1. Introduction

The evolution of organic electronics, deeply rooted in polymer chemistry and nanotechnology, can be traced back to the seminal demonstration of the electrical conductivity of halogen-modified polyacetylene in 1977. This marked a crucial turning point, fostering a multidisciplinary approach that integrated principles from solid-state physics, molecular physics, organic and inorganic chemistry, electronics, and printing technologies. Among the various polymers, polyanilines (PANI), characterized by the repeating unit C6H4(NH)C6H4, have emerged as focal points in this dynamic field.

Initially synthesized through the oxidative polymerization of aniline monomers, PANI exhibits diverse electrical conductivity levels based on the degree of oxidation. The pivotal moment in 1977, when Higger, McDiarmid, and Shirakawa showcased the remarkable electrical conductivity of halogen-modified polyacetylene, laid the foundation for the rapid progress in polymer chemistry and nanotechnology. Subsequent studies delved into the development of organic electronics, amalgamating principles from solid-state and molecular physics, organic and inorganic chemistry, electronics, and printing technologies. The attention naturally gravitated towards polyfunctional compounds capable of both electrical conductivity and optoelectronic properties.

Polyanilines (PANI) are a class of conductive polymers that have gained significant attention due to their unique physical and chemical properties. PANI has the C6H4(NH)C6H4 repeating unit and can be synthesized by oxidative polymerization of aniline monomers. The resulting polymer can have various degrees of oxidation, leading to varying electrical conductivity and other properties [

1,

2,

3].

In addition to electrical properties, PANI has been shown to exhibit fluorescence, which makes them a promising material for optoelectronic applications [

4,

5,

6]. The fluorescence of PANI is due to the presence of conjugated double bonds in the polymer backbone, which enables efficient energy transfer and emission of light in the visible range [

7]. This property opens up possibilities for the development of PANI-based fluorescent sensors, light-emitting devices, and imaging agents.

Extensive research has been dedicated to the photovoltaic properties of PANI-based thin films and copolymers. Thin-film photoresistors, leveraging PANI, have been fabricated and characterized for quantum efficiency and carrier mobility [

8]. Moreover, the solubility of modified PANI aligns with modern printing technologies in organic electronics [

9,

10,

11], offering cost-effective and scalable manufacturing approaches such as inkjet printing and roll-to-roll processing. This has facilitated the production of PANI-based electronic components, including solar cells and optoelectronic devices, showcasing promising performance [

12,

13].

In the broader landscape of organic electronics, a burgeoning field over the last few decades, PANI holds a unique position. Its combination of electrical conductivity, fluorescence, and photovoltaic properties renders it attractive for diverse applications. This article aims to delve into the fluorescence spectroscopy and photovoltaic properties of PANI-based thin films and copolymers, aiming to enhance our understanding of their behavior and unlock their full potential in optoelectronic devices.

Simultaneously, the field of organic electronics has witnessed rapid development, encompassing devices like organic solar batteries, organic light-emitting diodes, thin-film field-effect transistors, and more. Electrically conductive conjugated organic compounds are considered pivotal for these applications. In this context, polyaniline (PANI) stands out as an electrically conductive polymer with stable characteristics, albeit with challenges such as insolubility in typical organic solvents. Efforts to address this involve the introduction of side functional groups into the polymer. Copolymerization of aniline and its derivatives has shown promise, as seen in the case of copolymers of aniline and o-/m-aminoacetophenone, which exhibit good conductivity and increased solubility compared to PANI [

14].

Furthermore, the inclusion of indole-based polymers in copolymers with aniline adds another dimension to this exploration. Indole-based polymers are known for their excellent thermal stability, high luminescence quantum yield, and low decomposition rate, making them significant in various applications [

15]. The recent success in polymeranalogous transformations of 2-[2-chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl]aniline has led to the formation of polyindoles with high thermal stability. These polyindoles, when copolymerized with aniline, offer a unique combination of properties.

In conclusion, this work focuses on copolymers derived from aniline and 2-[2-chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl]aniline with varying compositions, aiming to combine polyaniline and polyindole fragments. This novel modification is anticipated to significantly impact the properties of the final materials, opening avenues for enhanced applications in the realm of organic electronics. As the field continues to evolve, the synthesis of electroactive polyconjugated polymers remains a pertinent and challenging area, with the goal of surpassing the capabilities of PANI for both scientific and practical purposes.

2. Materials and Methods

Aniline (Sigma-Aldrich) was freshly distilled under pressure before use in experiments. Dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) were distilled prior to use. Ammonium persulfate ((NH

4)

2S

2O

8), hydrochloric acid (HCl), phosphorus anhydride (P

2O

5), and orthophosphoric acid (H

3PO

4) were used without additional purification. 2-[2-Chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl]aniline was obtained by the method described previously, and all its spectral characteristics agree with those presented in the literature [

16].

UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu Spectrophotometer 2600 in DMSO solution at 298 K, at wavelengths ranging from 190 to 900 nm (slit width - 2.0 nm, scanning speed - fast), using a 1 cm thick quartz tube. Fluorescence spectral analysis was conducted using an RF-5301 PC Shimadzu spectrofluorophotometer in DMSO solution at 298 K with the following hardware: power supply unit HY3005-2, GW Instek GDM-6245 multimeter as the ammeter, and a Hamamatsu LC8 UV light source with a wavelength of 365 nm.

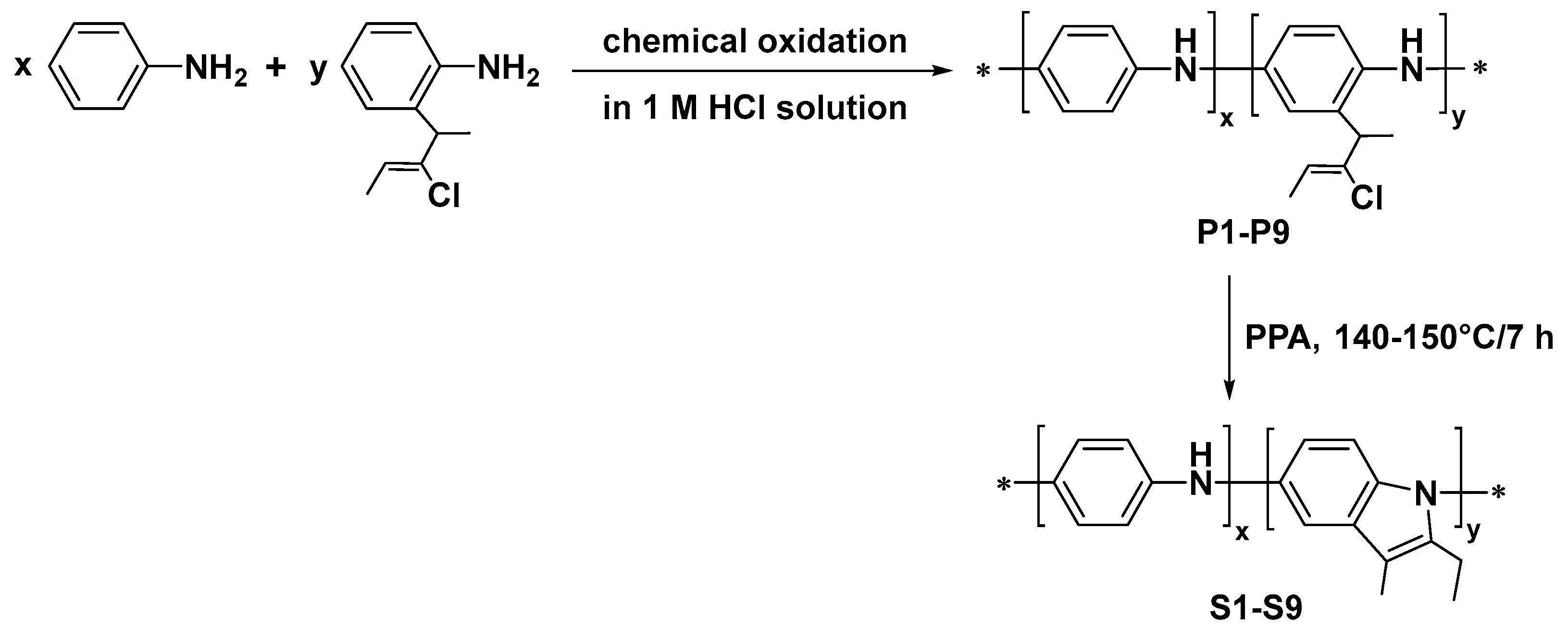

Each poly(Ani-co-ClPA), for example, the P1 copolymer, was prepared by the following procedure: 9.00 mmol of aniline (Ani) (0.81 g) and 0.90 mmol of 2-[2-chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl]aniline (ClPA) (0.19 g) were dissolved in 50 mL of 1 M HCl. A solution of 4.00 g APS in 50 mL of 1 M HCl was added dropwise into the first solution. The polymerization reaction was carried out at room temperature for 24 h to completion. After completion of the polymerization process, the resulting mixture was filtered and treated with 1.0 M HCl followed by double ethanol treatment. This procedure was performed repeatedly until the filtrate turned colorless. After that, the precipitate was treated with excess ammonia solution (1 M) for 24 h and then washed with water. The product was dried at 60 °C in vacuo to give P1. A similar procedure was followed to synthesize copolymer P2 (the starting molar ratio of Ani and ClPA was 7:1), copolymer P3 (Ani:ClPA = 5:1), copolymer P4 (Ani:ClPA = 3:1), copolymer P5 (Ani:ClPA = 1:1), copolymer P6 (Ani:ClPA = 1:3), copolymer P7 (Ani:ClPA = 1:5), copolymer P8 (Ani:ClPA = 1:7), and copolymer P9 (Ani:ClPA = 1:9).

S1-S9 were obtained by intramolecular cyclization of copolymers P1-P9 which was performed by the method described previously [

17]. 1.0 g of copolymers P1-P9 in 10.0 g of polyphosphoric acid (PPA) was heated for 5–6 h at 140–150 °C with stirring. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, then water was added. The resulting polymer precipitated. Then it was filtered off, washed with 1M aqueous ammonia solution, water, chloroform, and again with water. The resulting black powder was dried until constant weight.

The spectral characteristics matched those described earlier [

18,

19]. The process of P1-P9 and S1-S9 preparation is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Results

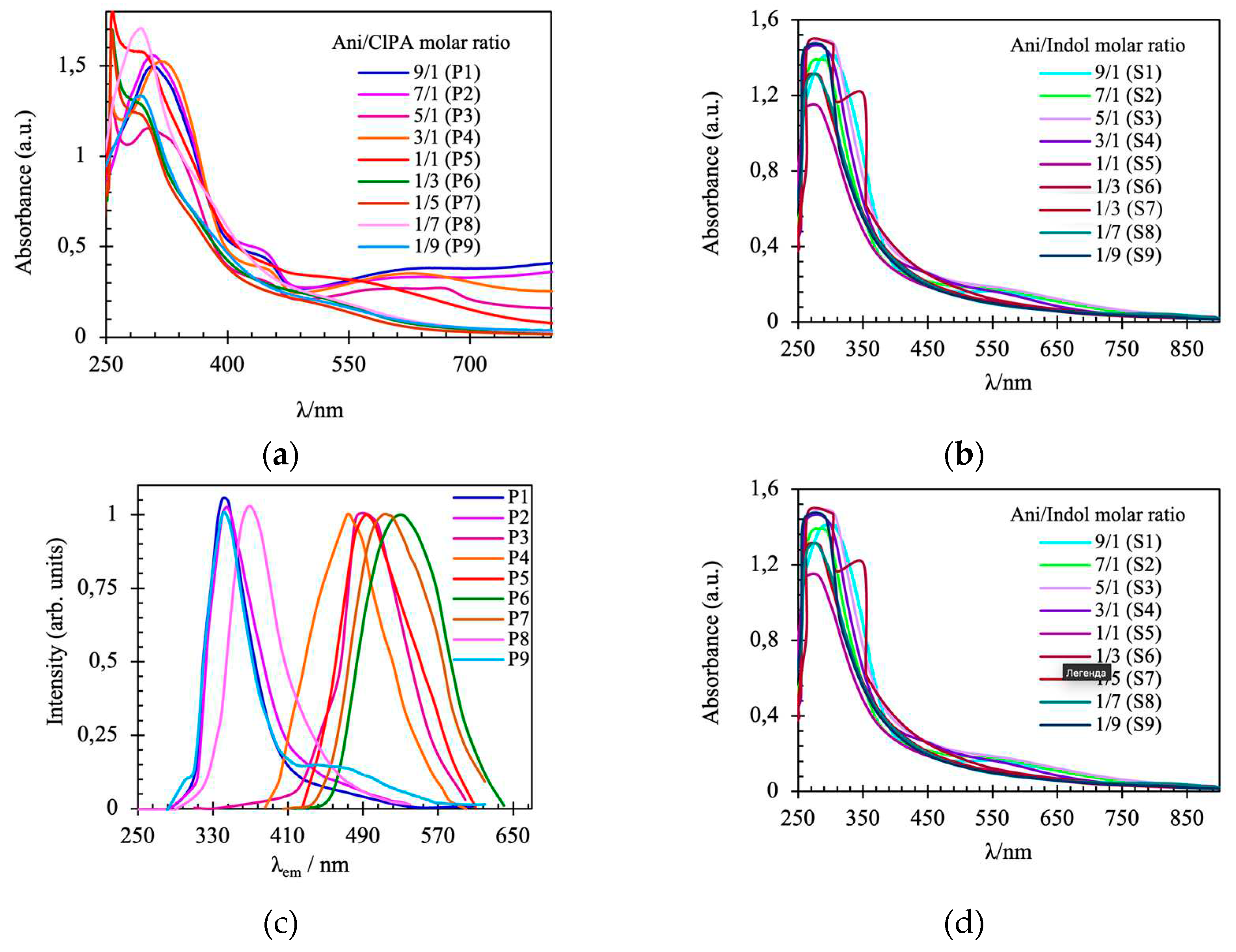

Figure 2a shows the absorbance spectra of different copolymers, whereas

Figure 2b shows the corresponding spectra of polymers after intramolecular cyclization. As it is observed in

Figure 2a, the spectra for copolymers P1-P4 resemble the spectra of PANI in the salt form of emeraldine [

20]: three bands are observed at ca. 308, 435 and 633 nm, respectively. Copolymers P5-P9 exhibit only two absorption bands at 289 and 534 nm. The spectra of copolymers P5-P9 undergo a hypsochromic shift as the content of 2-[2-chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl]aniline in the comonomer feed is gradually increased, indicating a substantial reduction in the level of conjugation along the copolymer chain with incorporation of the alkenyl substituent in the polymer chain. The hypsochromic shift is attributable to the –Cl substituent of the alkenyl substituent which could increase the torsional angle between the adjacent phenyl rings in the polymer backbone. The S1-S9 polymers after cyclization have one absorption maximum at ca. 287 nm (

Figure 2b). The data are in good agreement with the literature data [

21,

22].

Figure 2c,d shows the photoluminescence spectra of polymers P1-P9 and S1-S9. The copolymers with a high Ani content show emission centered at ca. 345 nm. However, as the ClPA content increases, the fluorescence spectra show a gradual red shift, and the copolymers have an emission band centered at ca. 508 nm (

Figure 2c). These results are consistent with the low content of quinone imine units in copolymers with high ClPA content. The fluorescent spectra in

Figure 2d show that the emission peaks of polymers after modification are located in two regions, which is probably due to the presence of two different excitons in the composition of the polymer chain. The samples with a high content of substituted monomer units manifest emission maxima, which can be attributed to the luminescence of the indole fragment at about 465 nm. In addition, it should be noted that a hypsochromic shift of fluorescence maxima is observed for the entire series of cyclization products.

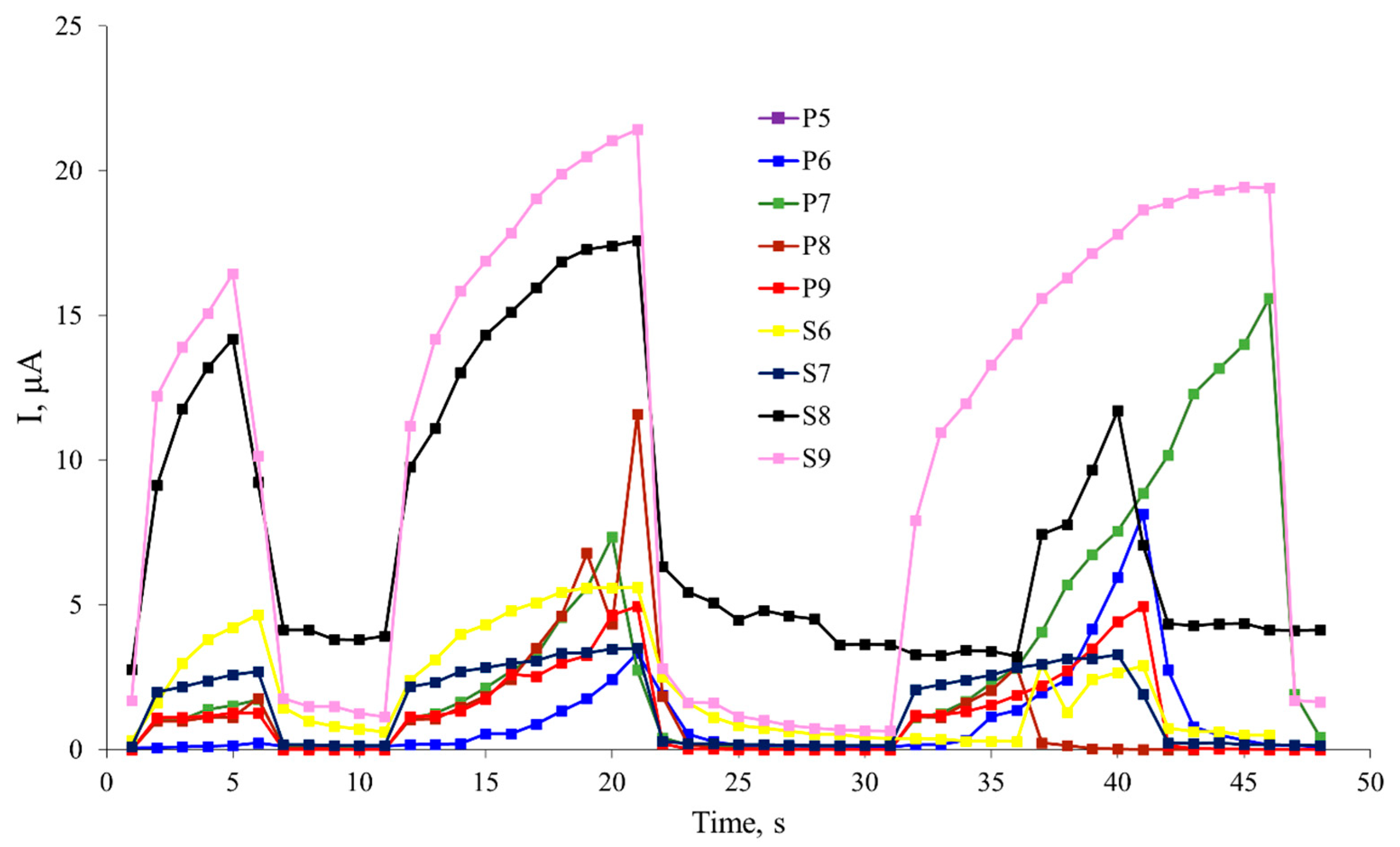

Absorbance spectra of copolymers revealed variations influenced by ClPA content, impacting the level of conjugation along the polymer chain. Photoluminescence spectra showcased shifts, signifying changes in the copolymer composition. Photoelectric properties were scrutinized for photoconductivity, highlighting S9's exceptional performance. Dark and photocurrent analyses underscored the photosensitivity of polyanilines.

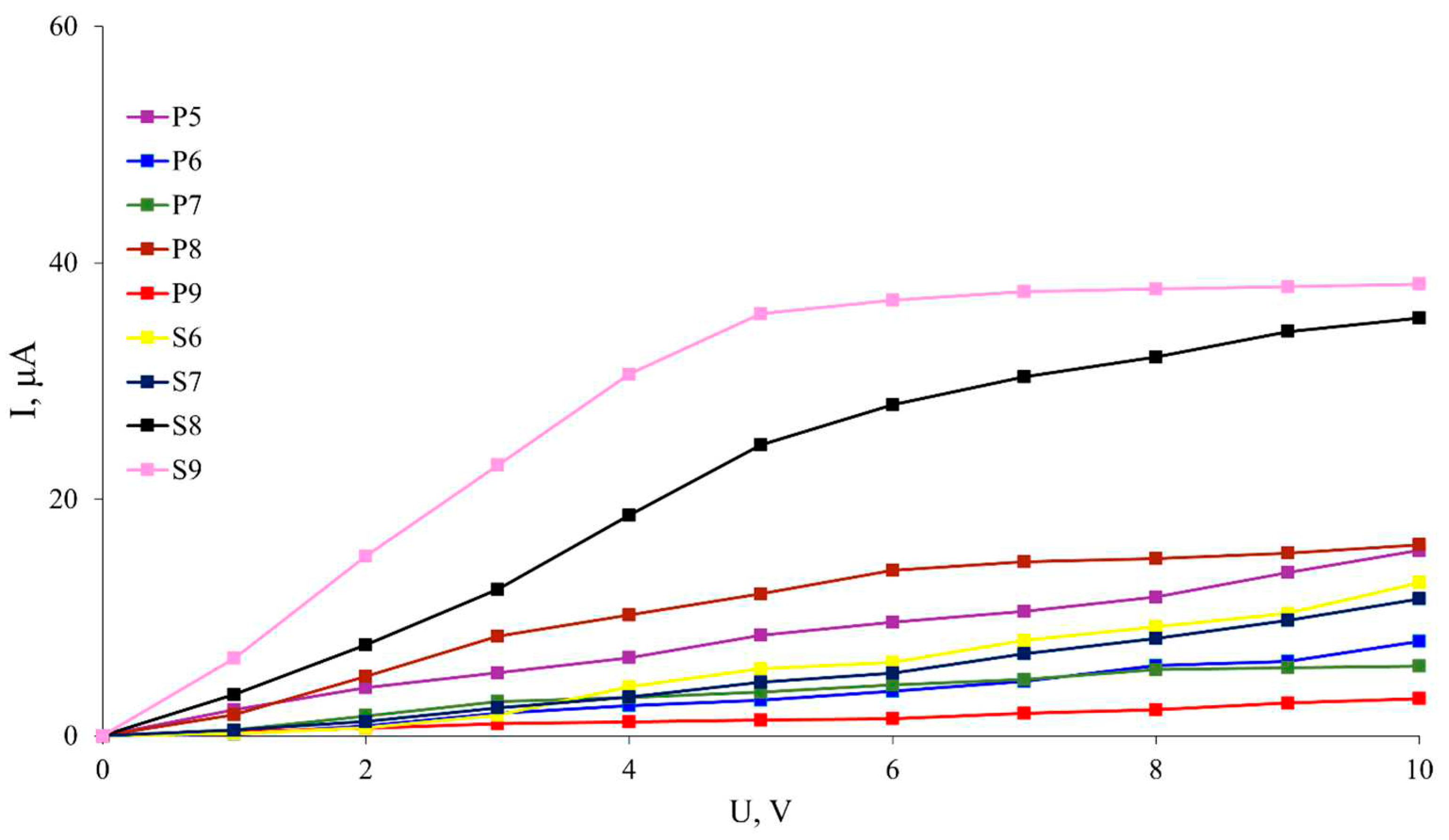

3. Photoelectric properties

Samples P5-P9 and S6-S9 were chosen for the investigation of the photoelectric properties, as the other polymers did not exhibit photoconductivity. The photoelectric properties of the polyanilines are studied in the context of their photosensitivity, which is determined by the dark current and photocurrent. Dark current, an intrinsic facet of materials, manifests as electric current coursing through a substance in the absence of external illumination. This complex phenomenon is shaped by multifaceted processes, ranging from thermal generation of charge carriers to diffusion, carrier tunneling, and recombination. The magnitude of dark current is intricately tied to an array of factors, including material composition and structure, temperature, electrical properties, and other nuanced parameters.

On the other hand, the photocurrent is the electric current generated in a material under the impact of external illumination. The photocurrent is caused by photoexcitation and photoelectron emission processes, where light photons interact with the material, inducing the emission of electrons from its surface. The photocurrent can be measured under various illumination conditions, such as continuous or pulsed illumination, and serves as a measure of the material's photosensitivity.

Delving deeper into the implications of studying these photoelectric properties, particularly dark current and photocurrent, unlocks valuable insights. These insights are pivotal for comprehending and fine-tuning the photosensitivity and electro-optical properties of polyanilines. This knowledge is indispensable in the ongoing quest to develop and optimize an array of photoelectronic devices, ranging from photodetectors and solar cells to various photoelectric elements.

The photoconductivity of polyanilines is attributed to their ability to generate and transport charge carriers upon interaction with light photons. The main mechanism of photoconductivity in polyanilines is associated with photoexcitation and photoelectron emission processes. When a polyaniline material is exposed to light, light photons interact with the polyaniline molecules, exciting electrons in the valence band to higher energy levels. These excited electrons can then be transferred from the valence band to the conduction band, thereby creating pairs of charge carriers, i.e., electrons and holes.

These dynamically generated charge carriers enjoy unhindered mobility within the material, inducing discernible alterations in its electrical properties, notably conductivity. Crucially, the photoconductivity of polyanilines emerges as a highly controllable attribute. Through strategic adjustments in composition, structure, doping, or other parameters of the polymer material, the photoelectric properties can be precisely tuned. This tunability opens up vistas for tailoring the photoconductivity of polyanilines to meet specific requisites and applications, such as in the realm of photodetectors, solar cells, and various other photoelectronic devices.

Figure 3 illustrates the photoconductivity of the polyaniline samples mentioned above. It is evident that sample S9 exhibits the highest degree of photoconductivity compared to the other samples, and a clear saturation boundary is observed at a voltage of 5V. Sample S8 also shows pronounced photoconductivity, although this polymer does not exhibit a "plateau" within the measured ranges, and the currents increase almost linearly with voltage. Interestingly, prior to synthesis of (P9), polymer S9 had the lowest photoconductivity among the measured samples. The P8-S8 transition also exhibits a distinct positive feature. It is known that the dark currents of similar polymers range within 1-2 nA [

23]. Thus, it can be concluded that under illumination with an irradiance of 3.5 W/cm

2, the current increases 35,000-fold or more for samples S8 and S9 and from 1,000-fold to 15,000-fold for the others.

The photosensitivity observed in polyanilines is intricately governed by their structural and electronic characteristics, constituting a complex interplay of molecular intricacies. As polymers, polyanilines manifest in diverse structural configurations, contingent upon parameters such as chain length, degree of polymerization, and the presence of functional groups or impurities.

In the context of photosensitivity, the structural attributes of polyanilines assume paramount significance. These features dictate the polymer's photonic interaction capabilities, influencing its aptitude for light energy absorption and the concomitant generation of photo-induced charge carriers. Specifically, structural motifs incorporating conjugated or aromatic groups have been identified as pivotal enhancers of polyaniline photosensitivity. These molecular architectures exhibit distinctive light interactions, eliciting a heightened response in terms of charge carrier generation.

Beyond structural considerations, electronic properties add another layer of influence to photosensitivity. Parameters including the energy level of the frontier band and the Fermi level intricately modulate the electronic landscape within polyanilines, thereby impacting their responsiveness to incident light. Photon interactions with polyanilines induce nuanced changes in the electronic structure, instigating the generation of photo-induced charge carriers and introducing a dynamic facet to the material's photosensitivity.

In summation, the photosensitivity of polyanilines emerges as an orchestrated interplay between their structural and electronic dimensions. This nuanced understanding not only augments our comprehension of the material's behavior but also presents avenues for deliberate manipulation of photosensitivity. Such manipulation holds promise for tailoring the material's performance in various applications, ranging from advanced photodetectors to solar cells and diverse photoelectronic devices.

Table 1 displays the photosensitivity of various conductive samples. It is evident that samples S9 and S8 exhibit the highest photosensitivity. The photosensitivity value P is determined as the ratio of the photocurrent to the dark current:

where I

ph represents the photocurrent, I

illum is the channel current under illumination, and I

dark is the dark drain current. The calculations took into account that the area of the device exposed to light did not exceed 0.12 cm

2.

The sensitivity value R is defined as the ratio of the generated photocurrent to the incident optical power (Popt). Therefore, the sensitivity R can be calculated as:

where Eopt represents the power density of the incident radiation; a represents the area available for the incident radiation. The sensitivity values are shown in

Table 2.

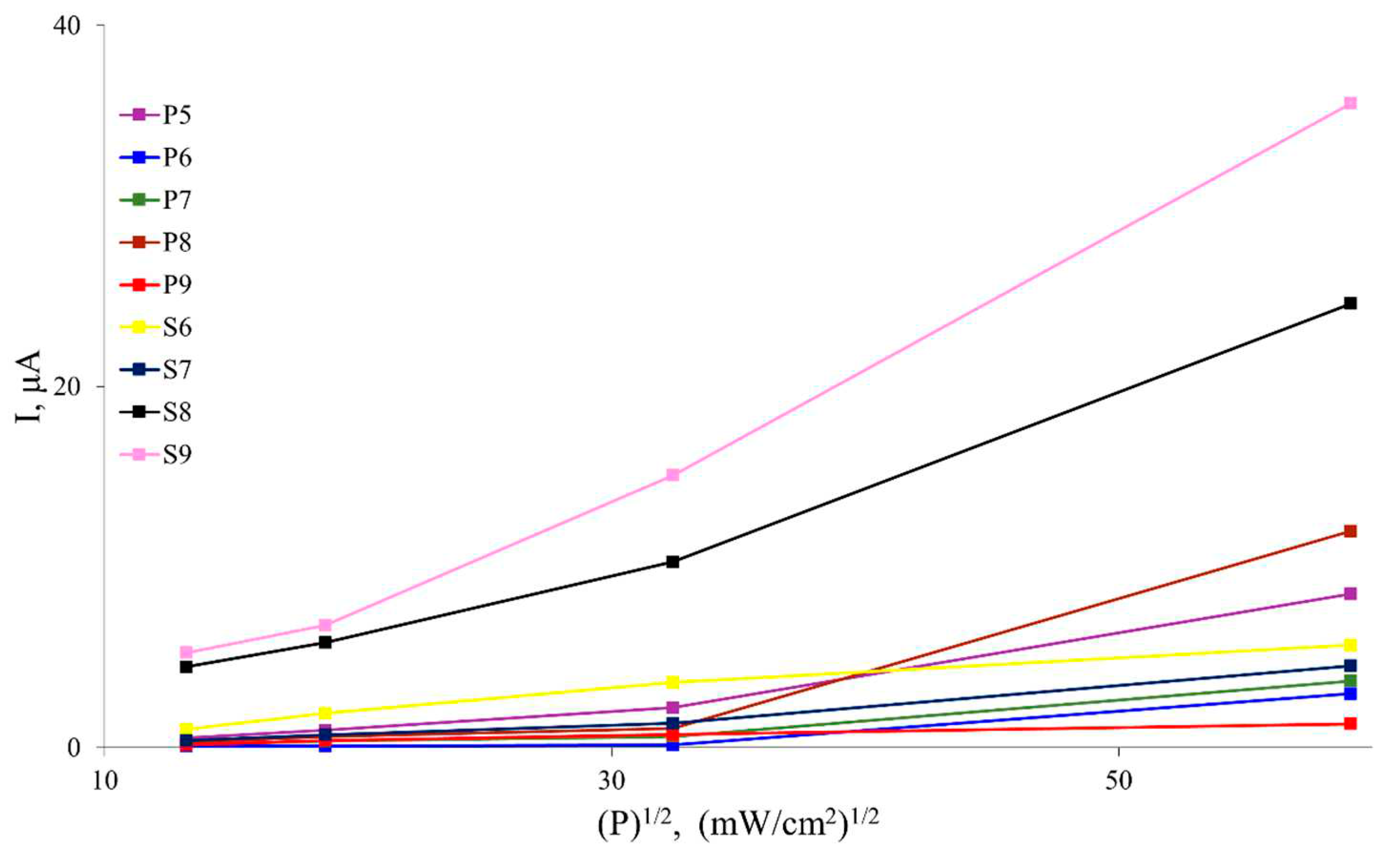

The quantum efficiency η was also calculated. The highest values of 0.037 and 0.046 were obtained for samples S8 and S9, respectively. The values for the other polymers range from 0.004 to 0.019. The quantum efficiency η was evaluated using the following formulas , , , , where n is the number of photoelectrons generated per unit time, N is the number of photons incident on the surface of the photodetector per unit time; I is the magnitude of the photocurrent; e is the charge of an electron; W is the energy of the incident radiation on the total area of the photodetector, s = 12 × 10-6 m2, per unit time; q = 35000 W/m2 is the radiation flux density; λ = 350 nm is the radiation wavelength.

Figure 2 shows the plots of the photocurrent as a function of the square root of power density of incident radiation for different samples. It can be observed that the photoconductivity decreases by a factor of 2-7, depending on the sample, as the distance from the light source increases from 10 to 30 mm. This behavior is consistent with interband quadratic recombination, where the steady-state carrier concentration generated by light, as well as the photoconductivity and photocurrent, have a square root dependence on the intensity of the light flux P [

24,

25]. Indeed, such a dependence has been experimentally confirmed in previous studies.

It was found that the photoresponse of the transistor accurately reflects the shape of the light pulses and that the rise and fall times of the photocurrent pulses do not exceed 1 second. Shorter rise and fall times are characteristic of structures obtained at high rotational speeds during centrifugation.

Figure 4 displays the plots of the photocurrent as a function of the square root of the power density of the incident radiation for films obtained at various centrifugation speeds. The voltage between the electrodes was 10 V. For example, the calculated quantum efficiency of samples obtained by centrifugation at a speed of 800 rpm is

ca. 10

-3, which is slightly higher than that of naphthalene [

26].

A kinetic characterization of the photoresponse of thin film structures based on polyaniline was conducted. The change in photoconductivity was measured when a series of rectangular light pulses with different durations (5, 10, and 5 seconds) were applied. The results of this study are presented in

Figure 5.

The kinetics of photoresponse in polyanilines investigates the processes occurring in the polymer upon exposure to light and the rate of response to photoenergy. The photoresponse of polyanilines is typically manifested as a change in the material's conductivity under light irradiation. The kinetics of polyaniline photoresponse is determined by multiple factors, such as light intensity, duration of illumination, composition and structure of the polymer material, presence of doping, and other parameters.

It can be observed from the plot that S9 exhibits almost no saturation and charge retention, indicating a high rate of response to irradiation. Similar behavior is observed for S8, although this sample demonstrates the ability to retain a current in the range of 4-5 μA in the absence of illumination.

Studying the kinetics of polyaniline photoresponse makes it possible to determine the rate of photoresponse, the time to reach maximum conductivity, energy barriers, and other parameters that influence the photoelectric properties of the polymer material. This information can be crucial for the development and optimization of photoelectronic devices based on polyanilines such as photodetectors, solar cells, optical sensors, and other applications where controlling the kinetics of photoresponse plays a significant role in device functionality and efficiency.

4. Discussion

The fluorescence spectra of the polymer group exhibit maximum values in two distinct spectral regions: 340-360 nm and 490-520 nm. It's well-established that alterations in copolymer composition lead to shifts in fluorescence maxima. The investigation of the photoluminescent properties of S1–S9 copolymers in DMSO solutions unveiled significant changes compared to non-cyclized polymer samples. Specifically, samples rich in substituted monomers demonstrated emission maxima around 465 nm, associated with the presence of an indole moiety.

Turning attention to the photovoltaic properties, the study delved into thin films of polyanilines, scrutinizing their behavior concerning fabrication conditions and surface morphology. Notably, the highest quantum efficiency values, reaching 0.037 and 0.046, were observed in polymers S8 and S9, respectively. Beyond impressive quantum efficiency, these samples exhibited remarkable photoconductivity, surpassing dark conductivity by an astounding factor of approximately 35,000. This underscores the profound impact of fabrication conditions and surface morphology on the electrical characteristics of thin films.

In summary, the alterations observed in fluorescence spectra among copolymers point towards changes in the fluorophore, a phenomenon directly linked to shifts in composition. The investigation into the photovoltaic properties highlights the crucial role of fabrication conditions and surface morphology in determining the performance of thin films. The standout performers, S8 and S9, not only demonstrated the highest quantum efficiency but also showcased exceptional photoconductivity. This compelling evidence strongly indicates that the synthesis of the "S" polymers has substantially elevated the electrical properties of the materials, marking a significant stride in advancing the capabilities of these polymers for potential applications in optoelectronics.

5. Conclusions

Thin-film photoresistors, a pivotal component in electronic devices, were skillfully engineered using polyanilines, and a comprehensive evaluation of their characteristics ensued, encompassing quantum efficiency and carrier mobility. A notable advantage lies in the exceptional solubility of polyanilines, rendering them highly amenable to the modern printing technologies employed in organic electronics. This characteristic ensures compatibility in the production of electronic components, offering a practical edge in the rapidly evolving field.

An added merit of the thin-film structures under investigation is their resilience in ambient air. This stands in stark contrast to many experimental devices based on alternative organic compounds, which typically necessitate operation within an inert gas or dry nitrogen chamber. This ambient air compatibility expands the practical utility of thin-film photoresistors based on polyanilines, making them more versatile and applicable in real-world conditions. The fundamental mechanism underlying the photoconductivity of polyanilines is rooted in the presence of charged states within the polymer matrix. Illumination triggers the facile transfer of these charged states, instigating the generation of an electric current. This photogenerated current is a consequence of the delicate equilibrium between donor and acceptor sites within the polymer structure, orchestrating the localization of charge carriers in specific regions of the polymer matrix.

Crucially, this study underscores the potential for enhancing the photoconductivity of polyanilines. The incorporation of additional molecular groups into the polymer matrix emerges as a promising strategy. These added groups contribute to the expansion of the conduction band and facilitate improved charge transfer dynamics. This insight opens up avenues for future exploration and optimization of polyaniline-based electronic components in diverse applications.

In summary, thin-film photoresistors based on polyanilines not only exhibit promising characteristics but also boast practical advantages, such as ambient air operability and compatibility with modern printing technologies. The delicate interplay of donor and acceptor sites in the polymer structure governing photoconductivity provides a nuanced understanding. The discussion on enhancing photoconductivity through the strategic introduction of molecular groups into the polymer matrix adds a forward-looking dimension, paving the way for continued advancements and applications in electronic devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Salikhov; methodology, L.Latypova; investigation, L.Latypova and T.Yumalin, T.Salikhov; writing—original draft preparation, L.Latypova and T.Yumalin; writing—review and editing, R.Salikhov, I.Sharafullin and A.Mustafin. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This publication is based on support by the State assignment for the implementation of scientific research by laboratories (Order MN-8/1356 of 09/20/2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maity, N.; Kuila, A.; Das, S.; Mandal, D.; Shit, A.; Nandi, A.K. Optoelectronic and photovoltaic properties of graphene quantum dot–polyaniline nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3(41), 20736–20748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Anum, R.; Siddique, S.; Shakir, H.F.; Rehan, Z.A. Polyaniline-based nanocomposites for electromagnetic interference shielding applications: A review. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 36(4), 1717–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnaiah, T.; Dhananjaya, P.G.; Sainagesh, C.V.; Reddy, S.; Kumaraswamy, S.; Surendranatha, N.C. A review: Electrical and gas sensing properties of polyaniline/ferrite nanocomposites. Sens. Rev. 2022, 42(1), 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrithesh, M., Aravind, S., Jayalekshmi, S., & Jayasree, R.S. Polyaniline doped with orthophosphoric acid—A material with prospects for optoelectronic applications. J. alloy compd. 2008 458(1-2), 532-535. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Khosla, R., Deva, D., Shrimali, H., & Sharma, S.K. Fluorine-chlorine co-doped TiO2/CSA doped polyaniline based high performance inorganic/organic hybrid heterostructure for UV photodetection applications. Sensor actuat. a-phys. 2017, 261, 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Mojtabavi, E.A., & Nasirian, S. A self-powered UV photodetector based on polyaniline/titania nanocomposite with long-term stability. Opt. mater. 2019, 94, 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Antonel, P.S., Völker, E., & Molina, F.V. Photophysics of polyaniline: sequence-length distribution dependence of photoluminescence quenching as studied by fluorescence measurements and Monte Carlo simulations. Polymer. 2012, 53(13), 2619-2627. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yan, G., Ding, H., & Shan, Y. Fabrication and photovoltaic properties of self-assembled sulfonated polyaniline/TiO2 nanocomposite ultrathin films. Mater. Chem. phys. 2007, 102(2-3), 249-254. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, K., Smyth, M. R., Killard, A. J., & Morrin, A. Printing polyaniline for sensor applications. Chem. pap. 2013, 67, 771–780. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, B., Xu, Q., Hou, Y., Seyedin, S., Qin, S., ... & Chen, J. Development of graphene oxide/polyaniline inks for high performance flexible microsupercapacitors via extrusion printing. Adv. Func. Mater. 2018, 28(21), 1706592. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Sun, R., Jia, P., Ma, M., & Song, Y. Fabricating flexible conductive structures by printing techniques and printable conductive materials. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2022, 10(25), 9441-9464. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Zhou, J., Xue, H., Shen, L., Zang, H., & Chen, W. Polyaniline/TiO2 solar cells. Synthetic met. 2006, 156(9-10), 721-723. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, G., Munjal, G., Bhaskarwar, A. N., & Chaudhary, A. Dye-sensitized solar cells with polyaniline: A review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 135, 109087. [CrossRef]

- Savitha, P., Swapna Rao, P., Sathyanarayana, D.N. Highly conductive new aniline copolymers: poly (aniline-co-aminoacetophenone). Polym. Int. 2005, 54 (9) 1243-1250. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., Xu, J. Progress in conjugated polyindoles: synthesis, polymerization mechanisms, properties, and applications. Polym Rev. 2017, 57 (2) 248-275. [CrossRef]

- Latypova, L.R., Andriianova, A.N., Salikhov, S.M., Mullagaliev, I.N., Salikhov, R.B., Abdrakhmanov I.B., Mustafin A.G., Synthesis and physicochemical properties of poly [2-(2-chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl) aniline] obtained with various dopants, Polym. Int. 2020, 69 (9) 804-812. [CrossRef]

- Mustafin, A.G., Latypova, L.R., Andriianova, A.N., Salikhov, S.M., Sattarova, A.F., Mullagaliev, I.N., Abdrakhmanov, I.B., Synthesis and Physicochemical Properties of Poly (2-ethyl-3-methylindole), Macromolecules. 2020, 53 (18) 8050-8059. [CrossRef]

- Latypova, L.R, Andriianova, A.N., Usmanova, G.S, Salikhov, R.B., Mustafin, A.G., Influence of copolymer composition on the properties of soluble poly(aniline-co-2-[2-chloro-1-methylbut-2-en-1-yl]aniline)s, Polym. 2023, Int. 72 (4) 440-450. [CrossRef]

- Usmanova, U.S.; Latypova, L.R.; Andriianova, A.N.; Salikhov, Sh.M.; Mustafin, A.G. Synthesis and Investigation of Polymers Containing Aniline and Indole Fragments. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G., Zhou, H.J., Huang, M.R. Synthesis and properties of a functional copolymer from N-ethylaniline and aniline by an emulsion polymerization. Polym. 2005, V. 46 (5), 1523-1533. [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Luo, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, L. Synthesis of indole-based functional polymers with well-defined structures via a catalyst-free C–N coupling reaction. RSC Adv. 2014, 4(58), 30630–30637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Han, Y., He, J., & Zhang, Y. Synthesis of fluorescent poly (silyl indole) s via borane-catalyzed C–H silylation of indoles. Polym. chem-UK, 2023, 14(4), 492-499. [CrossRef]

- Salikhov, R.B., Mustafin, A.G., Mullagaliev, I.N., Salikhov, T.R., Andriianova, A.N., Latypova, L.R., & Sharafullin, I.F. Photoconductivity of Thin Films Obtained from a New Type of Polyindole. Materials, 2022, 15(1), 228. [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.K.; Krishna, J.J.; Agnihotri, A.K.; Singh, C.P.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, A. Temperature and intensity dependence of photoconductivity in a-Se70Te26Zn4: Determination of defect centres. Chalcogenide Lett. 2009, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Magnanelli, T.J., Engmann, S., Wahlstrand, J.K., Stephenson, J.C., Richter, L.J., & Heilweil, E. J. (2020). Polarization dependence of charge conduction in conjugated polymer films investigated with time-resolved terahertz spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124(13), 6993-7006. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, E.L. Photosensitive polymer semiconductors. Semiconductors+, 1115; 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).