Introduction

The insect epicuticle is endowed with a plethora of hydrocarbons (cuticular hydrocarbons - CHCs) comprising saturated and unsaturated linear alkanes, and multiple monomethyl and dimethyl branched alkanes. Their primary function is to provide an impermeable layer that protects the insect from desiccation (reviewed in Gibbs and Rajpurohit 2010). To that effect the epicuticle comprises of multiple linear alkanes, generally ranging from eicosane (C20H42 - MW 282) to tritriacontane (C33H68 - MW 464), that cover the entire ant’s cuticular surface. The use of a mixture of alkanes, rather than a single high molecular alkane, is adaptive because the mixture expresses a eutectic behavior, that is, the mixture behaves as a single compound with a melting point that is below any of its pure components, which creates a uniform solid-liquid layer that overlays the entire body surface. Impermeability increases with the increase in carbon chain length, so the mixture composition seems to be a tradeoff between the gain in impermeability and the cost of biosynthesis. In social insects, ants in particular, the CHC is typified by the occurrence of multiple branched alkanes, mostly monomethyl but also dimethyl compounds. This is perplexing because the presence of branched alkanes lowers the melting temperature of the linear alkane mixture and consequently lessens the epicuticle efficacy as an impermeable layer (Gibbs 2002; Johnson and Gibbs 2004). This suggests that in ants the branched CHCs have another essential function. Behavioral studies have indeed shown that the branched CHCs are effective mediators of social communication, mostly regarding nestmate recognition but also in delineating caste identity, e.g., queen recognition (Dani et al. 2001; Dietemann et al. 2003; Hefetz 2007; Le Conte and Hefetz 2008; Van Oystaeyen et al. 2014; Liebig and Amsalem 2025). The use of branched alkanes for communication is adaptive because they potentially contain an abundance of chain-position isomers (within-molecule-variation of the branching sites) as well as potential stereoisomers, which greatly increases their information content as chemical signals (Masuda and Mori 2002; Hefetz 2007; Hefetz et al. 2010; Bello et al. 2015; Hefetz 2025). Ant branched CHCs are generally non-volatile so their mode of perception is through contact that, in turn, necessitate their externalization onto the body surface. They therefore constitute a blend with the linear alkanes, conferring a dual function for the CHCs in total. Intuitively, the evolution of branched alkanes as cuticular components may have been derived from the biosynthesis of the respective linear alkanes by adding the branching. But in fact, studies of the biosynthesis of branched alkanes have shown that they are biosynthesized via a specific pathway, disparate from the pathway of linear alkanes (Blomquist 2010). This raises the question of whether the primary driving force for the evolution of branched alkanes was in response to communication needs or originally fulfilled a different function and were secondarily adopted as communicative signals. From the parsimony perspective of evolution, the secondary adoption of branched alkanes for communication seems most probable. If so, what was their postulated non-communicative function? Examination of the biosynthesis of branched alkanes point to branched fatty acids, their immediate biosynthetic precursors, as the evolutionary primers. Branched fatty acids are effective bactericides that disrupts their cell membrane and are in particular effective against mycoplasma that lack cell wall (Casillas-Vargas et al. 2021). Mycoplasmas are abundant in arthropods and includs entomopathogenic species (Clark 1982), which suggests that this was the original driving force for the evolution of branched fatty acids. Thereafter, being spread throughout the body surface they were coopted as communicative signals. If so, ants must still produce branch fatty acids as bactericides. The present study shows by chemical analysis of head extract of the ant Cataglyphis niger the presence of multiple branched fatty acids with branched position corresponding the ants’ cuticular branched alkanes. Furthermore, it appears that they are stored in the head as heptyl esters, presumably for protective the glandular cells from the ill effects of free branched fatty acids.

Materials & Methods

Ant Collection

Colonies of Cataglyphis niger were collected in Tel-Aviv, Israel and included the brood, queens, and workers. In the laboratory, the ants were transferred to artificial nests placed in a rearing room under a controlled temperature of 28 ± 2 °C and a photoperiod of 14L:10D. The ants were provided with a diet of sugar water and minced insects three times a week.

Chemical Analysis

All extracts and dissections were performed using freshly frozen workers. For total head extracts, heads were cleanly excised and homogenized in 1 ml of hexane. The extracts were filtered through a sinter glass funnel to remove all cuticular debris and concentrated to approximate 200 µl. Postpharyngeal glands were cleanly dissected out of the head by removing the labium and pinching out the gland with fine forceps. For extraction each gland was placed in 200 µl hexane. All extracts were stored at -200C until analysis.

Chemical analyses were performed by combined gas chromatography mass spectrometry, Agilent 19091S-433UI at EI and splitless modes, using a HP-5ms column that was temperature programmed from initial temperature of 600C with 1 minute hold followed by temperature rise at a rate of 100C/min to 3000C, and a final hold of 15 minutes. Compounds were identified by their mass fragmentation pattern. Retention times were ascertained by injecting a series of alkanes from decane (C10H12) to tritriacontane (C33H68) under the same conditions.

Results

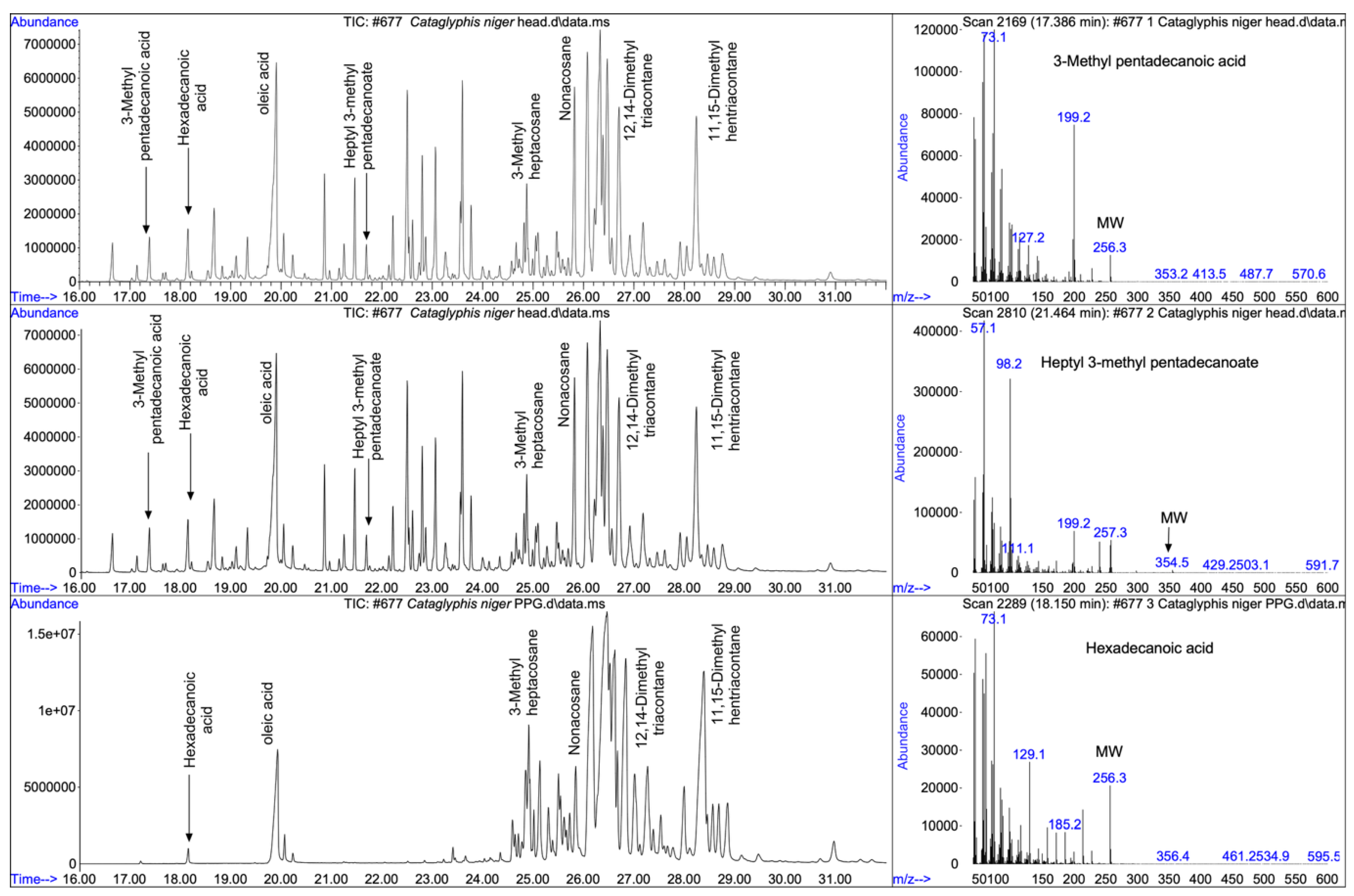

Figure 1 shows a comparative analysis of head extracts and cleanly dissected postpharyngeal gland, along with three spectra characterizing the three types of compounds identified.

Table 1 shows the acids and the corresponding heptyl esters components of the total head extract, and

Table 2 shows the alkane components of the postpharyngeal gland secretion. Head extracts possess three classes of compounds: linear and branched fatty acids (C

14-C

18), their corresponding heptyl esters, and aliphatic hydrocarbons. The identity of the branched fatty acids was inferred from their mass spectrum. For comparison, the mass spectrum of the linear hexadecanoic acid (molecular weight 256;

Figure 1C right) is typified by a large molecular ion (M/Z 256) and large fragments at m/z 60 and m/z 73 (corresponding to acetate and a higher rearrangement at the carboxylic end of the molecule). On the other hand, the spectrum of 3-methyl pentadecanoic acid (molecular weight 256;

Figure 1 A right) is characterized by much smaller molecular ion (m/z 256) and a large ion at m/z 199 indicating the loss of 57 (C

4H

9). This compound has also an appreciably lower ion at M/Z 60, compared to hexadecanoic acid. The monomethyl fatty acids were occasionally accompanied by dimethyl fatty acids, deduce from their molecular ion and the lower retention time (RT) compared to the same molecular weight fatty acids. For example, for molecular weight of 270 the RT for dimethyl pentadecanoic acid was 18.2 min, for 3 methyl hexadecanoic acid an RT of 18.8 min and for heptadecanoic acid an RT of 18.8. The small quantities of the dimethyl acids, however, did not allow full determination of the branching positions. The omnipresent loss of 57 from the molecular ion (m-57) indicates a branching at 3-position, but determination of the second branching position was not possible.

The second type of compounds found in head extracts are heptyl esters, as judge by the large ion peak at M/Z 98, corresponding to heptane fragment of the alcoholic moiety of the ester. As in the case of the branched carboxylic acids the identity of the acidic moiety was characterized its corresponding molecular ion and (m-57) the for the 3-methyl acids. The molecular weight of each of the esters was disclosed by a small but visible molecular ion. For example, the ester heptyl 3-methyl pentadecanoate (Figure1 B right) is characterized by the molecular ion at M/Z=354, M/Z=98 corresponding to of heptane representing the alcoholic moiety of the ester, M/Z=257 indicating the acid moiety of the ester, and M/Z 239 and M/Z 199 corresponding respectively to the loss of water and butane from the acid moiety.

The third type of compounds comprised linear and branched alkane ranging from pentacosane to tritriacontane, which were common both in the head extracts and the postpharyngeal gland, indicating that the latter is their source. Notable is the dominance of the high molecular weight hydrocarbons ranging from mono- and dimethyl nonacosane (MW 422-436) to mono- and dimethyl tritriacontane (MW 478-492), in line with the desertic habitat these ants occupy. The postpharyngeal gland exudates also contained hexadecanoic, oleic, and octadecanoic acids, but none of the branched acids or their esters, indicating that the origin of both the branched acids and their corresponding esters is from another, yet unknown head gland.

Conclusions

The evolution of communicative signals is complicated by the requirement that its two components, the signal and its perception, have to coevolve to be effective. The general assumption is of two steps evolution. For chemical communication, for examples, it is assumed that preexisting substances that fulfill a structural (non-communicative) function were secondarily coopted as communication signals. The evolution of cuticular hydrocarbons serve as an example of such an evolutionary scenario. They constitute mostly two classes, linear alkanes and branched, monomethyl and to a lesser extent dimethyl, alkanes. Multiple studies have shown that cuticular hydrocarbons, in particular the linear alkane components are important in imparting an external impermeable layer that protects the ants from desiccation (Gibbs and Rajpurohit 2010 and references therein). Covering the external surface of the body made them ideal for cooption as communicative signals. Moreover, theoretically only a few long-chain alkanes are sufficient for imparting an effective impermeable layer. Yet, as exemplified in this study cuticular hydrocarbons comprises complex mixtures of alkanes and branched alkanes. This suggests that they bear another function, namely communicative function. A presumed subsequent evolution of specific hydrocarbon perception systems (Ozaki et al. 2005; Ozaki and Hefetz 2014; Pask et al. 2017; Watanabe et al. 2023) paved the way for their cooption a signals for nestmate recognition as well as denoting caste identity (Lahav et al. 1999; Hefetz 2007; van Zweden and d’Ettorre 2010; Van Oystaeyen et al. 2014).

While the role of hydrocarbons in providing an impermeable layer does not necessarily be idiosyncratic, their cooption for communication needs to be species and even caste specific, which led to diversification in their composition along the phylogeny of ants (van Wilgenburg et al. 2011). The evident targets for such diversification are the branched alkanes because for a given chain length, each of the linear alkanes can possess multiple positional isomers (the molecular site of the branching), enhancing the informational content of the semiochemical. A caveat in utilizing an abundance of branch alkanes is that this diminishes the impermeability efficacy of the cuticle. Therefore, there seems to be a flexible steady state with regard to the proportion of each of these classes of hydrocarbons.

Given the different functions of linear vis a vis branched alkanes a question of their evolution raises, i.e., did branched alkanes derive from linear alkane or did they evolve independently? The fact that linear and branched alkanes are biosynthesized via separate pathways lend credence to their independent evolution, rather than as derivatives of linear alkanes. What was then the driving force for their evolution? Did they evolve specifically as signals or have they evolved in response to another, non-communicative, function and were secondarily coopted as signals. Inspection of the biosynthesis of branched alkanes point to branched fatty acids as roots of their evolution. Branched fatty acids, in particular the 3-methyl fatty acids, are effective bactericides and may have evolved to protect the ants from microbial pathogens such as mycoplasma. It was but a small biosynthetic leap to generate the corresponding branched alkanes (Blomquist 2010; Qiu et al. 2012). Coupled with the evolution of hydrocarbon perception system enabled the complete cooption of branched alkanes as semiochemicals. Corroborating this hypothesis are the above-described discovery of multiple branched fatty acids head extracts in larger amounts than expected from being biosynthetic intermediates. Their absence from the postpharyngeal gland content, the major storage of cuticular hydrocarbons (both linear and branched) indicates that they are stored elsewhere in the head. They possibly have retained their function as bactericides applied to the body surface by extensive self-grooming typical of these ants (Boulay et al. 2017). The head extracts also contained large amounts of their corresponding heptyl esters, probably serving as benign storage of the rather toxic branched fatty acids.

As mentioned above, the transformation to communicative functions was followed by diversification, which was obtained by producing multiple positional isomers. This however created another problem. In contrast to the 3 methyl alkanes that do not reduce much the cuticular impermeability, middle branched alkanes considerably decrease it (Gibbs and Pomonis 1995). Why ants possess an abundance of middle-branched hydrocarbons? What might be their advantage that counterbalances their disadvantage? One explanation may be that these compounds could constitute costly signals, sensu the handicap principle, (Zahavi 1975; Zahavi and Zahavi 1999), encoding yet undescribed communicative function, e.g., queen - worker signaling. Thus, the function of the branched alkanes is dual: the 3- and 5-methyl branched constitute the protective zone whereas the middle branched 11- and 13-methyl constitute the handicap zone (illustrated in Figure 4.4. in Hefetz 2025).

Reinforcing the hypothesis of the independent evolution of linear and branched alkanes is a recent study of the regulation of their biosynthesis in the Carpenter ant Camponotus fellah. It is regulated by the neurohormone inotocin produced by the suboesophageal ganglion that is perceived in the fat body by a specific inotocin receptor. Expressions of both the neurohormone and its receptors are upregulated when workers shift from nursing to foraging, resulting in a concomitant increase in the proportion of linear alkanes. Blocking the inotocin receptor with the inhibitor Atociban resulted in significant reduction in the amounts of linear alkanes but not that of branched alkanes (Koto et al. 2019). This suggests a different effect of inotocin on the biosynthesis of linear vs branched alkanes, reaffirming their independent evolution. Notwithstanding, using another inotocin antagonist (designated as compound B inKoto et al. 2019) resulted in a decrease in both linear and branched alkanes, possibly affecting their biosynthesis in a different way.

In conclusion, the data presented here and published elsewhere support the hypothesis that linear and branched alkanes evolved independently. Linear alkanes evolved primarily to impart impermeability, and in ants their levels are regulated in accordance with the shift from in-door to out-door tasks. Being higher in foragers they may also act as a cue that indicates the foraging performance of the colony and consequently affect overall colony behavior (Greene and Gordon 2003). Branched hydrocarbons, on the other hand, may have evolved by modifying of the preexisting biosynthetic pathway of the antibiotic branched fatty acid, and coopting them for communication, e.g., nestmate recognition and caste idiosyncrasy. Assuming a communicative role, the necessity for more specificity ensued and was a driving force for their molecular diversification, including the shift in branching towards the middle of the molecule. The amount of branching and the abundance of middle chain branching may be regulated as a tradeoff between lowing impermeability and reliably but costly signaling. Once the tradeoff has stabilized, the composition of branched alkanes is independent of task allocation and thus does not practically change with age or task.

References

- Bello, J. E.; McElfresh, J. S.; Millar, J. G. Isolation and determination of absolute configurations of insect-produced methyl-branched hydrocarbons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, G. J. Biosynthesis of cuticular hydrocarbons. In Insect hydrocarbons: Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemical Ecology; Blomquist, GJ, Bagnères, A-G, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010; pp. pp 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Boulay, R.; Aron, S.; Cerdá, X.; Doums, C.; Graham, P. H.; Hefetz, A.; Monnin, T. Social Life in Arid Environments: The Case Study of Cataglyphis Ants. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas-Vargas, G.; Ocasio-Malavé, C.; Medina, S.; Morales-Guzmán, C.; Del Valle, R. G.; Carballeira, N. M.; Sanabria-Ríos, D. J. Antibacterial fatty acids: An update of possible mechanisms of action and implications in the development of the next-generation of antibacterial agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101093–101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T. B. Spiroplasmas: diversity of arthropod reservoirs and host-parasite relationships. Science 1982, 217, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, F. R.; Jones, G. R.; Destri, S.; Spencer, S. H.; Turillazzi, S. Deciphering the recognition signature within the cuticular chemical profile of paper wasps. Anim. Behav. 2001, 62, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietemann, V.; Peeters, C.; Liebig, J.; Thivet, V.; Holldobler, B. Cuticular hydrocarbons mediate discrimination of reproductives and nonreproductives in the ant Myrmecia Gulosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2003, 100, 10341–10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.; Pomonis, J. G. Physical-properties of insect cuticular hydrocarbons - the effects of chain-length, methyl-branching and unsaturation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995, 112, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A. G. Lipid melting and cuticular permeability: New insights into an old problem. J. Insect Physiol. 2002, 48, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A. G.; Rajpurohit, S. Cuticular lipids and water balance. In Insect hydrocarbons: Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemical Ecology; Blomquist, G, Bagneres, A-G, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2010; p. pp 504. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M. J.; Gordon, D. M. Cuticular hydrocarbons inform task decisions. Nature 2003, 423, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefetz, A. The evolution of hydrocarbon pheromone parsimony in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – interplay of colony odor uniformity and odor idiosyncrasy. A review. Myrmecol. News 2007, 10, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hefetz, A. Ant Behavior; Elsevier, Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hefetz, A.; Wicker Thomas, C.; Bagneres, A. G. Future directions in hydrocarbon research. In Insect hydrocarbons: Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemical Ecology; Blomquist, GJ, Bagnéres, AG, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010; pp. pp 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. A.; Gibbs, A. G. Effect of mating stage on water balance, cuticular hydrocarbons and metabolism in the desert harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex barbatus. J. Insect Physiol. 2004, 50, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koto, A.; Motoyama, N.; Tahara, H.; McGregor, S.; Moriyama, M.; Okabe, T.; Miura, M.; Keller, L. Oxytocin/vasopressin-like peptide inotocin regulates cuticular hydrocarbon synthesis and water balancing in ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2019, 201817788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, S.; Soroker, V.; Hefetz, A.; Vander Meer, R. K. Direct behavioral evidence for hydrocarbons as ant recognition discriminators. Naturwissenschaften 1999, 86, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Conte, Y.; Hefetz, A. Primer pheromones in social Hymenoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2008, 53, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, J.; Amsalem, E. The evolution of queen pheromone production and detection in the reproductive division of labor in social insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2025, 70, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, Y.; Mori, K. Synthesis of the four stereoisomers of 3,12-dimethylheptacosane, (Z)-9-pentacosene and (Z)-9-heptacosene, the cuticular hydrocarbons of the ant, Diacamma sp. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2002, 66, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, M.; Hefetz, A. Neural mechanisms and information processing in recognition systems. Insects 2014, 5, 722–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, M.; Wada-Katsumata, A.; Fujikawa, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Yokohari, F.; Satoji, Y.; Nisimura, T.; Yamaoka, R. Ant nestmate and non-nestmate discrimination by a chemosensory sensillum. Science 2005, 309, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pask, G. M.; Slone, J. D.; Millar, J. G.; et al. Specialized odorant receptors in social insects that detect cuticular hydrocarbon cues and candidate pheromones. Nature Communications 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Tittiger, C.; Wicker-Thomas, C.; et al. An insect-specific P450 oxidative decarbonylase for cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2012, 109, 14858–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oystaeyen, A.; Oliveira, R. C.; Holman, L.; et al. Conserved class of queen pheromones stops social insect workers from reproducing. Science 2014, 343, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wilgenburg, E.; Symonds, M. R. E.; Elgar, M. A. Evolution of cuticular hydrocarbon diversity in ants. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 24, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zweden, J. S.; d’Ettorre, P. Nestmate recognition in social insects and the role of hydrocarbons. In Insect hydrocarbons: Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemical Ecology; Blomquist, GJ, Bagnères, A-G, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010; pp. pp 222–243. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, H.; Ogata, S.; Nodomi, N.; Tateishi, K.; Nishino, H.; Matsubara, R.; Ozaki, M.; Yokohari, F. Cuticular hydrocarbon reception by sensory neurons in basiconic sensilla of the Japanese carpenter ant. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahavi, A. Mate selection: a selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol. 1975, 53, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, A.; Zahavi, A. The handicap principle: A missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 1999. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |