Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The selection of an optimal antifoam is critical for efficient fermentation, as industrial agents often have detrimental side effects like growth inhibition, while some can enhance productivity. This study presents a rational approach to developing and screening novel silicone-polyol antifoam emulsions. A key finding was the discovery of selective antibacterial activity in agent 3L10, which strongly inhibited Gram-positive bacteria (especially Corynebacterium glutamicum) but not Gram-negative strains. This specificity, likely mediated by interaction with the mycolic acid layer of C. glutamicum, highlights the necessity for strain-specific antifoam testing. A comprehensive evaluation protocol—combining chemical design, cytotoxicity screening across diverse microorganisms, determination of minimum effective concentrations (MEC), and validation in model bioreactor fermentations—was established. Through this process, agent 6T80 was identified as a promising candidate. It exhibited low MEC, high emulsion stability, no cytotoxicity, and did not impair growth or recombinant protein production in B. subtilis or P. putida fermentations. The study concludes that agent 6T80 is suitable for further application in processes involving Gram-negative and certain Gram-positive hosts, whereas agent 3L10 serves as a valuable tool for studying surfactant-membrane interactions. The developed methodology enables the targeted selection of highly efficient and biocompatible antifoams for specific biotechnological processes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Relevance of Foam Formation in Biotechnological Processes

1.2. Mechanisms of Foam Formation in Bacterial Cultures

1.3. Classification and Mechanisms of Action of Antifoams

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Antifoam Agents

2.2. Inhibition of Growth on Plates

2.3. Comparison of the Growth Rate

2.4. Determination of the Effective Concentration of Antifoams in a Conical Tube

2.5. Comparative Analysis of Culture Growth in Small Parallel Bioreactors

2.6. Assessment of the Antifoam Agent's Impact on Glycerol Dehydrogenase Biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida cells as a Model

3. Results

3.1. Formation of Antifoam Agents

3.2. Inhibition of Growth on Plates

3.3. Assessment of the Effect of Antifoam Agents on the Growth of the Tested Bacterial Strains

3.4. Determination of the Effective Concentration of Antifoams in a Conical Tube

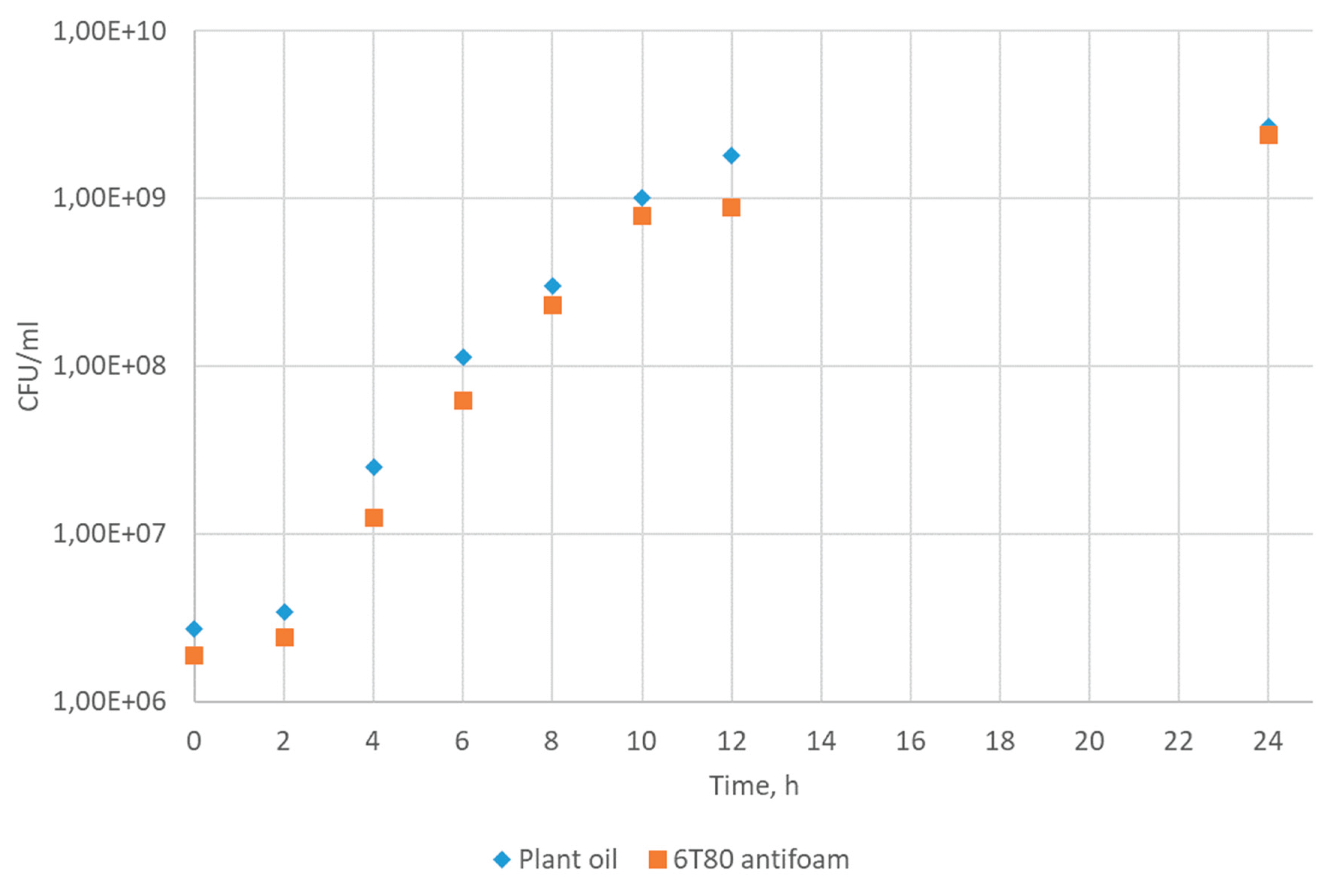

3.5. Assessment of the Effect of Antifoam Agents on Cultivation of Bacillus subtilis MGMM38 Strain in Small Parallel Bioreactors

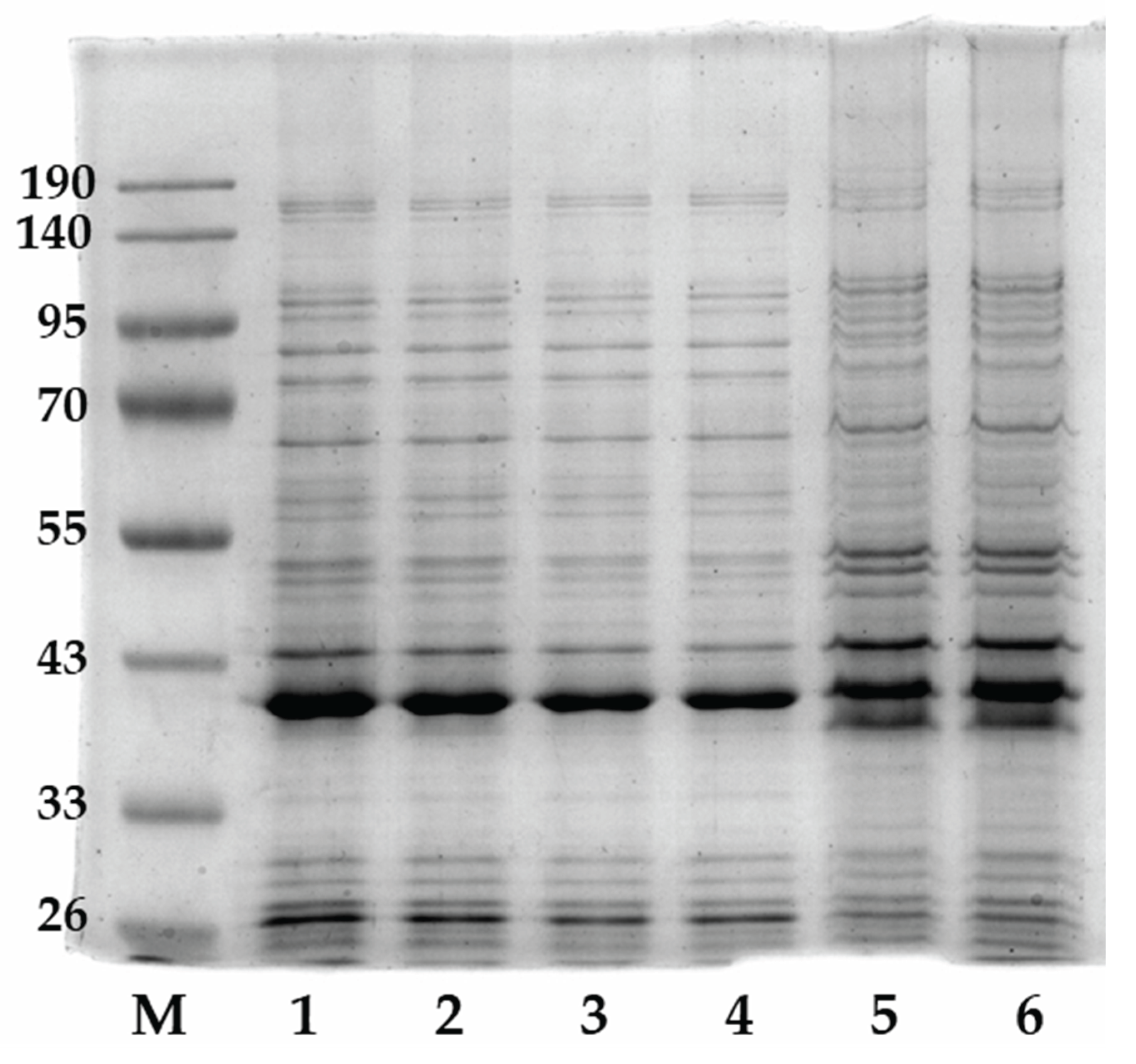

3.6. Assessment of the Antifoam Agent's Impact on the Glycerol Dehydrogenase Biosynthesis in Cells P. putida LN6160 Strain as a Model System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Routledge, S.J. Beyond de-foaming: the effects of antifoams on bioprocess productivity. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2012, 3(4), e201210014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Fermentation Defoamer Market – Industry Trends and Forecast to 2028. Available online: https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/global-fermentation-defoamer-market (accessed on 20.12.2025).

- Gong, Z.; Yang, G.; Che, C.; Liu, J.; Si, M.; He, Q. Foaming of rhamnolipids fermentation: impact factors and fermentation strategies. Microb Cell Fact. 2021, 20(1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delvigne, F.; Takors, R; Mudde, R; Gulik, W; Noorman, H. Bioprocess scale-up/down as integrative enabling technology: from fluid mechanics to systems biology and beyond. Microbal Biotech. 2017, 10(5), 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonester, D.; Hoffman, K.; Palmen, T.; Regestein, L.; Richter, U.; Altenoff, A.; Hoffman, M.; Radeva, Y.; Buchs, J.; Magnus, J.B. Foam Formation in Shake Flasks and Its Consequences. Eng. Life Sci. 2025, 25(10), e70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Liu, Y.A.; Dooley, L.; McDowell, C.; Thaysen, M. Large-Scale Industrial Fermenter Foaming Control: Automated Machine Learning for Antifoam Prediction and Defoaming Process Implementation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61(15), 5227–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesono, S; Onodera, M; Toda, K; Yoshida, M; Yamagiwa, K; Ohkawa, A. Improvement of foam breaking and oxygen-transfer performance in a stirred-tank fermenter. Bioproc Biosyst Eng. 2006, 28(4), 235–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, S.; Maschke, R. W.; Werner, S.; Jossen, V.; Eibl, D. Oxygen mass transfer in biopharmaceutical processes: numerical and experimental approaches. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2021, 93(1-2), 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. C.; Senne de Oliveira Lino, F.; Rasmussen, T. G.; Thykær, J.; Workman, C. T.; Basso, T. O. Industrial antifoam agents impair ethanol fermentation and induce stress responses in yeast cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101(22), 8237–8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesken, C. C.; Bator, I.; Eberlein, C.; Heipieper, H. J.; Tiso, T.; Blank, L. M. Genetic cell-surface modification for optimized foam fractionation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 572892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Singha, L. P.; Shukla, P. Biotechnological potential of microbial bio-surfactants, their significance, and diverse applications. FEMS microb. 2023, 4, xtad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, M.; Kungurov, G.A.; Valiakhmetov, E.E.; Gogov, A.S.; Trachtmann, N.V.; Validov, S.Z. Construction of the Pseudomonas putida Strain with Low Motility and Reduced Biofilm Formation for Application in Fermentation. Fermentation 2024, 10, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yang, G.; Che, C.; Liu, J.; Si, M.; He, Q. Foaming of rhamnolipids fermentation: impact factors and fermentation strategies. Microb. Cell Fact 2021, 20(1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailovskaya, A.; Chatzigiannakis, E.; Renggli, D.; Vermant, J.; Monteux, C. From individual liquid films to macroscopic foam dynamics: A comparison between polymers and a nonionic surfactant. Langmuir 2022, 38(35), 10768–10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaee, M.; Aider, M. Potential Use of Nonanimal-Based Biopolymers as Gelling/Emulsifying Stabilizing Agents to Reduce the Fat Content in Foods: A Review. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2(5), 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Neef, T.; Schroën, K.; de Ruiter, J. Mapping Bubble Formation and Coalescence in a Tubular Cross-Flow Membrane Foaming System. Membranes 2021, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; He, L.; Luo, X. Foaming of Oils: Effect of Poly(dimethylsiloxanes) and Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2019, 4(4), 6502–6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, D.A.; Bittencourt, R.R.; Mansur, C.R.E. Evaluation of the efficiency of polyether-based antifoams for crude oil. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2011, 76(3-4), 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xue, C.; Ji, D.; Gong, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Microscopic Understanding of Interfacial Performance and Antifoaming Mechanism of REP Type Block Polyether Nonionic Surfactants. Molecules 2024, 29, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Sanguramath, R.A.; Israel, S.; Silverstein, M.S. Emulsion Templating: Porous Polymers and Beyond. Macromolecules 2019, 52(15), 5445–5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthimiou, G.; Thumser, A.E.; Avignone-Rossa, C.A. A novel finding that Streptomyces clavuligerus can produce the antibiotic clavulanic acid using olive oil as a sole carbon source. J Appl Microbiol. 2008, 105(6), 2058–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrede, C.J.; Coelho, A.L.S.; Feuser, P.E.; Andrade, L.M.; Carciofi, B.A.M.; Oliveira, D. Mannosylerythritol lipids: production, downstream processing, and potential applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 77, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiso, T.; Demling, F.; Karmainski, T.; Oraby, A.; Eiken, J.; Liu, L.; Bongartz, P.; Wessling, M.; Desmond, P.; Schmitz, S.; Weiser, S.; Emde, F.; Czech, H.; Merz, J.; Zibek, S.; Blank, L.M.; Regestein, L. Foam control in biotechnological processes—challenges and opportunities. Discov. chem. eng. 2024, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etoc, A.; Delvigne, F.; Lecomte, J.P.; Thonart, P. Foam Control in Fermentation Bioprocess. In Twenty-Seventh Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals. ABAB Symposium; McMillan, J.D., Adney, W.S., Mielenz, J.R., Klasson, K.T., Eds.; Humana Press, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghildyal, N. P.; Lonsane, B. K.; Karanth, N. G. Foam control in submerged fer-mentation: state of the art. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 1988, 33, 173–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilieva, E. A.; Vasileva, L. A.; Zagidullin, A. A.; Davlitova, E. M.; Valeeva, F. G.; Krylov, F. D.; Ardabevskaia, S.N.; Milenin, S.A.; Nizameev, I.R.; Zakharova, L. Y. Structure–property correlation of amphiphilic alkylthio derivatives of carboxylic acids: from self-assembly to functional activity. Surf. Inter. 2025, 77, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, M.; Altenbuchner, J. The Escherichia coli rhamnose promoter rhaP BAD is in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 independent of Crp–cAMP activation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2010, 85(6), 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawase, Y.; Moo-Young, M. The effect of antifoam agents on mass transfer in bioreactors. Bioprocess Eng. 1990, 5, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanéelle, M.A.; Tropis, M.; Daffé, M. Current knowledge on mycolic acids in Corynebacterium glutamicum and their relevance for biotechnological processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2013, 97, 9923–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition | Water | Tw80 | PDMS200 | 2-HDol | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D | SiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | ||||||||||

| 1T80 | 25 | 10 | 10 | 35 | 20 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3T80 | - | 20 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 3T80-SiO2 | 30 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |||

| 4T80 | 10 | - | 20 | - | - | - | - | |||

| 4T80-SiO2 | - | 20 | - | - | - | 1 | ||||

| 5T80 | - | - | 20 | - | - | - | ||||

| 6T80 | 25 | 10 | 10 | 35 | - | - | 20 | - | - | 1 |

| 7T80 | - | - | - | 20 | - | - | ||||

| 9T80 | - | - | - | - | 20 | - | ||||

| 3L10 | 25 | 10 (L-10) | 10 | 35 | - | 20 | - | - | - | - |

| Strain | Cultivation Medium | Cultivation Conditions | Source Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli BL21 | Luria-Bertani | 37°C | [17] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum MGMM638 | MRS | 37°C | [18] |

| Trichoderma viride MGMMF32 | King's B | 30°C | [19] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens MGMM121 | King's B | 25°C | [20] |

| Bacillus subtilis MGMM36 | King's B | 30°C | [21] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum MGMM126 | King's B | 30°C | [22] |

| Antifoam Agent | Added Volume, µL | Concentration in Solution, % (v/v) |

|---|---|---|

| Plant oil | 80 | 0.267 |

| 1T80 | 20 | 0.067 |

| 3T80 | 40 | 0.133 |

| 3T80-SiO2 | 40 | 0.133 |

| 4T80 | 40 | 0.133 |

| 4T80-SiO2 | 40 | 0.133 |

| 5T80 | 40 | 0.133 |

| 6T80 | 20 | 0.067 |

| 7T80 | 60 | 0.200 |

| 9T80 | 40 | 0.133 |

| 3L10 | 20 | 0.067 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).