1. Introduction

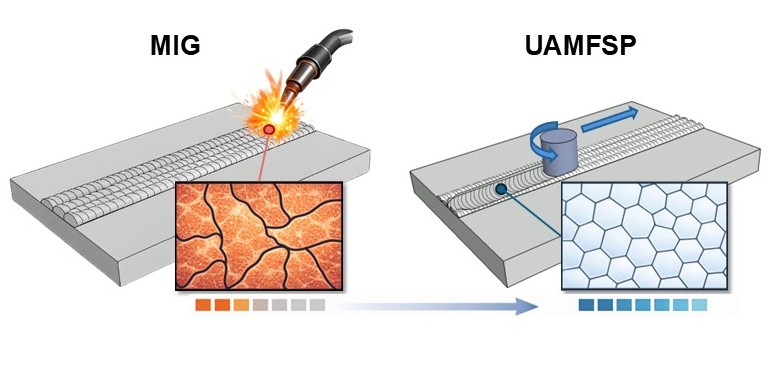

Direct Energy Deposition Additive Manufacturing (DEDAM) processes have emerged as methods for the fabrication of near-net-shape metal parts and enable the production of complicated structures [

1,

2]. These processes are based on Directed Energy Deposition (DED), which uses a focused energy source for melting the feedstock, with common options such as laser beams, electron beams, and electric arc plasma. The material in the DED process can be supplied as either a powder or a wire. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) is a DED-based process that has gained remarkable attention because of its cost-effectiveness, high deposition rate, and design flexibility. This technique is based on conventional welding processes, such as Metal Inert Gas (MIG), Tungsten Inert Gas (TIG), and Plasma Arc Welding (PAW) [

3]. WAAM enables the production of large-scale aluminum (Al) based structures with minimal post-processing requirements, which makes it appealing for use in aerospace, automotive, and tooling applications [

4,

5]. Recently, it has been considered a sustainable alternative for subtractive fabrication methods due to its material efficiency, scalability, and potential for use in digital design processes [

6,

7].

Although WAAM has many advantages, it has some limitations. The parts fabricated by the WAAM process have dendritic microstructures [

8,

9], porosity, residual stresses, anisotropy, and coarse grains resulting from repetitive thermal cycles in its layer-by-layer deposition process [

3,

10]. These features compromise the mechanical performance by reducing the toughness, fatigue resistance, and isotropy of the fabricated part. Therefore, grain refinement is critical for improving the strength and durability of WAAM-fabricated parts. This could be done by reducing dislocation motion and enhancing Hall–Petch strengthening [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, macrostructural distortions and residual stresses that result from excessive heat buildup during multilayer deposition can negatively affect the dimensional accuracy and fatigue performance of the components [

14,

15]. Recent studies have highlighted that effectively controlling the heat and microstructure is vital for improving the consistency of the WAAM-built aluminum components [

16,

17].

To address the limitations of WAAM-built parts, among the Severe Plastic Deformation (SPD) techniques, the Friction Stir Processing (FSP) is widely recognized for its ability to refine the microstructures, eliminating casting defects, and improving isotropy [

13,

18,

19]. Derived from Friction Stir Welding (FSW), FSP has been shown to refine dendritic grains [

8,

9] into fine equiaxed structures, remarkably improving the strength and toughness of Al-based alloys [

13,

18,

19]. The FSP process causes intense plastic deformation and dynamic recrystallization (DRX). This disrupts the columnar dendritic structures in the WAAM-fabricated parts, encourages the formation of high-angle grain boundaries, and helps mix solutes evenly. Recent studies have shown that using in situ interlayer FSP during WAAM can create a uniform equiaxed structure and decrease the grain size remarkably [

16].

The interlayer FSP eliminates porosity and breaks eutectic phases, producing refined α-Al grains and increasing the tensile strength compared to that of WAAM-only builds [

20,

21]. For instance, Wei et al. [

21] demonstrated that applying an interlayer FSP to the WAAM 2219 aluminum alloy improved the yield strength from 118 MPa to 143 MPa and the fatigue strength from 97 MPa to 139 MPa owing to the breakup and dissolution of coarse eutectic phases. Similarly, in Al–Cu–Mg systems, the interlayer FSP reduced porosity, refined grains to sub-5 µm, and produced nearly isotropic hardness and tensile responses [

22].

Beyond FSP, new hybrid approaches, such as ultrasonic impact treatment, interlayer hot rolling, and cryogenic deformation, are being explored to simultaneously manage heat accumulation and mechanical anisotropy at the same time [

23,

24]. For example, interlayer ultrasonic impact increases the dislocation density and strengthens the grain boundaries while reducing the buildup of tensile residual stress [

23]. Similarly, interlayer rolling and in situ electric pulse treatments decrease the residual stress and distortion without affecting geometric accuracy [

25,

26]. These deformation-assisted methods show that combining thermal and mechanical energy inputs can more effectively control grain shape and texture changes than optimizing the process parameters [

27,

28].

Recently, a patented unified additive deformation manufacturing process (UAMFSP) was proposed. This approach directly integrates WAAM with FSP to introduce a single hybrid additive–deformation process [

29]. In this method, first, the WAAM stage provides a rapid material deposition, and then the FSP stage acts as SPD on the deposited material [

30] to dynamically recrystallize and refine the grains during or after deposition of each layer. This method has the potential for stabilizing the thermal cycles, suppressing the abnormal grain growth, improving equiaxedness of the grains, and enhancing the mechanical properties of the fabricated part compared with the WAAM-only builds [

5]. Recent research studies have supported this introduced concept. For instance, Yuan et al. [

31] reported that the hybrid WAAM–interlayer FSP in Al–Cu alloys can form a periodic bimodal grain structure (BGS) that simultaneously enhances the strength and ductility of the fabricated part through combined discontinuous and continuous dynamic recrystallization (CDRX). Also, Guo et al. [

32] presented that multiple stirring passes in the WAAM–FSP manufactured 2319 Al alloy part promoted secondary recrystallization and balanced strength–ductility relationships by reducing the coarsening of the remelted grain. These findings indicate that the controlled thermomechanical coupling via the iterative deposition and stirring can stabilize the heat-affected zone and also tailor the recrystallized grain size. Furthermore, in another study, Shan et al. [

33] revealed that the addition of reinforcement particles during the FSP stage can result in dual strengthening and ductility in Al–Zn–Mg–Cu systems, thereby demonstrating the versatility of the hybrid fabrication approach.

Recent hybrid systems that combine the WAAM and FSP processes on a single platform have enabled improvement on controlling the heat flow and strain distribution. This integration reduces interlayer gradients of temperature and can promote a more uniform microstructure, leading to improved mechanical performance that approaches isotropy [

17,

27]. Studies on Al–Mg and Al–Si aluminum-based alloys have revealed the remarkable enhancements in thermal uniformity and refinement in microstructure [

26,

28]. The integration of the UAMFSP aligns with broader trends in hybrid manufacturing that merge additive, subtractive, and deformation processes for achieving improved structural integrity and dimensional precision [

34,

35,

36].

The hybrid additive–subtractive systems have advantages like on-machine finishing, relief of the residual stress, and repair of defects in a single production cycle. This can reduce the production lead time and can improve repeatability [

7,

37]. These hybrid methods represent a paradigm shift in manufacturing, transforming WAAM from a standalone deposition process to a multifunctional platform that is capable for delivering both microstructural and geometrical excellence.

In addition, optimizing the process sequences between the FSP and heat treatment has been shown to further improve the balance between strength and ductility. For example, Zhou et al. [

38] showed that the FSP followed by solution and aging of the WAAM-fabricated Al–Cu alloys can result in tensile strengths higher than 425 MPa, whereas reversing the sequence can lead to an abnormal grain growth and loss of ductility. The findings of this research emphasized that controlling the thermomechanical and thermal histories of unified systems is critical for achieving high performance.

This present study investigates the process–microstructure–property relationships of aluminum 4043 walls fabricated using WAAM-only and the patented UAMFSP processes. The analysis focuses on (i) the role of thermal accumulation during the deposition of the layers, (ii) refinement of the microstructural and statistical analysis of the grain morphology, and (iii) validation of property improvements through hardness testing [

11,

12]. This work introduces the UAMFSP as a robust pathway for overcoming the metallurgical and mechanical limitations of WAAM. Furthermore, it provides an experimental evidence and a conceptual framework for extending additive deformation strategies to thicker walls, alternative alloy systems, and the application-specific architectures in the future studies. The outcomes of this research are expected to contribute to a broader understanding of hybrid process coupling and the evolution of the next-generation manufacturing technologies that enable the production of high-strength, minimal-defect, and dimensionally precise Al-based components [

6,

22,

26,

39].

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the processing strategy exerts a decisive influence on the thermal, microstructural, and mechanical characteristics of aluminum-alloy walls fabricated using the MIG and the hybrid UAMFSP processes.

The microstructural results confirmed that the MIG-deposited walls developed coarse, dendritic, and anisotropic grains (mean area of about 313.6 µm²), which was a direct consequence of uncontrolled solidification and thermal gradients. However, the walls fabricated using the UAMFSP process exhibited a refined, equiaxed, and isotropic structure that had a mean grain area of 10.9 µm², attributed to the SPD and DRX during the FSP stage of the UAMFSP process. This transition from the melting–solidification process to solid-state recrystallization significantly improved the grain uniformity and eliminated the anisotropy typical of WAAM-deposited aluminum structures.

The thermal analysis revealed that the MIG wall experienced a progressive heat accumulation for each successive layer, where the maximum temperatures of about 900 to 1000 °C were recorded during the process, and the transient peaks occasionally exceeded the limit of the highest measurable temperature of the IR camera, which was approximately 1300 °C. In contrast, the UAMFSP process effectively redistributed the frictional heat through plastic stirring, which maintains the peak temperatures below 400 °C and ensures more uniform and stable temperature fields along the build line.

Mechanical characterization further supported the previous observations. The UAMFSP walls achieved a hardness of 75.8 ± 7.7 HV, which represents an approximately 45.8% increase compared to the MIG walls, which showed a hardness of 52.0 ± 1.3 HV. This improvement is governed by the Hall–Petch relationship, in which a refined grain size and isotropic microstructure can increase the resistance to dislocation motion and improve the overall mechanical performance. These results reveal that the UAMFSP process can provide a strong and reproducible pathway for overcoming the inherent thermal and microstructural limitations of the conventional WAAM, resulting in fine-grained, isotropic, and mechanically stable aluminum walls.

Overall, the results of this study demonstrate that the hybrid UAMFSP process is a robust approach for overcoming the inherent thermal and microstructural limitations of the WAAM process, which enables the fabrication of the high-performance aluminum components. For a broader industrial adoption, the future research should extend this approach into thicker multilayer builds, explore additional aluminum alloys and hybrid material systems, and investigate about their performance under the service-relevant loading conditions, such as tensile, fatigue, and the thermal cycling. Such a research study is essential for establishing the scalability, the durability, and the qualification potential of the UAMFSP as a reliable manufacturing route for the high-performance structural components used in aerospace, marine, and automotive applications.

Figure 1.

(a) General experimental setup showing the HAAS VF3 CNC machining center retrofitted with a spool gun for MIG deposition and equipped with an FSP tool for hybrid UAMFSP operation; (b) fabricated MIG and UAMFSP walls; (c) fabrication sequence of the walls using the UAMFSP process: (i) deposition sequence of MIG layers and (ii) execution sequence illustrating the integration of FSP.

Figure 1.

(a) General experimental setup showing the HAAS VF3 CNC machining center retrofitted with a spool gun for MIG deposition and equipped with an FSP tool for hybrid UAMFSP operation; (b) fabricated MIG and UAMFSP walls; (c) fabrication sequence of the walls using the UAMFSP process: (i) deposition sequence of MIG layers and (ii) execution sequence illustrating the integration of FSP.

Figure 2.

(a) The locations on the specimen section in the walls, (b) a representative MIPAR-based microstructural analysis, and (c) IR thermal imaging camera location in the experimental setup.

Figure 2.

(a) The locations on the specimen section in the walls, (b) a representative MIPAR-based microstructural analysis, and (c) IR thermal imaging camera location in the experimental setup.

Figure 3.

Representative optical micrographs of the MIG-deposited and the UAMFSP-processed 4043 aluminum alloy walls, illustrating the evolution of grain morphology with build height. Sequential layers (L1, L2, and L3) denote the first, second, and third layers, respectively. The images of the UAMFSP fabricated sample highlight the influence of FSP on grain refinement and uniformity of the microstructure. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Representative optical micrographs of the MIG-deposited and the UAMFSP-processed 4043 aluminum alloy walls, illustrating the evolution of grain morphology with build height. Sequential layers (L1, L2, and L3) denote the first, second, and third layers, respectively. The images of the UAMFSP fabricated sample highlight the influence of FSP on grain refinement and uniformity of the microstructure. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 4.

The probability density distributions of the grain area, grain perimeter, grain equivalent diameter, and grain roundness for the MIG and the UAMFSP walls.

Figure 4.

The probability density distributions of the grain area, grain perimeter, grain equivalent diameter, and grain roundness for the MIG and the UAMFSP walls.

Figure 5.

The comparative probability density curves of the grain area, grain perimeter, grain equivalent diameter, and grain roundness for the MIG and the UAMFSP walls.

Figure 5.

The comparative probability density curves of the grain area, grain perimeter, grain equivalent diameter, and grain roundness for the MIG and the UAMFSP walls.

Figure 6.

The temperature contour maps (T(x,y), °C) obtained, utilizing the IR thermography, for the MIG and the UAMFSP walls across Layers 1 to 3, corresponding to L1 (60 s), L2 (50 s), and L3 (30 s). The temperature data were captured utilizing an FLIR T300 IR camera and processed in °C, with an emissivity of 0.95 on the aluminum surface. The color scale represents the distribution of the spatial temperature. Scale bar = 5 µm.

Figure 6.

The temperature contour maps (T(x,y), °C) obtained, utilizing the IR thermography, for the MIG and the UAMFSP walls across Layers 1 to 3, corresponding to L1 (60 s), L2 (50 s), and L3 (30 s). The temperature data were captured utilizing an FLIR T300 IR camera and processed in °C, with an emissivity of 0.95 on the aluminum surface. The color scale represents the distribution of the spatial temperature. Scale bar = 5 µm.

Figure 7.

Temporal variation of the maximum temperature (°C) throughout the entire deposition and processing sequence for Layers 1–3, along with comparative results between the MIG and UAMFSP walls across the corresponding layers. Temperature data were captured using a FLIR T300 IR camera and processed in °C, with an emissivity of 0.95 for the aluminum surface.

Figure 7.

Temporal variation of the maximum temperature (°C) throughout the entire deposition and processing sequence for Layers 1–3, along with comparative results between the MIG and UAMFSP walls across the corresponding layers. Temperature data were captured using a FLIR T300 IR camera and processed in °C, with an emissivity of 0.95 for the aluminum surface.

Figure 8.

The comparison of the maximum temperatures (mean ± SD) measured at Layers 1–3 for the MIG and UAMFSP walls. The UAMFSP process exhibited significantly lower temperature peaks across all layers (****p < 0.0001).

Figure 8.

The comparison of the maximum temperatures (mean ± SD) measured at Layers 1–3 for the MIG and UAMFSP walls. The UAMFSP process exhibited significantly lower temperature peaks across all layers (****p < 0.0001).

Figure 9.

The Vickers hardness (HV0.2) measurement results of the MIG and the UAMFSP fabricated samples. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The double asterisk (**) indicates a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0027).

Figure 9.

The Vickers hardness (HV0.2) measurement results of the MIG and the UAMFSP fabricated samples. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The double asterisk (**) indicates a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0027).

Figure 10.

Mechanism of grain refinement in UAMFSP via CDRX. The rotating FSP tool refined the MIG-deposited layer (bottom-right inset: dendritic grains) into fine equiaxed grains (top-left inset).

Figure 10.

Mechanism of grain refinement in UAMFSP via CDRX. The rotating FSP tool refined the MIG-deposited layer (bottom-right inset: dendritic grains) into fine equiaxed grains (top-left inset).

Figure 11.

The schematic illustration of the dislocation-mediated strengthening in the MIG and the UAMFSP walls. In the MIG condition, coarse, irregular grains permit long dislocation mean free paths (red arrows), enabling easy glide and a low hardness. In the UAMFSP condition, the SPD during FSP produced fine equiaxed grains, with a high boundary density, inducing dislocation pile-ups (blue arrows) at the grain boundaries and therefore significantly increasing the strength via Hall–Petch strengthening,.

Figure 11.

The schematic illustration of the dislocation-mediated strengthening in the MIG and the UAMFSP walls. In the MIG condition, coarse, irregular grains permit long dislocation mean free paths (red arrows), enabling easy glide and a low hardness. In the UAMFSP condition, the SPD during FSP produced fine equiaxed grains, with a high boundary density, inducing dislocation pile-ups (blue arrows) at the grain boundaries and therefore significantly increasing the strength via Hall–Petch strengthening,.

Table 1.

Nominal chemical compositions of the substrate (AA6061 aluminum alloy) and the filler (ER4043 aluminum wire) in wt.%.

Table 1.

Nominal chemical compositions of the substrate (AA6061 aluminum alloy) and the filler (ER4043 aluminum wire) in wt.%.

| Element |

Mg |

Fe |

Mn |

Cr |

Si |

Cu |

Zn |

Ti |

Al |

| Substrate |

0.8-1.2 |

≤0.70 |

≤0.15 |

0.04-0.35 |

0.40-0.80 |

0.1-0.4 |

≤0.25 |

≤0.15 |

Bal. |

| Filler (ER4043) |

≤0.05 |

≤0.8 |

≤0.05 |

- |

4.5-6.0 |

≤0.3 |

≤0.1 |

≤0.2 |

Bal. |

Table 2.

MIG parameters used for the fabrication of the two walls.

Table 2.

MIG parameters used for the fabrication of the two walls.

| Voltage (U) |

Current (I) |

Welding speed (v) (mm/min) |

Wire stick-out (mm) |

Argon flow rate (CHF) |

| 18 |

120 |

330 |

9 |

27 |

Table 3.

FSP parameters used in the fabrication of the UAMFSP wall.

Table 3.

FSP parameters used in the fabrication of the UAMFSP wall.

| Layer |

Tool rotational speed (vs) (RPM) |

Tool travel speed (v) (mm/min) |

Plunge depth (mm) |

| 1 |

600 |

50 |

0.2 |

| 2&3 |

1200 |

50 |

0.2 |

Table 4.

Grain size and morphology statistics of MIG and UAMFSP walls.

Table 4.

Grain size and morphology statistics of MIG and UAMFSP walls.

| Wall |

Ā (µm²) |

à (µm²) |

σA |

P̄ (µm) |

P̃ |

σP |

D̄ |

D̃ |

σD |

R̄ |

R̃ |

σR |

| MIG |

313.6 |

219.8 |

335.2 |

73.4 |

68 |

49.6 |

17.2 |

16.7 |

10.2 |

0.71 |

0.61 |

0.38 |

| UAMFSP |

10.9 |

6.4 |

13.1 |

14 |

12.1 |

9.5 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

1.9 |

0.62 |

0.57 |

0.29 |

Table 5.

The average of maximum temperatures (°C) at Layers 1–3 for the MIG and UAMFSP walls.

Table 5.

The average of maximum temperatures (°C) at Layers 1–3 for the MIG and UAMFSP walls.

| Process |

L1 |

L2 |

L3 |

| MIG |

897.63 |

869.42 |

998.15 |

| UAMFSP |

324.45 |

386.21 |

277.23 |