Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

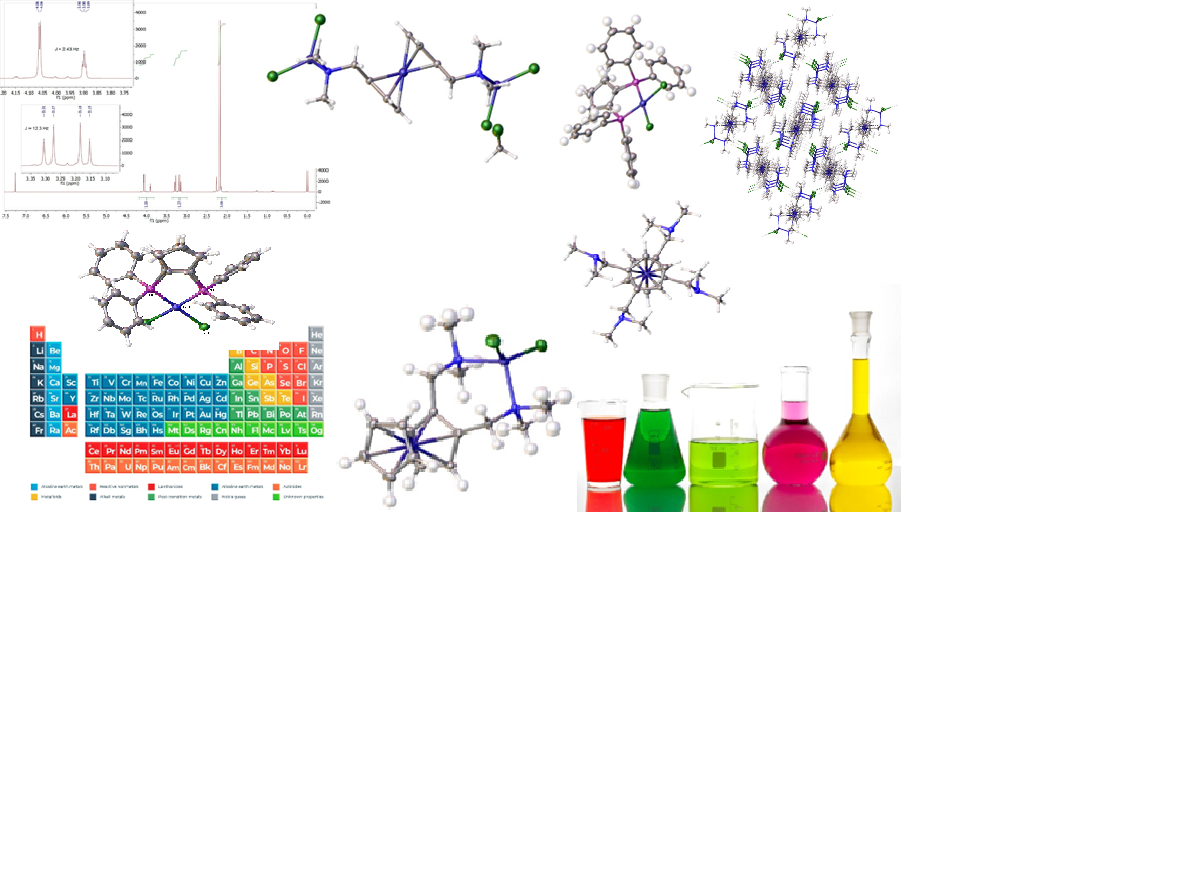

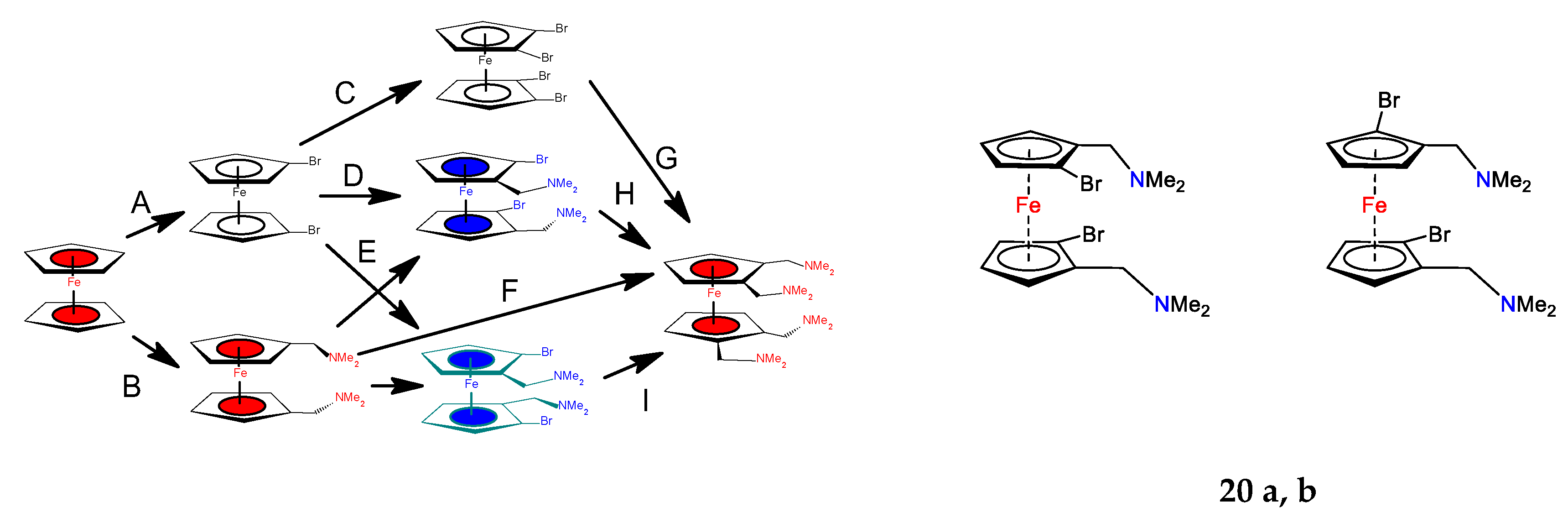

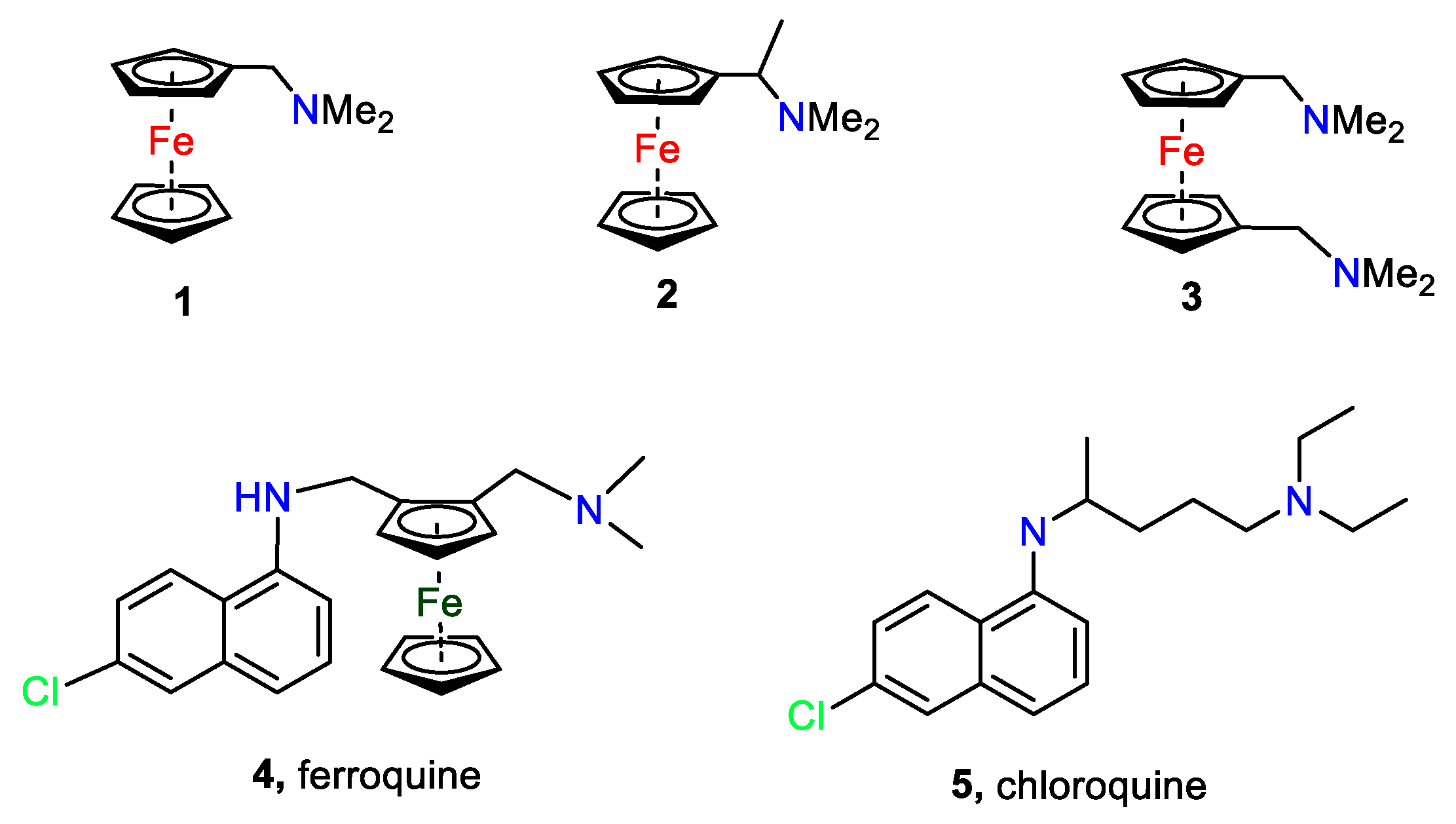

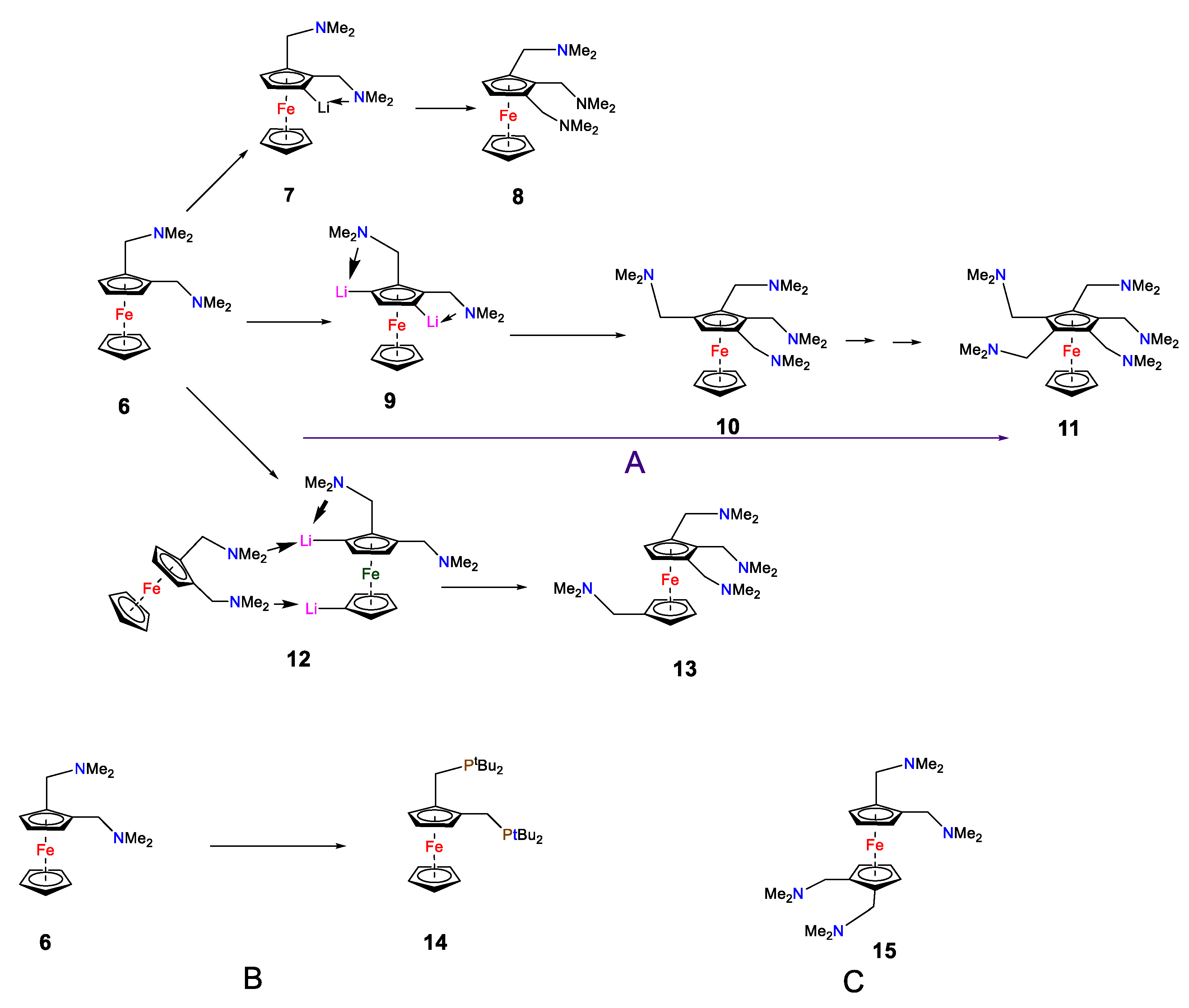

Abstract

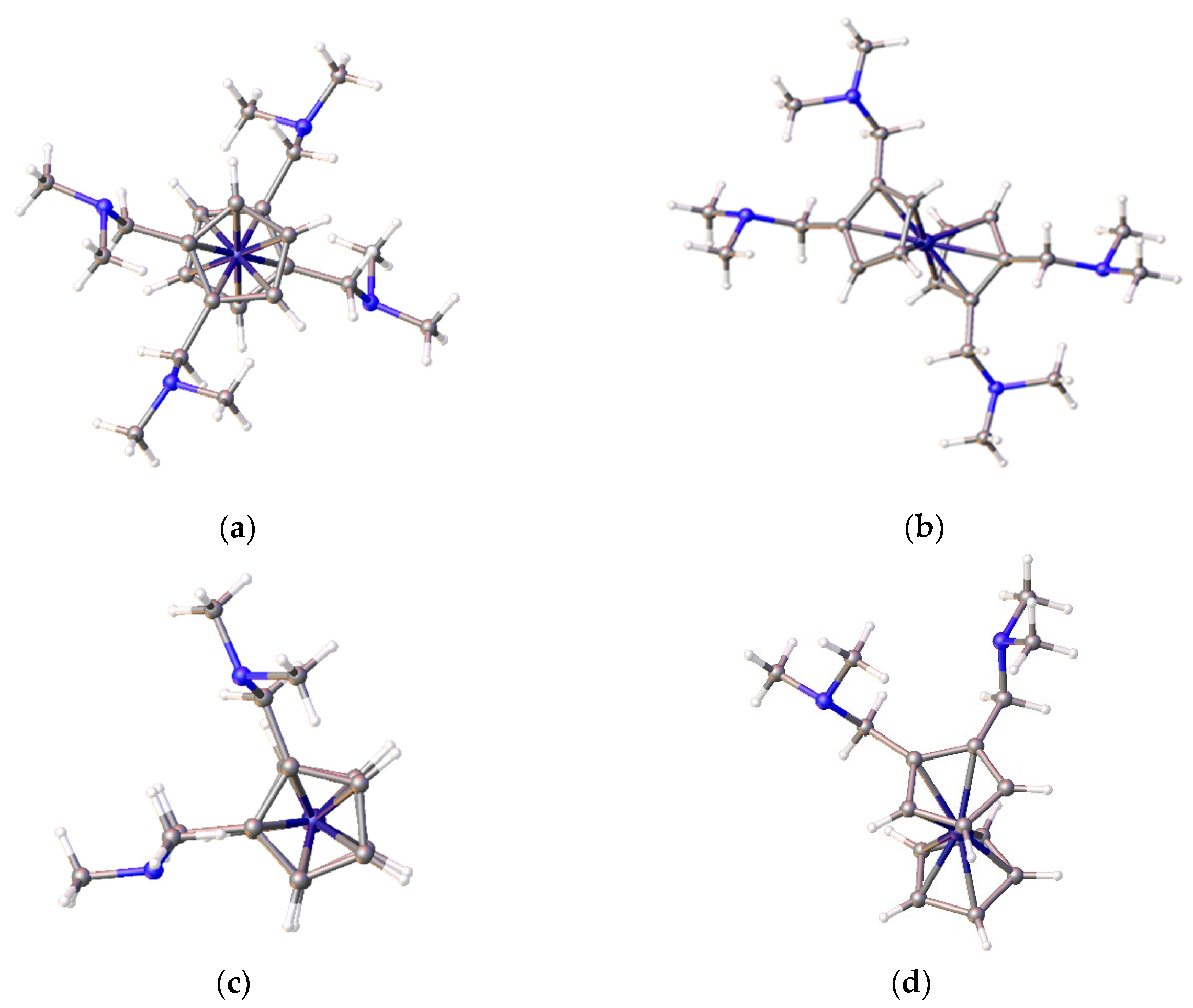

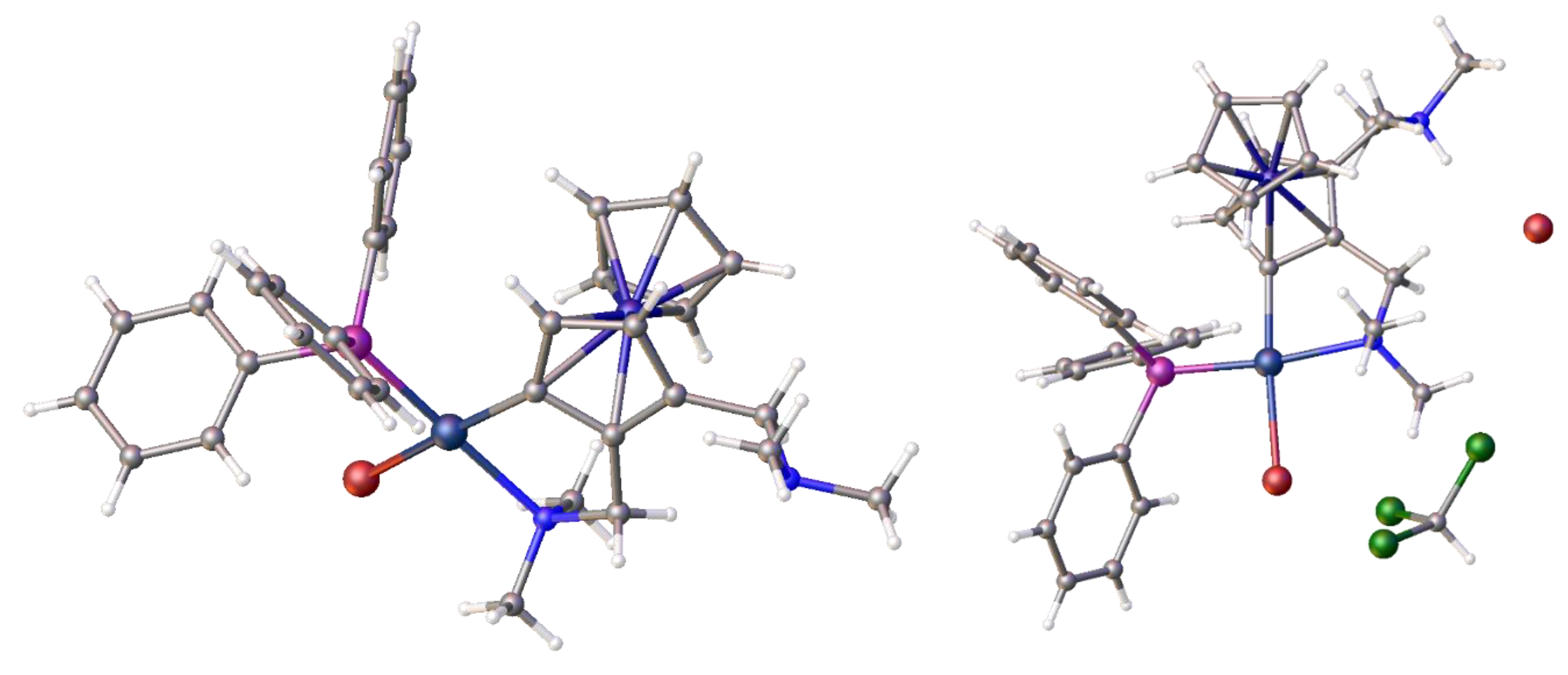

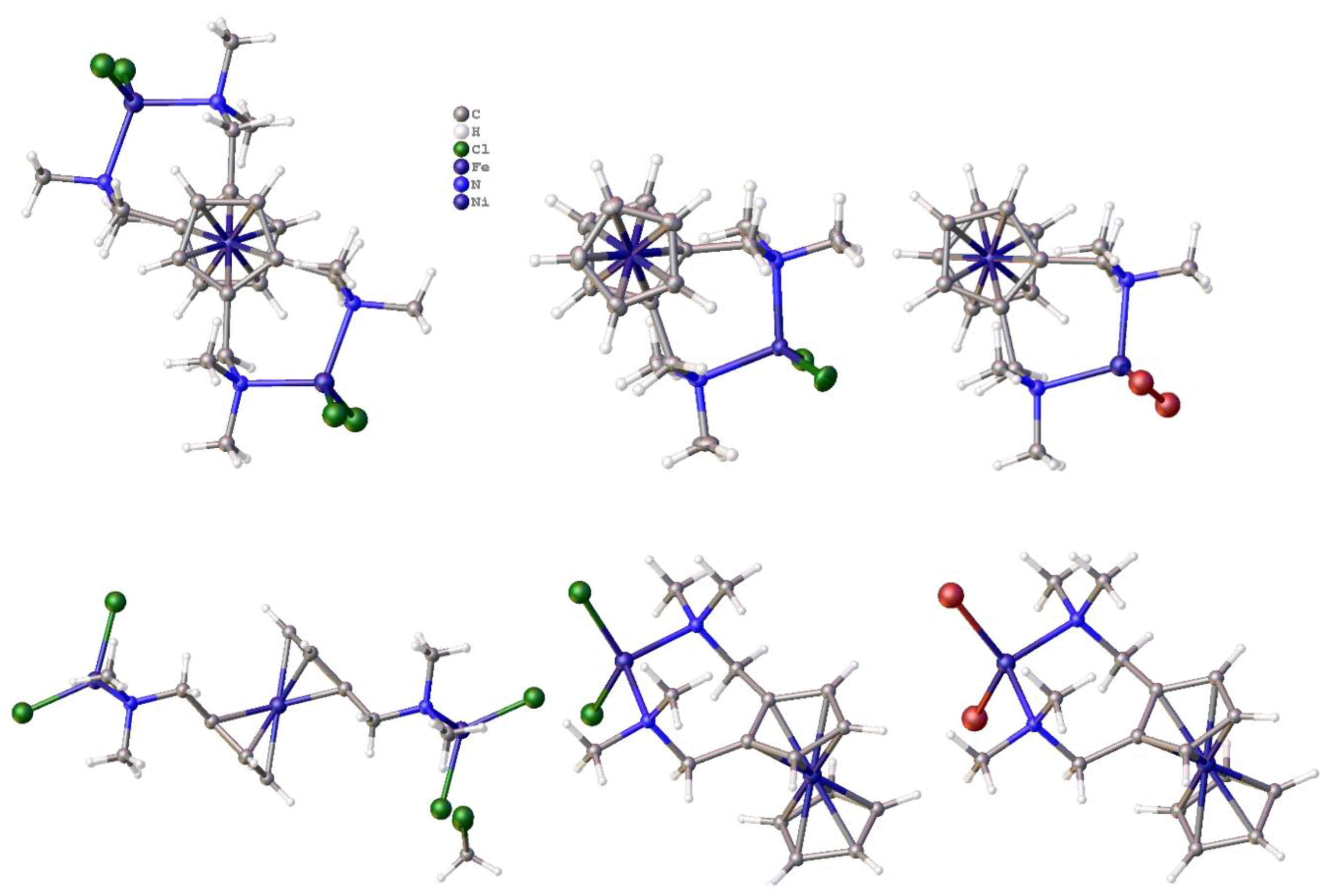

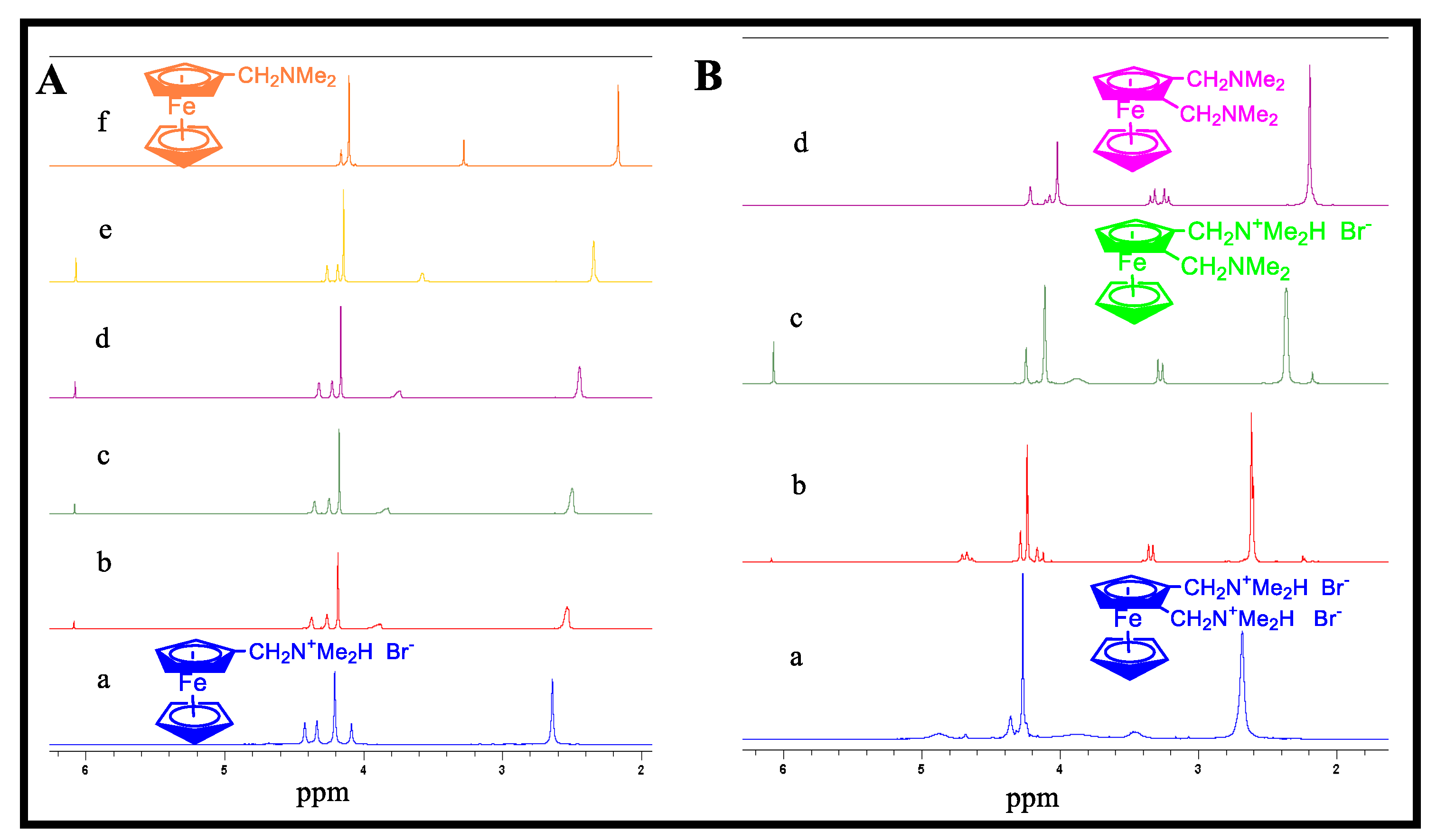

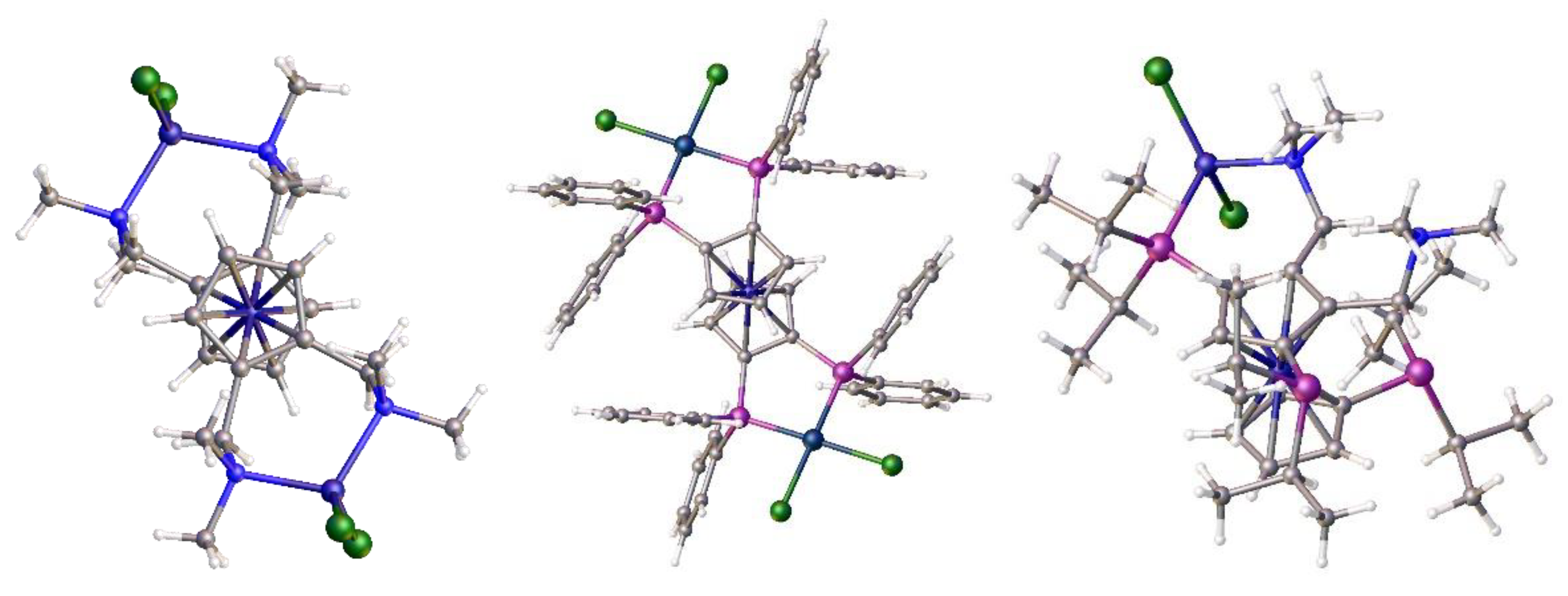

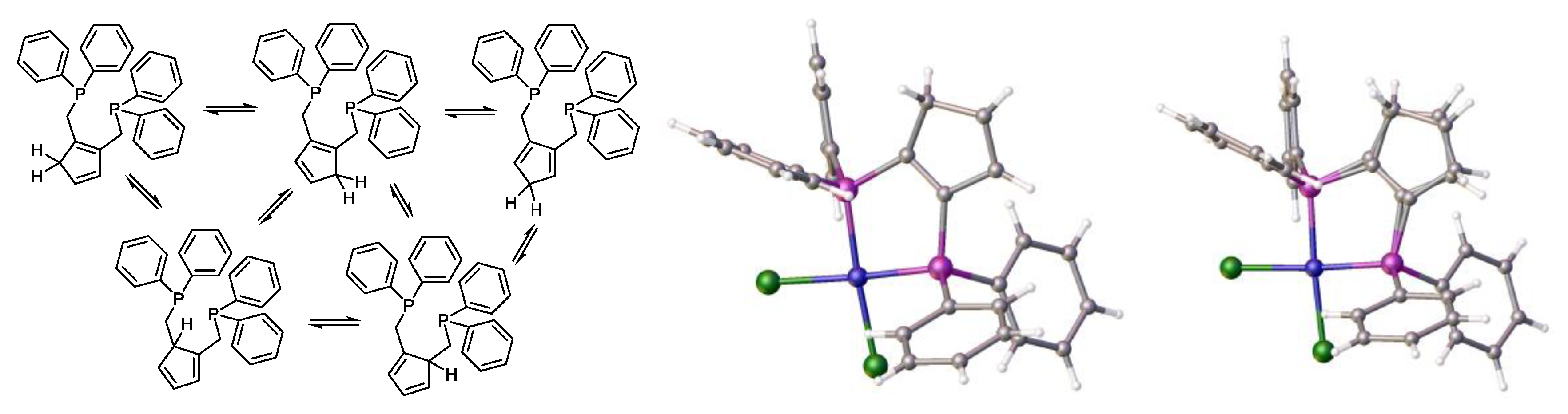

The family of N,N-dimethylaminomethylferrocenes is one of the most important in ferrocene chemistry. They serve as precursors for a range of anti-malaria and anti-tumour medicinal compounds in addition to being key precursors for ferrocene ligands in the Lucite alpha process. A brief discussion on the importance of, and the synthesis of N,N-dimethylaminomethyl-substituted ferrocenes preludes the synthesis of the new ligand 1,1´,2,2´-tetrakis-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocene. The crystal structure of this compound is reported and a comparison is made with its disubstituted analogue, 1,2-bis-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocene. The tetrahedral nickel dichloride complexes of both these ligands have been crystallographically characterised. Finally, a pointer to future research in the area is given which includes a discussion of a new method to extract ferrocenylmethylamines from mixtures using additives and a new synthetic avenue from substituted cyclopentadiene itself.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

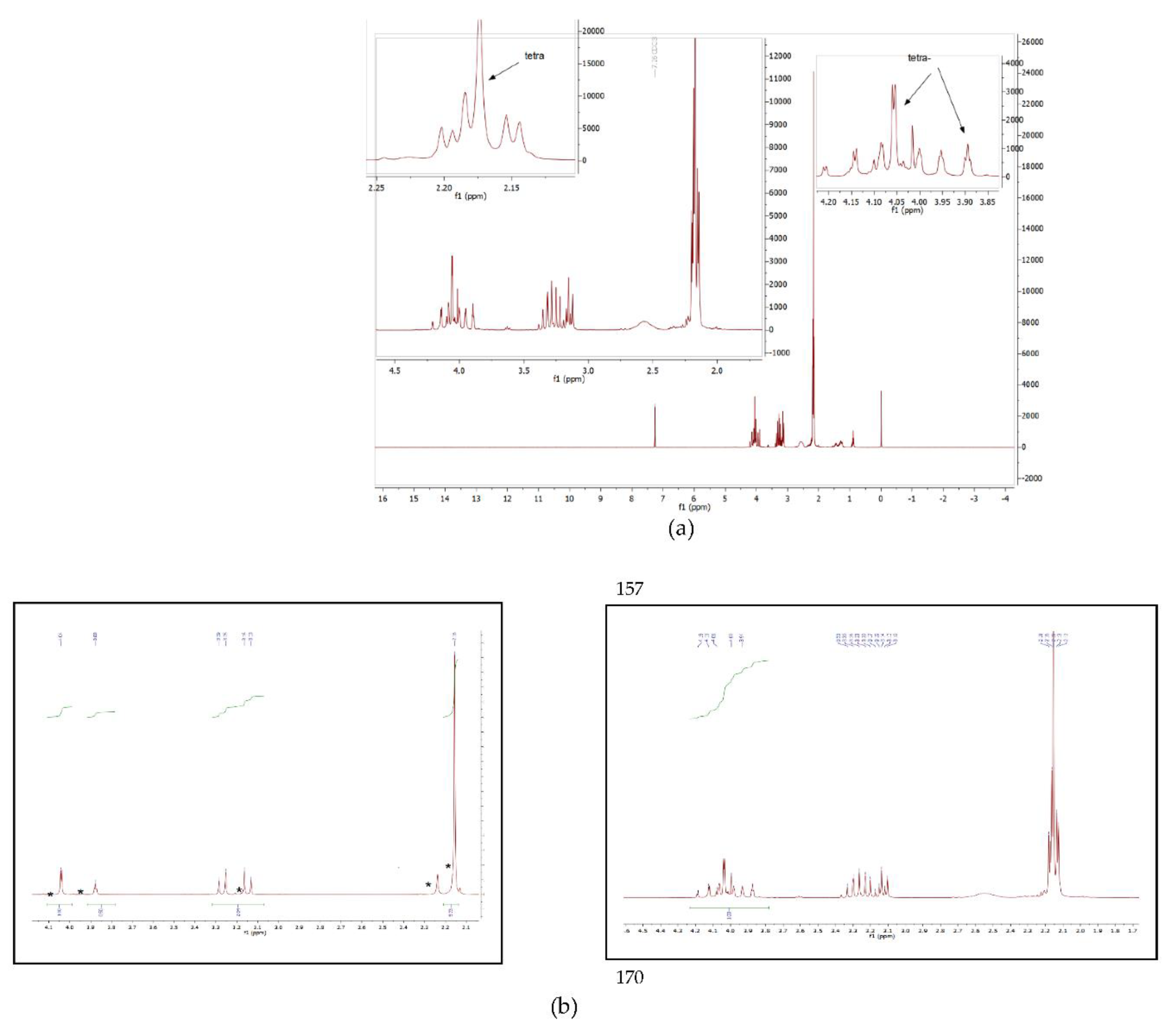

2.2. Additional Information and Future Pointers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthetic Work

3.2. 1,2-Bis-(N,N-Dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocene (6) [44,45]

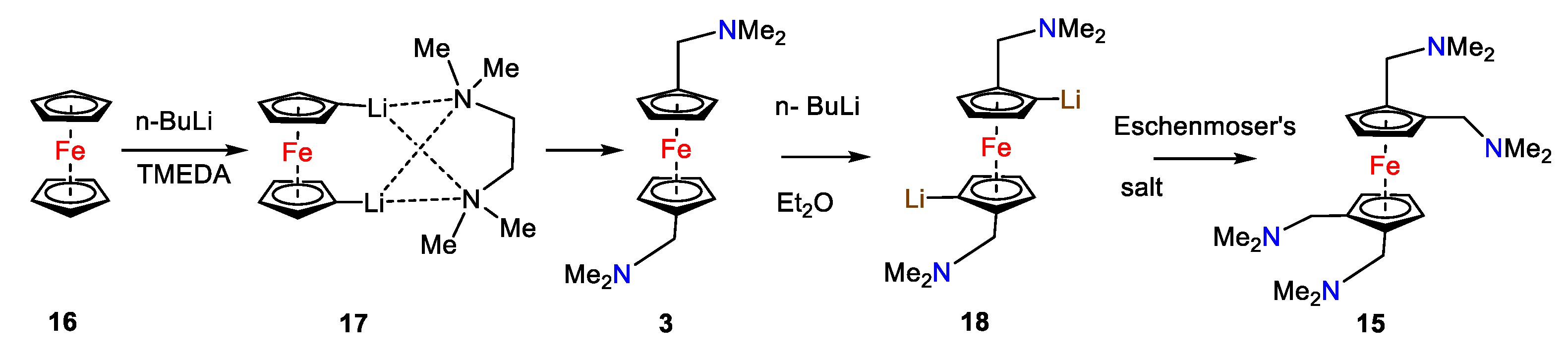

3.3. 1,2,1′,2′ -Tetrakis(N,N-Dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocene 15. (Original Method)

3.4. Preparation of Nickel Complex of 1,2,1′,2′-Tetra-(N,N-Dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocene

3.5. Alternative Synthetic Method for Compound 15

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaouen, G.; Vessières, A.; Top, S. Ferrocifen type anti-cancer drugs. Chem. Soc. Revs,, 2015, 44, 8802-8817. [CrossRef]

- Neuse, E.W. Macromolecular ferrocene compounds as cancer drug models. J. Inorg. Organometal. Polym. Mat., 2005, 215, 3-31. [CrossRef]

- Gasser, G.; Ott, I.; Metzler-Nolte, N. Organometallic Anticancer Compounds, J. Medicinal Chem., 2011, 54, 3-25. [CrossRef]

- Gielen, M.; Tiekink, E.R. eds., 2005. Metallotherapeutic drugs and metal-based diagnostic agents: the use of metals in medicine. John Wiley & Sons. 10.1002/0470864052.

- Ornelas, C., Application of ferrocene and its derivatives in cancer research. New J. Chem., 2011, 35, 1973-1985. [CrossRef]

- Paprocka, R.; Wiese-Szadkowska, M.; Janciauskiene, S.; Kosmalski, T.; Kulik, M.; Helmin-Basa, A., Latest developments in metal complexes as anticancer agents. Coord. Chem. Revs., 2022, 452, 214307. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, E. “Metallocenes as Target Specific Drugs for Cancer Treatment.” Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2012, 393, 36-52. [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, K.E.; Baldwin, W.; Sheats, J.E. Metallocenes in biochemistry, microbiology & medicine, J. Organometal. Chem., 2020, 905, 281-306. [CrossRef]

- Sansook, S.; Storm, H.-H.; Ocasio, C.; Spencer, J. Ferrocenes in medicinal chemistry; a personal perspective, J. Organometal. Chem., 2020, 905, 121017. [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Ferrocene-Based Compounds with Antimalaria/Anticancer Activity. Molecules, 2019, 24, 3604. [CrossRef]

- Blackie, M.AL.; Chibale, K. Metallocene antimalarials: the continuing quest. Metal-Based Drugs., 2007, online, 495123. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, M.P.; Burrows, J.N.; Duparc, S.; Moehrle, J.; Wells, T.N. The global pipeline of new medicines for the control and elimination of malaria. Malaria journal, 2012, 11, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.M., Hughes, D.D., Murphy, P.J., Horton, P.N., Coles, S.J., de Biani, F.F., Corsini, M.; Butler, I.R., Synthetic Route to 1, 1′,2,2′-Tetraiodoferrocene That Avoids Isomerization and the Electrochemistry of Some Tetrahaloferrocenes. Organometallics, 2021, 40, pp.2496-2503.

- Butler, I.R., Beaumont, M., Bruce, M.I., Zaitseva, N.N., Iggo, J.A., Robertson, C., Horton, P.N.; Coles, S.J., Synthesis and Structures of 1, 1′, 2-Tribromoferrocene, 1, 1′, 2, 2′-Tetrabromoferrocene, 1,1′,2,2′-Tetrabromoruthenocene: Expanding the Range of Precursors for the Metallocene Chemist’s Toolkit. Aust. J. Chem., 2020, 74, .204-210.

- Butler, I.R., 2021. Sitting Out the Halogen Dance. Room-Temperature Formation of 2,2′-Dilithio-1,1′-dibromoferrocene. TMEDA and Related Lithium Complexes: A Synthetic Route to Multiply Substituted Ferrocenes. Organometallics, 2021, 40,, .3240-3244.

- Butler, I.R., Evans, D.M., Horton, P.N., Coles, S.J.; Murphy, P.J., 1, 1′,2,2′-Tetralithioferrocene and 1,1′ 2,2′ 3 3′-Hexalithioferrocene: Useful Additions to Ferrocene Precursor Compounds. Organometallics, 2021, 40,, 600-605.

- Horton, P.N., Coles, S.J., Clegg, W., Harrington, R.W.,Butler, I.R., A Rapid General Synthesis and the Spectroscopic Data of 2,2′-Bis-(di-isopropylphosphino)-1, 1′-dibromoferrocene,(bpdbf), 1,1′,2,2′-Tetrakis-(di-isopropylphosphino) Ferrocene,(tdipf) and Related Ligands: Taking dppf into the Future. Inorganics, 2025, 13, .10-.

- Lindsay, J.K.; Hauser, C.R. Aminomethylation of Ferrocene to Form N, N-Dimethylaminomethylferrocene and Its Conversion to the Corresponding Alcohol and Aldehyde. J. Org. Chem., 1957, 22, 355-358. [CrossRef]

- Lednicer, D; Hauser, C.R. N, N-Dimethylaminomethylferrocene Methiodide: Iron, cyclopentadienyl [(dimethylaminomethyl) cyclopentadienyl]-, methiodid. Org. Synth., 2003, 40, .31-31. [CrossRef]

- Gokel, G.W; Ugi, I.K. Preparation and resolution of N, N-dimethyl-o-ferrocenylethylamine. An advanced organic experiment. J. Chem. Ed. 1972, 49, p.294. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, R.; Hübener, G.; Ugi, I., Chiral sulfoxides from (R)-α-dimethylaminoethylferrocene. Tetrahedron, 41, 941-947. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.C.; Rivest, R. Coordination complexes of some group (IV) halides: Preparation and ir spectra of the complexes of group (IV) halides with ferrocene acetonitrile and N, N-dimethylaminomethylferrocene as ligands. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem., 1970, 32, 1579-1584. [CrossRef]

- Grelaud, G.; Roisnel, T.; Dorcet, V.; Humphrey, M.G.; Paul, F.; Argouarch, G. Synthesis, reactivity, and some photochemistry of ortho-N, N-dimethylaminomethyl substituted aryl and ferrocenyl pentamethylcyclopentadienyl dicarbonyl iron complexes. J. Organometal. Chem., 2013, 741, 47-58. [CrossRef]

- Picart-Goetgheluck, S.; Delacroix, O.; Maciejewski, L.; Brocard, J. High yield synthesis of 2-substituted (N, N-dimethylaminomethyl) ferrocenes. Synthesis, 2000(10), 1421-1426. [CrossRef]

- Butler, I.R.; Cullen, W.R. The synthesis of primary, secondary, and tertiary ferrocenylethylamines. Can. J. Chem., 1983, 61, 2354-2358. [CrossRef]

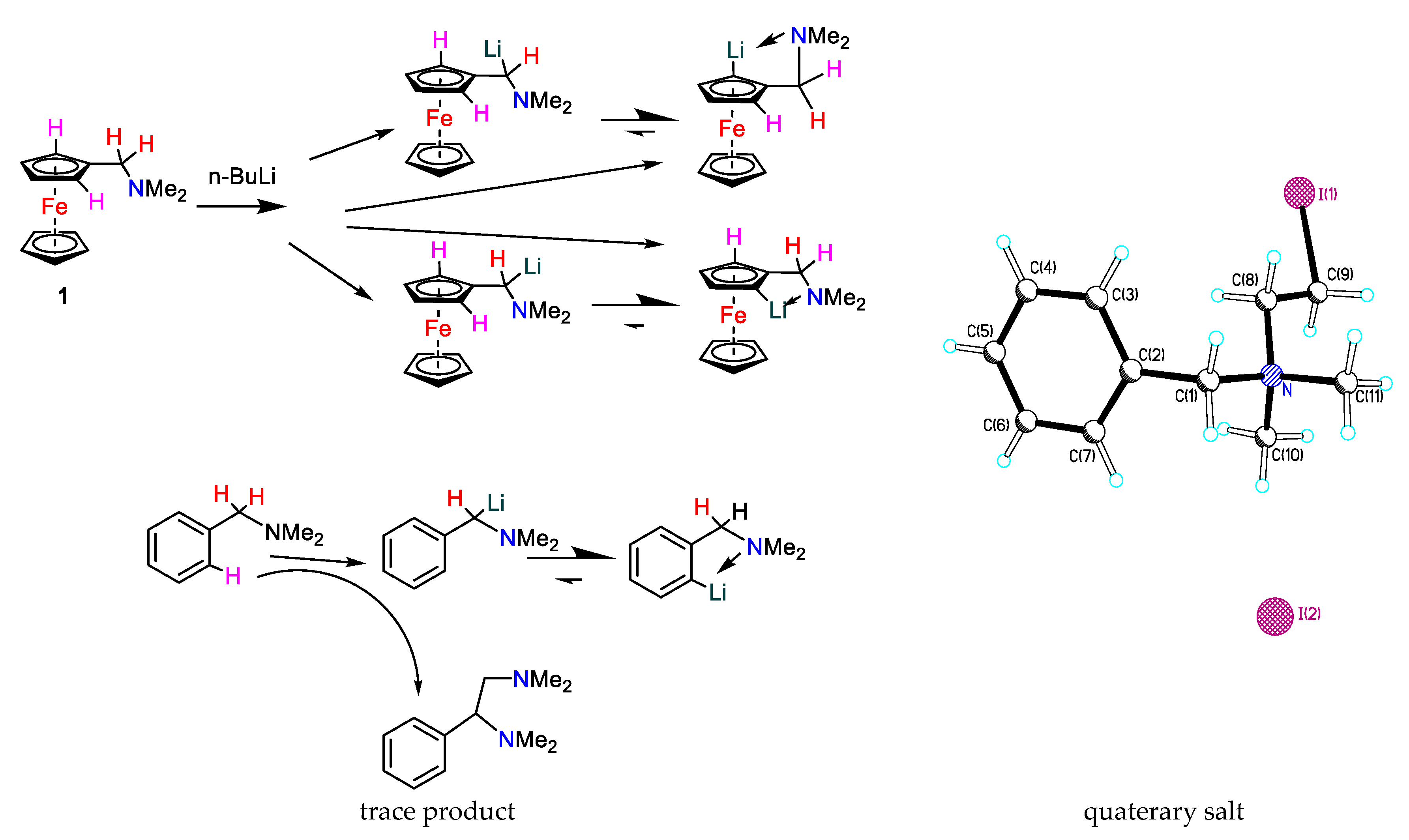

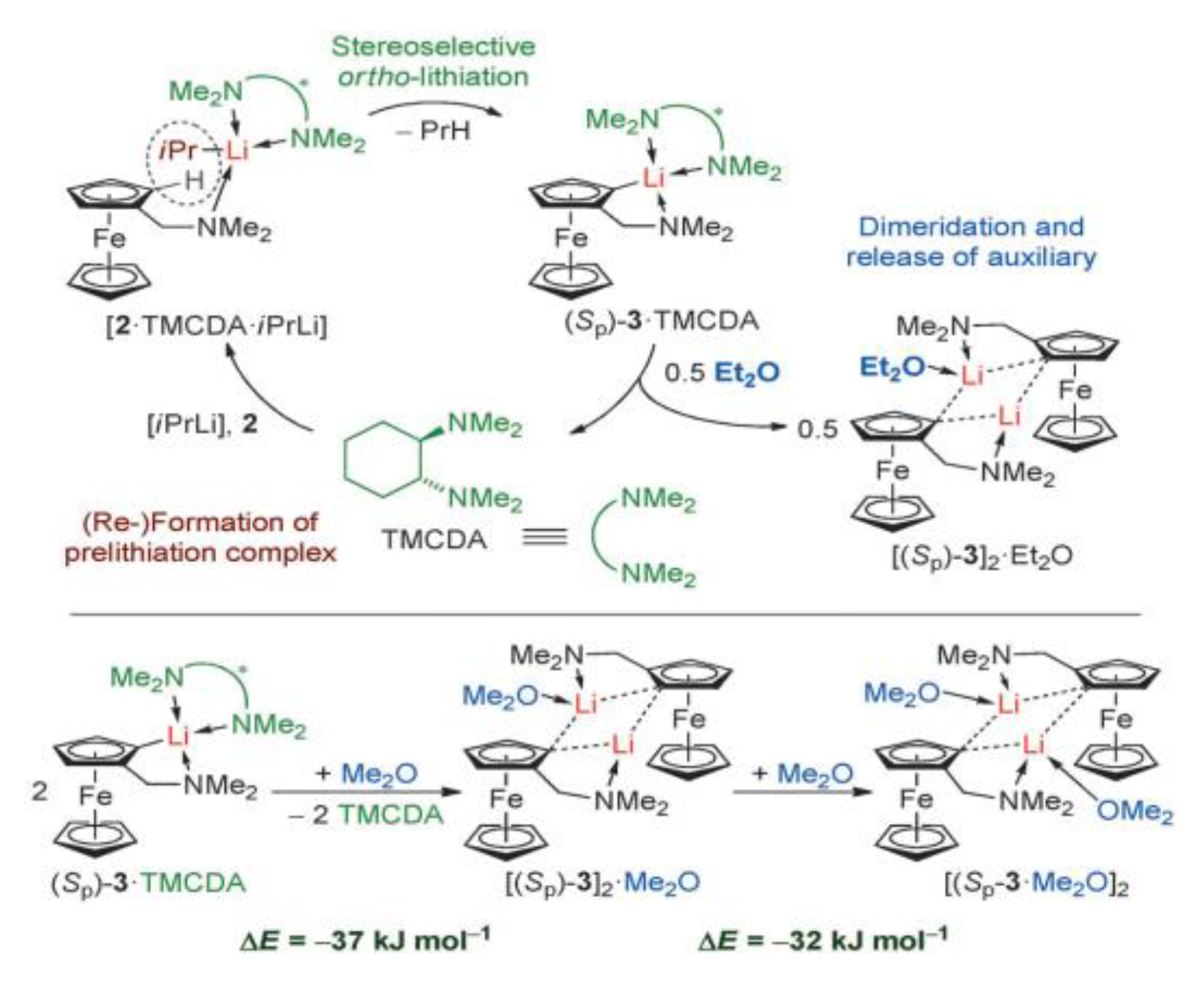

- Butler, I.R; Cullen, W.R.; Herring, F.G.; Jagannathan, N.R. α-N, N-Dimethylaminoethylferrocene. A nuclear magnetic resonance study relating to stereoselective metalation. Can. J. Chem., 1986, 64, 667-669. [CrossRef]

- Colbert, M.C.; Lewis, J.; Long, N.J.; Raithby, P.R.; Bloor, D.A.; Cross, G.H. The synthesis of chiral ferrocene ligands and their metal complexes. J. Organometal. Chem., 1997, 531, 183-190. [CrossRef]

- Blaser, H.U.; Brieden, W.; Pugin, B.; Spindler, F.; Studer, M.; Togni, A. Solvias Josiphos ligands: from discovery to technical applications. Topics in catalysis, 2002, 19, 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Blaser, H.U.; Pugin, B.; Spindler, F.; Mejía, E.; Togni, A. Josiphos ligands: from discovery to technical applications. Privileged Chiral Ligands and Catalysts, Wiley, 2011, 93-136. [CrossRef]

- Treiber, M.; Wernsdorfer, G.; Wiedermann, U.; Congpuong, K.; Sirichaisinthop, J.; Wernsdorfer, W.H.; Sensibilität von Plasmodium vivax gegenüber Chloroquin, Mefloquin, Artemisinin und Atovaquon im Nordwesten Thailands. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 2011, 123, 20-25. [CrossRef]

- Bray, P.G.; Martin, R.E.; Tilley, L.; Ward, S.A.; Kirk, K.; Fidock, D.A. Defining the role of PfCRT in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance. Molecular microbiology, 2005, 56, 323-333. [CrossRef]

- Held, J., Supan, C., Salazar, C.L., Tinto, H., Bonkian, L.N., Nahum, A., Moulero, B., Sié, A., Coulibaly, B., Sirima, S.B. and Siribie, M., 2015. Ferroquine and artesunate in African adults and children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, dose-ranging, non-inferiority study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2015, 15, pp.1409-1419. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(15)00079-1/abstract.

- Ecker, A.; Lehane, A.M.; Clain, J.; Fidock, D.A. PfCRT and its role in antimalarial drug resistance. Trends in parasitology, 2012, 28, 504-514. https://www.cell.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1016%2Fj.pt.2012.08.002&pii=S1471-4922%2812%2900142-0.

- Biot, C.; Castro, W.; Botté, C.Y.; Navarro, M. The therapeutic potential of metal-based antimalarial agents: implications for the mechanism of action. Dalton Trans., 2012, 41, 6335-6349. [CrossRef]

- Dive, D.; Biot, C. Ferrocene conjugates of chloroquine and other antimalarials: the development of ferroquine, a new antimalarial. ChemMedChem., 2007, 3, 383-393. [CrossRef]

- Biot, C.; Taramelli, D.; Forfar-Bares, I.; Maciejewski, L.A.; Boyce, M.; Nowogrocki, G.; Brocard, J.S.; Basilico, N;, Olliaro, P.; Egan, T.J. Insights into the mechanism of action of ferroquine. Relationship between physicochemical properties and antiplasmodial activity. Molecular pharmaceutics, 2005, 2, 185-193. [CrossRef]

- Faustine, D.; Sylvain Bohic, Slomianny, C.; Morin, J.-C.; Thomas, P.; Kalamou, H.; Guérardel, Y.; Cloetens, P.; Jamal Khalife, J.; Biot, C., In situ nanochemical imaging of label-free drugs: a case study of antimalarials in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes, Chem. Commun., 2012, 48, 910-912. [CrossRef]

- Biot, C.; Nosten, F.; Fraisse, L.; Ter-Minassian, D.; Khalife, J.; Dive, D. The antimalarial ferroquine: from bench to clinic. Parasite: journal de la Société Française de Parasitologie, 2011, 18, 207-214. [CrossRef]

- Delhaes, L.; Biot, C.; Berry, L.; Delcourt, P.; Maciejewski, L.A.; Camus, D.; Brocard, J.S.; Dive, D. Synthesis of ferroquine enantiomers: first investigation of effects of metallocenic chirality upon antimalarial activity and cytotoxicity. ChemBioChem, 2002, 3, 418-423. [CrossRef]

- Keiser, J.; Vargas, M.; Rubbiani, R.; Gasser, G.; Biot, C. In vitro and in vivo antischistosomal activity of ferroquine derivatives. Parasites & vectors, 2014, 7, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Wani, W.A.; Jameel, E.; Baig, U.; Mumtazuddin, S.; Hun, L.T. Ferroquine and its derivatives: new generation of antimalarial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem., 2015, 101, 534-551. [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Klonoff, D.C.; Akram, J. Efficacy of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci., 2020, 24. 4539-4547 https://www.talkingaboutthescience.com/studies/HCQ/Meo2020.pdf.

- Gasmi, A.; Peana, M.; Noor, S.; Lysiuk, R.; Menzel, A.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Bjørklund, G. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19: the never-ending story. Appl. Microbiol. Biotech., 2021, 105, 1333-1343. [CrossRef]

- Butler, I.R.; Baker, P.K.; Eastham, G.R.; Fortune, K.M.; Horton, P.N.; Hursthouse, M.B., Ferrocenylmethylphosphines ligands in the palladium-catalysed synthesis of methyl propionate. Inorg. Chem. Commun., 2004, 7, 1049-1052. [CrossRef]

- Fortune, K.M.; Castel, C.; Robertson, C.M.; Horton, P.N.; Light, M.E.; Coles, S.J.; Waugh, M.; Clegg, W.; Harrington, R.W.; Butler, I.R. Ferrocenylmethylphosphanes and the Alpha Process for Methoxycarbonylation: The Original Story. Inorganics, 2021, 9, 57-. [CrossRef]

- Morris, K. An Investigation into the Synthesis of Phosphine-Based Ligands and Their Application in Pd-Catalysed Processes in the Production of Polymethylmethacrylate. Ph.D. Thesis, Bangor University, Bangor, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar].

- Glidewell, C.; Royles, B.J.; Smith, D.M. A simple high-yielding synthesis of ferrocene-1,1′-diylbis-(methyltrimethylammonium iodide). J. Organometal. Chem., 1997, 527, 259-261. [CrossRef]

- Fortune, K.M. Nitrogen Donor Complexes of Molybdenum and Tungsten and New Routes to bis-1,2 & tris-1,2,3 Substituted Ferrocenes. Ph.D. Thesis, Bangor University, Gwynedd, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar].

- Butler, I.R.; Horton, P.N.; Fortune, K.M.; Morris, K.; Greenwell, C.H.; Eastham, G.R.; Hursthouse, M.B., The first 1, 2, 3-tris (phosphinomethyl) ferrocene. Inorg. Chem. Commun., 2004, 7, 923-928. [CrossRef]

- Rausch,M.D.; Ciappenelli, D.J., Organometallic π-complexes XII. The metalation of benzene and ferrocene by n-butyllithium-N, N, N′, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine. J. Organomet. Chem., 1967, 10, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Meijboom, R.; Beagley, P,; Moss, J.R.; Roodt, A. Lithiated dimethylaminomethyl ferrocenes and ruthenocenes. J. Organometal. Chem,, 2006, 691, 916-920. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, E.S.; Pauson, P.L.; Sandhu, M.D,; Watts, W.E. Ferrocene derivatives. Part XXI. Lithiation of 1,1′-bis-(NN-dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocene, J. Chem. Soc. C, 1969, 2260-2263. [CrossRef]

- Butler, I.R.; Cullen, W.R.; Rettig, S.J., Synthesis of derivatives of [. alpha.(dimethylamino) ethyl] ferrocene via lithiation reactions and the structure of 2-[ alpha.-(dimethylamino) ethyl]-1, 1', 3-tris (trimethylsilyl) ferrocene. Organometallics, 1986, 5, 1320-1328. [CrossRef]

- Butler, I.R.; Cullen, W.R.; Reglinski, J.; Rettig, S.J. Ferrocenyllithium derivatives: lithiation of α-N, N-deimethylaminoethylferrocene and the single crystal X-ray structure of [(η5-C5H4Li) Fe (η5-C5H3LiCH (Me) NMe2)] 4 [LiOEt] 2 (TMED) 2., J. Organometal. Chem., 1983, 249, 183-194. [CrossRef]

- Steffen, P.; Unkelbach, C.; Christmann, M.; Hiller, W.; Strohmann, C. Catalytic and stereoselective ortho-lithiation of a ferrocene derivative. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2013, 52, 9836-9840 10.1002/anie.201303650.

- Krupp, A.; Wegge, J.; Otte, F., Kleinheider, J.; Wall, H.; Strohmann, C. Crystal structures of [(N, N-dimethylamino) methyl] ferrocene and (Rp, Rp)-bis {2-[(dimethylamino) methyl] ferrocenyl} dimethylsilane. Acta Crystallographica Section E: Crystallographic Communications, 2020, 76, 1437-1441. [CrossRef]

- Butler, I.R.; Williams, R.M.; Heeroma, A.; Horton, P.N.; Coles, S.J.; Jones, L.F. The Effect of Localized Magnetic Fields on the Spatially Controlled Crystallization of Transition Metal Complexes. Inorganics 2025, 13, 117. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).