Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Inability to Form a Stable Majority Government: High fragmentation often prevents any single party or coalition from securing an absolute legislative majority, leading to government crises, prolonged interregnum periods, and weak, unstable minority governments (Sartori 1976).

- Government Instability: The frequent collapse of minority or unstable coalition governments results in political volatility and repeated elections (Carozzi et al. 2020,Warwick 1994).

- Increased Coalition Bargaining Costs and Policy Incoherence: The difficulty of forming a majority increases negotiation costs, forcing coalitions to adopt incoherent compromises (Sartori 1976).

- Policy Gridlock: The inability to secure a stable majority hampers the passage of substantial, long-term legislation (Lijphart 1999,Tsebelis 2002).

- Reduced Clarity of Political Accountability: Voters struggle to assign responsibility when governments are short-lived or composed of numerous shifting partners (King 1997).

- Necessity of a Self-Contained and Current Argument: While the final scheme presented here closely resembles the latest version Cheng (2025c), the complete and necessary explanations for that scheme are currently scattered across the earlier papers Cheng (2025a, 2025b). This consolidation ensures the reader can access a self-contained, comprehensive understanding without requiring cross-referencing.

- Elimination of Obsolete Material: The developmental process across the earlier papers involved introducing and subsequently discarding several features. Readers referencing the previous work would find it challenging and confusing to determine which explanations and features remain valid and which are now obsolete or superseded by the final scheme.

- Integration of Advanced Refinements: This version introduces a series of final improvements that fundamentally elevate the model’s internal consistency. These innovations refine the executive-legislative interface and administrative continuity mechanisms, ensuring that this consolidated framework possesses a level of theoretical rigour and practical utility far beyond that of its predecessors.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Investiture Rules

2.2. No-Confidence Rules

2.3. Assembly Dissolution Rules

2.4. Presidential Dismissal Rules

3. Scheme C: Background Rules and Framework Articles

3.1. Semi-Presidential Rules

- Asymmetrical Accountability (President and Assembly): The president cannot be removed by the assembly through a vote of no-confidence (only via exceptional procedures like impeachment), while the president retains the conditional power to dissolve the assembly and call for early legislative elections.

- Ministerial Appointments: The president appoints and dismisses ordinary ministers solely on the proposal of the prime minister; no separate parliamentary approval is required for such appointments or dismissals.

- Dual Accountability of the Cabinet: The cabinet (the prime minister and the ministers) is accountable to two separate authorities: primarily the assembly and secondarily the president.

- Independent Tenures within the Executive: The term of the president, the tenure of the prime minister, and the tenure of ordinary ministers are mutually independent.

3.2. Strengthened Presidential Power Rules

- Legislative Veto Power: The president may veto legislation, subject to the usual constitutional override mechanisms. This power, comparable to that exercised by the presidents of Poland, Portugal, and Ukraine, significantly improves the government’s negotiating leverage with parliamentary factions.

- Reserved Domain of Defence and Foreign Affairs: The president retains final authority over the appointment of the Ministers of Defence and Foreign Affairs, as well as the direction of military and foreign policy. This crucial presidential reserved domain, following the well-established French model and practices in several other semi-presidential systems, ensures strategic policy coherence regardless of the domestic political configuration.

3.3. Parliamentary Rules

3.4. Election and Terming Articles

3.4.1. Purposes of Adopting Electoral Concurrency

3.4.2. Note on the Specific Dates

3.4.3. Note on Possible Presidential Run-Off

3.4.4. The Five-Year Term Length

3.5. The Presidential Authority over Prime Minister Provision

4. Scheme C: Main Investiture Articles

4.1. The Core Investiture Article

4.1.1. Full Adherence to the Absolute Majority Principle

- Electoral Mandate: A parliamentary majority signifies the prime minister has majority support among the electorate.

- Effective Governance: A parliamentary majority promises stable support during legislation, which is essential for effective governance.

4.1.2. Disuse of Other Majority Types

- Simple Majority: The simple majority is frequently employed as a fallback mechanism. For instance, in many European countries, if an absolute majority fails to be achieved in the first round of investiture, a simple majority is sought for success in the second round.

- Relative Majority: The relative majority is used in countries where the selection process resembles a presidential election rather than a European-style investiture. For example, in Andorra, Finland, and Japan, the prime minister is effectively elected by achieving the relative majority of the votes cast.

4.1.3. The Challenges of Traditional, Coupled Investiture

- Ambiguity in Responsibility and Delay: Delays can occur on the part of either the head of state or the legislature. Should the process fail before the constitutional deadline, the coupled nature makes it difficult to assign blame and determine which party’s delay caused the failure.

- Potential for Presidential Abuse: The head of state may exploit this power by strategically withholding highly qualified or consensus candidates, instead nominating only his/her personally favoured candidates. While often a mere theoretical possibility in robust parliamentary democracies, this feature has been systematically used for political leverage in some semi-presidential and authoritarian systems.

- Risk of Systemic Failure: Critically, the sequential process lacks a built-in mechanism to guarantee success, leaving open the non-trivial possibility of parliamentary dissolution and resulting in political instability.

4.1.4. Scheme C: Decoupled and Deadlock-Free Process

- Clear Accountability: Neither party can legitimately claim that the other obstructed its nomination process, as both procedures unfold in parallel.

- Guaranteed Candidate Availability (Deadlock-Free): Even if the assembly fails to coalesce around a single nominee, the president’s nomination – being the result of a single-person decision – is always available. A critical advantage of this parallel structure is the virtual impossibility of a complete lack of candidates. Since either party is inherently incentivised to install their preferred candidate, the scenario that both the assembly and the president purposefully delay to the point of deadlock is a mere theoretical possibility.

4.1.5. Why Must the President’s Nomination Precede the Vote?

4.1.6. Thoughtful Candidate Selection

- Legislative Candidate Quality: The internal selection process may involve multiple rounds of voting. Although these preliminary internal votes are not constitutionally recognised as formal confidence votes, they nonetheless reflect the genuine opinion of the assembly members and are thus equally valuable indicators of support. Therefore, even though the constitution does not mandate any voting before the assembly’s final nomination, the resulting candidate is still the product of a deliberate and thoughtful internal process.

- President’s Candidate Quality: Similarly, the president’s candidate is the result of an equally intensive and strategic assessment. The president is strongly incentivised to nominate a highly viable candidate because a poorly chosen nominee would be easily defeated in the subsequent official vote between the two competing candidates.

4.1.7. How Can the Legislative Candidate Lose a Vote Held by the Legislature Itself?

4.1.8. Why No Formal Option of Acceptance?

- Active Functional Acceptance: The assembly may nominate the same candidate proposed by the president. This “matching nomination” serves as a formal signal of inter-branch consensus and moves the process forward immediately, bypassing the need for a separate confidence vote.

- Passive Functional Acceptance: The assembly may choose not to propose a rival candidate. By allowing the constitutional deadline to expire without a counter-nomination, the assembly effectively defaults to the president’s choice. This is a slower path, as the system must wait for the deadline to pass to ensure the assembly’s right to nominate has been fully afforded.

4.1.9. Why not Allow the Assembly to Nominate Multiple Candidates?

- Near Irrelevance of Presidential Nomination: By allowing the assembly to “flood” the process, the president’s nominee is relegated to the end of a long voting queue or rendered redundant if he/she was already included in the assembly’s list. The president’s nomination is nearly irrelevant.

- Redundancy in Cohesive Scenarios: If a cohesive absolute majority exists, the assembly’s primary nominee will inevitably secure confirmation. In this scenario, a multiple-candidate model is superfluous, as it produces the same result as a single-candidate model.

- Instability in Fragmented Scenarios: The only scenario where this model would alter the outcome – which is highly improbable – is if the assembly’s top pick fails, but a “middle-ground” candidate, ranked above the president’s choice, secures a majority. Such a winner would lack the president’s endorsement; he/she was not the president’s choice, but was instead prioritised by the assembly specifically as an alternative. Furthermore, the majority achieved during the vote would likely be temporary and opportunistic, as the candidate had already been defeated in the internal nomination contest by the top-ranked candidate (who failed to secure a majority). Consequently, such a prime minister would face a strained relationship with the president and possess only brittle support from the assembly, making effective governance extremely challenging.

4.1.10. Why Is the Failed Legislative Candidate Still Constitutionally Permitted to Be Appointed?

4.1.11. The Formal Confidence Types

- Type I Confidence (Stronger Mandate): A prime minister obtains type I confidence if he/she was the legislative candidate who faced no competition from a presidential nominee or secured an absolute majority in the confidence vote against the president’s nominee.

- Type II Confidence (Weaker Mandate): A prime minister holds type II confidence if he/she did not meet the type I conditions. This status, while weaker, is still recognised as confidence because the holder was either nominated by the assembly or the assembly’s nominee failed to defeat the holder in the confidence vote.

4.1.12. Rationale for the Scheme Adjustment Regarding Formal Confidence

- Inability Case: The assembly is genuinely unable to find a viable rival candidate.

- Acquiescence Case: The assembly is unwilling to nominate a rival because it agrees with the president’s choice.

- Passive Conduct: Delay its own nomination until the deadline passes (while perhaps still trying desperately to find a viable rival candidate), resulting in the president’s candidate being appointed by default. This action strategically hurts government efficiency.

- Active Conduct: Nominate the president’s candidate itself.

4.1.13. The Double-Relative Deadlines and Their Asymmetry

4.1.14. Conditions Precluding Nomination

- Suspension for Anti-Forestallment: This clause functions as a systemic patch to eliminate a specific procedural bug. While it addresses a much shorter window of only five days and is of much lower practical frequency than the other two conditions, it remains necessary for logical completeness. Its underlying rationale is examined in SubSection 5.2.5.

- Suspension Due to Assembly Dissolution: When the assembly is dissolved, it is unable to perform its function of nomination. To maintain constitutional balance, the president’s right of nomination is symmetrically suspended during this period.

- Suspension Due to Term-End Proximity: This restriction is part of a coordinated framework; Articles C8 and C11, introduced later, contain analogous prohibition clauses. These three rules ensure that the system remains free of cross-term conflicts – such as a candidate nominated by an outgoing president being forced upon an incoming president. These constraints are detailed in SubSection 5.4.3, and their underlying rationales are provided in SubSection 5.4.4.

4.1.15. Why Is There No Mention of a Governmental Programme or Cabinet Composition?

- Policy Transparency: The candidate’s fundamental policy orientations are already well-established and known to the legislature and the nation. A separate, formal programme document is thus considered superfluous.

- Executive Flexibility: The prime minister retains the power to change or reshuffle the cabinet post-investiture, and there is typically no penalty for deviating from a promised composition. Mandating a pre-vote cabinet list provides a false sense of commitment.

- Alignment with Separated Tenure: The scheme upholds the principle that the tenure of individual cabinet members is independent from that of the prime minister. Omitting the requirement for a pre-vote cabinet composition is thus consistent with and reinforces this principle.

4.2. The Caretaker Prime Minister Article

4.2.1. Conversion and Appointment of the Caretaker Prime Minister

- Formalisation of Office Status: The CPM is now defined as a formal “office” rather than a mere “position”. This shift reflects the office’s constitutional weight and its potential multi-month duration during prolonged transition periods, necessitating a stable legal foundation.

- Non-Dismissibility of Converted CPMs: A CPM who attains the office via conversion from an official prime minister is irremovable by the president. The president’s power of dismissal applies exclusively to a CPM whom the president directly appointed. This distinction recognises that a converted CPM retains the residual legitimacy of prior parliamentary vetting, whereas a directly appointed CPM – lacking such a mandate – must remain subject to presidential oversight.

- The “Double Vacancy” Rule: In this latest iteration, the president may appoint a CPM only when both the office of Prime Minister and the office of Caretaker Prime Minister are vacant. This represents a significant departure from previous iterations (Cheng 2025b,Cheng 2025c), where the ability to appoint a CPM without the prior dismissal or vacancy of the incumbent was an intentional feature designed for maximum procedural efficiency. That feature is now discarded, as it contradicts our newly established principle of non-dismissibility for converted CPMs.

- Functioning Assembly Scenario: In the presence of a functioning assembly, the caretaker period is inherently brief; the converted CPM is typically replaced by a new official prime minister within days as the investiture process concludes.

- Dissolved Assembly Scenario: If the assembly is dissolved, the caretaker mandate coincides with the national election cycle. As the converted CPM is invariably his/her party’s campaign leader, he/she operates under intense public scrutiny. In this context, any misconduct would likely contribute to an electoral sanction – the defeat of the CPM’s party at the polls. Thus, political pressure substitutes for the formal power of dismissal.

4.2.2. Powers of the Caretaker Prime Minister

- Dissolution Powers: The CPM should be denied the authority to advise the dissolution of the assembly.

- Legislative Initiative: The authority of a CPM should mirror that of a prime minister operating during a parliamentary dissolution. Under this logic, all powers related to legislative initiative and parliamentary manoeuvre must be removed. By treating the CPM as an executive operating in a “legislative vacuum”, the constitution prevents a temporary steward from enacting permanent policy shifts or altering the political landscape before a new mandate is established. Consequently, the CPM is stripped of the right to introduce new bills or submit legislative proposals.

- Cabinet Personnel Proposals: This iteration of Scheme C stipulates that a CPM’s cabinet proposals are non-binding upon the president. This contrasts with the official prime minister, whose proposals carry binding authority. However, we recommend that the presidential discretion exercised here is strictly veto-based (reactive) discretion; the president may veto or delay a proposal but cannot seize the initiative to appoint a minister of his/her own choosing. This remains distinct from the president’s reserved domain (e.g., Defence or Foreign Affairs), where the president retains unilateral discretion and the power of initiative regardless of whether he/she is working with an official or caretaker prime minister.

- Miscellaneous and Country-Specific Authorities: Powers involving emergency handling, ceremonial duties, the signing of routine executive orders, or specific regulatory oversight should be generally retained unless they intersect with sensitive political reforms. As these often vary by jurisdiction, they are not analysed in detail here but should be subjected to an “incompatibility audit” during national constitutional drafting.

4.3. The Composition of Cabinet Article

- Strict Separation: Borrowed from presidential systems (zero overlap).

- Uncapped Overlap: Borrowed from parliamentary systems (full overlap).

- Seat Retention: The minister retains his/her legislative seat and voting rights while serving in the cabinet.

- Seat Suspension with Substitute: The minister’s legislative functions are suspended for the duration of his/her cabinet tenure, with his/her seat temporarily filled by a substitute.

- Seat Suspension without Substitute: The minister’s seat is suspended without a substitute, effectively leaving the seat empty while he/she serves in the cabinet.

5. Scheme C: Complementary Articles

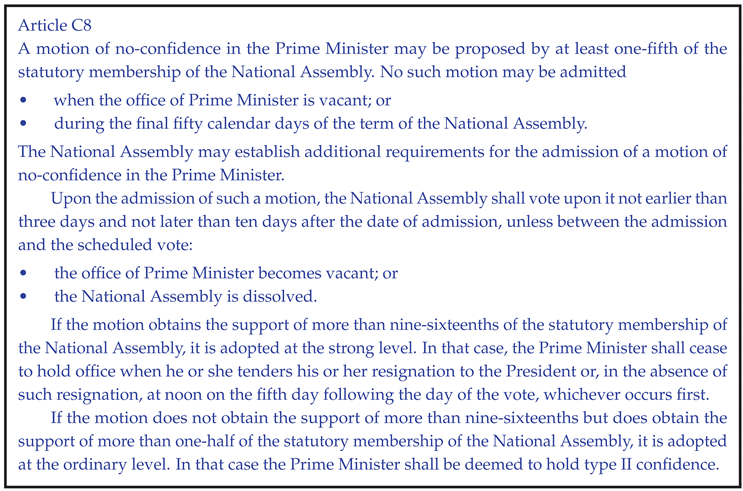

5.1. The No-Confidence Article

5.1.1. Note on Safeguards against Frivolous Motions

5.1.2. Why Two Levels of Adoption?

5.1.3. Choice of the Threshold for Removal

5.1.4. Why Grant the Ousted Prime Minister Four Days to Vacate Office?

5.1.5. Argument Against Stand-Alone Confidence Votes

- Institutional Friction: Seeking a shield against dismissal appears as an attempt to “break free from presidential shackles”, which would poison the working relationship between the two leaders.

- Different Standards: An investiture vote is essentially a comparison between two candidates, whereas a prime-minister-initiated confidence vote is an absolute judgment on one individual involving no comparison. Their standards for passage are conceptually different; consequently, the result of the latter is not sufficiently convincing.

- Structural Redundancy: If a prime minister commands the absolute majority required to win a confidence vote, should the president exercise the dismissal power, that same majority can simply reinstall him/her with type I confidence that shields him/her from further dismissal. That makes a preemptive shield appear unnecessary.

- Difficulty of Avoiding Abuse: The failure of a confidence motion does not constitute a no-confidence at either level; therefore, a prime minister incurs no loss regardless of the outcome. We believe it difficult (if not impossible) to design an effective and elegant penalty mechanism for such motions. Substantive waste of parliamentary resources may be expected if such motions are institutionally facilitated.

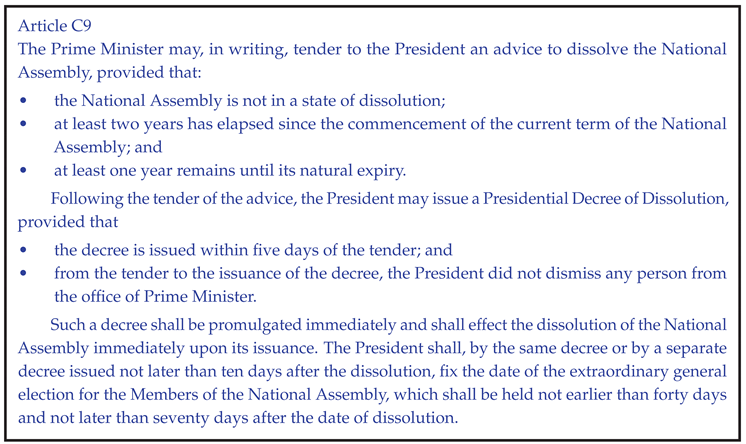

5.2. The Executive Dissolution Article

5.2.1. Contingent, Flexible-Timing Midterm Elections

5.2.2. Prime-Ministerial Initiative Subject to Presidential Discretion

5.2.3. Concern Over the Assembly’s Average Actual Term Length

- Comparative Frequency (The US Example): Even in the event of one snap election during a single five-year term, the average interval between elections would be years, meaning that elections are still less frequent than the regular biennial elections for the U.S. House of Representatives.

- Political Deterrent of Accountability: Any prime minister who advises dissolution on insufficient or partisan grounds will face intense political fallout, resulting in strong disapproval from the deputies and severely damaging his/her chances of reelection as prime minister. This heavy political cost, driven by the need for accountability and institutional stability, constitutes a powerful and self-enforcing deterrent against abusive or premature dissolutions.

5.2.4. Evolution of the Protection Mechanism for the Prime Minister Initiating Dissolution

5.2.5. Rationale for the Anti-Forestallment Clause on Nomination (Article C5)

- Scenario 1: The prime minister tenders an advice for dissolution, but then immediately resigns. The president quickly nominate a favoured candidate for prime minister, and then proceed to grant the dissolution.

- Scenario 2: A motion of no-confidence is adopted at the strong level and the prime minister tenders an advice for dissolution. After the prime minister is officially removed from office but before the five-day period expires, the president could preemptively nominate a candidate for prime minister and then grant the dissolution.

5.2.6. The Caretaker Role: Westminster Conventions vs. Scheme C Codification

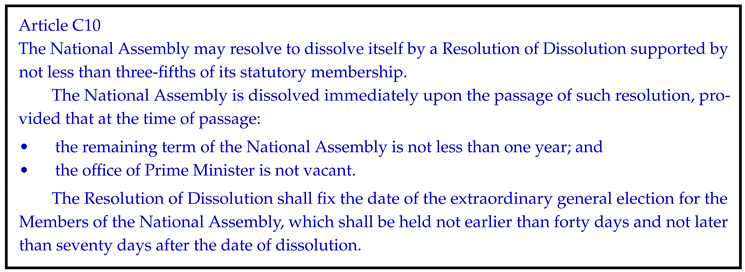

5.3. The Self-Dissolution Article

- No Minimum Service Requirement: The restriction that the assembly must have served at least two years is not present in this article. This allows for an election in the rare event of a profound national crisis occurring early in the assembly’s term, ensuring that a necessary electoral mandate is constitutionally permissible.

- Retention of Remaining Term Restriction: The restriction that the assembly must have at least one year remaining in its term is retained. This is because an early election is unwarranted if the ordinary general election is already imminent. While the one-year benchmark provides strong justification, drafters retain the flexibility to adjust this length (e.g., to six months) if deemed appropriate for the specific political cycle.

- The Occupied PM-Office Condition: The requirement that the office of Prime Minister be filled ensures the assembly has no pending nominations or outstanding confidence votes at the time of its dissolution, and closes any loophole that would allow the president to unilaterally change the prime minister. By guaranteeing executive continuity, this condition eliminates the need for a complex “buffer period” legislative session. Because Scheme C facilitates a failproof appointment process regardless of parliamentary fragmentation, this requirement poses no practical hurdle to dissolution. Politically, it secures the state against a leadership vacuum during the extraordinary election cycle.

- Safety Mechanism: To prevent misuse of this power, a 3/5 majority is required for the dissolution resolution. This threshold aligns with contemporary constitutional precedents, which utilise varying thresholds for self-dissolution: from an absolute majority (1/2) in Austria, Croatia, and Israel, to a 3/5 majority in Turkey, and a 2/3 majority in Poland. We tentatively adopt the 3/5 threshold as a balanced safeguard. While a 60% majority may appear attainable in theory, it represents a formidable barrier in practice. First, an assembly necessitating dissolution is, by definition, deeply fragmented. Second, since a premature dissolution terminates the legislators’ own mandates, securing a supermajority for an act that so directly contradicts their personal and professional self-interest is inherently difficult. This requirement ensures that such an extreme measure is invoked only when a broad cross-party consensus concludes that the legislature has become fundamentally dysfunctional.

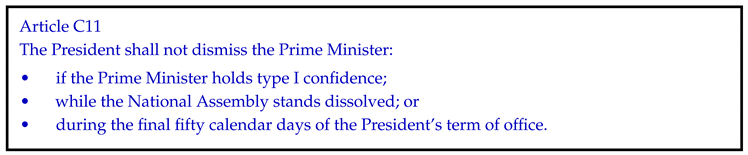

5.4. The Dismissal-Disabling Article

5.4.1. Rationale for Presidential Dismissal Power

5.4.2. Rationale for Disabling Dismissal During the Dissolution Period

- Preventing Institutional Weakening: Dismissing the prime minister – thereby relegating him/her to caretaker status – undermines his/her authority at the exact moment he/she must lead a campaign. Such an act by the president would weaken the prime minister’s standing and could directly contribute to his/her electoral defeat.

- Maintaining Parliamentary Focus: The focus of this period should remain squarely on political parties competing for legislative seats. It should not be distracted by a presidential presence in the government or executive restructuring. Disabling the dismissal power aligns with this objective.

5.4.3. Prime-Ministerial Freeze Near End-of-Term

- Article C5 prohibits the nomination of a prime minister during the final calendar days of the president’s term.

- Article C11 prohibits the dismissal of the prime minister during the final calendar days of the president’s term.

- Article C8 prohibits the admission of a no-confidence motion during the final calendar days of the assembly’s term.

- Shortest Tenure Scenario: The president nominates a candidate on day -51. If the assembly were to respond, it would have to do so also on day -51, because of the freeze beginning at day -50 (00:00), but being totally unprepared, it gives up. The 14-day waiting period expires at day -36 (00:00), triggering the appointment. This results in a tenure of 21.5 days and an Unfrozen Nomination Time of 0 days, as the entire window elapsed during the freeze.

- Longest Tenure Scenario: The president nominates a candidate on day -64. Suppose the assembly requires the full 14 days to complete a nomination, but the freeze begins at day -50 (00:00), giving it only 13 days of functional time. Sidelined by the freeze before it can finish, the assembly cannot nominate. The waiting period expires at day -49 (00:00), triggering the appointment. This results in a tenure of 34.5 days and an Unfrozen Nomination Time of 13 days.

5.4.4. Rationale for the End-of-Term Freeze

- A second nomination occurs on day .

- The confidence vote occurs on day .

- The final appointment occurs on day .

5.4.5. Preserving the Integrity of the Dismissal Mechanism

5.5. The Prime-Ministerial Resignation Article

5.5.1. Rationale for Prime-Ministerial Resignation

5.5.2. The Optimality of End-of-Term Resignation Coupled with Electoral Synchronisation

5.5.3. Prime-Ministerial Transition Following an Ordinary General Election

6. Comparative Studies

6.1. Comparison Between the Latest Scheme C and Its Previous Version

6.2. Comparison Between Scheme C and French Fifth Republic over Presidential Authority

7. Conclusions

- The Game-Based Investiture Rule: As the centrepiece of this model, the game-based investiture rule eliminates the chronic deadlocks and premature dissolutions that plague traditional parliamentarism. Under this rule, the assembly and the president may each nominate a candidate. If the nominations coincide, the appointment is immediate. In the event of a split, the assembly’s nominee undergoes a confidence vote; an absolute majority secures his/her appointment. Should the candidate fail to secure this majority, the president is empowered to appoint either nominee. This “game” ensures a guaranteed outcome, incentivises the nomination of consensus-builders, and assigns the prime minister an initial confidence status from the outset.

- Formal Confidence Types: Crucial to this scheme is a formal categorisation of the prime minister’s status: type I confidence (signifying majority support) or type II confidence (lacking a formal majority). The prime minister’s initial status is assigned as a direct result of the investiture process. However, this status is not invariable; a vote of no-confidence may change it. Specifically, a no-confidence motion can lead to three distinct outcomes: “strong adoption” (triggering immediate removal), “ordinary adoption” (reclassifying the executive as type II), or “no-adoption”. This design protects the continuity of minority governments and prevents administrative collapse while preserving the legislature’s ultimate right to withdraw support.

- Synchronised Electoral Rhythm and Westminster-Style Dissolution: The system adopts a synchronised, periodic schedule for presidential and legislative elections to minimise conflicting legitimacy claims. This is paired with a Westminster-style dissolution mechanism: the prime minister holds the initiative to request dissolution, and the president retains discretionary authority to grant or withhold it. This requirement ensures that cohesive assemblies remain protected from arbitrary dismissal. When combined with specific time-window requirements, the result is a system of contingent, quasi-midterm elections that mirror the mid-cycle electoral check found in American-style presidential systems.

- The Coherent Tenure System: A prime minister’s term begins at investiture and terminates mandatorily at the first sitting of a newly elected assembly. Between these points, tenure is inextricably linked to confidence status: the assembly may oust a prime minister via “strong adoption”, while the president’s dismissal power is restricted to those holding type II confidence. Crucially, the passage of a vote of no-confidence via ordinary adoption transitions the prime minister to this type II status, enabling the president to effect an immediate dismissal. To ensure procedural rigour, these powers are suspended during a “freeze period” late in the presidential term.

-

A Brand-New Caretaker Office: Under Scheme C, the Caretaker Premiership is reimagined as a distinct constitutional office – a hybrid construct that synthesises the Westminster-style Caretaker with the presidential-style Acting Prime Minister. The nature of the office depends on the “mode” of entry:

- -

- The Westminster-Style “Converted” Caretaker: When a prime minister departs office but is still qualified for caretaking, he/she is automatically converted into a caretaker and enjoys non-dismissibility. Like the Westminster model, this ensures continuity of government and secures the individual’s role as the primary campaigner, though his/her authority is recalibrated to be non-binding to reflect the status downgrade and the temporary nature of the office.

- -

- The Presidential-Style “Appointed” Acting PM: In scenarios where a vacancy cannot be filled by conversion, the president appoints a caretaker. This reflects a presidential logic, where the appointee functions effectively as an acting prime minister, being appointed and dismissed at the president’s full discretion.

This “Brand-New Office” thus serves as a flexible stabiliser: it protects the political mandate of an existing leader while providing the president with an appointive “safety valve” to ensure the state remains functional.

References

- Carozzi, Felipe, Davide Cipullo, and Luca Repetto. 2020. Divided they fall: Fragmented parliaments and government stability. CESifo Working Paper Series (8548). [Google Scholar]

- Cheibub, José José. 2007. Presidentialism, Parliamentarism and Democracy . In Especially Chapter 5 on minority governments and parliamentary systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Yiping. 2025a. A game-based scheme for prime minister approval in Korea-like presidential systems. Preprint, Preprints.org. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Yiping. 2025b. Game-based schemes for prime minister selection in multi-party semi-presidential systems. Preprint, Preprints.org. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Yiping. 2025c. Bolstering prime-ministerial countercheck: A new game-based investiture scheme for semi-presidential systems. Preprint, Preprints.org. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duverger, Maurice. 1980. A new political system model: Semi-presidential government. European Journal of Political Research 8, 2: 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgie, Robert. 2011. Semi-Presidentialism: Sub-Types and Democratic Performance. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Anthony. 1997. The British Constitution Often cited in this context for its clarity-of-accountability arguments, contrasting with fragmentation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, Arend. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parliaments and Government Formation: Unpacking Investiture Rules. 2015. Rasch, Bjørn Erik, Shane Martin, and José Antonio Cheibub, eds. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shugart, Matthew Soberg. 2005. Semi-presidential systems: Dual executive and mixed authority patterns. French Politics 3, 3: 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugart, Matthew Soberg, and John M. Carey. 1992. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsebelis, George. 2002. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, Paul V. 1994. Government Survival in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Art. Latest | Art. Previous | Refinements |

| Background Rules | NA | NA | Mandates that the prime minister’s cabinet proposals be binding, excluding the reserved domain. |

| Elections and Terming | Articles C1–C3 | Articles C4–C6 | Enhances rigour by defining dissolution as mandate-terminating. |

| Presidential Authority | Provision C4 | Provision C9 | None |

| Investiture (Vacancy) | Article C5 | Article C1 | Fixes confidence assignment bug; standardises “type I” and “type II” nomenclature; increases post-nomination interval. |

| Caretaker PM | Article C6 | Article C2 | Establishes office status for caretaker and automatic conversion to caretaker status on PM’s removal; reintroduces double-vacancy as prerequisite for appointment; disables further presidential dismissal of converted caretaker PMs; disables caretaker PM’s legislative participation; downgrades caretaker PM’s cabinet proposals to non-binding. |

| Composition of Cabinet | Article C7 | Article C3 | Transitions to a proportional ceiling for ministerial appointments; exempts the prime minister from the headcount to ensure leadership flexibility. |

| Vote of No-Confidence | Article C8 | Article C7 | Restricts motions to occupied offices; coordinates scattered end-of-term freezes into a unified 50-day window to ensure procedural rigour. |

| Executive Dissolution | Article C9 | Article C8 | Deletes redundant caretaker PM protection clauses, relying on Article C6’s immunity of dismissal for converted caretaker PMs; prevents redundant dissolution orders when the assembly is already dissolved. |

| Self-Dissolution | Article C10 | None | Introduces a safety valve for national crises. |

| Dismissal-Disabling | Article C11 | Article C10 | Deletes redundant caretaker PM protection clauses, relying on Article C6’s immunity of dismissal for converted caretaker PMs. |

| PM Resignation | Article C12 | Article C11 | None |

| Feature | Scheme C (Latest) | French Fifth Republic |

| Appointment of PM | Acts only as a secondary tie-breaker in fragmented parliaments; possesses no primary selection initiative. | Exercises significant unilateral discretion (Art. 8); typically selects the PM, though usually guided by parliamentary majorities. |

| Dismissal of PM | Holds formal dismissal authority, but cannot exercise it if the PM retains majority confidence, if parliament is dissolved, or during end-of-term freezes. | Possesses no formal dismissal authority, but obtains the same result de facto by requesting resignations (extending Art. 8). |

| Cabinet Appointments | Must accept binding PM proposals outside the reserved domain; retains full discretion within the reserved domain. | Shares selection discretion with the PM; retains full discretion within the reserved domain. |

| Dissolution | Acts purely reactively; only upon the formal advice of the prime minister, and may do so at most once per five-year term. No trigger is required. | Exercises broad discretionary power (Art. 12); may dissolve the assembly once per year. No trigger is required. |

| Emergency Powers | Possesses no authority to suspend constitutional rules, as such design is inconsistent with the spirit of Scheme C. | Assumes near-absolute authority during crises via Art. 16, centralising all state power in the person of the president. |

| Legislative Role | Exercises a formal veto subject to override; may be granted additional influence measures by country-specific constitutional or statutory provisions. | Dominates the process via Art. 49.3, allowing the president’s government to bypass votes unless the assembly passes a censure motion. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).