1. Introduction

Electrochromic materials can show a reversible optical change in absorption or transmittance upon electrochemically oxidized or reduced. The main kinds of electrochromic materials include metal oxides (such as WO

3), metal hexacyanoferrates, organic small molecules (such as viologens) and organic polymers (e.g., polyanilines, polythiophenes, and polypyrroles) [

1,

2]. Among these, organic polymers have several advantages such as high coloration efficiency, fast response time, can be fabricated into flexible devices, and easy color tuning [

3,

4,

5,

6]. This technology can be applied to smart windows, anti-glare rear-view mirrors, displays, and eye-wear. Electronically dimmable windows developed by Gentex have been housed on the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.

Triphenylamine (TPA) derivatives are well known for photo and electroactive properties that have found optoelectronic applications as photoconductors, hole-transporters, and light-emitters [

7,

8,

9]. TPAs can be easily oxidized to form stable radical cations, and the oxidation process is always associated with a noticeable change of coloration. In early 1990s, the synthesis and characterization of polyimides and polyamides containing TPA unit were first reported by Imai group [

10,

11]. Since 2005, the Liou’s group and our group disclosed the interesting electrochromic properties of high performance polymers, such as aromatic polyamides and polyimides, carrying the TPA unit as an electrochromic functional moiety [

12,

13,

14]. Then, many TPA-based electrochromic polymers have been reported in the literature [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Yen and Liou have published some comprehensive review papers on the TPA-based electrochromic polymers [

20,

21,

22]. The introduction of bulky groups such as

tert-butyl group [

23,

24,

25] or the electron-donating substituents such as methoxy groups [

26,

27,

28] onto the active sites of triarylamine units reduced the oxidation potential and allowed to obtain more stable radical cations preventing dimerization reactions at these positions.

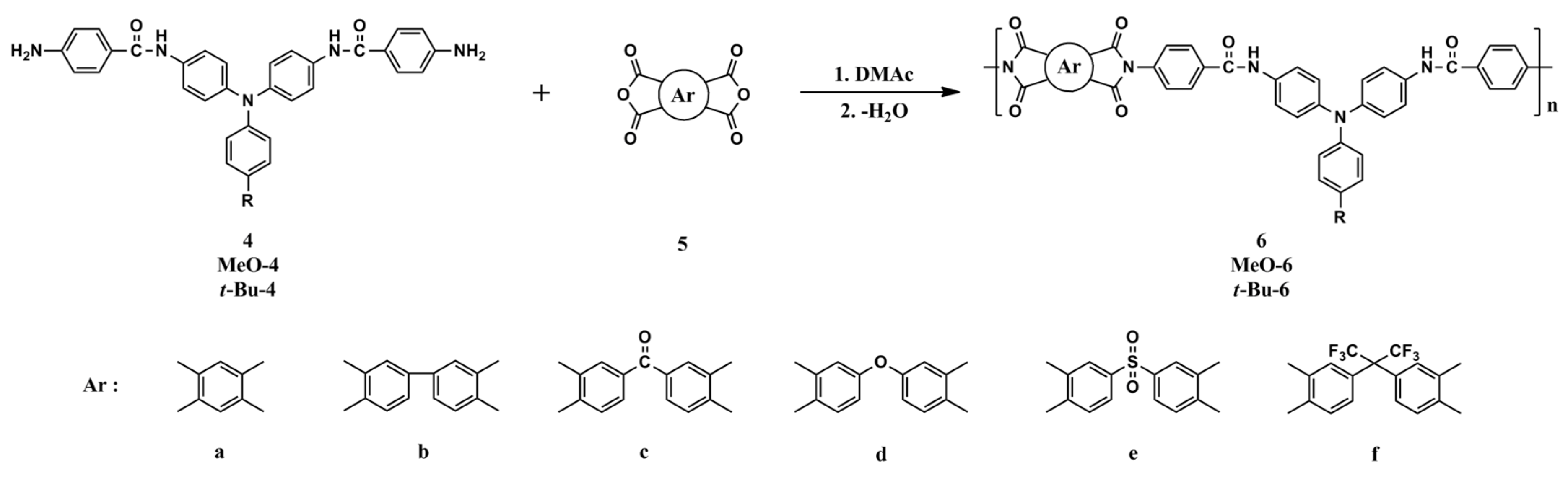

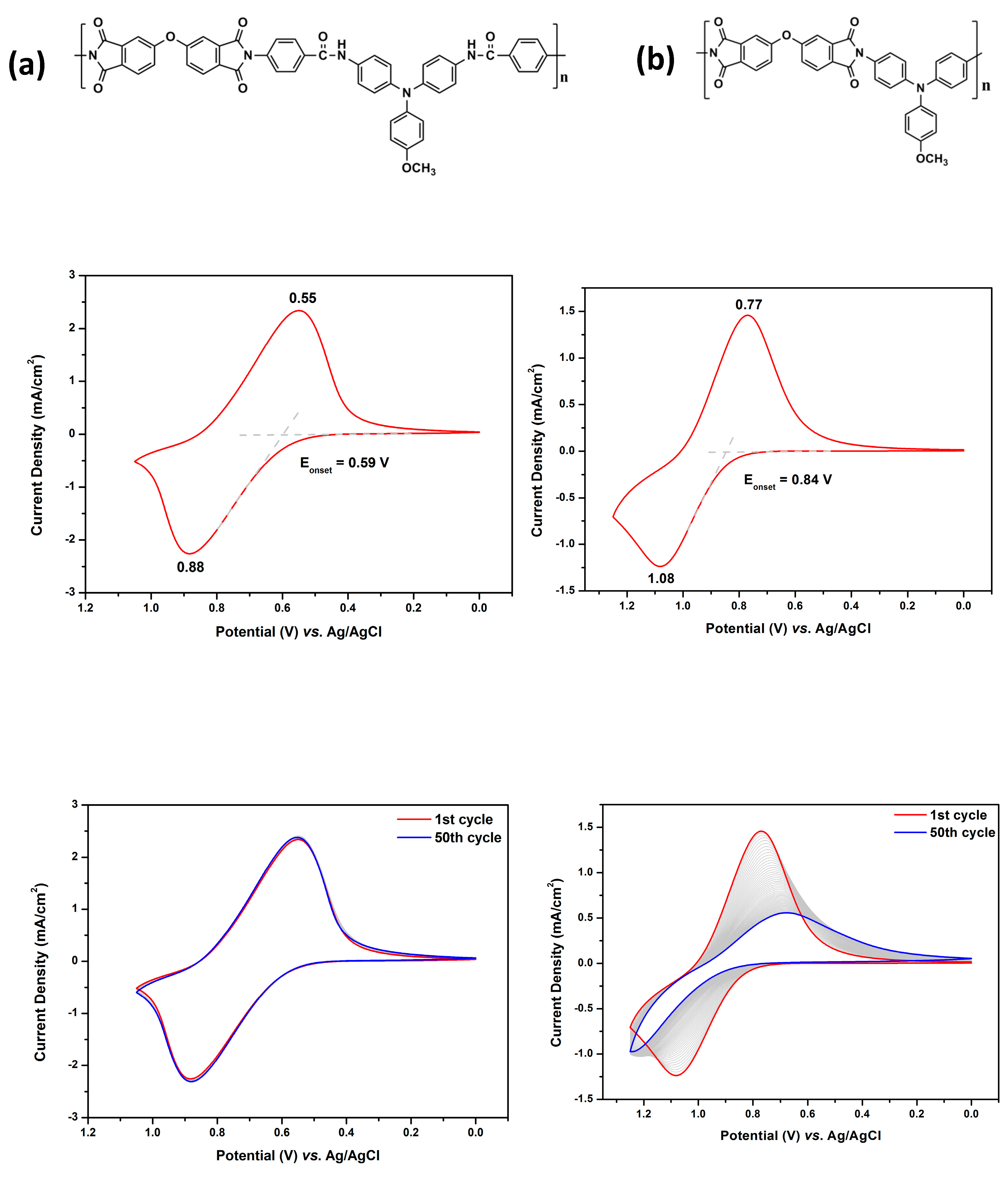

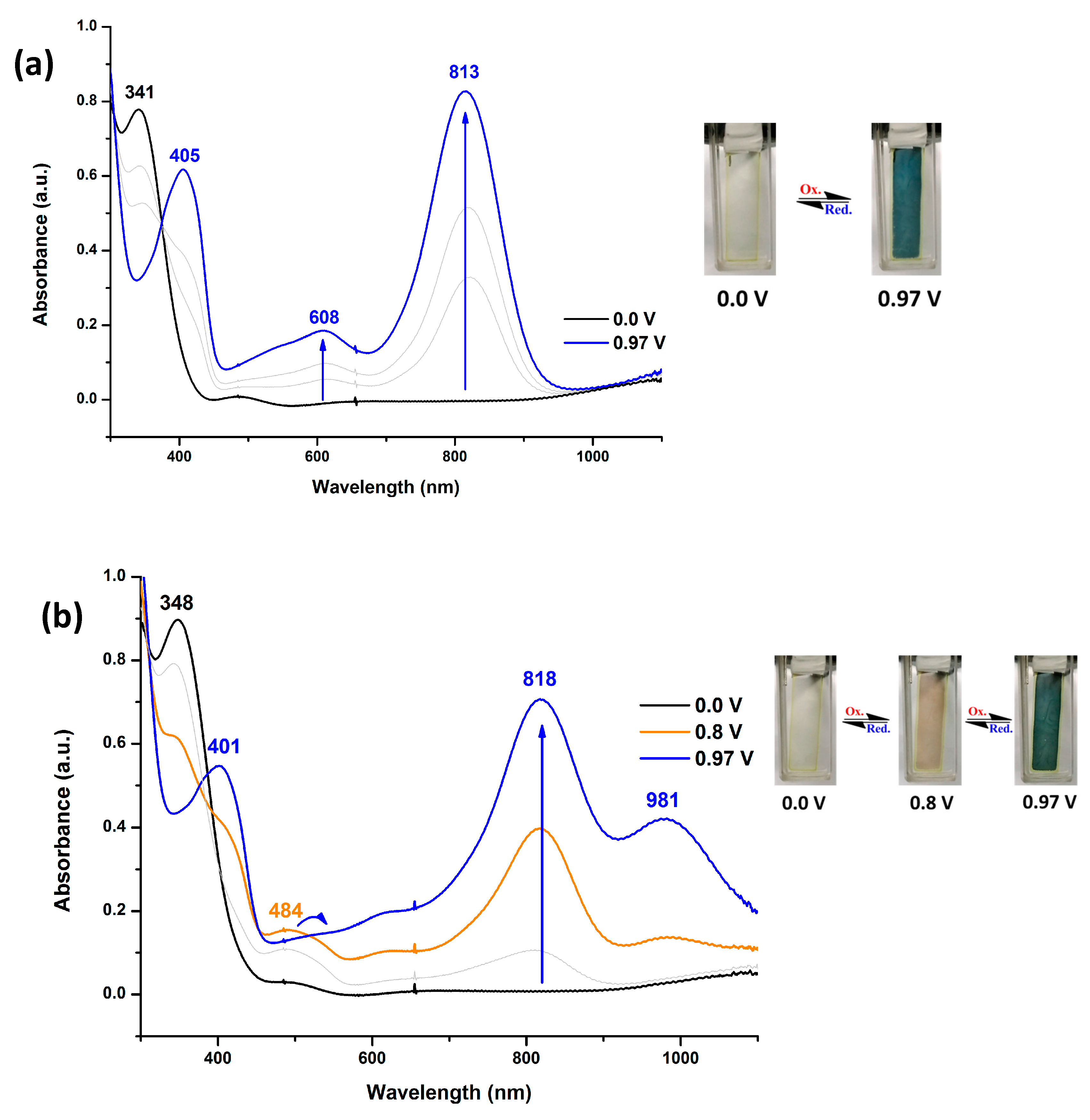

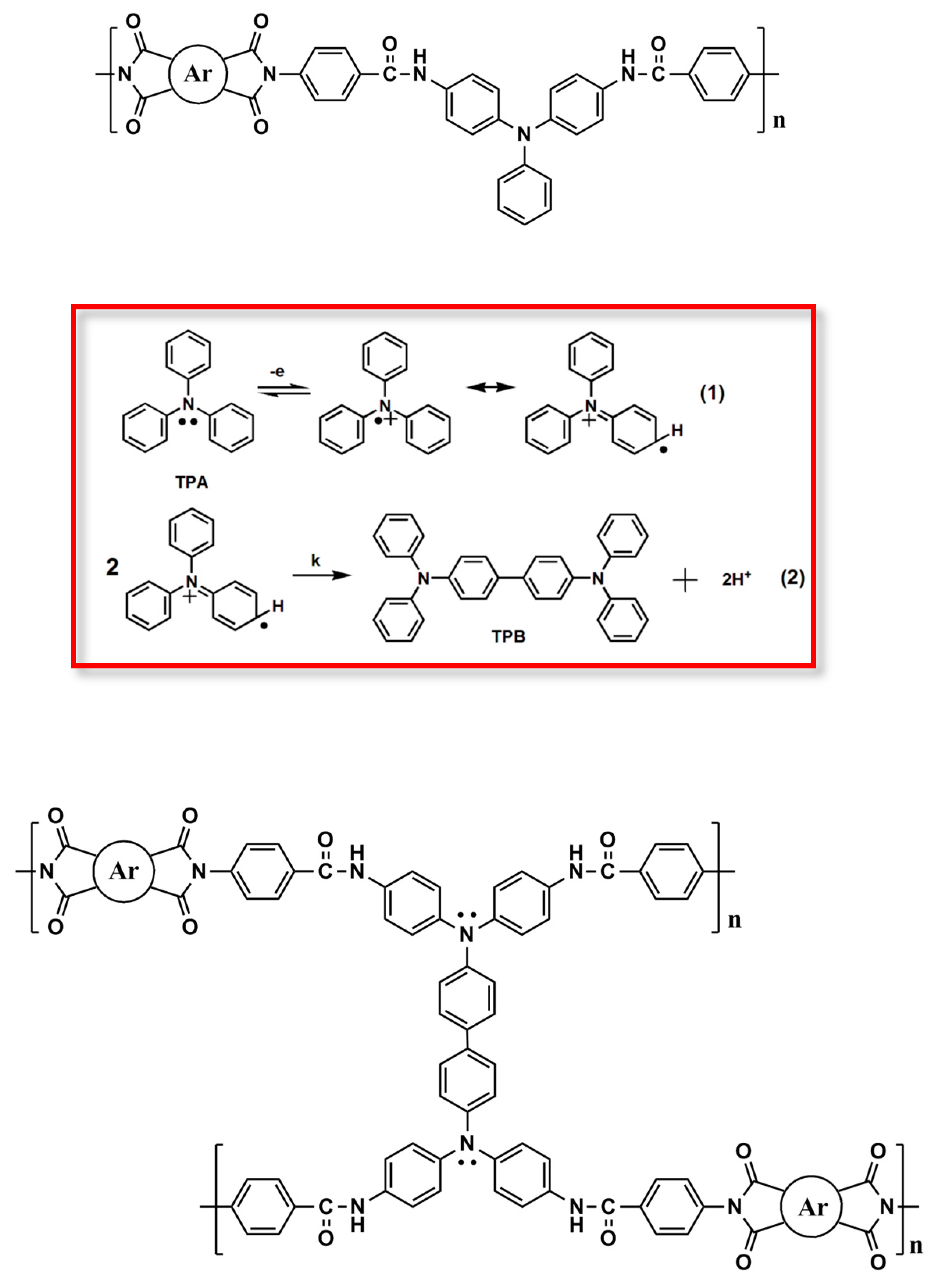

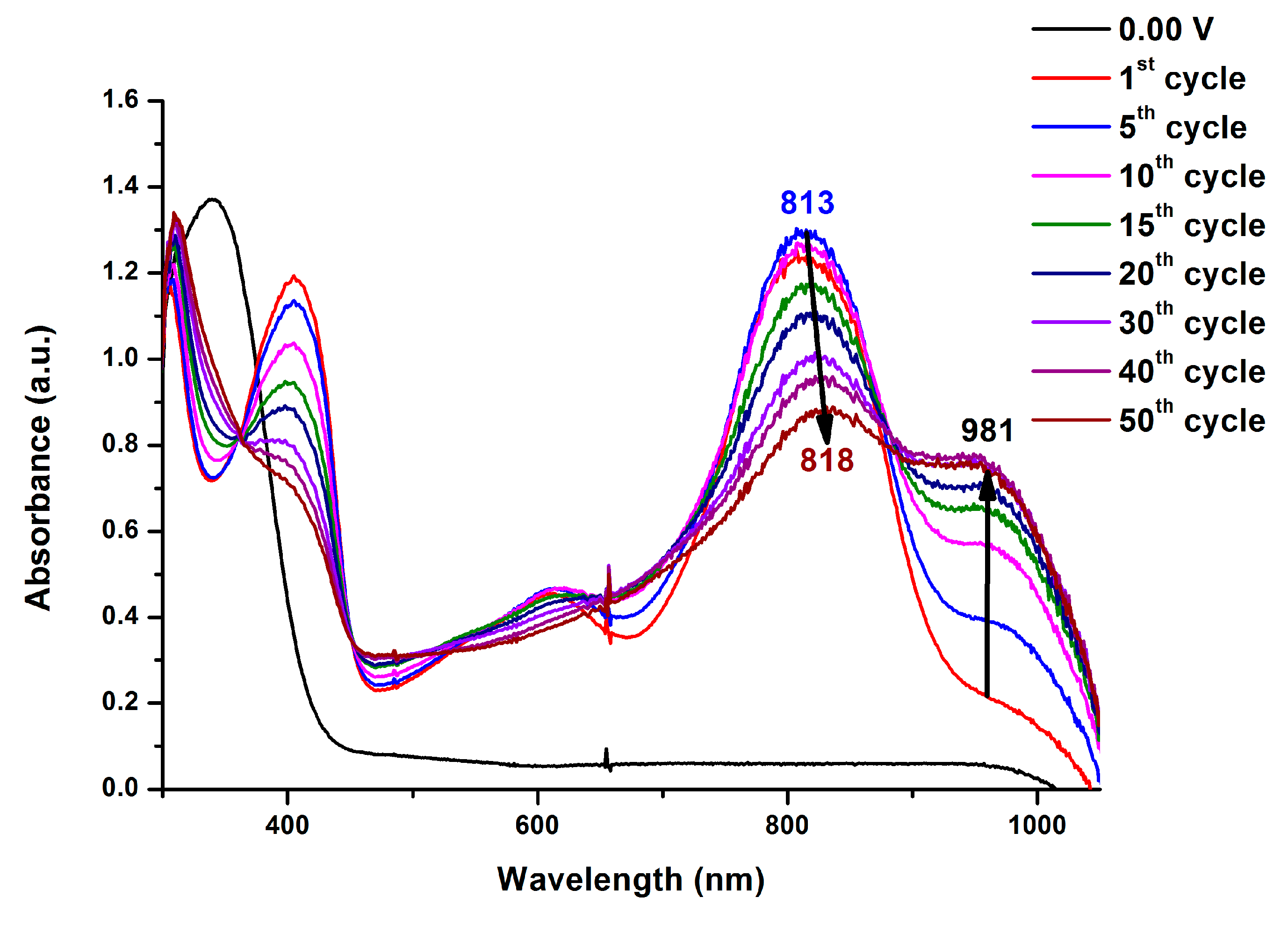

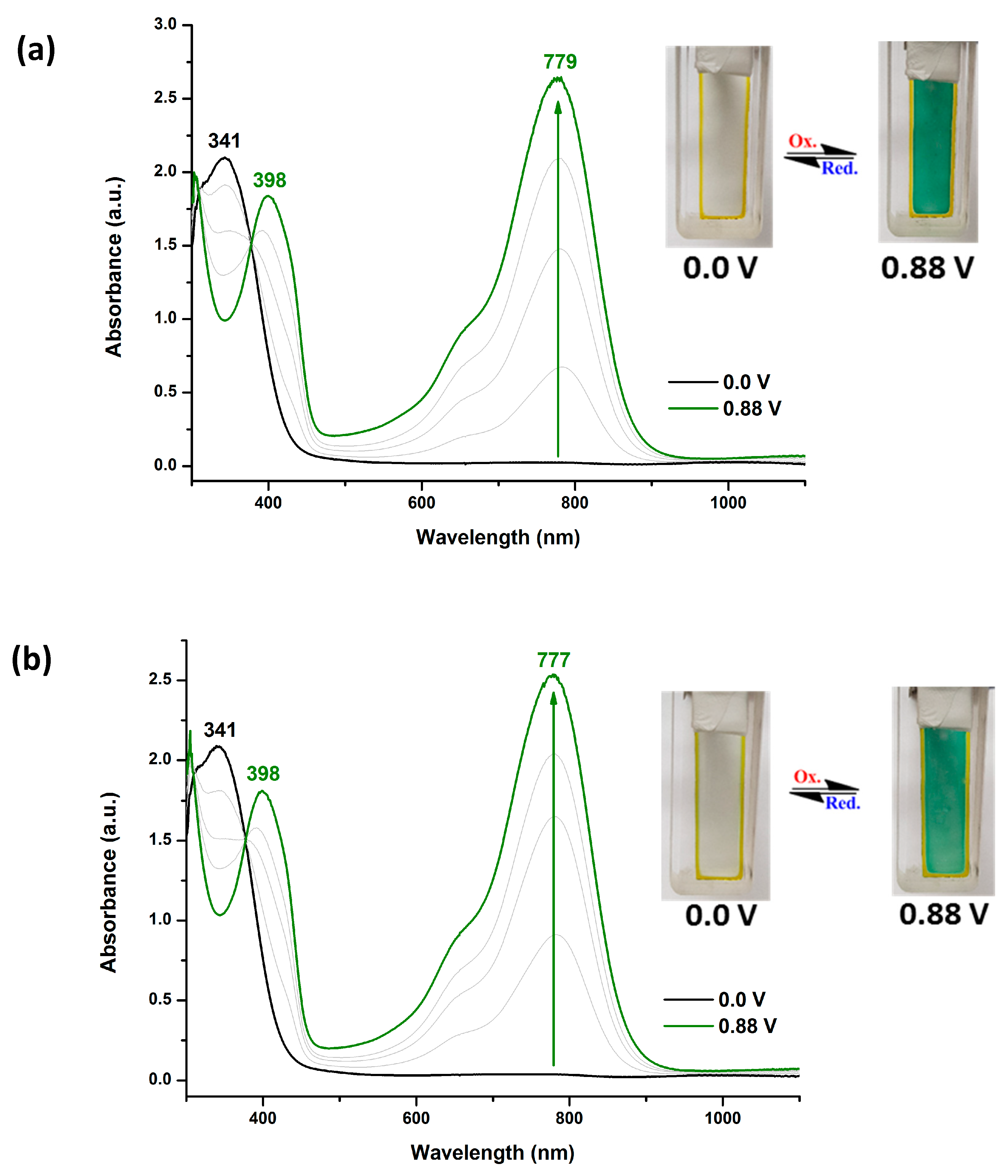

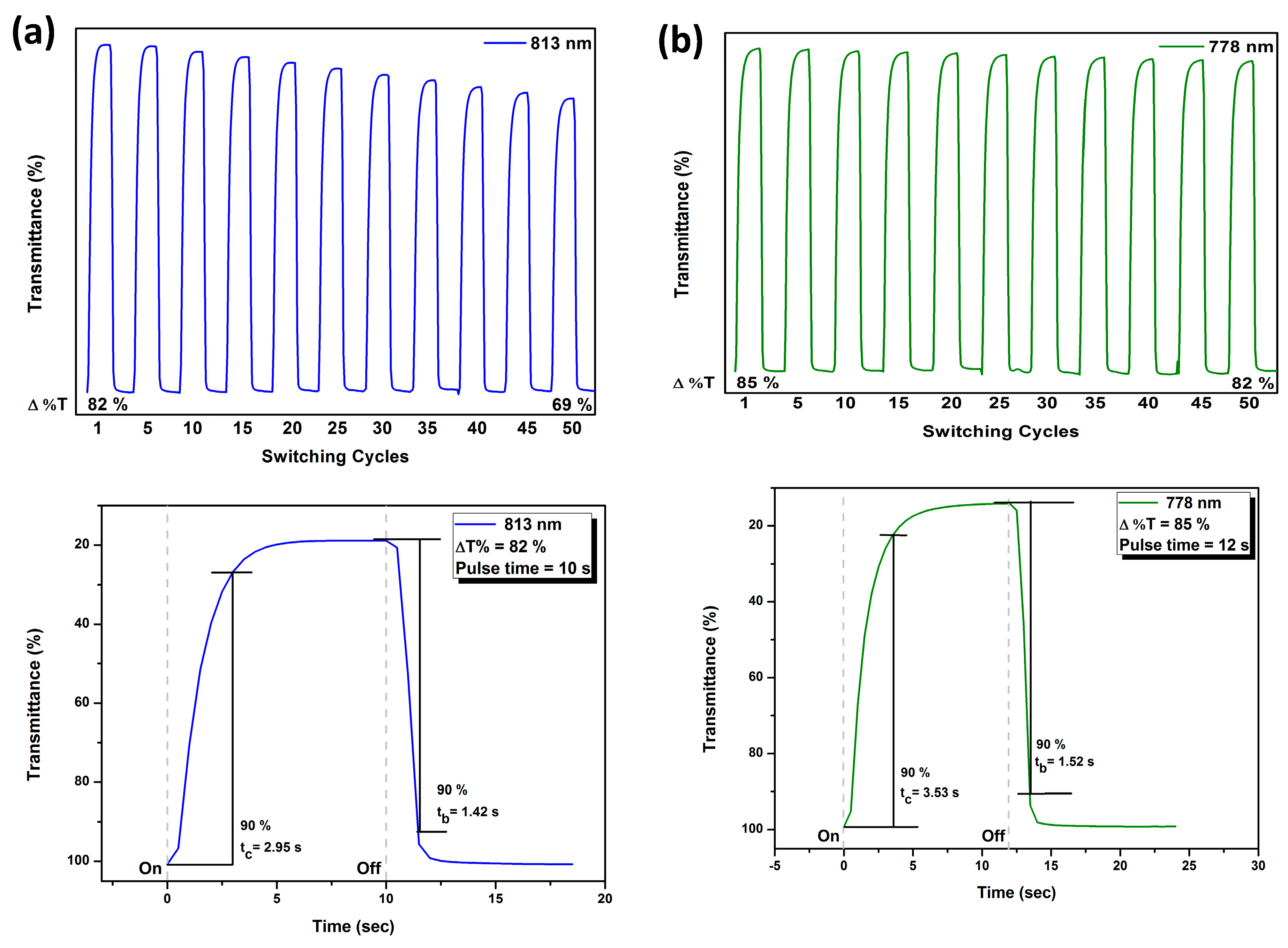

It has been demonstrated that TPA-based polyimides generally exhibited poor electrochemical and electrochromic stability as compared with their polyamide analogs because of the strong electron-withdrawing imide group, which increases the oxidation potential of the TPA unit and destabilizes the resultant amino radical cation upon oxidation. Incorporating a spacer between the TPA core and the imide ring may improve the elec trochemical and elcetrochromic stability of this kind of electroactive polymers. Thus, three new amide-preformed triphenylamine-diamine monomers, namely 4,4’-bis(p-aminobenzamido)triphenylamine (4), 4,4’-bis(p-aminobenzamido)-4”-methoxytriphenylamine (MeO-4) and 4,4’-bis(p-aminobenzamido)-4”-tert-butyltriphenylamine (t-Bu-4), were synthesized and a series of poly(amide-imide)s (PAIs) with main-chain TPA and benzamide moieties were prepared from these diamide-preformed diamine monomers with the corresponding tetracarboxylic dianhydrides. By the incorporation of the benzamide spacer between the TPA and imide units, the resulting PAIs are expected to exhibit enhanced electrochemical and electrochromic properties.

2. Materials and Methods

Aniline (Acros),

p-anisidine (Acros),

p-fluoronitrobenzene (Acros),

p-

tert-butylaniline (AKSci),

p-nitrobenzoyl chloride (Acros), cesium fluoride (CsF, Acros), hydrazine monohydrate (Alpha), 10% palladium on activated carbon (Pd/C, Fluka), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Tedia), and acetic anhydride (Acros) were used as received from commercial sources.

N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, Tedia) was dried over calcium hydride for 24 h, distilled under reduced pressure, and stored over 4 Å molecular sieves in sealed bottles. The aromatic tetracarboxylic dianhydrides including pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA;

5a, TCI), 3,3’,4,4’-biphenyltetracarboxylic dianhydride (BPDA;

5b Oxychem), 3,3’,4,4’-benzophenonetetracarboxylic dianhydride (BTDA;

5c Oxychem), 4,4’-oxydiphthalic anhydride (ODPA;

5d, Oxychem), 3,3’,4,4’-diphenylsulfonetetracarboxylic dianhydride (DSDA;

5e, Oxychem), 2,2-bis(3,4-dicarboxyphenyl)hexafluoropropane dianhydride (6FDA;

5f, Hoechst Celanese) were purified by dehydration at 250

oC in vacuum for 3 h. Other reagents and solvents were used as received from commercial sources. According to a reported synthetic procedure [

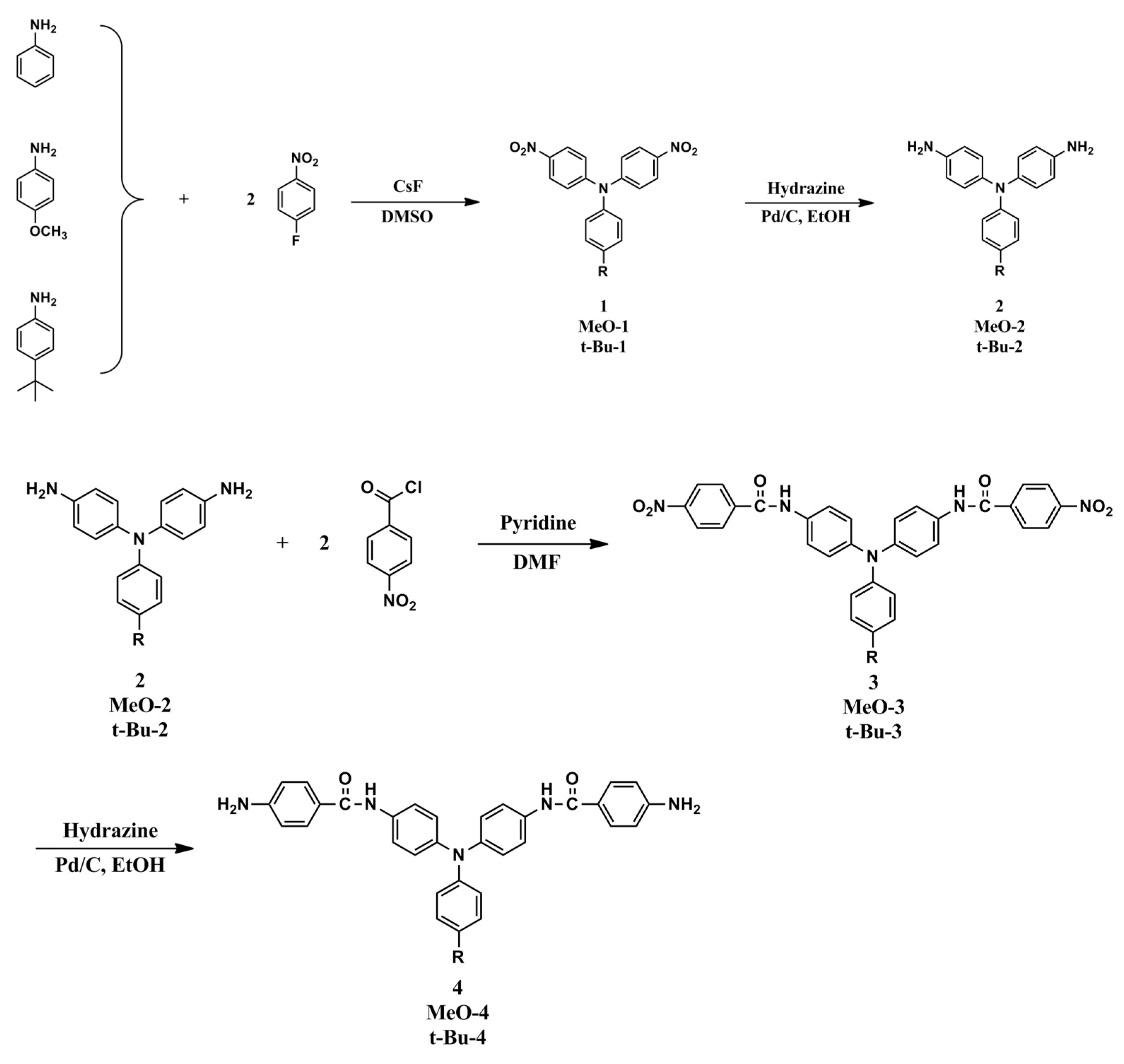

14], 4,4’-diaminotriphenylamine (

2), 4,4’-diamino-4”-methoxytriphenylamine (

MeO-2), and 4,4’-diamino-4”-

tert-butyltriphenylamine (

t-Bu-2) were synthesized via the fluoro-displacement of

p-fluoronitrobenzene with aniline,

p-anisidine and

p-

tert-butylaniline in the presence of CsF in DMSO, followed by Pd/C-catalyzed hydrazine reduction of the intermediate dinitro compounds 4,4’-dinitrotriphenylamine (

1), 4-methoxy-4’,4”-dinitrotriphenylamine (

MeO-1), and 4-

tert-butyl-4’,4”-dinitrotriphenylamine (

t-Bu-1) in ethanol, respectively.

2.1. Synthesis of 4,4’-bis(p-nitrobenzamido)triphenylamine (3), 4,4’-bis(p-nitrobenzamido)-4”-methoxytriphenylamine (MeO-3) and 4,4’-bis(p-nitrobenzamido)-4”-tert-butyltriphenylamine (t-Bu-3)

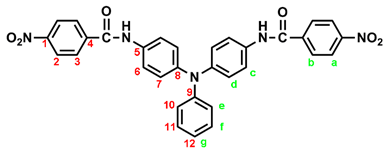

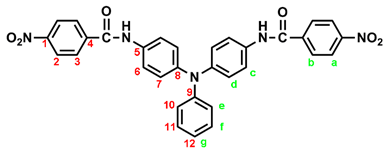

In a 250 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a stirring bar, 2.75 g (0.01 mol) of 4,4’-diaminotriphenylamine and 3 mL pyridine were dissolves in 30 mL DMF. A solution of 4.53 g (0.024 mol) of p-nitrobenzoyl chloride in 20 mL DMF was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h and then poured into 600 mL of mixture of methanol and water (2:1). The precipitated solid was collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol, and dried to give 4.36 g (76 %) of diamide-dinitro compound 3 as dark red crystals with a melting point of 237~239 oC (by DSC). IR (KBr): 3282 cm–1 (amide N–H stretch), 1651 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch), 1595, 1350 cm–1 (nitro –NO2 stretch). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 7.00 (m, 3H, Hg + He), 7.05 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hd), 7.30 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Hf), 7.73 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hc), 8.18 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hb), 8.35 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Ha), 10.55 (s, 2H, amide N–H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 163.57 (amide carbon), 149.10 (C1), 147.35 (C9), 143.36 (C8), 140.61 (C5), 133.99 (C4), 129.43 (C11), 129.12 (C3), 124.22 (C7), 123.53 (C2), 122.65 (C10), 122.27 (C12), 121.50 (C6).

|

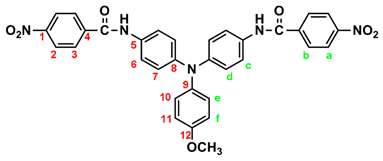

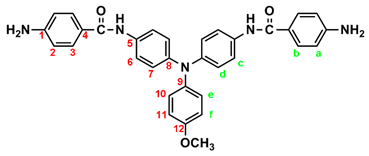

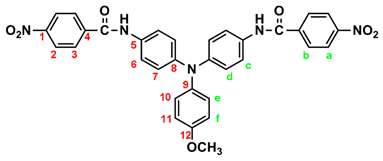

By a similar procedure, diamide-dinitro compound MeO-3 was synthesized from the condensation of 3.05 g (0.01 mol) of 4,4’-diamino-4”-methoxytriphenylamine (MeO-2) and 4.53 g (0.024 mol) of p-nitrobenzoyl chloride as orange powder (4.23 g; 70 % yield) with a melting point of 219~221 oC. IR (KBr): 3286 cm–1 (amide N–H stretch), 1651 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch), 1600, 1350 cm–1 (nitro –NO2 stretch). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 3.75 (s, 3H, methoxy), 6.94 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H, He), 6.96 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hd), 7.03 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H, Hf), 7.68 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hc), 8.18 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, Hb), 8.36 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, Ha), 10.05 (s, 2H, amide N–H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 163.44 (amide carbon), 155.71 (C12), 149.06 (C1), 143.96 (C8), 140.64 (C5), 140.09 (C9), 133.05 (C4), 129.08 (C3), 126.45 (C11), 123.51 (C2), 122.60 (C7), 121.73 (C6), 115.01 (C10), 55.24 (–OCH3).

|

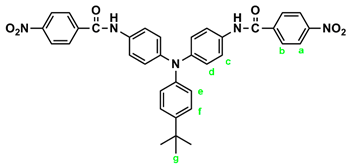

Similarly, diamide-dinitro compound t-Bu-3 was synthesized from the condensation of 3.31 g (0.01 mol) of 4,4’-diamino-4”-tert-butyltriphenylamine (t-Bu-2) and 4.53 g (0.024 mol) of p-nitrobenzoyl chloride as dark-red crystals (5.35 g; 85 % yield) with a melting point of 223~224 oC. IR (KBr): 3300 cm–1 (amide –N–H stretch), 1655 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch), 1596, 1350 cm–1 (nitro –NO2 stretch). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 1.27 (s, 9H, Hg), 6.94 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, He), 7.02 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hd), 7.32 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, Hf), 7.71 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hc), 8.18 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H, Hb), 8.36 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 4H, Ha), 10.53 (s, 2H, amide N–H).

2.2. Synthesis of 4,4’-bis(p-aminobenzamido)triphenylamine (4), 4,4’-bis(p-aminobenzamido)-4”methoxytriphenylamine (MeO-4) and 4,4’-bis(p-aminobenzamido)-4”-tert-butytriphenylamine (t-Bu-4)

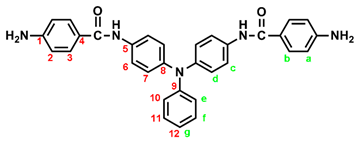

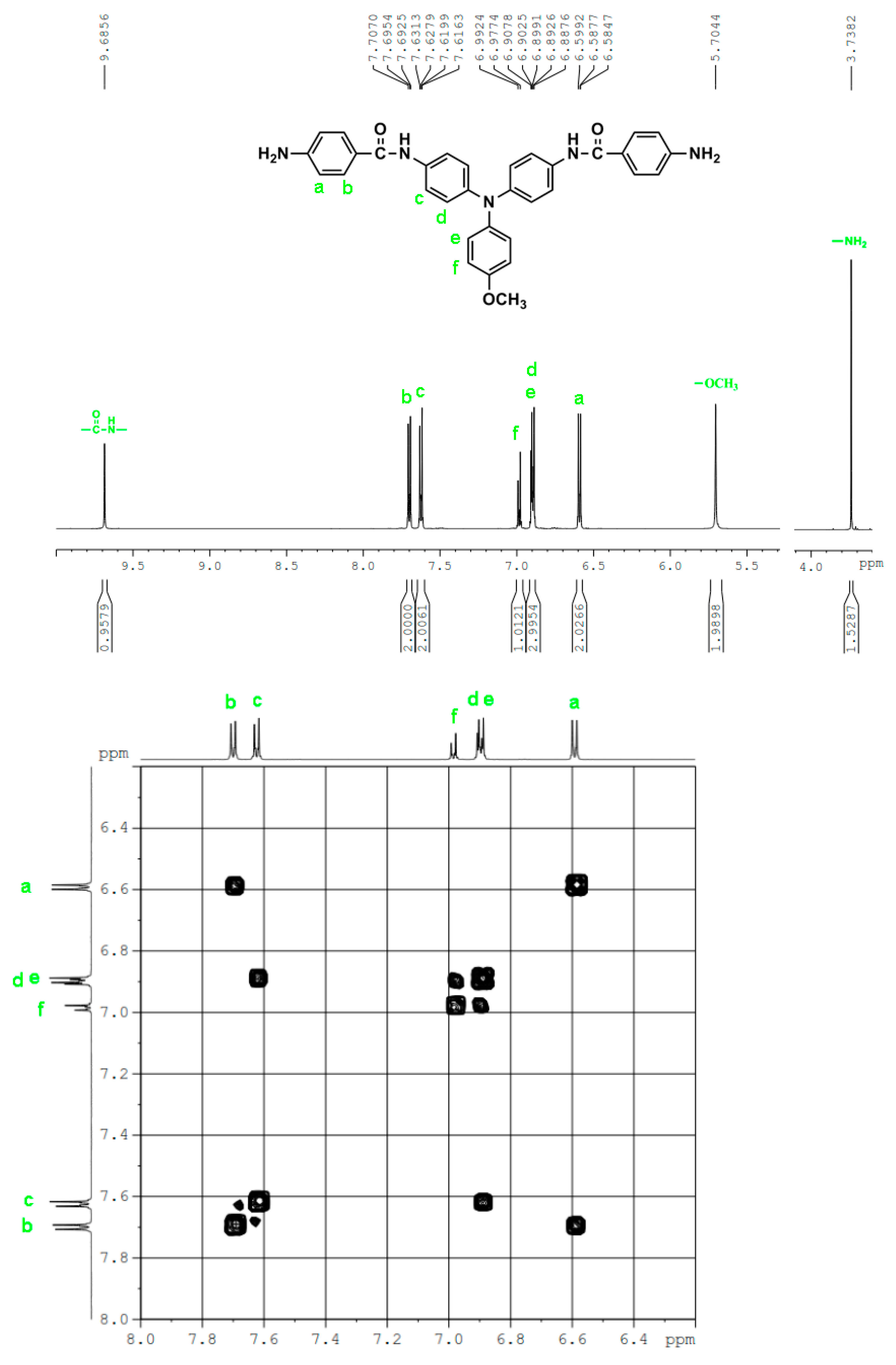

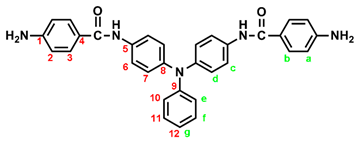

In a 100 mL three-neck round-bottom flask equipped a stirring bar, 1.72 g (0.003 mol) of diamide-dinitro compound 3 and 0.15 g of 10% Pd/C were dispersed in 50 mL of ethanol. The equivalent amount of hydrazine was added to the mixture and the solution was stirred at a reflux temperature for about 6 h. The solution was then filtered to remove Pd/C, and the filtrate was concentrated in a rotatory evaporator and cooled to precipitate the product that was collected by filtration and dried in vacuum to give 1.08 g (70 %) of diamide-diamino compound 4 with a melting point of 261~264 oC. IR (KBr): 3350, 3300 cm–1 (amide and amino N–H stretch), 1630 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 5.72 (s, 4H, –NH2), 6.60 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, Ha), 6.92-6.94 (two overlapped doublets, 3H, Hg + He), 6.98 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hd), 7.24 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Hf), 7.68 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hc), 7.70 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, Hb), 9.74 (s, 2H, amide N–H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 165.04 (amide carbon), 152.03 (C1), 147.76 (C9), 142.29 (C8), 135.23 (C5), 129.23 (C3,C11), 124.41 (C7), 121.68 (C10), 121.43 (C12), 121.38 (C6), 121.12 (C4), 112.51 (C2).

|

By a similar procedure, diamide-diamines MeO-4 and t-Bu-4 were synthesized by hydrazine Pd/C-catalyzed reduction of diamide-dinitro compounds MeO-3 and t-Bu-3, respectively. The spectroscopic data are shown below.

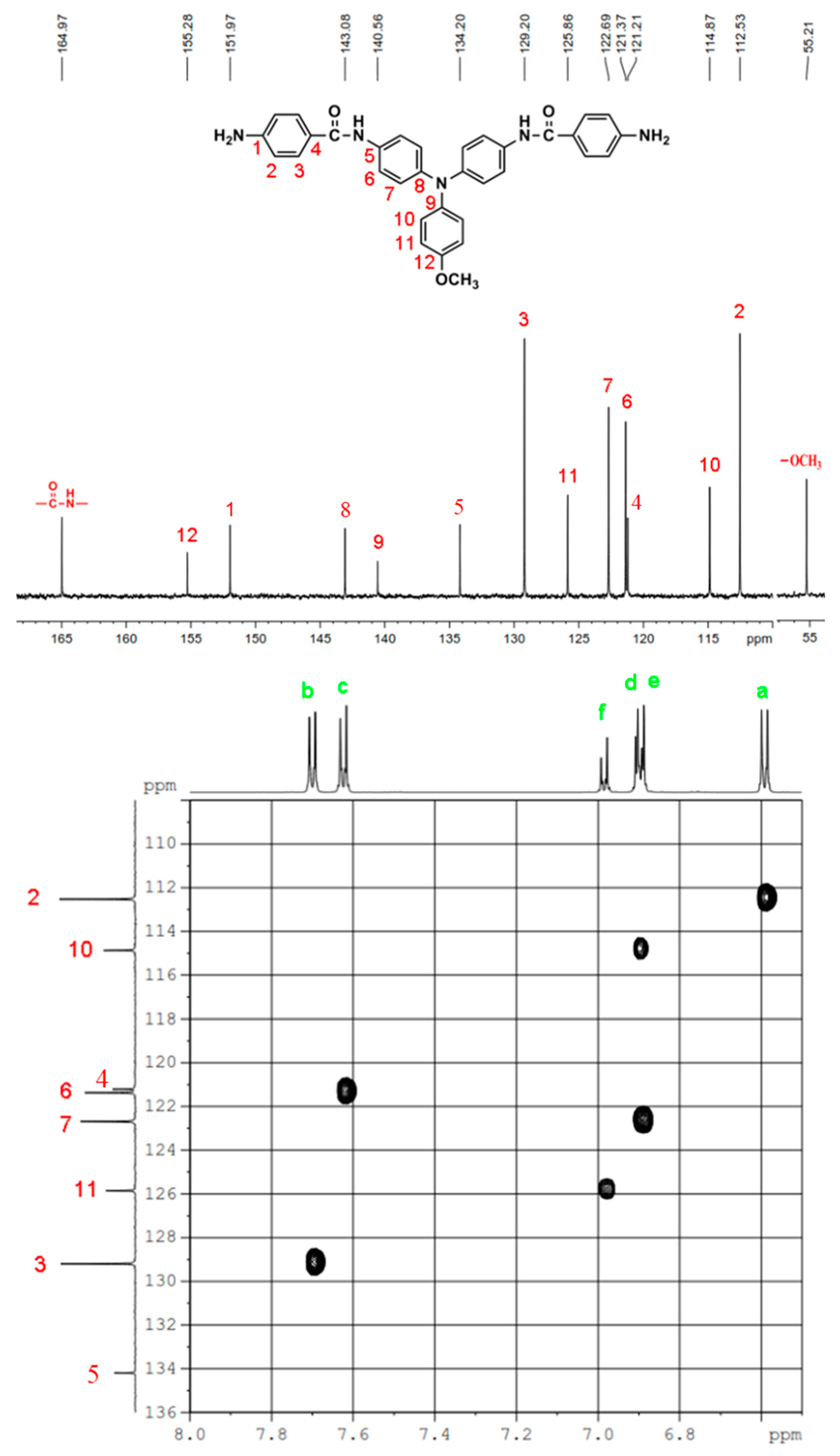

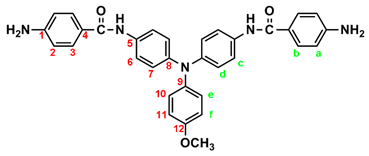

IR for MeO-4 (KBr): 3500~3300 cm–1 (amine and amide N–H stretch), 1623 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch). 1H NMR for MeO-4 (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 3.75 (s, 3H, methoxy), 5.70 (s, 4H, –NH2), 6.59 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H, Ha), 6.90 (two overlapped doublets, 6H, Hd + He), 6.98 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 4H, Hf), 7.62 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 4H, Hc), 7.70 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H, Hb), 9.69 (s, 2H, amide N–H). 13C NMR for MeO-4 (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 164.97 (amide carbon), 155.26 (C12), 151.97 (C1), 143.08 (C8), 140.56 (C9), 134.20 (C5), 129.20 (C3), 125.86 (C11), 122.69 (C7), 121.37 (C6), 121.21 (C4), 114.87 (C10), 112.53 (C2), 55.21 (–OCH3)

|

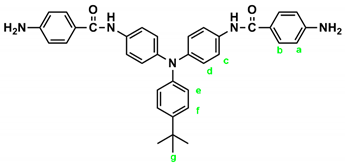

IR for t-Bu-4 (KBr): 3500~3300 cm–1 (amine and amide N–H stretch), 1623 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch). 1H NMR for t-Bu-4 (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 1.27 (s, 9H, Hg), 5.72 (s, 4H, –NH2), 6.60 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H, Ha), 6.89 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H, He), 6.95 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hd), 7.28 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H, Hf), 7.66 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 4H, Hc), 7.70 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H, Hb), 9.72 (s, 2H, amide N–H).

2.3. Synthesis of Poly(amide-imide)s

The PAIs were prepared from various tetracarboxylic dianhydrides (PMDA, BPDA, BTDA, ODPA, DSDA, and 6FDA) with amide-performed diamino compounds 4, MeO-4 and t-Bu-4, respectively, by a conventional two-step method via thermal or chemical imidization reaction. The synthesis of PAI 6f is described as an example. Into a solution of amide-performed diamino compound 4 (0.5362 g; 1.04 mmol) in 9.5 mL anhydrous DMAc in a 50 mL round-bottom flask, 0.4638 g (1.04 mmol) of 6FDA (5f) was added in one portion. Thus, the solid content of the solution is approximately 10 wt%. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h to yield a viscous poly(amide-amic acid) (PAA) solution with an inherent viscosity of 0.68 dL/g, measured in DMAc at concentration of 0.50 g/dL at 30 oC. The poly(amide-amic acid) film was obtained by casting from the reaction polymer solution onto a glass Petri dish and drying at 90 oC overnight. The poly(amide-amic acid) in the form of solid film was converted to the PAI film by successive heating at 150 oC for 30 min, 200 oC for 30 min, and 250 oC for 1 h. For chemical imidization method, 2 mL of acetic anhydride and 1mL of pyridine were added to the PAA solution obtained by a similar process as above, and the mixture was heated at 100 oC for 1 h to effect a complete imidization. The homogenous polymer solution was poured slowly into an excess of methanol giving rise to a precipitate that was collected by filtration, washed thoroughly with hot water and methanol, and dried. The inherent viscosity of the resulting PAI 6f was 0.64 dL/g, measured in DMAc at concentration of 0.50 g/dL at 30 oC. A polymer solution was made by the dissolution of about 0.5 g of the PAI sample in 4 mL of hot DMAc. The homogeneous solution was poured into a glass Petri dish, which was placed in a 90 oC oven overnight for slow release of solvent, and then the film was stripped off from the glass substrate and further dried in vacuum at 160 oC for 6 h. The IR spectrum of 6f (film) exhibited characteristic imide and amide absorption bands at 1786 cm–1 (asymmetrical imide C=O stretch), 1725 cm–1 (symmetrical imide stretch), and 1650 cm–1 (amide C=O stretch).

2.4. Measurements

Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Horiba FT-720 FT-IR spectrometer. 1H spectra were measured on a Bruker Avance III HD-600 MHz NMR spectrometer. The inherent viscosities were determined with a Cannon-Fenske viscometer at 30 oC. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis was carried out on a Waters chromatography unit interfaced with a Waters 2410 refractive index detector at 3 mg/mL concentration. Two Waters 5 μm Styragel HR-2 and HR-4 columns (7.8 mm I. D. x 300 mm) were connected in series with NMP as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min at 50 oC and were calibrated with polystyrene standards. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed with a Perkin-Elmer Pyris 1 TGA. Experiments were carried out on approximately 3−5 mg of polymer film samples heated in flowing nitrogen or air (flow rate = 40 cm3/min) at a heating rate of 20 oC/min. DSC analyses were performed on a Perkin-Elmer DSC 4000 at a scan rate of 20 oC/min in flowing nitrogen. Electrochemistry was performed with a CHI 750A electrochemical analyzer. Voltammograms are presented with the positive potential pointing to the left and with increasing anodic currents pointing downwards. Cyclic voltammetry was conducted with the use of a three-electrode cell in which ITO (polymer films area about 0.5 cm × 2.0 cm) was used as a working electrode. All cell potentials were taken with the use of a home-made Ag/AgCl, KCl (sat.) reference electrode. Ferrocene was used as an external reference for calibration (+0.44 V vs. Ag/AgCl). Spectroelectrochemistry analyses were carried out with an electrolytic cell, which was composed of a 1 cm cuvette, ITO as a working electrode, a platinum wire as an auxiliary electrode, and a home-made Ag/AgCl, KCl (sat.) reference electrode. Absorption spectra in the spectroelectrochemical experiments were also measured with an Agilent 8453 UV-visible photodiode array spectrophotometer.