1. Introduction

Cultural heritage buildings are among the fundamental elements that serve as tangible representations of a society’s identity, historical memory, and aesthetic values, thus establishing a bridge between the past and the future (Jokilehto, 2017). These structures do not merely possess historical or aesthetic significance; they also embody the layered traces of the social, economic, and cultural development of the geographical context in which they are located (Feilden, 2007). This multilayered nature necessitates a holistic and balanced approach to the conservation process—one that does not focus on a single period or feature, but rather considers the various historical phases collectively (Stubbs, 2009).

Modern conservation theory, particularly since the second half of the twentieth century, has emphasized the need to document, analyze, and preserve historically stratified buildings. This perspective is clearly articulated in the Venice Charter (1964), and later expanded upon in documents such as the Burra Charter (1979), which introduced the concept of cultural continuity (ICOMOS, 1964, Article 7; Australia ICOMOS, 2013). Multilayered structures are now recognized not only as carriers of the period in which they were originally built but also of all subsequent interventions and values accumulated over time (Jokilehto, 2017).

In this context, the conservation of cultural heritage buildings today goes beyond the mere preservation of physical integrity. It also aims to reintegrate these structures into social life, adapt them for new functions, and ensure cultural sustainability (Rodwell, 2008). This approach is embodied in “adaptive reuse” strategies, which acknowledge that cultural heritage should not be seen as a static value of the past, but rather as a living component of collective memory (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011).

However, the adaptive reuse process presents a number of challenges, including the need to protect original historical values, ensure compatibility between new additions and existing fabric, and interpret the multilayered character of the structure correctly (Bullen & Love, 2011). These challenges become more pronounced in the case of small-scale, rural religious buildings that have been abandoned for extended periods (Orbaşlı, 2007).

The Aya Payana (Aya Baniya) Church, located in the province of Isparta in Türkiye and dating back to the late Ottoman period, exemplifies a site with a culturally and functionally layered history. While the building has largely preserved its original architectural characteristics and spatial configuration, its successive uses—as a religious structure, a military storage facility, and eventually an abandoned space—have imbued it with diverse cultural meanings over time. Rather than physical alterations, it is this evolving functional narrative that constitutes the site’s stratified heritage value. (

Figure 1).

The partial preservation of the building’s physical integrity today renders it a compelling candidate for conservation and adaptive reuse initiatives. This study aims to investigate the documentation, evaluation, and reinterpretation of a culturally and functionally stratified heritage site through the example of the Aya Payana Church. Emphasizing the notion of cultural continuity, the research explores how a historically layered narrative—despite minimal physical transformations—can inform sustainable reuse strategies.

A comprehensive methodological approach was employed, including the preparation of analytical survey drawings to document historical characteristics, laboratory-based material analyses, and structural assessments based on static calculations. These evaluations informed the design of spatial interventions such as an olfactory museum (Kokuhane) and cultural activity zones, intended to foster public engagement and reinterpret the site’s heritage values through sensory and participatory experiences (

Figure 2).

Within this framework, the study has been structured in alignment with established conservation theories in the literature (Jokilehto, 2017; Feilden, 2007; Rodwell, 2008), and the proposed interventions are grounded in internationally recognized principles (ICOMOS, 1964; Australia ICOMOS, 2013). Additionally, within the scope of cultural sustainability, the research provides a platform for discussing how new functions can be harmonized with the architectural identity and historical values of the structure (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders & Colenbrander, 2013).

This article aims to present an original approach to conservation and adaptive reuse strategies for multi-layered structures, using the Aya Payana Church as a case study. In doing so, it seeks to propose a holistic model that ensures the preservation of historical authenticity while facilitating the reintegration of the building into contemporary social life through the continuity of its cultural significance.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a multi-phase methodological approach to document the multi-layered historical structure of the Aya Payana Church, analyze its current condition, and develop adaptive reuse strategies within the framework of cultural sustainability principles. The applied methods are based on both fieldwork and a combination of laboratory and theoretical analyses.

2.1. Documentation Process

In the initial phase, the structure was documented using traditional measured drawing techniques. To assess the current state of the building, plans, sections, and elevations were produced; deformations, material differences, and deteriorations were recorded in detail through analytical survey methods (Letellier et al., 2007). Contemporary documentation technologies such as laser scanning and photogrammetric measurement were also employed as complementary tools during this process (Bryan, Andrews & Blake, 2013) (

Figure 3).

Types of deterioration including cracking, discoloration, biological colonization, and material degradation were detected during the surface analysis and recorded through a systematic documentation process (

Figure 4).

These documents served as a data source for the subsequent intervention and adaptive reuse decisions.

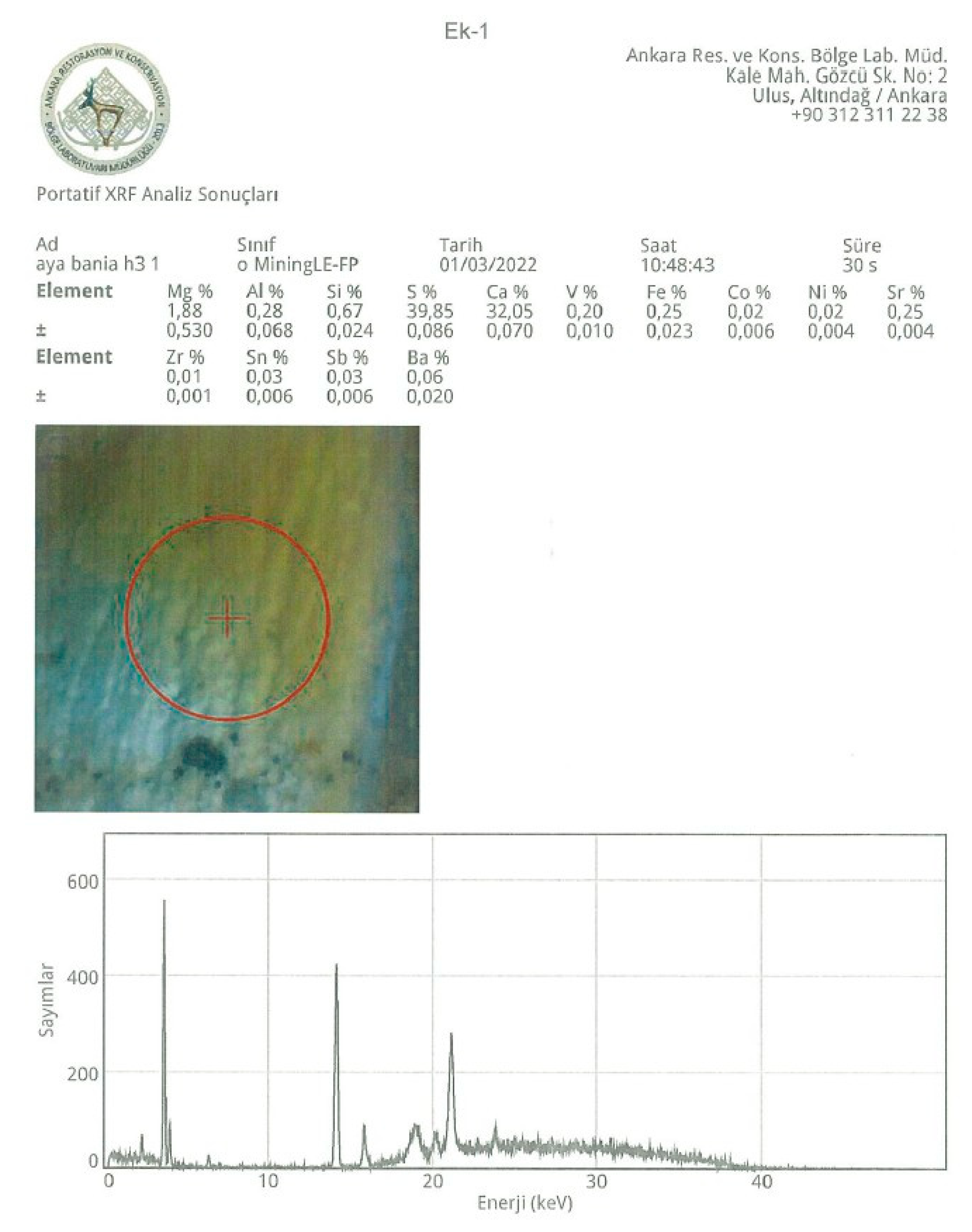

2.2. Material Analyses

In order to understand the original material characteristics of the structure, samples were collected during fieldwork and analyzed in a laboratory setting. Petrographic, chemical, and physical tests were conducted on the collected samples of stone, plaster, and mortar (Historic England, 2012). Special attention was given to analyzing the lime content of the original plasters, signs of salt crystallization on stone blocks, and the types of aggregates found within the mortar (Young, 2008).

SEM-EDX analyses were used to examine the microstructure and chemical composition of the building materials, confirming salt crystallization and carbonation mechanisms (Price & Doehne, 2011). In addition, XRD analyses were employed to identify the mineralogical composition of existing mortars and stone materials, which is a common approach in the investigation of stone decay processes (Smith & Turkington, 2016).

The findings of the material analyses played a critical role in defining intervention strategies and guided the development of repair techniques compatible with the original materials.

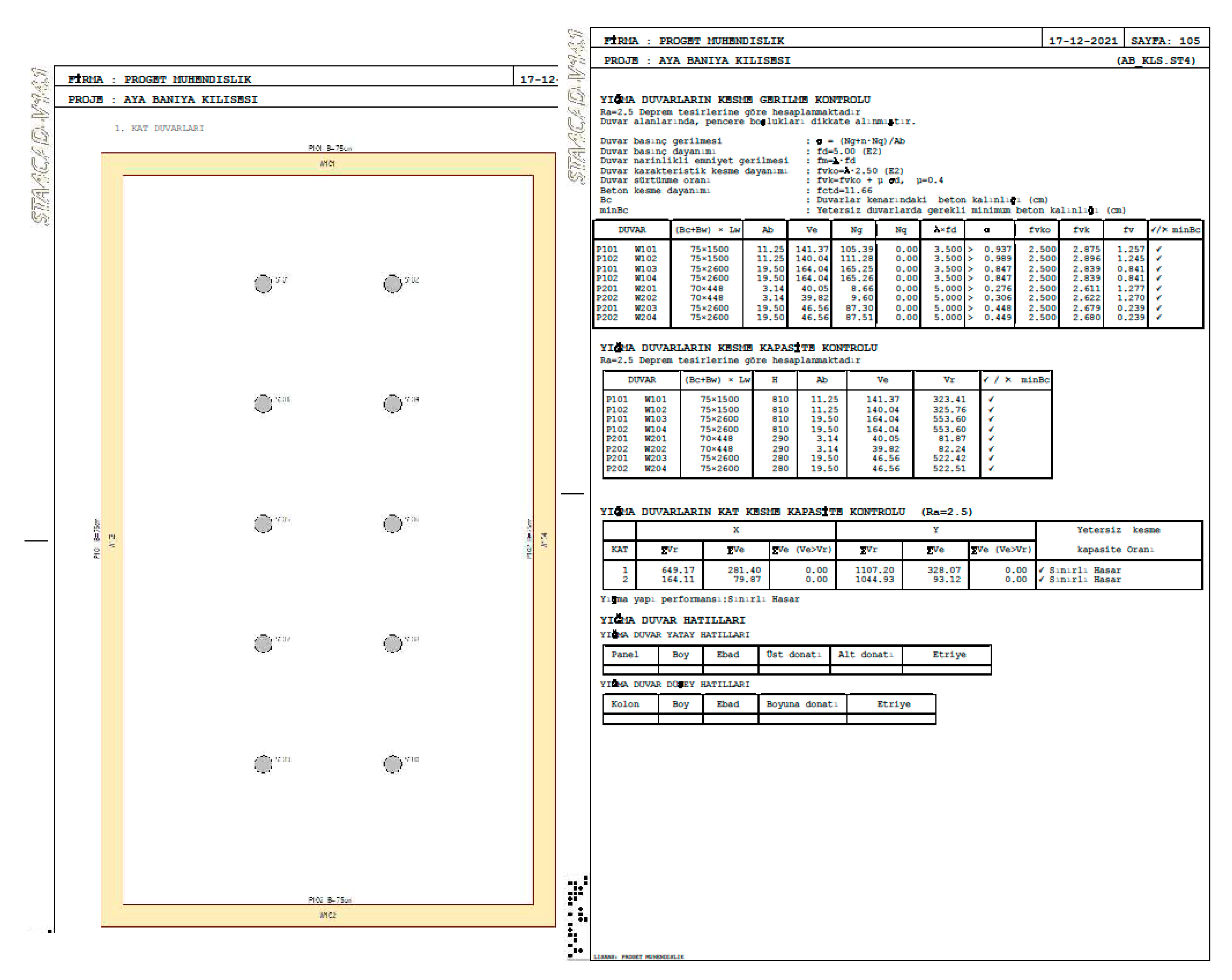

2.3. Structural System and Static Analysis

The existing structural system of the Aya Payana Church was assessed through visual inspections and software-assisted structural analysis. The load-bearing capacity, deformation levels, and probable damage mechanisms were evaluated through an integrated diagnostic-and-assessment approach. (Roca et al., 2010; Bosiljkov et al., 2010; Binda et al., 2009).

The structure was modeled using the STA4CAD software, and a performance analysis was carried out in accordance with the provisions of the Turkish Building Earthquake Code (TBDY, 2018, Article 7.5). Static weaknesses observed in the apse, deformations on the roof covering, and crack formations in the wall systems were all confirmed through this analysis process (

Figure 5).

As a result of these evaluations, structurally vulnerable areas were identified, and intervention methods compatible with the traditional load-bearing system were developed. These included the use of steel tie rods, carbon fiber strips, and lime-based injection techniques.

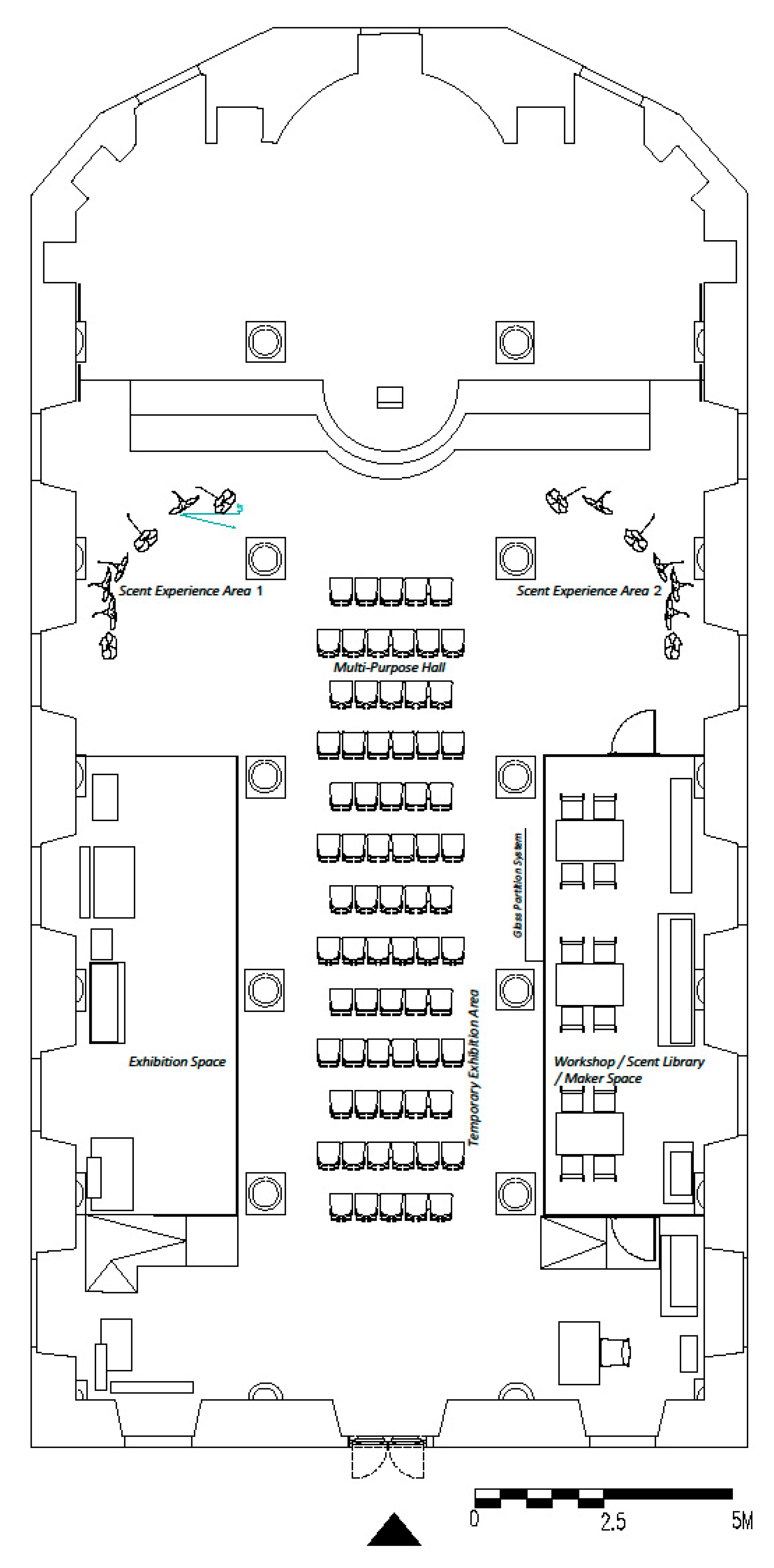

2.4. Adaptive Reuse Design Process

In determining the conservation strategies, an adaptive reuse scenario was designed that would not compromise the architectural identity of the building. During the planning of the olfactory museum (Kokuhane) and cultural activity zones, the existing spatial configuration of the structure was respected, and the new functions were integrated in a way that would not interfere with the original load-bearing system or material fabric (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011).

This process was guided by international examples of adaptive reuse, particularly comparable religious building transformations in Australia and Europe (Douglas, 2006).

In addition, visitor circulation, accessibility criteria, and user experience were considered during the planning phase to ensure a balanced integration of the new functions with the scale and character of the building (

Figure 6).

3. Documented Historical Layers and Current Condition Analysis

Multi-layered historical structures not only reflect the architectural characteristics of a particular period but also serve as carriers of subsequent transformations and socio-cultural influences (Ashurst, 2007). In this context, the Aya Payana Church embodies a stratified narrative, incorporating traces of its original construction phase alongside later interventions.

3.1. Characteristics of the Original Construction Period

The original construction phase of the building dates back to the last quarter of the 19th century. The church represents a rural example of traditional Eastern Orthodox architecture, characterized by its modest plan layout, rubble masonry walls, and a timber-framed pitched roof structure (Orbaşlı, 2007).

In terms of construction technique, the walls are primarily composed of roughly dressed stone blocks, with joints bonded using a locally produced lime-based mortar. The absence of reinforced concrete or steel components in the load-bearing system confirms that the structure was entirely built using traditional materials and techniques (

Figure 7).

In the apse section of the building, the small-sized ashlar blocks display a higher quality of craftsmanship on the eastern façade, while the northern and western façades exhibit a more prominent use of rough masonry (Fielden, 2003).

3.2. Interventions and Alterations Over Time

- -

Throughout its period of use, the Aya Payana Church was subjected to a series of minor-scale interventions. These include:

- -

The narrowing of door and window openings,

- -

Partial renewal of sections of the timber roof structure,

- -

Replacement or partial modification of interior plaster coatings (Rodwell, 2008).

- -

By the mid-20

th century, the church lost its religious function and was subsequently abandoned. As a result, the unprotected building materials suffered significant deterioration. In particular, the collapse of the roof covering exposed the structural system to prolonged moisture ingress, which began to compromise the integrity of the load-bearing components (

Figure 8).

3.3. Analysis of Structural Elements in the Current Condition

- Walls

Extensive cracking, surface darkening, and biological growths (such as mosses and lichens) have been identified on the wall surfaces (Price & Doehne, 2011). Particularly on the northern façade, plaster detachment due to moisture exposure and signs of flaking on the stone surfaces have been observed (

Figure 9).

- Roof Structure

A large portion of the roof covering has collapsed, and the remaining sections show evidence of biological deterioration in the timber load-bearing elements. Visual inspections have revealed typical forms of biological damage in the timber, including decay, insect infestation, and fiber separation (Watt, 2025).

-Apse and Interior Space

Although the original materials have been preserved in the stone masonry of the apse, significant carbonation and cracking have been observed in the mortar joints. Within the interior space, irregular settlement traces on the floor level and salt efflorescence due to moisture exposure on the plaster surfaces have been documented (Young, 2008).

3.4. Material Stratigraphy of the Structure

The material stratigraphy of the structure reveals that successive repair layers were added over the original stone and plaster components. Analytical survey studies and laboratory analyses have demonstrated that the plasters used in different periods show clear differences in lime content, binder type, and color tone (Ashurst, 2007; Young, 2008).

It was determined that the original plaster layers were based on hydraulic lime, whereas later interventions involved modern mortars containing cement additives (

Figure 10).

3.5. General Typology of Deterioration

The principal types of deterioration observed in the building are as follows:

Formation of cracks and structural deformations,

Carbonation and flaking of surface stones,

Loss of mortar in stone joints,

Biological deterioration in timber elements,

Salt efflorescence, blistering, and detachment on plaster surfaces (Ashurst, 2007).

Each of these deterioration types served as a fundamental reference for the intervention strategies detailed in the following sections.

4. Intervention Strategies and Conservation Approach

The conservation process of cultural heritage buildings involves not only the remediation of physical deterioration but also the sustainable transmission of the structure’s original identity, historical layers, and material character into the future (Feilden, 2007). Accordingly, the intervention strategies developed for the Aya Payana Church were based on a scientific analysis of existing problems, the preservation of original materials and construction techniques, and adherence to the principle of minimum intervention with clearly defined justifications for each action.

4.1. Principles of Intervention

The interventions proposed for the Aya Payana Church were grounded in the core principles articulated in international conservation documents (e.g., Venice Charter, 1964; Burra Charter, 2013) and contemporary conservation theory (Rodwell, 2008):

Minimum Intervention: All interventions were executed only to the extent strictly necessary (Feilden, 2007).

Reversibility: New additions were designed to be removable without damaging the original structure (Matero, 2003).

Documentation: Each intervention was preceded and followed by comprehensive photographic and graphic documentation (Letellier et al., 2007).

Preservation of Authenticity and Identity: The original materials, form, and structural configuration of the building were preserved (Jokilehto, 2017).

Based on these principles, the intervention strategies were divided into two main categories: material repairs and structural strengthening aimed at addressing the building’s current issues.

4.2. Structural Strengthening Interventions

4.2.1. Wall Systems

For the cracks and voids observed in the load-bearing masonry walls, a low-pressure injection method was applied. Hydraulic lime-based grouts, prepared according to traditional techniques, were injected into the cracks using controlled pressure systems (Ashurst, 2007).

In areas where larger cracks were present—particularly at the intersection of the apse and the naos—stitching techniques were employed on both the interior and exterior faces. These repairs utilized a combination of stainless steel rods and natural stone anchors (

Watt, 2025) (

Figure 11).

4.2.2. Roof Structure

As part of the intervention addressing the collapse of the roof covering, a new roof frame was constructed in accordance with the restitution of the original timber load-bearing system. The timber used was selected from low-density, impregnated species suitable for the local climatic conditions (Historic England, 2012).

In designing the new roof structure, special attention was paid to improving rainwater drainage while preserving the architectural silhouette of the building. Traditional alaturka clay tiles were chosen as the roofing material.

4.3. Material Repair Interventions

4.3.1. Stone Surface Repairs

For surface stones showing signs of carbonation and material loss, micro-injection techniques and surface consolidation treatments were applied. Ethyl silicate-based consolidants were used in low concentrations and under controlled conditions (Price & Doehne, 2011).Biological growth was removed through mechanical cleaning followed by the application of biocides (Ashurst, 2007).

4.3.2. Plaster and Joint Repairs

Original lime-based plasters were preserved, and deteriorated areas were repaired using newly prepared mortars of similar composition. These interventions followed traditional repair approaches, incorporating mixtures of lime, aggregates, and mineral pigments (Young, 2008). Repointing of joints was carried out using lime-based mortars compatible with the original joint profiles and material characteristics, in accordance with established conservation principles for stone and mortar decay (Smith & Turkington, 2016).

4.4. Evaluation of the Conservation Philosophy and Intervention Approach

The intervention strategies implemented at the Aya Payana Church were designed to highlight the building’s original values. Modern materials were used only when necessary and under the condition of reversibility, ensuring that no visual or structural pressure was imposed on the original identity of the building. Particular emphasis was placed on strengthening the structural system without compromising aesthetic integrity, while material repairs respected and revealed the historical stratification of the structure (Matero, 2003). This holistic approach not only addresses the existing physical problems but also aims to establish a sustainable conservation model that supports cultural continuity and facilitates future maintenance processes.

5. Adaptive Reuse Strategies and Cultural Sustainability

5.1. Adaptive Reuse Approach and the Case of Aya Payana

In contemporary conservation practice, protecting cultural heritage structures entails not only preserving their physical existence but also ensuring their social, cultural, and economic functionality (Rodwell, 2008). Adaptive reuse strategies developed in this context assign new functions to historic structures, thereby supporting their sustainable use and reinforcing cultural continuity (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011).

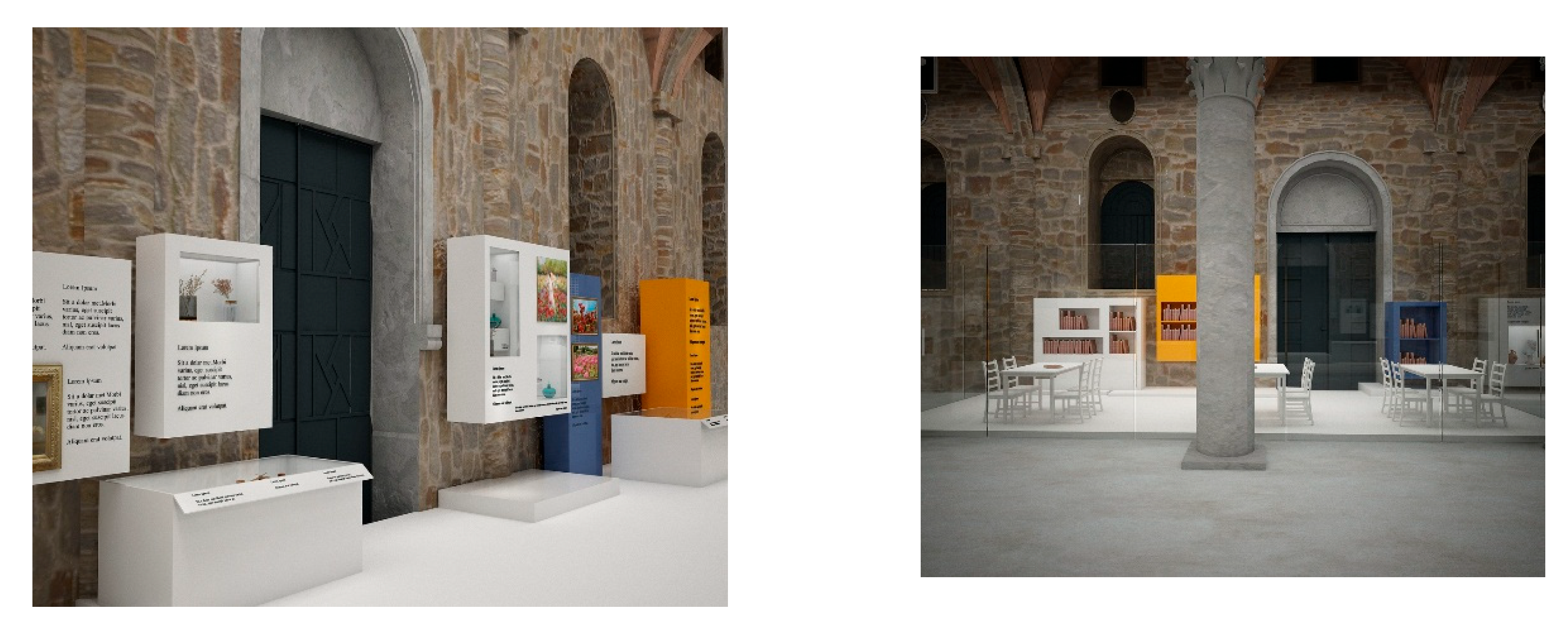

In the case of the Aya Payana Church, the aim was to integrate a new function—Kokuhane (a scent museum)—while preserving the multi-layered historical character of the building. This approach seeks to make the building’s heritage values visible, contribute to collective memory, and promote the continuation of cultural heritage as a living component (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders & Colenbrander, 2013).

An analysis of the building’s spatial organization revealed a high potential for adapting existing spaces to new functions. The original structural system and spatial layout were preserved, and the spaces were reinterpreted solely in terms of content and usage (Douglas, 2006).

5.2. Scent Museum Concept (Kokuhane) Design: Spatial Organization of the Scent Museum

The Kokuhane concept aims to offer a sensory museum experience centered around the sense of smell. The spatial arrangement proposed within the Aya Payana Church was designed with minimal intervention into the existing structural and spatial components:

Entrance Foyer: An introductory area where visitors are prepared for the museum experience and informed about the relationship between scent and memory (

see Figure 13: Entrance Foyer Design Diagram).

Main Exhibition Area (Naos): An interactive exhibition zone featuring modules for experiencing various plant-based scents.

Laboratory Area: A small-scale production and educational space where essences extracted from aromatic plants grown in the garden are processed.

Workshop and Education Area: Flexible spaces designed for visitor engagement in the process of natural essence production through participatory workshops (

Figure 12).

The Kokuhane installation was designed without introducing any structural alterations to the building, preserving its original architectural elements and enhancing the existing spatial atmosphere (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011) (

Figure 13).

This spatial intervention seeks to foster a deeper engagement with the site by appealing not only to visual perception, but also to the senses of smell and emotion (Ripp & Rodwell, 2015) (

Figure 14).

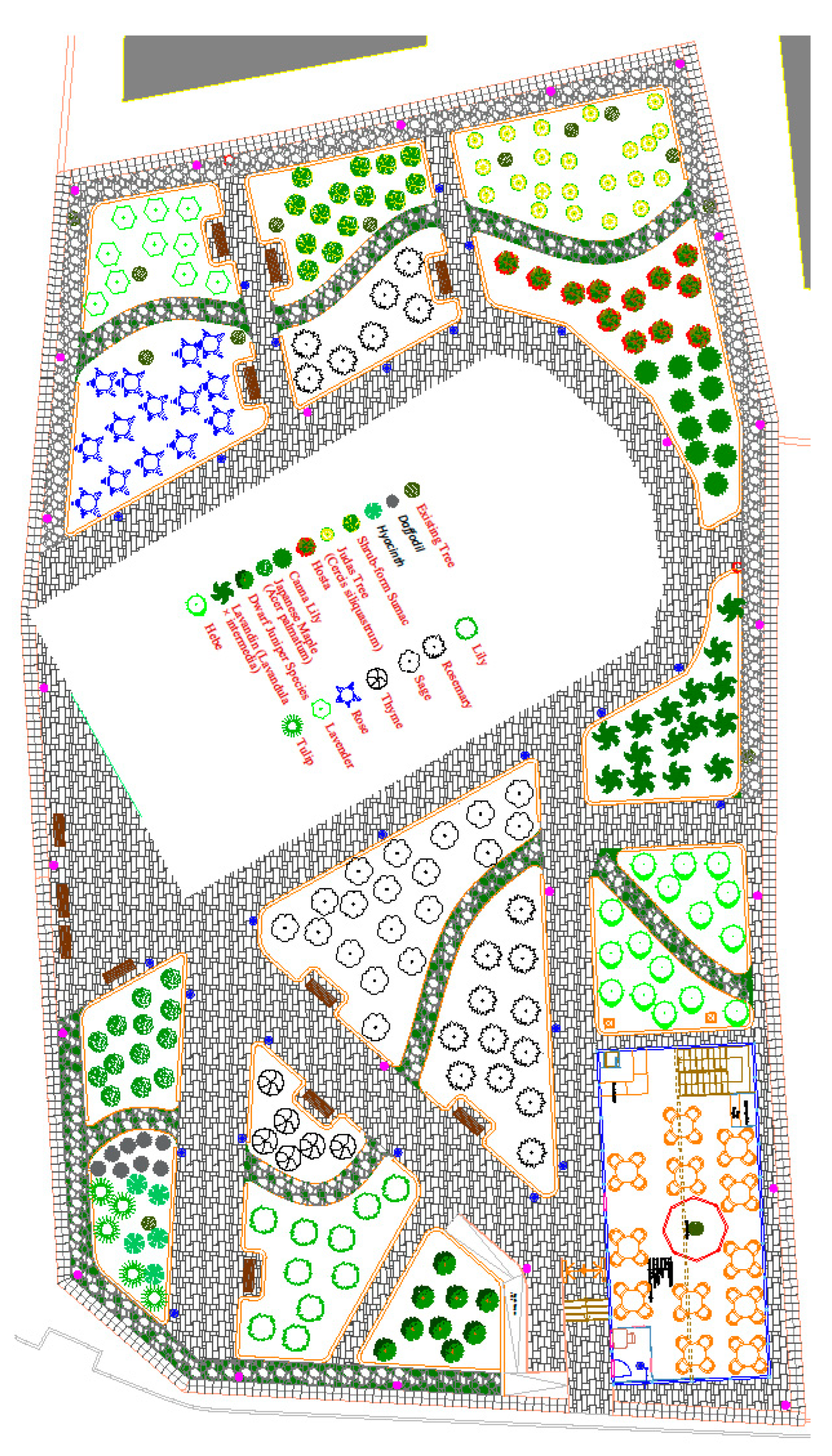

5.3. Botanical Garden and Scent Production Strategy

The existing open space of the Aya Payana Church has been refunctionalized not merely as a landscape arrangement, but as an integrated mechanism of cultural sustainability. Within this scope, the botanical garden designed around the church holds both aesthetic and functional significance.

5.3.1. Selection of Local Plant Species

In selecting the plants to be cultivated in the garden, priority was given to traditional aromatic and medicinal species that are ecologically suited to the region. This choice has been adopted as a key strategy supporting both ecological sustainability and cultural continuity (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders & Colenbrander, 2013).

The proposed species include: Lavender (Lavandula spp.), Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), Sage (Salvia officinalis), Thyme (Thymus vulgaris), Judas Tree (Cercis siliquastrum), Hyacinth (Hyacinthus orientalis), Daffodil (Narcissus spp.), Rose (Rosa spp.), and Dwarf Juniper species (Juniperus spp.) (

Figure 15).

5.3.2. Scent Production and Laboratory Integration

The aromatic plants cultivated in the garden will be integrated into the scent production process through the laboratory space organized within the building. This strategy transforms the museum experience from a passive form of observation into an active process of production and engagement (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011).

Through simple distillation and extraction procedures carried out in the laboratory, scent samples will be obtained from garden plants, and visitors will have the opportunity to participate directly in these processes. In this way, the museum is conceived not merely as a space for narrating the past, but as an active environment of cultural production and engagement (Smith & Turkington, 2016).

This model also holds the potential to bridge traditional local knowledge of plant use with a contemporary museum experience. By collaborating with local producers, products derived from the cultivated plants can be offered for sale in the museum shop, thereby supporting economic sustainability (Ripp & Rodwell, 2015).

5.3.3. Ecological Balance in Garden Design

During the garden planning phase, low-water-consumption and climate-adapted plant species were selected to reduce maintenance costs and minimize the ecological footprint. The plants were also chosen based on their blooming periods to ensure visual and olfactory continuity throughout the year (Historic England, 2012).

This approach contributes to the conservation of natural resources while offering visitors the opportunity to experience seasonal changes and engage with natural cycles (Price & Doehne, 2011).

5.4. Transparent Cafeteria Design: A Respectful Architectural Addition

In the adaptive reuse process of cultural heritage buildings, the need for architectural additions may arise. However, a fundamental principle in the design of such interventions is the preservation of the original silhouette and perceptual integrity of the historical structure (ICOMOS, 1964, Article 9; Australia ICOMOS, 2013). Accordingly, the transparent cafeteria proposed for the Aya Payana Church was developed as an exemplary intervention fully aligned with international conservation doctrines.

5.4.1. The Role of Transparency in Conservation Practice

Both the Venice Charter (1964) and the Burra Charter (2013) emphasize that new additions should be distinguishable from the original structure and should not obscure its architectural perception (Australia ICOMOS, 2013). In contemporary architectural language, transparency is regarded as the most direct expression of this principle (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011).

Transparent materials—such as glass and lightweight steel structures—enable new additions to be visually unobtrusive while maintaining a clear presence without overwhelming the historic mass. Through this approach:

The silhouette, façade articulation, and volumetric impact of the historical building remain uninterrupted;

Visitors’ attention is guided toward the heritage structure;

The distinction between historical and contemporary interventions is made clearly legible (Rodwell, 2008) (

Figure 16).

5.4.2. Enhancing the Visitor Experience

One of the primary goals of the cafeteria design was to create a support area where visitors could meet their essential needs during their museum visit. Through the use of transparent materials:

Visitors can continue to experience the surrounding natural landscape and the historical structure,

They can rest and socialize without disconnecting from the heritage building (Douglas, 2006).

This setting contributes to prolonging the duration of the visit, deepening the time spent within the site, and thus enhancing the overall impact of the cultural experience (Ripp & Rodwell, 2015).

5.4.3. Contribution to Economic and Social Sustainability

The cafeteria is not only intended to improve visitor comfort, but also to function as a revenue-generating component within the operational model of the site. In this way:

Visitor spending will support the site’s economic sustainability,

A platform will be created for local producers to showcase and sell their goods,

A social connection will be fostered between the heritage site and the local community (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders & Colenbrander, 2013).

This strategy aligns with contemporary conservation approaches that emphasize not only preserving cultural heritage but integrating it into the life of the community.

5.5. Cultural Sustainability Assessment

The conservation of cultural heritage structures involves more than maintaining their physical integrity; it also requires sustaining their significance, meanings, and functional value within the collective memory (Rodwell, 2008). In this context, the adaptive reuse strategies developed for the Aya Payana Church aim not only to preserve the structure as a relic of the past but to ensure its continued relevance as a living cultural asset.

5.5.1. Collective Memory and Cultural Identity

The Aya Payana Church is valuable not only for its architectural features but also as a bearer of the social history and cultural diversity of its region. By reactivating the site through functions such as a scent museum (Kokuhane) and botanical garden, the project allows local communities to reconnect with the space, bridging past and present (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders & Colenbrander, 2013).

The olfactory experience in particular, as a powerful trigger of memory, is expected to have profound and lasting effects on collective remembrance (Herz, 2004).

5.5.2. Education and Community Engagement

The laboratory and workshop spaces within Kokuhane were designed to allow visitors to actively participate in traditional practices such as essential oil production. In this way:

Visitors can engage with natural scent production techniques and connect directly with traditional knowledge,

Educational programs can foster cultural heritage awareness among younger generations (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011).

This approach serves as a strong example of the community-based conservation model, which has gained increasing importance in recent years (Ripp & Rodwell, 2015).

5.5.3. Economic and Social Sustainability

The adaptively reused structure contributes not only to cultural continuity but also to economic sustainability. Support units such as the cafeteria and museum shop:

Create a platform for local producers to present their products to visitors,

Support the site’s operational costs,

Establish an organic relationship between the local economy and cultural heritage (Veldpaus, Pereira Roders & Colenbrander, 2013).

This model demonstrates a successful implementation of the principle of “sustaining heritage through active use” (Rodwell, 2008).

5.5.4. Environmental Sustainability

The selection of local, low-water-consuming plant species for the botanical garden contributes to reducing the environmental footprint and promotes the efficient use of natural resources (Historic England, 2012). This strategy represents a contemporary conservation model that concretely integrates cultural and environmental sustainability.

6. Discussion

The processes of conserving and adaptively reusing cultural heritage buildings require the development of tailored approaches for each project. The findings from the case of the Aya Payana Church reveal a number of key outcomes regarding the preservation of multi-layered heritage and the promotion of cultural continuity.

6.1. Balancing Restitution and Adaptive Reuse in the Conservation of Multi-Layered Structures

The documentation and analysis conducted at the Aya Payana Church have shown that preserving the distinct values of each historical layer is fundamental to a holistic conservation strategy (Jokilehto, 2017). Systematic documentation of successive interventions and identification of original elements have made it possible to ensure historical continuity during the conservation process (Fielden, 2003).

Moreover, integrating new usage scenarios while preserving the existing spatial configuration enabled the building’s architectural character to be maintained while meeting contemporary needs (Plevoets & Van Cleempoel, 2011). This highlights the necessity of achieving a careful balance between restitution efforts and adaptive reuse strategies in multi-layered heritage structures.

6.2. The Role of the Scent Museum (Kokuhane) in Cultural Continuity

The Kokuhane concept integrates traditional knowledge with contemporary museological practices by placing sensory experience at the center. Focusing on memory and identity construction through the sense of smell, this approach demonstrates how alternative experiential models in the adaptive reuse of historic buildings can enhance cultural continuity (Herz, 2004).

In particular, the inclusion of laboratory and workshop areas has allowed visitors to transition from passive observers to active participants, thereby fostering greater community engagement (Ripp & Rodwell, 2015).

6.3. The Transparent Cafeteria Approach and Its Alignment with Conservation Theory

The transparent cafeteria addition to the building fully complies with international conservation principles, which emphasize that new interventions must be distinguishable from the historic structure (ICOMOS, 1964, Article 9; Australia ICOMOS, 2013). Thanks to its transparent design, the addition both meets new functional needs and preserves the perceptual integrity of the heritage building.

This example illustrates that in the adaptive reuse of similar historic structures, minimal and transparent additions can serve as an effective method of safeguarding architectural values (Rodwell, 2008).

6.4. The Botanical Garden as a Model for Environmental Sustainability

The botanical garden, composed of selected native plant species, has contributed to both visual and olfactory continuity while supporting environmental sustainability (Historic England, 2012).The preference for low-water-consumption and climate-adapted species has reduced maintenance costs and optimized the use of natural resources (Price & Doehne, 2011).

This strategy demonstrates that integrating cultural and environmental sustainability can serve as a model approach for future conservation projects.

6.5. Assessment of Scientific Contribution and Originality

The methodological framework developed in this study provides both theoretical and practical contributions to the conservation and adaptive reuse of multi-layered historical buildings:

Assigning new functions without disrupting historical continuity,

Integrating cultural, economic, and environmental sustainability principles,

Developing a museum concept centered on sensory experience,

Designing nature-based production processes integrated with local flora.

This original approach not only addresses the specific case of the Aya Payana Church but also proposes a replicable model for the conservation and revitalization of other similarly stratified heritage structures.

7. Conclusion

The conservation and adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings require a critical understanding of their historical significance and a context-sensitive strategy for integrating them into contemporary social life. This study, through the case of the Aya Payana Church, illustrates how a heritage structure with a largely preserved physical fabric but a layered functional and symbolic past can be adaptively reused within a sustainable conservation framework that fosters cultural continuity. Through documentation, material analysis, structural assessment, and restitution studies, the building’s historical significance and transformation over time were thoroughly examined. Each intervention was developed in line with internationally recognized principles of minimal intervention, reversibility, and authenticity (ICOMOS, 1964; Australia ICOMOS, 2013; Jokilehto, 2017), ensuring that new uses complement rather than compromise the site’s heritage values.

The adaptive reuse process, realized through the Kokuhane (scent museum) concept, aimed not only at physical preservation but also at strengthening cultural continuity by establishing a sensory connection between the building and collective memory (Herz, 2004; Ripp & Rodwell, 2015).

The integration of a botanical garden and laboratory enabled visitors to engage directly in cultural production processes, transforming the museum from a passive display space into an active learning environment. Additionally, the transparent cafeteria provided a contemporary function that supported continuity of use without compromising the historic silhouette of the site. All intervention and design decisions were guided by the integration of cultural, economic, and environmental sustainability principles.

In conclusion, the conservation and reuse model developed for the Aya Payana Church demonstrates that it is possible to balance both the preservation of historical values and the accommodation of contemporary functional needs in multi-layered cultural heritage buildings. This approach offers a transferable model for similar historic sites and reinforces the idea that cultural heritage can be sustained not only through protection, but through active and meaningful use.

References

- Ashurst, J. Conservation of Ruins. Routledge. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Australia ICOMOS Incorporated. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Binda, L.; Maierhofer, C. (2006, July). Strategies for the assessment of historic masonry structures. In In-situ evaluation of historic wood and masonry structures (NSF/RILEM Workshop), Prague (pp. 37–56).

- Bosiljkov, V.; Uranjek, M.; Žarnić, R.; Bokan-Bosiljkov, V. An integrated diagnostic approach for the assessment of historic masonry structures. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2010, 11(3), 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, P.; Andrews, D.; Blake, B. Metric survey specifications for cultural heritage. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, P. A.; Love, P. E. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Structural Survey 2011, 29(5), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirören News Agency (DHA). 2025. Available online: https://www.dha.com.tr/foto-galeri/aya-baniya-kilisesi-restore-edilerek-koku-atolyesine-donusturulecek-2043723/1 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Douglas, J. Building adaptation. Routledge. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B. Conservation of historic buildings. Routledge. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harita.gov.tr. Available online: https://www.harita.gov.tr/urun/turkiye-mulk-idare-bolumleri-haritasi/189 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Herz, R. A Naturalistic Analysis of Autobiographical Memories Triggered by Olfactory Visual and Auditory Stimuli. Chemical Senses 2004, 29(3), 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Historic England. Practical building conservation: Stone, 1st ed.; Routledge for English Heritage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter). 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. A history of architectural conservation; Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Letellier, R.; Schmid, W.; LeBlanc, F. (2007). Guiding Principles Recording, Documentation, and Information Management for the Conservation of Heritage Places. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, USA, 36–38.

- Matero, F. G. Managing Change: The Role of Documentation and Condition Survey at Mesaverde National Park. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 2003, 42(1), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbaşlı, A. Architectural conservation: Principlesorba and practice; Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive reuse as a strategy towards conservation of cultural heritage: A literature review. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment 2011, 118, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Price, C. A., & Doehne, E. (2011). Stone conservation: an overview of current research.

- Ripp, M., & Rodwell, D. (2015). The geography of urban heritage. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 6(3), 240–276.

- Roca, P.; Cervera, M.; Gariup, G.; Pela’, L. Structural analysis of masonry historical constructions. Classical and advanced approaches. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2010, 17(3), 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, D. (2008). Conservation and sustainability in historic cities. John Wiley & Sons.

- Smith, B. J., & Turkington, A. (Eds.). (2016). Stone decay: its causes and controls. Routledge.

- Stubbs, J. H. (2009). Time Honored: A Global View of Architectural Conservation. Wiley.

- TBDY – Turkish Building Earthquake Code. (2018). Resmi Gazete, (30364), 18 Mart 2018.

- Veldpaus, L.; Pereira Roders, A.; Colenbrander, B. J. F. (2013). Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 4(1), 3–18.

- Watt, D. S. (2025). Building pathology: Principles and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Young, D. (2008). Salt attack and rising damp: A guide to salt damp in historic and older buildings. Heritage Council of NSW; Heritage Victoria; South Australian Department for Environment and Heritage; Adelaide City Council.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).