3.1. The Medieval Village and the Organization of Its Surroundings

Studying settlement patterns is fundamental to understanding what the landscape was like in the past. Before examining the issue in detail, several points must be clarified. First, as I have noted above, one must consider the

long durée. A few decades ago, it was commonly asserted that medieval villages only emerged after the year 1000. Although it is true that human settlements stabilised after that date, we should not overlook earlier forms of habitation in the preceding centuries, the remains of which are likely to lie beneath many of the modern villages. A further point to consider is that, to understand a village, we must refer both to the settlement nucleus and to its surrounding space, the area from which the inhabitants of the houses obtained the resources necessary for their livelihood. This area had boundaries that we must attempt to identify and comprehend. When doing so, we discover that these boundaries were often stubbornly preserved over the course of centuries. A noteworthy claim has been made: Early medieval hamlets (

vilars) may have lacked stability, yet very frequently the territorial unit within which they ‘moved’ corresponded to one that had already existed in Roman times [

10]. I must acknowledge that recent contributions from the field of archaeology have greatly transformed our understanding of settlement and landscape during these earliest medieval centuries.

I shall begin by focusing on the villages that became consolidated after the year 1000 and that, often without undergoing substantial change, remained intact up to the twentieth century; although, in recent decades, transformations have often been significant. Broadly speaking, based on the available research and of morphogenetic theories, four large categories of villages may be distinguished: clustered groups of houses very often without walls [

3,

11,

12]; ecclesiastical or

sagrera settlements [

3,

13]; castle-based villages; and planned new towns [

3]. Certainly, there also existed linear or street villages, settlements created beside a thermal spring, or those developed around a market square [

3]. Bearing this typology in mind, it is worthwhile to study settlement distribution across different territories and to assess and explain their differences. As will be seen, what emerges is important, for it reveals diverse political and social realities. I shall illustrate this with four examples: one located in the territory of the former county of Barcelona, another in Empordà, a third in Ripollès, and, finally, one in Cerdanya (

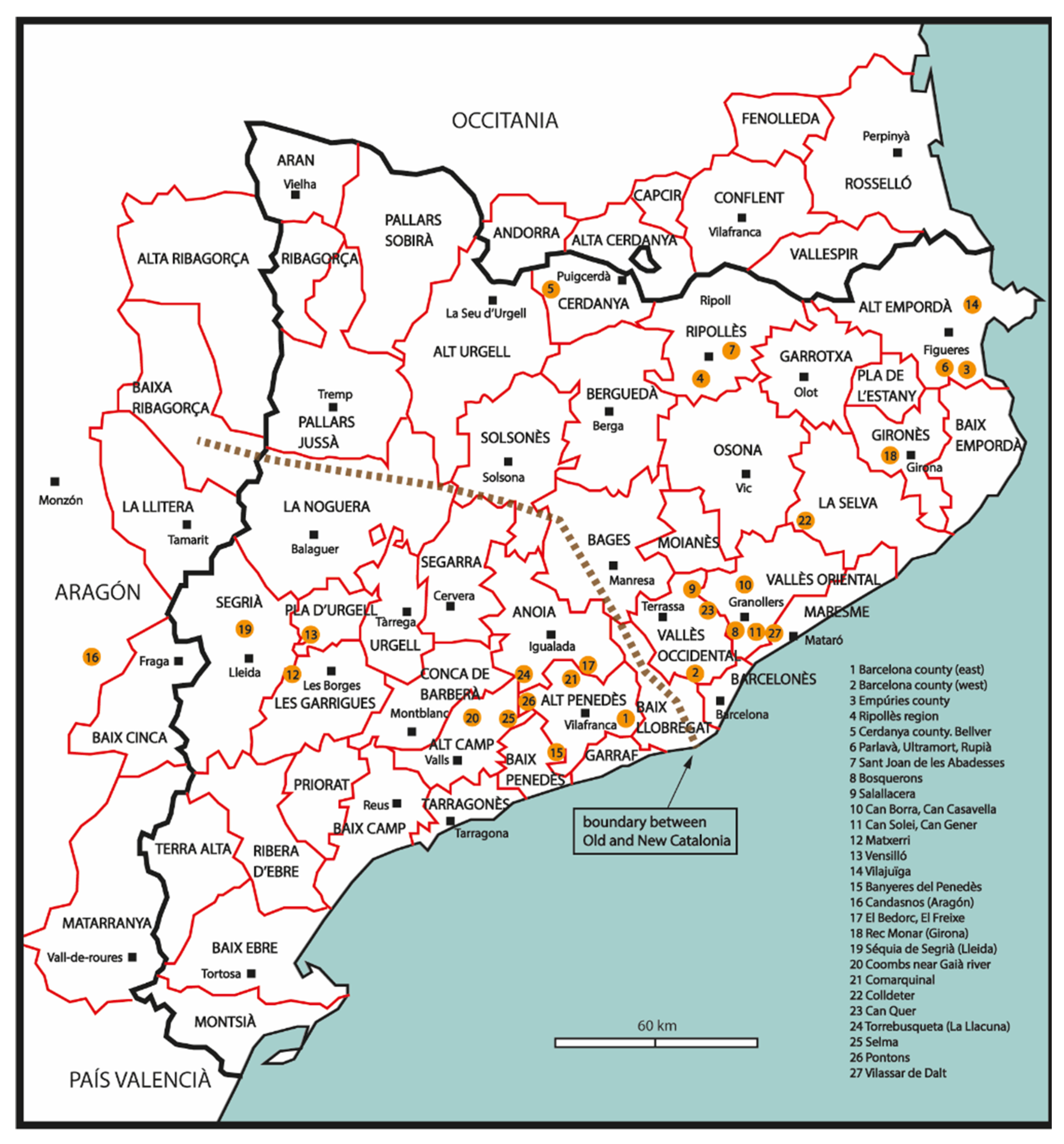

Figure 1).

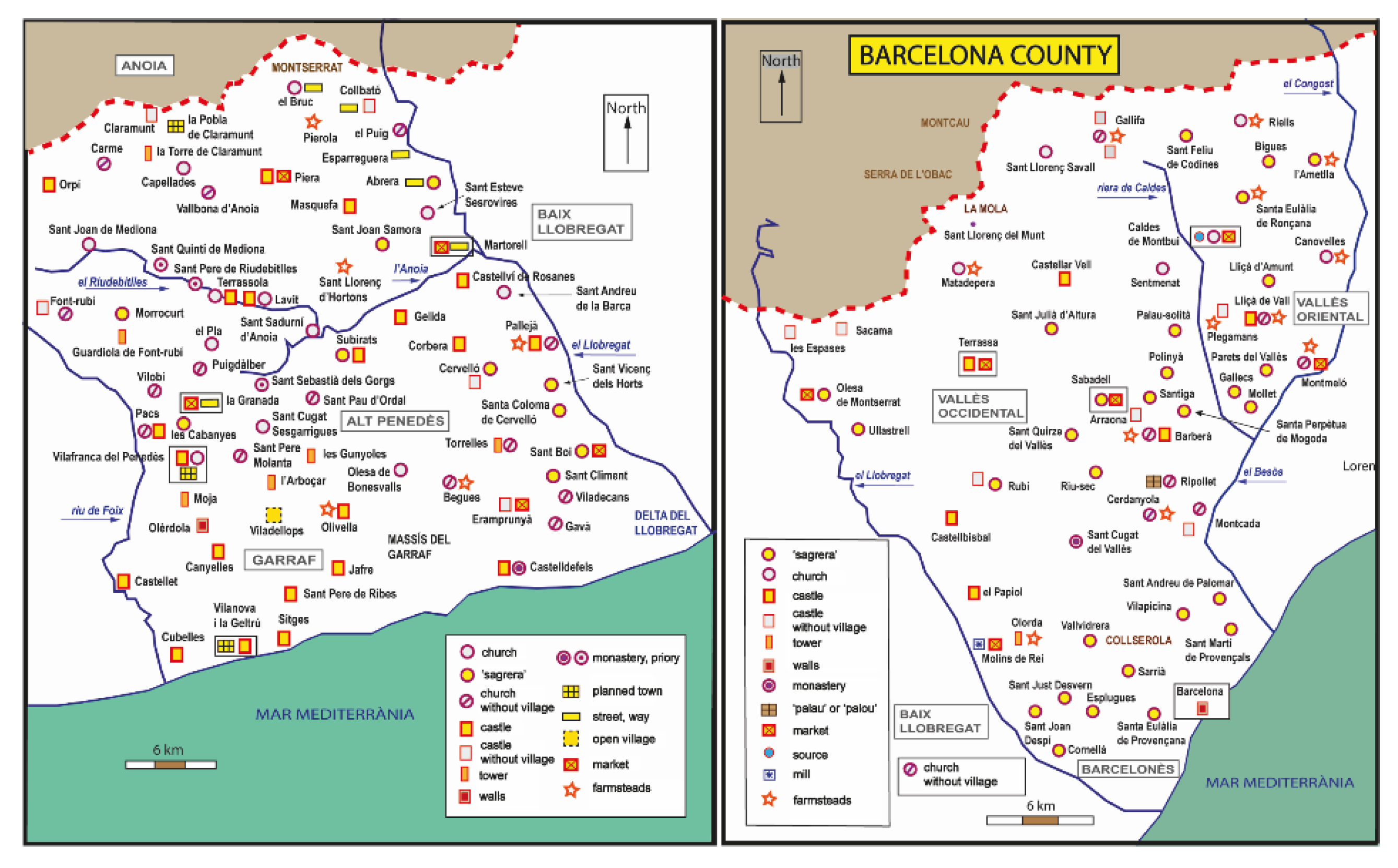

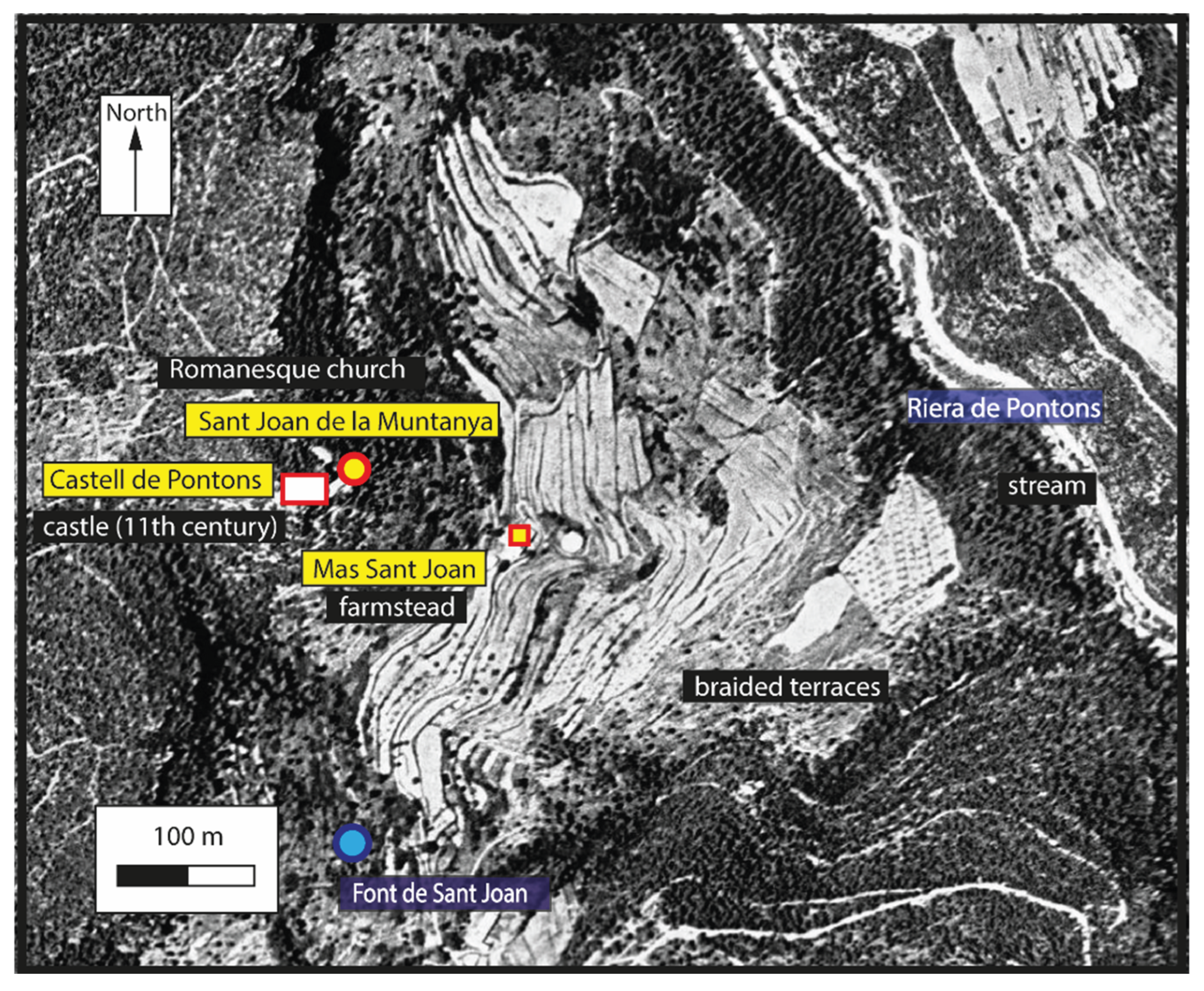

In recent years, various studies have examined the landscape and settlement in the former county of Barcelona [

4,

5,

14,

15]. I shall not offer a detailed description here; rather, I wish to comment briefly on what we observe in the central zone of this county, on both sides of the river Llobregat (

Figure 2). In 801, this river became the frontier between the lands conquered for the Carolingian Empire by Charlemagne’s son and those subject to the Emirate of Córdoba. This frontier had an impact on the landscape, as reflected in the characteristic features of the medieval —and even modern— villages in these places. East of the river, a significant proportion of High Medieval villages emerged around a church, within the thirty-pace area protected by the Church (

sagrera), whereas west of the Llobregat, many villages developed alongside a castle or fortified tower. In addition, across the entire region, we also find settlements established near a monastery or priory, along a road, or beside a marketplace. Although one must bear in mind that villages founded around a

sagrera were created after the year 1000, because of the Peace and Truce of God assemblies, this does not mean that there was no church on the same site beforehand (as has been demonstrated by archaeological research in several locations in the Vallès, for instance at Sentmenat) [

16]. It should also be stressed that not every village situated on high ground should be explained as the product of

incastellamento imposed coercively by a lord after the year 1000; many castle-based villages are older and must be understood as part of a broader process of settlement that moves up a mountain [

17,

18].

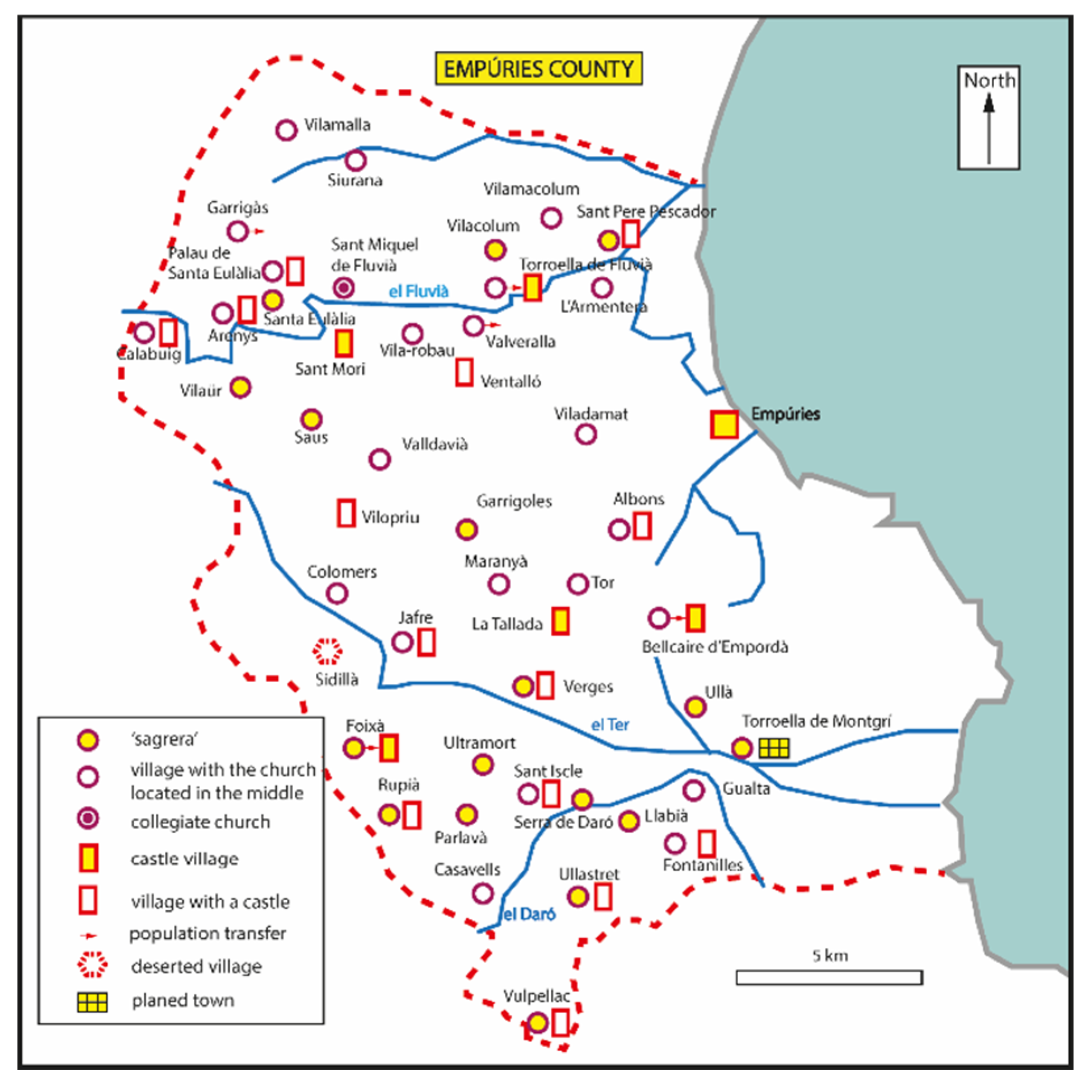

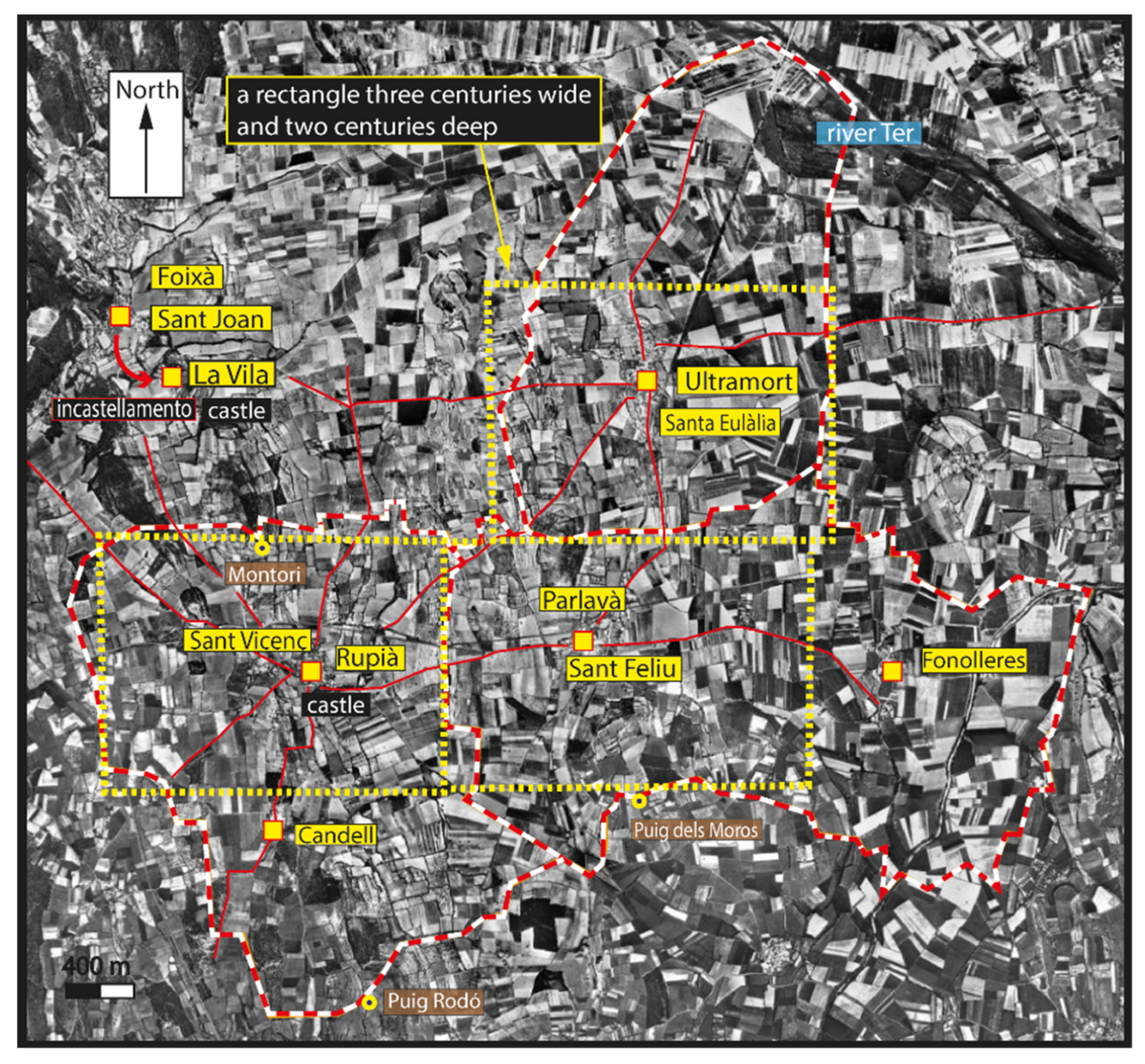

If we turn to Empordà, within the former county of Empúries, a somewhat different reality emerges [

19,

20] (

Figure 3). We observe that many villages of the High Middle Ages were founded within a 30-foot perimeter around a church. A majority of these are

sagrera settlements. Nevertheless, the profound feudalisation of society after the year 1000 led to the construction of castles and fortified houses throughout the region. Many castles were erected very close to the churches and often virtually within the sacral thirty-pace boundary. In certain cases, there was even a relocation of population from the area around the church to the vicinity of the castle, as can be seen at Foixà or Torroella de Fluvià. In these instances, it is indeed appropriate to speak of a process of

incastellamento.

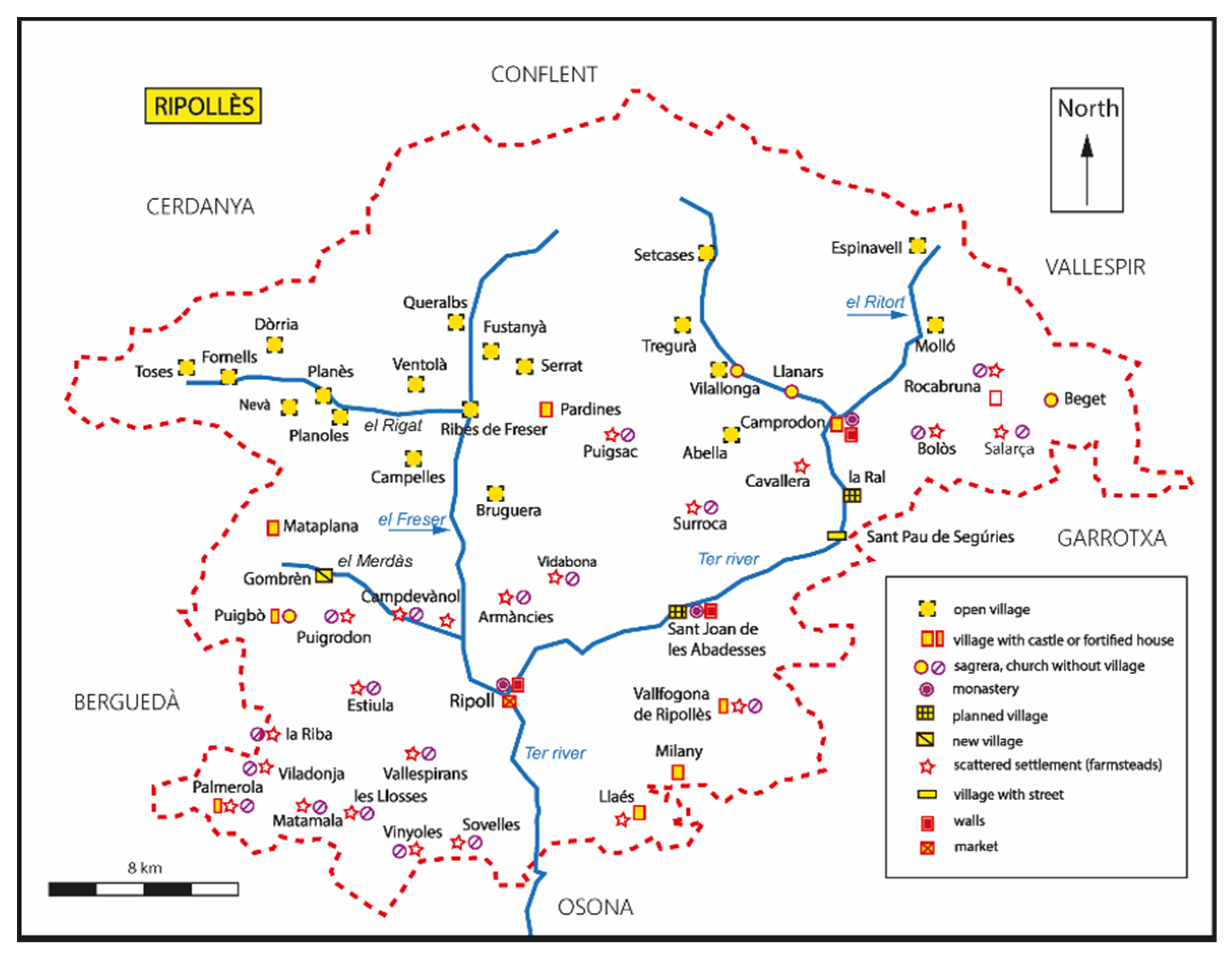

Ripollès is a Pre-Pyrenean district (

comarca) (

Figure 4). In its southern sector, we find a predominance of dispersed settlement, like that further south, in the district of Osona or the Vic plain [

21]. However, in most cases, we do not find evidence of a

sagrera where the population would once have gathered around the local church. Most families lived scattered on their farmsteads. In contrast, in the northern part of Ripollès, nearly all the villages are open, meaning that the houses themselves structure the village space. These dwellings are often separated from one another. All these open settlements, composed of houses not attached, lie at altitudes of around 1000 metres or higher. It is easy to conclude that, in the majority of cases, once the village already existed, a church was subsequently built at a distance from the inhabited core. For example, the church of Sant Cristòfol de Toses, located at 1470 metres, stands to the northeast of the village, above it, slightly removed from the residential area.

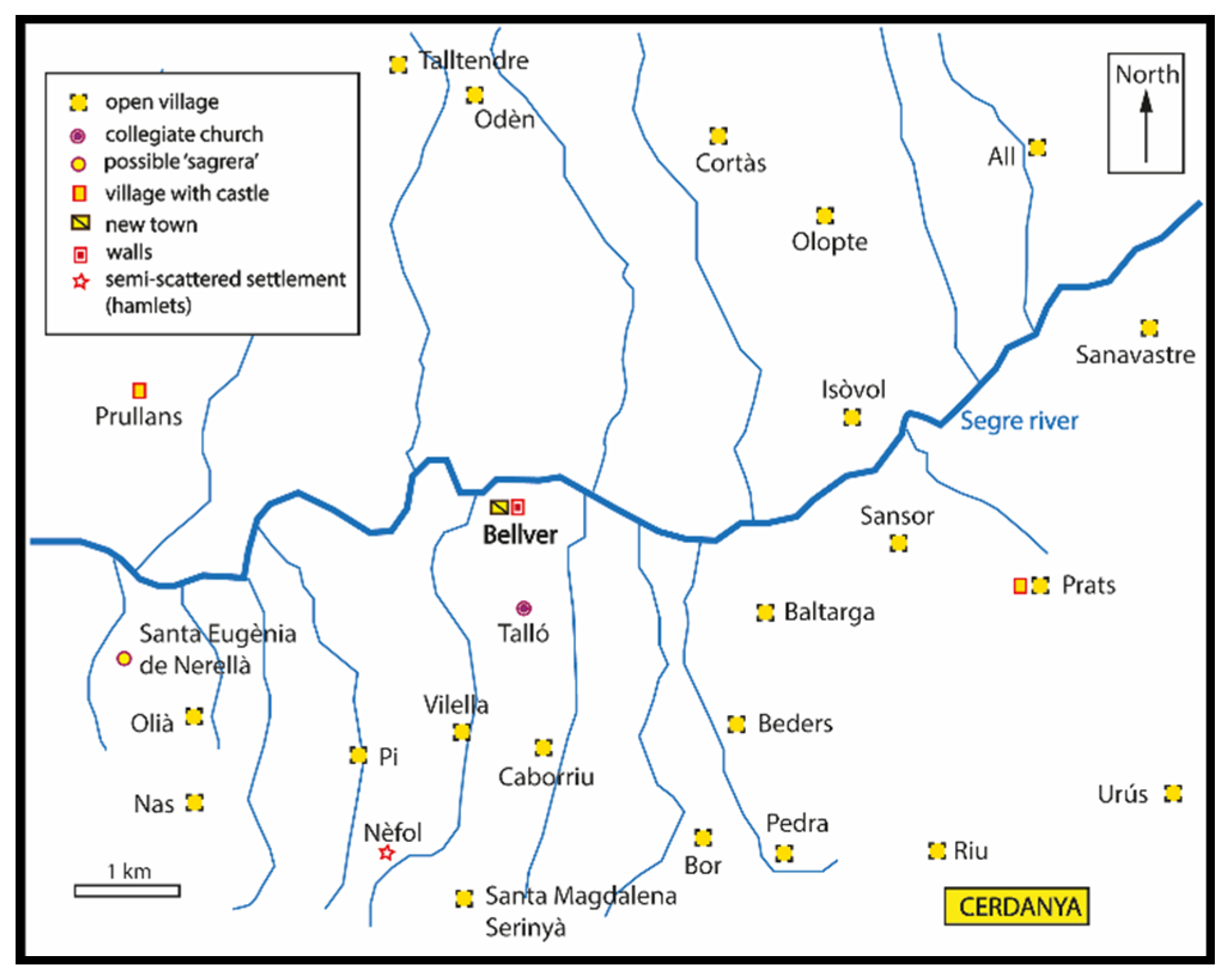

The region (

comarca) of Cerdanya, in the Pyrenees, consists of a high plateau, almost entirely above 1,000 metres, surrounded by mountains and traversed by the river Segre [

23,

24]. I shall focus on the western part of the district, around the town of Bellver (

Figure 5). As the map shows, the vast majority of villages, often not very large, are open settlements, in which the houses themselves determine the shape of the inhabited nucleus. In some of these villages, located above 1,000 metres, there is no church; however, in most cases, the church is detached from the residential centre and quite often built at a higher point, above the houses. As noted earlier regarding Ripollès, the church must have been constructed at a later stage. There are a few cases in which either a church or a castle had a decisive impact on the formation of the late-medieval village. We cannot forget, however, that Bellver was a new planned settlement established in 1225.

As noted above, studying villages means examining how houses, churches, castles, squares, and streets were organised, but it also entails uncovering the nature of the territory on which they depended. This includes understanding the boundaries that enclose their fields, orchards or gardens, pastures, and woodlands. One fact, which may at first appear surprising, must be emphasised: as already mentioned, in some cases these boundaries were older than the village at their centre, despite the latter appearing to be the reason for the existence of the territorial unit. In simplified terms, we may speak of boundaries that coincide with geographical features and of others that follow roads or correspond to pre-medieval orientations. I shall comment briefly on some examples of the latter, though I will not elaborate at length, since these cases are well known. First, mention should be made of Vila-sacra (Alt Empordà), where three of its boundaries (east, south, and west) align precisely with orientations belonging to a pre-medieval centuriation system [

3] (p. 300). Although the name of the place leads us to think of a

villa Alisacari, the estate of an individual bearing a Frankish name [

25], it must be assumed that this 6.2 km² territory, delimited in this way, already existed prior to the Carolingian period —when it is first documented— and very probably before the Visigothic centuries as well.

A second example comes from Baix Empordà. In a will of 989 [

26] (p. 463), reference is made to the donation of an estate extending across the terms of Ultramort (

villa Vultur Murt), Parlavà (

Palacio Ravano), and the villa of Rupià (

villa Rupiano). When these territorial units are plotted on a map, we see that each corresponds to an area of approximately 3.5 km²; we also note that the territory of Rupià expanded towards the south, reaching Puig Rodó, and that of Ultramort extended northwards to the river Ter (in both cases by little more than 1 km²). Here too, the documents and toponyms reveal places of considerable antiquity. A document dated around the year 800 already refers to the church of Santa Eulàlia (

Sancte Eulalie de Vulture Mortuo) [

26] (

Figure 6). It is likewise important to stress that Rupià is a Roman toponym, and that the name Parlavà derives from a

palatium, almost certainly of fiscal origin, and from Hraban, probably a Frankish Germanic name belonging to the individual who settled there at the end of the eighth century [

25]. In short, for our purposes, what matters is that these places and their respective territorial units —whose limits largely coincide with Roman centuriation alignments— very likely existed from the beginning of the medieval period.

Let us turn now to the west of the river Llobregat. The territory of Gelida (Alt Penedès) extends along both sides of the river Anoia. As in the previous examples, the limits on the north-eastern and south-western sides of this territory coincide precisely with a Roman land division, while the south-eastern boundary runs along the mountain ridge. If we isolate the area defined by these ancient delimiting lines, we obtain a rectangle of approximately 13.5 km². What is particularly striking is that the place bears the name of a Berber tribe. At the time of the Islamic conquest, around 713, a group of Amazigh people must have been granted control of this territory, from which a highly strategic point —on the old Via Augusta— could be supervised. They do not appear to have modified the existing boundaries, perhaps because much of the population that had lived there previously remained in place and preserved its memory. At times, territorial organisation and toponymy enable us to formulate hypotheses regarding how people lived and organised their space in the past.

Obviously, it is essential to understand how and when the territories associated with different inhabited sites were formed. Leaving aside the possible pre-medieval precedents already mentioned, the existence of an economic unit must first be recognised, for example, in relation to the territory belonging to the community associated with a hamlet (or a

vilar). In some instances, this territory expanded and was transformed into the territorial unit of a Carolingian

villa, a parish, a castle district, and, in the modern period, a municipality or commune. It should be borne in mind that the combination of several economic units often created a larger territorial whole, such as that of a parish. This is clearly reflected in numerous acts of consecration and endowment of parishes in the ninth and tenth centuries, such as those concerning Aiguafreda (898), L’Ametlla del Vallès (932), or la Roca del Vallès (932) [

27]. In the case of L’Ametlla, the area from which tithes were levied included eleven hamlets or inhabited establishments, some of considerable antiquity, such as Palau (now a

mas) [

4] (pp. 561-561). This territory of L’Ametlla corresponds to the present-day municipality situated in the

comarca of Vallès Oriental.

3.2. The Hamlet: Early Medieval Form of Settlement

In Catalan, there exists a word, fossilised today as a place name, which perfectly describes settlement sites of the early medieval centuries. This word is

vilar, corresponding to English

hamlet, French

hameau, and German

Weiler. The term

vilar appears frequently in medieval documentation, especially in texts from the Carolingian period. It referred to a location containing a small cluster of houses —generally fewer than ten— where there was usually neither a church nor a castle. The dwellings tended to be situated close together. It is important to realise that grasping the significance of this settlement type is key to understanding the habitat of the Early Middle Ages. Archaeologists who have excavated examples, for instance in the regions of Vallès or Rosselló (French: Roussillon), note that these settlements were typically not very stable: every few decades they might be relocated, sometimes only a few hundred metres away [

28].

We shall approach the vilars or hamlets from three perspectives. First, by examining written documentation, which, as I have noted, is particularly abundant in Catalonia during the Carolingian centuries. Second, there is evidence from recent excavations. And third, by consulting current maps and orthophotography surveys. In a certain sense, hamlets may be considered heirs to Roman villae, which were abandoned and collapsed. We know that the peasants and slaves likely remained on the land, whereas the landowners settled in castella or in towns. The majority of hamlets were almost certainly founded during the Early Middle Ages.

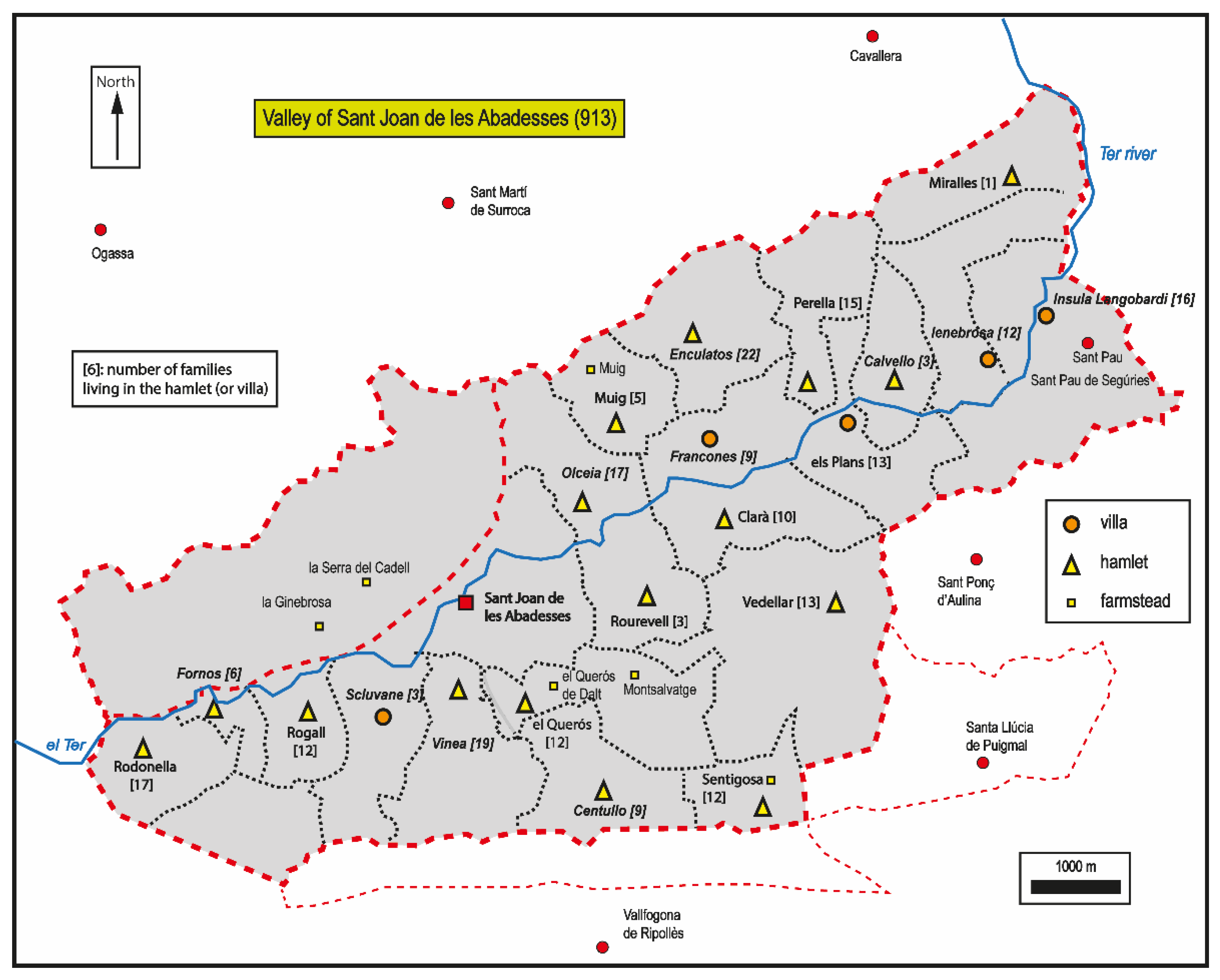

There exists an exceptional document dating to 913, associated with the female Benedictine monastery of Sant Joan de les Abadesses [

21,

29]. The territory of Sant Joan was quite extensive —around 62 km²— and stretched along both banks of the river Ter, in the region of Ripollès (

Figure 7). What is most remarkable in this case is that we can determine how many hamlets existed, what names these settlements bore, and even how many families lived in each of them. In addition, we know the names of every man and woman residing there, a particularly valuable aspect if we wish to study the linguistic origins of personal names and thereby learn more about these people [

29,

30]. What matters here, however, is that within an area of approximately 62 km², much of it mountainous, there were twenty-one hamlets (sometimes considered

villae). They varied in size. In the

vilar of Forns (

Fornos), there were six families; in that of Vedellar, many more, thirteen. In the

vilar of Muig, five families are mentioned, although perhaps not all of them lived within the same settlement cluster, suggesting that at times there may already have existed a degree of dispersed settlement, even prior to the eleventh century. This document has given rise to numerous studies [

30].

It may be stated that, all too often, there is insufficient communication between historians who rely solely on written sources and historians who are archaeologists. Having pursued both approaches to understanding the past, I am aware of this gap, and of a certain sense of superiority occasionally felt by both sides. Be that as it may, it should be acknowledged that the contributions of archaeologists in recent years to the origins of medieval settlement have been fundamental, and it is important that they be reflected in historical syntheses. Let us turn now to two territories where particularly notable research has been carried out.

In the region of Vallès (north of Barcelona), Jordi Roig notes that some early villages were located on the site of former Roman

villae (61%), whereas others were established away from earlier structures (39%) [

31,

32]. The dwellings of these settlements from the sixth to eighth centuries were modest: generally, only sunken-featured buildings covered with wood and branches. These hamlets were originally inhabited by four or five families, and in some cases perhaps slightly more. In addition to the houses, numerous storage silos for cereals were usually present, as were, at times, a necropolis. Wine presses, olive mills, and bread ovens might also have existed. Many of these excavated settlements were situated near watercourses and were not far from one another; distances ranged from 0.5 km to 1.5 km. Since we certainly do not know all the settlements that once existed, it is reasonable to assume that in this plain of Vallès, in this ‘dark’ period, a substantial population may have lived there. It is impossible to compare the population density of the sixth to eighth centuries with that of the Roman period, yet it is clear that the region was by no means deserted.

Because of rescue excavations in Roussillon during the construction of the LGV (Ligne à Grande Vitesse), evidence of four Visigothic-period settlements was discovered along a relatively short stretch. In these cases, no connection with earlier Roman structures could be established [

28]. These settlements also featured storage silos and, in more marginal zones, pottery kilns. Their constructions were built on stone foundations and had

tàpia (rammed earth) walls. As noted above, throughout the sixth to eighth centuries, changes in location were frequent in this plain of Roussillon; these settlements were distributed across a relatively limited territory. As previously suggested, these movements likely occurred within the boundaries of a territory that may have corresponded to that of a former Roman

villa. In fact, this should lead us to think about the weight the lords still held and the importance of the boundaries of large manorial estates.

I have not wished to create a separate section entitled ‘What the dead can tell us.’ However, I believe that understanding the location of early medieval burials is extremely important for two reasons. First, because it allows us to affirm that in certain areas, population density was relatively high in the sixth to eighth centuries. Second, because at times it seems that graves hewn into the rock or built of stone slabs marked reference points within the territory controlled by each community, or even indicated the boundary of the land, depending upon the inhabitants of a particular hamlet.

In the Baix Berguedà (the southern sector of the region), a significant number of rock-cut tombs have been identified. Owing to their location and their structural characteristics, these burials can be securely dated to the fifth to eighth centuries. They were carved into prominent rocky outcrops, sometimes in the middle of a field, sometimes on a slope, and occasionally on the edge of a cliff. Within an area of about 155 km², eighteen tombs or groups of tombs of this type have been documented [

33]. This number is considerable, but almost certainly incomplete. In any case, it may be inferred that each settlement associated with these rock-cut burials might have controlled an area of approximately 8.6 km². Only in very few cases do we know exactly where the individuals buried at these sites lived, though it is evident that they could not have resided far from them, as has been demonstrated in some instances.

As mentioned earlier, in more than one location, these tombs have been observed to lie at or near the limits of the territory belonging to a settlement. A particularly striking example may be seen between Montcortès and L’Aranyó, in the region of Segarra, where a rocky outcrop had been used, in Roman times, to cut eight lateral niches functioning as a columbarium. Later, at the beginning of the Middle Ages, five tombs with rounded ends were hollowed out on their upper surface. The most notable aspect is that this small necropolis lies precisely on the boundary between the two villages, close to where, plausibly, there were already distinct human settlements in the early medieval period.

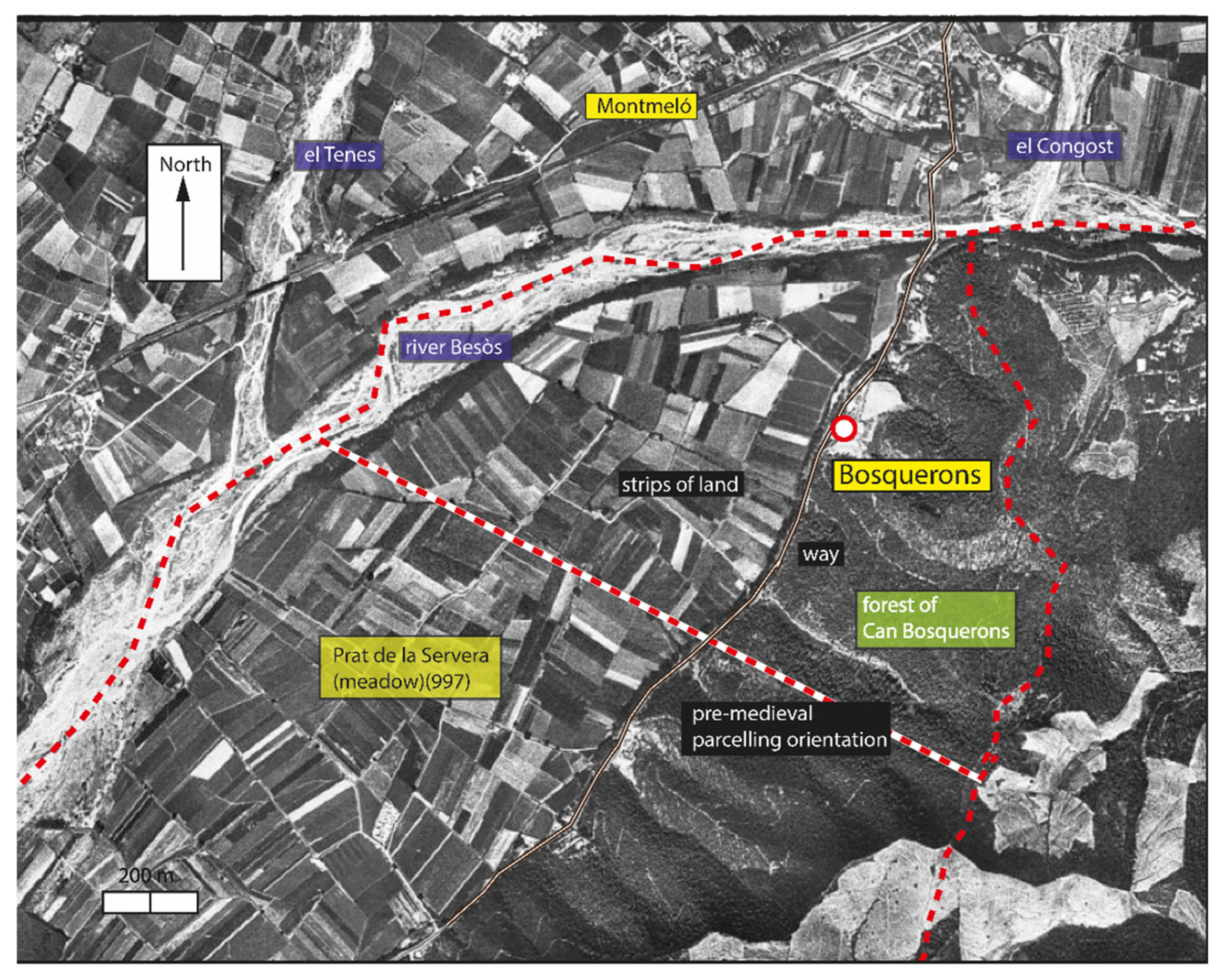

Finally, we may approach the hamlets through the study of present-day orthophotos. We shall consider several locations in the district of Vallès: Bosquerons, Bogunyà, Plandolit, and Salallacera. These four places are well documented, and when we examine current aerial imagery, we detect features that reveal earlier patterns or show how cultivated lands were gradually organised.

Bosquerons, in the municipality of Montornès del Vallès, is an exceptional example (

Figure 8). In a document dated 989 [

34] (p. 912), a strip of land (

fexa I de terra) with a pear tree was sold; this land lay in an area recorded as

Bascherones. The boundary clauses merit attention: to the east was a woodland (

ipso boscho), to the west the river Besòs, and to the north and south two strips of land, presumably similar elongated plots. This site interests us because of the shape of the holdings —parallel strips— but also because of the configuration of this cultivated and inhabited space, which we may regard as a hamlet (with several families) that subsequently became a single farmstead (

mas) [

5] (pp. 361-367). Its morphology recalls, to some extent, what Ausonius described in the fourth century when evoking his small estate [

35] (pp. 215-220): a river, fields, a path beside the dwellings, and, behind them, further uphill, some wood.

Another comparable site is Bogunyà, in the municipality of Terrassa. Although, like most of the places discussed here, it has been considerably transformed over recent decades, we can nonetheless reconstruct its former appearance by consulting mid-twentieth-century aerial photographs. In 1015, the

locum vocitatum in Buguniano was mentioned [

5] (pp. 403-408). This, therefore, is a place bearing a name formed in the Roman period, where tombs constructed with

tegulae —presumably dating from the transitional phase between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages— have been found. In the medieval period, a hamlet was probably established some 400 m north of this necropolis. In front of it, extending as far as the Riera de Palau, there were, in the last century, 3 hectares of market-garden land (

horts). We can also observe braided terraces and, somewhat farther away, to the west and the east, beyond the stream, lie extensive cultivated fields. Further north, in the valley traversed by the torrent of Can Bogunyà, there would once have been oak woodland, attested in medieval documentation. Despite the uncertainties, the site suggests the existence of a possible Roman estate which, in the medieval period, became the territory of a hamlet. This, however, remains a hypothesis.

Plandolit, in the municipality of L’Ametlla del Vallès, is already mentioned in 932 [

4] (pp. 172-175). This site was inhabited in the Carolingian period, and likely also earlier, during the Andalusi period. It lies very close to the boundary separating flat agricultural land from wooded terrain (indeed, the area is still known as the forest of Can Plandolit); in fact, the Can Reixac stream, which flows 50 m east of the farmhouse, marks the division between the two. In this case, moreover, the layout of the pathways and the cultivated fields follows pre-medieval patterns of land partition. We may assume that at least 80 hectares belonged to lands dependent upon the

vilar of Plandolit. Approximately, Plandolit today comprises 50 hectares of cultivated land and, to the east, roughly 30 hectares of woodland. Although we cannot know precisely what this landscape was like a thousand years ago, we can be confident that many of its structural components —certain paths, property boundaries, and an area partly agricultural and partly wooded— were already in existence, perhaps in a form not too dissimilar from that visible in mid-twentieth-century aerial photography.

While the previous three cases suggest hamlets established at the location of earlier estates, Salallacera almost certainly brings us closer to a hamlet created during the Early Middle Ages (

Figure 9). In 961, land, partly cultivated and partly uncultivated, located in the district of Llacera (Sant Llorenç Savall), at a place known as

Sales, was sold [

4] (pp. 153-156) [

29] (p. 445). At this site, there were cultivated plots, vineyards, and fruit trees. In modern times, this putative hamlet became a single farmhouse (

mas), comprising 5.5 hectares of arable land, largely arranged as terraces or stepped fields, spread across a ground with an elevation difference of over 70 m. Determining exactly when these terraces were constructed is difficult. In the tenth century, the present terraces may have been (i) simply sloping land without any stone or earthen retaining walls; (ii) ground with small embankments and terraced plots on a steep incline; or (iii) terrain already closely resembling what may be observed in mid-twentieth-century aerial images. Based on the excavations carried out to date, we may tentatively favour one of the latter two possibilities. Moreover, the lands associated with this ‘Sala’ within the district of Llacera plausibly extended over about 140 hectares, mostly consisting of woodland.

This section has approached the study of hamlets from several angles. The combination of information derived from different sources is, we believe, essential. Some hamlets ultimately became villages; others are now single farmsteads; and others still survive as hamlets (despite the major transformations of recent decades). Numerous examples may be found by examining the settlement pattern of the parishes of Andorra [

36] (p. 35). Within the parish of Sant Julià de Lòria, the southernmost of them, there still exist the hamlets of Juberri, Auvinyà, Aixirivall, Nagol, Certers, Llumeneres, Fontaneda, Bixessarri, Aixàs, Aixovall, Pui d’Olivesa, and Tolse. Furthermore, if we wish to deepen our understanding of the origins of these sites, the contribution of toponymic research must be considered: Auvinyà is a Roman name, Juberri and Bixessarri are Basque in origin, and Llumeneres (meaning ‘boundary’) is Romance in origin [

25].

3.3. The Farmstead: A House with Agricultural and Forest Land

To understand how the landscape across a significant part of Catalonia was organised, it is essential to study farmsteads (

masos). This topic has interested me for many years. I excavated a

mas built in the tenth century and abandoned in the fourteenth century [

37], and I also produced a monograph on the distribution of farmsteads in the High Middle Ages within a parish of the

comarca or district of La Garrotxa [

38]. In municipalities where farmsteads predominated, settlement was dispersed. In the Girona region, in parishes such as Riudellots, Sant Cebrià dels Alls, Llambilles, or Montnegre, less than a quarter of the population lived in concentrated areas [

39] (p. 154). It must be noted that farmsteads are found on flat land, as in Osona, but we must also bear in mind that their creation enabled the occupation of large areas that had previously been forested; we shall examine some examples below. It is worth stressing that farmsteads were not built on very high ground and were not important in the New Catalonia (where, at most, they were constructed in spaces interspersed between territories belonging to nucleated villages). In this section, we shall approach farmsteads from various perspectives: first, on the basis of written documentation; second, through the results of archaeological excavations carried out in recent years; and third, through what is visible in today’s landscape.

Some years ago, I studied how the parish of El Sallent, in the municipality of Santa Pau (La Garrotxa), developed [

38]. In this parish, prior to the year 1000, there were likely eight or nine hamlets. During the eleventh century, some twenty-seven farmsteads were established. In the twelfth century, two

bordes (half-farmsteads) were added. Around the year 1300, a further six

masoveries were created, associated simultaneously with the holders of the farmsteads and with the lordship, in this case, the monastery of Banyoles. Each farmstead lay several hundred metres from the nearest one. Around the parish church, there were very few dwellings. We would find comparable spatial organization in neighbouring regions of Old Catalonia [

40,

41]. It should be noted that written sources also allow us to understand what kind of dwelling stood at the centre of a farmstead (

mas), especially for the later medieval centuries. Such documentation is valuable, for example, for identifying the emergence of peasant houses with an upper floor, which became more common in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries [

42].

Archaeology has greatly enhanced our knowledge of what the earliest farmsteads, built around the year 1000, were actually like. In recent years, archaeological excavations have been undertaken at several farmsteads: Vilosiu [

37], La Creu de Pedra [

43], and Sa Palomera [

44]. Frequently, these buildings were constructed against an outcrop of rock and consisted of two or three rooms, with stone walls and roofs of branches or stone slabs. They contained a hearth and, often, an oven. Beside the house stood livestock enclosures. Soon thereafter, farmsteads grew larger, with more rooms, and, as already noted, came to include an upper floor. The better-off peasants built tower-farmsteads, which were the precursors of the

masies of the later Middle Ages and of the Modern period.

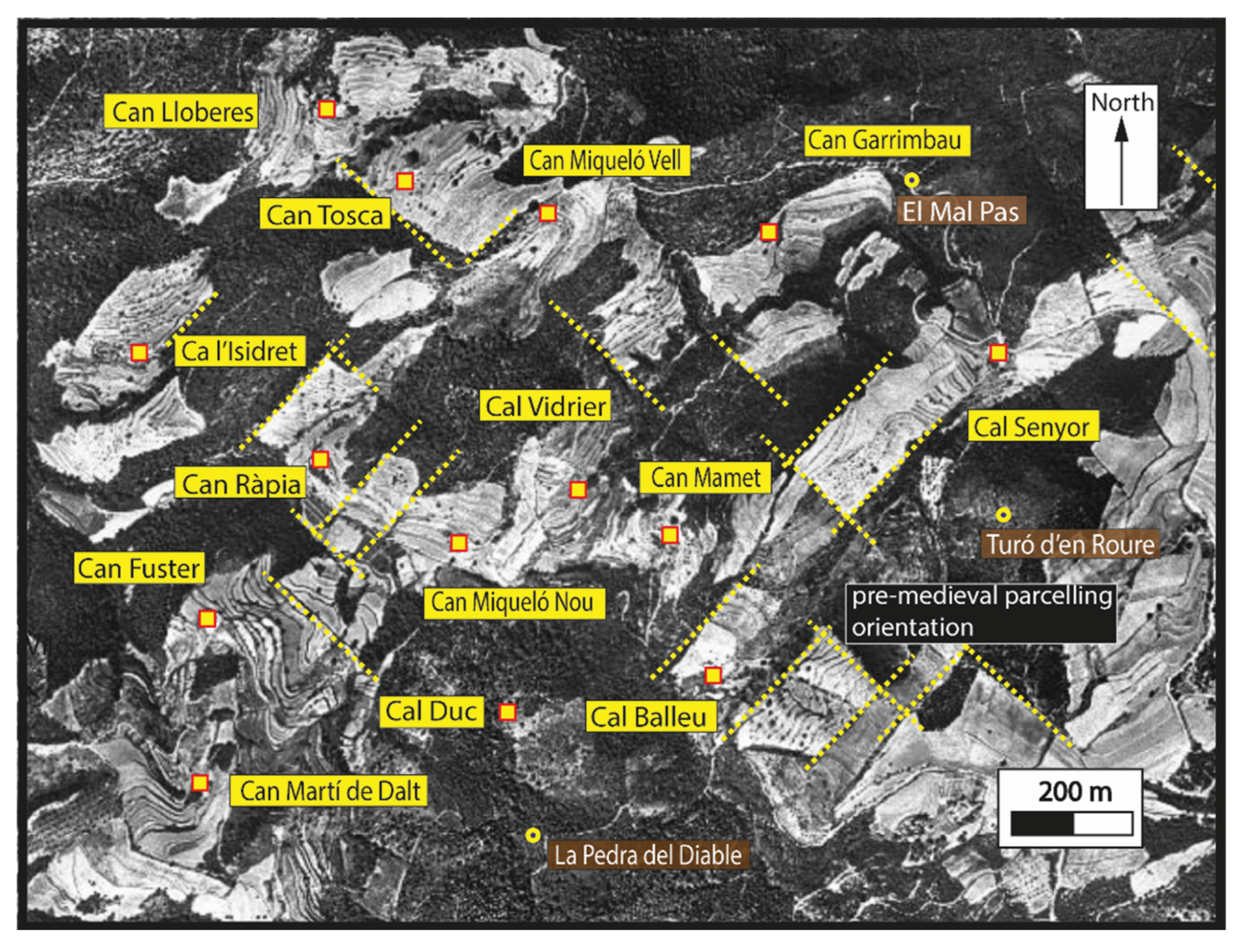

I wish to highlight what aerial photographs reveal. In the Vallès Oriental, there are places that deserve close attention because they reveal much about the formation of dispersed settlement. The area comprising Can Borra (

can means the house of), Cal Xiquet, Can Pere Piler, and Can Casavella, around the mid-twentieth century, was full of fields, terraces, and above all, woodland; this remains largely true today (

Figure 10). Unlike many other parts of this region of the Vallès, this area has been only slightly modified. A close examination reveals a striking reality. To the west of this zone, the fields and the boundaries of wooded areas predominantly follow alignments that coincide with Roman-period land divisions [

4] (pp. 210-215). In this sector, we find the farmsteads Casavella and Can Pere Piler and, on the western edge, the farmhouse of Can Marquès, where significant Roman remains came to light. By contrast, in the eastern sector, the concentric field layouts observable there, together with the numerous terraced fields (braided or parallel-sided terraces) surrounding the locations of other farmsteads, are of great interest.

We are fully aware that we need to ascertain when all these farmsteads were constructed, as they profoundly altered this space while also making extensive use of features that had been present for many centuries. In principle, these farmsteads date from the High Middle Ages (c. 1000-1348), although it is very likely that earlier antecedents, already present in the Carolingian period, could be identified. In short, if we focus on two farmsteads, we observe that Can Borra is surrounded by fields laid out in concentric forms, whereas Casavella has fields laid out in quadrangular forms. The two are separated by only 270 metres. Around the farmstead of Can Borra, built on the western flank of the hill of that name, the cultivated landforms an initial ring enclosing an area of approximately 9.6 hectares. A second ring defines land extending across a further c. 11.2 hectares. Can Borra may be an eleventh-century mas, although it is very possible that an earlier hamlet existed on this site and subsequently fragmented into multiple farmsteads.

Let us consider another example located nearby, in the municipality of La Roca del Vallès (

Figure 11). In 1156, reference is made to a farmstead situated at the place called

Bellsolell (present-day Can Solei; a

solell denotes a south-facing slope). In 1211, a

capbreu lists 30 farmsteads, one of which was Guillem de Bellsolell’s farmstead [

4] (pp. 204-208). A

capbreu was a document where the confessions or acknowledgements of the peasants before the lords were recorded, to preserve proof of the existence of the lord’s rights. The same

capbreu also refers to the farmstead of Joan Gener, now Can Gener. The farmstead of Can Solei lies on slightly elevated ground, surrounded by fields oriented primarily according to a pre-medieval layout. At 265 m to the west of the farmstead runs the Valldoriolf stream. Despite possible differences, this territorial organisation resembles, for example, that found at Bosquerons or Bogunyà: an inhabited site facing a watercourse, bordered by strips of cultivated land, and with forested land behind. It is almost certain that a hamlet existed in the Early Middle Ages at the site of Can Solei or Can Gener.

It is precisely in this wooded area extending eastwards behind the present-day farmstead that three additional farmsteads —Can Masferrer, Can Ribes, and Can Font— were built, possibly in the eleventh century. All three were established beside small depressions that resemble shallow coombs. This circumstance led the cultivated land around them to take on more rounded, less linear shapes. Another point of interest is that each of these farmsteads comprises both cultivated land and woodland. In sum, as in the previous case, we can contrast a landscape that has pre-1000 antecedents with another landscape that was almost certainly organised after that date.

3.4. The Settlements on the Other Side of the Border

In the study of medieval Catalonia, it is standard practice to distinguish between ‘Old Catalonia’ (

Catalunya Vella) and ‘New Catalonia’ (

Catalunya Nova) [

45]. The territory considered ‘old’ corresponds, broadly speaking, to Carolingian Catalonia, which in the eighth and ninth centuries was divided into several counties. ‘New’ Catalonia consisted of regions that, between the ninth and twelfth centuries, remained under Islamic rule. Their principal centres were the cities of Lleida and Tortosa. The landscape of these western and southern regions differs somewhat, first because they are more arid. It must be recalled that between the area controlled by the Catalan counts and the territories under Islamic power lay a frontier zone. Written documents refer to a broad frontier belt —the

marches or borderlands of the various counties— where a greater concentration of castles was found, and where territory and, often, settlement itself were organized around these fortifications.

It must be acknowledged that we still know relatively little about settlement patterns, for example, in Lleida, during the Islamic period. In many instances, what we know derives from later documentation produced after the conquest carried out by the counts of Barcelona and Urgell. The textual evidence indicates that around the city of Lleida, there were

almúnies and tower residences. To date, only a few fortified habitation sites, the so-called towers (Arabic

abrag, plural of

burg) and several castles have been excavated. The most substantial excavations concerning this period have taken place within urban contexts, notably at Balaguer, Lleida, and Tortosa [

46,

47].

In what follows, to understand the evolution of the landscape, I shall outline the changes and continuities between the eighth and twelfth centuries, which will enable us to grasp the configuration of these lands under Islamic rule. We shall consider specific case studies. First, we shall focus on Matxerri (Les Garrigues), a case that highlights the importance of assessing continuity (

Figure 12). It must be borne in mind that, although substantial changes occurred in the Andalusi territories, these developments were gradual and did not entail a complete alteration of the landscape. In fact, a large share of the population living there before 713 —year in which the armies of Arabs and Berbers arrived— continued to inhabit the region afterwards. In approaching Matxerri, we shall make use of orthophotographic imagery. In this case, we shall also draw upon an additional source of information that is sometimes crucial: toponymy. According to Joan Coromines, the name Matxerri derives from the Latin

macĕrĭes, probably referring to rammed-earth walls [

25]. In fact, in Roman times, there were low walls that limited a space [

48] (p. 122). At present, what we see at this site is a long, dry coomb 5.1 km in length (within the municipality’s limits). The name and the area’s physical characteristics point to a landscape very probably created during the Visigothic period and only minimally altered in subsequent phases.

Secondly, we shall draw on archaeological evidence. The burials of the necropolis at Tossal de les Forques (La Noguera) are located along a ridge extending roughly 150 m, where thirty-eight tombs carved into the rock have been identified. According to radiocarbon dating, one of these graves must be placed in the second half of the seventh century, whereas another burial, containing the remains of a woman approximately forty years of age, seems to have been cut in the ninth century. It is therefore plausible that she was a Christian woman living under Islamic rule [

49] (pp. 141–145).

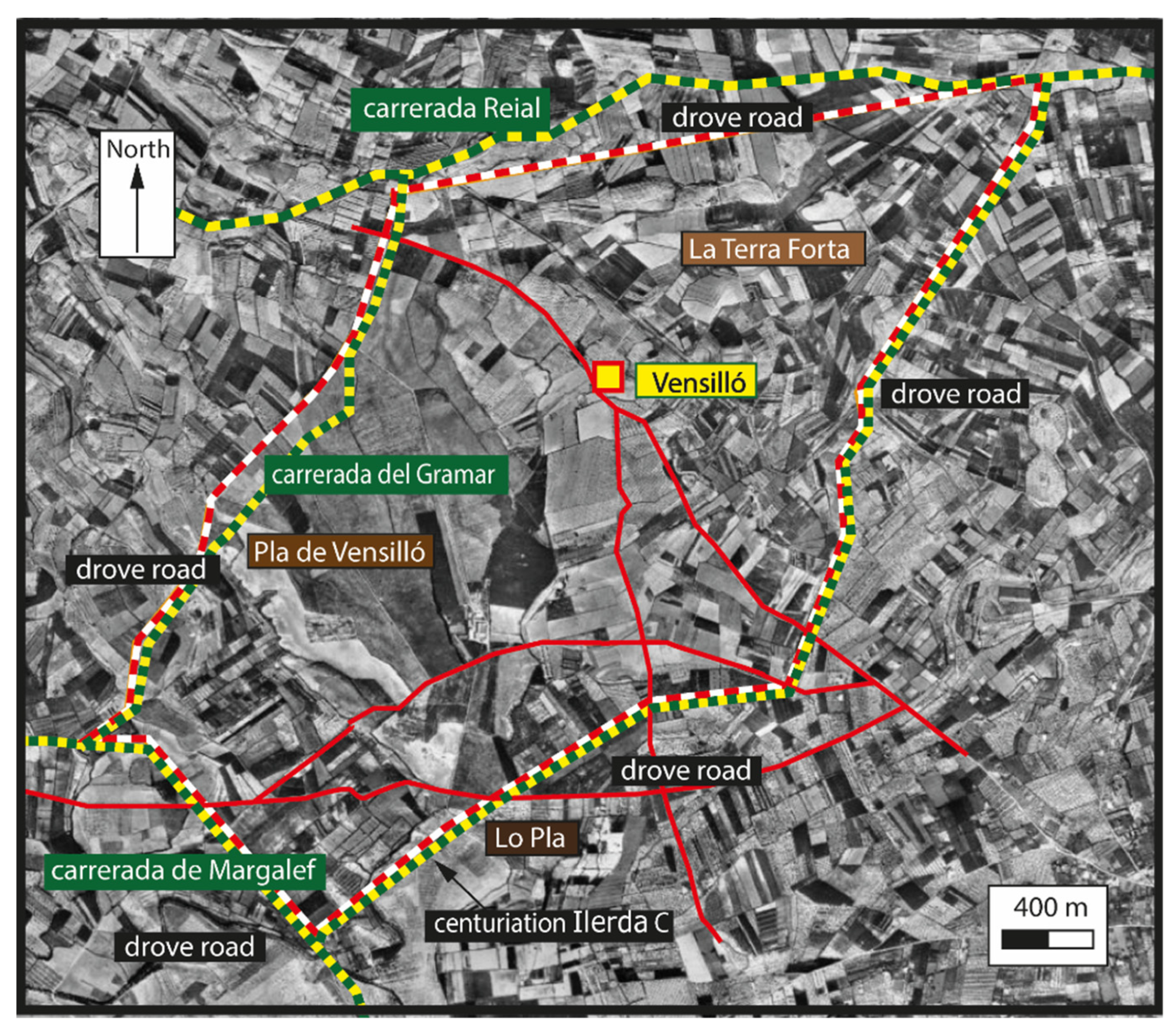

Even in these lands of so-called ‘New Catalonia’, we encounter the boundaries of rural territories whose origins appear to reach far back in time. Modern maps reveal areas whose perimeters seem to preserve very ancient limits, dating from the Andalusi period or, conceivably, even earlier. Vensilló is an enclave of the municipality of Els Alamús (Segrià) within the

comarca of Pla d’Urgell, covering an area of 7.6 km² (

Figure 13). According to Coromines, this toponym derives from the Arabic name Iben Sallûm [

25]. It is now irrigated land, but in the Middle Ages it was not. A study of its boundary lines reveals that they coincide with livestock paths, and some even follow pre-medieval orientations. We must assume that the community inhabiting this area devoted itself primarily to pastoral activities, which, as we know, were of considerable significance in these lands of the Lleida region [

50].

Archaeological excavations likewise allow us to reconstruct the context immediately preceding the conquest undertaken by the counts of Barcelona and Urgell. In this regard, the excavations conducted at Solibernat (Torres de Segre) and at Safranals (Fraga) have been fundamental. At Solibernat, the remains of a small fortified settlement (

burg or tower) were uncovered on the summit of an elongated hill, approximately 55 m long and 12 m wide. On both sides of the upper surface of the hill, there was a perimeter wall, and at each end rose rectangular towers. The site also contained several chambers used as dwellings, a storage area, and a space for livestock. This tower at Solibernat was constructed in the first half of the twelfth century [

51]. The site at Safranals, located near the river Cinca, displayed similar characteristics. Nevertheless, no excavation has yet been carried out of an unfortified settlement, neither of an

almúnia nor of an

alqueria.

We shall return later to hydraulic installations. Before closing this section, however, a clarification is required. Logically, to understand the landscape of New Catalonia, one must consider the crucial role of irrigation channels (séquies). Yet I must state from the outset that I would not dare to affirm that all small hydraulic systems —such as those found near the so-called clamors or reguers— were created after the eighth century, that is, during the centuries of Islamic rule. What can be asserted with certainty is that major canal systems —such as those of Fontanet, Alcarràs, and Segrià— were built in the Islamic period, transforming many hectares of land on both sides of the large rivers, such as the Segre.

It must be borne in mind that the vast majority of the population living in Lleida or Tortosa around the year 1100 consisted of descendants of families who had already settled there prior to the Islamic conquest of 713. We also know that the process of Islamisation was gradual, especially in regions situated near the frontier [

52,

53]. Likewise, we must consider that the population of New Catalonia under Islamic governance cultivated irrigated lands in part —particularly when the cities gained prominence and were able to organise extensive irrigated zones— yet that a substantial portion undoubtedly worked dry-farming land, as numerous written documents clearly attest. These were dry lands of the sort we would have found at Matxerri or those attested on the plains of Selgua, already on the right bank of the Cinca, in an Aragonese-speaking area very close to Monzón, where Catalan was spoken in the medieval period [

54] (p. 189). We must also remember that, as we have observed in the case of Vensilló, a significant share of the population must have depended on livestock raising.

3.5. Fields with History and Paths

To study and understand how fields were organized throughout the Middle Ages, it is essential to analyse several components of the landscape that display distinctive characteristics. First, one must assess the weight of the pre-medieval past, particularly the centuriations and the extent to which these early parcelled layouts continued to exert influence in later periods. Second, attention must be paid to the role of communication routes, which very often provide the basic framework for the structure of agricultural land. Third, concentric forms must be considered, as these reflect processes of territorial colonization and reorganization. Fourth, we must identify and attempt to date coaxial strips of arable land. Finally, we must consider the significance of irrigated areas, of valley bottoms or coombs (comes), and of terraces, which we shall examine in subsequent sections.

Understanding the relevance of centuriations in the Middle Ages is crucial for interpreting the characteristics of many communication routes. It is likewise fundamental if we wish to understand the configuration of certain municipal boundaries, as we observed in our discussion of Vila-sacra and Rupià or Ultramort. Indeed, these pre-medieval centuriations and parcel systems exercised substantial influence over the organization of cultivated spaces. Nonetheless, in many cases we cannot determine whether present-day configurations derive directly from transformations of the Roman period, or whether they are the product of indirect influences —for example, those stemming from pre-existing roads— and whether, in fact, individual land plots were laid out according to a specifically medieval plan.

In discussing fields, we wish to comment on a phenomenon observable across several regions and documented in other neighbouring countries. In some areas, aerial views reveal nearly circular, concentric forms inscribed in the landscape [

55] (p. 337) [

56]. These features indicate two things. First, they point to a process of territorial occupation radiating outward from a central point. Second, they imply that, prior to this land reorganisation, a phase of depopulation or abandonment of previously cultivated areas had occurred. In Catalonia, we can find many cases [

57]. We shall examine three examples, located in very different regions, which will in turn give rise to a variety of reflections.

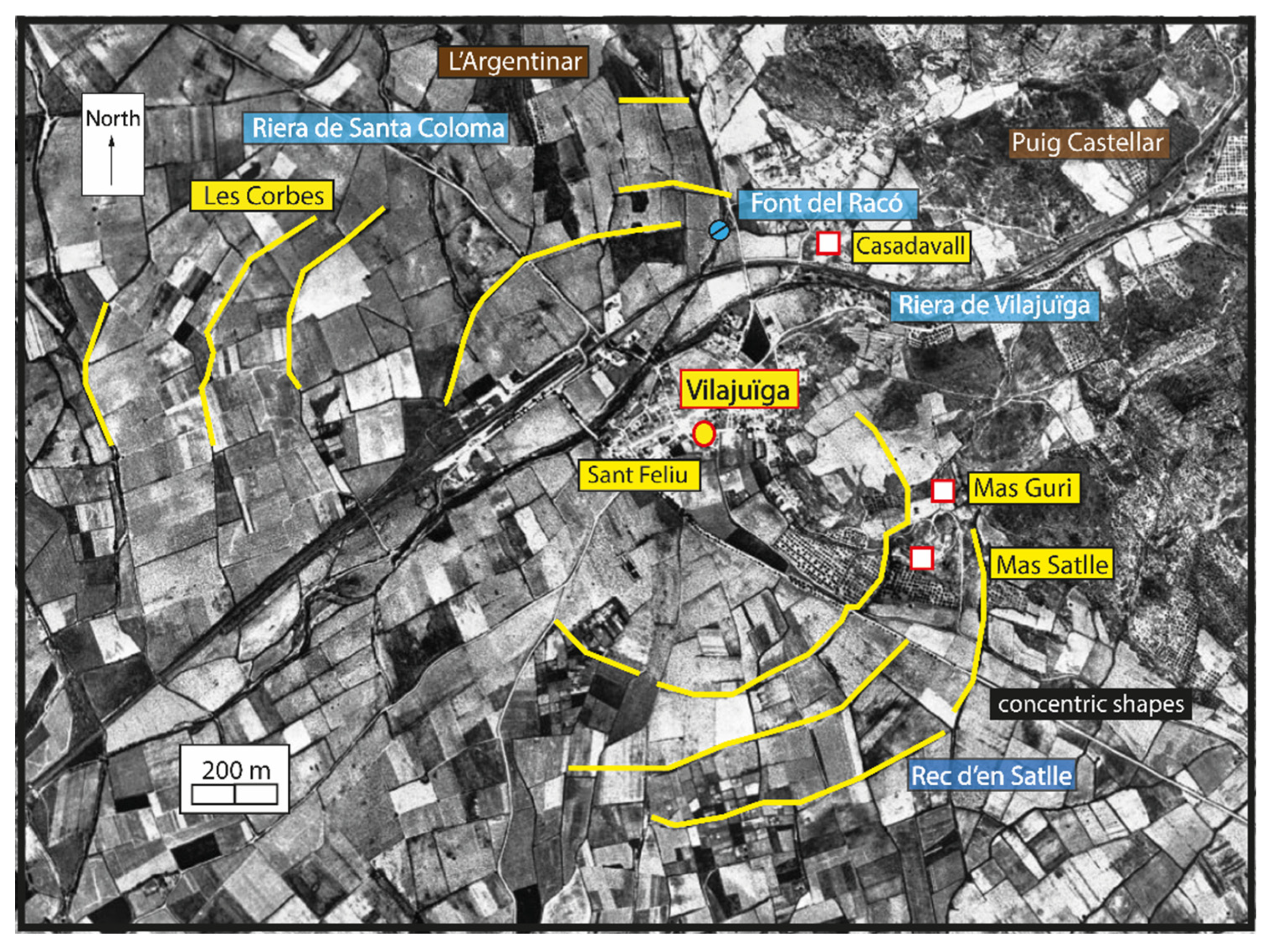

A first example takes us back to the Early Middle Ages. In the Alt Empordà district, in 982, the placename Vilajuïga (

Villa Iudaica) is attested, clearly designating a settlement that must already have existed for several centuries (

Figure 14). Its church was dedicated to Saint Felix (

Sant Feliu). The name of the settlement suggests that a Jewish community resided there at least by 785. This situation resembles that attested, for instance, some 170 km away in the border town of Cubelles, where several Jewish families lived during the tenth century (in 974 we find mention of

Iuda, ebreo, que vocant Vivas, filium Iacob, ebreo) [

34] (p. 584). We should note that in Vilajuïga several modern roads follow older alignments, very likely corresponding to pre-medieval parcel divisions. Moreover, both the Vilajuïga stream and the Garriguella stream share the same orientation as centuriation

Emporiae III. What concerns us most at present, however, is that —when observing the boundaries of fields and existing pathways— one finds concentric patterns surrounding the settlement. Particularly to the south-east and north-west, rounded field boundaries appear at approximately 500, 600, and 1000 metres from the centre of the village. Although this remains hypothetical, we may reasonably suppose that the spatial reorganization which generated these lines —now visible from the air— occurred in the early medieval centuries [

58]. It is evident that in Vilajuïga, elements from the Roman period, the Early Middle Ages, and the modern era coexist in the present-day landscape.

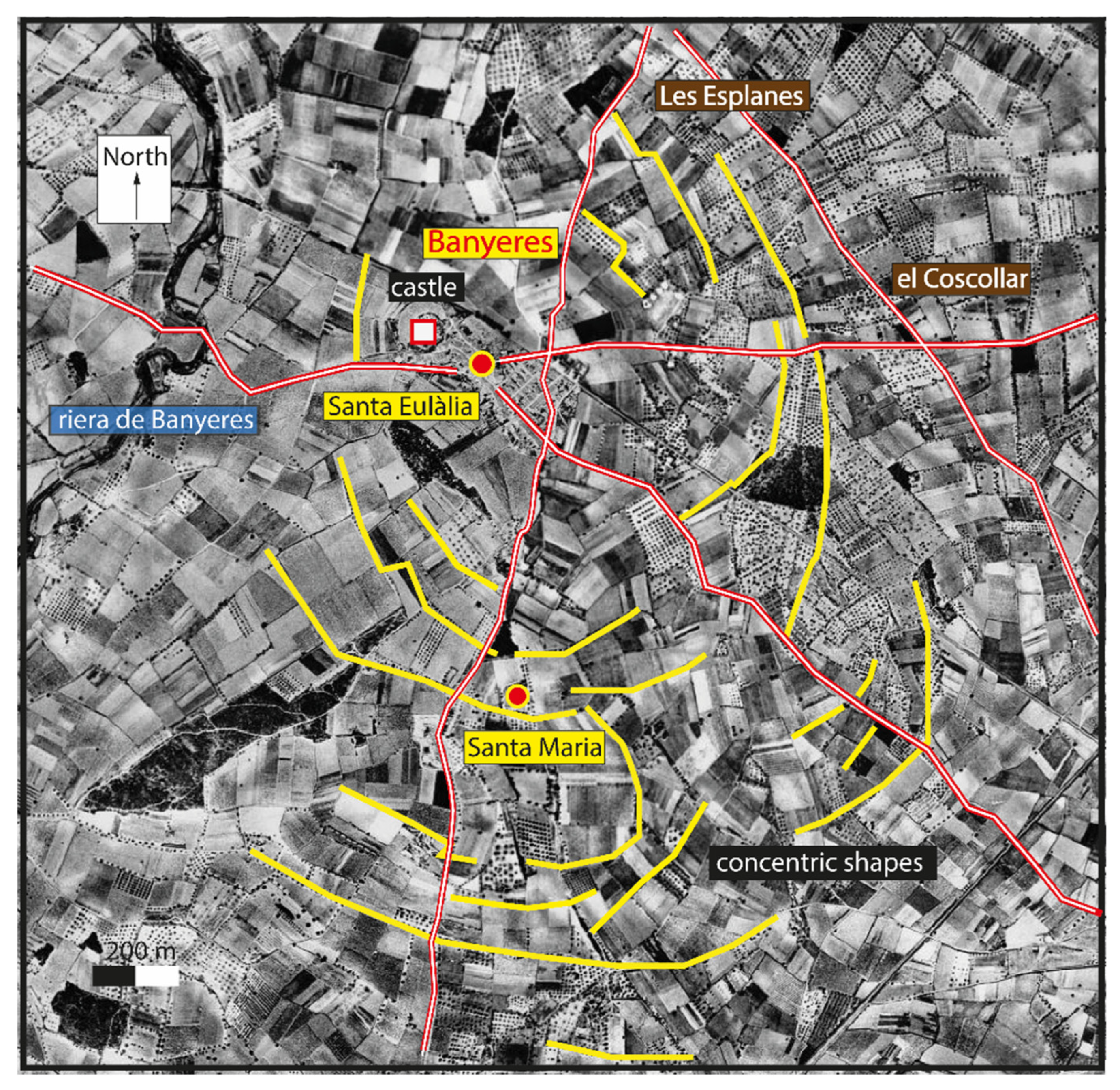

A second example brings us to around the year 1000. The Baix Penedès was conquered by the count of Barcelona at the end of the tenth century, although in certain parts of that territory control was not consolidated until the eleventh century. This situation almost certainly resulted in a period of depopulation. We must bear in mind that by this date, the population had undergone almost complete Islamisation, and as noted above, this population was largely descended from families already settled there prior to 713. At Banyeres del Penedès, old paths and traces of ancient parcel divisions are still discernible [

5] (p. 714) (

Figure 15). Furthermore, aerial photographs reveal several concentric lines around the site where the watchtower (and later the castle) was constructed, and where the church stood. The closest of these lies at approximately 600 m; others are visible up to 1,550 m away. These traces attest to a major territorial reorganisation, and this case is by no means unique. At another location, 3.8 km to the southwest, at Santa Oliva, documentary sources state —almost certainly with deliberate rhetoric— that in 1012, owing to Islamic raids, the site was fit only for pasture for onagers, deer, and other animals. This claim was surely exaggerated, yet it nonetheless illustrates the extent of abandonment that occurred over several decades in this region.

A third example is perhaps even more difficult to date. At the western edge of the Aragonese comarca of Baix Cinca, at Candasnos (called

Campdàsens in medieval records), we can still observe an agricultural area laid out with a network of radioconcentric routes, together with at least two paths encircling the land surrounding the settlement (

Figure 16). Various hypotheses have been proposed regarding the origins of this planned space [

59]. One is that it represents an Islamic-period layout. Another, more plausible hypothesis is that it corresponds to a scheme established around 1217, when these lands were granted to thirty-seven families. The existence of these routes allows us to identify several distinct rings. Within the first circle, with a radius of 400 m, lay the village itself, together with animal pens, threshing floors, and several ponds. In the second ring, extending to 1.1 km, were chiefly fodder crops destined for animal feed. In the third ring, with a maximum radius of roughly 2.6 km from the village, were the arable fields, arranged in radioconcentric strips. Beyond this area stretched, to the north, pastureland and, to the south, tracts of land reserved for communal use.

The strips of land constitute another landscape element with specific characteristics, and it is important to locate and study them. This is a complex issue, for which it is difficult to reach firm conclusions, and especially conclusions that can be generalised across different regions. In principle, these strips must also be understood in the context of a planned process of territorial occupation. A very interesting study on this subject has been conducted in the northern part of València, where these strips are related to the process of conquest during the thirteenth century [

60]. We can, however, affirm that some examples are considerably older, as we noted when discussing the place of Bosquerons, where a document from the year 989 mentions

fexa I de terra, a strip of level ground. Several examples will be discussed below, which I believe illustrate the complexity of this phenomenon. In fact, in Catalonia, we do not find examples of strips that extend over a large territory, but only strips resulting from the distribution of farmland [

48].

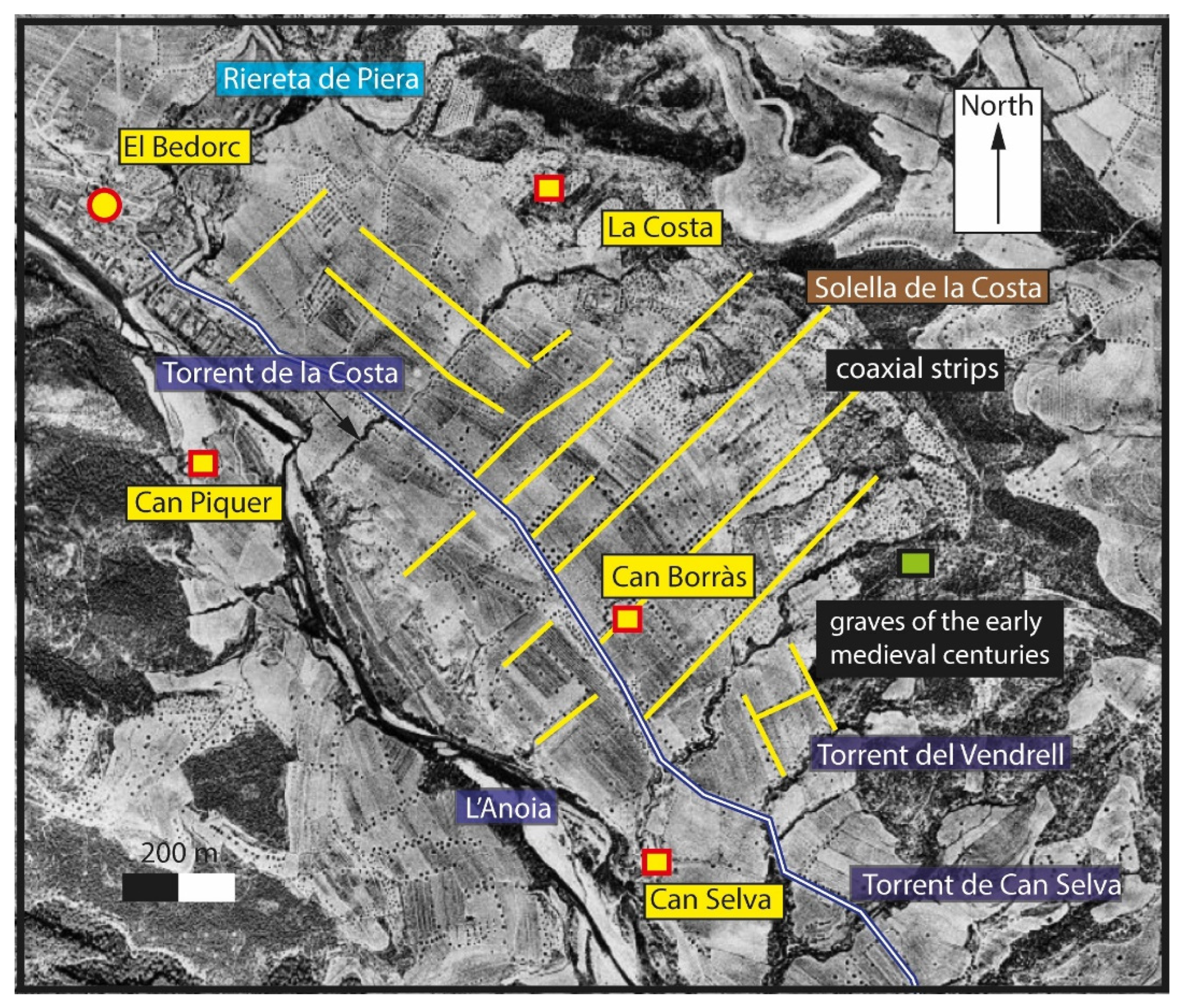

The slightly inclined slope on the left bank of the river Anoia, between Bedorc to the north and El Freixe to the south, presents a particularly interesting case (

Figure 17). The slope is divided by paths or banks running from the ridge down to the track near the river. These coaxial strips reach the crest of the ridge and therefore extend for roughly 600 m. In the upper sector, the most north-eastern part of the site, a series of braided terraces is present. The terraces and their embankments were constructed later, once the longitudinal strips had already been established. The traces left by these slope strips are striking: in some places their boundaries run along pathways; in others, along shallow ditches that have survived to the present day. These features served to prevent erosion and to channel water during storms, heavy rainfall, or flooding [

5] (pp. 597, 674). For this area, two hypotheses may be put forward, neither of which is necessarily incompatible with the other. One possibility is that these were colonisation strips laid out in the tenth century, when this area was taken over by the counts of Barcelona or their representatives. Supporting this hypothesis is the similarity with other cases we have studied in recent years, for example, in the Priorat region or

comarca. Moreover, the conquest here occurred unusually early (in the tenth century, not in the twelfth), and the remarkable regularity of the elongated plots suggests a carefully executed layout under the direction of a surveyor, an

agrimensor. Nonetheless, there is a document from the year 954 concerning El Freixe, in which the viscount of Barcelona grants this site, with cultivated and uncultivated lands, to fifteen individuals, permitting them to

ipsas terras qui sunt ductum partes Annolia faciatis exinde ortos aut quid de vos necessa fuerit exinde laborare, in the lands on both banks of the Anoia river, plant gardens (

horts) or whatever you need to cultivate [

34] (doc. 345). No reference, however, is made to strips of land, and it is likely that the lands granted were situated further south.

A second possibility is that these regular forms derive directly from the land divisions created here in Roman times, perhaps in the later Roman period or even during the early medieval centuries. In support of this hypothesis stands the fact that the stream known as La Costa follows the same orientation as the strips, suggesting that it may have been canalised when this entire land unit was organised. It is well known that many streams were canalised in the Roman period. Finally, the existence of burials, a necropolis of slab tombs —perhaps Visigothic in date—, to the south of these coaxial strips suggests that we cannot dismiss this second hypothesis, which would date the strips to the end of the Roman period or the Early Middle Ages. In fact, one may ask what landscape the viscount of Barcelona encountered in the tenth century when he assumed control of these lands. We may even hypothesize that part of the population had already lived there earlier. On this point, however, certainty is impossible.

In the

comarca of the Priorat, conquered by the count of Barcelona during the twelfth century, we find another interesting example of coaxial strips. The set of pieces of land of Llenguaderes is located within the municipality of Capçanes [

5] (pp. 268-271). Five strips of cultivated land may be identified, extending up the slope from the stream. Within each strip, three sectors can be distinguished: one measuring 170 m, flatter and closer to the watercourse; another of roughly 380 m, steeper and reaching the edge of the woodland; and a third of about 700 m, extending through the forest (visible in current cadastral maps). The strips measure between 80 and 130 m in width. It is likely that both these slope strips and those on the opposite hillside —known as

Les Sorts— should be dated to the phase of colonisation in the twelfth century. The toponym

Les Sorts relates to the manner in which land was distributed by lot among the new settlers.

In the place of Palofrets, in Olesa de Montserrat, two noteworthy features can be documented [

5] (pp. 606-609). First, the presence of an early medieval palace should be emphasised. In the year 920 [

34] (doc. 139), reference is made to

locum que vocant Palatio Fracto. These

palatia or

palatiola were fiscal estates created at the end of the Roman world, and which must have persisted during the Visigothic and Islamic periods. In this case, however, it was probably destroyed during the Carolingian conquest. Examination of aerial photographs taken in 1956 reveals six paths or ditches running south to north and converging as they rise the mountain slope. Several paths cross them, following the contour lines. This layout resembles what we find at Sant Miquel de Martres (municipality of Caldes de Montbui), a location attested between 898 and 917 (

villam Martyres cum suis mancipiis) [

4] (pp. 551-554) [

34] (doc. 134). It is worth noting the toponym

Martres and, in this case, also the proximity of a site named

Pla de Palau, situated 1.3 km to the west. Although I believe that this spatial organisation —featuring strips that narrow as they ascend the slope— could be medieval, it is impossible to establish this with certainty. Chouquer mentions

flabellum-shaped, fan-shaped strips [

48] (p. 137), probably created in the High Middle Ages.

3.6. Irrigated Landscapes: Before and After the Eighth Century

As noted above, there has been a tendency to associate irrigated areas almost automatically with the Islamic period. We know that in the regions of Lleida and Tortosa, major canals (séquies) were constructed prior to the comital conquest in the mid-twelfth century, enabling extensive territories to be irrigated. Nevertheless, it is also certain that there must have existed hydraulic systems not created by Islamic settlers. It is therefore essential, when dating irrigation canals or ditches, to conduct a meticulous analysis and to pay close attention to both what written documentation states and what other nearby landscape features reveal.

We shall examine below several examples of hydraulic systems that were very likely already in existence before the arrival of the Muslims. Many are in Old Catalonia, and some, though more uncertain, in New Catalonia. A particularly interesting case is that of the Rec Monar at Girona (

Figure 18). This canal was almost 6 km long and, according to photographs taken in the mid-twentieth century, irrigated approximately 1.5 km². A document from 833 already mentions

ipso rego (the ditch) next to the settlement of Salt (Gironès) [

26]. It is hardly plausible that this canal was created after 785, or even after 713 (the dates of Frankish and Islamic conquests); it is quite likely that it is older still. In the tenth century, we also find canals or ditches and irrigated lands in Roussillon and in the Vallès [

61]. In the latter region, along the river Ripoll, near Sant Vicenç de Jonqueres (municipality of Sabadell), there existed a series of small vegetable gardens (

horts), each covering roughly 2 hectares (and at most 6 hectares) [

5] (p. 646-654). There must have been small weirs, constructed with wooden elements and clay (known in Catalan and Occitan as

paixeres), which diverted water into irrigation ditches 200-500 m in length, enabling cultivation on both banks of the river. Each of these gardens was subdivided into small individual plots, forming coaxial strips, elongated and perpendicular to the canal. This is described in a document of 976, which refers to a

terra subreganea, measuring approximately 28.2 m in length (ten

destres) and around 5.6 m in width [

34]. These irrigated spaces are early medieval, perhaps created before 801, or possibly in the Carolingian period, when, as is well attested, a large number of flour-mills were built throughout Old Catalonia [

1].

We should not overlook the existence of certain small-scale hydraulic systems located around Barcelona, to the west of the river Llobregat, which are more likely to have been created during the period of Islamic rule. Noteworthy examples include those of La Gorgonçana and La Llacuna. In both cases, small, stepped gardens (

horts) were irrigated with water emerging from various springs [

5] (pp. 663-665). A similar origin is possible elsewhere, for example, at Magarola, also situated west of the Llobregat, which marked the frontier in 801 [

5] (pp. 658-662). At Magarola, in the municipality of Esparreguera (Baix Llobregat), there were several small, irrigated gardens. What is most striking is that the toponym itself seems to have been introduced following the Arab-Berber invasion and may relate to the Berber tribal group Maġrāwa

c, a branch of the Zanāta. These are merely hypotheses, which it is virtually impossible to establish with complete certainty. One further example deserves mention. At Sant Vicenç dels Horts, also on the left bank of the Llobregat, we find the so-called Rec del Poble, the village ditch [

5] (p. 278-283). Documentation indicates that it already existed in the tenth century and belonged to the count. Two possibilities arise: that it was a canal established in the Visigothic or Carolingian period, as we have seen on the river Ripoll, or that it dates from the eighth to ninth centuries, when Islamic authorities exercised control there. The oldest sector of the irrigated area could well pertain to this Muslim phase.

If in Roussillon, near Girona, and in the Vallès there existed irrigated lands not created in the Islamic period —and which, in some cases, may pre-date the eighth century— then it is highly probable that similar systems existed in the region of Lleida, a less rainy territory. To identify possible locations, I have sought places where present-day toponymy refers to a

reguer (a stream or a ditch used for irrigation) or a

clamor (a stream that roars during heavy rain). Today, these are often mere drainage channels for major canals; nevertheless, they are depressions through which water once flowed, and where irrigated areas must once have existed, as the very term

reguer implies. To the northeast of Lleida, an area traversed around the year 1000 by the Séquia de Segrià, there were several

reguers: the Reguer Gran, with tributaries such as the Reguer de la Mitjana, the Regueret, and the Reguer de l’Ull Roig [

62]. The first medieval irrigated areas were probably created around these channels. Furthermore, near both the Reguer Gran and the Reguer de la Mitjana, two major Visigothic cemeteries —Vimpèlec or Roca de Ço del Roig [

63] and Escalç— have been discovered. Thus, a close relationship can be established between these inhabited places of the sixth to eighth centuries and the network of watercourses known as

reguers. Similarly,

clamors may have served as water channels enabling irrigation prior to the construction of major Islamic canals. We may mention, for instance, the Clamor del Bosc and the Clamor de l’Agustinet (or of Coma Juncosa), which cross the Séquia d’Alcarràs, built most probably in the tenth century. It is therefore possible that irrigated areas adjacent to these

reguers and

clamors were cultivated and irrigated for the first time before the centuries of Islamic rule. In connection with North Africa, Gilbertson, and Hunt [

64] (p. 192) argue that the walls separating the different parcels of the

ʿāwdiya (plural of

wadi) may date from the Roman, medieval, or even modern periods. In the Segrià area, around Lleida, a similarly broad chronological framework must also be envisaged.

In Islamic Lleida, the major transformation began in the tenth century, when the cities of Al-Andalus once again assumed a central role in the organisation of the territory. Several irrigation canals are thought to have been constructed during this period. The most notable example is the Séquia d’Alcarràs, which drew water from the Segre River, east of the city of Lleida. The canal ran along the city walls, passed through Rufea and Butsènit, and extended as far as Alcarràs, covering a length of approximately fifteen kilometres. It enabled the irrigation of extensive gardens and powered mills, such as the one excavated on Blondel Street [

65]. It should also be noted that the toponym Rufea appears to derive from the Arabic word

rīhā, meaning ‘mill’ [

25]. This canal is already mentioned in a written document predating the conquest of Lleida: in 1147, reference is made to

ipsam turrem que fuit de Pichato, mauro (the tower that belonged to the Moor called Picato), located in the Alcarràs territory,

in ripam de ipsa cequia, on the bank of the ditch. The tower mentioned was also situated beside the Riera dels Reguers (or Torrent d’Alcarràs). Xavier Eritja has argued that the construction of this canal must have involved a ‘dialogue’ between the city’s public authorities and the various communities along its course [

66] (p. 32). The same can be said regarding other canals located near the city. In the tenth century, there must have been an agreement between the inhabitants of a city, increasingly governed by influential elites, and rural communities regarding the construction of major canals that fundamentally transformed the landscape.

On the opposite bank of the Segre, the Séquia de Fontanet was constructed, most likely also around the year 1000, with a length of approximately eight kilometres. It originated near the village of Alcoletge, passed through Grenyana and the area of Vinverme, and reached the land parcel of Fontanet, located opposite the city. The canal was used for irrigation by the inhabitants of the various settlements along its course as well as by the residents of the medina of Lārida (Lleida). Prior to the construction of the Séquia de Fontanet, and similarly to what can be observed along the Séquia d’Alcarràs, there must already have existed several smaller, older irrigated areas near the Nora (a toponym recalling a water wheel that must have existed there), in Alcoletge, towards Miralbò, in Grenyana, at the so-called Clamor de les Canals (where the Vilanova de l’Horta was later established), and beside the river of La Femosa.

The most notable —and perhaps also the latest— canal is the Séquia de Segrià (or Séquia Major), corresponding to the present-day Canal de Pinyana (

Figure 19). At the time of its construction, it must already have extended over more than thirty kilometres. It originated from a weir on the river Noguera Ribagorçana, north of Alfarràs, and flowed southwards, passing beneath Almenar and Alguaire, reaching the gardens (

hortes) situated north of the city of Lleida. Its construction altered both the dryland and irrigated plots along its course, erasing most of the parcel divisions previously created in relation to the various streams descending from the Sas, a flat highland to the west, used as pasture for livestock. Furthermore, the construction of the Séquia de Segrià likely prompted the establishment of new settlements, which, after 1149, came to be referred to as

almúnies or

torres (Arabic

abrāǧ, plural of

burğ, ‘tower’). For example, on the site of the Roman villa of La Tossa de Dalt, we find, in the Visigothic period, the necropolis (and settlement) of La Tossa de Baix, and during the Islamic period, the

almúnia of Alcanís was constructed, closer to the new Séquia de Segrià [

3] (pp. 45–46).

It is important to emphasise that, after the comital conquest of 1149, these major canals were not only utilised but also, in some cases, significantly extended. For instance, after 1149, the Séquia de Fontanet was lengthened by approximately 9.5 km. We also know that, further to the southwest, during the Islamic period, a small canal existed near Sudanell (likely meaning in Arabic ‘the weir of the small river’) [

25]. After the conquest, a new canal was constructed, originating opposite the city, and extending to Torres de Segre, with a length of nearly 15 km. However, the higher altitude of the new canal meant that the old Islamic settlement of Sudanell (now called

Vilavella, the old village) was abandoned, and a new settlement had to be established further up the river, as reflected in documents from the 12th and 13th centuries.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the so-called

illes or

insulae. This topic was first addressed by Ramon Martí [

67]. In Carolingian documentation, the term

insula is frequently used to denote a plot of land beside a river, often irrigated by capillary action. In fact, we probably need to look for a precedent in the Roman

insulae [

48] (p. 114). References to an

al-jazīra (‘island’) also appear in Tortosa during the Islamic period. In the Vallès region, along the banks of the Congost river, mid-twentieth-century aerial photographs revealed several garden plots immediately adjacent to the river, measuring 8.9 ha, 4.1 ha, and 9.7 ha from north to south [

5] (pp. 691-700). These plots have now disappeared. It is impossible to assert continuity over the centuries, given the frequent flooding, although it is reasonable to suppose that this type of irrigated land adjacent to watercourses persisted in this and other locations.

3.7. Coombs and Their Relationship to Settlements

Recent studies have demonstrated that coombs (Catalan comes) played a significant role in the consolidation of certain settlements during the early medieval centuries. Our understanding of these coombs can be enhanced through the study of medieval documents, the analysis of toponyms, and, above all, the examination of modern orthophotos. Equally important is the need to relate these coombs to other landscape features, such as roads, ditches, or medieval sites.

The Catalan term coma corresponds to the French combe or the Occitan comba and can be translated into English as coomb. In Catalonia, coombs are found both in the Pyrenees and in the drier territories of New Catalonia. These small valleys are scattered throughout the landscape. In high mountain areas, they often functioned as grazing grounds for transhumant cattle, as in the Coma de Vaca, located east of Núria, in the Ripollès comarca. In this study, however, we are primarily concerned with the coombs of New Catalonia. We contend that identifying and studying these coombs can significantly enhance our understanding of landscape transformations, particularly during the sparsely documented centuries of the Early Middle Ages. Several examples will be presented to illustrate the characteristics of coombs and to demonstrate the value of their study.

To the west of the Gaià River (Alt Camp), a mountainside is furrowed by a path running from Sant Pere de Gaià to Cabra del Camp. This road is ancient, dating back at least to the Roman period [

5] (pp. 781-789). On this slope, at least three coombs converge towards the lower end (

Figure 20). The western coomb covers an area of 7.5 hectares, the central coomb similarly spans approximately 7.5 hectares, and the eastern coomb, narrower, measures 6.0 hectares. Additionally, the southern end extends for approximately 5.9 hectares. The central coomb has a total length of roughly 1.6 km, with an elevation difference of about 56 m between its upper and lower extremities. Further east, there were still others. The plots within this coomb are approximately 50–60 m wide. Today, scattered farmhouses, likely constructed during the Late Middle Ages, are visible, alongside dispersed livestock enclosures.

A key document pertaining to this area dates from 1193 [

68] (doc. 361). It records an agreement between the abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Santes Creus and the archbishop of Tarragona, referring to new works (

novam laborationem) to be undertaken in the minor coomb (

minori cumba), located adjacent to the larger coomb (

maiorem et prolixiorem cumbam). The document indicates that cereals, vineyards, and olive trees were cultivated in these coombs. Moreover, it mentions the Coma de Gasc (

cumba de Gasc). This text not only attests to the existence of these coombs but also suggests ongoing efforts to expand them.

In a document written between 960 and 985, the place of Comallonga (

Chomalonga) is mentioned [

34] (pp. 768-770). It served as one of the boundaries of the castle district of Castellví de la Marca [

14] (pp. 104-105), which, as the name indicates, was a castle located at the border (

marca) of the county of Barcelona. Comallonga is a coomb, a strip of cultivated land extending along a valley floor [

5] (pp. 512-515). This coomb is 1.16 km long and covers an area of 3 hectares, with an elevation difference of approximately 50 m between its highest and lowest points. The coomb is divided into

parades (plots of land), each about 40 m long and 25–35 m wide, corresponding to the width of the coomb. At the lower end lies a farmstead still known as Comallonga. In the southern sector, the terrain becomes flatter, where traces of potential fossilised remains of the orthogonal land divisions from the Roman period can be observed. Near this farmhouse, there are also tombs plausibly dating to the Visigothic period.

Similarly, in the Penedès region, there is the so-called Coma Pineda (Alt Penedès) [

5] (pp. 527-530). In 992, a document mentions

ipsa Pineda and

ipsa comba Luposa [

34] (doc. 1.150). The name Coma Pineda survives to this day, referring to an area once covered with pine trees. The principal coomb at this location is 1,360 m long and covers 2.6 hectares. Additionally, several terraces (

feixes) were present on the slopes. It is likely that a small settlement (

vilar) existed here in the tenth century. To the south of this coomb, another coomb occupied a site historically associated with wolves, now known as the Pujol dels Llops (the hill of the wolves).

The Coma de Barbó (Conca de Barberà) lies north of the municipal district of L’Espluga de Francolí. A land terrier from 1558 mentions the

Cavalleria de la Coma de Borbó (or

Barbó) [

69]. A

cavalleria refers to a knight’s fief, established in the eleventh or twelfth centuries, following the conquest of these lands by the Count of Barcelona. Coma de Barbó is one of several coombs in the area. This coomb is particularly long, approximately 4.2 kilometres, with a surface area of 38.3 hectares and an elevation drop of around 162 metres from the upper end near L’Argullol to the lower end at Barranc del Reguer (or Rasa de les Comes). It is approximately 70 metres wide, and the individual plots within it range from 40 to 70 metres in length. Several scattered farmhouses, likely constructed in the later medieval period, are situated nearby. When this territory was conquered around the eleventh century, this coomb and others were already established and valued by the newcomers.

At Comarquinal (Alt Penedès), there is a coomb approximately 2 kilometres long, covering around 7 hectares (

Figure 21). On the northern side, an additional arm of the coomb spans 1.6 hectares. The western end is at an altitude of 383 m, with a height difference of 83 metres relative to the eastern end. The plots, known as

parades, measure approximately 30 metres wide and 60 m long. The Comarquinal farmhouse is located roughly 60 m above the coomb. On the opposite side, there is a spring, the Font de la Mata. This toponym Comarquinal derives from

Coma Arquinald, named after a man who likely settled here around the year 1000. Nonetheless, it is certain that this small, elongated valley existed long before that date.

Although the majority of coombs are found in New Catalonia, some also exist in Old Catalonia. Examples include those near Sanata, at the foot of the Montseny [

5] (pp. 498, 502), and one near Sant Julià de Cerdanyola, which is approximately 1.5 km long with a considerable width of around 150 m. Similar coombs have also been documented in some areas of Aragon [

70]. Furthermore, in the Lleida region, we previously mentioned the long coomb of Matxerri, approximately 8.4 km in length (5.1 km within the municipal territory of Castelldans). This was by no means unique; roughly 2 km further south lies another coomb, the Vall de Melons (a valley of badgers, from the Latin

meles) [

25], which is also 8.3 km long. These coombs played a significant role in shaping the humanised landscape of the Early Middle Ages.

One of the most interesting aspects is the potential to relate these coombs to settlements in the early medieval period. Near some of these small valleys, remains of habitations and, particularly, tombs from the first medieval centuries can be found. It is also important to note, as previously mentioned, that the formation or consolidation of these more fertile coombs likely occurred during the cooler and wetter decades at the beginning of the Middle Ages. Erosion processes caused the accumulation of soil at the base of these valleys, which likely attracted populations who often settled alongside them.

3.8. Terraces and the Cultivation of Slopes

The presence of terraces (in Catalan,

feixes or

bancals) provides insight into the occupation of mountain slopes, often during periods of high demographic pressure or when, for security reasons, populations settled in elevated locations. It is noteworthy that recent studies have demonstrated the presence of terraces in the Early Middle Ages, and even in a pre-medieval period, as at Samalús. Excavations carried out in Galicia, in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, have been particularly important in this regard [

71]. Closer to home, in northern Cerdanya, excavations have also shown that terraces were constructed before 1000 [

72]. Additionally, I participated in luminescence analyses at various sites near Lleida, which allowed the dating of certain terrace margins to the High Middle Ages [

73,

74]. All of this contributes to a better understanding of many rural landscapes in Catalonia.

However, as with all the cases discussed previously, what is observed on the ground is rarely simple or self-evident. At each site, it is necessary to consider when terraces and their margins —typically constructed with large or small stones to retain soil— were created. Moreover, it must be noted that in locations where abandonment occurred, the rebuilding of terrace margins almost certainly led to the collapse of older walls, which were probably almost dismantled. It is also true that some terraces may have had uneven surfaces or margins constructed solely of soil, sometimes covered with grass, without stone or masonry. Indeed, as noted, in Catalonia some historical terraces lack walls entirely, whereas rubble or roughly cut ashlar walls are typical in other areas [

75].

Luminescence studies carried out in 2014 near Lleida demonstrated that while the terrace margins between Vilalta and Cabanabona (Noguera) dated to the thirteenth century, those beneath the castle of Mur (Pallars Jussà) were dated to the seventeenth century [

73]. It should be considered that these latter terraces were very likely rebuilt at that time, although this does not preclude the existence of earlier terraces in the Early Middle Ages that were abandoned and subsequently destroyed.

We will now examine several sites already inhabited in the Middle Ages, where it can be assumed that terraces and their corresponding margins were necessary from the outset to enable both habitation and cultivation. This does not allow for absolute certainty, but it provides a framework for evaluating the importance of terraces in Catalonia throughout the medieval period. We will focus on settlements, particularly on farmsteads (masos) and hamlets (vilars) mentioned in Carolingian documents.

We begin with several

vilars or hamlets in the Montseny Mountain. Documents from before the year 1000 mention several locations, such as Vilanova, La Nespla, Colldeter, Roters, and Cerdans. Today, these are farmsteads, but during the Carolingian period, they were likely populated centres inhabited by multiple families. As I argued in a previous study, settlement in this area was probably consolidated between 785 and 801, when it was a frontier region and Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, had not yet conquered Barcelona. Notably, some names are of Frankish origin, such as

Lotharius or Ludher (at Colldeter), a Gothic anthroponym, Rothari (at Roters), and a ‘vilanova’, which obviously has no relation to the new towns of the High Middle Ages [

5] (p. 343-355) (

Figure 22).

Aerial photographs reveal that all these sites consisted of braided terraces. In Vilanova, at least thirty-five terraces were visible in 1956; there were virtually no extensive plots (the largest terrace covered 0.2 ha). The total cultivated area was approximately 5 ha; the remainder was likely forested land. Indeed, in 923, the document mentions

Vila Nova cum terminis suis, with its territory [

5] (pp. 345-346). At the

villare Nespula (La Nespla), documented in the same year, there were 6.2 ha of arable land divided into 27 terraces, some of which were very long, reaching approximately 240 m in length. Several families likely resided in this hamlet [

5] (pp. 348-349). A similar situation is found at Colldeter (originally Coll de Loter), where around 40 terraces cover 4.2 ha. This settlement was located at an altitude of approximately 1,000 m [