1. Introduction

Precise and efficient pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) splicing is essential for eukaryotic gene expression, ensuring that introns are accurately excised and exons correctly joined to form mature mRNA (Pan et al., 2008; Sakharkar et al., 2004). This process is catalysed by the spliceosome, a dynamic ribonucleoprotein complex composed of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs); U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6, together with more than 300 auxiliary splicing factors (Pokorná et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2017). The spliceosome, its role in alternative splicing and human disease have been under investigation since the 1900’s and are covered frequently in recent reviews (Deutsch et al., 2025; Pasteris et al., 2025; Soares et al., 2025). It has long been understood that among the snRNPs, U1 plays a pivotal role in the early stages of spliceosome assembly by recognising and base-pairing at the exon–intron boundary via the conserved ‘GU’ 5′ splice-site motif (Furlong, 2018; Lerner et al., 1980). This recognition event defines the correct site for intron removal and is critical for maintaining the integrity of coding sequences.

Mutations that disrupt canonical ‘GU’ splice-site motifs or interfere with the U1 snRNA–5′ splice-site interaction are a major cause of inherited human diseases. More than 15% of all disease-associated mutations are predicted to affect RNA splicing, often resulting in exon skipping, intron retention or the generation of aberrant transcripts (Krawczak et al., 1992, 2007). Notably, single-nucleotide substitutions within the 5′ splice-site of the β-globin gene (HBB) pre-mRNA can impair or abolish U1 snRNP binding, which leads to abnormal pre-mRNA processing and a deficiency of functional β-globin chains, the hallmark of β-thalassaemia (Treisman et al., 1983). Therapies for this dysfunctional splice sites in β-thalassaemia are still being developed recently (Lu et al., 2024), so there is still a gap in knowledge to find the optimal therapeutic method. Similar defective splice-site recognition mutations also contribute to the pathogenesis of diverse diseases (Scotti & Swanson, 2016) including neurodegenerative disorders (Deutsch et al., 2025; Nava et al., 2025; Nik & Bowman, 2019), muscular dystrophies (Ottesen et al., 2024), and cancers (Bradley & Anczuków, 2023; Lv et al., 2025; Urbanski et al., 2018). So a novel approach to treating defective 5’ splice site recognition could possibly be applied extensively.

Therapeutic correction of splicing defects has traditionally relied on antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) which are designed to modulate splice-site usage or exon inclusion; a topic that has been widely reviewed (Chen et al., 2024; Havens & Hastings, 2016; Lv et al., 2025; Wai et al., 2024). Some ASO-based therapies have proven clinically successful, such as nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy (Cebulla et al., 2025; Finkel et al., 2017), and there remains much hope for future ASO theraputics (Wijnant et al., 2025). However, issues remain, including dosage accuracy, toxicity (Sabrina Haque et al., 2024), and targeted cellular uptake (Gagliardi & Ashizawa, 2021; Raguraman et al., 2021). Therefore, an optimised delivery mechanism is essential to mitigate most of these problems (Hammond et al., 2021; Lauffer et al., 2024). Furthermore, ASOs act by steric hindrance, correcting downstream splicing outcomes but do not fix the underlying genetic defect or restore the natural spliceosome-mediated recognition of splice-sites, hence they treat the symptoms but not the cause so require continuous dosing (Havens & Hastings, 2016; Lauffer et al., 2024; Qiu et al., 2022). In contrast, direct delivery of functional snRNAs offers the potential to reinstate normal splice-site pairing, thereby achieving a more physiological repair of pre-mRNA processing (Hatch et al., 2022; Zhuang & Weiner, 1986). In fact, engineered U1 snRNAs have already shown promise in preclinical settings for various diseases (Breuel et al., 2019; Fernandez Alanis et al., 2012; Peruzzo et al., 2025; Sönmezler et al., 2024); although, delivery remains technically challenging as snRNAs must reach the nucleus and integrate with the complex endogenous snRNP machinery (Gonçalves et al., 2023)

Many of these past U1-based therapeutic strategies have applied lentiviral vectors (Breuel et al., 2019; Gonçalves et al., 2023; Schmid et al., 2011), which have been constantly improved through recent years but still must be specifically engineered and produced for transduction efficiency and specificity and run the risk of oncogenicity (due to off-target effects), toxicity, and immunogenicity (due to viral origin) (Dong & Kantor, 2021; Hammond et al., 2021; Milone & O’Doherty, 2018). On the other hand, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as promising vectors for RNA delivery owing to their endogenous origin, stability in biological fluids, and intrinsic capacity to transfer functional nucleic acids (mRNAs, microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs) between cells (Kalluri & LeBleu, 2020; Théry et al., 2018; Valadi et al., 2007). EVs encompass a heterogeneous population of membrane-bound vesicles, including exosomes (30–150 nm) and microvesicles (100–1000 nm), which are released through distinct biogenesis pathways (El Andaloussi et al., 2013; Théry et al., 2018). Membrane proteins that contribute to vesicle formation and cargo selection are enriched in exosomes; like the endosomal sorting complex protein TSG101 and Tetraspanins including CD9, CD63, and CD81 (Andreu & Yanez-Mo, 2014; Théry et al., 2018). Their natural capacity for targeted intracellular delivery has stimulated interest in exploiting EVs as therapeutic carriers for RNA-based interventions (El Andaloussi et al., 2013; Goo et al., 2024; Kalluri & LeBleu, 2020; Liang et al., 2025). Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that EVs have potential to transfer functional RNA species capable of modulating gene expression, regulating translation, and altering cellular phenotypes (Alqurashi et al., 2023; Liang et al., 2025). They are typically less efficient than lentiviral vectors as their cargo is often episomal rather than integrating into the genome; but are safer, with less oncogenicity and immunogenicity (Di Ianni et al., 2025; Van Delen et al., 2024). Despite the benefits of EVs as delivery vectors and U1 snRNA for splicing restoration, the use of EVs to deliver spliceosomal components such as U1 snRNA has not been previously reported.

The U1 snRNA has a relatively small, stable, and well-defined structure, making it an ideal candidate for encapsulation and intercellular delivery (Gonçalves et al., 2023; Kondo et al., 2015). Hence, we investigated whether engineered EVs can carry U1 snRNA to recipient cells for intracellular uptake and reassembly into fully functional snRNP complexes in vitro in order to rescue defective 5′ splice site recognition in target pre-mRNA substrates. EVs were isolated from HEK293T donor cells, transfected with a U1 snRNA expression plasmid, then characterised by both nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and canonical marker-based Western blotting. EVs were then applied to HeLa cells that mimic β-thalassaemia disease as they expressed a β-globin minigene harbouring a β-thalassaemia-like 5′ splice-site mutation. Measuring the stability, dose-dependence, and RNA dependency of the observed effect revealed for the first time, that EV-delivered U1 snRNA can reconstitute splice-site recognition and partially rescue normal β-globin pre-mRNA processing in recipient cells.

We introduce a new framework for using EVs as natural carriers for spliceosomal RNAs, thereby expanding the scope of possibility for RNA-based therapeutics to include the direct restoration of pre-mRNA splicing fidelity. Beyond its proof-of-concept nature, this approach holds potential for future treatments including a broad range of genetic disorders arising from splice-site mutations and sets the stage for future development of EV-mediated snRNA delivery platforms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

HEK293T and HeLa cells were obtained from authenticated laboratory stocks and routinely confirmed to be mycoplasma-free. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. To prevent contamination of extracellular vesicle (EV) preparations with bovine-derived vesicles, FBS was pre-depleted of EVs by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 16 h at 4 °C using a Beckman Coulter Type 45 Ti rotor. All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂ and passaged using 0.05% trypsin–EDTA at 70–80% confluence. Experiments were conducted using cells at passages below 20 to ensure phenotypic stability.

2.2. Construction of β-Globin Minigene Reporters

Human β-globin minigenes encompassing exons 1–3 and their intervening introns (~2.2 kb) were amplified from human genomic DNA and cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector downstream of the CMV promoter using standard restriction–ligation cloning. The β-thalassaemia-like mutant construct was generated by introducing a G→A substitution at the +1 position of intron 2, disrupting the canonical 5′ splice-site ‘GU’ dinucleotide. Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Plasmids were propagated in DH5α E. coli and purified using the EndoFree Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. U1 snRNA Expression Construct

A human U1 snRNA transcriptional cassette, including its native promoter, coding region, and 3′ regulatory elements, was synthesised (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned into pcDNA3.1. The construct was designed to preserve the endogenous U1 secondary structure required for spliceosomal assembly. An empty pcDNA3.1 vector served as a negative control. Transient transfections into HEK293T cells were performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were used for EV isolation 48 h post-transfection.

2.4. Extracellular Vesicle Isolation

EVs were purified using differential ultracentrifugation. Conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells, then 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove debris, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min to eliminate large vesicles and apoptotic bodies. The resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 70 min at 4 °C. Pellets were washed in PBS and ultracentrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 70 min. Final EV pellets were resuspended in sterile PBS and stored at −80 °C for short-term use. All steps were performed at 4 °C.

2.5. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

EV size and concentration were measured using a NanoSight NS300 system (Malvern Instruments). EV preparations were diluted 1:100–1:500 in PBS to reach optimal particle concentrations (~1 × 10⁸ particles/mL). For each sample, five 60-second videos were acquired with identical camera settings across 3 biological replicates. Data were processed using NTA software to calculate modal diameter and particle concentration, then displayed in Microsoft Excel where T. test statistics were calculated (Supplementary data). NanoSight NS300 system settings were kept as similar between readings as possible: 24 °C, 100 shutter, 30 fps, and 80 camera sensitivity (Supplementary data).

2.6. Western Blot Analysis of EV Markers

Three biological replicates of EVs and their corresponding donor-cell lysates were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Equal protein amounts were resolved on SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against CD9, CD63, TSG101 (canonical EV markers) and calnexin (negative control marker for endoplasmic reticulum contamination). Binding was visualized using secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; GE Healthcare). Blots were quantified using ImageJ software, sample of interest relative to control analysis was calculated and plotted in Microsoft Excel (Supplementary data).

2.7. RNA Extraction from EVs

EV RNA was extracted using TRIzol LS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Glycogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as a carrier to enhance yield. RNA quantity and purity were assessed via NanoDrop spectrophotometry.

2.8. β-.Globin Minigene Transfection and EV Treatment

HeLa cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1 × 10⁵ cells per well in three biological replicates. After 24 h, cells were transfected with 500 ng of wild-type or mutant β-globin minigene plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000. Six hours post-transfection, cells were treated with U1-EVs or control EVs. EVs were added directly to the culture medium without transfection agents. Cells were harvested 48 h after EV addition.

2.9. RT–PCR Splicing Analysis

Total RNA from HeLa cells was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA synthesis was performed with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). β-Globin transcripts were amplified using primers located in exon 1 (forward) and exon 3 (reverse). PCR cycles were optimized to remain within the linear amplification range. Products were resolved on 2% agarose gels, visualized with ethidium bromide. Spliced and unspliced bands were gel-excised and sequenced for verification.

2.10. Quantitative RT–PCR

Isoform-specific qPCR assays were designed to detect either the correctly spliced transcript or the intron-retaining species. Reactions were performed with Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR system. Spliced U1 gene expression was normalized to GAPDH or U6 snRNA and then U1-containing EVs were shown relative to empty EVs. Fold changes were calculated using the 2⁻ΔΔCt method in Microsoft Excel (Supplementary data). All reactions were performed in triplicate.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments included at least two biological replicates. Data are presented as mean or median ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. One or two-tailed Welch’s t-tests were used for significance comparisons. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

3. Results

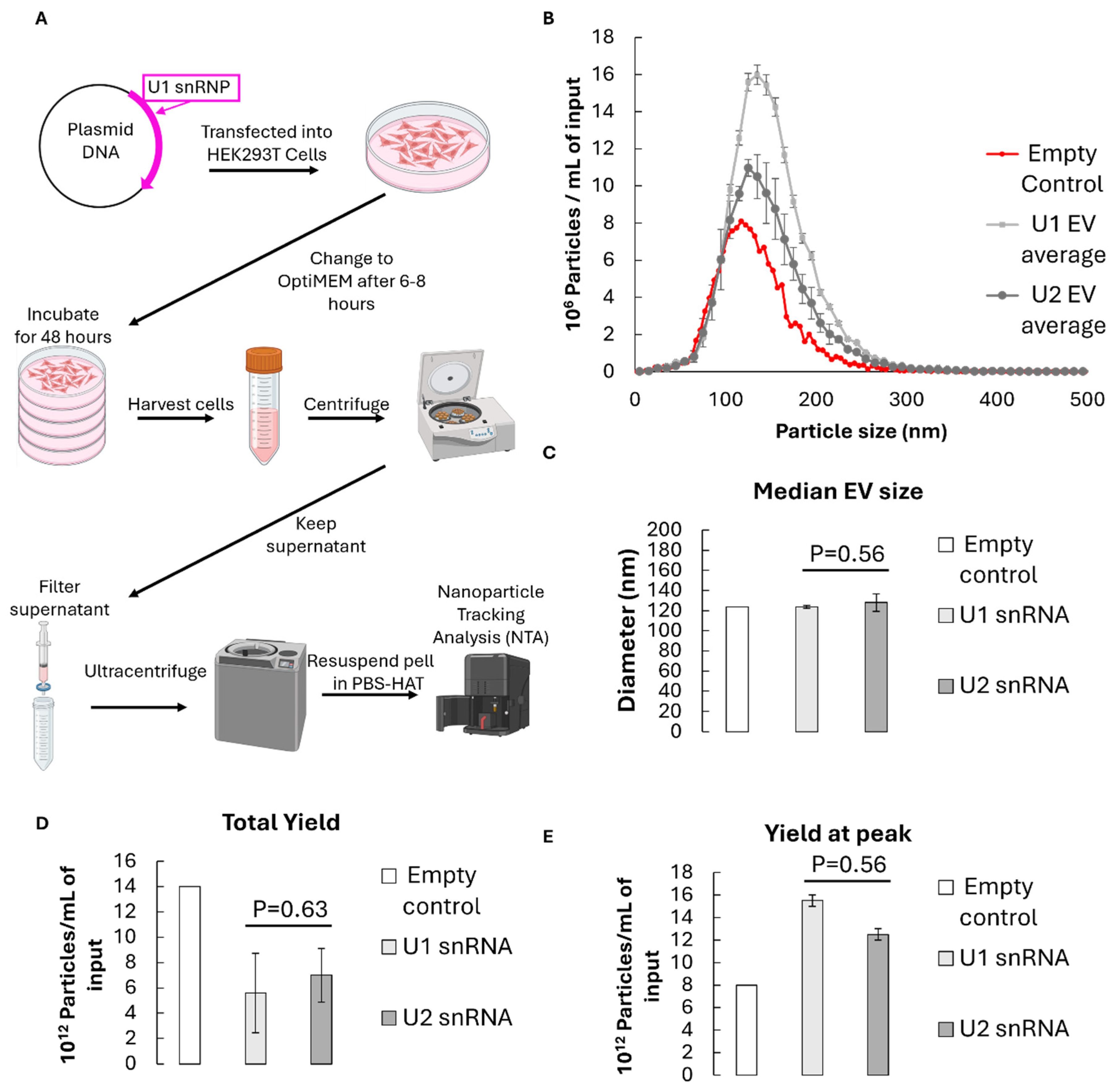

3.1. Characterisation of U1-Enriched Extracellular Vesicles

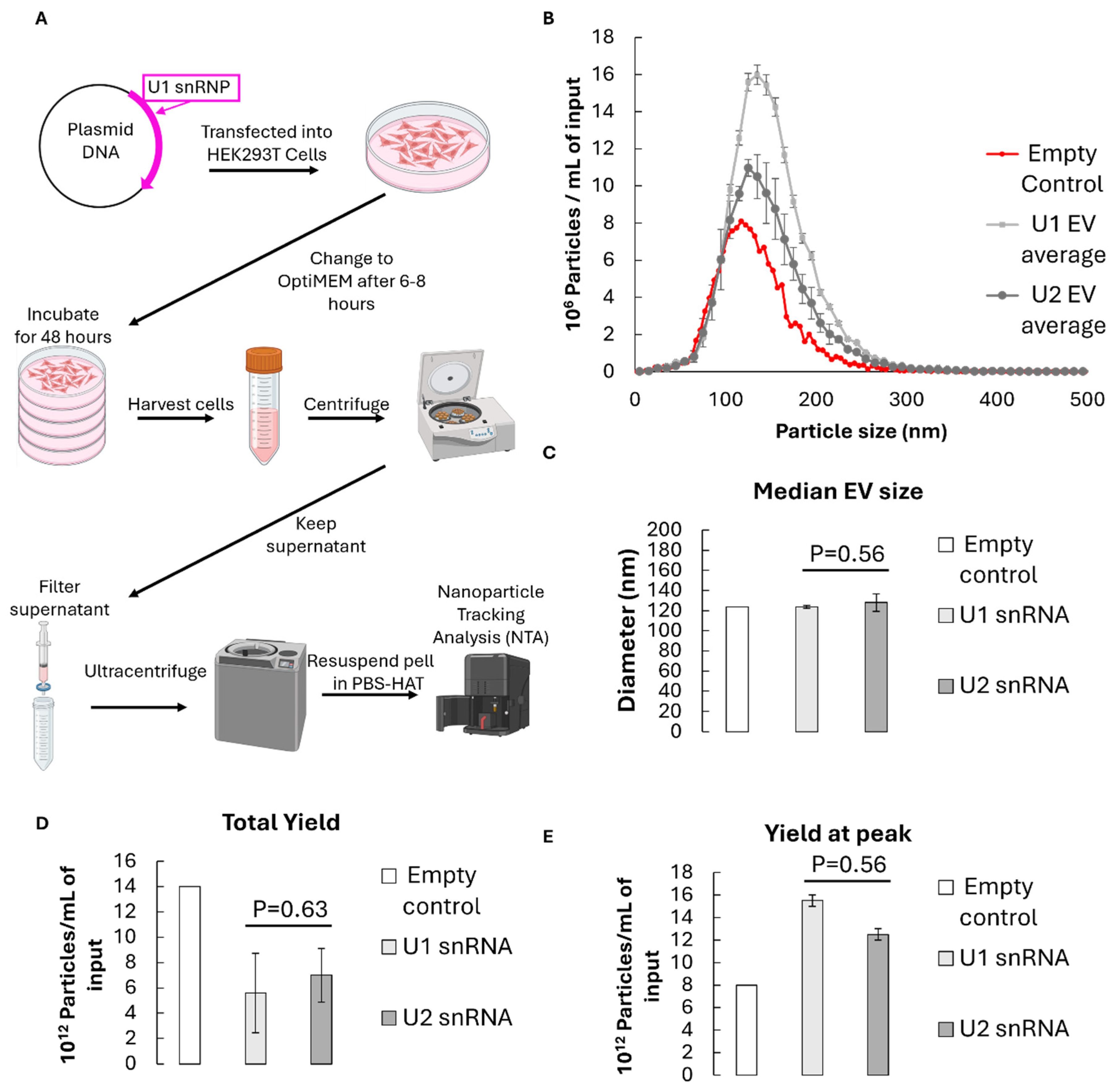

To assess whether EVs can serve as carriers for small nuclear RNA delivery, HEK293T cells were transfected with a U1 snRNA expression construct or an empty vector as a control. Cells were grown and EVs were isolated from the conditioned medium by sequential centrifugation followed by filtration and ultracentrifugation at 100,000 ×g (

Figure 1A). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) revealed a size distribution centred around 120 nm with a span of approximately 0.8 for all measurements, consistent with the expected exosomal range, suggesting consistent preparation quality and particle heterogeneity during EV extractions (

Figure 1B, Supplementary data). There was no significant difference in the size of U1 vs U2 containing EVs (p=0.56), or any substantial difference from the empty control (

Figure 1C). The total particle yield for U1-containing EVs averaged 5.6 × 1012 particles per millilitre of culture supernatant, again with no significant difference between U1 or U2 control-transfected samples (p=0.63) (

Figure 1D). Additionally, there were more total particles in the empty control EV sample, but more particles at the peak diameters for U1 and U2-containing EVs, suggesting slightly smaller but suitable and very consistent yields of snRNA-containing EVs (

Figure 1E).

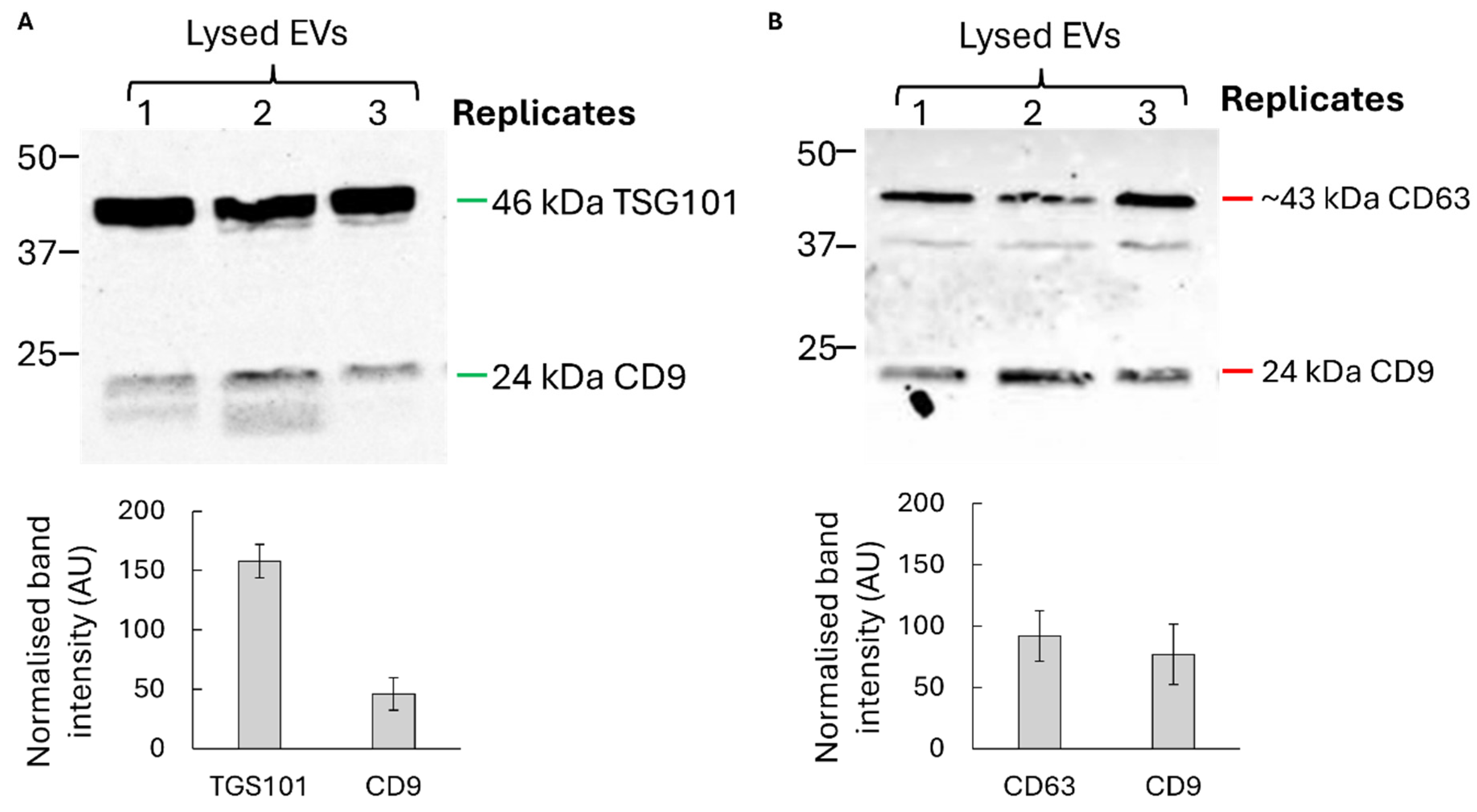

Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of canonical exosomal markers CD9, CD63, and TSG101, while cellular contaminants such as calnexin were undetectable, indicating high purity of the preparations (

Figure 2). Together, these data confirm that U1-expressing donor cells produce bona fide exosome-like vesicles suitable for downstream delivery experiments.

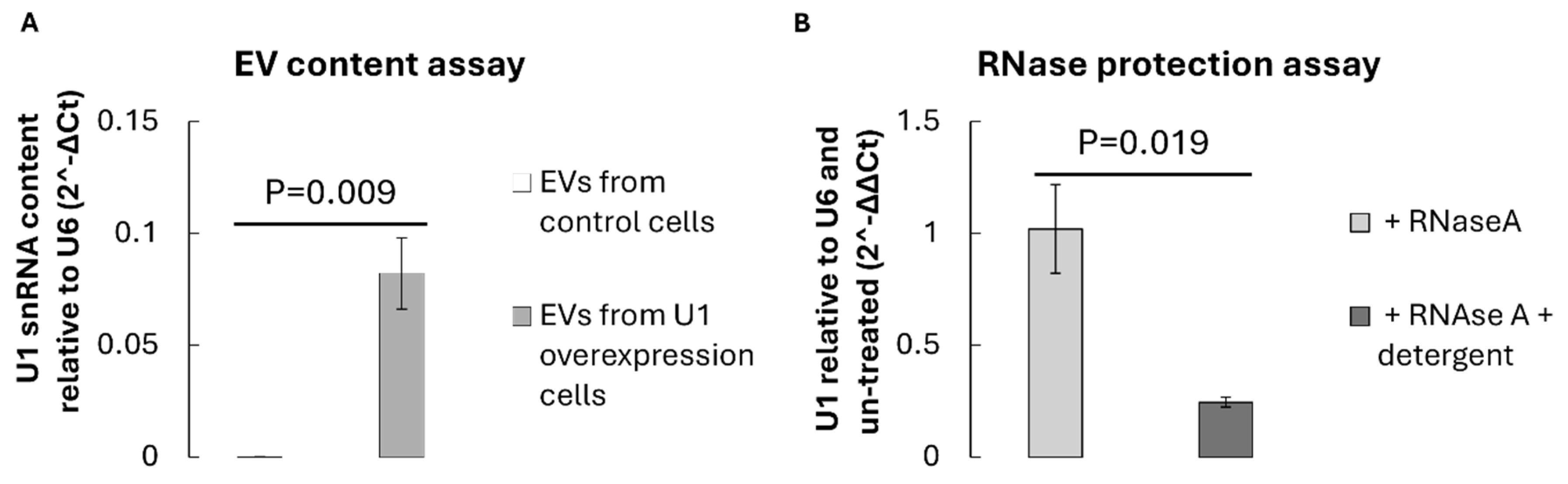

3.2. Detection of U1 snRNA Within Isolated EVs

To verify the successful loading of U1 snRNA into EVs, total RNA was extracted from an equal number of vesicles isolated from control Hek293 cells (transfected with empty pcDNA3.1) or U1-overexpression Hek293 cells (transfected with pcDNA3.1 containing the U1 snRNA transcriptional cassette). Reverse transcription followed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT–qPCR) using U1-specific primers revealed a significant enrichment of U1 transcripts within EVs from U1-overexpressing cells (p=0.009), compared to vector controls (

Figure 3A). The relative U1 content was normalised to small RNA U6, which served as an internal reference.

The presence of U1 snRNA within EVs was further validated by RNase protection assay. Treatment of intact EVs with RNase A did not reduce the detectable U1 signal, whereas detergent-disrupted vesicles exhibited substantial degradation of U1 RNA (

Figure 3B). This indicates that U1 snRNA is encapsulated within the vesicular lumen rather than externally associated with the vesicle surface. These findings collectively demonstrate that donor cell overexpression leads to efficient packaging of U1 snRNA into secreted EVs.

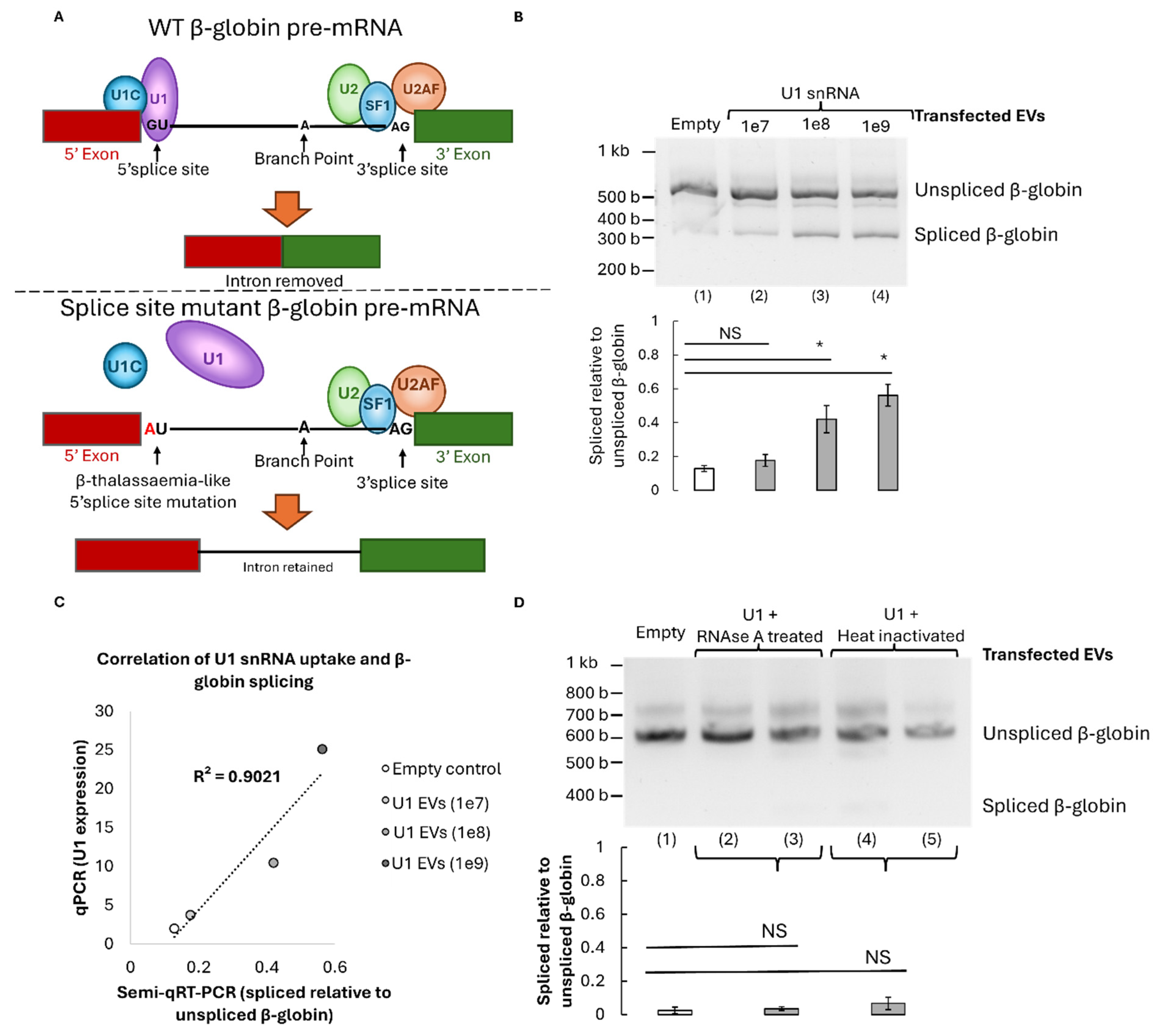

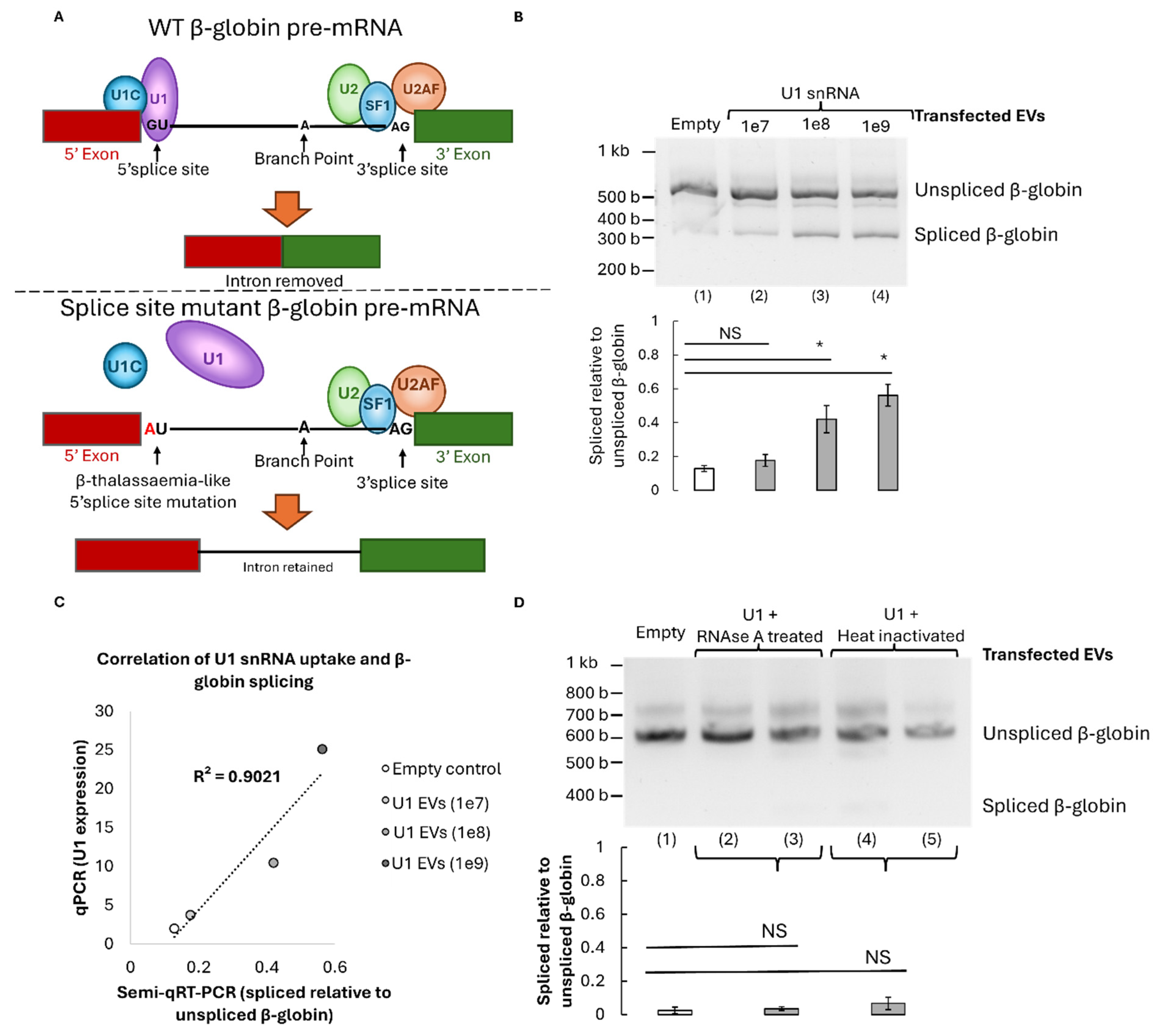

3.3. Restoration of β-Globin Pre-mRNA Splicing by U1-Containing EVs

To determine whether EV-delivered U1 snRNA can restore accurate pre-mRNA splicing, HeLa cells were transfected with a β-globin minigene bearing a β-thalassaemia-like 5′ splice-site mutation (G→A substitution at position +1). This mutation disrupts the canonical U1 snRNA binding site, resulting in aberrant splicing and the appearance of an intron-retained transcript (

Figure 4A). Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of U1-enriched EVs for 24 hours. RT-PCR analysis of β-globin transcripts revealed a significant restoration of the correctly spliced mRNA isoform dependent on the dose (1e7 (p=0.096), 1e8 (p= 0.015), or 1e9 (p=0.004)); with up to 60% correction at the highest vesicle dose tested (

Figure 4B). That represents 48% more splicing correction than background observed in cells treated with control empty EVs lacking U1 RNA. Notably, this correction efficiency correlated with the amount of U1 expression in EV transfected mutant β-globin HeLa cells measured by qPCR (

Figure 4C). This indicates a direct relationship between vesicular U1 content and splicing restoration.

To confirm that the observed rescue was mediated by intact RNA cargo, U1-EVs were pre-treated with RNase or heat-inactivated before addition to cells. Both RNAse and heat controls significantly reduced splicing recovery even compared to 1e7 treatment (p=<0.05) and no longer showed significant differences to the empty EV control with p=0.28 and p=0.12 respectively. Therefore, the corrective effect was abolished, confirming that functional U1 RNA encapsulated within EVs is essential for restoring splicing fidelity (

Figure 4D).

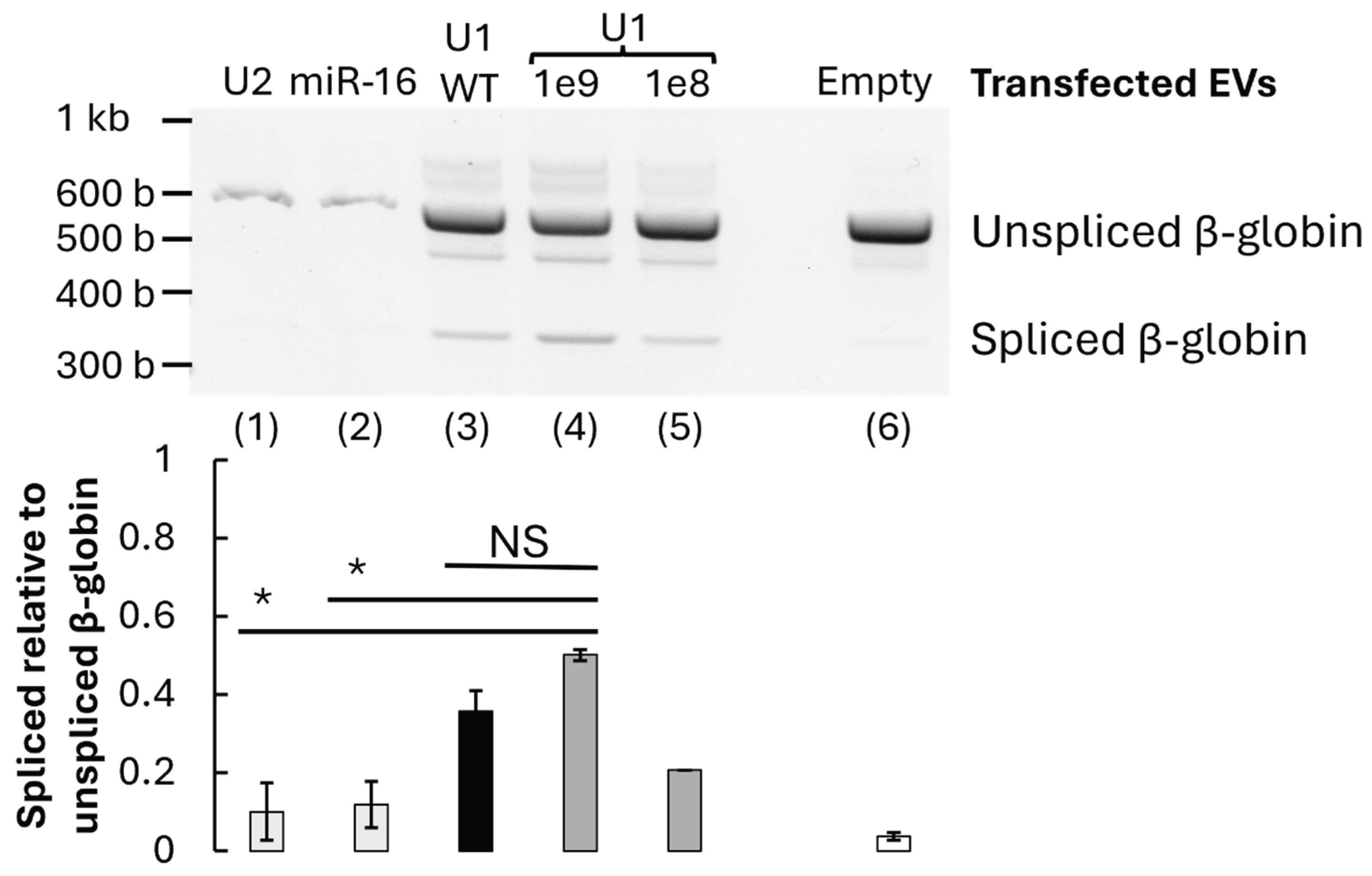

3.4. Functional Validation and Specificity of U1-Mediated Correction

To assess the specificity of U1-dependent splicing rescue, EVs enriched in unrelated small RNAs (U2 snRNA or miR-16) were prepared and applied to the mutant β-globin system. These alternative RNA-loaded vesicles restored significantly less normal splicing than 1e9 U1 snRNA (p<0.06), underscoring the specificity of U1 snRNA for 5′ splice-site recognition (

Figure 5).

Furthermore, when wild-type β-globin reporter cells were treated with U1-enriched EVs, there was no substantial change in the WT splicing pattern or significant difference between the WT and mutant β-globin, U1 1e9 treated cells (p>0.1). This suggests that the treatment does not perturb normal splicing in unaffected contexts and brings splicing levels closer to WT levels (

Figure 5).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that EV-mediated delivery of U1 snRNA specifically reconstitutes splice-site recognition in defective pre-mRNA and represents a targeted, functional correction of splicing defects in vitro.

4. Discussion

4.1. EVs as Vehicles for Functional RNA Transfer

Extracellular vesicles have emerged as powerful mediators of intercellular communication, capable of transferring proteins, lipids and nucleic acids between cells (Goo et al., 2024; Liang et al., 2025). Numerous studies have described EV-mediated transfer of microRNAs, mRNAs and long non-coding RNAs that influence gene expression and cellular phenotype. However, the delivery of spliceosomal small nuclear RNAs has not previously been reported. Our data demonstrates that U1 snRNA can be selectively incorporated into EVs upon donor cell overexpression and that these vesicles retain the molecular integrity and activity of the RNA cargo. Importantly, we observed that U1-containing EVs maintain the typical size and marker profile of exosomes, indicating that snRNA loading does not disrupt vesicle biogenesis. This suggests that small nuclear RNAs may follow similar loading pathways to other small RNAs, possibly involving RNA-binding proteins such as hnRNPA2B1 (Villarroya-Beltri et al., 2013) or SYNCRIP (Santangelo et al., 2016), which have been implicated in the selective enrichment of RNA motifs within EVs.

Other viral or non-viral vectors are available for the delivery of small biological molecules to cells and are commonplace in gene theraputics. The pros and cons of each vector and their recent developments are extensively reviewed (Geng et al., 2025; Volodina & Smirnikhina, 2025). However extracellular vesicles are often overlooked due to large-scale production difficulties (Cecchin et al., 2023), despite offering several intrinsic advantages for in vivo delivery. They are stable in circulation and can be modified for tissue-specific targeting, even across the blood-brain barrier which other vectors struggle with (Kojima et al., 2018). Moreover, because EVs originate from endogenous membranes, they are less likely to induce adverse immune reactions compared with synthetic nanoparticles (Goo et al., 2024). Hence, the ability to load and deliver small, structured RNAs such as U1 through EVs opens possibilities for designing precision RNA therapeutics that restore splice-site recognition in affected tissues.

4.2. Considerations for U1-Mediated Splicing Rescue

The correction of β-globin splicing defects by U1-enriched EVs demonstrates that vesicle-delivered U1 RNA is not only internalised but remains functional after transfer and incorporates into the recipient cell’s spliceosomal machinery, engaging directly with pre-mRNA substrates. These findings suggest that EV-mediated RNA transfer can extend beyond regulatory microRNAs to include core components of the splicing machinery itself. However, the precise intracellular fate of the transferred RNA remains to be elucidated, yet several possibilities can be considered. After uptake via endocytosis, vesicles may release their cargo into the cytoplasm (Mulcahy et al., 2014), from where U1 snRNA could enter the nucleus through the canonical importin-mediated pathway used by endogenous snRNPs (Matera & Wang, 2014). Alternatively, EVs might fuse with the plasma membrane or endosomal compartments to directly release their contents into the nucleocytoplasmic space (Joshi et al., 2020). The observed dependence on intact RNA cargo—as shown by the loss of function after RNase or heat treatment—confirms that the restorative effect arises from genuine RNA activity rather than co-transferred proteins or secondary signals. Furthermore, the absence of off-target effects on wild-type splicing indicates that U1-mediated correction is both sequence-specific and context-dependent, consistent with the well-characterised base-pairing interaction between the 5′ end of U1 snRNA and the mutated donor splice-site sequence. Here, only wildtype U1 snRNA was applied to cells, however previous studies have applied engineered U1 snRNAs to improve splicing. In these cases, the sequence of U1 snRNA was adapted to increase its complementarity specifically to the mutated splice site donor (Fernandez Alanis et al., 2012; Schmid et al., 2011). This offers the possibility of further increasing the efficiency of splice site correction in the future, possibly to achieve more than the 60% restoration identified here, which may be necessary if applying the treatment in vivo. However, our method with EV’s is beneficial in its simplicity, in displaying the first use of naturally derived U1 snRNA within EVs.

4.3. Comparison with Existing RNA Therapeutic Approaches

Current molecular strategies for correcting splicing defects include antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small molecules and gene-editing techniques. While ASOs have achieved clinical translation, particularly for disorders such as spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, they rely on repeated administration and often exhibit limited tissue penetration (Gagliardi & Ashizawa, 2021). In contrast, EV-based delivery offers a naturally biocompatible and potentially self-targeting system with prolonged bioavailability. Unlike ASOs, which modulate splicing by steric blocking, U1 snRNA acts through restoration of native spliceosome recognition, thereby reinstating physiological processing of pre-mRNA (Balestra et al., 2014; Hatch et al., 2022). Our findings thus highlight an important conceptual distinction: whereas ASOs compensate for defective splicing by redirecting the spliceosome, EV-delivered U1 directly reconstitutes a missing component of the splicing machinery. This approach could, in principle, complement or even surpass antisense therapies in specific contexts, particularly where the primary defect lies in impaired snRNA–splice-site pairing rather than regulatory mis-splicing. It is worth noting, that these therapies have been suggested to improve efficacy when used in tandem, whereby ASO delivery can block intron retention while U1 delivery can reconstitute correct splicing (Breuel et al., 2019). Therefore in more complicated splicing-related disease EV’s could be used to deliver both ASOs and snRNAs.

5. Conclusion

The present study provides the first experimental evidence that naturally derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) can mediate the intercellular transfer of spliceosomal small nuclear RNAs and restore defective pre-mRNA splicing in human cells. Using a β-globin minigene model harbouring a β-thalassaemia-like 5′ splice-site mutation, we demonstrate that donor cells overexpressing U1 snRNA encapsulate functional U1 molecules, which when delivered via engineered EVs, are capable of re-establishing canonical splice-site recognition. This finding expands the known functional repertoire of EV cargo and introduce a new RNA-based strategy for the correction of splicing-related genetic disorders including β-thalassaemia, a range of neurodegenerative and muscular disorders and cancers. Current challenges of applying EVs in theraputics include loading, targeting, and dosage efficiencies; so future work will need to investigate scalable EV production systems, improved RNA loading strategies, and tissue-specific targeting methods in vivo.

6. Future Perspectives

Although this research offers exciting potential for the use of EVs to treat many monogenic and display tissue-specific genetic disorders in humans caused by splice-site mutations, our experiments were only performed in cultured cells using a model β-globin system. Therefore, several other fundamental questions require answers before theraputics with U1 snRNA EVs could be considered. Firstly, how can encapsulation efficiency be improved? To improve EV encapsulation efficiency, future studies could aim to identify RNA–protein interactions that govern U1 packaging and engineering of RNA binding protein carriers (Liang et al., 2025; Yim et al., 2016). U1 snRNA overexpression followed by immunoprecipitation, mass spectrometry, and RNA sequencing could identify binding partners, binding motifs and sequence elements or secondary structures in the U1 snRNA important in U1 snRNA encapsulation (Nechay & Kleiner, 2020). This information could enable rational design of snRNA motifs, or co-overexpression of factors that initiate encapsulation, to enhance loading and enable up-scaled EV production. Alternatively overexpression systems as used here can improve EV encapsulation (Yim et al., 2016). Secondly, how can dosage efficiency be improved? Typically through the use of hydrogels for slow release (Guo et al., 2025; Liu & Chen, 2024). Finally, to enable in vivo clinical applications, EV’s also require engineering for targeting precision, so how can EVs be targeted to specific cells if used in vivo? This has previously been done by the inclusion of antibodies or peptides on the EV surface How can EVs be targeted to specific cells if used in vivo? Previously done by the inclusion of antibodies or peptides on the EV surface (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011; Kojima et al., 2018), so could be applied to snRNA delivery too. Beyond U1, this platform could be extended to other snRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, or engineered RNA molecules designed to correct or modulate pre-mRNA processing. Such approaches might ultimately yield a new class of RNA therapeutics that operate at the level of the spliceosome itself.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, the following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.”.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

BioRender software was used to create the graphical abstracts and schematics in Figure 1A and Figure 4A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alqurashi, H.; Alsharief, M.; Perciato, M.L.; et al. Message in a bubble: the translational potential of extracellular vesicles. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 4895–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; et al. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, Z.; Yanez-Mo, M. Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestra, D.; Faella, A.; Margaritis, P.; et al. An engineered U1 small nuclear RNA rescues splicing-defective coagulation F7 gene expression in mice. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.K.; Anczuków, O. RNA splicing dysregulation and the hallmarks of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuel, S.; Vorm, M.; Bräuer, A.U.; et al. Combining engineered U1 snRNA and antisense oligonucleotides to improve the treatment of a BBS1 splice site mutation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 18, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebulla, G.; Hai, L.; Warnken, U.; et al. Long-term CSF responses in adult patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 2 or 3 on treatment with nusinersen. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchin, R.; Troyer, Z.; Witwer, K.; et al. Extracellular vesicles: the next generation in gene therapy delivery. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Heendeniya, S.N.; Le, B.T.; et al. Splice-modulating antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutics for inherited metabolic diseases. BioDrugs 2024, 38, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, H.M.; Song, Y.; Li, D. Spliceosome complex and neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2025, 93, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ianni, E.; Obuchi, W.; Breyne, K.; et al. Extracellular vesicles for the delivery of gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, W.; Kantor, B. Lentiviral vectors for delivery of gene-editing systems based on CRISPR/Cas: current state and perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; et al. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Alanis, E.; Pinotti, M.; Dal Mas, A.; et al. An exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) strategy to correct splicing defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, R.S.; Mercuri, E.; Darras, B.T.; et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, R. Refining the splice region. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 470–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, M.; Ashizawa, A.T. The challenges and strategies of antisense oligonucleotide drug delivery. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, G.; Xu, Y.; Hu, Z.; et al. Viral and non-viral vectors in gene therapy: current state and clinical perspectives. EBioMedicine 2025, 118, 105834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Santos, J.I.; Coutinho, M.F.; et al. Development of engineered-U1 snRNA therapies: current status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; et al. Extracellular vesicles in therapeutics: a comprehensive review on applications, challenges, and clinical progress. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.; Cao, Q.; Fang, H.; et al. Recent advances and challenges of injectable hydrogels in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2025, 385, 114021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.M.; Aartsma-Rus, A.; Alves, S.; et al. Delivery of oligonucleotide-based therapeutics: challenges and opportunities. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, e13243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S.T.; Smargon, A.A.; Yeo, G.W. Engineered U1 snRNAs to modulate alternatively spliced exons. Methods 2022, 205, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, M.A.; Hastings, M.L. Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6549–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.S.; de Beer, M.A.; Giepmans, B.N.G.; et al. Endocytosis of extracellular vesicles and release of their cargo from endosomes. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 4444–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, R.; Bojar, D.; Rizzi, G.; et al. Designer exosomes produced by implanted cells intracerebrally deliver therapeutic cargo for Parkinson’s disease treatment. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Oubridge, C.; van Roon, A.-M.M.; et al. Crystal structure of human U1 snRNP reveals the mechanism of 5′ splice site recognition. eLife 2015, 4, e04986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczak, M.; Reiss, J.; Cooper, D.N. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum. Genet. 1992, 90, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczak, M.; Thomas, N.S.T.; Hundrieser, B.; et al. Single base-pair substitutions in exon-intron junctions of human genes: nature, distribution, and consequences for mRNA splicing. Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, M.C.; van Roon-Mom, W.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Possibilities and limitations of antisense oligonucleotide therapies for the treatment of monogenic disorders. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.R.; Boyle, J.A.; Mount, S.M.; et al. Are snRNPs involved in splicing? Nature 1980, 283, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Gupta, D.; Xie, J.; et al. Engineering of extracellular vesicles for efficient intracellular delivery of multimodal therapeutics including genome editors. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, K. Advances in hydrogel-based drug delivery systems. Gels 2024, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Gong, X.; Guo, X.; et al. Gene editing of the endogenous cryptic 3′ splice site corrects the RNA splicing defect in the β654-thalassemia mouse model. Hum. Gene Ther. 2024, 35, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; et al. Targeting RNA splicing modulation: new perspectives for anticancer strategy? J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, A.G.; Wang, Z. A day in the life of the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, M.C.; O’Doherty, U. Clinical use of lentiviral vectors. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R.F. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, C.; Cogne, B.; Santini, A.; et al. Dominant variants in major spliceosome U4 and U5 small nuclear RNA genes cause neurodevelopmental disorders through splicing disruption. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechay, M.; Kleiner, R.E. High-throughput approaches to profile RNA-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 54, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik, S.; Bowman, T.V. Splicing and neurodegeneration: insights and mechanisms. WIREs RNA 2019, 10, e1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, E.W.; Singh, N.N.; Seo, J.; et al. U1 snRNA interactions with deep intronic sequences regulate splicing of multiple exons of spinal muscular atrophy genes. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1412893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Shai, O.; Lee, L.; et al. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasteris, M.; Cakir, S.; Bellizzi, A.; et al. Alternative splicing in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, therapeutic implications, and 3D modeling approaches. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 107, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzo, P.; Bergamin, N.; Bon, M.; et al. Rescue of common and rare exon 2 skipping variants of the GAA gene using modified U1 snRNA. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorná, P.; Aupič, J.; Fica, S.; et al. Decoding spliceosome dynamics through computation and experiment. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 9807–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wu, L.; Qu, R.; et al. History of development of the life-saving drug “Nusinersen” in spinal muscular atrophy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 942976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguraman, P.; Balachandran, A.A.; Chen, S.; et al. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated splice switching: potential therapeutic approach for cancer mitigation. Cancers 2021, 13, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina Haque, U.; Kohut, M.; Yokota, T. Comprehensive review of adverse reactions and toxicology in ASO-based therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from FDA-approved drugs to peptide-conjugated ASO. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 7, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharkar, M.K.; Chow, V.T.K.; Kangueane, P. Distributions of exons and introns in the human genome. In Silico Biol. 2004, 4, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, L.; Giurato, G.; Cicchini, C.; et al. The RNA-binding protein SYNCRIP is a component of the hepatocyte exosomal machinery controlling microRNA sorting. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F.; Glaus, E.; Barthelmes, D.; et al. U1 snRNA-mediated gene therapeutic correction of splice defects caused by an exceptionally mild BBS mutation. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, M.M.; Swanson, M.S. RNA mis-splicing in disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, E.S.; Leal, C.B.Q.S.; Sinatti, V.V.C.; et al. Role of the U1 snRNP complex in human health and disease. WIREs RNA 2025, 16, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmezler, E.; Stuani, C.; Hız Kurul, S.; et al. Characterization and engineered U1 snRNA rescue of splicing variants in a Turkish neurodevelopmental disease cohort. Hum. Mutat. 2024, 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, R.; Orkin, S.H.; Maniatis, T. Specific transcription and RNA splicing defects in five cloned β-thalassaemia genes. Nature 1983, 302, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanski, L.M.; Leclair, N.; Anczuków, O. Alternative-splicing defects in cancer: splicing regulators and their downstream targets, guiding the way to novel cancer therapeutics. WIREs RNA 2018, 9, e1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Delen, M.; Derdelinckx, J.; Wouters, K.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials assessing safety and efficacy of human extracellular vesicle-based therapy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Sánchez-Cabo, F.; et al. Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodina, O.; Smirnikhina, S. The future of gene therapy: a review of in vivo and ex vivo delivery methods for genome editing-based therapies. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, H.A.; Svobodova, E.; Herrera, N.R.; et al. Tailored antisense oligonucleotides designed to correct aberrant splicing reveal actionable groups of mutations for rare genetic disorders. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnant, K.N.; Nadif Kasri, N.; Vissers, L.E.L.M. Systematic analysis of genetic and phenotypic characteristics reveals antisense oligonucleotide therapy potential for one-third of neurodevelopmental disorders. Genome Med. 2025, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, N.; Ryu, S.-W.; Choi, K.; et al. Exosome engineering for efficient intracellular delivery of soluble proteins using optically reversible protein–protein interaction module. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; Hang, J.; et al. An atomic structure of the human spliceosome. Cell 2017, 169, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Weiner, A.M. A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA suppresses a 5′ splice site mutation. Cell 1986, 46, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.B.; Bernstock, J.D.; Broustas, C.G.; et al. The role of RAD9 in tumorigenesis. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 3, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

EV isolation and classification by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). A) Schematic representation of the NTA analysis method. A native human U1 snRNP expression cassette was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 plasmid (top left). This plasmid was transfected into HEK293T cells which were grown in OptiMEM (middle left). Cells were collected by differential centrifugation (middle right). The supernatant was filtered through and ultracentrifuged to pellet EVs (middle bottom). Pellets were washed and resuspended in PBS for size and concentration was measured with a NanoSight NS300 system. B) Size distribution analysis comparing U1 (light grey) and, U2 (dark grey) snRNA-containing EVs to empty control EVs (red). Error bars represent standard deviation between 2 biological replicates (n=2). C-E) Median diameter and average overall or peak size yields of isolated control EVs (white), U1-containing EVs (light grey) and U2-containing EVs (dark grey). Error bars show standard deviation between 2-3 biological replicates (n=2-3). Significance values are calculated with a two tailed Welch’s T. test.

Figure 1.

EV isolation and classification by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). A) Schematic representation of the NTA analysis method. A native human U1 snRNP expression cassette was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 plasmid (top left). This plasmid was transfected into HEK293T cells which were grown in OptiMEM (middle left). Cells were collected by differential centrifugation (middle right). The supernatant was filtered through and ultracentrifuged to pellet EVs (middle bottom). Pellets were washed and resuspended in PBS for size and concentration was measured with a NanoSight NS300 system. B) Size distribution analysis comparing U1 (light grey) and, U2 (dark grey) snRNA-containing EVs to empty control EVs (red). Error bars represent standard deviation between 2 biological replicates (n=2). C-E) Median diameter and average overall or peak size yields of isolated control EVs (white), U1-containing EVs (light grey) and U2-containing EVs (dark grey). Error bars show standard deviation between 2-3 biological replicates (n=2-3). Significance values are calculated with a two tailed Welch’s T. test.

Figure 2.

EV validation by Western blot analysis. A+B) EV positive markers displayed in blots in biological triplicates (n=3) and quantified below in bar graphs with error bars showing the standard deviation. A) TSG101 and Cd9 markers; B) CD63 and CD9. CD63 size is approximate and has two bands due to post-translational modifications.

Figure 2.

EV validation by Western blot analysis. A+B) EV positive markers displayed in blots in biological triplicates (n=3) and quantified below in bar graphs with error bars showing the standard deviation. A) TSG101 and Cd9 markers; B) CD63 and CD9. CD63 size is approximate and has two bands due to post-translational modifications.

Figure 3.

Identification and validation of U1 snRNA within EVs isolated from U1 overexpression HEK293 cells. A) RT-qPCR highlights inclusion of U1 snRNA within EVs from control HEK293 cells (white) and EVs isolated from U1 overexpression cells (grey). Expression is relative to U6 snRNA reference (2^ΔCt). B) RT-qPCR displaying U1 snRNA content from U1 overexpression HEK293 cells, relative to U6 snRNA and control cell isolated EVs (2^-ΔΔCt), upon treatment with RNAseA only (grey) or RNAseA with detergent (dark grey). A+B) Error bars show standard deviation between 3 biological replicates (n=3). Significance is determined by one-tailed Welch’s T. tests.

Figure 3.

Identification and validation of U1 snRNA within EVs isolated from U1 overexpression HEK293 cells. A) RT-qPCR highlights inclusion of U1 snRNA within EVs from control HEK293 cells (white) and EVs isolated from U1 overexpression cells (grey). Expression is relative to U6 snRNA reference (2^ΔCt). B) RT-qPCR displaying U1 snRNA content from U1 overexpression HEK293 cells, relative to U6 snRNA and control cell isolated EVs (2^-ΔΔCt), upon treatment with RNAseA only (grey) or RNAseA with detergent (dark grey). A+B) Error bars show standard deviation between 3 biological replicates (n=3). Significance is determined by one-tailed Welch’s T. tests.

Figure 4.

β-thalassemia-like β-globin pre-mRNA splicing can be rescued by U1-containing EVs. A) Schematic representation of the splicing mechanism. Top shows a canonical representation of a section of the WT β-globin pre-mRNA consisting of a 5’ exon in red, an intron to be spliced out in black and a second exon on the 3’ end in green. Several critical members of the spliceosome are shown including U1 (purple) along with various auxiliary splicing factors. When the wildtype ‘GU’ dinucleotide is available, U1 base pairs here to initiate splicing (top). Without this association, in the mutant β-globin system (bottom), U1 cannot bind, causing intron retention and dysfunctional β-globin production. B) Representative RT-PCR displaying expression of spliced and unspliced β-globin pre-mRNA after transfection with empty EVs (1), or 10^7,10^8 or 10^9 EVs containing U1 snRNA (2-4). Quantifications represent averages across 2 biological replicates (n=2). C) Plot displaying the correlation between U1 snRNA-containing EV amount and splicing recovery in mutant β-globin HeLa cells. D) Representative RT-PCR (top) highlighting the expression of spliced or unspliced β-globin pre-mRNA isoforms in β-globin mutant cells transfected with EVs containing an empty control (1), or U1 snRNAs (2-5). Prior to transfection lane (2/3) technical replicates were RNAse treated, while lane 4/5 technical replicates were heat inactivated. Bands were quantified (bottom) in three biological replicates (n=3) each with two technical replicates. Significance calculated with one-tailed Welch’s T. tests; *P=≤0.05, NS p=>0.05, not significant.

Figure 4.

β-thalassemia-like β-globin pre-mRNA splicing can be rescued by U1-containing EVs. A) Schematic representation of the splicing mechanism. Top shows a canonical representation of a section of the WT β-globin pre-mRNA consisting of a 5’ exon in red, an intron to be spliced out in black and a second exon on the 3’ end in green. Several critical members of the spliceosome are shown including U1 (purple) along with various auxiliary splicing factors. When the wildtype ‘GU’ dinucleotide is available, U1 base pairs here to initiate splicing (top). Without this association, in the mutant β-globin system (bottom), U1 cannot bind, causing intron retention and dysfunctional β-globin production. B) Representative RT-PCR displaying expression of spliced and unspliced β-globin pre-mRNA after transfection with empty EVs (1), or 10^7,10^8 or 10^9 EVs containing U1 snRNA (2-4). Quantifications represent averages across 2 biological replicates (n=2). C) Plot displaying the correlation between U1 snRNA-containing EV amount and splicing recovery in mutant β-globin HeLa cells. D) Representative RT-PCR (top) highlighting the expression of spliced or unspliced β-globin pre-mRNA isoforms in β-globin mutant cells transfected with EVs containing an empty control (1), or U1 snRNAs (2-5). Prior to transfection lane (2/3) technical replicates were RNAse treated, while lane 4/5 technical replicates were heat inactivated. Bands were quantified (bottom) in three biological replicates (n=3) each with two technical replicates. Significance calculated with one-tailed Welch’s T. tests; *P=≤0.05, NS p=>0.05, not significant.

Figure 5.

Validation of U1-mediated splicing recovery. RT-PCR expression example (top) and quantification (bottom) of spliced or unspliced β-globin pre-mRNA isoforms (n=2-3). Transfected EVs contained U2 snRNA control (1, light grey), miR-16 control (2, light grey), U1 snRNA (3, black), U1 snRNA at 1e9 or 1e8 concentrations (4/5, dark grey), or empty EV control (6, white). Each was transfected into mutant β-globin cells except the lane (3, black) control where U1 snRNA was transfected into wild-type (WT) β-globin cells. Significance calculated with one-tailed Welch’s T. tests; *P=≤0.05, NS p=>0.05, not significant.

Figure 5.

Validation of U1-mediated splicing recovery. RT-PCR expression example (top) and quantification (bottom) of spliced or unspliced β-globin pre-mRNA isoforms (n=2-3). Transfected EVs contained U2 snRNA control (1, light grey), miR-16 control (2, light grey), U1 snRNA (3, black), U1 snRNA at 1e9 or 1e8 concentrations (4/5, dark grey), or empty EV control (6, white). Each was transfected into mutant β-globin cells except the lane (3, black) control where U1 snRNA was transfected into wild-type (WT) β-globin cells. Significance calculated with one-tailed Welch’s T. tests; *P=≤0.05, NS p=>0.05, not significant.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |