Introduction

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) represents a significant public health challenge in Kenya, where the rising prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus has led to an increasing number of patients requiring renal replacement therapy[1–4]. Hemodialysis is the primary life-sustaining treatment for most ESRD patients in the country. Despite its crucial role, outcomes remain concerning, with mortality rates significantly higher than those reported in high-income countries[5,6].

Globally, vascular access type is a well-established key determinant of mortality in hemodialysis populations [7]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that CVC use is consistently associated with significantly higher all-cause and infection-related mortality compared with arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) [8]. While this association is clear in high-income settings, comprehensive data on clinical outcomes and survival determinants from routine care settings in sub-Saharan Africa remain scarce. A systematic review on mortality prediction in CKD highlighted that most evidence comes from non-African cohorts, underscoring the need for region-specific data[9].

In Kenya's decentralised healthcare system, county-level hospitals, such as Murang'a County Referral Hospital, form the backbone of ESRD care. The management of ESRD in resource-limited settings faces multiple challenges, including late presentation, limited dialysis capacity, high treatment costs, and a significant comorbidity burden [10]. A critical and often-cited barrier is the underutilization of AVF, the gold standard for vascular access, with studies from national referral hospitals in Kenya reporting a predominance of central venous catheters (CVCs) at dialysis initiation [11,12]. This pattern of late presentation and emergent catheter use is replicated across the region, as seen in Tanzania [13].

Understanding local predictors of poor outcomes is essential for developing targeted interventions and optimising resource allocation to improve patient survival. This study aimed to evaluate one-year clinical outcomes and identify independent predictors of mortality in a cohort of hemodialysis patients at Murang'a County Referral Hospital, providing crucial evidence to inform practice in similar resource-limited settings. Furthermore, we sought to quantify the burden of catheter-dependent dialysis in a typical county-level facility.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Measurements

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all adult patients (≥18 years) with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who initiated maintenance hemodialysis at Murang’a County Referral Hospital between January 2024 and January 2025. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at one year from dialysis initiation. Key exposure variables included demographic characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory values, and vascular access type (arteriovenous fistula vs. central venous catheter).

Data Sources, Recruitment and Collection

Patients were identified through the hospital's electronic health record system and dialysis unit records. The initial data extraction identified 132 patients who had visited the Renal Dialysis Unit during the study period. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, we excluded 24 duplicate entries, 19 patients who did not meet ESRD diagnostic criteria (defined as eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73m² requiring renal replacement therapy), and 10 patients with insufficient clinical documentation (missing >50% of key variables). The final analytical cohort comprised 79 patients with confirmed ESRD and complete treatment records.

Data were extracted by two trained physicians (F.P.O. and T.K.K.) using a standardised, pre-piloted electronic data collection form. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. The collected variables included: (1) Demographic characteristics: age and sex; (2) Clinical characteristics: primary cause of ESRD and comorbid conditions; (3) Baseline laboratory values: hemoglobin and eGFR; and (4) Treatment parameters: vascular access type and number of hemodialysis sessions completed. Key variables required for inclusion were age, sex, confirmed ESRD diagnosis, vascular access type, and vital status at one year. Patients missing more than 50% of these defined key variables were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1. Continuous and categorical variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and counts with percentages, respectively. Between-group comparisons used Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Survival analysis was conducted using Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to identify factors associated with one-year mortality. Variables with p<0.10 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. However, due to the limited number of mortality events (n=27), the multivariate model may be overfit, and the results should be interpreted as exploratory. The model was checked for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and all VIFs were below 2.0. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by Murang’a County Referral Hospital Ethics Committee. Informed consent was waived for this retrospective analysis of de-identified data. Patient confidentiality was maintained through data anonymization, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and followed STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for reporting.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The final cohort of 79 patients had a median age of 62.0 years (IQR 48.0-74.0) with male predominance (52/79, 65.8%). Hypertension was the leading cause of ESRD (38/79, 48.1%), followed by diabetes mellitus (25/79, 31.6%) and chronic glomerulonephritis (16/79, 20.3%). These were the three exclusive, pre-defined etiological categories for the analysis. Comorbidity analysis revealed a high prevalence of hypertension (68/79, 86.1%), diabetes mellitus (32/79, 40.5%), and HIV (14/79, 17.7%). Other less common conditions were documented but excluded from subsequent multivariate analysis due to low prevalence.

Most patients (71/79, 89.9%) relied on central venous catheters (CVCs) for vascular access, while only 8 (10.1%) had arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). The median baseline haemoglobin was 8.2 g/dL (IQR 7.1-9.3), indicating significant anaemia, and the median eGFR at dialysis initiation was 7.8 mL/min/1.73m² (IQR 5.4-10.2), suggesting late presentation.

Comparative analysis between survivors and non-survivors revealed significant differences. Non-survivors were significantly older than survivors (median 73.0 vs 58.0 years, p<0.001) and had lower baseline haemoglobin (7.1 vs 8.6 g/dL, p=0.008). Notably, all 27 patients who died (100%) were dialyzed using a CVC, whereas 15.4% (8/52) of survivors had an AVF (p=0.018). The baseline eGFR was also significantly lower in non-survivors (6.2 vs 8.1 mL/min/1.73m², p=0.023). No significant differences were found in sex distribution or the prevalence of individual comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, or HIV between the two groups (

Table 1).

Clinical Outcomes and Mortality

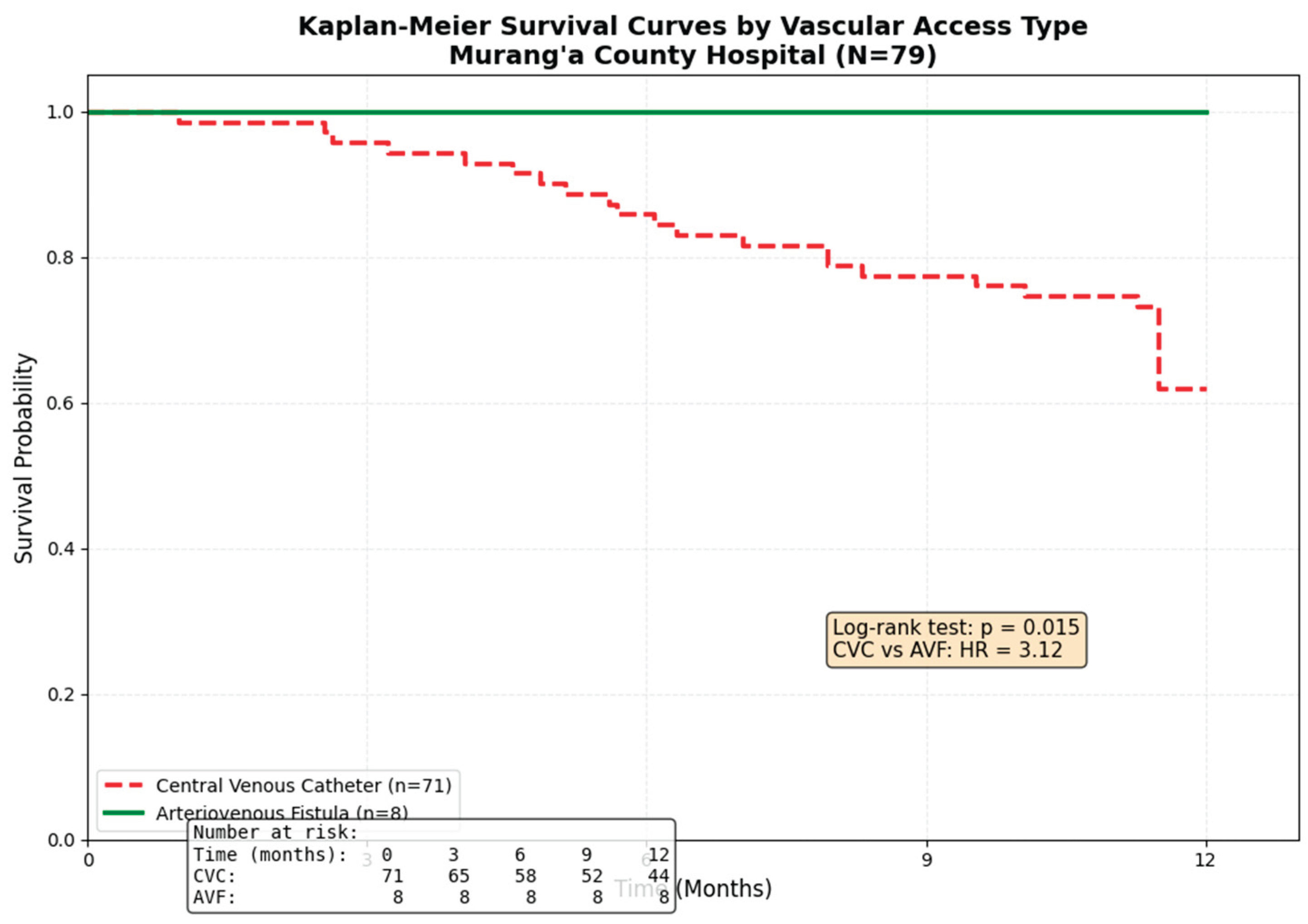

Over the one-year follow-up period, 27 patients died, yielding an all-cause mortality rate of 34.2% (27/79). As expected due to early mortality, the median number of hemodialysis sessions completed was significantly lower in non-survivors compared to survivors (51.0 [IQR 22.0-89.0] vs 124.0 [IQR 78.0-198.0], p<0.001). Documented complications occurred in 31 patients (39.2%), with infection (18/79, 22.8%) and hypotension (13/79, 16.5%) being most prevalent. Treatment discontinuation occurred in 11 patients (13.9%), primarily due to loss to follow-up (8/79, 10.1%). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve (

Figure 1) demonstrates a significant difference in survival probability by vascular access type (Log-rank test, p=0.015), with AVF patients exhibiting 100% survival at 1 year.

Predictors of One-Year Mortality

In univariate Cox regression analysis, older age (HR 1.07 per year, 95% CI 1.03-1.11, p<0.001), lower hemoglobin (HR 0.74 per g/dL, 95% CI 0.59-0.93, p=0.009), lower eGFR (HR 0.87 per mL/min/1.73m², 95% CI 0.78-0.97, p=0.015), and central venous catheter use (HR 4.45, 95% CI 1.25-15.82, p=0.021) were significantly associated with higher mortality. HIV status showed a trend towards increased risk but was not statistically significant (HR 1.48, 95% CI 0.65-3.35, p=0.350).

For the multivariate model, we included age, hemoglobin,

eGFR, CVC use, and HIV status. After adjustment, older age (aHR 1.05 per year, 95% CI 1.01-1.09, p=0.012) and central venous catheter use (aHR 3.12, 95% CI 1.08-9.01, p=0.036) remained independent predictors of one-year mortality. The hazard ratio for CVC use should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of AVF patients (n=8) and the statistical phenomenon of "perfect prediction" (0 deaths in the AVF group), which can lead to inflated estimates. The association between lower hemoglobin (aHR 0.84, 95% CI 0.66-1.07, p=0.156) and lower eGFR (aHR 0.92, 95% CI 0.82-1.03, p=0.162) with mortality was attenuated and lost statistical significance in the adjusted model. HIV status was not an independent predictor in the multivariate analysis (aHR 1.32, 95% CI 0.57-3.05, p=0.519) (

Table 2).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study from a routine-care Kenyan county hospital reveals two critical findings: a high one-year all-cause mortality rate of 34.2% among incident hemodialysis patients, and the identification of advanced age and catheter-dependent vascular access as significant, independent predictors of this mortality. The near-universal reliance on CVCs (89.9%), which stands in stark contrast to international clinical practice guidelines, emerges as the most salient and modifiable risk factor in our setting.

The observed mortality rate is consistent with the disparities in ESRD outcomes between resource-limited and high-income countries [2,14]. For instance, while one-year survival rates often exceed 85% in registries from North America [6], our data align more closely with reports from other sub-Saharan African contexts, where systemic challenges such as late presentation, high cost of treatment, and limited supportive care contribute to poorer survival [15–17]. The advanced age of our non-survivors (median 73 years) reaffirms a well-established global trend, where older patients on dialysis experience higher mortality due to a greater burden of frailty and comorbidities[18]. Frailty is highly prevalent in this population and is a strong, independent predictor of mortality, hospitalizations, and other adverse outcomes [19,20]. The trajectory of frailty is also concerning, as worsening frailty in the initial months after starting dialysis further predicts increased mortality risk.

The most compelling finding of our study is the strong independent association between CVC use and mortality (aHR 3.12). This aligns with a large cohort study from Mexico, which found a 2.8 to 5.0-fold increased mortality risk for tunneled and non-tunnelled CVCs, respectively, compared to AVFs[7]. This pattern of significantly elevated risk associated with catheters is consistently observed across diverse geographic and healthcare settings, from underserved populations in Latin America to elderly cohorts in Europe [20,21]. Our findings are also consistent with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of over 300,000 elderly patients, which concluded that initiating dialysis with a CVC was associated with a 53% higher risk of death compared to arteriovenous access. This pattern of significantly elevated risk is consistently observed across diverse healthcare settings, from national registries in Europe to cohort studies in North America and Mexico[8].

The 90% prevalence of CVC use indicates a systemic failure in the predialysis care pathway. This finding resonates with recent audits from Kenyan national referral hospitals, which also report a predominance of catheter use at dialysis initiation, often exceeding 80% [11,12]. This pattern is not isolated but reflects a regional challenge, as seen in neighboring Tanzania, where CVC initiation is nearly universal [13]. This 'catheter-first' reality constitutes a critical public health issue that is both clinically detrimental and economically inefficient for healthcare systems.

Our study demonstrates that this national challenge directly translates into excess mortality at the county level. The 100% one-year survival of the small subset of patients with an AVF (n=8), while based on a limited number and requiring cautious interpretation, underscores the potential survival benefit of overcoming these systemic barriers. The primary drivers are likely multifactorial, including delayed nephrology referral [16], limited surgical capacity for AVF creation [17], and financial constraints that prevent timely access to elective surgical procedures [18]. Furthermore, we acknowledge the potential for confounding by indication, as CVC use is often a marker for the "sicker," late-presenting patient who requires urgent dialysis initiation. While we adjusted for age and eGFR, residual confounding by unmeasured factors such as frailty [19], nutritional status, or socioeconomic status [20] may persist [21. .

Interestingly, while severe anaemia was prevalent and associated with mortality in univariate analysis, it was not an independent predictor after multivariate adjustment. This suggests that, in our cohort, anaemia may act as a surrogate marker of overall illness severity, malnutrition, or inflammation rather than a direct causal factor [22,23]. Its significance is likely overshadowed by the potent risk profile imposed by CVC use and advanced age.

Study Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective, single-center design and modest sample size (n=79) inherently limit statistical power and increase the risk of type II error, particularly for analyzing less prevalent comorbidities. The small number of events also increases the risk of overfitting in our multivariate model, and the hazard ratio for CVC is likely unstable due to the very small AVF comparator group. The wide confidence intervals for key predictors reflect this limitation. Second, we lacked data on socioeconomic status, nutritional markers (e.g., albumin), and dialysis adequacy (Kt/V), all of which are important prognostic factors. Third, the strong association between CVC use and mortality may be subject to significant residual confounding by indication. Finally, the exclusive use of CVC in the non-survivor group creates a statistical limitation (perfect separation) that affects the precision of the hazard ratio estimate.

Conclusion

This study confirms a high one-year mortality rate among hemodialysis patients in a Kenyan county hospital. Advanced age and catheter-dependent vascular access are significant independent predictors of death. The near-total reliance on CVCs is a potent surrogate marker for a broken pre-dialysis care pathway and represents a modifiable risk factor that demands urgent, system-level intervention. Focusing resources on establishing functional vascular access programs and improving early nephrology referral is likely the most effective strategy to improve survival in this vulnerable population.

Recommendations

We recommend that county and national health departments prioritise the development of comprehensive vascular access programs. This should include training for vascular surgery, streamlined patient referral pathways, and the allocation of specific resources for AVF creation. Future prospective, multi-centre studies are needed to validate these findings and to explore the impact of such interventions on patient survival in sub-Saharan Africa.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Omullo FP and Kitheghe TK conceptualized and designed the study; Omullo FP, Kitheghe TK, Mark MM, and Ng’ang’a AK were responsible for data curation and formal analysis; Mark MM, Parsimei MW, Kanyi WC, Ooko EA, and Sheikh IA participated in investigation and methodology; Omullo FP wrote the original draft; Omullo FP, Kitheghe TK, Gitumu JM, Gakuya AM, Gitonga GK, Ndung’u JA, and Nyaro EM participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the administration and staff of the Murang'a County Referral Hospital Renal Unit for their support in facilitating this research.

References

- Thurlow, JS; Joshi, M; Yan, G; Norris, KC; Agodoa, LY; Yuan, CM; Nee, R. Global Epidemiology of End-Stage Kidney Disease and Disparities in Kidney Replacement Therapy. Am J Nephrol 2021, 52, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiseha, T; Osborne, NJ. Burden of end-stage renal disease of undetermined etiology in Africa. Ren Replace Ther 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, SF; Mwangi, M; Mutua, MK; Kibachio, J; Hussein, A; Ndegwa, Z; Owondo, S; Asiki, G; Kyobutungi, C. Prevalence and factors associated with pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus in Kenya: results from a national survey. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J; Manji, S; Smith, C; Nambafu, J; Ochola, A; Barasa, L; Amir, F; Abdalla, H; Jowi, S; Mithi, C; Patel, R; Ali, SK. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among clients seeking care at Selected Healthcare Facilities in Kenya. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0334255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, SJ; Lee, JH. Hemodialysis as a life-sustaining treatment at the end of life. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2018, 37, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannor, EK; Davidson, B; Nlandu, YM; Ndaza, V; Elrggal, ME; Kalysubula, R; Okpechi, IG. Global Disparities in Access and Utilization of Dialysis - Africa, the Disadvantaged Continent. Adv Kidney Dis Health 2025, 32, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venegas-Ramírez, J; Hernández-Fuentes, GA; Palomares, CS; Diaz-Martinez, J; Navarro-Cuellar, JI; Calvo-Soto, P; Duran, C; Tapia-Vargas, R; Espíritu-Mojarro, AC; Figueroa-Gutiérrez, A; Guzmán-Esquivel, J; Antonio-Flores, D; Meza-Robles, C; Delgado-Enciso, I. Vascular Access Type and Survival Outcomes in Hemodialysis Patients: A Seven-Year Cohort Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025, 61, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X; Hu, N; Song, D; Liu, L; Chen, Y. A meta-analysis of the impact of initial hemodialysis access type on mortality in elderly incident hemodialysis population. BMC Geriatr 2025, 25, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashuntantang, G; Osafo, C; Olowu, WA; Arogundade, F; Niang, A; Porter, J; Naicker, S; Luyckx, VA. Outcomes in adults and children with end-stage kidney disease requiring dialysis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017, 5, e408–e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulasi, II; Awobusuyi, O; Nayak, S; Ramachandran, R; Musso, CG; Depine, SA; Aroca-Martinez, G; Solarin, AU; Onuigbo, M; Luyckx, VA; Ijoma, CK. Chronic Kidney Disease Burden in Low-Resource Settings: Regional Perspectives. Semin Nephrol 2022, 42, 151336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maritim, PKK; Twahir, A; Davids, MR. Global Dialysis Perspective: Kenya. Kidney360 2022, 3, 1944–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabinga, SK; Kayima, JK; McLigeyo, SO; Ndungu, JN. Hemodialysis vascular accesses in patients on chronic hemodialysis at the Kenyatta National Hospital in Kenya. J Vasc Access 2019, 20, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msilanga, D; Shoo, J; Mngumi, J. Patterns of vascular access among chronic kidney disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis at Muhimbili National Hospital. A single-centre cross-sectional study. PLOS Glob Public Health 2024, 4, e0003678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubu, AO; Olusesi, OT; Lawal, FI; Abib, OM; Megbuwawon, TC; Olalude, OE; Bakare, T; Almustapha, H. Economic cost of end-stage renal disease in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol 2025, 26, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, L; Baker, P; Hangoma, P; Barasa, E; Hamidi, V; Chalkidou, K. Dialysis in Africa: the need for evidence-informed decision making. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e476–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, BM; Hailu, MK; Ayenew, YE; Ewunetu, M; Aytenew, TM; Kebede, AG; Kassa, BD; Ayen, AA; Abere, Y. Mortality and its predictors among patients undergoing hemodialysis in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, JT; Mwangi, J; Subramani, S; Kaseje, D; Ashuntantang, G; Luyckx, VA. Challenges to the right to health in sub-Saharan Africa: reflections on inequities in access to dialysis for patients with end-stage kidney failure. Int J Equity Health 2022, 21, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y; Lee, JW; Yoon, SH; Yun, SR; Kim, H; Bae, E; et al. Importance of dialysis specialists in early mortality in elderly hemodialysis patients: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Scientific Reports. Internet. 2024 Jan 22. cited 2025 Nov 22., 14, pp. 1927–7. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-52170-9.

- Pereira, M; Tocino, MLS; Mas-Fontao, S; Manso, P; Burgos, M; Carneiro, D; Ortiz, A; Arenas, MD; González-Parra, E. Dependency and frailty in the older haemodialysis patient. BMC Geriatr 2024, 24, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, GC; Kalantar-Zadeh, K; Ng, JK; Tian, N; Burns, A; Chow, KM; Szeto, CC; Li, PK. Frailty in patients on dialysis. Kidney Int 2024, 106, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, E; Cuevas-Budhart, MA; Cedillo-Flores, R; Candelario-López, J; Jiménez, R; Flores-Almonte, A; Ramos-Sanchez, A; Divino Filho, JC. Is central venous catheter in haemodialysis still the main factor of mortality after hospitalization? BMC Nephrol 2024, 25, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portolés, J; López-Gómez, JM; Aljama, P. A prospective multicentre study of the role of anaemia as a risk factor in haemodialysis patients: the MAR Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007, 22, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F; Pisoni, RL; Combe, C; Bommer, J; Andreucci, VE; Piera, L; Greenwood, R; Feldman, HI; Port, FK; Held, PJ. Anaemia in haemodialysis patients of five European countries: association with morbidity and mortality in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004, 19, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).