1. Introduction

Forensic ethanol standards play an important role in the legislation concerning the driving under the influence of alcohol. In many countries, the base document for the metrological requirements for evidential breath analysis is OIML-R126 [

1]. Gaseous certified reference materials (CRMs) are required to calibrate equipment that is being used for surveillance. These CRMs are generally certified for the amount fraction ethanol in nitrogen or air. VSL, the national metrology institute of The Netherlands maintains primary measurement standards, primary standard gas mixtures (PSMs) in the range 50 μmol mol

−1 to 1000 μmol mol

−1. The preparation of such mixtures is usually done in accordance with ISO 6142 [

2,

3]. The previous edition of this standard (ISO 6142:2001) [

4] was amended to include the use of syringes or other transfer vessels to prepare mixtures involving liquids [

5].

Currently, ISO 6142-1 [

6] is widely used for preparing PSMs and primary reference materials (PRMs) for forensic ethanol gas standards. The calculation of the amount fraction ethanol in the calibration gas mixture rests on the assumption that the composition of the constituents entered into the cylinder is identical with the composition of the (homogenised) gas mixture when sampling from the cylinder. For ethanol, this assumption is not entirely valid, as this component shows adsorption on the cylinder wall. As a result, the amount fraction ethanol in the gas withdrawn from the cylinder is lower than the amount fraction ethanol computed from the preparation data. As all gas molecules show some degree of adsorption on solid surfaces, this assumption is more appropriate for some types of calibration gas mixtures than for others. Ethanol, just as other polar molecules (e.g., water, ammonia) shows substantial adsorption on the cylinder wall. Whether such adsorption is problematic with respect to assigning a value and uncertainty to the amount fraction of the component of interest depends on the user requirements. For forensic ethanol standards, the adsorption is large enough to be taken into consideration given the typical uncertainty.

The PSMs of National Metrology Institutes (NMIs) are compared in key comparisons to assess their equivalence in key comparisons [

7,

8]. In the key comparison CCQM-K4 [

2], the values and uncertainties assigned to the amount fraction ethanol were just those obtained from the prepatation process of ISO 6142 [

4,

5]. In the key comparison CCQM-K93 however, some NMIs applied an adsorption correction, whereas others did not. VSL was among the latter. The nominal value of the amount fraction ethanol in this key comparison was 120 μmol mol

−1. The travelling standards submitted were used as calibration standard and the result of the amount fraction of a working standard was recorded [

3]. A consensus value was used to evaluate the results of the key comparison. Considering this design of CCQM-K93, a positive difference in the degree of equivalence flags that the amount fraction ethanol in the travelling standard was assigned too high. That is consistent with an unaccounted loss of ethanol due to cylinder wall adsorption.

The aim of this work is to develop a method for measuring the adsorption loss when preparing a calibration gas mixture in a cylinder with a given type of passivation. Passivation of the interior of gas cylinder serves the purpose of reducing the reactivity and adsorption at the cylinder wall. It should be born in mind that the effects are usually reduced, rather than completely eliminated. Generally, it is believed that the adsorption of a component at a surface is a function of the temperature, pressure and composition of the gas mixture. It is not considered a function of the preparation process, or the order in which the materials are transferred into the cylinder. Depending on this order, it may take shorter or longer to equilibrate and homogenise the calibration gas mixture after preparation. This equilibration also involves the equilibrium between adsorbed molecules and molecules of the same entity in the gas or vapour phase.

The experimental details of the work are described in

Section 2. The modelling of the adsorption loss is described in

Section 3 and the data reduction in

Section 4. The results are summarised in

Section 5. Form these, an interpolation formula was developed, as described in

Section 6.

2. Experimental

The method used decanting of a gravimetrically prepared ethanol standard into a nominally identical, evacuated gas cylinder [

9,

10,

11]. As the two cylinders are having the same passivation, valve, etc., it is assumed that the loss that occurs during the gravimetric gas mixture preparation also occurs during decanting. The decanting was performed in a controlled way to reduce temperature changes during the process. The tubing used was heated to 40 °C to reduce losses due to the transfer of the gas from the parent mixture (the mixture being decanted).

The parent gas mixtures were prepared in accordance with ISO 6142-1 [

6] using the syringe method. This process was described previously elsewhere [

12]. For the weighing of the cylinder and the syringe, the substitution method was used [

13]. The children were prepared using the same process as used for preparing calibration gas mixtures with adsorbing or reactive components. Features of this method are the use of a heated (70 °C), short transfer line and using a low flow rate of the gas transferred from the parent gas cylinder. This process mitigates losses during the transfer of the parent gas mixture to the cylinder for the child mixture.

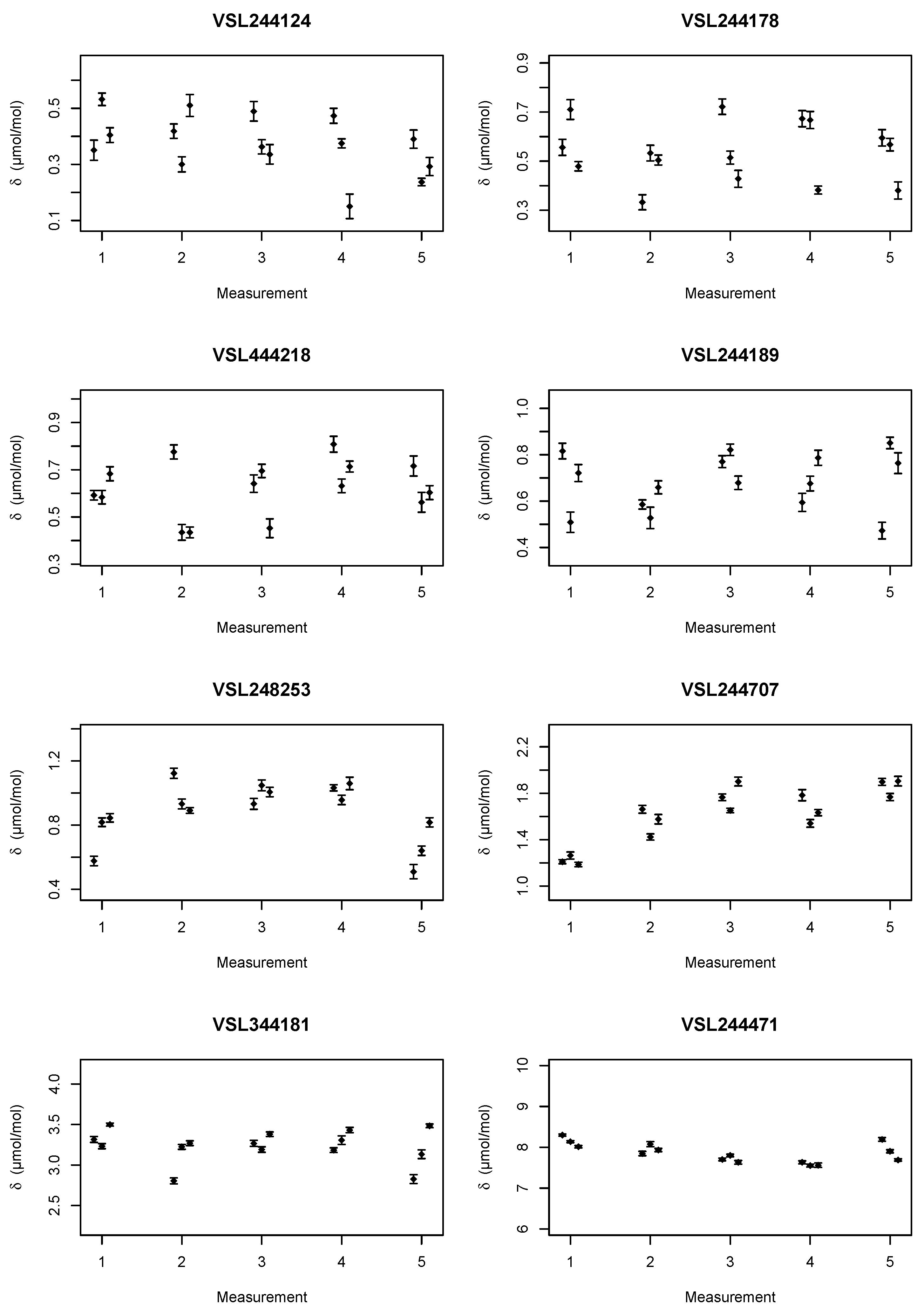

Two sets of mixtures were prepared, see

Table 1 and

Table 2. The stated uncertainties are those from gravimetric preparation only, and do not account for, e.g., adsorption losses and the verification of the mixtures. The amount fractions for the second set were chosen to be slightly different, so that when the two data sets were combined in the regression, the relationship between the adsorption loss (

) and the amount fraction (

x) could be better established. It had been anticipated that between-cylinder effects would play a more important role at low amount fractions and the behaviour of the passivation would be more regular for amount fraction above 100 μmol mol

−1.

The pairs of the parent and child mixtures were then analysed. For this purpose, an Xendos 2500 non-dispersive infrared spectroscopy (NDIR) analyser from Servomex was used that is normally used for verification measurements as described in ISO 6142-1 [

6] and is used for calibrating gas mixtures using ISO 6143 [

14]. The cylinders were connected using dedicated stainless steel regulators. The measurements were performed by connecting the suite of 16 gas mixtures to a 16-way multi-position valve which in turn was connected to the NDIR monitor. The mixtures were analysed from low to high amount fraction, and the child before the parent in the sequence. The flushing of the regulators and sampling lines was done as usual.

The NDIR analyser was operated in the same way as during such verification measurements and calibrations. For each mixture, a response was obtained by sampling the signal for 90

, providing 90 indications. From these indications, a mean and standard deviation were computed which are used as the response and standard uncertainty of the response, respectively. The characterisation of this kind of analysers has revealed that the noise of the signal is not white noise, so the assumption that the 90 indications are independent and identically distributed (IID) and Gaussian is not appropriate here. The chosen approach provides a cautious value for the standard uncertainty, assuming a high degree of (auto)correlation [

15] between the 90 indications.

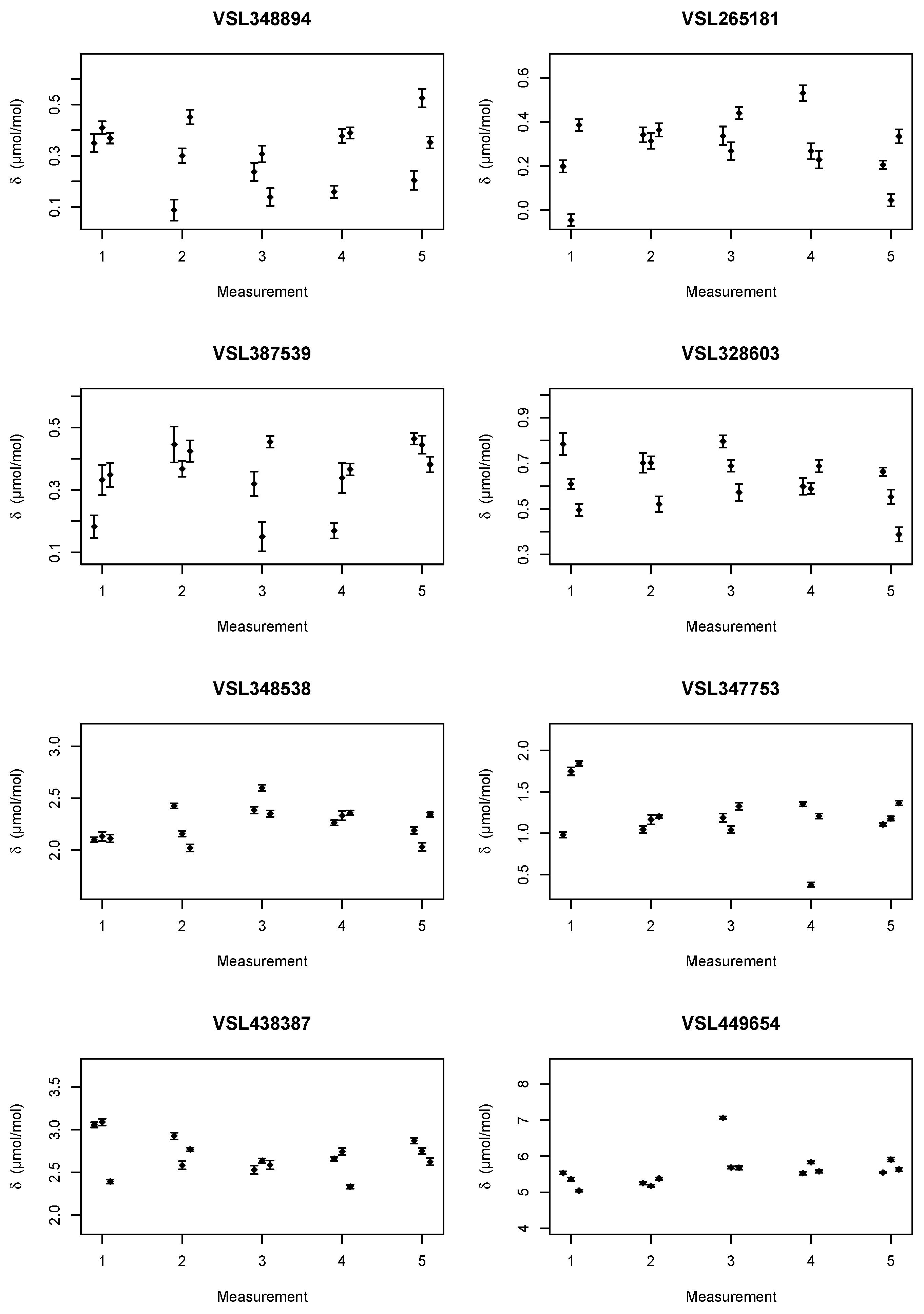

During the analysis of the set of mixtures in

Table 1, it was noted that the amount fraction assigned based on the gravimetric gas mixture preparation was off for the nominally 700 μmol mol

−1 mixture. The same effect was visible in the data for the child. It was decided that instead of discarding the data to re-assign the amount fraction ethanol based on the first analysis. A straight line was used as calibration function and the data from the parent mixtures were processed in accordance with ISO 6143 [

14]. The amount fraction used for VSL348894 was, based on the analysis, adjusted to 678.63 μmol mol

−1 with a standard uncertainty of 0.03 μmol mol

−1. The latter standard uncertainty does not include any adsorption aspects.

3. Adsorption Correction

The relationship between adsorption loss, amount fraction ethanol and the responses was developed using the model for a single point calibration [

16,

17]. In usual calibrations, a straight line is used as calibration function and as the instrument response is corrected for a zero offset, the straight line passes in good approximation through the origin, no non-linearity effect of the analyser had to be taken into account. Considering that the anticipated losses are in the order of 0.210 μmol mol

−1, the departure from a straight line through the origin between parent and child is expected to be negligible in relation to other uncertainty components.

An important assumption underlying the modelling is that the adsorption of ethanol in two nominally identical cylinders with the same passivation and valves is the same. So, it is expected that the parent calibration gas mixtures are prone to a single adsorption loss, whereas the children are expected to have a double adsorption loss. The adsorption loss is modelled to the observed responses as follows. Let the response factor be defined as

where

denotes the instrument response and

the amount fraction ethanol. If there is adsorption from ethanol to the wall, then the corrected amount fraction

will be smaller than

by a difference

. When decanting the mixture into an evacuated cylinder, the amount fraction

will be smaller than

by

[

18]. If

remains constant, then

where the corresponding responses

and

are observable. We now have a system of two equations with unknowns

and

.

is known from gravimetric gas mixture preparation. Considering that

and

, the responses can be expressed as

Subtracting equation (

3) from equation (

2) yields

and the response factor

can be computed from

using equations (

2) and (

4). Finally,

can now be computed as (see also equation (

4))

This correction can be related to the mass ethanol transferred into the cylinder by using the formulæ of ISO 6142-1 [

6,

19], but can also applied directly to the amount fraction computed from gravimetric gas mixture preparation. It is worth noting that equation (

6) expresses the drop in the amount fraction ethanol solely in the observable responses of the parent and child calibration gas mixtures and the amount fraction assigned on the basis of the gravimetric preparation.

For physical reasons, values for can be restricted to be non-negative and not exceed . If all molecules would be adsorbed onto the surface, it is expected that the amount fraction in the gas phase is zero, so the adsorption loss equals the amount fraction as calculated from preparation. For ethanol, the constraint that values for may not have too much influence, as for this molecule there is appreciable adsorption. For molecules with weaker interactions, such as carbon dioxide or methane, including this constraint in data models can be appropriate. For this study, the comnstraint that is non-negative did not need to be enforced. The measured values and uncertainties were such that these results were all significantly greater than zero.

One of the traits of this method is that it is straightforward to combine results from different experiments. It is assumed that pairs of mixtures (parent/child) are always analysed under repeatability conditions. Working under repeatability conditions provides the smallest uncertainties for the adsorption losses . Combining the results from different pairs does not rest on working under repeatability conditions though. So, it is straightforward to combine the results from different series of experiments.

4. Data Reduction

The data reduction was performed into two steps. In each of them a Bayesian hierarchical model was used. The hierarchical model was used to (1) obtain a mean adsorption loss for each of the measurements and (2) obtain a mean adsorption loss for each pair of gas mixtures. The amount fractions and adsorption losses

for the pairs of gas mixtures

i were then used to obtain an interpolation function (see

Section 6).

The Bayesian hierarchical models for combining the three runs in a measurement and the five measurements into one set of results for

contained one level. The likelihood of reads as [

20]

where

i denotes the index of the pair of gas mixtures,

j the index of the run (

) or measurement (

),

the calculated value for the adsorption loss

and

the associated standard uncertainty.

denotes the fitted value for

and

the pooled standard deviation.

denotes the normal distribution.

The

are assumed to be drawn from a normal distribution with mean

and standard deviation

, where

denotes the mean from the runs and

the standard deviation of the between-run effects. Conditional on these parameters, the

are normally distributed [

20]

with mean

and variance

, where

For the data reduction, the interest is in the estimates of

. The

are of interest as they provide information about the between-run variability, which can be used to benchmark the observed responses during regular calibration. The formula for computing

takes the form

and its associated standard uncertainty can be obtained from

For the computation of

, there is no simple formula. Its estimate can be obtained from the posterior probability distribution, which is obtained by fitting the Bayesian model [

20].

The hierarchical model has three parameters (

,

and

). The priors for these parameters are as follows [

21]

where

denotes the Cauchy distribution [

20,

21,

22]. None of these priors contains much information. They were chosen so that the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method (MCMC) samples from the regions with likely values for

,

and

[

20,

23]. The model was fitted using MCMC as implemented in

R [

24] using the

RStan package [

25]. Four (4) chains were used, the number of iterations 300000 of which 50000 were used as ’burn-in’. The data were thinned 1:5.

The parameters for the prior probability distribution functions for fitting the data from the runs for the first set of mixtures are shown in

Table 3. The normal prior for the adsorption correction has been chosen with a mean to be close to the anticipated adsorption losses and a standard deviation that equals the mean, thereby obtaining a weakly informative prior. The purpose of the latter prior is to improve the performance of the MCMC.

The parameters for the prior probability distribution functions for the parameters in the hierarchical Bayesian model for fitting the data from second set of mixtures are shown in

Table 4. The deliberations for the choice of these values were the same as for the first set of mixtures.

To obtain the estimate for the adsorption loss

from the five measurements, the same Bayesian hierarchical model was used. The parameters of the priors were elicited based on results from the maintenance work on the national PSMs which involves the same preparation and verification procedures [

26]. The same probability density functions were used as priors, but now with parameters

μmol mol

−1,

μmol mol

−1 and

μmol mol

−1.

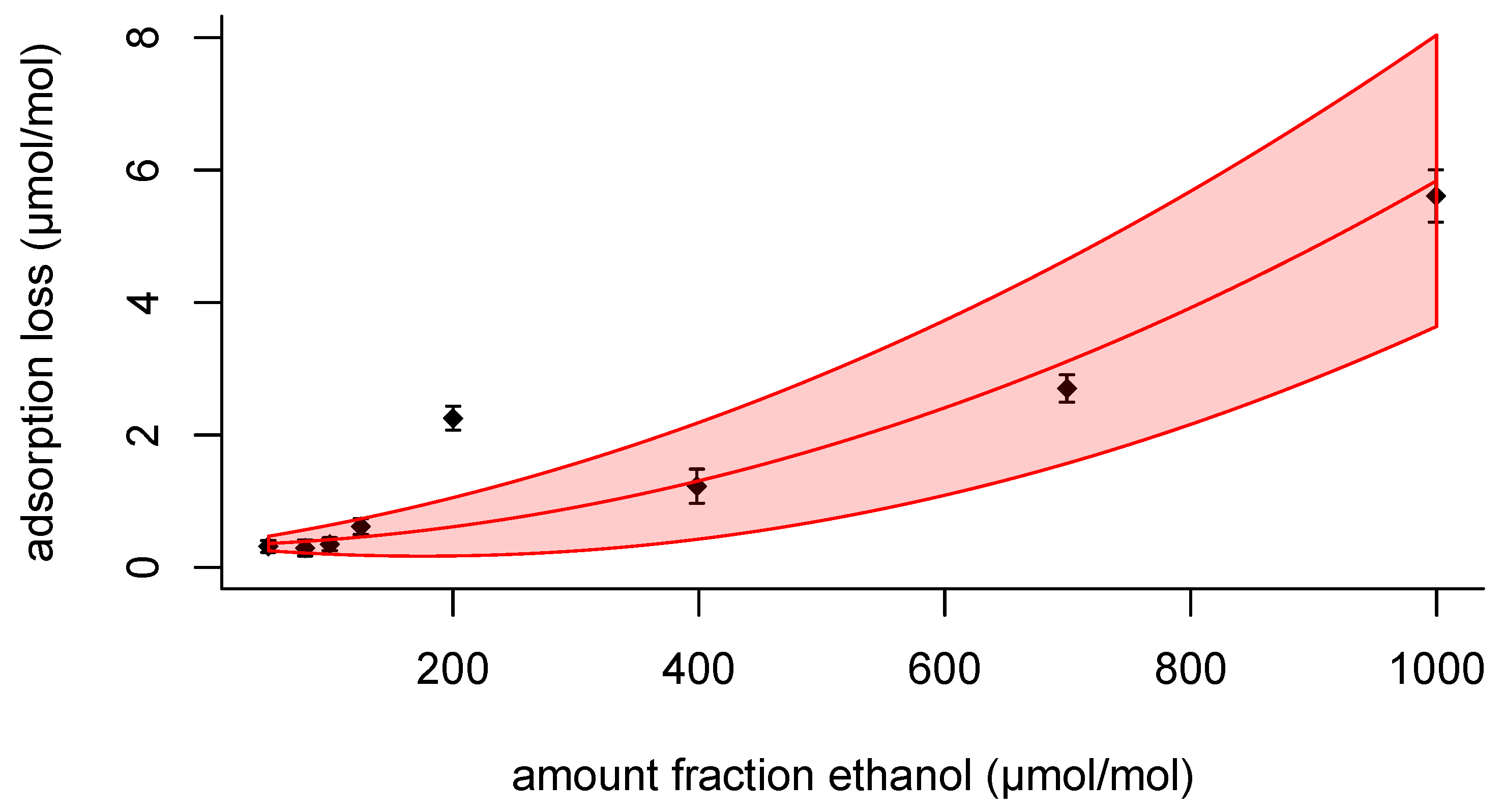

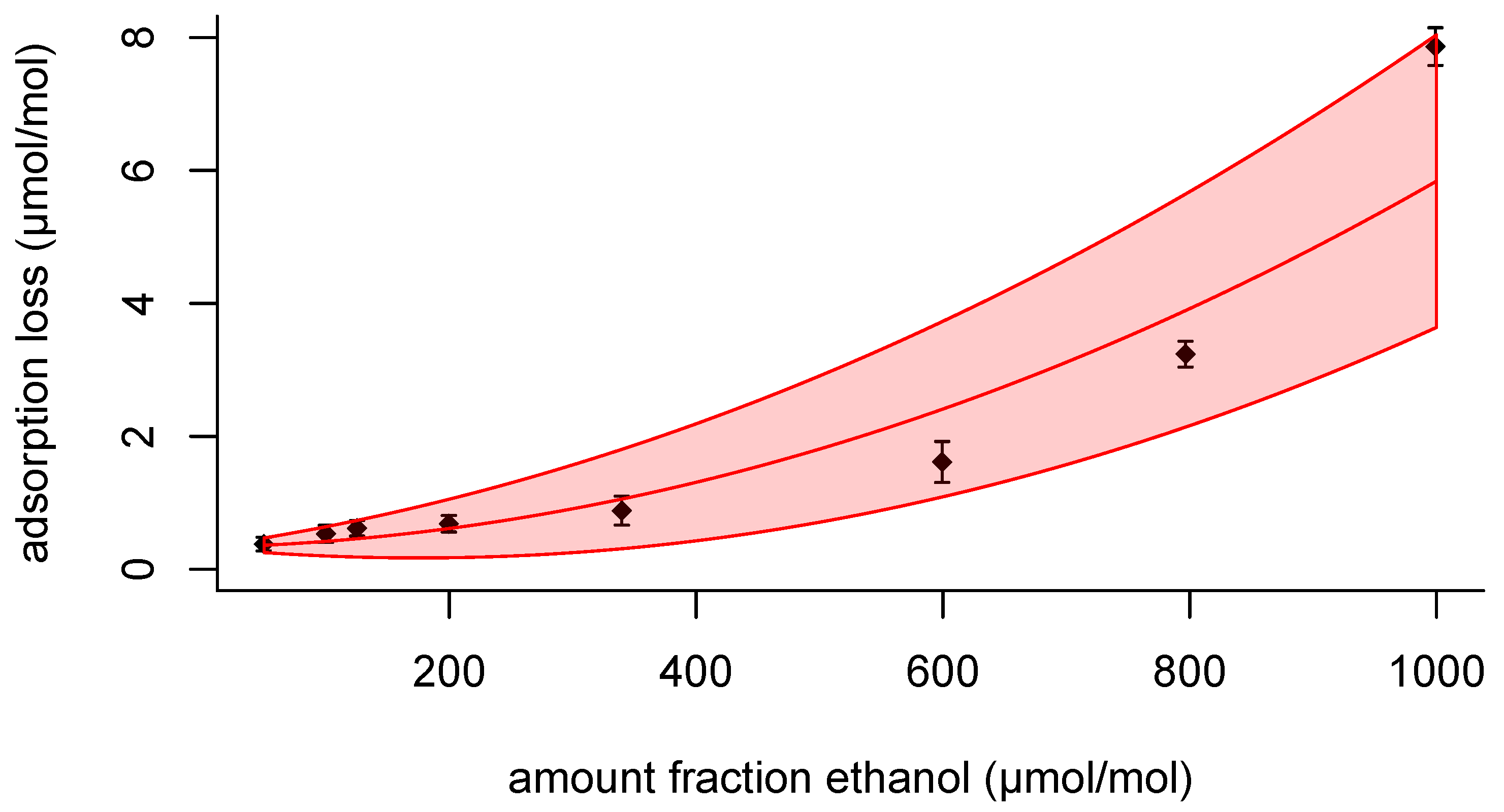

6. Interpolation Formula

Rather than working with the measured adsorption losses themselves, for daily use it would be convenient having an interpolation formula that predicts the adsorption loss

for given amount fraction ethanol. Looking at the adsorption loss data in

Figure 2 and

Figure 4, it is evident that a straight line will not do to describe the data. The shape of the relationship looks more like an exponential or a quadratic function. Considering that the departure from a straight-line relationship is not too large, a quadratic function can be probed, which is mathematically easier to handle in regression than an exponential function. Furthermore, when writing the exponential function as a Taylor series, it is a polynomial [

27] and it can be shown for the adsorption loss data that the terms after the quadratic term are irrelevant to describe the data. So, the relationship between

and

x can be written as

Fitting the data from set 1 using ordinary least-squares method (OLS) provided

,

and

, where both

and

are in μmol mol

−1. Setting a tolerance interval of

of the amount fraction ethanol, the relative differences using the coefficients from set 1 are as follows (

Table 7). The relative difference, calculated as

takes values

for all predicted adsorption losses within the tolerance interval. For the second set, the parameter values from fitting the data of the first set make predictions within the same tolerance interval (see

Table 7). The poor prediction of the 200 μmol mol

−1 pair from the first set (top half of

Table 7) is due to the anomalous behaviour of this pair of mixtures; the prediction for the 200 μmol mol

−1 pair from the second set is good.

For practical purposes, the uncertainty associated with the

from gravimetry can be neglected; it is much smaller than the uncertainty associated with the

, so for fitting the data, the choice is between OLS or weighted least-squares method (WLS). With OLS, all data points get the same weight which presumes that the regression data are homoscedastic (i.e., have a constant variance). Looking at the data in

Figure 2 and

Figure 4 shows that the standard uncertainty associated with

increases with increasing

, which makes WLS the preferred choice, as it weighs the residuals according to the standard uncertainty associated with the dependent variable (here

). Apart from the heteroscedasticity in the adsorption loss data, there is also an overdispersion in the data, i.e., there is more dispersion in the data than accounted for by evaluating the standard uncertainty associated with the adsorption loss. Looking at the pair at 200 μmol mol

−1 and 1000 μmol mol

−1, this overdispersion is likely to be due to the fact that the adsorption loss is not identical for each cylinder. This is a form of between-bottle homogeneity [

28,

29] and a relevant component in the evaluation of the uncertainty. The regression method of choice should not only provide the values for the coefficients, but also a value for the standard deviation for overdispersion. Mixed-effects models as known from meta analysis [

30] are capable of doing so. If it is assumed that the excess standard deviation is proportional to the amount fraction ethanol, the regression can be performed by fitting

as a function of

. The equation then becomes

This model can be fitted in

R [

24] using function

rma from the

metafor package [

31]. The weights assigned are the inverses of the squared standard uncertainties associated with the measured adsorption losses. The coefficients of the model are given in

Table 8. Considering the standard uncertainties, the coefficients

(the linear term) and

are insignificant. It would be tempting to describe the model with only the constant term (

), but that would clearly contradict the results shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 4. Hence, it is preferred for the interpolation to use The value of

, the excess standard deviation is 0.105.

The performance of the interpolation function (

8) is shown in

Table 9.

denotes the predicted adsorption loss,

the between-bottle effect,

the combination of the standard uncertainty associated with

and the excess standard deviation

. The ultimate column in

Table 9, labelled

, shows the standard uncertainty

relative to the amount fraction ethanol,

x. The relative standard uncertainty associated with the correction is 0.11 for amount fractions in the range 100 μmol mol

−1 to 1000 μmol mol

−1 and increases to 0.15 for amount fractions down to 50 μmol mol

−1 (

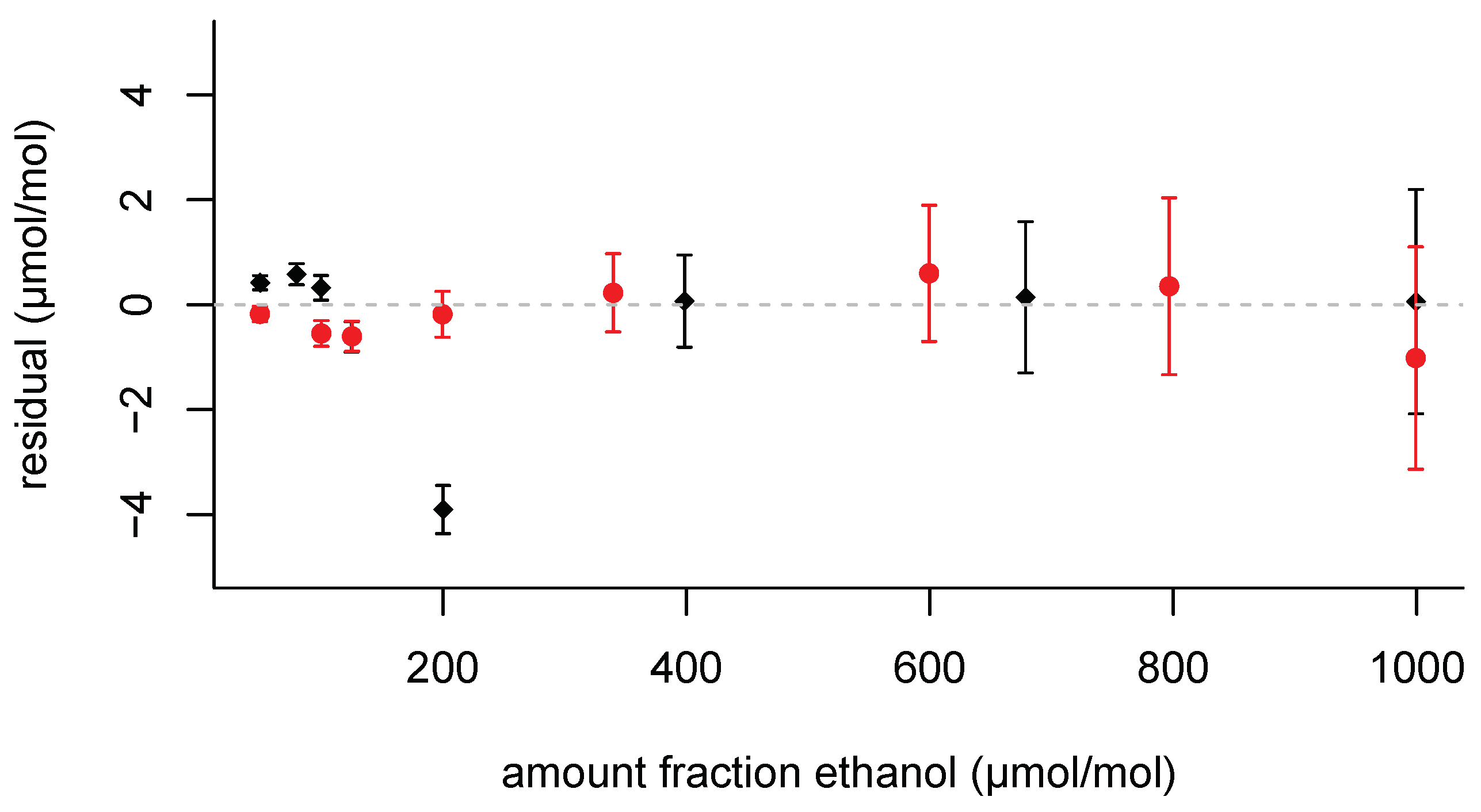

Table 9). The residuals are shown in

Figure 5. Most of these residuals are within

. The 200 μmol mol

−1 pair of mixtures from the first set is a notable exception. The two 1000 μmol mol

−1 pairs of mixtures agree reasonably well with each other. The proposed standard uncertainty associated with the adsorption correction is given in the final column. This standard uncertainty is slightly larger than the value of

, for it includes the measurement uncertainty from the measured adsorption loss.

The residuals in

Figure 5 show largely opposite signs across the range of amount fractions. For instance, for the data in the range from 50 μmol mol

−1 to 125 μmol mol

−1, the relative differences are positive in the first data set and negative in the second; also the relative differences at 1000 μmol mol

−1 carry opposite signs. These patterns flag that the interpolation formula does not induce a particular bias in a specific part of the amount fraction range from 50 μmol mol

−1 to 1000μmol mol

−1 and represents the empirical data well.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The method used for measuring adsorption losses enables determining these losses under repeatability conditions. The link with the amount fraction ethanol is established using the amount fraction computed from the static gravimetric preparation according to ISO 6142-1. In this case, no further calibration of the analyser was deemed necessary as the performance characteristics of the analyser were known. From the calibration function established for the first suite of gas mixtures prepared for this study, it was inferred that the amount fraction of the 700 μmol mol

−1 mixture was off, which propagated to the amount fraction ethanol in the decanted (child) mixture. Parent and child were assigned a new amount fraction based on analysis using the multipoint calibration method of ISO 6143 [

14]. In all other cases, the analyser was effectively calibrated using a single point approach according to ISO 12963 [

16,

17]. The method for determining the adsorption losses uses three observable quantities, i.e., the amount fraction ethanol as computed from ISO 6142-1 [

6,

19], the response of the parent mixture and the response of the chlid mixture, to compute the adsorption loss. From the input quantities, further desired output quantities can be computed such as the amount fractions ethanol in the parent and child mixtures adjusted for the adsorption loss. The adsorption losses are a function of the amount fraction ethanol. From the results, a quadratic interpolation function was established. A mixed-effects model with excess variance was needed to account for the between-bottle homogeneity effects. These effects are due to the apparent differences in adsorption between gas cylinders with nominally identical passivation and cylinder values. Including the between-bottle homogeneity effect, the interpolation formula predicts adsorption losses for the amount fraction ethanol from 50 μmol mol

−1 to 1000 μmol mol

−1 with a relative standard uncertainty from 0.150.11. Cylinders that show anomalous adsoprtion behaviour will be found during the verification of gravimetrically prepared ethanol standards by result that does not agree with the result obtained from preparation, including an adjustment for the ethanol adsorption. The work underlines that between-bottle effects in reference material production can be relevant even in cases when reference materials (RMs) are characterised and provided one at a time. This is a notion that is missed in ISO 10734 [

32] and ISO 33405 [

33]. For most RMs, interactions between the material and the inner surface of the packaging material (e.g., sample container) are minimal, but in gas analysis this is for high-end applications not necessarily the case. The phenomenon is for instance also relevant for RMs for nitrogen dioxide analysis and other reactive components. When extreme precision between RMs is required, as with RMs for monitoring greenhouse gases, between-bottle effects are also relevant to consider in the uncertainty budget(s) of the property value(s).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AvdV and GN; methodology, AvdV, MN; software, AvdV; validation, GN, NM and JL.; formal analysis, AvdV; resources, GN; data curation, AvdV; writing—original draft preparation, AvdV; writing—review and editing, AvdV, NM, GN and JL; visualization, AvdV; funding acquisition, GN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..