Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Location

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Participant Identification

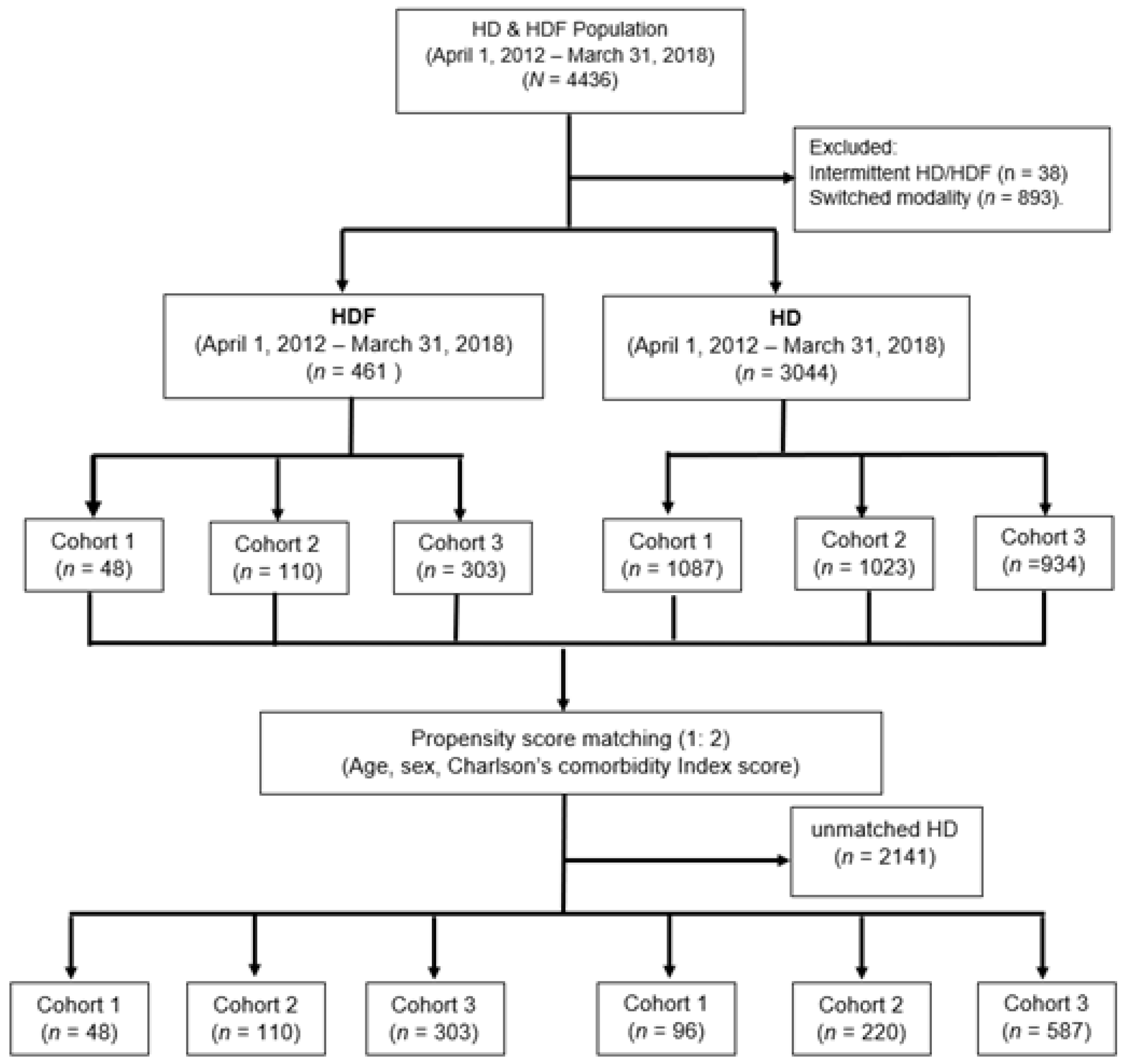

2.5. Matching

2.6. Final Sample

2.7. Definition of Variables

2.8. Definition of Outcome

2.9. Data Analysis

2.10. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of HDF Patients

3.2. Evaluation of Treatment Modality

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanafusa N, Abe M, Tsuneyoshi N, Hoshino J, et al. Current Status of Chronic Dialysis Therapy in Japan (as of December 31, 2022). Article in Japanese. Nihon Toseki Igakkai Zasshi. 2023, 56, 473–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafusa N, Fukagawa M. Global Dialysis Perspective: Japan. Kidney360 May 2020, 1, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akizawa T, Koiwa F. Clinical expectation of on-line hemodiafiltration: A Japanese Perspective. Blood Purif 2015, 40 (suppl 1), 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduell F, Moreso F, Pons M, et al. High-efficiency postdilution on-line hemodiafiltration reduces all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients [published correction appears in J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 25, 1130]. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 24, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankestijn PJ, Vernooij RWM, Hockham C, et al. Effect of Hemodiafiltration or Hemodialysis on Mortality in Kidney Failure. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffl, H. Online hemodiafiltration and mortality risk in end-stage renal disease patients: A critical appraisal of current evidence. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2019, 38, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See EJ, Hedley J, Agar JWM, et al. Patient survival on haemodiafiltration and haemodialysis: a cohort study using the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019, 34, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaud B, Bragg-Gresham JL, Marshall MR, et al. Mortality risk for patients receiving hemodiafiltration versus hemodialysis: European results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduell F, Varas J, Ramos R, et al. Hemodiafiltration Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Incident Hemodialysis Patients: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Am J Nephrol 2017, 46, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomo T, Larkina M, Shintani A. et al. Changes in practice patterns in Japan from before to after JSDT 2013 guidelines on hemodialysis prescriptions: results from the JDOPPS. BMC Nephrol 2021, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, H. Development of on-line hemodiafiltration in Japan. Ren Replace Ther. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer M, Frieze A, Pittel B. (1993). The Average Performance of the Greedy Matching Algorithm. Ann Appl Probab. 1993, 3, 526–552. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cai H, Li C, Jiang Z, Wang L, Song J, et al. Optimal Caliper Width for Propensity Score Matching of Three Treatment Groups: A Monte Carlo Study. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e81045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada M, Arai H. Long-Term Care System in Japan. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2020, 24, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, Muggivan A, Quan H, Ghali WA. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004, 57, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim SW, Akiyama T, Morishita A. PNS73 Retrospective Study for Comorbidities in ACTIVE Population Using Japanese Health Insurance Claims Database. Value Health Reg Issues. 2022, 22 (Suppl), S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T. , Sugitani, T., Nishimura, T., & Ito, M.. Validation and Recalibration of Charlson and Elixhauser Comorbidity Indices Based on Data From a Japanese Insurance Claims Database. Jpn J Pharmacoepidemiol/Yakuzai ekigaku. 2019, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ooba N, Setoguchi S, Ando T, et al. Claims-based definition of death in Japanese claims database: validity and implications. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e66116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai M, Ohtera S, Iwao T, et al. Validation of claims data to identify death among aged persons utilizing enrollment data from health insurance unions. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019, 24, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. Some Methods for Strengthening the Common χ2 Tests. Biometrics. 1954, 10, 417–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P. Tests for Linear Trends in Proportions and Frequencies. Biometrics. 1955, 11, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonckheere, AR. A Distribution-Free k-Sample Test Against Ordered Alternatives. Biometrika. 1954, 41, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduell F, Varas J, Ramos R, et al. Hemodiafiltration Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Incident Hemodialysis Patients: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Am J Nephrol. 2017, 46, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See EJ, Hedley J, Agar JWM, et al. Patient survival on haemodiafiltration and haemodialysis: a cohort study using the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019, 34, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masakane I, Kikuchi K, Kawanishi H. Evidence for the clinical advantages of predilution on-line hemodiafiltration. Contib Nephrol. 2017, 189, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Masakane I, Sakurai K. Current approaches to middle molecule removal: room for innovation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018, 33 (Suppl 3), iii12–iii21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royston P, Parmar MK. Restricted mean survival time: an alternative to the hazard ratio for the design and analysis of randomized trials with a time-to-event outcome. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego C, Sbolli M, Specchia C, et al. Utility of Restricted Mean Survival Time Analysis for Heart Failure Clinical Trial Evaluation and Interpretation. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim DH, Li X, Bian S, Wei LJ, Sun R. Utility of Restricted Mean Survival Time for Analyzing Time to Nursing Home Placement Among Patients With Dementia [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Mar 1;4, e213081]. JAMA Netw Open. 2021, 4, e2034745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Aharon O, Magnezi R, Leshno M, Goldstein DA. Median Survival or Mean Survival: Which Measure Is the Most Appropriate for Patients, Physicians, and Policymakers? Oncologist. 2019, 24, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penne EL, Blankestijn PJ, Bots ML, et al. Effect of increased convective clearance by on-line hemodiafiltration on all cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic hemodialysis patients - the Dutch CONvective TRAnsport STudy (CONTRAST): rationale and design of a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN38365125]. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2005, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi K, Hamano T, Wada A, Nakai S, Masakane I. Predilution online hemodiafiltration is associated with improved survival compared with hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin SK, Jo YI. Why should we focus on high-volume hemodiafiltration? Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2022, 41, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cohort | Cohort 1 April 1, 2012 – March 31, 2014 |

Cohort 2 April 1, 2014 – March 31, 2016 |

Cohort 3 April 1, 2016 – March 31, 2018 |

All (April 1, 2012 – March 31, 2018) |

|||||||||||||||

| HDF (N = 48) | Died (N = 16, 33%) | HDF (N = 110) | Died (N = 26, 24%) | HDF (N = 305) | Died (N = 57, 19%) | HDF (N = 463) | Died (N = 99, 21%) | ||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | *P | §P | ||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||||

| <75 | 24 | 50.0 | 8 | 33.3 | 58 | 52.7 | 7 | 12.1 | 151 | 49.5 | 14 | 9.27 | 233 | 50.3 | 29 | 12.5 | 0.74 | 0.34 | |

| ≥75 | 24 | 50.0 | 8 | 33.3 | 52 | 47.3 | 19 | 36.5 | 154 | 50.5 | 43 | 27.9 | 230 | 49.7 | 70 | 30.4 | |||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 24 | 50.0 | 8 | 33.3 | 50 | 45.5 | 12 | 24.0 | 169 | 55.4 | 37 | 21.9 | 243 | 52.5 | 57 | 23.5 | 0.16 | 0.34 | |

| Female | 24 | 50.0 | 8 | 33.3 | 60 | 54.6 | 14 | 23.3 | 136 | 44.6 | 20 | 14.7 | 220 | 47.5 | 42 | 19.1 | |||

| Heart Failure | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | 23 | 47.9 | 5 | 21.8 | 44 | 40.0 | 8 | 18.2 | 146 | 47.9 | 24 | 16.4 | 213 | 46.0 | 37 | 17.4 | 0.50 | 0.30 | |

| Yes | 25 | 52.1 | 11 | 44.0 | 66 | 60.0 | 18 | 27.2 | 159 | 52.1 | 33 | 20.8 | 250 | 54.0 | 62 | 24.8 | |||

| Diabetes | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | 39 | 81.3 | 15 | 38.5 | 79 | 71.8 | 20 | 25.3 | 204 | 66.9 | 36 | 17.7 | 322 | 69.6 | 71 | 22.1 | 0.03 | 0.88 | |

| Yes | 9 | 18.8 | 1 | 11.1 | 31 | 28.2 | 6 | 19.4 | 101 | 33.1 | 21 | 20.8 | 141 | 30.5 | 28 | 19.9 | |||

| Malignancy | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | 37 | 77.1 | 12 | 32.4 | 98 | 89.1 | 23 | 23.5 | 272 | 89.2 | 48 | 17.7 | 407 | 87.9 | 83 | 20.4 | 0.57 | 0.55 | |

| Yes | 11 | 22.9 | 4 | 36.4 | 12 | 10.9 | 3 | 25.0 | 33 | 10.8 | 9 | 27.3 | 56 | 12.1 | 16 | 28.6 | |||

| Stroke | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | 22 | 45.8 | 7 | 31.9 | 52 | 47.3 | 12 | 23.1 | 167 | 54.8 | 34 | 20.4 | 241 | 52.1 | 53 | 21.9 | 0.12 | 0.64 | |

| Yes | 26 | 54.2 | 9 | 34.6 | 58 | 52.7 | 14 | 24.1 | 138 | 45.3 | 23 | 16.7 | 222 | 47.9 | 46 | 20.7 | |||

| Dementia | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | 40 | 83.3 | 10 | 25.0 | 98 | 89.1 | 23 | 23.5 | 256 | 83.9 | 36 | 14.1 | 394 | 85.1 | 69 | 17.5 | 0.60 | 0.45 | |

| Yes | 8 | 16.7 | 6 | 75.0 | 12 | 10.9 | 3 | 25.0 | 49 | 16.1 | 21 | 42.9 | 69 | 14.9 | 30 | 43.5 | |||

| SCL | |||||||||||||||||||

| NA | 33 | 68.6 | 15 | 93.8 | 79 | 71.8 | 16 | 61.5 | 206 | 67.5 | 32 | 18.4 | 318 | 68.7 | 63 | 24.7 | 0.29 | 0.01 | |

| Low | 9 | 18.8 | 0 | 0.00 | 13 | 11.8 | 7 | 26.9 | 31 | 10.2 | 4 | 14.8 | 53 | 11.5 | 11 | 26.2 | |||

| Moderate | 5 | 10.5 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.00 | 44 | 14.4 | 14 | 46.7 | 61 | 13.2 | 14 | 23.4 | |||

| High | 1 | 2.08 | 1 | 6.25 | 6 | 5.45 | 3 | 11.5 | 24 | 7.87 | 7 | 41.1 | 31 | 6.70 | 11 | 55.0 | |||

| m-CCI | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mild | 19 | 39.6 | 6 | 39.6 | 31 | 28.2 | 3 | 9.68 | 108 | 35.4 | 20 | 18.5 | 158 | 35.1 | 29 | 18.4 | 0.67 | 0.81 | |

| Moderate | 14 | 29.8 | 3 | 29.2 | 42 | 38.2 | 15 | 35.8 | 100 | 32.8 | 13 | 13.0 | 156 | 33.7 | 31 | 19.9 | |||

| Severe | 15 | 31.3 | 7 | 31.3 | 37 | 33.6 | 8 | 21.6 | 97 | 31.8 | 24 | 24.7 | 149 | 32.2 | 39 | 26.2 | |||

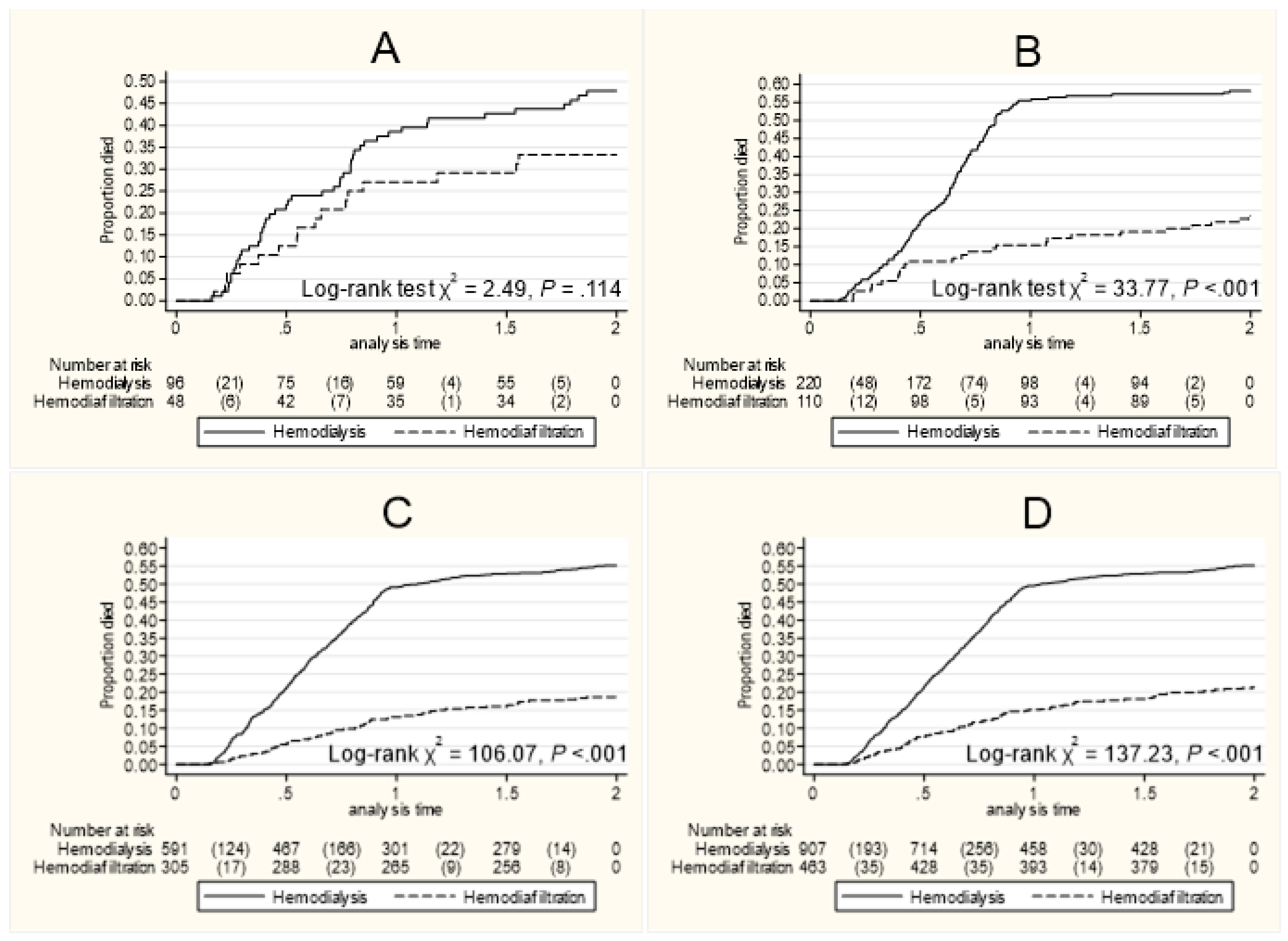

| Cox Model | Restricted Mean Survival Time (RMST) | ||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | M | 95% CI | Diff | 95% CI | P | Diffa | 95% CI | P | |

| Cohort 1 | |||||||||||

| HD | Ref. | 1.13 | 1.03–1.24 | ||||||||

| HDF | 0.62 | 0.34–1.13 | .117 | 1.26 | 1.12–1.40 | 0.13 | 0.30–0.15 | .154 | - | - | - |

| Cohort 2 | |||||||||||

| HD | Ref. | 1.15 | 1.06–1.24 | ||||||||

| HDF | 0.33 | 0.22–0.51 | <.000 | 1.65 | 1.55–1.75 | 0.50 | 0.37–0.63 | <.000 | 0.45 | 0.31–0.59 | <.000 |

| Cohort 3 | |||||||||||

| HD | Ref. | 1.19 | 1.14–1.28 | ||||||||

| HDF | 0.27 | 0.20–0.36 | <.000 | 1.67 | 1.62–1.72 | 0.48 | 0.40–0.55 | <.000 | 0.45 | 0.37–0.52 | <.000 |

| All | |||||||||||

| HD | Ref. | 1.23 | 1.18–1.27 | ||||||||

| HDF | 0.32 | 0.26–0.40 | <.001 | 1.70 | 1.65–1.75 | 0.47 | 0.41–0.54 | <.000 | 0.45 | 0.37–0.52 | <.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).