1. Introduction

Political fragmentation [

1] in Africa is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon characterized by the division of states into multiple political entities, often marked by ethnic, religious, regional, or ideological groups. While fragmentation remains moderate in Anglophone and Lusophone countries, it is more pronounced in Francophone countries, where a multitude of political parties intend to one day attain power. For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) holds the record among African countries in terms of the number of political parties, with a total of 910 according to the list of authorized political parties [

2] operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo as of June 2023. However, some of these parties, although officially registered, lack significant presence or influence at the national level. While the multiplicity of parties is often seen as a sign of democracy, it leads to a dispersion of votes and difficulty in forming coherent majorities [

3,

4,

5]. African political parties are generally fragile, with weak structures and programs, not representing mass movements, and suffering from a lack of stable organization as well as committed activists [

6]. Moreover, many parties lack clear programs and are often centered around personalities rather than ideologies or public policies [

7]. Bratton and van de Walle [

8] emphasize that many parties in Africa are centered on personalities rather than ideologies, which limits their ability to effectively represent citizens. This situation weakens the capacity of states to address the needs of the population and implement structural reforms. Consequently, this excessive fragmentation of political parties in Africa is an obstacle to effective governance and political stability.

A limited and reasonable number of parties leads to a highly institutionalized system, promoting political stability and democratic development [

9]. Institutionalization involves strong organizational structures, clear ideologies, and a consistent presence in the political arena, thereby contributing to the stability of the democratic process. A trivial approach to reduce the fragmentation of political systems would be to encourage their regrouping by regions or the geographical areas they represent or their ideologies [

10]. In countries with strong regional divisions, parties could form regional coalitions rather than maintaining separate structures. This would reduce the number of parties while ensuring balanced regional representation. Additionally, requiring a significant presence in multiple regions for national recognition would prevent the creation of

"Shop" parties representing only local or personal interests [

11]. However, reducing the number of parties requires a robust methodological framework to quantify political fragmentation.

The

effective number of parties (ENP) index, introduced by Laakso and Taagepera [

12], has been a cornerstone in political science for measuring party system fragmentation. However, it faces several limitations, including exaggerated maximum fragmentation, inability to distinguish absolute dominance, sensitivity to small parties, and lack of ideological consideration. These shortcomings have led to a various alternatives and modifications to the original ENP formula. Many works [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] in this field has focused on refining the concept of ENP index and its calculation methods. They have emphasized the need to consider factors beyond votes and seats, such as legislative power, cabinet positions, and ideological similarities between parties. Some researchers have proposed new interpretations of the ENP, like Caulier’s[

16] statistical framework linking it to party sizes through size-biased sampling. Others, like Grofman and Kline [

17], have introduced measures to account for ideological groupings. Notable contributions to enhance ENP index include Golosov’s [

19] new approach for fragmented and concentrated systems, Borooah’s [

20] generalized entropy inequality indices, and Taagepera’s

Seat Product Model [

21]. Despite these advancements, debates continue on how to best represent party relevance and system fragmentation, particularly in single-party majority situations and highly fragmented systems.

Focusing solely on electoral systems can overlook other influential factors like social cleavages or political culture, while measures tailored to single-party majority situations may be less relevant in fragmented systems [

22]. Moreover, no single index can fully encapsulate the intricacies of party systems, as the most suitable measure often hinges on specific research objectives, data accessibility, and contextual factors [

22,

23]. Researchers must consider whether their focus lies in analyzing bargaining power, vote distribution, or ideological diversity [

23]. Additionally, the availability and reliability of data on coalition behavior, legislative influence, or ideological groupings play a crucial role in determining the most appropriate index [

22,

24]. Given these complexities, recent methods frequently employ multiple variants of the ENP index, including those based on votes, seats, and legislative power, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of party systems [

22]. The political landscape, such as the degree of fragmentation, the maturity of democratic institutions, and the governmental structure, further influences the choice of measurement tool[

23].

In many African countries, the conventional ENP models struggle to capture the nuanced realities of party systems [

25]. Traditional measures like the Laakso–Taagepera index rely heavily on stable vote or seat shares, yet many African electoral environments are characterized by fluid party affiliations, shifting alliances, and even electoral irregularities. The political dynamics in these contexts often feature dominant parties that, while numerically few, exert disproportionate control through patronage networks and clientelist practices that these indices do not capture [

3,

6,

11]. Moreover, electoral systems in Africa can be hybrid or evolving, leading to volatile outcomes that static models cannot accurately represent. Ethnic diversity and regional disparities further complicate the picture, as ENP models [

16] may not capture the ethnic and regional cleavages that significantly influence political fragmentation in Africa. Moreover, the diverse electoral systems and regulatory frameworks for political parties can lead to unique party system dynamics that are not captured by models developed for different contexts. As example, since May 2020, Benin has reduced its political parties from over a hundred to thirteen (13) where existing models fails to capture. Furthermore, more advanced models that incorporate legislative power, ideological dimensions, or entropy-based measures face significant challenges in African settings. These approaches typically require detailed, reliable data on legislative behavior, coalition agreements, or voter distribution—data [

15] that are often scarce or inconsistent in many African countries. Additionally, the underlying assumptions of stability and rational party competition in these models frequently do not hold in contexts where political identities and alliances are highly dynamic and influenced by non-institutional factors. As a result, the existing methods often fail to reflect the true complexity of party systems in Africa, necessitating the development of new, context-sensitive measurement tools [

25]. Furthermore, these limitations underscore the need for more adaptable and integrated measures of ENP that can capture the complexity of political party systems across various contexts, especially in Africa.

To address these limitations, in this paper, we come up two innovative and alternative formulas for calculating the effective number of parties that are better suited to the realities of African political landscapes. These formulas are apolitical, meaning they do not depend on bargaining power, vote or seat distributions, and ideological diversity. Instead, our models focus solely on geographical and demographic dimensions, integrating local realities such as population size and land area to streamline the analysis of political landscapes. Designed to be both simple and effective, these models also incorporate a minimum threshold of two parties, reflecting the universal political reality, even in the least competitive environments. This approach represents a significant advancement over existing methodologies, offering a more nuanced and contextually relevant framework for understanding political dynamics. Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

We introduce for the first time "apolitical" mathematical models, allowing to meaningfully calculate the effective number of political parties, especially adapted to the African context.

Unlike approaches focused exclusively on institutions or electoral behaviors, our model directly integrates the combined effect of a country’s demography and geography.

Our approaches, which are simple, universal and pragmatic, relies solely on local realities while ensuring a viable democratic principle, which makes it a valuable solution in the absence or insufficiency of institutional data.

We propose a flexible and adaptable model, capable of reflecting varied contexts, such as large countries with low populations or small countries with high populations.

Finally, although designed for the African context, our models are easily extensible to other regions of the world, offering a universal tool to analyze and rationalize political systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on metrics for measuring the effective number of political parties. In

Section 3, we introduce our models and present the framework for estimating the effective number of political parties.

Section 4 details our experimental study, evaluates the performance of our methods, and presents results from applying them to African countries. Finally,

Section 5 concludes our work and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review on Effective Number of Parties Models

The concept of the effective number of parties [

12], introduced by Laakso and Taagepera in 1979, aims to quantify the number of competitive parties in an electoral system by considering their relative weight, that is, based on the proportion of seats or votes obtained by political parties. The formula is as follows:

where

represents the proportion of seats or votes obtained by the

i-th party and n is the number of parties.

Despite its widespread adoption, critiques soon emerged regarding its underlying assumptions and its applicability to various contexts—particularly in highly fragmented or very concentrated party systems. Several approaches have sought to generalize or formalize ENP using new equations and entropy-based models. Borooah et al [

20,

25] introduced a general measure using generalized entropy inequality indices, thereby encompassing existing measures (including Laakso–Taagepera) and allowing aggregation at the national level. This approach underscores how subjective considerations (e.g., which dimension of "effectiveness" one emphasizes) can substantially alter ENP values. similary, Bhattacharya and Smarandache [

18] developed an entropic political equilibrium framework for multiparty democracies with "floating voters", suggesting that the level of uncertainty or dispersion among voters can be captured with an entropy-based ENP calculation. On the other hand, Golosov [

19] introduced a new approach to the ENP calculation that addresses biases in highly fragmented or concentrated contexts, thereby refining the index’s performance across different electoral environments. This index assigns a reduced weight to smaller parties to limit their impact on the calculation of the effective number of parties. Its formula is as follows:

where

represents the proportion of seats or votes obtained by the

i-th party and

is the largest party’s proportion of all votes or seats.

Although this method is effective in describing complex multiparty systems, it primarily focuses on "ex post" data (electoral results), which limits its usefulness for predicting the effects of institutional reforms or for emerging political systems, particularly in Africa.

Existing methods that focusing on raw votes or seats alone fails to capture true political influence [

15]. Caulier and Dumont [

16] extend the idea of relevant parties by integrating voting-power measures into ENP. Their work provides a more nuanced count that better reflects a party’s actual capacity to influence legislative or executive outcomes. Further, Blau et al [

15] outlines how ENP can be measured at four scales—votes, seats, legislative power, and cabinet power—highlighting that large seat shares do not always translate into proportional policy influence. Because ENP is closely linked to how many parties "effectively" matter, other works also examine party system fragmentation and nationalization. Kselman and Powell [

26] explore how party fragmentation can facilitate new party entry in established democracies, connecting these dynamics to observed ENP values. Golosov [

27] places ENP within the broader context of party system nationalization, showing how territorial heterogeneity can influence fragmentation and the distribution of party support. Xhaferaj [

28] applies the ENP concept to the Albanian party system, underscoring the importance of context-specific measures for newer democracies. Grofman and Kline [

17] propose a measure of the ideologically cognizable number of parties, reflecting the degree to which parties can be grouped based on coherent policy or ideological positions.

Recently, the "Seat Product Model" [

21], a mathematical model based on deductive principles, offered predictive and theoretical models that connect ENP to broader electoral system properties, such as district magnitude, mechanical effects of electoral rules, and heterogeneity of the electorate. This model predicts the effective number of parties in a legislature based on the district magnitude (

M) and the size of the assembly (

S):

This formula is based on the idea that partisan fragmentation depends on the permissiveness of the electoral system. It is notable for its simplicity and independence from social or behavioral variables, making it a universally applicable tool for institutional design. However, its limitations include the exclusion of complex (multi-level) systems and the inability to predict the number of parties receiving votes (

). Li and Shugart [

29] extend the Seat Product model to include multi-level electoral systems (with compensatory seats) and integrate data from elections in both established and emerging democracies. Their model retains Taagepera’s simple institutional structure while adding a corrective factor for complex systems, with the following formula:

where is an empirically determined constant related to the proportion of seats allocated at the upper level (t). represents the product of district magnitudes and the total size of base seats. They also demonstrate that adding social variables, such as ethnic diversity, only marginally improves prediction accuracy. Finally, they establish a relationship between et , showing that the gap between the two remains constant, enabling an indirect estimation of electoral fragmentation.

In summary, three major approaches have been widely used such as the Laakso-Taagepera index [

12], the Golosov model [

19], and the Seat Product Model by Taagepera [

21]. The three models present complementary approaches for measuring and predicting the effective number of political parties. The Laakso-Taagepera model remains a benchmark for its simplicity, while Golosov provides a useful correction for highly concentrated systems. Finally, Taagepera’s "Seat Product" model offers a robust institutional perspective. However, gaps remain, particularly in accounting for behavioral dynamics and social cleavages. Integrating the strengths and limitations of these models could pave the way for more comprehensive tools for analyzing party systems.

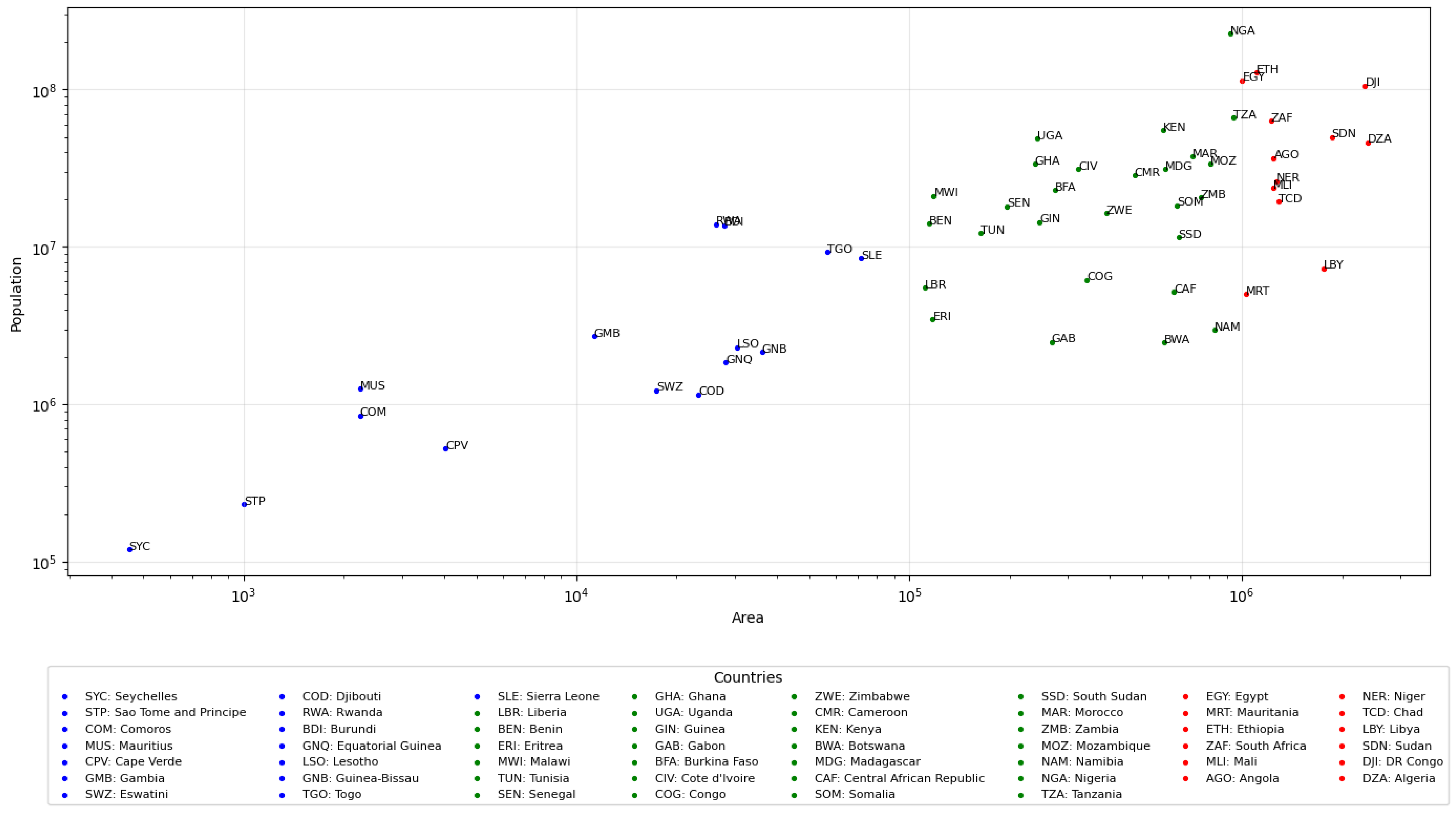

Figure 1.

Population vs. Area of African Countries

Figure 1.

Population vs. Area of African Countries

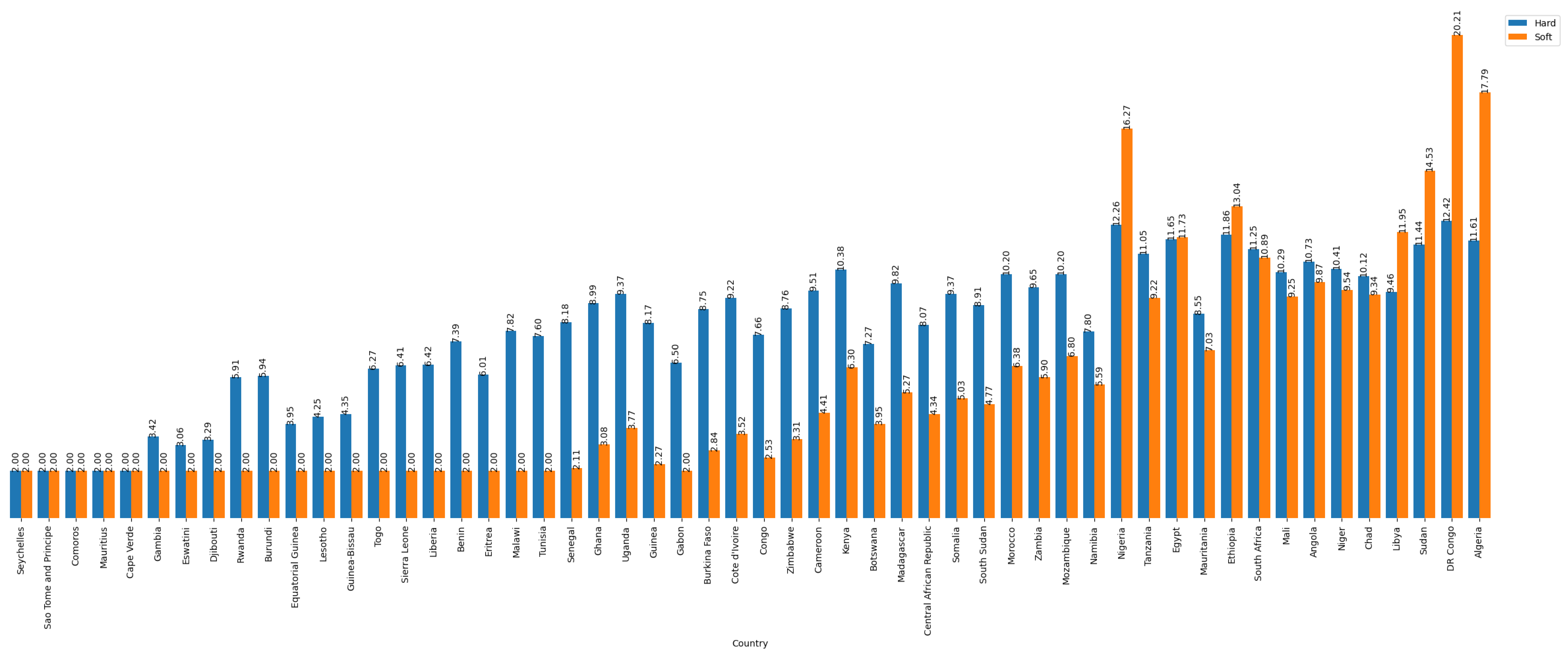

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effective number of parties between Hard and Soft Index across different countries

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effective number of parties between Hard and Soft Index across different countries

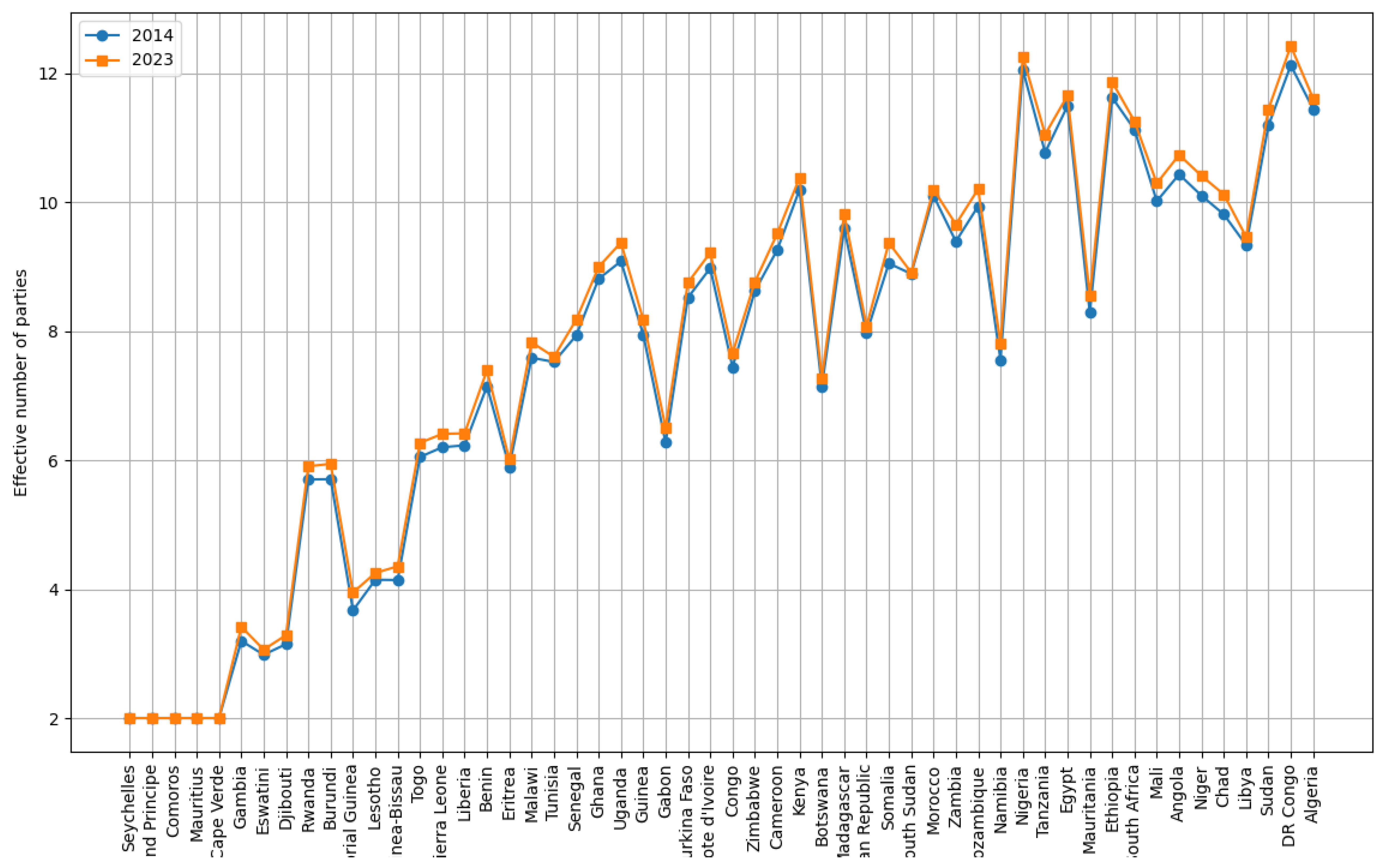

Figure 3.

Party Systems Trends in Africa using Hard Index: Examining the shift in the effective number of political parties from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 3.

Party Systems Trends in Africa using Hard Index: Examining the shift in the effective number of political parties from 2014 to 2023.

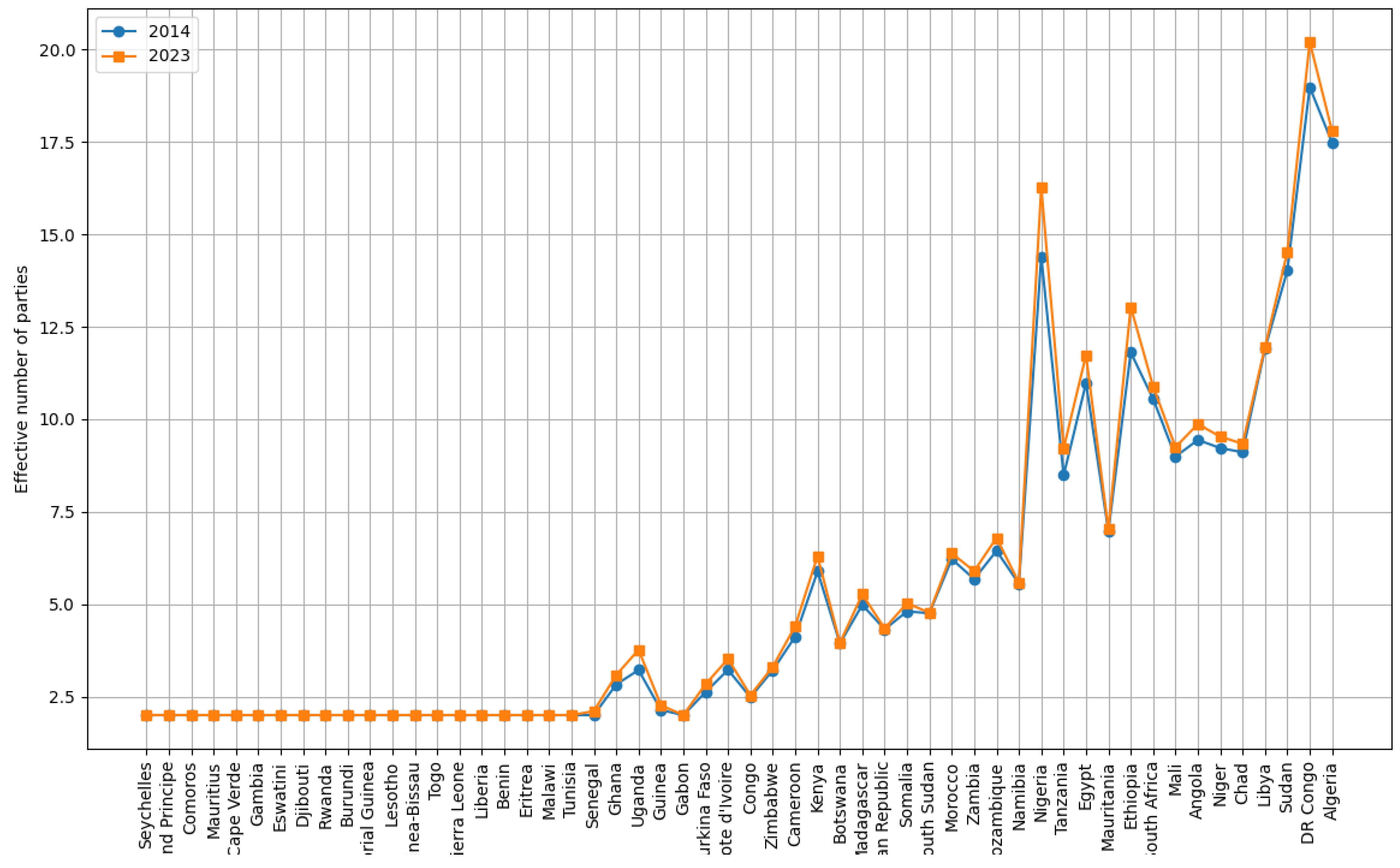

Figure 4.

Party Systems Trends in Africa using Soft Index: Examining the shift in the effective number of political parties from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 4.

Party Systems Trends in Africa using Soft Index: Examining the shift in the effective number of political parties from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 5.

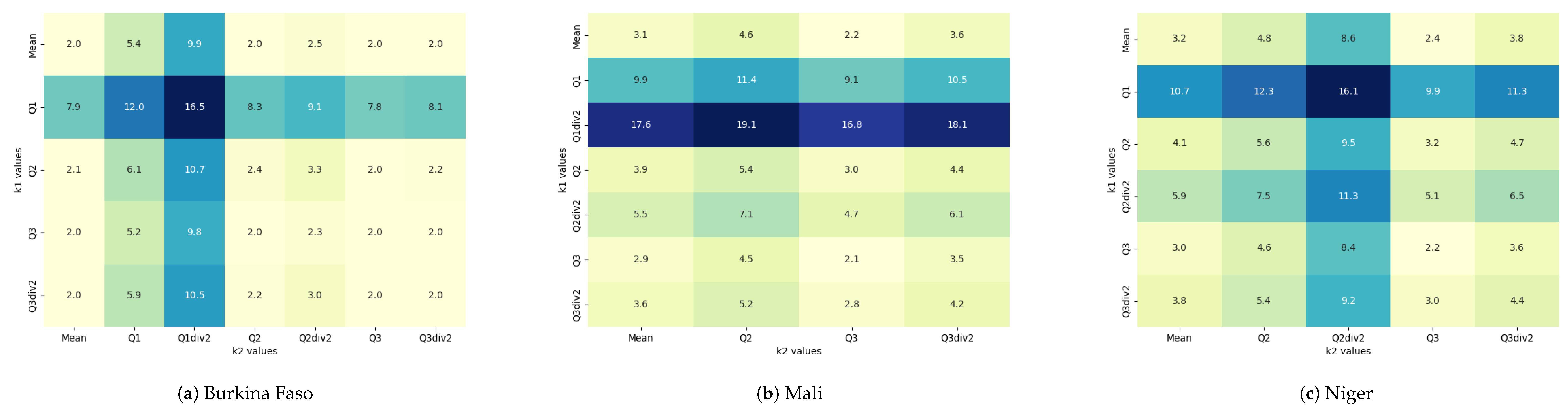

Effective Number of Parties values for the Confederation of Sahel States, illustrating the impact of different combinations of and across various statistical measures. For each country, the heatmap displays a matrix of ENP values. Each cell in the heatmap represents the ENP for a specific pairing of and , where these parameters take values derived from the mean, quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3), and their respective divisions by 2 (Q1div2, Q2div2, Q3div2). The color intensity represents the magnitude of ENP values, with darker shades indicating higher values.

Figure 5.

Effective Number of Parties values for the Confederation of Sahel States, illustrating the impact of different combinations of and across various statistical measures. For each country, the heatmap displays a matrix of ENP values. Each cell in the heatmap represents the ENP for a specific pairing of and , where these parameters take values derived from the mean, quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3), and their respective divisions by 2 (Q1div2, Q2div2, Q3div2). The color intensity represents the magnitude of ENP values, with darker shades indicating higher values.

Figure 6.

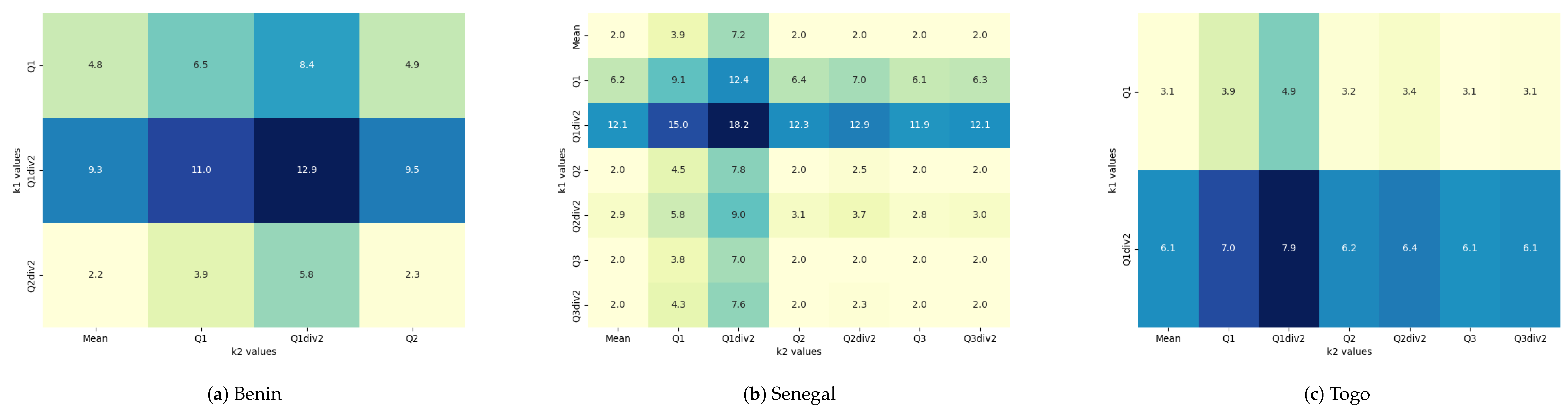

Effective Number of Parties values for ECOWAS, illustrating the impact of different combinations of and across various statistical measures. For each country, the heatmap displays a matrix of ENP values. Each cell in the heatmap represents the ENP for a specific pairing of and , where these parameters take values derived from the mean, quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3), and their respective divisions by 2 (Q1div2, Q2div2, Q3div2). The color intensity represents the magnitude of ENP values, with darker shades indicating higher values.

Figure 6.

Effective Number of Parties values for ECOWAS, illustrating the impact of different combinations of and across various statistical measures. For each country, the heatmap displays a matrix of ENP values. Each cell in the heatmap represents the ENP for a specific pairing of and , where these parameters take values derived from the mean, quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3), and their respective divisions by 2 (Q1div2, Q2div2, Q3div2). The color intensity represents the magnitude of ENP values, with darker shades indicating higher values.

Figure 7.

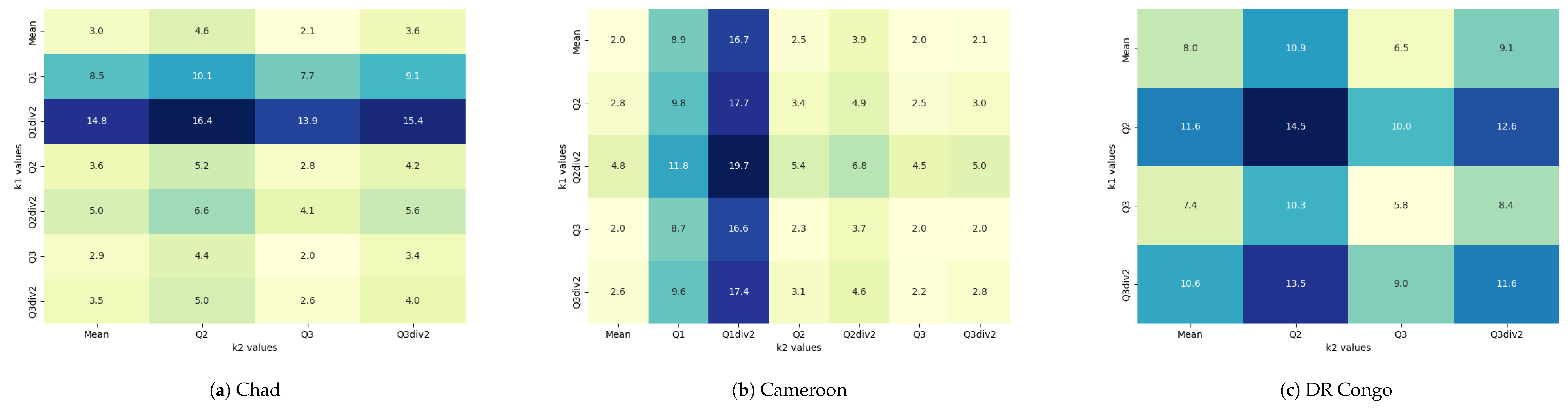

Effective Number of Parties values for ECCAS, illustrating the impact of different combinations of and across various statistical measures. For each country, the heatmap displays a matrix of ENP values. Each cell in the heatmap represents the ENP for a specific pairing of and , where these parameters take values derived from the mean, quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3), and their respective divisions by 2 (Q1div2, Q2div2, Q3div2). The color intensity represents the magnitude of ENP values, with darker shades indicating higher values.

Figure 7.

Effective Number of Parties values for ECCAS, illustrating the impact of different combinations of and across various statistical measures. For each country, the heatmap displays a matrix of ENP values. Each cell in the heatmap represents the ENP for a specific pairing of and , where these parameters take values derived from the mean, quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3), and their respective divisions by 2 (Q1div2, Q2div2, Q3div2). The color intensity represents the magnitude of ENP values, with darker shades indicating higher values.

Table 1.

Sample of the final dataset

Table 1.

Sample of the final dataset

| Country |

Population |

Area |

Region |

Community |

| DR Congo |

109 276 265 |

2 267 050 |

Central Africa |

ECCAS |

| Togo |

9 304 337 |

56 785 |

West Africa |

ECOWAS |

| Burkina Faso |

23 548 781 |

273 600 |

West Africa |

AES |

| Mali |

24 478 595 |

1 220 190 |

West Africa |

AES |

| Niger |

27 032 412 |

1 266 700 |

West Africa |

AES |

Table 2.

Effective number of parties for Africa countries using Noua Indexes

Table 2.

Effective number of parties for Africa countries using Noua Indexes

| Country |

Hard Index |

Soft Index |

Mean of Both models |

| Seychelles |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

| Sao Tome and Principe |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

| Comoros |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

| Mauritius |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

| Cape Verde |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

| Gambia |

3.42 |

2.00 |

2.71 |

| Eswatini |

3.06 |

2.00 |

2.53 |

| Djibouti |

3.29 |

2.00 |

2.65 |

| Rwanda |

5.91 |

2.00 |

3.96 |

| Burundi |

5.94 |

2.00 |

3.97 |

| Equatorial Guinea |

3.95 |

2.00 |

2.98 |

| Lesotho |

4.25 |

2.00 |

3.12 |

| Guinea-Bissau |

4.35 |

2.00 |

3.17 |

| Togo |

6.27 |

2.00 |

4.13 |

| Sierra Leone |

6.41 |

2.00 |

4.21 |

| Liberia |

6.42 |

2.00 |

4.21 |

| Benin |

7.39 |

2.00 |

4.70 |

| Eritrea |

6.01 |

2.00 |

4.00 |

| Malawi |

7.82 |

2.00 |

4.91 |

| Tunisia |

7.60 |

2.00 |

4.80 |

| Senegal |

8.18 |

2.11 |

5.14 |

| Ghana |

8.99 |

3.08 |

6.04 |

| Uganda |

9.37 |

3.77 |

6.57 |

| Guinea |

8.17 |

2.27 |

5.22 |

| Gabon |

6.50 |

2.00 |

4.25 |

| Burkina Faso |

8.75 |

2.84 |

5.79 |

| Cote d’Ivoire |

9.22 |

3.52 |

6.37 |

| Congo |

7.66 |

2.53 |

5.09 |

| Zimbabwe |

8.76 |

3.31 |

6.04 |

| Cameroon |

9.51 |

4.41 |

6.96 |

| Kenya |

10.38 |

6.30 |

8.34 |

| Botswana |

7.27 |

3.95 |

5.61 |

| Madagascar |

9.82 |

5.27 |

7.54 |

| Central African Republic |

8.07 |

4.34 |

6.21 |

| Somalia |

9.37 |

5.03 |

7.20 |

| South Sudan |

8.91 |

4.77 |

6.84 |

| Morocco |

10.20 |

6.38 |

8.29 |

| Zambia |

9.65 |

5.90 |

7.78 |

| Mozambique |

10.20 |

6.80 |

8.50 |

| Namibia |

7.80 |

5.59 |

6.70 |

| Nigeria |

12.26 |

16.27 |

14.27 |

| Tanzania |

11.05 |

9.22 |

10.14 |

| Egypt |

11.65 |

11.73 |

11.69 |

| Mauritania |

8.55 |

7.03 |

7.79 |

| Ethiopia |

11.86 |

13.04 |

12.45 |

| South Africa |

11.25 |

10.89 |

11.07 |

| Mali |

10.29 |

9.25 |

9.77 |

| Angola |

10.73 |

9.87 |

10.30 |

| Niger |

10.41 |

9.54 |

9.97 |

| Chad |

10.12 |

9.34 |

9.73 |

| Libya |

9.46 |

11.95 |

10.71 |

| Sudan |

11.44 |

14.53 |

12.98 |

| DR Congo |

12.42 |

20.21 |

16.32 |

| Algeria |

11.61 |

17.79 |

14.70 |

Table 3.

Differents values of k1 and k2

Table 3.

Differents values of k1 and k2

| Statistics |

K1 |

K2 |

| Mean |

26123118.10 |

511180.71 |

| Q1(25%) |

2525592.25 |

28680.00 |

| Q2(50%) |

14152176.50 |

269800.00 |

| Q3(75%) |

31957274.50 |

814062.50 |

Table 4.

Comparison of the effective number of parties predicted by our models with state-of-the-art methods (Laakso, Golosov, and Seat Product) across African countries: Traditional methods lack data for countries without elections (e.g., Eritrea, Libya), while the institution-free Noua indexes provide ENP values in such cases. The table highlights inconsistencies in traditional methods, such as misclassifying medium and large countries as single-party systems and outlier values for the Democratic Republic of Congo, underscoring the advantages of the Noua indexes in unstable or non-democratic contexts.

Table 4.

Comparison of the effective number of parties predicted by our models with state-of-the-art methods (Laakso, Golosov, and Seat Product) across African countries: Traditional methods lack data for countries without elections (e.g., Eritrea, Libya), while the institution-free Noua indexes provide ENP values in such cases. The table highlights inconsistencies in traditional methods, such as misclassifying medium and large countries as single-party systems and outlier values for the Democratic Republic of Congo, underscoring the advantages of the Noua indexes in unstable or non-democratic contexts.

| Country |

Laakso |

Golosov |

Seat Product |

Ours ( Noua Hard Index) |

Ours ( Noua Soft Index ) |

| Ethiopia |

1.07 |

1.04 |

7.77 |

11.86 |

13.04 |

| South Sudan |

1.11 |

1.06 |

5.54 |

8.91 |

4.77 |

| Djibouti |

1.13 |

1.07 |

4.02 |

3.29 |

2 |

| Tanzania |

1.26 |

1.13 |

7.32 |

11.05 |

9.22 |

| Comoros |

1.41 |

1.22 |

2.88 |

2 |

2 |

| Tunisia |

1.47 |

1.25 |

4.61 |

7.6 |

2 |

| Sudan |

1.72 |

1.4 |

7.52 |

11.44 |

14.53 |

| Rwanda |

1.77 |

1.43 |

3.66 |

5.91 |

2 |

| Mozambique |

1.79 |

1.45 |

6.3 |

10.2 |

6.8 |

| Congo |

1.79 |

1.45 |

5.33 |

7.66 |

2.53 |

| Burundi |

1.79 |

1.45 |

4.93 |

5.94 |

2 |

| Cameroon |

1.8 |

1.37 |

5.65 |

9.51 |

4.41 |

| Ghana |

1.85 |

1.53 |

6.51 |

8.99 |

3.08 |

| Algeria |

1.86 |

1.49 |

7.41 |

11.61 |

17.79 |

| Zimbabwe |

2.05 |

1.81 |

6.54 |

8.76 |

3.31 |

| Guinea |

2.06 |

1.6 |

4.83 |

8.17 |

2.27 |

| Gabon |

2.07 |

1.62 |

5.23 |

6.5 |

2 |

| Sierra Leone |

2.08 |

1.81 |

5.13 |

6.41 |

2 |

| Seychelles |

2.08 |

1.87 |

3.27 |

2 |

2 |

| Togo |

2.14 |

1.67 |

4.5 |

6.27 |

2 |

| Namibia |

2.17 |

1.69 |

4.58 |

7.8 |

5.59 |

| Angola |

2.2 |

2.05 |

6.04 |

10.73 |

9.87 |

| Uganda |

2.28 |

1.75 |

8.09 |

9.37 |

3.77 |

| Cape Verde |

2.41 |

2.13 |

4.16 |

2 |

2 |

| South Africa |

2.58 |

1.99 |

7.37 |

11.25 |

10.89 |

| Mauritania |

2.6 |

1.97 |

5.6 |

8.55 |

7.03 |

| Zambia |

2.76 |

2.4 |

5.38 |

9.65 |

5.9 |

| Nigeria |

2.77 |

2.32 |

7.11 |

12.26 |

16.27 |

| Senegal |

2.89 |

2.44 |

5.48 |

8.18 |

2.11 |

| Botswana |

2.94 |

2.24 |

3.85 |

7.27 |

3.95 |

| Madagascar |

2.95 |

2.72 |

5.46 |

9.82 |

5.27 |

| Sao Tome and Principe |

2.95 |

2.49 |

3.8 |

2 |

2 |

| Equatorial Guinea |

2.98 |

2.28 |

8.42 |

3.95 |

2 |

| Egypt |

2.98 |

2.28 |

8.4 |

11.65 |

11.73 |

| Cote d’Ivoire |

3.21 |

2.46 |

6.33 |

9.22 |

3.52 |

| Mauritius |

3.42 |

3.17 |

4.12 |

2 |

2 |

| Benin |

3.48 |

3.12 |

4.78 |

7.39 |

2 |

| Kenya |

4.03 |

3.34 |

7.04 |

10.38 |

6.3 |

| Guinea-Bissau |

4.05 |

3.35 |

4.67 |

4.35 |

2 |

| Malawi |

4.13 |

3.72 |

5.77 |

7.82 |

2 |

| Chad |

4.32 |

3.26 |

5.73 |

10.12 |

9.34 |

| Lesotho |

4.43 |

3.73 |

4.93 |

4.25 |

2 |

| Gambia |

4.53 |

4.51 |

3.76 |

3.42 |

2 |

| Morocco |

5.68 |

5.49 |

7.34 |

10.2 |

6.38 |

| Mali |

5.7 |

4.61 |

5.28 |

10.29 |

9.25 |

| Central African Republic |

6.05 |

5.8 |

5.19 |

8.07 |

4.34 |

| Niger |

6.09 |

4.63 |

5.5 |

10.41 |

9.54 |

| Burkina Faso |

6.45 |

5.15 |

5.03 |

8.75 |

2.84 |

| Liberia |

6.94 |

6.96 |

4.18 |

6.42 |

2 |

| DR Congo |

34.08 |

36.67 |

7.81 |

12.42 |

20.21 |

| Eritrea |

- |

- |

- |

6.01 |

2 |

| Eswatini |

- |

- |

- |

3.06 |

2 |

| Libya |

- |

- |

- |

9.46 |

11.95 |

| Somalia |

- |

- |

- |

9.37 |

5.03 |