1. Introduction

Polyimides (PIs), polyamides (PAs), and polyamide-imides (PAIs), as key classes of high-performance polymers, are of significant academic and commercial importance. Owing to their outstanding thermal and mechanical properties, along with the ability to tailor various characteristics, these polymers are among the most well-known and widely used. In addition to their widespread application in the (micro)electronics industry and aerospace engineering, they are also of considerable interest for producing highly thermostable coatings and filters for scrubbing harmful emissions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], gas separation and pervaporation membranes [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], optical devices [

10,

13,

14,

15], flexible transparent films for displays and solar cells [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], and stimuli-responsive materials [

10,

13,

21,

22,

23], and others [

10,

13,

20]. Furthermore, due to the unique structural features of their macromolecules, these polymers are attractive for the application in electroactive devices [

10,

24,

25,

26].

Traditionally, the synthesis of PIs, PAs, and PAIs has relied on polar aprotic solvents such as N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAA), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), or N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). Unfortunately, these widespread solvents are reprotoxic and cause serious eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. Classified under REACH as “Substances of Very High Concern” and subject to authorization, they are prime candidates for substitution in the chemical industry [

27,

28,

29]. Consequently, the need to adopt less hazardous and more environmentally benign solvents is becoming increasingly urgent and relevant.

In recent years,

N-butyl-2-pyrrolidone (NBP), also known under the trademark TamiSolve NxG (Eastman Chemical Company), has been actively promoted as a “green” alternative to NMP, DMAA, and DMF [

30,

31,

32,

33]. This dipolar aprotic solvent, characterized by a high boiling point (241 °C), high chemical and thermal stability, aligns with several principles of Green Chemistry. Its advantages include lower toxicity and reduced human exposure hazards, a bio-based origin, and enhanced biodegradability [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Furthermore, an environmentally benign synthesis of NBP has been developed that eliminates the need for ammonia or alkylamines [

37]. This method is based on Pd-catalyzed reductive N-alkylation and decarboxylation of renewable glutamic acid in an aqueous medium. NBP has been reported to serve as a highly effective substitute for NMP and other conventional dipolar aprotic solvents in the synthesis of various organic compounds [

32,

38,

39,

40,

41].

It is known that NBP possesses a dissolving capacity similar to that of NMP, DMAA, and DMF, indicating its potential for preparing homogeneous polymer solutions [

31,

35,

42,

43]. For this reason, it has been extensively studied as a “green” solvent for producing membranes and films from PIs [

28,

33,

44,

45,

46], fluoropolymers [

33,

42,

47,

48,

49], poly(ether)sulfones [

33,

50,

51], cardo polyetheretherketone [

49,

52], and other polymers [

33,

35,

53]. Moreover, a mixture of NBP and di(propylene glycol) methyl ether (1:1 w/w) has been successfully applied for casting self-healable waterborne coatings as well [

54]. These findings create favorable conditions for the broader adoption of NBP in the manufacture of various functional materials.

NBP has been thoroughly tested as a solvent for membrane fabrication. However, traditional polymer production methods still rely on toxic polar aprotic solvents that have significant negative impacts on the environment and human health. To date, only a limited number of publications have addressed polymer synthesis in NBP. The international patent [

55] describes the use of various improved N-alkyl-2-pyrrolidone solvents for dissolving or forming a wide range of polymers, including cellulose derivatives, polyamides, poly(amide/ester)imides, polyethers, polyesters, poly(ether)sulfones, and polyurethanes. Nevertheless, it presents only one example of polymer

formation in NBP: a low-molecular-weight PAI (Mw = 8,100 g/mol) obtained from trimellitic anhydride and 4,4’-methylenediphenyl diisocyanate. Furthermore, NBP/ionic liquid mixtures have been explored as alternatives to traditional solvents for synthesizing aromatic PAs [

56]. Although the polymers formed in these mixtures generally exhibit lower molecular weights, this approach is promising for the in situ manufacture of high-strength fibers directly from the reaction solution. A European patent application is dedicated to the preparation of polyimides in N-C₃₋₅ alkyl-2-pyrrolidone [

57]. The reaction proceeds via a two-step method involving poly(amic acid) (PAA) formation followed by chemical or thermal imidization. While the patent notes the high viscosity of the resulting PAA intermediates, it provides no data on the final PIs. Although PIs can also be obtained via the direct one-step high-temperature polycondensation of dianhydrides and diamines [

58,

59], there is only one report mentioning the use of NBP as a reaction medium for this method [

60]. The authors of that study compared the physical and gas-transport properties of the resulting PI membranes but did not provide a detailed analysis of the molecular weight characteristics of polymers obtained by different routes.

Despite successful attempts to utilize NBP as an alternative to traditional toxic solvents, the scarcity of data on polymer formation in this medium remains a significant challenge. Herein, we have studied the key features of PI, PA, and PAI synthesis in NBP as the reaction medium. Two distinct approaches to PI formation were investigated: one-step high-temperature polycondensation and the two-step process involving poly(amic acid) (PAA) intermediates. The effects of chemical and thermal cyclization of the PAA intermediate, as well as thermal imidization with azeotropic distillation, on the molecular weights of the polymers were examined. The versatility of NBP in one-step formulation of PIs with various structures was evaluated. PAs were obtained via low-temperature polycondensation of terephthaloyl chloride (TPC) with aromatic diamines. PAI synthesis was carried out from TPC, various tetracarboxylic acid dianhydrides, and diamines, using acetic anhydride and pyridine as the cyclization (imidization) mixture. The properties of the resulting PIs, PAs, and PAIs were systematically compared with those of polymers produced in conventional NMP.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Polyimide Synthesis

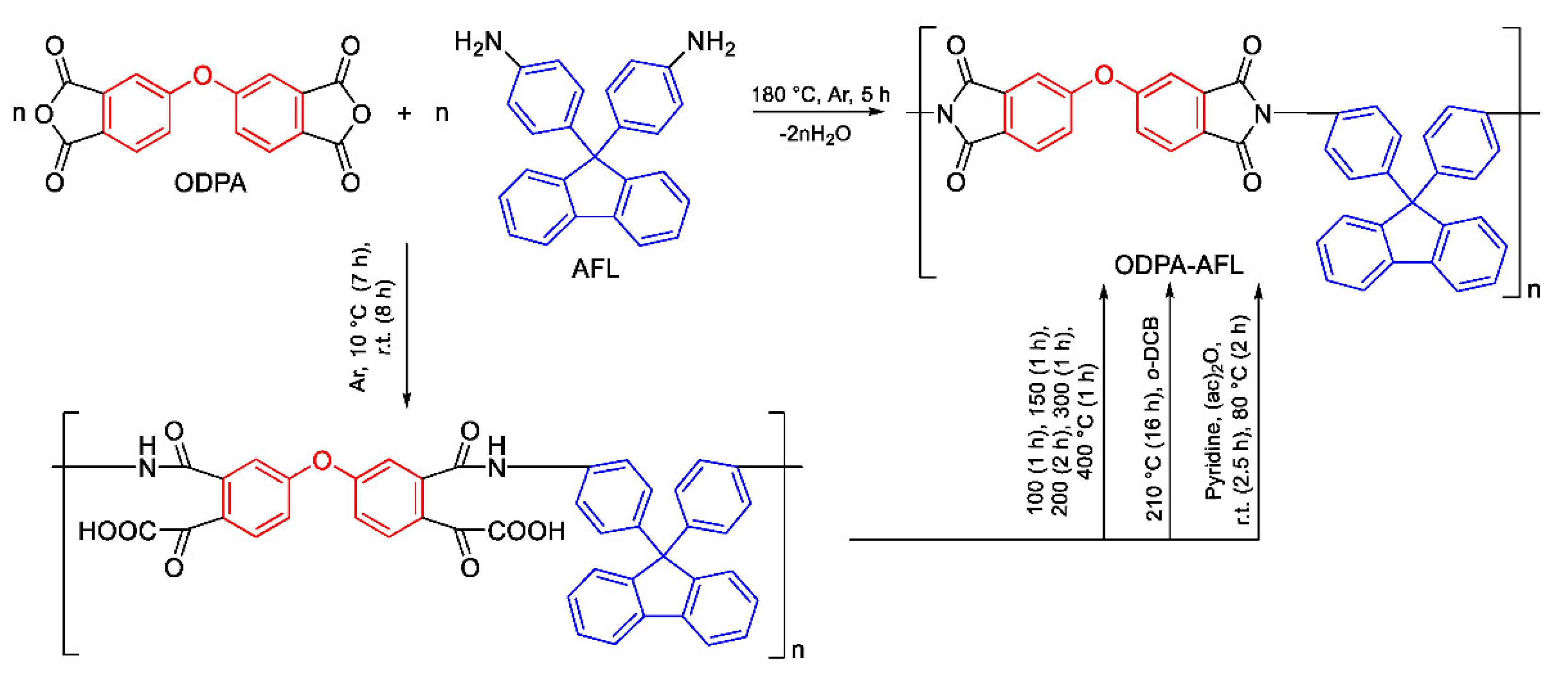

The most common methods of obtaining PIs are two- and, to a much lesser extent, one-step polycondensation of diamines and tetracarboxylic acid dianhydrides. Both of these approaches were compared using the example of a highly soluble cardo PI (ODPA-AFL) formed from 4,4’-oxydiphthalic anhydride (ODPA) and 9,9-bis(4-aminophenyl)fluorene (AFL).

2.1.1. Comparison of Two- and One-Step Methods

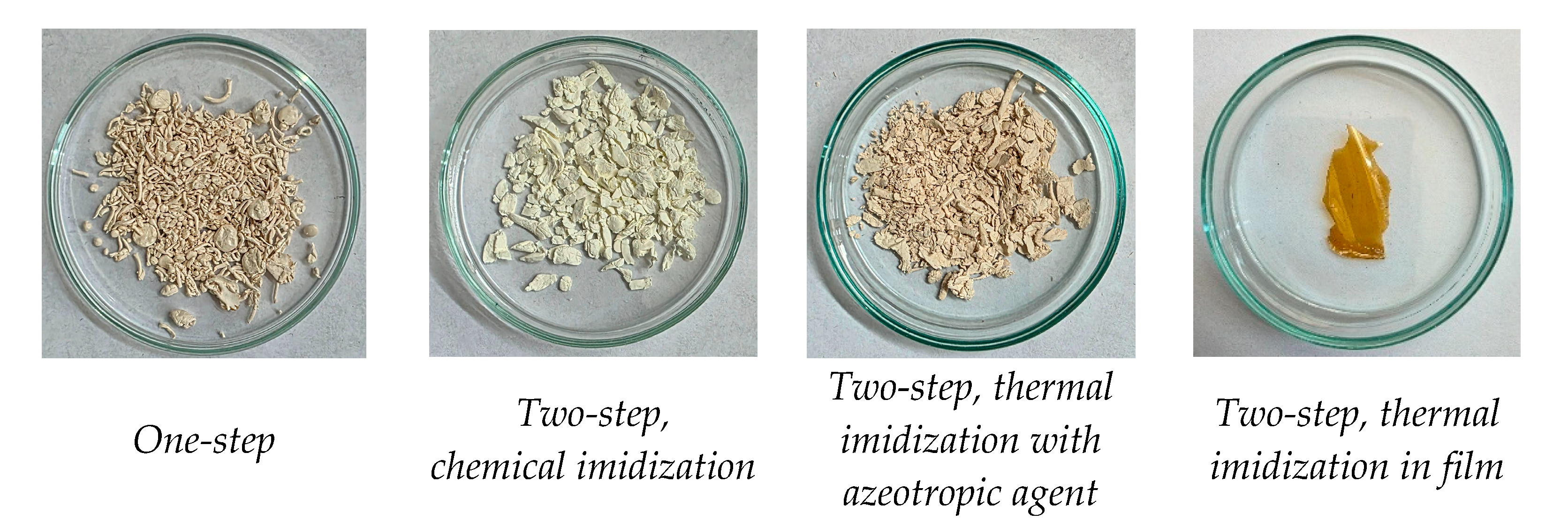

The synthesis of ODPA-AFL was realized out by a one-step method or by a two-step method through the formation of PAA intermediate and its subsequent imidization. The imidization of PAA in the second step was carried out chemically, thermally in a film and thermally in a solution with an azeotropic agent. The reaction routes and conditions, as well as the appearance of ODPA-AFL samples, are shown in

Scheme 1 and

Figure 1.

It is noteworthy that all the applied synthetic approaches for ODPA-AFL yielded a high-molecular-weight product. However, this could not be evaluated for thermally imidized ODPA-AFL film owing to its insolubility in NMP even when heated. The inherent viscosities (ηinh) of the resulting soluble polymers fell within a narrow range of 0.7 to 0.8 dL/g, which is consistent with the ηinh of 0.8 dL/g measured for the PAA intermediate. Notably, the one-step high-temperature method produced high-molecular-weight ODPA-AFL within a shorter time and did not require the traditional acidic or basic catalysts. This method, along with the thermal imidization of PAA in solution using an azeotropic agent, enables the direct manufacture of various PI-based materials from the reaction mixture in a safer solvent environment.

As shown in

Figure 1, the two-step approach employing chemical imidization yielded an almost colorless ODPA-AFL polymer. In contrast, both the one-step synthesis and the two-step method with thermal imidization produced colored samples. These observations are consistent with published data [

18,

60] and are important to consider when fabricating optically transparent films. The variation in color for polyimides of identical structure, formed by different routes, is attributed to side reactions occurring during thermal imidization at elevated temperatures. These reactions can lead to the formation of by-products and chromophoric groups within the polymer backbone, such as via the oxidation of terminal amino groups [

18]. Chemical imidization, proceeding under milder conditions, minimizes such side reactions and thus yields a more colorless product.

We consider the one-step method to be the most economical and reproducible approach, offering precise control over the final polymer’s molecular weight. Consequently, this process was selected for more detailed investigation.

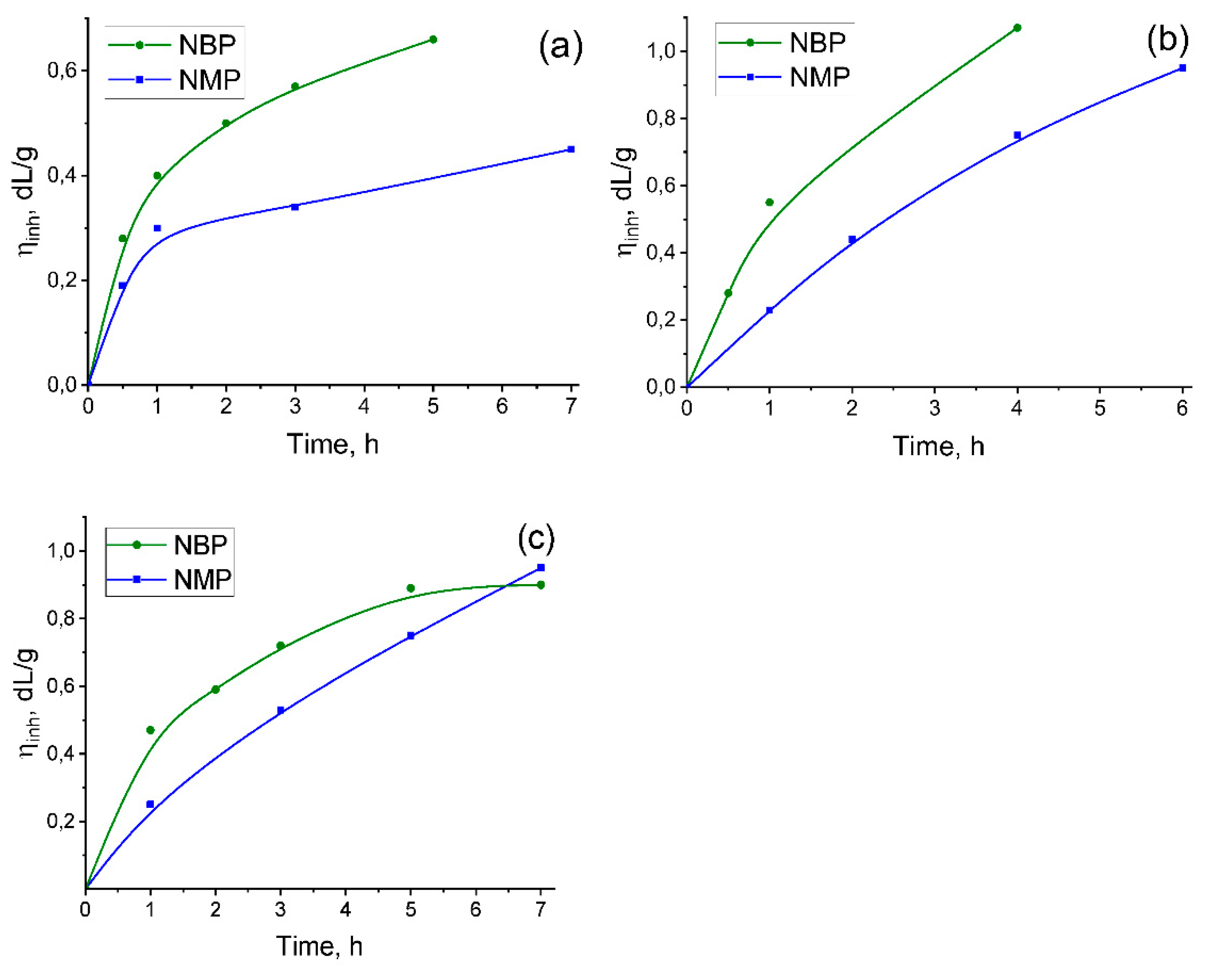

2.1.2. Comparison of Pi Synthesis in Nmp and Nbp

To evaluate the effect of replacing NMP with NBP in a one-step high-temperature polycondensation, the synthesis of three polyimides was studied in both solvents. These polymers were based on ODPA and 3,3’,4,4’-benzophenonetetracarboxylic dianhydride (BTDA) with the diamines AFL and 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (DABA), due to the significant potential of cardo- and carboxylated PIs for manufacturing of a wide variety of functional materials [

2,

4,

10,

12,

61]. Specifically, we compared the kinetics of inherent viscosity (η

inh) increase—as an indicator of molecular weight growth—for ODPA-AFL, ODPA-AFL

0.5:DABA

0.5, and BTDA-AFL

0.5:DABA

0.5 during the reaction (

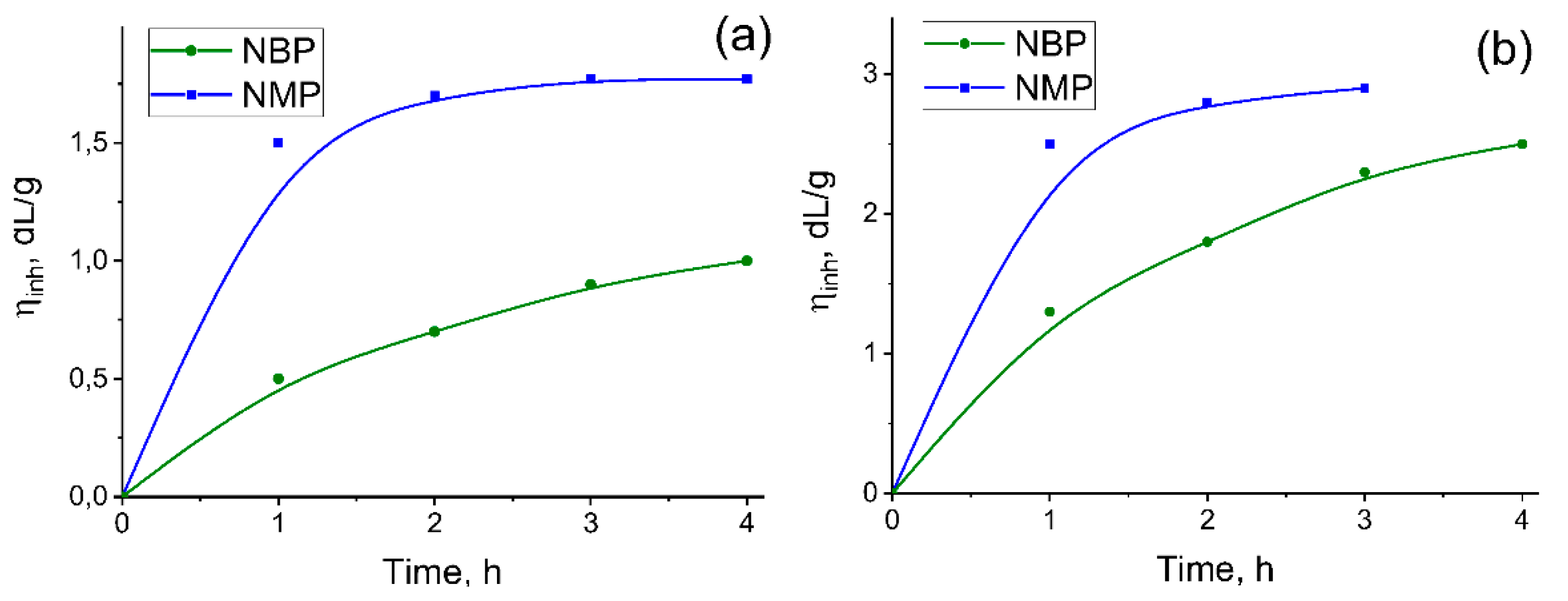

Figure 2). Aliquots were taken from the reaction mixture at specific time intervals, and the η

inh of the isolated polymer was measured to monitor changes in molecular weight.

As evident from the kinetic curves presented in

Figure 2, higher inherent viscosity values were achieved for all PIs during the initial hours of the reaction in NBP compared to the control syntheses conducted in NMP. Specifically, ODPA-AFL, ODPA-AFL

0.5:DABA

0.5, and BTDA-AFL

0.5:DABA

0.5 with high molecular weights (η

inh ≥ 0.4 dL/g) were formed in NBP after just one hour of reaction without any catalyst. In contrast, an equivalent viscosity (η

inh = 0.4 dL/g) for ODPA-AFL obtained in NMP was reached only after 7 hours. These results clearly demonstrate a significant acceleration of the polycondensation process in the NBP medium. The incorporation of side carboxyl groups (as in DABA-containing copolymers) appears to catalyze this process further, which is consistent with published data [

10,

59]. The pronounced acceleration observed in NBP is likely attributable to its greater hydrophobicity compared to NMP. This property may facilitate more effective removal of water from the reaction mixture, thereby shifting the equilibrium towards polyimide formation. Although we have not found any information on this matter, it is possible that an azeotrope mixture of NBP and water may form, similar to the system of N-cyclohexyl-2-pyrrolidone and water [

62]. Both hypotheses warrant further investigation. Nevertheless, the results obtained unequivocally demonstrate the efficacy of NBP as a reaction medium for production high-molecular-weight PIs within a significantly reduced timeframe. This opens promising avenues for optimizing polycondensation process parameters to meet specific application requirements.

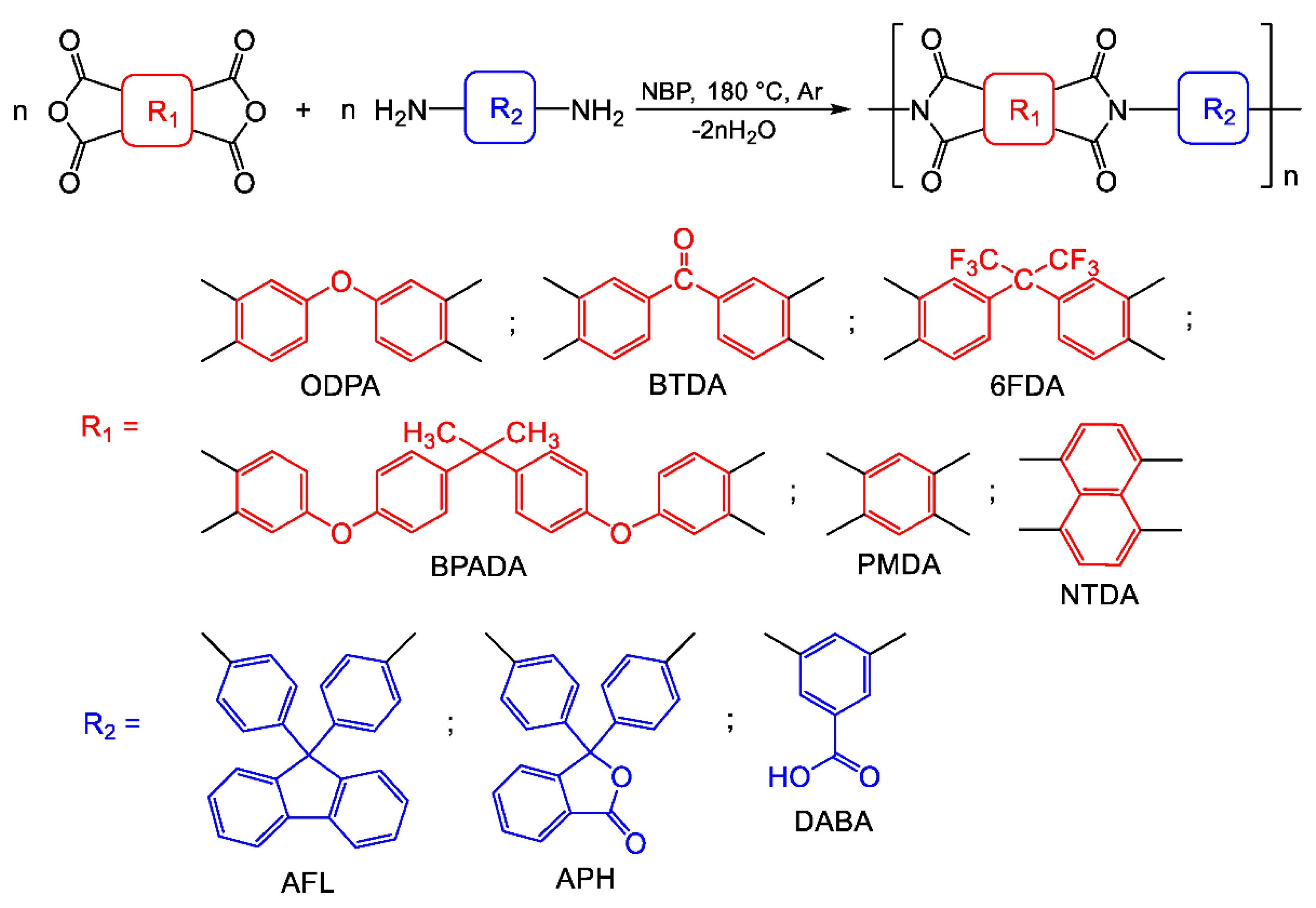

2.1.3. Versatility of Nbp for the Synthesis of Different Pis

To evaluate the versatility of NBP for synthesizing various PIs—including those with flexible or rigid backbones and containing five- or six-membered imide cycles—we employed a series of dianhydrides: ODPA, BTDA, 4,4’-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphthalic anhydride (6FDA), 4,4’-(4,4’-isopropylidene diphenoxy)bis(phthalic anhydride) (BPADA), pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA), and 1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (NTDA) (

Scheme 2). This selection of tetracarboxylic acid dianhydrides was also guided by their significant potential for creating various functional (including electroactive) materials [

10,

18,

21,

25], as well as the need to investigate the synthesis of polymers from monomers with different inherent reactivities. The molecular weight characteristics of the resulting PIs, as determined by viscometry and gel permeation chromatography (GPC), are summarized in

Table 1.

ODPA (E

a=1.30eV), BTDA (E

a=1.55eV), and 6FDA (E

a≈1.4eV) exhibit comparable reactivity [

63]. As noted earlier, ODPA-AFL, ODPA-AFL

0.5:DABA

0.5, and BTDA-AFL

0.5:DABA

0.5 form rapidly and remain soluble throughout the reaction. As expected, 6FDA-DABA—which contains hexafluoroisopropylidene groups in the backbone—is also soluble in NBP and forms high-molecular-weight polymers (M

n = 275-346 kDa, M

w = 430-537 kDa) in both NBP and NMP (

Table 1). BPADA (E

a=1.12eV) [

64] is the least reactive dianhydride in this series. Nevertheless, after 6 hours of reaction in NBP, BPADA-DABA achieved an η

inh = 0.8 dL/g, M

n = 239 kDa, and M

w = 440 kDa. These results demonstrate that high-molecular-weight PIs can be obtained from less reactive monomers in NBP, even without catalytic additives.

Due to the ability of imide cycles to undergo reversible redox reactions and their increased stability, PMDA- and NTDA-based (poly)imides are actively considered for “Post-Lithium Energy Storage Applications” [

25]. These dianhydrides contribute to the formation of polyimides with the most rigid macromolecular backbones. It is well known that the highly reactive PMDA (E

a=1.90eV) [

63] is also prone to side reactions. In our study, a highly viscous PMDA-AFL solution formed in NBP after 4 hours of reaction, yielding the polymer with M

n = 191 kDa, M

w = 320 kDa, and η

inh = 0.9 dL/g. In contrast to PMDA, NTDA exhibits lower reactivity due to the high stability of its six-membered anhydride ring [

65]. Nevertheless, high-molecular-weight PIs based on NTDA can be successfully obtained in NMP [

59]. We observed that both NTDA-APH and NTDA-APH

0.5:DABA

0.5 precipitated during synthesis in NBP, leading to the formation of low-molecular-weight products (η

inh = 0.2–0.3 dL/g, M

n ≈ 12 kDa, M

w = 26–56 kDa) that remained soluble in NMP (

Table 1). The insolubility of oligoimides based on NTDA can also be an additional technological advantage, for example, when there is no need to obtain high-molecular-weight compounds. The product is easily separated from the solvent, eliminating the use of a large amount of precipitant.

It is noteworthy that the inherent viscosity and molecular weight values for all PIs are internally consistent. The obtained PIs are soluble in conventional polar aprotic solvents such as NMP, DMAA, DMF, and DMSO. BPADA-DABA and 6FDA-DABA exhibit solubility in cyclohexanone as well.

The structure of PIs has been confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy (

Supporting Information, Figures S1-S10). All the polymer spectra contain characteristic bands: 1775-1785 cm

−1 (asymmetric) and 1716-1725 cm

−1 (symmetric) - C=O stretching bands in the imide (C=O stretching in acid overlaps with symmetric signals); 1352-1365, 1079-1099, and 719-756 cm

−1 - C–N stretching bands; 2700–3600 cm

−1 - O–H groups of DABA (generally indistinguishable). The signals in the IR spectra of polyimides based on NTDA are shifted to the lower frequency region.

A clear correlation exists between the chemical structure of the polyimides and their thermal properties (

Table 1). Cardo homopolyimides ODPA-AFL exhibit the highest glass transition temperatures (T

g ≥ 350 °C). It was not observed for PMDA-APH until the beginning of decomposition, and its definition made no sense for NTDA-APH and NTDA-APH

0.5:DABA

0.5 due to their low molecular weights. The lower thermo-oxidative stability of PMDA-APH compared to ODPA-AFL is attributed to the degradation of its lactone rings [

66]. As shown in

Table 1, incorporating DABA fragments into the polymer chains slightly reduces the thermal stability of the corresponding PIs: the glass transition temperatures decrease due to meta-substitution in the backbone, and the temperatures of 10% weight loss (Т

10%) are lowered by initial decarboxylation. These trends agree well with previously published data [

10,

59]. As expected, BPADA-DABA has the lowest T

g (260 °C), a result of the increased chain flexibility imparted by its isopropylidene and ether bridging groups.

We have demonstrated that NBP is a suitable solvent for synthesizing a wide range of polyimides with variable chain rigidity, thermal stability, and functionality (side trifluoromethyl, cardo, and carboxyl groups), including those derived from low-reactivity dianhydrides such as BPADA. However, it is not effective for obtaining high-molecular-weight PIs containing six-membered imide rings, such as those derived from NTDA.

2.2. Polyamide Synthesis

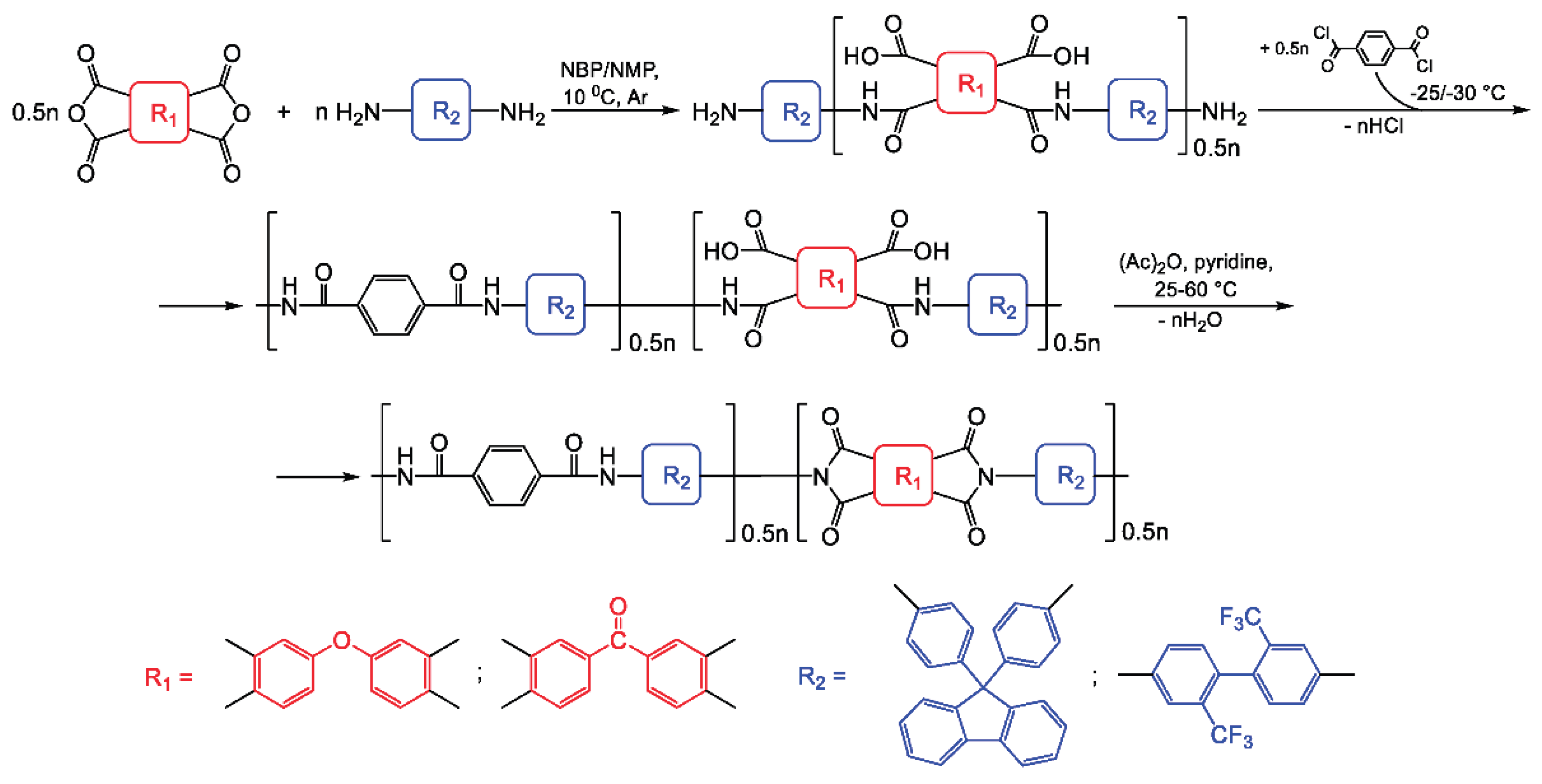

Polyamides (PAs) were synthesized via low-temperature polycondensation of TPC with AFL or TFMB under identical conditions, except for the reaction temperature, which was maintained at -30 °C in NBP and -25 °C in NMP (

Scheme 3). We observed that conducting the synthesis of TPC-AFL in NBP within the temperature range of -25 to -20 °C yielded polymers with lower molecular weights (η

inh ~ 0.4 dL/g) compared to those obtained at the optimal -30 °C (η

inh = 0.9 dL/g). Notably, the reaction mixtures in NBP turned yellow at temperatures of -25 °C or higher. Similar coloration was observed for analogous reactions in NMP, but at higher temperatures. This difference may be attributed to the occurrence of side reactions, as TPC remains soluble in NBP at -25 °C, whereas it is not soluble in NMP at this temperature.

The highly reactive chloroanhydride groups can form adducts with amide-type solvents [

67]. To minimize such side processes, the synthesis should be conducted under heterogeneous conditions.

The polycondensation of aromatic diamines with dichloroanhydrides releases HCl. The free HCl can react with the NH

2-groups, converting them into inactive ammonium salts. This is typically prevented by using organic bases to scavenge HCl. Given that NBP is a structural analog of NMP, it, like NMP, can also form stable salts with HCl, thereby acting as an internal acid acceptor [

5].

The solvent nature significantly influences both the growth kinetics and the limiting η

inh of the resulting PAs. In all cases, the choice of NBP as the reaction medium leads to the formation of high-molecular-weight polymers, albeit over a longer time compared to the reference syntheses in NMP. As shown in

Figure 3, the η

inh of TPC-TFMB and TPC-AFL formed in NMP reaches a plateau after 1.5–2 hours, whereas a monotonic increase in η

inh is observed over 4 hours when the polycondensation is conducted in NBP. The benchmark reaction using NMP yielded PAs with η

inh = 3.0 dL/g (TPC-TFMB) and η

inh = 1.8 dL/g (TPC-AFL) (

Table 2). At the same time, the maximum inherent viscosity of isolated TPC-TFMB and TPC-AFL obtained in NBP were slightly lower – 2.3 and 0.9 dL/g respectively.

A small excess of TPC (3 mol.%) reduces the molecular weight of the resulting polymer, suggesting its potential involvement in side reactions with the solvent. A further increase in TPC loading (7 mol.%) leads to an even more pronounced decrease in the molecular weight of TPC-AFL (

Table 2). This behavior indicates that the chloroanhydride groups likely terminate the growing polymer chains, thereby inhibiting further polymerization. A similar trend of reduced PA molecular weight upon replacing NMP with NBP has been reported previously [

56]. The authors of that study suggested [

56] that this effect could be due to local overheating caused by the exothermic reaction between TPC and the amino groups, which in turn promotes side reactions.

Here, to minimize the risk of local overheating, solid TPC was added gradually. The rate of the main reaction and the molecular weight of the resulting polymer, obtained via low-temperature polycondensation of diamines with dicarboxylic acid dichlorides, are likely influenced by the specific properties of the solvent used, such as its polarity, hydrogen-bonding capacity, and basicity [

68]. Kinetic studies using the Menschutkin reaction as a model have demonstrated that reaction rates in dipolar aprotic solvents correlate strongly with the Kamlet–Taft solvatochromic parameter π* values correspond to faster reaction rates [

69]. The π* value of NBP (0.77) is lower than that of NMP (0.92) [

69], which aligns with the experimentally observed lower reaction rate in NBP in our study. Similar conclusions were drawn in [

58], where it was shown that high-molecular-weight poly(amic acids) form more readily in solvents with higher polarity. Conversely, the achievable molecular weight may also be related to the solvent’s dielectric constant (ε) [

68]. For instance, during the low-temperature reaction of bis-(4-oxy-3-chlorophenyl-2,2-propane) with TPC, a tendency toward lower molecular weight of the resulting polyester was observed when using a solvent with a higher dielectric constant [

68]. This trend is consistent with our findings for PA synthesis: the dielectric constants for NBP and NMP are 40 [

70] and 32.2 [

69], respectively, with the higher ε of NBP potentially contributing to the observed lower molecular weights compared to NMP.

The polymers obtained in NBP were isolated as white fibers (TPC-AFL) or hard yellowish pellets (TPC-TFMB). In contrast, both PAs synthesized in NMP were obtained as white fibers. The solubility of the PAs was tested in NMP, NBP, DMAc, DMF, and DMSO at ambient temperature and at 60 °C (

Table 2). TPC-AFL samples, whether derived from NBP or NMP, exhibited good solubility in the listed amide solvents but were insoluble in DMSO. DMSO also proved unsuitable for dissolving the fluorinated TPC-TFMB polymers. Furthermore, the TPC-TFMB pellets isolated from NBP were difficult to dissolve in all tested amide solvents, even upon heating. In contrast, the reference TPC-TFMB fibers synthesized in NMP dissolved readily in these solvents at room temperature.

The GPC results are consistent with the η

inh data, as summarized in

Table 2. PAs obtained in NBP exhibit slightly lower molecular weights than the benchmark polymers, with M

w ranging from 137 to 164 kDa and M

n from 46 to 51 kDa. It is noteworthy that the molecular weights of TPC-TFMB, determined in both solvents, were lower than those of the cardo-based polyamide (TPC-AFL), despite its higher η

inh values. This apparent discrepancy may be attributed to the formation of strong hydrogen bonds in TPC-TFMB, which can lead to an overestimation of its molecular weight by viscometry.

The structure of PAs was confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy and was found to be identical to that of the reference samples obtained in NMP (

Supporting Information, Figures S11, S12). All IR spectra exhibit characteristic absorption bands: the Amide I band (C=O stretch) at ~1660 cm⁻¹, the Amide II band (N–H bend coupled with C–N stretch) at ~1515 cm⁻¹, and a broad N–H stretching band in the 3300–3500 cm⁻¹ region. It should be noted that for TPC-AFL, the Amide II signal is overlapped by a strong single band at 1508 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to the

v(C=C) vibration of the cardo moiety.

The thermal properties of PAs were evaluated by TMA and TGA as well (

Table 2). The T

g values were 380 °C for TPC-AFL and 260 °C for TPC-TFMB. The thermo-oxidative stability of the polymers was found to be independent of the nature of the diamine and the solvent used for synthesis. T

10% for cardo-based and fluorinated PAs range from 470 (480) to 500 °C.

2.3. Poly(amide-Imide) Synthesis

PAIs bearing cardo or trifluoromethyl groups were synthesized via low-temperature polycondensation of AFL or TFMB with aromatic tetracarboxylic dianhydrides and TPC, proceeding through poly(amide-amic acid) (PAAA) intermediates. The established synthetic protocol—including the sequence of reagent addition, their concentration, temperature, and duration —was based on a previously reported procedure using conventional NMP as the solvent [

5]. The reaction route is presented in

Scheme 4.

In the first stage, an amic acid intermediate was synthesized by adding the solid dianhydride to a cooled (10 °C) diamine solution. Subsequently, TPC was introduced portionwise, and the inherent viscosity of the resulting poly(amide-amic acid) (PAAA) was monitored. Cyclization of the PAAA was then carried out using a mixture of acetic anhydride and pyridine. Previous studies have shown that the temperature of the reaction between the intermediate amic acid and TPC significantly influences the molecular weight of both the PAAA and the final PAI [

5]. Specifically, higher-molecular-weight PAIs form in NMP at -25 °C [

5]. In the present study, using the synthesis of ODPA:TPC-AFL as a model, we investigated the effect of this reaction temperature on the viscosity of the final PAI. The reaction was performed in anhydrous NBP at temperatures of -20, -25, and -30 °C. As anticipated, the polymer with the highest molecular weight (η

inh = 0.6 dL/g) formed at -30 °C. Synthesis at -25 °C and -20 °C yielded PAIs with η

inh values two or more times lower—0.4 and 0.2 dL/g, respectively. Similar to the PA synthesis described earlier, the reaction mixture acquired a yellowish coloration at the higher temperatures.

As shown in

Figure 4, substituting NBP for NMP results in a significant decrease in the η

inh of PAAAs. Unlike the synthesis of PAs in NBP, the η

inh values for PAAAs show little dependence on the duration of the second reaction stage. In all cases, irrespective of the solvent used, the maximum molecular weight—as inferred from η

inh —was attained after 1.5–2 hours of reaction.

Consequently, the inherent viscosities of PAAAs synthesized in NBP were 0.4–0.7 dL/g (for cardo-based polymers) and 1.4–1.6 dL/g (for fluorinated polymers). In contrast, the benchmark PAAAs obtained in NMP exhibited η

inh values of 0.7–1.2 dL/g and 2.0–2.6 dL/g, respectively (

Table 3). As summarized in

Table 3, the inherent viscosities of the final PAIs were either comparable to or lower than those of the corresponding PAAA intermediates.

It was found that exceeding the equimolar concentration of TPC by 3, 7, and 10 mol.% increases the molecular weight of both the PAAA intermediates and the resulting PAIs during synthesis in NBP (

Table 4). However, a 3 mol.% excess of TPC has only a minor effect on the molecular weight of the final PAIs.

The optimal results were achieved with a 7 mol.% excess of TPC. Under these conditions, the inherent viscosities of the isolated ODPA:TPC-AFL and BTDA:TPC-AFL polymers were 0.9 dL/g and 0.7 dL/g, respectively—significantly higher than the values of 0.6 dL/g and 0.3 dL/g obtained at equimolar loading (

Table 4). A further increase in TPC content to 10 mol.% did not lead to additional gains in molecular weight. It is noteworthy that, in contrast, varying the TPC concentration in the comparative syntheses carried out in NMP had no significant effect on the inherent viscosity of the final PAIs.

High-molecular-weight polymers are essential for achieving superior performance in derived products such as films, coatings, and membranes. Therefore, the cardo-based PAIs formed in NBP with a 7 mol.% excess of TPC, which exhibited optimal molecular weights, were selected for further investigation. In contrast, fluorinated PAIs obtained under equimolar monomer loading already possess inherently high viscosities, which could limit their solubility in common solvents. Consequently, targeting even higher molecular weights for this class of polymers is not practical.

Most of the synthesized PAIs (from both solvents) were isolated as white or pale yellow fibers with good solubility in common dipolar aprotic solvents, including NMP, NBP, DMAc, DMF, and DMSO, at ambient temperature or upon heating (

Table 5). However, when NBP was used for the synthesis of BTDA:TPC-TFMB, it yielded hard yellowish pellets that were soluble only in hot organic solvents. This contrasts with the readily soluble white fibers of the same polymer obtained from NMP.

The molecular weights of PAIs estimated from GPC data are in good agreement with their η

inh values (

Table 5).

Overall, the polymers synthesized in NBP exhibit comparable or slightly lower molecular weights than their counterparts isolated from NMP. A notable exception is BTDA:TPC-AFL, which displayed an η

inh = 0.7 dL/g—exceeding that of the reference PAI from NMP (η

inh = 0.6 dL/g, even with a 7 mol.% excess of TPC; see

Table 4). These results demonstrate that NBP is a suitable medium for synthesizing PAIs with high molecular weight characteristics, yielding polymers with Mn = 46–202 kDa, Mw = 195–384 kDa, and a polydispersity ranging from 1.9 to 4.2.

The structure of PAIs was confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy (

Supporting Information, Figures S13–S16). All PAIs exhibited characteristic absorption bands corresponding to their functional groups: asymmetric and symmetric imide C=O stretching at ~1780 and ~1723 cm⁻¹, respectively; the Amide I band at ~1669 cm⁻¹; the Amide II band at ~1523 cm⁻¹; imide C–N–C stretching at ~1370 cm⁻¹; and C–F stretching (from CF₃ groups) in the 1248–1054 cm⁻¹ region, with distinct bands at ~1248 and ~1173 cm⁻¹. The absence of a broad absorption band in the 2600–3600 cm⁻¹ region, which would correspond to O–H stretching vibrations of carboxylic acid groups, confirms the formation of a fully imidized structure [

71].

As with the other polymer classes studied, the choice of reaction medium (NBP vs. NMP) does not significantly affect the T

g of the resulting PAIs. For cardo-based PAIs, T

g values were in the range of 370–380 °C, whereas the fluorinated PAIs exhibited lower T

g values of approximately 260–285 °C. The observed T

g values and their dependence on the PAI structure are consistent with previously published data [

5,

72].

The temperatures of 10% weight loss were determined from the original TGA thermograms and are summarized in

Table 5. All PAIs exhibit high thermo-oxidative stability, which is independent of the reaction medium used for their synthesis. The T

10% values for these polymers range from 490 to 525 °C.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Monomers and other chemicals were purchased from TCI or Acros Organics. 2,2’-Bis(trifluoromethyl)benzidine (> 98%, Mp = 188 °C), 9,9-bis(4’-aminophenyl)fluorene (> 98%, Mp = 236–237 °C), 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (98%, Mp = 236 – 237 °С), 3,3’,4,4’-diphenyl ether tetracarboxylic acid dianhydride (> 98%, Mp = 226 °C), 3,3’,4,4’-benzophenonetetracarboxylic dianhydride (> 96%, Mp = 222 °C ), 4,4’-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphthalic anhydride (98%, Mp = 244 – 245 °С), 1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (97%), pyromellitic dianhydride (98%, Mp = 285 – 287 °С) were purified by vacuum sublimation (20 Pa) at the temperatures close to their melting points. 4,4′-(4,4′-Isopropylidenediphenoxy)bisphthalic dianhydride (97%, Mp = 184,5 – 186 °С) was dried at 140 °С in vacuum for 8 hours. Terephthaloyl chloride (> 98%, Mp = 83 °C) was purified by vacuum distillation before use. 3,3-Bis(4-aminophenyl)phthalide (Mp = 204 °С) was recrystallized from ethanol. Pyridine (99%) and acetic anhydride (98%) were used as received without further purification. NBP (99%) and NMP (99%) were kept for two days over CaH2 and then distilled under reduced pressure before use. All other commercially available reagent-grade chemicals were used without additional purification.

3.2. Polyimide Synthesis

PIs were synthesized by one-step or two-step methods. Synthesis of ODPA-AFL is given below as an example. The structures of the synthesized PIs have been confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy (

Supporting Information, Figures S1–S10).

3.2.1. One-Step Method

ODPA (1.5511 g, 5 mmol), AFL (1.7423 g, 5 mmol) and 12.5 mL NBP were charged into a 100-mL, a tree-necked round-bottomed flask. The mixture was heated to 180 °C in an inert atmosphere with stirring. The reaction was continued for 5 h at this temperature. Aliquots were taken from the reaction mixture at specific time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 3 and 5 h) and a part of the polymer was precipitated into an excess of methanol to estimate the change in the molecular weight. The samples were washed in the Soxhlet extractor with methanol for 2 days and then dried under normal conditions for 24 hours, in a vacuum at 70 °C for two days, and finally at 220 °C during 1h.

3.2.2. Two-Step Methods

ODPA-AFL polyimide was synthesized via the two-step methods through a PAA intermediate.

Synthesis of PAA

AFL (3.4845 g, 10.0 mmol) was dissolved in 27.5 mL of NBP at room temperature. The solution was then cooled to 10 °C in an ice bath. Under an inert argon atmosphere, a stoichiometric amount of ODPA (3.1022 g, 10.0 mmol) was added slowly to the cooled diamine solution. The reaction mixture was stirred at 10 °C for 7 hours, followed by 8 hours at ambient temperature (25 °C), yielding a 20 wt% PAA solution in NBP. This PAA precursor was divided into three equal parts for subsequent imidization via different methods.

Chemical imidization

A portion of the PAA solution was chemically imidized by adding pyridine (catalyst, 1.75 molar excess) and acetic anhydride (dehydrating agent, twofold molar excess). The mixture was stirred under an inert atmosphere at 25 °C for 2.5 hours and then at 80 °C for 2 hours. The resulting viscous polyimide solution was diluted with NMP to approximately 5 wt% and precipitated into a fivefold excess of vigorously stirred deionized water. The fibrous precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with deionized water several times, and then in a Soxhlet extractor with methanol for 48 hours. Polyimide was dried under normal conditions for 24 hours, in a vacuum at 70 °C for two days, and finally at 220 °C during 1h.

Thermal imidization

A portion of the 20 wt% PAA solution was cast onto a clean glass plate. PAA was then thermally treated at 100 °C, 150 °C, and 200 °C for 1 hour at each temperature. Subsequently, the film was detached from the substrate and annealed in a furnace at 200 °C, 300 °C, and 400 °C (1 hour each) to complete the imidization cyclization and remove any residual solvent.

Thermal imidization with an azeotropic mixture

A portion of the PAA solution was thermally imidized in solution using o-dichlorobenzene as a co-solvent to form an azeotrope with the water released during imidization. o-Dichlorobenzene (30 vol% relative to NBP) was added to the PAA solution. The mixture was heated at 210 °C under argon with vigorous stirring for 16 hours. The resulting polyimide solution was diluted with NMP to about 5 wt% and precipitated into a fivefold excess of methanol. The polymer was collected by filtration, washed in a Soxhlet extractor with methanol for 48 hours, and dried under normal conditions for 24 hours, in a vacuum at 70 °C for two days, followed by 220 °C for 1 hour.

3.3. Polyamide Synthesis

PAs were obtained by low-temperature polycondensation of the diamine with terephthaloyl chloride. Synthesis of FDA:TPC is given below as an example. In a 250 mL three-neck flask, equipped with a mechanical stirrer and argon in-let, 3.10 g (10 mmol) of FDA was dissolved in 20 mL of NBP at room temperature. The flask was cooled to -30 °C using a liquid nitrogen / acetone bath, and then solid terephthaloyl chloride (2.03 g, 10 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture in portions. The reaction was conducted at -30 °C for 3 h and then stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The resulting highly viscous PA solution was diluted with NMP up to 5 wt%. Polymer was precipitated into water. Fiber-like precipitate was collected by filtration, washed in the Soxhlet extractor with acetone for 2 days and then dried in a vacuum at 70 °C (6 h), 150 °C (6 h) and finally at 250 °C (1 h). Yield: 97%, 4.25 g. The structures of the synthesized PAs have been confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy (

Supporting Information, Figures S11 and S12)

3.4. Poly(amide-Imide) Synthesis

PAIs were synthesized in the same manner, according to the method described in detail earlier [

5,

71]. The synthesis of ODPA:FDA:TPC illustrates the general synthetic route. In a 250 mL three-neck flask, equipped with a mechanical stirrer and argon in-let, 3.10 g (10 mmol) of FDA was dissolved in 20 mL of NBP at room temperature. ODPA (1.55 g, 5.0 mmol) was added to the solution cooled up to 10 °C and the reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature until the formation of a homogeneous solution and for further 1–5 h. Then the reaction mixture was cooled to -30 °C using a liquid nitrogen /acetone bath, and 1.02 g (5.0 mol) of solid TPC was added portionwise. The reaction was carried out for another 2 h. The chemical imidization of polyamide-amiс acid was performed using a mixture of acetic anhydride (3.7 mL, 40 mmol) and pyridine (2.8 mL, 35 mmol) at room temperature during 12 h and finally at 60 °C for 4 h. The resulting highly viscous PAI solution was diluted with NMP up to 5 wt%. Polymer was precipitated into 1.5 L of water under continuous stirring. Fiber-like precipitate was collected by filtration, washed thoroughly several times with water and methanol, then dried in vacuum oven at 70 °C (6 h), 150 °C (6 h) and finally at 250 °C (1 h). Yield: 96%, 4.92 g. The structures of PAIs have been confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy (

Supporting Information, Figures S13–S16).

3.5. Methods

FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer spectrometer (USA) using a UATR accessory Perkin Elmer (USA) with a Di/ZnSe crystal.

The inherent viscosity (ηinh) was measured for the solution of 0.05 g of polymer in NMP (10.0 mL) at 25.0 °C using an Ostwald viscometer. For some PAAAs, the inherent viscosities were estimated as a function of the reaction time. For this purpose, the samples taken at certain time intervals during the synthesis were diluted with dry solvent to C = 0.5 g/dL, and then the solution flow time was determined. High temperature gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analyses of polymers were performed with a Waters Alliance GPCV 2000 GPC instrument equipped with a Waters DRI detector. The column set (Styragel HT6E) was eluted with NMP polymer solutions (C = 1.0 mg/mL) at 1.0 mL/min at 80 °C. Data were calibrated using monomodal polystyrene standards (from Polymer Standards Service).

Thermomechanical analysis (TMA) was performed with a thermomechanical analyzer TMA/SDTA 2+ LN/600 (Mettler-Toledo, Switzerland) at a heating rate of 5 °C/min with constant load 1 N using a quartz stem with a ball point tip (diameter 3 mm). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed by Thermoanalyzer Shimadzu DTG-60H (Japan) on samples with weight of about 5 mg at a heating rate of 10 oC/min in air. The temperature at which a weight loss of 10% was detected was considered to be the decomposition onset temperature.

4. Conclusions

The synthesis of PIs, PAs, and PAIs bearing side cardo, trifluoromethyl, and carboxyl groups in NBP has been thoroughly investigated. It has been demonstrated that NMP can be successfully replaced by NBP in both one- and two-step syntheses of PIs. Notably, the one-step process in NBP leads to a significant acceleration in the formation of high-molecular-weight products, achieving target molecular weights within 1–2 hours. This effect is presumably due to the greater hydrophobicity of NBP, which facilitates more efficient removal of water (the condensation by-product) from the reaction mixture, thereby shifting the equilibrium toward product formation.

While NBP proved to be highly effective for synthesizing various PIs with five-membered imide cycles, its application for polymers with six-membered cycles based on 1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (NTDA) was limited. In the latter case, precipitation occurred during the reaction, resulting in low-molecular-weight products.

For PAs and PAIs, the choice of NBP generally yielded polymers with slightly lower molecular weights and required longer reaction times compared to the reference polymers produced in NMP. This difference in kinetics and achievable molecular weight is influenced by the solvent’s physicochemical properties, such as its Kamlet–Taft parameters and dielectric constant, which affect both the main reaction rate and the likelihood of side reactions. Optimization revealed that a 7 mol.% excess of terephthaloyl chloride (TPC) significantly increases the molecular weights of PAIs obtained in NBP.

Furthermore, the choice of solvent impacts the physical form and solubility of the products. Using NBP for the synthesis of fluorinated PAs or PAIs resulted in the formation of hard yellowish pellets soluble only in hot organic solvents. In contrast, the same polymers isolated from NMP were obtained as white fibers with high solubility at room temperature. The glass transition temperatures and thermo-oxidative stability of all polymers were found to be independent of the solvent applied.

In summary, NBP - a less toxic and more environmentally benign alternative to traditional solvents such as NMP, DMAA, DMF, and m-cresol - has been established as a promising reaction medium for obtaining high-molecular-weight PIs, PAs, and PAIs. We propose that NBP is suitable not only for the classes of polymers studied here but also holds potential for the production of other high-performance polymers, including polysulfones, polyetherketones, polybenzimidazoles, and polyarylates.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.N.Z. and D.A.S.; methodology, O.N.Z., A.V.C., D.A.K. and D.O.P.; software, A.V.C., D.A.K. and D.O.P.; validation, O.N.Z., A.V.C., D.A.K., D.O.P. and D.A.S.; formal analysis, O.N.Z., A.V.C., D.A.K. and D.O.P.; investigation, O.N.Z., A.V.C., D.A.K. and D.O.P.; resources, O.N.Z., A.V.C., D.A.K., D.O.P. and D.A.S.; data curation, O.N.Z., A.V.C. and D.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.N.Z., A.V.C. and D.A.S.; writing—review and editing, O.N.Z., A.V.C. and D.A.S.; visualization, O.N.Z., A.V.C. and D.A.S.; supervision, D.A.S..; project administration, D.A.S.; funding acquisition, O.N.Z., A.V.C., D.A.K., D.O.P. and D.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Contract No. 075-00276-25-00).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor, Doctor of Sciences Yakov S. Vygodskii for his supervision at the initial stage of the study, PhD Bato A. Bayminov for the idea of using NBP in the synthesis of PIs and some initial experiments, Engineer Nadezhda A. Popova for the synthesis of some PIs, and Engineer Valentina Chumakova for studying polymers using IR spectroscopy. The contribution of Center for molecule composition studies of INEOS RAS is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gouzman, I.; Grossman, E.; Verker, R.; Atar, N.; Bolker, A.; Eliaz, N. Advances in Polyimide-Based Materials for Space Applications. Adv Mater 2019, 31, e1807738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, D.-J.; Wang, K.-L.; Huang, Y.-C.; Lee, K.-R.; Lai, J.-Y.; Ha, C.-S. Advanced polyimide materials: Syntheses, physical properties and applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2012, 37, 907–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikov, D.A.; Baiminov, B.A.; Vygodskii, Y.S. Highly Heat-Resistant Polymeric Coatings of Optical Fibers. Polymer Science, Series C 2020, 62, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; He, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, S. Progress in Aromatic Polyimide Films for Electronic Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabegaeva, O.N.; Kosolapov, A.F.; Semjonov, S.L.; Ezernitskaya, M.G.; Afanasyev, E.S.; Godovikov, I.A.; Chuchalov, A.V.; Sapozhnikov, D.A. Polyamide-imides as novel high performance primary protective coatings of silica optical fibers: Influence of the structure and molecular weight. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2024, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chai, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, W.; Fang, Z.; Li, B. Recent Study Advances in Flexible Sensors Based on Polyimides. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, D.; Chatterjee, R.; Banerjee, S. Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application. e-Polymers 2021, 21, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononova, S.V.; Gubanova, G.N.; Lebedeva, G.K.; Kruchinina, E.V.; Vlasova, E.N.; Popova, E.N.; Zakharova, N.V.; Vylegzhanina, M.E.; Novozhilova, E.A.; Danilova, K.V. Realization of Intermolecular Interactions as a Basis for Controlling Pervaporation Properties of Membranes Made of Aromatic Polyamide-Imides. Membranes (Basel) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulyalina, A.; Rostovtseva, V.; Faykov, I.; Tataurov, M.; Dubovenko, R.; Shugurov, S. Development of Novel Polyamide-Imide/DES Composites and Their Application for Pervaporation and Gas Separation. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapozhnikov, D.A.; Chuchalov, A.V.; Vygodskii, Y.S. Carboxylated polyimides for advanced functional materials: synthesis, modification, and various applications. European Polymer Journal 2025, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Ling, Q.; Sang, L. Advances in pervaporation desalination based on polymer membranes. RSC Adv 2025, 15, 20985–21005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Croft, Z.L.; Guo, D.; Cao, K.; Liu, G. Recent development of polyimides: Synthesis, processing, and application in gas separation. Journal of Polymer Science 2021, 59, 943–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikov, D.A.; Vygodskii, Y.S. Achievements in polycondensation and condensation polymers. Polymer Science Series B 2015, 57, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Polyamide-imides Containing Thioether Linkages, Thiazole, and Nitrophenyl Units with High Solubility and Processability for Optical Film Applications. Journal of Applied Material Science 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Li, W.; Shi, S.; He, K.; Ma, P.; Chen, M.; Yang, C. High-temperature-resistant and colorless polyimide: Preparations, properties, and applications. Solar Energy 2020, 195, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.-S.; Wong, H.Q.; Yen, H.-J.; Kung, Y.-R. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Ion-Selective Polyamides Bearing a Phenanthrene Chromophore. ACS Applied Optical Materials 2025, 3, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Cao, J.-H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, S.-G.; Liang, W.-H.; Wu, D.-Y. Colorless Polyamide–Imide Films with Enhanced Thermal and Dimensional Stability and Their Application in Flexible OLED Devices. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2022, 4, 7664–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapaswi, P.K.; Ha, C.S. Recent Trends on Transparent Colorless Polyimides with Balanced Thermal and Optical Properties: Design and Synthesis. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 2019, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; He, X.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, F.; Lu, Q. Short-side-chain regulation of colorless and transparent polyamide-imides for flexible transparent displays. European Polymer Journal 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Seong, J.G.; Lee, Y.M. Polyimides containing aliphatic/alicyclic segments in the main chains. Progress in Polymer Science 2019, 92, 35–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothavade, P.; Kafi, A.; Shanmuganathan, K.; Bateman, S. High performance polyimides for additive manufacturing: A critical review. Progress in Polymer Science 2026, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrinalini, M.; Prasanthkumar, S. Recent Advances on Stimuli-Responsive Smart Materials and their Applications. Chempluschem 2019, 84, 1103–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Lv, X.; Zhang, C.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, R.; Cai, W.; Niu, H.; Wang, W. Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Polyamides Containing Benzophenothiazine Being Sensitive to TNP, Acid, Voltage, and Light. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2023, 5, 9466–9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A.-E.; Constantin, C.-P.; Damaceanu, M.-D. ProDOT-containing polyamides: On the road from energy storage materials to perspective electrochromic capacitive windows. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimkar, A.; Bergman, G.; Ballas, E.; Tubul, N.; Levi, N.; Malchik, F.; Kukurayeve, I.; Chae, M.S.; Sharon, D.; Levi, M.; et al. Polyimide Compounds For Post-Lithium Energy Storage Applications. Angewandte Chemie 2023, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Xia, L.; Liu, J.; Yao, L.; Xie, H.; Luo, J.; Pan, Z. Molecular engineering of polyamide-imide copolymers for high-temperature energy storage. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CandidateList of Substances of Very High Concern for Authorisation. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/candidate-list-table (accessed on.

- San José, E.; de la Viuda, M.R.; Carmona, F.J.; Soto, C.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A.; Tena, A. Green dipolar aprotic solvents for the dynamic polycondensation of high-performance polyimide membranes. Green Chemistry 2024, 26, 11984–12007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A. The greening of solvents: Towards sustainable organic synthesis. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2019, 18, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisz, E.; Koston, M.; Szostak, M. N-Butylpyrrolidone (NBP) as a non-toxic substitute for NMP in iron-catalyzed C(sp2)–C(sp3) cross-coupling of aryl chlorides. Green Chemistry 2021, 23, 7515–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yong, W.F.; Gao, J.; Shao, D.-D.; Sun, S.-P. Understanding the role of substrates on thin film composite membranes: A green solvent approach with TamiSolve® NxG. Journal of Membrane Science 2021, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J.; Parker, H.L.; Moonen, K.; Farmer, T.J.; Hunt, A.J. N-Butylpyrrolidinone as a dipolar aprotic solvent for organic synthesis. Green Chemistry 2016, 18, 3990–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, B.K.; Yap, Y.J.; Yong, W.F. Green solvents in membrane separation: progress, challenges, and future perspectives for sustainable industrial applications. Green Chemistry 2025, 27, 11705–11738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanković, A. Review of 12 Principles of Green Chemistry in Practice. International Journal of Sustainable and Green Energy 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, T.; Russo, F.; Criscuoli, A.; Figoli, A. TamiSolve® NxG as novel solvent for polymeric membrane preparation. Journal of Membrane Science 2017, 542, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Li, T.; Tiraferri, A.; Drioli, E.; Figoli, A.; Crittenden, J.C.; Liu, B. Toward the Next Generation of Sustainable Membranes from Green Chemistry Principles. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 9, 50–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schouwer, F.; Adriaansen, S.; Claes, L.; De Vos, D.E. Bio-based N-alkyl-2-pyrrolidones by Pd-catalyzed reductive N-alkylation and decarboxylation of glutamic acid. Green Chemistry 2017, 19, 4919–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diorazio, L.J.; Hose, D.R.J.; Adlington, N.K. Toward a More Holistic Framework for Solvent Selection. Organic Process Research & Development 2016, 20, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Bai, R.; Ferlin, F.; Vaccaro, L.; Li, M.; Gu, Y. Replacement strategies for non-green dipolar aprotic solvents. Green Chemistry 2020, 22, 6240–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.; Pletscher, S.; Aemissegger, A.; Bucher, C.; Gallou, F. N-Butylpyrrolidinone as Alternative Solvent for Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis. Organic Process Research & Development 2018, 22, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlander, A.; Ludtke, C.; Sahakjan, A.; Johnsson, R.E. N-Butylpyrrolidinone is an equally good solvent as N,N-dimethylformamide for microwave assisted solid phase peptide synthesis. J Pept Sci 2024, 30, e3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, F.; Marino, T.; Galiano, F.; Gzara, L.; Gordano, A.; Organji, H.; Figoli, A. Tamisolve((R)) NxG as an Alternative Non-Toxic Solvent for the Preparation of Porous Poly (Vinylidene Fluoride) Membranes. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Ursino, C.; Sayinli, B.; Koyuncu, I.; Galiano, F.; Figoli, A. Advancements in Sustainable PVDF Copolymer Membrane Preparation Using Rhodiasolv® PolarClean As an Alternative Eco-Friendly Solvent. Clean Technologies 2021, 3, 761–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, S.; Van der Bruggen, B. Green Synthesis of Cation Exchange Membranes: A Review. Membranes (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, W.H.D.; Lau, H.S.; Yong, W.F. An integrated life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis: Evaluation on the production of polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1) and UiO-66-NH(2) as membrane materials. Sci Total Environ 2023, 892, 164582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, A.M.; Thür, R.; van Duffel, B.; Vankelecom, I.F.J. Use of green polar aprotic solvents TamiSolve® NxG, DMSO and methyl-THF for the synthesis of asymmetric polyimide-based biogas purification membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2025, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïdi, S.; Macedonio, F.; Russo, F.; Hannachi, C.; Hamrouni, B.; Drioli, E.; Figoli, A. Preparation and characterization of hydrophobic P(VDF-HFP) flat sheet membranes using Tamisolve® NxG solvent for the treatment of saline water by direct contact membrane distillation and membrane crystallization. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinabadi, S.R.; Caspers, S.; Shenoy, A.M.; Nevel, A.-S.V.; Rutgeerts, L.A.J.; Vankelecom, I.F.J. Solution casting temperature changing for crosslinked polyvinylidene difluoride solvent resistant nanofiltration membranes: understanding the phase inversion process and performance impact. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, S.; Bosko, M.L.; Eerdekens, T.; Van Leuven, W.; Brozzi, E.; Ruya, P.M.; Van der Bruggen, B. Utilizing green solvents to synthesize high performance crosslinked sulfonated PEEK cation exchange membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2025, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, Z.; Rutgeerts, L.A.J.; Van den Mooter, P.-R.; Vankelecom, I.F.J. Comparative analysis of degassing methods for preparation of pinhole-free membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2025, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, S.; Hartenauer, K.; Tutuş, M. Morphology Behavior of Polysulfone Membranes Made from Sustainable Solvents. Gases 2024, 4, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqadhi, N.; Oldal, D.G.; Gopalsamy, K.; Abdulhamid, M.A.; Szekely, G. Poly(ether-ether-ketone) copolymers featuring sulfonyl moieties for organic solvent nanofiltration membranes. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Yang, C.; Ayaril, N.; Szekely, G. Solvent-Resistant Thin-Film Composite Membranes from Biomass-Derived Building Blocks: Chitosan and 2,5-Furandicarboxaldehyde. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 10, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoumani, I.; Iatridi, Z.; Fidelli, A.M.; Krassa, P.; Kallitsis, J.K.; Bokias, G. Room-Temperature Self-Healable Blends of Waterborne Polyurethanes with 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate-Based Polymers. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Use of improved n-alkyl pyrrolidone solvents. WO2013107822A1.

- Winters, J.; Dehaen, W.; Binnemans, K. N-butyl pyrrolidone/ionic liquid mixtures as benign alternative solvents to N-methyl pyrrolidone for the synthesis of polyaramids. Materials Today Communications 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyimide compositions and methods. US20160208097A1.

- Bayminov, B.A.; Zabegaeva, O.N.; Sapozhnikov, D.A.; Vygodskii, Y.S. Trends in the Synthesis of Polyimides and Their Nanocomposites. Ineos Open 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchalov, A.V.; Bayminov, B.A.; Folomin, A.D.; Zabegaeva, O.N.; Godovikov, I.A.; Kononova, E.G.; Kosolapov, A.F.; Semjonov, S.L.; Vygodskii, Y.S.; Sapozhnikov, D.A. Autocatalytic one-step high-temperature synthesis of carboxylated polyimides for in-situ high performance applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing Soh, L.; Uyin Hong, S.; Zeng Liang, C.; Fen Yong, W. Green solvent-synthesized polyimide membranes for gas separation: Coupling Hansen solubility parameters and synthesis optimization. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Lozano, Á.E.; de la Campa, J.G.; Vygoskii, Y.; Zolotukhin, M.; de Abajo, J.; Garrido, L.; Guzmán, J. Gas Transport Coefficients of Phthalide-Containing High-Tg Glassy Polymers Determined by Gas-Flux and NMR Measurements. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2585–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Glass, T.E.; Lyle, G.D.; McGrath, J.E. Kinetic and mechanistic investigations of the formation of polyimides under homogeneous conditions. Macromolecules 2002, 26, 1344–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, S.; Matsuura, T.; Sasaki, S. Coloration of Aromatic Polyimides and Electronic Properties of Their Source Materials. Polymer Journal 1997, 29, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakov, I.A.; Orlinson, B.S.; Zavialov, D.V.; Mednikov, S.V.; Gurevich, L.M.; Bogdanov, A.I.; Saveliev, E.N.; Alykova, E.A.; Nakhod, M.A.; Pichugin, A.M.; et al. Optically transparent (co)polyimides based on alicyclic diamines with improved dielectric properties. Russian Chemical Bulletin 2023, 72, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Horii, S. Low-CTE Polyimides Derived from 2,3,6,7-Naphthalenetetracarboxylic Dianhydride. Polymer Journal 2007, 39, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, L.; Jin, X.; Hou, M.; He, L.; Lu, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, T. Thermal crosslinking of a novel membrane derived from phenolphthalein-based cardo poly(arylene ether ketone) to enhance CO2/CH4 separation performance and plasticization resistance. Journal of Membrane Science 2019, 586, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, S.V.; Korshak, V.V.; Vygodskii, Y.S.; Zaitsev, V.I. Study of certain principles of the low temperature polycondensation of 3,3-bis-(4-aminophenyl)phthalide and isophtahlic acid chloride in solution. Polymer Science U.S.S.R. 1967, 9, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyakin, N.V.; Rabinovich, I.B.; Rusanov, A.L. Physical Chemistry of the Polycondensation of Polyfunctional Nucleophilic Compounds with Polycarboxylic Acid Derivatives. Russian Chemical Reviews 1985, 54, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Hall, C.G.J.; Thorp, L.R.; Sneddon, H.F. Replacement of Less-Preferred Dipolar Aprotic and Ethereal Solvents in Synthetic Organic Chemistry with More Sustainable Alternatives. Chem Rev 2022, 122, 6749–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, A.; Pethica, B.A.; Somasundaran, P.; Fan, A. Surface and colloid properties of cyclic amides III. Surface activity and micellization of N-butyl-2-pyrrolidone in water. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 1999, 20, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabegaeva, O.N.; Cherepkova, M.A.; Sapozhnikov, D.A. Synthesis of Polyamide-Imides by the Interaction of Terephthaloyl Chloride and 3,3’,4,4’-Diphenyl Ether Tetracarboxylic Acid Dianhydride with Various Diamines. Ineos Open 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, H.; Mushtaq, N.; Chen, G.; Jiang, H.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Fang, X. Transparent polyamide-imide films with high Tg and low coefficient of thermal expansion: Design and synthesis. Polymer 2020, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |