Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Evidence on the Effects of tACS on Experimental and Clinical Pain

2.1. Evidence from Experimental Pain Studies

2.2. Evidence from Chronic Pain Studies

3. Limitations, Sources of Inconsistencies, and Possible Solutions

3.1. Mechanistic Uncertainty Driven by Target and Frequency Variability

3.2. Sources of Inter-Individual Variability

3.3. Mechanistic Uncertainty Due To Lack of Simultaneous Monitoring of Oscillations During tACS

3.4. Phase-Dependent and State-Dependent Modulation in tACS

3.4.1. tACS Interaction with Ongoing Brain Oscillations

3.4.2. Phase Configuration of Multi-Electrode tACS Montages

3.5. Limited Access to Deep-Regions as a Constraint for Pain Modulation

3.6. Methodological Limitations, Blinding Challenges, and Recommendations for Future Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ploner, M.; Sorg, C.; Gross, J. Brain Rhythms of Pain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, P. Rhythms for Cognition: Communication through Coherence. Neuron 2015, 88, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxe, J.J.; Snyder, A.C. The Role of Alpha-Band Brain Oscillations as a Sensory Suppression Mechanism during Selective Attention. Front Psychol 2011, 2, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.; Mazaheri, A. Shaping Functional Architecture by Oscillatory Alpha Activity: Gating by Inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nir, R.-R.; Sinai, A.; Moont, R.; Harari, E.; Yarnitsky, D. Tonic Pain and Continuous EEG: Prediction of Subjective Pain Perception by Alpha-1 Power during Stimulation and at Rest. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, E.S.; Butz, M.; Kahlbrock, N.; Hoogenboom, N.; Brenner, M.; Schnitzler, A. Pre- and Post-Stimulus Alpha Activity Shows Differential Modulation with Spatial Attention during the Processing of Pain. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huneke, N.T.M.; Brown, C.A.; Burford, E.; Watson, A.; Trujillo-Barreto, N.J.; El-Deredy, W.; Jones, A.K.P. Experimental Placebo Analgesia Changes Resting-State Alpha Oscillations. PLoS One 2013, 8, e78278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K.D.; Dubois, M.; Llinás, R.R. Abnormal Thalamocortical Activity in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) Type I. Pain 2010, 150, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnthein, J.; Stern, J.; Aufenberg, C.; Rousson, V.; Jeanmonod, D. Increased EEG Power and Slowed Dominant Frequency in Patients with Neurogenic Pain. Brain 2006, 129, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, A.J.; Thapa, T.; Summers, S.J.; Cavaleri, R.; Fogarty, J.S.; Steiner, G.Z.; Schabrun, S.M.; Seminowicz, D.A. Cerebral Peak Alpha Frequency Reflects Average Pain Severity in a Human Model of Sustained, Musculoskeletal Pain. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 122, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, M.; Wilder-Smith, O.H.; Jongsma, M.L.A.; van den Broeke, E.N.; Arns, M.; van Goor, H.; van Rijn, C.M. Altered Resting State EEG in Chronic Pancreatitis Patients: Toward a Marker for Chronic Pain. J. Pain Res. 2013, 6, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, A.J.; Meeker, T.J.; Rietschel, J.C.; Yoo, S.; Muthulingam, J.; Prokhorenko, M.; Keaser, M.L.; Goodman, R.N.; Mazaheri, A.; Seminowicz, D.A. Cerebral Peak Alpha Frequency Predicts Individual Differences in Pain Sensitivity. Neuroimage 2018, 167, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.A.; Kell, P.A.; Shadlow, J.O.; Rhudy, J.L. Cerebral Peak Alpha Frequency: Associations with Chronic Pain Onset and Pain Modulation. Neurobiol. Pain 2025, 18, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, E.S.; Tiemann, L.; Gil Ávila, C.; Bott, F.S.; Hohn, V.D.; Gross, J.; Ploner, M. Assessing the Predictive Value of Peak Alpha Frequency for the Sensitivity to Pain. Pain 2025, 166, 2076–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bott, F.S.; Zebhauser, P.T.; Hohn, V.D.; Turgut, Ö.; May, E.S.; Tiemann, L.; Gil Ávila, C.; Heitmann, H.; Nickel, M.M.; Day, M.A.; et al. Exploring Electroencephalographic Chronic Pain Biomarkers: A Mega-Analysis. EBioMedicine 2025, 120, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, F.S.; Nickel, M.M.; Hohn, V.D.; May, E.S.; Gil Ávila, C.; Tiemann, L.; Gross, J.; Ploner, M. Local Brain Oscillations and Interregional Connectivity Differentially Serve Sensory and Expectation Effects on Pain. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenefati, G.; Rockholt, M.M.; Ok, D.; McCartin, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, G.; Maslinski, J.; Wang, A.; Chen, B.; Voigt, E.P.; et al. Changes in Alpha, Theta, and Gamma Oscillations in Distinct Cortical Areas Are Associated with Altered Acute Pain Responses in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1278183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, S.P.; Junqueira, Y.N.; Akamatsu, M.A.; Marques, L.M.; Teixeira, A.; Lobo, M.; Mahmoud, M.H.; Omer, W.E.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Fregni, F. Resting-State Electroencephalography Delta and Theta Bands as Compensatory Oscillations in Chronic Neuropathic Pain: A Secondary Data Analysis. Brain Netw. Modul. 2024, 3, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvalkar, P.; Prosky, J.; Chin, G.; Ahmadipour, P.; Sani, O.G.; Desai, M.; Schmitgen, A.; Dawes, H.; Shanechi, M.M.; Starr, P.A.; et al. First-in-Human Prediction of Chronic Pain State Using Intracranial Neural Biomarkers. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikson, M.; Esmaeilpour, Z.; Adair, D.; Kronberg, G.; Tyler, W.J.; Antal, A.; Datta, A.; Sabel, B.A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Loo, C.; et al. Transcranial Electrical Stimulation Nomenclature. Brain Stimul 2019, 12, 1349–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfrich, R.F.; Schneider, T.R.; Rach, S.; Trautmann-Lengsfeld, S.A.; Engel, A.K.; Herrmann, C.S. Entrainment of Brain Oscillations by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Sellers, K.K.; Fröhlich, F. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation Modulates Large-Scale Cortical Network Activity by Network Resonance. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 11262–11275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.A.; Stitt, I.M.; Negahbani, E.; Passey, D.J.; Ahn, S.; Davey, M.; Dannhauer, M.; Doan, T.T.; Hoover, A.C.; Peterchev, A.V.; et al. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation Entrains Alpha Oscillations by Preferential Phase Synchronization of Fast-Spiking Cortical Neurons to Stimulation Waveform. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vossen, A.; Gross, J.; Thut, G. Alpha Power Increase after Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation at Alpha Frequency (α-tACS) Reflects Plastic Changes rather than Entrainment. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, J.; Frohlich, F. Targeting Neural Oscillations with Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Brain Res. 2021, 1765, 147491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathi, Y.; Dissassuca, F.; Ricci, G.; Liberati, G. Individualised Alpha-tACS for Modulating Pain Perception and Neural Oscillations: A Sham-Controlled Study in Healthy Participants. Eur. J. Pain 2025, 29, e70086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendsen, L.J.; Hugh-Jones, S.; Lloyd, D.M. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation at Alpha Frequency Reduces Pain When the Intensity of Pain Is Uncertain. J. Pain 2018, 19, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikarashi, H.; Otsuru, N.; Gomez-Tames, J.; Hirata, A.; Nagasaka, K.; Miyaguchi, S.; Sakurai, N.; Ohno, K.; Kodama, N.; Onishi, H. Modulation of Pain Perception through Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation and Its Nonlinear Relationship with the Simulated Electric Field Magnitude. Eur. J. Pain 2024, 28, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, R.; Lu, X.; Zhan, Y.; Jiang, N.; Peng, W. Alpha Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation Modulates Pain Anticipation and Perception in a Context-Dependent Manner. Pain 2025, 166, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, E.S.; Hohn, V.D.; Nickel, M.M.; Tiemann, L.; Gil Ávila, C.; Heitmann, H.; Sauseng, P.; Ploner, M. Modulating Brain Rhythms of Pain Using Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) - A Sham-Controlled Study in Healthy Human Participants. J. Pain 2021, 22, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zhan, Y.; Jin, R.; Lou, W.; Li, X. Aftereffects of Alpha Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation over the Primary Sensorimotor Cortex on Cortical Processing of Pain. Pain 2023, 164, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

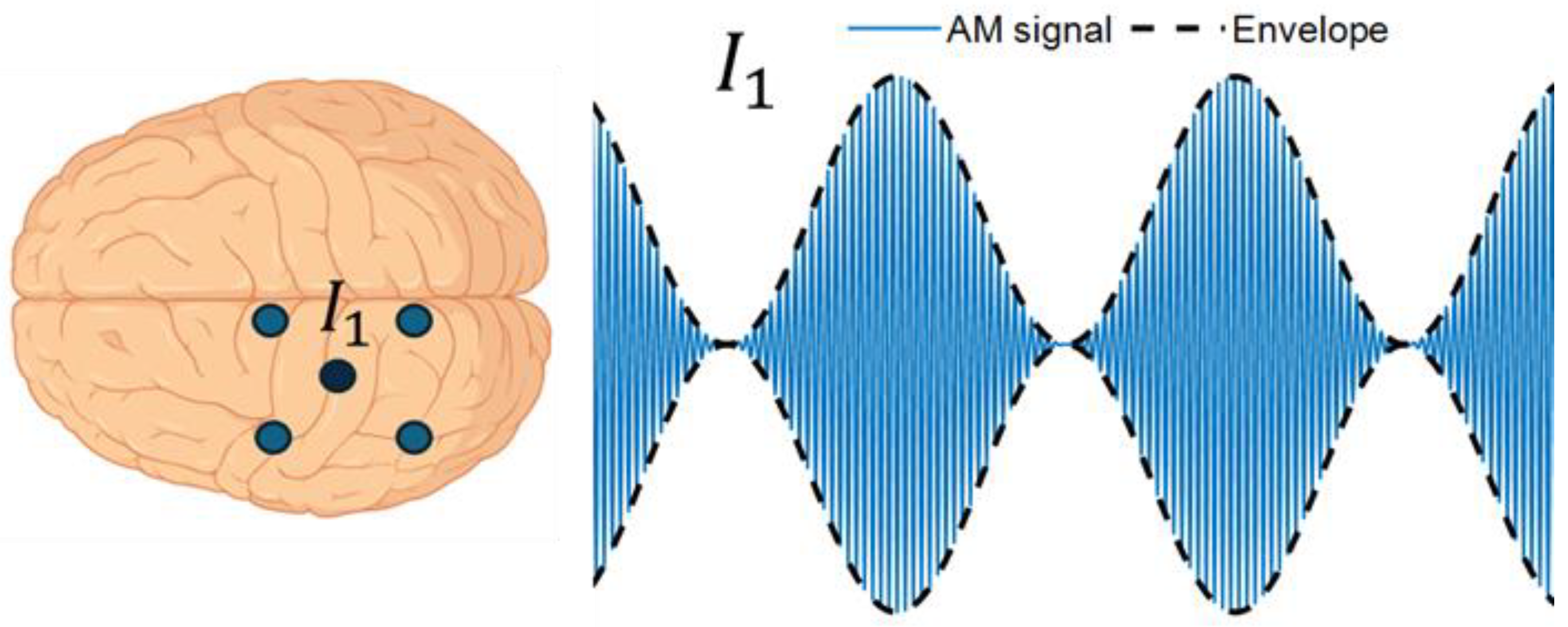

- Qi, X.; Jia, T.; Sun, B.; Xia, J.; Wang, C.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J. Individual Differences in Resting Alpha Band Power and Changes in Theta Band Power during Sustained Pain Are Correlated with the Pain-Relieving Efficacy of Alpha HD-tACS on SM1. Neuroimage 2025, 312, 121237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, H. Analgesic Aftereffects of Alpha High-Definition Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation over the DLPFC during Experimental Pain. Neuroimage 2025, 317, 121332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, N.; Terui, Y. Synchronal Dual Brain Stimulation over the Somatosensory Cortex Modulated Social Touch-Induced Analgesia Depending on Empathy. J. Pain 2025, 105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Prim, J.H.; Alexander, M.L.; McCulloch, K.L.; Fröhlich, F. Identifying and Engaging Neuronal Oscillations by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized, Crossover, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled Pilot Study. J. Pain 2019, 20, 277.e1–e277.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, A.; Bischoff, R.; Stephani, C.; Czesnik, D.; Klinker, F.; Timäus, C.; Chaieb, L.; Paulus, W. Low Intensity, Transcranial, Alternating Current Stimulation Reduces Migraine Attack Burden in a Home Application Set-up: A Double-Blinded, Randomized Feasibility Study. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, L.; Bertuccelli, M.; Formaggio, E.; Rubega, M.; Bosco, G.; Tenconi, E.; Cattelan, M.; Masiero, S.; Del Felice, A. Beyond Physiotherapy and Pharmacological Treatment for Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Tailored tACS as a New Therapeutic Tool. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.P.; Chiu, C.-C.; Chen, S.-C.; Huang, Y.-J.; Lai, C.-H.; Kang, J.-H. Using High-Definition Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation to Treat Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Double-Blinded Controlled Study. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prim, J.H.; Ahn, S.; Davila, M.I.; Alexander, M.L.; McCulloch, K.L.; Fröhlich, F. Targeting the Autonomic Nervous System Balance in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Using Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation: A Randomized, Crossover, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 3265–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashmi, J.A.; Baliki, M.N.; Huang, L.; Baria, A.T.; Torbey, S.; Hermann, K.M.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Apkarian, A.V. Shape Shifting Pain: Chronification of Back Pain Shifts Brain Representation from Nociceptive to Emotional Circuits. Brain 2013, 136, 2751–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliki, M.N.; Petre, B.; Torbey, S.; Herrmann, K.M.; Huang, L.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Fields, H.L.; Apkarian, A.V. Corticostriatal Functional Connectivity Predicts Transition to Chronic Back Pain. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachon-Presseau, E.; Centeno, M.V.; Ren, W.; Berger, S.E.; Tétreault, P.; Ghantous, M.; Baria, A.; Farmer, M.; Baliki, M.N.; Schnitzer, T.J.; et al. The Emotional Brain as a Predictor and Amplifier of Chronic Pain. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliki, M.N.; Mansour, A.R.; Baria, A.T.; Apkarian, A.V. Functional Reorganization of the Default Mode Network across Chronic Pain Conditions. PLoS One 2014, 9, e106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, C.M.; Kelleher, E.; Irani, A.; Schrepf, A.; Clauw, D.J.; Harte, S.E. Deciphering Nociplastic Pain: Clinical Features, Risk Factors and Potential Mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napadow, V.; LaCount, L.; Park, K.; As-Sanie, S.; Clauw, D.J.; Harris, R.E. Intrinsic Brain Connectivity in Fibromyalgia Is Associated with Chronic Pain Intensity. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2545–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, D.-M.; Beissner, F.; Moher Alsady, T.; Lazaridou, A.; Paschali, M.; Berry, M.; Isaro, L.; Grahl, A.; Lee, J.; Wasan, A.D.; et al. A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words: Linking Fibromyalgia Pain Widespreadness from Digital Pain Drawings with Pain Catastrophizing and Brain Cross-Network Connectivity: Linking Fibromyalgia Pain Widespreadness from Digital Pain Drawings with Pain Catastrophizing and Brain Cross-Network Connectivity. Pain 2021, 162, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Kuner, R.; Flor, H. Structural Plasticity and Reorganisation in Chronic Pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiloni, C.; Brancucci, A.; Del Percio, C.; Capotosto, P.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Chen, A.C.N.; Rossini, P.M. Anticipatory Electroencephalography Alpha Rhythm Predicts Subjective Perception of Pain Intensity. J. Pain 2006, 7, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, A.; Peng, W.; Hung, Y.S.; Moayedi, M.; Iannetti, G.D.; Hu, L. Alpha and Gamma Oscillation Amplitudes Synergistically Predict the Perception of Forthcoming Nociceptive Stimuli. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016, 37, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohn, V.D.; May, E.S.; Ploner, M. From Correlation towards Causality: Modulating Brain Rhythms of Pain Using Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Pain Rep. 2019, 4, e723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.C.; Briand, M.-M.; Boudier-Revéret, M.; Yang, S. Effectiveness of Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation for Controlling Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1323520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, M.; Mo, S.; Li, X.; Wang, J. The Effect of Somatosensory Alpha Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation on Pain Empathy Is Trait Empathy and Gender Dependent. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N. Pain Control Based on Oscillatory Brain Activity Using Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation: An Integrative Review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 941979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.; Garcia-Cossio, E.; Chander, B.S.; Braun, C.; Birbaumer, N.; Robinson, S.E.; Soekadar, S.R. Mapping Entrained Brain Oscillations during Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS). Neuroimage 2016, 140, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslacher, D.; Narang, A.; Sokoliuk, R.; Cavallo, A.; Reber, P.; Nasr, K.; Santarnecchi, E.; Soekadar, S.R. In Vivo Phase-Dependent Enhancement and Suppression of Human Brain Oscillations by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS). Neuroimage 2023, 275, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslacher, D.; Cavallo, A.; Reber, P.; Kattein, A.; Thiele, M.; Nasr, K.; Hashemi, K.; Sokoliuk, R.; Thut, G.; Soekadar, S.R. Working Memory Enhancement Using Real-Time Phase-Tuned Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2024, 17, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslacher, D.; Nasr, K.; Robinson, S.E.; Braun, C.; Soekadar, S.R. Stimulation Artifact Source Separation (SASS) for Assessing Electric Brain Oscillations during Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS). Neuroimage 2021, 228, 117571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, C.; Zaehle, T.; Haghikia, A.; Ruhnau, P. Amplitude Modulated Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (AM-TACS) Efficacy Evaluation via Phosphene Induction. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.R.; Vieira, P.G.; Thivierge, J.-P.; Pack, C.C. Brain Stimulation Competes with Ongoing Oscillations for Control of Spike Timing in the Primate Brain. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiene, M.; Schwab, B.C.; Misselhorn, J.; Herrmann, C.S.; Schneider, T.R.; Engel, A.K. Phase-Specific Manipulation of Rhythmic Brain Activity by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreglmann, S.R.; Wang, D.; Peach, R.L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Latorre, A.; Rhodes, E.; Panella, E.; Cassara, A.M.; Boyden, E.S.; et al. Non-Invasive Suppression of Essential Tremor via Phase-Locked Disruption of Its Temporal Coherence. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseichuk, I.; Falchier, A.Y.; Linn, G.; Xu, T.; Milham, M.P.; Schroeder, C.E.; Opitz, A. Electric Field Dynamics in the Brain during Multi-Electrode Transcranial Electric Stimulation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksenov, A.; Renaud-D’Ambra, M.; Volpert, V.; Beuter, A. Phase-Shifted tACS Can Modulate Cortical Alpha Waves in Human Subjects. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2024, 18, 1575–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Alamia, A.; Yao, Z.; Huang, G.; Li, L.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Z. State-Dependent tACS Effects Reveal the Potential Causal Role of Prestimulus Alpha Traveling Waves in Visual Contrast Detection. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e2023232024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnard, J.; Magnin, M.; Jung, J.; Mauguière, F.; Garcia-Larrea, L. Does the Insula Tell Our Brain That We Are in Pain? Pain 2011, 152, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBenedict, B.; Petrus, D.; Pires, M.P.; Pogodina, A.; Arrey Agbor, D.B.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Castro Ceron, J.I.; Balaji, A.; Abrahão, A.; Lima Pessôa, B. The Role of the Insula in Chronic Pain and Associated Structural Changes: An Integrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e58511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, F.; Zilles, K.; Fox, P.T.; Laird, A.R.; Eickhoff, S.B. A Link between the Systems: Functional Differentiation and Integration within the Human Insula Revealed by Meta-Analysis. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010, 214, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.C.W.; Tracey, I. The Insula: A Multidimensional Integration Site for Pain. Pain 2007, 128, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastuji, H.; Frot, M.; Perchet, C.; Hagiwara, K.; Garcia-Larrea, L. Convergence of Sensory and Limbic Noxious Input into the Anterior Insula and the Emergence of Pain from Nociception. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthier, M.; Starkstein, S.; Leiguarda, R. Asymbolia for Pain: A Sensory-Limbic Disconnection Syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 24, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, G.; Algoet, M.; Santos, S.F.; Ribeiro-Vaz, J.G.; Raftopoulos, C.; Mouraux, A. Tonic Thermonociceptive Stimulation Selectively Modulates Ongoing Neural Oscillations in the Human Posterior Insula: Evidence from Intracerebral EEG. Neuroimage 2019, 188, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Nan, G.; Bak, H.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, J.; Cha, M.; Lee, B.H. Insular Cortex Stimulation Alleviates Neuropathic Pain through Changes in the Expression of Collapsin Response Mediator Protein 2 Involved in Synaptic Plasticity. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 194, 106466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Moosa, S.; Quigg, M.; Elias, W.J. Anterior Insula Stimulation Increases Pain Threshold in Humans: A Pilot Study. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 135, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

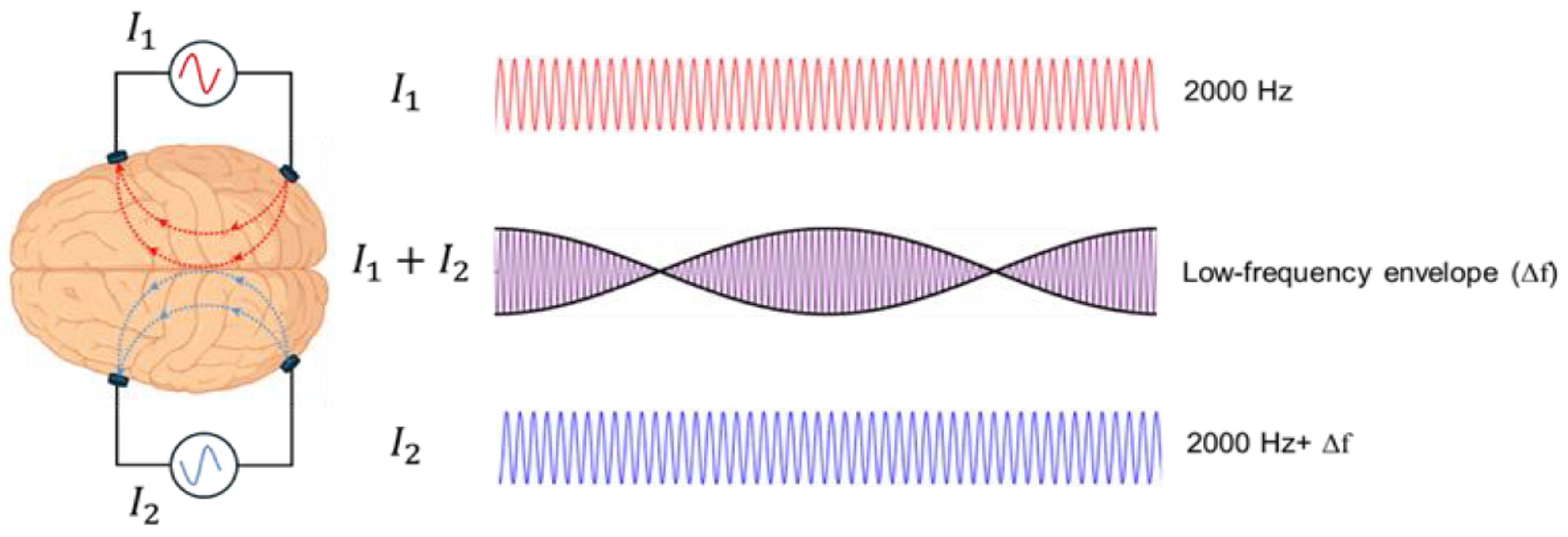

- Grossman, N.; Bono, D.; Dedic, N.; Kodandaramaiah, S.B.; Rudenko, A.; Suk, H.-J.; Cassara, A.M.; Neufeld, E.; Kuster, N.; Tsai, L.-H.; et al. Noninvasive Deep Brain Stimulation via Temporally Interfering Electric Fields. Cell 2017, 169, 1029–1041.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourinezhad, P.; Mestrom, R.M.C.; Klooster, D.C.W.; Sprengers, M.; Boon, P.A.J.M.; Paulides, M.M. Systematic Review of Experimental Studies in Humans on Transcranial Temporal Interference Stimulation. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, S.; Kakies, C.F.M.; Ciupercӑ, D.; Wischnewski, M. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation for Investigating Complex Oscillatory Dynamics and Interactions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2025, 212, 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseichuk, I.; Turi, Z.; Amador de Lara, G.; Antal, A.; Paulus, W. Spatial Working Memory in Humans Depends on Theta and High Gamma Synchronization in the Prefrontal Cortex. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Participant characteristics | Study design | Stimulation montage and site | tACS parameters | Control | Outcomes | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Pain tACS Studies | |||||||

| Arendsen et al., 2018 [27] | 23 healthy, right-handed (22 female; mean age = 21.4 ± 4.7) | Within-subject, randomized crossover study | Bilateral SM1 (CP3/CP4, 5×5 cm pads) | 10 Hz, 1 mA pp, ~15–20 min (applied during pressure pain task) | Sham (tRNS 30 s ramp-up/hold/down) | Pain intensity and unpleasantness ratings (NRS) during pressure pain to the middle finger. Participants also performed a visual cue-pain task, where cues predicted the timing of pain stimuli. | Decreased pain intensity and unpleasantness during active tACS vs. sham, only when impending pain intensity was uncertain; no correlations with fear of pain or catastrophizing. |

| Fathi et al., 2025 [26] | 38 healthy participants (19 female; mean age = 28 ± 8.5) | within-subject, randomized crossover, double-blind | Contralateral SM (4×1 montage centered on C3/C4) | Individual peak alpha frequency, 2mA pp, 20 min |

Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) | Heat pain thresholds and ratings + EEG | n.s.; trend toward reduced sensitization in women with active tACS; correlation was observed between SS-IAF and HPT during sham condition. |

| Ikarashi et al., 2024 [28] | 56 healthy, right-handed (27 female; mean age = 21.2 ± 1.0) | Between-subject, randomized, single-blind | Left DLPFC (F3–Fpz, 3×3 cm electrodes) | 6 Hz (θ) or 20 Hz (β), 1 mA, 20 min | Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) |

Heat pain threshold (HPT) and tolerance (HPTT) using Peltier thermode (right forearm, 35 °C baseline, +0.7 °C/s); repeated measures before, during, after stimulation; | Pain reduction vs sham; θ- and β-tACS ↑ HPT during and after stimulation , no effect on HPTT; θ-tACS pain reduction followed an inverted U-shaped relation with simulated E-field in posterior DLPFC, suggesting optimal field strength for maximal pain relief |

| Li et al., 2025 [29] | 80 healthy participants (41 female; mean age = 21.8 ± 2.12) | Between-subjects, double-blinded | Right SM (4x1 montage centered on C4 and the 4 surrounding return electrodes were placed at FC2, FC6, CP6, and CP2) |

10 Hz, 20 min, 1 mA | Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) | Ratings of pain intensity & unpleasantness in response to noxious laser stimulation, Visual cues manipulated certainty + EEG | n.s.: α-tACS produced no significant pain reduction effect on pain ratings. α-tACS disrupted normal LEP habituation, especially under certain pain expectation, with effects lasting ~30 min. It increased contralateral α₁ and midfrontal θ activity during anticipation; θ changes persisted. Mediation suggested opposing α-driven analgesic and θ-driven hyperalgesic pathways, with the latter dominating—resulting in no pain reduction. |

| May et al., 2021 [30] | 29 healthy, right-handed (13 female; mean age = 25.7 ± 4.0) | Within-subject, randomized crossover, double-blinded | PFC (F3/F4) or S1 (CP3/CP4), large pads 5×5 cm | 10 Hz (α) or 80 Hz (γ), 10 min, 1 mA pp | Sham (30 s 10 Hz with ramps) | Tonic heat pain (VAS, continuous ratings), autonomic measures (skin conductance, ECG), EEG (pre/post, 5 min) | n.s. for all conditions; no modulation of pain, autonomic responses, or oscillations. Bayesian analysis supported null, except α-S1 (inconclusive). |

| Peng et al., 2023 [31] | 53 healthy participants (26 active, 27 sham; 32 female; mean = age ~21) | Between-subject, double-blinded | Left or right SM1 (C3/C4-centered 4×1 HD montage) | 10 Hz, 20 min, 1 mA peak-to-peak | Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) |

fMRI during noxious laser stimulation (pain-evoked activity, connectivity), pain ratings (intensity, unpleasantness, NRS) | n.s.; Active α-tACS attenuated pain-evoked activity in bilateral SM1 and left M1 vs sham. Mediation: reduced SM1 activity indirectly decreased pain ratings. Functional connectivity between SM1 and DLPFC, S1, MCC, SMA decreased with active vs sham. |

| Qi et al., 2025 [32] | 31 healthy participants (14 female; mean age = 23 ± 2.3; final after artifact exclusion) | Within-subject, randomized crossover, double-blinded | Contralateral SM1 (4×1 HD montage centered on C4) | 10 Hz, 30 min, 1.5 mA pp | Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) | Capsaicin-induced pain (NRS), rest EEG power | Pain reduction vs sham. Resting α and pain-related θ changes at C4 predicted efficacy (α → θ → pain relief). |

| Sun et al., 2025 [33] | 45 healthy (28 female; mean age = 21 ± 2.4) | Within-subject, randomized crossover, single-blinded | ipsilateral DLPFC (F3-centered, 3×1 HD montage) | 10 Hz, 30 min, 1.5 mA pp | Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) | Capsaicin-induced pain (NRS), rest EEG power | Pain reduction vs sham; Delayed increase of low γ at DLPFC; weak correlation with pain reduction. |

| Takeuchi & Terui, 2025 [34] | 32 healthy participants, 16 pairs (18 females, 14 males; mean age = 21.0±1.4) | Within-subject, randomized crossover | Right S1 (2 cm posterior to C4, concentric 1X1 tACS) | 10 Hz, peak-to-peak 3 mA, 5 min | Sham (1 min with 30 sec ramp-up/down) | Electrical pain intensity ratings (NRS) and empathy scores from the IRI (Interpersonal Reactivity Index). Participant pairs alternated as pain-receiver and touch-giver while receiving mild electrical pain and gentle brush stroking on the forearm to examine the effects of tACS on touch-induced analgesia. |

Though overall pain ratings did not differ across conditions, synchronous dual-brain “hyper”-tACS enhanced social touch–induced pain reduction in low-empathy receivers vs. sham. |

| Chronic Pain tACS Studies | |||||||

| Ahn et al., 2019 [35] | 20 patients with chronic low back pain (8 male, 12 female; mean pain duration ≈ 85 months). | Within-subject, randomized crossover, double-blind, sham-controlled | Bifrontal (F3/F4, 5×5 cm; return 5×7 cm at Pz) | 10 Hz, 1 mA per F3/F4 (2 mA return at Pz), 40 min | Sham (1 min with ramp-up/down) | Chronic low back pain ratings (DVPRS, ODI), rest EEG (α-power pre/post, correlation with pain relief) | Pain reduction vs sham; 10 Hz -tACS increased somatosensory α-power, and α enhancement correlated with ↓ chronic pain ratings (DVPRS) and perceived disability (ODI); exploratory Wilcoxon test showed significant ↓ DVPRS , ODI change n.s. |

| Antal et al., (2020) [36] | 25 migraine patients (Active tACS: N = 16, age = 31.1±8.9; Sham: N = 9, age = 28.1±10.5) | Between-subject, randomized parallel groups, double-blinded | Occipital cortex (Oz, 4×4 cm) with return at Cz (5×7 cm) | 140 Hz, 0.4 mA, 15 min per session up to 5 sessions total over a six week period. Patients were instructed to use tACS during onset of migraine attacks. | Sham (simulator turned off after 30 sec) | patients recorded termination of migraine attacks within 2 hours post-stimulation (defined as NAS<1), NAS pain intensity (0-10) before/after migraine attacks, analgesic medication use, and attack recurrence. |

During migraines without use of analgesic medication, a significantly greater number of migraine attacks terminated following active tACS compared to sham. Significant ↓ NAS pain severity for active tACS compared to sham at 2-4 hours post-stimulation. |

| Bernardi et al., (2021) [37] | 15 individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia syndrome | Within-subject, randomized crossover,double blind 10 sessions (30 min/day, 5 days/week × 2 weeks) + physiotherapy (60 min/session) with 4-week washout between conditions |

Anode positioned individually over scalp region with greatest EEG abnormality (e.g., F3, C3, CP5, C4/Cp2, or similar); cathode over ipsilateral mastoid. large sponge pads (5 × 7 cm) |

1–2 mA alternating current Participants with increased slow rhythms (theta, delta, α₁) received β-tACS at 30 Hz Participants with increased fast rhythms (β, α₂) received θ-tACS at 4 Hz |

Random noise stimulation with random amplitude and frequency, respectively, in the intervals (1–2) mA and (0–100) Hz |

Resting EEG (α₁, θ, δ, β power); Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain; neuropsychological and self-report assessments (MoCA, TMT-A/B, HVLT-R, Rey Complex Figure, PROCOG-P, EMQ-R, BDI-II, BSI, STAI); SF-36 for health status. | Pain reduction vs sham; tailored tACS (4 Hz or 30 Hz, 1–2 mA) increased resting α₁ power and reduced pain (VAS ↓ at T1) vs random noise stimulation (RNS). Improved cognitive and neuropsychological performance (MoCA, TMT-B, PROCOG-P, EMQ-R) and reduced depressive symptoms (BDI-II, BSI). EEG normalization mainly over sensorimotor/M1 areas; pain relief effects faded by 4 weeks |

| Lin et al., 2022 [38] | 38 patients with fibromyalgia (30F; mean age 48.6 ± 12.9); 35 completed (active = 18, sham = 17) | Between-subject, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled | Left M1 (anode = C3; 4 cathodes = Cz, F3, T7, P3; radius ≈ 7.5 cm, 4×1 HD montage) | 50 Hz, 20 min/session, 10 sessions over 2 weeks | Sham (10 s ramp-up, 19 min 40 s no current, 10 s ramp-down) | NRS (pain intensity), FIQ (quality of life), BAI (anxiety), BDI-II (depression), PSQI (sleep quality), PPT (pressure pain threshold), plasma Tau and Aβ₁₋₄₂ | Both groups showed within-group symptom improvement; no significant differences between active and sham in NRS, FIQ, or secondary measures. Active HD-tACS significantly reduced FIQ vs baseline but not vs sham. One suicide attempt occurred (likely unrelated). HD-tACS was otherwise well tolerated. |

| Prim et al., 2019 [39] | 20 patients with chronic low back pain (8M, 12F; mean age 43 ± 13; mean pain duration ≈7 years) | Within-subject, randomized, crossover, double-blind, sham-controlled | Bilateral prefrontal cortex (F3/F4, 5×5 cm) with return at Pz (5×7 cm) | 10 Hz, 1 mA (zero-to-peak), 40 min; in-phase stimulation; ≥7 days washout | Sham (1 min 10 Hz with ramp-up/down) | ECG for HRV (RSA, LF, LF/HF, SDNN, RMSSD); pain (DVPRS), disability (ODI), and pressure pain threshold (PPT) pre/post | No significant change in RSA or LF/HF. SDNN increased after 10 Hz-tACS vs sham, indicating modulation of overall autonomic balance. Pain ratings and HRV changes were uncorrelated. Twice as many participants were clinical responders (≥2 pt pain reduction) in active vs sham, though not statistically significant. Blinding was successful and no adverse effects were reported. |

| * n.s. = no significant analgesic effect on pain ratings. | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).