1. Introduction

Bloodstream infection (BSI) remains a substantial global health risk, playing a significant role in mortality, disability, and healthcare expenses [

1]. However, promptly identifying and initiating appropriate and efficient treatment lead to favorable outcomes [

2]. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study report, sepsis remains the second most common cause of death worldwide, leading to almost 7.7 million fatalities in 2019 [

3]. These data led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare sepsis a global health priority [

4]

. The 2016 sepsis definition defines sepsis as a state marked by the life-threatening malfunctioning of organs, caused by an unregulated reaction of the body to an infection. Sepsis can result from a wide range of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Approximately 90% of cases can be attributable to bacterial causes [

5,

6]. Patients with End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) require hemodialysis (HD) and are at risk of contracting BSI, which can result in consequences such as sepsis, septic shock, multiorgan failure, and death [

7]. Bacterial sepsis is the second most common cause of death in patients with HD, behind cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

8,

9]. The main factors contributing to the substantial risk of BSI and sepsis in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who undergo hemodialysis are vascular access, the hemodialysis method, and iron overload.

Furthermore, patients undergoing hemodialysis are at an elevated risk of experiencing serious infection and mortality as a result of multiple reasons. These factors comprise infections caused by pathogens that are resistant to multiple drugs, the frequent utilization of invasive procedures or devices in intensive care or critical care units, older age, and the existence of additional comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, malnutrition, anemia, and uremia [

8,

9,

10]. The selection of vascular access in hemodialysis is also correlated with the occurrence of infection. BSI primarily affects patients who are receiving dialysis through a central venous catheter (CVC), with arteriovenous graft (AFG) and arteriovenous fistula (AVF) being less common [

11]. Previous studies have shown a significantly higher infection rate in patients who get dialysis using a CVC compared to those who use AVG or AVF [

8,

11,

12]. Despite the fact that AVF has a lower likelihood of infection and death, most patients in the United States initiate hemodialysis with a CVC or AVG [

10]. In Oman, the primary approach to dialysis is the utilization of CVCs, rather than AVFs and AVGs [

8].

The main clinical features displayed by sepsis patients comprise hypotension, body temperature exceeding 38.3ºC or falling below 36ºC, tachycardia, tachypnea, indications of inadequate tissue perfusion (such as alterations in mental status, restlessness, and oliguria), and signs of vital organ dysfunction. The laboratory abnormalities observed in sepsis patients can be attributed to the root cause of sepsis, inadequate blood flow to tissues, or dysfunction of organs due to sepsis. The condition can present with leukocytosis or leucopenia, arterial hypoxemia, hyperglycemia without diabetes, increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and creatinine, abnormalities in blood clotting, low platelet count, high levels of bilirubin, low sodium levels, high potassium levels (suggestive of adrenal insufficiency), high lactate levels, elevated inflammatory cytokines, increased serum procalcitonin (PCT), and other indicators [

13]. Serum PCT and lactate levels have the potential to serve as diagnostic indicators for sepsis and predictors of death in sepsis patients, surpassing other conventional markers of sepsis [

14,

15].

Sepsis can arise from a wide range of bacterial infections. Nevertheless, the occurrence of pathogenic bacteria and their vulnerability to antimicrobial medications differ according on the geographic region.

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CONS) and

Staphylococcus aureus are the most common gram-positive bacteria linked to BSI. While

Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Klebsiella pneumoniae, are the common gram-negative bacteria associated with BSI in HD patients [

7]. A prior investigation conducted in Palestine revealed that over 80% of BSIs in hemodialysis patients were attributed to gram-positive microorganisms, with

CONS being the predominant pathogen. The study identified

E. coli and

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as the predominant gram-negative pathogens [

16]. Another study found that 32.2% of hemodialysis patients experienced bloodstream infections (BSI), with

CONS being the primary cause, followed by

S. aureus and

E. coli. Patients infected with multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens and those who required intensive care admission and mechanical ventilation had a higher mortality rate [

17]. There is notable variation in the frequency of sepsis occurrence and fatality rates among sepsis patients in hospitals across various geographic regions [

18,

19]. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize sepsis monitoring and increase physicians' understanding of the specific factors in the local environment that contribute to bacterial sepsis and the trends in antibiotic resistance. Furthermore, it is imperative to improve infection control measures and advocate for responsible use of antibiotics in order to successfully reduce the impact of sepsis and the resulting death rate in hemodialysis patients [

20]. This study aims to analyze the clinical and laboratory characteristics of hemodialysis patients diagnosed with BSI, including sepsis and septic shock at a secondary-care hospital in Oman from January 2018 to December 2022. The study will also focus on the bacterial causes of BSI and antibiotic resistance patterns, as well as the outcomes of BSI in the study subjects.

The significance of conducting the study lies in its emphasis on the prevalence, bacterial aetiology, and consequences of bloodstream infections in haemodialysis patients in Oman, an area with little prior research on the subject. The study is unique as it examines local epidemiological patterns, which may differ greatly from worldwide trends due to regional variances in bacterial resistance and health care practices. The study fills gaps in the current understanding of sepsis and its management in the Omani context, providing critical insights into local infection rates and resistance patterns. The findings can help lead the creation of personalised infection control strategies and antibiotic stewardship programs, with the ultimate objective of improving patients’ outcomes and lowering mortality rates in haemodialysis patients. The study contributes valuable data that can inform local healthcare strategies, enhance infection control practices, and guide the development of targeted antibiotic stewardship programs. These insights can improve patient management and outcomes address the urgent need for region-specific infection control measures and providing foundation for the future research in similar settings.

2. Materials and Methods

A single-center retrospective study was conducted at Sohar Hospital, a secondary-care hospital situated in North Batinah region of Oman. Retrospective study design was chosen to capitalize on existing data and swiftly examine trends over s substantial time period. The strategy is both cost-effective and time-efficient, allowing for complete analysis without the need for further data collecting. It allows for the assessment of clinical outcomes, bacterial profiles, and antibiotic resisting patterns in a large haemodialysis patient population. Additionally, a retrospective analysis is ideal for investigating historical trends and outcomes, providing useful insights into local infection patterns and assisting in the creation of targeted infection control methods.

On the other hand, the study was approved by the Ethical and Review committee of the Ministry of Health, Oman as well as from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences (COMHS), National University of Science and Technology (NU) wide under approval number MOH/CSR/23/27627. The study included all hemodialysis patients diagnosed with BSI, including sepsis and septic shock at Sohar hospital from January 2018 to December 2023 were included. The pertinent data of study subjects such as demographic characteristics, bacterial profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern, clinic-laboratory characteristics, underlying risk factors including comorbidities, treatment and outcomes was retrieved from the hospital’s electronic health records.

Sample size calculation: The sample size was calculated using

www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html.

Assuming 150 hemodialysis patients who have developed BSI and applying 95% confidence interval and 5% margin error, the minimum sample size was calculated as 109. The sample size was chosen to maintain a balance between statistical power and practicalities, providing for accurate representation of the population while accounting for potential data variability. With the current sample size, the study efficiently detects significance changes and trends providing valuable insights into the epidemiology, bacterial profiles, and consequences of BSI in the specific patient group. The method is critical for creating evidence-based infection control and treatment plans.

Inclusion criteria: All hemodialysis patients who have developed BSI including sepsis, and septic shock, confirmed by positive blood culture as per the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria during January 2018 to December 2023 were included in the study [

23].

Exclusion criteria: The study excluded hemodialysis patients who had not developed bloodstream infections (BSI) or had negative blood culture reports, as well as those with incomplete data. Furthermore, the study excluded the isolation of bacteria from blood samples in cases where potential contamination was taken into account.

Bacterial identification and antibiotics susceptibility testing: Blood samples received at the Sohar microbiology laboratory were cultured in BACT/Alert procured from Biomerieux company (

https://www.biomerieux.com/us/en.html) as per standard Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria [

23]. Pathogen identification up to the species was performed by convention identification method or VITEK II automated microbiological system as per CLSI criteria [

23]. Antibiotic susceptibility testing of the isolated pathogen was performed by conventional method by using Mueller Hinton agar plate or VITEK II automated microbiological system. Broth microdilution method was performed for vancomycin and colistin antibiotic susceptibility testing. Disc diffusion method for antibiotic susceptibility testing for antibiotics amikacin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ampicillin, cefuroxime, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, imipenem, meropenem, tigecycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, chloramphenicol was performed as per CLSI guidelines [

23]. Results were interpreted as sensitive, resistant, and intermediate as per the standard CLSI guidelines [

23].

Statistical analysis: Data were entered into spreadsheet files and analyzed using the R package GTSUMMARY. Means, standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies, percentages for categorical variables were calculated. Independent t-tests (and Mann Whitney Test wherever appropriate) for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables to compare characteristics between groups were used. Univariate odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each characteristic to assess the association with mortality was also calculated. Statistical significance of each characteristic was considered with a p value <0.05. Infinite odds ratio was handled appropriately by considering it as a strong indicator of mortality.

Case definitions:

Bacteremia was defined as the presence of a positive pathogen (except contamination) in blood culture [

21,

22].

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is a widespread inflammatory response to a variety of severe clinical insults. This syndrome is clinically recognized by the presence of two or more of the following: Temperature >38 °C or <36 °C, Heart rate >90 beats/min, Respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <32 mmHg, WBC >12,000 cells/mm3, <4000 cells/mm3, or >10 percent immature (band) forms [

21,

22].

Sepsis: Sepsis is the systemic response to infection. Thus, in sepsis, the clinical signs describing SIRS are present together with definitive evidence of infection [

21,

22].

Severe sepsis: Sepsis is considered severe when it is associated with organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension. The manifestations of hypoperfusion may include, but are not limited to, lactic acidosis, oliguria, or an acute alteration in mental status [

21,

22].

Septic shock: Septic shock is sepsis with hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation. It includes perfusion abnormalities such as lactic acidosis, oliguria, or an acute alteration in mental status. Patients receiving inotropic or vasopressor agents may not be hypotensive at the time that perfusion abnormalities are measured [

21,

22].

3. Results

Out of 1332 patients who received hemodialysis from 2018 to 2022, 148 (11.1%) developed BSI, and were included in the study.

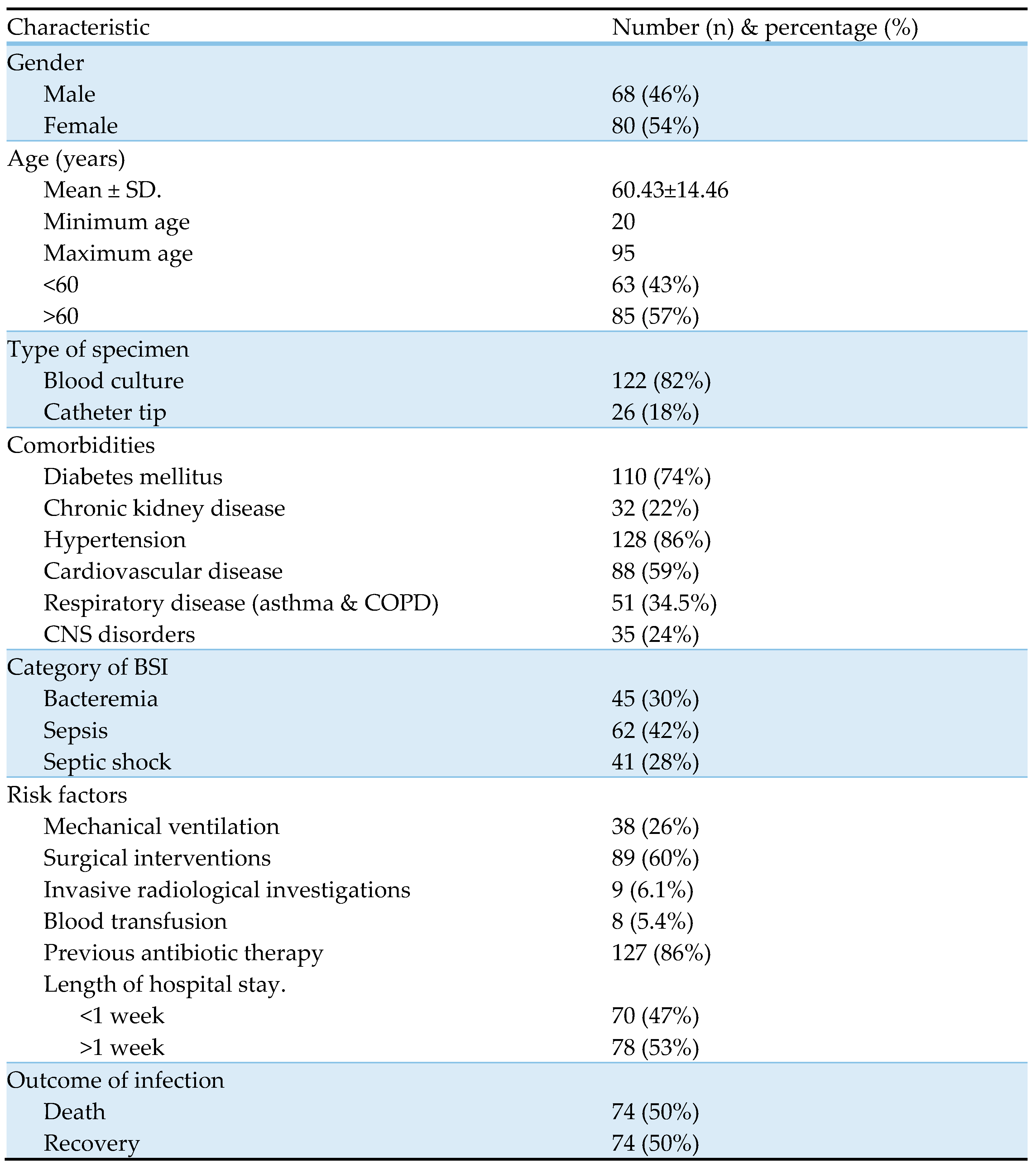

Table 1 represents baseline characteristics of the study subjects. The age of the study subjects ranged from 20 to 95 years, with a mean age of 60.43±14.46. Bacteria were more frequently isolated from females (54%) and in people aged > 60 years (57%). Most of the study subjects had hypertension (128, 86%) and diabetes mellitus (110, 74%) as the predominant comorbidities, followed by cardiovascular diseases (88, 59%), pulmonary diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (51, 34.5%), Chronic neurological disorders (35, 24%), and chronic kidney diseases (32, 22%). Previous antibiotic therapy within 3 months (127, 86%), surgical interventions (89, 60%), and mechanical ventilation (38, 26%) were the major risk factors observed in our study subjects. Concerning a type of BSI, majority of patients were diagnosed with sepsis (62, 42%), followed by bacteremia (45, 30%) and septic shock (41, 28%). Out of 148 study subjects, 74 (50%) died of BSI and its complications.

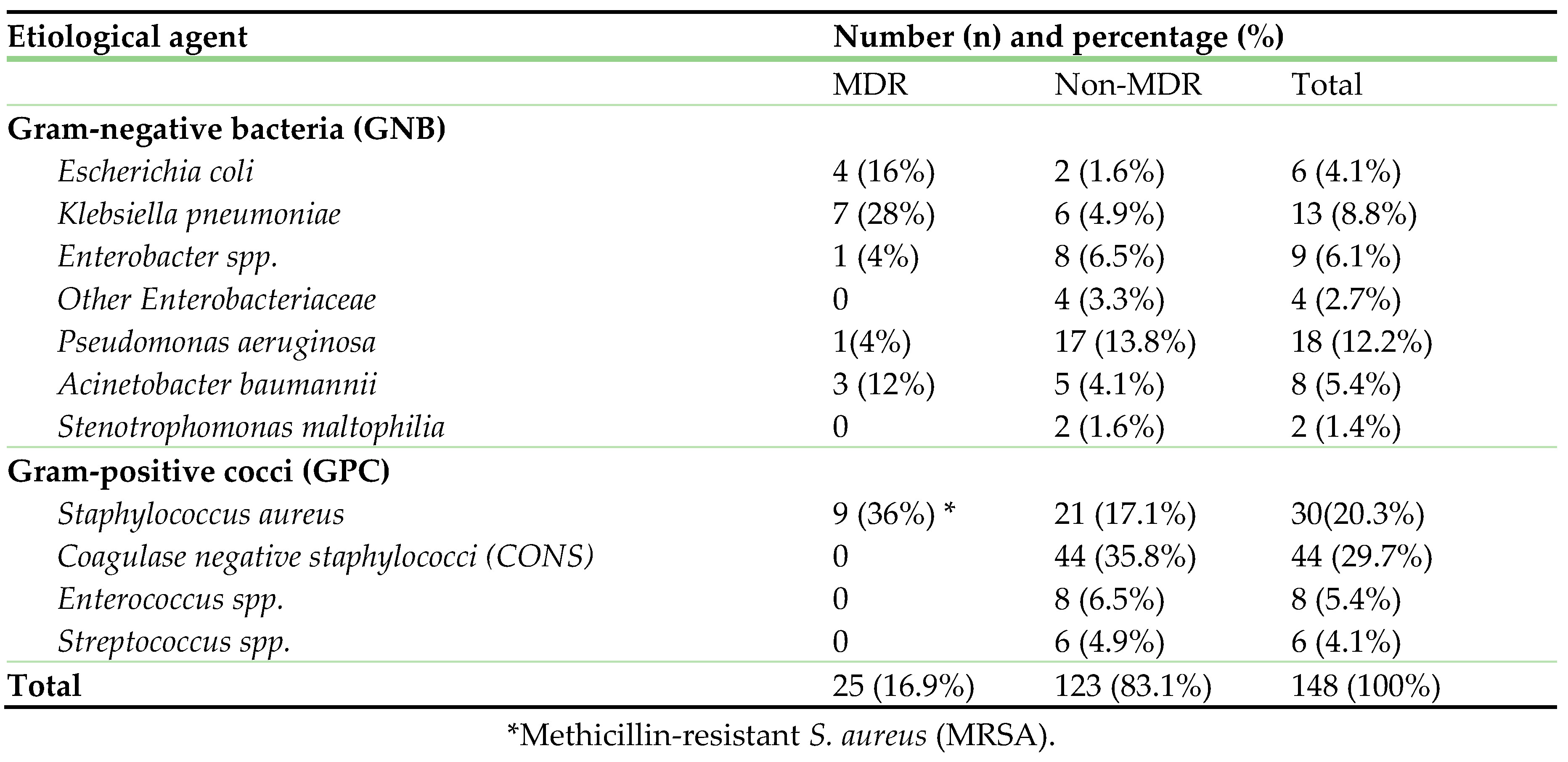

Table 2 displays the bacterial agents associated with BSI.

CONS (44, 29.7%) and

S. aureus, including

MRSA (30, 20.3%) were the predominant pathogens, followed by

P. aeruginosa (18, 12.2%),

K. pneumoniae (13, 8.8%), and others (≤ 5% each). Amongst, 16.9% (n=25) were multidrug-resistant pathogens.

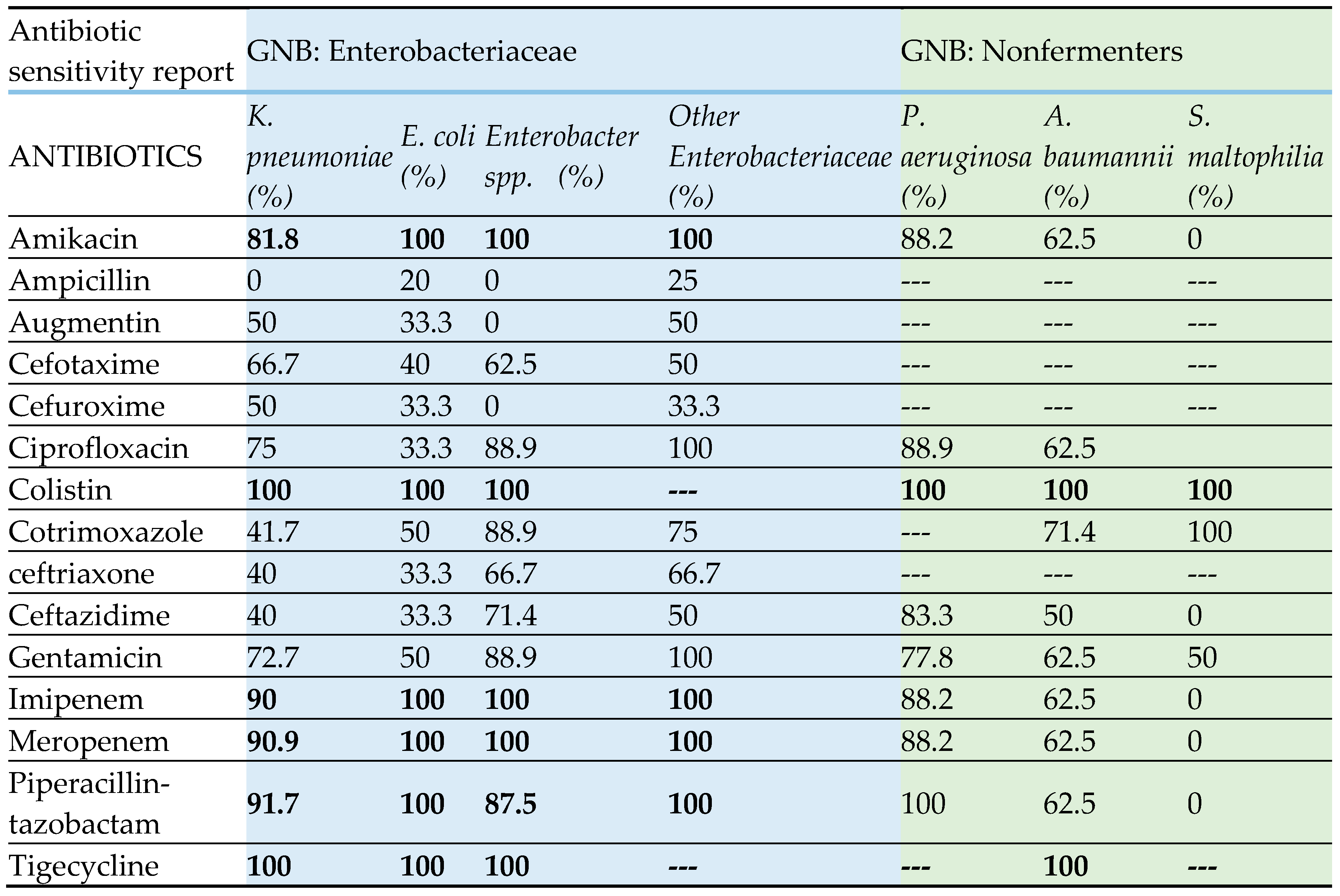

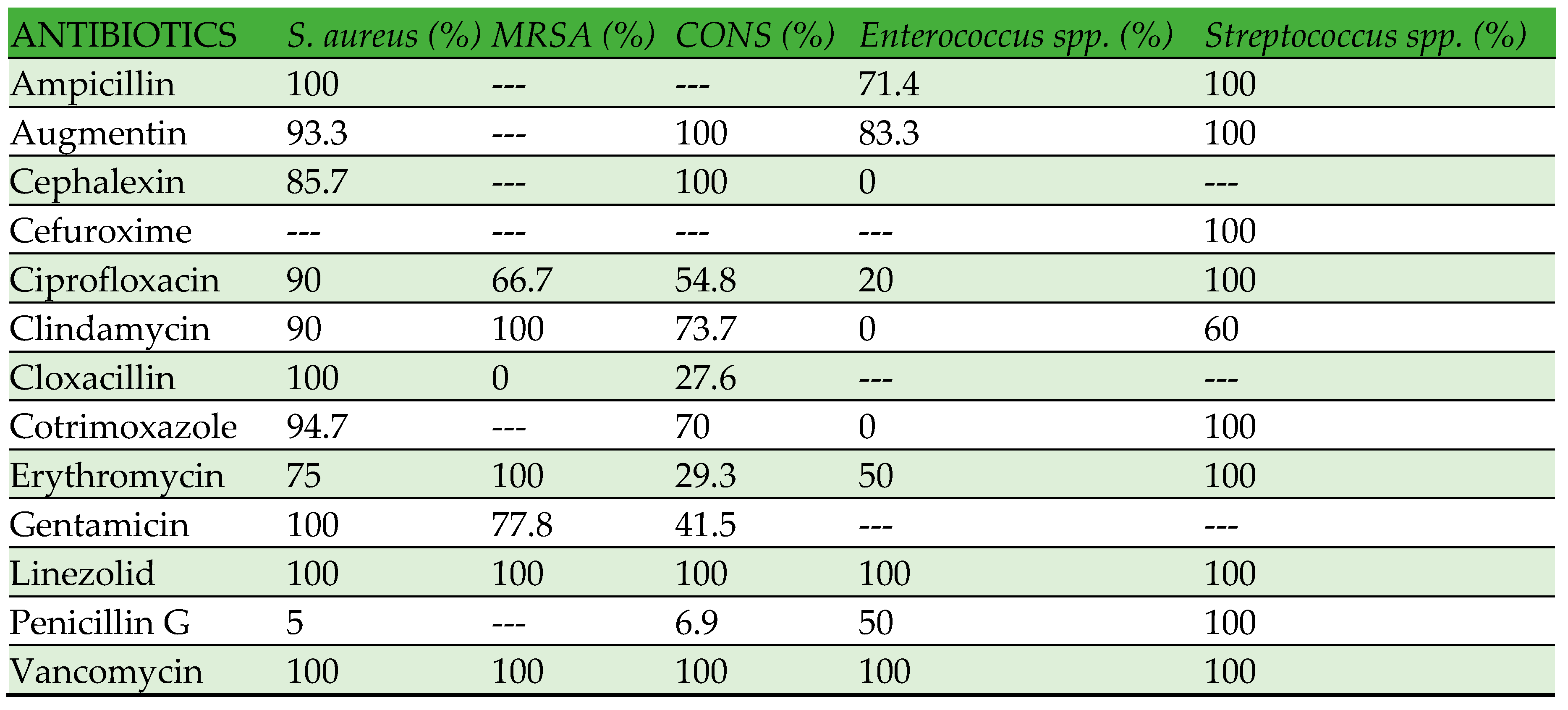

Table 3displays the antibiotic susceptibility pattern of gram-negative bacteria, while

Table 4 shows the antibiotic susceptibility pattern of gram-positive bacteria. Enterobacteriaceae have exhibited high susceptibility (80-100%) to amikacin, imipenem, meropenem, and piperacillin-tazobactam. Conversely, no strain has demonstrated resistance to colistin and tigecycline. All members of the Enterobacteriaceae family have exhibited low susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics, including cephalosporins, with a range of 0-70%. Within the category of nonfermenters,

P. aeruginosa has exhibited high susceptibility to all the antibiotics that were tested, ranging from 77% to 100%. On the other hand,

A. baumannii has displayed a low susceptibility to all the antibiotics that were tested, with a range of 50% to 70%. Nevertheless, all strains of

A. baumannii exhibited susceptibility to colistin and tigecycline.

S. maltophilia has exhibited high susceptibility (100%) to cotrimoxazole, but no susceptibility (0%) to amikacin, ceftazidime, carbapenems, and piperacillin-tazobactam. However, the quantity of

S. maltophilia is insufficient to accurately interpret the susceptibility pattern. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Augmentin) and Linezolid have demonstrated high efficacy (80-100%) against all gram-positive bacteria, whereas no strains have exhibited resistance to vancomycin. The susceptibility of gram-positive bacteria to other tested antibiotics exhibited variability, as indicated in

Table 4.

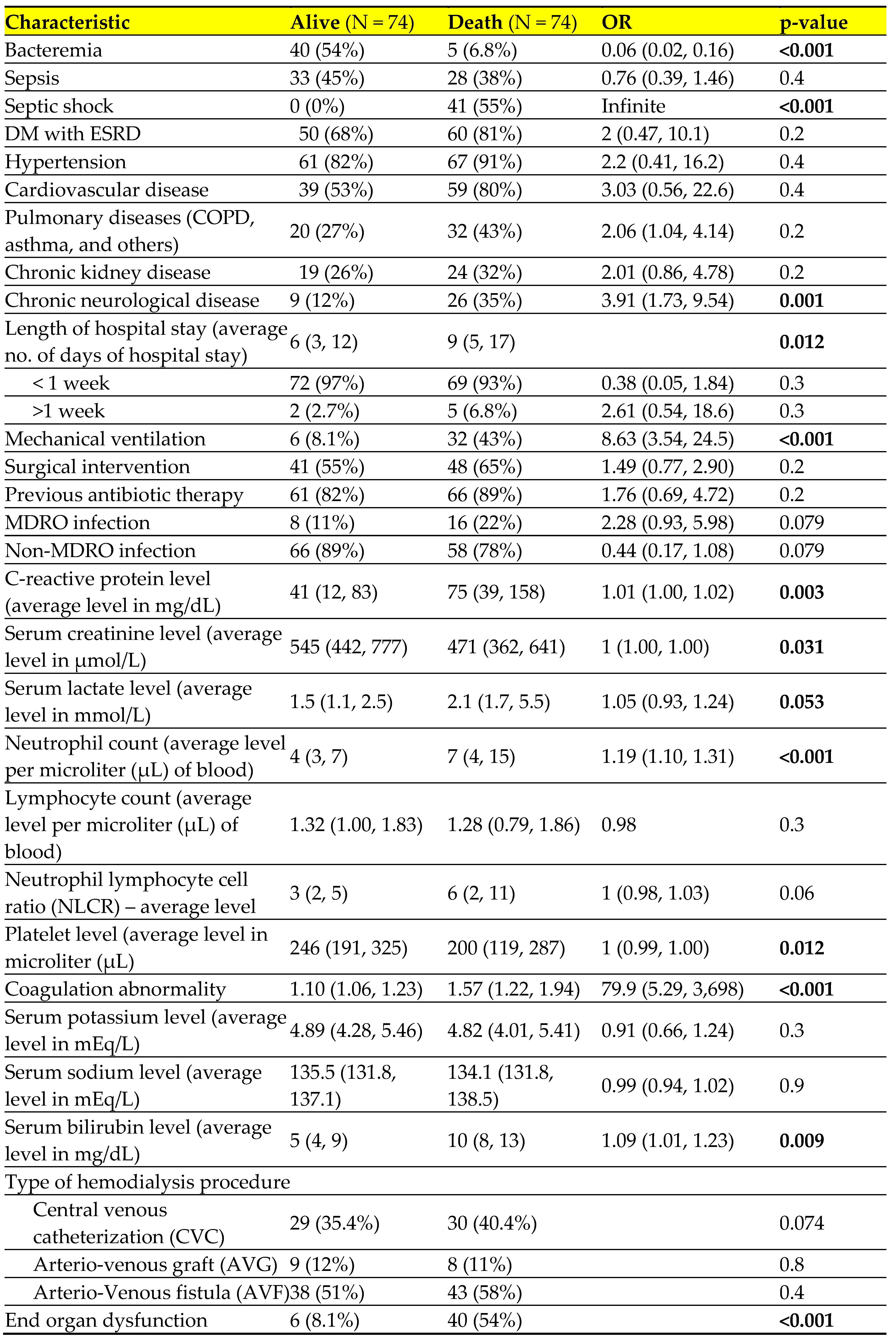

Table 5 presents the results of a univariate regression analysis that examines the risk factors associated with the outcome of infection. There was a strong correlation (p value <0.05) between patient mortality and factors including septic shock, mechanical ventilation, cardiovascular, neurological, and respiratory comorbidities, longer hospital stays, elevated levels of C-reactive protein, serum lactate, neutrophil count, and serum bilirubin. Additionally, patients with decreased platelet count, lower serum creatinine levels, and those who experienced end organ dysfunction were also more likely to die.

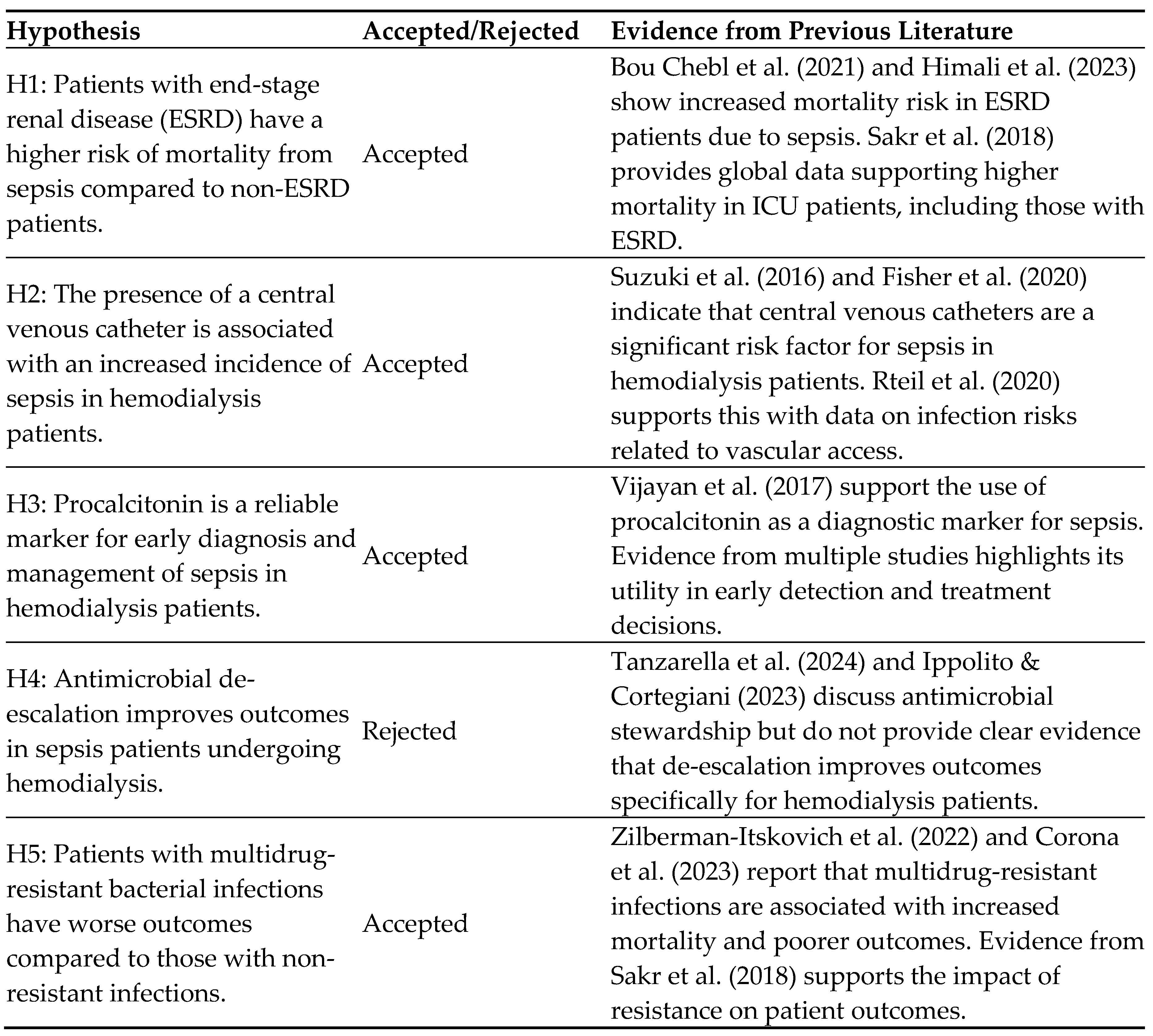

Hypothesis:

Table 6.

Table of Hypothesis.

Table 6.

Table of Hypothesis.

4. Discussion

This retrospective study is the first investigation conducted in Oman that systematically assesses BSI in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Additionally, it aims to analyze the risk factors associated with mortality in these study subjects. Hemodialysis patients have a greater susceptibility to infections compared to the general population. In a longitudinal study spanning 7 years, Powe et al. discovered that 11.7% of hemodialysis patients experienced at least one episode of BSI [

24]. In line with this discovery, 11.1% of the participants in our study were found to have microbiologically confirmed BSI. Deceased infected patients were significantly older in our study with an overall mean age of 60.43±14.46 which aligns with the findings of a similar study conducted by Can O et al. [

25]. Infection-related complications remain the primary causes of heightened morbidity and mortality among HD patients. There are several potential factors that could contribute to this, including weakened immune system, existing health conditions, medical procedures, and the strength of the pathogen [

17]. In this study, it was observed that the majority of the subjects had one or more comorbidities. The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension and diabetes mellitus, followed by cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, and chronic renal disorders. Furthermore, a significant number of patients were found to have been exposed to risk factors such as mechanical ventilation, invasive surgical or radiological procedures, blood transfusion, and previous antibiotic therapy. Abbasi et al. conducted a study that identified several significant risk factors for nosocomial BSI among hemodialysis patients. These risk factors include diabetes, a history of blood transfusion, longer duration of hemodialysis, longer hospital stays, and multiple catheter sites [

26].

The type of vascular access can impact the occurrence of infectious complications. A study conducted by Krzanowski M et al revealed a significant incidence of central venous catheter (CVC) infections, which were found to be associated with a higher mortality rate when compared to patients who had arteriovenous fistula (AVF) [

27]. According to a study conducted by Locham et al., CVC (31.2%) and AVG (30.6%) procedures were found to have a higher incidence of sepsis cases compared to AVF (22.9%) [

11]. Furthermore, patients with AVF had better survival rate and low hospitalization in a study by Kim et al. [

28]. Contrastingly, we did not find any significant difference in the relationship between the type of hemodialysis procedure and mortality. Patients with severe sepsis and septic shock face a considerably greater likelihood of death [

29]. In line with these findings, all patients with septic shock, and nearly half of the patients with sepsis in our study did not survive, while most of the patients with bacteremia survived.

There is a lack of information on the microbiology of infections in hemodialysis patients from Middle Eastern countries. Nevertheless, a study conducted in Lebanon revealed that the predominant pathogens linked to BSI in hemodialysis patients were coagulase-negative staphylococci (

CONS), followed by

S. aureus and

E. coli [

17]. We also found preponderance of

CONS and

S. aureus as the most common pathogens of BSI. Among gram-negatives, our study found

P. aeruginosa as the most prevalent pathogen, followed by

K. pneumoniae,

A. baumannii, and

E. coli. In contrast, a study conducted by Schamroth Pravda et al. revealed that K. pneumoniae was the most prevalent pathogen, with

S. aureus, CONS, E. coli, and

P. aeruginosa [

30].

The prevalence of infection in HD patients, causative agent, and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern widely varies geographically, contingent upon the specific hospital environment, infection control measures, and policies regarding antibiotic prescriptions. Hence, it is imperative to regularly monitor infection rates, etiology, antibiotic resistance patterns, and antibiotic prescribing guidelines in local healthcare establishments. The worldwide escalation in infection caused by multidrug-resistant organisms has become a grave concern. The indiscriminate utilization of antibiotics, lack of compliance with antibiotic stewardship, and inadequate implementation of infection control measures are considered significant factors that contribute to the increase in multidrug-resistant pathogens. The current study found a relatively low overall prevalence (16.9%) of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. In contrast, the study conducted by Rteil et al. found a high overall prevalence (31.4%) of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens among hemodialysis (HD) patients [

17]. Zilberman-Itskovich conducted a study which found that 35% of patients undergoing haemodialysis were infected with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) [

31]. Moreover, the presence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens is linked to increased mortality, as stated by Rteil et al. [

17]. This suggests there is a need for early initiation of most appropriate broad spectrum empirical antimicrobial therapy, considering local resistance patterns, followed by prompt de-escalation based on culture reports [

32]. Timely and appropriate antibiotic therapy is most beneficial for critically ill patients suffering from septic shock or severe sepsis. Multiple studies have documented that early and appropriate antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients leads to a decrease in hospital stay duration and mortality rate [

33]. The current study identified amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, linezolid, and vancomycin as the most effective options for empirical treatment of gram-positive bacterial infections in critically ill patients. For gram-negative pathogens, carbapenems and piperacillin-tazobactam were found to be the optimal choices. Our study also has demonstrated that colistin and tigecycline exhibit 100% sensitivity against gram-negative pathogens, however, their use as empirical drugs is restricted because of their potential toxic effects and are reserved for patients infected by pathogens that are resistant to all classes of antibiotics [

34]. Khilnani et al. recommended vancomycin as the preferred antibiotic for treating BSI caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), while linezolid and daptomycin are considered effective alternative options [

35]. Empirical therapy for gram-negative bacteria typically involves the administration of a fourth-generation cephalosporin, a carbapenem, or a combination of a β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor. In some cases, an aminoglycoside may also be included [

35]. Niederman MS et al. advocate for the use of similar empirical antimicrobial therapy guidelines [

36].

We conducted an analysis of the individual risk factors associated with mortality. The findings of our study indicate that older individuals had a lower survival rate compared to younger individuals (non-survival, 63±13 vs survival 57±15). Additionally, patients with septic shock, chronic neurological disease, mechanical ventilation, longer hospital stays, elevated c-reactive protein, increased serum lactate, higher neutrophil count, elevated bilirubin levels, decreased serum creatinine, decreased platelet levels, and end organ dysfunction also had lower survival rates. These findings were corroborative to findings of several studies [

37,

38,

39,

40].

5. Conclusions And Implications

Our research emphasizes the importance of BSI, particularly sepsis and septic shock in hemodialysis patients in Sohar hospital, Oman. BSIs were predominant in older people, especially with comorbidities. Coagulase negative staphylococci (CONS) and S. aureus were the predominant pathogens associated with BSI. Prolonged length of hospital stays, mechanical ventilation, and surgical intervention were the noted risk factors for adverse outcomes. Septic shock, neutrophilia, coagulation abnormality, increased serum lactate, bilirubin, c-reactive protein, and decreased platelet and serum creatinine level were the most significant indicators of mortality. These findings emphasize the immediate requirement for efficient surveillance, administration, and infection control strategies to decrease the impact of BSI and its associated complications in hemodialysis patients.

Sohar hospital’s infection control measures must be strengthened by developing stringent hygiene protocols, optimising hand hygiene practices, and ensuring correct sterilisation processes. The method will help to minimise the number of healthcare associated infections and increase overall patient safety. Moreover, implementing quick bacterial identification techniques and antibiogram testing will assist in the timely and accurate detection of illnesses. This innovation will allow for the timely beginning of suitable empirical medication, improving patient outcomes and misnaming the spread of resistance bacteria. Moreover, serum procalcitonin measurement should be combined with serum lactate estimation in all patients suspected of having sepsis. These biomarkers are crucial of mortality and can guide successful treatment decisions, which will assist develop strong management guidelines and eventually reducing sepsis-related mortality.

Our study has few limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design and reliance on data from the health registry. Furthermore, because of the retrospective nature of the study, there is a lack of information on several crucial predictors of sepsis and mortality such as procalcitonin. Secondly, there is a lack of molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance mechanisms and insufficient follow-up data on patient outcomes after they are discharged from the hospital. Finally, our study has a retrospective design and was conducted at a single center. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings may be limited, and the results of the study should be confirmed by a multicenter study. Future researchers should overcome these constraints by constructing multicenter prospective studies that increase the generalizability of findings while minimizing the biases inherent in retrospective methods. Comprehensive biomarkers tests, which include procalcitonin and other pertinent indications, will help to identify sepsis and its predictors. Moreover, molecular research of antibiotic resistance mechanisms will provide insights into the mechanisms hat drive resistance and lead more effective treatment techniques. To expand the evidence base even more, researchers should conduct enhanced longitudinal follow-ups on patients, collecting thorough data on long-term outcomes and treatment efficacy over time. The strategy will result in a more comprehensive understanding of sepsis management and patient recovery pathways, ultimately leading to better clinical practices and patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Mr. Jayadev Prasad, an IT manager of Sohar Hospital, and all the staff of the microbiology laboratory for their continuous support in data collection and helping us to complete this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, and the work was not supported or funded by any agency.

References

- Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020; 395(10219):200-211. [CrossRef]

- Kim HI, Park S. Sepsis: Early Recognition and Optimized Treatment. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2019;82(1):6-14. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;400(10369):2221-2248. [CrossRef]

- Guarino M, Perna B, Cesaro AE, Maritati M, Spampinato MD, Contini C, ET AL. Update on Sepsis and Septic Shock in Adult Patients: Management in the Emergency Department. J. Clin. Med. 2023; 12:3188. [CrossRef]

- Srzić I, Nesek Adam V, Tunjić Pejak D. SEPSIS DEFINITION: WHAT'S NEW IN THE TREATMENT GUIDELINES. Acta Clin Croat. 2022;61(Suppl 1):67-72. [CrossRef]

- Marik PE, Taeb AM. SIRS, qSOFA and new sepsis definition. J Thorac Dis 2017;9(4):943-945. [CrossRef]

- Bou Chebl R, Tamim H, Abou Dagher G, Sadat M, Ghamdi G, Itani A, et al. Sepsis in end-stage renal disease patients: are they at an increased risk of mortality? Ann Med. 2021;53(1):1737-1743. [CrossRef]

- Himali NA, Abdelrahman A, Suleimani YMA, Balkhair A, Al-Zakwani I. Access- and non-access-related infections among patients receiving haemodialysis: Experience of an academic centre in Oman. IJID Reg. 2023; 7:252-255. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki M, Satoh N, Nakamura M, Horita S, Seki G, Moriya K. Bacteremia in hemodialysis patients. World J Nephrol. 2016;5(6):489–496. [CrossRef]

- Khwannimit B, Bhurayanontachai R. The epidemiology of, and risk factors for, mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock in a tertiary-care university hospital setting. Epidemiology & Infection. 2009; 137(9): 1333-1341. [CrossRef]

- Locham S, Naazie I, Canner J, Siracuse J, Al-Nouri O, Malas M. Incidence and risk factors of sepsis in hemodialysis patients in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(3):1016-1021.e3. [CrossRef]

- Fisher M, Golestaneh L, Allon M, Abreo K, Mokrzycki MH. Prevention of Bloodstream Infections in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(1):132-151. Epub 2019 Dec 5. Erratum in: Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17(4):568-569. [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent JL. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16045. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent JL, Pereira AJ, Gleeson J, Backer D. Early management of sepsis. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2014;1(1):3-7. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan AL, Vanimaya, Ravindran S, Saikant R, Lakshmi S, Kartik R, G M. Procalcitonin: a promising diagnostic marker for sepsis and antibiotic therapy. J Intensive Care. 2017; 5:51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbuTaha SA, Al-Kharraz T, Belkebir S, Abu Taha A, Zyoud SH. Patterns of microbial resistance in bloodstream infections of hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. Sci Rep. 2022 Oct 26;12(1):18003. [CrossRef]

- Rteil A, Kazma JM, El Sawda J, Gharamti A, Koubar SH, Kanafani ZA. Clinical characteristics, risk factors and microbiology of infections in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. J Infect Public Health. 2020 Aug;13(8):1166-1171. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok H, Jeon JH, Park DW. Antimicrobial Therapy and Antimicrobial Stewardship in Sepsis. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(1):19-30. [CrossRef]

- Sakr Y, Jaschinski U, Wittebole X, Szakmany T, Lipman J, Namendys-Silva SA, et al. Sepsis in intensive care unit patients: worldwide data from the intensive care over nations audit. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018; 5: ofy313. [CrossRef]

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181-1247. [CrossRef]

- Komori A, Abe T, Kushimoto S, Ogura H, Shiraishi A, Saitoh D, et al; JAAM FORECAST group. Characteristics and outcomes of bacteremia among ICU-admitted patients with severe sepsis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2983. [CrossRef]

- Gauer R, Forbes D, Boyer N. Sepsis: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(7):409-418.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance CLSI Supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 29th 251 ed. Standards Institute; 2019.

- Powe NR, Jaar B, Furth SL, Hermann J, Briggs W. Septicemia in dialysis patients: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis. Kidney Int. 1999;55(3):1081-90. [CrossRef]

- Can Ö, Bilek G, Sahan S. Risk factors for infection and mortality among hemodialysis patients during COVID-19 pandemic. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54(3):661-669. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi SH, Aftab RA, Chua SS. Risk factors associated with nosocomial infections among end stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234376. [CrossRef]

- Krzanowski M, Janda K, Chowaniec E, Sułowicz W. Hemodialysis vascular access infection and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Przegl Lek. 2011;68(12):1157-61.

- Kim DH, Park JI, Lee JP, Kim YL, Kang SW, Yang CW, et al. The effects of vascular access types on the survival and quality of life and depression in the incident hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2020;42(1):30-39. [CrossRef]

- Vanholder R, Van Biesen W. Incidence of infectious morbidity and mortality in dialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2002;20(5):477-80. [CrossRef]

- Schamroth Pravda M, Maor Y, Brodsky K, Katkov A, Cernes R, Schamroth Pravda N, et al. Blood stream Infections in chronic hemodialysis patients - characteristics and outcomes. BMC Nephrol. 2024;25(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Zilberman-Itskovich S, Elukbi Y, Weinberg Sibony R, Shapiro M, Zelnik Yovel D.; Strulovici, A, et al. The Epidemiology of Multidrug-Resistant Sepsis among Chronic Hemodialysis Patients. Antibiotics 2022; 11:1255. [CrossRef]

- Tanzarella ES, Cutuli SL, Lombardi G, Cammarota F, Caroli A, Franchini E, et al. Antimicrobial De-Escalation in Critically Ill Patients. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(4):375. [CrossRef]

- Ippolito M, Cortegiani A. Empirical decision-making for antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients. BJA Educ. 2023;23(12):480-487. [CrossRef]

- Corona A, De Santis V, Agarossi A, Prete A, Cattaneo D, Tomasini G, et al. Antibiotic Therapy Strategies for Treating Gram-Negative Severe Infections in the Critically Ill: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12(8):1262. [CrossRef]

- Khilnani GC, Zirpe K, Hadda V, Mehta Y, Madan K, Kulkarni A, et al. Guidelines for Antibiotic Prescription in Intensive Care Unit. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine 2019;23(Suppl 1): S1-S63.

- Niederman MS, Baron RM, Bouadma L, Calandra T, Daneman N, DeWaele J, et al. Initial antimicrobial management of sepsis. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):307. [CrossRef]

- Theodoros Tourountzis, Foteini Stasini, Zoi Skarlatou, Athanasios Bikos, Chrysoula Kagiadaki, Konstantinos Sombolos, et al. SURVIVAL AND PREDICTORS OF MORTALITY IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2023;38 (Suppl 1): 4742. [CrossRef]

- Tylicki L, Puchalska-Reglińska E, Tylicki P, Och A, Polewska K, Biedunkiewicz B, et al. Predictors of Mortality in Hemodialyzed Patients after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(2):285. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Ao G, Wang Y, Liu F, Bao M, Gao M, et al. Risk factors for mortality in hemodialysis patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Renal Failure. 2021; 43(1):1394–1407. [CrossRef]

- Bae EH, Kim HY, Kang YU, Kim CS, Ma SK, Kim SW. Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients starting hemodialysis. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2015;34(3):154-9. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

Table 2.

Etiological agents of bloodstream infection.

Table 2.

Etiological agents of bloodstream infection.

Table 3.

Antibiotic susceptibility report of Gram-negative bacteria (GNB).

Table 3.

Antibiotic susceptibility report of Gram-negative bacteria (GNB).

Table 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility report of Gram-positive cocci (GPC).

Table 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility report of Gram-positive cocci (GPC).

Table 5.

Univariate regression analysis of the risk factors for outcome of infection.

Table 5.

Univariate regression analysis of the risk factors for outcome of infection.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).