Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

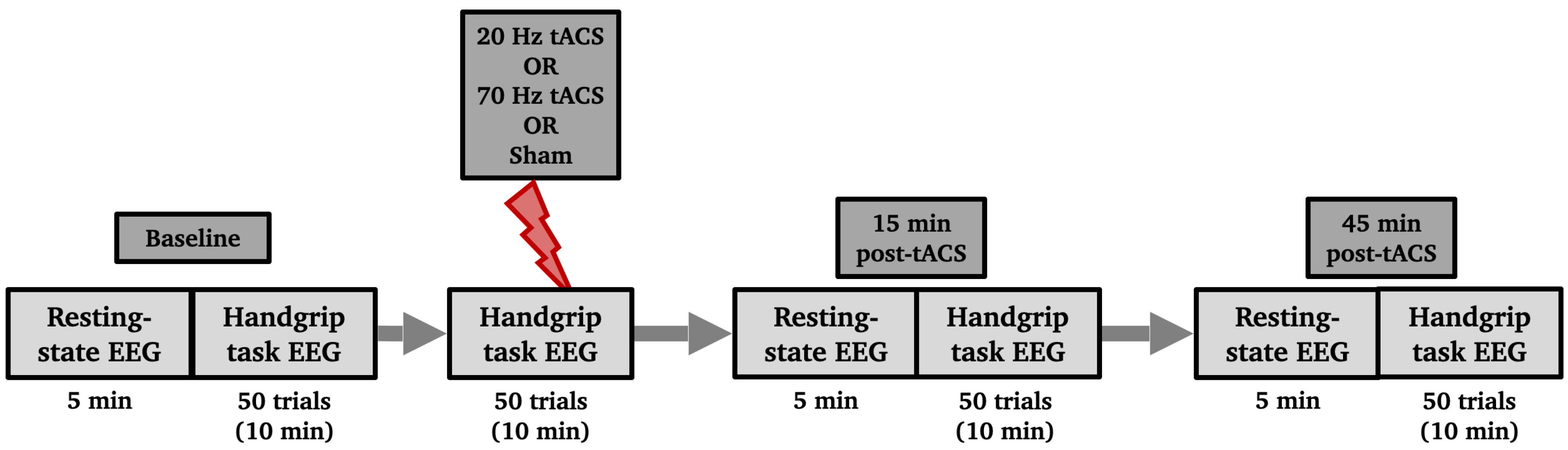

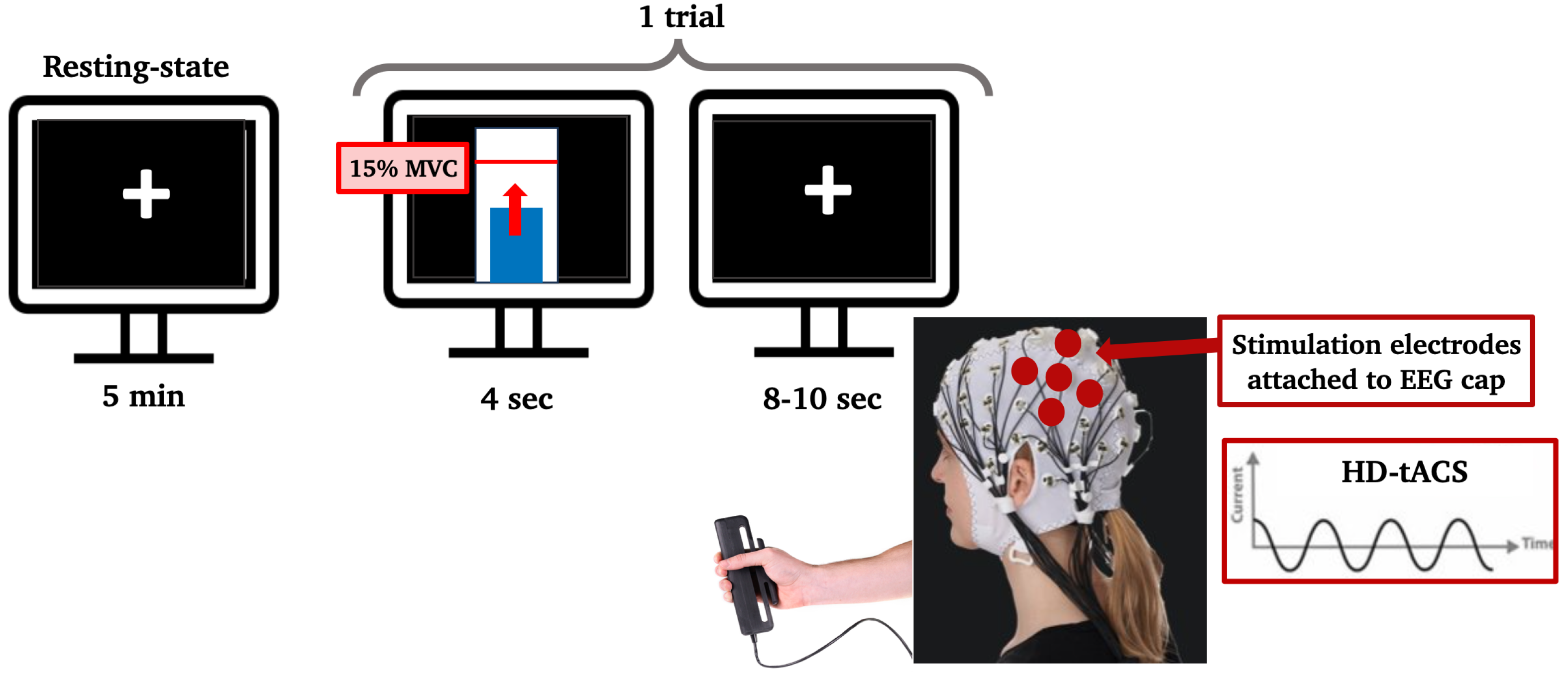

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Behavioural Scores

2.4.2. Resting-State EEG

2.4.3. Motor Task EEG

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Assessment

3.2. Participant Blinding

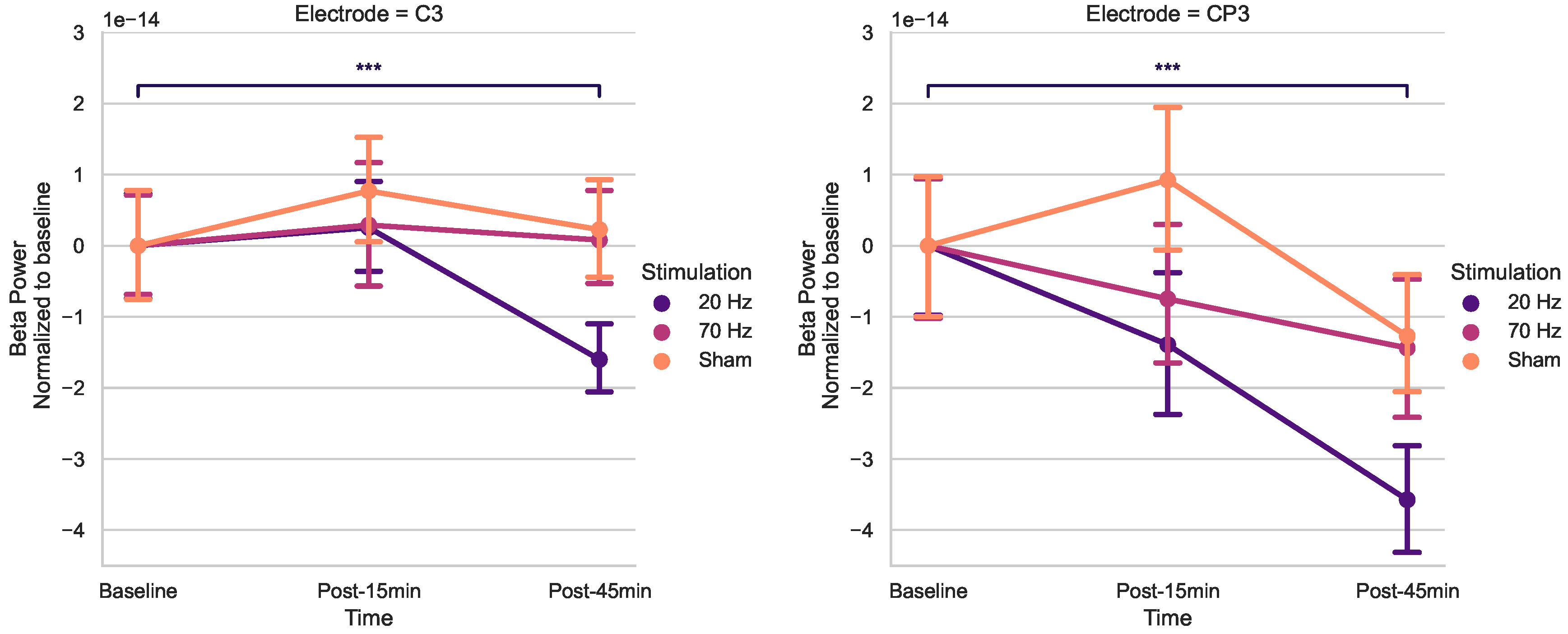

3.3. Effects of tACS on Resting-State Beta Power

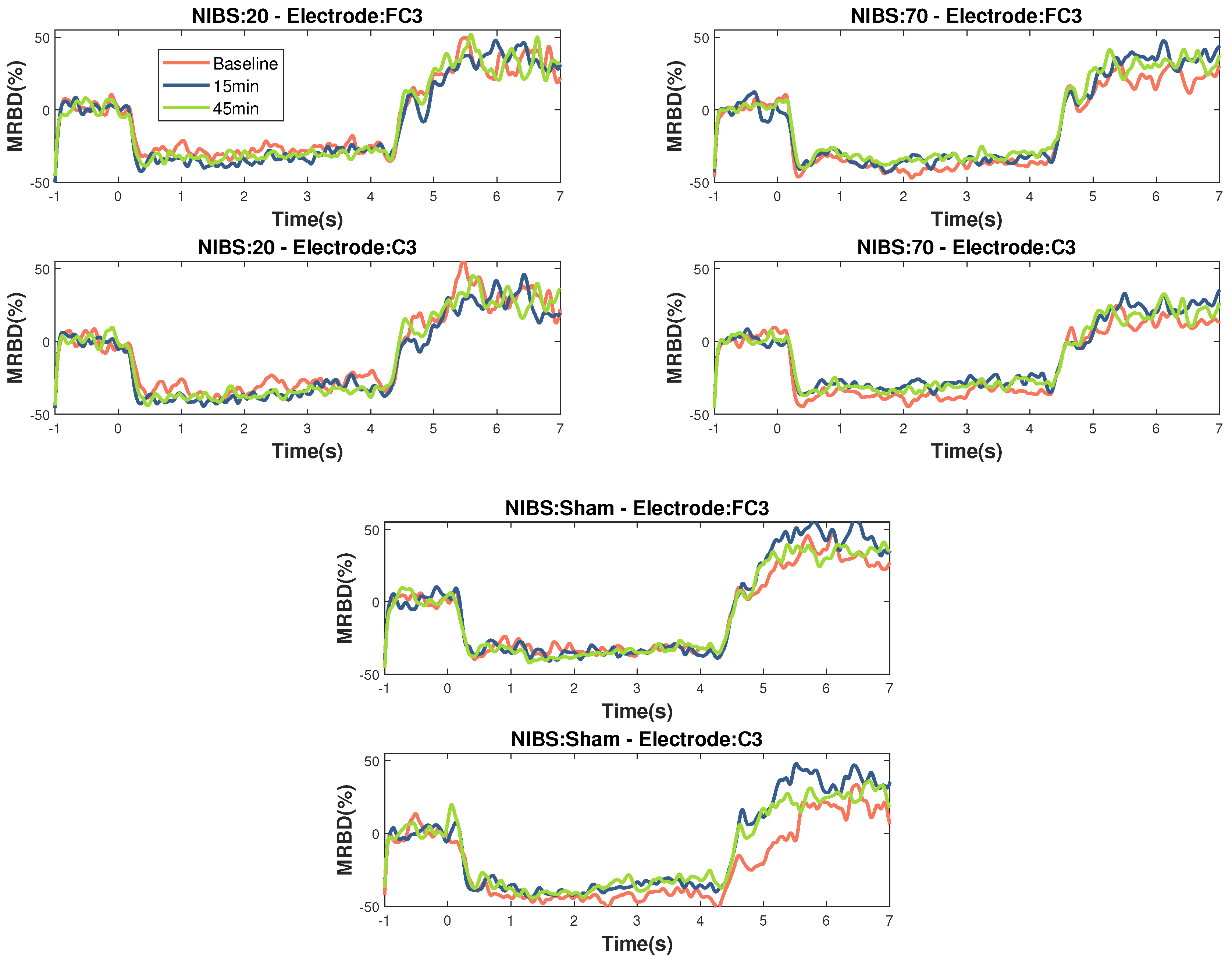

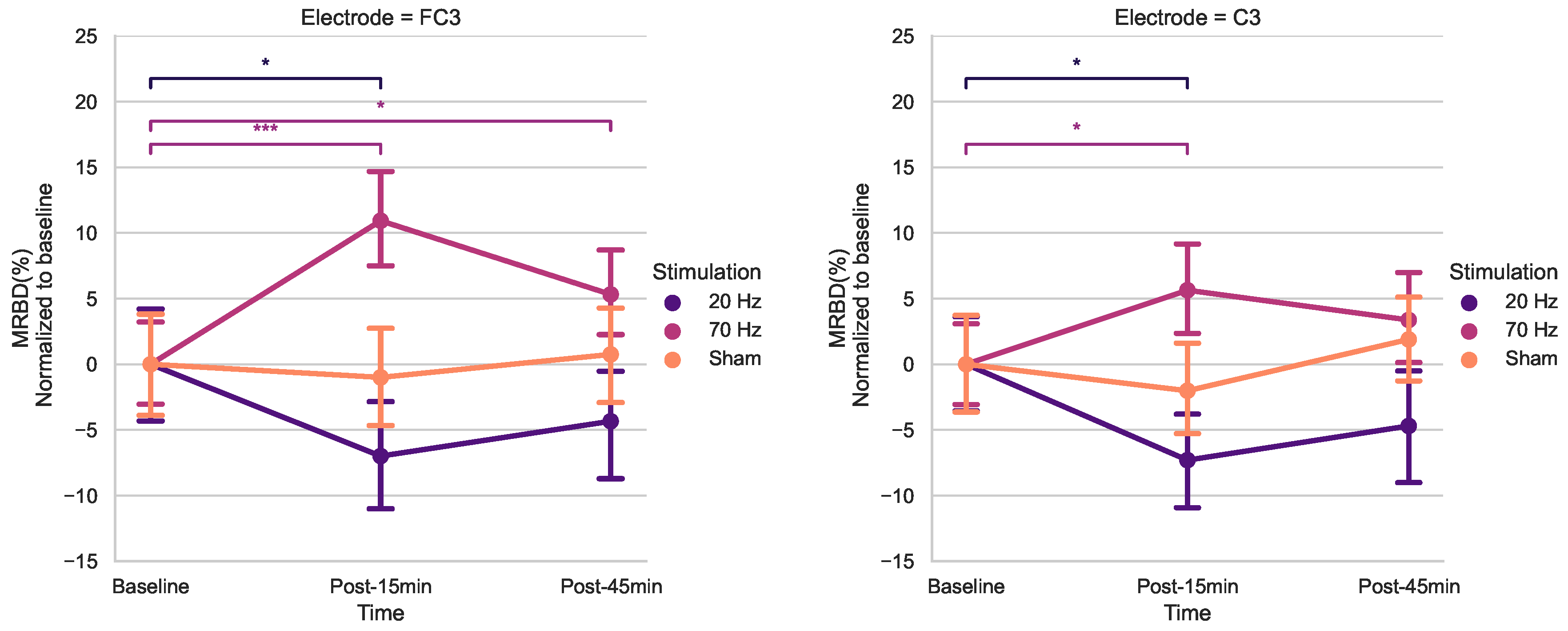

3.4. Effects of tACS on MRBD

4. Discussion

4.1. Population Behavioral Scores and Baseline Features

4.2. Modulation of Resting-State Beta Power

4.3. Modulation of MRBD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBT | Box and Block Test |

| CMC | Corticomuscular Coherence |

| ECR | Extensor Carpi Radialis |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| FDI | First Dorsal Interosseous |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric Acid |

| HD-tACS | High Definition Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation |

| HGS | Handgrip Strength Test |

| iAPF | Individual Alpha Peak Frequency |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| ISP | Intersectional Short Pulse |

| LTP | Long-term Potentiation |

| M1 | Primary Motor Cortex |

| MEG | Magnetoencephalography |

| MEP | Motor-Evoked Potential |

| MPS | Mild Parkinsonian Signs |

| MRBD | Movement-Related Beta Desynchronization |

| MVC | Maximum Voluntary Contraction |

| NREM | Non-rapid Eye Movement |

| NIBS | Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PPT | Purdue Pegboard Test |

| rmANOVA | Repeated-Measures Analysis of Variances |

| SICI | Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition |

| tACS | Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| TI | Temporally Interfering |

| TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

References

- Maes, C.; Gooijers, J.; Orban de Xivry, J.J.; Swinnen, S.P.; Boisgontier, M.P. Two hands, one brain, and aging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2017, 75, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, J.; Michan, S. Biology of Healthy Aging and Longevity. Revista de investigacion clinica, organo del Hospital de Enfermedades de la Nutricion 2016, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, E.D.; Tang, M.X.; Schupf, N.; Mayeux, R. Functional Correlates and Prevalence of Mild Parkinsonian Signs in a Community Population of Older People. Archives of Neurology 2005, 62, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, A.; Santelli, L.; Tomassini, V.; Bosnell, R.; Smith, S.; De Stefano, N.; Johansen-Berg, H. Age-related changes in grey and white matter structure throughout adulthood. NeuroImage 2010, 51, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.V.; Pfefferbaum, A. Neuroradiological characterization of normal adult ageing. British Journal of Radiology 2014, 80, S99–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubert, M.; Roggenhofer, E.; Melie-Garcia, L.; Muller, S.; Lehmann, N.; Preisig, M.; Vollenweider, P.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Lutti, A.; Kherif, F.; Draganski, B. Converging patterns of aging-associated brain volume loss and tissue microstructure differences. Neurobiology of Aging 2020, 88, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, C.D.; Johnsrude, I.S.; Ashburner, J.; Henson, R.N.; Friston, K.J.; Frackowiak, R.S. A Voxel-Based Morphometric Study of Ageing in 465 Normal Adult Human Brains. NeuroImage 2001, 14, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartzokis, G. Age-related myelin breakdown: a developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging 2004, 25, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, R.D.; Bernard, J.A.; Burutolu, T.B.; Fling, B.W.; Gordon, M.T.; Gwin, J.T.; Kwak, Y.; Lipps, D.B. Motor control and aging: Links to age-related brain structural, functional, and biochemical effects. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2010, 34, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilavik, B.E.; Ponce-Alvarez, A.; Trachel, R.; Confais, J.; Takerkart, S.; Riehle, A. Context-Related Frequency Modulations of Macaque Motor Cortical LFP Beta Oscillations. Cerebral Cortex 2011, 22, 2148–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheyne, D.; Ferrari, P. MEG studies of motor cortex gamma oscillations: evidence for a gamma "fingerprint" in the brain? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilavik, B.E.; Zaepffel, M.; Brovelli, A.; MacKay, W.A.; Riehle, A. The ups and downs of beta oscillations in sensorimotor cortex. Experimental Neurology 2013, 245, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xifra-Porxas, A.; Niso, G.; Larivière, S.; Kassinopoulos, M.; Baillet, S.; Mitsis, G.D.; Boudrias, M.H. Older adults exhibit a more pronounced modulation of beta oscillations when performing sustained and dynamic handgrips. NeuroImage 2019, 201, 116037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs-Graham, E.; Wilson, T.W. Is an absolute level of cortical beta suppression required for proper movement? Magnetoencephalographic evidence from healthy aging. NeuroImage 2016, 134, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardouille, T.; Bailey, L. Evidence for age-related changes in sensorimotor neuromagnetic responses during cued button pressing in a large open-access dataset. NeuroImage 2019, 193, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs-Graham, E.; McDermott, T.J.; Mills, M.S.; Wiesman, A.I.; Wang, Y.P.; Stephen, J.M.; Calhoun, V.D.; Wilson, T.W. The lifespan trajectory of neural oscillatory activity in the motor system. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 2018, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, H.E.; Davis, E.M.; Clark, E.V.; Boudrias, M.H.; Ward, N.S. Beta oscillations reflect changes in motor cortex inhibition in healthy ageing. NeuroImage 2014, 91, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reato, D.; Rahman, A.; Bikson, M.; Parra, L.C. Effects of weak transcranial alternating current stimulation on brain activity—a review of known mechanisms from animal studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, A.; Paulus, W. Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.S.; Rach, S.; Neuling, T.; Strüber, D. Transcranial alternating current stimulation: a review of the underlying mechanisms and modulation of cognitive processes. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogosyan, A.; Gaynor, L.D.; Eusebio, A.; Brown, P. Boosting Cortical Activity at Beta-Band Frequencies Slows Movement in Humans. Current Biology 2009, 19, 1637–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakatos, P.; Gross, J.; Thut, G. A New Unifying Account of the Roles of Neuronal Entrainment. Current Biology 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antal, A.; Herrmann, C.S. Transcranial Alternating Current and Random Noise Stimulation: Possible Mechanisms. Neural Plasticity 2016, 2016, 3616807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugata, H.; Yagi, K.; Yazawa, S.; Nagase, Y.; Tsuruta, K.; Ikeda, T.; Matsushita, K.; Hara, M.; Kawakami, K.; Kawakami, K. Modulation of Motor Learning Capacity by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Neuroscience 2018, 391, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P. Abnormal oscillatory synchronisation in the motor system leads to impaired movement. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2007, 17, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, A.K.; Fries, P. Beta-band oscillations—signalling the status quo? Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2010, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, N.; Pogosyan, A.; Sharott, A.; Csicsvari, J.; Bolam, J.P.; Brown, P.; Magill, P.J. Disrupted Dopamine Transmission and the Emergence of Exaggerated Beta Oscillations in Subthalamic Nucleus and Cerebral Cortex. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 4795–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.; Antal, A.; Bikson, M.; Boggio, P.; Brunoni, A.; Celnik, P.; Cohen, L.; Fregni, F.; Herrmann, C.; Kappenman, E.; Knotkova, H.; Liebetanz, D.; Miniussi, C.; Miranda, P.; Paulus, W.; Priori, A.; Reato, D.; Stagg, C.; Wenderoth, N.; Nitsche, M. A technical guide to tDCS, and related non-invasive brain stimulation tools. Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 127, 1031–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, C.; Kamholz, J.; Rudroff, T. The Tolerability and Efficacy of 4 mA Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Leg Muscle Fatigability. Brain Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrichsen, J.; Kornysheva, K. Motor skill learning between selection and execution. Trends in cognitive sciences 2015, 19, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, J.W.; Hadjiosif, A.M.; Xu, J.; Wong, A.L.; Haith, A.M. , Motor Learning. In Comprehensive Physiology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2019; pp. 613–663. [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.N.; Donoghue, J.P. Plasticity and Primary Motor Cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2000, 23, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarrow, K.; Brown, P.; Krakauer, J. Inside the brain of an elite athlete: the neural processes that support high achievement in sports. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 2009, 10, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriraman, A.; Oishi, T.; Madhavan, S. Timing-dependent priming effects of tDCS on ankle motor skill learning. Brain Research 2014, 1581, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perceval, G.; Flöel, A.; Meinzer, M. Can transcranial direct current stimulation counteract age-associated functional impairment? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2016, 65, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, K.F.; Kortzorg, N.; Saturnino, G.B.; Fujiyama, H.; Cuypers, K.; Thielscher, A.; Swinnen, S.P. Evaluation of a Modified High-Definition Electrode Montage for Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) of Pre-Central Areas. Brain Stimulation 2016, 9, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Z.H.; Maniscalco, B.; Hallett, M.; Wassermann, E.M.; He, B.J. Modulating Conscious Movement Intention by Noninvasive Brain Stimulation and the Underlying Neural Mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience 2015, 35, 7239–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, K.F.; Monteiro, T.S.; Inge, L.; Dante, M.; Swinnen, S.P. Distinct online and offline effects of alpha and beta transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on continuous bimanual performance and task-set switching. Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozdniakov, I.; Nunez, V.A.; Giulia, G.; Rossi, S.; Matteo, F. Online and offline effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation of the primary motor cortex. Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veniero, D.; Vossen, A.; Gross, J.; Thut, G. Lasting EEG/MEG Aftereffects of Rhythmic Transcranial Brain Stimulation: Level of Control Over Oscillatory Network Activity. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, R.F.; Schneider, T.R.; Rach, S.; Trautmann-Lengsfeld, S.A.; Engel, A.K.; Herrmann, C.S. Entrainment of Brain Oscillations by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Current Biology 2014, 24, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuling, T.; Rach, S.; Herrmann, C.S. Orchestrating neuronal networks: sustained after-effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation depend upon brain states. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. The Journal of Physiology 2000, 527, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology: Journal of the American Heart Association 2001, 57, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Elderly population 2014. [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, R. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borson, S.; Scanlan, J.; Brush, M.; Vitaliano, P.; Dokmak, A. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2000, 15, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Volland, G.; Kashman, N.; Weber, K. Adult Norms for the Box and Block Test of Manual Dexterity. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1985, 39, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom-Hazel, D.; VanderVlies Veenstra, N. Examining the Purdue Pegboard Test for Occupational Therapy Practice. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Peolsson, A.; Massy-Westropp, N.; Desrosiers, J.; Bear-Lehman, J. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a Jamar dynamometer: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2006, 92, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Ugawa, Y. Adverse events of tDCS and tACS: A review. Clinical Neurophysiology Practice 2017, 2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadel, F.; Baillet, S.; Mosher, J.C.; Pantazis, D.; Leahy, R.M. Brainstorm: A User-Friendly Application for MEG/EEG Analysis. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2011, 2011, 879716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Desrosiers, R. Hébert, G.B.; Dutil, E. The Purdue Pegboard Test: Normative data for people aged 60 and over. Disability and Rehabilitation 1995, 17, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon-Baudry, C.; Bertrand, O.; Delpuech, C.; Pernier, J. Stimulus Specificity of Phase-Locked and Non-Phase-Locked 40 Hz Visual Responses in Human. Journal of Neuroscience 1996, 16, 4240–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Maso, F.; Desormeau, B.; Boudrias, M.H.; Roig, M. Acute cardiovascular exercise promotes functional changes in cortico-motor networks during the early stages of motor memory consolidation. NeuroImage 2018, 174, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf, J.J.; Barbu, A.; Fricke, C.; Wegscheider, M.; Classen, J. Posttraining Alpha Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation Impairs Motor Consolidation in Elderly People. Neural Plasticity 2019, 2019, 2689790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasten, F.H.; Dowsett, J.; Herrmann, C.S. Sustained Aftereffect of gamma-tACS Lasts Up to 70 min after Stimulation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischnewski, M.; Engelhardt, M.; Salehinejad, M.A.; Schutter, D.J.L.G.; Kuo, M.F.; Nitsche, M.A. NMDA Receptor-Mediated Motor Cortex Plasticity After 20 Hz Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Cerebral Cortex 2018, 29, 2924–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaehle, T.; Rach, S.; Herrmann, C.S. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation Enhances Individual Alpha Activity in Human EEG. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischnewski, M.; Schutter, D.J.; Nitsche, M.A. Effects of beta-tACS on corticospinal excitability: A meta-analysis. Brain Stimulation 2019, 12, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazono, H.; Ogata, K.; Takeda, A.; Yamada, E.; Kimura, T.; Tobimatsu, S. Transcranial alternating current stimulation of gamma but not beta frequency sharpens multiple visual functions. Brain Stimulation 2020, 13, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, L.; Ghiani, A.; Casco, C.; Ronconi, L. Parietal tACS at beta frequency improves vision in a crowding regime. NeuroImage 2020, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis-Philippe, L.; Murray, A.; Manon, D.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Felipe, F.; Tremblay, S.; Saint-Amour, D.; Jean-François, L.; Hugo, T. No aftereffects of high current density 10 Hz and 20 Hz tACS on sensorimotor alpha and beta oscillations. Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresnoza, S.; Christova, M.; Feil, T. The effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) at individual alpha peak frequency (iAPF) on motor cortex excitability in young and elderly adults. Experimental Brain Research 2018, 236, 2573–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Niu, M.; Hanson, N.J.; Guo, J.; Zhou, K.; Zhao, T.; Ren, Y. Enhancing motor skill learning through multiple sessions of online high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation in healthy adults: insights from EEG power spectrum. Cerebral Cortex 2024, 34, bhae395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, A.; Elwassif, M.; Battaglia, F.; Bikson, M. Transcranial current stimulation focality using disc and ring electrode configurations: FEM analysis. Journal of Neural Engineering 2008, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D.; Cortes, M.; Datta, A.; Minhas, P.; Wassermann, E.M.; Bikson, M. Physiological and modeling evidence for focal transcranial electrical brain stimulation in humans: A basis for high-definition tDCS. NeuroImage 2013, 74, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, M.; Lee, A.; Frazer, A.K.; Akalu, Y.; Siddique, U.; Pearce, A.J.; Tallent, J.; Kidgell, D.J. Determining the corticospinal, intracortical and motor function responses to transcranial alternating current stimulation of the motor cortex in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Research 2024, 1822, 148650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastakouri, A.A.; Schölkopf, B.; Grosse-Wentrup, M. Beta Power May Meditate the Effect of Gamma-TACS on Motor Performance. 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2019, pp. 5902–5908. [CrossRef]

- Schilberg, L.; Engelen, T.; ten Oever, S.; Schuhmann, T.; de Gelder, B.; de Graaf, T.A.; Sack, A.T. Phase of beta-frequency tACS over primary motor cortex modulates corticospinal excitability. Cortex 2018, 103, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, S.E.W.; Sack, A.T.; Ten Oever, S.; de Graaf, T.A. Calibrating rhythmic stimulation parameters to individual electroencephalography markers: The consistency of individual alpha frequency in practical lab settings. European Journal of Neuroscience 2022, 55, 3418–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmerer, S.; Sack, A.; de Graaf, T.; ten Oever, S.; De Weerd, P.; Schuhmann, T. Frequency-specific transcranial neuromodulation of alpha power alters visuospatial attention performance. Brain Research 2022, 1782, 147834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanampudi, V.; Kumar, V.; Krishnan, A.; Walker, M.P.; Ivry, R.B.; Knight, R.T.; Gurumoorthy, R. Personalized transcranial alternating current stimulation improves sleep quality: Initial findings. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, A.; Asci, F.; Zampogna, A.; D’Onofrio, V.; Berardelli, A.; Suppa, A. The effect of gamma oscillations in boosting primary motor cortex plasticity is greater in young than older adults. Clinical Neurophysiology 2021, 132, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, V.; Wach, C.; Suedmeyer, M.; Ferrea, S.; Schnitzler, A.; Pollok, B. Cortico-muscular coupling and motor performance are modulated by 20 Hz transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Peng, M.; Lu, J.; Xiao, C.; Zong, X.; Wang, M.; Gao, D.; Qin, Y.; Liu, T. Enhancement of Event-Related Desyn- chronization in Motor Imagery Based on Transcranial Electrical Stimulation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.M.; Uehara, K.; Hanakawa, T. The contribution of interindividual factors to variability of response in transcranial direct current stimulation studies. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Zoghi, M.; Jaberzadeh, S. Biological and anatomical factors influencing interindividual variability to noninvasive brain stimulation of the primary motor cortex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2018, 29, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Svane, C.; Forman, C.; Beck, M.; Geertsen, S.; Lundbye-Jensen, J.; JB, N. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation of the Primary Motor Cortex after Skill Acquisition Improves Motor Memory Retention in Humans: A Double-Blinded Sham-Controlled Study. Cerebral cortex communications 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Cao, T.; Li, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Cai, C.; Fan, L.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, J. Long-term gamma transcranial alternating current stimulation improves the memory function of mice with Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Boudrias, M.H.; Mitsis, G.D. Removal of Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation EEG Artifacts Using Blind Source Separation and Wavelets. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2022, 69, 3183–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | Min - Mix | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| Handedness (/100) | ||

| MiniCog (points) | ||

| BBT Right Hand (blocks) | ||

| BBT Left Hand (blocks) | ||

| PPT Right Hand (pins) | ||

| PPT Left Hand (pins) | ||

| PPT Both Hands (pins) | ||

| PPT Assembly (pins) | ||

| HGS Right Hand (kg) | ||

| HGS Left Hand (kg) |

| PPT subtests | Predicted | Real | p-value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Hand | 0.136 | 0.326 | ||

| Left Hand | 0.439 | 0.048 | ||

| Both Hands | 0.128 | 0.358 | ||

| Assembly | 0.493 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).