1. Introduction

Government agencies are supporting the development of drone delivery services through the modernization of airspace use and their support for pilot initiatives. For example, a strategic priority of EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency) is the implementation of “U-space” across member states [

1]. Similarly, in the UK, civil aviation systems are being developed to allow for the integration of more routine drone flights as part of their Airspace Modernisation Strategy [

2]. These developments aim to support the widespread operation of uncrewed aerial services (UAS), from here on referred to as ‘drones’. Existing examples of drone delivery services operating in the Global North are currently small scale. For example, Manna which operates within two suburbs (Blanchardstown, Dublin, Ireland and Pecan Square, Texas, USA), delivers packages of up to 4kg which largely comprise of takeaway food and groceries [

3]; this is alongside examples of various trial services focused on the transportation of medical items such as diagnostic samples, see for example Project CAELUS [

4]. Public acceptance of drone services is a key factor in ensuring their longer-term viability, with push back in response to localised impacts forcing the cessation of services in some places [

5,

6]. Publics are more accepting of the local impacts of drone delivery services where there is potential for environmental or social gain [

7] and promoters place emphasis on these aspects as part of their legitimising strategies [

8]. However, such gains are not always demonstrable and reductions in emissions are limited [

9] or services may create a new type of transport demand [

5]. The use of drones for the transport of medical items is often justified with respect to providing time-savings however the business case and the need for urgency is sometimes questionable [

10].

Perceptions of potential services amongst publics draw heavily on media framings, particularly where there is limited direct experience which can act to perpetuate misconceptions around environmental and social benefits [

11]. Representations are also formed around existing and more familiar drone applications such as photography and warfare with related concerns over privacy and terrorism [

12]. Research framings have acted to conflate various drone applications and as such, understandings of perceptions may relate to a range of applications [

13]. Smith et al (2022) argue that the implications of the use of drones for delivery are very different to those that take place in locations which are largely away from the public domain (e.g. powerline inspection) or represent single events (e.g. photography) [

13]. As such there is a call for research to be specific to drone delivery applications noting that even within this application there are diverse forms of potential services. Moreover, there is a need to recognise the context within which perceptions are formed, including the positioning of the participant with different types of places being valued differently and responses being linked to individual knowledge and values [

14].

Whilst there is a substantial literature on the public acceptance of drones, rather less attention is paid to the governance challenges which these new technologies face, beyond those which act as an immediate impediment to their adoption [

15]. Stilgoe and Mladenovic [

15] suggest that it is critical to step back from the presumption that these technologies are inevitable and so the only relevant questions are about how to ensure acceptance. Instead, they argue that we need to explore the politics of new technologies which means engaging with who wins and loses and who has power to decide [

15,

16]. Fischer suggests that we cannot know the full nature and diversity of issues which different groups will hold as important and the extent to which these “differences become disputes” [

17](p105). It is, therefore, critical to understand how different policy communities might respond to the problem at hand as this will shape their assumptions and routes to engagement with citizens. This paper also considers the differences between policy communities and citizens, and the interaction between the key societal impacts and the approaches to governing drones.

The key questions that this paper sets out to explore are, therefore: 1) What are the key policy dilemmas surrounding the introduction of drones for delivery? 2) How different are those dilemmas between policy communities and citizens; and 3) Do these differences vary across local contexts? To explore this, the study uses the Q-sort methodology which is finding significant application in exploring transport policy dilemmas [

18,

19,

20]. Q-Sort presents participants with a series of statements which are ordered by degree of agreement (and disagreement). Through the relative placement of statements, groups can be clustered together who share similar opinions and which are significantly distinct from other groups. The focus is on establishing clusters of shared viewpoints rather than on establishing differences by means of age or education.

The paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 sets out the approach to Q-Sort and how it was first applied across the policy community and then reduced and applied in three local contexts in the UK.

Section 3 presents the results of the Q-Sort for the policy community and the citizens separately.

Section 4 then discusses the joint implications of the analysis structured by the main research questions set out above. In Section 5 we conclude with a discussion of the implications of the work both for the on-going debates about the introduction of drones for delivery, but also more broadly as a reflection on how we understand the critical dilemmas surrounding uncertain new technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Q-Sort Method Overview

The Q-methodology involves the development of a set of subjective statements which participants are required to sort into levels of agreement (hence the use of the term Q-Sort to describe the application of the method). The research method comes from a tradition which suggests that we cannot objectively know how people perceive a problem, but we can gain insights through the way in which they interact with subjective statements [

21]. However, “Q-method is not a tool designed for reaching consensus; on the contrary it is suited for stimulating heterogeneity in opinions on subjects on which a more or less mature developed debate has evolved” [

19] (p4). Rather, Q-methodology brings together a quantitative interpretation of the response to the set of qualitative statements by clustering similar groups of statements found within the sample using factor analysis [

21]. It is the statements which are found to cluster together which have primacy, with the nature of the respondents associated with each cluster of statements then subject to reflection.

The process for developing a Q-Sort is to build a ‘concourse’ which is a body of text which captures the current state of debates and discussions on a topic. This can be from sources such as newspaper articles, podcasts and government reports. These are then refined using a set of criteria relevant to the study in question (e.g. [

18] used visioning reports to identify relevant terms and [

19] used a systematic review). The refined short list is then turned into statements which the participants in the study can agree or disagree with. The task is then for participants to review the statements quickly and place in three intuitive piles (agree, disagree, neutral/not sure) before placing them on a Q-sort grid (see

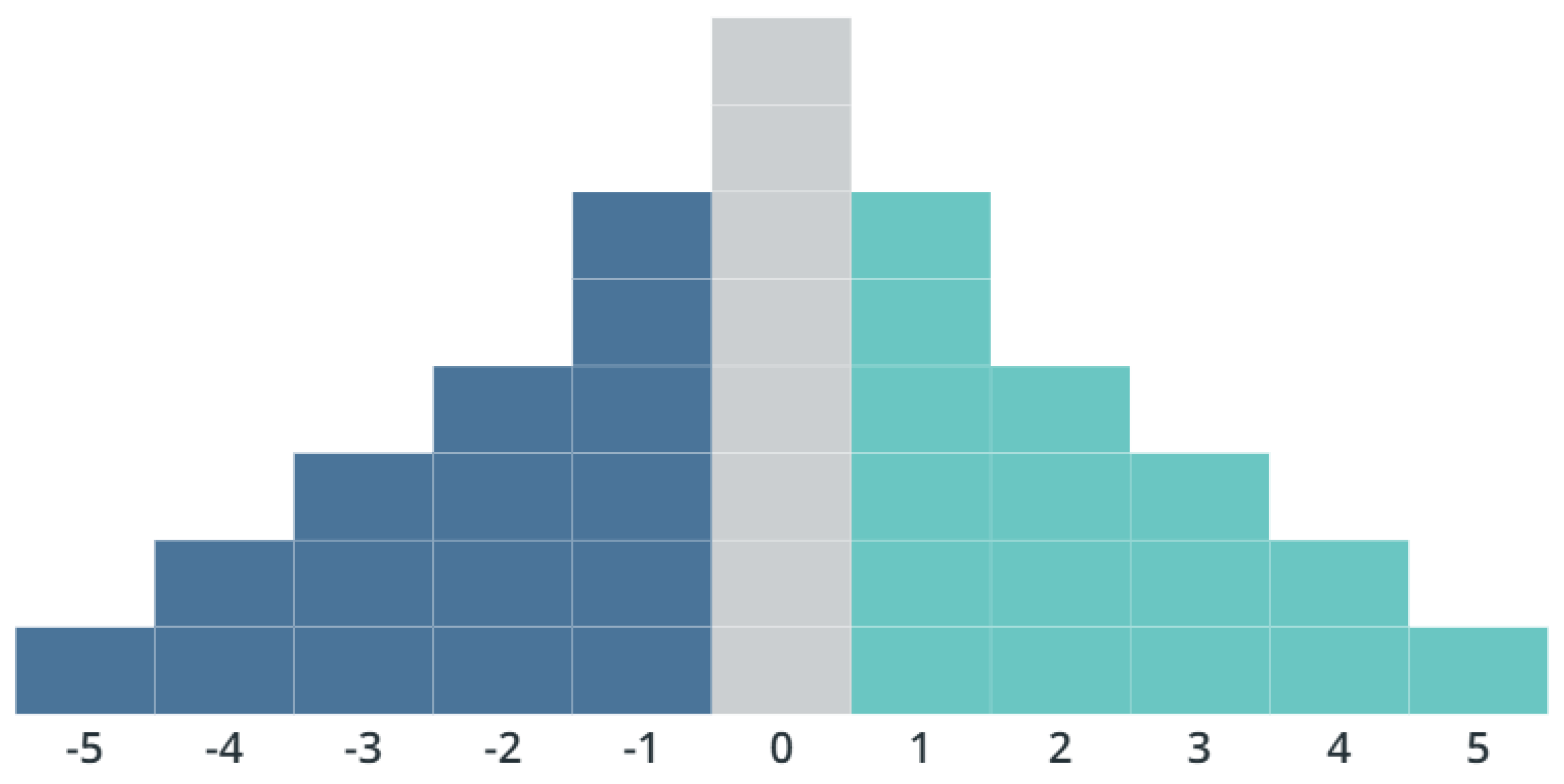

Figure 1 for this study). Fewer options are given at either end of the grid to force choices into the strength of opinion people hold on topics. Whilst the grids often have a numeric value along the scale, the numbers are there to enable the researchers to describe where statements sit along the axis and they have no scalar value analytically. It is also important to note that participants are sorting their statements in relative order. It would, for example, be possible to agree with every statement and still place them on a grid from most agreed with to most disagreed with.

For this research, the team used a commercially available software which provided a robust platform for sending out links to participants. It also enabled us to link the software to the on-line citizen recruitment panel rather than having to specifically programme the Q-Sort within the panel provider’s own in-house platform (

https://qmethodsoftware.com/). Further details about our specific application of the methods is provided below.

2.2. Recruitment

We adopted a two-staged approach to the Q-Sort in this study. The first stage involved the recruitment of a purposive sample of expert stakeholders (n = 53 – hereafter referred to as ‘experts’ although this is in the field of transport planning and logistics rather than specifically drone experts) who undertook a Q-Sort on a set of 40 statements. A researcher was available on-line to answer any queries about how the software worked. This Q-Sort was used to map out the most pertinent policy dilemmas and groupings of opinions in the expert community. This data collection occurred over the time period December 2022 to June 2023. All of the Q-Sorts were completed using the on-line software. The experts could be classified into the following groups:

Government (19)

Consultant (15)

Academic (5)

Industry (4)

NGO (8)

The second set of Q-Sorts was to be conducted with members of the public using the same on-line software. However, it was felt that the practical challenge of sorting 40 statements was too high in unfamiliar software (and there was no scope for a researcher to be available for help as in the expert work) and so a reduced form Q-Sort was established of 25 statements. In order to select the statements which should be sorted by citizens, the research team analysed the outcomes of the expert Q-Sort and removed statements which were not important in assigning experts to different clusters. Attention was also paid to ensuring a suitable coverage of themes and a balance of positive and negative statements to avoid biasing the respondents. Recruitment for the citizen Q-Sort was undertaken in three places (Coventry (n=206), parts of Cornwall (n=203) and Bournemouth and surrounding areas (n=201). Trials of drone technology were being undertaken in both Falmouth (a town in Cornwall in the selected area) and Coventry, and so it was felt that at least some respondents would have familiarity with the idea of drones for deliveries. The sites also represented different settings with Coventry predominantly urban, Cornwall predominantly rural and Bournemouth containing a mix of settings.

2.3. Developing the Q-Sort Question Set

Whilst the topic of drones is commonplace within news, media, and research, the use case for drones for delivery purposes is an emergent issue with limited attention or information beyond those already working on it. There was an initial wide scope for all literature—including news and media—related to drones but little to none engaged with the question of drones as a logistics technology yet to come. Therefore, literature informing the development of the Q-Sort concourse was deliberately restricted to private and public sector (policy) reports dealing with expanding the case for UTMs (eg Dft’s Advancing airborne autonomy 2022), future transport more general and/or the changing demands of urban space and how best to regulate it (e.g. TfL’s Parking and Loading Legally ND).

Whilst there was no year constraint on the document search, the search yielded reports and documents from approximately 2019-2023, reflecting the relative nascence of the topic. Concurrent to the policy and document search was that of scholarly research that focused on the question of regulating transport and/or logistic technologies yet to come. Seven government reports and two academic papers dealing with drones and/or the regulation of urban space more generally were chosen to help build the stet of statements used within the concourse. Discourse analysis was used to identify initial thematic categories that spoke to the justification of introducing drones into the last mile logics arena OR categories that represented issues around regulatory concerns and issues. These were: Actors, Automation, Climate, Congestion, Cost, Data, Decision-making, Demand, Efficiency, Innovation, and Regulation. These categories were subsequently revisited and combined to Environment, Regulation, Innovation, Logistics, Safety, and Society with the aim of providing a balance of questions in each theme. These then had to be turned into question statements which people could agree or disagree with.

Positive and negative versions of questions which matched to the original set of statements were developed to produce a balance of positive and negative statements for each theme (if you liked the environment you would have to disagree with some statements and agree with others). The framing of statements also paid attention to whether it was appropriate to use absolutes (e.g. “is”) or conditional statements (e.g. “should be”). For example, a statement describing the problems of a slow regulatory environment in one policy report was “flipped” and simplified into the following statement:

The approach to regulating drone use is too fast.

The table was iterated upon six times by the research team, with a few mock Q-sorts with colleagues outside the project to find a total of 40 statements that represented a balance of sentiment and thematic.

Table 1 shows the full battery of 40 statements with the reduced form set used in the citizen Q-sort marked with an asterisk.

2.4. Operationalising the Q-Sort

The Q-Sort was programmed into the Q Methods Software (

https://qmethodsoftware.com/). Participants first sorted the statements into three piles of Agree, Disagree and Neutral and were instructed to do this intuitively as they would have a chance to revisit their relative positions when placing the cards on the sort. They then placed the cards on a Q-Sort grid (shown in

Figure 1), Participants were instructed that the right-hand side of the chart indicated strength of agreement and the left, strength of disagreement. Cards were placed and then adjusted until the participants were happy that this reflected a spectrum from most agreed with to most disagreed with. It is important to note that the numeric values have no significance in the analysis but simply allow people to see that they are placing something as more or less important than the next statement. Participants are presumed to be indifferent between items stacked vertically on the grid.

For the citizen groups, the reduced form set of questions were used. Participants were recruited by YouGov to match the demographic characteristics of the areas and, following some initial screening questions were sent to the external Q Methods Software package to complete the task. The average time for completion of the expert/stakeholder surveys was 11m29s for the expert/stakeholder group and between 5m28s (Bournemouth) and 6m30s (Cornwall) for the citizens, reflecting the smaller sort and the more limited engagement with institutional remits and planning logics and a more intuitive approach to responding.

3. Results

This section first reports the results from the expert/stakeholder surveys. The results from the citizen data set are then analysed by area.

3.1. Expert/Stakeholder Q-Sort

Q-method uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify the components that enable the matching of similar response grids and, which therefore allow clustering of response groups. PCA produces:

Extracted factors were rotated using the Varimax method rather than by hand as there was no theoretical basis on which to base a by hand rotation and this provides a set of orthogonal factors. In line with Tsigdinos et al., (2022) [

19] we have identified the number of extracted factors by ensuring the following two conditions are met:

- The Eigenvalue of each factor should be >1

- At least 2 Q-sorts should significantly load onto each factor

The task in deciding which solution is preferable is to balance selecting a relatively low number of factors which describes the maximum amount of variance. The hyperplane analysis function in the QMethods software was used to help determine the final solution. Hyperplane seeks to identify solutions where there is one high factor loading and numerous low factor loadings and higher values of hyperplane percentage are indicative of simpler solutions [

22]. Different numbers of factors were explored and the extent to which the conditions set out above were met dictated if they were considered further. For those meeting both conditions, the hyperplane percentage was analysed.

Table 2 shows the Table of Eigenvalues and

Table 3 the matrix of factor loadings for the five factors.

The analysis suggests that the hyperplane percentage drops off at 4 factors and so this means the 6 and 5 factor rotations perform better than the 4 factor rotation. As more sorts loaded to each factor in the 5 factor solution and there were fewer unassigned sorts, the 5 factor solution was taken forward and the results for this are presented below.

The results from the 5 factor sort are shown in Table 4. The Q value indicates where on the sort grid the statement was placed for each cluster and the significant z values show which statements were significantly different for that particular cluster. The next step is a narrative sense making exercise which looks at the most and least important statements for each group and also the statistically distinguishing statements. This leads to the following five classifications:

What’s the question? – This group takes a macro planning approach asking how we can know whether drones for delivery are necessary in the absence of a national freight strategy. Yes, home deliveries are a problem but are drones the answer relative to other interventions. Drones should bring carbon benefits and not exclude some groups. There are some risks and whilst this group is not anti-drone it is far from clear that the benefits outweigh the risks. This is not an economic growth question for this group.

Drone Advocates – This group sees drones as an economic growth opportunity and a solution to an already under pressure set of delivery options. Regulation is going too slow, local authorities need to have minimal involvement, and the public does not need to be asked about how this is introduced. There are some risks like terrorism, but trials are the way to demonstrate how this will all work.

Drones are a problem – This group does not want drones for deliveries and does not see them as inevitable. Our towns and cities are already too busy to safely accommodate them, there is no case for economic growth and the Government should not be promoting their use. There are concerns about terrorism and privacy, and they must demonstrate their carbon benefits.

Drones are coming so do it right – This group sees drones as definitely part of the future so there is a need to engage with them and plan responsibly for their introduction. Rising home deliveries is a problem and maybe this is part of the answer? However, there are concerns over terrorism, disruption to wildlife and impacts on vulnerable people. Perhaps we need to restrict what times they operate at. Trials are part of the way forward.

Just the details – This group has some similarities to the previous group in that they see drones as being inevitable but are less concerned over some of the risks like terrorism. Whilst appearing to be more laissez-faire, they do still prioritise restricting use over schools and people’s houses. They support trials as a way forward for working out what to do.

Q-sort focuses on clustering opinions rather than clustering by socio-demographics. The expert group is also small in size. The main differences an analysis of respondents shows is that, unsurprisingly those in the drone industry or who are currently promoting drone trials in their local area fall into the advocates category. However, transport planning professionals fall across all of the different categories. It was, however, extremely difficult to recruit stakeholders to respond about drones, with many suggesting that this was not part of their remit. The gap between advocates and the wider professional body presents real risks in marginalizing issues which ultimately will matter to deployment prospects. This suggests a need for much better, broader and more open engagement around new technologies such as delivery drones.

Table 4.

Z Scores and Sort Values for Expert/Stakeholder Sort.

Table 4.

Z Scores and Sort Values for Expert/Stakeholder Sort.

| |

|

What’s the Question |

Drone

Advocates

|

Drones are a Problem |

Drones are Coming Do it Right |

Just the Details |

| ID |

Statement |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

| 15 |

A national strategy for managing growth in deliveries is needed before the case for delivery drones can be considered |

5

|

2.125 * |

0

|

-0.193 |

1

|

0.571 |

0

|

-0.286 |

0

|

0.122 |

| 14 |

The rising number of home deliveries is a problem |

4

|

1.947 * |

-4

|

-1.717 |

-1

|

-0.343 * |

3

|

1.488 * |

-2

|

-1.183 |

| 32 |

Avoiding negative impacts on vulnerable citizens should be key to whether or not new technologies are approved |

4

|

1.455 |

-1

|

-0.762 * |

1

|

0.708 |

3

|

1.434 |

2

|

0.769 |

| 20 |

Local authorities do not currently have the capacity and skills to regulate drones |

3

|

1.444 |

5

|

2.048 * |

1

|

0.461 |

2

|

1.276 |

0

|

0.294 |

| 21 |

Local authorities should have a role to play in the regulation of the use of drones for delivery in their area |

3

|

1.366 |

0

|

-0.204 |

2

|

0.961 |

2

|

1.190 |

0

|

0.041 |

| 2 |

Emissions from the manufacture of drones and batteries must be considered in assessing their impacts |

3

|

1.206 |

2

|

0.558 |

3

|

1.149 |

3

|

1.308 |

3

|

1.184 |

| 17 |

Companies must better organise their deliveries to combat the wastefulness of multiple home deliveries |

2

|

1.159 |

-3

|

-1.175 * |

4

|

1.455 |

2

|

1.193 |

3

|

1.051 |

| 36 |

Drones used by the emergency services should be treated differently to drones for delivery by retail companies |

2

|

1.022 |

4

|

2.012 |

5

|

1.585 |

1

|

0.839 |

3

|

1.421 |

| 34 |

Small scale drone trials are important to understand the overall impacts of drones on society |

2

|

0.938 |

3

|

1.554 |

0

|

0.313 * |

4

|

1.515 |

2

|

0.922 |

| 8 |

Government has a duty to protect the tranquility of less developed areas |

2

|

0.732 |

1

|

0.488 |

0

|

0.181 |

1

|

0.555 |

1

|

0.376 |

| 30 |

People have a right to limit drone flights over their house |

1

|

0.551 |

0

|

-0.220 |

0

|

0.355 |

-1

|

-0.650 |

2

|

1.023 |

| 3 |

To minimise noise and disruption, drones will need to operate within fixed permissible times for delivery |

1

|

0.496 |

-2

|

-0.955 * |

0

|

-0.040 * |

4

|

1.622 * |

1

|

0.734 |

| 22 |

Leisure drone users need different regulation to those operating drones for delivery |

1

|

0.438 |

3

|

1.028 |

0

|

0.183 |

2

|

1.142 |

4

|

1.583 |

| 6 |

Drones will negatively impact overall noise pollution |

1

|

0.402 |

1

|

0.259 |

2

|

0.778 |

1

|

0.605 |

0

|

0.058 |

| 25 |

Delivery drones should not be allowed to fly over schools during the school day |

1

|

0.250 |

-2

|

-0.968 * |

1

|

0.436 |

0

|

0.095 |

5

|

2.038 * |

| 33 |

Delivery drones will be more useful for rural communities than urban communities |

1

|

0.140 * |

4

|

1.807 |

2

|

0.719 * |

-2

|

-0.749 * |

4

|

1.479 |

| 16 |

Drones should only be allowed to deliver some types of products to people's homes |

0

|

0.108 |

2

|

0.924 |

3

|

1.269 |

1

|

0.295 |

1

|

0.537 |

| 19 |

Airspace is too complex for management at a local scale |

0

|

0.107 |

2

|

0.625 |

-1

|

-0.193 |

1

|

0.219 |

-4

|

-1.381 * |

| 40 |

The introduction of drones for delivery in the UK is inevitable |

0

|

0.101 |

-1

|

-0.269 |

-3

|

-1.306 * |

1

|

0.172 |

2

|

1.047 * |

| 35 |

The public cannot understand how drones for deliveries will impact them |

0

|

0.041 * |

3

|

1.731 * |

-1

|

-0.643 |

-1

|

-0.657 |

-4

|

-1.561 * |

| 13 |

Government should be planning for the introduction of air taxis |

0

|

-0.011 * |

1

|

0.538 |

-4

|

-2.190 * |

-3

|

-1.253 * |

1

|

0.730 |

| 31 |

Delivery drones are a solution looking for a problem |

0

|

-0.219 |

0

|

-0.126 |

1

|

0.693 |

-5

|

-1.695 * |

0

|

0.259 |

| 23 |

Drones for deliveries should be allowed to land in people's gardens |

0

|

-0.229 |

1

|

0.553 |

-1

|

-0.448 |

0

|

-0.152 |

1

|

0.398 |

| 9 |

The approach to regulating drone use is too fast |

0

|

-0.281 |

-5

|

-2.044 * |

0

|

0.087 |

-1

|

-0.669 |

-3

|

-1.305 * |

| 24 |

Towns and cities are too busy for delivery drones to safely operate |

-1

|

-0.358 |

-2

|

-0.850 |

3

|

1.381 * |

-4

|

-1.500 * |

-1

|

-0.296 |

| 18 |

Robot delivery carts are more suitable for home deliveries than drones |

-1

|

-0.422 |

1

|

0.425 * |

-1

|

-0.190 |

-2

|

-0.886 |

-1

|

-0.693 |

| 39 |

Social acceptance of drones for deliveries will increase as their use becomes more commonplace |

-1

|

-0.443 |

0

|

-0.045 |

2

|

0.720 |

5

|

1.867 * |

1

|

0.354 |

| 29 |

Public taxes should not be funding drone development trials |

-1

|

-0.451 |

-1

|

-0.736 |

0

|

0.191 * |

0

|

-0.490 |

-2

|

-1.243 |

| 7 |

Innovation in drone technology for deliveries does not have enough societal benefit to make it worth it |

-1

|

-0.556 |

-3

|

-1.231 |

0

|

-0.034 * |

-2

|

-0.756 |

-2

|

-1.165 |

| 26 |

Drones should not be restricted on safety grounds so long as they are safer than vans |

-1

|

-0.711 |

-1

|

-0.254 |

-2

|

-0.917 |

0

|

0.141 |

-1

|

-0.474 |

| 37 |

The public should not be asked to decide if drones for logistics are desirable |

-2

|

-0.785 |

0

|

-0.091 |

-2

|

-0.992 |

0

|

-0.473 |

-1

|

-0.434 |

| 10 |

Increasing drone use is essential to the growth of the UK economy |

-2

|

-0.954 * |

-1

|

-0.263 |

-5

|

-2.278 * |

-1

|

-0.511 |

0

|

0.083 |

| 28 |

Camera technology on drones is not a significant privacy issue |

-2

|

-0.982 |

0

|

-0.078 * |

-4

|

-1.696 |

-4

|

-1.424 |

-3

|

-1.265 |

| 11 |

It is up to businesses to decide if drones are going to be useful |

-2

|

-1.042 |

0

|

0.232 |

-2

|

-0.810 |

0

|

0.030 |

0

|

0.119 |

| 12 |

Government should not be acting to facilitate commerical drone use |

-3

|

-1.064 |

-2

|

-0.991 |

4

|

1.500 * |

0

|

-0.477 |

-2

|

-1.071 |

| 38 |

It is okay if some groups in society are not able to benefit from drone use for delivery |

-3

|

-1.186 * |

2

|

0.686 |

1

|

0.541 |

-1

|

-0.514 * |

0

|

0.217 |

| 27 |

Drones pose no additional risk from terrorism |

-3

|

-1.323 |

-3

|

-1.014 |

-3

|

-1.214 |

-1

|

-0.668 |

-3

|

-1.261 |

| 5 |

Regulation of drones should be the same in rural and urban areas |

-4

|

-1.342 |

-4

|

-1.233 |

-2

|

-0.938 |

-2

|

-0.740 |

-1

|

-0.972 |

| 4 |

The impacts of drones on wildlife are not significant |

-4

|

-1.492 |

1

|

0.329 * |

-1

|

-0.717 |

-3

|

-1.071 |

-1

|

-0.951 |

| 1 |

Drones should not need to demonstrate carbon benefits before being introduced |

-5

|

-2.181 * |

-1

|

-0.380 * |

-3

|

-1.285 |

-3

|

-1.365 |

-5

|

-1.583 |

There were however a series of consensus statements which suggest there are some issues around which all parties are either agreed that something needs to be done or where it is not an issue. There is some agreement that this will negatively impact on noise pollution and that the tranquility of less well-developed areas needs protecting. There is general weak agreement that urban and rural areas should be regulated similarly. It is uncontroversial that the emergency services are a different case to deliveries and should have their own rules and also that the emissions from drone manufacture should be considered as part of impact assessments.

3.2. Citizen Q-Sort

The same analytical procedures were undertaken for the three sites as for the expert/stakeholder data to determine the number and nature of the clusters in each area. The results of the factor rotations and hyperplane analysis are shown in Table ZZ.

Table 4.

Factor Rotations, Exclusions and Hyperplane Analysis.

Table 4.

Factor Rotations, Exclusions and Hyperplane Analysis.

| Factors |

Minimum Sorts assigned to factor |

Number of sorts unassigned |

Hyperplane |

| Coventry (n=206) |

| 8 Factor Rotation |

2 (factor 8) |

105 (51%) |

34.1% |

| 7 Factor Rotation |

6 (factor 3,5,6) |

96 (47%) |

31.2% |

| 6 Factor Rotation |

7 (factor 3) |

78 (38%) |

29.1% |

| 5 Factor Rotation |

7 (factor 4) |

69 (34%) |

27.8% |

| 4 Factor Rotation |

12 (factor 3) |

73 (35%) |

24.0% |

| Cornwall (n=203) |

| 8 Factor Rotation |

2 (factor 5) |

107 (52%) |

32.7% |

| 7 Factor Rotation |

5 (factor 3) |

83 (41%) |

32.5% |

| 6 Factor Rotation |

6 (factor 3) |

78 (38%) |

30.3% |

| 5 Factor Rotation |

8 (factor 3,4) |

69 (34%) |

28.2% |

| 4 Factor Rotation |

10 (factor 4) |

71 (35%) |

22.6% |

| Bournemouth (n=201) |

| 8 Factor Rotation |

3 (factor 4,7) |

81 (40%) |

33.9% |

| 7 Factor Rotation |

3 (factor 7) |

66 (33%) |

32.6% |

| 6 Factor Rotation |

8 (factor 5) |

46 (23%) |

31.5% |

| 5 Factor Rotation |

10 (factor 3) |

43 (21%) |

30.0% |

| 4 Factor Rotation |

9 (factor 3) |

48 (24%) |

27.6% |

For each of the sites, a six-factor rotation achieved the best balance of assigning sorts and the hyperplane values, although a fix factor rotation might also have been selected. In each of the sites, of the six factors, one factor dominated the clustering (as indicated by the number of Sorts assigned to each factor in Table BB) and this group shared similar characteristics in terms of key statements across the three sites. Results for all of the sites are available in additional materials, but for simplicity, the results for the Coventry Sort are presented below in Table YY and a narrative comparison of differences found in the other areas is provided. However, given the dominance and similarity of the first factor and the sizes of the allocations of Q-Sorts to other factors it is possible that some of these differences would disappear with an even larger sample.

Table 5.

Sorts assigned to each factor by area.

Table 5.

Sorts assigned to each factor by area.

| Area |

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

Factor 5 |

Factor 6 |

| Coventry |

78 |

15 |

7 |

12 |

8 |

8 |

| Cornwall |

83 |

11 |

6 |

11 |

7 |

7 |

| Bournemouth |

101 |

16 |

9 |

10 |

8 |

11 |

The dominant group are described as Drone Sceptics. Drone Sceptics worry about privacy, terrorism risks, impacts on wildlife, carbon impacts and strongly believe that there should be limits to where they are used. Whilst they tolerate the idea of emergency services being treated differently, they do not see this as part of an economic growth mission and do not support the government part funding the development of drones for delivery.

The Drone Positive group, whilst recognizing some of the same risks as the Drone Sceptics see these as less important. They think it is up to businesses to decide if they are useful and would be happy for any type of goods to be delivered to people’s houses. They don’t think towns and cities are too busy for drones.

Tranquility Matters, as the name suggests are most sensitive to noise and surveillance risks with preferences for people to be able to limit the right to fly over their property, over schools and to protect less developed areas. They don’t see the rising number of home deliveries as a problem and would rather not have drones instead of vans irrespective of whether or not they were safer.

Libertarian Accepters do not believe that the public should be asked about the introduction of drones nor that local authorities should have much of a say in their regulation. Whilst they are concerned about terrorism they do not hold strong views that the introduction of drones should have limits placed on them or that there is a need to be concerned about vulnerable citizens or wildlife.

Maybe Elsewhere suggest many of the concerns of the Drone Sceptics but feel that limits can be put on when they can be used and that towns and cities are too busy for them. They think they will be most useful for rural areas, even though the Government should protect tranquil areas.

Slowly Slowly see a significant role for Government in managing the introduction of drones. They support the use of taxes to fund trials, think local authorities should have a say as well as the public, although they also think there is limited understanding. They are not so concerned about wildlife and privacy but do worry about terrorism risk.

The groups which emerged in Cornwall and Bournemouth were similar with a slightly different set of priorities over rights and regulation. Interestingly, there was no Tranquility Matters group in either place despite the more rural and coastal nature of these two sites. This might reflect concerns of those living in a bigger city where noise is already felt to be an issue. There was also no Drone Positive group in Cornwall, whereas there was in Bournemouth. Whilst the study had initially imagined that it would identify a range of place-based differences, because the vast majority of respondents sorted onto a Drone Sceptic cluster means that the numbers of people which are being compared between groups in these other clusters is too small for more than a short narrative reflection.

Table 6.

Z Scores and Sort Values for Citizen Sort – Coventry.

Table 6.

Z Scores and Sort Values for Citizen Sort – Coventry.

| |

|

Drone Sceptic |

Drone

Positive

|

Tranquility Matters |

Libertarian Accepters |

Maybe

Elsewhere |

Slowly Slowly |

| ID |

Statement |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

Q |

Z Score |

| 23 |

Drones used by the emergency services should be treated differently to drones for delivery by retail companies |

4 |

1.401 |

4 |

2.195 * |

-2 |

-0.665 * |

3 |

1.176 |

2 |

0.778 |

2 |

1.290 |

| 19 |

People have a right to limit drone flights over their house |

3 |

1.215 |

0 |

-0.226 |

3 |

1.320 |

-1 |

-0.802 |

0 |

0.042 |

-1 |

-0.675 |

| 18 |

Public taxes should not be funding drone development trials |

3 |

1.113 |

-2 |

-1.084 * |

0 |

-0.283 |

2 |

1.035 |

0 |

-0.228 |

-4 |

-1.751* |

| 14 |

Delivery drones should not be allowed to fly over schools during the school day |

2 |

1.101 |

0 |

0.067 * |

4 |

1.588 |

1 |

0.817 |

-3 |

-1.256* |

3 |

1.351 |

| 2 |

To minimise noise and disruption, drones will need to operate within fixed permissible times for delivery |

2 |

0.962 |

2 |

0.763 |

1 |

0.597 |

2 |

0.862 |

3 |

1.410 * |

-1 |

-0.544 * |

| 11 |

Local authorities should have a role to play in the regulation of the use of drones for delivery in their area |

2 |

0.929 |

2 |

0.825 |

2 |

0.969 |

-1 |

-0.763 * |

0 |

-0.009 * |

3 |

1.434 |

| 10 |

Companies must better organise their deliveries to combat the wastefulness of multiple home deliveries |

1 |

0.867 |

3 |

1.633 * |

-1 |

-0.485 |

1 |

0.400 |

-1 |

-0.254 |

1 |

0.545 |

| 20 |

Avoiding negative impacts on vulnerable citizens should be key to whether or not new technologies are approved |

1 |

0.812 |

0 |

-0.256 |

2 |

0.876 |

-2 |

-0.855 |

0 |

-0.164 |

-2 |

-0.821 |

| 5 |

Government has a duty to protect the tranquility of less developed areas |

1 |

0.708 |

1 |

0.742 |

3 |

1.224 * |

0 |

-0.210 |

4 |

2.043 * |

0 |

0.004 |

| 13 |

Towns and cities are too busy for delivery drones to safely operate |

1 |

0.693 |

-3 |

-1.490 |

-1 |

-0.537 * |

0 |

0.063 * |

2 |

0.916 |

-2 |

-1.161 |

| 8 |

The rising number of home deliveries is a problem |

0 |

0.482 * |

-1 |

-0.831 |

-4 |

-2.327 * |

-3 |

-1.331 * |

-1 |

-0.590 |

2 |

0.989 * |

| 9 |

Drones should only be allowed to deliver some types of products to people's homes |

0 |

0.398 |

-4 |

-1.754 * |

0 |

0.359 |

1 |

0.520 |

1 |

0.216 |

4 |

2.024 * |

| 21 |

Delivery drones will be more useful for rural communities than urban communities |

0 |

0.214 |

1 |

0.263 |

-2 |

-0.618 * |

0 |

0.210 |

3 |

1.686* |

1 |

0.163 |

| 4 |

Regulation of drones should be the same in rural and urban areas |

0 |

0.007 |

-1 |

-0.296 |

2 |

1.172 * |

0 |

-0.111 |

-4 |

-1.990* |

1 |

0.332 |

| 12 |

Drones for deliveries should be allowed to land in people's gardens |

0 |

-0.149 |

3 |

1.257 * |

0 |

-0.308 |

-1 |

-0.420 |

0 |

-0.235 |

0 |

0.118 |

| 22 |

The public cannot understand how drones for deliveries will impact them |

-1 |

-0.279 * |

-3 |

-1.193 |

1 |

0.681 |

-2 |

-0.915 |

2 |

0.927 |

2 |

1.283 |

| 25 |

It is okay if some groups in society are not able to benefit from drone use for delivery |

-1 |

-0.616 |

0 |

-0.028 |

0 |

-0.364 |

2 |

0.980 * |

-1 |

-0.339 |

-1 |

-0.461 |

| 15 |

Drones should not be restricted on safety grounds so long as they are safer than vans |

-1 |

-0.743 |

0 |

-0.024 |

-3 |

-1.853 * |

-2 |

-0.806 |

-1 |

-0.251 |

-1 |

-0.453 |

| 7 |

It is up to businesses to decide if drones are going to be useful |

-1 |

-0.961 |

2 |

1.230 * |

0 |

0.304 |

0 |

0.080 |

-2 |

-0.832 |

-2 |

-0.757 |

| 6 |

Increasing drone use is essential to the growth of the UK economy |

-2 |

-0.964 |

1 |

0.662 |

-2 |

-1.025 |

-1 |

-0.545 |

1 |

0.726 |

0 |

-0.126 |

| 24 |

The public should not be asked to decide if drones for logistics are desirable |

-2 |

-1.164 |

1 |

0.318 |

1 |

0.684 |

3 |

1.428 * |

1 |

0.705 |

-3 |

-1.436 |

| 1 |

Drones should not need to demonstrate carbon benefits before being introduced |

-2 |

-1.171 |

-1 |

-0.357 |

-3 |

-1.108 |

4 |

2.168 * |

1 |

0.328* |

0 |

-0.257 |

| 3 |

The impacts of drones on wildlife are not significant |

-3 |

1.516 * |

-2 |

-0.945 |

1 |

0.686 |

1 |

0.461 |

-2 |

-1.066 |

0 |

-0.209 * |

| 16 |

Drones pose no additional risk from terrorism |

-3 |

-1.604 |

-2 |

-0.965 * |

-1 |

-0.480 * |

-4 |

-1.909 |

-3 |

-1.545 |

-3 |

-1.410 |

| 17 |

Camera technology on drones is not a significant privacy issue |

-4 |

-1.736 |

-1 |

-0.505 |

-1 |

-0.408 |

-3 |

-1.534 |

-2 |

-1.017* |

1 |

0.530 * |

4. Discussion

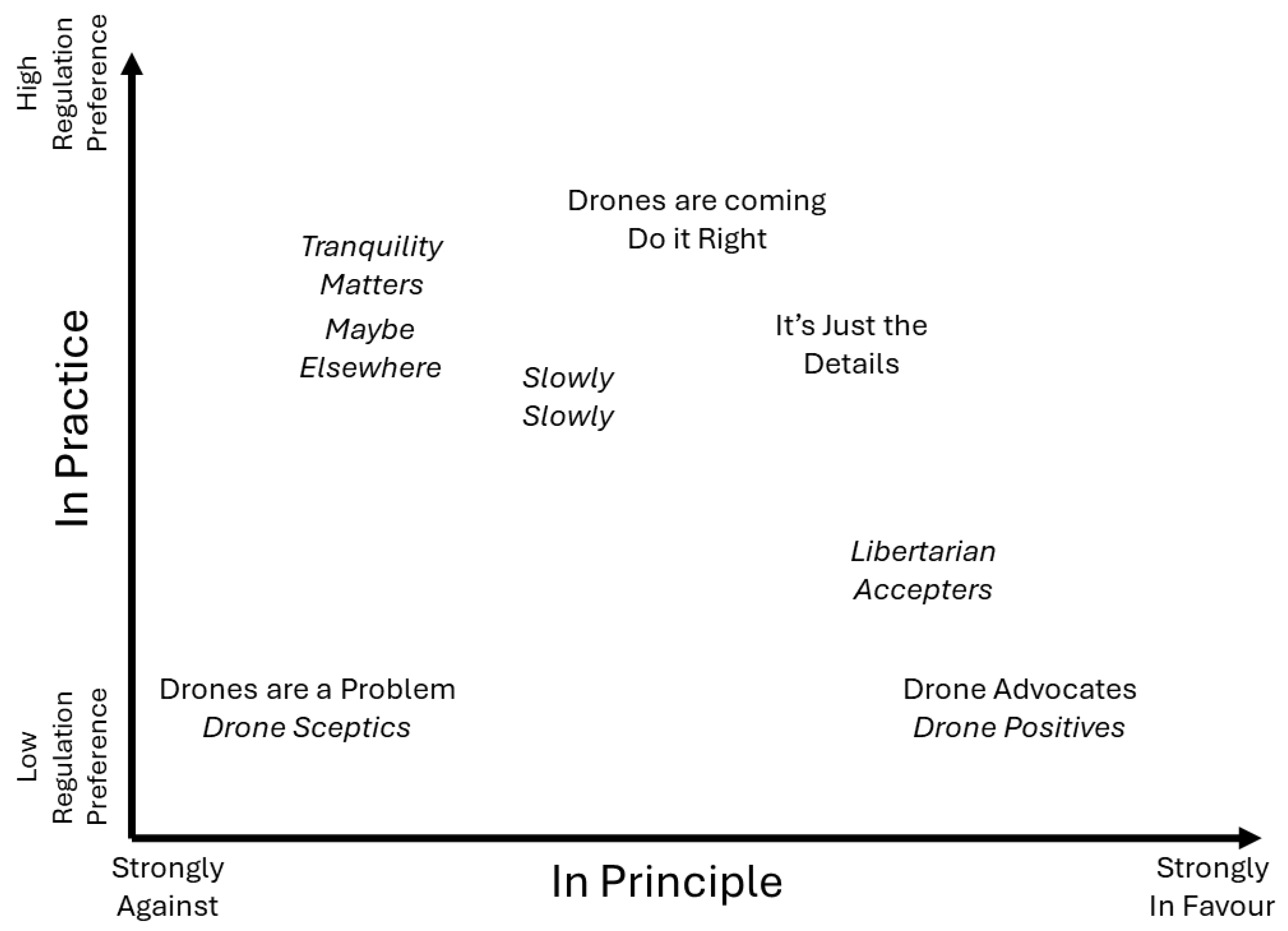

The first research question which the paper set out to answer is what the key policy dilemma’s were around the introduction of drones for delivery. Taking all of the data together, there seems to be two sets of concerns which interact in ways which could shape the nature of the responses that emerge. These could be seen to be the extent to which a group agrees with the idea of drones in principle and the extent to which they consider drones to be manageable in practice. This is shown in

Figure 2 where groups from the stakeholder and citizen groups are placed across the axes in an indicative manner. The Figure reflects the clusters which show that those groups who are staunch advocates of drones believe that there should be very few barriers put in the way to get things moving. Whilst they might tolerate discussions on regulation, these are of low salience in their debates about what should happen.

By contrast, the groups who are sceptical of drones and do not like them in principle do not prioritise topics around how to regulate them, as this could perhaps be seen to acknowledge their possibility. We see no groups placed in the very top left or top right of the chart. No groups are strongly in favour of drones and want high regulation. The closest group is the expert/stakeholders who see the need to manage drones as inevitable and so will seek to regulate in the ways which achieve best overall outcomes. No group dislikes drones so much that they also prioritise regulation but the closest to this are citizen groups who focus on tranquility issues and who suggest that drones might be OK but their wider response set also implies that this OK might be somewhere other than their area. There are other nuances in play, with for example, the Libertarian Accepters being less keen on drones per se than the advocates, but not being particularly supportive of regulatory intervention. It is important to see the chart as a useful heuristic to think about different types of dilemma and how this intersects with the wider perspectives of the clusters of respondents. It is useful to reflect this back on the literature and earlier discussion on asking questions of acceptance. Are people responding about their views on drones or their views on drones in the context of some assumption about how they might be managed? This further contributes to the debate around the utility of the predominant approach to understanding “technology acceptance” [Smith paper]

The second research question asked what the differences were between expert/stakeholders and citizens. In many respects both groups showed similar clusters of concerns. However, there are also important differences to consider. First, there is a dominance of the Drone Sceptics in the general population who have real concerns over privacy, terrorism, surveillance, wildlife intrusion and wider environmental impacts. Whilst this group existed amongst the expert/stakeholder group it was not dominant. It is far from clear, therefore, that the case which appears to be a ‘no-brainer’ to the parts of the expert policy community that is driving innovation in drone delivery is made across society, and glossing over these differences in views is potentially storing up problems for implementation. There is one group which exists in the expert/stakeholder community which is absent from the citizen groups which is “What is the problem?”. This group is not clear what the problem is that drones are supposed to solve nor does it understand how we can think about whether or not drones should be used in the absence of a basic national freight policy framework. The absence of this group could reflect the simpler Q-Sort framework that was presented to citizens but it also talks very directly to strategic planning logics which would be expected to be strong in policy communities [

23].

The final research question asked whether these concerns varied across local contexts. Whilst there were differences, the key finding is that the drone sceptic groups dominated in each of the places. Further research in the wider project from which this study has emerged has established that people respond about impacts in the context of where they live – but that this may not necessarily neatly divide along urban-rural lines [

14]. However, whilst noise might be quite place specific, some of these concerns seem less likely to have place-specific characteristics. For example, attitudes towards regulation, risk [

24] and the role of government seem less embedded in place. We suggest that this remains an area for further work as part of a general call for greater attention to be paid to contextualizing work on how we understand the potential impacts of new technologies [

14,

25].

This study is novel in both comparing the dilemmas around the introductions of drones for delivery between experts and citizens and also across places using the Q-Sort method. We see its key strengths as a way of breaking down the issues of concern to enable those tasked with governing the introduction of new technologies to have more nuanced approach. Q-Sort does not focus on what proportion agree with a specific question but instead shows how sets of priorities or issues fit together and, in this case, has highlighted the mismatch in scale between citizen sceptics and the expert community driving the case for drones forward. Whilst further work can be done to understand whether there are any demographic differences between groups with larger samples, the clustering work suggested that their responses seem to be shaped by a particular social representation of drones as a risk to various aspects of their lives coupled with their attitudes to innovation and the role of government. The narrative of growth opportunities for the economy is not a feature of public concerns and we suggest that if drones are to play a role in our future logistics systems then much greater attention needs to be paid to the range of important practical concerns which are at large, both in principle and in practice. It is also important to consider that drones are just one of many different future pathways for last-mile logistics and by no-means a universal solution [

26]

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Greg Marsden. and Morgan Campbell.; methodology, Greg Marsden and Morgan Campbell.; software, Morgan Campbell.; formal analysis, Greg Marsden.; Recruitment, Morgan Campbell; data curation, Greg Marsden and Morgan Campbell.; writing—original draft preparation, Greg Marsden.; literature review; Greg Marsden, Morgan Campbell, Angela Smith, Tom Cherrett; writing—review and editing, Morgan Campbell, Angela Smith, Tom Cherrett.; funding acquisition, Tom Cherett. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation.

Funding

This research was funded by Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, grant number EP/V002619/1 and Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/X007952/1. The APC was waived by the journal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of Leeds (AREA FREC 2022-0205-151)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data and analysis files for this study will be made available in the White Rose Research repository (currently securing an open access URL).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the other members of the E-Drone and Future Flight research team who have tested preliminary Q-Sorts or discussed our findings as they emerge as well as our study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency 2023. European Plan for Aviation Safety (EPAS) 2023-2025 European Union Aviation Safety Agency VOLUME I Strategic priorities. Available at https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/general-publications/european-plan-aviation-safety-epas-2026 [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- Civil Aviation Authority 2024. Airspace Modernisation Strategy 2023–2040 Part 1: Strategic objectives and enablers CAP 1711. Available at https://www.caa.co.uk/publication/download/17167 [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- Manna 2025. https://www.manna.aero/explore [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- NHS Ayrshire and Arran 2024. NHS laboratory specimens delivered over Firth of Clyde by drone for first time by Project CAELUS. Available at https://www.nhsaaa.net/nhs-laboratory-specimens-delivered-over-firth-of-clyde-by-drone-for-first-time-by-project-caelus/ [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- Zenz, A.; Powles, J. Resisting technological inevitability: Google Wing’s delivery drones and the fight for our skies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2024, 382, (2285). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RTE 2025. Locals oppose Manna Drone delivery hub for Dublin 15. Available at: https://www.rte.ie/news/business/2025/1119/1544743-locals-oppose-manna-drone-delivery-hub-for-dublin-15/ [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- Dickinson, J., Smith, A., Drummond, J., Nadeem,T., Cherrett ,T. , Permana, R. ,Waterson, B., Oakey, A. What do people think about logistics drones? Exploring a possible transport future using virtual reality. 2024. Manuscript submitted for publication. Bournemouth University Business School. Bournemouth University; Available at: https://generic.wordpress.soton.ac.uk/edrone/wp-content/uploads/sites/516/2024/10/VR-paper-submission.pdf.

- Mendoza, M.; Alfonso, M.; Lhuillery, S. A battle of drones: Utilizing legitimacy strategies for the transfer and diffusion of dual-use technologies. Technol. Forecast. and Soc. Change 2021, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, M.; Oakey, A.; Pilko, A.; Krol, J.; Blakesley, A.; Cherrett, T.; Scanlan, J.; Anvari, B.; Martinez-Sykora, A. Investigating the emissions effect of integrating drones into mixed-mode logistics – A case study of a healthcare setting. Int. J. Sust. Transp. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., Dickinson, J., Oakey, A., Grote, M. and Cherrett, T. Drone deliveries and the medical use case – Research Summary May, 2023; Available at: https://generic.wordpress.soton.ac.uk/edrone/wp-content/uploads/sites/516/2024/05/Drone-Medical-Use-Case-v2.pdf [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- Mason-Wilke, W.; Elsdon-Baker, F. Re-Imagining Future Flight in the UK. Public Responses to Future Flight Media Imagery and Their Implications. In Future Flight Governance; Amstalden, M., Packer, A. M., Lewis, M., Eds.; Routledge, UK, 2025; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sabino, H.; Almeida, R.; Baptista de Moraes, L.; Paschoal da Silva, W.; Guerra, R.; Malcher, C.; Passos, D.; Passos, F. A systematic literature review on the main factors for public acceptance of drones. Tech. Soc. 2022, 71, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Dickinson, J.; Marsden, G. Public acceptance of the use of drones for logistics: The state of play and moving towards more informed debate. Tech. Soc. 2022, 68, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Dickinson, J.; Nadeem, T.; Snow, B.; Grote, M.; Cherrett, T. Trials, Representations, and Uncertainties. Involving People with Advanced Air Mobilities. In Future Flight Governance; Amstalden, M., Packer, A. M., Lewis, M., Eds.; Routledge, UK, 2025; Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.; Mladenović, M. The politics of autonomous vehicles. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2022, 9, 433, s41599-022-01463-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouffe, C. On the political; Routledge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Deliberative Policy Analysis as Practical reason: Integrating Empirical and Normative Arguments. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory Politics and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G.J., Sidney, M.S., Eds.; Routledge: USA, 2007; Chapter 16. [Google Scholar]

- González-González, E.; Cordera, R.; Stead, D.; Nogués, S. Envisioning the driverless city using backcasting and Q-methodology. Cities 2023, 133, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigdinos, S.; Tzouras, P.G.; Bakogiannis, E.; Kepaptsoglou, K.; Nikitas, A. The future urban road: A systematic literature review-enhanced Q-method study with experts. Transp. Res. D: Transp. Env. 2022, 102, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudau, M.; Celio, E.; Grêt-Regamey, A. Application of Q-methodology for identifying factors of acceptance of spatial planning instruments. J. Env. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66(9), 1890–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemmings, D. Quantifying qualitative data: an illustrative example of the use of Q methodology in psychosocial research. Qual. Res. Psych. 2005, 3(2), 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analysis Protocol, Qmethods software, 2025. https://app.qmethodsoftware.com/docs/articles/study-analysis/analysis.html [Accessed 19 December 2025].

- Vigar, G. The four knowledges of transport planning: Enacting a more communicative, trans-disciplinary policy and decisions-making. Transp. Pol. 2017, 58, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K-A.; Moon, J. Exploring the existence of moderated mediation of attitudes between privacy and risk in the intention to use drone deliver services. Sustainability 2025, 17(6), 2585. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.; Cohen, T. Rejecting acceptance: learning from public dialogue on self-driving vehicles. Sci. Pub. Pol. 2021, 48, 849–859. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, K. Sustainability and New Technologies: Last-Mile Delivery in the Context of Smart Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16(8), 8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).