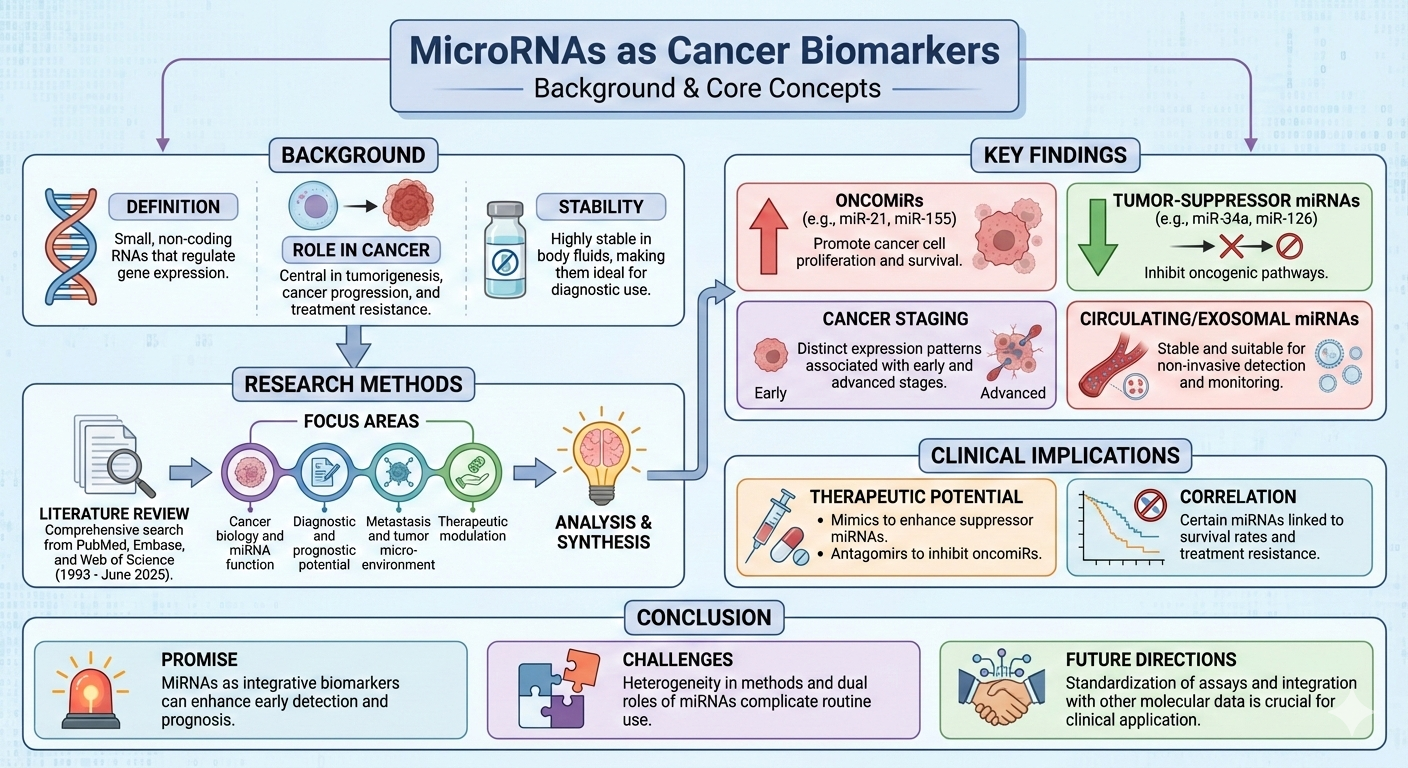

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are evolutionarily conserved, non-coding RNAs of approximately 20–25 nucleotides that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. Since the identification of lin-4 in Caenorhabditis elegans in 1993 and the subsequent discovery of human miRNAs such as let-7 and miR-21, these molecules have been recognised as critical regulators of cell-cycle progression, apoptosis, differentiation, and stress responses (He & Hannon, 2004; Lee et al., 1993). By fine-tuning gene networks, miRNAs maintain tissue homeostasis and enable adaptive cellular responses (Heikkinen, 2014).

miRNA biogenesis follows a tightly controlled pathway: transcription by RNA polymerase II; Drosha/DGCR8-mediated processing to generate precursor hairpins; nuclear export via Exportin-5; and cytoplasmic cleavage by Dicer to yield mature miRNAs. These mature species are loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), guiding sequence-specific repression of target mRNAs (Billi et al., 2024). Although classically viewed as post-transcriptional repressors, emerging evidence indicates that certain miRNAs—termed “up-miRs”—can stabilise transcripts or enhance translation, underscoring their context-dependent versatility (Vasudevan, 2012; Metanat et al., 2025).

Aberrant miRNA expression is a hallmark of oncogenesis. Oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs), such as miR-21, repress tumor suppressors to promote proliferation, invasion, and therapy resistance (Zhang et al., 2023). Conversely, tumor-suppressive miRNAs, exemplified by the p53-driven miR-34 family, inhibit oncogenic drivers including MYC and MET, enforcing apoptosis and growth arrest (He, Lowe, & Hannon, 2007). Some miRNAs—such as miR-125b and miR-126—display dual, context-dependent behaviour, acting as tumour suppressors or oncogenes according to tissue type, disease stage, or micro environmental cues (Zhang et al., 2022). Beyond tumour-intrinsic functions, miRNAs shape the tumour microenvironment by modulating angiogenesis, stromal remodelling, immune evasion, and metabolic adaptation. Tumour-derived exosomes disseminate miRNAs systemically, conditioning pre-metastatic niches and facilitating distant spread (Kalluri & LeBleu, 2020). Their stability in circulation has spurred evaluation as minimally invasive biomarkers for early detection, prognosis, and therapy monitoring.

Against this backdrop, the present review offers a comprehensive, critically appraised synthesis of evidence on miRNAs across major body fluids in cancer. Building on studies of circulating and non-circulating miRNAs, we delineate their diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive roles; compare performance across biofluids and tumour types; and highlight potential in early detection, disease monitoring, and treatment guidance. By integrating data on assay platforms, analytical approaches, and clinical endpoints, we identify key sources of methodological heterogeneity, clarify context-dependent behaviour of individual miRNAs and panels, and outline translational gaps that must be bridged before routine clinical implementation. Ultimately, we position miRNA-based liquid and minimally invasive biopsy strategies within contemporary precision oncology frameworks and propose a roadmap for future research and clinical validation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Methods

We conducted a comprehensive review to synthesise current evidence on miRNAs as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarkers across human malignancies, with emphasis on their dual roles as oncogenic drivers (oncomiRs) and tumour-suppressor regulators. The review adhered to a structured narrative approach consistent with the standards of high-impact clinical journals.

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We systematically searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science for articles published from January 1993 to June 2025, spanning the discovery of miRNAs to recent advances in clinical translation. The search combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms related to miRNAs and cancer, including: “microRNA”, “miRNA”, “oncomiR”, “tumour suppressor microRNA”, “circulating microRNA”, “exosomal microRNA”, “cancer biomarker”, “early detection”, “prognosis”, “metastasis”, “epithelial–mesenchymal transition”, and “tumour microenvironment”. We additionally searched for specific, frequently implicated miRNAs—such as miR-21, miR-155, miR-10b, miR-34a, miR-126, miR-145, miR-124, the miR-200 family, and the miR-15a/16-1 and miR-17–92 clusters.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included peer-reviewed original research and review articles that investigated human cancers or clinically relevant preclinical models (cell lines, xenografts, or animal models) with clear implications for human disease. Eligible studies examined miRNA biogenesis and regulatory mechanisms relevant to oncogenesis; miRNA dysregulation in tumour tissues or body fluids; and roles as diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive biomarkers. We also included studies on associations between miRNAs and metastasis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, or the tumour microenvironment, as well as investigations of therapeutic targeting of miRNAs or their use as therapeutic agents (miRNA mimics or inhibitors). Studies were required to report measurable outcomes, including differential miRNA expression; correlations with clinic pathological features; survival endpoints (overall, progression-free, or disease-free survival); treatment response; or metastasis patterns. We excluded articles without primary or secondary data on cancer-related miRNAs (for example, studies confined to non-malignant diseases without extrapolation to cancer), non–peer-reviewed materials (such as conference abstracts without full text, theses, and editorials lacking data), and studies exclusively focused on non-human species without translational or mechanistic relevance to human cancer. No language restrictions were applied at the search stage; however, only studies with sufficient detail in English to permit data extraction and interpretation were retained in the final synthesis, which may introduce language bias.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

From each eligible study, we extracted information on cancer type and patient population; biological specimen (tissue, serum, plasma, whole blood, urine, exosomes, and other body fluids); profiled miRNAs and direction of dysregulation; putative or validated targets and downstream pathways; study design (discovery or validation; prospective or retrospective); diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve when reported); prognostic or predictive associations (for example, hazard ratios and correlations with stage, grade, metastasis, or recurrence); and functional evidence from mechanistic gain- or loss-of-function experiments in vitro and in vivo. Given substantial heterogeneity in study designs, assay platforms (qRT-PCR, microarrays, next-generation sequencing), normalisation strategies, and definitions of clinical endpoints, we did not perform a quantitative meta-analysis. Instead, we undertook a thematic narrative synthesis structured around canonical and non-canonical miRNA biogenesis and regulatory networks; roles of oncomiRs and tumour-suppressor miRNAs in key cancer hallmarks; circulating and exosomal miRNAs as minimally invasive diagnostics; and miRNAs as prognostic and metastatic biomarkers, including involvement in epithelial–mesenchymal transition and organ-specific spread. Within each domain, we integrated mechanistic and clinical data to highlight miRNAs with consistent, robust associations across studies and to delineate those with stage-specific or context-dependent effects.

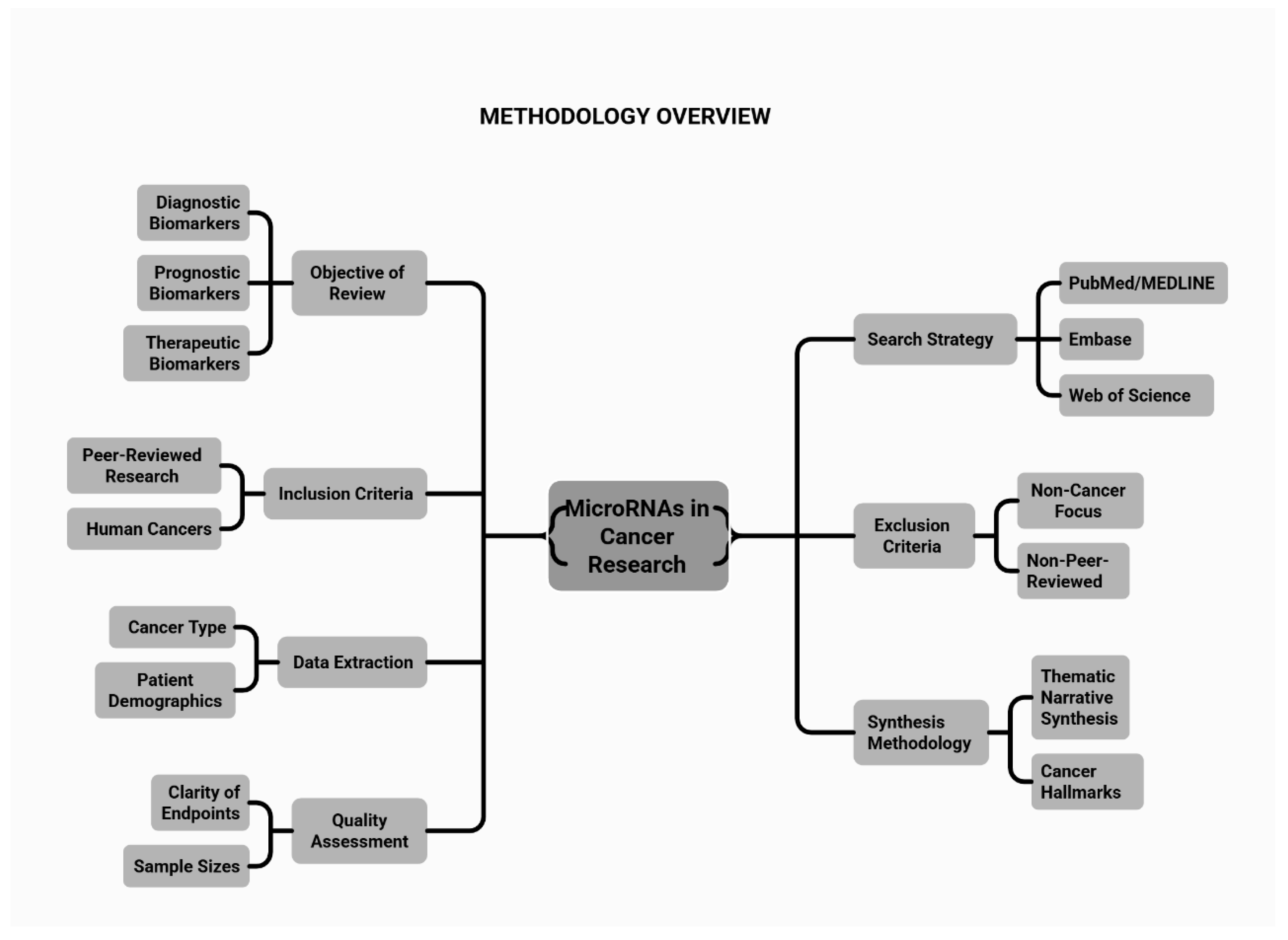

2.5. Assessment of Study Quality and Limitations

Although formal risk-of-bias tools were not systematically applied, studies were qualitatively appraised for clarity of clinical endpoints and statistical analysis; sample size and presence of independent validation cohorts; robustness and reproducibility of miRNA measurements (including technical replicates, internal controls, and normalisation methods); and adjustment for relevant confounders in multivariable models. Particular attention was paid to assay standardization, given that variability in platforms and pre-analytical conditions (sample collection, processing, and storage) can materially affect miRNA quantification. Recognised limitations—including publication bias favouring positive results, small single-centre cohorts, and the paucity of large prospective validation studies—were explicitly considered when drawing conclusions and setting priorities for future research. An overview of the methodology is illustrated in

Figure 1.

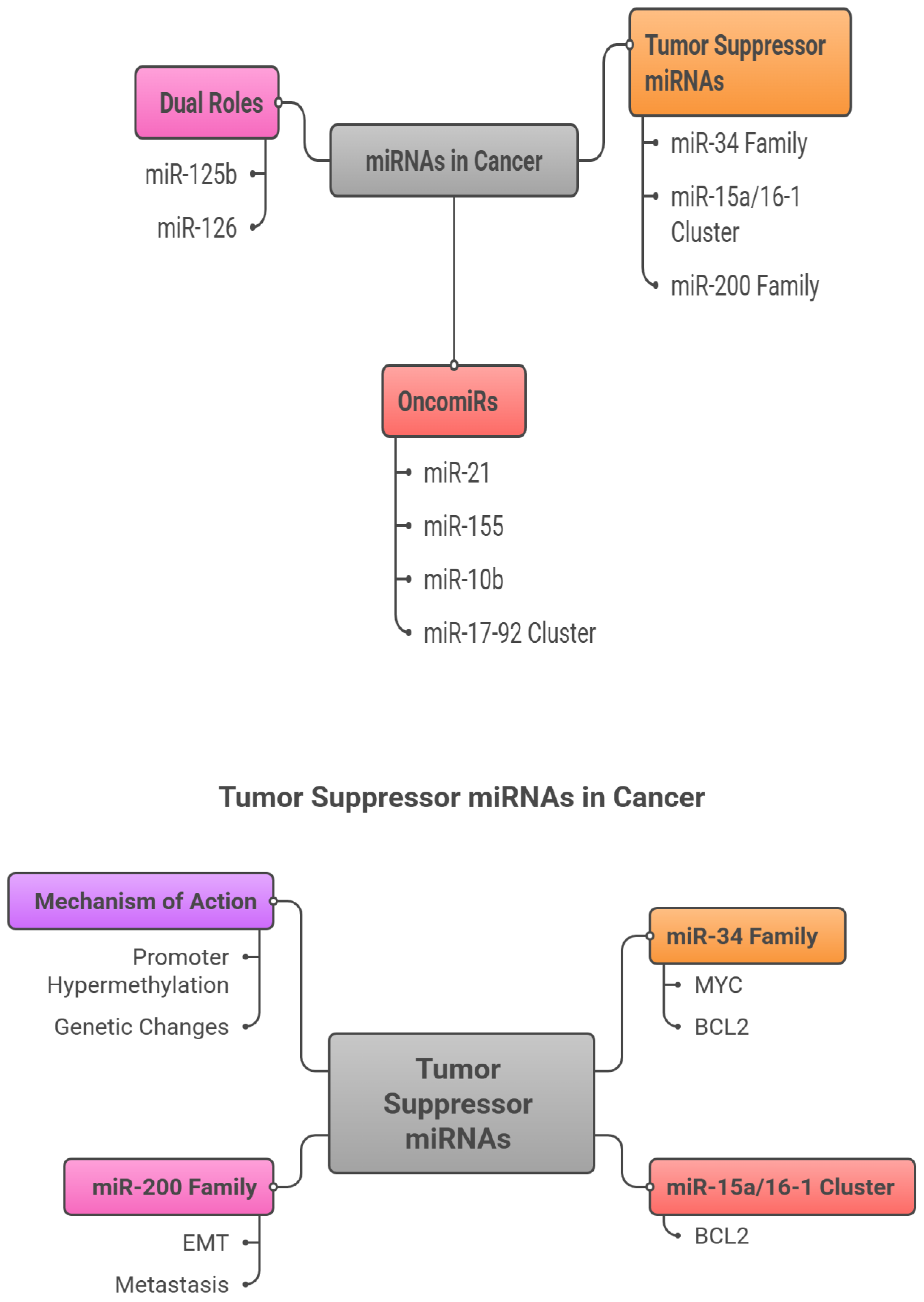

3. miRNAs in Cancer Crosstalk: Tumor Suppressors versus OncomiRs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNAs that exert pivotal control over post-transcriptional gene regulation and are increasingly recognized as central players in cancer biology (Calin & Croce, 2006). Broadly, they fall into two functional categories with opposing influences on tumorigenesis. Tumor suppressor miRNAs, exemplified by the miR-34 family and the miR-15a/16-1 cluster, constrain oncogenic signaling and promote apoptosis, thereby protecting against malignant transformation (Esquela-Kerscher & Slack, 2006). In contrast, oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs)—such as miR-21 and miR-155—are often upregulated in cancers and drive tumorigenesis by repressing tumor suppressor genes and activating pro-tumor pathways. Appreciating this bidirectional regulatory axis is essential for informing therapeutic development and improving clinical outcomes (Garzon et al., 2009; O’connell et al., 2010).

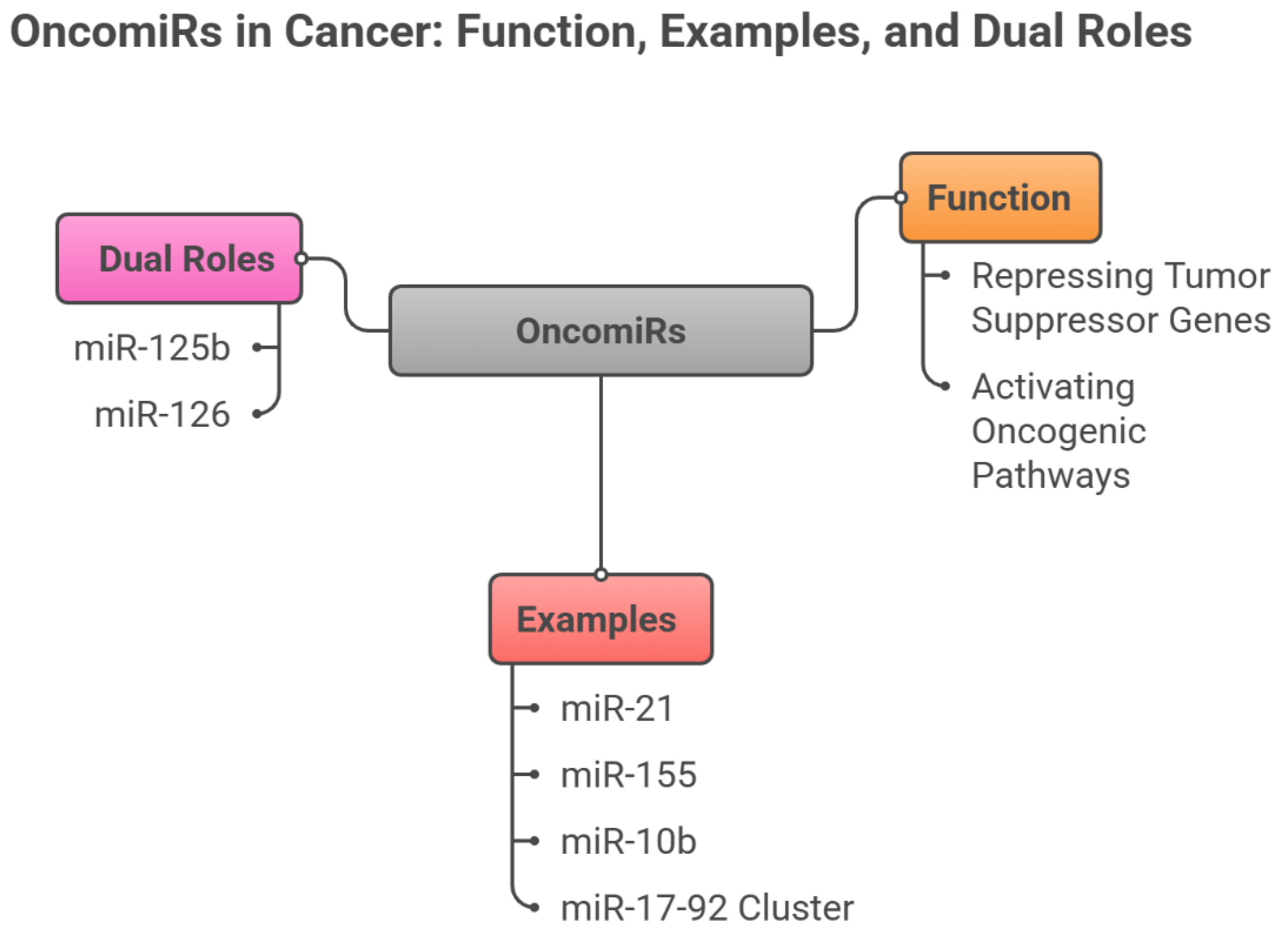

3.1. OncomiRs (Oncogenic miRNAs)

OncomiRs are frequently overexpressed across malignancies and promote tumor initiation and progression by silencing tumor suppressor targets, activating oncogenic cascades, and reshaping the tumor microenvironment (Otmani et al., 2022). Among the best-characterized, miR-21 is broadly overexpressed in solid tumors and suppresses PTEN and PDCD4, thereby engaging PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling to foster proliferation, invasion, and treatment resistance (Chan et al., 2005). miR-155 is another potent oncomiR—upregulated in lymphomas and several solid cancers—where it targets SHIP1 and SOCS1, enhancing inflammatory signaling, immune evasion, and drug resistance (O’connell et al., 2010). miR-10b is tightly linked to metastasis: through repression of HOXD10 and consequent derepression of RhoC, it promotes tumor cell migration and invasion, with pronounced effects in breast and colorectal cancers (Ma et al., 2007). The miR-17–92 cluster, frequently amplified in neuroblastomas and lymphomas, promotes proliferation by inhibiting PTEN, p21, and E2F1 (He et al., 2005). Notably, some miRNAs—including miR-125b and miR-126—exhibit context dependence, acting as tumor suppressors in certain tissues and as oncogenes in others (Le et al., 2009), underscoring the complexity of miRNA-driven regulation in cancer.

3.2. Tumor Suppressor miRNAs

Tumor suppressor miRNAs maintain cellular homeostasis by dampening oncogenic pathways, promoting apoptosis, and limiting unchecked proliferation. Their loss—through promoter hypermethylation, genetic alteration, or impaired biogenesis—facilitates tumor initiation and progression (Esquela-Kerscher & Slack, 2006). The miR-34 family is among the best characterized and is directly regulated by p53. miR-34a targets key oncogenes, including MYC, MET, and BCL2, enforcing apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest; its reduced expression is repeatedly observed in lung, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers, where it correlates with poor prognosis and chemoresistance (Chang et al., 2007; He, He, Lim, et al., 2007). The miR-15a/16-1 cluster induces apoptosis by suppressing the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2; deletion or downregulation is a hallmark of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and is associated with chemoresistance. Similarly, the miR-200 family constrains epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2, thereby limiting invasion and metastatic spread (Cimmino et al., 2005). Additional tumor suppressor miRNAs include miR-145, which downregulates c-MYC and FSCN1 to suppress proliferation and invasion in breast and prostate cancers [

6], and miR-126, which inhibits angiogenesis by targeting VEGF-A and PI3K signalling (Sachdeva et al., 2009). Collectively, these miRNAs function as critical brakes on oncogenic signalling; their attenuation removes key safeguards against malignant transformation (Frixa et al., 2015). The detailed mechanisms underlying microRNA-mediated crosstalk in tumor progression are described in

Figure 2,” miRNAs in Cancer Crosstalk: Tumor Suppressors versus OncomiRs”.

4. OncomiRs as Cancer Biomarkers

4.1. Early Detection and Diagnosis

The inherent stability and disease-specific expression profiles of circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) position them as compelling candidates for early cancer detection. Multiple miRNAs have shown strong potential as minimally invasive biomarkers capable of identifying malignancy at stages preceding conventional imaging findings or the onset of clinical symptoms.

miR-21 (microRNA-21) is among the most extensively investigated circulating miRNAs due to its consistent upregulation across a wide range of cancers, including breast, glioblastoma, pancreatic, and non-small cell lung cancers (Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). Its notable stability in blood and other body fluids, together with its involvement in tumorigenic pathways, underscores its utility for early detection. Functionally, miR-21 exerts oncogenic effects by targeting tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN and PDCD4, thereby promoting proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Elevated circulating levels can be detected months before radiographic or clinical evidence emerges, mirroring molecular alterations during tumor initiation and early progression (Diansyah et al., 2021). This temporal lead time makes miR-21 particularly valuable for screening high-risk populations—for example, individuals with familial predisposition or dense breast tissue—where earlier detection can substantially improve outcomes. Supporting data are robust: Wang et al. (2020) reported increased plasma miR-21 months before diagnosis in breast cancer; Zhang et al. (2022) noted significant serum elevation in NSCLC, often years before radiographic detection; and Liu et al. (2021) observed marked pre-symptomatic increases in glioblastoma, highlighting its role in early diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring (Bautista-Sánchez et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2011).

miR-155 likewise plays a central role in immune regulation and oncogenesis. Elevated circulating miR-155 has been documented across diverse malignancies, notably lymphomas and breast cancer, supporting its promise for early detection, prognostication, and disease monitoring. By targeting genes governing differentiation and proliferation, miR-155 influences both tumor biology and anti-tumor immunity. Early rises in circulation may reflect initial tumorigenic changes or immune activation within the tumor microenvironment, enhancing its value as a screening tool (Lawrie et al., 2008). Clinically, Li et al. (2019) found significantly higher serum miR-155 at diagnosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) versus healthy controls, with declines following effective therapy, suggesting utility as a dynamic indicator of tumor burden and treatment response. In breast cancer, Zhang et al. (2020) showed elevated miR-155 even at stage I. Given its early detectability and treatment-responsive dynamics, miR-155 is well suited to serial monitoring for assessing response and detecting early recurrence (Koumpis et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2012).

miR-10b has been widely studied for its role in promoting invasion, early progression, and metastasis. By targeting HOXD10, a suppressor of cell motility, miR-10b enhances invasive capacity and tumor cell migration. Elevated circulating levels frequently mirror early invasive behavior and may be detectable prior to clinically evident metastasis, making miR-10b valuable for early detection and risk stratification (Ma et al., 2007; Sheedy & Medarova, 2018). Consistent reports indicate higher blood miR-10b in patients with invasive or metastatic disease—including breast, colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancers—than in those with localized tumors. Notably, detection often precedes clinical metastasis. Advances in exosome-based assays have improved diagnostic accuracy, with exosomes miR-10b showing high specificity for early metastatic potential. Therapeutically, targeted inhibition of miR-10b has demonstrated suppression of dissemination, highlighting its dual potential as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target (Chen & He, 2021; Dwedar et al., 2021; Cho et al., 2020).

Members of the miR-200 family, particularly miR-200a and miR-200c, are key regulators of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), a central process in metastasis. Altered expression across cancer types suggests utility for early diagnosis. Serum miR-200a and miR-200c are elevated in early-stage ovarian and breast cancers, with levels correlating positively with tumor size and stage (Song et al., 2021). Beyond early detection, these miRNAs provide insight into tumor progression and aggressiveness, enabling risk stratification and informing timely intervention, especially where earlier diagnosis is prognostically decisive (Gregory et al., 2008; McDougall et al., 2011).

miR-141, another miR-200 family member, has emerged as a non-invasive urinary biomarker. Liu et al. (2022) reported significantly higher urinary miR-141 in prostate cancer versus healthy individuals. Given the practicality and non-invasiveness of urine sampling, miR-141 offers a convenient screening approach that may facilitate diagnosis prior to symptom onset (Mogilyansky & Rigoutsos, 2013).

The oncogenic miR-17-92 cluster—which includes miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a/b, miR-20a, and miR-92a—also holds diagnostic promise. Kim et al. (2019) showed detectability in plasma from early neuroblastoma patients, with levels correlating with tumor burden, supporting early diagnosis and severity assessment. Plasma detection of this cluster offers a minimally invasive modality for monitoring neuroblastoma and potentially other malignancies (Luo & Wen, 2024).

4.2. Prognostic Indicators

miR-21 as one of the best-characterized oncomiRs, miR-21 is frequently overexpressed in breast, lung, and gastric cancers. Elevated circulating miR-21 consistently associates with poorer overall survival (OS). For instance, Wang et al. (2022) demonstrated that higher circulating miR-21 predicts worse prognosis in lung cancer, while Zhang et al. (2022) linked increased plasma miR-21 with advanced stage and reduced survival in gastric cancer, supporting its role as a non-invasive marker of disease progression. Despite the enthusiasm, variability in assay platforms and cutoff thresholds across studies underscores the need for methodological standardization before reliable clinical deployment (Wang et al., 2022). miR-155 another prominent oncomiR, miR-155, correlates with adverse outcomes in lymphomas and solid tumors such as breast cancer. High expression is associated with aggressive features, increased relapse, and reduced progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. In DLBCL, Li et al. (2019) reported that elevated miR-155 predicts poorer prognosis, likely reflecting its modulation of immune and inflammatory pathways that foster tumor growth and resistance. In breast cancer, Zhang et al. (2020) observed associations between increased miR-155 and higher recurrence and therapeutic resistance. Mechanistically, miR-155 targets tumor suppressors and modulates cytokine signaling, promoting a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment. However, inter-study heterogeneity in expression assessment and tumor biology remains a barrier to widespread clinical adoption (Grimaldi et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2023).

miR-10b Circulating miR-10b has emerged as a marker of metastatic propensity. Elevated serum/plasma levels associate with lymph node involvement and reduced disease-free survival (DFS). In breast cancer, higher miR-10b predicted metastatic spread, consistent with its effects on migration and invasion pathways involving HOXD10 and RHOC. These data support miR-10b as a dynamic biomarker for early detection of metastatic progression. Further validation is needed to define specificity and integration into multi-marker prognostic models (Ma, 2010; Ma et al., 2007).

4.3. Metastatic Markers

Recent advances have clarified how oncomiRs regulate metastasis by targeting pathways involved in EMT, cell motility, and extracellular matrix remodeling. For example, miR-9 promotes metastasis by downregulating E-cadherin, thereby inducing EMT and enhancing motility (Ma et al., 2010). miR-181a increases metastatic potential in colorectal and breast cancers through regulation of migration-related genes (Ji et al., 2014). Conversely, the miR-200 family suppresses metastasis by inhibiting EMT via direct targeting of ZEB1 and ZEB2; their downregulation is linked to enhanced metastatic capacity (Ji et al., 2014). miR-10b exemplifies oncomiR-driven invasion: by binding the 3′ UTR of HOXD10 mRNA, it represses HOXD10, which in turn derepresses genes implicated in cytoskeletal dynamics and matrix degradation—such as RhoC, MT1-MMP, and MMP2—facilitating invasion and metastatic spread (Ma et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2015). Elevated miR-10b is consistently observed in metastatic tissues and in circulation, correlating with metastatic burden and poorer outcomes across multiple cancers, including breast and pancreatic carcinomas (Ma et al., 2007). Detection in plasma or tissue can thus inform prognosis and guide therapy. A deeper understanding of the interplay among these oncomiRs is critical to earlier metastasis detection, targeted therapeutic development, and improved outcomes in advanced disease (Parrella et al., 2014). The literature on the clinical applications of microRNAs as cancer biomarkers (oncomiRs) is summarized in

Table 1.

5. Tumor-Suppressor miRNAs as Cancer Biomarkers

5.1. Early Detection and Diagnosis

Recent work has identified circulating tumour-suppressor miRNAs—including miR-34a, miR-126, miR-145, and miR-124—as promising minimally invasive biomarkers because of their stability in blood and their consistent, cancer-specific dysregulation. Their value for early detection lies in their ability to mirror tumorigenic changes well before overt clinical manifestations.

miR-34a is a key effector of the p53 tumour-suppressor pathway, induced by cellular stressors such as DNA damage and constraining tumour growth by repressing oncogenes and cell-cycle regulators, including CDK6, cyclin D1, and BCL2, thereby promoting cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis (Cole et al., 2008). miR-34a also impedes epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) by targeting transcription factors such as ZEB1, ZEB2, and SNAIL, and by directly inhibiting MET, a receptor that drives proliferation and migration, collectively reducing metastatic potential (Cole et al., 2008). Loss of miR-34a—frequently consequent to p53 alterations—is associated with hyper activation of oncogenic pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt, which favour aggressive tumour phenotypes (Cole et al., 2008). Recent advances in single-cell sequencing and circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) technologies allow sensitive detection of miR-34a downregulation at preclinical stages, supporting its use in early diagnosis across diverse cancers (Zhang et al., 2025). Decreased plasma or serum miR-34a is increasingly recognised as a useful biomarker in several malignancies. In non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), reduced plasma miR-34a is associated with early-stage disease and inversely related to tumour size, nodal involvement, and metastasis (Li et al., 2020). In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), low serum miR-34a provides a promising non-invasive indicator for early diagnosis, with downregulation linked to adverse prognosis and resistance to chemotherapy (Zhang et al., 2023). In colorectal cancer, serum miR-34a levels decline from the adenoma stage onwards, indicating an early role in carcinogenesis and enabling detection before frank malignancy; suppression of miR-34a results in increased expression of oncogenic targets such as MET and ZEB1, thereby enhancing metastatic capacity. In breast and prostate cancers, diminished miR-34a expression correlates with more aggressive disease and poorer survival, in part through deregulation of EMT drivers and cell-cycle-related genes (Chen et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2017).

miR-126 acts predominantly as a tumour suppressor through inhibition of angiogenesis, a process essential for tumour expansion and metastatic spread. It targets key pro-angiogenic mediators, including VEGF-A, PI3K, and SPRED1, thereby disrupting signalling pathways required for neovascularisation and tumour perfusion (Meister & Schmidt, 2010). Multiple studies describe reduced circulating miR-126 in colorectal, lung, breast, gastric, and ovarian cancers, with lower levels associated with early tumorigenic alterations (Liu et al., 2021).

Mechanistically, miR-126 limits angiogenesis and tumour progression by suppressing VEGF signalling and restraining cell migration and invasion (Meister & Schmidt, 2010). Clinically, reduced miR-126 expression is linked to advanced stage, increased microvessel density, metastasis, and unfavorable prognosis (Sasahira et al., 2012). Emerging technologies, including single-cell transcriptomics and ctDNA profiling, now allow highly sensitive assessment of miR-126 alterations and real-time evaluation of tumour angiogenesis during early tumour development and metastatic dissemination (Sasahira et al., 2012). These findings support miR-126 not only as a biomarker but also as a potential therapeutic target to suppress angiogenesis and curb tumour progression, with elevated levels in early disease offering opportunities for timely intervention, particularly in breast and gastric cancers.

miR-124 functions as an important tumour suppressor by modulating core processes that underpin invasion and metastasis, including cell migration, invasion, and survival. It targets genes implicated in cytoskeletal remodelling and signalling pathways—such as SAM68, ROCK1, and AKT2—thereby inhibiting EMT, limiting cell motility, and restraining invasive behaviour (Chen et al., 2022). Clinically, reduced serum miR-124 is consistently observed in early-stage glioma and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), underscoring its utility as a non-invasive marker for early detection (Hu et al., 2014). Emerging evidence indicates that declines in circulating miR-124 can precede overt clinical findings, further enhancing its diagnostic value (Hu et al., 2014).

5.2. Prognostic Indicators

Beyond early detection, circulating tumour-suppressor miRNAs are increasingly recognised as valuable prognostic tools, reflecting tumour biology, invasive behaviour, and metastatic potential. Reductions in plasma levels of miR-34a, miR-126, and miR-124 correlate with more aggressive phenotypes, higher likelihood of metastasis, and poorer survival; longitudinal monitoring of these miRNAs offers insights into tumour evolution, therapeutic response, and recurrence risk, with persistently low miR-34a after treatment signalling residual disease or impending relapse and potentially justifying intensified or alternative therapies (Schwarzenbach et al., 2014). Dynamic changes in circulating miRNAs can also herald metastatic spread, supporting individualised surveillance and intervention strategies (Schwarzenbach et al., 2014).

miR-34a is a particularly informative tumour suppressor, with serum downregulation associated with advanced stage and reduced survival in several cancers. In highly aggressive malignancies such as lung and pancreatic cancer, decreased serum miR-34a consistently associates with tumour progression, therapeutic resistance, and metastasis (Hassanein et al., 2021). In NSCLC, low circulating miR-34a is linked to larger primary tumors, lymph-node involvement, and distant metastases, indicative of enhanced aggressiveness. In PDAC, reduced serum miR-34a correlates with higher histological grade, chemoresistance, and shorter survival, underscoring its potential as a biomarker of disease severity (Zhao et al., 2017).

Subsequent studies have extended these observations to gastric, colorectal, and glial tumors. In gastric cancer, circulating miR-34a is markedly reduced in advanced disease, and restoration of miR-34a expression has been reported to increase chemo sensitivity (Zhang et al., 2025). In colorectal cancer, falling miR-34a levels are associated with metastasis and worse clinical outcome, supporting its role in risk stratification. In glioma, serum miR-34a provides a non-invasive indicator of tumour grade and invasive potential, informing early treatment planning (Chen et al., 2025).

Serial assessment of miR-34a can help evaluate therapeutic efficacy and detect emerging relapse or resistance. Declining levels during or after therapy may signal progression and suggest the need for treatment modification, whereas rising levels may reflect effective tumour suppression. Technological advances since 2025—such as high-throughput sequencing, digital droplet PCR, and refined ctDNA assays—have enhanced the analytical sensitivity and specificity of miR-34a measurement, facilitating its integration into personalized oncology for risk stratification, prognostic assessment, and tailored therapeutic approaches (Pan et al., 2021).

Mechanistically, miR-126 exerts tumour-suppressive effects primarily by targeting pathways controlling angiogenesis, survival, and migration. By directly repressing VEGF-A, miR-126 inhibits tumour vascularization; loss of miR-126 removes this brake, increasing angiogenesis and supporting tumour growth (Lou et al., 2017). miR-126 also constrains the PI3K/Akt pathway through regulators such as p85β, promoting apoptosis and reducing proliferation, and modulates the p-STAT3 pathway, which underpins invasion and immune evasion; reduced miR-126 results in p-STAT3 activation (Lou et al., 2017). Recent data have broadened the list of miR-126 targets to include syndecan-4 (SDC4), which affects adhesion and migration; adaptor proteins Crk and CrkL, which influence motility; and insulin receptor substrates IRS-1 and IRS-2, which support tumour metabolism and growth (Liu et al., 2023). These mechanistic insights highlight the central role of miR-126 in regulating angiogenesis, invasion, and survival.

Clinically, reduced miR-126 expression is linked to increased tumour aggressiveness, metastasis, and treatment resistance in several tumour types. In metastatic colorectal cancer, plasma miR-126 levels are substantially lower than in non-metastatic disease, and longitudinal analyses show that reduced circulating miR-126 associates with heightened metastatic risk and shorter survival (Liao et al., 2024). In NSCLC, miR-126 is significantly downregulated, particularly in metastatic lesions, and low levels predict worse prognosis and resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy, consistent with functional data demonstrating miR-126 targeting of VEGF-A and inhibition of p-STAT3 signalling.

In triple-negative breast cancer, decreased miR-126 is associated with increased invasiveness and metastatic dissemination, especially to lung and bone, and experimental restoration of miR-126 reduces metastasis, suggesting therapeutic potential. In gastric and pancreatic cancers, diminished miR-126 correlates with advanced stage and chemotherapy resistance, with regulatory targets such as syndecan-4 and matrix metalloproteinases contributing to invasive capacity (Wang et al., 2024). In prostate cancer, reduced miR-126 is linked to enhanced EMT and metastatic propensity, partly through dysregulation of PI3K/Akt signalling, implying that interventions modulating miR-126 pathways could impede disease progression (Li et al., 2023).

miR-145 exerts its tumour-suppressive activity largely by targeting oncogenic pathways and molecules involved in proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. It modulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by directly targeting genes such as RGS17 and KEAP1, thereby inhibiting tumour growth and invasion. miR-145 additionally downregulates MUC1, an oncogenic glycoprotein, and c-MYC, a central regulator of cell-cycle progression, as well as Fascin-1 (FSCN1), an actin-bundling protein that facilitates cellular protrusion and motility. Through these combined actions, miR-145 also influences EMT by repressing EMT-associated regulators, reducing invasive and metastatic potential across several cancers.

Clinical studies indicate that serum and tissue miR-145 levels are inversely related to tumour aggressiveness and patient outcome. Lower circulating miR-145 is associated with increased invasiveness, metastasis, and inferior overall survival. Wang et al. (2021) reported that reduced serum miR-145 correlates with high tumour grade, lymph-node involvement, and therapy resistance in breast and prostate cancers, supporting its use as a prognostic biomarker. Subsequent studies have shown that low serum miR-145 predicts early relapse and resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies (Wu et al., 2022), and that decreased plasma miR-145 is associated with advanced stage and metastasis, aiding risk stratification (Zhang et al., 2023). In gynaecological cancers, Chen et al. (2024) noted that patients with metastatic disease and chemoresistance have significantly lower serum miR-145 and worse prognosis.

miR-124 has also emerged as a major tumour suppressor, with reduced circulating levels consistently linked to adverse outcomes in several malignancies. Decreased serum miR-124 is associated with shorter overall survival and greater tumour aggressiveness in glioma, HCC, and cervical cancer (Zhou et al., 2019). Serum miR-124 thus represents a useful prognostic indicator for tumour progression, recurrence risk, and overall disease course. Mechanistically, miR-124 inhibits oncogenic signalling by targeting factors involved in proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis, including SOX9, STAT3, and components of the AKT pathway (Zhou et al., 2019). Because it can be measured non-invasively, serum miR-124 is attractive for guiding treatment decisions and monitoring disease dynamics.

In glioma, Li et al. (2022) showed that lower serum miR-124 strongly correlates with higher tumour grade, increased invasion, and reduced median survival. In HCC, Zhang et al. (2025) found that low circulating miR-124 predicts worse overall survival and higher post-treatment recurrence, especially when combined with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP); quantitative RT-PCR assays confirm the robustness of miR-124 measurement. In cervical cancer, declining serum miR-124 parallels tumour progression and correlates with higher recurrence and metastasis rates (Chen et al., 2024). Standardised protocols for miRNA extraction from plasma and subsequent RT-PCR facilitate reproducible quantification, and serum miR-124 profiles assist in patient stratification, recurrence prediction, and individualised therapy. Ongoing studies are exploring combined panels incorporating miR-124 with ctDNA and exosomal miRNAs to further improve predictive power and enable earlier detection.

Beyond single microRNAs, several miRNA clusters and families have pivotal roles in restraining EMT and metastasis. The miR-15a/16-1 cluster has been extensively studied for tumour-suppressive functions; between 2020 and 2025, Zhang et al. (2024) reported that downregulation of this cluster is associated with increased EMT marker expression, heightened invasiveness, and poorer prognosis in cancers including leukaemia, breast, and colorectal carcinoma. The miR-200 family (miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c) is particularly well known for suppressing EMT by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2, transcription factors that promote mesenchymal phenotypes; reduced miR-200 expression in tumour tissues and serum is associated with increased metastatic potential, reduced overall survival, and higher recurrence (Lee et al., 2022). By maintaining epithelial characteristics and restraining EMT-related genes, these miRNAs help prevent dissemination, whereas their downregulation favours progression and metastasis.

Technological advances—including quantitative PCR and next-generation sequencing—have enabled accurate assessment of these miRNAs in both serum and tissue, reinforcing their prognostic and therapeutic relevance. In chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), downregulation of the miR-15a/16-1 cluster remains a hallmark associated with progression and therapy resistance (Zhang et al., 2024). In solid tumors such as breast, colorectal, and gastric cancers, reduced expression of miR-15a/16-1 and miR-200 family members correlates with increased EMT marker expression, metastasis, and poorer survival, and preclinical models show that restoring their levels can inhibit tumour growth and metastatic spread (Zhang et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023).

The miR-200 family has been investigated intensively in lung, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers. In NSCLC, reduced miR-200 levels are associated with enhanced EMT, metastasis, and chemoresistance (Lee et al., 2022). In PDAC, downregulation of miR-200 is linked to aggressive biology and unfavourable prognosis (Wang et al., 2023). In ovarian cancer, decreased miR-200 expression correlates with higher grade, advanced stage, and recurrence (Zhang et al., 2025). Loss of miR-200 permits upregulation of ZEB1 and ZEB2, which drive EMT and invasion, and the stability of these miRNAs in serum and tissue supports their use as prognostic biomarkers for risk stratification and therapeutic decision-making in high-risk patients.

5.3. Metastatic Markers

The miR-200 family (miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c) is among the most extensively studied miRNA groups in relation to metastasis. Numerous studies demonstrate an inverse association between miR-200 expression and metastatic progression in breast, ovarian, lung, and other cancers, with low levels strongly linked to increased metastatic potential and worse clinical outcomes (Korpal et al., 2018; Song et al., 2021). Reduced circulating miR-200 can discriminate localised from metastatic disease; Zhan et al. (2022) reported higher miR-200 levels in early-stage cases and pronounced reductions in metastatic disease, while Wang et al. (2023) showed that serum miR-200a/b/c can serve as non-invasive markers for monitoring metastatic burden and severity.

Beyond the miR-200 family, miR-205 inhibits EMT by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2, and reduced serum miR-205 has been described in metastatic breast and prostate cancers (Li et al., 2024). miR-145 and miR-30a also suppress invasion and EMT, and their downregulation correlates with metastasis, including lymph-node involvement in gastric cancer and brain metastases in lung adenocarcinoma (Zhou et al., 2023).

Newer data further highlight miRNAs associated with hypoxia-driven and systemic spread. miR-210 is linked to hypoxic adaptation and metastatic dissemination, while miR-21 shows complex regulation, with lower plasma levels reported in some metastatic settings, reflecting context-dependent dynamics (Chen et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025). miR-373 and miR-17-5p are emerging markers of EMT and metastatic colonisation, with significant associations reported in ovarian, breast, and lung cancers (Wang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2025). Collectively, clinical applications of tumour-suppressor miRNAs as diagnostic, prognostic, and metastatic biomarkers are summarised in

Table 2 (Literature Review of Clinical Applications of miRNAs as Cancer Biomarkers—Tumour-suppressor miRNAs).

6. Frequency Patterns and Clinical Roles of Oncogenic and Tumor-Suppressive microRNAs in the Research Literature

This section integrates current evidence on the frequency patterns, tumor contexts, biological specimen types, and clinical functions of oncogenic (oncomiRs) and tumor-suppressive microRNAs (miRNAs) reported across selected studies. The existing literature is heavily dominated by miR-21 and miR-155 among oncomiRs, and by miR-34a and miR-126 among tumor-suppressive counterparts. Circulating biofluids—especially serum and plasma—constitute the most frequently investigated sample matrices. The primary clinical applications of oncomiRs have centred on early cancer detection, whereas tumor-suppressive miRNAs have been predominantly examined in relation to prognostic assessment. Owing to small sample sizes and pronounced methodological heterogeneity, the current findings should be interpreted descriptively, underscoring the need for rigorous effect-size reporting and prospective validation in larger, standardized cohorts.

6.1. OncomiRs: Frequency Patterns, Cancer Type, Sample Type and Clinical Roles

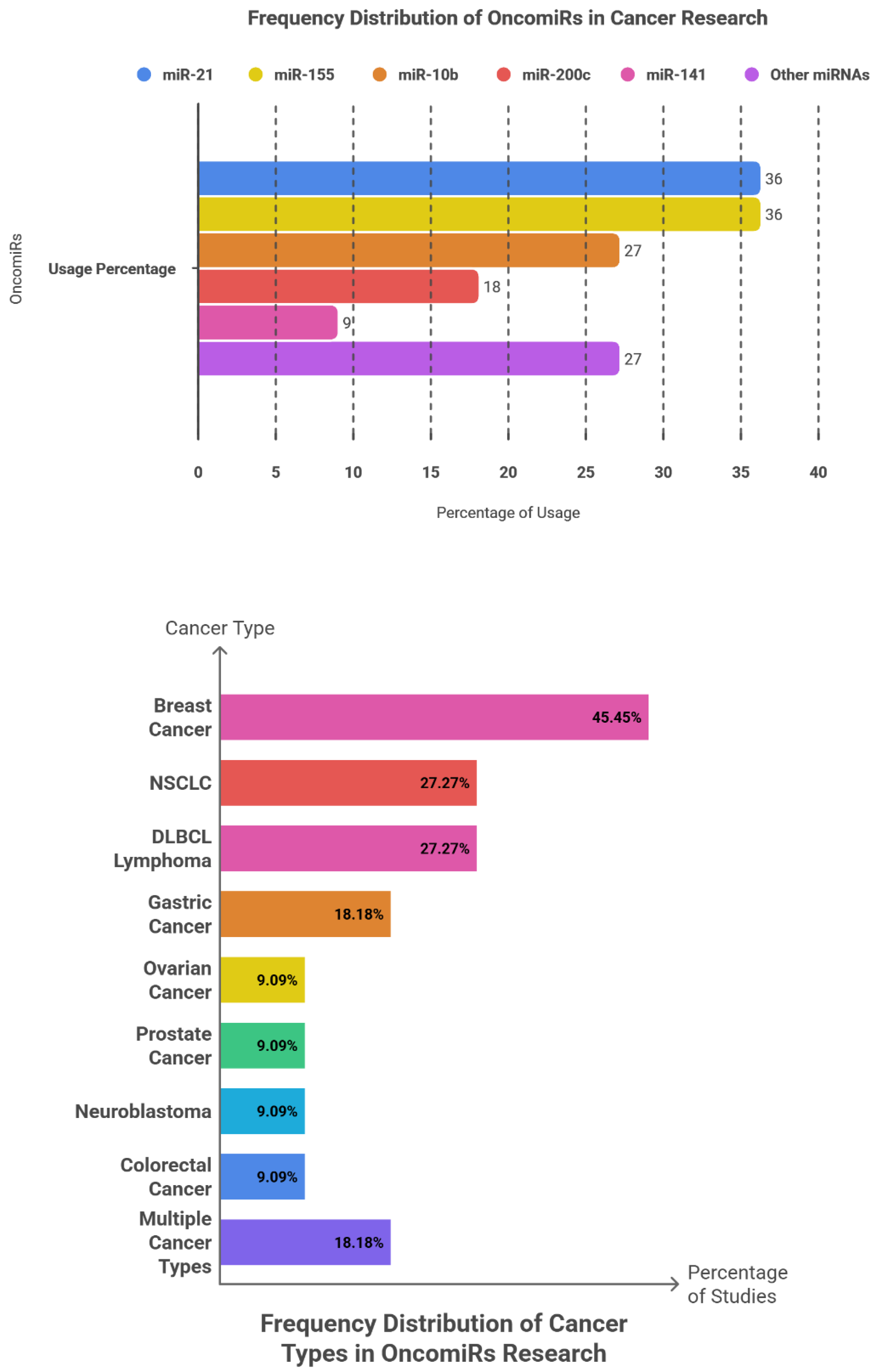

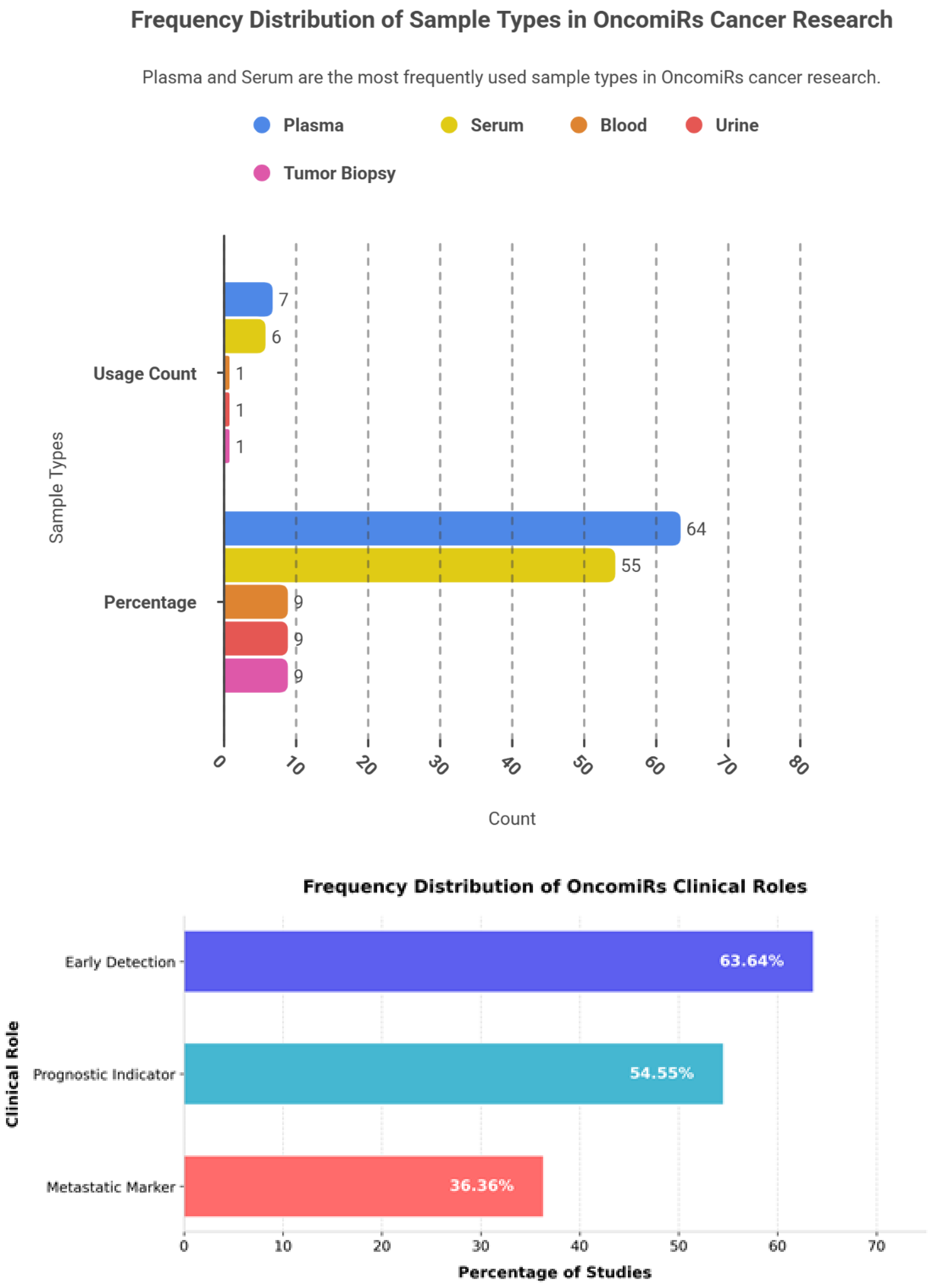

Among 11 reported events, miR-21 and miR-155 each appeared in 4 events (36.36%), jointly accounting for 72.73% of all occurrences—demonstrating a right-skewed pattern with limited diversity among remaining targets. miR-10b occurred in 3 of 11 events (27.27%), followed by miR-200c (2/11; 18.18%) and miR-141 (1/11; 9.09%). The “others” group (miR-17-92, miR-9, miR-181a) collectively comprised 27.27%. Approximate 95% Wilson confidence intervals for proportions of 4/11, 3/11, 2/11, and 1/11 were roughly 15–65%, 10–56%, 5–48%, and 2–38%, respectively, revealing broad overlap that precludes statistically meaningful differentiation among mid-ranked miRNAs.

Breast cancer accounted for the greatest proportion of events (5/11; 45.45%), followed by non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC; 3/11; 27.27%), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; 3/11; 27.27%), and gastric cancer (2/11; 18.18%). Ovarian, prostate, neuroblastoma, and colorectal cancers were each represented by one event (9.09%). The “multiple-cancer” category encompassed two events (18.18%). These distributions parallel the prevalence of these malignancies, sample accessibility, and the comparatively advanced molecular understanding of their biology.

Among the 16 reported applications, plasma was the most frequently utilized biological matrix (7; 63.64%), followed by serum (6; 54.55%), while whole blood, urine, and tissue each accounted for a single event (9.09%). The marked predominance of liquid-biopsy specimens highlights the increasing research emphasis on minimally invasive strategies for early cancer detection and disease monitoring.

Across 17 reported functional applications, early diagnostic use was most common (7; 63.64%), followed by prognostic evaluation (6; 54.55%) and identification of metastatic markers (4; 36.36%). This distribution underscores the clinical priority accorded to non-invasive diagnostic approaches and reflects the inherent challenges of experimentally characterizing metastatic progression.

The dominance of miR-21 and miR-155 aligns with their well-established mechanistic roles across multiple tumor types. miR-10b, though less frequent, holds a recognizable link to invasion and metastasis. The overall functional distribution favours diagnostic and prognostic applications. The general absence of effect size reporting and the heterogeneity of analytical platforms highlight the need for quantitative evidence synthesis and methodologically harmonized studies.

Figure 3 illustrates the frequency oncomiRs patterns, cancer-type distribution, sample matrices, and clinical roles of oncomiRs across the analysed studies.

6.2. Tumor-Suppressive miRNAs: Frequency Patterns, Cancer Type, Sample Type and Clinical Roles

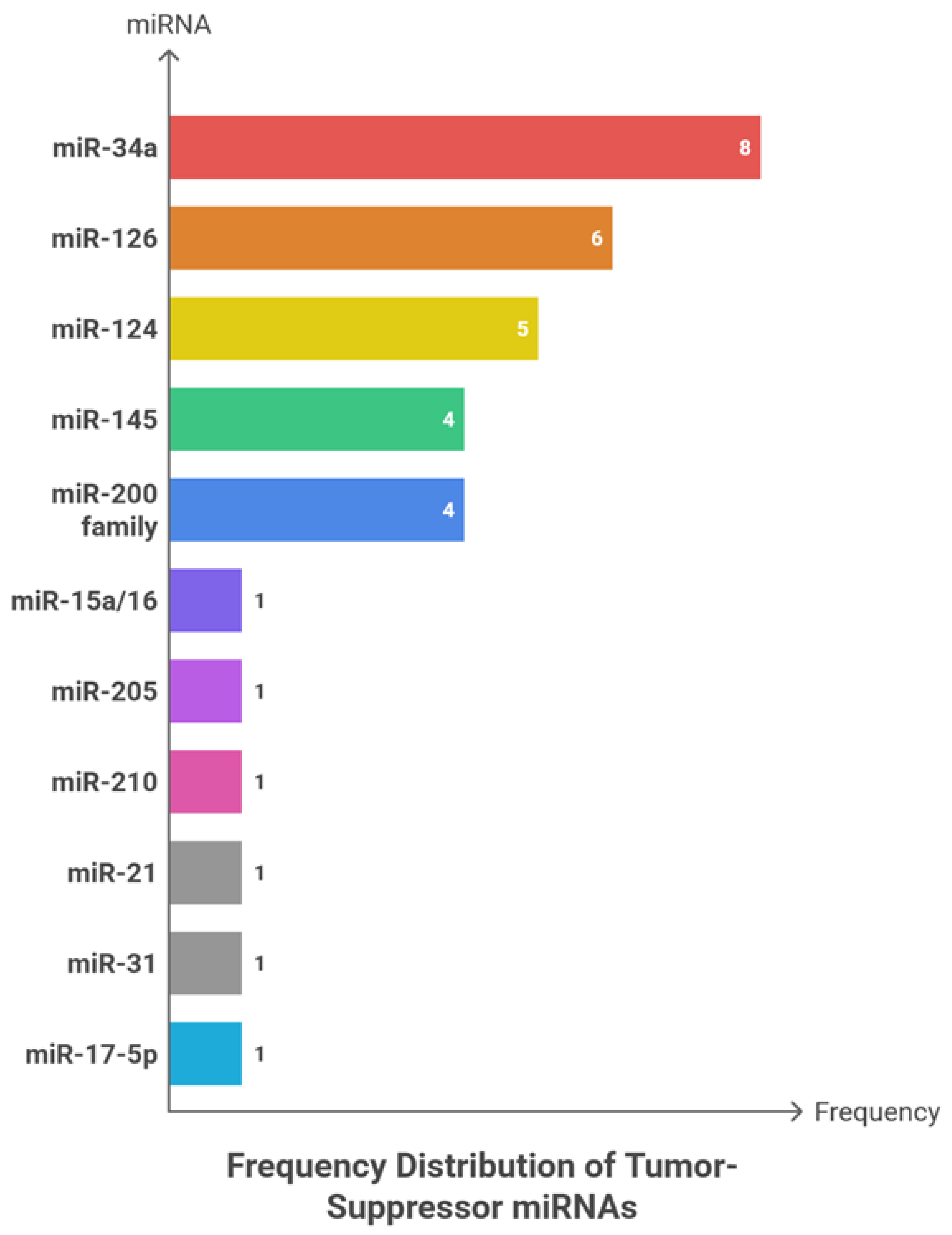

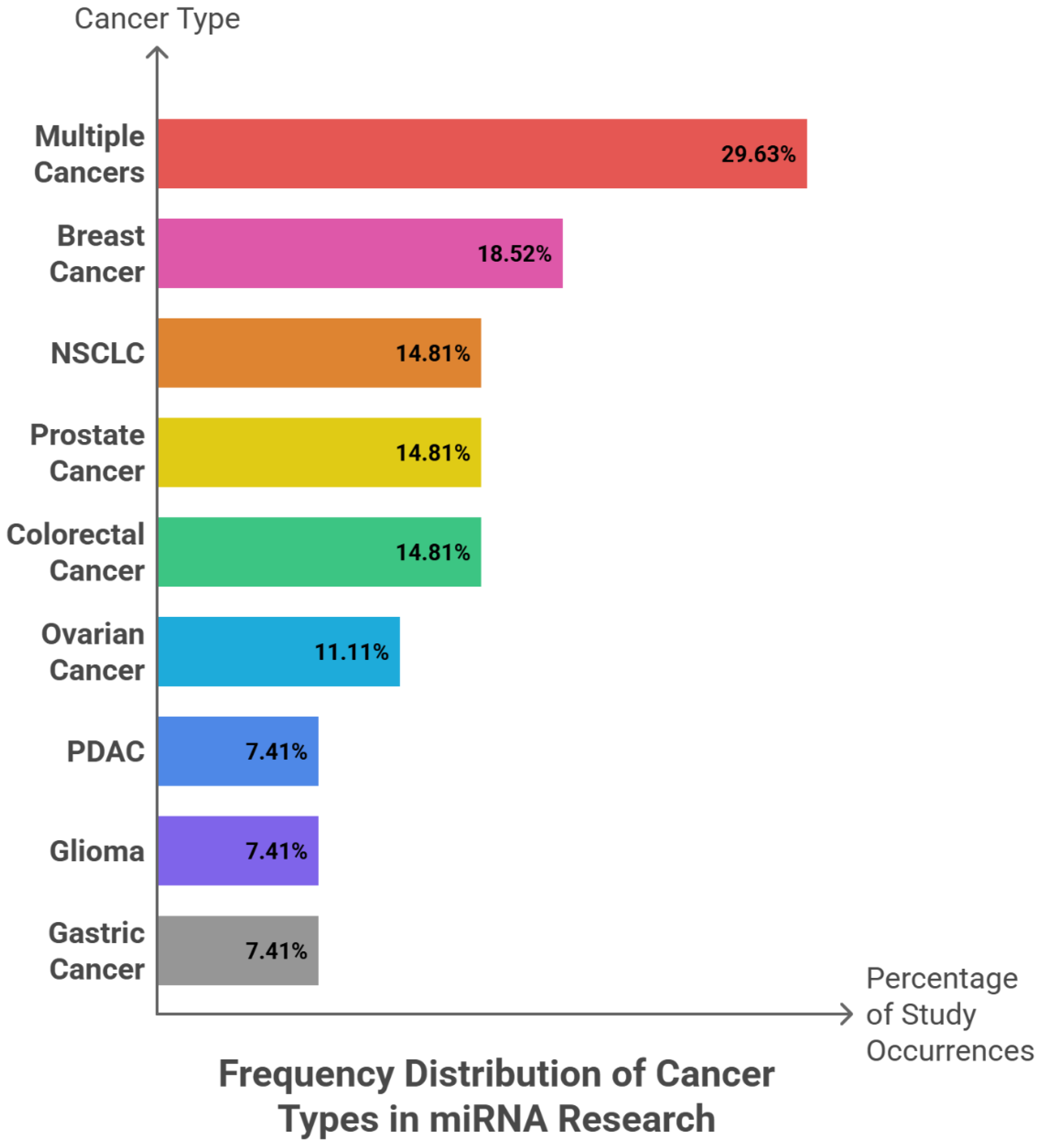

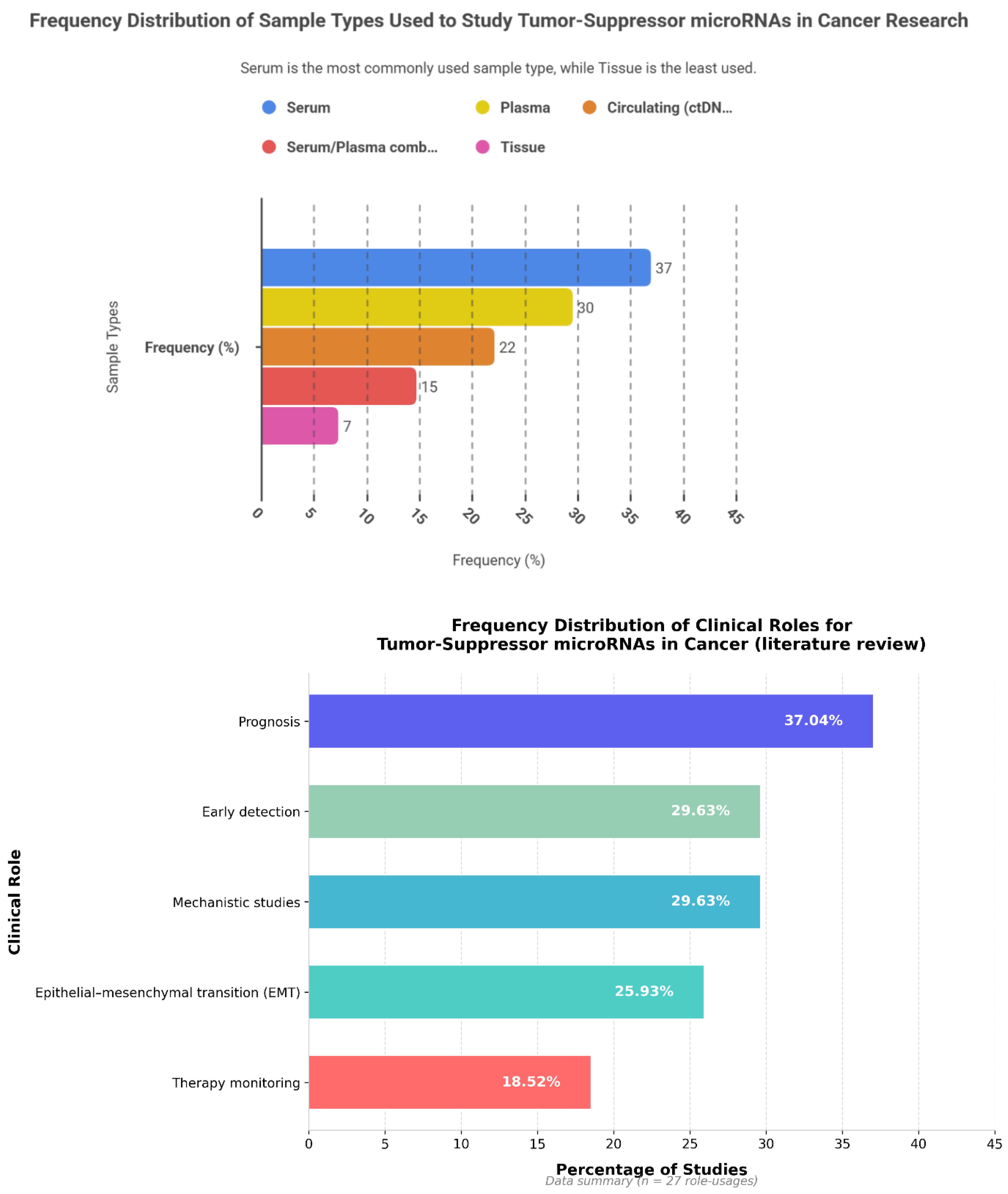

Among 27 reported events, miR-34a (8; 29.63%), miR-126 (6; 22.22%), and miR-124 (5; 18.52%) emerged as the most frequently investigated tumor-suppressive microRNAs. miR-145 and the miR-200 family were each reported in four studies (14.81%), whereas miR-15a/16, miR-205, miR-210, miR-21, miR-31, and miR-17-5p were each identified in a single event (3.70%). Collectively, the three leading miRNAs accounted for 70.37% of all observations, and inclusion of miR-145 and miR-200 extended coverage to almost the entire dataset—although grouping at the family level may marginally overstate diversity. In terms of tumor context, studies addressing multiple cancer types comprised 8 of 27 events (29.63%), followed by breast cancer (5; 18.52%). NSCLC, prostate, and colorectal cancers were equally represented (each 4; 14.81%), with ovarian cancer contributing 3 events (11.11%). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), glioma, and gastric cancer each accounted for 2 events (7.41%). Collectively, the first two categories represented nearly half of all reports, whereas the three major adult cancers—NSCLC, prostate, and colorectal—together comprised 44.44%. In contrast, highly lethal but less investigated malignancies such as PDAC, glioma, and gastric cancer remained under-represented within the available evidence.

Analysis of 27 sample matrices showed that serum was the most frequently employed (10; 37.04%), followed by plasma (8; 29.63%), circulating components or ctDNA (6; 22.22%), combined serum–plasma specimens (4; 14.81%), and tissue (2; 7.41%). The pronounced reliance on blood-derived materials (92.59%) highlights the translational promise of liquid-biopsy platforms, with a modest preference for serum over plasma (approximately 7.4%).

In terms of functional applications, prognostic studies predominated (10; 37.04%), while early diagnostic and mechanistic investigations each accounted for eight (29.63%). Seven studies (25.93%) addressed epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), and five (18.52%) focused on treatment monitoring. This emphasis on prognostic assessment suggests greater maturity of evidence for risk stratification, whereas the limited number of treatment-response analyses underscores the need for longitudinal, serial-sampling designs.

Wilson confidence intervals for proportions ranging from 7% to 30% were wide (roughly 4–48%), indicating limited statistical distinction among mid-ranked categories. The analytical unit represented a “study event,” whereby a single study could contribute multiple roles or miRNAs. The absence of reported effect-size metrics (AUC, HR, OR) and quality indicators constrains robust clinical interpretation and generalizability. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) for oncomiRs, based on named categories, was approximately 0.52—indicating a moderate-to-high concentration driven by the dominance of miR-21 and miR-155. Tumor-suppressive miRNAs also exhibited a right-skewed distribution centred on miR-34a, miR-126, and miR-124. Although the number of distinct miRNAs was greater among tumor suppressors (7–9 for oncomiRs vs broader range for suppressors), most event weights remained concentrated in a few core molecules.

Several methodological factors warrant consideration. Clinical and analytical heterogeneity—including differences in cancer type, sample matrix (serum, plasma, tissue, or urine), and quantification platform—may confound frequency-based comparisons. Furthermore, the analytical unit used in this review represents “study events,” which do not necessarily correspond to independent studies or patient cohorts, as multiple roles or miRNAs may originate from a single investigation. The absence of reported effect measures, such as AUC, hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals, and formal quality assessments, further restricts clinical generalizability. In addition, wide and overlapping confidence intervals limit the ability to discriminate statistically among intermediate rankings. Many actionable steps can strengthen future research in this field. First, studies should consistently report quantitative effect sizes, including the area under the curve (AUC) for diagnostic applications, hazard ratios (HRs) for prognostic analyses, and odds ratios (ORs) for EMT-related evaluations, each accompanied by 95% confidence intervals. Where possible, meta-analytic synthesis should be undertaken to integrate effect estimates across studies. Second, stratification by cancer type and sample matrix is essential to assess whether the observed predominance of miR-21/155 and miR-34a/126 remains consistent across tumor and specimen contexts. Sensitivity analyses should also be performed by excluding multi-miRNA panels or studies encompassing multiple cancer types and by analyzing individual members of the miR-200 family separately to test the robustness of ranking patterns. In addition, weighting evidence by study size and methodological quality would help reduce popularity bias and enhance interpretability. Finally, pre-analytical procedures should be standardized through harmonized serum and plasma processing, control of pre-analytical variables, and cross-platform validation, complemented by prospective trial designs for dynamic treatment monitoring.

The current body of literature on cancer-associated miRNAs portrays a coherent yet concentrated landscape. Among oncomiRs, miR-21 and miR-155 remain central, with prominent roles in early detection and prognosis; miR-10b appears as a secondary but biologically meaningful link to metastasis. On the tumor-suppressive side, miR-34a, miR-126, and miR-124 form the principal axis of reporting, primarily in prognostic studies. The prevalence of liquid biopsy approaches strengthens translational prospects, although subtle distinctions between serum and plasma and persisting platform heterogeneity call for standardization. Methodological constraints—event-based analytic units, lack of effect-size metrics, and overlapping confidence intervals—dictate that findings be interpreted descriptively and with caution. A forward trajectory demands transition from frequency tabulation to effect-size quantification and metacentric prospective validation, enabling miRNAs to evolve from “promising indicators” into clinically credible diagnostic and prognostic tools.

Figure 4 shows the frequency patterns of tumor-suppressive miRNAs, along with their cancer-type distribution, sample type, and clinical roles across the analysed studies.

7. Discussion

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) constitute a class of small, non-coding RNAs that exert broad regulatory control over gene expression through post-transcriptional mechanisms, positioning them as critical modulators in cancer pathogenesis. This review consolidates current evidence underscoring their dualistic roles: oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs), which facilitate tumor initiation and progression, and tumor-suppressor miRNAs, which inhibit malignant transformation. OncomiRs such as miR-21, miR-155, miR-10b, and the miR-17–92 cluster are frequently overexpressed across diverse cancers, promoting tumor growth by silencing key suppressors including PTEN, PDCD4, SHIP1, SOCS1, HOXD10, and p21 (Chan et al., 2005; O’Connell et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2007; He et al., 2005). In contrast, tumor-suppressor miRNAs—such as miR-34a, miR-126, miR-145, miR-124, miR-15a/16-1, and the miR-200 family—are often downregulated, resulting in persistent activation of oncogenic pathways involving MYC, MET, BCL2, VEGF-A, and ZEB1/2 (Chang et al., 2007; Cimmino et al., 2005; Sachdeva et al., 2009; Meister & Schmidt, 2010; Gregory et al., 2008). This reciprocal functionality reflects the intricate regulatory networks of miRNAs, wherein dysregulation mirrors genetic, epigenetic, and micro environmental perturbations (Calin & Croce, 2006; Esquela-Kerscher & Slack, 2006; Garzon et al., 2009).

The findings presented here are consistent with published data, demonstrating disease-specific and stage-dependent expression signatures that correlate with clinical outcomes. Elevated circulating miR-21 has been consistently reported in breast, lung, and glioblastoma, often detectable months before radiographic or clinical diagnosis, underscoring its value in early tumor detection (Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Diansyah et al., 2021). Likewise, miR-155 upregulation in lymphomas and breast cancer supports immune evasion and therapeutic resistance, with expression levels declining following successful treatment (Li et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020; Lawrie et al., 2008). In contrast, tumor-suppressor miRNAs such as miR-34a are markedly reduced in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and colorectal cancer, correlating with advanced disease stage and poor survival outcomes (Li et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2017). Similarly, downregulation of the anti-angiogenic miR-126 has been associated with increased metastatic potential in colorectal and breast tumors (Liu et al., 2021; Sasahira et al., 2012; Lou et al., 2017). Frequency analysis across studies highlights a concentration of research on specific miRNAs—miR-21 and miR-155 dominate among oncomiRs (72.73% of reports), whereas miR-34a, miR-126, and miR-124 account for 70.37% of tumor-suppressor mentions—reflecting both their biological significance and preferential investigative focus (Otmani et al., 2022; Frixa et al., 2015).

Mechanistically, miRNAs influence multiple hallmarks of cancer by fine-tuning key pathways governing proliferation, apoptosis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, immune escape, and metastasis. OncomiRs such as miR-21 enhance proliferation and survival through inhibition of PTEN and PDCD4, thereby activating PI3K–AKT and NF-κB signalling and conferring apoptosis resistance (Chan et al., 2005). miR-155 promotes immune evasion by targeting SHIP1 and SOCS1, generating an inflammatory microenvironment favourable to tumor progression (O’Connell et al., 2010). miR-10b facilitates EMT and metastasis via HOXD10 suppression, leading to RhoC and MMP derepression and enhanced invasive potential (Ma et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2015). The miR-17–92 cluster stimulates proliferation by downregulating PTEN and E2F1, a mechanism prevalent in neuroblastomas (He et al., 2005). Conversely, tumor-suppressor miRNAs exert counterregulatory effects: miR-34a, a canonical p53 target, induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest via repression of BCL2, MYC, and MET, and it curtails EMT through inhibition of ZEB1/2 and SNAIL (Chang et al., 2007; He et al., 2007; Cole et al., 2008). miR-126 limits angiogenesis by targeting VEGF-A and PI3K signalling, thereby restraining vascularisation and metastatic dissemination (Meister & Schmidt, 2010; Sasahira et al., 2012; Lou et al., 2017). The miR-200 family preserves epithelial identity through ZEB1/2 regulation, countering EMT and metastatic transition (Gregory et al., 2008; Korpal et al., 2018). Other suppressors, including miR-145 and miR-124, inhibit proliferation and invasion by targeting c-MYC, FSCN1, ROCK1, and AKT2 (Sachdeva et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2014). Crucially, exosomal transfer of these miRNAs mediates systemic communication, priming pre-metastatic niches and amplifying tumor–host crosstalk (Kalluri & LeBleu, 2020).

The diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic-monitoring value of miRNAs arises from their remarkable stability in blood and other body fluids, supporting their use in liquid biopsy strategies. Circulating miR-21 and miR-155 show high sensitivity for early detection among high-risk populations, with detectable upregulation preceding radiological evidence in breast cancer and NSCLC (Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2013). Prognostically, high miR-21 levels consistently predict reduced overall survival in lung and gastric cancers (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022), whereas diminished miR-34a expression indicates greater risk of metastasis and treatment resistance in PDAC and NSCLC (Hassanein et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2017). Dynamic monitoring further highlights their potential: for example, declining serum miR-155 concentrations after therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma reflect treatment response and remission status (Li et al., 2019; Koumpis et al., 2024). Combinatorial panels integrating both oncomiRs and tumor-suppressor miRNAs improve specificity and predictive accuracy, as illustrated by the miR-10b/miR-200 axis in assessing metastatic risk in breast cancer (Ma, 2010; Song et al., 2021).

Despite sustained progress, substantial obstacles hinder clinical translation. Chief among these is context-dependent behavior: some miRNAs, notably miR-125b and miR-126, exhibit dual oncogenic or suppressive functions depending on tissue origin, tumor stage, or microenvironmental context (Le et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2022). Technical heterogeneity further complicates comparison across studies—variations in pre-analytical factors such as sample collection, storage, and RNA isolation markedly affect quantification, as do methodological differences between qRT-PCR, microarray, and next-generation sequencing platforms and their respective normalisation strategies (Schwarzenbach et al., 2014). Inconsistent clinical endpoints, small and single-centre cohorts, and publication bias favouring positive findings continue to undermine reproducibility and meta-analytic synthesis (Parrella et al., 2014). The narrative framework adopted in this review, dictated by such heterogeneity, was therefore necessitated by data inconsistency but precludes formal quantitative integration.

Clinically, liquid biopsy applications are most advanced in non-invasive detection. Exosomal miRNAs such as miR-10b display marked specificity for early metastatic disease (Sheedy & Medarova, 2018; Cho et al., 2020). Translational advances extend to experimental therapeutics, including nanoparticle-based delivery of miRNA mimics or inhibitors, with preclinical studies demonstrating restoration of miR-34a activity and suppression of miR-21 oncogenicity (Bautista-Sánchez et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2021). However, these strategies raise ethical concerns due to the potential for off-target gene modulation, reinforcing the need for comprehensive toxicological assessment and controlled clinical trials. Regulatory challenges remain substantial, particularly regarding assay standardisation, reproducibility, and validation criteria for approvals by agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration. Moreover, equitable access must be addressed: implementation of miRNA-based diagnostics or therapeutics in low-resource settings requires affordable technology and infrastructural capacity to avert exacerbating existing healthcare disparities. Ultimately, realizing the full clinical promise of miRNAs depends upon methodological standardisation and rigorous validation. Harmonization of pre-analytical protocols, reference materials, and analytical pipelines is essential to ensure reproducible and comparable results. Large-scale, prospective, multicenter studies with prespecified endpoints will be required to delineate clinically actionable thresholds and confirm predictive efficacy. Integration of miRNA profiling with multi-omics approaches—encompassing genomics, proteomics, and radiomics—offers a path toward precision oncology, enabling multidimensional patient stratification and dynamic treatment surveillance. Collectively, these advances can transform miRNAs from powerful research tools into robust clinical instruments for early detection, prognosis refinement, metastasis risk assessment, and personalized therapeutic monitoring.

8. Limitations

This review integrates a wide range of evidence on the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) as cancer biomarkers; however, several limitations in both the primary studies and our methodological approach merit consideration. Many original studies are constrained by small sample sizes and single-center designs, which restrict generalizability and reduce statistical power. For example, several investigations of miR-21 and miR-34a involve cohorts of fewer than 100 patients, potentially inflating effect estimates through selection bias (Wang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Considerable methodological heterogeneity also exists across studies, including differences in assay platforms (e.g., qRT-PCR versus next-generation sequencing), normalization procedures, and pre-analytical handling, all of which introduce variability into miRNA quantification (Schwarzenbach et al., 2014). Moreover, inconsistent clinical endpoints—such as varying definitions of progression-free survival or metastasis—complicate cross-study comparisons. Some analyses further lack standardized effect-size metrics, such as hazard ratios or area under the curve values (Parrella et al., 2014). Evidence of publication bias towards positive results is apparent, with null findings frequently underreported. The context-dependent functions of miRNAs (e.g., the dual roles of miR-126) may also be insufficiently captured by cross-sectional designs (Le et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2022). Additionally, restricting inclusion to English-language studies introduces potential language bias, possibly excluding relevant data from non-English sources.

In terms of methodology, this review adopted a narrative thematic synthesis, which suits heterogeneous data but inherently lacks the objectivity of a quantitative meta-analysis. This approach may therefore introduce subjective interpretation. The search strategy, covering studies published between 1993 and June 2025 across PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science, might have excluded grey literature or recent publications beyond the cut-off date. Reported frequency patterns were based on “study events” rather than independent cohorts, risking the overrepresentation of multi-miRNA studies. Although qualitative assessments addressed potential sources of bias, formal risk-of-bias tools were not systematically applied, and issues such as absence of external validation cohorts were frequently noted. Lastly, the focus on human studies with translational relevance may underrepresent valuable preclinical findings lacking direct clinical extrapolation.

9. Future Directions / Implications

Translating miRNAs from promising research biomarkers into clinically applicable tools demands a structured roadmap centered on standardization, validation, and integration. Standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis are essential. Analogous to existing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) guidelines, such frameworks should define uniform pre-analytical conditions, reference materials, and validated analytical platforms to minimize inter-study variability (Schwarzenbach et al., 2014). Large-scale, multicenter, prospective cohorts encompassing diverse patient populations and cancer types are needed to confirm diagnostic and prognostic performance. Serial sampling within these studies could further enable dynamic monitoring of treatment response—for example, tracking miR-155 fluctuations in DLBCL (Li et al., 2019). Integration of miRNA profiling with multi-omics data—including genomic, proteomic, and epigenomic layers—through advanced platforms such as single-cell sequencing could provide more comprehensive and precise disease signatures. A notable example is the combined use of miR-34a expression with p53 status to refine risk stratification in NSCLC (Cole et al., 2008; Hassanein et al., 2021). Machine learning algorithms also hold transformative potential, as they can analyze complex miRNA panels to predict outcomes with superior accuracy. Models trained on datasets involving miR-21 or miR-126 could enhance early cancer detection through pattern recognition in liquid biopsy data (Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021).

For therapeutic applications, safe and effective modulation of miRNAs—using mimics for suppressors such as miR-34a or antagomirs for oncomiRs like miR-21—will require advanced delivery platforms, including nanoparticles or engineered exosomes, to ensure target specificity and minimize off-target interactions (Bautista-Sánchez et al., 2020; Kalluri & LeBleu, 2020; Pan et al., 2021). Preclinical studies should prioritize in vivo validation, paving the way for clinical translation through phase I/II trials, as exemplified by miR-34a mimics in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Beyond technical advances, equitable access to cost-effective assays and clear regulatory guidance—such as FDA companion diagnostic frameworks—will be crucial to clinical implementation. Collectively, these efforts could firmly establish miRNAs as integral elements of precision oncology, bridging molecular insights with improved patient outcomes through non-invasive, personalized approaches.

10. Conclusion

This review highlights the dualistic nature of miRNAs as both oncogenic drivers (oncomiRs) and tumor suppressors, integrating their diverse functions across cancer hallmarks such as proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and metastasis. Circulating miRNAs exhibit notable stability, supporting their promise as viable liquid biopsy biomarkers. Among them, miR-21 and miR-34a stand out for their diagnostic and prognostic significance across multiple malignancies (Wang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Nonetheless, barriers remain—chiefly context dependence, methodological heterogeneity, and limited validation—that continue to challenge routine clinical adoption (Schwarzenbach et al., 2014). Moving forward, standardized analytical procedures, multi-omics integration, and targeted therapeutic development hold the key to unlocking miRNAs’ full potential. Addressing these gaps could ultimately transform cancer management, enabling minimally invasive, precision-based interventions to improve patient survival and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors offer heartfelt gratitude to all scientists who tirelessly illuminate the biology of cancer, bringing the hope of earlier diagnosis ever closer. In a shared wish, both authors hope that the advances distilled in this work may, in some small way, help lighten the burden of cancer for patients and their families.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Bautista-Sánchez, D.; Arriaga-Canon, C.; Pedroza-Torres, A.; De La Rosa-Velázquez, I.A.; González-Barrios, R.; Contreras-Espinosa, L.; Montiel-Manríquez, R.; Castro-Hernández, C.; Fragoso-Ontiveros, V.; Álvarez-Gómez, R.M. The promising role of miR-21 as a cancer biomarker and its importance in RNA-based therapeutics. Molecular therapy Nucleic acids 2020, 20, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billi, M.; De Marinis, E.; Gentile, M.; Nervi, C.; Grignani, F. Nuclear miRNAs: gene regulation activities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(11), 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, G.A.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nature Reviews Cancer 2006, 6(11), 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.A.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Kosik, K.S. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer research 2005, 65(14), 6029–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.-C.; Wentzel, E.A.; Kent, O.A.; Ramachandran, K.; Mullendore, M.; Lee, K.H.; Feldmann, G.; Yamakuchi, M.; Ferlito, M.; Lowenstein, C.J. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Molecular cell 2007, 26(5), 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Mao, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Lin, Y.; Lv, Y. Serum exosomal miR-34a as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and prognostic of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Cancer 2022, 13(5), 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, X. Application of third-generation sequencing in cancer research. Medical Review 2021, 1(2), 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Eun, J.W.; Baek, G.O.; Seo, C.W.; Ahn, H.R.; Kim, S.S.; Cho, S.W.; Cheong, J.Y. Serum exosomal microRNA, miR-10b-5p, as a potential diagnostic biomarker for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9(1), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Calin, G.A.; Fabbri, M.; Iorio, M.V.; Ferracin, M.; Shimizu, M.; Wojcik, S.E.; Aqeilan, R.I.; Zupo, S.; Dono, M. miR-155 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102(39), 13944–13949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, K.A.; Attiyeh, E.F.; Mosse, Y.P.; Laquaglia, M.J.; Diskin, S.J.; Brodeur, G.M.; Maris, J.M. A functional screen identifies miR-34a as a candidate neuroblastoma tumor suppressor gene. Molecular cancer research 2008, 6(5), 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diansyah, M.N.; Prayogo, A.A.; Sedana, M.P.; Savitri, M.; Romadhon, P.Z.; Amrita, P.N.A.; Wijaya, A.Y.; Hendrata, W.M.; Bintoro, U.Y. Early detection breast cancer: role of circulating plasma miRNA-21 expression as apotential screening biomarker. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences 2021, 51(2), 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwedar, F.I.; Shams-Eldin, R.S.; Nayer Mohamed, S.; Mohammed, A.F.; Gomaa, S.H. Potential value of circulatory microRNA10b gene expression and its target E-cadherin as a prognostic and metastatic prediction marker for breast cancer. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis 2021, 35(8), e23887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquela-Kerscher, A.; Slack, F.J. Oncomirs—microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2006, 6(4), 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frixa, T.; Donzelli, S.; Blandino, G. Oncogenic MicroRNAs: key players in malignant transformation. Cancers 2015, 7(4), 2466–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, R.; Calin, G.A.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annual review of medicine 2009, 60(1), 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.A.; Bert, A.G.; Paterson, E.L.; Barry, S.C.; Tsykin, A.; Farshid, G.; Vadas, M.A.; Khew-Goodall, Y.; Goodall, G.J. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nature cell biology 2008, 10(5), 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, A.M.; Nuzzo, S.; Condorelli, G.; Salvatore, M.; Incoronato, M. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of MiR-155 in breast cancer: a systematic review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21(16), 5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, S.S.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Abdel-Mawgood, A.L. Cell behavior of non-small cell lung cancer is at EGFR and microRNAs hands. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(22), 12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Hannon, G.J. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nature reviews genetics 2004, 5(7), 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; He, X.; Lim, L.P.; De Stanchina, E.; Xuan, Z.; Liang, Y.; Xue, W.; Zender, L.; Magnus, J.; Ridzon, D. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature 2007, 447(7148), 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; He, X.; Lowe, S.W.; Hannon, G.J. microRNAs join the p53 network—another piece in the tumour-suppression puzzle. Nature Reviews Cancer 2007, 7(11), 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Thomson, J.M.; Hemann, M.T.; Hernando-Monge, E.; Mu, D.; Goodson, S.; Powers, S.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Lowe, S.W.; Hannon, G.J. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature 2005, 435(7043), 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkinen, L. Computational analysis of small non-coding RNAs in model systems Itä-Suomen yliopisto. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.-B.; Li, Q.-L.; Hu, J.-F.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, J.-P.; Deng, L. miR-124 inhibits growth and invasion of gastric cancer by targeting ROCK1. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2014, 15(16), 6543–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, D.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Zhan, T.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xi, J.; Yan, L.; Gu, J. MicroRNA-181a promotes tumor growth and liver metastasis in colorectal cancer by targeting the tumor suppressor WIF-1. Molecular cancer 2014, 13(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367(6478), eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumpis, E.; Georgoulis, V.; Papathanasiou, K.; Papoudou-Bai, A.; Kanavaros, P.; Kolettas, E.; Hatzimichael, E. The Role of microRNA-155 as a Biomarker in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Biomedicines 2024, 12(12), 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, C.H.; Gal, S.; Dunlop, H.M.; Pushkaran, B.; Liggins, A.P.; Pulford, K.; Banham, A.H.; Pezzella, F.; Boultwood, J.; Wainscoat, J.S. Detection of elevated levels of tumour-associated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. British journal of haematology 2008, 141(5), 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.; Teh, C.; Shyh-Chang, N.; Xie, H.; Zhou, B.; Korzh, V.; Lodish, H.F.; Lim, B. MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes & development 2009, 23(7), 862–876. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75(5), 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, X. MicroRNA-126 (MiR-126): key roles in related diseases. Journal of physiology and biochemistry 2024, 80(2), 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhong, G.; Chen, D.; Shen, J.; Bao, C.; Xu, L.; Pan, J.; Cheng, J. MicroRNAs in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. Oncotarget 2017, 8(70), 115787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wen, W. MicroRNA in prostate cancer: from biogenesis to applicative potential. BMC urology 2024, 24(1), 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. Role of miR-10b in breast cancer metastasis. Breast cancer research 2010, 12(5), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature 2007, 449(7163), 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, A.R.; Hooper, S.B.; Zahra, V.A.; Sozo, F.; Lo, C.Y.; Cole, T.J.; Doran, T.; Wallace, M.J. The oncogene Trop2 regulates fetal lung cell proliferation. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2011, 301(4), L478–L489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, J.; Schmidt, M.H. miR-126 and miR-126: new players in cancer. The Scientific World Journal 2010, 10(1), 2090–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metanat, Y.; Sviridova, M.; Al-Nuaimi, B.N.; Janbazi, F.; Jalali, M.; Ghalamkarpour, N.; Khodabandehloo, E.; Ahmadi, E. The role of non-coding RNAs in the regulation of cell death pathways in melanoma. Discover Oncology 2025, 16(1), 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogilyansky, E.; Rigoutsos, I. The miR-17/92 cluster: a comprehensive update on its genomics, genetics, functions and increasingly important and numerous roles in health and disease. Cell Death & Differentiation 2013, 20(12), 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.K.; Li, R.; Shin, V.Y.; Jin, H.C.; Leung, C.P.; Ma, E.S.; Pang, R.; Chua, D.; Chu, K.-M.; Law, W. Circulating microRNAs as specific biomarkers for breast cancer detection. PloS one 2013, 8(1), e53141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'connell, R.M.; Rao, D.S.; Chaudhuri, A.A.; Baltimore, D. Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 2010, 10(2), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otmani, K.; Rouas, R.; Lewalle, P. OncomiRs as noncoding RNAs having functions in cancer: Their role in immune suppression and clinical implications. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 913951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, K.; Tao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, N.; Liu, J.; Go, V.L.W.; Guo, J.; Gao, G. MicroRNA-34a alleviates gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer by repression of cancer stem cell renewal. Pancreas 2021, 50(9), 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrella, P.; Barbano, R.; Pasculli, B.; Fontana, A.; Copetti, M.; Valori, V.M.; Poeta, M.L.; Perrone, G.; Righi, D.; Castelvetere, M. Evaluation of microRNA-10b prognostic significance in a prospective cohort of breast cancer patients. Molecular cancer 2014, 13(1), 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M.; Zhu, S.; Wu, F.; Wu, H.; Walia, V.; Kumar, S.; Elble, R.; Watabe, K.; Mo, Y.-Y. p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106(9), 3207–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasahira, T.; Kurihara, M.; Bhawal, U.; Ueda, N.; Shimomoto, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kirita, T.; Kuniyasu, H. Downregulation of miR-126 induces angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis by activation of VEGF-A in oral cancer. British journal of cancer 2012, 107(4), 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, H.; Nishida, N.; Calin, G.A.; Pantel, K. Clinical relevance of circulating cell-free microRNAs in cancer. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2014, 11(3), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheedy, P.; Medarova, Z. The fundamental role of miR-10b in metastatic cancer. American journal of cancer research 2018, 8(9), 1674. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, S. Posttranscriptional upregulation by microRNAs. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 2012, 3(3), 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Diao, M.; Tan, S.; Huang, S.; Cheng, Y.; You, T. MicroRNA-21 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bioscience Reports 2022, 42(5), BSR20211653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Li, L.; Ye, Z.-Y.; Zhao, Z.-S.; Yan, Z.-L. MicroRNA-10b promotes migration and invasion through Hoxd10 in human gastric cancer. World journal of surgical oncology 2015, 13(1), 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Gao, W.; Zhu, C.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Mei, Z.; Cheng, T.; Shu, Y.-Q. Identification of plasma microRNA-21 as a biomarker for early detection and chemosensitivity of non–small cell lung cancer. Chinese journal of cancer 2011, 30(6), 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hong, Q.; Lu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Nie, Z.; He, B. The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-155 in cancers: an updated meta-analysis. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy 2023, 27(3), 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qin, J.; Ye, B.; Xu, C.; Yu, G. Overexpression of miR-125a-5p inhibits hepatocyte proliferation through the STAT3 regulation in vivo and in vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(15), 8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, D.; Wang, J. Noncoding RNAs: master regulator of fibroblast to myofibroblast transition in fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(2), 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]