

Microclimate / salt crystallization |

2 |

2 |

4 |

| |

New road construction / vibration |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

Vandalism / illicit excavations |

3 |

2 |

6 |

| |

Landslide / rockfall |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

AR (mean) |

|

|

4.00 |

| Kılıçkaya (Ersis) |

Microclimate / salt crystallization |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

New road construction / vibration |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Vandalism / illicit excavations |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

Landslide / rockfall |

3 |

2 |

6 |

|

AR (mean) |

|

|

5,75 |

| Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni) |

Microclimate / salt crystallization |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

New road construction / vibration |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

Vandalism / illicit excavations |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Landslide / rockfall |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

AR (mean) |

|

|

7,75 |

Impact (I) and Probability (P) values are defined on a scale from 1 (low) to 3 (high).

The site-based AR value is calculated as the arithmetic mean of the risk scores computed for the identified threat types.

Scores are derived from field observations, deterioration mapping, transport network analysis, and topographic assessments.

Impact and probability scores were assigned for each threat type based on indicators documented through deterioration maps, field observations, and accessibility analyses. Scoring was conducted independently by two researchers, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. To enable the quantitative comparison of anthropogenic risks, the impact and probability scores assigned to the identified threat types for each fortress were combined. The resulting AR (Anthropogenic Risk) values, calculated on the basis of field observations, deterioration mapping, and topographic and accessibility analyses, are presented below (

Figure 7).

Figure 7 presents the anthropogenic risk (AR) components and average AR scores calculated for the surveyed castles. Impact–probability–based risk scores are shown for four main threat categories: microclimate/salt crystallization, new road construction and vibration, vandalism/illegal excavations, and landslide/rockfall hazards. The colour scale represents low (1), medium (2–4), and high (6–9) risk levels. The average AR value is calculated as the arithmetic mean of the individual threat scores defined for each castle.

The anthropogenic risk profile of Bahçeli Castle is primarily shaped by microclimatic changes and salt crystallization processes. Alterations in the humidity regime caused by the dam reservoir create favourable conditions for salt crystallization on stone and mortar surfaces. However, the castle’s topographic position limits large-scale geotechnical risks at this stage. New road construction and vibration effects remain low, while vandalism-related interventions are assessed as local and largely controllable. Consequently, Bahçeli Castle exhibits a moderate AR score compared to the other case studies.

At Çevreli (Peterek) Castle, anthropogenic risks display a more pronounced and multi-layered structure. The proximity of newly developed transportation routes and increased human activity along the valley floor significantly elevate the risks of vandalism and unauthorised interventions. The concentration of such impacts documented in the deterioration maps indicates that these risks are not merely potential but already active. Although microclimatic effects are comparable to those observed at Bahçeli Castle, increased accessibility and limited control mechanisms push Çevreli Castle toward a higher overall AR profile.

For Kılıçkaya (Ersis) Castle, the anthropogenic risk assessment is largely driven by new road developments and associated vibration effects. Post-dam reconfiguration of transportation corridors has intensified heavy vehicle traffic in the immediate vicinity of the castle, contributing to crack development within masonry structures and exacerbating existing structural weaknesses. In addition, the castle’s steep, rock-based topographic setting increases exposure to rockfall and localized landslide hazards. The combined effect of these factors places Kılıçkaya Castle among the high-priority structures in terms of anthropogenic risk.

Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni) Castle emerges as one of the most critically exposed cases within the AR module. Geotechnical observations indicate an increasing risk of landslides and rockfall along the slope on which the castle is situated. These hazards are not solely the result of natural processes but are closely linked to post-dam landscape transformation and changes in land-use patterns. Furthermore, insufficient monitoring and uncontrolled human activities in the surrounding area heighten the risks of vandalism and secondary interventions. As a result, the AR module for Kınalıçam Castle identifies a critical risk condition characterized by the convergence of high-impact and high-probability threats.

Overall, the findings of the AR module demonstrate that exposure to anthropogenic threats is not homogeneous across the four castles. Instead, risk levels vary significantly depending on post-dam landscape conditions, accessibility, and topographic context. When read together with the Topographic–Contextual Vulnerability (TC) module discussed in the following subsection, these results clearly show that risk is generated not only by the physical properties of the structures themselves but also by the spatial relationships they maintain with their transformed environments.

3.4. Contextual Vulnerability Module (TC): Post-Dam Landscape Transformation and Spatial Disruptions

The contextual vulnerability module (TC) aims to evaluate the extent to which the spatial, visual, and functional relationships between rural defensive structures and their surrounding environments have weakened under post-dam landscape transformation, independently of their physical integrity. This module specifically seeks to make visible the disruptions affecting the topographic and contextual components that originally sustained the defensive logic of castles following large-scale infrastructural interventions. Within the TC framework, risk is defined not at the scale of the individual structure, but through the integrity of the structure–landscape–access network as a whole.

In this study, the TC module is operationalized through four primary indicators:

- (A)

disruption of visual dominance (V),

- (B)

breakdown of access continuity (A),

- (C)

landscape fragmentation (L), and

- (D)

microclimatic exposure (M).

These indicators are supported by topographic readings derived from laser scanning data, transportation network analyses, and systematic field observations. For each castle, normalized scores ranging between 0 and 1 were produced, enabling direct comparison across cases. The objective is to render the impact of newly formed post-dam landscape conditions on the historical siting logic and defensive function of castles discussable within a quantitative and semi-quantitative analytical framework.

At Bahçeli Castle, contextual vulnerability remains relatively limited. The castle is located outside the direct influence zone of the dam reservoir and retains much of its original valley relationships. Nevertheless, changes in microclimatic conditions and alterations in the local humidity regime are identified as contextual risk factors with the potential to affect material performance in the long term. Access continuity and visual dominance indicators largely maintain their historical coherence.

For Çevreli (Peterek) Castle, the TC module reveals a more complex vulnerability pattern. The transformation of the valley floor following the dam has weakened the castle’s historical visual relationships with its surroundings, while newly developed transportation axes have rendered original access routes secondary. As a result, although the structure remains physically intact, its legibility as a defensive installation and its capacity for spatial representation have been significantly reduced. Landscape fragmentation emerges as a dominant component shaping the TC score for Çevreli Castle.

In the case of Kılıçkaya (Ersis) Castle, contextual vulnerability is concentrated primarily in access and topographic relationship components. Post-dam reconfiguration of transportation infrastructure has fundamentally altered the modes of approach to the castle, rendering historical paths and passage systems largely obsolete. In addition, the castle’s position on steep slopes generates a contextual rupture that weakens both visual dominance and the readability of its defensive logic. These indicators collectively contribute to the high contextual vulnerability values assigned to Kılıçkaya Castle within the TC module.

Kınalıçam (Asparaşeni) Castle represents one of the most pronounced cases of contextual loss within the TC framework. The artificial lake landscape created by the dam has largely eliminated the valley relationships surrounding the castle, rendering original sightlines and defense-oriented spatial configurations ineffective. The breakdown of access continuity and severe landscape fragmentation constitute the primary drivers of increased contextual vulnerability at this site. This condition clearly demonstrates that the preservation of physical integrity alone is insufficient; the loss of contextual relationships directly undermines the cultural and historical significance of the castle.

Overall, the findings of the TC module indicate that post-dam landscape transformation should not be regarded as a secondary or indirect impact on rural defensive heritage. Instead, contextual vulnerability emerges as a fundamental component that directly shapes risk assessment and prioritization decisions. When read in conjunction with the Anthropogenic Risk (AR) module, these results underline the necessity of grounding intervention priorities not only in physical damage levels but also in spatial and functional disruptions. The following subsection examines how these spatial and environmental risks intersect with material performance and intervention compatibility within the Material Sensitivity and Intervention Compatibility module (MS).

3.5. Material–Intervention Compatibility Module (MS): Evaluation of Original Material Characteristics and Intervention Decisions

The Material–Intervention Compatibility module (MS) aims to assess the degree to which implemented or proposed conservation interventions in rural defensive structures are compatible with the original building materials. Within this module, compatibility is not evaluated solely through the physical or chemical properties of materials, but rather through the relationship established between intervention decisions and the original construction logic in terms of permeability, durability, and material behavior. The primary objective of the MS module is to make visible those incompatible interventions that may appear “strengthening” in the short term but are likely to trigger secondary risks such as moisture accumulation, salt crystallization, and surface loss over the long term.

In this study, the MS assessment was conducted through an integrated reading of laboratory-based material analyses (mortar and stone samples), field observations, and available documentation related to past or proposed interventions (

Figure 8). Petrographic and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses carried out on mortar and stone samples revealed the binder–aggregate relationships, mineralogical composition, and potential deterioration mechanisms of the original materials. These findings were subsequently used as reference criteria for evaluating the compatibility of materials employed or proposed in conservation interventions with the original fabric.

In mortar characterization, technical literature particularly emphasizes the importance of a holistic interpretive approach based on the combined evaluation of multiple analytical methods rather than reliance on isolated test outputs (RILEM TC 203-RHM, 2009). Accordingly, the MS module adopts an integrated assessment logic in which laboratory results are not treated as ends in themselves but are translated into decision-oriented indicators directly linked to intervention suitability and long-term material performance.

Figure 8.

Sample pages from the material analysis report of a mortar specimen taken from Bahçeli Castle: (a) macroscopic appearance and textural description of the mortar sample within the scope of sampling and visual assessment; (b) chemical/ionic analysis table of the same sample with a brief interpretive note addressing binder–aggregate relationships, porosity, and indicators of contamination and salt-related processes.

Figure 8.

Sample pages from the material analysis report of a mortar specimen taken from Bahçeli Castle: (a) macroscopic appearance and textural description of the mortar sample within the scope of sampling and visual assessment; (b) chemical/ionic analysis table of the same sample with a brief interpretive note addressing binder–aggregate relationships, porosity, and indicators of contamination and salt-related processes.

These report pages are presented as illustrative examples to demonstrate the evidence base underlying the fields “analysis available/not available,” “critical finding,” and “MS interpretation” transferred to the MS module in

Table 4. The experimental and documentary data enable the combined evaluation of dominant deterioration types, availability of analytical data, and intervention compatibility for each castle. The table presented below clearly distinguishes between cases with and without material analyses, thereby summarizing in a comparative manner the level of evidence on which MS module interpretations are based (

Table 4).

At Bahçeli Castle, material analysis results indicate that the original mortar system is lime-based, with a relatively balanced aggregate distribution. When evaluated together with field observations and existing intervention records, the proposed or implemented interventions appear largely compatible with this material character. In particular, no excessive stress on the original fabric is observed in terms of vapor permeability or mechanical behavior. Accordingly, the MS findings for Bahçeli Castle indicate a high level of material–intervention compatibility.

At Çevreli (Peterek) Castle, laboratory analyses confirm that the original material system is predominantly lime-based. However, field observations reveal that in certain areas harder and less permeable repair mortars have been used. While such interventions may enhance the perception of stability in the short term, they carry a potential incompatibility risk that may increase moisture accumulation and salt crystallization over the long term. For this reason, the MS assessment for Çevreli Castle is interpreted as indicating a moderate level of compatibility.

At Kınalıçam (Asparaseni) Castle, material analyses demonstrate that the original fabric exhibits a heterogeneous character and a sensitive balance with respect to environmental conditions. When interpreted together with field data, it becomes evident that the material choices adopted in proposed or locally implemented interventions do not sufficiently respect this fragile balance. In particular, incompatibility risks related to binder stiffness and vapor permeability are identified. Consequently, the MS module yields a low compatibility assessment for Kınalıçam Castle.

For Kılıçkaya (Ersis) Castle, the absence of laboratory-based material analyses limits the quantitative calculation of the MS module. This data gap has not been concealed within the model; on the contrary, it has been explicitly rendered visible through the Data Completeness Index (DCI). Accordingly, the assessment of intervention compatibility for Kılıçkaya Castle is restricted to qualitative field observations, and the absence of a quantitative MS score is maintained as a deliberate choice in favor of methodological transparency.

Overall, the findings of the MS module demonstrate that material compatibility is not merely a technical detail but a critical component that directly influences risk assessment and prioritization decisions. In particular, in cases where anthropogenic risk (AR) and contextual vulnerability (TC) are high, incompatible interventions may amplify existing risks through a multiplier effect. For this reason, the MS module should be interpreted as a complementary assessment domain that must be read in conjunction with AR and TC. In the following subsection, the uncertainty dimension and evidential robustness of these assessments are addressed through the Data Completeness Index (DCI).

3.6. Data Completeness and Uncertainty Dimension (DCI): Reliability of Results and Definition of Decision Boundaries

The Data Completeness Index (DCI) has been developed to explicitly demonstrate the level of evidence on which the results of the proposed assessment model are based. Rather than presenting risk and priority scores as absolute truths, the primary function of the DCI is to make visible the extent to which these scores are supported by documentation, analysis, and measurement data. In this way, the model moves beyond a tool that merely produces priority rankings and is transformed into a decision-support framework capable of managing uncertainty.

The DCI module is calculated by considering both the scope and the quality of the datasets available for each castle. Key determinants include the availability of laser scanning data, the completeness of survey drawings and deterioration maps, the presence of topographic modeling outputs, and the existence of laboratory-based material analyses. Each data type is weighted according to its contribution to decision-making, and the resulting DCI values are defined within a 0–1 range, allowing direct comparison with the other modules.

For Bahçeli Castle, the DCI value indicates a high level of data completeness. The combined availability of laser scanning data, detailed deterioration maps, and laboratory-based material analyses demonstrates that the AR, TC, and MS scores produced for this castle are grounded in a strong evidential basis. This condition suggests that the proposed intervention strategies and priority decisions for Bahçeli Castle can be approached with a relatively high degree of confidence.

At Çevreli (Peterek) Castle, data completeness is also generally high. However, the more limited scope of certain material and intervention-related datasets has resulted in a slightly lower DCI value compared to Bahçeli. Nevertheless, sufficient data are available to robustly support the primary risk and contextual vulnerability indicators, allowing the prioritization outcomes for Çevreli Castle to be interpreted within a reliable analytical framework.

For Kınalıçam (Asparaseni) Castle, the DCI indicates a moderate level of data completeness. While spatial datasets such as laser scanning outputs and deterioration maps are available, the limited extent of material characterization analyses requires that results derived from the MS module be interpreted with caution. When read together with the high risk and vulnerability values identified for this castle, this condition highlights the importance of targeted data completion efforts prior to the implementation of major interventions.

Kılıçkaya (Ersis) Castle emerges as the case with the lowest data completeness within the DCI module. Although laser scanning data and deterioration maps are available, the absence of laboratory-based material analyses has constrained the quantitative calculation of the MS module. This limitation has not been concealed within the model; on the contrary, it has been explicitly articulated through the DCI. This approach indicates that the priority scores produced for Kılıçkaya Castle must be interpreted under conditions of high uncertainty.

Overall, the findings of the DCI module demonstrate that data gaps do not constitute a weakness of the model. On the contrary, when explicitly acknowledged and systematically managed, they contribute to a more transparent and responsible decision-making process. Within this framework, castles exhibiting high Priority Index (PI) values but low DCI values should not be subject to immediate large-scale interventions. Instead, priority should be given to data completion efforts accompanied by rapid risk mitigation strategies. In the following subsection, the results derived from the AR, TC, MS, and DCI modules are brought together to present an integrated evaluation based on the composite priority index and decision classes.

3.7. Synthesis of the Composite Priority Index (PI) and Decision Classes

In this subsection, the outputs derived from the Anthropogenic Risk (AR), Contextual Vulnerability (TC), Material–Intervention Compatibility (MS), and Data Completeness (DCI) modules are integrated to produce a Composite Priority Index (PI) for each castle. The PI aims to consolidate heterogeneous risk and vulnerability components within a common evaluative scale, allowing conservation and intervention decisions to be addressed on a comparable and transparent basis. By moving beyond intuitive judgments based on isolated risk indicators, this approach provides a multi-criteria and reproducible prioritization framework.

In the calculation of the PI, AR values are normalized to the 0–1 range, while TC and MS are used directly as comparable scores. Because the MS module is structured around a logic of compatibility rather than risk, its values are inverted (1 − MS) so that incompatibility is incorporated as a risk component in the composite index. The DCI is not included as a direct component of the PI; instead, it is treated as a second analytical axis in the interpretation of results, allowing the relationship between priority and confidence level to be explicitly articulated.

The synthesis clearly demonstrates that the priority profiles of the four castles differ markedly. Kınalıçam (Asparaseni) Castle emerges as the structure with the highest priority level, due to the combination of high AR and TC values, low MS compatibility, and a moderate DCI score. This configuration indicates both the urgency of risks affecting the site and the need for carefully structured intervention decisions. In particular, contextual ruptures and geotechnical risks elevate Kınalıçam Castle to the upper ranks of the intervention agenda.

Kılıçkaya (Ersis) Castle occupies a distinct decision category. Although it exhibits high anthropogenic risk and contextual vulnerability values, its low DCI places it in a different class of action. While the PI for Kılıçkaya is high, limited data completeness necessitates prioritizing targeted documentation and data completion efforts before undertaking comprehensive interventions. This outcome demonstrates that the model addresses not only the question of which structures are at risk, but also what type of action is appropriate for each case.

Çevreli (Peterek) Castle is positioned within the planned intervention category, characterized by medium-to-high AR and TC values, moderate MS compatibility, and a relatively high DCI. For this site, the recommended approach favors phased and monitorable conservation strategies aligned with clearly defined priorities, rather than immediate large-scale interventions. The case of Çevreli Castle clearly illustrates that contextual vulnerability can influence prioritization decisions independently of the degree of visible physical damage.

Bahçeli Castle, by contrast, is identified as the site with the lowest priority level, based on relatively low AR and TC values, high MS compatibility, and a high DCI score. These results indicate that, rather than requiring urgent intervention, Bahçeli Castle can be effectively managed through monitoring and preventive maintenance strategies. This case is particularly significant in demonstrating that the model is capable of distinguishing not only high-risk structures, but also heritage assets that remain relatively stable under post-dam conditions.

When PI and DCI are considered together, the model produces four primary decision classes: (1) structures requiring urgent intervention, (2) structures requiring planned intervention, (3) structures prioritizing data completion, and (4) structures suited to monitoring-oriented management. This classification enables the transparent and justifiable allocation of limited conservation resources within the context of rural defensive heritage. Accordingly, the proposed model functions not only as an analytical assessment tool, but also as an operational decision-support system.

The findings presented in this section demonstrate that the conservation of rural defensive structures under post-dam transformation pressures requires the integrated evaluation of multi-dimensional risk and vulnerability components, rather than reliance on isolated damage indicators. In the following section, these results are discussed in relation to the existing conservation literature and comparable studies, with particular attention to the model’s contributions, limitations, and potential transferability to other geographic contexts.

4. Dıscussıon

This section discusses the findings and the proposed evaluation model in relation to the existing literature on risk-based conservation, contextual vulnerability, and decision-support approaches.

4.1. Comparison with the Literature: Risk, Context, and Decision-Support Approaches

Approaches to risk assessment and conservation prioritization in cultural heritage studies have traditionally been developed primarily around measurable physical parameters, such as structural damage, material decay, and natural hazards. Engineering-based vulnerability models, in particular, have enabled the quantitative definition of risk through numerical indicators. However, the majority of these models treat the spatial relationships between heritage structures and their surroundings, as well as their representational and contextual values, as secondary or auxiliary dimensions. As a result, heritage structures that remain physically standing but experience significant degradation of their topographic, visual, or functional context are often insufficiently represented within existing risk profiles.

The multi-modular assessment model proposed in this study seeks to extend these limitations in the literature at two principal levels. First, anthropogenic risks are addressed not merely as qualitative threat descriptions, but within a structured risk framework based on the combined evaluation of impact and likelihood. This approach provides a more comparable and decision-oriented basis for prioritization, particularly in rural defensive heritage contexts where environmental and human-induced pressures operate simultaneously. Second, the definition of contextual vulnerability (TC) as an independent module makes it possible to identify risk profiles for structures whose physical integrity is largely preserved, yet whose topographic, visual, and functional relationships have been substantially disrupted.

In much of the existing conservation literature, contextual evaluations remain largely confined to qualitative descriptions. Relationships involving topography, access, and landscape are rarely integrated into systematic quantitative or semi-quantitative models. The TC module developed in this study aims to address this gap by operationalizing contextual vulnerability through laser-scanning data, topographic readings, and access analyses. In doing so, context is no longer treated as an abstract or interpretive concept, but rather as a measurable assessment component that directly informs intervention priorities. In recent years, the limitations of purely fabric-focused approaches have become increasingly evident, particularly with the growing emphasis on cultural landscape, context, and indirect impacts within international conservation discourse (UNESCO, 2011; ICOMOS, 2011).

Similarly, the inclusion of material–intervention compatibility (MS) within the risk framework enables the evaluation of long-term consequences associated with interventions that may appear technically effective in the short term but are materially incompatible with the original fabric. While material analyses in the literature are often presented as descriptive technical datasets, this study differentiates itself by directly integrating such analyses into prioritization and decision-making processes. The Data Completeness Index (DCI), in turn, is proposed as a complementary tool that explicitly communicates uncertainty rather than concealing it, making the evidential basis of assessment results transparent.

In this respect, the study does not seek to reject existing risk and vulnerability frameworks, but rather to complement them through a contextual and epistemic expansion. The proposed model is particularly oriented toward rural landscapes undergoing rapid transformation following large-scale infrastructure projects. It addresses not only the question of how damaged a heritage structure is, but also which knowledge base supports its assessment, with what level of priority, and through which level of intervention it should be addressed.

4.2. Contributions and Distinctive Features of the Proposed Model

The evaluation model proposed in this study contributes to existing approaches for the conservation of rural defensive heritage at three principal levels: (1) the redefinition of risk within a multi-dimensional and contextual framework, (2) the explicit and auditable integration of data uncertainty into the assessment process, and (3) the translation of analytical results into action-oriented decision categories. Unlike conventional risk-based assessment approaches, the model deliberately separates intervention priority from evidential confidence, allowing risk ranking and decision reliability to be examined simultaneously but along distinct analytical axes.