1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors. Despite decades of research, the fundamental biological mechanisms underlying autism remain elusive. While genetic factors contribute substantially to autism risk, environmental and immunological factors increasingly appear to play critical roles.

A growing body of evidence indicates that offspring of parents with autoimmune diseases show elevated autism prevalence. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that family history of autoimmune disease is associated with a 28-50% higher autism prevalence. Importantly, specific autoimmune conditions mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) show particularly robust associations with offspring autism.

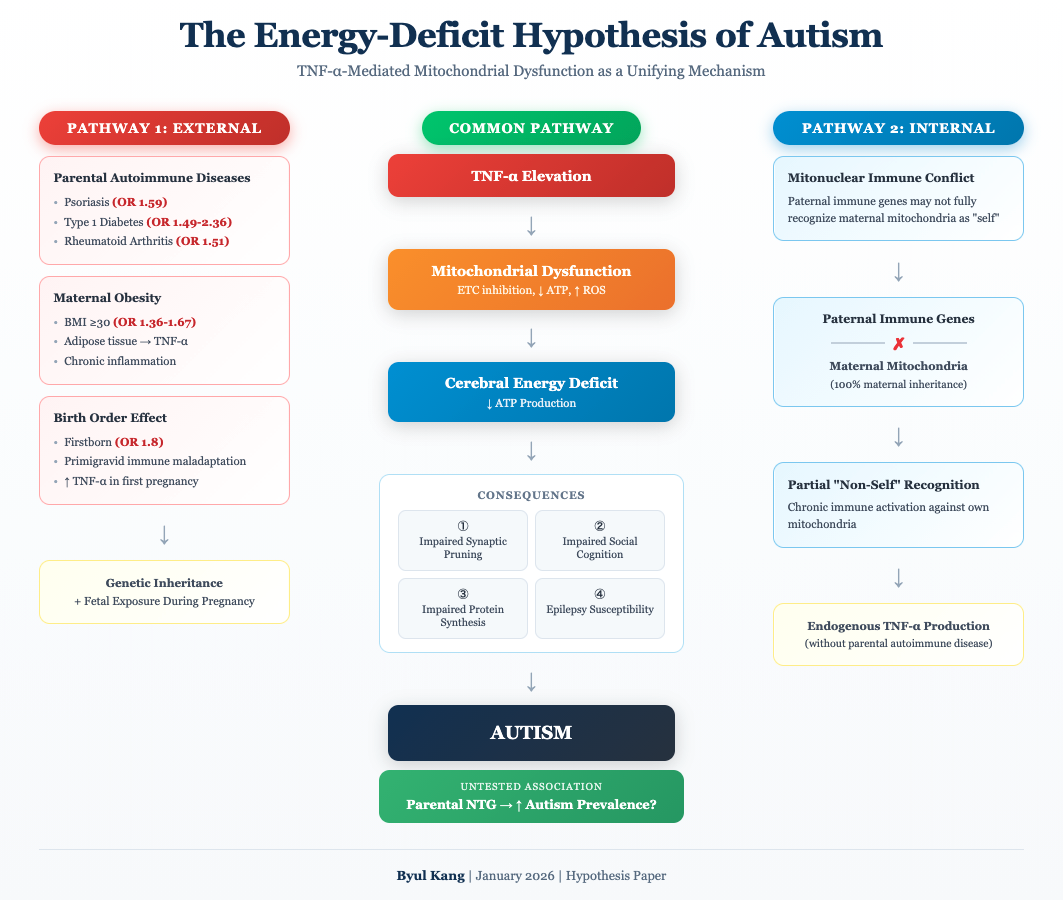

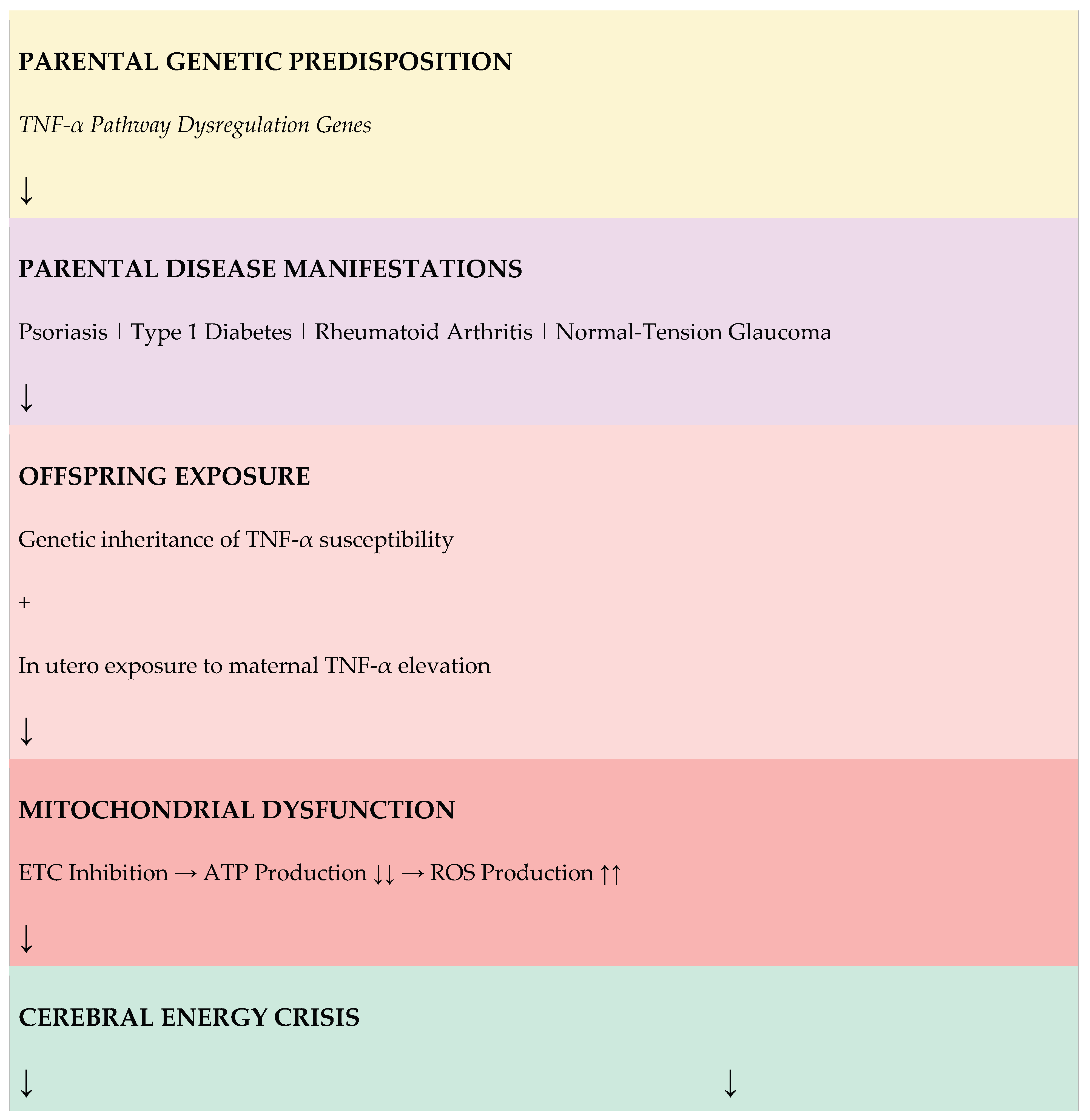

In this hypothesis paper, I propose that autism is fundamentally an immune-metabolic disorder characterized by TNF-α-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. I argue that the resulting cerebral energy deficiency impairs two critical processes: synaptic pruning during neurodevelopment and real-time social cognitive processing. This framework explains core autism symptoms from a unified energetic perspective and generates testable predictions.

2. Epidemiological Evidence: Parental Autoimmune Diseases and Autism Risk

2.1. Large-Scale Studies

Multiple large-scale epidemiological studies have established associations between parental autoimmune diseases and offspring autism risk.

Table 1 summarizes key findings from major studies.

2.2. The TNF-α Common Denominator

A critical observation is that all parental diseases strongly associated with offspring autism risk share a common pathogenic mechanism: dysregulation of TNF-α signaling. TNF-α is a master pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays central roles in:

Psoriasis: TNF-α drives keratinocyte proliferation and inflammatory cascade; anti-TNF biologics are first-line therapy

Type 1 Diabetes: TNF-α directly induces β-cell apoptosis and promotes autoimmune destruction of pancreatic islets

Rheumatoid Arthritis: TNF-α orchestrates synovial inflammation and joint destruction; anti-TNF therapy revolutionized treatment

Normal-Tension Glaucoma: TNF-α mediates retinal ganglion cell death independent of intraocular pressure elevation

3. Sources of TNF-α Exposure

Multiple pathways can lead to elevated TNF-α exposure during critical periods of neurodevelopment. This section examines four distinct sources: parental autoimmune diseases, maternal obesity, maternal immune maladaptation during first pregnancies, and endogenous mitonuclear immune conflict.

3.1. Parental Autoimmune Diseases

As detailed in

Section 2, offspring of parents with autoimmune diseases including psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis show elevated autism prevalence. These conditions share TNF-α pathway dysregulation as a common pathogenic mechanism. Children may be exposed to elevated TNF-α through genetic inheritance of inflammatory gene variants and/or direct fetal exposure to maternal TNF-α during pregnancy.

3.2. Maternal Obesity: An Additional Source of Prenatal TNF-α Exposure

Beyond parental autoimmune diseases, maternal obesity represents another condition associated with elevated offspring autism prevalence. Multiple large-scale epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated that children of obese mothers show higher autism rates.

3.2.1. Epidemiological Evidence

Meta-analyses reveal that maternal obesity (BMI ≥30) is associated with a 36-67% increased risk of offspring autism (OR 1.36-1.67). Importantly, the risk increases in a dose-dependent manner with maternal BMI, suggesting a biological gradient rather than confounding.

3.2.2. Obesity as a Chronic Inflammatory State

Obesity is fundamentally a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. Adipose tissue is not merely an energy storage organ but an active endocrine tissue that produces pro-inflammatory cytokines:

Adipose tissue is a major source of TNF-α production

Circulating TNF-α levels are 2-3 fold higher in obese individuals

Other inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, leptin) are also elevated

Inflammation correlates with degree of adiposity

3.2.3. Mechanism of Fetal Exposure

During pregnancy, maternal obesity creates multiple pathways for fetal TNF-α exposure:

Transplacental passage: Maternal TNF-α can cross the placenta and directly affect fetal brain development

Placental inflammation: The placenta itself becomes inflamed in obese pregnancies, producing additional local cytokines

Metabolic stress: Maternal hyperglycemia and insulin resistance further compromise fetal mitochondrial function

Oxidative stress: Obesity-associated oxidative stress damages both maternal and fetal mitochondria

3.2.4. Convergence with the Energy-Deficit Model

Maternal obesity thus represents another route to the same pathogenic endpoint: TNF-α-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in the developing fetal brain. Whether TNF-α elevation originates from parental autoimmune disease, maternal obesity, or both, the downstream consequences—impaired synaptic pruning, compromised social cognition, and protein synthesis deficits—remain the same. This convergence explains why maternal obesity and parental autoimmune conditions show similar effect sizes for autism risk and may have additive effects when co-occurring.

3.3. The Birth Order Effect: Maternal Immune Maladaptation

Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate that firstborn children have significantly elevated autism risk compared to later-born siblings. This "firstborn effect" has been dismissed as reproductive stoppage (parents not having more children after an autistic child), but this explanation conflates correlation with causation.

3.3.1. Epidemiological Evidence for the Firstborn Effect

Table 5.

Birth Order and Autism Risk: Evidence Summary.

Table 5.

Birth Order and Autism Risk: Evidence Summary.

| Finding |

Effect Size |

Reference |

| Firstborn autism risk (Utah) |

OR 1.8 |

Bilder et al. 2009 |

| Firstborn autism risk (Sweden, n=1.5M) |

~20% higher |

Meta-analysis |

| Short interpregnancy interval (<12 mo) |

OR 3.39 |

Cheslack-Postava 2011 |

| Preeclampsia in nulliparous women |

Significantly higher |

Robillard et al. |

| Partner change resets preeclampsia risk |

Returns to primigravid |

Dekker et al. |

3.3.2. Primigravid Immune Maladaptation Mechanism

The maternal immune system must achieve tolerance to semi-allogeneic fetal antigens. This tolerance develops progressively across the first pregnancy as paternal antigen-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) expand. During the first pregnancy, the maternal immune system encounters paternal antigens for the first time, resulting in a Th1-dominant response with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α. Subsequent pregnancies (with the same partner) benefit from immunological memory, with rapid Treg expansion providing enhanced tolerance.

3.3.3. Preeclampsia as Parallel Paradigm

Preeclampsia—characterized by placental inflammation and TNF-α elevation—has been called "the disease of primigravidae" since 1902. Nulliparous women have significantly higher preeclampsia risk than multiparous women, and critically, this protective effect is lost when women change partners. Prior abortion with the same partner reduces preeclampsia risk by half (OR 0.54), but abortion with a different partner confers no protection. These findings demonstrate that paternal antigen-specific tolerance develops during first pregnancy and provides lasting protection—precisely the mechanism I propose underlies the autism birth order effect.

3.4. Mitonuclear Immune Conflict: An Endogenous Source of TNF-α

While the preceding sections describe how TNF-α-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction leads to autism, an important question remains: what about cases where parents have no autoimmune disease? I propose that mitonuclear immune conflict may represent an endogenous source of TNF-α that activates the same pathogenic pathway.

3.4.1. The Gap in the TNF-α Hypothesis

The TNF-α energy deficit hypothesis explains autism risk in offspring of parents with autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis. However, autism also occurs in families with no history of autoimmune disease. Additionally, studies show that a substantial proportion of autistic individuals exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction biomarkers without carrying classical mitochondrial disease mutations.

This raises a critical question: if TNF-α-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction is central to autism pathophysiology, what is the source of TNF-α in cases without parental autoimmune disease?

3.4.2. The Unique Inheritance Pattern of Mitochondria

Mitochondria possess a unique inheritance pattern. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is inherited exclusively from the mother—paternal mitochondria are actively eliminated from the fertilized egg. Every mitochondrion in an individual's body carries only maternal genetic information.

In contrast, the nuclear genome—including genes governing immune function and self/non-self recognition—is inherited from both parents. This creates an asymmetry: the immune system is shaped by both parental genomes, but the mitochondria it must tolerate are exclusively maternal.

3.4.3. The Conflict Hypothesis: Paternal Immune Genes vs. Maternal Mitochondria

I hypothesize that in some individuals, paternally inherited immune genes may fail to fully recognize maternal mitochondria as "self." This could result in:

Immune misrecognition: The paternal contribution to immune recognition machinery (HLA genes, innate immune pathways) may be calibrated to recognize mitochondrial signatures that differ from those inherited from the mother.

Chronic immune attack: The immune system may mount persistent inflammatory responses against the individual's own mitochondria, treating them as partially foreign.

Endogenous TNF-α production: This chronic immune activation would result in sustained TNF-α release—activating the same pathogenic cascade described in previous sections, even without external TNF-α exposure from parental autoimmune disease.

3.4.4. Two Pathways to the Same Outcome

The mitonuclear immune conflict hypothesis does not replace the parental autoimmune disease hypothesis—it complements it by providing a second pathway to TNF-α-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction:

Table 7.

Two Pathways to TNF-α-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction.

Table 7.

Two Pathways to TNF-α-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction.

| |

Pathway 1: External |

Pathway 2: Internal |

| Source of TNF-α |

Parental autoimmune disease |

Mitonuclear immune conflict |

| Mechanism |

Genetic inheritance + fetal exposure during pregnancy |

Paternal immune attack on maternal mitochondria |

| Parental disease required? |

Yes |

No |

| Final common pathway |

TNF-α elevation → Mitochondrial dysfunction → Energy deficit → Autism |

This framework explains why:

Parental autoimmune disease is associated with elevated autism prevalence (Pathway 1)

Autism also occurs without parental autoimmune disease (Pathway 2)

Only a subset of children with autoimmune parents develop autism (variable mitonuclear compatibility may be protective or additive)

3.4.5. Testable Predictions

The mitonuclear immune conflict hypothesis generates testable predictions:

Anti-mitochondrial antibodies or mitochondria-targeted immune markers may be elevated in autistic individuals without parental autoimmune history

Inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α may be elevated even in autism cases without parental autoimmune disease

Specific HLA haplotype combinations from parents may show associations with autism risk

4. TNF-α and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Mechanistic Link

4.1. Direct Effects of TNF-α on Mitochondrial Function

TNF-α exerts profound inhibitory effects on mitochondrial function through multiple mechanisms.

Table 2 summarizes the key pathways by which TNF-α impairs cellular energy production.

4.2. Rapid Neurotoxicity of TNF-α

Critically, TNF-α-induced mitochondrial dysfunction occurs rapidly in neurons. Studies using pathophysiologically relevant concentrations demonstrate:

Reduction in mitochondrial basal respiration within 1.5 hours of TNF-α exposure

Decreased ATP production preceding neuronal cell death

Effects mediated specifically through TNF-R1 receptor signaling

Cascade involving caspase-8 activation, membrane potential collapse, and cytochrome c release

5. Consequences of Cerebral Energy Deficit

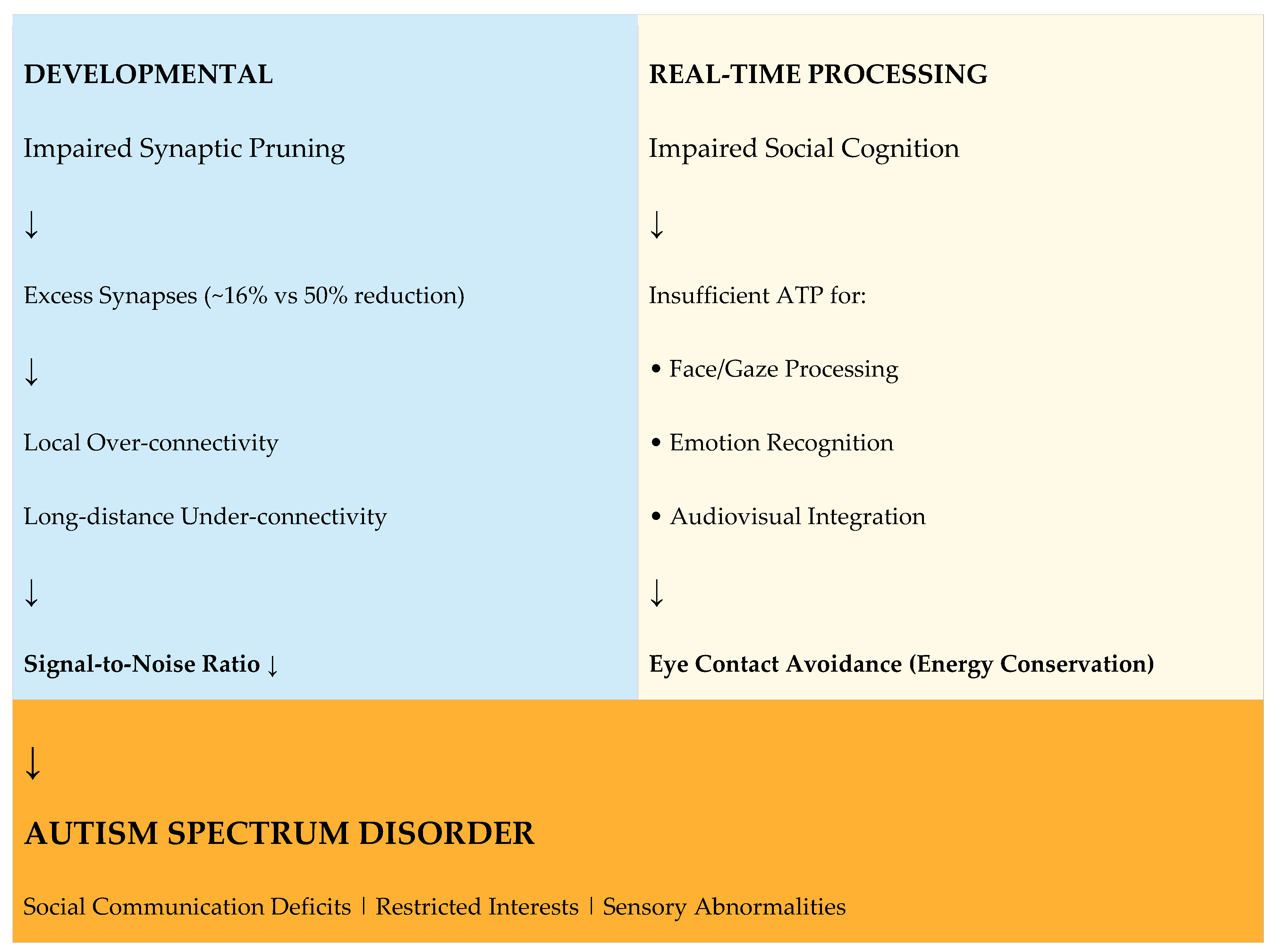

I propose that chronic TNF-α elevation, regardless of its source, leads to persistent mitochondrial dysfunction and cerebral energy deficiency. This energy deficit manifests in four critical domains that explain core autism symptoms and associated features.

5.1. Impaired Synaptic Pruning

The Energy Cost of Synaptic Pruning: The developing brain undergoes massive synaptic pruning, eliminating approximately 50% of synapses from infancy to adolescence. This process is extraordinarily energy-intensive because:

Microglia actively phagocytose synapses, requiring substantial ATP

The infant brain consumes 40% of total body energy—far exceeding adult proportions

Complement cascade activation and autophagy pathways require ATP

Evidence of Pruning Deficits in Autism: Postmortem studies reveal striking differences in synaptic density between autistic and neurotypical brains:

Table 3.

Synaptic Pruning in Neurotypical vs Autistic Brains.

Table 3.

Synaptic Pruning in Neurotypical vs Autistic Brains.

| Parameter |

Neurotypical |

Autism |

| Synaptic density reduction (childhood→adolescence) |

~50% |

~16% |

| Dendritic spine density |

Normal |

Elevated |

| mTOR pathway activity |

Normal |

Hyperactive |

| Autophagy function |

Normal |

Impaired |

Consequences of Excess Synapses: The failure to prune synapses results in:

Local over-connectivity: Excess short-range connections creating "neural noise"

Long-distance under-connectivity: Insufficient resources for developing major "highway" connections between brain regions

Reduced signal-to-noise ratio: Difficulty filtering relevant from irrelevant information

Sensory overload: Heightened sensitivity due to failure to attenuate sensory inputs

5.2. Impaired Social Cognition and Gaze Avoidance

The Energy Demands of Social Processing: Social cognition—including face recognition, gaze processing, and emotion interpretation—is among the most computationally and energetically demanding brain functions. It requires simultaneous activation of:

Fusiform Face Area (FFA): Face identity processing

Superior Temporal Sulcus (STS): Gaze direction and biological motion

Amygdala: Emotional salience and threat detection

Prefrontal Cortex: Social context integration and decision-making

Eye Contact as Energy Conservation: I propose that gaze avoidance in autism represents an adaptive energy conservation strategy. Direct evidence supports this interpretation:

Table 4.

Self-Reported Experiences of Eye Contact in Autism.

Table 4.

Self-Reported Experiences of Eye Contact in Autism.

| Experience Category |

Representative Quote |

| Energy Exertion |

"Eye contact feels like I'm using up a lot of energy. Maximum 2-6 seconds." |

| Audiovisual Integration Failure |

"I cannot listen to someone while making eye contact at the same time." |

| Cognitive Trade-off |

"When I focus on eye contact, I can't process what's being said." |

| Recovery Requirement |

"The longer I maintain eye contact, the more recovery time I need afterward." |

Neural Evidence: Functional neuroimaging studies demonstrate that in autism, eye contact triggers amygdala hyperactivation, suggesting heightened metabolic demand. Gaze avoidance thus serves to reduce this hyperarousal and conserve limited neural energy for other cognitive tasks.

5.3. Epilepsy Comorbidity as Supporting Evidence

The high comorbidity between autism and epilepsy provides additional support for the TNF-α-mediated energy deficit hypothesis. Approximately 20-30% of autistic individuals experience epileptic seizures, compared to 1-2% in the general population. In autism with intellectual disability, prevalence rises to 40%.

TNF-α and Seizure Susceptibility: TNF-α directly increases neuronal excitability through multiple mechanisms:

Increases AMPA receptor surface expression, enhancing excitatory transmission

Promotes GABA receptor internalization, reducing inhibitory tone

Creates excitation/inhibition imbalance that lowers seizure threshold

Energy Deficit and Seizure Vulnerability: Mitochondrial dysfunction further predisposes to seizures through:

Impaired Na+/K+-ATPase function due to ATP deficit, destabilizing membrane potential

Compromised GABAergic inhibition, which is highly energy-dependent

Notably, primary mitochondrial diseases (e.g., MELAS, Leigh syndrome) frequently present with epilepsy

The autism-epilepsy comorbidity thus reflects converging consequences of TNF-α-mediated neuroinflammation and mitochondrial energy deficit: neuroinflammation increases excitability while energy deficit impairs the inhibitory circuits required to prevent seizures.

5.4. Impaired Protein Synthesis: The Critical Energy Bottleneck

Protein synthesis is the most energy-intensive cellular process, consuming approximately 25-30% of total cellular ATP. Each amino acid incorporation requires ~4 ATP equivalents, making the synthesis of large synaptic proteins extraordinarily energy-demanding. During neurodevelopment, when neurons must produce vast quantities of synaptic proteins, any ATP deficit creates a critical bottleneck.

5.4.1. Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis as Rate-Limiting Step

The electron transport chain requires both nuclear- and mitochondrial-genome-encoded subunits. Critically, mitochondrial protein synthesis by the 55S ribosome is the rate-limiting step in ETC synthesis. Of the 230 genes in the Mitochondrial Central Dogma, 59 are associated with neurodevelopmental delay, representing a 2-fold enrichment (p < 8.95E-9). This age of onset coincides with the brain's peak glutamatergic synapse density, emphasizing the developmental linkage between energy consumption and brain maturation.

Table 6.

Critical Synaptic Proteins Vulnerable to Energy Deficit.

Table 6.

Critical Synaptic Proteins Vulnerable to Energy Deficit.

| Protein |

Function |

ASD Association |

Energy Cost |

| SHANK3 |

Synaptic scaffold |

0.5-2% of ASD cases |

Large (1,731 aa) |

| NRXN/NLGN |

Synaptic adhesion |

Multiple variants |

Transmembrane |

| PSD-95 |

Postsynaptic density |

Altered in ASD |

Scaffold assembly |

| BDNF |

Neuron survival |

Reduced in ASD |

Activity-dependent |

| FMRP |

mRNA regulation |

Fragile X syndrome |

Translation control |

5.4.2. The SHANK3-Mitochondria Connection

Phelan-McDermid syndrome, caused by SHANK3 deletion, illustrates the intimate connection between synaptic proteins and mitochondrial function. The 22q13.3 region containing SHANK3 also harbors six mitochondrial genes: SCO2 (cytochrome c oxidase assembly), NDUFA6 (Complex I), TYMP, TRMU (mtDNA maintenance), CPT1B (fatty acid metabolism), and ACO2 (TCA cycle). Deletions affecting SHANK3 may simultaneously disrupt mitochondrial function, creating a dual vulnerability.

6. Integrated Pathophysiological Model

Figure 1 presents the unified model linking parental TNF-α-mediated diseases to offspring autism through mitochondrial dysfunction and energy deficiency.

Figure 1 Legend:

The model illustrates how parental TNF-α pathway dysregulation leads to offspring autism through two converging pathways: developmental (impaired synaptic pruning) and real-time (impaired social cognition). Both pathways result from ATP deficiency secondary to mitochondrial dysfunction. ETC = Electron Transport Chain; ROS = Reactive Oxygen Species.

7. Novel Prediction: Normal-Tension Glaucoma and Autism

A critical test of this hypothesis involves normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). NTG is a neurodegenerative condition affecting retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) that shares key pathophysiological features with both the TNF-α-mediated autoimmune diseases associated with autism and with autism itself.

7.1. NTG as a TNF-α-Mediated Condition

Evidence supporting TNF-α involvement in NTG:

Elevated TNF-α levels in aqueous humor and serum of NTG patients

TNF-α directly induces RGC apoptosis via TNF-R1 signaling

Anti-TNF therapy shows protective effects in animal models

NTG frequently co-occurs with systemic inflammatory conditions (e.g., psoriasis)

Disease progression occurs despite normal intraocular pressure, implicating IOP-independent mechanisms

7.2. The Untested Association

If the TNF-α energy deficit hypothesis is correct, children of parents with NTG may show elevated autism prevalence compared to the general population.

To my knowledge, no published study has examined the association between parental NTG and offspring autism. This represents a critical gap in the literature that warrants investigation.

Table 7.

TNF-α-Mediated Conditions and Autism Association Studies.

Table 7.

TNF-α-Mediated Conditions and Autism Association Studies.

| Parental Condition |

TNF-α Role |

Autism Association Studied? |

| Psoriasis |

Central |

Yes (OR 1.59) |

| Type 1 Diabetes |

Central |

Yes (OR 1.49-2.36) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis |

Central |

Yes (OR 1.51) |

| Normal-Tension Glaucoma |

Central |

NO STUDIES EXIST |

8. Therapeutic Implications

The energy-deficit hypothesis suggests several therapeutic approaches:

8.1. Anti-TNF-α Interventions

Existing anti-TNF biologics (etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, adalimumab) have proven efficacy in TNF-α-mediated diseases. In type 1 diabetes, golimumab preserved β-cell function in a phase 2 trial (NEJM 2020). Similar approaches might be considered for autism prevention in high-risk pregnancies, though significant safety and ethical considerations would need to be addressed.

8.2. Mitochondrial Support

Interventions supporting mitochondrial function may provide benefit:

Coenzyme Q10: Essential electron carrier in ETC

L-Carnitine: Facilitates fatty acid transport into mitochondria

NAD+ Precursors (NR, NMN): Support ETC function and cellular energy production

B Vitamins: Cofactors for mitochondrial enzymes

8.3. Early Identification

Screening for parental TNF-α-mediated diseases (psoriasis, T1D, RA, NTG) could identify pregnancies at elevated autism risk, enabling earlier monitoring and potentially earlier intervention.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations: This hypothesis paper synthesizes existing evidence but does not present new experimental data. The proposed mechanisms, while supported by converging lines of evidence, require direct experimental validation.

Future Directions: Key studies needed include: (1) Epidemiological investigation of parental NTG and offspring autism risk; (2) Longitudinal studies of mitochondrial function in infants at high autism risk; (3) Clinical trials of mitochondrial support interventions; (4) Mechanistic studies of TNF-α effects on synaptic pruning in animal models.

10. Conclusion

I propose that autism spectrum disorder can be understood as an immune-metabolic disorder characterized by TNF-α-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction leading to cerebral energy deficiency. This energy deficit impairs synaptic pruning during development and compromises real-time social cognitive processing, explaining core autism symptoms from a unified mechanistic perspective.

The hypothesis generates a novel, testable prediction: that parents with normal-tension glaucoma—a TNF-α-mediated neurodegenerative condition not previously linked to offspring autism—will show elevated prevalence of autistic children. Confirmation of this prediction would provide strong support for the broader hypothesis.

If validated, this framework has important implications for autism prevention and treatment, suggesting that anti-inflammatory and mitochondrial support interventions may have therapeutic potential, particularly when administered early in neurodevelopment.

References

- Wu, S; Ding, Y; Wu, F; et al. Family history of autoimmune diseases is associated with an increased risk of autism in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015, 55, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, AH; Wang, X; Martinez, MP; et al. Maternal Type 1 Diabetes and Risk of Autism in Offspring. JAMA 2018, 320, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, M; et al. Maternal type 1 diabetes, pre-term birth and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Int J Epidemiol. 2023, 52, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keil, A; Daniels, JL; Forssen, U; et al. Parental autoimmune diseases associated with autism spectrum disorders in offspring. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atladóttir, HO; Pedersen, MG; Thorsen, P; et al. Association of family history of autoimmune diseases and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G; Gudsnuk, K; Kuo, SH; et al. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron 2014, 83, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, DA; Roberts, N; Lin, C; Birmingham, E. How do adults and teens with self-declared Autism Spectrum Disorder experience eye contact? PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0188446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, KM; Nacewicz, BM; Johnstone, T; et al. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nat Neurosci. 2005, 8, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G; Berk, M. The many roads to mitochondrial dysfunction in neuroimmune and neuropsychiatric disorders. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quattrin, T; Haller, MJ; Steck, AK; et al. Golimumab and Beta-Cell Function in Youth with New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 2007–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y; et al. The role of the immune system in autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 284–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol, DA; Frye, RE. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2012, 17, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, T; et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates oligodendrocyte death and delayed retinal ganglion cell loss in a mouse model of glaucoma. J Neurosci. 2006, 26, 12633–12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W; et al. Rapid mitochondrial dysfunction mediates TNF-alpha-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2015, 132, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood, P; et al. Immunological cytokine profiling identifies TNF-α as a key molecule dysregulated in autistic children. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 809–816. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).