Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Standard N2O Gas Concentration for Calibration

2.2. Experiment 1: Residual Gas Effect on N2O Gas Concentration for Different Evacuation Methods

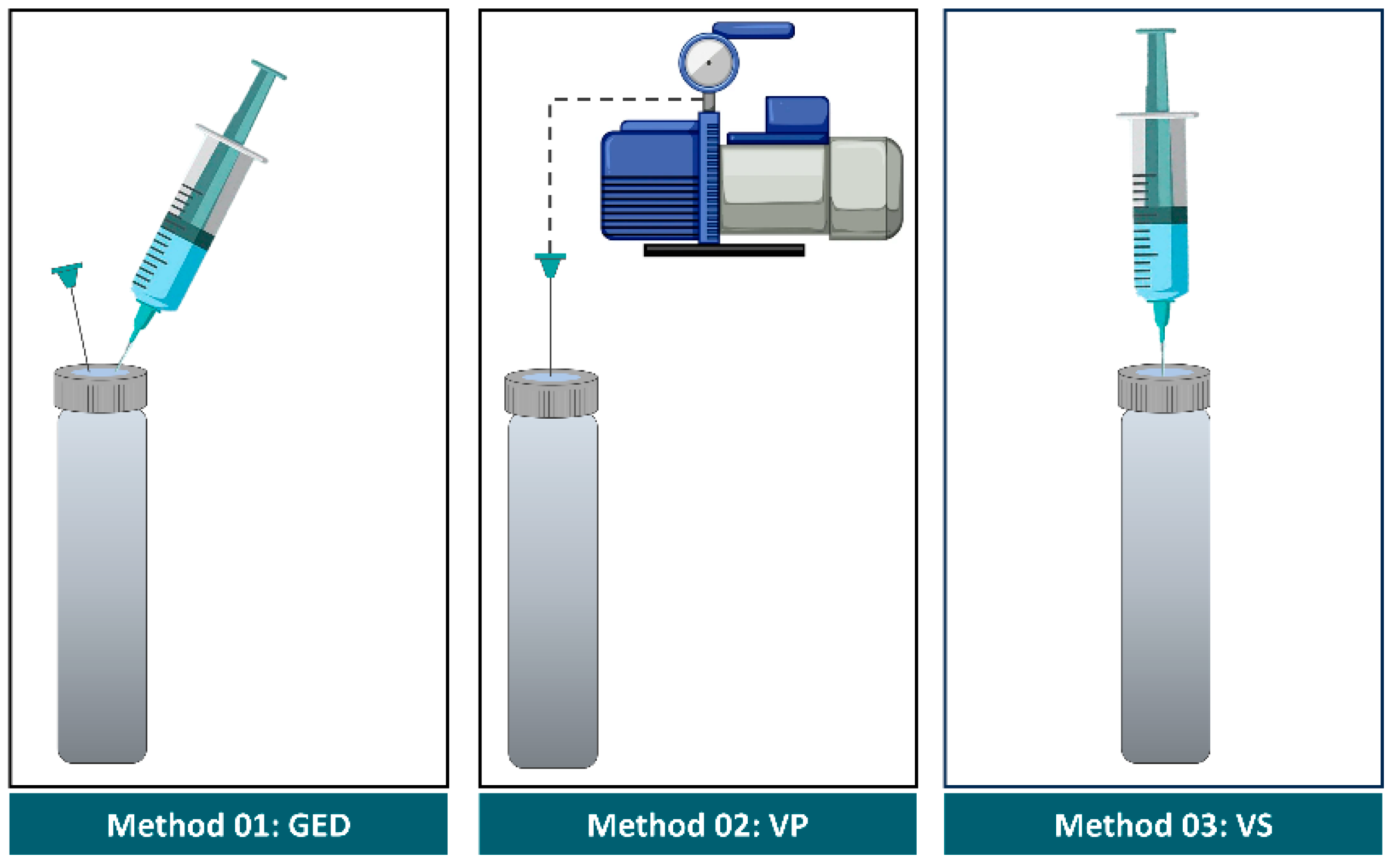

2.2.1. Gas Exchange by Displacement (GED) Method

2.2.2. Evacuation with Vacuum Pump (VP)

2.2.3. Evacuation with a Syringe (VS)

2.2.4. Pre-Evacuated Exetainer (PEE)

2.3. Measure the Vacuum Level of the Exetainer

2.4. Experiment 2: Impact of Standard N2O Gas Storage Method

2.4.1. Standard N2O Gas in a Syringe (SM)

2.4.2. Standard N2O Gas in Exetainer Vials (EVM)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Residual Air Pressure of the Exetainer Vials Prepared with Different Methods

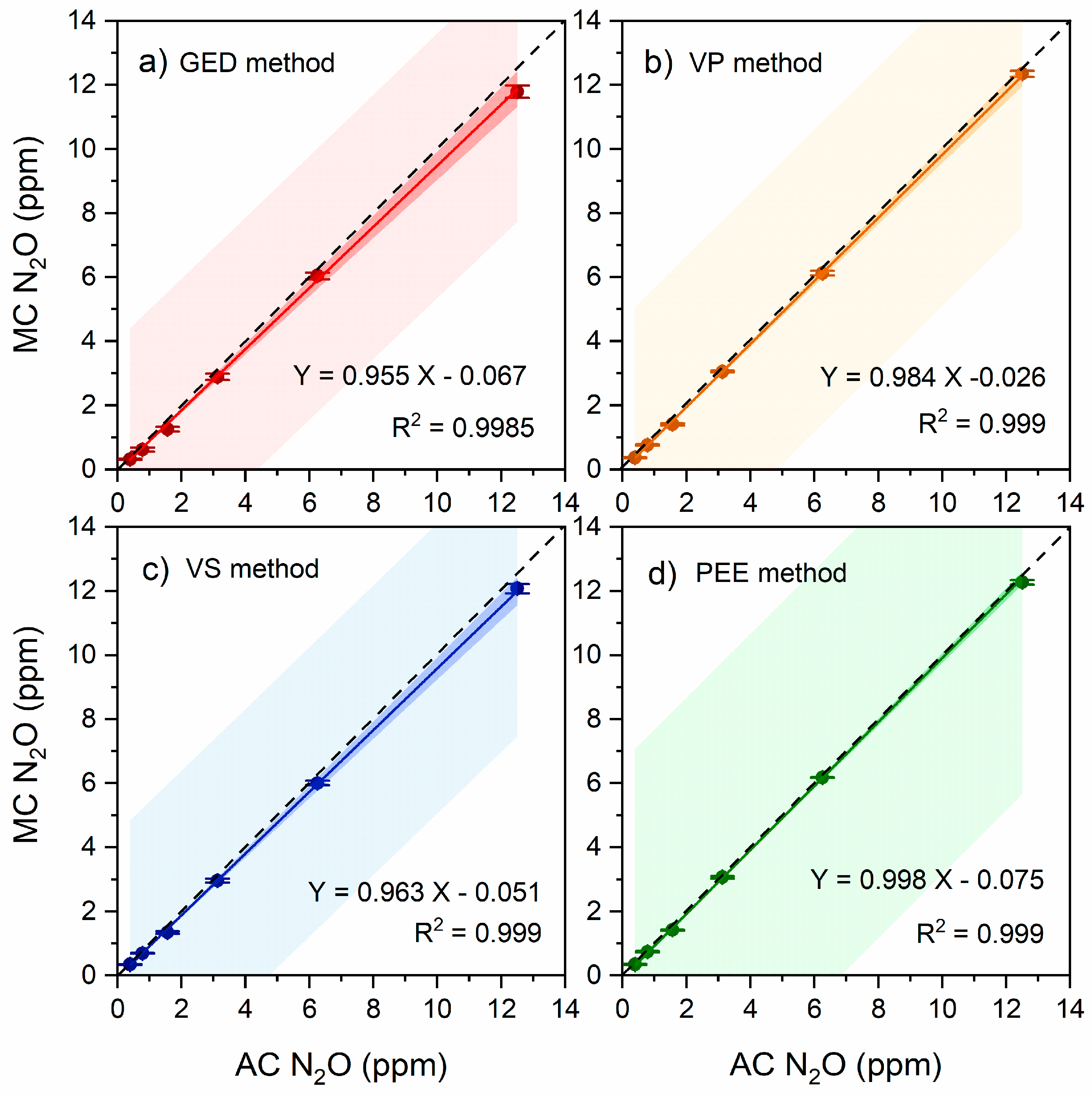

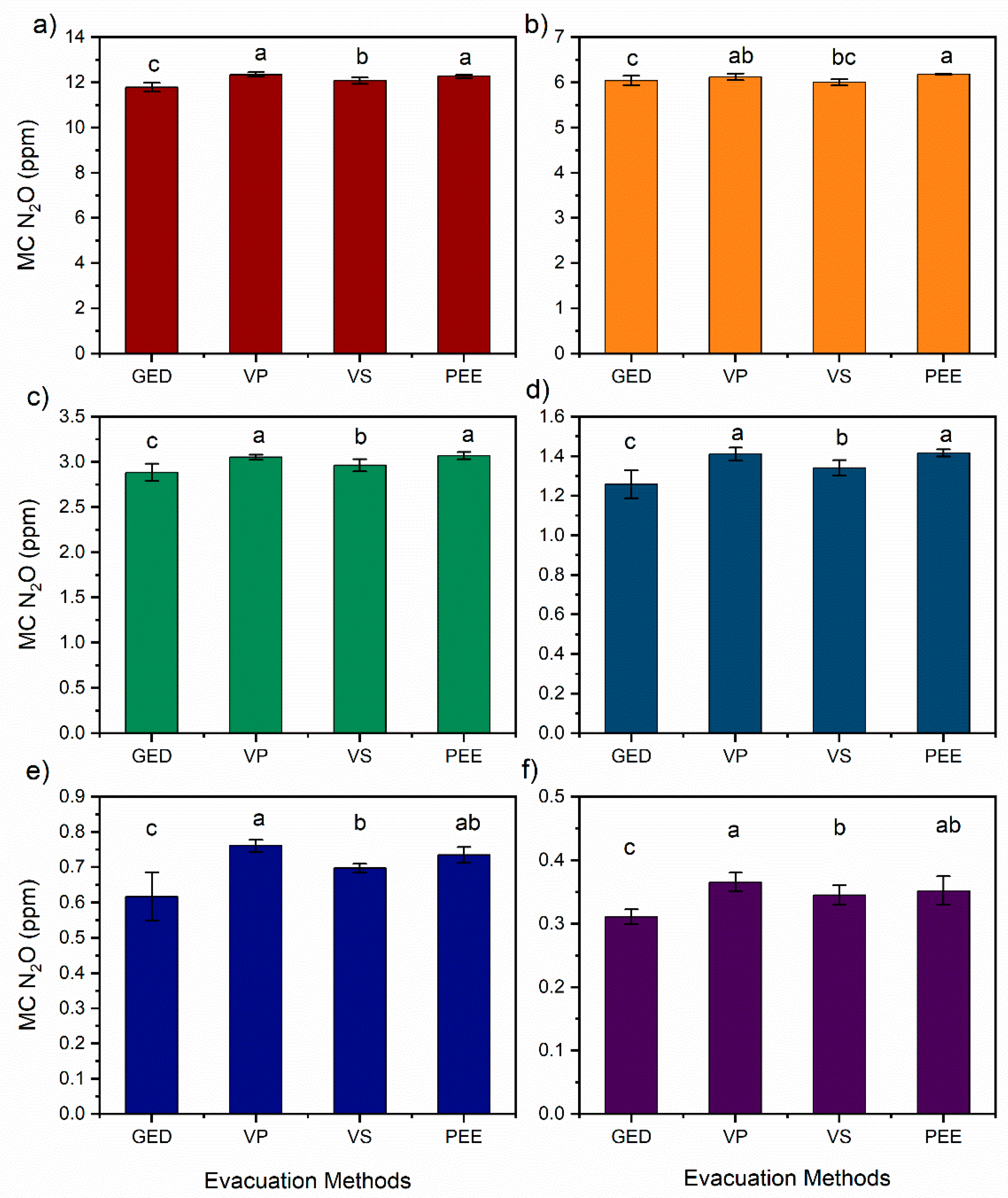

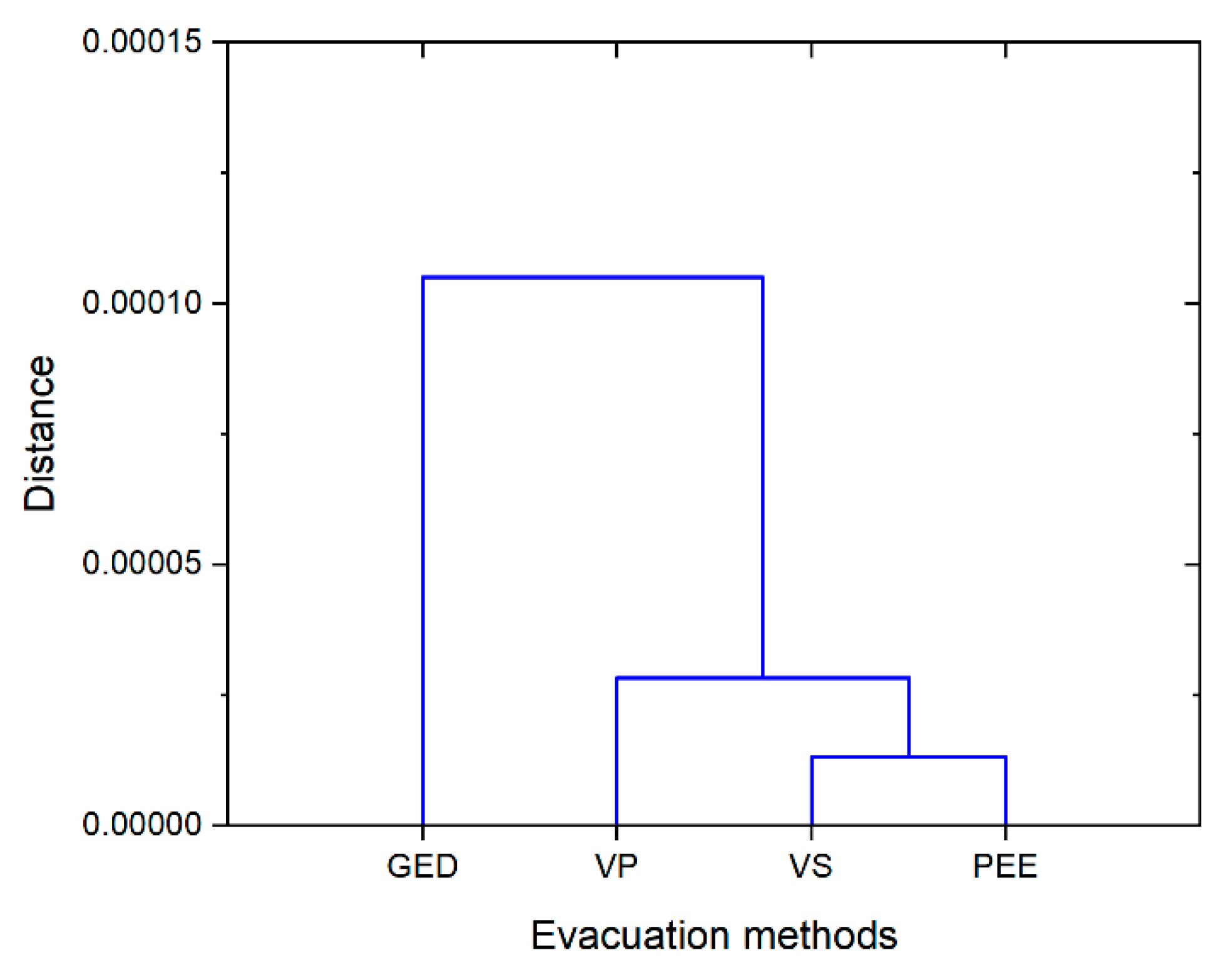

3.2. Residual Gas Effect on the N2O Gas Concentration for Different Excavation Methods

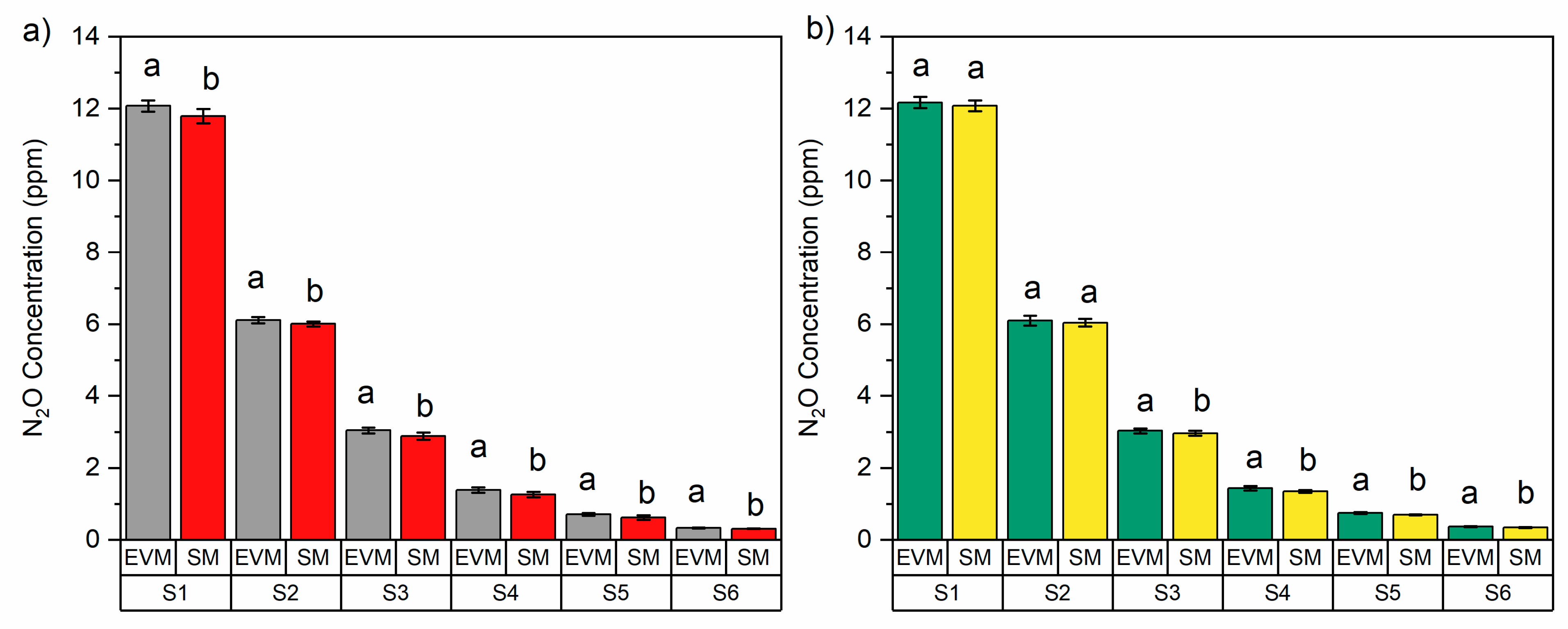

3.3. Impact of Standard N2O Gas Storage Method on N2O Concentration

4. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, M.W.; Peters, G.P.; Gasser, T.; Andrew, R.M.; Schwingshackl, C.; Gütschow, J.; Houghton, R.A.; Friedlingstein, P.; Pongratz, J.; Le Quéré, C. National contributions to climate change due to historical emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide since 1850. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 155. [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Grafton, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bishop, P.; Davies, C.E.; McCurdy, M. The nitrogen dynamics of newly developed lignite-based controlled-release fertilisers in the soil-plant cycle. Plants 2022, 11, 3288. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J. The rising threat of atmospheric CO2: a review on the causes, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Environments 2023, 10, 66.

- Edo, G.I.; Itoje-akpokiniovo, L.O.; Obasohan, P.; Ikpekoro, V.O.; Samuel, P.O.; Jikah, A.N.; Nosu, L.C.; Ekokotu, H.A.; Ugbune, U.; Oghroro, E.E.A. Impact of environmental pollution from human activities on water, air quality and climate change. Ecological Frontiers 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mora, C.; Spirandelli, D.; Franklin, E.C.; Lynham, J.; Kantar, M.B.; Miles, W.; Smith, C.Z.; Freel, K.; Moy, J.; Louis, L.V. Broad threat to humanity from cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions. Nature climate change 2018, 8, 1062-1071. [CrossRef]

- Babcock, R.C.; Bustamante, R.H.; Fulton, E.A.; Fulton, D.J.; Haywood, M.D.; Hobday, A.J.; Kenyon, R.; Matear, R.J.; Plagányi, E.E.; Richardson, A.J. Severe continental-scale impacts of climate change are happening now: Extreme climate events impact marine habitat forming communities along 45% of Australia’s coast. Frontiers in Marine Science 2019, 6, 466674.

- Guo, Y.; Naeem, A.; Mühling, K.H. Comparative effectiveness of four nitrification inhibitors for mitigating carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions from three different textured soils. Nitrogen 2021, 2, 155-166. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Sandoval, M.A.; Loick, N.; Pinochet, D.E.; López-Aizpun, M.; Rivero, M.J.; Cárdenas, L.M. N Losses from an Andisol via Gaseous N2O and N2 Emissions Increase with Increasing Ruminant Urinary–N Deposition Rate. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 254-265.

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P. Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Ipcc: 2014.

- Grace, P.; De Rosa, D.; Shcherbak, I.; Strazzabosco, A.; Rowlings, D.; Scheer, C.; Barton, L.; Wang, W.; Schwenke, G.; Armstrong, R.; et al. Revised emission factors for estimating direct nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen inputs in Australia’s agricultural production systems: a meta-analysis. Soil Research 2024, 62. [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Grafton, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bishop, P.; Davies, C.E.; McCurdy, M. Iron-rich sand promoted nitrate reduction in a study for testing of lignite based new slow-release fertilisers. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 864, 160949. [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Bishop, P.; Jeyakumar, P.; Grafton, M.; Davies, C.E.; McCurdy, M. Formulation and characterization of polyester-lignite composite coated slow-release fertilizers. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research 2023, 20, 307-320. [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Smith, C.J.; Wang, E.; Macdonald, B.; Wårlind, D. Modelling nitrous oxide emissions: comparing algorithms in six widely used agro-ecological models. Soil Research 2023, 61, 523-541.

- Maire, J.; Krol, D.; Pasquier, D.; Cowan, N.; Skiba, U.; Rees, R.; Reay, D.; Lanigan, G.J.; Richards, K.G. Nitrogen fertiliser interactions with urine deposit affect nitrous oxide emissions from grazed grasslands. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 290, 106784. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Cai, C.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X.; Peng, K.; Guo, R.; Wei, Z.; Wu, C.; Cheng, S.; Liao, Y. Direct and indirect monitoring methods for nitrous oxide emissions in full-scale wastewater treatment plants: A critical review. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 358, 120842. [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, V.R.N.; Romaniuk, R.I.; Lupi, A.M.; Gómez, F.M.; Korsakov, H.R.; Álvarez, C.R.; Ciarlo, E. Comparison of field measurement methods of nitrous oxide soil emissions: from the chamber to the vial. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2020, 44, e0190100. [CrossRef]

- Charteris, A.F.; Chadwick, D.R.; Thorman, R.E.; Vallejo, A.; de Klein, C.A.; Rochette, P.; Cárdenas, L.M. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Recommendations for deployment and accounting for sources of variability. Journal of Environmental Quality 2020, 49, 1092-1109. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; Sperlich, P.; Clough, T.; Kelliher, F.; McGeough, K.; Martin, R.; Moss, R. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Recommendations for air sample collection, storage, and analysis. Journal of Environmental Quality 2020, 49, 1110-1125.

- Lammirato, C.; Wallman, M.; Weslien, P.; Klemedtsson, L.; Rütting, T. Measuring frequency and accuracy of annual nitrous oxide emission estimates. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2021, 310, 108624. [CrossRef]

- de Klein, C.A.; Harvey, M.J.; Clough, T.J.; Petersen, S.O.; Chadwick, D.R.; Venterea, R.T. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Introduction, with health and safety considerations. Journal of Environmental Quality 2020, 49, 1073-1080.

- Rochette, P.; Eriksen-Hamel, N.S. Chamber measurements of soil nitrous oxide flux: are absolute values reliable? Soil Science Society of America Journal 2008, 72, 331-342.

- Faust, D.R.; Liebig, M.A. Effects of storage time and temperature on greenhouse gas samples in Exetainer vials with chlorobutyl septa caps. MethodsX 2018, 5, 857-864. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.; Ambus, P.; Arah, J.; Clayton, H.; Galle, B.; Griffith, D.; Hargreaves, K.; Klenzedtsson, L.; Lind, A.-M.; Maag, M. Nitrous oxide emission from an agricultural field: Comparison between measurements by flux chamber and micrometerological techniques. Atmospheric Environment 1996, 30, 4183-4190. [CrossRef]

- Rochette, P.; Bertrand, N. Soil air sample storage and handling using polypropylene syringes and glass vials. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 2003, 83, 631-637. [CrossRef]

- Grace, P.R.; van der Weerden, T.J.; Rowlings, D.W.; Scheer, C.; Brunk, C.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Rees, R.M.; Robertson, G.P.; Skiba, U.M. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Considerations for automated flux measurement. Journal of Environmental Quality 2020, 49, 1126-1140.

- Sturm, K.; Keller-Lehmann, B.; Werner, U.; Raj Sharma, K.; Grinham, A.R.; Yuan, Z. Sampling considerations and assessment of E xetainer usage for measuring dissolved and gaseous methane and nitrous oxide in aquatic systems. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods 2015, 13, 375-390.

- Collier, S.M.; Ruark, M.D.; Oates, L.G.; Jokela, W.E.; Dell, C.J. Measurement of greenhouse gas flux from agricultural soils using static chambers. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 2014, e52110.

- Laughlin, R.J.; Stevens, R.J. Changes in composition of nitrogen-15-labeled gases during storage in septum-capped vials. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2003, 67, 540-543. [CrossRef]

| N2O Standard | RMSE | MAE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GED | VP | VS | PEE | GED | VP | VS | PEE | |

| S1 (12.500) | 0.740 | 0.179 | 0.448 | 0.239 | 0.715 | 0.154 | 0.426 | 0.229 |

| S2 (6.250) | 0.254 | 0.141 | 0.231 | 0.074 | 0.245 | 0.124 | 0.209 | 0.073 |

| S3 (3.125) | 0.257 | 0.078 | 0.175 | 0.067 | 0.241 | 0.074 | 0.163 | 0.056 |

| S4 (1.563) | 0.311 | 0.154 | 0.224 | 0.147 | 0.304 | 0.151 | 0.221 | 0.146 |

| S5 (0.781) | 0.176 | 0.026 | 0.085 | 0.051 | 0.164 | 0.020 | 0.084 | 0.047 |

| S6 (0.391) | 0.080 | 0.029 | 0.048 | 0.044 | 0.080 | 0.025 | 0.046 | 0.039 |

| Evacuation Method | Storage Method | Parameter | Standard N2O gas concentration (ppm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (12.500) | S2 (6.250) | S3 (3.125) | S4 (1.563) | S5 (0.781) | S6 (0.391) | |||

| GED | SM | RMSE | 0.740 | 0.254 | 0.257 | 0.311 | 0.176 | 0.080 |

| MAE | 0.715 | 0.245 | 0.241 | 0.304 | 0.164 | 0.08 | ||

| EVM | RMSE | 0.457 | 0.164 | 0.111 | 0.196 | 0.084 | 0.061 | |

| MAE | 0.432 | 0.142 | 0.082 | 0.184 | 0.075 | 0.06 | ||

| EVM | % Increase | 2.40 | 1.72 | 5.49 | 9.56 | 14.43 | 6.36 | |

| VS | SM | RMSE | 0.448 | 0.231 | 0.175 | 0.224 | 0.085 | 0.048 |

| MAE | 0.426 | 0.209 | 0.163 | 0.221 | 0.084 | 0.046 | ||

| EVM | RMSE | 0.370 | 0.200 | 0.112 | 0.140 | 0.048 | 0.023 | |

| MAE | 0.338 | 0.151 | 0.092 | 0.127 | 0.040 | 0.019 | ||

| EVM | % Increase | 0.73 | 0.96 | 2.38 | 7.02 | 6.24 | 7.63 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).