Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

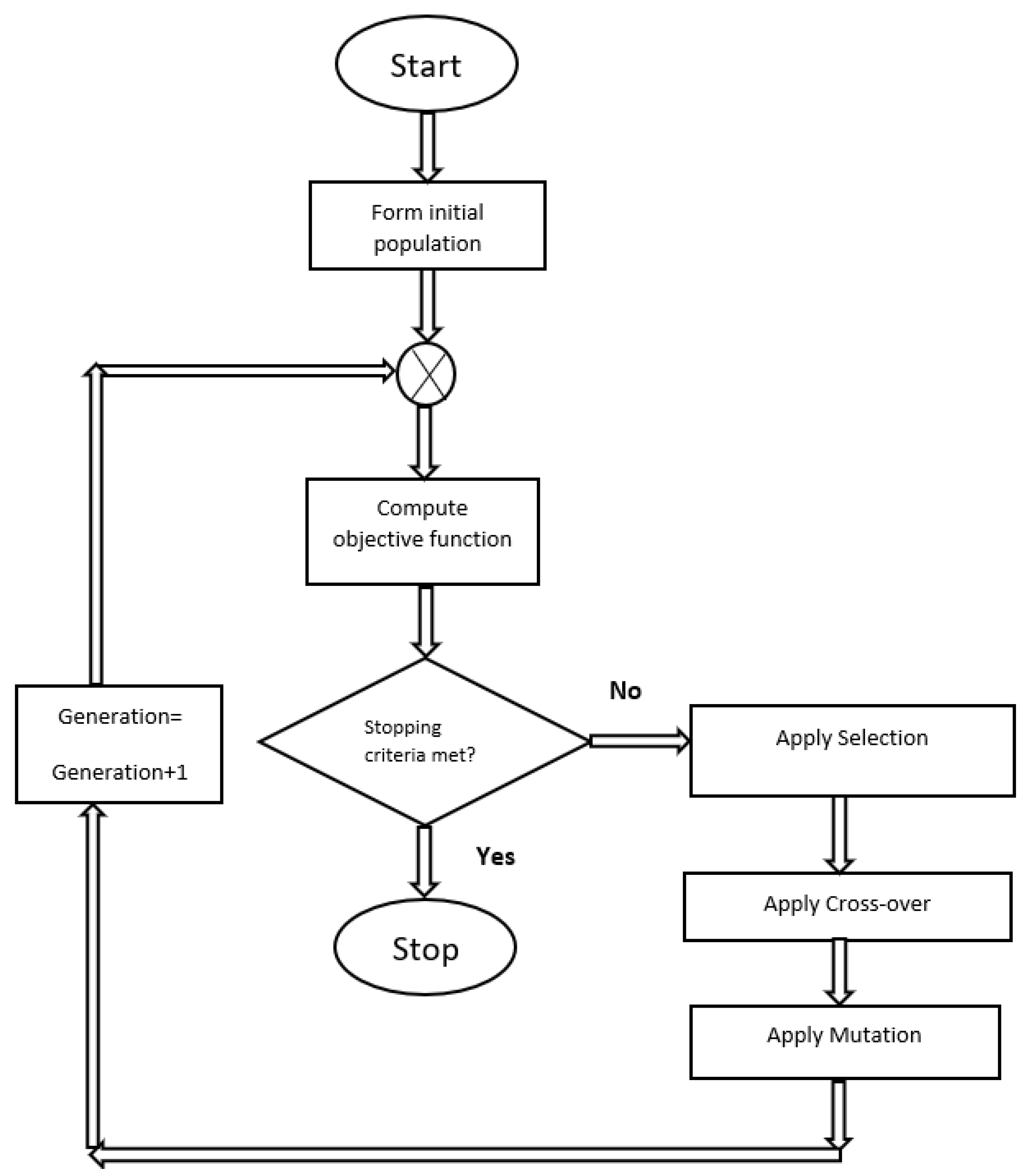

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

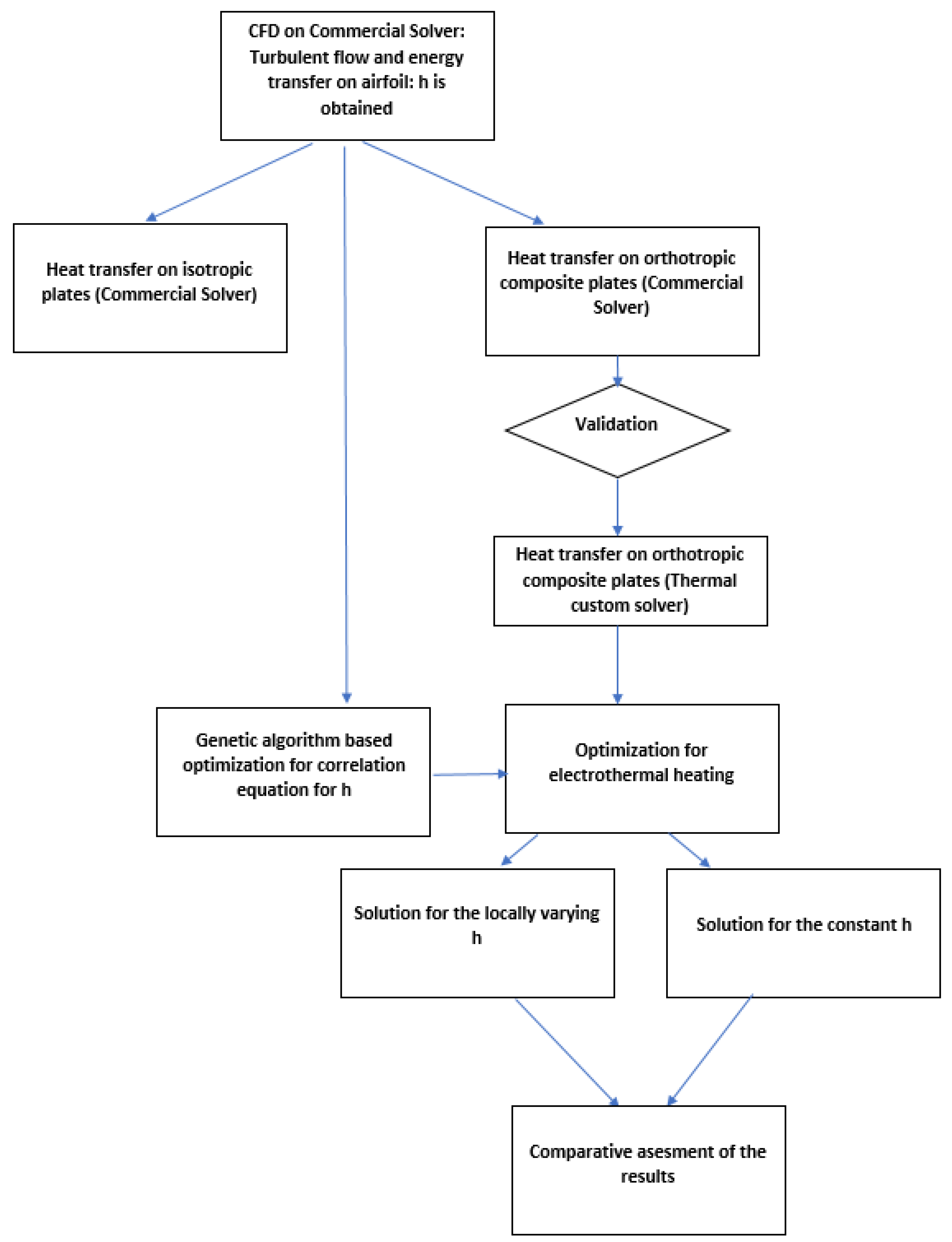

2. Method

3. Mathematical Equtions of Interest

4. Numerical Analysis

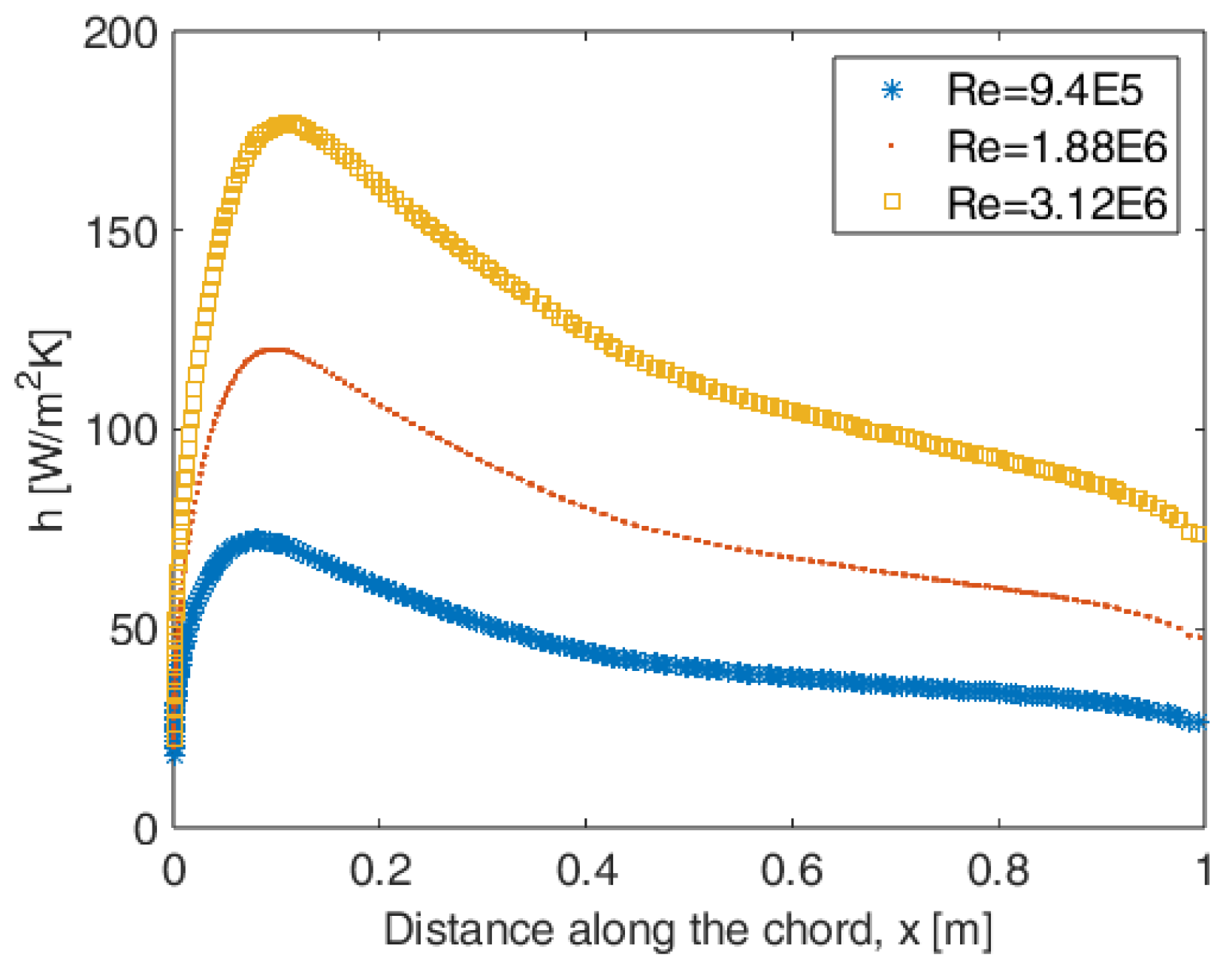

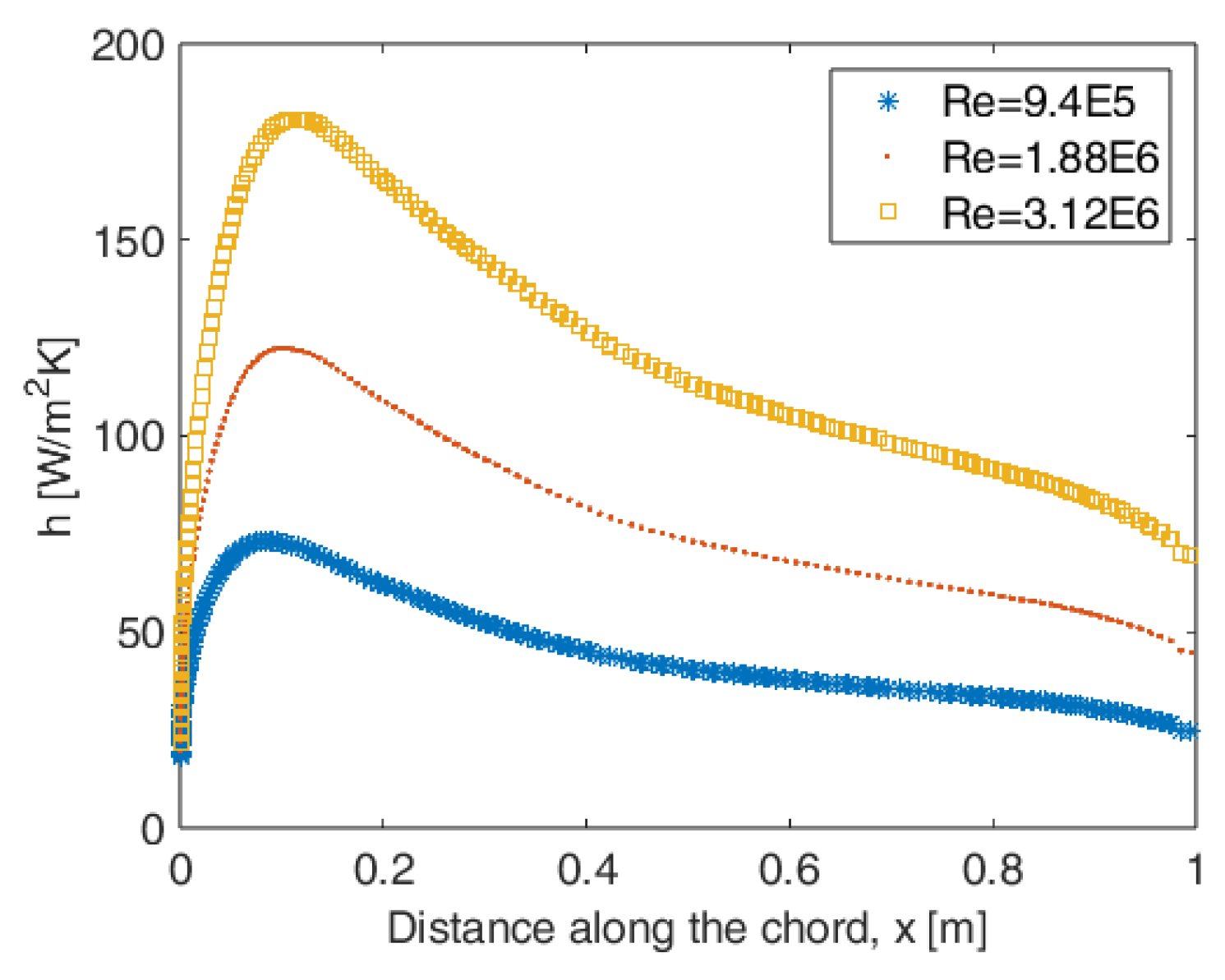

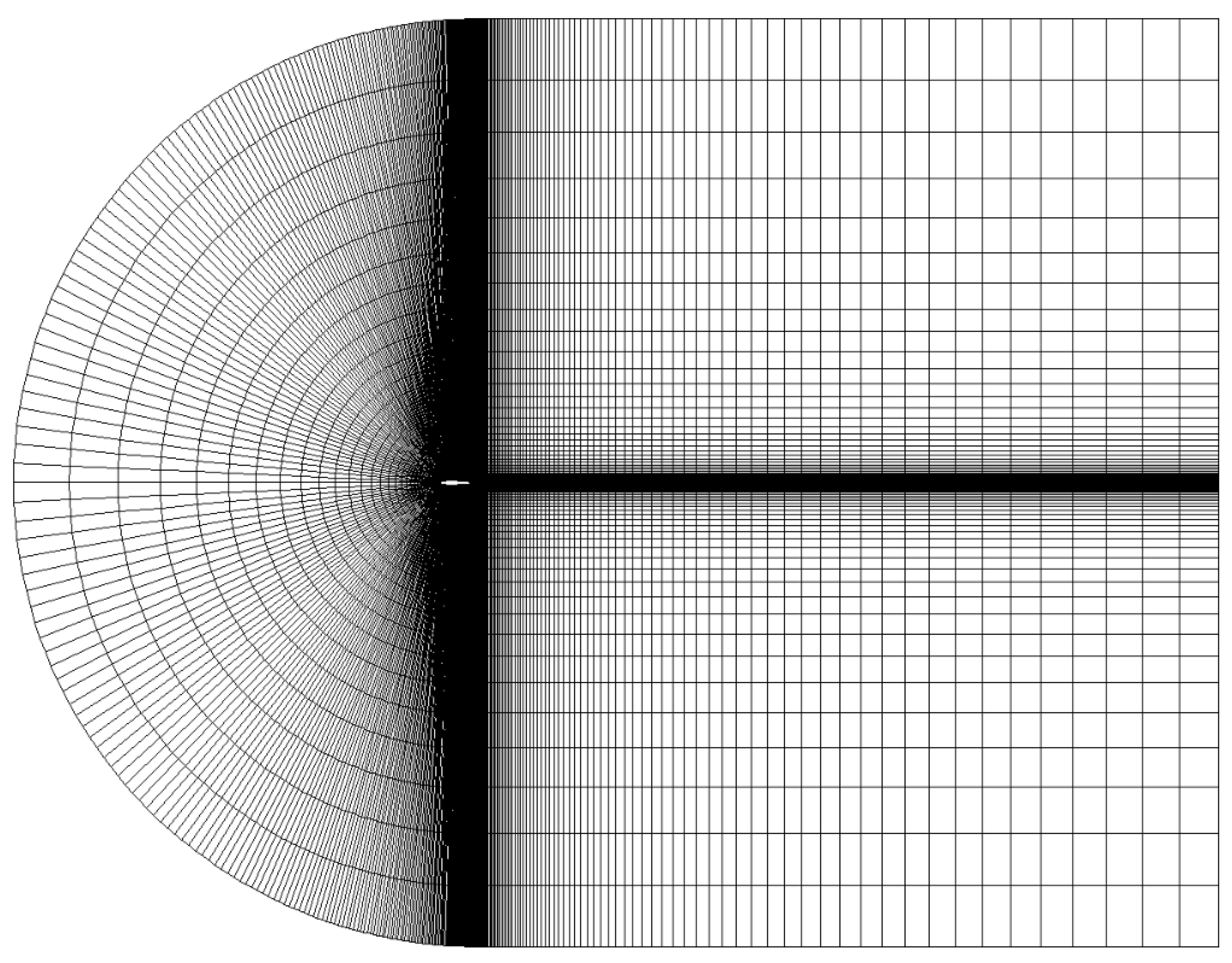

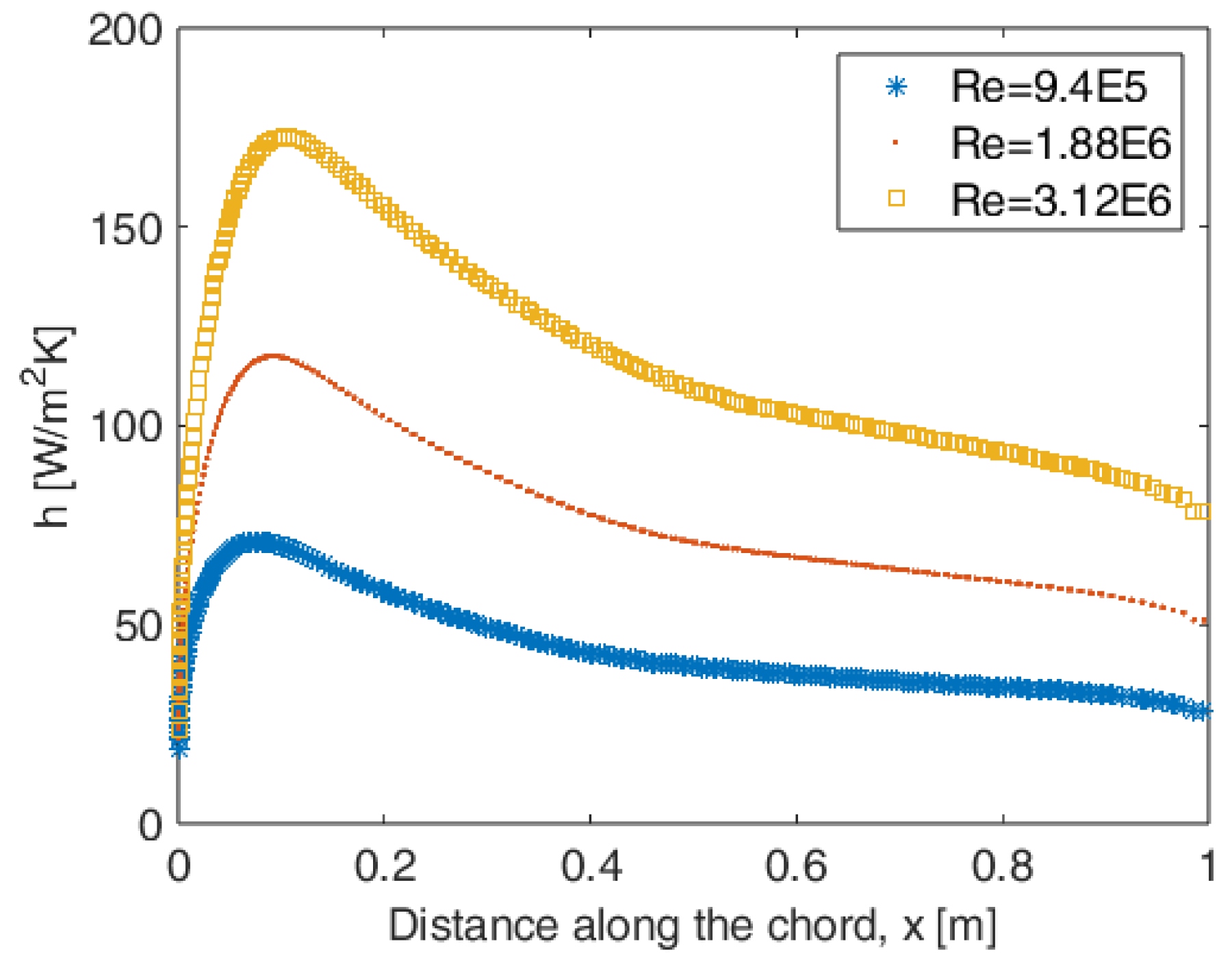

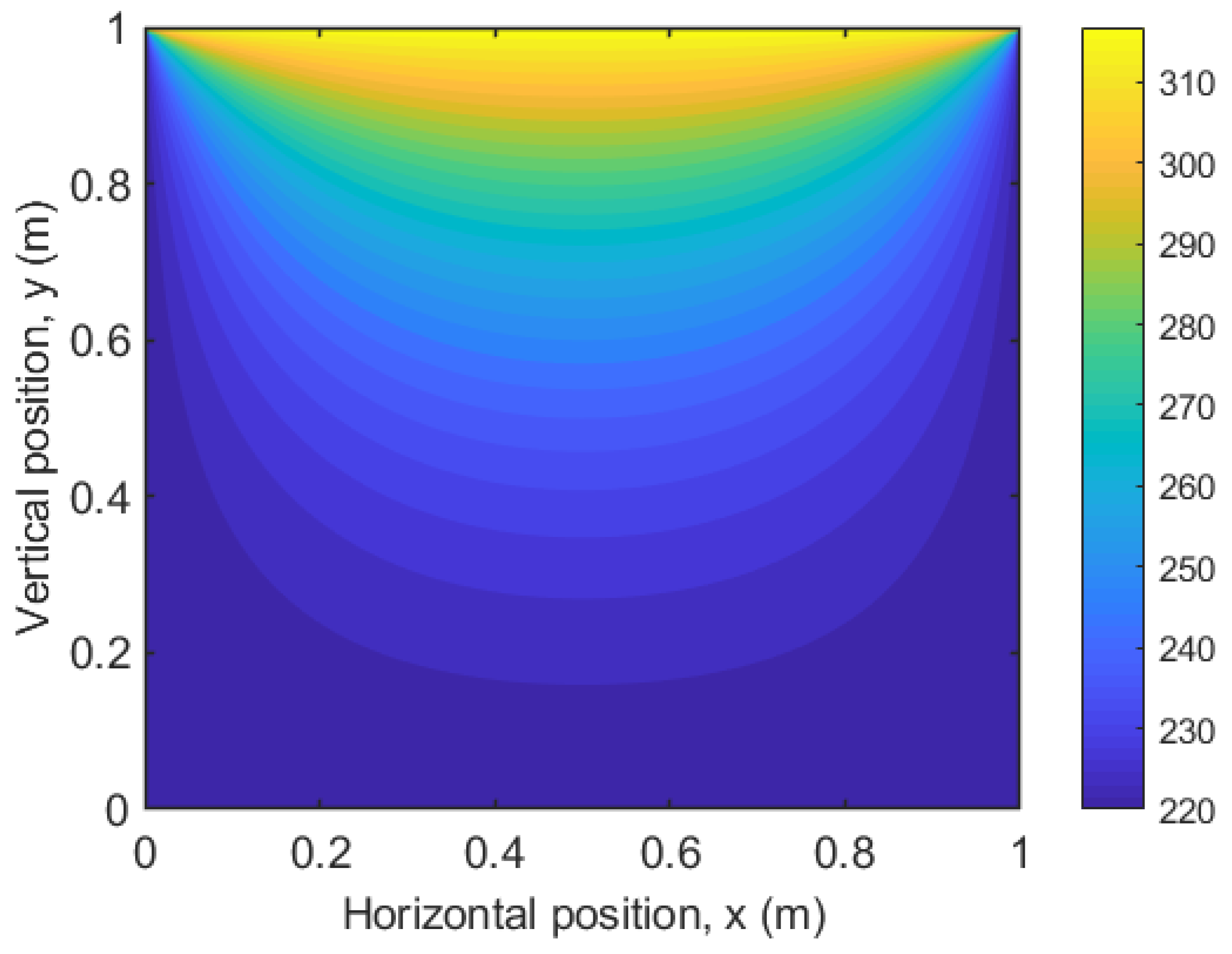

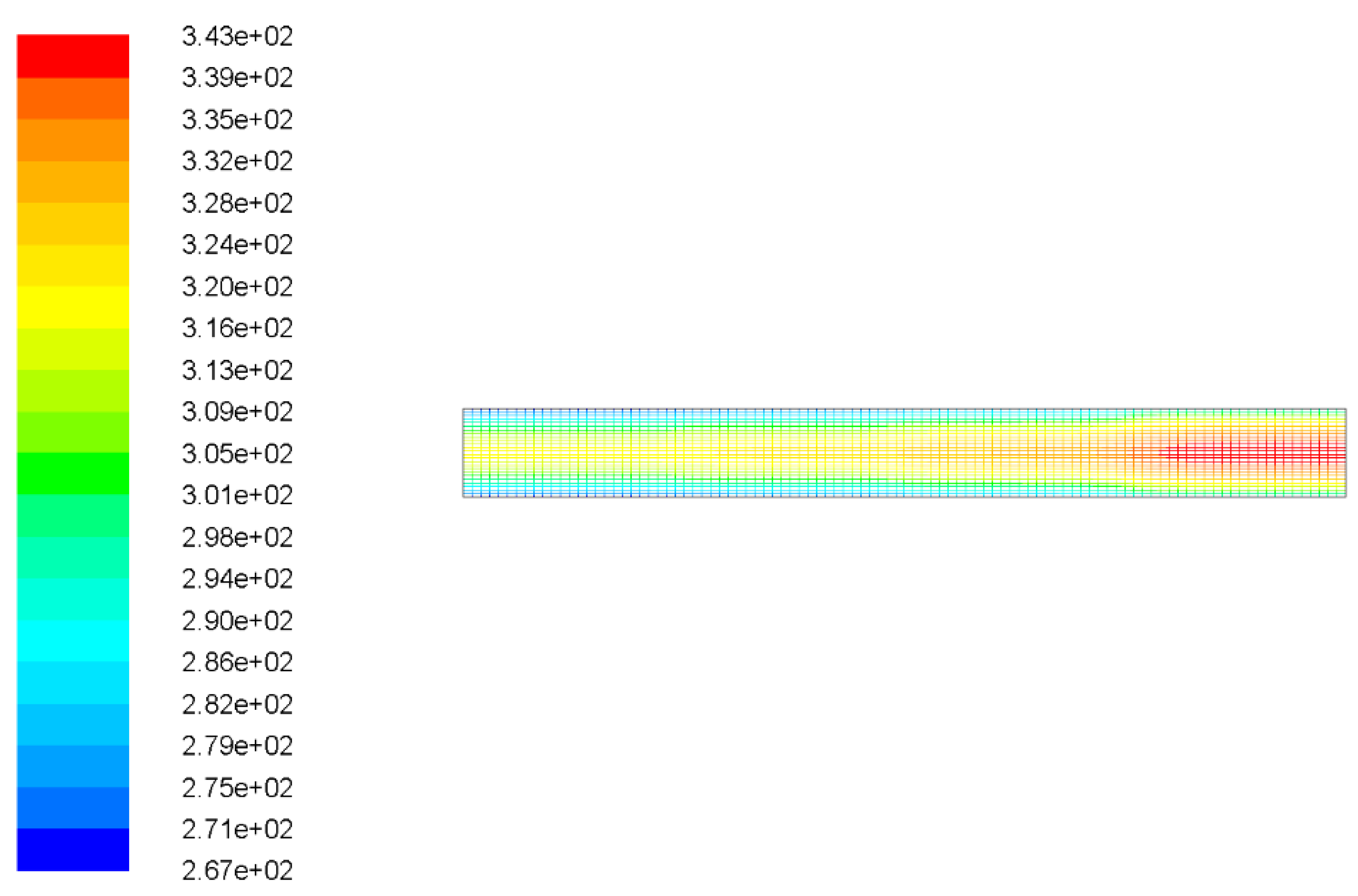

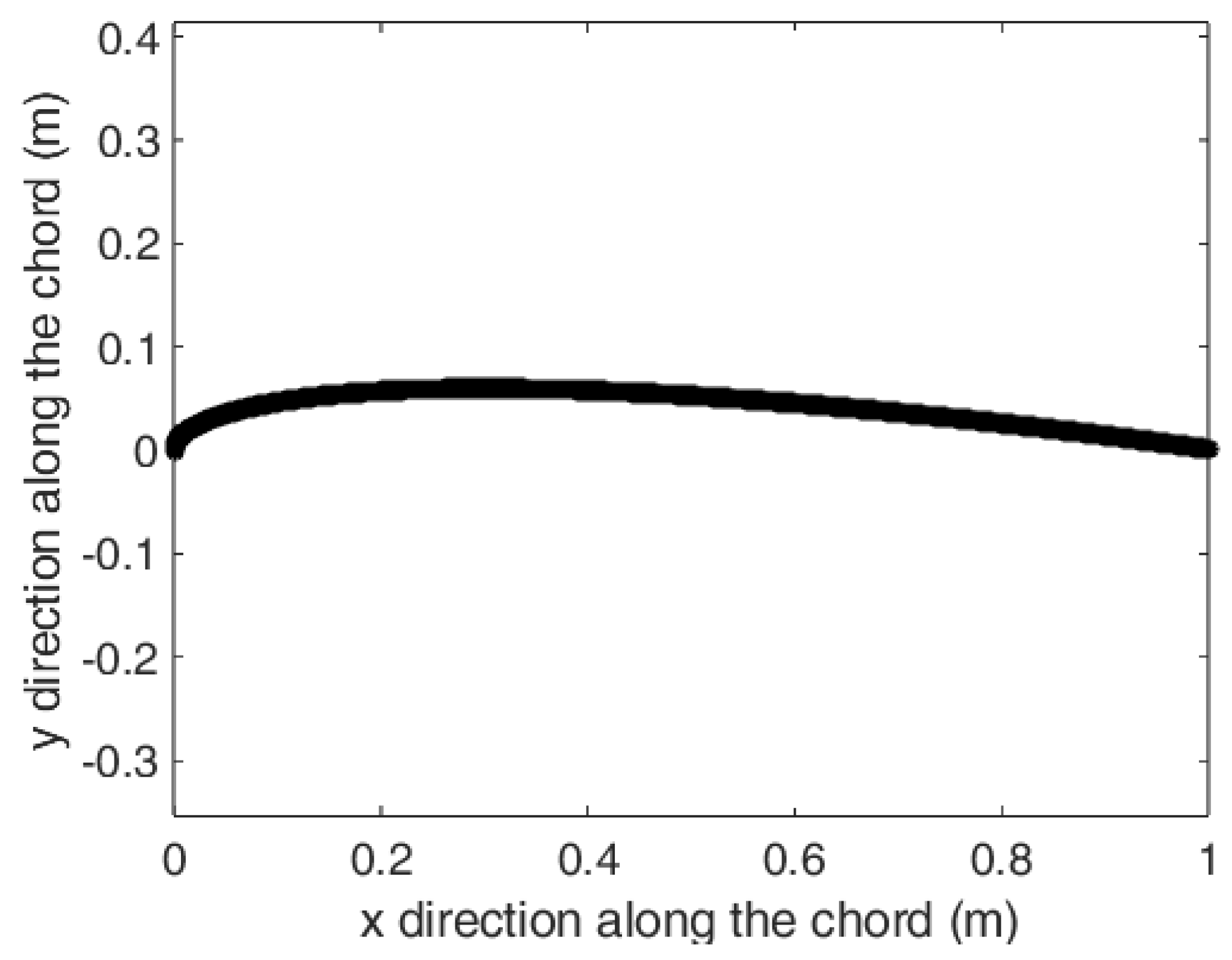

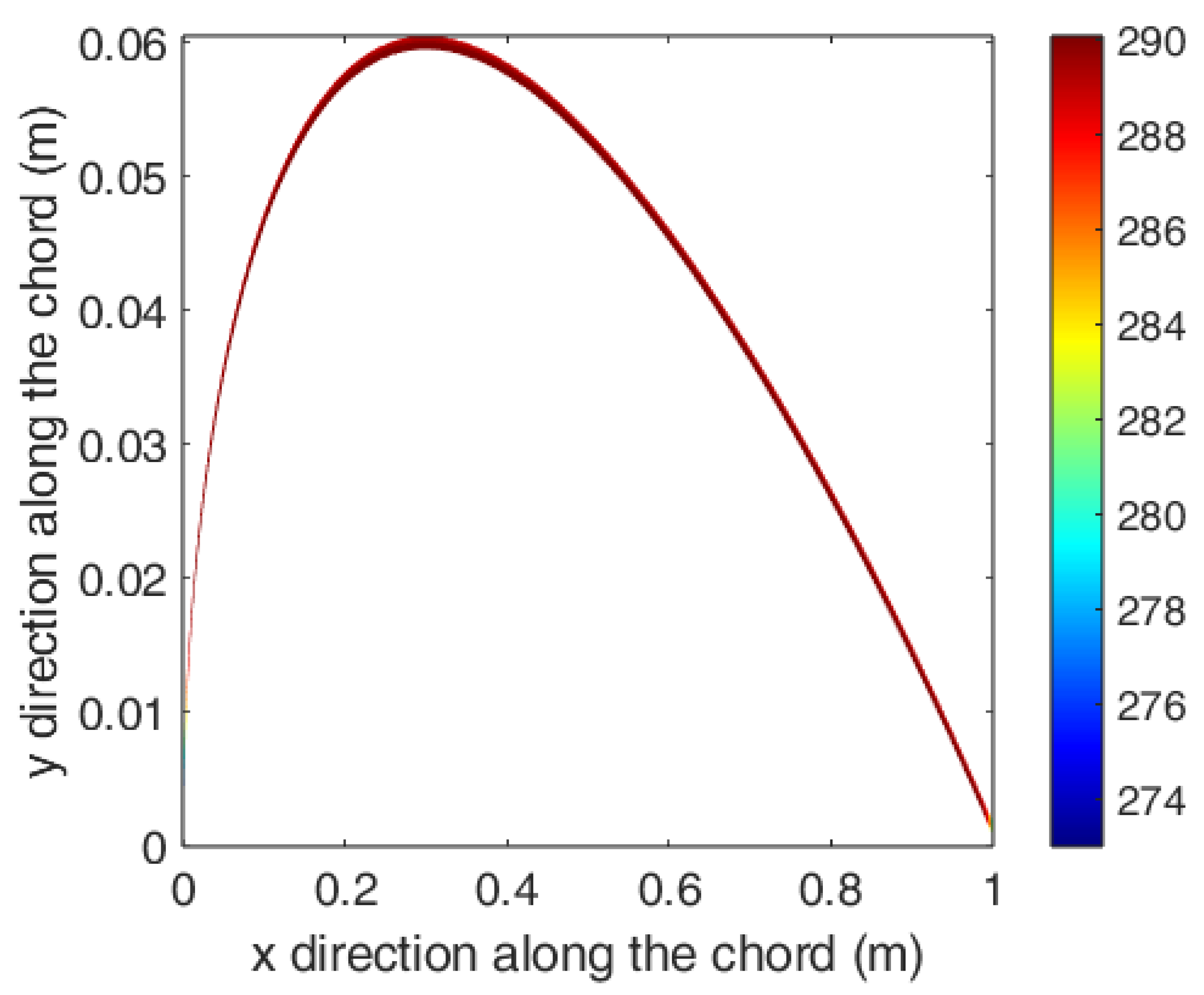

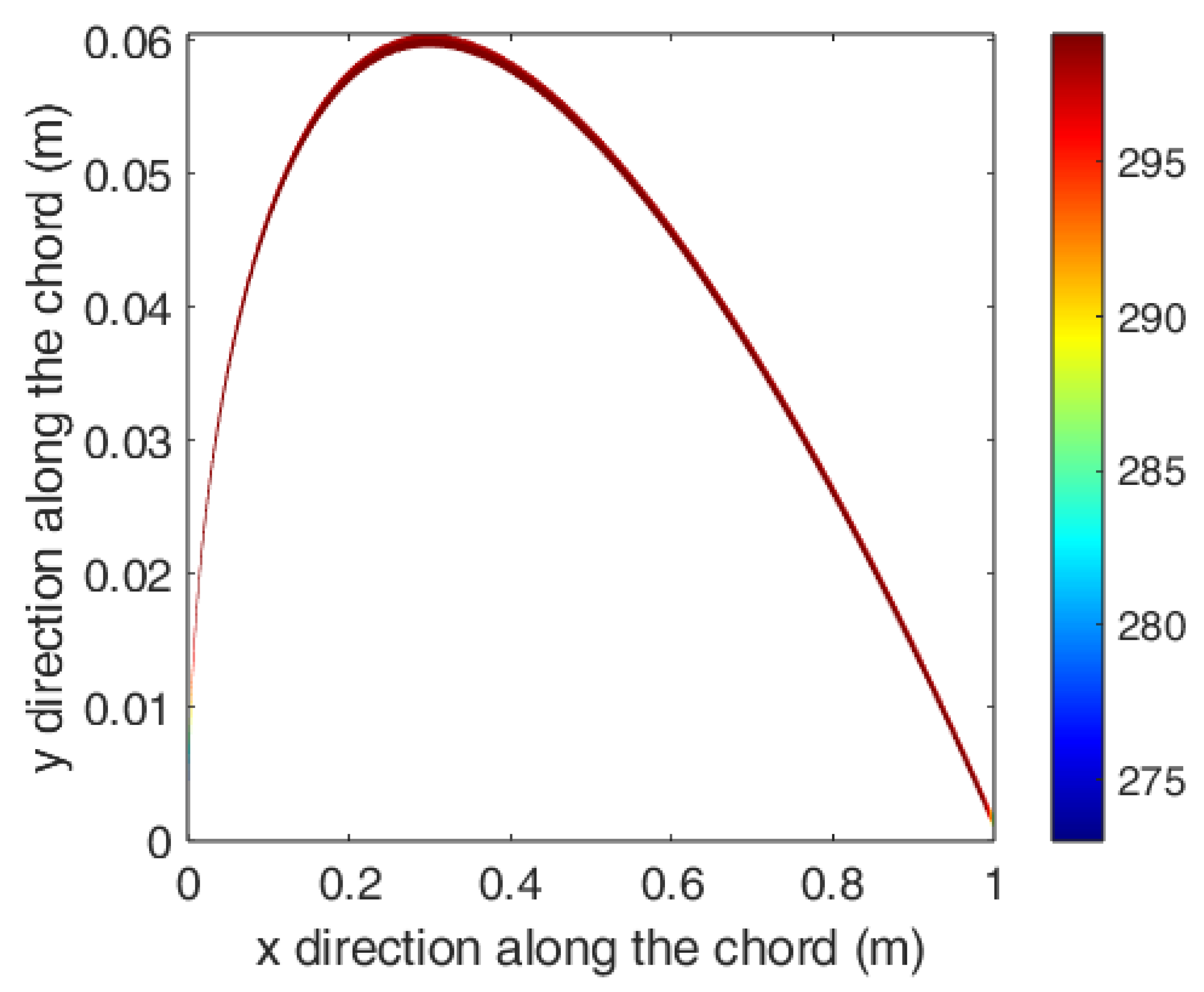

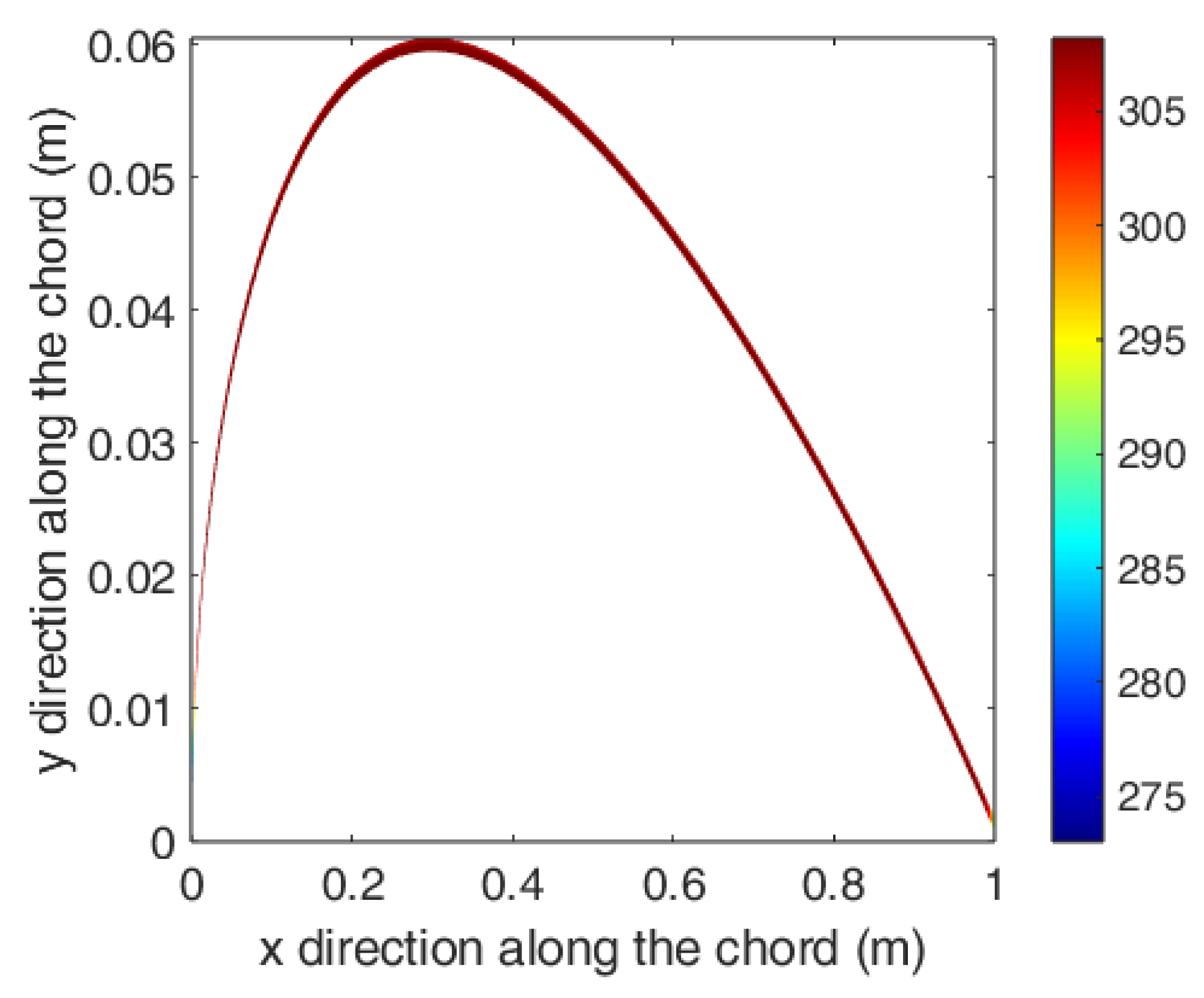

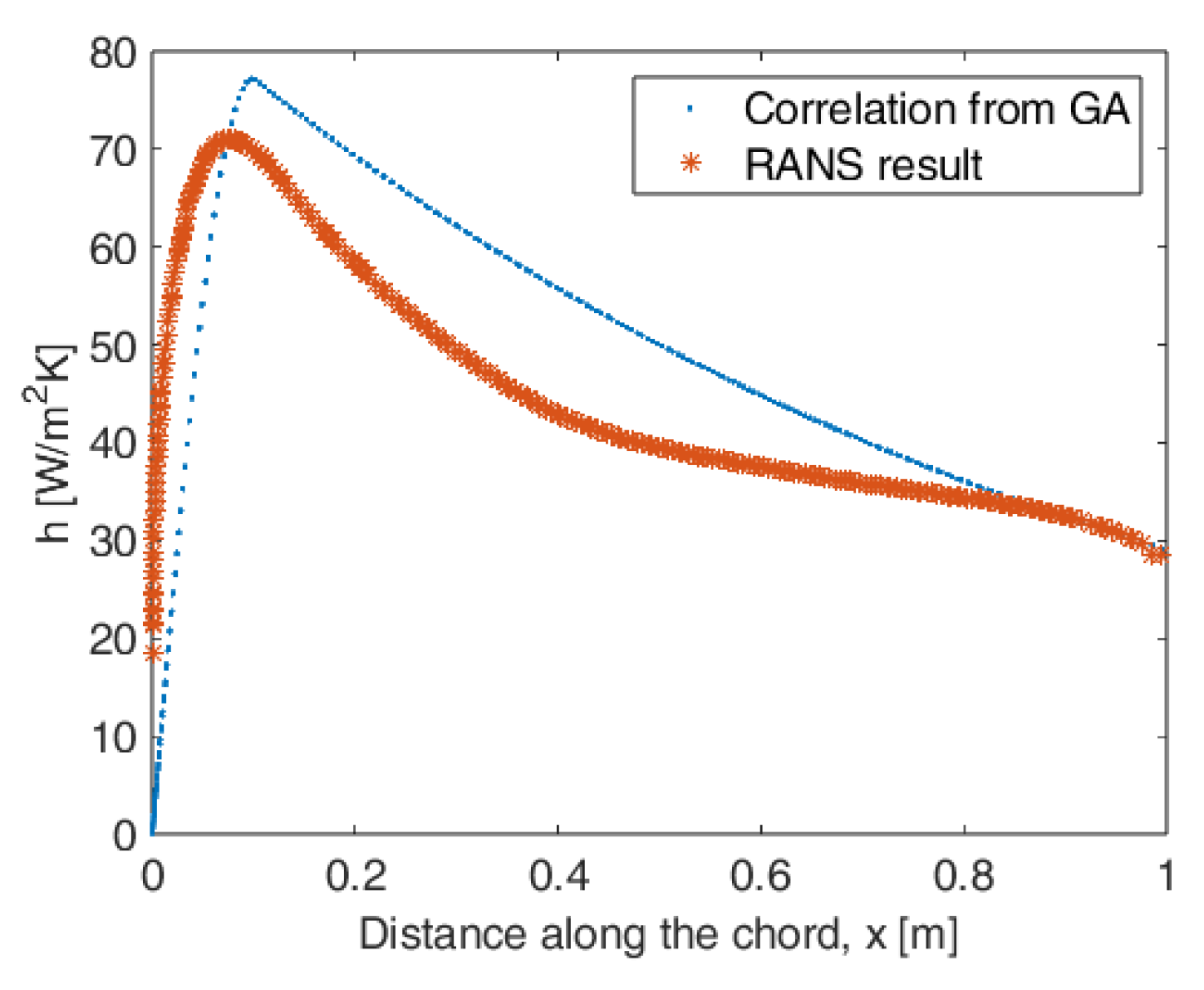

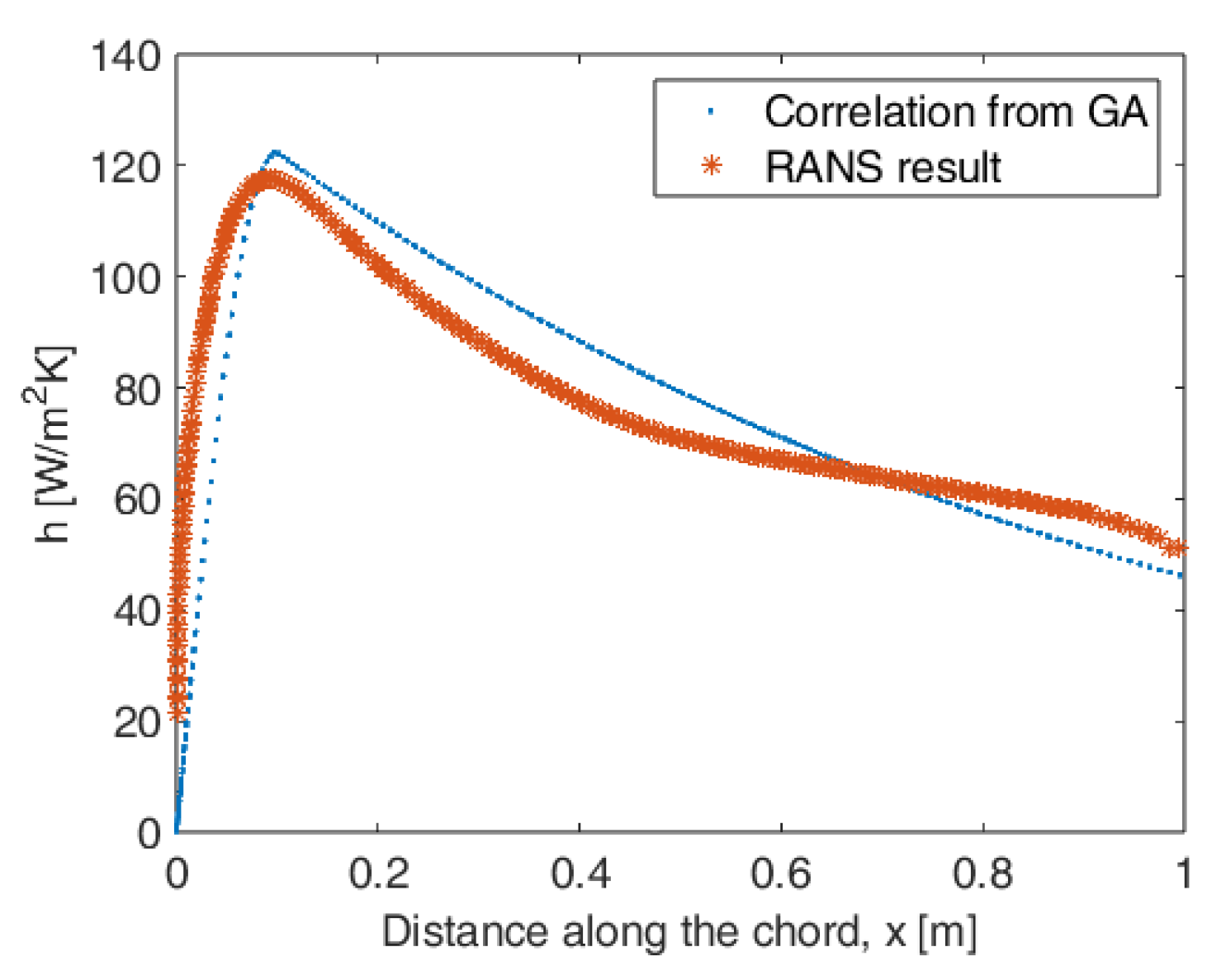

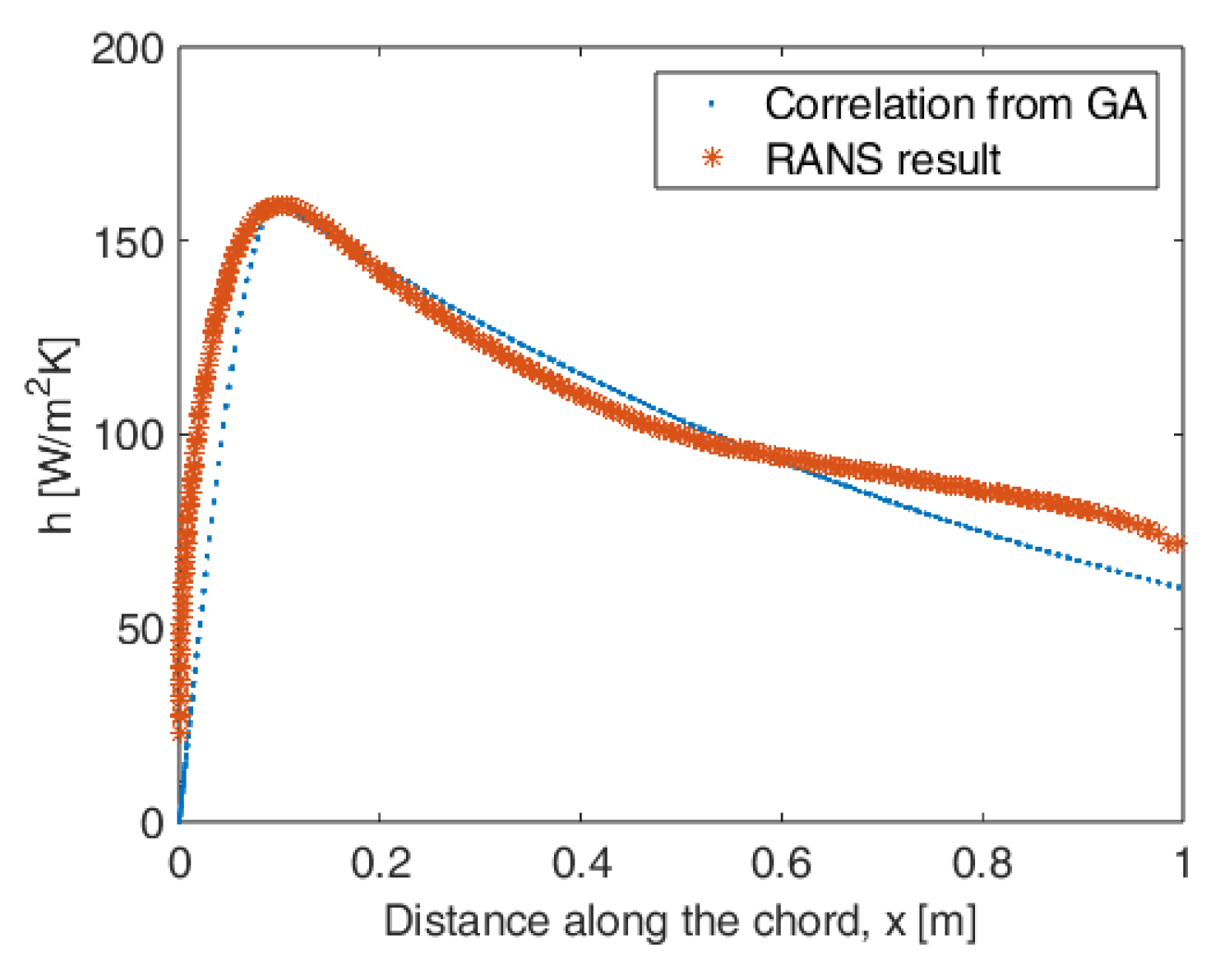

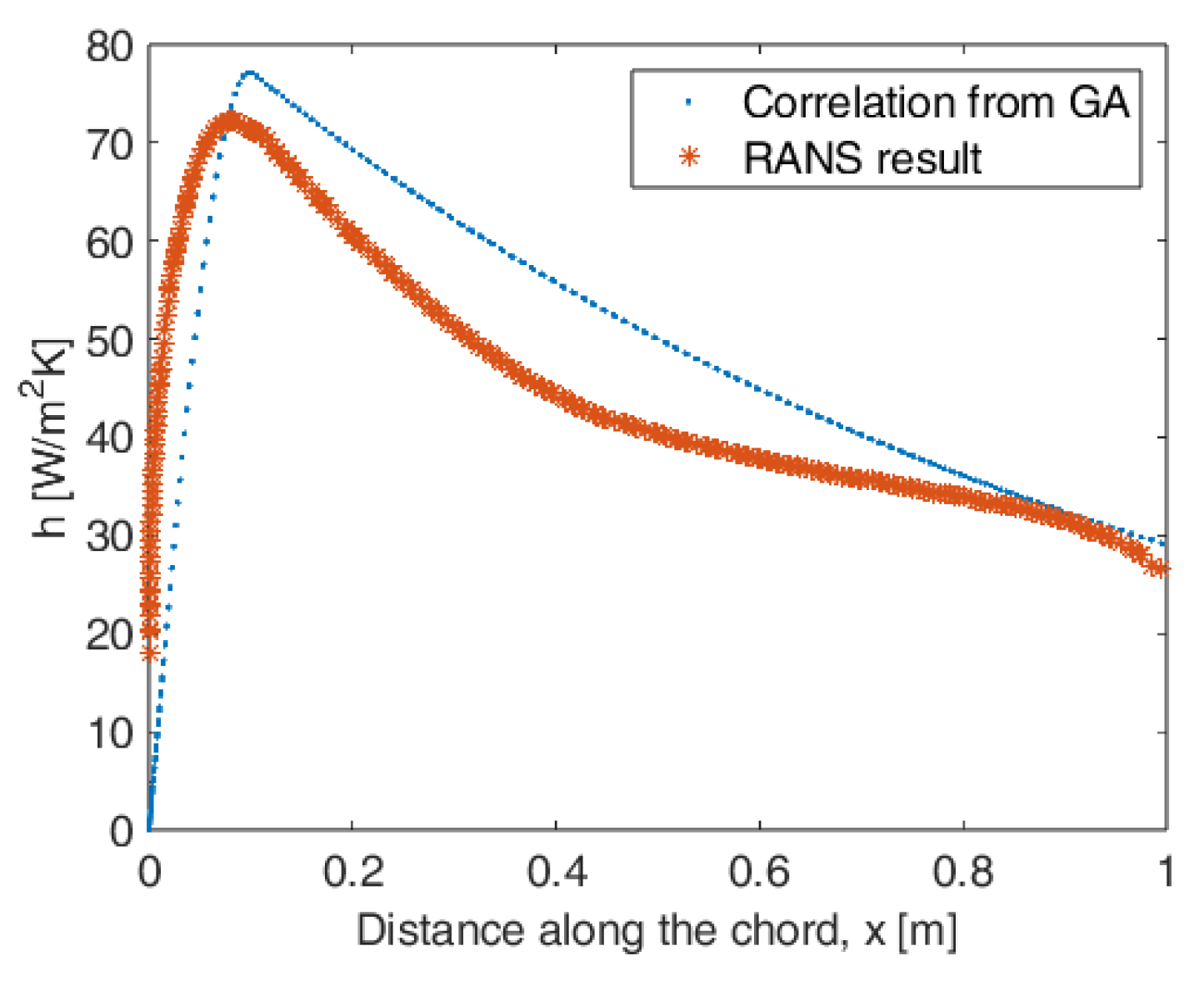

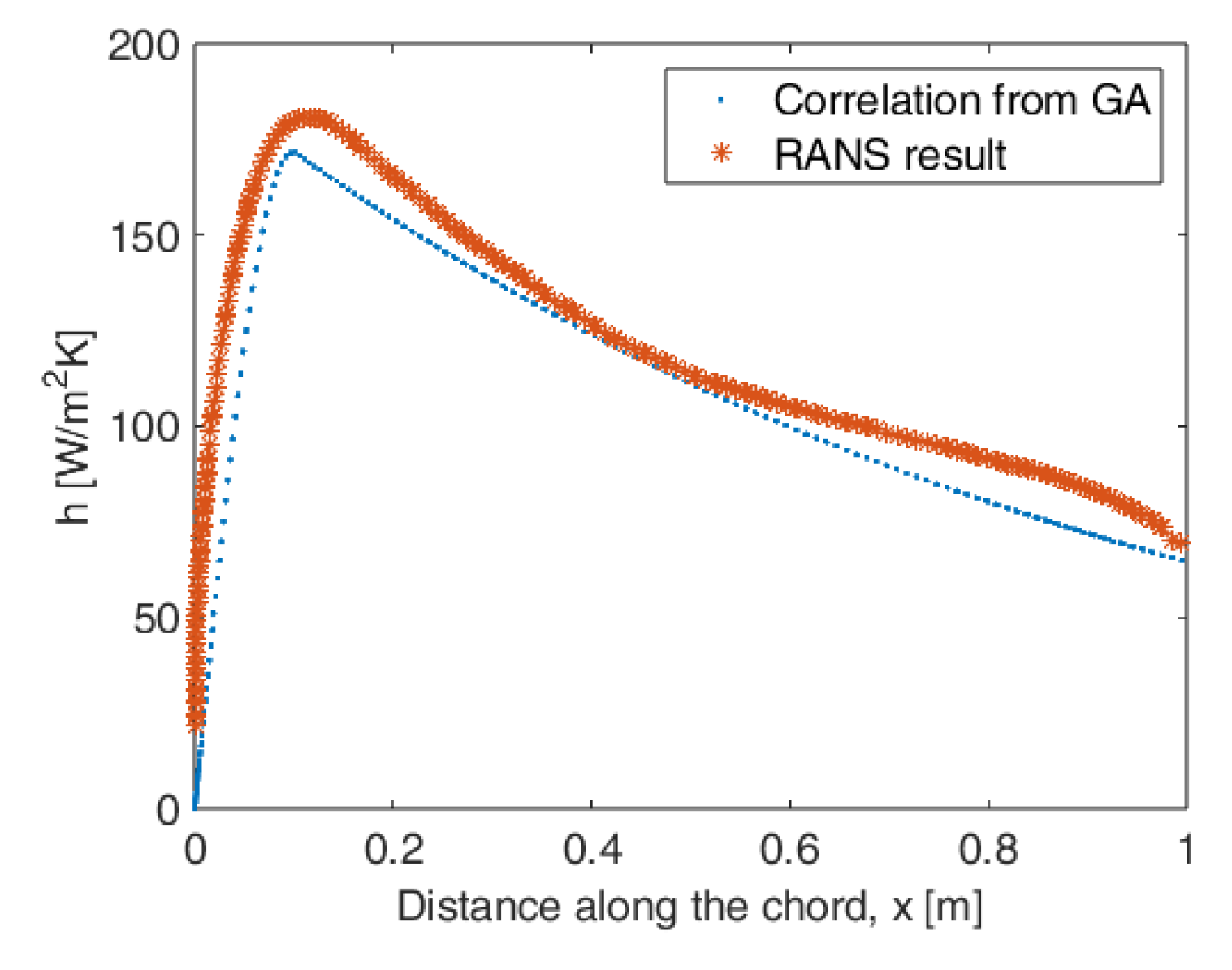

4.1. CFD Analyses over Airfoil for Obtaining Convection Heat Transfer Coefficient

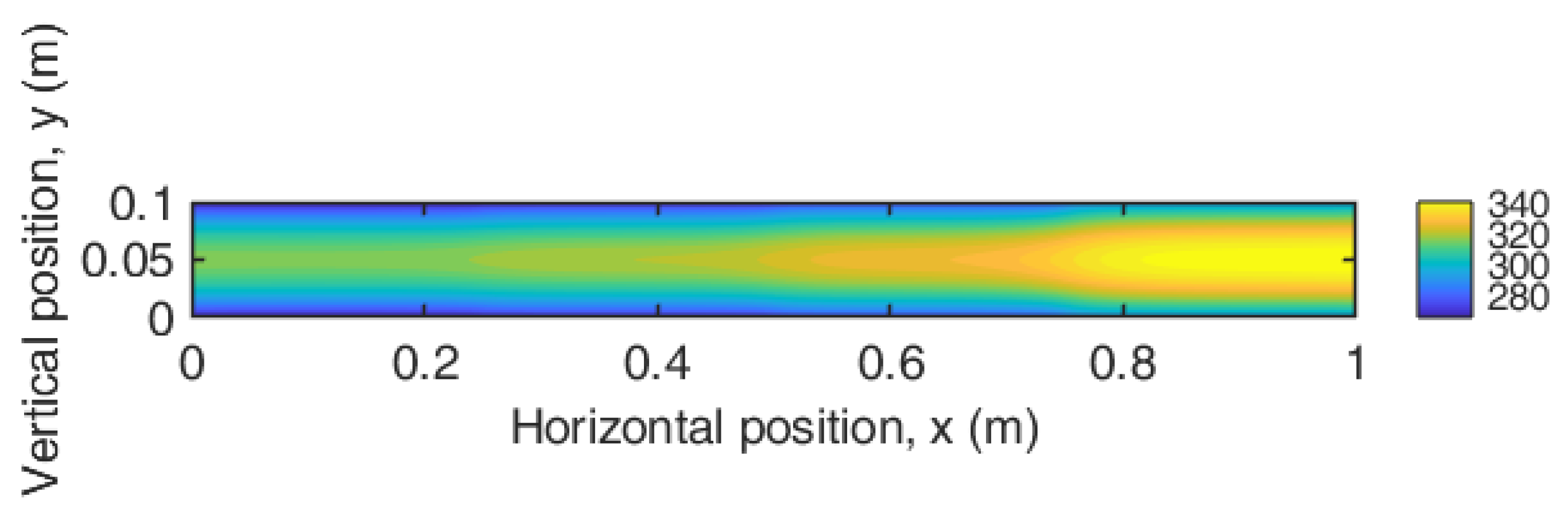

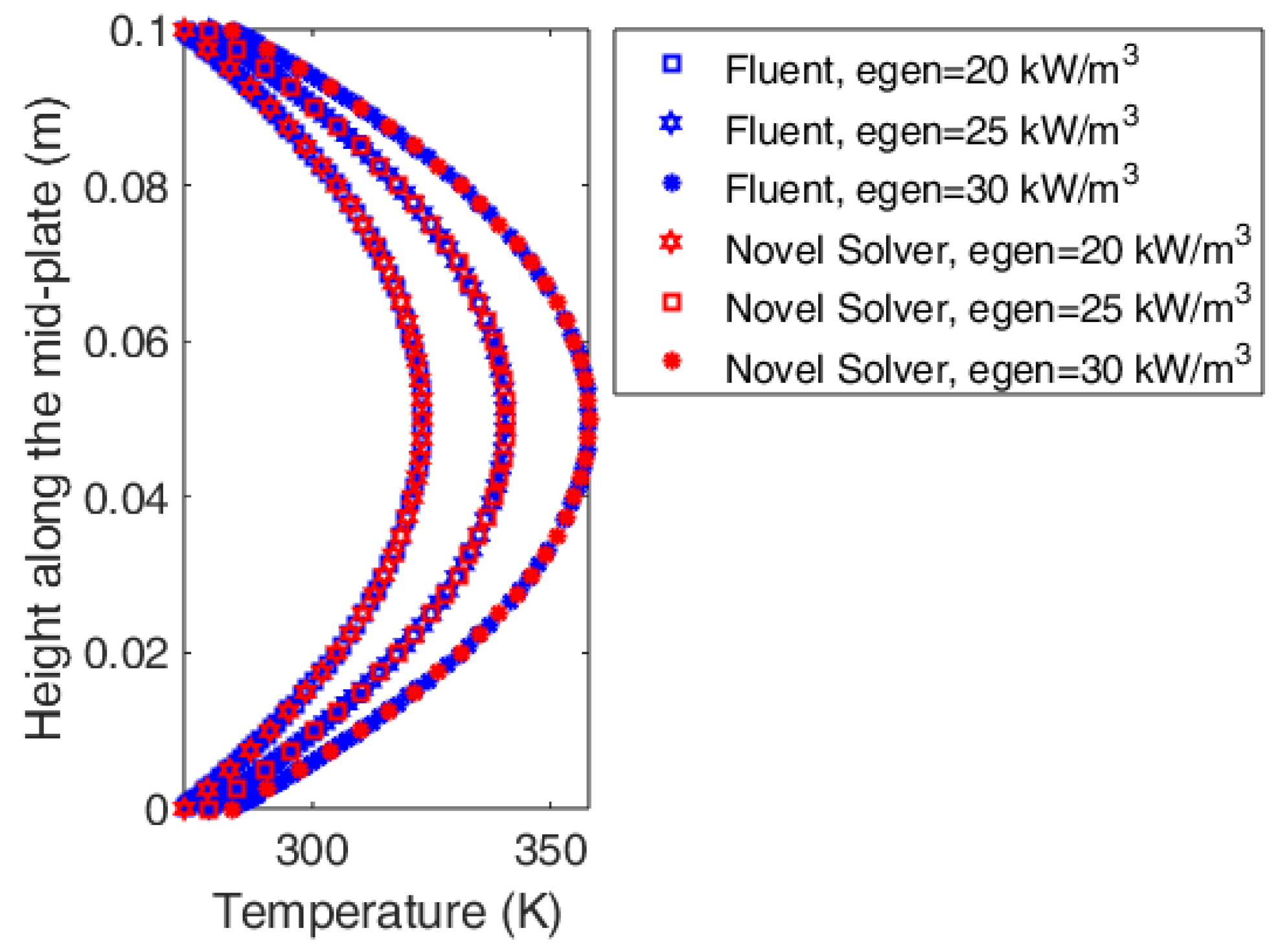

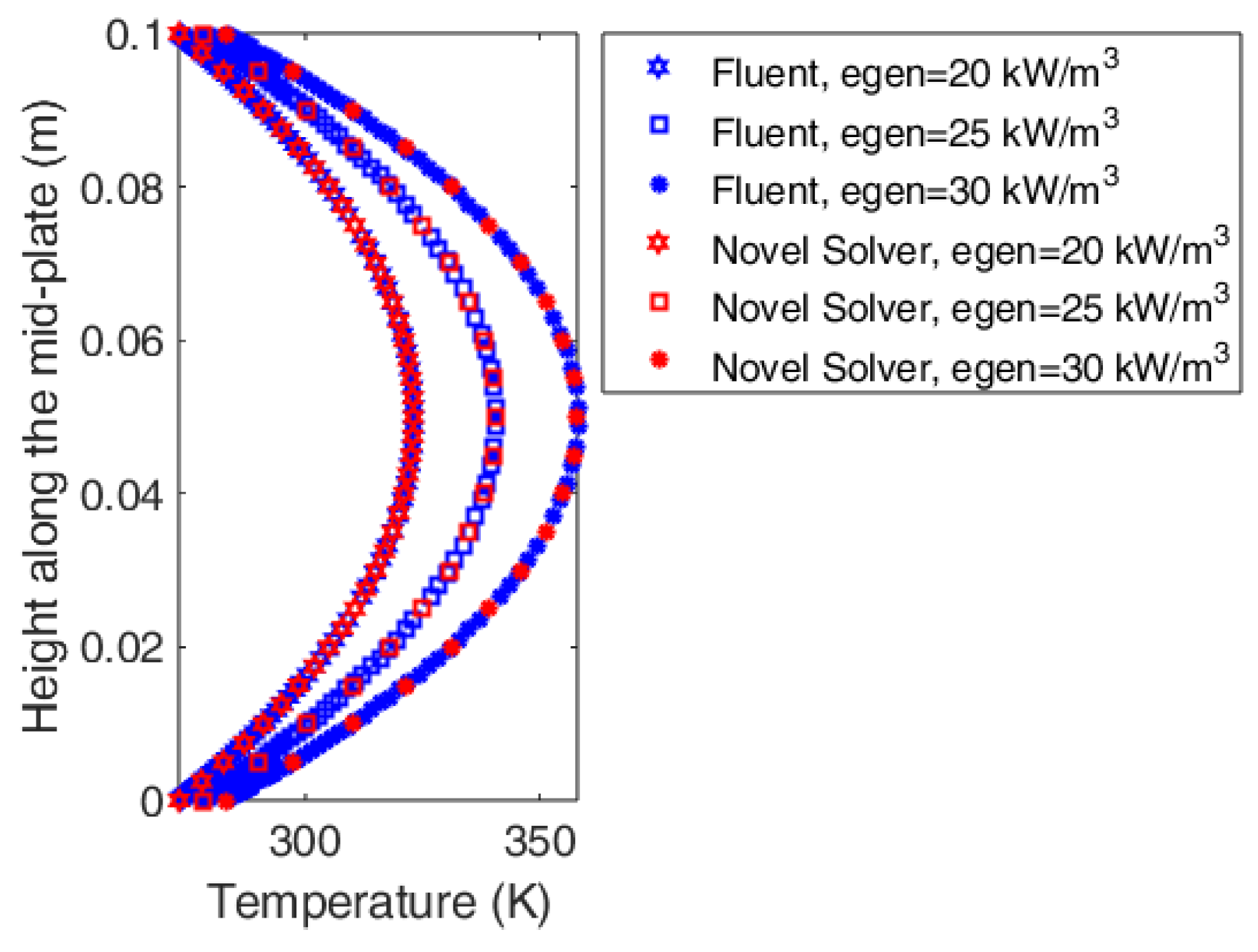

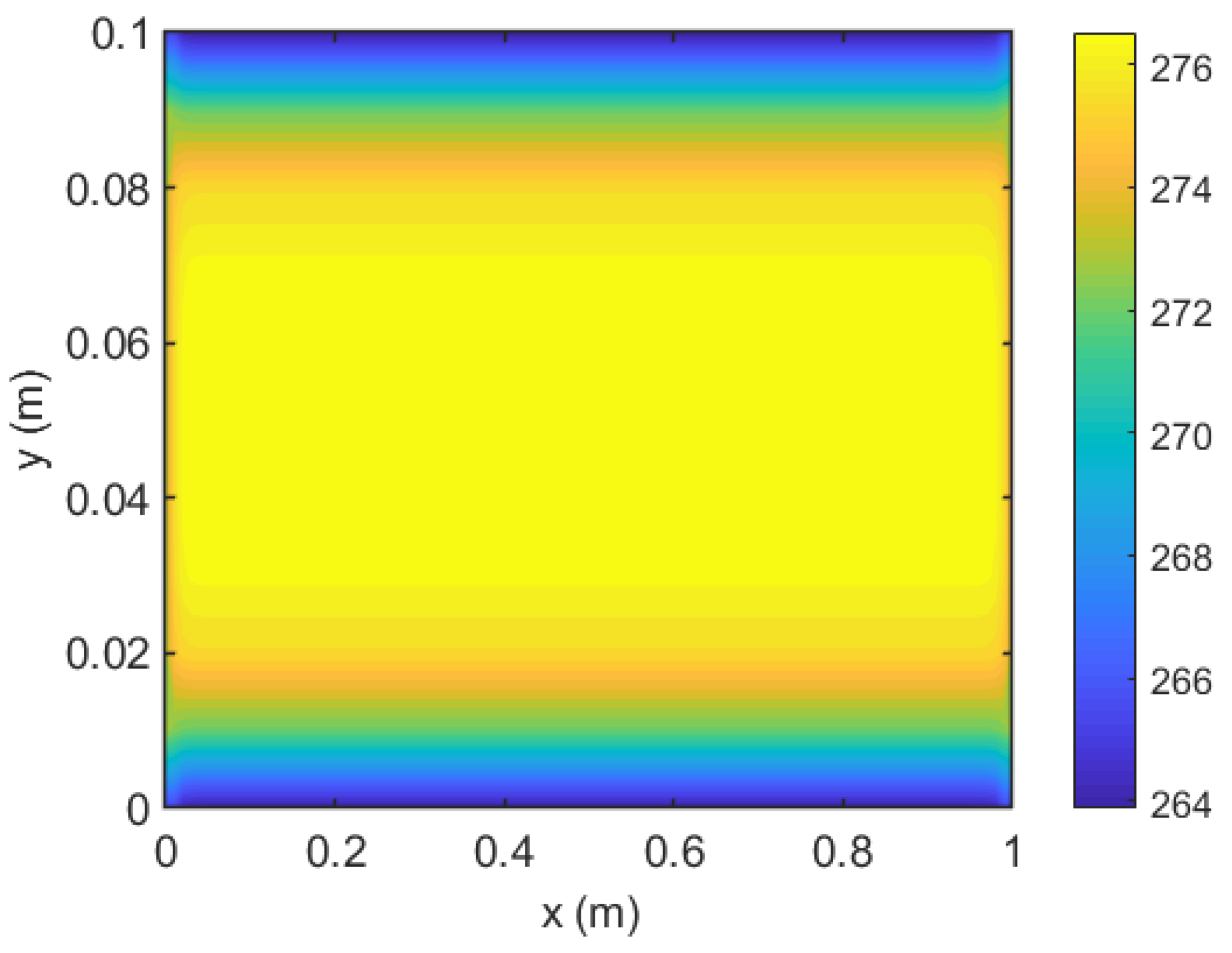

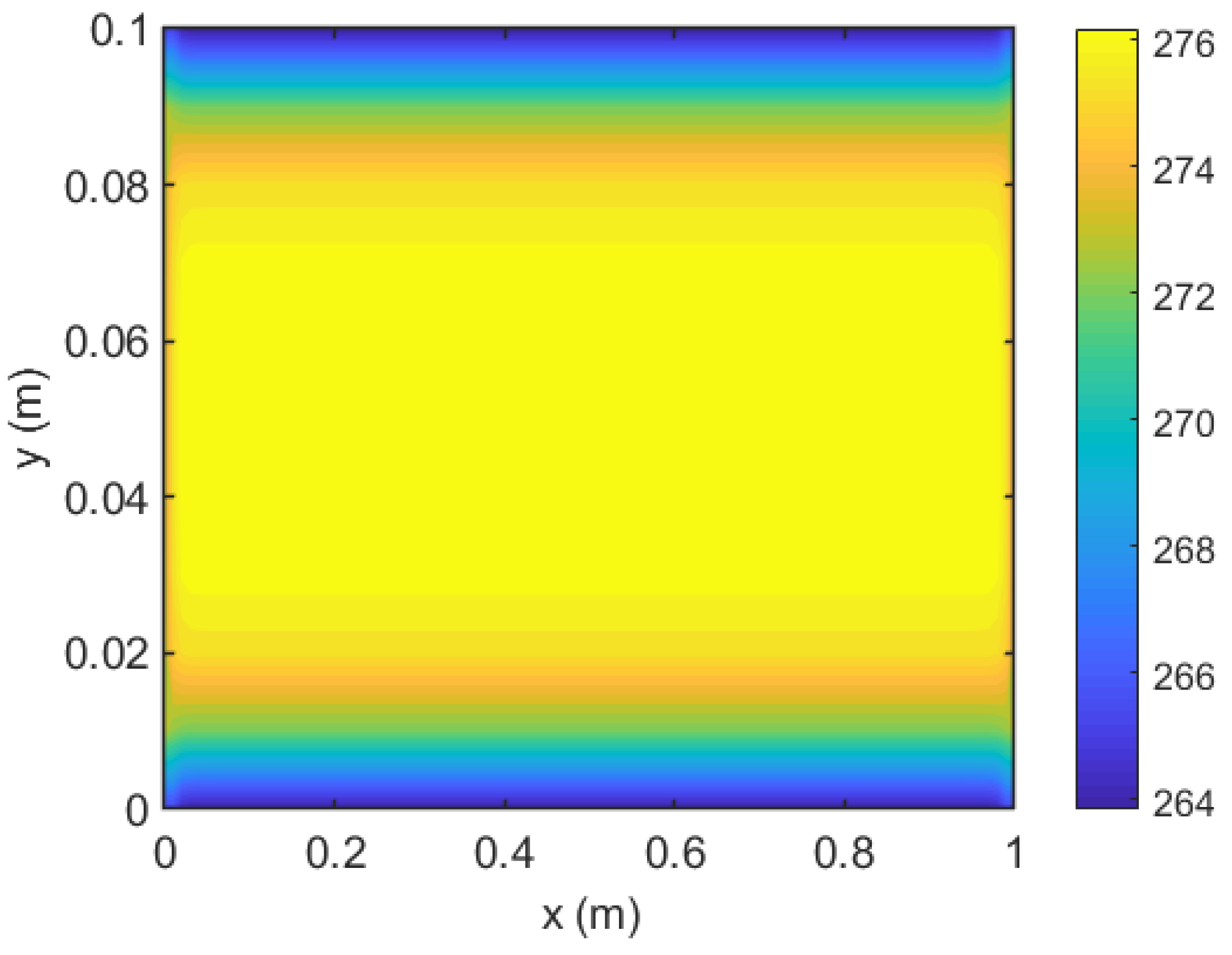

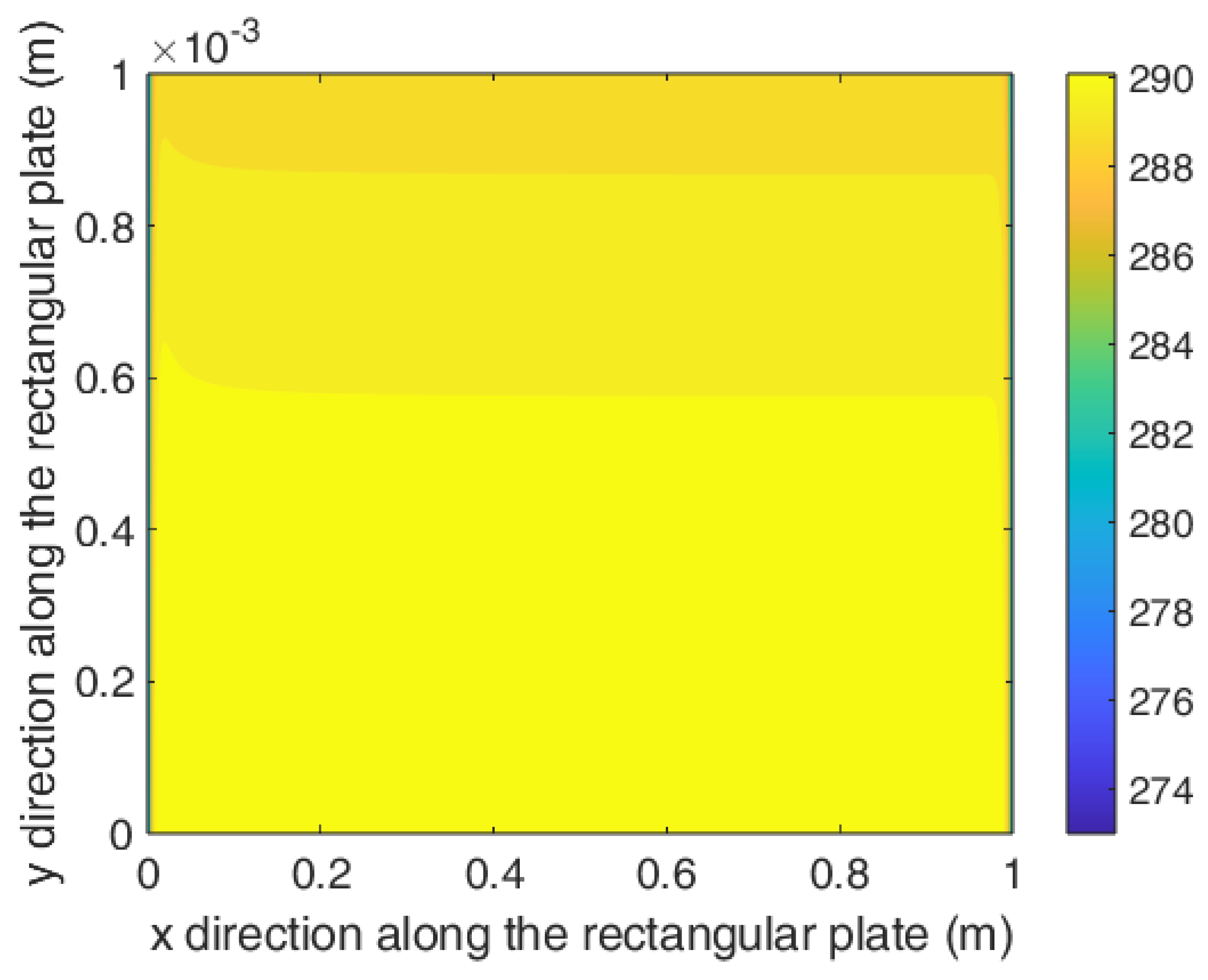

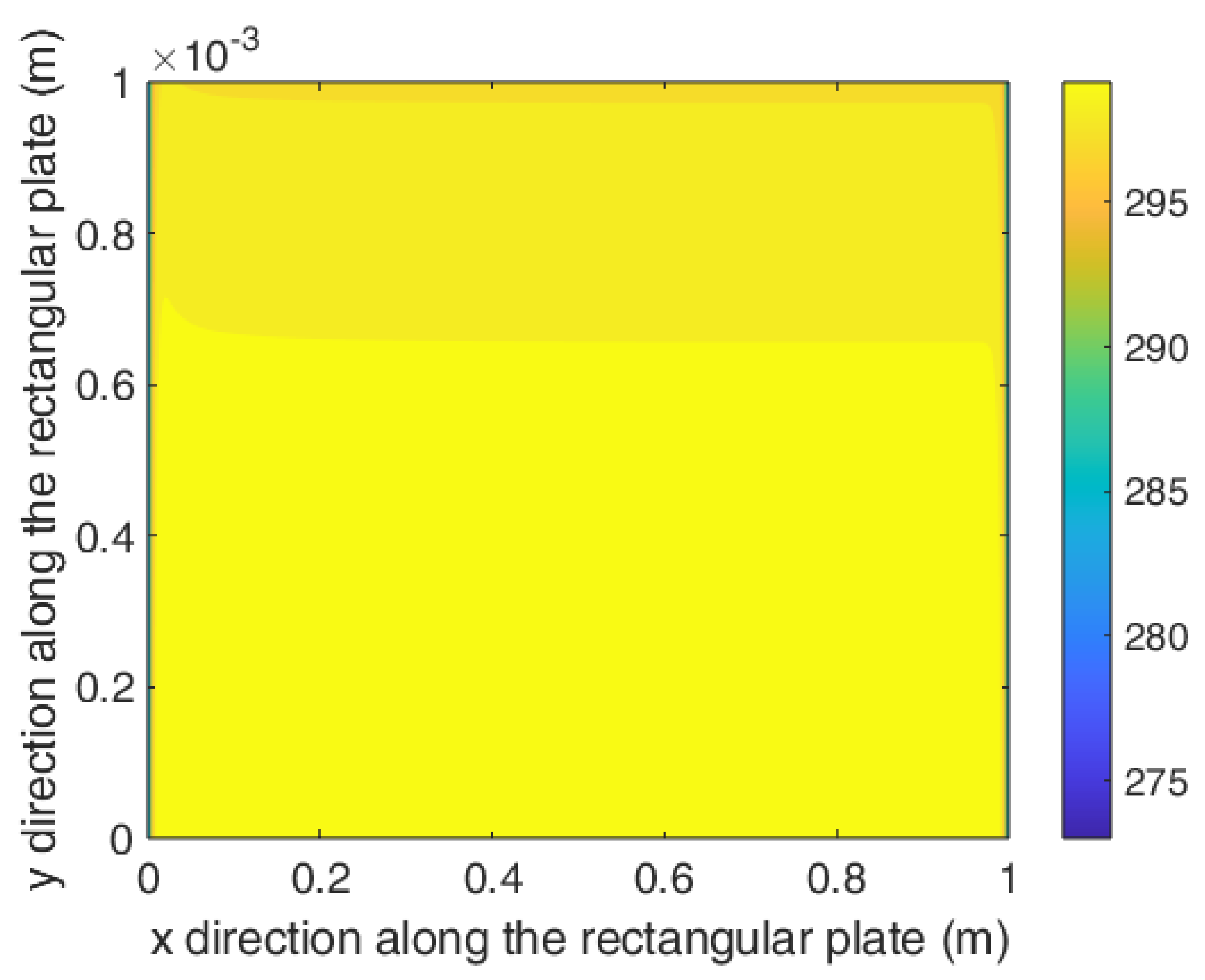

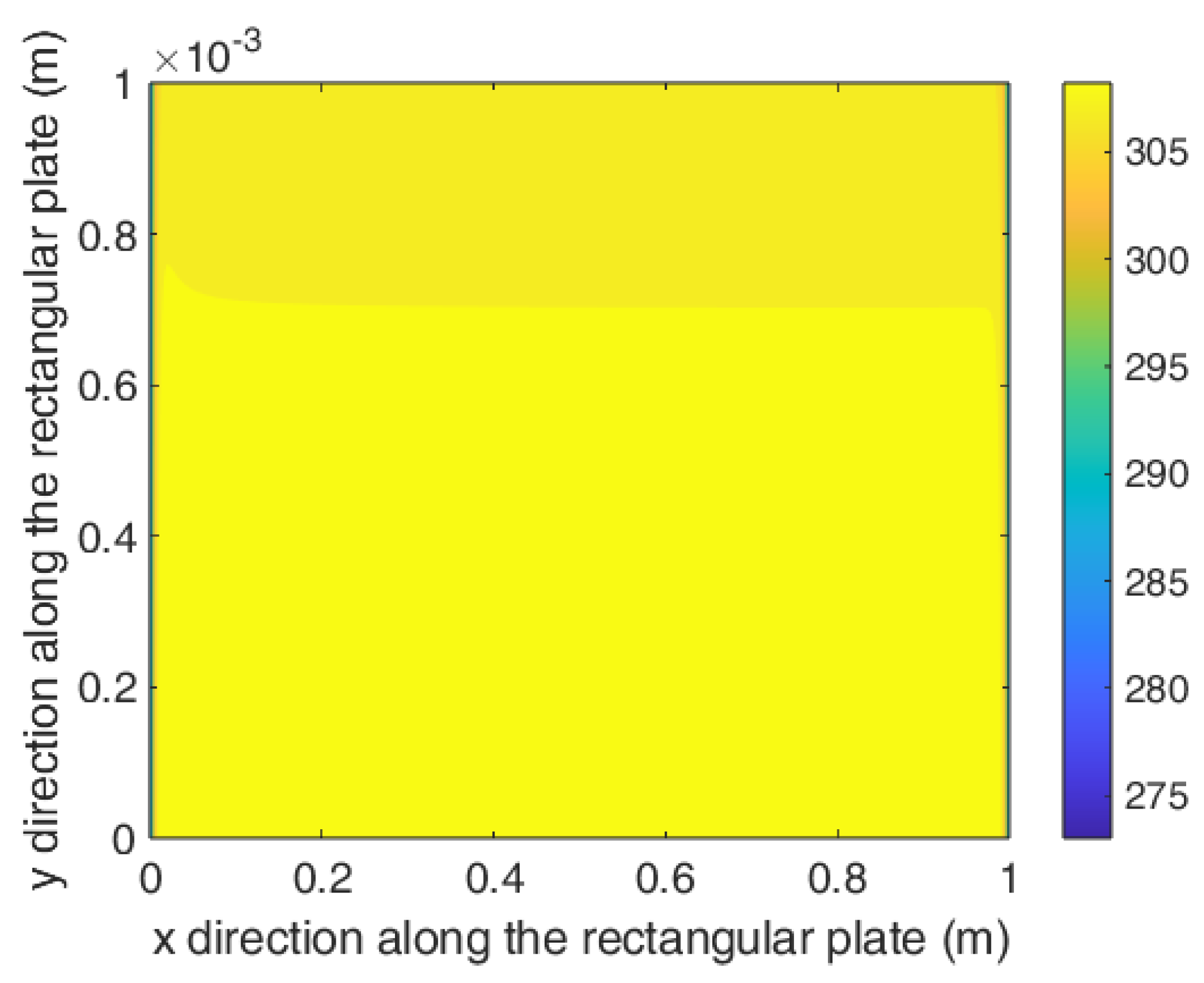

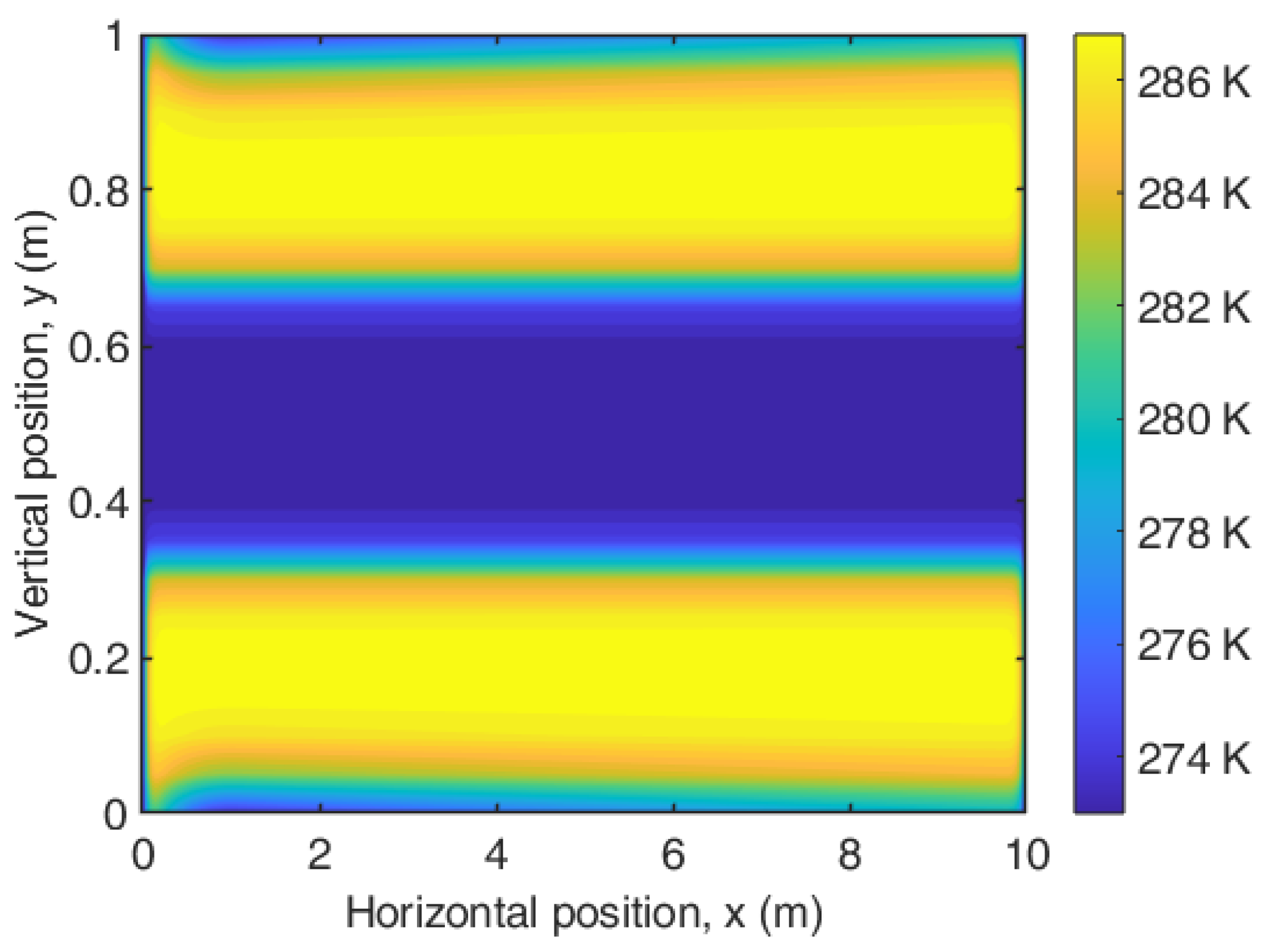

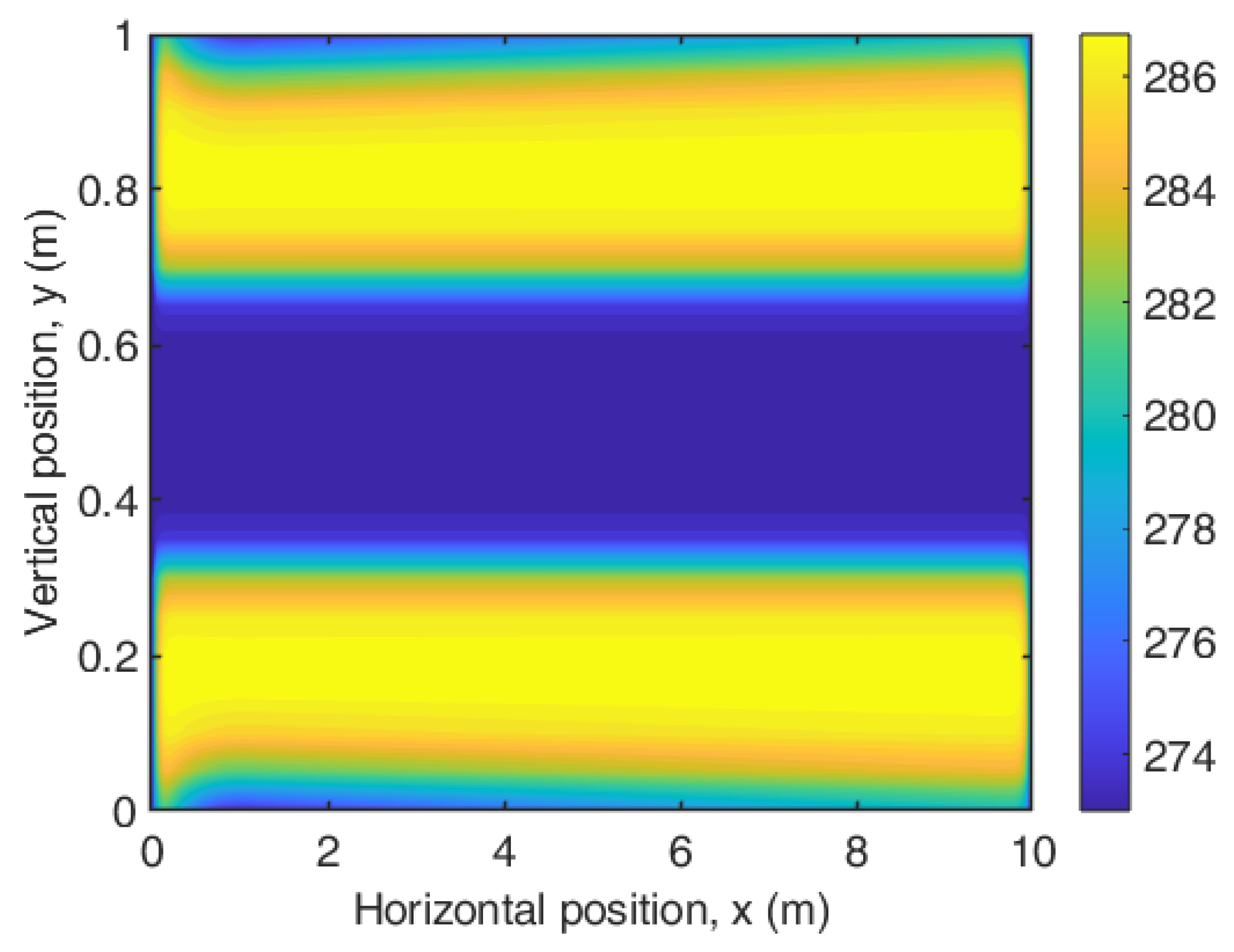

4.2. Plate Thermal Analyses

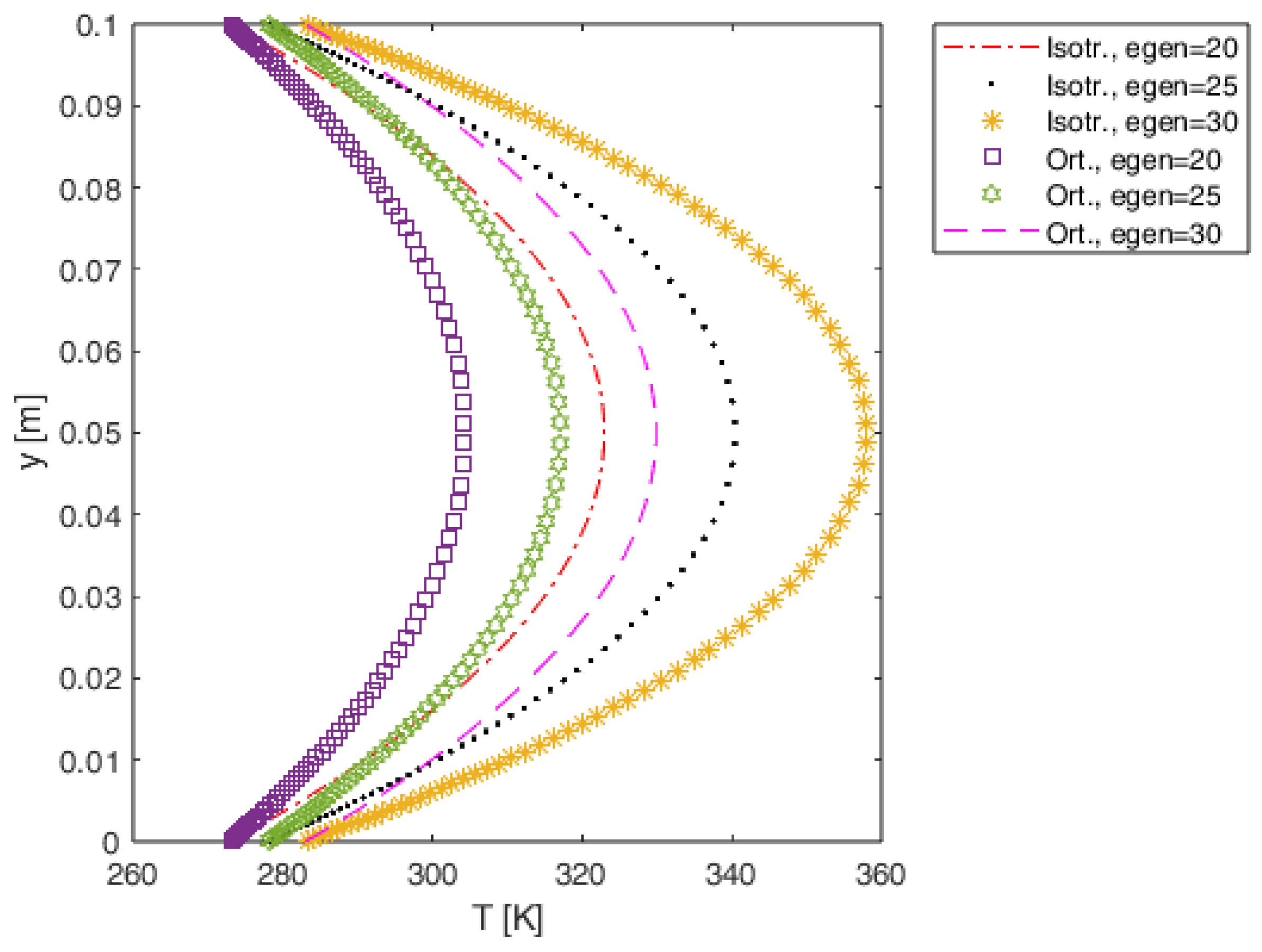

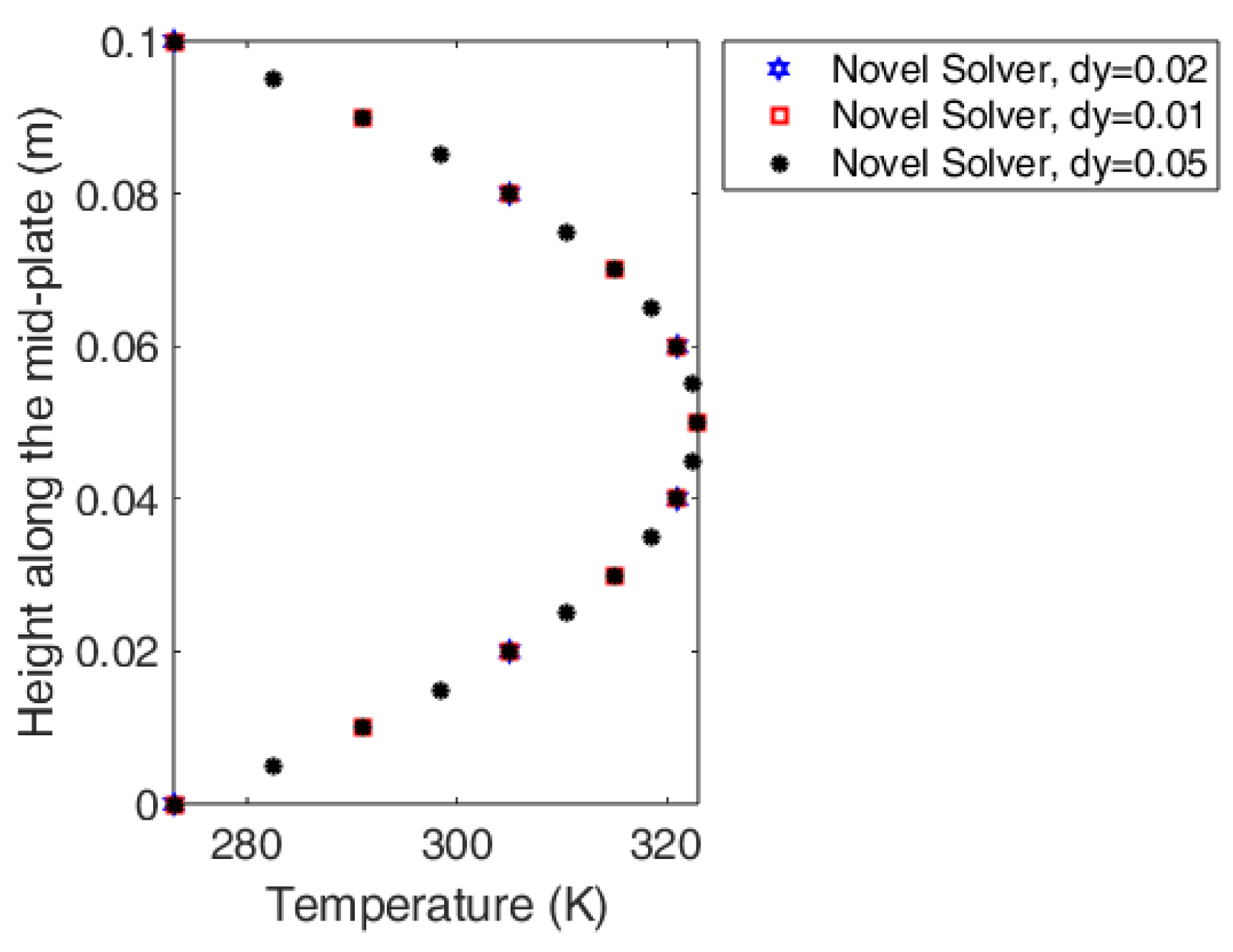

4.3. In-House Solver

5. Optimization Studies

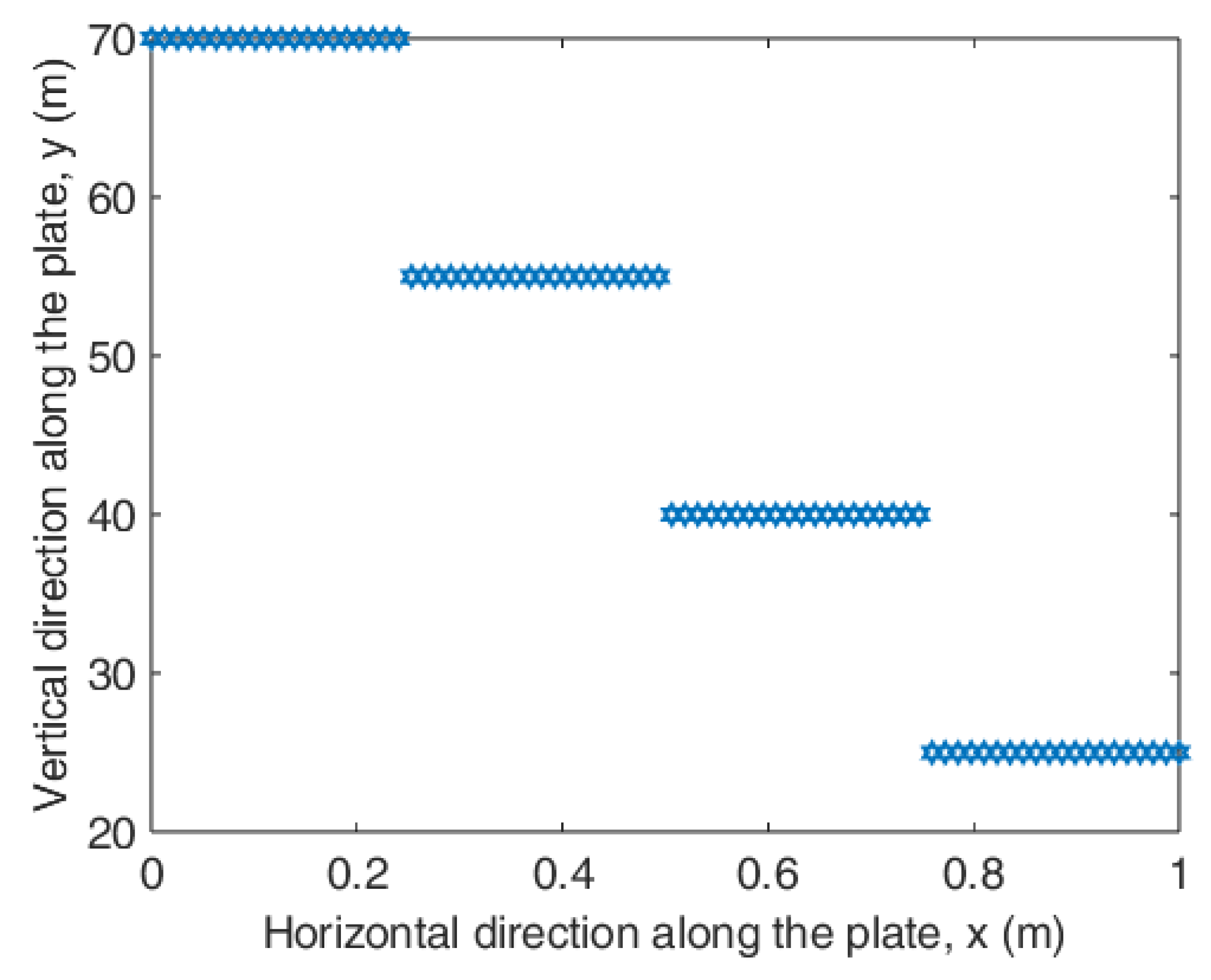

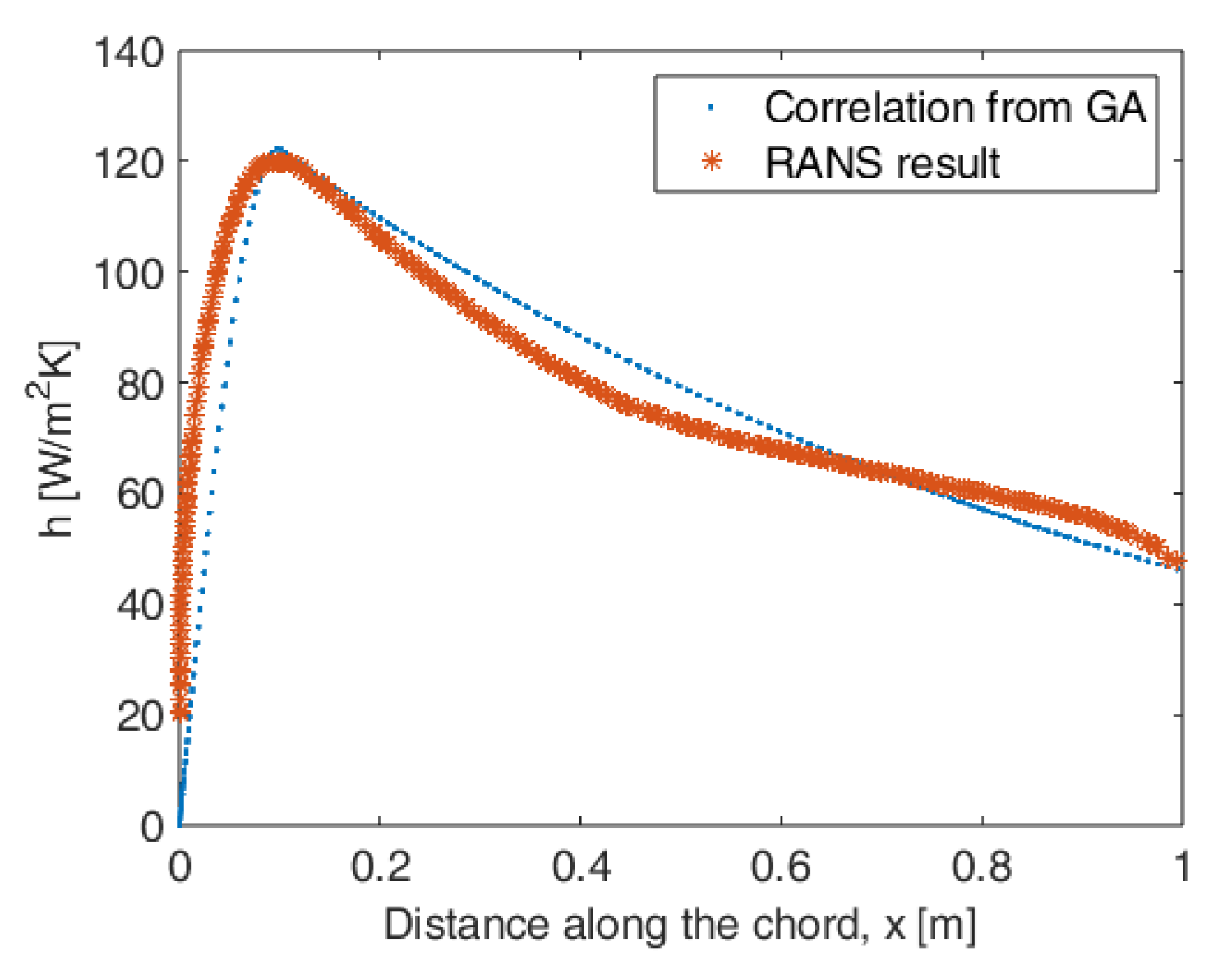

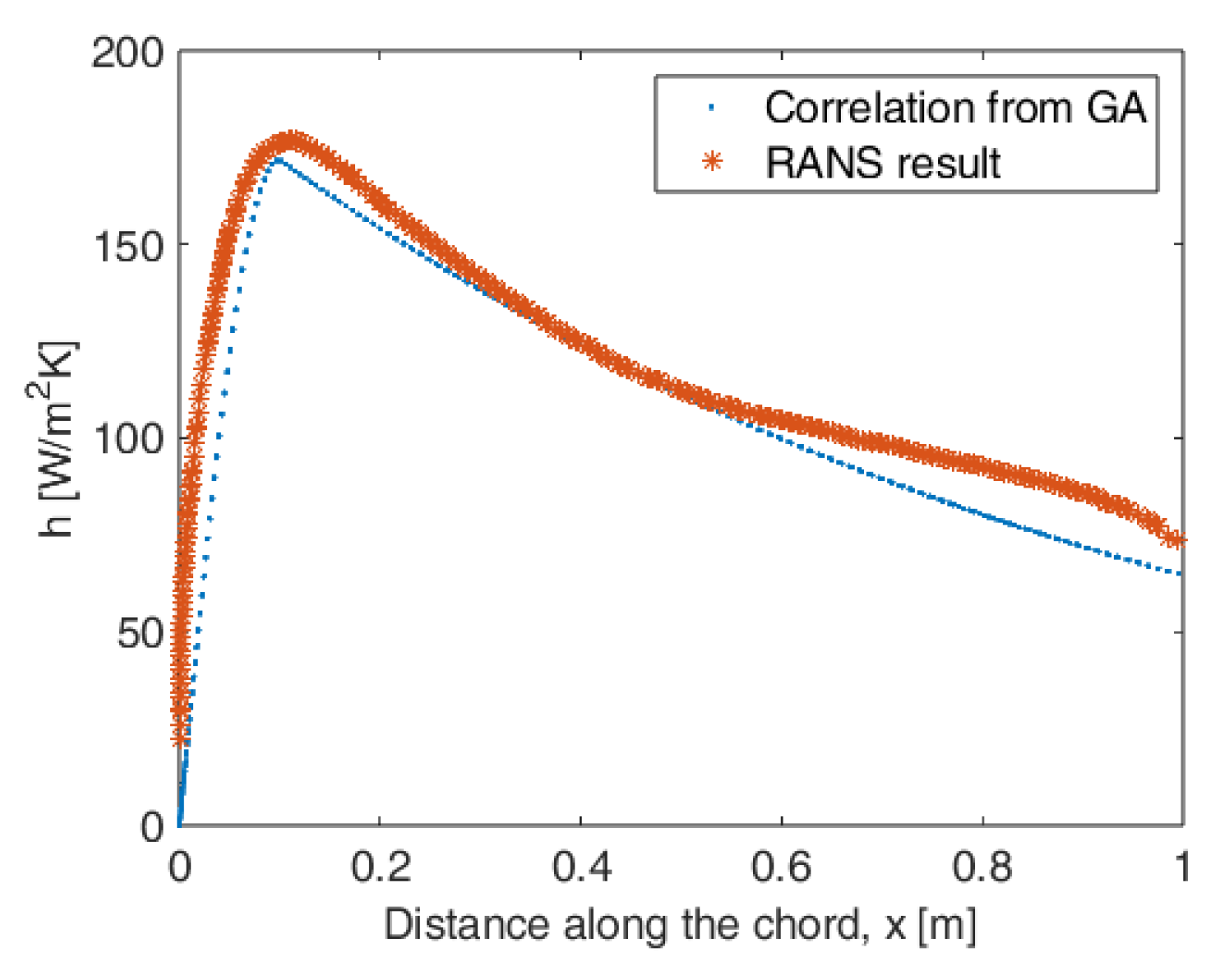

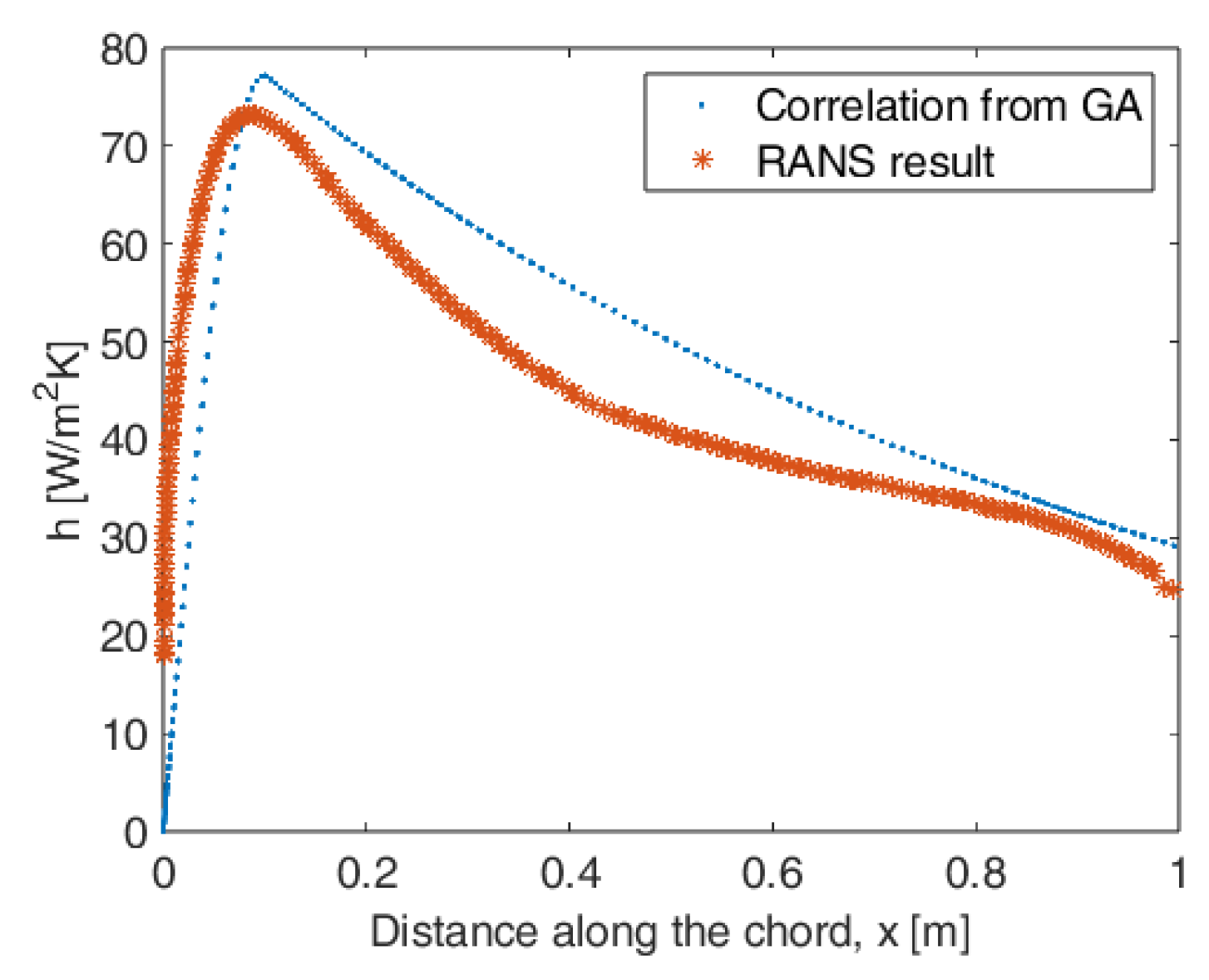

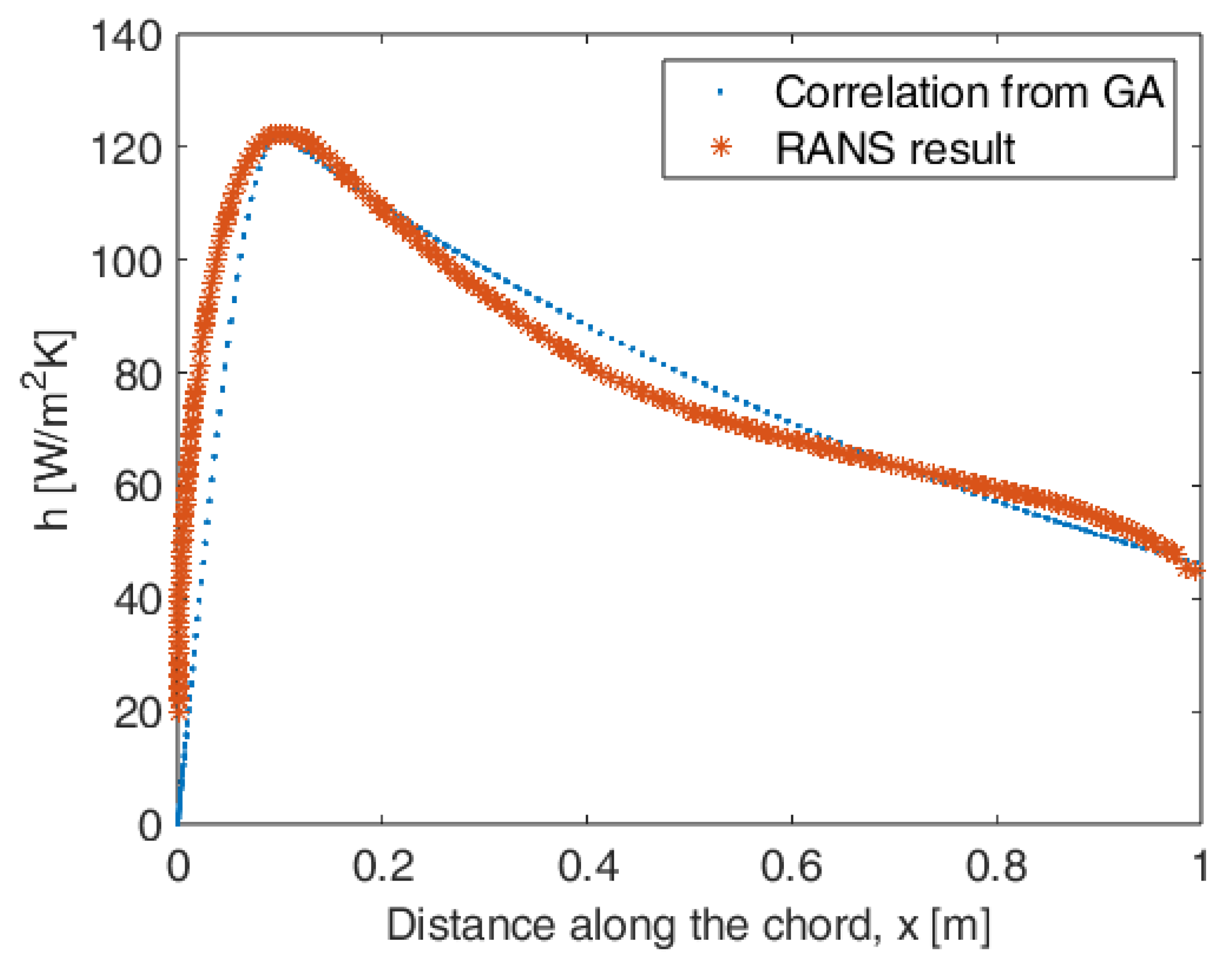

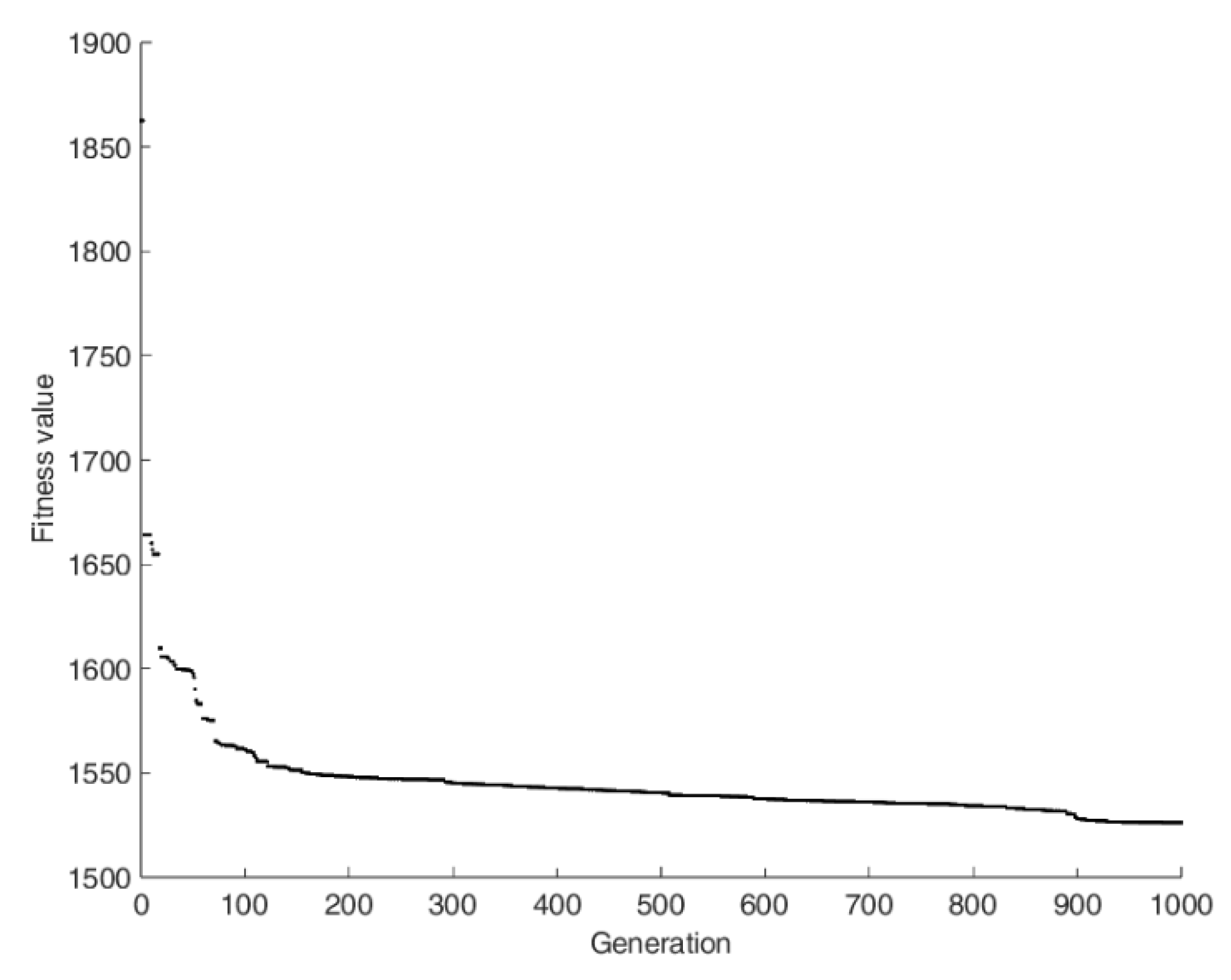

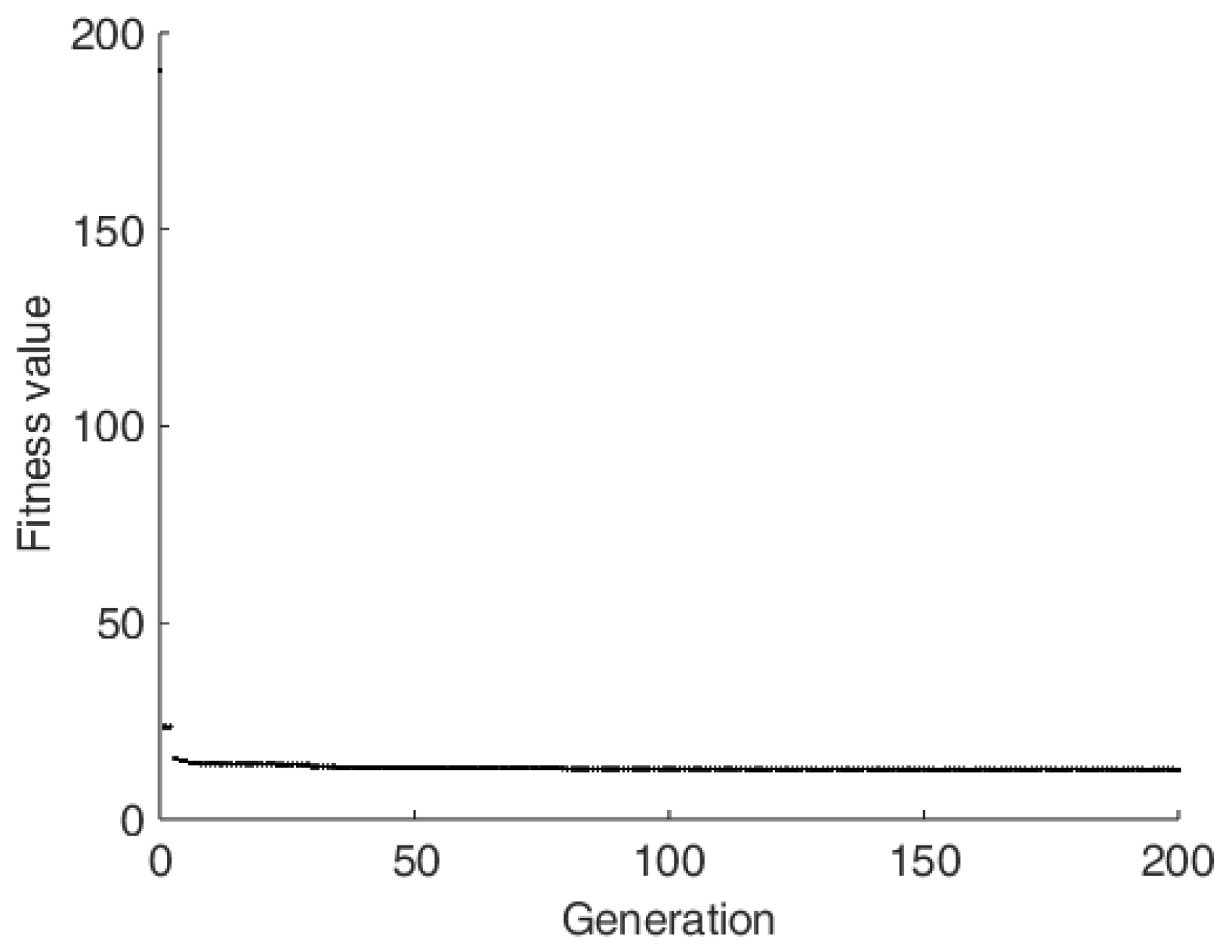

5.1. Optimization for the Correlation Relation for the Convection Heat Transfer Coefficient

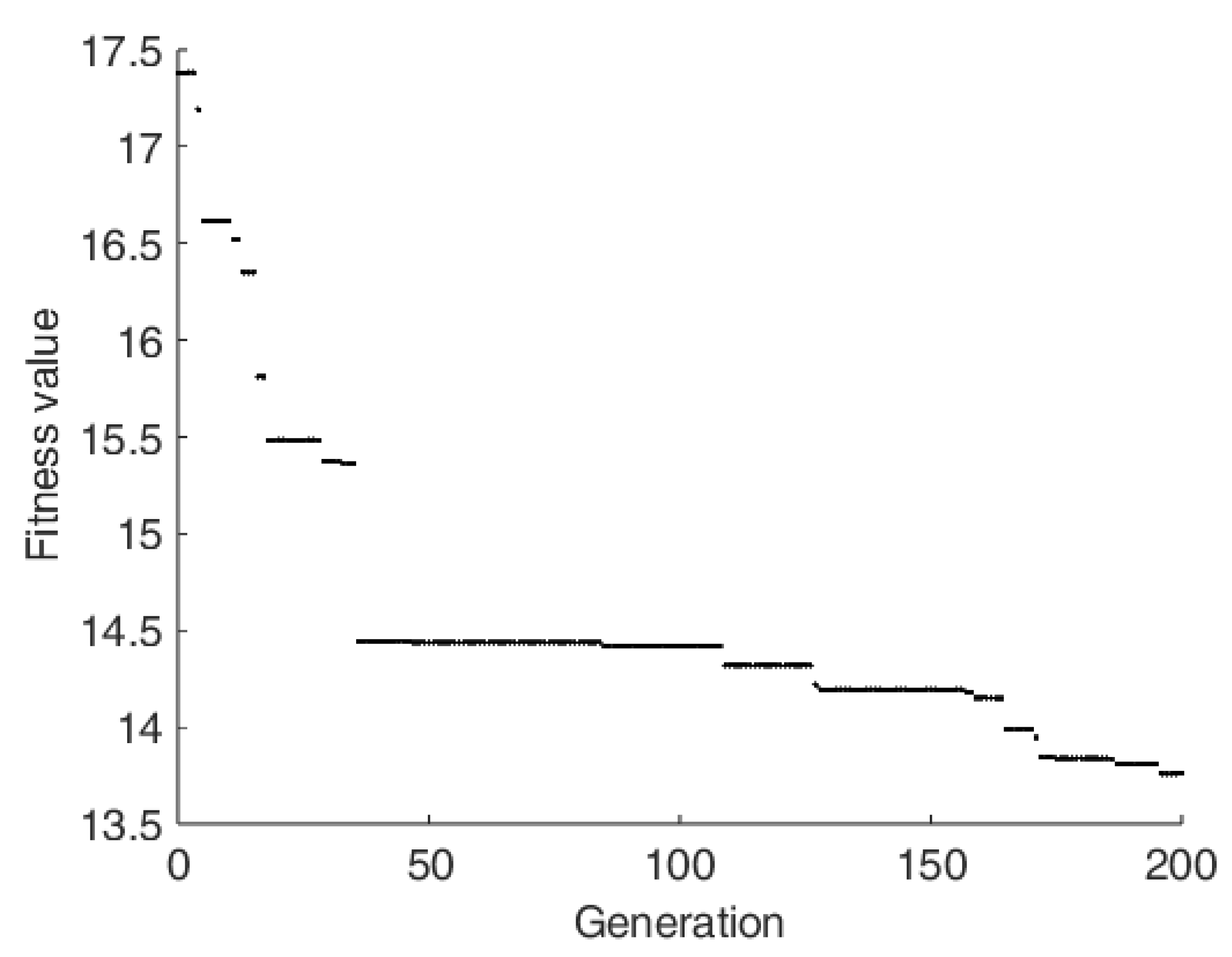

5.2. Optimization for the Heater Geometry and Power Input

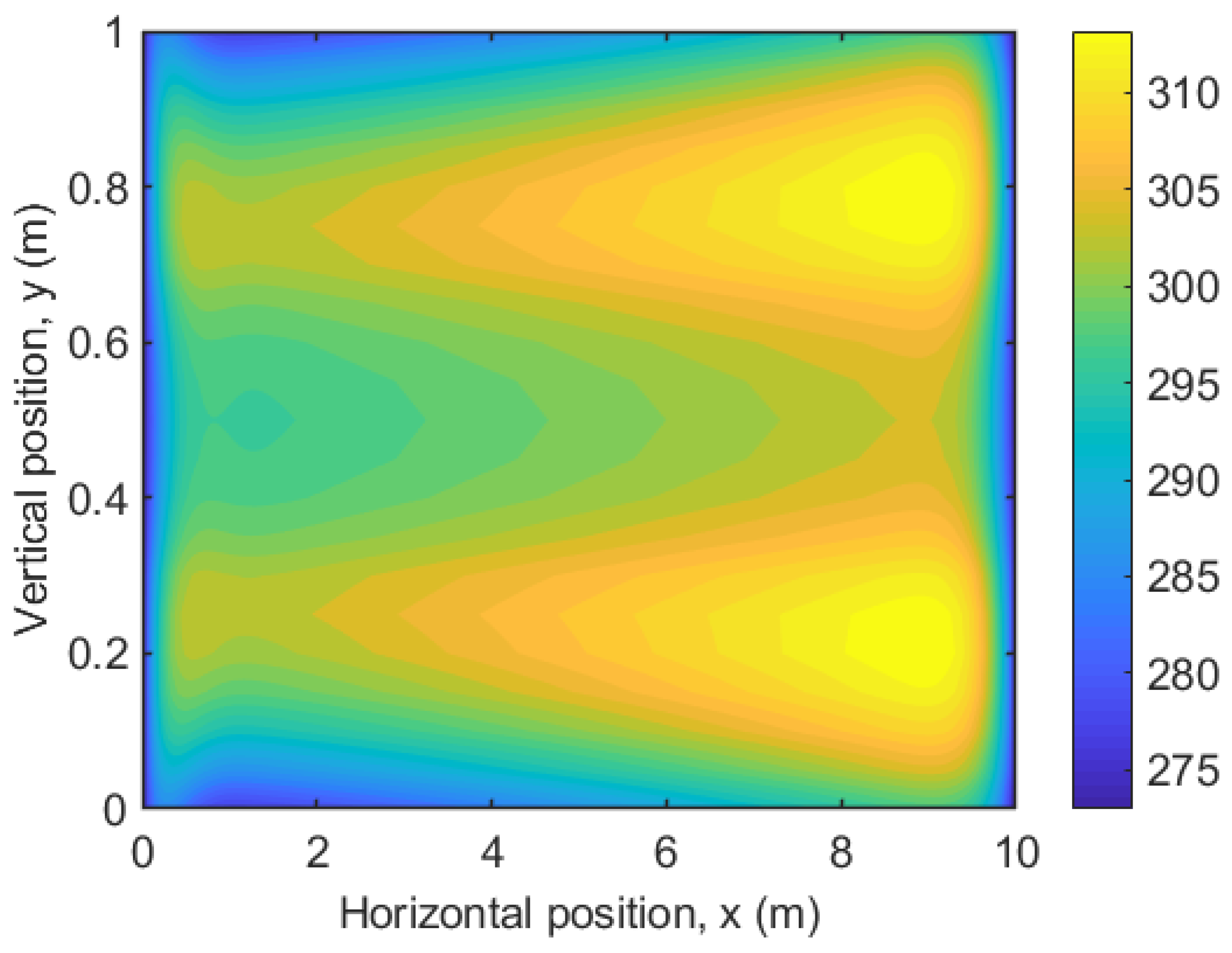

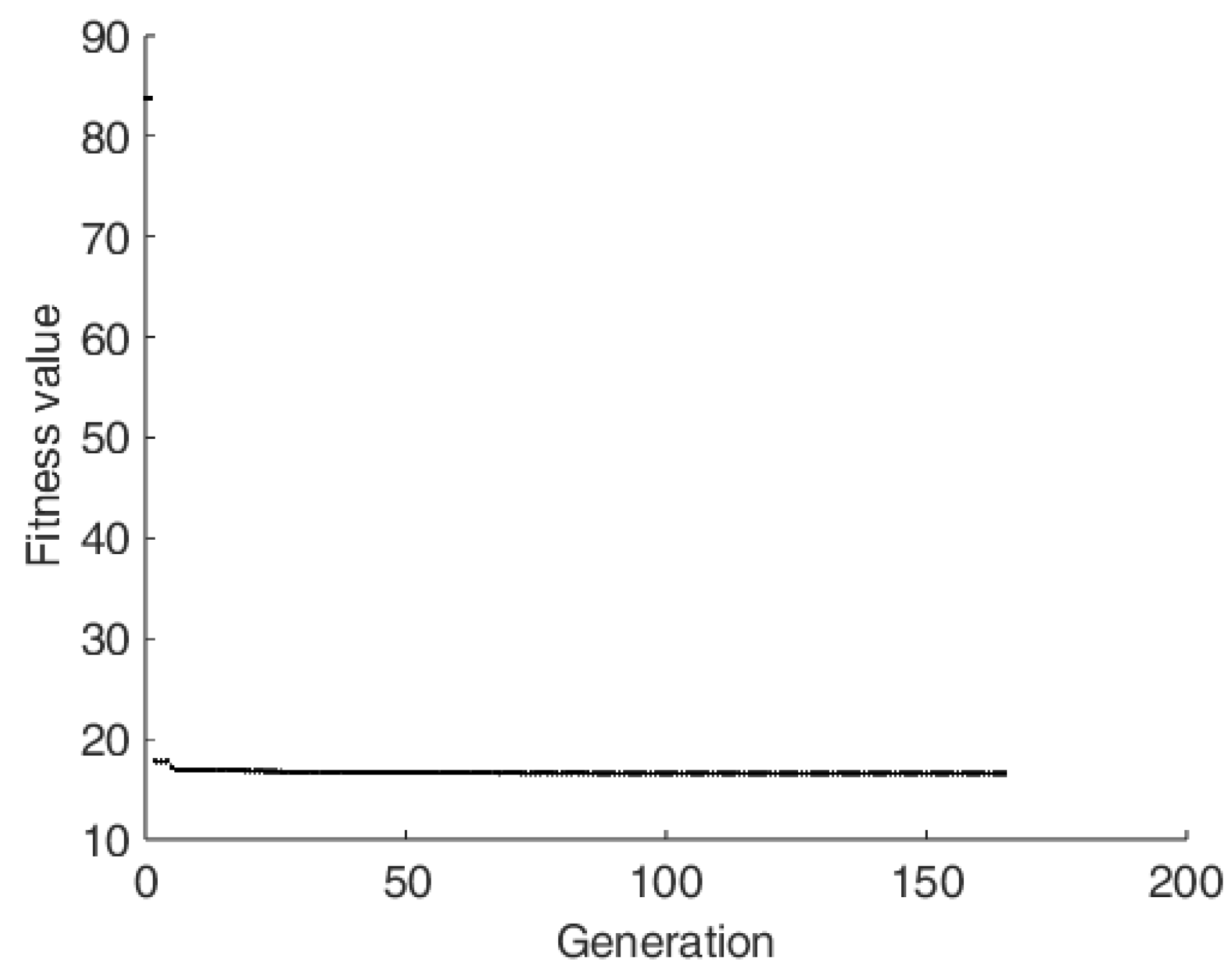

5.3. Optimization for the Heater Geometry, Power Input and Ply Angles

5.4. Optimization for the Heater Geometry, Power Input and Varying Ply Angles for an Anti-Icing System

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gent, R.W.; Dart, N.P.; Cansdale, J.T. Aircraft Icing. Philosophical Transactions: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2000, 358, 2873–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.G. Extension to the Messinger Model for Aircraft Icing. AIAA Journal 2001, 39, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutzeichel, M.O.H. Multiphysical and multi scale modelling of composite materials for aircraft De-Icing. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S.K.; Bae, S.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, J.B.; Hong, B.H. High-performance graphene-based transparent flexible heaters. Nano Lett 2011, 11, 5154–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volman, V.; Zhu, Y.; Raji, A.R.; Genorio, B.; Lu, W.; Xiang, C.; Kittrell, C.; Tour, J.M. Radio-frequency-transparent, electrically conductive graphene nanoribbon thin films as deicing heating layers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2014, 6, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.G.; Ozgur, G.; Sevkat, E. Electrical resistance heating for deicing and snow melting applications: Experimental study. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2019, 160, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Chung, D. Carbon fiber mats as resistive heating elements. Carbon 2003, 41, 2436–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.-H.; Song, J.-W.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Park, J.-K.; Oh, S.-K.; Han, C.-S. Transparent Film Heater Using Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Advanced Materials 2007, 19, 4284–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Liu, K.; Wu, J.-S.; Liu, L.; Cheng, J.G.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Fan, S.; Jiang, K. Flexible, Stretchable, Transparent Conducting Films Made from Superaligned Carbon Nanotubes. Advanced Functional Materials 2010, 20, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jinsong, L. Self-heating fiber reinforced polymer composite using meso/macropore carbon nanotube paper and its application in deicing. Carbon 2014, 66, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Hawkins, S.; Falzon, B.G. An advanced anti-icing/de-icing system utilizing highly aligned carbon nanotube webs. Carbon 2018, 136, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, J.S.; Park, J.-H.; Hong, Y.-K.; Hong, C.H.; Kim, K.K. Flexible plane heater: Graphite and carbon nanotube hybrid nanocomposite. Synthetic Metals 2015, 203, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, F.; Sorrentino, A.; Palmieri, B.; Vertuccio, L.; De Tommaso, G.; Pantani, R.; Guadagno, L.; Martone, A. Lightweight 3D-printed heaters: design and applicative versatility. Composites Part C: Open Access 2024, 15, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Kempers, R.; Amirfazli, A. 3D printed electro-thermal anti- or de-icing system for composite panels. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2019, 166, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Raj L, P.; Jo, J.-H.; Cho, M.-Y.; Kweon, J.-H.; Myong, R.S. Multiphysics anti-icing simulation of a CFRP composite wing structure embedded with thin etched-foil electrothermal heating films in glaze ice conditions. Composite Structures 2021, 276, 114441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, M.; Amirfazli, A. A novel electro-thermal anti-icing system for fiber-reinforced polymer composite airfoils. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2013, 87, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, A. Comparative Evaluation of Embedded Heating Elements as Electrothermal Ice Protection Systems for Composite Structures. Masters, Concordia University, 2017.

- Kim, M.; Sung, D.H.; Kong, K.; Kim, N.; Kim, B.-J.; Park, H.; Park, Y.-B.; Jung, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Characterization of resistive heating and thermoelectric behavior of discontinuous carbon fiber-epoxy composites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2016, 90, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, B.G.; Robinson, P.; Frenz, S.; Gilbert, B. Development and evaluation of a novel integrated anti-icing/de-icing technology for carbon fibre composite aerostructures using an electro-conductive textile. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2015, 68, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbagian, M. Multidisciplinary Optimization of In-Flight Electro-Thermal Ice Protection Systems. 2015.

- Pourbagian, M.; Habashi, W. Aero-thermal optimization of in-flight electro-thermal ice protection systems in transient de-icing mode. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2015, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Yu, L.; Zhu, D.; Mao, X. Power optimization of the aircraft electrothermal de-icing heaters. Applied Thermal Engineering 2025, 280, 128236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakakis, G.; Tomara, G.; Datsyuk, V.; Sygellou, L.; Bakolas, A.; Tasis, D.; Parthenios, J.; Krontiras, C.; Georga, S.; Galiotis, C.; et al. Mechanical, Electrical, and Thermal Properties of Carbon Nanotube Buckypapers/Epoxy Nanocomposites Produced by Oxidized and Epoxidized Nanotubes. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, R.; Raj, L.P.; Jo, J.-H.; Cho, M.-Y.; Kweon, J.-H.; Myong, R.S. Multiphysics anti-icing simulation of a CFRP composite wing structure embedded with thin etched-foil electrothermal heating films in glaze ice conditions. Composite Structures 2021, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbagian, M.; Habashi, W.G. Aero-thermal optimization of in-flight electro-thermal ice protection systems in transient de-icing mode. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2015, 54, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saripally, A. A Micromechanical Approach to Evaluate the Effective Thermal Properties of Unidirectional Composites. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Affdl; Patterson, W. The Halpin-Tsai Equations: A Review. Polymer Engineering and Science 1976, 16, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.A. Computational techniques for fluid dynamics 2; Springer-Verlag: 1988.

- Adeyi, T.A.; Alabi, O.O.; Towoju, O.A. Influence of Airfoil Geometry on VTOL UAV Aerodynamics at Low Reynolds Numbers. Archives of Advanced Engineering Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-s.; Jo, H.; Choe, H.-s.; Lee, D.-s.; Jeong, H.; Lee, H.-r.; Kweon, J.-h.; Lee, H.; Shin Myong, R.; Nam, Y. Electro-thermal heating element with a nickel-plated carbon fabric for the leading edge of a wing-shaped composite application. Composite Structures 2022, 289, 115510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, D.A., Hasan. Thermal Analysis and Design of Composite Structures under Realistic Flow Conditions. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Engineering Technologies (ICENTE’23) Konya/Turkiye, 23–25 November 2023, 2023; pp. 196–204.

- Cengel. Heat Transfer: A Practical Approach; 2016.

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 4th Edition ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York City, New York, 1996.

- Sampson, J.R. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems (John H. Holland). SIAM Review 1976, 18, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning; Addison-Wesley: New York, 1989.

- Jong, K.A.D. An Analysis Of The Behavior Of A Class Of Genetic Adaptive Systems. 1975.

- Bahrami, M. Forced Convection Heat Transfer, ENSC 388. 2011.

- Cao, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Chen, J. Multi-Functional Properties of MWCNT/PVA Buckypapers Fabricated by Vacuum Filtration Combined with Hot Press: Thermal, Electrical and Electromagnetic Shielding. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaundal, R.; Patnaik, A.; Satapathy, A. Comparison of the Mechanical and Thermo-Mechanical Properties of Unfilled and SiC Filled Short Glass Polyester Composites. Silicon 2012, 4, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaggar, G.; Kamate, S.C.; Badyankal, P. A study on thermal conductivity enhancement of silicon carbide filler glass fiber epoxy resin hybrid composites. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutnuri, B. Thermal conductivity characterization of composite materials. 2006.

- Han, S.; Chung, D. Increasing the through-thickness thermal conductivity of carbon fiber polymer–matrix composite by curing pressure increase and filler incorporation. Composites Science and Technology - COMPOSITES SCI TECHNOL 2011, 71, 1944–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, Y.; Chung, D. Through-thickness thermal conduction in glass fiber polymer–matrix composites and its enhancement by composite modification. Journal of Materials Science 2016, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Román, F.; Calventus, Y.; Hutchinson, J.M. Remarkable Thermal Conductivity of Epoxy Composites Filled with Boron Nitride and Cured under Pressure. Polymers 2021, 13, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable name | Heat generation rate | Width of Heater band | kx value for the composite | k value for the surface material |

| Result | 12715 (W/m3) | 25 cm | 0.6(W/m.K) | 10 (W/m.K) |

| Design Variable | Perturbed and Optimum Values | Surface Temperature at the Half-Length (K) |

| Volumetric heat generation rate | +10%0-10% | 282.55 280.97 278.27 |

| Composite in-plane thermal conductivity | +10%0-10% | 279.63 280.97 279.59 |

| Surface material thermal conductivity | +10%0-10% | 280.47 280.97 278.64 |

| Variable name | Heat generation rate | Width of Heater band | Orientation of the plies | k value for the surface material |

| Result | 11653 (W/m3) | 25 cm | 0 (deg) | 10 (W/m.K) |

| Heat generation rate (W/m3) | Ply 1 orientation (deg) | Ply 2 orientation (deg) | Ply 3 orientation (deg) | Surface coating thermal conductivity (W/m.K) |

| 2070 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).