Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

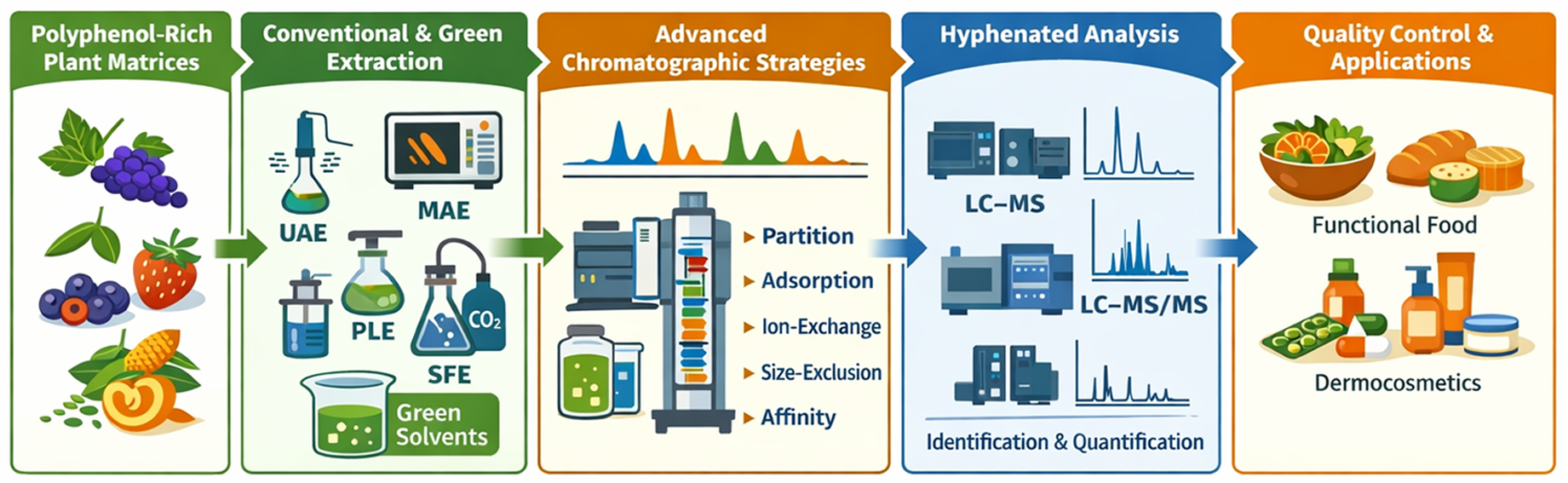

Polyphenols are a structurally diverse group of plant secondary metabolites widely recognized for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and chemoprotective properties, which have stimulated their extensive use in food, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic products. However, their chemical heterogeneity, wide polarity range, and strong interactions with plant matrices pose major challenges for efficient extraction, separation, and reliable analytical characterization. This review provides a critical overview of contemporary strategies for the extraction, separation, and identification of polyphenols from plant-derived matrices. Conventional extraction methods, including maceration, Soxhlet extraction, and percolation, are discussed alongside modern green technologies such as ultrasound-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, and supercritical fluid extraction. Particular emphasis is placed on environmentally friendly solvents, including ethanol, natural deep eutectic solvents, and ionic liquids, as sustainable alternatives that improve extraction efficiency while reducing environmental impact. The review further highlights chromatographic separation approaches—partition, adsorption, ion-exchange, size-exclusion, and affinity chromatography—and underlines the importance of hyphenated analytical platforms (LC–MS, LC–MS/MS, and LC–NMR) for comprehensive polyphenol profiling. Key analytical challenges, including matrix effects, compound instability, and limited availability of reference standards, are addressed, together with perspectives on industrial implementation, quality control, and standardization.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Polyphenols: Structural Diversity, Biological Significance, and Analytical Challenges

1.2. Applications of Polyphenols in Food, Pharmaceutical, and Cosmetic Industries

1.3. Challenges in the Extraction and Analysis of Polyphenols

1.4. Aim and Scope of This Review

2. Overview of Major Plant Sources of Polyphenols

2.1. Natural Sources and Distribution of Polyphenols

2.1.1. Fruits

2.1.2. Wine

2.1.3. Tea

2.1.4. Medicinal Plants

2.1.5. Agro-industrial By-products

2.2. Structural Classification of Polyphenols (Flavonoids, Phenolic Acids, Tannins, Stilbenes, Lignans)

2.2.1. Flavonoids

2.2.2. Phenolic Acids

2.2.3. Tannins

- Hydrolyzable tannins − esters of gallic acid or ellagic acid with glucose (e.g., gallotannins, ellagitannins). These tannins readly hydrolyze under acidic or enzymatic conditions.

- Condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins) − oligomers or polymers of flavan-3-ols (catechin, epicatechin, gallocatechin). Their polymerization degree strongly influences biological activity and extractability [33]

2.2.4. Stilbenes

2.2.5. Lignans

| Class of polyphenols | Core structure | Key subgroups/ examples | Structural features | Main plant sources |

| Flavonoids | C6-C3-C6 (flavan nucleus) |

Flavonols (quercetin), flavones (luteolin), flavan-3-ols (catechin),Anthocyanins (cyaniding), isoflavones (genistein) |

Oxidation state of C-ring, glacosylation common |

Fruits, tea wine, medicinal plants |

| Phenolic acids | Hydroxybenzoic (C6-C1) /Hydroxycinnamic (C6-C3) |

Gallic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, chlorogenic acid | Free or esterified forms | Fruits, cereals, coffee, vegetables |

| Tannins | Polymerized polyphenols | Condensed tannins (procyanidins), Hydrolyzable tannins (gallotannins) |

High MW, protein-binding |

Grapes, nuts, tea, pomegranate |

| Stilbenes | 1,2-diphenylethylene | Resveratrol, piceid | Cis/trans isomerism |

Grapes, berries, wine |

| Lignans | Dibenzylbutane-type dimers |

Secoisolariciresinol, pinoresinol | Derived from coniferyl alcohol |

Flaxseed, sesame, grains |

| Class | Dominant biological activities | References |

| Flavonoids | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, enzyme modulation, cardioprotective | [1] |

| Phenolic acids | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiinflamatory | [25] |

| Tannins | Antioxidant, metal-chelating, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory | [33] |

| Stilbenes | Antioxidant, cardioprotective, anti-aging, antimicrobial | [27] |

| Lignans | Anticancerogenic, estrogenic/antiestrogenic, cardiometabolic effects | [34] |

2.3. Structure−Activity Relationship of Polyphenols

| Structural feature | Influence on bioactivity | Examples |

| Ortho-dihydroxy groups | High antioxidant activity; metal chelation | Quercetin, catechn |

| Conjugated C2=C3 bond + 4-keto group | Radical stabilization; increased antioxidant potential |

Flavonols |

| Gelloylation | Strong radical scavenging: enhanced bioactivity |

EGCG |

| High degree of polymerization | Protein binding; antimicrobial activity; reduced absorption |

Tannis |

| Glycosylation | Increased stability and solubility; reduced lipophilicity | Anthocyanins, rutin |

| Acylation | Improved pH and thermal stability | Acylated anthocyanins |

| Cis/trans isomerism | Differences instability and efficacy | Trans-resveratrol |

| Microbial biotransformation | Formation of active metabolites | Lignans→enterolactone |

3. Extraction Methods for Polyphenols

3.1. Conventional Extraction Methods for Polyphenols: Maceration, Soxhlet Extraction, and Percolation

|

Extraction Method |

Plant Material |

Solvent & Condition |

Extracted Polyphenols |

Analytical Technique |

Reference |

| Maceration |

Cmellia sinensis (green tea) |

70% ethanol, 25°C, 48h |

Catechin, Epicatechin, EGCG |

HPLC-DAD | [23,36] |

| Maceration | Punica granatum (pomegranate Peel) |

80% methanol | Punicalagin, ellagic acid | HPLC | [40] |

| Maceration | Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry) |

Methanol + 1% HCL | Anthocyanins (malvidin, delphinidin) |

LC-MS/MS | [23] |

| Soxhlet | Rosmarinus officinalis |

Ethanol, 78°C, 6h | Rosmarinic, ferulic acid | HPLC | [37] |

| Soxhlet | Citrus limon (lemon peel) |

Methanol | Hesperidin | UHPLC | [41] |

| Soxhlet | Vitis vinifera | Ethyl acetate | Resveratrol, piceatannol |

HPLC | [18,42,43] |

| Percolation | Salvia officinalis | 70% ethanol | Caffeic and rosmarinic acid |

HPLC | [44] |

| Percolation | Ginkgo biloba | Acetone:water (60:40) |

Quercetin, Kaempferol, isorhamnetin |

HPLC-DAD/MS | [39] |

| Percolation | Hypericum perforatum | 80% ethanol | Hypericin, rutin, quercetin | LC-MS | [30] |

3.2. Modern and “Green” Extraction Techniques for Polyphenols

3.2.1. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

3.2.2. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

3.2.3. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE/ASE)

3.2.4. Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

| Plant material | Method | Target polyphenols | Extraction conditions | Outcome |

| Grape pomace | UAE | Resveratrol | 40 kHz, 25-40 °C | 3× higher yield |

| Grape skins | MAE | Quercetin, myricetin | 60 °C, Ethanol | 2-3× higher yield |

| Grape pomace | PLE | Flavonoids, phenolic acids | 150°C, 10 MPa | +40% yield |

| Grapes, rosemary | SFE | Stilbenes, diterpenes | 250-300 bar, 10% | High-purity extracts |

3.2.5. Use of Environmentally Friendly Solvents

3.2.6. Ethanol as a Green Solvent

3.2.7. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents

3.2.8. Ionic Liquids

| Solvent type | Source/composition |

Environmental Profile |

Advantages | Limitations |

Typical polyphenols extracted |

| Ethanol | Renewable (fermentation) |

Biodegradable, low toxicity | Food-grade, Recoverable, tunable polarity |

Lower solubility for highly hydrophobic compounds |

Flavonoids, Phenolic acids, Stilbenes |

| NaDES | Sugars, amino acids | Biodegradable, nonvolatile | Highly tunable, stabilizing effect. GRAS components | High viscosity. Sometimes difficult removal |

Anthocyanins, catechins, chlorogenic acid |

| Ionic liquids | Organic cations + inorganic/organic anions | Low vapor pressure; biodegrability varies |

Highly tunable, excellent solvating power | Cost, potential toxicity, complex recycling | Rutin, quercetin, caffeic acid |

4. Separation and Purification Chromatographic Techniques for Polyphenols Identification

4.1. Fundamental Principles of Chromatography

| Identified Polyphenols | Chromatographic Method | Plant Source | Citation |

| Quercetin, Kaempferol, Rutin, Catechin | UHPLC-DAD-MS/MS | Vitis vinifera (Grape skin) | [58] |

| Chlorogenic acid, Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid | HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS | Coffea arabica | [59] |

| Epicatechin, Procyanidin B1, B2 | UHPLC-MS/MS | Camellia sinensis (Tea) | [60] |

| Naringenin, Hesperidin, Eriodictyol | LC-MS/MS | Citrus sinensis (Orange peel) | [61] |

| Malvidin-3-O-glucoside, Petunidin-3-O-glucoside | UHPLC-ESI-MS | Red grapes | [62] |

| Isorhamnetin, Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | HPLC-QTOF-MS | Hippophae rhamnoides | [63] |

| Catechin, Epicatechin gallate, Gallocatechin | UHPLC-MS/MS | Theobroma cacao | [64] |

| Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, Astragalin | UHPLC-MS | Moringa oleifera | [65] |

| Rutin, Hyperoside, Isoquercitrin | HPLC-DAD-MS | Hypericum perforatum | [66] |

| Chlorogenic acid derivatives | LC-QTOF-MS | Lonicera japonica | [67] |

| Genistein, Daidzein, Formononetin | HPLC-MS/MS | Trifolium pratense | [68] |

| Anthocyanins (Delphinidin, Cyanidin) | UHPLC-MS | Vaccinium myrtillus | [69] |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS | Camellia sinensis | [70] |

| Rosmarinic acid, Caffeic acid | HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS | Salvia officinalis | [71] |

| Quercetin derivatives, Myricetin | UHPLC-MS | Allium cepa | [72] |

| Resveratrol, Piceid | UHPLC-MS/MS | Polygonum cuspidatum | [73] |

| Polymeric procyanidins | LC-QTOF-MS | Malus domestica | [74] |

| Phenolic acids, Flavonols | UHPLC-MS/MS | Rubus fruticosus | [75] |

4.1. Partition Chromatography

4.2. Adsorption Chromatography

4.3. Ion-Exchange Chromatography

4.4. Gel-Exclusion (Size-Exclusion) Chromatography

4.5. Specific Interactions – Affinity Chromatography

- Planar chromatography (thin-layer chromatography, paper chromatography) – separation occurs on a flat surface.

- Column chromatography – separation occurs within a column packed or coated with the stationary phase.

- Frontal analysis (continuous introduction of the analyzed solution into the column, where the least strongly “bound” substances move rapidly through the column and appear first in the effluent, i.e., in the eluate collected during elution, followed by the remaining components); For example, Snyder (2011) demonstrated the use of frontal analysis to characterize adsorption behavior of phenolic acids and flavonoids on silica and polymeric adsorbents, providing insight into competitive adsorption phenomena relevant for polyphenol separations [99]. Similarly, frontal chromatographic approaches have been applied to evaluate the interaction of catechins and simple phenolic acids with reversed-phase and normal-phase sorbents, aiding in the selection of optimal stationary phases for plant extract fractionation.

- Displacement analysis (only a small volume of the sample solution is introduced at the top of the column, after which the chromatogram is developed by passing either a solvent or a dissolved substance with a higher affinity for the stationary phase than any component of the analyzed mixture; this displacer forces all adsorbed substances to move, displacing one another); Although less frequently used for routine analysis, displacement chromatography has been successfully applied in preparative-scale isolation of plant polyphenols, particularly when high loading capacity and enrichment are required. For instance, displacement strategies using strongly adsorbing solvents or modifiers have been reported for the separation of flavonoid glycosides and aglycones from Ginkgo biloba and Camellia sinensis extracts, enabling enrichment of quercetin and kaempferol derivatives prior to further purification by elution chromatography or HPLC [100].

- Elution method (the most commonly used method of analysis, in which dissolved substances bind to the stationary phase from a small volume of solution at the top of the column and are then washed out with a pure solvent or a mixture of solvents—the eluent—under continuous flow). This mode is extensively applied for the isolation of plant-derived polyphenols, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes, and tannins. Classical examples include the separation of chlorogenic acids and caffeic acid derivatives from coffee and artichoke, flavonols such as quercetin, kaempferol, and myricetin from onion and grape skins, and resveratrol and its oligomers from grape pomace, typically using silica gel, Sephadex LH-20, or reversed-phase C18 stationary phases with gradient elution systems. Elution chromatography thus represents the cornerstone technique for polyphenol purification prior to spectroscopic or hyphenated chromatographic identification [101,102].

4.6. The Role of Reliable Analysis in Quality Control and Biological Activity Assessment

4.7. Examples of Translating Laboratory Research into Industrial Applications

5. Analytical Techniques for Detection and Characterization

5.1. Spectroscopic and Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Techniques for Detection and Characterization

| Technique | Type of information provided | Key advantages | Limitations | Typical applications |

| UV-VIs | Absorption maxima; total phenolics |

Fast, inexpensive, ideal for TPC/TFC | Low selectivity; spectral overlap |

TPC assays; degradation |

| HPLC-DAD | Retention + full UV-Vis spectra | High resolution: tentative identification |

Cannot distinguish all isomers | Profiling anthocyanins and flavonols in wine |

| LC-MS/MS | Molecular mass + fragmentation | Highest sensitivity and selectivity | High cost Complex data |

Identification of flavonoids, stilbenes tannins |

| NMR | Complete structural information |

Definitive structure; qNMR | Lower sensitivity; requires pure sample | Structural elucidation; extract standardization |

| PCA/PLS-DA | Chemometric Classification |

Powerful pattern recognition | Requires large, quality datasets |

Authentication of wine and plant materials |

5.2. Hyphenated Techniques: LC-MS, LC-MS/MS, and LC-NMR

| Technique | Main Advantages | Limitations | Typical applications |

| LC-MS | High sensitivity and selectivity; suitable for profiling large numbers of polyphenols; accurate mass detection (QTOF, Orbitrap) |

Possible ion suppression requires skilled optimization of ionization source | Profiling > 120 phenolics in grapes [112]; terrior-specific wine analysis [113]; catechin monitoring in tea [123]; grape pomace metabolomics [116]. |

| LC-MS/MS | Ultra-high sensitivity; ideal for trace quantification; MRM transitions enable excellent matrix tolerance |

Requires standards for quantitative methods; limited structural information |

Pharmacokinetics of resveratrol metabolites [117]; flavonoids in propolis [118]; phenolics in cosmetics [119]; phenolic acids in fermented juices [120] |

| LC-NMR | Provides full structural elucidation without standards; ideal for isomers and novel compounds; minimal sample prep |

Lower sensitivity; expensive instrumentation; long acquisition time |

Identification of ellagitannins in oak [121]; cis/trans stilbene differentiation [110]; polyphenols in pomegranate juice [120]; structural analysis of rare flavonoids [122] |

5.3. Application of Multivariate Analysis (PCA and PLS-DA) in the Identification and Classification of Polyphenols

6. Analytical Challenges and Standardization

6.1. Matrix Effects, Degradation, and Stability of Polyphenols

6.2. Lack of Reference Standards and Quantification Challenges

6.3. Method Validation

6.4. Proposed Guidelines for Future Harmonization of Analytical Method

7. Applications in Functional Foods, Nutraceuticals, and Dermocosmetics

7.1. Polyphenols as Bioactive Components in Formulations

7.2. Role of Reliable Analysis in Quality Control and Biological Activity

7.3. Examples of Translation of Laboratory Research into Industry

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| ASE | Accelerated Solvent Extraction |

| CE | Capillary Electrophoresis |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| COSY | Correlation Spectroscopy |

| DAD | Diode-Array Detection |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| EC | Epicatechin |

| ECG | Epicatechin Gallate |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin Gallate |

| ESI | Electrospray Ionization |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| GRAS | Generally Recognized As Safe |

| HBA | Hydrogen Bond Acceptor |

| HBD | Hydrogen Bond Donor |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HRMS | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence |

| HMBC | Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation |

| ILs | Ionic Liquids |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography |

| LC–HRMS | Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| LC–MS | Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| LC–MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LC–NMR | Liquid Chromatography–Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| MAE | Microwave-Assisted Extraction |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| MS/MS | Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| NaDES | Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| NOESY | Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy |

| ORAC | Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PLE | Pressurized Liquid Extraction |

| PLS-DA | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| qNMR | Quantitative Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| RP-HPLC | Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| scCO2 | Supercritical Carbon Dioxide |

| SEC | Size-Exclusion Chromatography |

| SFE | Supercritical Fluid Extraction |

| TFC | Total Flavonoid Content |

| UAE | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction |

| UHPLC | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy |

References

- Scalbert, A.; Johnson, I.T.; Saltmarsh, M. Polyphenols: Antioxidants and Beyond. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.2005, 81, 215S–217S. [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients2010, 2, 1231–1246. [CrossRef]

- Farga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The Effects of Polyphenols and Other Bioactives on Human Health. Food Funct.2019, 10, 514–528. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, A.; Venter, P.; Pasch, H. Recent Advances and Trends in the Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A2016, 1430, 16–78. [CrossRef]

- Ignat, I.; Volf, I.; Popa, V.I. A Critical Review of Methods for Characterization of Polyphenolic Compounds in Fruits and Vegetables. Food Chem.2011, 126, 1821–1835. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and Polyphenolics in Foods, Beverages and Spices: Antioxidant Activity and Health Effects—A Review. J. Funct. Foods2015, 18, 820–897. [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Cravotto, G. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Concept and Principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2012, 13, 8615–8627. [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Food and Natural Products: Mechanisms, Techniques, Combinations, Protocols and Applications. Ultrason. Sonochem.2017, 34, 540–560. [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. Metabolomics for Investigating Physiological and Pathophysiological Processes. Physiol. Rev.2019, 99, 1819–1875. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as New Potential Media for Green Technology. Anal. Chim. Acta2013, 766, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Aparicio, S.; Ullah, R.; Atilhan, M. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Physicochemical Properties and Gas Separation Applications. Energy Fuels2015, 29, 7919–7930. [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Williamson, G. Dietary Intake and Bioavailability of Polyphenols. J. Nutr.2000, 130, 2073S–2085S. [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D.R.; Claus, A.; Carle, R.; Schieber, A. Polyphenol Screening of Pomace from Red and White Grape Varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) by HPLC–DAD–MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem.2004, 52, 4360–4367. [CrossRef]

- Santana, A.L.; Peterson, J.M.; Perumal, R.; et al. High-Molecular-Weight Polyphenols Separated by Sephadex LH-20. ACS Food Sci. Technol.2025, 5, 1010–1023. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xue, F.; Yu, S.; Du, S.; Yang, Y. Subcritical Water Extraction of Natural Products. Molecules2021, 26, 4004. [CrossRef]

- Viñas, P.; Campillo, N. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Polyphenols in Foods. In Polyphenols in Plants, 2nd ed.; Ramawat, K.G.; Mérillon, J.-M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 285–316. [CrossRef]

- Procházková, D.; Boušová, I.; Wilhelmová, N. Antioxidant and Prooxidant Properties of Flavonoids. Fitoterapia2011, 82, 513–523. [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol: The In Vivo Evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.2006, 5, 493–506. [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.2004, 79, 727–747. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.A.; Katiyar, S.K. Skin Photoprotection by Natural Polyphenols: Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant and DNA Repair Mechanisms. Arch. Dermatol. Res.2010, 302, 71–83. [CrossRef]

- Zillich, O.V.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P.; Kerscher, M. Polyphenols as Active Ingredients for Cosmetic Products. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci.2015, 37, 455–464. [CrossRef]

- Păvăloiu, R.-D.; Sha’at, F.; Neagu, G.; Deaconu, M.; Bubueanu, C.; Albulescu, A.; Sha’at, M.; Hlevca, C. Encapsulation of Polyphenols from Lycium barbarum Leaves into Liposomes as a Strategy to Improve Their Delivery. Nanomaterials2021, 11, 1938. [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert-Vian, M.; Cravotto, G. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Concept and Principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2012, 13, 8615–8627. [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Concept and Principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2017, 18, 708. [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary Polyphenolics in Human Health: Structures, Bioavailability, and Evidence of Protective Effects against Chronic Diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal.2013, 18, 1818–1892. [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Acylated Anthocyanins from Edible Sources and Their Applications in Food Systems. Biochem. Eng. J.2003, 14, 217–225. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.L.; Sacks, G.L.; Jeffery, D.W. Understanding Wine Chemistry; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, C.; Artacho, R.; Giménez, R. Beneficial Effects of Green Tea—A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr.2006, 25, 79–99. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, K.; Kammerer, D.R.; Carle, R.; Schieber, A. Identification and Quantification of Caffeoylquinic Acids and Flavonoids from Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Heads, Juice, and Pomace by HPLC–DAD–ESI/MSⁿ. J. Agric. Food Chem.2004, 52, 4090–4096. [CrossRef]

- Nobakht, S.Z.; Akaberi, M.; Mohammadpour, A.; Moghadam, A.T.; Emami, A. Hypericum perforatum: Traditional Uses, Clinical Trials, and Drug Interactions. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci.2022, 25, 1045–1058. [CrossRef]

- Amendola, D.; De Faveri, D.M.; Spigno, G. Grape Marc Phenolics: Extraction Kinetics, Quality and Stability of Extracts. J. Food Eng.2010, 97, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Plant Secondary Metabolites: Occurrence, Structure and Role in the Human Diet, Crozier, A.; Clifford, M.N.; Ashihara, H. (Eds.) Plant Secondary Metabolites: Occurrence, Structure and Role in the Human Diet; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006.

- Quideau, S.; Deffieux, D.; Douat-Casassus, C.; Pouységu, L. Plant Polyphenols: Chemical Properties, Biological Activities, and Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2011, 50, 586–621. [CrossRef]

- Hano, C.F.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Davin, L.B.; Cort, J.R.; Lewis, N.G. Editorial: Lignans—Insights into Their Biosynthesis, Metabolic Engineering, Analytical Methods and Health Benefits. Front. Plant Sci.2021, 11, 630327. [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure–Antioxidant Activity Relationships of Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med.1996, 20, 933–956. [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert-Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Strube, J.; Uhlenbrock, L.; Gunjevic, V.; Cravotto, G. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Origins, Current Status, and Future Challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem.2019, 118, 248–263. [CrossRef]

- Mena, P.; Cirlini, M.; Tassotti, M.; Herrlinger, K.A.; Dall’Asta, C.; Del Rio, D. Phytochemical Profiling of Flavonoids, Phenolic Acids, Terpenoids, and Volatile Fraction of a Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract. Molecules2016, 21, 1576. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Lin, L.G.; Ye, W.C. Techniques for Extraction and Isolation of Natural Products: A Comprehensive Review. Chin. Med.2018, 13, 20. [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, T.A. Chemical Analysis of Ginkgo biloba Leaves and Extracts. J. Chromatogr. A2002, 967, 21–55. [CrossRef]

- Negi, P.S.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Jena, B.S. Antioxidant and Antimutagenic Activities of Pomegranate Peel Extract. Food Chem.2003, 80, 393–397. [CrossRef]

- Yeddes, W.; Bettaieb Rebey, I.; Yazidi, R.; Ben Abdennebi, A.; Hammami, M.; Ben Farhat, M.; Saidani Tounsi, M. Eco-Friendly Extraction of Hesperidin from Citrus Peels: A Comparative Study of Soxhlet, Ultrasound-Assisted, and Microwave-Assisted Methods for Improved Yield and Antioxidant Properties. Int. J. Environ. Health Res.2025, 35, 3359–3370. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, J.V.; García-Alvarado, M.A.; Carcel, J.A.; Mulet, A. Extraction Kinetics Modeling of Antioxidants from Grape Stalk (Vitis vinifera var. Bobal): Influence of Drying Conditions. J. Food Eng.2010, 101, 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Eyiler Yilmaz, E.; Özvural, E.B.; Vural, H. Extraction and Identification of Proanthocyanidins from Grape Seed (Vitis vinifera) Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids2011, 55, 924–928. [CrossRef]

- Durling, N.E.; Catchpole, O.J.; Grey, J.B.; Webby, R.F.; Mitchell, K.A.; Foo, L.Y.; Perry, N.B. Extraction of Phenolics and Essential Oil from Dried Sage (Salvia officinalis) Using Ethanol–Water Mixtures. Food Chem.2007, 101, 1417–1424. [CrossRef]

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.M.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Omar, A.K.M. Techniques for Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Materials: A Review. J. Food Eng.2013, 117, 426–436. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Tailoring Properties of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents with Water to Facilitate Their Applications. Food Chem.2015, 187, 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Eskilsson, C.S.; Björklund, E. Analytical-Scale Microwave-Assisted Extraction. J. Chromatogr. A2000, 902, 227–250. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Turner, C. Pressurized Liquid Extraction as a Green Approach in Food and Herbal Plants Extraction: A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta2011, 703, 8–18. [CrossRef]

- Ameer, K.; Shahbaz, H.M.; Kwon, J.H. Green Extraction Methods for Polyphenols from Plant Matrices: A Review. Food Chem.2017, 241, 275–288. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, M. Polyphenol-Based Differentiation of Botanical Origins of Honey Using LC–MS and Multivariate Analysis. Food Chem.2021, 345, 128864. [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, E.; De Marco, I. Supercritical Fluid Extraction and Fractionation of Natural Matter. J. Supercrit. Fluids2006, 38, 146–166. [CrossRef]

- Socas-Rodríguez, B.; Torres-Cornejo, M.V.; Álvarez-Rivera, G.; Mendiola, J.A. Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources and Agricultural By-Products. Food Bioprod. Process.2021, 130, 260–280. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S.P.M.; e Silva, F.A.; Quental, M.V.; Mondal, D.; Freire, M.G.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Ionic-Liquid-Mediated Extraction and Separation Processes for Bioactive Compounds: Past, Present, and Future Trends. Chem. Rev.2017, 117, 6984–7052. [CrossRef]

- Keremedchieva, R.; Svinyarov, I.; Bogdanov, M.G. Ionic Liquid-Based Aqueous Biphasic Systems—A Facile Approach for Ionic Liquid Regeneration from Crude Plant Extracts. Processes2015, 3, 769–778. [CrossRef]

- Tzima, K.; Brunton, N.P.; Rai, D.K.Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Polyphenols in Lamiaceae Plants—A Review.Plants2018, 7, 25. [CrossRef]

- Oszmiański, J.; Wojdyło, A.; Gorzelany, J.; Kapusta, I. Identification of Low-Molecular-Weight Polyphenols in Berry Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem.2011, 59, 12830–12835. [CrossRef]

- Rohloff, J. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds Using GC–MS-Based Profiling. Molecules2015, 20, 3431–3462. [CrossRef]

- De Rosso, M.; Colomban, S.; Flamini, R.; Navarini, L. UHPLC-ESI-QqTOF-MS/MS characterization of minor chlorogenic acids in roasted Coffea arabica. J. Mass Spectrom.2018, 53, 763–771. [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, D.J.; Arroyo-Hernández, M.; Posada-Ayala, M.; Santos, C. High content of quercetin and catechin in Airén grape juice supports its application in functional food production. Foods2021, 10, 1532. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tan, H.; Meng, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, S. Accumulation Patterns and Condensation Mechanism of Proanthocyanidins in Camellia sinensis. Sci. Rep.2015, 5, 8742. [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, M.D.L.M.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Jáuregui, O.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Determination of flavonoids in citrus fruit extracts by LC-DAD and LC-MS. Food Chem.2007, 101, 1742–1747.

- Tan, W.; Xu, M.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zou, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Q.Anthocyanin Profiles in Grape Berry Skins of Different Species of Wine Grapes in Shanxi, China.Phyton2021, 90, 553–566. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Guo, H.; Xu, W.B.; Ge, J.; Li, X.; Alimu, M.; He, D.J. Rapid Identification of Flavonoids from Raspberry Leaves by HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. Sci.2016, 54, 805–810. [CrossRef]

- Sitarek, P.; Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sikora, J.; Osicka, W.; Śpiewak, I.; Picot, L.; Kowalczyk, T. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Theobroma cacao L.: Insights from In Vitro, In Vivo, and Nanoparticle Studies on Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Effects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1376. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, J.; Yu, B.; Ren, C.; Yan, T.; Jia, Y.; He, B.LC–MS/MS-Based Chemical Profiling of Water Extracts of Moringa oleifera Leaves and Pharmacokinetics of Their Major Constituents in Rat Plasma.Food Chem. X2024, 23, 101585. [CrossRef]

- Rusalepp, L.; Raal, A.; Puessa, T.; Mäeorg, U. Chemical Composition of Hypericum Species. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.2017, 73, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Mbedzi, D.T. Development of LC–MS Techniques for Differentiation of Plant-Derived Isomers; Ph.D. Thesis, 2023.

- Aboushanab, S.A.; Shevyrin, V.A.; Melekhin, V.V.; Andreeva, E.I.; Makeev, O.G.; Kovaleva, E.G. Cytotoxic activity and phytochemical screening of eco-friendly extracted flavonoids from Pueraria montana var. lobata and Trifolium pratense flowers using HPLC-DAD-MS/HRMS. AppliedChem2023, 3, 119–140.

- Ancillotti, C.; Ciofi, L.; Pucci, D.; Sagona, E.; Giordani, E.; Biricolti, S.; Del Bubba, M. Polyphenolic profiles and antioxidant and antiradical activity of Italian berries from Vaccinium myrtillus and Vaccinium uliginosum. Food Chem.2016, 204, 176–184.

- López-Gutiérrez, N.; Romero-González, R.; Plaza-Bolaños, P.; Vidal, J.L.M.; Frenich, A.G. Identification of Phytochemicals in Nutraceuticals Using UHPLC–Orbitrap–MS. Food Chem.2015, 173, 607–618. [CrossRef]

- Velamuri, R.; Sharma, Y.; Fagan, J.; Schaefer, J.Application of UHPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS in Phytochemical Profiling of Sage (Salvia officinalis) and Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis).Planta Med. Int. Open2020, 7, e133–e144. [CrossRef]

- González-de-Peredo, A.V.; Vázquez-Espinosa, M.; Carrera, C.; Espada-Bellido, E.; Ferreiro-González, M.; Barbero, G.F.; Palma, M. Rapid UHPLC–PDA Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Flavonols in Onions. Pharmaceuticals2021, 14, 310. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yin, P.; Cao, X.; Liu, Y.Screen for Potential Candidate Alternatives of Sargentodoxa cuneata from Its Six Adulterants Based on Their Phenolic Compositions and Antioxidant Activities.Int. J. Mol. Sci.2019, 20, 5427. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Li, H.Citrus Flavonoids Characterized by LC–MS/MS.Food Chem.2021, 343, 128399. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.S.; Rodrigues, M.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Silva, A.M.; Pintado, M.M.; Castro, P.M.L. Effects of Phenolic-Rich Extracts on Oxidative Stress and Caco-2 Cells. Nutrients2024, 16, 1361. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, A.; Engelhardt, U.H.; Lakenbrink, C.; Winterhalter, P. Preparative separation of polyphenols from tea by high-speed countercurrent chromatography. J. Agric. Food Chem.2000, 48, 3425–3430.

- Ristivojević, P.; Dimkić, I.; Guzelmeric, E.; Trifković, J. Profiling of Turkish Propolis Subtypes: Comparative Evaluation of Their Phytochemical Compositions, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. LWT2018, 95, 367–379. [CrossRef]

- Pobiega, K.; Kot, A.M.; Przybył, J.L.; Synowiec, A.; Gniewosz, M. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Propolis. Molecules2023, 28, 6744. [CrossRef]

- Paun, N.; Botoran, O.R.; Niculescu, V.C. Total Phenolics, Anthocyanins HPLC–DAD–MS Determination and Antioxidant Capacity in Black Grape Skins and Blackberries: A Comparative Study. Appl. Sci.2022, 12, 936. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; She, Z.; Peng, M.; Yang, Q.; Huang, T.Determining the Adsorption and Desorption Properties of Flavonoids Found in Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. Leaves Using Macroporous Resin and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor Screening.BioResources2021, 16, 470–491. [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Zhang, L. Adsorption/Desorption Characteristics and Chromatographic Purification of Polyphenols from Vernonia patula. Ind. Crops Prod.2021, 170, 113729. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Tovar, P.R.; Pérez-Manríquez, J.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S.; Escalona, N.; Pérez-Correa, J.R. Adsorption of Low-Molecular-Weight Food-Relevant Polyphenols on Cross-Linked Agarose Gel. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 346, 117972. [CrossRef]

- Nasiru, M.M.; Sun, Y.E.; Zhao, L.; et al. Isolation and Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenols from Cynanchum auriculatum. Separations2024, 11, 11. [CrossRef]

- Man, G.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Xu, Z. Phenolic Profiling of Pomegranate Peel by UHPLC–QTOF–MS and UPLC–QQQ–MS. Front. Nutr.2022, 8, 807447. [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.C.; Mariutti, L.R.B. Analysis of Anthocyanins: Extraction, Quantification, and Identification. In Food Chemistry: Basic Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 353–368. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, H.D.; Boffo, E.F. Coffee beyond the cup: Analytical techniques used in chemical composition research—A review. Eur. Food Res. Technol.2021, 247, 749–775.

- Tian, Y.; Liimatainen, J.; Puganen, A.; Alakomi, H.-L.; Sinkkonen, J.; Yang, B.Sephadex LH-20 Fractionation and Bioactivities of Phenolic Compounds from Extracts of Finnish Berry Plants.Food Res. Int.2018, 113, 115–130. [CrossRef]

- Tenório, C.J.L.; Dantas, T.D.S.; Abreu, L.S.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Soares, L.A.L.Influence of Major Polyphenols on the Anti-Candida Activity of Eugenia uniflora Leaves: Isolation, LC–ESI–HRMS/MS Characterization and In Vitro Evaluation.Molecules2024, 29,2761. [CrossRef]

- Hazli, U.H.A.M.; Hwong, C.S.; Abdul-Aziz, A.; Mat-Junit, S.; Leong, K.H.; Kong, K.W. Identification of Phytochemicals in Alternanthera sessilis Extracts Using HPLC–QTOF–MS/MS. S. Afr. J. Bot.2022, 151, 440–450. [CrossRef]

- Susanti, I.; Pratiwi, R.; Rosandi, Y.; Hasanah, A.N.Separation Methods of Phenolic Compounds from Plant Extracts.Plants2024, 13, 965. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Guo, X.-H.; Wang, S.-S.; Li, Y.-Q.; Li, G.-Z.; Zhao, W.-J. Screening and identification of natural ligands of tyrosinase from Pueraria lobata by ultrafiltration LC-MS. Anal. Methods2017, 9, 4858–4862. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-S.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Yin, J.-T.; Kong, D.-Z.; Li, D.-Q.Screening and Identification of Potential Tyrosinase Inhibitors from Semen Oroxyli Extract by Ultrafiltration LC–MS and In Silico Molecular Docking.J. Chromatogr. Sci.2019, 57, 838–846. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Xia, L.; Xiao, H. Screening of α-glucosidase inhibitors from green tea using immobilized enzyme affinity capture combined with UHPLC-QTOF-MS. Chem. Commun.2014, 50, 2582–2584. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, R.; Hu, X.; Li, C.; Wang, L. Bio-Affinity Ultrafiltration Combined with HPLC–QTOF–MS/MS for Screening α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. Food Chem.2022, 373, 131528. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, H.; Gong, M.; Han, L. Bioaffinity Ultrafiltration Coupled with HPLC–ESI–MS/MS for Screening Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors from Pomegranate Peel. Front. Nutr.2022, 9, 1014862. [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Bu, F.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, C.; Yin, Y.; Liu, P. Purification of phenolics from Plantago depressa by macroporous resin: Adsorption/desorption characteristics and UPLC-TQ-MS/MS analysis. LWT2024, 203, 116405. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, S.; Ren, X.; Li, M. Purification of Polyphenols from Kiwi Fruit Peel Extracts Using Macroporous Resins. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.2018, 53, 1486–1495. [CrossRef]

- Mottaghipisheh, J.; Iriti, M. Sephadex® LH-20 for Isolation and Purification of Flavonoids. Molecules2020, 25, 4146. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, L.R.; Kirkland, J.J.; Dolan, J.W.Introduction to Modern Liquid Chromatography; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011.

- Niculau, E.S.; Oliveira, D.A.; Almeida, N.F. Preparative HPLC for Isolation of Natural Compounds. Sep. Sci. Plus2022, 5, 602–615. [CrossRef]

- Hostettmann, K.; Marston, A.; Hostettmann, M.; Hamburger, M. Preparative Chromatography Techniques: Applications in Natural Product Isolation; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998.

- D’Archivio, M.; Filesi, C.; Di Benedetto, R.; Gargiulo, R.; Giovannini, C.; Masella, R. Polyphenols, dietary sources and bioavailability. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita2010, 46, 348–361.

- Clifford, M.N.; Johnston, K.L.; Knight, S.; Kuhnert, N. Hierarchical scheme for LC-MSⁿ identification of chlorogenic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem.2017, 65, 1330–1339.

- Chang, C.; Yang, M.; Wen, H.; Chern, J. Estimation of Total Flavonoid Content by Two Complementary Colorimetric Methods. J. Food Drug Anal.2002, 10, 178–182.

- Francioso, A.; Mastromarino, P.; Masci, A.; d’Erme, M.; Mosca, L. Chemistry, Stability and Bioavailability of Resveratrol. Med. Chem.2014, 10, 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Flamini, R.; Mattivi, F.; De Rosso, M.; Arapitsas, P.; Bavaresco, L. Advanced Knowledge of Three Important Classes of Grape Phenolics: Anthocyanins, Stilbenes and Flavonols. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2013, 14, 19651–19669. [CrossRef]

- Mattivi, F.; Guzzon, R.; Vrhovsek, U.; Stefanini, M.; Velasco, R. Metabolite Profiling of Grape: Flavonols and Anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem.2006, 54, 7692–7702. [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Anthocyanins: Characterization by UV–Visible and Mass Spectrometry. In Handbook of Food Analytical Chemistry; Wrolstad, R.E.; Acree, T.E.; Decker, E.A.; Penner, M.H.; Reid, D.S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Shoemaker, C.F.; Smith, D.; Sporns, P., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 19–31.

- Keskin, N.; Kunter, B. Stilbenes Profile in Various Tissues of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Ercis’). J. Environ. Prot. Ecol.2017, 18, 1259–1267.

- Cheynier, V.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Yoshida, K. Polyphenols: From Plants to a Variety of Food and Nonfood Uses. J. Agric. Food Chem.2015, 63, 7589–7594. [CrossRef]

- Košir, I.J.; Lapornik, B.; Andrenšek, S.; Golc Wondra, A.; Vrhovšek, U.; Kidrič, J. Identification of Anthocyanins in Wines by Liquid Chromatography, Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Anal. Chim. Acta2004, 513, 277–282. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Warner, R.D.; Shen, S.; Johnson, S.K.; Fang, Z. Comprehensive Profiling of Phenolic Compounds by HPLC–DAD–ESI–QTOF–MS/MS to Reveal Their Location and Form of Presence in Different Sorghum Grain Genotypes. Food Res. Int.2022, 137, 109671. [CrossRef]

- Temerdashev, A.; Atapattu, S.N.; Pamunuwa, G.K. Determination and Identification of Polyphenols in Wine Using Mass Spectrometry Techniques. J. Chromatogr. Open2024, 6, 100175.

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Neveu, V.; Vos, F.; Scalbert, A. Identification of the 100 Richest Dietary Sources of Polyphenols: An Application of the Phenol-Explorer Database. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.2010, 64 (Suppl. 3), S112–S120. [CrossRef]

- Borrás-Linares, I.; Stojanović, Z.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Arráez-Román, D.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Rosmarinus officinalis Leaves as a Natural Source of Bioactive Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2014, 15, 20585–20606. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, M.; Li, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, M.; Li, X.; Qi, X.; Bai, X.; Chai, Y. Development of Matrix Certified Reference Material for Accurate Determination of Docosahexaenoic Acid in Milk Powder. Food Chem.2023, 406, 135012. [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, P.; Ko, Y.T. Validated LC–MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Resveratrol Levels in Mouse Plasma and Brain and Its Application to Pharmacokinetic and Brain Distribution Studies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.2016, 119, 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, L.; García-Campa, E.; González-Rodríguez, M.V.; Rodríguez-Méndez, M.L. Development of an LC–MS/MS Method for the Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Honey Samples. Foods2021, 10, 2616. [CrossRef]

- Pieczykolan, A.; Pietrzak, W.; Dos Santos Szewczyk, K.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Nowak, R. LC–ESI–MS/MS Polyphenolic Profile and In Vitro Study of Cosmetic Potential of Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. Herb Extracts. Molecules2022, 27, 1259. [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Nikolaou, A.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Alexopoulos, A.; Dasenaki, M.; Mastrotheodoraki, A.; Proestos, C.; Thomaidis, N.; Plessas, S. Chemical Profile Characterization of Fruit and Vegetable Juices after Fermentation with Probiotic Strains. Foods2024, 13, 1136. [CrossRef]

- Chira, K.; Anguellu, L.; Da Costa, G.; Richard, T.; Pedrot, E.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.-L. New C-Glycosidic Ellagitannins Formed upon Oak Wood Toasting: Identification and Sensory Evaluation. Foods2020, 9, 1477. [CrossRef]

- Wolfender, J.-L.; Nuzillard, J.-M.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Renault, J.-H.; Bertrand, S. Accelerating Metabolite Identification in Natural Product Research: Toward an Ideal Combination of Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry and NMR Profiling, In Silico Databases, and Chemometrics. Anal. Chem.2019, 91, 704–742. [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Yanase, E. Study into the Chemical Changes of Tea Leaf Polyphenols during Japanese Black Tea Processing. Food Res. Int.2022, 160, 111731. [CrossRef]

- Palade, L.M.; Croitoru, C.; Albu, C.; Radu, G.L.; Popa, M.E. Identification of Tentative Traceability Markers with Direct Implications in Polyphenol Fingerprinting of Red Wines: Application of LC–MS and Chemometrics Methods. Separations2021, 8, 233. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Yeo, J. Bioactivities of Phenolics by Focusing on Suppression of Chronic Diseases: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2018, 19, 1573. [CrossRef]

- Faccin, H.; Viana, C.; do Nascimento, P.C.; Bohrer, D.; de Carvalho, L.M. Study of ion suppression for phenolic compounds in medicinal plant extracts using liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A2016, 1427, 111–124. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol.2010, 1, 163–187. [CrossRef]

- Niessen, W.M.A.; Manini, P.; Andreoli, R. Matrix effects in quantitative pesticide analysis using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev.2006, 25, 881–899. [CrossRef]

- Motilva, M.J.; Serra, A.; Macià, A. Analysis of Food Polyphenols by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry: An Overview. J. Chromatogr. A2013, 1292, 66–82. [CrossRef]

- Vrhovšek, U.; Rigo, A.; Tonon, D.; Mattivi, F. Quantitation of Polyphenols in Different Apple Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem.2004, 52, 6532–6538. [CrossRef]

- Infante, R.; Infante, M.; Pastore, D.; Pacifici, F.; Chiereghin, F.; Malatesta, G.; Donadel, G.; Tesauro, M.; Della-Morte, D. An Appraisal of the Oleocanthal-Rich Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) and Its Potential Anticancer and Neuroprotective Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2023, 24, 17323. [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission. European Pharmacopoeia, 10th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2021; General Chapters 2.2 and 5.26.

- European Commission. Guidance Document on Analytical Quality Control and Method Validation Procedures for Pesticide Residues Analysis in Food and Feed (SANTE/11312/2021); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Cortese, M.; Pinto, G.; Fanali, S.; Dugo, P. Compensate for or Minimize Matrix Effects? Strategies for Achieving Best Results in LC–MS Analysis. Molecules2020, 25, 3047. [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Encapsulation, Protection, and Delivery of Bioactive Proteins and Peptides Using Nanoparticle and Microparticle Systems: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci.2018, 253, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Draelos, Z.D. Cosmetics and Dermatologic Problems and Solutions; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011.

- McClements, D.J.; Li, F.; Xiao, H. The Nutraceutical Bioavailability Classification Scheme: Classifying Nutraceuticals According to Factors Limiting Their Oral Bioavailability. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol.2015, 6, 299–327. [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.-M.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Wolfender, J.-L. Deep Metabolome Annotation in Natural Products Research: Towards a Virtuous Cycle in Metabolite Identification. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.2017, 36, 40–49. [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Shahidi, F.; Wrolstad, R.; Kilmartin, P.A.; Melton, L.D.; Hidalgo, F.J.; Finglas, P.; et al. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolics and Flavonoids Contents: Should We Ban In Vitro Screening Methods? Food Chem.2018, 264, 471–475. [CrossRef]

- Rein, M.J.; Renouf, M.; Cruz-Hernandez, C.; Actis-Goretta, L.; Thakkar, S.K.; da Silva Pinto, M. Bioavailability of Bioactive Food Compounds: A Challenging Journey to Bioefficacy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.2013, 75, 588–602. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).