1. Introduction

3-Amino-4-hydroxybenzoic acid (3,4-AHBA) is an important non-proteinogenic aromatic compound that serves as a key biosynthetic precursor for a variety of secondary metabolites, including antibiotics, pigments, and pharmaceutically relevant aromatic derivatives. Owing to its chemical structure, 3,4-AHBA is considered a valuable building block for the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Conventional chemical synthesis of aromatic amines often relies on petroleum-derived substrates and harsh reaction conditions, thereby motivating the development of sustainable microbial production routes.

Metabolic engineering of microorganisms provides a promising alternative for the biosynthesis of aromatic precursors such as 3,4-AHBA. However, rational improvement of production yields remains challenging due to the intrinsic complexity of cellular metabolism. Central carbon metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, cofactor balancing, and growth-associated energy demands are tightly interconnected, such that targeted genetic modifications frequently result in unexpected system-wide metabolic responses. Consequently, experimental trial-and-error approaches alone are often costly, time-consuming, and insufficient to fully capture these global effects.

Genome-scale metabolic (GSM) modeling has emerged as a powerful framework to address these challenges. In a GSM model, also referred to as a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM), the complete set of metabolic reactions encoded in a genome is reconstructed into a stoichiometric network that enables quantitative analysis of intracellular metabolism [

1,

2]. When combined with constraint-based optimization methods such as flux balance analysis (FBA), GEMs allow prediction of intracellular flux distributions under defined environmental and genetic conditions. A central component of these models is the biomass equation, which links metabolic fluxes to cellular growth by accounting for the synthesis of macromolecular components—including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates—as well as cellular maintenance energy requirements [

3,

4,

5]. Through this formulation, GEMs provide a mechanistic and quantitative bridge between genotype, phenotype, and metabolic fluxes.

Constraint-based modeling has been successfully applied to guide strain design and bioprocess optimization in a wide range of microorganisms. In silico simulations have enabled identification of metabolic bottlenecks, prediction of gene deletion or insertion targets, and redirection of carbon fluxes toward desired products, including industrial chemicals such as 2,3-butanediol and 3-hydroxypropionic acid [

2,

6]. These studies demonstrate that GEM-based approaches can substantially reduce experimental workload while providing system-level insight into metabolic regulation

Actinomycetes are particularly attractive hosts to produce specialized metabolites due to their rich secondary metabolism and industrial robustness. Members of the genus

Streptomyces are aerobic, filamentous, Gram-positive bacteria well known for their ability to synthesize diverse bioactive compounds [

7,

8,

9]. Among them,

S. thermoviolaceus exhibits several advantageous traits, including relatively rapid growth, secretion of extracellular enzymes, and tolerance across a broad temperature range (28–55 °C), with an optimal growth temperature of approximately 45 °C [

10]. These properties make

S. thermoviolaceus a promising but still underexploited host for metabolic engineering. To date, however, its application has been limited by the availability of tailored genetic tools and quantitative metabolic models.

In this study, we combined genome-scale metabolic modeling and flux balance analysis with targeted genetic engineering to investigate and enhance 3,4-AHBA production in S. thermoviolaceus. Specifically, we introduced the nspH–nspI gene operon, which enables conversion of aspartate-derived intermediates toward 3,4-AHBA biosynthesis. Using FBA, we analyzed how this genetic intervention alters central carbon metabolism, redistributes intracellular fluxes, and affects cofactor usage and growth-associated trade-offs. Model predictions were subsequently validated by comparing growth behavior, glucose uptake rates, and 3,4-AHBA production between the wild-type and engineered strains.

By integrating in silico flux analysis with experimental cultivation data, this work provides a system-level understanding of the metabolic rewiring underlying 3,4-AHBA biosynthesis in S. thermoviolaceus. The results highlight key metabolic nodes controlling aromatic precursor production and demonstrate the utility of GSM-based strategies for rational strain design in non-model actinomycetes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains, Plasmids, and Enzymes

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in

Table 1.

S. thermoviolaceus NBRC 13905 was obtained from the NITE Biological Resource Center (NBRC), Tokyo, Japan (

https://www.nite.go.jp/en/). The strain was routinely maintained in tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium containing pancreatic digest of casein (17 g L⁻¹), papaic digest of soybean meal (3 g L⁻¹), glucose (2.5 g L⁻¹), sodium chloride (5 g L⁻¹), and dipotassium phosphate (2.5 g L⁻¹) (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA). For solid media, agar was added at a final concentration of 20 g L⁻¹. Apramycin was used as a selective antibiotic at 50 μg mL⁻¹ as required. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). The In-Fusion HD cloning kit was obtained from TaKaRa Bio Inc. (Shiga, Japan) and used for DNA fragment assembly. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to verify insertion of the

nspH–nspI gene operon and deletion of the creL gene in

S. thermoviolaceus using the high-fidelity DNA polymerase KOD FX (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan).

2.2. Plasmid Construction

The expression plasmid for 3,4-AHBA production was constructed by assembling the ermE promoter, the pld terminator, and the nspH–nspI gene operon. The ermE promoter and pld terminator fragments were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The primers used for amplification of the promoter were ermEp-MCS_Fw and ermEp-MCS-PLDt_Rv, while the terminator fragment was amplified using PLDt_Fw and PLDt_Rv.

The amplified promoter and terminator fragments, each containing 20-bp overlapping sequences, were inserted into the pTYM18 plasmid digested with

HindIII and

EcoRI using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), resulting in the intermediate plasmid pTYM18-ermE-pldT. Subsequently, the

nspH–nspI gene operon was amplified from S. maruyamaensis genomic DNA using primers NspHI-tandem1-Hind3-Fw and NspHI-tandem2-Xba1-Rv. The amplified

nspH–nspI fragment was inserted into the pTYM18-ermE-pldT plasmid, digested with

XbaI, yielding the final expression plasmid pTYM18-ermE-

nspH-nspI (Figure 2A). A complete list of primers used in this study is provided in

Table 2.

2.3. Preparation of Transformant Strains

Transformant strains of S. thermoviolaceus were obtained by intergeneric conjugation, in which plasmids were transferred from E. coli to S. thermoviolaceus. The constructed plasmid pTYM18-ermE-nspH–nspI, which carries the genes required for 3,4-AHBA production, was first introduced into E. coli HST04. Subsequently, the helper plasmid pUB307, which provides the transfer (tra) functions, was transferred from E. coli JM109 into E. coli HST04 harboring the expression plasmid.

Spores of S. thermoviolaceus were mixed with the donor E. coli HST04 strain carrying both plasmids and spread onto ISP4 agar plates containing soluble starch (10 g L⁻¹), K₂HPO₄ (1 g L⁻¹), MgSO₄·7H₂O (1 g L⁻¹), NaCl (1 g L⁻¹), (NH₄)₂SO₄ (2 g L⁻¹), and CaCO₃ (2 g L⁻¹), supplemented with 1 mL of trace element solution (FeSO₄·7H₂O, 0.1 g per 100 mL; MnCl₂·4H₂O, 0.1 g per 100 mL; ZnSO₄·7H₂O, 0.1 g per 100 mL). Plates were incubated at 45 °C for 18–24 h to allow conjugation.

After incubation, 3 mL of sterile distilled water containing apramycin (50 μg mL⁻¹) and nalidixic acid (50 μg mL⁻¹) was overlaid onto each plate to eliminate residual E. coli cells. Putative recombinant S. thermoviolaceus colonies were subsequently transferred to selective TSB agar plates supplemented with apramycin (50 μg mL⁻¹) and incubated at 45 °C for further analysis.

2.4. Fermentation and 3.4-AHBA Analysis

Recombinant S. thermoviolaceus strains were pre-cultured in 10 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB) at 45 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, 2 mL of the pre-culture was inoculated into 200 mL of nutrient minimal medium for production (NMMP) in a baffled 500 mL shaking flask. The NMMP medium consisted of (NH₄)₂SO₄ (2 g L⁻¹), Casamino acids (5 g L⁻¹), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.6 g L⁻¹), polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000; 50 g L⁻¹), minor elements solution (1 g L⁻¹), glucose (25 g L⁻¹), and 15 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) prepared in distilled water. Cultivation was performed at 45 °C with shaking at 160 rpm for 120 h. All fermentation experiments were conducted in triplicate.

For analysis of 3,4-AHBA production, culture samples (20 mL) were collected at designated time intervals and centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min at 25 °C. The resulting supernatants were used to analyze residual glucose and 3,4-AHBA concentrations. Quantification of 3,4-AHBA was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Shimadzu LC-20A system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a COSMOSIL HILIC column (4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) and a diode array detector (SPD-20AV; Shimadzu). The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C, and the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at a 65:35 (v/v) ratio, with a flow rate of 1.0 mL min⁻¹. The concentration of 3,4-AHBA was determined using calibration curves generated from authentic standards, as described previously [

12].

Glucose concentrations were quantified by HPLC using the same LC-20A system equipped with a COSMOSIL Sugar-D column (4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm; Nacalai Tesque) and a refractive index detector (RID-10A; Shimadzu). The column temperature was set to 30 °C, and the mobile phase consisted of 75% (v/v) acetonitrile in water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min⁻¹. Glucose concentrations were calculated from standard curves prepared with authentic glucose standards.

2.5. Model Simulations

2.5.1. Flux balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux balance analysis (FBA) was employed as a constraint-based genome-scale metabolic (GSM) modeling approach to predict intracellular metabolic flux distributions in

S. thermoviolaceus. In FBA, flux distributions are calculated under mass-balance constraints defined by the stoichiometric matrix

together with upper and lower bounds for each reaction flux (

). These constraints define the feasible solution space of the metabolic network [

13], where m and n denote the number of metabolites and reactions, respectively.

A steady-state assumption was applied to all intracellular metabolites, such that metabolite accumulation was neglected:

Because the number of reactions typically exceeds the number of metabolites (n>m), the system is underdetermined and admits multiple feasible flux solutions. To obtain biologically meaningful solutions, an objective function Z, was defined as:

where c is a weighting vector specifying the contribution of each reaction flux v to the objective function.

2.5.2. Construction of the Metabolic Model

A genome-scale metabolic model of

S. thermoviolaceus was constructed based on the

E. coli K-12 MG1655 core metabolic model reported by Orth et al [

14] and obtained from the BiGG Models database. The core model (72 metabolites, 95 reactions, and 137 genes) served as a structural backbone.

To adapt the model to S. thermoviolaceus, open reading frame (ORF) sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database using the RefSeq genome assembly accession number GCF_012034235.1. Functional annotation of ORFs was performed using KEGG BLAST KOALA, and annotated pathways were reconstructed with KEGG Mapper. The resulting metabolic map was compared with the E. coli reference metabolic network, and reactions associated with central carbon metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, and energy metabolism specific to S. thermoviolaceus were subsequently incorporated into the model.

The biomass reaction was formulated based on estimated cellular composition, including amino acids, fatty acids, and nucleic acids. Stoichiometric coefficients were assigned accordingly, and the ATP hydrolysis coefficient in the biomass reaction was adjusted to minimize the relative error between experimentally measured and model-predicted specific growth rates.

2.5.3. Simulation Settings and Parameter Constraints

FBA simulations were performed using the COBRA Toolbox implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., USA) with the GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK) as the solver [

15]. Oxygen uptake was constrained to −10 mmol gDCW⁻¹ h⁻¹ to reflect aerobic cultivation conditions observed experimentally.

For wild-type simulations, biomass production was used as the objective function, assuming growth optimization under nutrient-replete conditions. In contrast, for simulations of the engineered S. thermoviolaceus::NspHI (St::NspHI) strain, biomass maximization alone failed to yield feasible flux solutions toward 3,4-AHBA production. Therefore, the experimentally determined specific growth rate was imposed as a fixed constraint, and the 3,4-AHBA exchange reaction was set as the objective function.

Specific growth rate (

) and glucose uptake rate (

) were calculated from experimental data as follows:

where

is the biomass concentration,

is the glucose concentration,

is the dry cell weight, and subscripts 1 and 2 indicate two time points during exponential growth.

2.5.4. Introduction of the 3,4-AHBA Biosynthetic Pathway

To simulate 3,4-AHBA production, the wild-type S. thermoviolaceus metabolic model was extended by introducing the heterologous 3,4-AHBA biosynthetic pathway encoded by the nspH–nspI gene operon. The corresponding reactions linking dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and L-aspartate-4-semialdehyde (ASA) to 3,4-AHBA were added to the model, generating the St::NspHI model. For production simulations, the experimentally observed growth rate was fixed, and the 3,4-AHBA exchange reaction was maximized as the objective function. This simulation strategy enabled the prediction of intracellular flux redistribution associated with 3,4-AHBA biosynthesis under physiologically relevant growth conditions and facilitated direct comparison with experimental fermentation data.

3. Results and Discussion

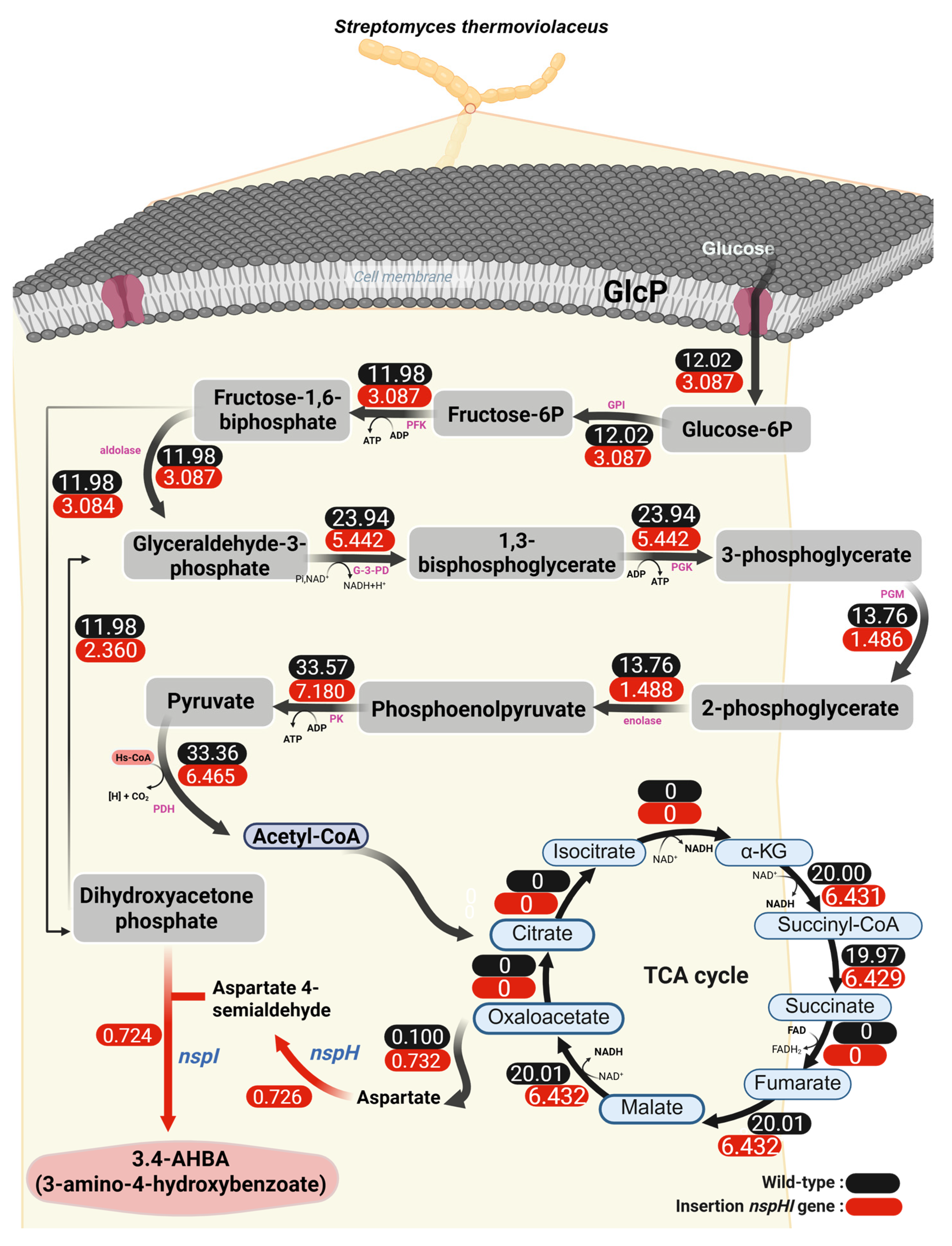

3.1. In Silico Simulation of 3.4-AHBA Production in S. thermoviolaceus Strains

In this study, we developed the first comprehensive in silico metabolic model for S. thermoviolaceus (wild type) by integrating metabolic pathways derived from E. coli and S. thermoviolaceus. The resulting wild-type model comprised 241 metabolites and 321 metabolic reactions adapted from the E. coli core metabolic network. As no previous genome-scale metabolic model has been reported for S. thermoviolaceus, this model provides a foundational framework for analyzing the metabolic behavior of this organism.

Incorporation of the 3,4-AHBA biosynthetic pathway, as well as the downstream cremeomycin biosynthesis pathway, extended the model to represent the engineered St::NspHI strain. The extended model included 246 metabolites and 333 reactions, reflecting the additional metabolic capabilities conferred by heterologous gene insertion.

Flux balance analysis (FBA) was performed to simulate 3,4-AHBA production in both the wild-type and engineered models. The oxygen uptake rate was constrained to -10 mmol gDCW⁻¹ h⁻¹ based on experimental measurements obtained during the logarithmic growth phase under aerobic conditions. Initially, biomass production was set as the objective function. Under this condition, no feasible flux distribution supporting 3,4-AHBA production could be obtained for the St::NspHI strain. This outcome reflects a fundamental limitation of growth-optimized FBA, which prioritizes biomass synthesis and does not account for flux allocation toward non-essential secondary metabolite production. In FBA, cellular fitness is typically represented by biomass formation, defined as a linear combination of amino acid, lipid, and macromolecular synthesis rates [

16], whereas actual microbial metabolism often balances growth with secondary metabolism and stress responses [

2].

To overcome this limitation, the biomass reaction was constrained to experimentally observed growth rates, and 3,4-AHBA production was set as the objective function. Using this strategy, feasible flux distributions were obtained for both strains. The predicted flux distributions are shown in

Figure 1, illustrating the wild-type strain (

Figure 1A, black values) and the

St::NspHI strain (

Figure 1B, red values). The simulations revealed a pronounced redistribution of carbon flux through glycolysis toward precursors supplying the 3,4-AHBA biosynthetic pathway. Importantly, even when individual reactions exhibited zero flux, overall metabolic flow was maintained through alternative pathways, highlighting the robustness and redundancy of the metabolic network.

These results demonstrate the utility of genome-scale in silico modeling for predicting and optimizing secondary metabolite production. Similar modeling-guided strategies have successfully enhanced 3,4-AHBA production in

Corynebacterium glutamicum under oxygen-limited conditions [

17] and improved production of secondary metabolites such as chaxamycin and daptomycin in

Streptomyces species through rational identification of metabolic engineering targets [

18,

19]. Notably, 3,4-AHBA biosynthesis proceeds via a two-step pathway catalyzed by NspI- and NspH-type enzymes, which convert dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and L-aspartate-4-semialdehyde (ASA) into 3,4-AHBA. This pathway is distinct from the canonical shikimate pathway, underscoring its metabolic efficiency and suitability for engineered production [

17,

20,

21].

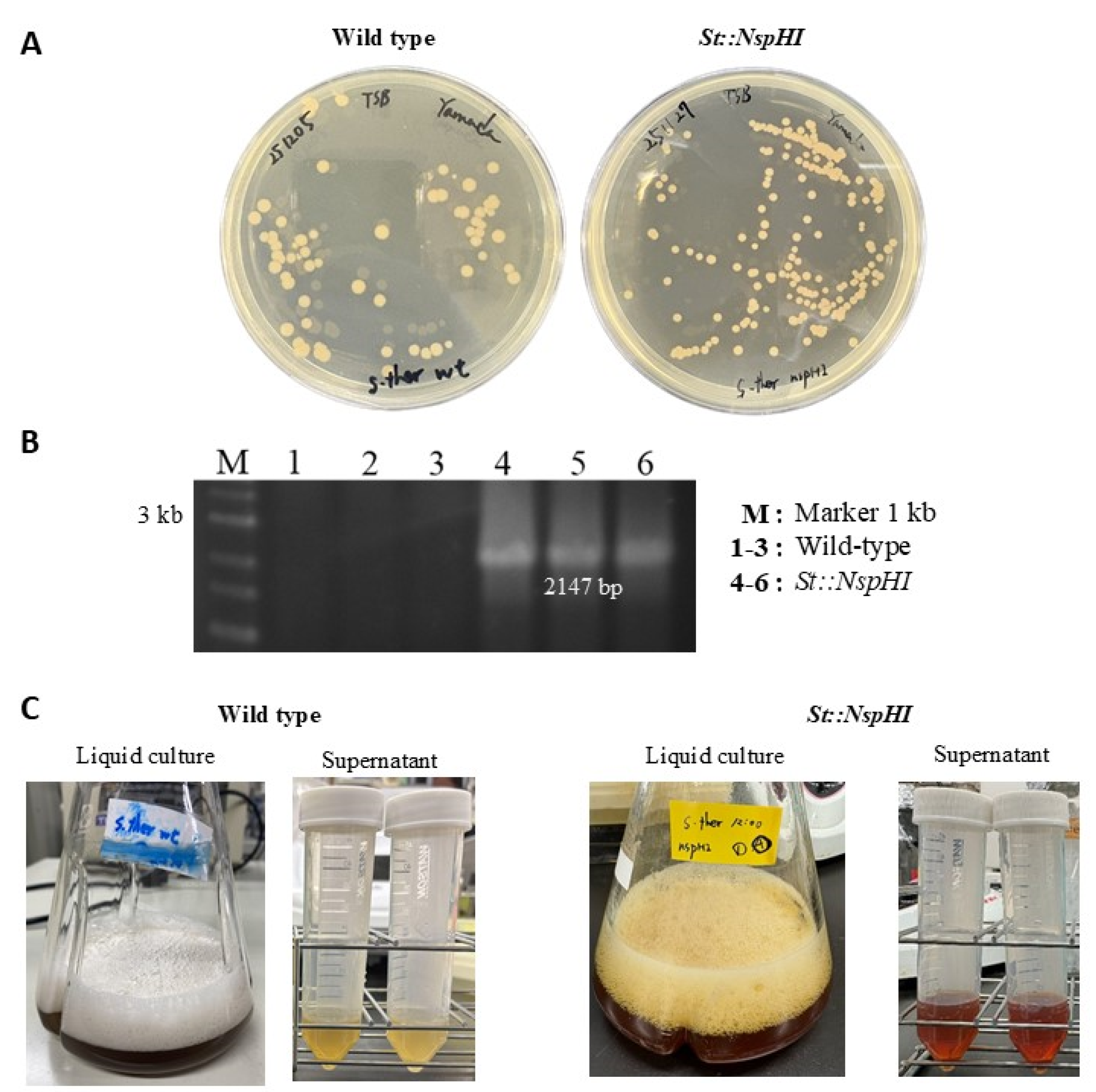

3.2. Effect of nspH–nspI Insertion on 3,4-AHBA Production

To experimentally evaluate the impact of

nspH–nspI expression on 3,4-AHBA production, the gene operon derived from

S. murayamaensis was introduced into

S. thermoviolaceus, generating the engineered

St::NspHI strain. The

nspH–nspI genes were cloned into the expression plasmid pTYM18-ermE-pldT (

Figure 2) and introduced into

S. thermoviolaceus by intergeneric conjugation (

Figure 3A). Successful plasmid integration was confirmed by colony PCR, which yielded the expected 2147 bp amplification product (

Figure 3B).

Flask cultivation experiments revealed a clear phenotypic difference between the wild-type and

St::NspHI strains. The engineered strain produced a distinct yellow pigment that was absent in the wild-type strain (

Figure 3C). This pigmentation is consistent with the enzymatic activity of the NspHI pathway and serves as a visual indicator of 3,4-AHBA biosynthesis. NspI functions as an aldolase-like enzyme catalyzing the condensation of DHAP and ASA, while NspH catalyzes the subsequent cyclization step to form the aromatic ring of 3,4-AHBA [

20].

The biochemical functions of

NspI and

NspH are closely related to those of

GriI and

GriH from

Streptomyces griseus, enzymes involved in grixazone biosynthesis (Martinet et al., 2019). In the grixazone pathway, 3,4-AHBA acts as a key precursor, suggesting potential metabolic cross-talk and shared precursor pools between pigment biosynthesis and heterologous 3,4-AHBA production. These observations underscore the role of 3,4-AHBA as a central intermediate in aromatic secondary metabolism and explain the pigment-associated phenotype observed in the engineered strain [

22].

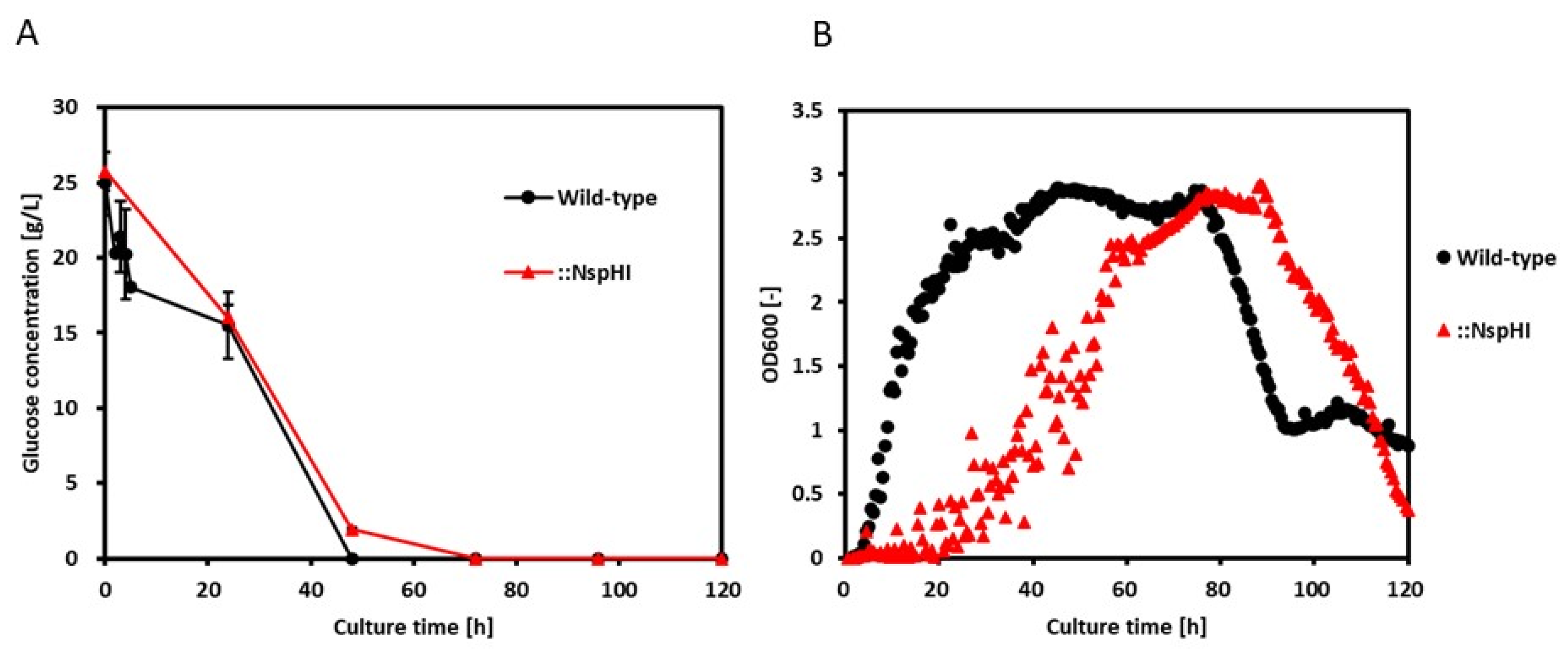

3.3. Comparison of FBA Predictions with Experimental Data

To validate the FBA predictions, time-course measurements of glucose concentration and cell growth were performed for both the wild-type and

St::NspHI strains (

Figure 4A,B). Glucose concentration measurements were obtained in duplicate (n=2). The engineered strain exhibited lower glucose uptake rates and reduced growth compared with the wild-type strain, consistent with the metabolic trade-off predicted by in silico simulations. Specific glucose uptake rates and growth rates were calculated during the logarithmic growth phase (

Figure 4C).

Experimentally determined specific growth rates were used as input constraints for FBA simulations to calculate biomass-associated fluxes (

Table 3). When biomass production was used as the objective function, the predicted growth rate for the wild-type strain (0.874 h⁻¹) closely matched the experimentally observed value (

Table 3). In contrast, the predicted growth rate for the

St::NspHI strain (0.336 h⁻¹) substantially exceeded the experimentally measured growth rate, indicating that growth-optimized FBA overestimates cellular fitness in the engineered strain. This discrepancy is most likely attributable to metabolic burden imposed by heterologous gene expression and diversion of carbon toward secondary metabolite synthesis [

23].

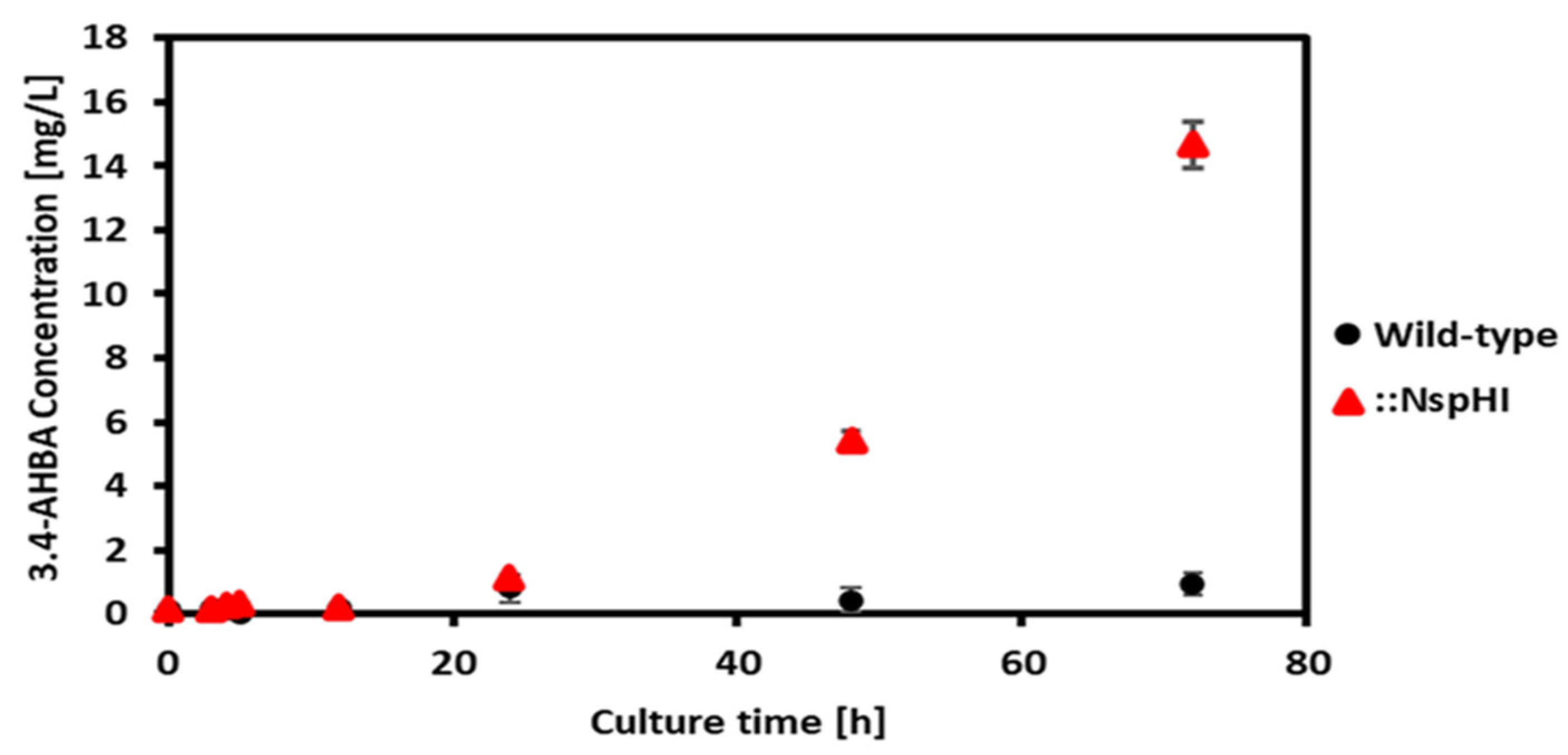

Using experimentally determined growth rates and glucose uptake rates as constraints, the 3,4-AHBA production flux was calculated by FBA (

Table 4). Despite the absence of flux through the TCA cycle in the predicted solution, the model predicted non-zero production of 3,4-AHBA, indicating that alternative metabolic pathways supplied the necessary precursors. Experimental cultivation confirmed 3,4-AHBA production exclusively in the

St::NspHI strain, with a production rate of 0.145 mmol gDCW⁻¹ h⁻¹ during the logarithmic growth phase (24–48 h) (

Figure 5). In contrast, the FBA-predicted production rate was 0.724 mmol gDCW⁻¹ h⁻¹, approximately fivefold higher than the experimental value.

This overestimation likely arises from carbon diversion to pigment production and other secondary metabolites, a well-documented phenomenon in

Streptomyces species under metabolic stress [

24]. In addition, the relatively low annotation coverage of the

S. thermoviolaceus genome (39.8%; 2069 annotated entries out of 5203) suggests that several metabolic reactions remain unaccounted for in the model, limiting prediction accuracy. These findings highlight the need to further refine the metabolic model and optimize cultivation conditions to improve 3,4-AHBA production.

Despite these limitations, the present model successfully captured the qualitative trends of growth reduction and product formation in the engineered strain. This demonstrates the utility of in silico approaches for guiding metabolic engineering strategies and provides a rational basis for future optimization of 3,4-AHBA production in S. thermoviolaceus.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the successful application of genome-scale metabolic (GSM) modeling combined with flux balance analysis (FBA) to guide the production of 3,4-amino-4-hydroxybenzoic acid (3,4-AHBA) in S. thermoviolaceus. By integrating targeted insertion of the nspH–nspI gene operon within silico metabolic simulations, we obtained system-level insights into the metabolic rewiring associated with 3,4-AHBA biosynthesis in this non-model actinomycete. Comparison of FBA predictions with experimental cultivation data revealed clear discrepancies in growth rates and product fluxes, highlighting limitations inherent to growth-optimized constraint-based models when applied to secondary metabolite production. These differences emphasize the importance of iterative refinement of metabolic models and optimization of cultivation conditions to improve quantitative predictive accuracy. Nevertheless, the model successfully captured qualitative trends in carbon flux redistribution and product formation, validating its utility as a rational design framework. Overall, this work underscores the potential of GSM-based in silico approaches to support metabolic engineering of Streptomyces species and to accelerate development of sustainable microbial routes for aromatic precursor production. Future efforts will focus on refining genome annotation, expanding the model's secondary metabolic pathways, and optimizing bioprocess conditions to further enhance the industrial applicability of 3,4-AHBA production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Y., P.A., P.K., and C.O.; data curation, T.Y. and P.A.; formal analysis, T.Y,. P.A., and P.K.; funding acquisition, C.O.; investigation, P.A. and P.K.; methodology, T.Y., P.A., P.K., T.K and Y.M.; project administration, P.K. and C.O.; resources, T.Y., P.A. and P.K.; supervision, P.K. and C.O.; validation, P.A. and P.K.; writing—original draft, T.Y. and P.A.; writing—review and editing, T.Y., P.A. and P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the International Joint Program, Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS), jointly funded by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Japan. This work was also partially supported by the GteX Program, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Japan (Grant Number JPMJGX23B4).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3.4-AHBA |

3-amino-4-hydroxybenzoic acid |

| GSM |

Genome-Scale Metabolic modeling |

| GEM |

Genome-scale metabolic model |

| FBA |

Flux Balance Analysis |

| S. thermoviolaceus |

Streptomyces thermoviolaceus |

| GAM |

Growth-associated maintenance |

| NGAM |

Non-growth-associated maintenance |

| NBRC |

NITE Biological Resource Center |

| NCBI |

National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| KEGG |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

References

- Osterlund, T.; Nookaew, I.; Bordel, S.; Nielsen, J. Mapping Condition-Dependent Regulation of Metabolism in Yeast through Genome-Scale Modeling. 2013.

- Vikromvarasiri, N.; Shirai, T.; Kondo, A. Metabolic Engineering Design to Enhance (R,R)-2,3-Butanediol Production from Glycerol in Bacillus Subtilis Based on Flux Balance Analysis. Microb Cell Fact 2021, 20, 196. [CrossRef]

- Feist, A.M.; Henry, C.S.; Reed, J.L.; Krummenacker, M.; Joyce, A.R.; Karp, P.D.; Broadbelt, L.J.; Hatzimanikatis, V.; Palsson, B.O. A Genome-scale Metabolic Reconstruction for Escherichia Coli K-12 MG1655 That Accounts for 1260 ORFs and Thermodynamic Information. Mol Syst Biol 2007, 3. [CrossRef]

- Orth, J.D.; Thiele, I.; Palsson, B.Ø. What Is Flux Balance Analysis? Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 245–248. [CrossRef]

- Simensen, V.; Schulz, C.; Karlsen, E.; Bråtelund, S.; Burgos, I.; Thorfinnsdottir, L.B.; García-Calvo, L.; Bruheim, P.; Almaas, E. Experimental Determination of Escherichia Coli Biomass Composition for Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262450. [CrossRef]

- Tokuyama, K.; Ohno, S.; Yoshikawa, K.; Hirasawa, T.; Tanaka, S.; Furusawa, C.; Shimizu, H. Increased 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid Production from Glycerol, by Modification of Central Metabolism in Escherichia Coli. Microb Cell Fact 2014, 13, 64. [CrossRef]

- Bentley, S.D.; Chater, K.F.; Cerdeño-Tárraga, A.M.; Challis, G.L.; Thomson, N.R.; James, K.D.; Harris, D.E.; Quail, M.A.; Kieser, H.; Harper, D.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of the Model Actinomycete Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). Nature 2002, 417, 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, N.; Ogino, C.; Kondo, A. Production of Chemicals and Proteins Using Biomass-Derived Substrates from a Streptomyces Host. Bioresour Technol 2017, 245, 1655–1663. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Hwang, S.; Kim, W.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.U.; Yoon, Y.J.; Oh, M.-K.; Palsson, B.O.; et al. Systems and Synthetic Biology to Elucidate Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Clusters Encoded in Streptomyces Genomes. Nat Prod Rep 2021, 38, 1330–1361. [CrossRef]

- Tsujibo, H.; Hatano, N.; Endo, H.; Miyamoto, K.; Inamori, Y. Purification and Characterization of a Thermostable Chitinase from Streptomyces Thermoviolaceus OPC-520 and Cloning of the Encoding Gene. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2000, 64, 96–102. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, H.; Sasaki, K.; Uematsu, K.; Tsuge, Y.; Teramura, H.; Okai, N.; Nakamura-Tsuruta, S.; Katsuyama, Y.; Sugai, Y.; Ohnishi, Y.; et al. 3-Amino-4-Hydroxybenzoic Acid Production from Sweet Sorghum Juice by Recombinant Corynebacterium Glutamicum. Bioresour Technol 2015, 198, 410–417. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Sang Yi, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.W.; Kim, B. Reconstruction of a High-quality Metabolic Model Enables the Identification of Gene Overexpression Targets for Enhanced Antibiotic Production in Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). Biotechnol J 2014, 9, 1185–1194. [CrossRef]

- Orth, J.D.; Fleming, R.M.T.; Palsson, B.Ø. Reconstruction and Use of Microbial Metabolic Networks: The Core Escherichia Coli Metabolic Model as an Educational Guide. EcoSal Plus 2010, 4. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.A.; Feist, A.M.; Mo, M.L.; Hannum, G.; Palsson, B.Ø.; Herrgard, M.J. Quantitative Prediction of Cellular Metabolism with Constraint-Based Models: The COBRA Toolbox. Nat Protoc 2007, 2, 727–738. [CrossRef]

- Hasibi, R.; Michoel, T.; Oyarzún, D.A. Integration of Graph Neural Networks and Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for Predicting Gene Essentiality. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2024, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, H.; Hasunuma, T.; Ohnishi, Y.; Sazuka, T.; Kondo, A.; Ogino, C. Enhanced Production of γ-Amino Acid 3-Amino-4-Hydroxybenzoic Acid by Recombinant Corynebacterium Glutamicum under Oxygen Limitation. Microb Cell Fact 2021, 20, 228. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wen, J.; Wang, G.; Yu, G.; Jia, X.; Chen, Y. In Silico Aided Metabolic Engineering of Streptomyces Roseosporus for Daptomycin Yield Improvement. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 94, 637–649. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, A.; Razmilic, V.; Brain-Isasi, S.; Andrews, B.; Asenjo, J.A. Metabolic Engineering of Streptomyces Leeuwenhoekii C34 T to Increase Chaxamycin Production Based on the i VR1007 Genome-Scale Model. Biotechnol Bioeng 2025, 122, 3376–3392. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohnishi, Y.; Furusho, Y.; Sakuda, S.; Horinouchi, S. Novel Benzene Ring Biosynthesis from C3 and C4 Primary Metabolites by Two Enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 36944–36951. [CrossRef]

- Niimi-Nakamura, S.; Kawaguchi, H.; Uematsu, K.; Teramura, H.; Nakamura-Tsuruta, S.; Kashiwagi, N.; Sugai, Y.; Katsuyama, Y.; Ohnishi, Y.; Ogino, C.; et al. 3-Amino-4-Hydroxybenzoic Acid Production from Glucose and/or Xylose via Recombinant Streptomyces Lividans. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2022, 68, 2022.06.001. [CrossRef]

- OHNISHI, Y.; FURUSHO, Y.; HIGASHI, T.; CHUN, H.-K.; FURIHATA, K.; SAKUDA, S.; HORINOUCHI, S. Structures of Grixazone A and B, A-Factor-Dependent Yellow Pigments Produced under Phosphate Depletion by Streptomyces Griseus. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2004, 57, 218–223. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yan, Q.; Jones, J.A.; Tang, Y.J.; Fong, S.S.; Koffas, M.A.G. Metabolic Burden: Cornerstones in Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering Applications. Trends Biotechnol 2016, 34, 652–664. [CrossRef]

- Asah-Asante, R.; Tang, L.; Gong, X.; Fan, S.; Yan, C.; Asante, J.O.; Zeng, Q. Exploring Pigment-Producing Streptomyces as an Alternative Source to Synthetic Pigments: Diversity, Biosynthesis, and Biotechnological Applications. A Review. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2025, 41, 211. [CrossRef]

- Onaka, H.; Taniguchi, S.-I.; Ikeda, H.; Igarashi, Y.; Fuurumai, T. PTOYAMAcos, PTYM18, and PTYM19, Actinomycete-Escherichia Coli Integrating Vectors for Heterologous Gene Expression. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2003, 56, 950–956. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).