1. Introduction

Structural, economic and demographic changes have been driving up the urban population densities in South-East Asian cities. Just recently, Jakarta surpassed Tokyo as the most populous city globally [

1]. Economic growth and rising demand for residential, commercial and industrials spaces have reduced the availability of agricultural land. Back in the 1960s, approximately 25% of Singapore’s total land area was dedicated to agriculture. Singapore was entirely self-sufficient in poultry and eggs, while also producing 30-50% of its fish and vegetable needs. Currently Singapore stands as a metropolitan city with only 1% of land area allocated for farming [

2]. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused severe disruption of imports, emphasizing the importance of food security as a critical national priority [

3]. Despite substantial effort on supporting schemes for local agriculture, including the allocation and tendering land space in Lim Chu Kang for farming activities, there has not been a corresponding increase in domestic crop production. Consequently, Singapore remains highly dependent on imports from neighboring countries like Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia [

4]. Several initiatives were initiated to incorporate upcoming farming technologies in local farms. The implementation of Vertical farming systems (VFs) as well as automation such as moving gullies in conventional greenhouses in the Lim Chu Kang and Neo Tiew area are some examples of this initiative. A concurrent growing practice is the Building Integrated Agriculture (BIA) [

5], in the form of community gardens that engage residents in farming activities at locations such as the upper deck of multi-storey car parks, temporary vacant sites of schools, as well as industrial estates. These solutions aim at creating self-sustaining systems that use building resource outflows (water, energy) for food production, boosting urban food security, reducing food miles, and creating greener cities.

However, several inherent challenges and concerns affect expansion of these technologies. The naturally hot and humid climate in Singapore, which is currently suboptimal for crop cultivation, has been projected to intensify further over time. Plant heat stress is a significant challenge in Singapore’s farming systems due to its hot, humid climate. Local greenhouses are constructed with common materials like polycarbonate or glass, which are prone to trapping heat, elevating internal temperatures beyond optimum thresholds for plant growth. Extensive concrete and glass surfaces in residential areas has further exacerbated the urban heat island (UHI) effect [

4,

6], contributing to increased temperatures in urban areas. These common building materials lack effective cooling mechanisms, allowing temperatures of enclosed structures such as greenhouses or agricultural setups to reach 37 to 40 °C [

7]. Consequently, the deployment of VFs in urban environments necessitates unique façade structure designs and materials that accommodate local climatic constraints. The next major challenge is the high domestic labor cost which demands cost-effective automation for day-to-day greenhouse operation [

8]. The high startup capital expenditure is a strong deterring factor for setting up large-scale automated farms as the generated agricultural produce typically does not result in a return of investment. Most critically, the high domestic operational costs, including utility bills (electricity and water), increase the variable cost of production and make it challenging for local farmers to compete with imports. One potential strategy to minimize the operational cost is designing a structure that reduces the need for indoor cooling and artificial lighting.

In this work, a building-integrated, terrain-adaptable, modular farm design is demonstrated in an area with limited ground space. The modular farm also features automation functionalities like sensor-controlled ventilation and auto-dispensing of nutrients and water. A UCNP film frame was integrated into modular farm for growth in soil-based planter box unit to combat the challenges of plant heat stress. The research also utilizes continuous video imaging to monitor crop growth, allowing for the assessment of crop health and the determination of optimal harvesting times using A Frame farm unit structure. A photovoltaic array with integrated batteries installed on the roof and equipped with an inverter, powers the ventilation fans and environmental (temperature, humidity) sensors in the farm. The research therefore addresses the definition of the design of the modular system affects its performances in terms of land use, labor and utility costs.

2. Materials and Methods

A terrace-stepped area at the back of the university campus (SIT@Dover, 10 Dover Road s139660, 1.310° N, 103.780° E) was chosen as the building site of the modular farm. This area was assessed and a 3D BIM design model was created as presented in

Figure 1(a). 3D BIM modelling enabled the flexible customization of the modular parts, including various component elements such as the base collar, scaffolding poles and base plates. Each component element can be connected in the 3D model to create the modular farming structure. The base collar connects the mesh base plate with the vertical scaffold poles. The scaffolding poles form the main frame of the modular farm and the base plate enables even load distribution by providing a flat weight bearing surface. Concrete slabs (identified by circles in

Figure 1c) support the base of the structure, spreading out the load to prevent the sinking of the vertical scaffold poles into the compacted soil (ground) [

9].

Adjustable louvres allows the angle of the side-facade polycarbonate panels to be tilted to alter the volume of airflow in the enclosure. Prior work has reported on the tilt angle of the louvres at 25°, 45° and 60° and ideal air velocity of 0.3 to 0.5m/s was achieved at the height of 1.35m from the floor level with a tilt angle of 45° [

10]. Anemometers were installed to measure the airflow in the modular farm to keep the air regulation between 0.3 to 0.6 m/s by adjusting the tilt angle of the louvres. Airflow is important for healthy crop growth because it impacts heat transfer from the leaf, photosynthesis and transpiration rates. In stagnant air, microclimates form around the plant, creating a layer of stationary air around the leaves. This boundary layer can slow the diffusion of gases into and out of the leaf. Stomata are pores, where carbon dioxide enters the leaf for photosynthesis while water vapor exits through the process of transpiration. In semi-controlled environments such as modular greenhouse, proper airflow plays an important role in creating a physical environment that improves plant growth through increased heat dissipation, photosynthesis and transpiration rates. As air flows past the surface of the leaf, the boundary layer is disrupted, enabling faster diffusion of heat and gases into and out of the leaf. This is ideal for leafy plant growth [

11].

To ensure the crops receive an adequate amount of solar irradiance, the Quantum Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) meter was used for measurement of Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density (PPFD). In tropical climate like Singapore, Day Light Integral (DLI) targets of 10 to 12.5 mol.m

2.d

-1 at the plant’s canopy can be easily achieved for most of the year [

12]. The construction condition to achieve this ideal DLI range is to have the structure built facing either the east or west direction, enabling the crops to receive half a day of direct sunlight. The modular farm at SIT@Dover was built to fulfil this requirement. The concept of this modular farm is to demonstrate the ability to build an outdoor greenhouse without the need for energy intensive cooling and the use of growth lights. Within the farm, PAR meters were placed at each unit of the A-Frames (AFU) and Suspended (SFU) planters to ensure that the crops receive adequate amount of sunlight for a day.

The AFU and SFU were irrigated by nutrient film technique (NFT) hydroponics, lowering the amount of water and nutrient supply needed. On the other hand, growth media (compost and cocopeat) was used for the planter farm unit (PFU) with nutrients delivered to the crops via drip irrigation. The nutrient circulation system was operated on an hourly on-off cycle. Intermittent operation also lowers energy consumption, extends pump lifespan and lowers the frequency of preventive pump maintenance, extending the overall cost and operational efficiency.

The modular farm also includes a planter box setup equipped with HOBO MX1101 (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, United States) temperature and humidity sensors to monitor the growing conditions. These measurements enable the calculation of Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD), a key metric that combines air temperature and relative humidity (RH), while leaf surface temperature was recorded using a THERM-Micro Leaf Surface Temperature Measurement sensor (ICT International, Armidale, Australia). For the vapor pressure deficit (VPD) study, 15 Nai Bai seedlings were transplanted into each planter box 14 days post-germination and cultivated for a 28-day growth cycle. Each planter farm unit (PFU), as depicted in

Figure 2, comprised four planter boxes, with each experimental cycle lasting approximately 28 days. The experimental setup included overhead frames above the planter boxes to evaluate the effects of UCNP-coated film, uncoated film, and a control (no film) on plant heat stress mitigation and VPD optimization, as detailed in

Section 3.1. It should be noted that the experimental design did not incorporate randomized switching of film treatments among planter boxes, which is a limitation of the current methodology.

Figure 2.

(a) 2D floor plan of the different types of planter’s layout from A- Frame, Suspended and planter farm unit using hydroponics for the first two and soil based for the latter. (b) pictorial drawing and images of the different types of planters.

Figure 2.

(a) 2D floor plan of the different types of planter’s layout from A- Frame, Suspended and planter farm unit using hydroponics for the first two and soil based for the latter. (b) pictorial drawing and images of the different types of planters.

Figure 3.

(a) Planter box position for growth of Nai Bai with sensor for collection of humidity and temperature in the enclosure (b) Leaf sensors (thermistor) is used for measurement of the leaf surface temperature. (c) data logger and controller setup.

Figure 3.

(a) Planter box position for growth of Nai Bai with sensor for collection of humidity and temperature in the enclosure (b) Leaf sensors (thermistor) is used for measurement of the leaf surface temperature. (c) data logger and controller setup.

To assess how strongly the environment draws moisture from the plants, it is necessary to determine the difference between the plant’s Saturated Vapor Pressure (which can be calculated from the leaf temperature) and the Vapor Pressure of the surrounding air (VPsat – VPair).

The temperature of the saturated microclimate, T

sat, is measured from the surface of the plant leaf. To obtain the V

Psat, equation 1 is applied.

To get V

Pair, the temperature and humidity of the air is inputted into equation 2. The integrated temperature and relative humidity sensors will provide the T

air and RH values.

Therefore, the VPD can be found with the following equation.

High VPD has a negative effect on plant growth as it would induce high stomatal resistance and plant water stress (PWS). Accordingly, VPD should ideally be kept around 1.5kPa [

13]. One of the most common problems encountered when growing crops in enclosed environments like a greenhouse is the high humidity. Moist environments provide a favorable condition for the development of various diseases, leading to significant reduction in product quality and quantity. Therefore, sufficient airflow is important in managing the humidity in the greenhouse. On the other extreme, heatwaves or dry spells between the mid-June to August period which can result in a deficiency of moisture in greenhouses. Hence, it is crucial to have good air circulation in the outdoor modular farm for consistent crop yield across the year by installing ventilation fans. To lower the utility cost, PV with battery storage is integrated into the farm. The PV system is equipped with a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controller to regulate the captured solar irradiance and to store excess energy in the lithium-ion batteries. The power inverter is necessary to convert the DC to AC to power the ventilation fan operation.

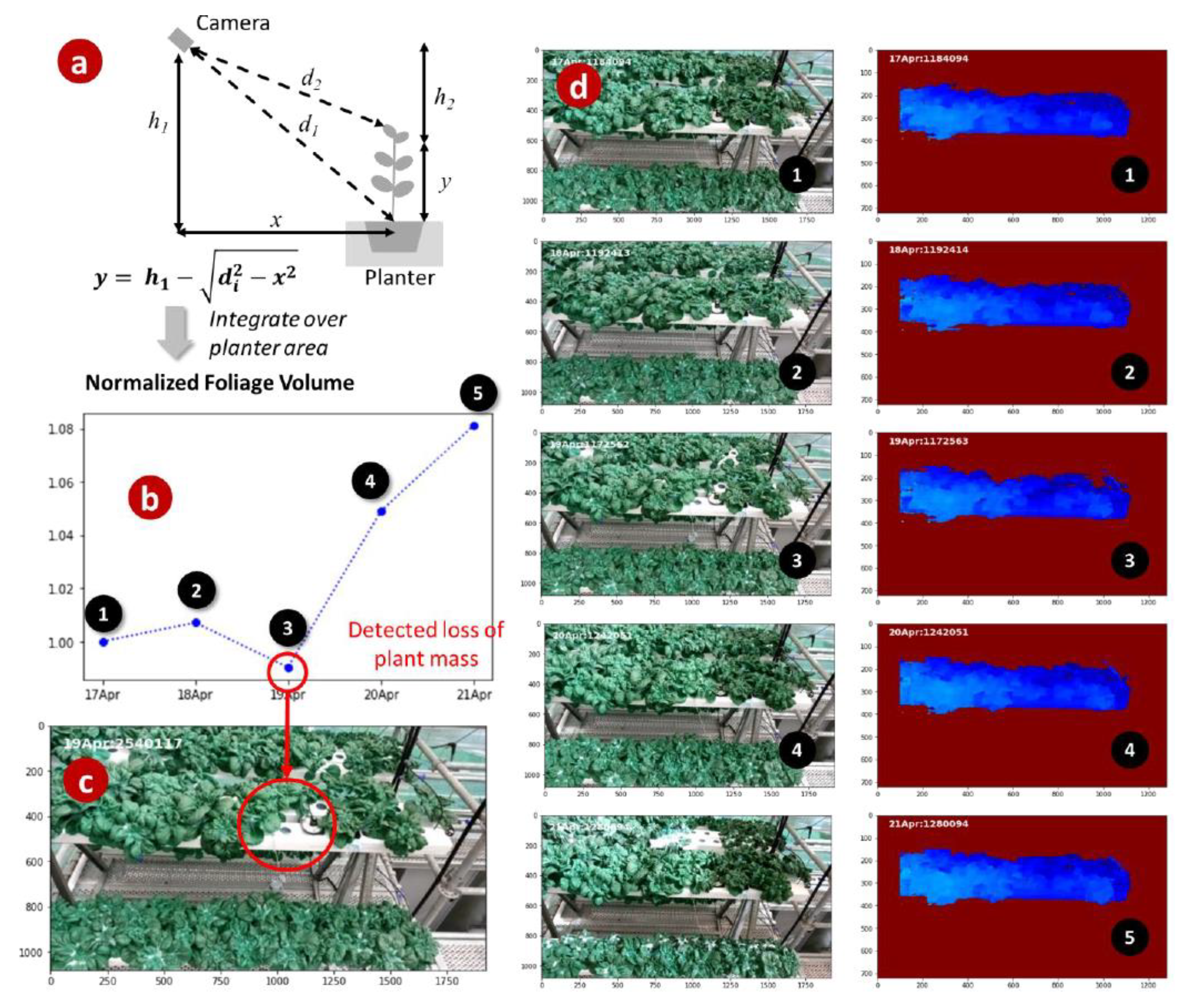

In the farming system, it is important to avoid over maturation of crops, as prolonged growth leads to continued nutrient uptake from the hydroponic solution and can result in increased bitterness in leafy greens. Timely harvesting, therefore, ensures both higher economic returns for farm operators and improved palatability for consumers. To support this objective, two depth-sensing Luxonis OAK-D camera (Luxonis, Westminster, United States) were integrated with Raspberry Pi 3B microprocessors and were deployed on each A-frame structure, as shown in

Figure 4. One camera (

Figure 4a) was installed at a vertical distance of 66 cm and horizontal distance of 98 cm away from the canopy of the Nai Bai plants and the other (

Figure 4b) was at the canopy height and at a horizontal distance of 98 cm away from the AFU. Farm-wide Wi-Fi connectivity enabled data collection and the transmission of alert notifications, while system power was supplied by a solar-powered battery source.

The selected components used to be lightweight, robust, and easily mounted on scaffold poles, demonstrating the practicality and scalability of the deployment. Data were collected across multiple crop growth and harvest cycles. Camera height and orientation were carefully adjusted to capture all planters within the field of view while maintaining alignment along the vertical centre of the rack. Colour, stereo, and depth-disparity data were continuously captured and stored locally on the Raspberry Pi. Images were saved in NumPy array format to improve processing efficiency and reduce storage requirements. The complete image dataset was retained to support subsequent data analysis and model development across the harvesting cycle of the farm.

The AFU has three tiers; top, middle and bottom at a vertical spacing of 50cm. Each tier has two gullies with 15 planter units per gully. Two batches of Nai Bai growth were grown on the AFU between (i) early Feb to early Mar period and (ii) late Mar to late Apr period and was reported in this work. The young seedlings were transferred two weeks after germination to the AFU and grown by NFT technique.

3. Results and Discussion

Lab-fabricated light-conversion (UCNP) films were used to mitigate the direct heat gain and manipulate the growth environment to achieve optimal PPFD and temperature during the plant’s active photosynthetic time, as reported in previously published work [

14] and the growth result for the average growth cycle is reported in

Section 3.1. In addition, energy utilization within the farming system was evaluated. Photovoltaic (PV) panels were integrated into the farm system, providing a source for the energy enhancement needed to achieve net-zero energy farming as reported in

Section 3.2. As the PV system generates electrical energy in the form of direct current (DC), an inverter is required to convert the harvested energy into alternating current (AC) suitable for powering the equipment in the farm. Finally, the implementation and application of video analytics for continuous monitoring of the plant growth in the farming setup will be discussed in

Section 3.3.

3.1. Growth of Nai Bai with Overhead UCNP Film Frame

Farmers in Singapore use high-tech, land-efficient setups like vertical farms and hydroponics in controlled environment greenhouses that include growth LEDs and sophisticated IoT systems. There are also some soil-based farms that employ all-encompassing netting for pest prevention. However, trapped heat remains a persistent issue. Farmers attempt to mitigate the heat by energy intensive methods like heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), chillers, and cooling pads, which increases their operating costs exponentially. In this section, we migitate crop heat stress with passive intgeration of overhead UCNP film frame for planter farm unit growth for Nai Bai.

3.1.1. Deployment of UCNP Film Frames into Modular Farm

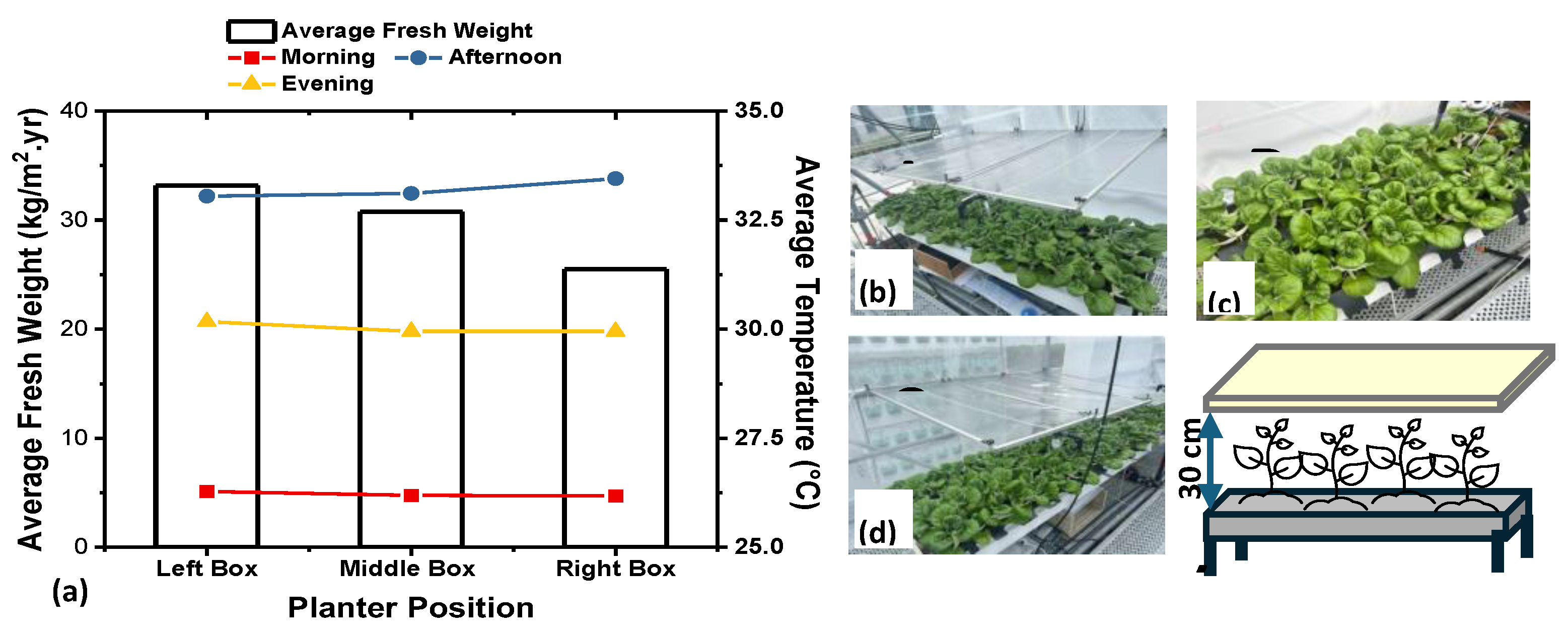

Figure 5(a) shows the histogram plot of the average fresh weight of the Nai Bai and at the various PFUs. The average fresh weight for the L-PFU, C-PFU and R-PFU was 33.15 kg/m

2.yr, 30.76 kg/m

2.yr and 25.51 kg/m

2.yr respectively.

Figure 5(b) to 5(d) show the L-PFU with an overhead frame installed with the UCNP film, the C-PFU with an overhead frame installed with a blank film and the R-PFU with no film acting as the control sample. A schematic of the setup is shown in

Figure 5(e).

The UCNP film is mounted onto an aluminum frame to enable its deployment over the PFU setup. The light conversion film was customized to convert non-usable infrared light (IR) into red visible light for better photosynthesis in the plants [

15]. For a tropical climate like in Singapore, there is strong solar irradiance in the infra-red regime between 0.9µm to 3µm which can lead to higher greenhouse temperatures. The film attempts to reduce this phenomenon. The results in

Figure 5(a) show that the average yield for Nai Bai in the L-PFU is higher than both the C-PFU and R-PFU. This shows that the light conversion film contributes to the enhanced growth of the crops.

The mean temperatures during the specified intervals, morning (10:00–11:00), afternoon (12:00–13:00), and evening (16:00–17:00) were continuously monitored using sensors positioned at the crop canopy level for the three PFU setup for the growth cycles. The resulting data are presented in

Figure 5(a) There is a decrease of 1.0 °C in the average temperature between the R-PFU and the L-PFU, indicating that the light conversion film has reduced the IR transmittance to the planter box. The corresponding increase the yield of the Nai Bai in the L-PFU implies that some of the IR light has been converted to red light, contributing to an increased plant growth rate. While the overhead blank film also provides a reduction in the heat transmitted, and better yield, there is a 7.7% increase in yield with the addition of the light conversion material on the L-PFU. Overall, the Nai Bai in the L-PFU has a 30% increase in yield as compared to the control in the R-PFU.

3.1.2. VPD at the Modular Farm with Different Film Frames

Understanding crop physiology in relation to vapor pressure deficit (VPD) is essential for optimizing growth conditions within the microclimate of the modular farm. Singapore often experiences extreme weather conditions such as prolonged dry spells between May to August, followed by intense rainfall during the monsoon season. These weather changes can adversely affect crop yields over the year. This poses a challenge to microclimate control due to the constant changing ambient conditions. However, maintaining VPD within an optimal range is critical for healthy plant development. When VPD is too low, typically associated with humidity levels approaching 100%, plants struggle to transport nutrients efficiently to the leaves. This condition impairs water movement within the plant, resulting in physiological stress. Conversely, excessively high VPD during dry weather forces plants to transpire at elevated rates, leading to increased water loss through the stomata. If the root system or water supply cannot compensate for this loss, plants may wilt as the rate of water uptake falls short of demand. Both extremes of low and high VPD negatively impact crop health and productivity, highlighting the importance of precise environmental control in vertical farming systems [

16].

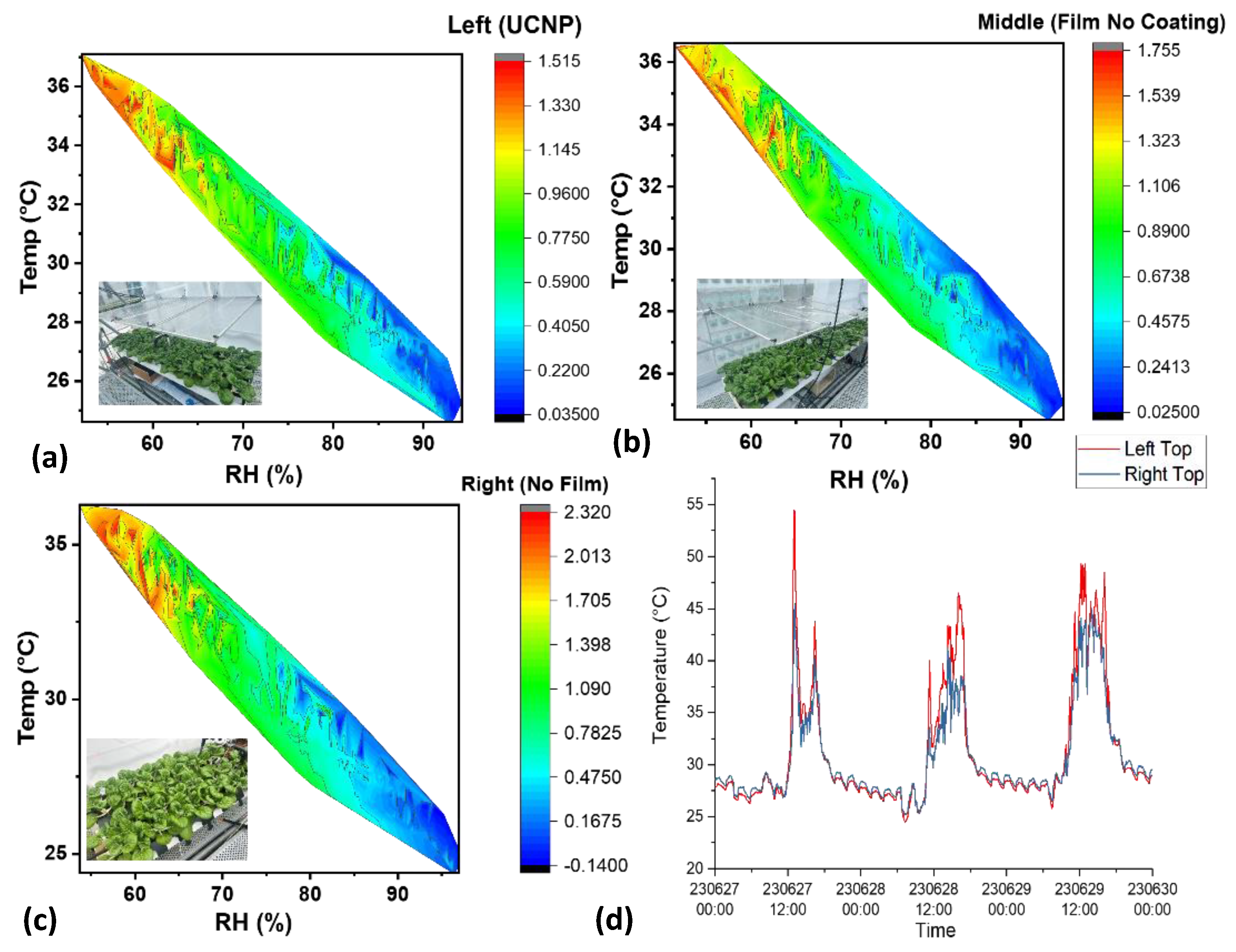

Optimal development of leafy greens is achieved when VPD is maintained within the range of 0.8 to 1.2 kPa, particularly during the mature growth stage [

17,

18]. Over the 28-day growth cycle, the VPD contour map was generated for different permutation of temperature versus relative humidity using equations 1 to 3. This captures the dynamic microclimate conditions experienced by the crops during their growth cycle. By calculating the VPD values across different combinations of humidity and temperature, we produced 2D contour maps (Figure 6a–6c) for each PFU. These maps feature a circled red region that highlights the optimal VPD range. For the growth of Nai Bai in the PFUs, the maximum temperatures recorded from the VPD plots showed a progressive increase: the R-PFU peaked at 36 °C (

Figure 6a) , the C-PFU at 36.5 °C (

Figure 6b), and the L-PFU (

Figure 6c) reached 37 °C. Notably in

Figure 6(a), the L-PFU displays the largest area within this optimal zone, indicating more favorable conditions for crop growth when an overhead UCNP film frame is mounted 30cm above the planter bed despite the higher ambient temperature at the left wing which can reach a max of 37 °C.

Figure 6(d) illustrates a 4 °C to 5 °C ambient temperature difference between the left and right wings of the modular farm across 3-days, as measured by roof-mounted temperature sensors. Despite this disparity in the ambient conditions, the temperature variation among the three PFUs was minimal, with the L-PFU (with overhead UCNP film) only registering a maximum temperature 1 °C higher than the control R-PFU. This indicates effective heat shielding and consequently lower leaf surface temperatures, highlighting the significance of the UCNP film’s contribution to heat mitigation in the modular farm. Correspondingly, the maximum VPD values decreased from 2.32 kPa in the R-PFU (control) to 1.788 kPa in the C-PFU and 1.515 kPa in the UCNP-covered L-PFU, bringing climatic conditions closer to the optimal range of 0.8 to 1.2 kPa.

3.2. Photovoltaics (PV) and Battery Integration for Self-Sustaining Ventilation and Misting System

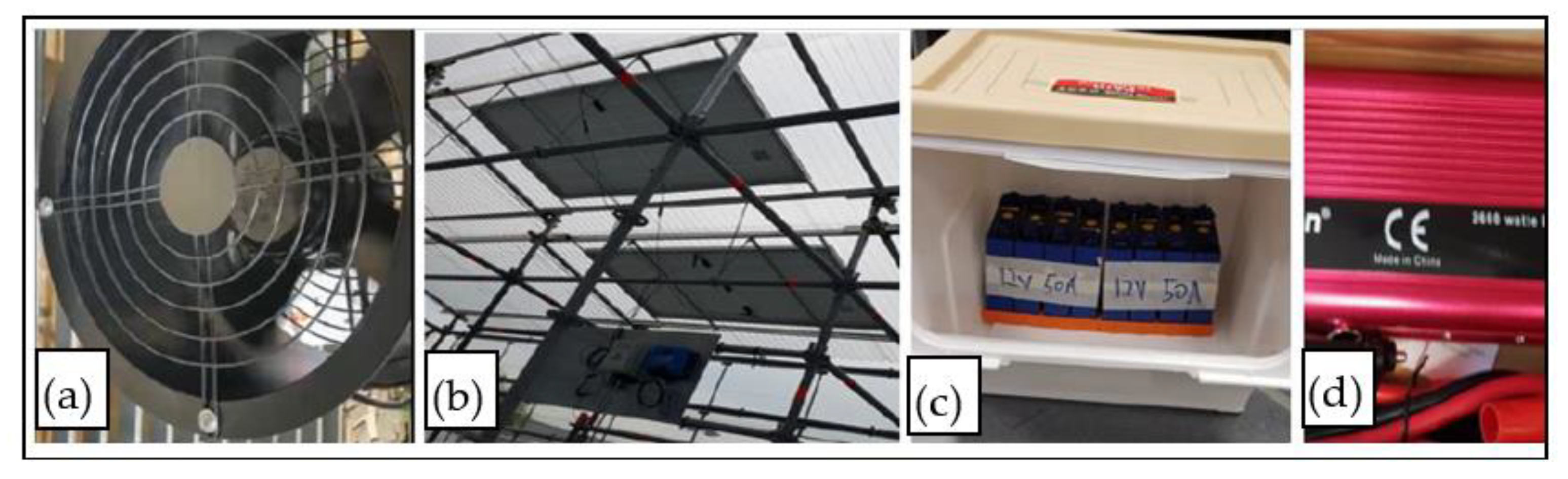

To regulate the airflow in the modular farm, two exhaust fans are installed. Each fan has a rotational speed of 2550 RPM and an air flow of 0.566 m

3/s. The fans use a single-phase 220/230 VAC (50 Hz) motor with an operation current of 0.62 A and power of 136 W. Two 1m x 2m photovoltaic (PV) panels are mounted on the roof of the modular farm 2.5 m above the planter units. Considering that the monocrystalline panel has an average efficiency, η = 20%, an irradiance of G = 1000 W/m

2 with an area of 2m

2, the rated power output per PV panels is about 400 W using equation 4.

The daily energy output depends on the amount of available sunlight, typically measured as peak sun hours (taken to be about 5 hours as Singapore lies in the equatorial region). The energy generated for each panel is approximately 2.0 kWh per day on average and 4.0kWh in total with two panels to form a PV array . Batteries are employed to store excess energy that can make up for the energy needs during non-peak hours (

Figure 7)

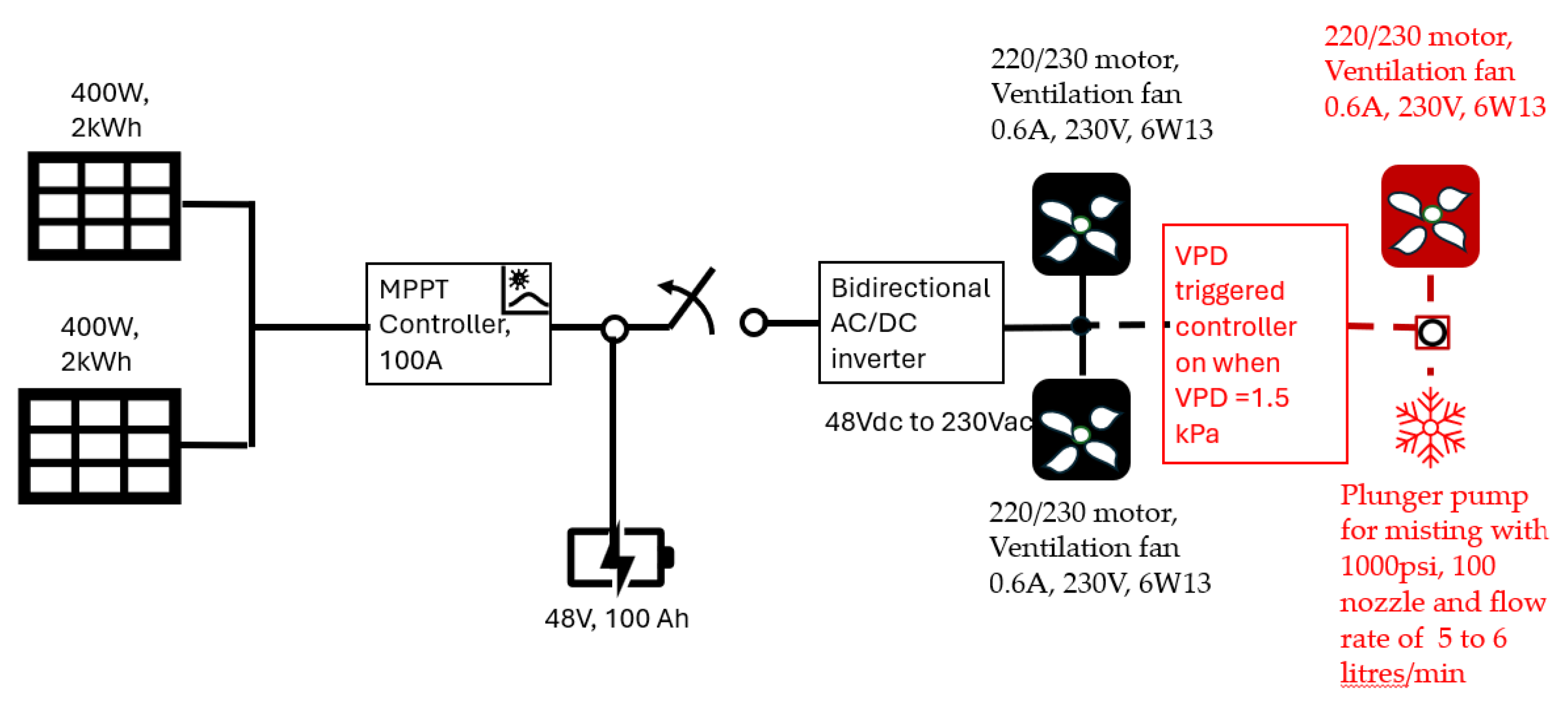

The single line diagram shared on the electrical asset as shown in

Figure 8. The monocrystalline PV array generate 4.0 kWh @ 48 V nominal (approx.) and hence the DC current per array ≈ 4000 W ÷ 48 V = 83 A (approx).Given the need for conservative design margins in photovoltaic short-circuit current and MPPT ratings, the selected controller must be capable of handling continuous currents exceeding 83 A while providing an adequate open-circuit voltage (Voc) margin. Accordingly, the Victron SmartSolar MPPT 150/100, rated for a 100 A output current and a maximum Voc of 150 V, was selected for this system. This configuration ensures that the PV system can reliably operate within safe limits while effectively harvesting solar energy at its maximum power point. For the battery bank, a 48 V, 100 Ah battery array was selected to balance practical deployment considerations as In Singapore, due to passing cloud cover, solar irradiance fluctuate with time and the dynamic power harness by PV fluctuate with time. As shown in line diagram (

Figure 8), the power from the PV is used to charge the batteries instead. This configuration provides a nominal capacity of approximately 4.8 kWh, with an estimated usable capacity of 3.84 kWh at 80% depth of discharge (DoD), offering sufficient operational headroom and provide constant power to the two ventilation fans. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO₄) chemistry was chosen due to its suitability for deep-cycle operation and enhanced thermal stability for the intended application.

At such, the system operates two ventilation fans controlled by a timer between 11:00 and 17:00 to mitigate elevated midday temperatures. The average power consumed by the fan,

. Over approximately seven hours of daily operation, the ventilation system which comprises of two fans will demands a total of

1.656 kWh of energy. With consideration of total of 4.0 kWh power generation from PV array and an estimated usable capacity of 3.84 kWh at 80% depth of discharge (DoD) of battery, this is more than sufficient to operate the ventilation fan system. As the electrical system operates independently of the grid, surplus energy can be utilized to activate additional ventilation fans in response to increased cooling demand, as illustrated in

Figure 8

Based on the above results, this study proposes a data-driven approach to microclimate control in which existing vapor pressure deficit (VPD) mapping results (

Figure 6), derived from combinations of leaf surface temperature and ambient humidity, can be used to control ventilation and misting systems. Based on predefined VPD thresholds, a ventilation fan can be activated to enhance airflow, while misting can be selectively deployed during hot and dry conditions to increase relative humidity and reduce VPD. Both the ventilation fan and misting pump can be powered by renewable energy stored in the battery system. For large-scale misting configurations (e.g., 100 nozzles), a high-pressure plunger pump capable of delivering approximately 4–5.5 L min⁻¹ at pressures of 800 psi or higher is suitable to achieve fine atomization, enabling rapid evaporative cooling without wetting plant surfaces. Given that misting is required only intermittently (typically less than 3 minutes per activation), the associated daily energy demand remains low. Collectively, this framework demonstrates the potential to leverage existing environmental data to fine-tune greenhouse microclimate control and maintain VPD within optimal ranges for crop growth.

3.3. A-Frame Structure for Hydroponic Growth of Leafy Greens in the Left and Right Wings of the Modular Farm

One of the key challenges associated with managing multiple small-scale vertical farms distributed across the island is the limited availability of manpower and resources for continuous monitoring of crop growth conditions. A potential solution lies in the adoption of continuous video monitoring and automation to enable remote supervision and reduce labor demands.

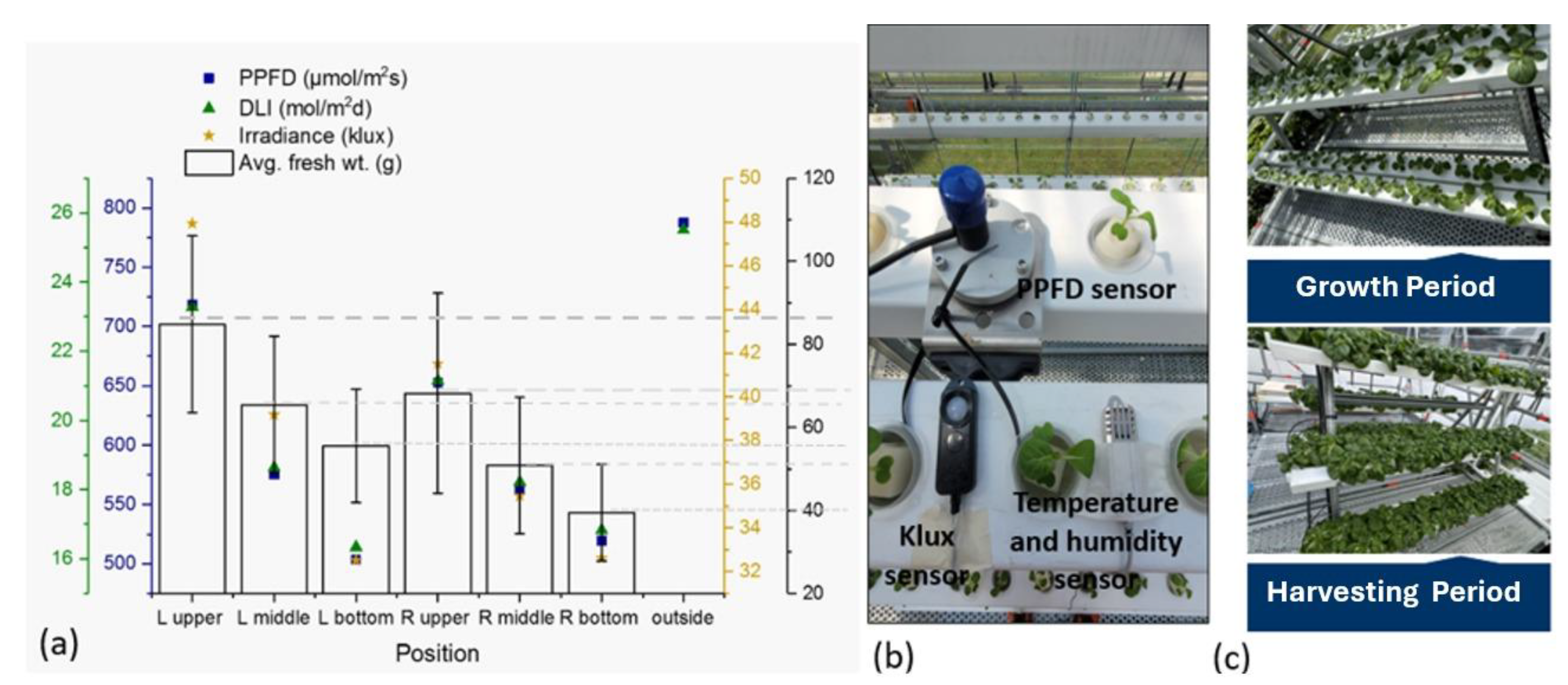

3.3.1. Impact of DLI and Temperature on Average Fresh Weight of Leafy Greens for A-Frame Planter Unit

The first two cultivation batches focused on Nai Bai, with the objective of establishing a benchmark comparison of crop growth between the left and right wings of the modular farm. This comparative study evaluated the relative performance of crops under differing microclimatic conditions. The A-frame configuration was adopted to enhance solar irradiance exposure across multiple vertical levels compared with the vertically suspended planter system (

Figure 2a).

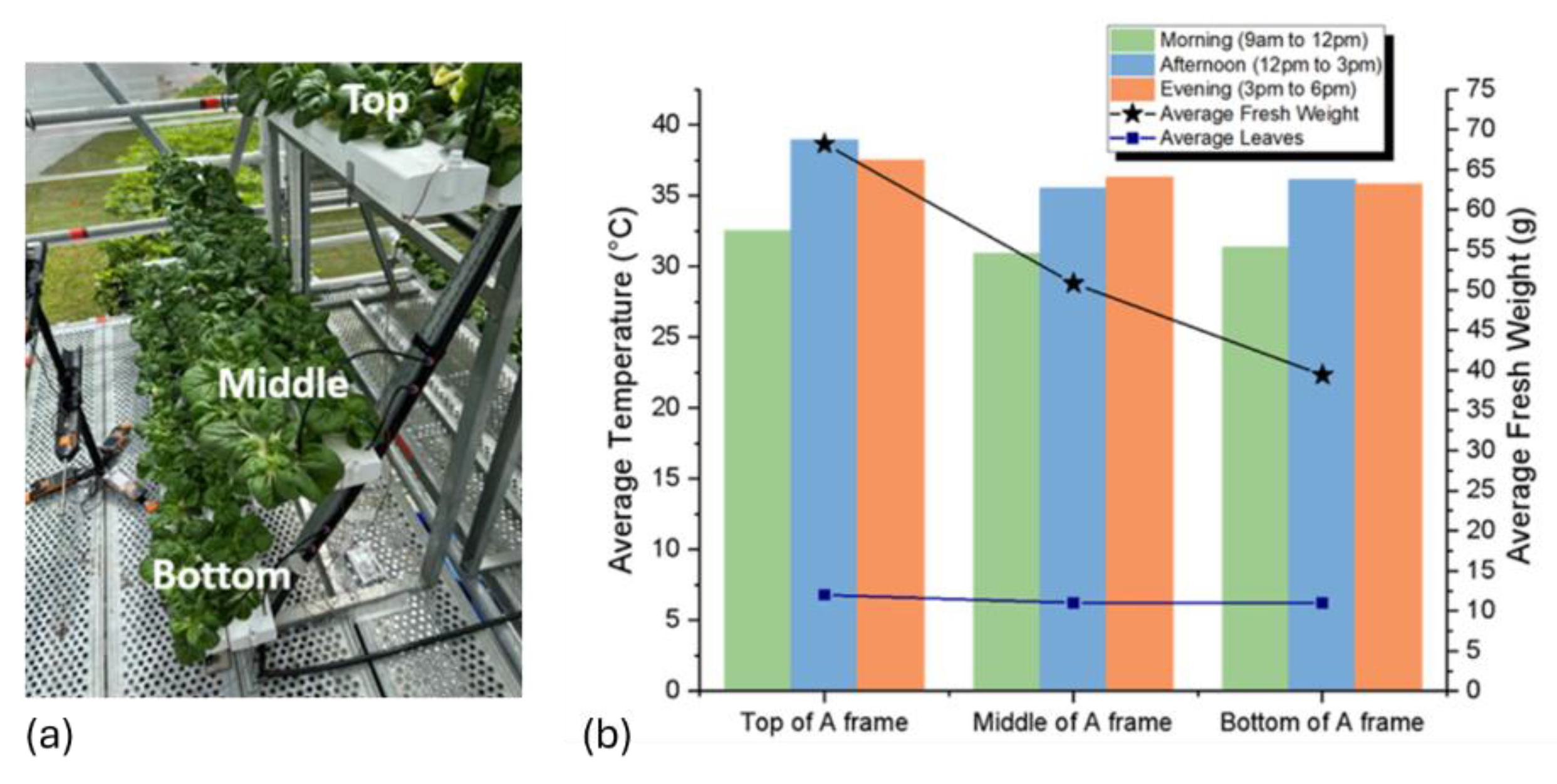

Each A-frame has a total of twelve gullies, with two positioned on each side of the frame at each tier (

Figure 9a). Analysis of average fresh weight across tiers indicated that crops grown on the top tier exhibited significantly higher biomass, with increases of approximately 36% and 70% relative to the middle and lower tiers, respectively (

Figure 9b). This is attributed to the closer proximity of the top tier to the roof and its likelihood of less shading and higher DLI as compared to the middle and lower tiers. The temperature does not have any effect on the different tiers at the same time period of the day. Similarly, the average number of leaves per plant was comparable across all tiers, ranging from approximately 10 to 11 leaves per Nai Bai plant.

Crop growth over the entire harvest cycle was monitored for planter gullies mounted on the A-frame structures. For analytical clarity, the A-frame was subdivided into upper, middle, and lower tiers, with the upper tier on the left wing denoted as L upper, as labeled in

Figure 10 (a). At harvest, the average fresh weight of crops grown on the upper tier of the left wing was 86 g, compared to 68 g on the corresponding upper tier of the right wing. These results corroborate findings from both batches of the growth study, demonstrating a strong correlation between average fresh weight and the daily light integral (DLI) received by the crops. The higher DLI measured on the left wing relative to the right wing contributed to an approximate 20% increase in yield, as indicated by fresh biomass. Photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) sensors were used to quantify the instantaneous

availability of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in the 400–700 nm wavelength range, which is critical for photosynthesis. The DLI was calculated by integrating the measured PPFD over the photoperiod, defined as the duration between time points t

1 and t

2 during which daylight was received by the crops in the modular farm. The DLI was computed using equation 4.

Photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) and solar irradiance were measured using a PAR meter and a lux sensor, respectively, together with temperature and relative humidity sensors. All measurements were logged using a data acquisition system and transmitted to a cloud-based platform for storage and analysis. The placement of the sensors is illustrated in

Figure 10(b). Crop growth on the A-frame structure was documented, corresponding to the growth and harvest stages, during the late March to late April period.

During the crop growth study, it was noted that there were slight differences in the lighting conditions in the left and right wings of the modular farm. Solar irradiance spans a broad spectral range from ultraviolet (UV) to far-infrared wavelengths; however, crop growth primarily relies on visible light, particularly red and blue wavelengths, with only minimal UV exposure required to support healthy development and photosynthesis. As the modular farm operates as an enclosed outdoor system utilizing natural sunlight as the primary light source, it is essential to monitor and mitigate undesirable solar heat gain to prevent excessive thermal accumulation within the enclosure. Observations indicate that during the morning and afternoon periods, temperatures at the bottom tier were slightly higher than those at the middle tier. This temperature elevation can be attributed to radiative heat emission from the metal grating scaffold planks.

3.3.2. Implementation of Visual Imaging for Predictive Harvesting Time for Leafy Green

The depth sensor data provided multiple imaging modes that were combined for analysis in this study. By identifying the spatial position of each planter within the captured images and estimating the corresponding camera-to-object distance, individual planters were accurately segmented for subsequent analysis. To improve frame capture rates, image processing was decoupled from data acquisition. Snapshots of colour (RGB), stereo (mono-left and mono-right), and depth disparity data were acquired, with each image labelled by date, time, and source to provide contextual reference (

Figure 4g).

As shown in

Figure 11(a), depth measurements enabled estimation of foliage height (

) at each point along the planters. Integration of these height profiles across individual planters allowed the calculation and temporal tracking of foliage volume for each tier.

Figure 11(c) presents the normalized daily foliage density over the growth cycle. The representative colour and depth images are collected (as illustrated in

Figure 10(f) and 10(g)). The resulting growth profiles exhibit an initial post-transplantation lag phase, followed by a linear growth period and a plateau corresponding to crop maturity. The normalized foliage volume shows an increasing trend with a dip on the 19

th April (

Figure 11b). Closer examination shows that the removal of a pot was the cause of the dip, which testifies to the sensitivity of the technique for monitoring growth (

Figure 11c). The reduction in the normalized foliage volume on 19th April was registered where the plant was taken out

This methodology supports timely harvest and optimize harvest yield by enabling continuous, real-time monitoring of crop growth dynamics. With the segmented depth area images, this allows the normalized foliage volume to be estimated and plotted in

Figure 11b.

The integration of visual imaging technologies to predict the optimal harvesting time for leafy greens has the potential to substantially reduce the manpower required for routine crop monitoring. Farm technologist can use the image sent from the visual imaging system to identify potential pest issue and reduce the need for regular random check on the modular farm distributed in the urban residential areas This will reduce the manpower demand and can enhance overall productivity of the farm. It can also lower operational costs for farm operators in terms of transport to and from the distributed modular farms. Such advancements are particularly critical for modular farms deployed within satellite residential estates, where workforce and space constraints are often more pronounced. Moreover, the use of predictive imaging supports healthier crop development and facilitates more systematic and effective harvesting and replanting cycles, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and resilient farm management practices.

4. Conclusions

This study provides an initial assessment of the feasibility of integrating modular vertical farming systems into building façades within high-density urban environments, specifically addressing the challenges of land scarcity and food security in cities such as Singapore. By incorporating innovative design features like adjustable polycarbonate louvres for optimized airflow, including flexible use of both hydroponic and soil-based irrigation systems, it is possible to support efficient crop and resource management in constrained urban settings. Based on advanced environmental sensing parameters such as vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), farmers have the capability to remotely monitor and achieve optimal growth conditions.

The deployment of in-house fabricated light-conversion films significantly improved crop performance, achieving approximately 30% higher Nai Bai yield compared to control conditions, alongside a reduction in heat stress. Automated activation of microclimate modifying ventilation and moisture control methods allowed VPD manipulation within the modular farm to achieve values close to the optimal range of 0.8–1.2 kPa. While the deployment of light-conversion films and automated microclimate controls showed promising improvements in crop yield and heat stress mitigation, the absence of randomized control treatments and direct comparison with alternative farming systems limits the strength of these conclusions

Energy sustainability was viable through the integration of solar photovoltaic arrays, battery storage, enabling off-grid operation and adaptability to fluctuating weather conditions. Additionally, the implementation of visual imaging and depth-sensing technologies for predictive harvesting has the potential to reduce labor requirements and improved operational efficiency. However, study did not quantify labor savings against conventional practices, and further validation is required to demonstrate operational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B.S., V.D., and S.-C. C; methodology, C.B.S., B.T.W.A.; software, C.B.T.; validation, B.T.W.A., C.B.T and C.B.S..; formal analysis, H. A., C.B.S., B.T.W.A. and M. D’. O.; investigation, H.A., Y.M.F., G. G. and B.T.W.A.; resources, B.T.W.A., G.G., Y.M.F.; data curation, C.B.S., B.T.W.A., Y.M.F. and C.B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.S., B.T.W.A.; writing—review and editing, B.T.W.A., F.O.; visualization, B.T.W.A., C.B.T.; supervision, H.A., M.C., M. D’. O.; project administration, C.B.S., V.D., F. O. and M. C.; funding acquisition, C.B.S., V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the funding support by (i) Italy Singapore Science and Technology Cooperation, Grant Number R23I0IR035 and (ii) under the Singapore Food Story (SFS) R&D Programme first Grant Call (Theme 1 Sustainable Urban Food Production) Award SFS_RND_SUFP_001_09

References

- United Nations (2025). World Urbanization Prospects 2025: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2025/TR/ NO. 12. New York: United Nations.

- Fujii, T.; Waibel, C.; Du, X.; Shi, Z. Food Self-Sufficiency and Building-Integrated Urban Agriculture: Lessons from Singapore, SMU Economics and Stat. 2025, pp22.

- Tortajada, C.; N.S.W. Lim. Food Security and COVID-19: Impacts and Resilience in Singapore. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2021, 5, 740780. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.740780.

- Mughal, M.O.; Li, X-X.; Leslie K. Norford, Urban heat island mitigation in Singapore: Evaluation using WRF/multilayer urban canopy model and local climate zones, Urban Climate, 2020, 34,100714, ISSN 2212-0955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100714.

- D’Ostuni, M.; Zaffi, L.; Appolloni, E.; Orsini, F. Understanding the complexities of Building-Integrated Agriculture. Can food shape the future built environment, Futures, 2022, 144, 103061.

- Vujovic, S.; Haddad, B.; Karaky, H.; Sebaibi, N.; Boutouil, M. Urban Heat Island: Causes, Consequences, and Mitigation Measures with Emphasis on Reflective and Permeable Pavements. Civil Eng 2021, 2, 459–484. https://doi.org/10.3390/civileng2020026.

- Marsaglia, V. Technological Greenery. Exploring cutting-edge solutions for performant Greenery integration in building envelope design, Energy and Buildings, 2024, 324, 114920. ISSN 0378-7788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114920.

- Li, H.; Guo, Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chow, D. Towards automated greenhouse: A state of the art review on greenhouse monitoring methods and technologies based on internet of things, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2021, 191, 106558, ISSN 0168-1699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106558.

- LAYHER ALLROUND SCAFFOLDING, Catalogue 2021 / 2022 Layher the scaffold System. https://www.layher.co.nz/brochures-catalogues-downloads/.

- William, Y. E.; An, H.; Chien, S.-C.; Soh, C. B.; Ang, B. T. W.; Ishida, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Tan, D.; Tay, R. H. S. Urban-Metabolic Farming Modules on Rooftops for Eco-Resilient Farmscape. Sustainability, 2022, 14(24), 16885. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416885.

- Garland, K. F.; Burnett, S. E.; Stack, L. B.; Zhang, D. Minimum Daily Light Integral for Growing High-quality Coleus. HortTechnology, 2010; 20(5), 929–933. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH.20.5.929.

- Teng, J. W. C.; Soh, C. B.; Devihosur, S. C.; Tay, R. H. S.; Jusuf, S. K. Effects of Agrivolatic Systems on the Surrounding Rooftop Microclimate. Sustainability, 2022, 14(12), 7089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127089.

- Çaylı, A.; Baytorun, A.N. Analysis of climate and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) in a heated multi-span plastic greenhouse, Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 31(6): 2021, Page: 1632-1644 https://doi.org/10.36899/JAPS.2021.6.0367.

- Ang, B. T. W.; Fong, Y. M.; Soh, C. B.; Chien, S-C.; An, H.; Tay, R. H. S. Passive Infrared-to-Visible-Light Upconversion Using NaYF4:Yb,Er Nanoparticle Films for Greenhouse Façades, ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 16, 18851–18860. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.4c02476.

- Vinukonda, A.; Bolledla, N.; Jadi, R. K.; Chinthala, R.; Devadasu, V. R. Synthesis of nanoparticles using advanced techniques, Next Nanotechnology, 2025, 8, 100169, ISSN 2949-8295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxnano.2025.100169.

- Arve, L. E; Kruse, O. M.O.; Tanino, K.K.; Olsen, J.E.; Futsæther, C.; Torre, S. Daily changes in VPD during leaf development in high air humidity increase the stomatal responsiveness to darkness and dry air, Journal of Plant Physiology, 2017, 211, 63-69, ISSN 0176-1617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2016.12.011.

- Inoue T., Sunaga M., Ito M., Yuchen Q., Matsushima Y., Sakoda K. and Yamori W Minimizing VPD Fluctuations Maintains Higher Stomatal Conductance and Photosynthesis, Resulting in Improvement of Plant Growth in Lettuce. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12:646144. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.646144.

- Noh, H., & Lee, J. The Effect of Vapor Pressure Deficit Regulation on the Growth of Tomato Plants Grown in Different Planting Environments. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(7), 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073667.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).