1. Introduction

The Wind and photovoltaic power have rapidly developed as dominant renewable energy sources in recent years. Large-scale renewable energy clusters are being deployed across Northwest, North, and Northeast China, typically developed in a centralized manner and transmitted over long distances via ultra-high voltage direct current (UHVDC) lines. Meanwhile, offshore wind power along the eastern coast is expanding rapidly. However, the inherent variability of wind and solar resources often leads to voltage fluctuations within these clusters. For example, in 2022, a collection station in Jiangsu serving eight wind farms experienced voltage oscillations. In 2024, a photovoltaic station in Tianjin encountered severe inter-station reactive power imbalance, repeated high-voltage ride-through events, and inverter power oscillations, primarily due to inadequate AVC settings and blocking strategies. Furthermore, blackout events in Spain and Portugal have demonstrated that large-scale renewable integration significantly exacerbates voltage stability challenges.

To improve the reactive power and voltage regulation of renewable clusters, targeted research on coordinated transient-stability AVC strategies and simulation verification is therefore needed. Such work must be grounded in real grid scenarios involving abnormal voltage fluctuations, while considering renewable generation characteristics, local grid architecture, and operational constraints. Reference [

1] systematically reviews key smart grid voltage control challenges, such as high renewable penetration, and outlines future research directions. As a core optimization tool, optimal power flow (OPF) is essential. Reference [

2] surveys advanced OPF techniques, including AI applications, providing a methodological foundation. Transmission system voltage control focuses on wide-area coordination. Reference [

3] proposes a decentralized wide-area secondary voltage control scheme using phasor measurement units. Reference [

4] enhances conventional secondary control via grid structural analysis. Reference [

5] investigates tertiary voltage control automation, reflecting the trend toward fully automated management. Distribution network voltage control is highly active due to the high penetration of distributed energy resources. Reference [

6] designs a distributed coordination strategy for DGs and tap changers using model predictive control. References [

7,

8] propose multi-objective hierarchical volt/var control frameworks for active distribution networks, with [

8] detailing a cooperative multi-timescale mechanism. Reference [

9] presents a multi-timescale reactive power optimization method. Reference [

10] introduces an innovative “Volt-PF” control mode for feeder management. Reference [

11] optimizes local control by coordinating multiple inverter droop functions. Reference [

12] designs a hierarchical distributed-local control strategy for PV clusters. Reference [

13] proposes an adaptive voltage control method using a measurement-strategy mapping matrix. To address PV uncertainty, Reference [

14] studies adaptive control for large-scale PV plants. Reference [

15] earlier proposed a three-stage robust inverter-based volt/var control framework. Reference [

16] introduces an affinely adjustable robust control method that operates without centralized computations. From a planning perspective, Reference [

17] investigates optimal placement of reactive power compensation devices.

Offshore wind power integration presents unique challenges. Reference [

18] studies collection system topology optimization for deep-sea farms. Reference [

19] explores the fault ride-through and voltage support of grid-forming turbines in MMC-HVDC systems. For reactive power control, Reference [

20] proposes a double-layer optimization method using an improved gravitational search algorithm. Reference [

21] assesses coordinated utilization of wind farm reactive power capability. Reference [

22] evaluates the impact of large-scale offshore wind integration, including on voltage stability.

Analytical tools, metrics, and validation platforms are crucial for effective control. Reference [

23] introduces a classical approach using sensitivity analysis and QV curves. Reference [

24] employs a data-driven method to determine the Q–V characteristics of wind farms. Reference [

25] studies cost optimization of dynamic reactive power services with DFIG-based farms. Reference [

26] implements decentralized Q control for PV using the IEC 61850 GOOSE protocol. Reference [

27] provides an early framework for wide-area voltage monitoring. With increasing power electronics, system strength has become critical. References [

28,

29] propose the Generalized Operational Short-Circuit Ratio and the Complex Short Circuit Ratio, respectively, offering precise metrics for grid robustness. Reference [

30] presents a real-time hardware-in-the-loop testbed for developing coordinated control systems. The above works, however, have not conducted in-depth research on the voltage oscillation problem specific to large-scale renewable energy clusters, nor on corresponding strategy improvement and verification methods.

Accordingly, this paper investigates voltage oscillations encountered in practical grid operation. A representative case is developed to reproduce such phenomena. We propose a hierarchical multi-mode coordinated reactive-voltage control strategy for renewable energy clusters, along with an associated verification methodology. The main contributions are summarized as follows.

We enhance the conventional voltage control framework by introducing a coordinated reactive power and voltage control layer. The control roles of different renewable plants within the cluster are defined. Dynamic adjustment guidelines for control modes—including constant voltage, constant reactive power, and constant power factor—are also provided.

A designed renewable energy cluster scenario is analyzed. Sensitivity variations under different grid operating modes are characterized. An improved short-circuit ratio (SCR) is formulated and incorporated as an optimization constraint. This integration enhances both voltage quality and system strength, ensuring stable grid integration.

A multi-agent verification framework is established. We introduce a renewable energy simulation model suitable for large-system studies. Using a combined hardware-in-the-loop and digital simulation platform, voltage oscillations under high renewable penetration are replicated. The adoption of RMS-based simulation offers a computationally efficient and cost-effective validation approach for this category of control problems.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the voltage sensitivity analysis method and presents Q-V curve characteristics.

Section 3 introduces an improved short-circuit ratio index to quantify active-reactive power interactions.

Section 4 details the coordinated optimization control strategy, incorporating multi-scale indices to address both small-signal and large-disturbance characteristics.

Section 5 presents the verification framework and demonstrates voltage oscillation suppression.

Section 6 concludes.

2. Voltage Sensitivity Analysis of Renewable Energy Clusters

Sensitivity analysis constitutes an essential analytical approach in reactive power and voltage control. Based on a linearized system model derived at a steady-state operating point, it captures the sensitivity of bus voltages to variations in reactive power injection or absorption. This interaction is commonly represented by the sensitivity matrix ∂V/∂Q, a critical component for designing effective control actions to support voltage profiles and improve system stability. In contemporary power grids, particularly with renewable energy clusters, V-Q sensitivity analysis aids in evaluating grid strength, locating vulnerable buses, and optimizing the dispatch of reactive power resources. The adaptive implementation of this method enhances estimation accuracy across diverse operating states, thereby enabling more responsive and dependable voltage regulation in real-time operational frameworks. The widely adopted Newton-Raphson technique, which solves the power flow equations, supplies the numerical basis for computing these sensitivities with high fidelity. Its property of quadratic convergence renders it especially effective for analyzing large-scale alternating-current networks.

Let the voltage magnitude be

Vm and the phase angle be

θ. The complex node voltage is expressed as:

where

Vm,i is the voltage magnitude (p.u.) at node

i.

θi is the voltage phase angle (in radians) at node

i.

The voltage vector for all nodes is:

The node admittance matrix and power injection are given by:

Where Ybus is the node admittance matrix and the ∗ denotes the complex conjugate.

The Jacobian matrix is composed of partial derivatives of power with respect to voltage:

where

P is the active power vector, the vaule is Re(

S).

Q is the reactive power vector, the value is Im(

S).

The voltage magnitudes of slack and PV nodes are fixed, and the phase angle of the slack node is fixed. After remove the rows and columns corresponding to fixed variables, the retained variables are the phase angles and voltage magnitudes of PQ nodes:

The reduced Jacobian matrix is:

where PQ is set of PQ nodes.

Apply a unit reactive power perturbation at each PQ node k.

where the

k-th element is 1.

Solve the linear system:

where Δ

QPQ,k is the part of Δ

Qk corresponding to PQ nodes.

Combine the sensitivities for all PQ nodes:

The columns corresponding to non-PQ nodes are zero. Sensitivities between PQ nodes are given by the corresponding submatrix of inv(Jred).

For renewable energy clusters, QV curves can be derived at various steady-state points. This method is widely used for voltage instability assessment. It characterizes how much reactive power is needed to maintain voltage under changing load. A key insight from the QV curve is its slope, dQ/dV: a positive slope indicates voltage stability at that operating point, whereas a zero or negative slope signals proximity to or breach of the stability limit. Thus, the slope directly expresses local voltage sensitivity. QV curves help pinpoint the most vulnerable buses for targeted compensation. Industry standards such as the WECC voltage stability criteria (1999) formalize the use of QV-based metrics. By setting appropriate dQ/dV thresholds and comparing them with real-time measurements, system operators can continuously evaluate voltage stability and initiate preventive controls when necessary.

3. Improved Short-Circuit Ratio Calculation Method Applicable to Renewable Energy Clusters

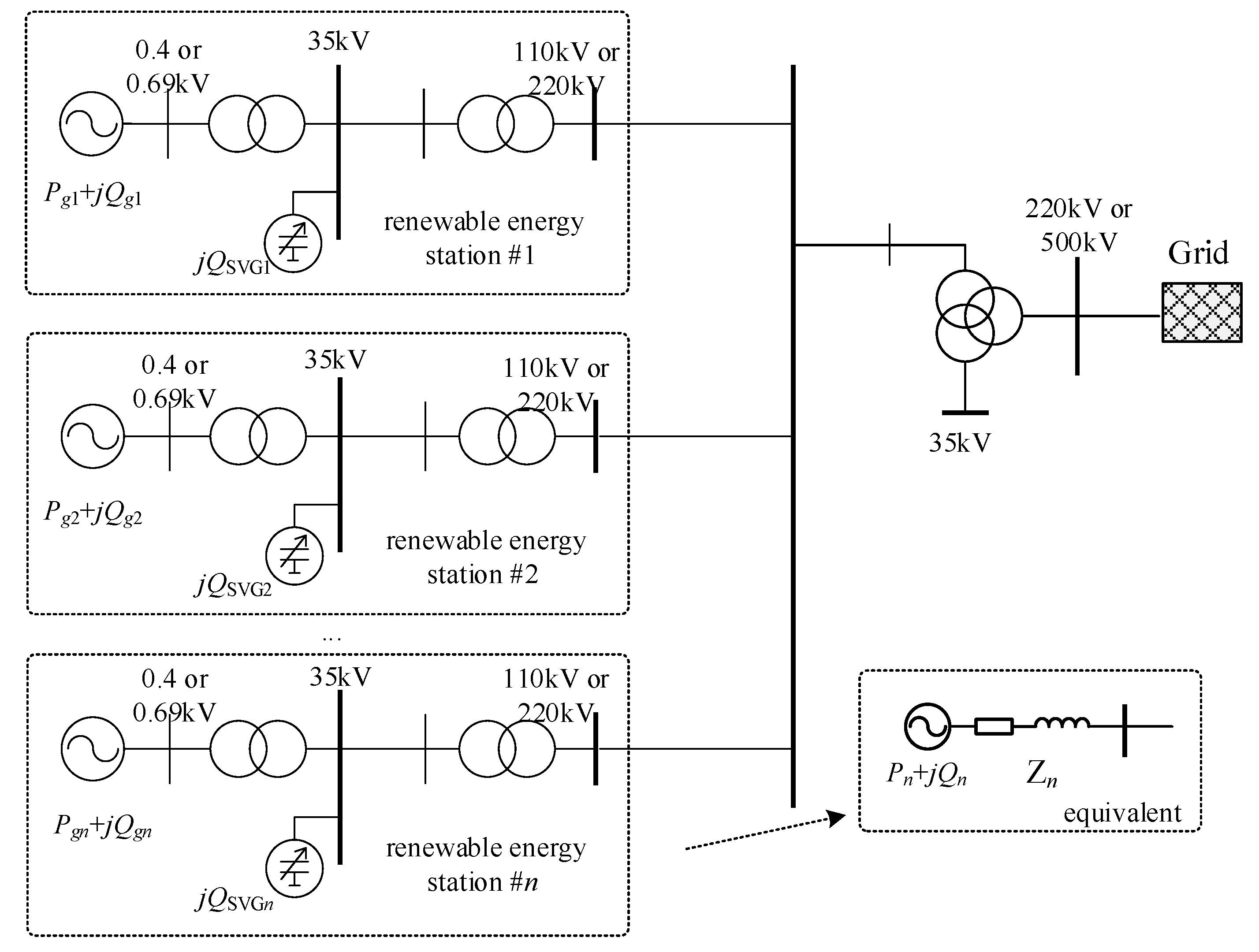

A typical renewable energy cluster is shown in the figure below. The voltage stability of such a cluster is closely related to the short-circuit ratio at its grid connection point. While section 2 adopted a voltage-sensitivity perspective, this section shifts focus to evaluating these clusters using short-circuit ratio indices. It also serves as a key indicator for assessing the grid voltage’s susceptibility to oscillation.

Figure 1.

A typical renewable energy cluster.

Figure 1.

A typical renewable energy cluster.

The CIGRE Working Group B4.62 has conducted a systematic review of prevalent methodologies for weak grid assessment in power systems engineering and has developed a dedicated framework for evaluating the grid interconnection strength of individual wind farms. The report details several established short-circuit ratio (SCR) calculation techniques, including the Composite Short-Circuit Ratio (CSCR), the Weighted Short-Circuit Ratio (WSCR), and the Equivalent Short-Circuit Ratio (ESCR). These methods rely exclusively on network parameters while intentionally omitting the characteristics of specific power electronic converter devices, thereby ensuring high practicality for engineering applications.

Among these, the WSCR serves as a key metric for quantifying the aggregate grid strength of a renewable energy cluster. This indicator has been applied in operational practice, notably within the Texas power system, to support the determination of power transfer limits for inverter-based resources across critical transmission interfaces. The WSCR is expressed as follows:

where

Ski is the short-circuit capacity of renewable energy power station

i;

Pi is the active output of the renewable energy power station

i; n is the number of renewable energy power stations.

The fundamental principle of the Composite Short-Circuit Ratio (CSCR) involves modeling the entire generation cluster as a single equivalent source connected to a virtual common coupling point. The CSCR is defined as the ratio of the short-circuit capacity (

Sk) at this point to the total active power output of the cluster, as given by the formula:

where

Sk,eq is the short-circuit capacity of the renewable energy cluster aggregation equivalent system at the virtual public grid connection point.

The calculation methodology for the Equivalent Short-Circuit Ratio (ESCR) is derived from the concept of the Multi-Infeed Short-Circuit Ratio employed in multi-terminal HVDC systems. Its key advancement lies in the consideration of mutual voltage interactions between distinct stations when assessing the aggregate grid strength. The ESCR is expressed by the following formula:

where

rji is the voltage interaction coefficient between renewable energy power station at node

j and renewable energy power station at node

i.

rji is expressed as follows:

where

Zii is the self-impedance of the renewable energy power station

i;

Zji is the mutual impedance between renewable energy power station at node

j and renewable energy power station at node

i.

In practical systems, nearly all wind and PV plants deploy SVCs or SVGs to compensate for reactive losses. Moreover, most of the inverters are current-source-controlled grid-connected devices and are also susceptible to stability issues under weak grid conditions, making their point-of-connection strength a relevant concern, one not adequately captured by existing ESCR or CSCR methods. An improved approach uses a complex interaction factor that accounts for both impedance angles and initial phase differences between units. It incorporates reactive output

Q by replacing active power

P with apparent power

Ṡ =

P +

jQ in the calculation, resulting in the refined Multi-plant Short-Circuit Ratio (MRSCR), expressed as follows:

An SVG is a power electronic source controlled as a current source and should be treated as an independent source in the MRSCR calculation. Its output comprises only the imaginary part (reactive power). This approach fully accounts for the impact of SVG output on the stability of renewable energy units and the grid strength at the SVG’s own point of connection. Consequently, the number of current sources considered in the MRSCR calculation increases. If reactive power compensation is achieved using the capacity of the renewable energy units themselves, the number of current sources in the MRSCR calculation remains unchanged. However, in this case, the output of each current source includes both the real part (active power) and the imaginary part (reactive power).

4. An Integrated Control Strategy with Voltage-Sensitivity and SCR Constraints

The objective function of the conventional secondary-control optimization model is formulated as:

where α is the gain coefficient; Δ

Qg is the optimization variable, representing the reactive power output of each renewable energy plant. The term

Wp is the weight assigned to the voltage-deviation component, Δ

Vp is the voltage deviation at the pilot bus and

Cg is the voltage-sensitivity matrix. The term

Wq is the weight for the balancing component of the adjustable remaining reactive-power capacity at each plant; The

Qg,

Qg.max, and

Qg.min refer to the current reactive output, upper limit, and lower limit of the renewable energy plant, respectively.

Once the optimal reactive outputs are determined by the secondary control, they are converted into voltage commands via the matrix

Cg for distribution to the substations.

Cg satisfies the following relation:

The equality constraints of the secondary-control optimization model are given by the power-balance equations for all nodes in the region:

where

PGi and

QGi are the active and reactive power outputs of the generator at node

i, respectively;

PLi and

QLi are the active and reactive power demands of the load at node

i, respectively;

Gij and

Bij are the real and imaginary parts of the admittance-matrix element

Yij.

The inequality constraints include limits on the single-step adjustment amount, voltage limits, and substation reactive-power limits, expressed as:

where

Up,

Up.max, and

Up.min denote the current voltage, upper limit, and lower limit at the pilot point, respectively;

UH,

UH.max,

UH.min, and Δ

UH represent the current voltage, upper limit, lower limit, and maximum permissible single-step adjustment for each renewable energy plant, respectively.

Cvg is the reactive-power-voltage sensitivity matrix for each plant, which satisfies:

In the above expression, UH indicates the current voltage at the high-voltage side bus of the generator.

In strongly coupled AVC substations, such as those in renewable energy clusters, an issue can arise when the weight of the voltage-deviation component (Wp) is high relative to the weight of the remaining reactive-power balancing component (Wq). Specifically, after a voltage deviation is corrected, reactive-power balance and fairness are typically pursued by increasing the output of plants with lower reactive loading rates and decreasing that of plants with higher rates. However, the combined adjustments from multiple generators may yield a required adjustment at the plant’s high-voltage bus that is very small, even smaller than the control dead band. Consequently, reactive-power balance and rational power flow cannot be achieved. This problem is especially prominent in regional grids following large-scale integration of renewable energy clusters.

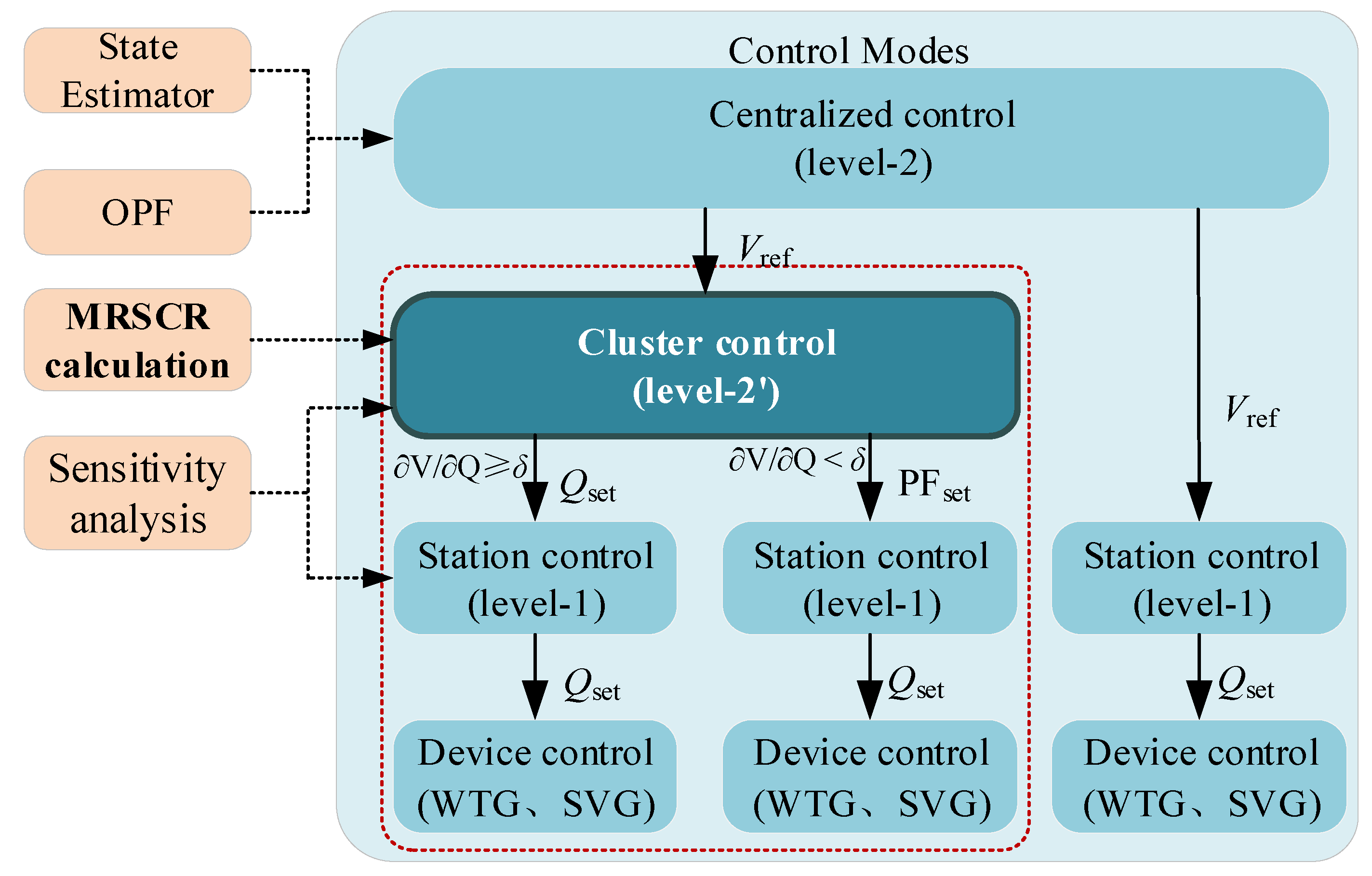

Therefore, this paper proposes a reactive-power-voltage control strategy that incorporates an AVC Coordination Station (level-2’). A substation or switch-station node where multiple power plants (primarily renewable) aggregate is designated as the Coordination Station. Positioned between the AVC Master Station and the renewable-energy AVC Substations, it operates at the local secondary-control level, facilitating reactive-power-voltage interaction.

In this framework, subordinate AVC Substations (level-1) report their remaining adjustable reactive-power capacity to the Coordination Station (level-2’). The AVC Master Station (level-2) performs secondary-voltage-control optimization for the grid area and issues adjustment commands to each conventional substation and the Coordination Station. Based on the topology and real-time reactive outputs of its subordinate substations, the Coordination Station calculates the total required reactive-power adjustment. It then determines and dispatches specific adjustment commands to each subordinate substation for the current control cycle, which are subsequently executed.

The main control modes for the plant-side AVC Substations are defined as follows:

(1) Constant-voltage control mode

The PCC voltage is taken as the control objective. The total reactive power required from the plant is calculated based on the voltage target. This total is allocated to each controlled renewable generation unit or adjustable reactive device (SVG) according to a predefined dispatch strategy, so that the PCC bus voltage reaches the target value. Automatic voltage and reactive-power control for the entire plant is thereby achieved.

(2) Constant-reactive-power control mode

The total reactive power at the PCC is taken as the control objective. The target is allocated to each participating unit or device per the dispatch strategy, ensuring that the total station reactive power meets the setpoint. Automatic voltage and reactive-power control is thus realized.

(3) Constant-power-factor control mode

The power factor at the PCC is taken as the control objective. The required adjustment is allocated to each participating unit or device per the dispatch strategy, so that the total station power factor reaches the target value.

Figure 2.

Framework of the integrated control strategy.

Figure 2.

Framework of the integrated control strategy.

For the plant-side AVC Substations (level-1) under the Coordination Station (level-2’), two categories are defined based on voltage sensitivity: those with high sensitivity are switched to constant-reactive-power control mode, while those with low sensitivity are set to constant-power-factor control mode. The specific thresholds δ can be determined according to the actual grid. AVC Substations not under the Coordination Station’s jurisdiction remain in constant-voltage control mode.

Furthermore, multi-plant short-circuit-ratio (MRSCR) constraints are incorporated. An improved objective function is adopted for the Coordination Station as shown below. By setting the weight of the MRSCR balancing indicator, the short-circuit ratios of the renewable plants under the Coordination Station are guided toward a more balanced state.

where

Wp is the weight of the voltage deviation component for these substations;

Wq is the weight for the balancing component of their adjustable remaining reactive-power capacity;

β is the gain coefficient;

Wscr is the weight of the MRSCR deviation component for these substations;

Cmg is the reactive-power-MRSCR matrix for each plant.

4. Control Strategy Closed-Loop Verification Scheme and Case Analysis

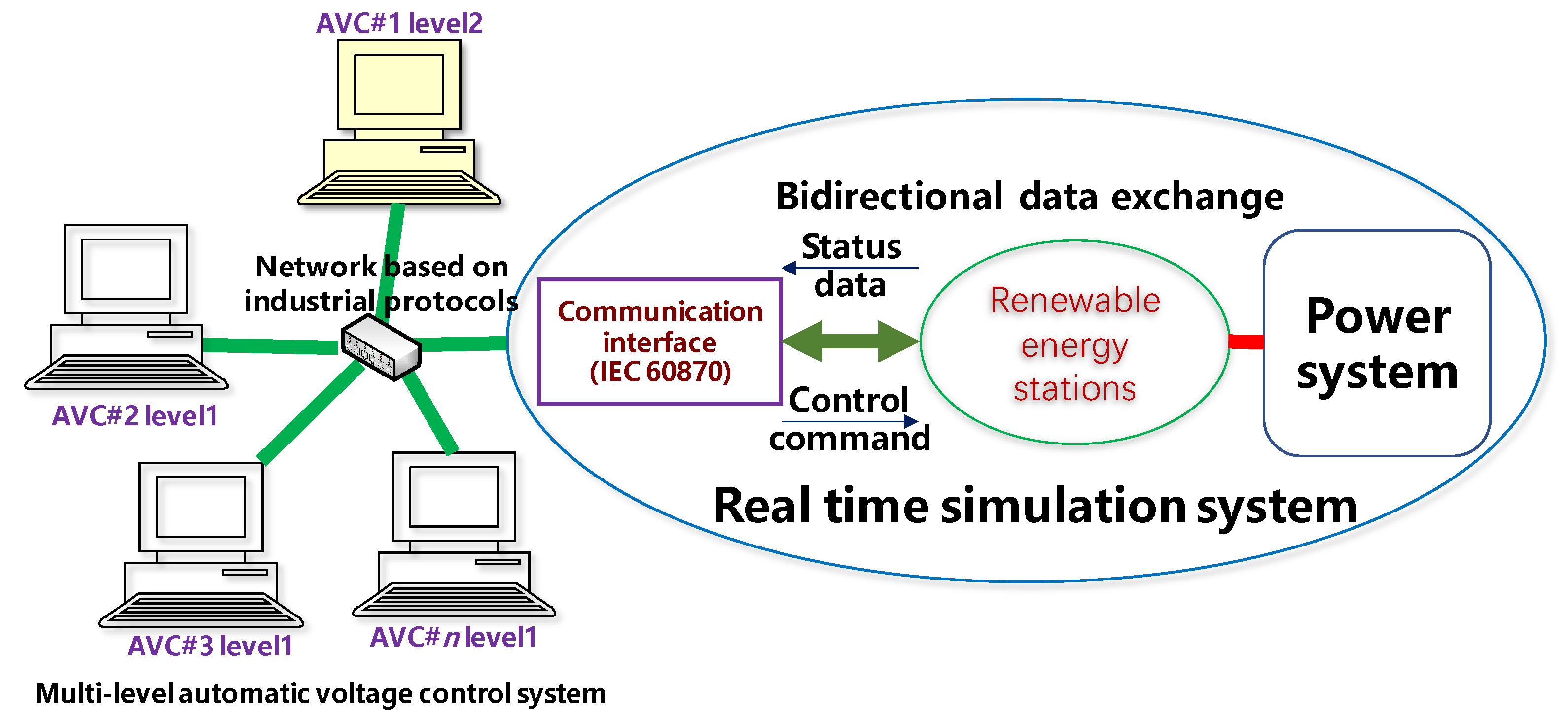

4.1. Closed-Loop Verification Platform for Cluster-Level Control Strategies

While commercial simulation tools (e.g., RTDS, ADPSS, RT-LAB) are widely adopted for electromagnetic-transient analysis of individual renewable energy devices, they exhibit limitations when applied to the study of large-scale, multi-layer reactive-power and voltage control strategies. Such cluster-level control operates on a slower timescale (seconds to minutes), uses RMS-based electrical quantities as control objectives, and requires extensive and bidirectional data exchange with numerous AVC controllers via industrial communication protocols such as IEC 60870-5-104. To address this gap, this paper develops a dedicated real-time RMS-simulation platform for verifying reactive-power and voltage control strategies in renewable energy clusters. The platform simulates the dynamic behavior of the power system and the voltage-regulation capability of renewable plant primary equipment. By integrating actual AVC control hardware through a simulated communication network, it enables closed-loop, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing, where physical controllers interact in real time with digital simulation models.

Figure 3.

Closed-Loop Verification Platform Architecture.

Figure 3.

Closed-Loop Verification Platform Architecture.

The platform architecture decouples the Communication Front-End process from the Real-Time Simulation process via shared memory. The front-end operates in multi-threaded mode, with each IEC 104 communication link handled by a separate thread identified by its IP-port pair. Communication stress tests confirm that a single PC can support the simulation of large-scale clusters. Each renewable plant can be modeled either as an equivalent aggregated unit or as a detailed representation of its internal generation units. Control strategies may be implemented using actual controller hardware—capturing true discrete control behavior—or as digital models, which allow flexible parameter tuning and comparative analysis.

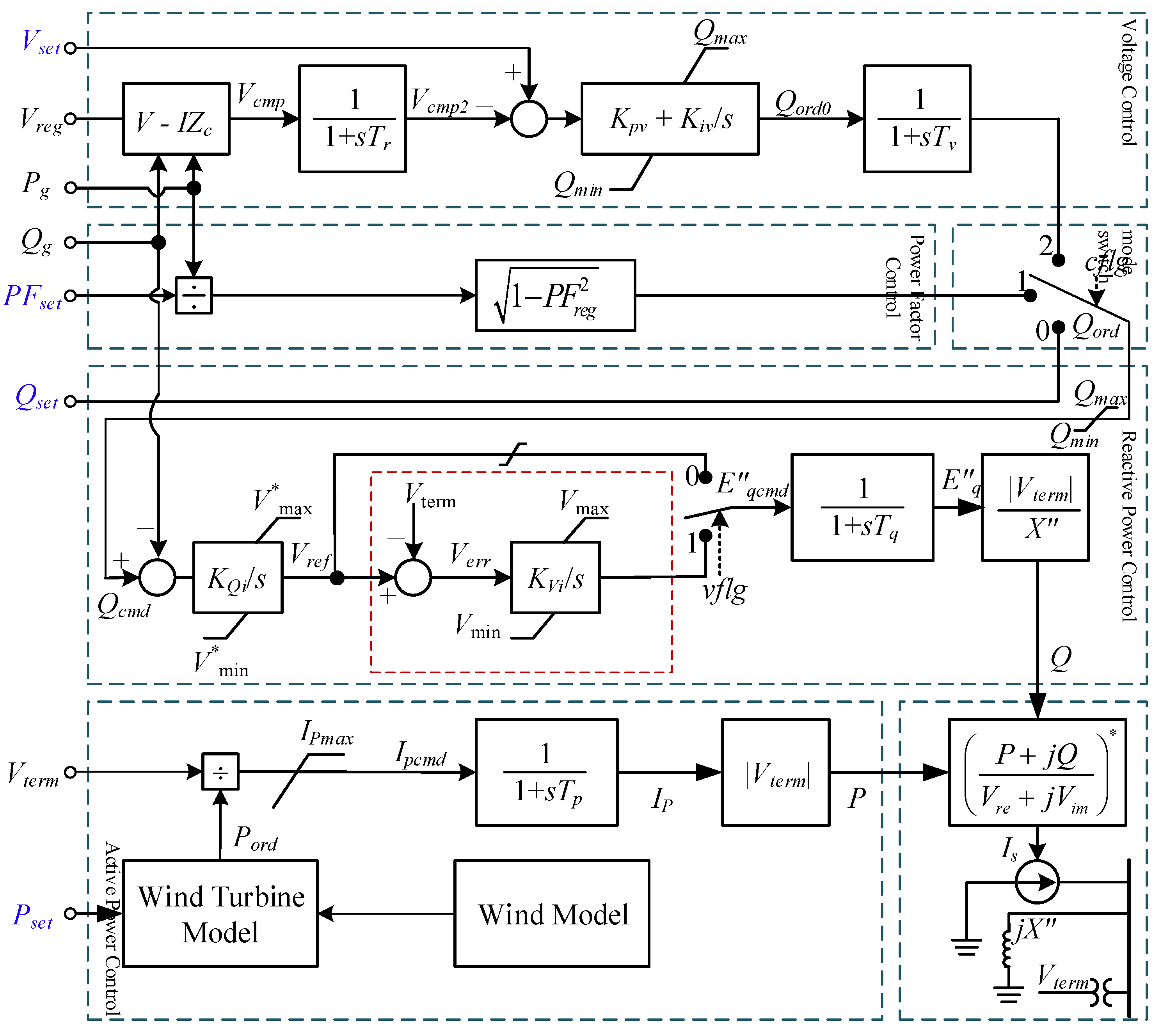

4.2. Generalized Power-Electronic Interface Model for System-Level Studies

For electromechanical transient studies, a renewable energy plant’s grid interface can be abstracted into key functional modules: power-electronic interface, active-power control, reactive-power control and fault-handling blocks. The reactive power and voltage control strategy can be reconfigured as needed by switching the cflg.

Based on different control strategies and their corresponding constant voltage, constant reactive power, and constant power factor control commands such as

Vset Qset and

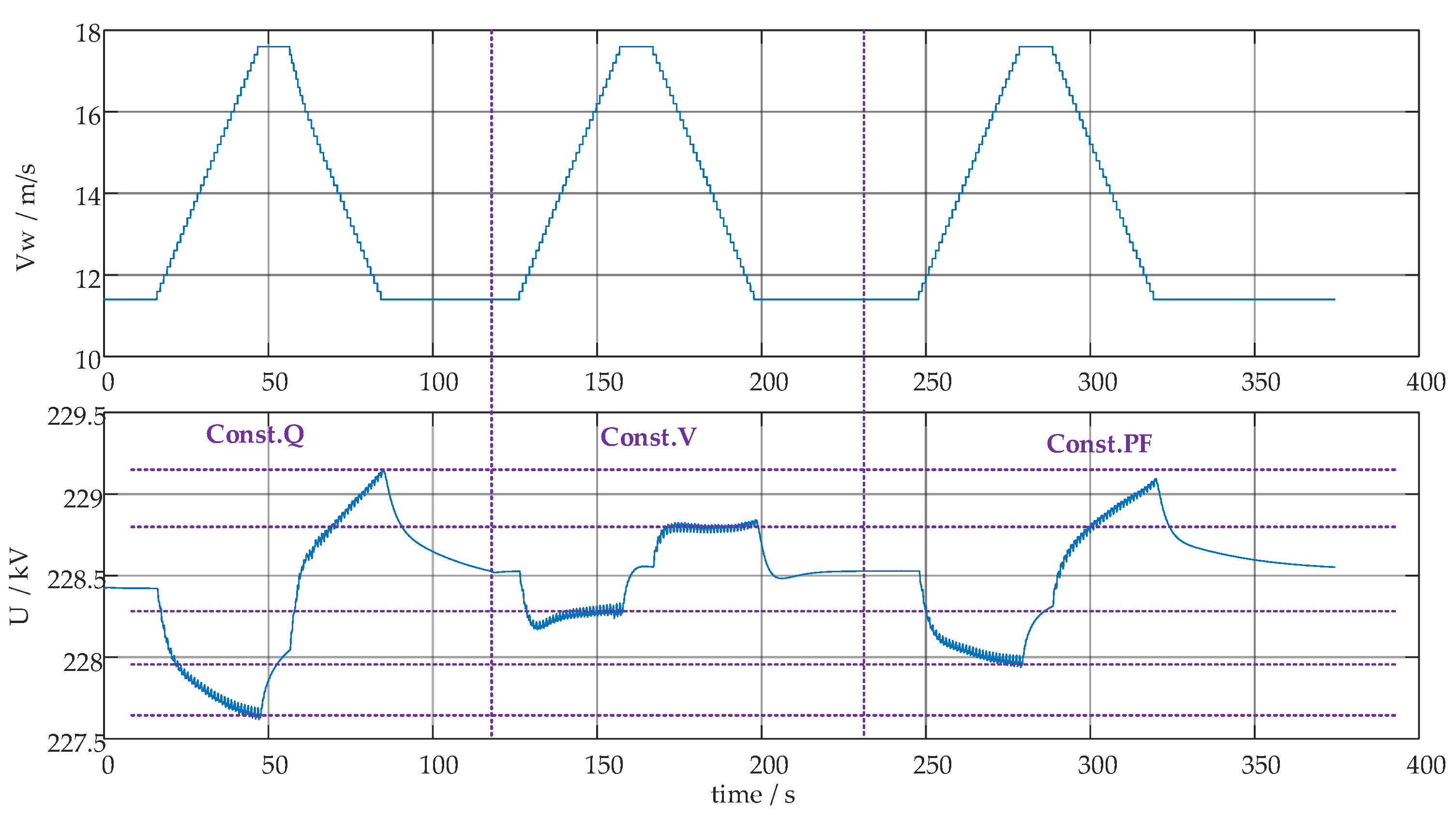

PFset, the required active current and reactive current components to be injected into the grid are calculated. When wind speed changes rapidly, different control modes exhibit varying effects in suppressing voltage fluctuations at the grid connection point of the wind farm. For instance, a time-domain simulation analysis of a single wind farm shows that the constant voltage mode results in the smallest voltage fluctuation amplitude, the constant reactive power mode leads to the largest voltage fluctuation amplitude, and the constant power factor mode falls between the two. The

Figure 5 below compares the suppression effects of voltage fluctuations under different control strategies.

Figure 4.

Generalized Power-Electronic Interface Model.

Figure 4.

Generalized Power-Electronic Interface Model.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the effects of different control strategies under wind speed fluctuations.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the effects of different control strategies under wind speed fluctuations.

5. Case Study

5.1. Configuration of the Studied System

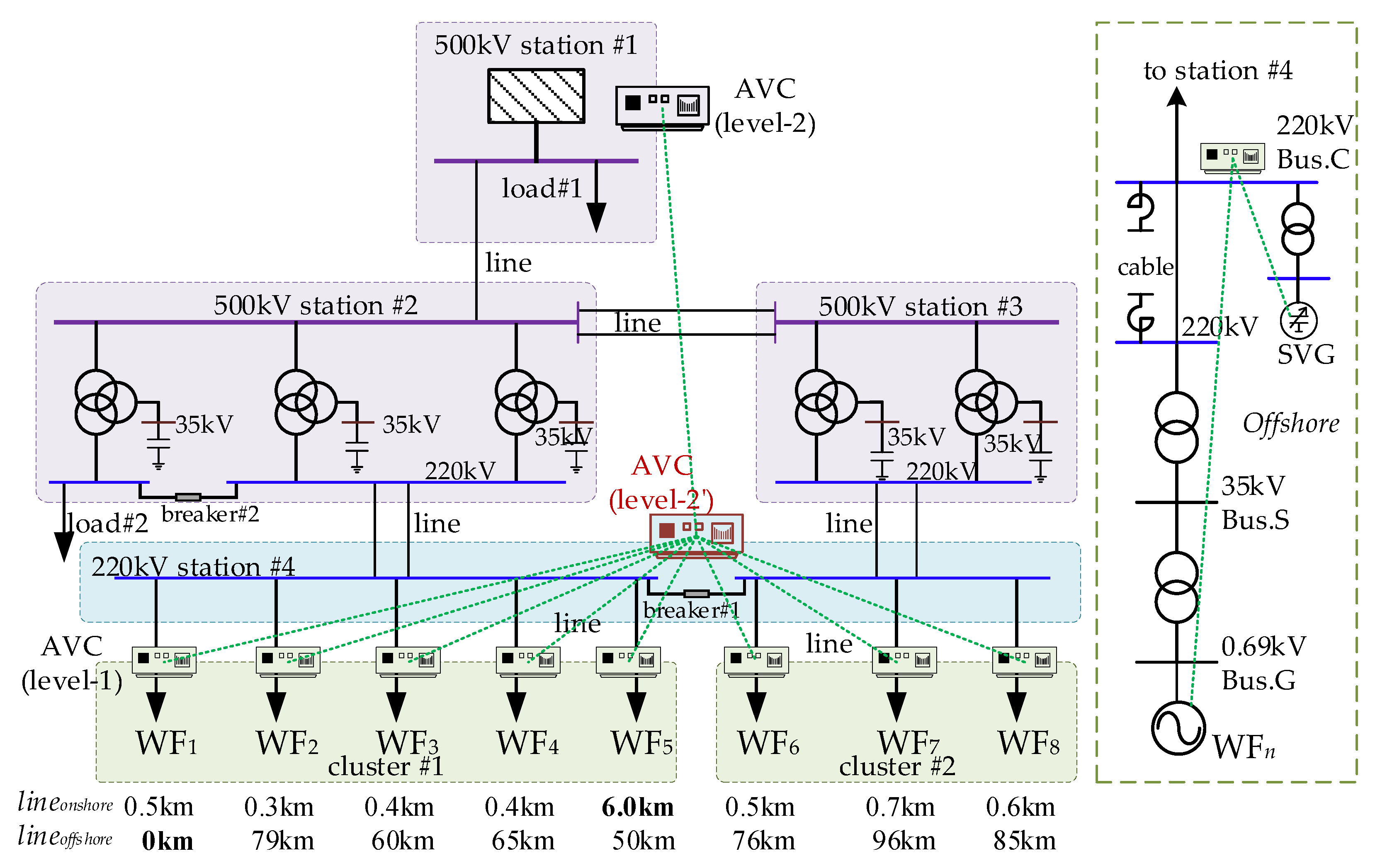

A study case was constructed based on offshore wind power clusters connected via a 500 kV grid along the southeastern coast of China, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Using the developed closed-loop verification platform, tests were performed with multiple physical AVC controllers. The setup enabled detailed analysis of reactive power and voltage oscillation phenomena. Through iterative testing and control-strategy refinement, the proposed approach demonstrated effective mitigation of such oscillations, leading to improved voltage stability in the regional grid.

Figure 6.

Configuration of the Studied System.

Figure 6.

Configuration of the Studied System.

The case includes eight wind farms, with Wind Farm 1 being onshore and the remaining seven being offshore. A cluster voltage coordinated controller is configured at the 220 kV station #4, and each wind farm is equipped with its own AVC plant controller. The

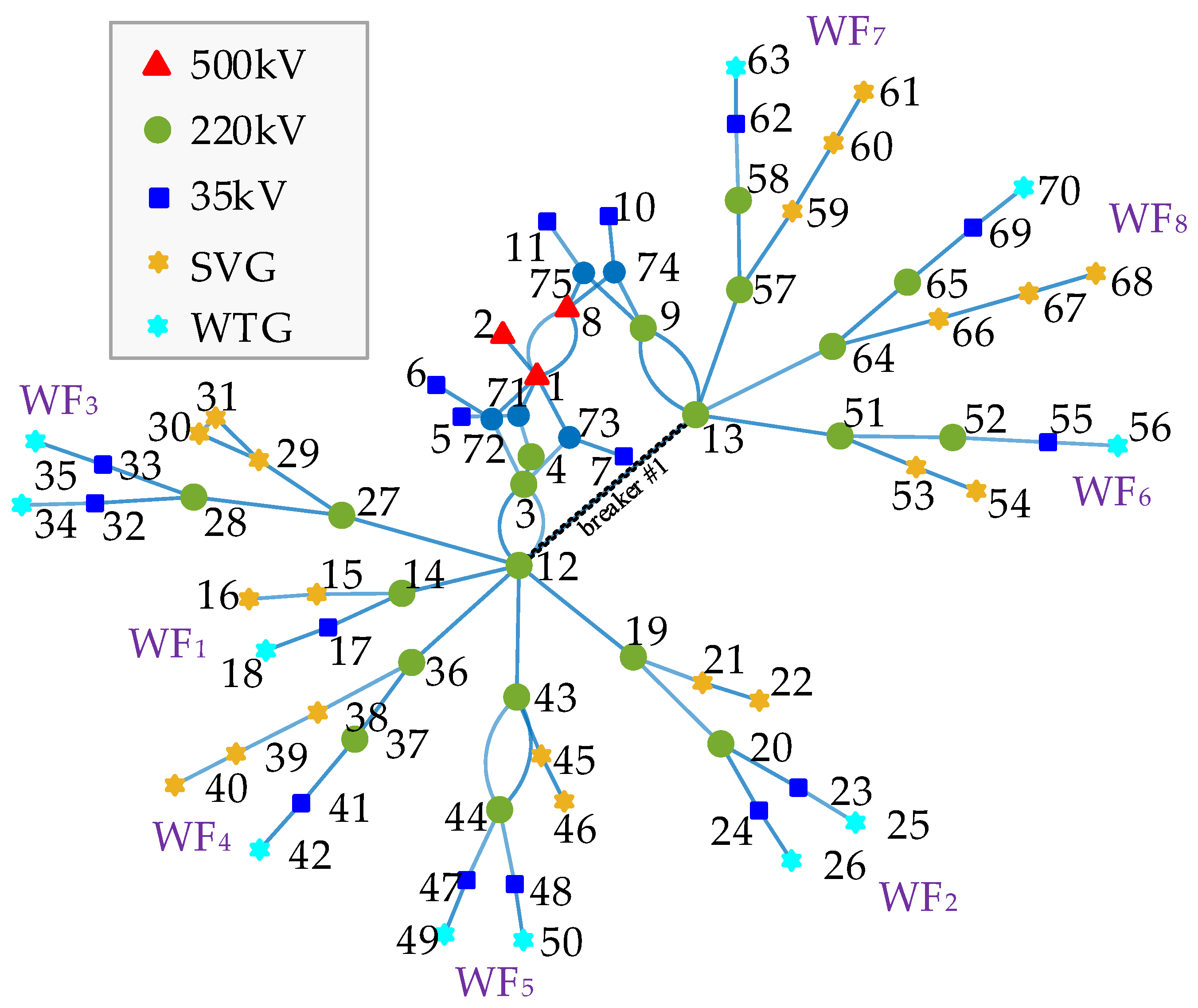

Figure 7 depicts the topological connection relationships between different electrical nodes within the renewable energy clusters. Different colors are used to distinguish the installation locations of the SVG and the wind farms.

Figure 7.

Topological relationships of the renewable energy clusters.

Figure 7.

Topological relationships of the renewable energy clusters.

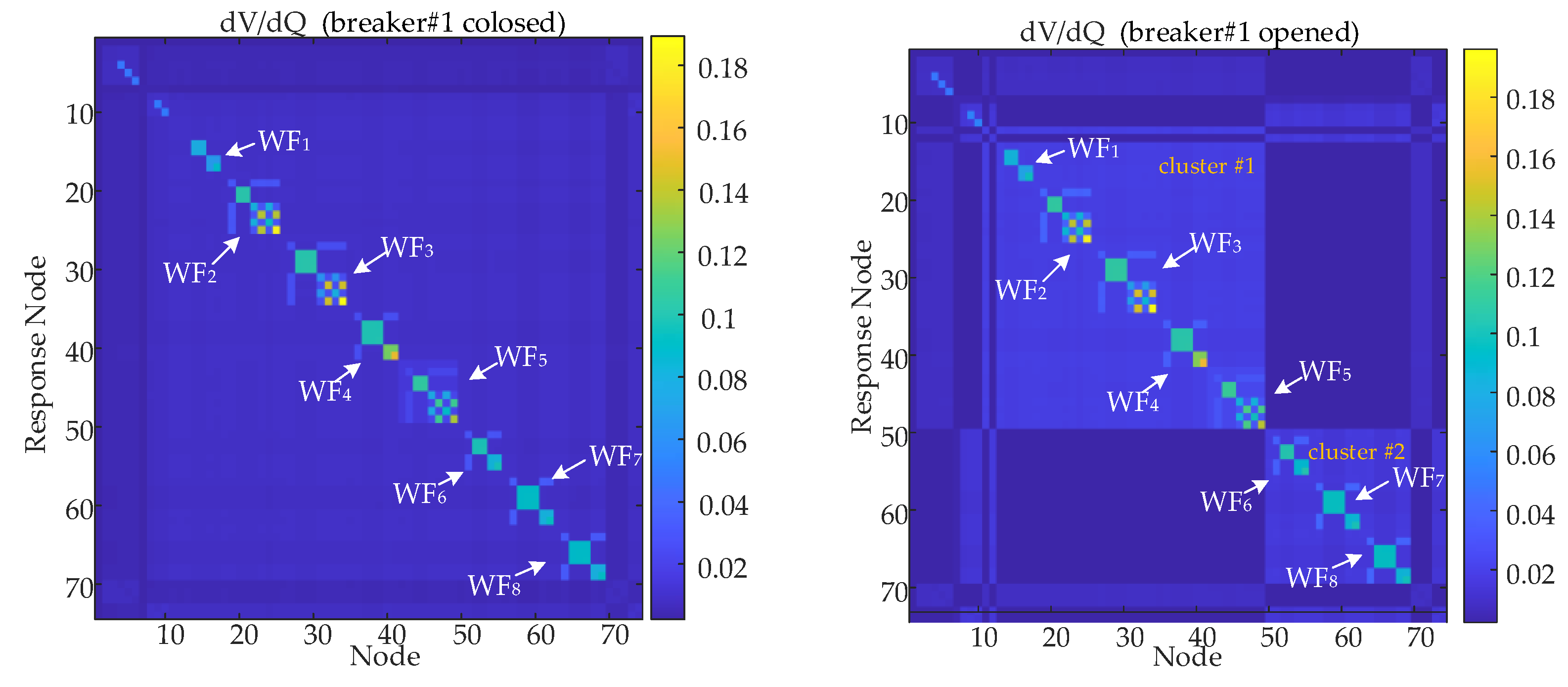

5.2. Voltage Sensitivity Matrix

When the breaker #1 is closed or opened, the renewable energy clusters will present two different grid configurations, and the corresponding voltage sensitivity matrix and short-circuit ratio will both change. Through visual analysis of the voltage sensitivity matrix, it can be observed that there is a certain coupling relationship among multiple renewable energy stations connected to the same 220 kV bus.

Figure 8.

Voltage sensitivity matrix when breaker#1 closed and opened.

Figure 8.

Voltage sensitivity matrix when breaker#1 closed and opened.

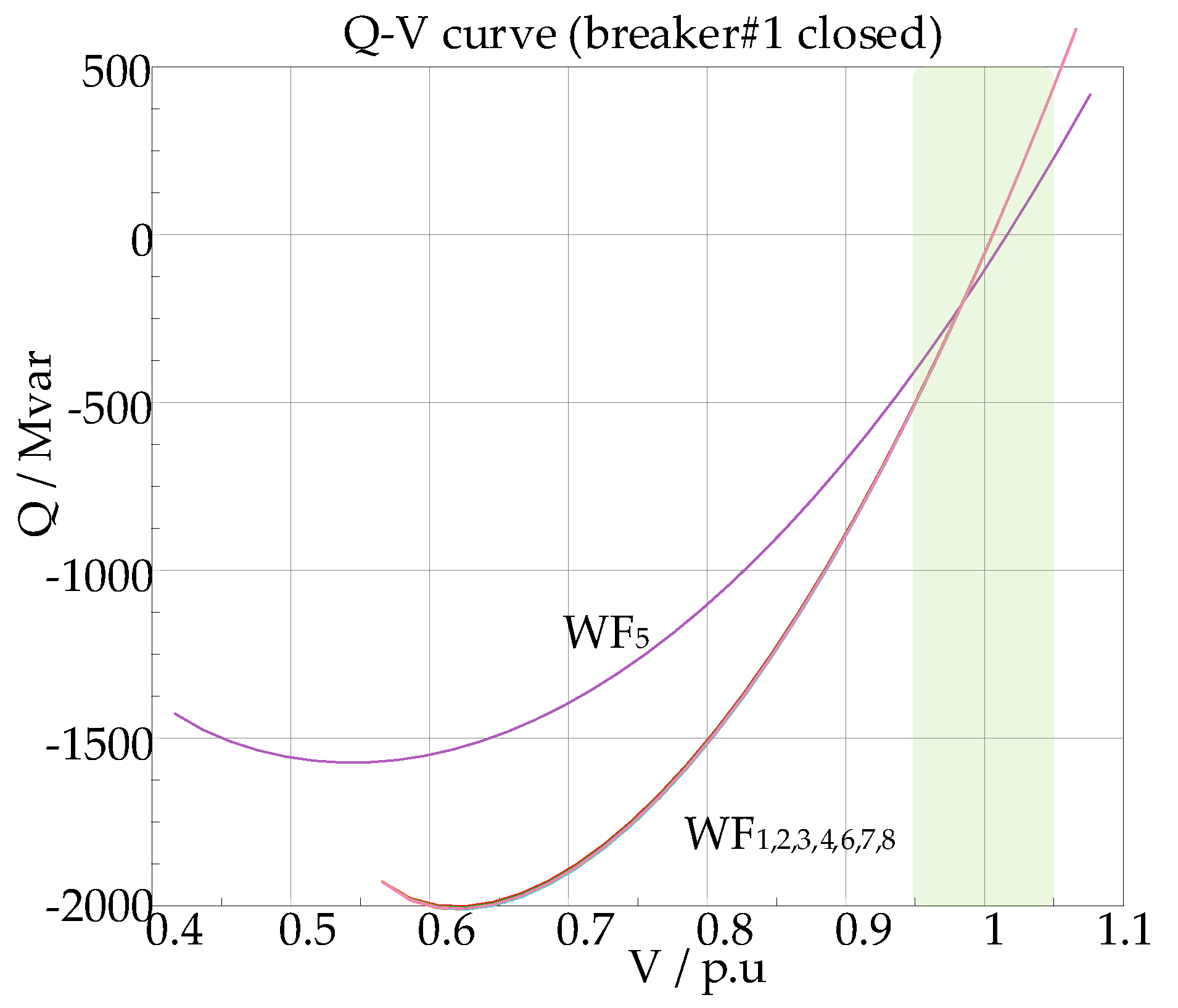

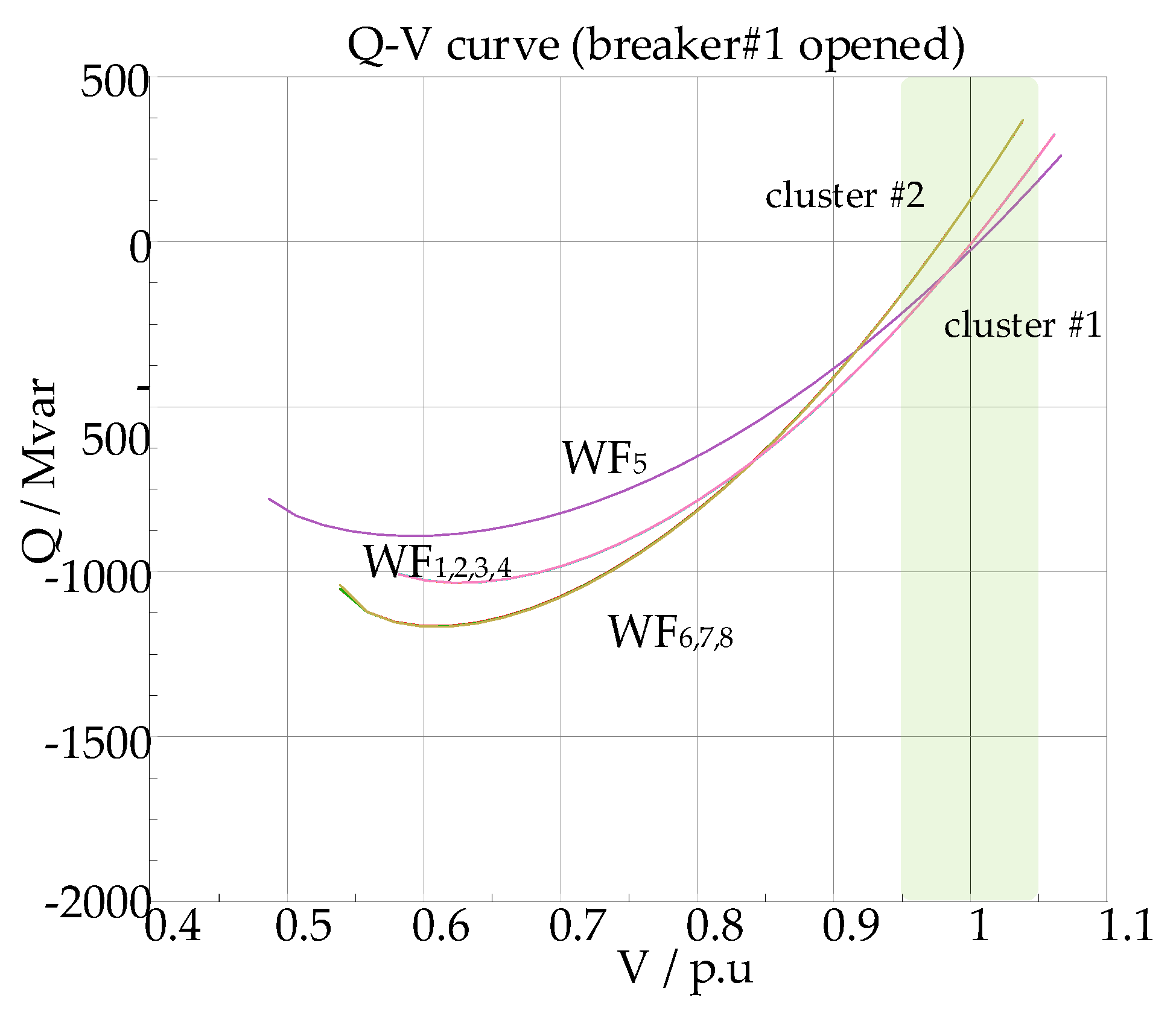

The voltage sensitivity matrix can only reflect small disturbances around a specific operating point. To observe the voltage variation patterns under different reactive power outputs, the Q-V curve can be further calculated. As shown in the

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, near the rated voltage (1.0

p.u.), the slope of the Q-V curve remains largely constant, indicating that the voltage sensitivity is essentially stable. However, the slope of the curve varies significantly under different grid topologies when the status of the breaker #1 changes. Therefore, the enhanced control strategy needs to dynamically calculate the voltage sensitivity matrix based on changes in the grid topology and use it as the basis for reactive power allocation.

5.3. Short-Circuit Ratio

In addition to being influenced by changes in the grid topology, the short-circuit ratio of renewable energy stations is primarily affected by variations in their power output. During periods of high renewable energy output, the short-circuit ratio decreases significantly. Therefore, the improved control strategy should not only maintain voltage around the target value but also optimize reactive power at renewable energy stations with low short-circuit ratios to avoid the presence of weak nodes.

Through extensive offline calculations, an approximately linear relationship between reactive power and MRSCR can be established for each renewable energy station to meet engineering requirements. This forms the basis for constructing a reactive-power-MRSCR sensitivity matrix Cmg, which serves as a primary reference for control optimization in the coordinated controller station.

Table 1.

Short circuit ratio under low renewable energy output condition.

Table 1.

Short circuit ratio under low renewable energy output condition.

| Bus.G |

Pg(MW)

|

Qg(MVar)

|

Ik(kA)

|

ESCR |

MRSCR |

| WF1 |

141.00 |

30.00 |

880.8 |

2.9870 |

3.0407 |

| WF2 |

200.00 |

70.00 |

835.0 |

2.5496 |

2.6351 |

| WF3 |

190.00 |

20.00 |

1008.0 |

2.8667 |

2.8935 |

| WF4 |

140.00 |

20.00 |

545.3 |

2.4087 |

2.4402 |

| WF5 |

174.00 |

20.00 |

886.4 |

2.7835 |

2.8151 |

| WF6 |

220.00 |

40.00 |

832.0 |

2.4505 |

2.4898 |

| WF7 |

220.00 |

40.00 |

860.7 |

2.4954 |

2.5353 |

| WF8 |

220.00 |

40.00 |

870.4 |

2.5103 |

2.5503 |

Table 2.

Short circuit ratio under high renewable energy output condition.

Table 2.

Short circuit ratio under high renewable energy output condition.

| Bus.G |

Pg(MW)

|

Qg(MVar)

|

Ik(kA)

|

ESCR |

MRSCR |

| WF1 |

300 |

30.00 |

786.0 |

1.5188 |

1.5244 |

| WF2 |

300 |

70.00 |

762.5 |

1.5306 |

1.5501 |

| WF3 |

300 |

20.00 |

921.9 |

1.6659 |

1.6645 |

| WF4 |

300 |

20.00 |

440.1 |

1.0655 |

1.0611 |

| WF5 |

300 |

20.00 |

799.1 |

1.5386 |

1.5414 |

| WF6 |

300 |

40.00 |

758.6 |

1.5200 |

1.5278 |

| WF7 |

300 |

40.00 |

786.3 |

1.5489 |

1.5565 |

| WF8 |

300 |

40.00 |

795.2 |

1.5574 |

1.5650 |

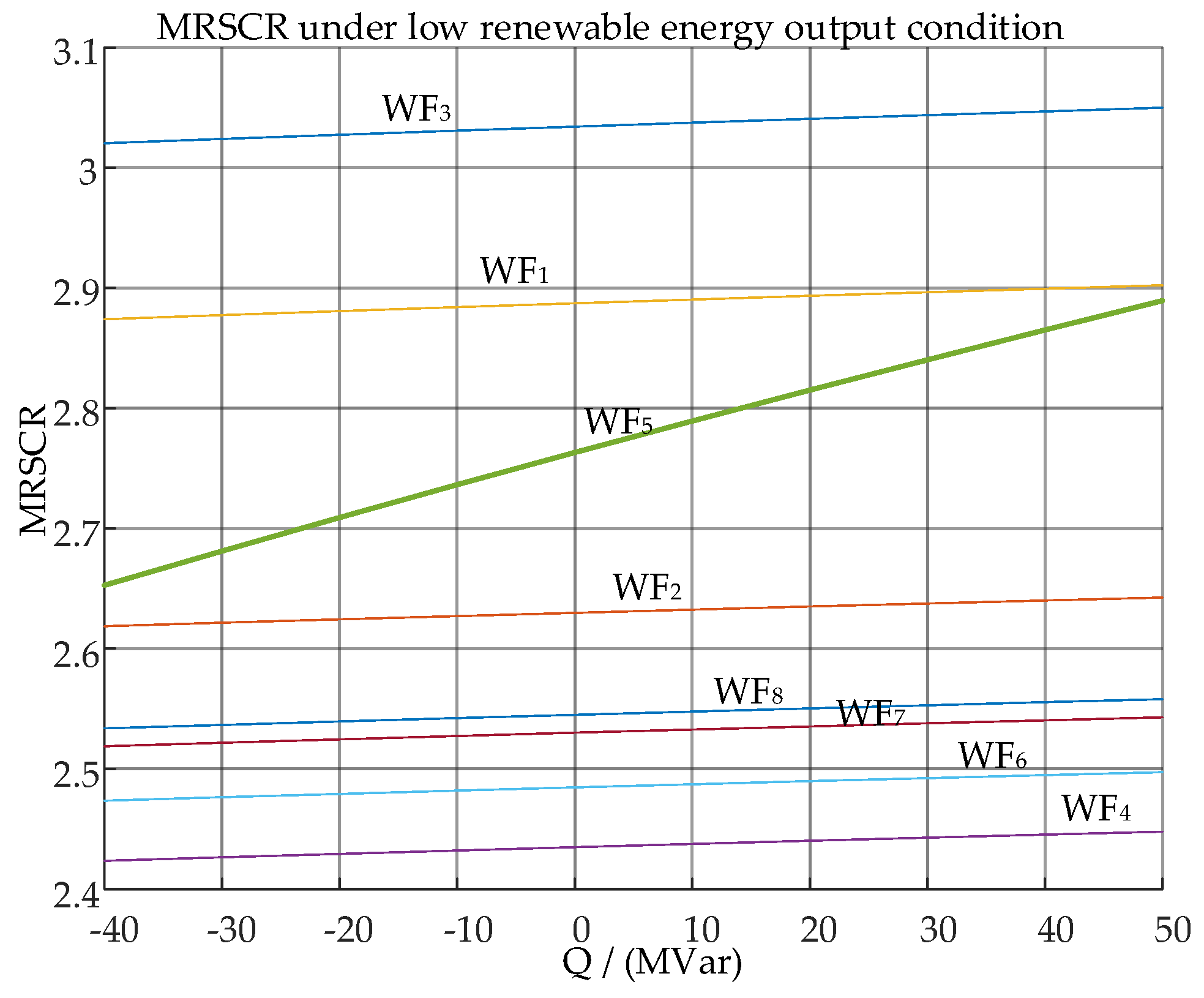

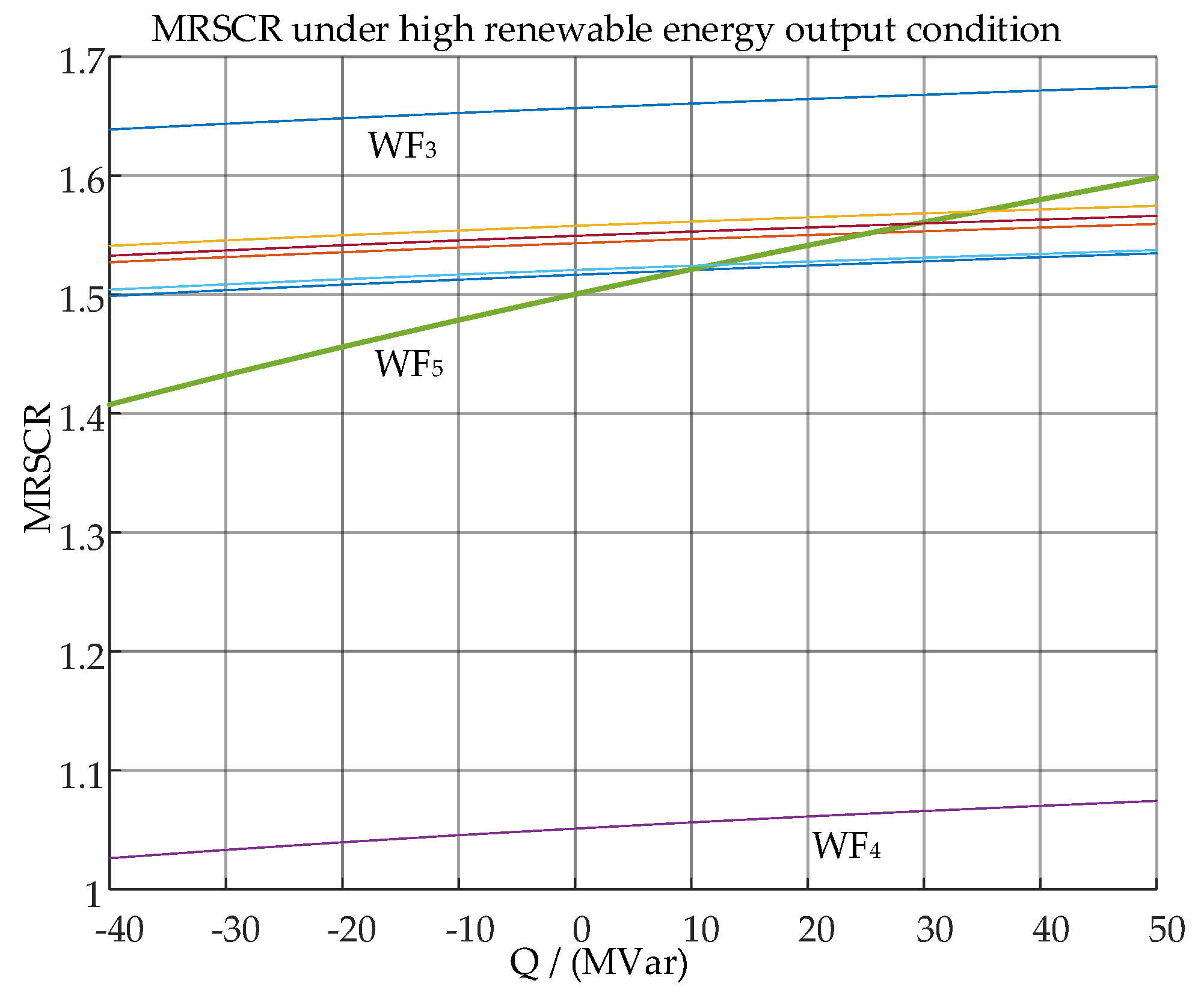

Taking Wind Farm 5 as an example, by varying its reactive power output between 40 MVar and 50 MVar, the trends in the MRSCR changes for all stations can be observed. When the output reactive power is inductive (negative values), a larger inductive reactive power results in a lower short-circuit ratio. Therefore, for wind farms with a low short-circuit ratio, such as those below 1.5, the capacitive reactive power output of these wind farms should be adjusted as much as possible to enhance the overall grid strength of the renewable energy clusters.

Figure 11.

The MRSCR trends when reactive power changes under low power output.

Figure 11.

The MRSCR trends when reactive power changes under low power output.

Figure 12.

The MRSCR trends when reactive power changes under high power output.

Figure 12.

The MRSCR trends when reactive power changes under high power output.

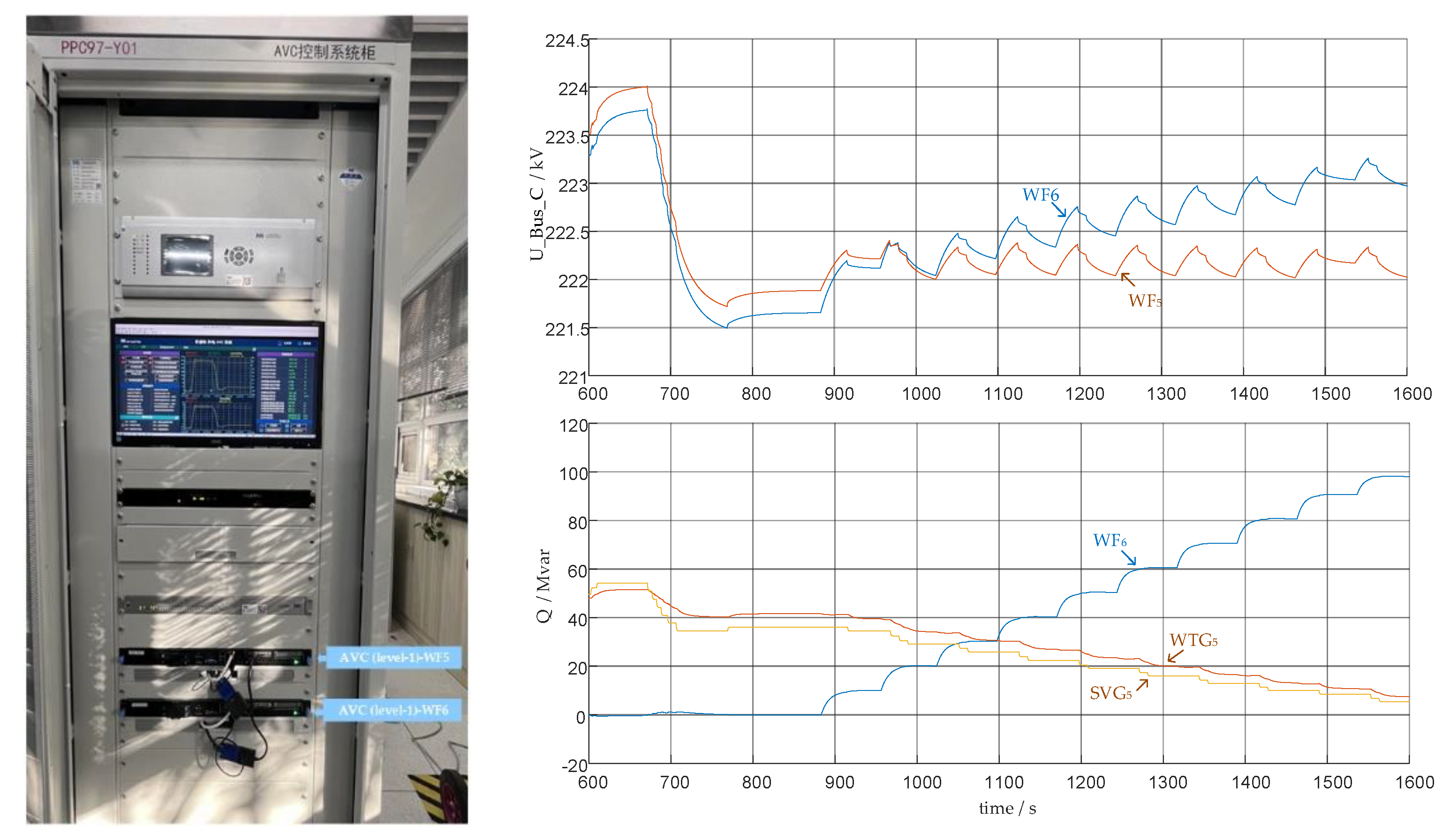

5.4. Hardware-in-the-Loop Experiment

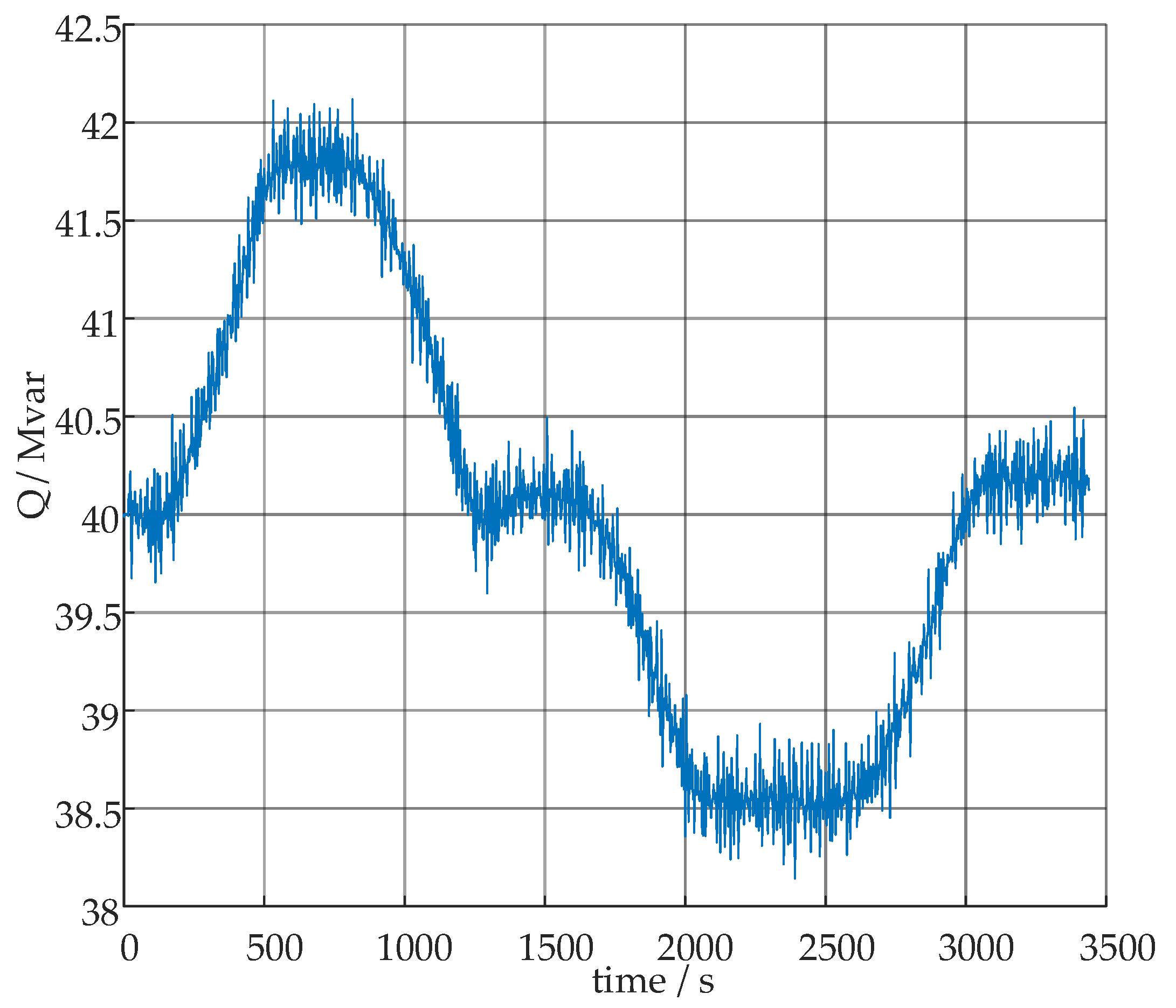

A hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) platform based RMS simulation was set up in a laboratory environment, where actual two AVC controllers (level-1) were used to implement constant voltage control for Wind Farm 5 and Wind Farm 6. When the constant voltage command was set unreasonably, voltage oscillation phenomena were triggered. It can be observed that the reactive power outputs of the two wind farms gradually decreased and increased, respectively, causing the renewable energy cluster to become unstable.

To suppress this potential voltage oscillation phenomenon, a feasible improvement strategy is to introduce a coordinated controller (level-2‘). This coordinated controller calculates the reactive power adjustment for each wind farm based on the current voltage sensitivity and short-circuit ratio levels. The control mode of each wind farm is then switched from constant voltage to constant reactive power control. For stations with lower voltage sensitivity, a constant power factor control mode can be adopted to reduce the number of stations involved in regulation and improve the speed of adjustment.

Figure 13.

Closed-loop hardware-in-the-loop experiment and oscillation waveforms.

Figure 13.

Closed-loop hardware-in-the-loop experiment and oscillation waveforms.

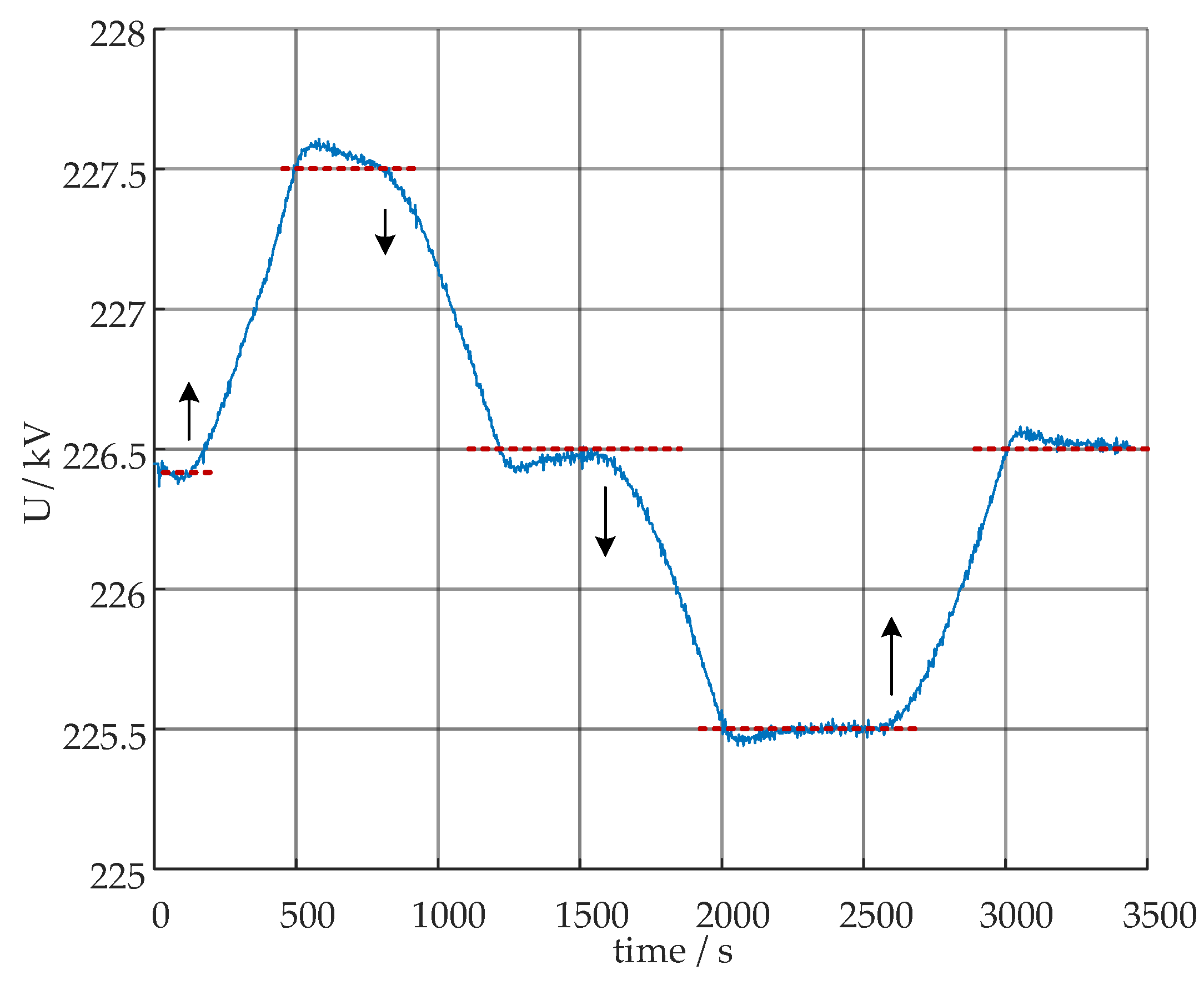

Simulating a primary AVC control center (level-2), constant voltage commands were sent to the coordinated controller (level-2‘), increasing the voltage from 226.4 kV to 227.5 kV, then lowering it to 226.5 kV, further reducing it to 225.5 kV, and finally raising it back to 226.5 kV. During this process, random wind speed disturbances were introduced to each wind farm. Observations of the control effectiveness show that the voltage regulation at the central bus (station #4) was relatively satisfactory, but the overall control time was prolonged. Future improvements should focus on enhancing the communication protocol between the coordinated control station and the subordinate stations (level-1), with a recommendation to upgrade from IEC 60870-104 to a faster protocol such as GOOSE in order to improve overall control performance.

Figure 14.

Voltage of station #4 for collaborative control strategy experiments.

Figure 14.

Voltage of station #4 for collaborative control strategy experiments.

Figure 15.

Reactive power of WF5 for collaborative control strategy experiments.

Figure 15.

Reactive power of WF5 for collaborative control strategy experiments.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a hierarchical, multi-mode coordinated control strategy for reactive power and an efficient verification scheme to suppress oscillations in power systems with clustered renewable energy sources. The effectiveness of this strategy is validated through case studies based on an actual power system, with results indicating a significant reduction in voltage fluctuations relative to conventional automatic voltage control (AVC) methods. The strategy systematically incorporates two key indices: a voltage sensitivity index, which characterizes small-signal stability, and a short-circuit ratio (SCR) index, which reflects robustness against large disturbances. This integrated framework facilitates the rational and dynamic adjustment of various control modes constant voltage, constant reactive power, and constant power factor. Accordingly, the algorithm delivers enhanced performance without necessitating wind power curtailment and concurrently improves the grid’s short-circuit ratio. This dual outcome ensures both the maximal utilization of renewable generation and the preservation of overall system reliability.

Future work should focus on extending the proposed strategy to complex regional grids that incorporate multiple types of reactive power sources, including grid-forming energy storage systems, to achieve coordinated steady-state and transient voltage support. It is recommended that further refinements be made to the SCR calculation methodology, that adaptive sensitivity estimation techniques utilizing neighboring node information be developed, and that predictive models for anticipatory control be integrated to improve real-time performance. The application of this algorithm to larger-scale systems, such as major renewable energy bases, coupled with enhanced information-exchange mechanisms between provincial dispatch centers and improved substation communication capabilities through the mitigation of coordination delays, would contribute to the further advancement of regional voltage quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L and L.Z; validation, Y.L., M.Q. and C.J.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L. , M.Q. and C.J.; project administration, Y.L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Program of the SGCC “Research on interactive voltage stability mechanisms and coordinated control verification techniques for renewable energy clusters connected to the power grid” (5100-202355753A-3-4-SY).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to (specify the reason for the restriction).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the reviewers and editors for providing valuable advice.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yanzhang Liu, Lingzhi Zhu and Minhui Qian were employed by the China Electric Power Research Institute. Author Chen Jia was employed by the State Grid Liaoning Electric Power Research Institute. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCR |

Short circuit ratio |

| CSCR |

Critical short circuit ratio |

| WSCR |

Weighted short-circuit ratio |

| ESCR |

Equivalent short-circuit ratio |

| MRSCR |

Multi-renewable energy station short circuit ratio |

| AVC |

Automatic voltage control |

| OPF |

Optimal power flow |

| Kpv |

Proportional coefficient of the PI module in voltage control |

| Kiv |

Integral coefficient of the PI module in voltage control |

| Tr |

The time constant reflects the communication delay |

| Tv |

The time constant reflects the measurement lag |

| Zc |

Compensation impedance |

|

Qmax, Qmin

|

Maximum and minimum reactive power limit |

| KQi |

Proportional coefficient of the PI module in reactive power control |

| KVi |

Integral coefficient of the PI module in reactive power control |

|

Vterm

|

Terminal voltage of renewable energy station |

|

V*max, V*min

|

Maximum and minimum voltage limit |

| Tp |

The time constant reflects the converter action |

| vflg |

Enable closed-loop regulation of Vterm when the flag vflg is set to 1 |

| cflg |

Control mode switch, 0-const.Q, 1-const.V; 2-const.PF |

| Vset |

Voltage setpoint |

| PFset |

Power factor setpoint |

| Qset |

Reactive power setpoint |

| Pset |

Active power setpoint |

| Vreg |

The voltage of regulate remote bus |

| Pg |

Active output of renewable energy stations |

| Qg |

Reactive output of renewable energy stations |

References

- Sun, H.; Guo, Q; Qi, J.; et al. Review of challenges and research opportunities for voltage control in smart grids. IEEE Trans. on Power Syst. 2019, vol. 34(no. 4), 2790–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker; Ahmad, S. S.; Ahmed, I.; Khalid, M.; Abido, M. A.; Al-Ismail, F. Saleh. Optimal power flow: a review of state-of-the-art techniques and future perspectives. IEEE Access 2025, vol. 13, 60012–60039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrou, G.; Lai, H.; Hug, G.; Wang, X. A. Decentralized wide-area voltage control scheme for coordinated secondary voltage regulation using PMUs. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, vol. 39(no. 6), 7153–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, A. E. M.; Marinescu, B.; Denis, G. Structural analysis and improved reactive power alignment for secondary voltage control. In PowerTech, Italy; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubeša, R.; Rekić, M.; Bunčec, Z.; Stupić, T.; Peharda, D.; Raič, M. N. Automated Tertiary voltage control in transmission system. In ISGT, France; 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Zhou, B.; Huang, S. Distributed coordinated voltage control for distribution networks with DG and OLTC based on MPC and gradient projection. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, vol. 37(no. 1), 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Z; Zhang, R. Multi-objective hierarchically-coordinated Volt/Var control for active distribution networks with droop-controlled PV inverters. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, vol. 13(no. 2), 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chiang, H. D.; Li, T. Three-timescale hierarchical multi-objective Volt/Var control in active distribution network with inverters droop control. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 197602–197615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liang, J.; Du, X.; Wu, M. Multi-timescale reactive power optimization and regulation method for distribution networks under a multi-source interaction environment. Processes 2024, 12, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondharangalla, M.; Moldovan, D.; Ayyanar, R. Volt-PF control mode for distribution feeder voltage management under high penetration of distributed energy resources. IEEE Access 2025, vol. 13, 14949–14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, R.; Yang, L. Optimization of local voltage control with coordinating droop functions under high PV penetration. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 6776–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ren, Q.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. A hierarchical distributed and local voltage control strategy for photovoltaic clusters in distribution networks. Processes 2025, 13, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Ji, H.; Yu, H.; Zhao, J.; Xi, W.; Wu, J. Adaptive voltage control of inverter-based DG in active distribution networks with measurement-strategy mapping matrix. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbouj, H.; Rather, Z. H.; Pal, B. C. Adaptive voltage control for large scale solar PV power plant considering real life factors. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, vol. 12(no. 2), 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong; Ravishankar, Z; J. Three-stage robust inverter-based voltage/var control for distribution networks with high-level PV. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, vol. 10(no. 1), 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, F.U.; Pal, B.C.; Jabr, R.A. Affinely adjustable robust volt/var control without centralized computations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Niu, T.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lei, Y. Optimal placement and sizing of reactive power compensation devices in power grids with high penetration of distributed generation. Processes 2025, 13, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.-L.; Ying, F.; Li, F. Collection system topology for deep-sea offshore wind farms considering wind characteristics. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.W.; Raza, M.; Badia, J.G.; Prieto-Araujo, E.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Fault handling capabilities of grid-forming wind turbines in offshore wind farms connected with MMC HVDC system. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 36404–36414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, F. Double-layer reactive power optimal configuration method for large-scale offshore wind farms based on an adaptively improved gravitational search algorithm. Processes 2025, 13, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegahapola, L.; Durairaj, S.; Flynn, D.; Fox, B. Coordinated utilisation of wind farm reactive power capability for system loss optimisation. Eur. Trans. Electr. Power 2011, 21, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalman, Y.; Çelik, Özgür; Adnan, T; et al. Impacts of large-scale offshore wind power plants integration on Turkish power system. IEEE Access 2022, vol. 10, 83265–83280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tipán, F.; Barrera-Singaña, C.; Valenzuela, A. Reactive power compensation using power flow sensitivity analysis and QV curves. In ANDESCON. Ecuador; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalib-Bin-Karim, C.; Liang, X.; Khan, N.; Zhang, H. Determine Q–V characteristics of grid-connected wind farms for voltage control using a data-driven analytics approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, vol. 53(no. 5), 4162–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, W. Research on dynamic reactive power cost optimization in power systems with DFIG wind farms. Processes 2024, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Z. L.; Lin, H. Y.; Teng, J. H. Decentralized q control for photovoltaic generation systems in distribution systems using IEC61850 GOOSE. In IAS, Taiwan; 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bose, A.; Venkatasubramanian, V. M. Wide-area voltage monitoring and optimization. IEEE Trans. on Smart Grid 2016, vol. 7(no. 2), 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, H.; Wu, D.; Gao, H.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, Y. Generalized operational short-circuit ratio for grid strength assessment in power systems with high renewable penetration. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, vol. 39(no. 4), 5479–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Hyoung; Choi, D.; Baek, S. M. Complex short circuit ratio to evaluate grid robustness for inverter integration. IEEE Access 2025, vol. 13, 132693–132702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadun, N.; Abdullah, S. K. S.; Nizam, M. K.; Azmi, M. T.; Omar, Z. B.; Turiman, M. S. Real-time power system simulation hardware-in-the-loop testbed for coordinated voltage control system. PowerCon 2022, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).