1. Introduction

In the context of global climate change, the frequency of extreme weather events, including sudden torrential rainfall and flooding, has increased worldwide. As global warming progresses, extreme precipitation events are occurring more frequently [

1]. Consequently, waterlogging stress induced by such events has become one of the major abiotic constraints on crop production [

2].

Wheat is predominantly cultivated in arid to semi-humid regions, particularly in semi-arid environments, and exhibits limited adaptability to humid conditions. Under soil waterlogging, wheat growth and grain yield are markedly reduced. Globally, 15–20% of wheat yield is lost annually due to waterlogging damage, affecting approximately 10–15 million hectares [

3]. In Japan, the risk of waterlogging damage is particularly high because of abundant rainfall and the frequent cultivation of wheat in converted paddy fields characterized by heavy clay soils and poor drainage capacity. As a result, waterlogging has been identified as the primary cause of wheat yield reduction in Japan, making its mitigation a critical agronomic challenge [

4].

Although waterlogging damage can occur at various growth stages in wheat, the flowering stage is especially sensitive [

5,

6,

7]. Waterlogging stress during flowering reduces nitrogen uptake capacity and leaf greenness, as reflected by decreased SPAD values, thereby accelerating premature leaf senescence through chlorosis and necrosis. This process suppresses photosynthesis and leads to poor grain filling [

6,

8]. Grain yield and quality in wheat are strongly influenced by nitrogen redistribution during the grain-filling period [

9,

10]. Waterlogging stress has been shown to inhibit the remobilization of nitrogen and photosynthetic assimilates stored in vegetative organs to the grain, resulting in yield reduction [

11]. Early senescence has been hypothesized to occur via leaf “self- destruction” as a compensatory response to reduced nitrogen uptake capacity [

12,

13]. Therefore, sustaining nitrogen uptake capacity is essential for mitigating premature senescence and yield loss in wheat under waterlogging conditions.

Plants have been reported to possess adaptive mechanisms described as “stress memory”, “stress priming”, “stress hardening”, or “stress imprint”, which enable them to respond more effectively to subsequent stress after prior exposure [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The strategic exploitation of these mechanisms has attracted increasing attention as a potential approach to enhance crop tolerance to abiotic stresses. Waterlogging-related stress memory has been documented in several crop species. In soybean, exposure to water-logging during the vegetative stage reduced oxidative damage and maintained yield when plants were subsequently subjected to waterlogging during the reproductive stage [

19]. Similarly, in tomato, repeated waterlogging treatments applied at the seedling stage maintained photosynthetic capacity compared with non-primed plants [

20].

In wheat, waterlogging stress memory has also been reported. Short-term (two days) waterlogging applied at multiple 7-leaf, 9-leaf, and heading stages enhanced tolerance to subsequent waterlogging at flowering by delaying leaf senescence and maintaining grain filling and yield [

21]. In addition, waterlogging priming at early vegetative stages, such as the 4- and 6-leaf stages, mitigated declines in photosynthetic capacity and grain yield under later waterlogging stress, with clear varietal differences [

22]. Waterlogging priming at the 4-leaf stage has also been shown to increase antioxidant enzyme activity and soluble sugar content, and in tolerant variety, to promote inducible aerenchyma formation, thereby alleviating reductions in SPAD values and grain yield under waterlogging stress [

23].

Despite these advances, previous studies have generally examined waterlogging stress memory at limited growth stages or with a fixed number of treatments. Consequently, the optimal growth stage and frequency of waterlogging stress memory treatments required to maximize waterlogging tolerance in wheat remain unclear. Moreover, although wheat grain yield is closely associated with nitrogen uptake capacity after flowering [

24], the effects of waterlogging stress memory on post-flowering nitrogen uptake and subsequent nitrogen remobilization to grains have not been quantitatively evaluated.

The present study was conducted under controlled pot conditions over two consecutive growing seasons to address these knowledge gaps. Eight treatments were established by combining the presence or absence of waterlogging stress memory at three key growth stages: the tillering, stem elongation, and booting stages. This experimental design enabled a systematic evaluation of both the timing and frequency of stress memory treatments. The objectives of this study were (i) to determine whether waterlogging stress memory mitigates waterlogging damage during flowering, (ii) to identify the growth stage and treatment combination that most effectively enhances waterlogging tolerance, and (iii) to assess the reproducibility of these effects across two growing seasons. In addition, ammonium sulfate labeled with the nitrogen stable isotope (15N) was applied after the removal of waterlogging stress at flowering to quantitatively evaluate the effects of waterlogging stress memory on nitrogen uptake capacity and nitrogen remobilization to grains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation Environments and Waterlogging Stress Memory Treatment

The representative Japanese bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivar Norin 61 was used as the plant material. Pot experiments were conducted in a glasshouse at the Faculty of Agriculture, Tottori University, Japan (134.1705°E, 35.5146°N), over two consecutive growing seasons (2022/23 and 2023/24). The glasshouse allowed control of precipitation, thereby eliminating rainfall effects. To ensure precise application of waterlogging stress at specific growth stages, well-drained sandy soil was used and filled into white HIPS (High Impact Polystyrene) pots (1/2000 a Wagner pot; surface area 500 cm²; inner diameter 25 cm; inner height 30 cm).

In the 2022/23 growing season, basal fertilizers were applied at the following rates: 1.19 g pot⁻¹ (5 g N m⁻²) ammonium sulfate, 3.40 g pot⁻¹ (12 g P₂O₅ m⁻²) superphosphate, 1.20 g pot⁻¹ (12 g K₂O m⁻²) potassium sulfate, and 4.50 g pot⁻¹ of the trace element fertilizer “Hama Green”. On 28 December 2022, six seeds per hill were sown at six equally spaced points arranged in a circle in each pot. Plants were thinned on three occasions to retain three plants per hill (18 plants per pot). On 10 March 2023, ammonium sulfate was applied as a topdressing at 1.19 g pot⁻¹ (5 g N m⁻²). On 13 April 2023, the day after termination of the 5-day waterlogging stress during flowering, 1.20 g pot⁻¹ of ammonium sulfate containing 2.5 atom% 15N was dissolved in tap water and applied evenly around the base of each hill to assess nitrogen uptake capacity after waterlogging stress.

In the 2023/24 growing season, basal fertilizers were applied at 1.19 g pot⁻¹ (5 g N m⁻²) ammonium sulfate, 1.40 g pot⁻¹ (12 g P₂O₅ m⁻²) heavy superphosphate lime, 1.00 g pot⁻¹ (12 g K₂O m⁻²) potassium chloride, and 4.50 g pot⁻¹ “Hama Green”. Seeds were sown on 28 November 2023 as in 2022/23, and plants were thinned to two plants per hill (12 plants per pot). Ammonium sulfate (1.19 g pot⁻¹, equivalent to 5 g N m⁻²) was applied as topdressing on 8 February and again on 11 March 2024. On 16 April 2024, the day after termination of the 4-day waterlogging stress during flowering, 1.20 g pot⁻¹ of ammonium sulfate containing 2.5 atom% 15N was applied to each pot, as in 2022/23.

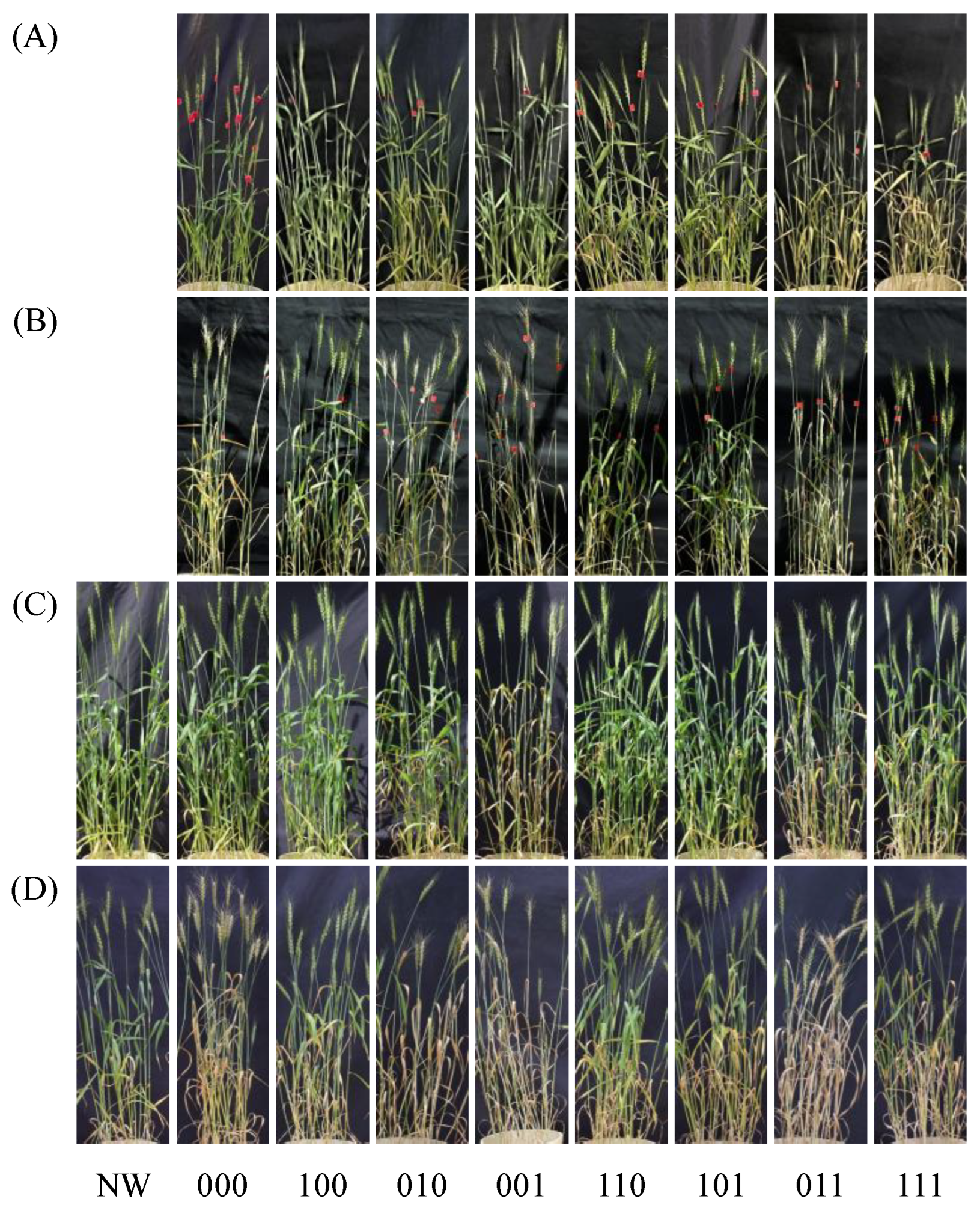

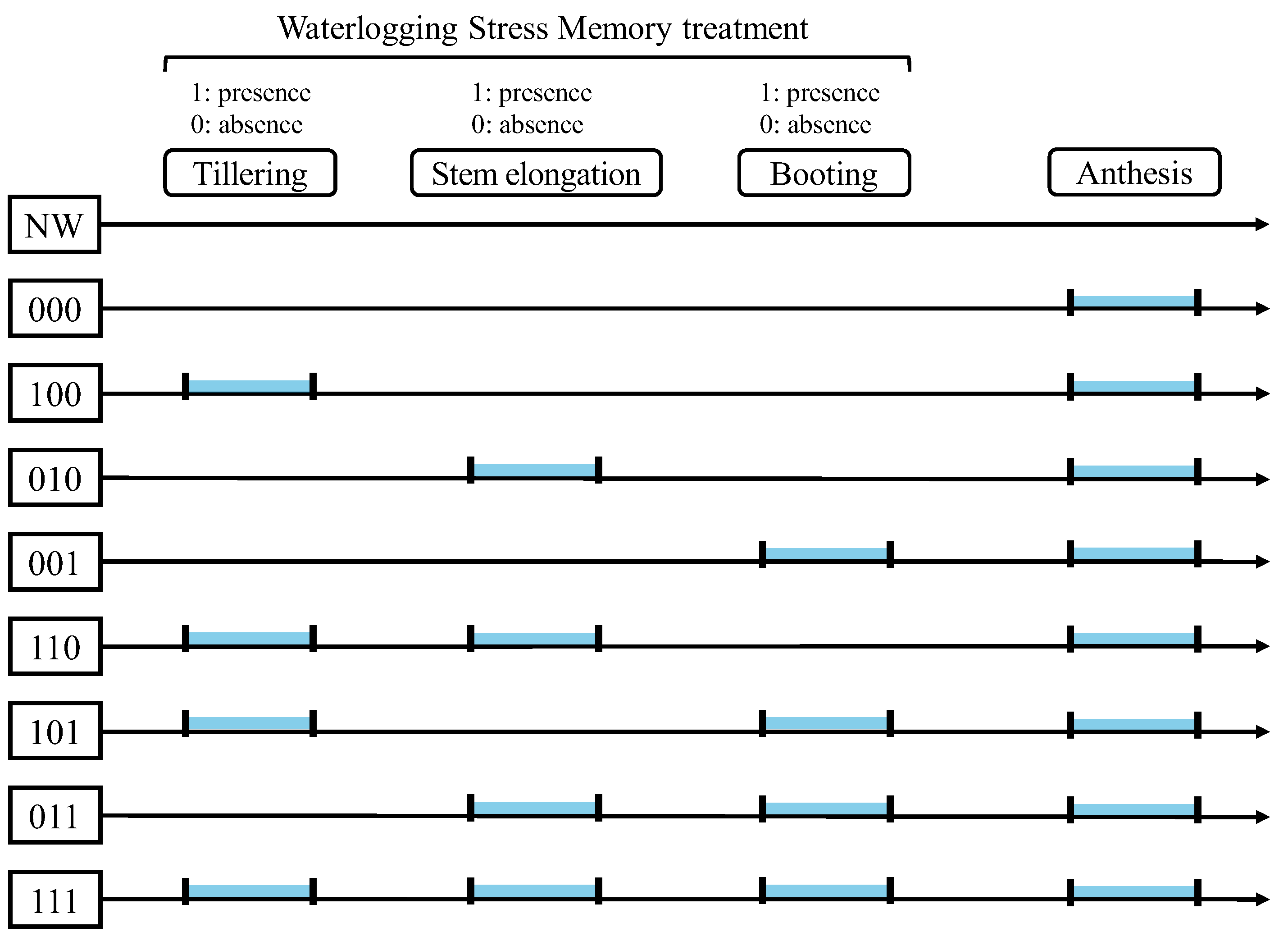

Eight treatments were established by combining the presence (1) or absence (0) of waterlogging stress memory treatments at the tillering, stem elongation, and booting stages (

Figure 1). In the 2023/24 season, a non-waterlogged control that received no waterlogging stress throughout the growing period was also included for physiological evaluation. Except for this control, all treatments were subjected to waterlogging stress during flowering. The experiments were conducted in a randomized block design with five replicates in 2022/23 and six replicates in 2023/24 (treatments 100 and 101 in 2022/23 had four replicates because of poor growth before initiation of the tillering-stage memory treatment).

In 2022/23, waterlogging stress memory treatments were applied for 4 days at the tillering stage (6–10 March 2023), 4 days at the stem elongation stage (20–24 March), and 3 days at the booting stage (27–30 March). All pots were subsequently subjected to 5 days of waterlogging stress during flowering (7–12 April). In 2023/24, treatments were applied for 4 days at the tillering stage (21–25 February 2024), 4 days at the stem elongation stage (6–10 March), and 4 days at the booting stage (22–26 March). During flowering, a 4-day waterlogging stress treatment (11–15 April) was applied to all pots except the non-waterlogged control. For all waterlogging treatments, the water level was maintained approximately 3 cm above the soil surface. After each treatment, water was rapidly drained through the drainage holes at the bottom of the pots, collected separately, and reused for subsequent irrigation to minimize nutrient leaching.

2.2. Measurements and Sampling

SPAD values of the uppermost fully expanded leaf or flag leaf with average leaf color in each pot were measured over time from the initiation of the tillering-stage memory treatment until complete leaf senescence using a portable chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502Plus, Konica Minolta Inc., Japan). Measurements were taken at the distal, medial, and basal regions of each leaf, and the mean of the three readings was used as the representative value.

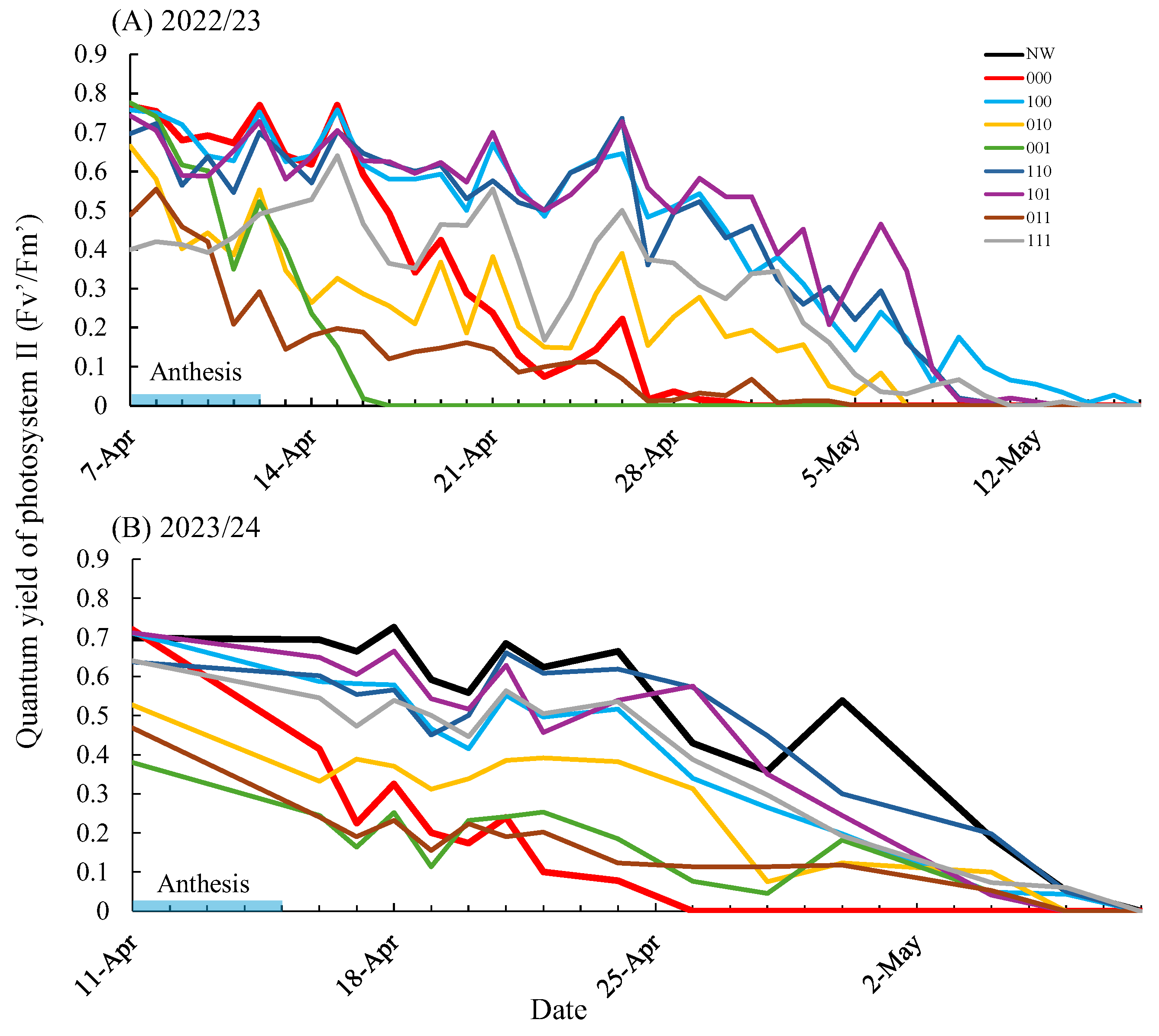

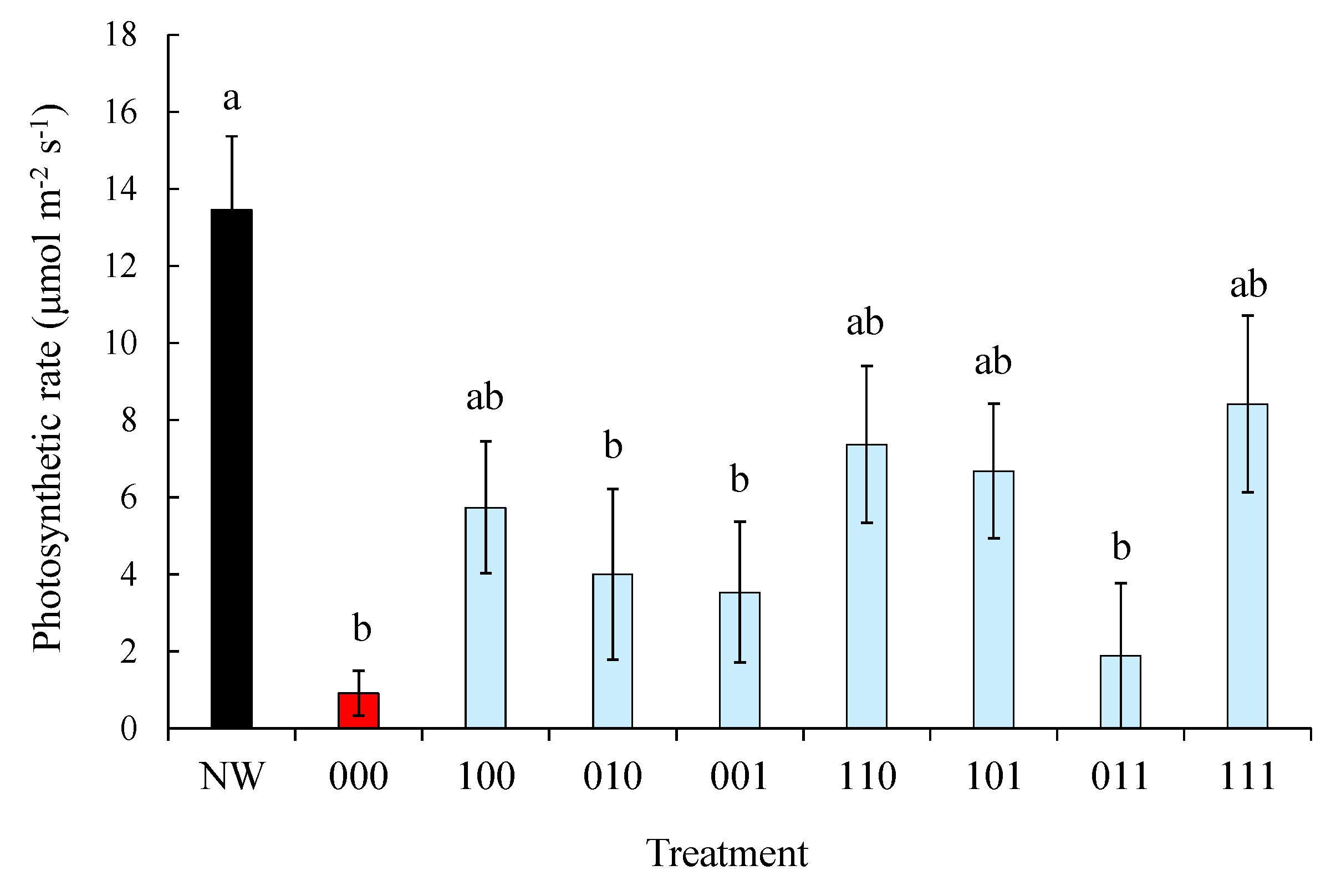

The quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv′/Fm′) was measured from the onset of waterlogging stress during flowering until leaf senescence using a portable chlorophyll fluorometer (PAR E-FP110/S, PSI, Czech Republic). Measurements were conducted under natural light between 08:00 and 12:00 on the middle portion of the flag leaf in each pot. Photosynthetic rate was measured only in the 2023/24 season. On 17 April 2024, measurements were taken from the middle portion of the flag leaf using a photosynthetic rate measurement device (MIC-100, Masa International Corp., Japan).

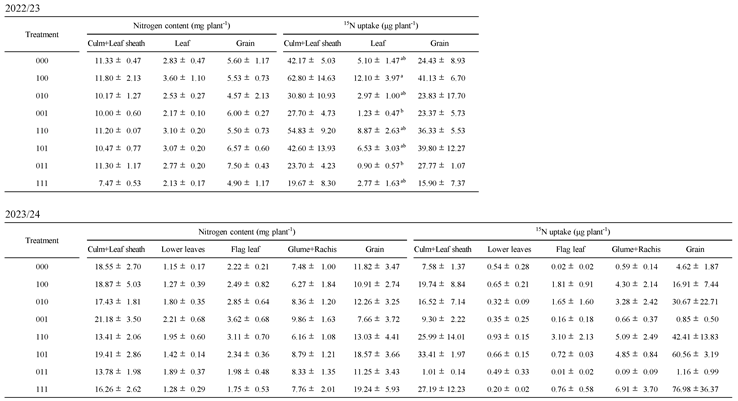

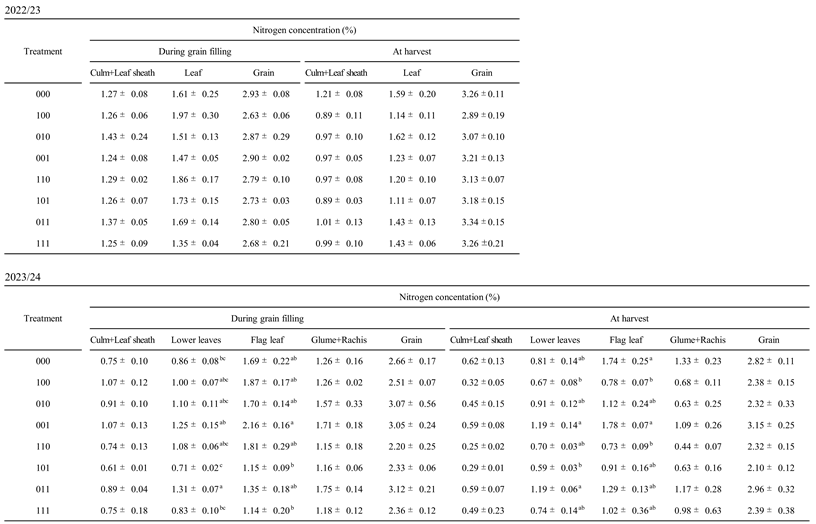

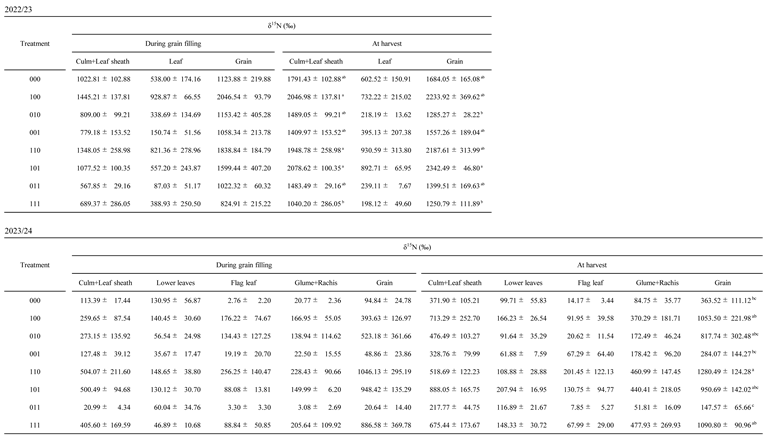

Sampling was conducted twice, during grain filling and at harvest. In 2022/23, three plants from an average hill were sampled from each pot during grain filling on 24 April 2023 (12 days after removal of waterlogging stress during flowering). In 2023/24, sampling was conducted on 25 April 2024 (10 days after stress removal). Samples were oven-dried at 80 °C for 3 days. In 2022/23, culms + leaf sheaths, leaves, and grains were weighed. In 2023/24, culms + leaf sheaths, lower leaves, flag leaf, glumes + rachis, and grains were measured. At maturity, four hills (three and two plants per hill in 2022/23 and 2023/24, respectively) were sampled, air-dried at room temperature. For yield evaluation, two hills with average spike weight were selected from the four hills. In 2022/23, only the main culm was used since less appearance of tillers, whereas in 2023/24 both the main culm and tillers were used to assess grain yield per plant, grain number per spike and thousand-grain weight.

After dry weight determination, dried samples of each component were ground with a pulverizer (WB-1, Osaka Chemical Co. Ltd., Japan) to determine nitrogen concentration (

Table A2) and nitrogen stable isotope composition (δ

15N,

Table A3) . Nitrogen concentration (%) was measured using a C/N analyzer (JM1000CN, J-Science, Japan) and multiplied by dry weight to calculate nitrogen content (mg plant⁻¹). Isotopic composition was determined using a stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA IsoLink CN and DELTA V Advantage, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) after encapsulation of powdered samples in tin cups. Total

15N uptake was calculated by multiplying total nitrogen content by the difference between sample

15N atom% and the natural abundance (0.3663 atom%), following [

25]. The

15N allocation ratio for each component was calculated as the proportion of total aboveground

15N uptake. Nitrogen-related parameters were measured for three replicates with average thousand-grain weight.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 29 (IBM Corp., USA). Differences among treatments were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used for multiple comparisons when significant effects were detected. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess relationships between variables. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify the most effective growth stage and optimal frequency for applying pre-flowering waterlogging stress memory treatments to mitigate waterlogging damage in wheat during flowering, and to clarify the physiological basis of this memory effect with particular emphasis on nitrogen uptake after stress removal. In this context, waterlogging stress memory is defined as the persistent physiological capacity of plants to respond more effectively to subsequent waterlogging stress following an earlier, non-lethal exposure, without implying permanent acclimation or genetic adaptation. In the current study, the use of sandy soil enabled precise and reproducible imposition of waterlogging at defined growth stages, and consistent responses were observed across two consecutive pot experiment seasons.

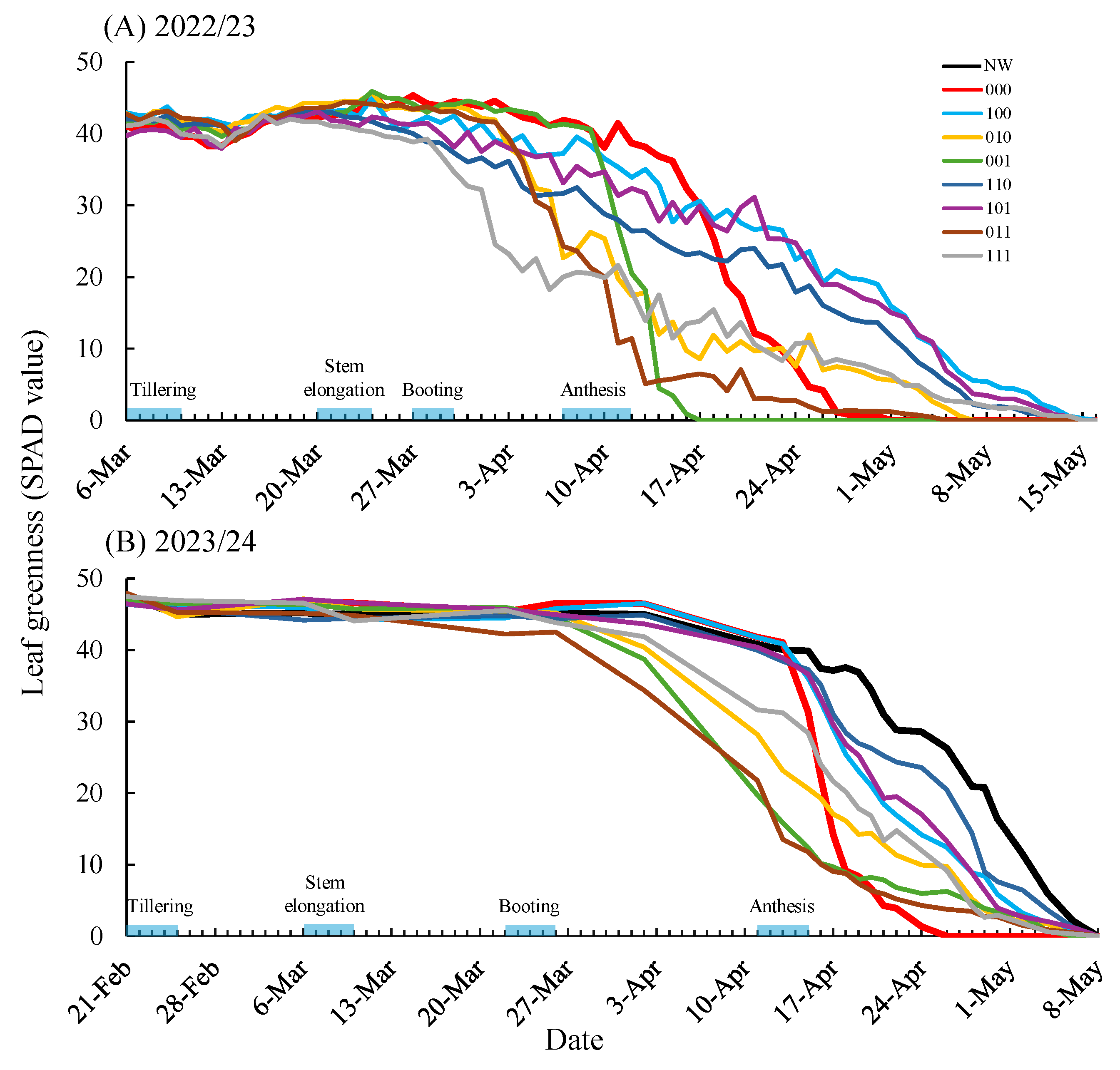

Plants subjected only to waterlogging during flowering (treatment 000) exhibited pronounced declines in SPAD values and accelerated senescence of the flag leaf after stress removal in both seasons (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). This early loss of photosynthetically active leaf area was associated with impaired grain filling, leading to reduced thousand-grain weight and consequently lower grain yield (

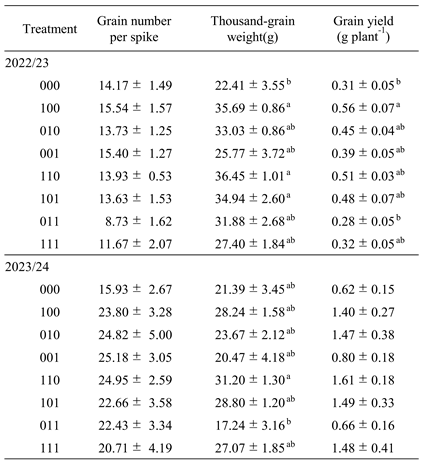

Table 1). These responses are consistent with previous reports indicating that wheat is particularly vulnerable to waterlogging stress during flowering, when premature senescence constrains assimilate supply to developing grains [

6,

7].

In contrast, several treatments receiving waterlogging stress memory prior to flowering, most notably treatment 100, 110, and 101, showed a markedly attenuated decline in SPAD values when exposed to waterlogging at flowering, thereby delaying senescence (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Grain yield responses closely mirrored SPAD trends, with significant yield increases observed in these treatments. In the 2022/23 season, grain yield in treatment 100 was significantly higher than in 000, while in 2023/24, additional treatments (010 and 111) also showed higher yields (

Table 1). Across both seasons increased thousand-grain weight was the most consistent contributor to yield improvement, particularly in treatment 100, 110, and 101. Similar increases in thousand-grain weight following waterlogging stress priming have been reported previously [

21,

22]. Collectively, these results indicate that waterlogging stress memory can alleviate the deterioration of grain filling typically induced by flowering-stage waterlogging.

By comparing eight treatments that combined the presence or absence of water logging stress memory at tillering, stem elongation, and booting stages, this study demonstrated that memory effects were strongest when waterlogging priming was applied during tillering, either alone (treatment 100) or in combination with subsequent stages (treatment 110 and 101). Although the tillering-stage priming in this study corresponded to the 5–6 leaf stage, earlier studies have shown that brief waterlogging at the 4-leaf stage can reduce declines in SPAD values and grain yield under later stress at heading [

23] , and that repeated priming at the 4- and 6-leaf stages can mitigate reductions in photosynthesis and yield under booting-stage waterlogging [

22]. In contrast, treatments primed only at booting (treatment 001 and 011) exhibited accelerated leaf senescence prior to flowering in both seasons (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), with no corresponding increases in thousand-grain weight or yield (

Table 1). While it was reported beneficial effects of repeated waterlogging at multiple later stages, differences in growth stage timing and stress duration likely account for these discrepancies [

20]. Notably, treatment 111, which received priming at all three stages, tended to maintain leaf greenness and grain yield in 2023/24 (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4;

Table 1). Taken together, these findings suggest that exposure to waterlogging stress during tillering is a critical component for establishing an effective stress memory that enhances tolerance from booting through flowering.

Waterlogging stress is known to reduce the quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv’/Fm’) and photosynthetic rate in wheat [

26]. Consistent with this, treatment 000 showed pronounced declines in both parameters (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In contrast, treatments receiving tillering-stage priming (treatment 100, 110, and 101) maintained relatively high Fv’/Fm’ values during flowering-stage waterlogging, paralleling SPAD responses (

Figure 4). Although differences in photosynthetic rate were not statistically significant, primed treatments exhibited values approximately 6–8 times higher than 000 (

Figure 5). In previous studies, it is documented that a modest increase of photosynthetic rate in flowering-stage waterlogging was observed in response to waterlogging stress memory in vegetative stages of wheat [

21]. These results indicate that tillering-stage waterlogging memory contributes to maintaining photosystem II function under subsequent stress, which is consistent with improved grain filling and higher thousand-grain weight.

Previous studies have proposed antioxidant capacity and/or aerenchyma formation as key components of waterlogging stress memory in wheat [

21,

22,

23,

27,

28]. Given that waterlogging after flowering is known to suppress nitrogen uptake [

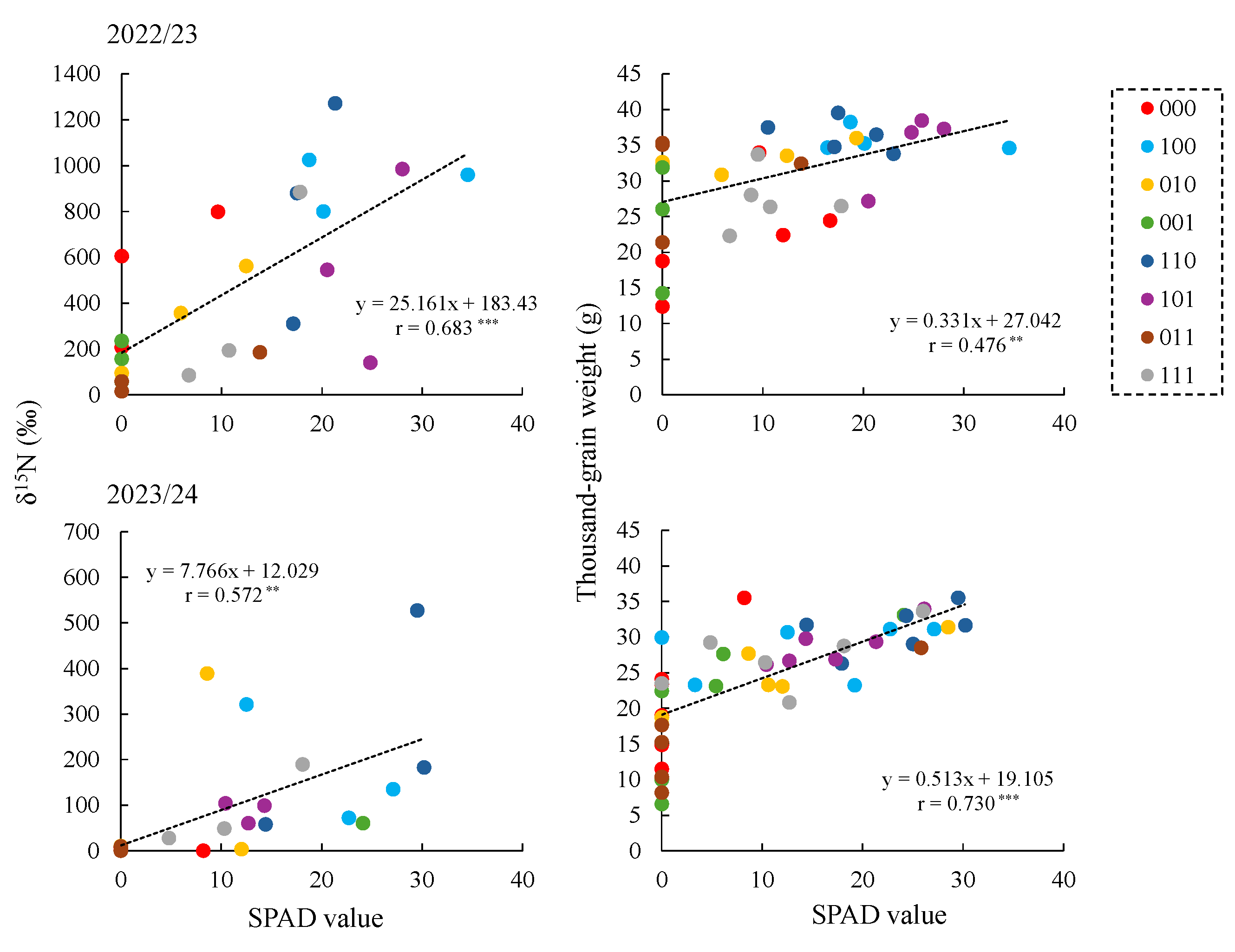

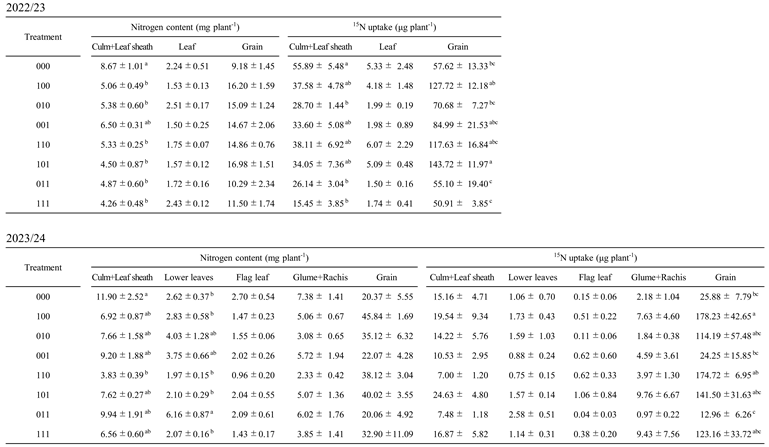

10], this study focused on nitrogen dynamics after stress removal using stable isotope tracers. Treatments primed during tillering (100, 110, and 101) consistently showed higher δ¹⁵N values in multiple organs during grain filling than 000 (

Table A3), indicating greater nitrogen acquisition after flowering-stage waterlogging. Correspondingly, total ¹⁵N uptake, calculated from δ¹⁵N values and dry weight, was higher in these treatments both during grain filling and at harvest (

Table 2 and

Table A1 and

Table A3). These results demonstrate that tillering-stage waterlogging memory allows wheat to sustain nitrogen uptake capacity long after the priming event, even when later exposed to waterlogging at flowering.

The persistence of this effect, observed more than 4–6 weeks after tillering-stage priming, suggests involvement of relatively stable morphological or physiological modifications in the root system. Under waterlogged conditions, wheat roots can form aerenchyma through programmed cell death, facilitating oxygen transport to root tips and supporting root function under hypoxia [

29]. Previous studies have shown that brief waterlogging at early leaf stages can induce aerenchyma formation in wheat, particularly in tolerant varieties [

23]., and that priming accelerates aerenchyma development during subsequent stress events [

27,

28]. While root anatomy was not directly assessed in the present study, the enhanced post-flowering nitrogen uptake and higher SPAD values observed in tillering-primed treatments (

Table 2;

Figure 3) are consistent with improved root function under waterlogging, potentially mediated by such structural adaptations.

Nitrogen demand in wheat grains increases substantially after flowering [

30], yet waterlogging from stem elongation to flowering can impair nitrogen uptake, translocation, and remobilization to grains [

31]. A comparable phenomenon has been documented in the context of maize [

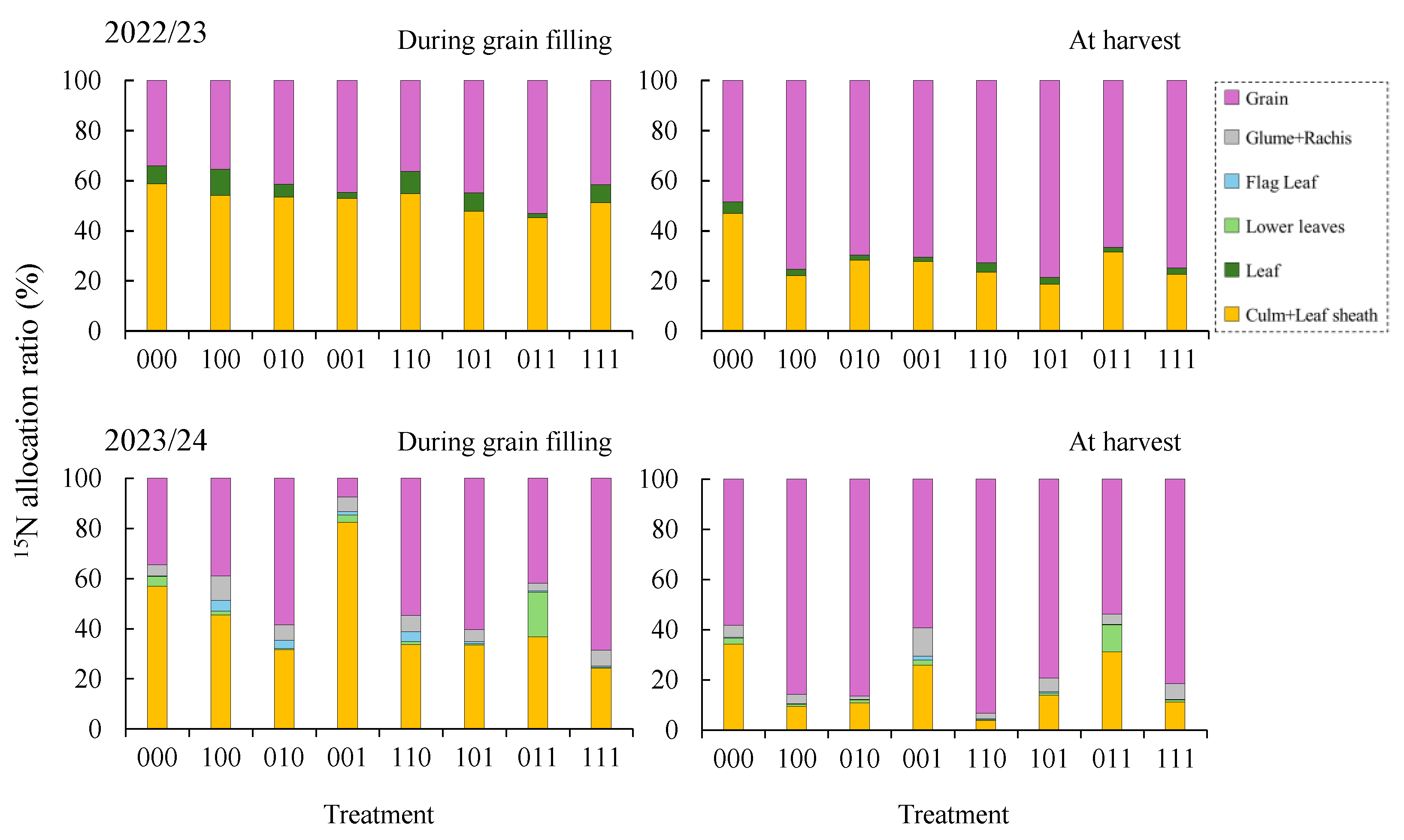

32]. Analysis of ¹⁵N allocation revealed that, although treatment differences were minimal during grain filling in 2022/23, allocation to grains at harvest was consistently lower in 000 than in primed treatments (

Figure 6). In 2023/24, treatments lacking tillering-stage priming (001 and 011) showed little improvement over treatment 000, whereas treatments including tillering priming exhibited higher ¹⁵N allocation to grains. These results indicate that waterlogging stress memory established during tillering contributes not only to sustained nitrogen uptake but also to the maintenance of nitrogen translocation to grains, supporting grain nitrogen accumulation under flowering-stage waterlogging.