Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

01 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Balkan Peninsula is a biodiversity hotspot where topographic and habitat heterogeneity have shaped genetic differentiation. Polyploidization significantly contributes to diversification within plant lineages, including the allopolyploid Veronica austriaca complex. We sampled 751 individuals from 50 Balkan and Central European populations belonging to the hexaploid V. austriaca and its putative diploid (V. dalmatica) and tetraploid progenitors. Diversity patterns were investigated through microsatellite markers (SSRs), plastid DNA sequences, ploidy estimations, morphological data and climatic niche differentiation analysis. Five lineages were detected within the complex according to nuclear DNA data. The plastid DNA haplotypes form two main groups that overall match those detected by SSRs data and could suggest that the hexaploid V. austriaca resulted from two different allopolyploid events. Our analyses evidence rapid and recent colonization of diverse mesic grassy habitats by an allopolyploid perennial herb across a large European scale. The enhanced dispersal abilities of the hexaploid V. austriaca (compared to its lower ploidy relatives) seem to result from higher genetic diversity and ecological niche differentiation, which may also be related to slight morphological differences of potential functional significance. Style length is a crucial character to distinguish diploids from polyploids, which may affect pollination biology within the complex.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. DNA Ploidy Level Estimations

2.3. Laboratory Procedures

2.3.1. DNA Extraction

2.3.2. SSR Amplification, Fragment Analysis and Genotyping

2.3.3. Plastid DNA Amplification and Sequencing

2.4. DNA Data Analyses

2.5. Morphometrics

2.6. Analyses Based on Climatic Variables

2.6.1. Species Distribution Models (SDMs)

2.6.2. Niche Comparison Analyses

3. Results

3.1. DNA Ploidy Level Estimations

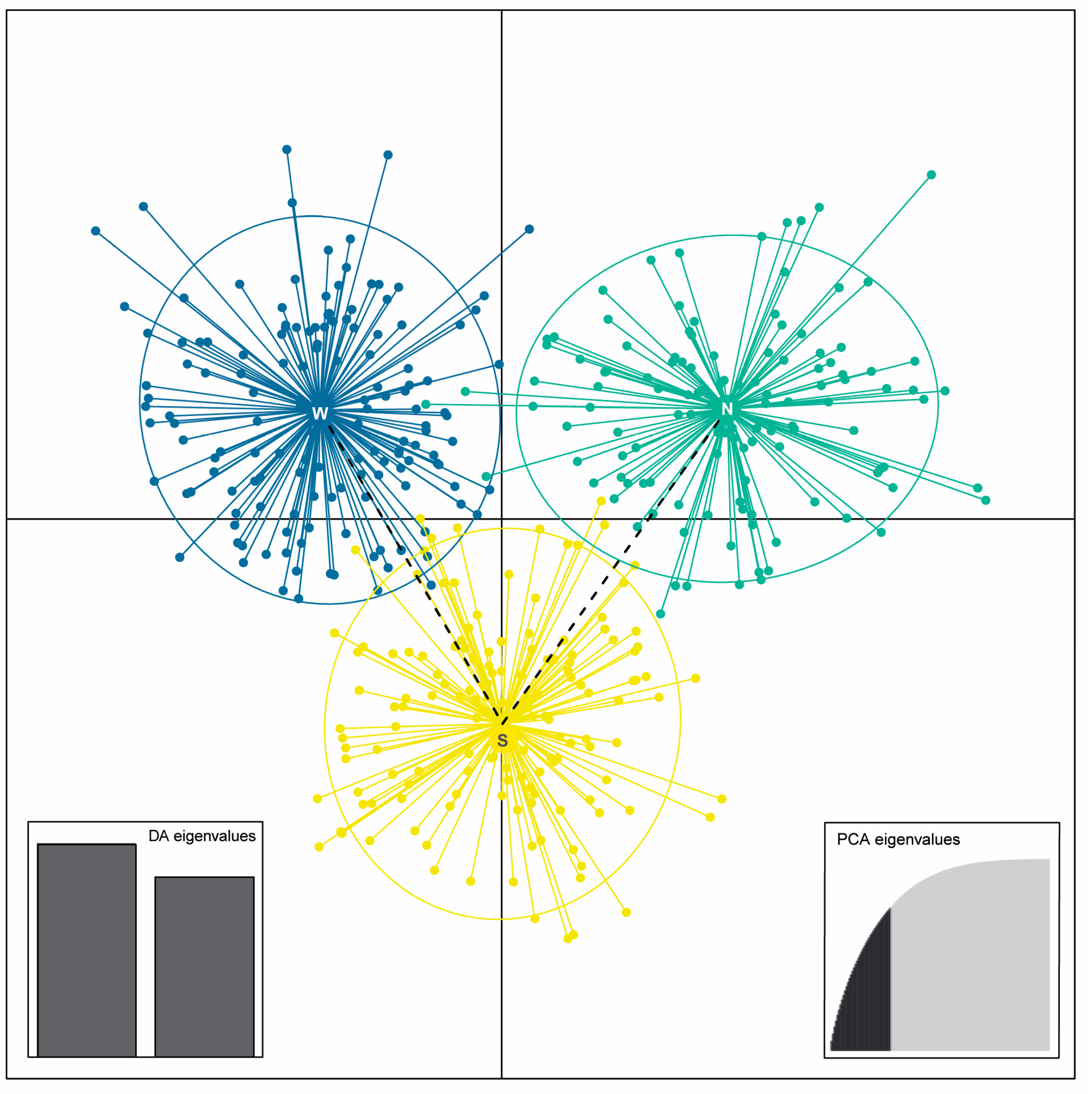

3.2. Genetic Structure and Population Differentiation Based on SSR Markers

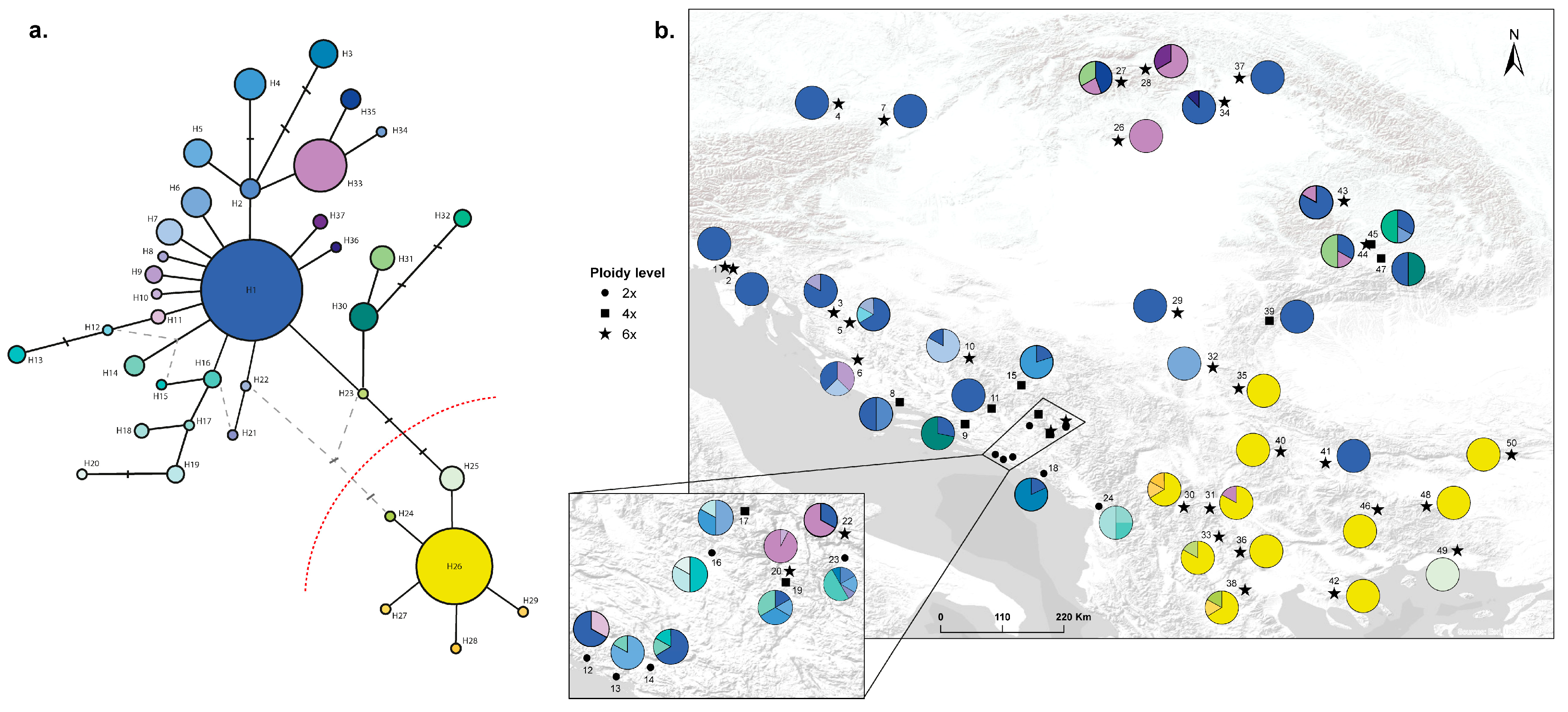

3.3. Analysis of the Plastid DNA Sequence Data

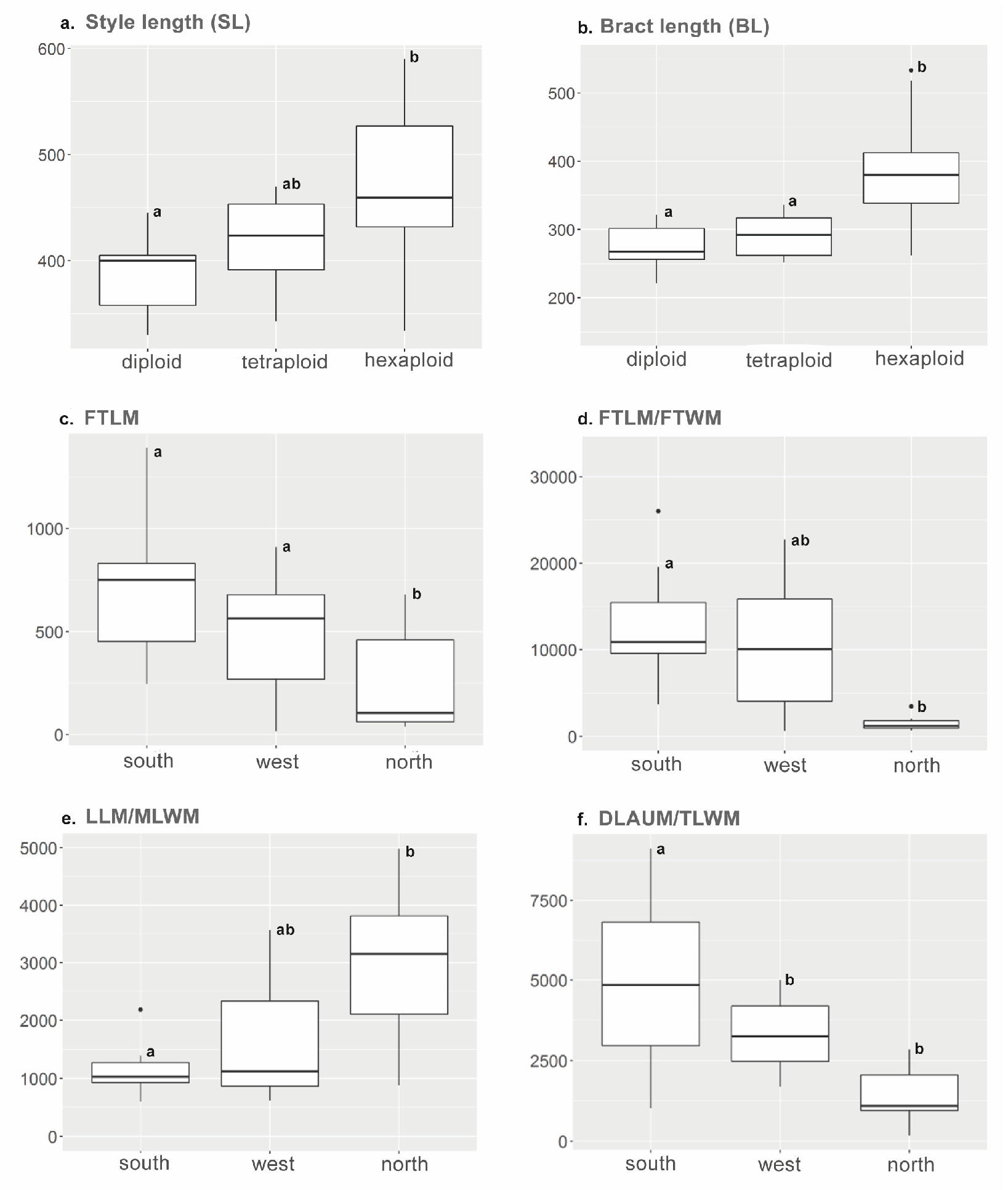

3.4. Morphometrics

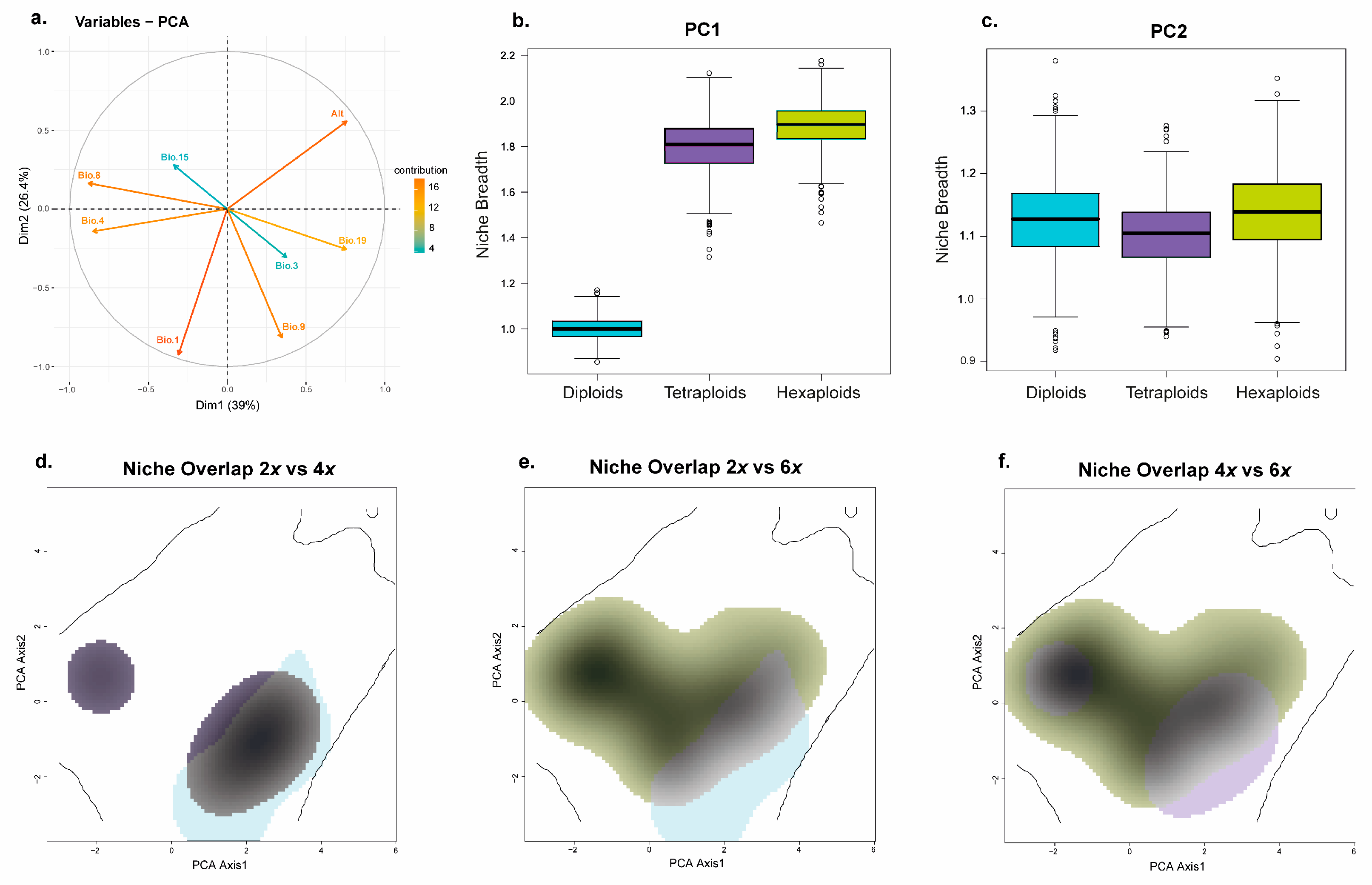

3.5. Analyses Based on Environmental Variables

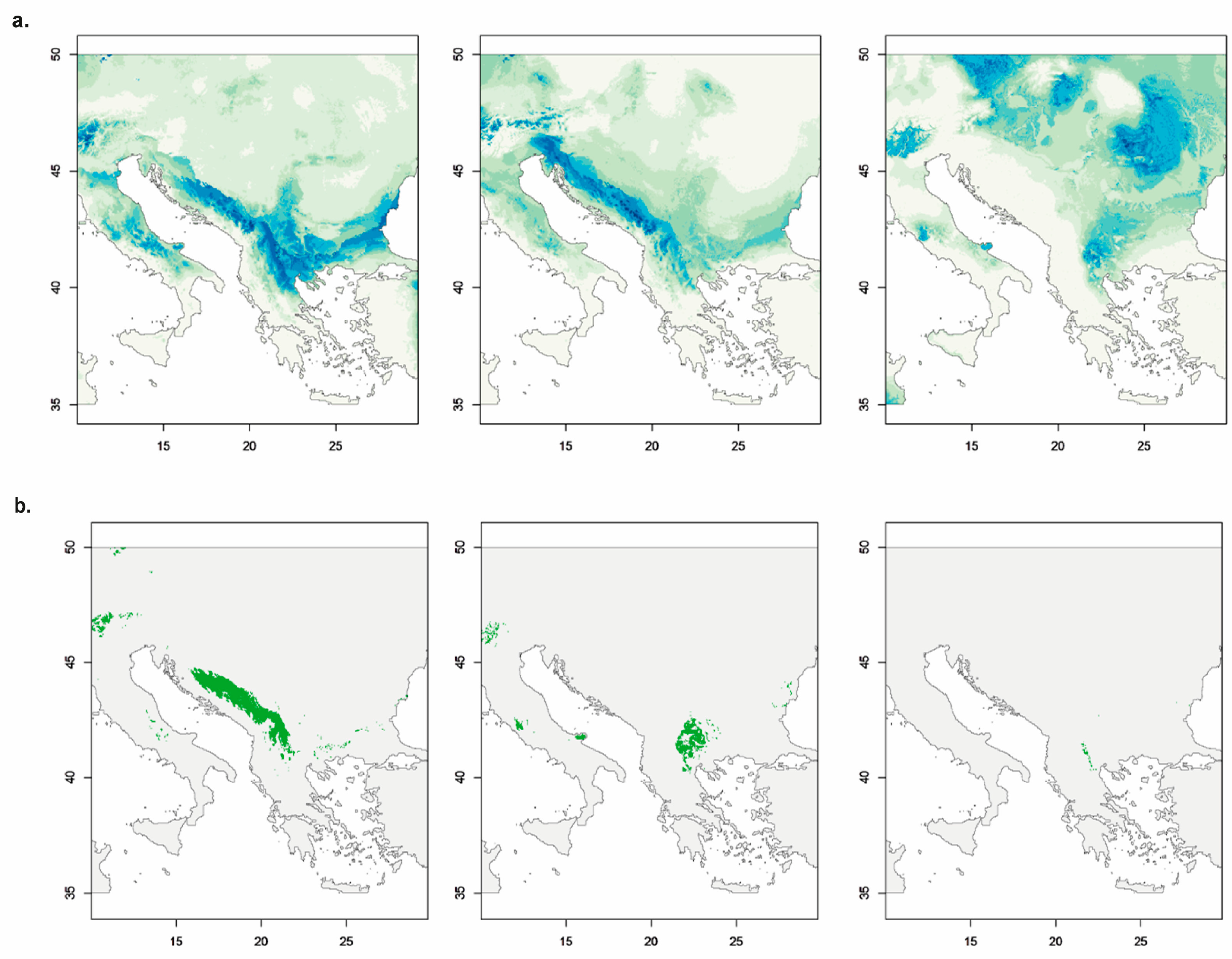

3.5.1. Species Distribution Models for the Three Genetic-Geographic Groups Found Within V. austriaca

3.5.2. Prediction of the Ecological Niche Optimum and Breadth for the Individuals from the Different Ploidy Levels

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic, Ecological and Morphological Variability of Veronica austriaca and Its Relatives

4.2. Phylogeography of V. austriaca

4.2.1. Putative Origin and Expansion of V. austriaca

4.2.2. The Balkan Peninsula as a Crossroad of Lineages

4.3. On the Importance of Allopolyploidy in the Colonization Abilities and Evolution of V. austriaca

5. Conclusions

6. Back Matter

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSR | Simple Sequence Repeat |

| FCM | Flow Cytometry |

| cpDNA | Chloroplast DNA |

| dNTP | Deoxynucleotide Triphosphate |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| DAPC | Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| RF | Random Forest |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ME | Maximum Entropy |

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve |

| AICc | Akaike Information Criterion corrected |

| P/O | Pollen/Ovule ratio |

| LGM | Last Glacial Maximum |

References

- Turrill, W.B.; 1. The Plant-Life of the Balkan Peninsula: a Phytogeographical Study; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G.M. Mediterranean Peninsulas: The Evolution of Hotspots. In Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas; Zachos, F., Habel, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.J. The vegetational history of the Balkans. Quat. Sci. Rev. 1994, 13, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryštufek, 4.; Reed, B.J.M. Pattern and Process in Balkan Biodiversity — An Overview. In Balkan Biodiversity: Pattern and Process in the European Hotspot; Griffiths, H.I., Kryštufek, B., Reed, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2004; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albach, D.C. Evolution of Veronica (Plantaginaceae) on the Balkan Peninsula. Phytol. Balc. 2006, 12, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, T. Molecular Biogeography of the High Mountain Systems of Europe: An Overview. In High Mountain Conservation in a Changing World; Catalan, J., Ninot, J.M., Aniz, M.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursenbacher, S.; Schweiger, S.; Tomović, L.; Crnobrnja-Isailović, J.; Fumagalli, L.; Mayer, W. Molecular phylogeography of the nose-horned viper (Vipera ammodytes, Linnaeus (1758)): Evidence for high genetic diversity and multiple refugia in the Balkan peninsula. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 46, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, G.L. Flowering Plants: Evolution Above the Species Level; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; Available online: https://biostor.org/reference/158513.

- Tzedakis, P.C. Museums and cradles of Mediterranean biodiversity. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakakis, N.; Kapli, P.; Lymberakis, P.; Trichas, A.; Vardinoyiannis, K.; Sfenthourakis, S.; Mylonas, M. A review of phylogeographic analyses of animal taxa from the Aegean and surrounding regions. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2015, 53, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podnar, M.; Bruvo Mađarić, B.; Mayer, W. Non-concordant phylogeographical patterns of three widely codistributed endemic Western Balkans lacertid lizards (Reptilia, Lacertidae) shaped by specific habitat requirements and different responses to Pleistocene climatic oscillations. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2014, 52, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psonis, N.; Antoniou, A.; Karameta, E.; Leaché, A.D.; Kotsakiozi, P.; Darriba, D.; Kozlov, A.; Stamatakis, A.; Poursanidis, D.; Kukushkin, O.; Jablonski, D.; Crnobrnja–Isailović, J.; Gherghel, I.; Lymberakis, P.; Poulakakis, N. Resolving complex phylogeographic patterns in the Balkan Peninsula using closely related wall-lizard species as a model system. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 125, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.C.; Schmitt, T.; Müller, P. The fourth paradigm pattern of post-glacial range expansion of European terrestrial species: the phylogeography of the Marbled White butterfly (Satyrinae, Lepidoptera). J. Biogeogr. 2005, 32, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronikier, M.; Cieślak, E.; Korbecka, G.; 14. High genetic differentiation in the alpine plant Campanula alpina Jacq. (Campanulaceae): evidence for glacial survival in several Carpathian regions and long-term isolation between the Carpathians and the Alps. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutnjak, D.; Kuttner, M.; Niketić, M.; Dullinger, S.; Schönswetter, P.; Frajman, B. Escaping to the summits: Phylogeography and predicted range dynamics of Cerastium dinaricum, an endangered high mountain plant endemic to the western Balkan Peninsula. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 15 78, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frajman, B.; Rešetnik, I.; Niketić, M.; Ehrendorfer, F.; Schönswetter, P. Patterns of rapid diversification in heteroploid Knautia sect. Trichera (Caprifoliaceae, Dipsacoideae), one of the most intricate taxa of the European flora. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016, 16 16, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajrudinović, A.; Frajman, B.; Schönswetter, P.; Silajdžić, E.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S.; Bogunić, F. Towards a better understanding of polyploid Sorbus (Rosaceae) from Bosnia and Herzegovina (Balkan Peninsula), including description of a novel, tetraploid apomictic species. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 178, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Španiel, S.; Marhold, K.; Zozomová-Lihová, J. The polyploid Alyssum montanum-A. repens complex in the Balkans: a hotspot of species and genetic diversity. Plant Syst. Evol. 2017, 18 303, 1443–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, A.; Hurka, H.; 19. Molecular systematics and biogeography of the Cardamine pratensis complex (Brassicaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2000, 224, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trewick, S.A.; Morgan-Richards, M.; Russell, S.J.; Henderson, S.; Rumsey, F.J.; Pintér, I.; Barret, J.A.; Gibby, M.; Vogel, J.C. Polyploidy, phylogeography and Pleistocene refugia of the rockfern Asplenium ceterach: evidence from chloroplast DNA. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, M.C.; McKain, M.R.; Vela Diaz, V.; Zhong, J.; Hodge, J.C.; Hodkinson, T.R.; Layton, D.J.; Malcomberg, S.T.; Pasquet, R.; Kellogg, E.A. Allopolyploidy, diversification, and the Miocene grassland expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15149–15154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.L.; Li, Y.-C.; Zhang, J.-Q. Allopolyploid origin and niche expansion of Rhodiola integrifolia (Crassulaceae). Plant Divers. 2023, 45, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.G.; Moraga, R.; Tausen, M.; Gupta, V.; Bilton, T.P.; Campbell, M.A.; Ashby, R.; Nagy, I.; Khan, A.; Larking, A.; Anderson, C.; Franzmayr, B.; Hancock, K.; Scott, A.; Ellison, N.W.; Cox, M.P.; Asp, T.; Mailund, T.; Schierup, M.H.; Andersen, S.U. Breaking Free: The Genomics of Allopolyploidy-Facilitated Niche Expansion in White Clover. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1466–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paape, T.; Akiyama, R.; Cereghetti, T.; Onda, Y.; Hirao, A. S.; Kenta, T.; Shimizu, K. K. Experimental and field data support range expansion in an allopolyploid Arabidopsis owing to parental legacy of heavy metal hyperaccumulation. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 565854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, J.K.; Martin, S.L.; Smith, T.W. Global biodiversity data suggest allopolyploid plants do not occupy larger ranges or harsher conditions compared with their progenitors. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Melton, A.E.; Soltis, D.E.; Soltis, P.S. Potential distributional shifts in North America of allelopathic invasive plant species under climate change models. Plant Divers. 2022, 44, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, R.; Sun, J.; Hatakeyama, M.; Lischer, H.E.L.; Briskine, R.V.; Hay, A.; Gan, X.; Tsiantis, M.; Kudoh, H.; Kanaoka, M.M.; Sese, J.; Shimizu, K.K.; Shimizu-Inatsugi, R. Fine-scale empirical data on niche divergence and homeolog expression patterns in an allopolyploid and its diploid progenitor species. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 3587–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casazza, G.; Boucher, F.C.; Minuto, L.; Randin, C.F.; Conti, E. Do floral and niche shifts favour the establishment and persistence of newly arisen polyploids? A case study in an Alpine primrose. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcer, A.; Méndez-Vigo, B.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Picó, F.X.; 29. Tackling intraspecific genetic structure in distribution models better reflects species geographical range. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 2084–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Garzón, M.; Alía, R.; Robson, T.M.; Zavala, M.A. Intraspecific variability and plasticity influence potential tree species distributions under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payton, A.C.; Naranjo, A.A.; Judd, W.; Gitzendanner, M.; Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. Population genetics, speciation, and hybridization in Dicerandra (Lamiaceae), a North American Coastal Plain endemic, and implications for conservation. Conserv. Genet. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.D.; Briscoe, D.A. An Introduction to Conservation Genetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yannic, G.; Pellissier, L.; Ortego, J.; Lecomte, N.; Couturier, S.; Cuyler, C.; Dussault, C.; Hundertmark, K.J.; Irvine, R.J.; Jenkins, D.A.; Kolpashikov, L.; Mager, K.; Musiani, M.; Parker, K.L.; Røed, K.H.; Sipko, T.; Pórisson, S.G.; Weckworth, B. V.; Guisan, A.; Bernatchez, L.; Côté, S.D. Genetic diversity in caribou linked to past and future climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, J.A.; Ritland, K.; Aitken, S.N. Widespread, ecologically relevant genetic markers developed from association mapping of climate-related traits in Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis). New Phytol. 2010, 188, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Andrés, B.M.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Taxonomic revision of Veronica subsection Pentasepalae (Veronica, Plantaginaceae sensu APG III). Phytotaxa 2016, 285, 1–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-García, N.; Rojas-Andrés, B.M.; López-González, N.; Castro, M.; Castro, S.; Loureiro, J.; Machon, N.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. The challenge of species delimitation in the diploid-polyploid complex Veronica subsection Pentasepalae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 119, 19–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, N.; Bobo-Pinilla, J.; Padilla-García, N.; Loureiro, J.; Castro, S.; Rojas-Andrés, B.M.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Genetic similarities vs. morphological resemblance: Unraveling a polyploidy complex in a Mediterranean biodiversity hotspot. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 155, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borissova, A.G. Veronica. In Flora of the U.S.S.R.; Shishkin, B.K., Bobrov, E.G., Eds.; Akademii Nauk SSSR: Moscow-Leningrad, Russia, 1955; pp. 293–439. [Google Scholar]

- Watzl, B. Veronica prostrata L., teucrium L. und austriaca L. Nebst einem anhange über deren nächsteverwante. Abh. Kais. Zool. Bot. Ges. Wien 1910, 5, 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer, H. Zur Polyploidie und Genetik der Veronica-Gruppe Pentasepala. Planta 1949, 37, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiers, B. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria and Associated Staff. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. Available online: http://sweetdum.nybg.org/ih/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Galbraith, D.W.; Harkins, K.R.; Maddox, J.M.; Ayres, N.M.; Sharma, D.P.; Firoozabady, E. Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science 1983, 220, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, J.; Rodriguez, E.; Doležel, J.; Santos, C. Two new nuclear isolation buffers for plant DNA flow cytometry: A test with 37 species. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doležel, J.; Sgorbati, S.; Lucretti, S.; 44. Comparison of three DNA fluorochromes for flow cytometric estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants. Physiol. Plant. 1992, 85, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsch, E.M.; Greilhuber, J.; Krisai, R. Genome size in liverworts. Preslia 2010, 82, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lysak, M.A.; Doležel, J. Estimation of nuclear DNA content in Sesleria (Poaceae). Caryologia 1998, 51, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greilhuber, J.; Ebert, I. Genome size variation in Pisum sativum. Genome 1994, 37, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doležel, J.; Greilhuber, J.; Lucretti, S.; Meister, A.; Lysák, M.A.; Nardi, L.; Obermayer, R.; 48. Plant genome size estimation by flow cytometry: Inter-laboratory comparison. Ann. Bot. 1998, 82, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Andrés, B.M.; Albach, D.C.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Exploring the intricate evolutionary history of the diploid–polyploid complex Veronica subsection Pentasepalae (Plantaginaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 179, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albach, D.C.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M.; Delgado, L.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H.; Özgökce, F.; Fischer, M.A. Chromosome numbers in Veroniceae (Plantaginaceae): Review and several new counts. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2008, 95, 543–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.; Rojas-Andrés, B.M.; López-González, N.; Padilla-García, N.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. IAPT/IOPB chromosome data 28. Taxon 2018, 67, 1235–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure from small quantities of fresh leaf tissues. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- López-González, N.; Mayland-Quellhorst, E.; Pinto-Carrasco, D.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Characterization of 12 polymorphic SSR markers in Veronica subsect. Pentasepalae (Plantaginaceae) and cross-amplification in 10 other subgenera. Appl. Plant Sci. 2015, 3, apps.1500059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuelke, M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Lickey, E.B.; Beck, J.T.; Farmer, S.B.; Liu, W.; Miller, J.; Siripun, K.C.; Winder, C.T.; Schilling, E.E.; Small, R.L. The tortoise and the hare II: Relative utility of 21 noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences for phylogenetic analysis. Am. J. Bot. 2005, 92, 142–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, T.; Crawford, D.J.; Stuessy, T.F. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1997, 84, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.A.; Simpson, B.B. Paraphyly of Tarasa (Malvaceae) and diverse origins of the polyploid species. Syst. Bot. 2003, 28, 723–737. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25063919.

- Dufresne, F.; Stift, M.; Vergilino, R.; Mable, B.K. Recent progress and challenges in population genetics of polyploid organisms: An overview of current state-of-the-art molecular and statistical tools. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 40–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, O.J.; Vekemans, X. SPAGeDi: A versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2002, 2, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coart, E.; van Glabeke, S.; Petit, R.J.; van Bockstaele, E.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. Range wide versus local patterns of genetic diversity in hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.). Conserv. Genet. 2005, 6, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, F.; Yang, R.; Boyle, T. POPGENE, version 1.32. Microsoft Windows-based freeware for population genetic analysis; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R. Spatial Data Science: With Applications in R, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, P.; South, A. rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth (Version 1.1.0.9000); R Package, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, A.; Michael, S.; Massicotte, P. rnaturalearthdata: World Vector Map Data from Natural Earth Used in 'rnaturalearth' (Version 1.0.0.9000); R Package 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

- Wickham, H.; Vaughan, D.; Girlich, M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data; R Package Version 1.3.1. 2025. Available online: https://tidyr.tidyverse.org.

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-L.; Liu, J.-X. STRUCTURESELECTOR: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software Structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelman, N.M.; Mayzel, J.; Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A.; Mayrose, I.; 70. CLUMPAK: A program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri. ArcMap (Version 10.5); Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jombart, T.; Devillard, S.; Balloux, F. Discriminant analysis of principal components: A new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet. 2010, 72 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jombart, T. Adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Warnow, T.J.; Holder, M.T.; Nelesen, S.M.; Yu, J.; Stamatakis, A.P.; Linder, C.R. SATe-II: Very fast and accurate simultaneous estimation of multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees. Syst. Biol. 2011, 61, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castresana, J. Gblocks: Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. v. 0.91 b. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002, 17, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingvarsson, P.K.; Ribstein, S.; Taylor, D.R. Molecular evolution of insertions and deletion in the chloroplast genome of Silene. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 1737–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A.R.; Crandall, K.A.; Sing, C.F. A cladistic analysis of phenotypic associations with haplotypes inferred from restriction endonuclease mapping and DNA sequence data. III. Cladogram estimation. Genetics 1992, 132, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. TCS: A computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1657–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, O.; Kauwe, J.S.K.; Mayo, K.; Morris, J.C.; Goate, A.M. Haplotype-based association analysis of the MAPT locus in Late Onset Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Genet. 2007, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, K.A.; Templeton, A.R. Empirical tests of some predictions from coalescent theory with applications to intraspecific phylogeny reconstruction. Genetics 1993, 134, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrés-Sánchez, S.; Rico, E.; Herrero, A.; Santos-Vicente, M.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Combining traditional morphometrics and molecular markers in cryptic taxa: Towards an updated integrative taxonomic treatment for Veronica subgenus Pentasepalae (Plantaginaceae sensu APG II) in the western Mediterranean. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 159, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.john-fox.ca/Companion/.

- Hijmans, R.J.; van Etten, J.; Sumner, M.; Cheng, J.; Baston, D.; Bevan, A.; Bivand, R.; Busetto, L.; Canty, M.; Fasoli, B.; Forrest, D.; Ghosh, A.; Golicher, D.; Gray, J.; Greenberg, J.A.; Hiemstra, P.; Hingee, K.; Karney, C.; Mattiuzzi, M.; Mosher, S.; Naimi, B.; Nowosad, J.; Pebesma, E.; Lamigueiro, O.P.; Racine, E.B.; Rowlingson, B.; Shortridge, A.; Venables, B.; Wueest, R.; Ilich; A; Institute for Mathematics Applied Geosciences. Package ‘raster’; R Package Version 3.0-12. 2015. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=raster.

- Hijmans, R.J.; Phillips, S.; Leathwick, J.; Elith, J. Package ‘dismo’; Circles. 2017. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dismo/dismo.pdf.

- Marquardt, D.W.; 85. Generalized Inverses, Ridge Regression, Biased Linear Estimation, and Nonlinear Estimation. Technometrics 1970, 12, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiberger, R.M. HH: Statistical Analysis and Data Display: Heiberger and Holland; R Package Version 3.1-34. 2017. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=HH.

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, B.D. Pattern Recognition and Neural Networks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Graham, C.H.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Ferrier, S.; Guisan, A.; Hijmans, R.J.; Huettmann, F.; Leathwick, J.R.; Lehmann, A.; Li, J.; Lohmann, L.G.; Loiselle, B.A.; Manion, G.; Moritz, C.; Nakamura, M.; Nakazawa, Y.; Overton, J.McC.M.; Peterson, A.T.; Phillips, S.J.; Richardson, K.; Scachetti-Pereira, R.; Schapire, R.E.; Soberón, J.; Williams, S.; Wisz, M.S.; Zimmermann, N.E. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.N.; Seo, C.; Thorne, J.; Nelson, J.K.; Erwin, S.; O’Brien, J.M.; Schwartz, M.W. Using species distribution models to predict new occurrences for rare plants. Divers. Distrib. 2009, 15, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Chung, N.; Hwang, S. Application of an artificial neural network (ANN) model for predicting mosquito abundances in urban areas. Ecol. Inform. 2016, 36, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, C.; Huettmann, F.; Guo, Y.; Han, X.; Wen, L. Why choose Random Forest to predict rare species distribution with few samples in large undersampled areas? Three Asian crane species models provide supporting evidence. PeerJ 2017, 5, e2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.M.; Lindgren, M.; Konakanchi, H.; Huettmann, F. Predicting the distribution and ecological niche of unexploited snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) populations in Alaskan waters: A first open-access ensemble model. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2011, 51, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Lek, S.; Ye, S.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; et al. Uncertainty in ensemble modelling of large-scale species distribution: Effects from species characteristics and model techniques. Ecol. Model. 2015, 306, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Georges, D.; Gueguen, M.; Engler, R.; Breiner, F.; Lafourcade, B.; Patin, R.; Blancheteau, H. Package ‘biomod2’: Species Distribution Modeling Within an Ensemble Forecasting Framework; R Package Version 4.2-6-2. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=biomod2.

- Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Boria, R.A.; Kass, J.M.; Uriarte, M.; Anderson, R.P.; 98. ENMeval: An R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for Maxent ecological niche models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J. Quantitative Methods for Modeling Species Habitat: Comparative Performance and an Application to Australian Plants. In Quantitative Methods for Conservation Biology; Ferson, S., Burgham, M., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. Worldclim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high-resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, N.; Barbosa, A.M. Common mistakes in ecological niche models. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 35, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broennimann, O.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Pearman, P.B.; Petitpierre, B.; Pellissier, L.; Yoccoz, N. G.; Thuiller, W.; Fortin, M. J.; Randin, C.; Zimmermann, N. E.; Graham, C. H.; Guisan, A.; 103. Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cola, V.; Broennimann, O.; Petitpierre, B.; Breiner, F.T.; D'Amen, M.; Randin, C.; Engler, R.; Pottier, J.; Pio, D.; Dubuis, A.; Pellissier, L.; Mateo, R.G.; Hordijk, W.; Salamin, N.; Guisan, A. ecospat: An R package to support spatial analyses and modeling of species niches and distributions. Ecography 2017, 40, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoener, T.W. The Anolis Lizards of Bimini: Resource Partitioning in a Complex Fauna. Ecology 1968, 49, 704–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-García, N.; Šrámková, G.; Záveská, E.; Šlenker, M.; Clo, J.; Zeisek, V.; Lučanová, M.; Rurane, I.; Kolář, F.; Marhold, K. The importance of considering the evolutionary history of polyploids when assessing climatic niche evolution. J. Biogeogr. 2023, 50, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, S.; Randin, C.; Broennimann, O.; Patsiou, T.; Conti, E. Divergent and narrower climatic niches characterize polyploid species of European primroses in Primula sect. Aleuritia. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchheimer, B.; Schinkel, C.C.F.; Dellinger, A.S.; Klatt, S.; Moser, D.; Winkler, M.; Lenoir, J.; Caccianiga, M.; Guisan, A.; Nieto-Lugilde, D.; Svenning, J.-C.; Thuiller, W.; Vittoz, P.; Willner, W.; Zimmermann, N. E.; Hörandl, E.; Dullinger, S. A matter of scale: Apparent niche differentiation of diploid and tetraploid plants may depend on extent and grain of analysis. J. Biogeogr. 2016, 43, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, K.J.; Andrew, R.L.; Bock, D.G.; Franklin, M.T.; Kane, N.C.; Moore, J.; Moyers, B.T.; Renaut, S.; Rennison, D.J.; Veen, T.; Vines, T.H.; 109. Recommendations for utilizing and reporting population genetic analyses: The reproducibility of genetic clustering using the program STRUCTURE. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 4925–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Wen, W.; Falush, D. Documentation for Structure Software: Version 2.3. 2010. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/group/pritchardlab/structure_software/release_versions/v2.3.4/structure_doc.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7051–7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Levy, A.A. Genome evolution in allopolyploid wheat-a revolutionary reprogramming followed by gradual changes. J. Genet. Genomics 2009, 36, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jump, A.S.; Marchant, R.; Peñuelas, J. Environmental change and the option value of genetic diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.C.H.; Kohn, J.R. Genetic and evolutionary consequences of small population size in plants: Implications for conservation. In Genetics and Conservation of Rare Plants; Holsinger, K.E., Falk, D.A.I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. DMEER: Digital Map of European Ecological regions. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/dmeer-digital-map-of-european-ecological-regions (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Rojas-Andrés, B.M.; Padilla-García, N.; de Pedro, M.; López-González, N.; Delgado, L.; Albach, D.C.; Castro, M.; Castro, S.; Loureiro, J.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Environmental differences are correlated with the distribution pattern of cytotypes in Veronica subsection Pentasepalae at a broad scale. Ann. Bot. 2020, 125, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, S.A. Differing Selection on Plant Physiological Traits in Response to Environmental Water Availability: A Test of Adaptive Hypotheses. Evolution 1996, 50, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennajeh, M.; Vadel, A.M.; Cochard, H.; Khemira, H. Comparative impacts of water stress on the leaf anatomy of a drought-resistant and a drought-sensitive olive cultivar. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, U.; Bonel, A.G.; David-Schwartz, R.; Degu, A.; Fait, A.; Cochard, H.; Peterlunger, E.; Herrera, J.C. Grapevine acclimation to water deficit: The adjustment of stomatal and hydraulic conductance differs from petiole embolism vulnerability. Planta 2017, 245, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Vigo, B.; Picó, F.X.; Ramiro, M.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Alonso-Blanco, C. Altitudinal and climatic adaptation is mediated by flowering traits and FRI, FLC, and PHYC genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1942–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Piedras, E.; Marcer, A.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Picó, F.X. Deciphering the adjustment between environment and life history in annuals: Lessons from a geographically-explicit approach in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfennig, D.W.; Pfennig, K.S. Character Displacement and the Origins of Diversity. Am. Nat. 2010, 176, S26–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ortega, M.M.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.; Rico, E. Palynological study of Veronica Sect. Veronica and Sect. Veronicastrum (Scrophulariaceae) and its taxonomic significance. Grana 2000, 39, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Agudo, J.A.; Rico, E.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.; Martínez-Ortega, M.M. Pollen morphology in the genus Veronica L. (Plantaginaceae) and its systematic significance. Grana 2009, 48, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruden, R.W. Pollen grains: Why so many? Plant Syst. Evol. 2000, 222, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.M.; Kryštufek, B.; Eastwood, W.J.; 126. The Physical Geography of the Balkans and Nomenclature of Place Names. In Balkan Biodiversity: Pattern and Process in the European Hotspot; Griffiths, H.I., Kryštufek, B., Reed, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2004; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frajman, B.; Oxelman, B. Reticulate phylogenetics and phytogeographical structure of Heliosperma (Sileneae, Caryophyllaceae) inferred from chloroplast and nuclear DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 43, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mráz, P.; Gaudeul, M.; Rioux, D.; Gielly, L.; Choler, P.; et al. Genetic structure of Hypochaeris uniflora (Asteraceae) suggests vicariance in the Carpathians and rapid post-glacial colonization of the Alps from an eastern Alpine refugium. J. Biogeogr. 2007, 34, 2100–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachurska-Swakoń, A.; Cieślak, E.; Ronikier, M. Phylogeography of a subalpine tall-herb Ranunculus platanifolius (Ranunculaceae) reveals two main genetic lineages in the European mountains. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 171, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnariuc, A.; Bouchette, A.; Dedoubat, J.J.; Otto, T.; Fontugne, M.; Jalut, G. Holocene vegetational history of the Apuseni mountains, central Romania. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2002, 21, 1465–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönswetter, P.; Popp, M.; Brochmann, C. Central Asian origin of a strong genetic differentiation among populations of the rare and disjunct Carex atrofusca (Cyperaceae) in the Alps. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postolache, D.; Popescu, F.; Paule, L.; Ballian, D.; Zhelev, P.; Fărcaş, S.; Paule, J.; Badea, O. Unique postglacial evolution of the hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) in the Carpathians and the Balkan Peninsula revealed by chloroplast DNA. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surina, B.; Schönswetter, P.; Schneeweiss, G.M. Quaternary range dynamics of ecologically divergent species (Edraianthus serpyllifolius and E. tenuifolius, Campanulaceae) within the Balkan refugium. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Iatrou, G.; Bent, J. The Peloponnese; Gad Publisher: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanović, V.; Tan, K.; Petrova, A. Mapping the endemic flora of the Balkans — A progress report. Bocconea 2007, 21, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Glasnović, P.; Temunović, M.; Lakušić, D.; Rakić, T.; Grubar, V.B.; Surina, B. Understanding biogeographical patterns in the western Balkan Peninsula using environmental niche modelling and geostatistics in polymorphic Edraianthus tenuifolius. AoB Plants 2018, 10, ply064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmickl, R.; Paule, J.; Klein, J.; Marhold, K.; Koch, M.A. The Evolutionary History of the Arabidopsis arenosa Complex: Diverse Tetraploids Mask the Western Carpathian Center of Species and Genetic Diversity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolář, F.; Hájek, M.; Hájková, P.; Roleček, J.; Slovák, M.; Valachovič, M. Introduction to this special issue on the ecology and evolution of the Carpathian flora. Folia Geobot. 2018, 138 53, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardy, K.E.; Albach, D.C.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Fischer, M.A.; Schönswetter, P. Disentangling phylogeography, polyploid evolution and taxonomy of a woodland herb (Veronica chamaedrys group, Plantaginaceae sl) in southeastern Europe. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010, 57, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardy, K.E.; Schönswetter, P.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Fischer, M.A.; Albach, D.C. Extensive gene flow blurs species boundaries among Veronica barrelieri, V. orchidea and V. spicata (Plantaginaceae) in southeastern Europe. Taxon 2011, 60, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, J.C. Biogeography and evolution of Abies (Pinaceae) in the Mediterranean Basin: The roles of long-term climatic change and glacial refugia. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falch, M.; Schönswetter, P.; Frajman, B. Both vicariance and dispersal have shaped the genetic structure of Eastern Mediterranean Euphorbia myrsinites (Euphorbiaceae). Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2019, 39, 125459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, J.M.; Han, S.; Stefanović, S.; Dickinson, T.A. Widespread generalist clones are associated with range and niche expansion in allopolyploids of Pacific Northwest Hawthorns (Crataegus L.). Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 5484–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Foll, M.; Petit, R.J. Genetic consequences of range expansions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 144 40, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, D.; Chen, Z.J.; Pires, J.C. Epigenetic regulation of flowering time in polyploids. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 145 14, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meimberg, H.; Rice, K.J.; Milan, N.F.; Njoku, C.C.; McKay, J.K.; 146. Multiple origins promote the ecological amplitude of allopolyploid Aegilops (Poaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Ploidy |

Assignment to Clusters as Detected by SSRs |

Haplotype | Haplogroup | Sample Size | h |

| Pop. 1 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1 | Northern | 20 | 0.6885 |

| Pop. 2 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1 | Northern | 20 | 0.7066 |

| Pop. 3 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1 and H8 | Northern | 15 | 0.7452 |

| Pop. 4 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H1 | Northern | 14 | 0.7604 |

| Pop. 5 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1, H12 and H22 | Northern | 18 | 0.7205 |

| Pop. 6 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1, H7 and H9 | Northern | 17 | 0.7017 |

| Pop. 7 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H1 | Northern | 15 | 0.7494 |

| Pop. 8 | 4x | Cluster 4 | H1 and H2 | Northern | 16 | 0.6889 |

| Pop. 9 | 4x | Cluster 4 | H1 and H30 | Northern | 16 | 0.6314 |

| Pop. 10 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1 and H7 | Northern | 15 | 0.7062 |

| Pop. 11 | 4x | Cluster 4 | H1 | Northern | 6 | 0.6563 |

| Pop. 12 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H1 and H11 | Northern | 17 | 0.5828 |

| Pop. 13 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H5 and H14 | Northern | 15 | 0.5815 |

| Pop. 14 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H1, H14 and H15 | Northern | 15 | 0.5811 |

| Pop. 15 | 4x | Cluster 4 | H1 and H4 | Northern | 17 | 0.6500 |

| Pop. 16 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H13, H19 and H20 | Northern | 17 | 0.5542 |

| Pop. 17 | 4x | Cluster 4 | H4, H6 and H19 | Northern | 15 | 0.6865 |

| Pop. 18 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H1 and H3 | Northern | 20 | 0.4723 |

| Pop. 19 | 4x | Cluster 4 | H1, H4, H5 and H14 | Northern | 16 | 0.6846 |

| Pop. 20 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H10 and H33 | Northern | 20 | 0.6574 |

| Pop. 21 | 2x | Cluster 2 | - | - | 20 | 0.5335 |

| Pop. 22 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1 and H33 | Northern | 15 | 0.7380 |

| Pop. 23 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H2, H3, H5, H16 and H21 | Northern | 18 | 0.5428 |

| Pop. 24 | 2x | Cluster 2 | H16, H17 and H18 | Northern | 4 | 0.4668 |

| Pop. 25 | 2x | Cluster 2 | - | - | 20 | 0.5571 |

| Pop. 26 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H33 | Northern | 4 | 0.7374 |

| Pop. 27 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H31, H33 and H35 | Northern | 10 | 0.6749 |

| Pop. 28 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H33 and H37 | Northern | 20 | 0.7234 |

| Pop. 29 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H1 | Northern | 10 | 0.7140 |

| Pop. 30 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26, H28 and H29 | Southern | 20 | 0.7453 |

| Pop. 31 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 and H33 | Southern | 20 | 0.7384 |

| Pop. 32 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H6 | Northern | 18 | 0.6795 |

| Pop. 33 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H23 and H26 | Southern | 16 | 0.7186 |

| Pop. 34 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H1 and H36 | Northern | 20 | 0.6654 |

| Pop. 35 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 8 | 0.7135 |

| Pop. 36 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 15 | 0.6705 |

| Pop. 37 | 6x | Cluster 3 | H1 | Northern | 20 | 0.7168 |

| Pop. 38 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H24, H26 and H27 | Southern | 10 | 0.8098 |

| Pop. 39 | 4x | Cluster 5 | H1 | Northern | 20 | 0.6871 |

| Pop. 40 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 10 | 0.7087 |

| Pop. 41 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H1 | Southern | 10 | 0.8078 |

| Pop. 42 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 10 | 0.7384 |

| Pop. 43 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H1 and H33 | Northern | 20 | 0.7309 |

| Pop. 44 | 6x | Cluster 5 | H1, H31 and H33 | Northern | 9 | 0.5626 |

| Pop. 45 | 4x | Cluster 5 | H1, H32 and H34 | Northern | 17 | 0.7417 |

| Pop. 46 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 12 | 0.7333 |

| Pop. 47 | 4x | Cluster 5 | H1 and H30 | Northern | 20 | 0.6595 |

| Pop. 48 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 10 | 0.6628 |

| Pop. 49 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H25 | Southern | 10 | 0.7499 |

| Pop. 50 | 6x | Cluster 1 | H26 | Southern | 11 | 0.7306 |

| Character | Homogeneity Test(Levene’s p) | F | p (ANOVA) | Post-Hoc Test | 2x – 4x | 2x – 6x | 4x – 6x |

| SL | 0.2029 | 6.4 | **1 | Tukey HSD | 0.7005 | 0.006 | 0.0959 |

| BL | . | 17.7 | ***1 | Tukey HSD | 0.7730 | 0.00001 | 0.0005 |

| Character | Homogeneity test(Levene’s p) | F | p (ANOVA) | Post-hoc test |

V. austriacassp. jacquinii vs. V. dalmatica |

| SL | 0.246 | 7.6 | ** | Tukey HSD | 0.0084 |

| BL | 0.058 | 11.3 | ** | Tukey HSD | 0.0014 |

| Character | Homogeneity test(Levene’s p) | F | p (ANOVA) | Post-hoc test | S - N | W - N | W - S |

| FTLM | 0.4095 | 5.2 | * | Tukey HSD | 0.0459 | 0.0134 | 0.7640 |

| FTLM / FTWM | 0.2754 | 3.6 | * | Tukey HSD | 0.0391 | 0.4516 | 0.2875 |

| LLM / MLWM | 0.865 | 4.05 | * | Tukey HSD | 0.0295 | 0.0874 | 0.8524 |

| DLAUM / TLWM | 0.1838 | 12.9 | *** | Tukey HSD | 0.0003 | 0.3777 | 0.0062 |

| Algorithms | MaxEnt | RF | ANNs | GLMs | |||||||||

| lineages* | south | west | north | south | west | north | south | west | north | south | west | north | |

| BIO 08 | 50.8 | 8.69 | 43.90 | 24.07 | 40.87 | 25.35 | 48.24 | 8.29 | |||||

| BIO 15 | 35.45 | 85.9 | 33.23 | 43.76 | 30 | 43.75 | 32.59 | 90.95 | |||||

| BIO 19 | 13.75 | 85.7 | 22.86 | 58.9 | 29.13 | 63.7 | 19.16 | - | |||||

| BIO 12 | 5.41 | 32.16 | 30.89 | 0.76 | |||||||||

| Altitude | 14.3 | 41.1 | 36.3 | - | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).