1. Introduction

Transparent materials have become increasingly important in recent years, particularly in the production of antireflective coatings, consumer equipment, aviation, and military, to name a few [

1,

2,

3]. Silica glass and transparent ceramics have been widely used in various applications demanding transparency and mechanical strength; however, because of their brittle nature, sudden failure under mechanical load has demanded the need to find alternative materials having high transparency [

4,

5]. Moreover, due to the increasing trend in flexible devices using transparent materials, it has become inevitable to find new and innovative materials that can accomplish both flexibility and transparency [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Hybrid polymer-ceramic particulate nanocomposites have attracted increasing attention as advanced materials due to their unique properties, such as high strength, good thermal stability, and excellent optical properties. In particular, the optical properties of nanocomposites, such as transparency, refractive index, and absorption, have been widely studied and utilised in various applications, including optical coatings, sensors, and optoelectronics. Significant research efforts have been carried out in recent years to the production of highly transparent materials. It has been widely known that the transmittance of a polymer ceramic composite does not depend entirely on the difference in refractive indices of the constituents, rather it depends on multiple other factors, which include (but are not limited to) particle size, film thickness and the filler ratio [

10]. Advancements in nanotechnology and nanoscience, on the other hand, have paved the way to produce new polymer hybridised with high-RI nanoparticles (nps) [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The size effect plays a vital role in the manufacturing of electronic ceramics based on ferroelectrics, such as barium titanate. The application of these materials depends on the nanocrystalline ferroelectric ceramics are based on new effects inherent to this class of materials due to changing particle size of powders or ceramic grains [

15,

16]. The basic properties are phase transitions, which ultimately affect dielectric characteristics [

17]. Moreover, dielectric properties are also influenced by the grain size [

15]. Piezoelectric is a widely used material all over the world because of its applications in n number of electronic devices such as microphones, automobile seat belts, medical research, electric lighters, and Inkjet printers.

Optical composite materials are intended to have qualities that are superior to those of their constituent components [

5,

18]. These composites are used in a wide range of applications, including strain sensors, electronic displays, optical attenuators, and smart windows. One of the most important optical properties of these materials is transmittance, which refers to the ability of light to pass through a material. Transmittance is influenced by both intrinsic material characteristics, including particle size and refractive index, and extrinsic factors such as composite thickness, surface roughness, filler loading, and the degree of particle dispersion. The particle size and refractive index of the components are important factors that determine the transmittance of an optical composite material. When the particle size is small, light can pass through more easily, resulting in higher transmittance. Additionally, a high refractive index allows for more efficient transmission of light through the material. Extrinsic properties such as the thickness of the composite, roughness, and concentration of filler particles also affect transmittance. A thinner composite generally allows for more efficient transmission of light, as there are fewer opportunities for light to be scattered or absorbed by the material. Surface roughness can also scatter light, reducing transmittance. Finally, the concentration and dispersion state of filler particles can affect transmittance, as optimal concentration and dispersion will allow for more efficient transmission of light. To understand the basic optical behaviour of nanocomposites and to develop advanced materials with the desired optical characteristics, it is crucial to theoretically investigate the relationship between film thickness and filler ratio and their impact on the optical properties of hybrid polymer-ceramic particulate nanocomposites.

In this paper possibility of manufacturing transparent piezoelectric composite material will be investigated theoretically in epoxy-based composites. The effect of volume fraction, particle size and film thickness will be investigated to predict the transmittance, and a linkage to piezoelectricity will be established.

2. Methods

The use of Rayleigh scattering theory in calculating the transparency of polymer nanohybrid composites is a valuable tool for designing and optimising such materials for various applications. Rayleigh scattering theory is based on the principle that when light encounters small particles, such as nanoparticles or molecules, the light is scattered in all directions, resulting in a change in the intensity and direction of the transmitted light. The amount of scattering depends on several factors, including the particle size, the refractive index of the particles and the medium in which they are dispersed, and the wavelength of the incident light. In the case of polymer nanohybrid composites, the scattering centres are the dispersed nanoparticles, and the polymer matrix acts as the medium in which they are suspended. Our model is based on the Beer-Lambert law, which describes the absorption of light as it passes through a material. However, this law only considers absorption and does not account for scattering of light by particles in the material. To address this limitation, we have incorporated Rayleigh scattering theory, which describes the scattering of light by particles that are smaller than the wavelength of light.

The key parameter in our model is the effective refractive index, neff, which considers the refractive indices of both the matrix and the fillers. This parameter is calculated using the Maxwell-Garnett equation, which assumes that the fillers are small compared to the wavelength of light. The following assumptions were made.

The hybrid polymer ceramic composite is optically homogeneous.

The composite consists of spherical particles of radius r.

The particles are dispersed in a polymer matrix with refractive index nNP.

The surrounding medium has refractive index n0.

The thickness of the composite is l.

The volume fraction of the particles is ϕ.

Derivation of Equation

Using the Beer-Lambert law and Rayleigh scattering theory, we can derive an equation to measure the transparency of hybrid composites with particle sizes smaller than the wavelength of light, causing the light to scatter in all directions. we start with the Beer-Lambert law, which relates the transmittance T of light through a material to its absorption coefficient α and thickness

l:

where I is the intensity of light after passing through the material, I

0 is the initial intensity of light, α is the absorption coefficient, and l is the thickness of the material. From the equation for k:

Rearranging for α we get

where k is the imaginary part of the refractive index.

Substituting this expression for α into the Beer-Lambert law, we get:

The intensity of light scattered by a single nanoparticle can be calculated using Mie theory, which gives a more accurate description of scattering from spherical particles. The intensity scattered by all the nanoparticles can be calculated by summing over all the particles using the following expression:

where the sum is taken over all the nanoparticles and I

s is the intensity scattered by a single nanoparticle.

The total intensity of light transmitted through the composite is then given by:

Substituting the expressions for I and I

s' and simplifying, we get:

where Q_ext is the extinction efficiency of a single nanoparticle, given by Mie theory.

Finally, the transparency T is defined as the ratio of the transmitted intensity to the incident intensity:

Substituting the expression for I

t and simplifying, we get:[

12]:

The following are what is represented in the above equation T = Transmittance, I = Intensity of transmitted light, I

0= Incident light intensity,

τ= Turbidity,

l = Hybrid composite thickness, d= diameter of nanoparticles (NPs),

ϕ = Volume percentage of NPs,

n0= Refractive index of the polymer matrix,

nNPs = Refractive index of NPs and

λ = Incident light wavelength [

12].

For composites, epoxy and barium titanate (BT) will be used as the resin and ceramic filler, respectively. Epoxy has a refractive index of approximately 1.53, and BT has a refractive index of approximately 2.412, which will be used for calculations. The wavelength of the incident light will be kept constant at 520 nanometres.

3. Results

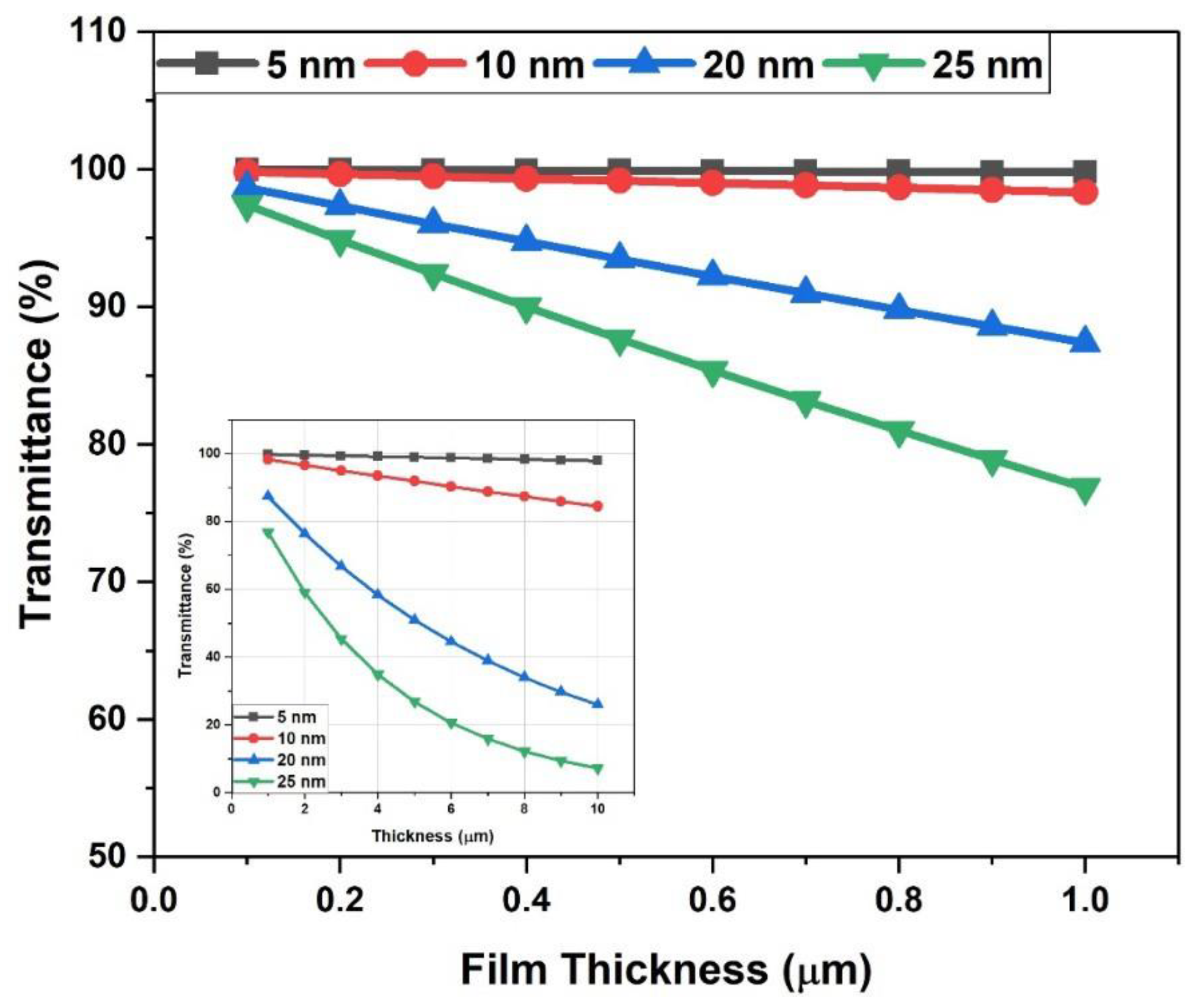

Figure 1 shows the correlation between the transmittance and the particle size within a polymer ceramic composite of various thicknesses (between 0.1-1 µm). It is obvious that the optical transmittance shows an appreciable decline with the varying film thickness. However, it is worth noting that the transmittance stayed nearly constant for composites where the ceramic particle was 5 nm at a film thickness of 0.1 µm, which decreased slightly when the particle size increased to 10 nm in consistent with experimental results for similar composites [

19,

20]. The optical transmittance of the materials strongly depends on the thickness as the thicker materials help in providing more scattering centres for the light to refract. The transmittance continued to decrease with increasing particle size and reached a value of ~75% at a film thickness of 1 µm for a particle size of 25 nm. The inset elaborates further on the relationship between film size and the transmittance for thicker films compared to what has already been discussed. Transmittance dropped to less than 10% at a film thickness of 10µm. The increasing film thickness led to a decrease in the optical transmittance. The decrease in the optical transmittance in the materials leads to a substantial increase in opacity, and it signifies the use of thin film to obtain transparency in composite materials. The decrease in transmittance with increasing film thickness has important implications for the use of composite materials in applications where transparency is important. For instance, in the context of smart windows, thinner composite films may be more desirable to maintain high transmittance and avoid a substantial increase in opacity. The inset shows the effect of thicker films on transmittance.

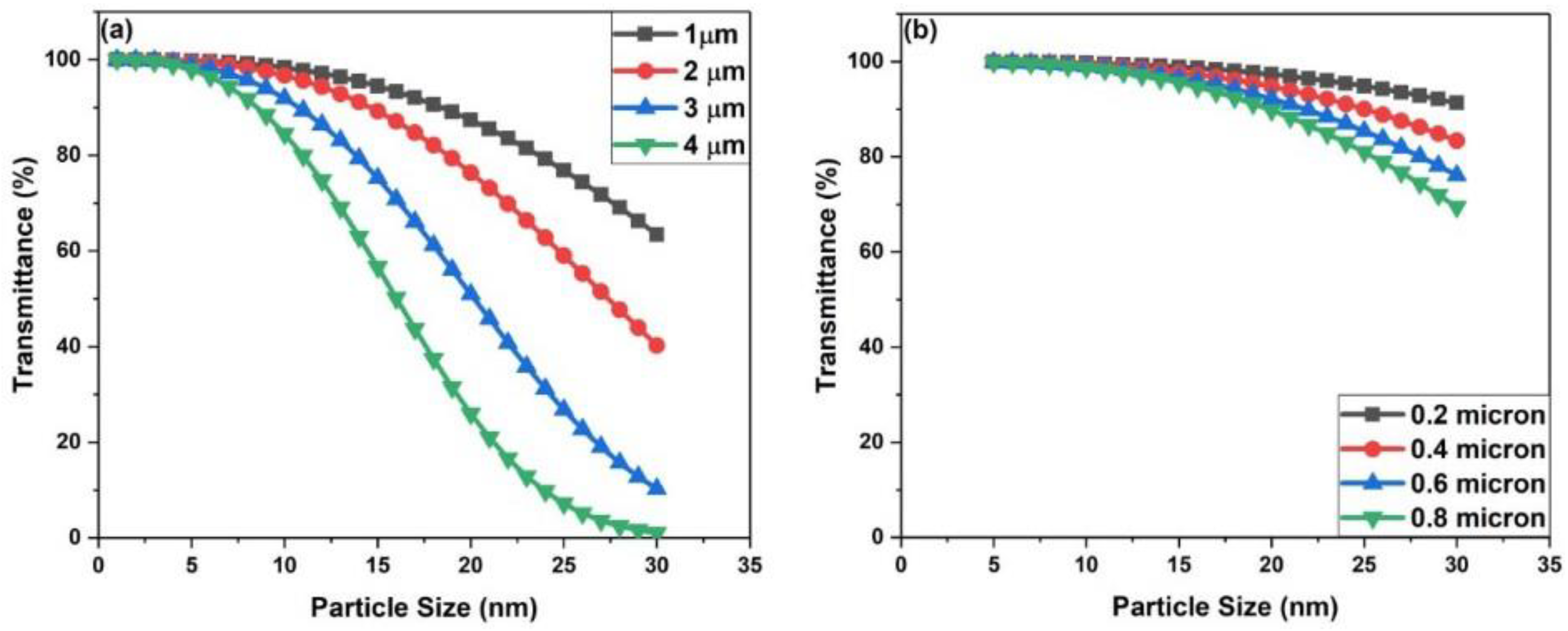

Figure 2 presents the relationship between film thickness, particle size, and transmittance in optical composite materials. The results show an inverse relationship between transmittance and film thickness as a function of particle size. As the film thickness and particle size increase, the transmittance decreases due to an increase in scattering centres, making the composite material more opaque [

5]. For instance, in

Figure 2(a), the transmittance reached zero at a film thickness of 4 µm and a particle size of 30 nm, indicating that the composite material would be completely opaque to light. This finding highlights the importance of controlling both film thickness and particle size when designing composite materials for optical applications. However,

Figure 2(b) shows that for thinner films, the transmittance did not decrease as profoundly as for thicker films, indicating that thinner films may be more suitable for achieving high transmittance in composite materials. For example, a transmittance value of nearly 95% was achieved with a film thickness of 0.2 µm and a particle size of 35 nm. This result suggests that thinner films may be more suitable for achieving high transmittance in composite materials. The increase in dispersed phase packing density in the nanolayer is proportional to the increase in film material density, resulting in a decrease in transparency. Thus, the increase of both variables together has a significant effect on the transmittance of light through the composite material as it demonstrates the complex interplay between film thickness, particle size, and transmittance in optical composite materials. The design and optimisation of composite materials for various applications, including smart windows, electronic displays, and optical attenuators, among others, require a thorough understanding of the relationship between film thickness, particle size, and transmittance. The results in

Figure 2 provide valuable insights into this relationship and can inform the development of new composite materials with tailored optical properties. For instance, if the goal is to achieve high transmittance, thinner films and smaller particle sizes should be used to reduce the number of scattering centres in the composite material. Alternatively, if the goal is to achieve opacity, thicker films and larger particle sizes should be used to increase the number of scattering centres.

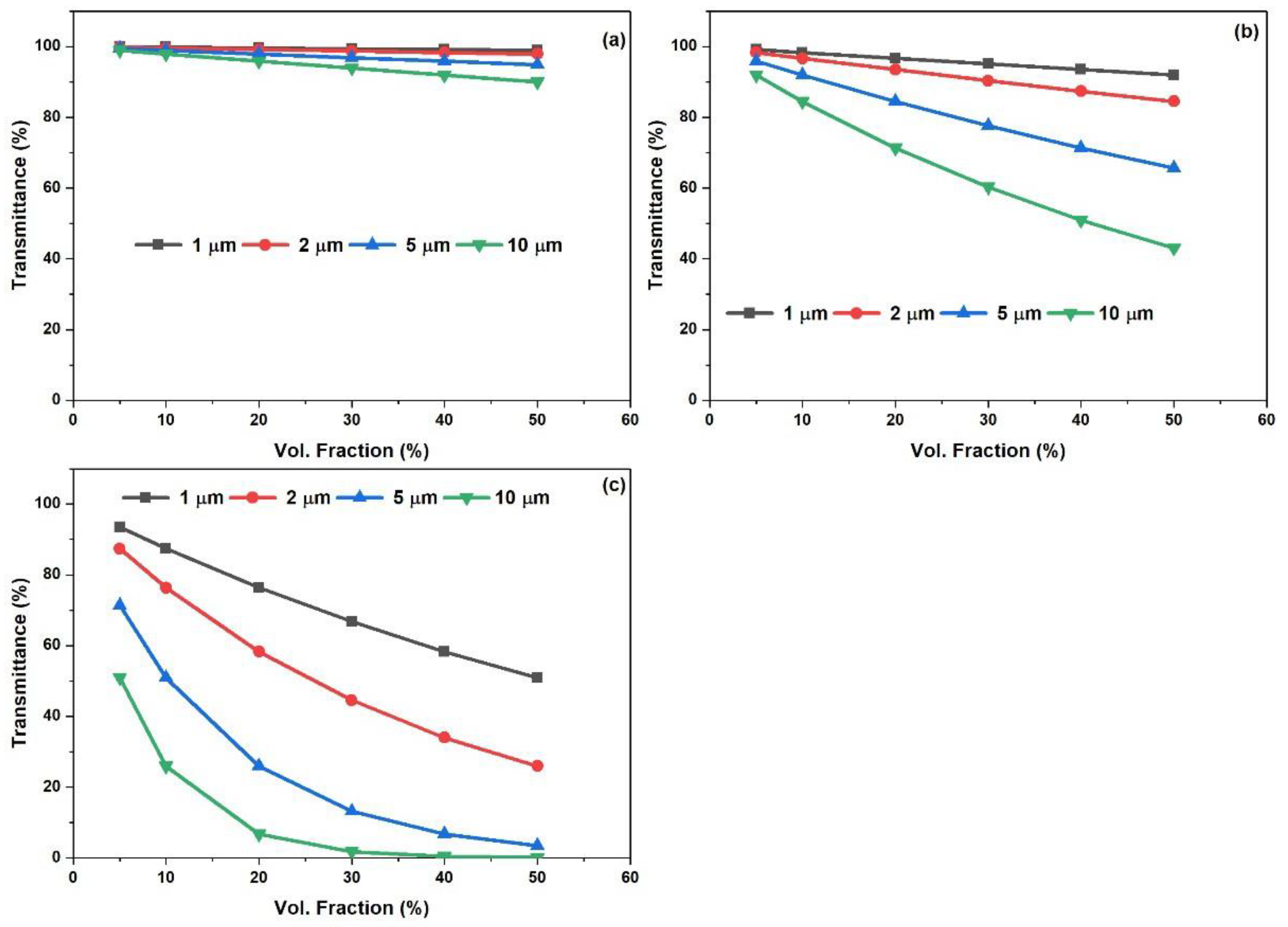

Figure 3 shows the influence of the ceramic filler loading fraction on the transmittance percentage in relation to the different film thicknesses at various particle sizes, such as 5nm (

Figure 3(a), 10nm (

Figure 3(b) and 20 nm (

Figure 3(c). It was noticed that the calculated transmittance followed an inversely proportional relationship to the disperse phase volume fraction. At a particle size of 5nm, the film thickness did not seem to have a significant effect on the reduction of the transmittance of the composite. The particle size was too small to create a noticeable effect on the transmittance at the given wavelength of 520nm. However, when the particle size was increased to 10nm, a noticeable change started to emerge upon increasing the film thickness. A drop of nearly 60% was observed at a film thickness of 10 µm compared to the similar film thickness when using a particle size of 5nm. This drop declined to nearly 95% when a particle size of 20nm was used in the calculation. Another important factor that affects the transmittance of the films is the agglomeration of the particles, as this aids in determining how many particles we can put into a system. To avoid agglomeration and maintain the stability of the composite, various methods have been developed, including surface modification of particles, use of dispersants or surfactants, and sonication. Surface modification involves modifying the surface chemistry of the particles to prevent them from aggregating. Dispersants or surfactants are added to the composite to prevent the particles from coming together. Sonication involves the use of high-frequency sound waves to break up agglomerates and disperse particles throughout the matrix. Another important consideration when designing composite materials is the choice of matrix material. The matrix material should have a refractive index like that of the particles to minimise scattering and increase transparency. In addition, the matrix should be compatible with the particles and provide a stable environment for them to disperse.

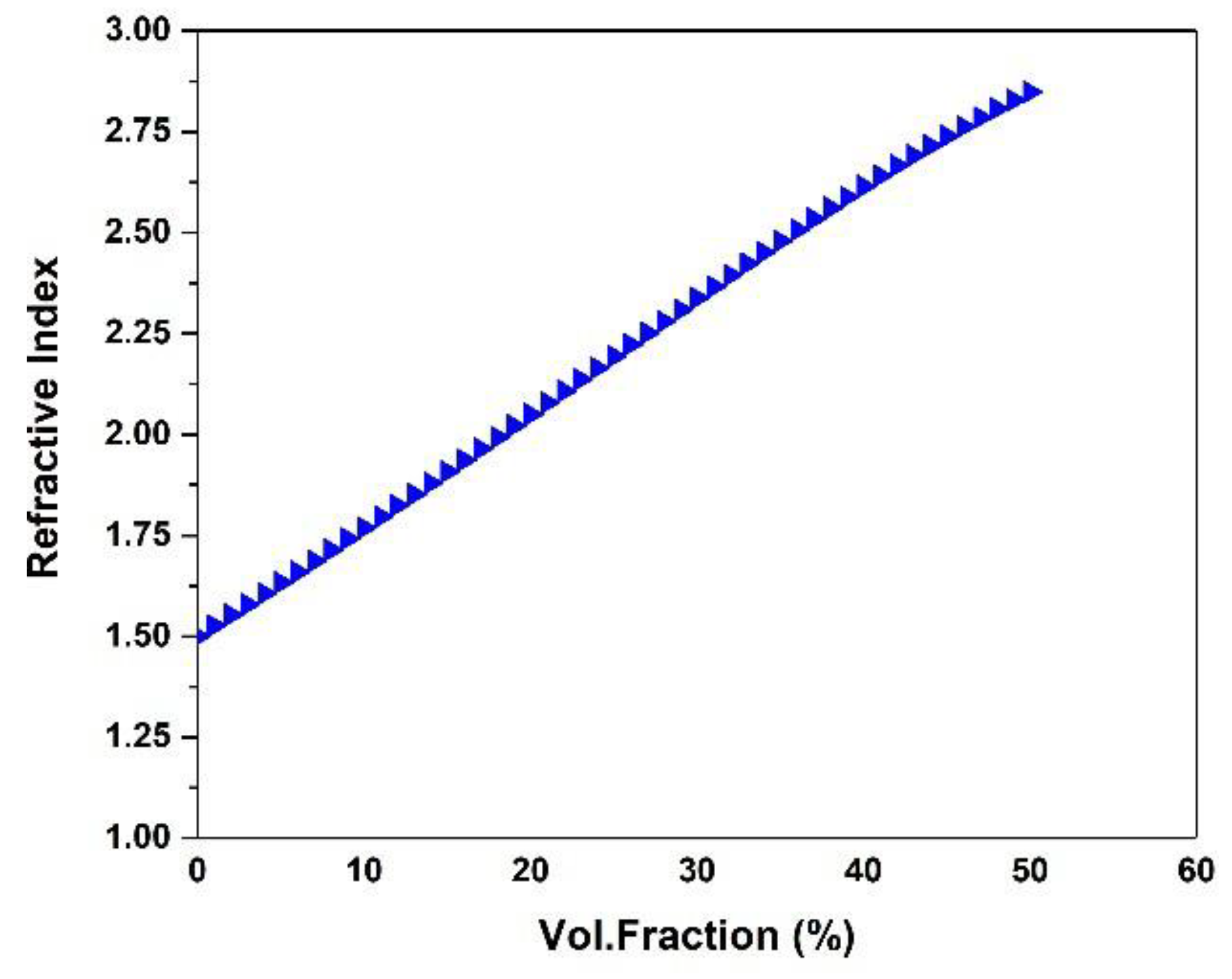

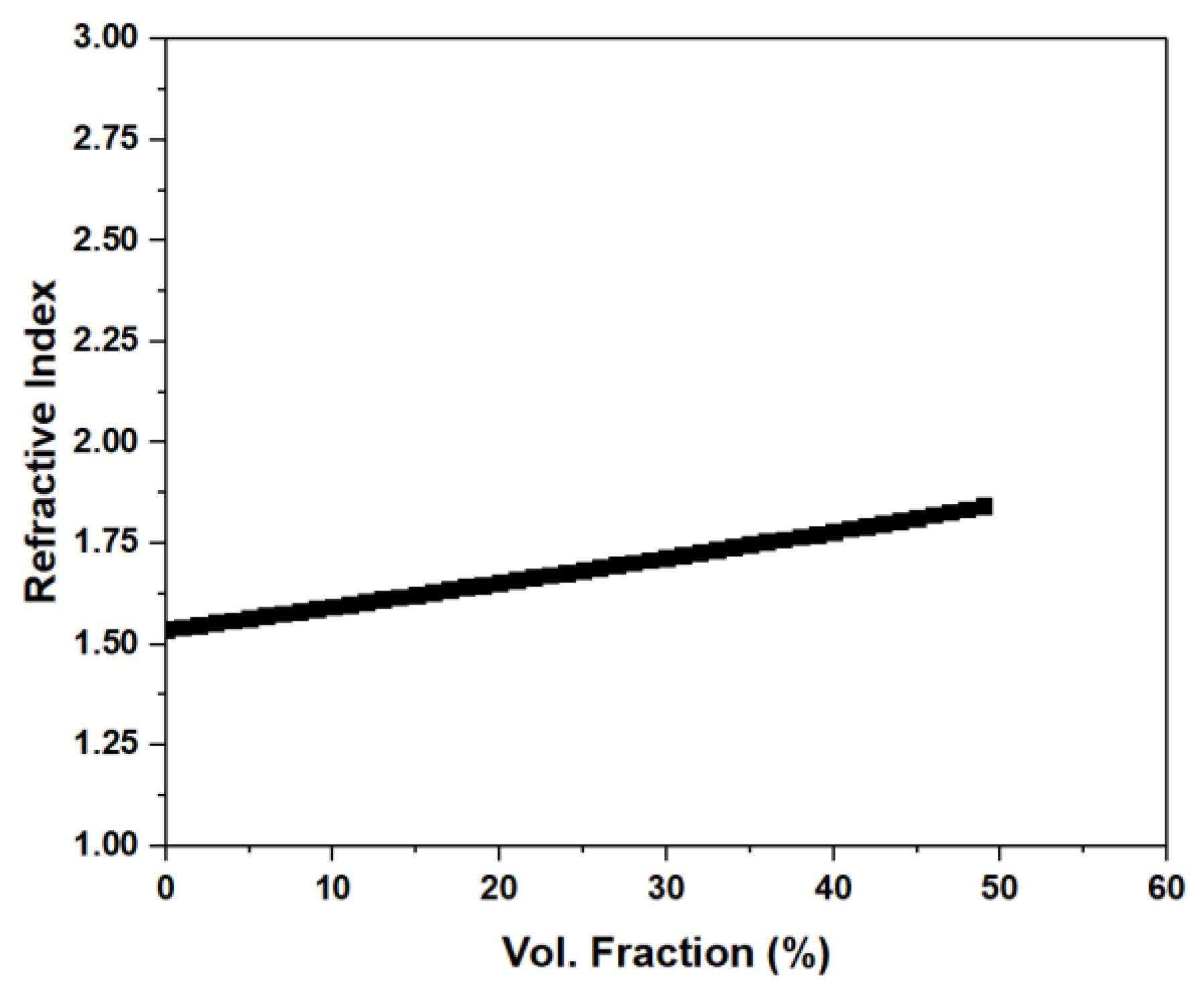

The properties of the constituent materials and their interaction at the nanoscale determine the optical properties of hybrid polymer-ceramic particulate nanocomposites. The refractive index of a material is a measure of its optical density, which determines the speed of light in the material. The refractive index of nanocomposites is influenced by the refractive index of the polymer matrix, the refractive index of the ceramic filler, and the interfacial properties between the polymer and the ceramic. The relationship between the refractive index and the volume fraction of the filler particles is fundamental to understanding the optical properties of composites. By controlling the volume fraction of filler particles in the composite, it is possible to tune the refractive index of the material to meet specific requirements. This can be applied to various applications, such as the development of smart windows and electronic displays, where optical properties such as the refractive index play a crucial role in the performance of the materials.

Figure 4 shows the influence of the nano particle volume fraction on the refractive index of the composite. The volume fraction was taken from 0, which is the pure polymer up to the volume fraction of 50% as it is noted in literature that higher volume fractions result in a composite difficult to manufacture and loss of flexibility [

21,

22]. As can be seen in the figure, the refractive index is directly related to the percentage of volume fraction, where the increase of filler concentration increases the packing of the composite and hence resulting in increasing the refractive index. For this estimation, as mentioned earlier, the particle shape was assumed to be spherical, and it is also assumed that the composites were prepared under such conditions that there are no impurity phases or air bubbles.

Effective medium approximation (EMA) is a commonly used model to estimate the effective optical properties of composite materials. It assumes that the composite material behaves as a homogeneous medium with an effective refractive index, which is a weighted average of the refractive indices of the constituent materials. The EMA equation for the effective refractive index of a two-component composite material can be written as:

where

nef is the refractive index of the composite. Using this equation, we can generate an effective refractive index as a function of ϕ for ceramic nanoparticles and the results are presented in

Figure 5.

As is evident from

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, there is a difference between the refractive indices calculated using the Rayleigh scattering theory and the EMA. Rayleigh scattering theory assumes that the particles in the composite are much smaller than the wavelength of light and that the scattering of light is caused by the interaction of the electric fields of the light with the particles. This model is therefore only valid for small particles. On the other hand, the EMA assumes that the composite material can be treated as a homogeneous medium with an effective refractive index that depends on the refractive indices and volume fractions of the constituent materials. This model is valid for a wider range of particle sizes and shapes, and the refractive index of the composite material is calculated using an averaging process that considers the optical properties of the constituent materials. The difference in the modelling assumptions of Rayleigh scattering theory and EMA can lead to differences in the predicted refractive indices of composite materials, especially for larger particles. In general, EMA tends to provide more accurate predictions for the refractive index of composite materials with larger particles, while Rayleigh scattering theory provides more accurate predictions for composite materials with smaller particles.

Shape is also an additional factor that should be exploited to tune the optical response of the nanocomposite. Spherical particles exhibit higher transmittance and lower refractive index compared to rod-shaped and plate-shaped particles. The aggregation of rod-shaped and plate-shaped particles within the matrix can lead to light scattering, resulting in reduced transmittance and increased refractive index. This has been attributed to the fact that these particles have larger aspect ratios and tend to align themselves within the polymer matrix, leading to the formation of light-scattering domains (LSDs)[

23]. These LSDs can trap and scatter light, leading to an increase in the effective refractive index of the composite and a decrease in its transmittance. Alternative shapes can be easily added into the framework by estimating the response and related optical characteristics of the nanoparticles using different methods (e.g. FEM simulations) [

21]. It would be possible to design materials with tailored optical property. The inclusions must be aligned in a specific direction for this to work. This is particularly intriguing for highly nonlinear nanocomposites, because it permits the degrees of freedom of the material to be used to meet the phase-matching criterion in bulk materials [

22].

5. Conclusions

In this paper, theoretical estimation on the dependence of various factors on the transmittance of polymer-ceramic particulate composite was investigated. For this estimation, epoxy matrix and barium titanate ceramic fillers were used. it has been proven theoretically that, under specific conditions, it is possible to achieve close to 100% transmittance. This transparency depends on the wavelength of light, the diameter of ceramic particles, the thickness of the material and the total volume of filler fraction. From the results epoxy composite exhibited close to 100% transmittance at very low particle sizes, which gradually decreased with increasing particle size. The effect of particle size is more pronounced in films having higher thicknesses due to the increase in packing density as less porosity would be available in a thick film, and thus an increase in the refractive index. Further research is needed to explore the potential of using other matrices and filler materials to achieve optimal transparency. Experimental studies can be conducted to validate the theoretical predictions of this study and to further optimise the conditions for achieving high transmittance. Future studies can also focus on exploring the potential of these transparent composites for specific applications, such as optical devices, composite armour, and smart windows. This could involve studying the impact of different fillers and matrix materials on the specific application requirements, as well as conducting cost-effectiveness and feasibility analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meinders, R.; Murphy, D.; Taylor, G.; Chandrashekhara, K.; Schuman, T. Development of fiber-reinforced transparent composites. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2021, 29, S826–S834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobeiry, N.; Lee, A.; Mobuchon, C. Fabrication of transparent advanced composites. Composites Science and Technology 2020, 197, 108281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caydamli, Y.; Heudorfer, K.; Take, J.; Podjaski, F.; Middendorf, P.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Transparent Fiber-Reinforced Composites Based on a Thermoset Resin Using Liquid Composite Molding (LCM) Techniques. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, T.; Bouville, F.; Lauria, A.; Le Ferrand, H.; Niebel, T.P.; Studart, A.R. Transparent and tough bulk composites inspired by nacre. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-W.; Jin, J.; Bae, B.-S. Optically Transparent Multiscale Composite Films for Flexible and Wearable Electronics. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1907143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Jia, D.; Dirican, M.; Xia, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Cui, M.; Yan, C.; Wan, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Highly Foldable, Super-Sensitive, and Transparent Nanocellulose/Ceramic/Polymer Cover Windows for Flexible OLED Displays. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2022, 14, 16658–16668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Wu, C.; Li, L. Flexible transparent Ag nanowire/UV-curable resin heaters with ultra-flexibility, high transparency, quick thermal response, and mechanical reliability. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2022, 908, 164690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrian, A.V.S.; Carvalho, R.S.; Barreto, A.R.J.; Maturi, F.E.; Barud, H.S.; Silva, R.R.; Legnani, C.; Cremona, M.; Ribeiro, S.J.L. Development of Conformable Substrates for OLEDs Using Highly Transparent Bacterial Cellulose Modified with Recycled Polystyrene. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2022, 6, 2000258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Wang, J.; Lee, P.S. Next-generation multifunctional electrochromic devices. Accounts of chemical research 2016, 49, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, T.; Kagawa, Y. Effect of particle size on light transmittance of glass particle dispersed epoxy matrix optical composites. Acta Materialia 1999, 47, 4321–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Sakamoto, W.; Yogo, T. In situ synthesis of transparent TiO2 nanoparticle/polymer hybrid. Journal of Materials Science 2013, 48, 7503–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Sugihara, O.; Elim, H.I.; Adschiri, T.; Kaino, T. A novel preparation of high-refractive-index and highly transparent polymer nanohybrid composites. Applied physics express 2011, 4, 092601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, G.A.; Nunes, G.B.; Candido, G.; da Silva, J.V.L. The role of 3D printing during COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2021, 6, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Shi, H.-Q.; Xiao, H.-M.; Li, Y.-Q.; Hu, N.; Fu, S.-Y. High performance surface-modified TiO2/silicone nanocomposite. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudinepalli, V.R.; Feng, L.; Lin, W.-C.; Murty, B. Effect of grain size on dielectric and ferroelectric properties of nanostructured Ba0. 8Sr0. 2TiO3 ceramics. Journal of Advanced Ceramics 2015, 4, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacs, V.; Caruntu, G.; Condurache, O.; Ciomaga, C.; Curecheriu, L.; Padurariu, L.; Ignat, M.; Airimioaei, M.; Stoian, G.; Rotaru, A. Preparation and properties of porous BaTiO3 nanostructured ceramics produced from cuboidal nanocrystals. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 18105–18115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.P.; Leung, P.T.; Tse, W.S. Optical properties of composite materials at high temperatures. Solid State Communications 1997, 101, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-P.; Leung, P.; Tse, W.-S. Optical properties of composite materials at high temperatures. Solid state communications 1997, 101, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmezoğlu, S.; Arslan, A.; Serin, T.; Serin, N. The effects of film thickness on the optical properties of TiO2–SnO2 compound thin films. Physica Scripta 2011, 84, 065602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kurosawa, A.; Nagao, D.; Konno, M. Fabrication of barium titanate nanoparticles-epoxy resin composite films and their dielectric properties. Polymer composites 2010, 31, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibshahi, E.; Alamaniotis, M. Simulation and Modeling of Optical Properties of U, Th, Pb, and Co Nanoparticles of Interest to Nuclear Security Using Finite Element Analysis. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayoti, D.; Malik, P.; Prasad, S.K. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on the morphology, dielectric, electro-optic and photo luminescence properties of a confined ferroelectric liquid crystal material. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2018, 250, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, T.; Kagawa, Y. Effect of particle size on the optically transparent nano meter-order glass particle-dispersed epoxy matrix composites. Composites Science and Technology 2002, 62, 1187–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).