Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

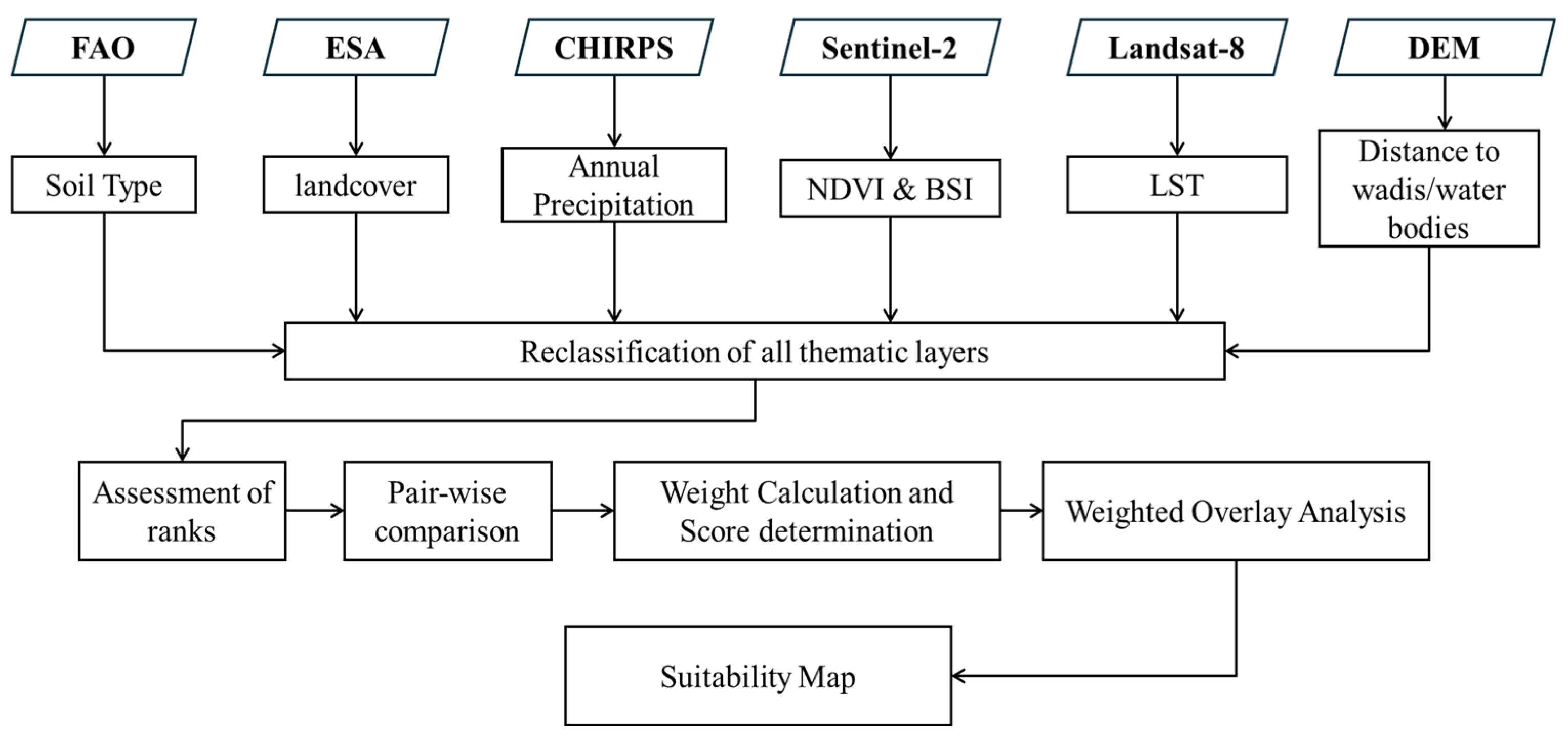

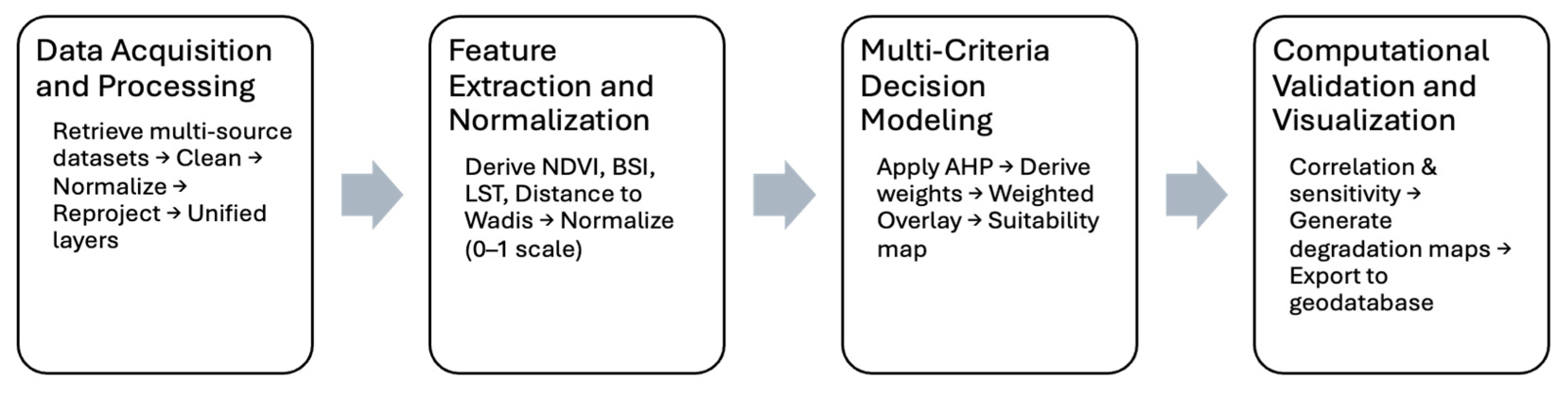

- Derive key environmental indicators (NDVI, BSI, LST, Distance to Water/Wadis, Soil type, precipitation, and climate variables) from multispectral and thermal satellite imagery and open-source datasets;

- Integrate and normalize these indicators within a modular computational workflow using AHP-based decision modeling to assess their relative influence on degradation; and

- Generate and validate degradation-susceptibility maps delineating areas of high, moderate, and low environmental suitability for restoration.

2. Related Work

2.1. Remote Sensing and Environmental Indicators

2.2. Geospatial Modeling and Data Integration

2.3. Multi-Criteria Decision Algorithms

2.4. Computational Sustainability Frameworks

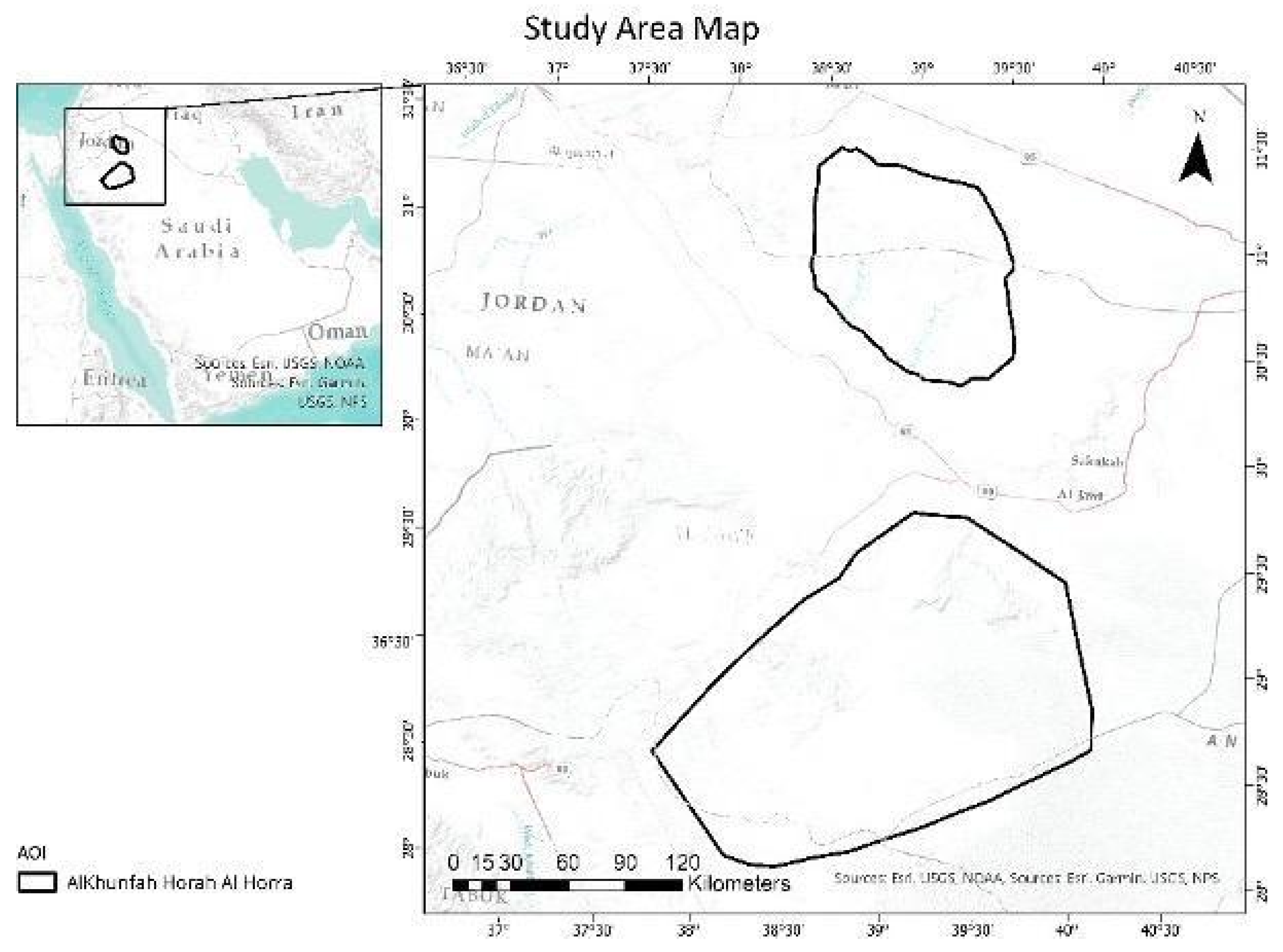

3. Study Area and Data

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Environmental Variables

- NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index): Quantifies vegetation vigor and canopy density, enabling detection of healthy versus degraded areas.

- BSI (Bare Soil Index): Highlights soil exposure and erosion-prone surfaces associated with vegetation decline.

- LST (Land Surface Temperature): Indicates surface heat stress, which strongly correlates with vegetation loss in arid climates.

- Precipitation: Represents annual rainfall variability as a proxy for water availability and drought intensity.

- Soil Type: Defines textural and fertility differences that affect root stability and plant productivity.

- Land Cover: Describes spatial distribution of vegetation, bare ground, and anthropogenic surfaces.

- Distance to Wadis: Measures proximity to ephemeral water channels that enhance soil moisture and promote localized vegetation growth.

3.4. Data Preprocessing and Computational Environment

4. Computational Sustainability Framework

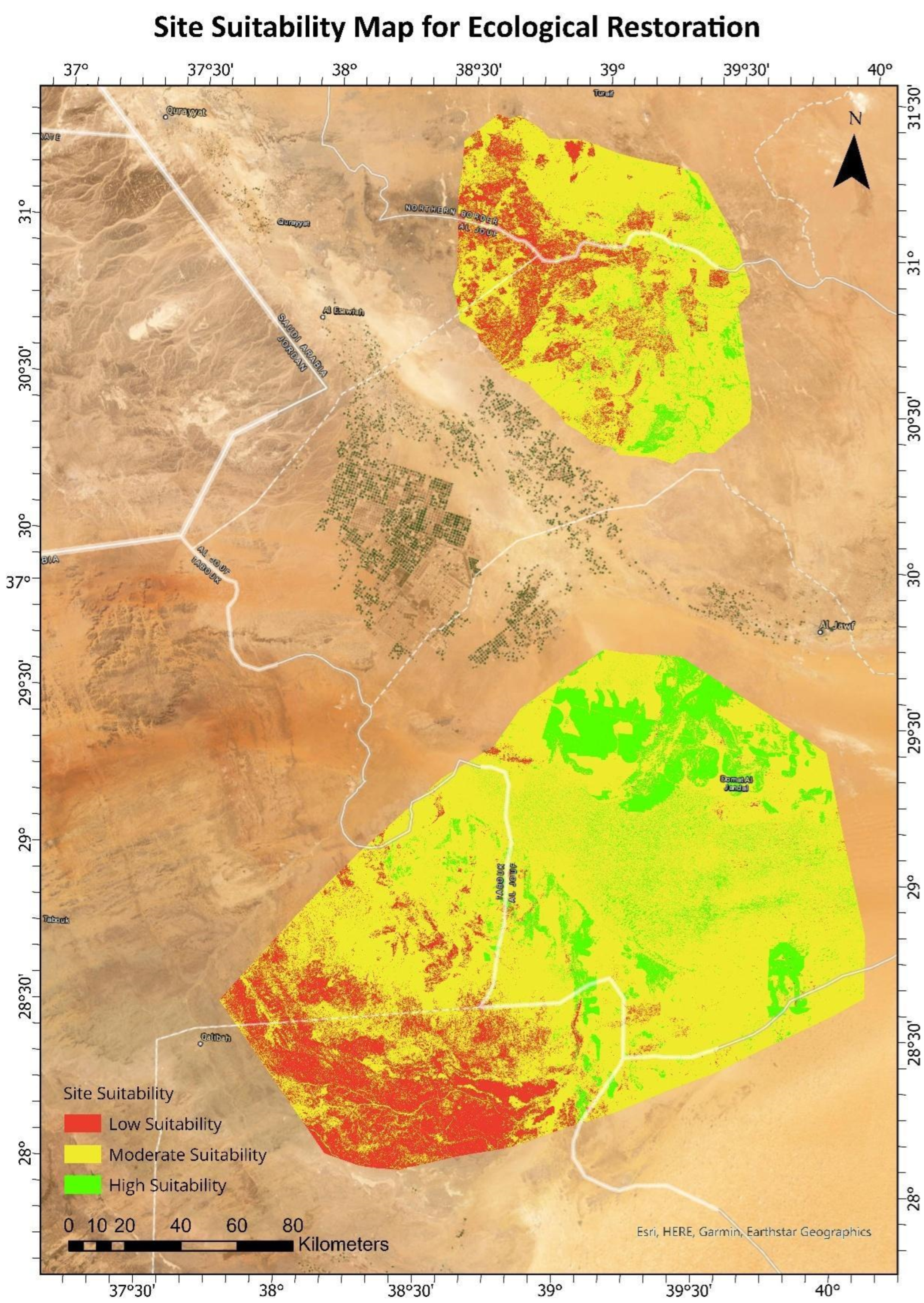

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Overview of Computational Implementation

5.2. Spatial and Analytical Results

| Criteria | NDVI | BSI | LST | Soil Type | Distance to Wadis | Climate Observation | Landcover |

| NDVI | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| BSI | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| LST | 0.33 | 0.20 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Soil Type | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Distance to Wadis | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Climate Observation | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Landcover | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 1 |

| Criteria | Weight (%) | Rank | Sub-Criterion | Score |

|

BSI (value) |

33.6 |

1 |

< 0.177 | 3 |

| 0.178 – 0.275 | 2 | |||

| > 0.276 | 1 | |||

|

NDVI (value) |

29.1 |

2 | < 0.079 | 1 |

| 0.08 – 0.116 | 2 | |||

| > 0.117 | 3 | |||

|

LST () |

15.9 |

3 |

< 45 | 3 |

| 45-49 | 2 | |||

| > 49 | 1 | |||

| Soil Type (Class) |

7.3 |

4 |

Sandy | 1 |

| Calcareous | 3 | |||

| Loamy / alluvial | 3 | |||

| Gravelly / Shallow rocky | 1 | |||

| Clayey | 2 | |||

| Distance to Wadis (meter) |

6.7 |

5 |

< 1000 | 3 |

| 1000 – 3000 | 2 | |||

| > 3000 | 1 | |||

| Climate Observation (mm) |

5.2 |

6 |

< 100 | 3 |

| 100 – 150 | 2 | |||

| > 150 | 1 | |||

|

Landcover (class) |

2.2 |

7 |

Tree Cover | 3 |

| Shrubland | 3 | |||

| Grassland | 2 | |||

| Cropland | 2 | |||

| Built-Up | 1 | |||

| Bare/sparse vegetation | 1 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

References

- D’Odorico, P.; Bhattachan, A.; Davis, K.F.; Ravi, S.; Runyan, C.W. Global Desertification: Drivers and Feedbacks. Advances in Water Resources 2013, 51, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.K.; Magle, S.B.; Gallo, T. Global Trends in Urban Wildlife Ecology and Conservation. Biological Conservation 2021, 261, 109236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, O.H.; Masrahi, Y.S. Climatology and Phytogeography of Saudi Arabia: A Review. Arid Land Research and Management 2023, 37, 311–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, M. Evaluation of Different Soil Salinity Mapping Using Remote Sensing Techniques in Arid Ecosystems, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Sensors 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouari, W. Assessment of Vegetation Cover Changes and the Contributing Factors in the Al-Ahsa Oasis Using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). Regional Sustainability 2024, 5, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Alharbi, O.A.; Alqurashi, A.F.; Fahil, A.S. Assessment of Desertification Dynamics in Arid Coastal Areas by Integrating Remote Sensing Data and Statistical Techniques. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagoub, M.M.; AlSumaiti, T.; Tesfaldet, Y.T.; AlArfati, K.; Alraeesi, M.; Alketbi, M.E. Integration of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Remote Sensing to Assess Threats to Preservation of the Oases: Case of Al Ain, UAE. Land 2023, 12, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.; Dietterich, T.; Barrett, C.; Conrad, J.; Dilkina, B.; Ermon, S.; Fang, F.; Farnsworth, A.; Fern, A.; Fern, X.; et al. Computational Sustainability: Computing for a Better World and a Sustainable Future. Commun. ACM 2019, 62, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N. Chr. Using the Satellite-Derived NDVI to Assess Ecological Responses to Environmental Change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, J.A.; Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Paolini, L. Land Surface Temperature Retrieval from LANDSAT TM 5. Remote Sensing of Environment 2004, 90, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, F.; Azarnivand, H.; Khosravi, H.; Zehtabian, G.; Sigaroudi, S.K. Monitoring the Severity of Degradation and Desertification by Remote Sensing (Case Study: Hamoun International Wetland). Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 902687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, Y.; He, L.; He, Z.; Luo, F.; Zhao, Y.; Gan, J.; Bai, W.; Chen, X. Improving Remote Sensing Ecological Assessment in Arid Regions: Dual-Index Framework for Capturing Heterogeneous Environmental Dynamics in the Tarim Basin. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Dimobe, K.; Serme, I.; Tondoh, J.E. Landsat-8 vs. Sentinel-2: Examining the Added Value of Sentinel-2’s Red-Edge Bands to Land-Use and Land-Cover Mapping in Burkina Faso. GIScience & Remote Sensing 2018, 55, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdyyev, A.; Al-Masnay, Y.A.; Juliev, M.; Abuduwaili, J. Desertification Monitoring Using Machine Learning Techniques with Multiple Indicators Derived from Sentinel-2 in Turkmenistan. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmy, O.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hemmler, K.S.; Loulad, S.; Rhinane, H.; Buerkert, A. Leveraging Machine Learning and Landsat Time Series for High-Resolution Mapping of Mining-Induced Vegetation Changes in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Environmental Challenges 2024, 17, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J. GIS-based Multicriteria Decision Analysis: A Survey of the Literature. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2006, 20, 703–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldasbayeva, D.; Tregubova, P.; Gasanov, M.; Zaytsev, A.; Petrovskaia, A.; Burnaev, E. Challenges in Data-Driven Geospatial Modeling for Environmental Research and Practice. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic Hierarchy Process. In Encyclopedia of operations research and management science; Springer, 2013; pp. 52–64.

- Moradi, E.; Khosravi, H.; Rahimabadi, P.D.; Choubin, B.; Muchová, Z. Integrated Approach to Land Degradation Risk Assessment in Arid and Semi-Arid Ecosystems: Applying SVM and eDPSIR/ANP Methods. Ecological Indicators 2024, 169, 112947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Wildlife (NCW) Annual Report 2023; National Center for Wildlife: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023.

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) The Saudi Green Initiative: Facts and Perspectives. Al-Ensaneyyat Periodical.

- Salomon, V.A.P.; Gomes, L.F.A.M. Consistency Improvement in the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Mathematics 2024, 12, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, E.; Sapio, S.; Schiavon, E.; Righini, M.; Monteleone, B.; Taramelli, A. Development of a Pre-Automatized Processing Chain for Agricultural Monitoring Using a Multi-Sensor and Multi-Temporal Approach. Land 2024, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Data Source | Resolution / Purpose |

| Spectral Indices (NDVI, BSI) | Sentinel-2 MSI | 10–20 m; Vegetation greenness and soil exposure analysis |

| Land Surface Temperature (LST) | Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS | 30 m; Surface heat and thermal stress mapping |

| Precipitation | CHIRPS v2.0 | 0.05° (~5 km); Long-term rainfall pattern analysis |

| Soil Type | FAO Soil Map of the World | 1:5,000,000; Soil classification and fertility assessment |

| Land Cover | ESA CCI Land Cover | 300 m; Vegetation and land-use categorization |

| Topography / Distance to Wadis | SRTM DEM (30 m) | Elevation, slope, and hydrological modeling |

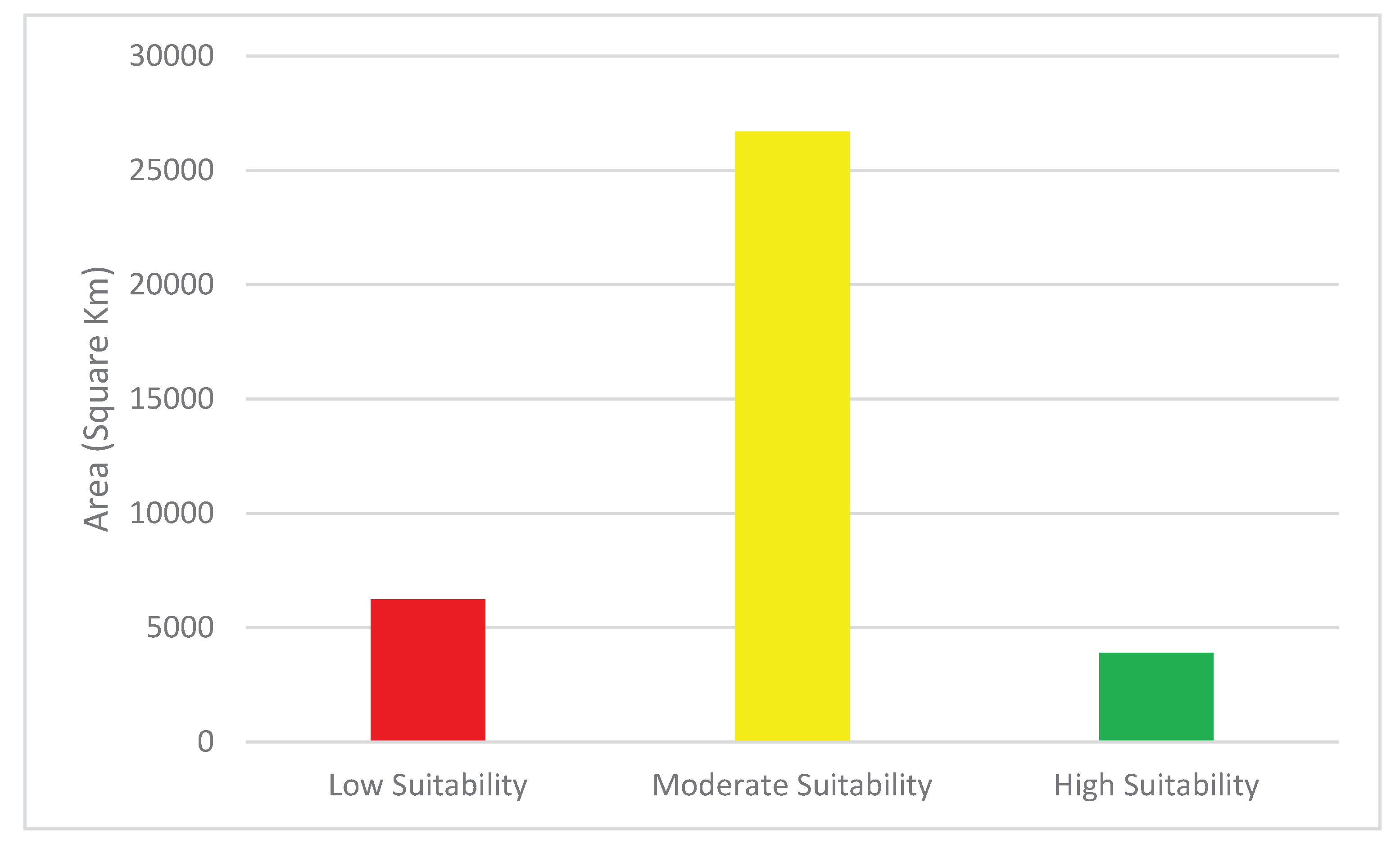

| Suitability Class | Description |

| High Suitability | Areas with dense and healthy vegetation cover, low BSI, moderate LST, and close proximity to water sources. |

| Moderate Suitability | Transitional landscapes where vegetation cover is partially degraded but retains ecological potential. |

| Low Suitability | Areas showing severe vegetation degradation, soil exposure, and high desertification risk. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).