Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retrieval of the Target Sequences and Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA)

2.2. Prediction of Protein Boundaries

2.3. Epitope Prediction

2.3.1. CD8+ Epitope Prediction (ELA I)

2.3.2. CD4+ Epitope Prediction (ELA-II)

2.3.3. IFN-γ inducing MHC class II binding peptides

2.3.4. Linear B-Cell Epitope Prediction

2.4. Criteria for Selection of Immunogenic Sequences

2.5. Vaccinal Construct Structure Prediction

2.6. Vaccinal Candidate Cellular Immunogenicity Assessment Via Molecular Docking

3. Results

3.1. In Silico Design and Validation Workflow

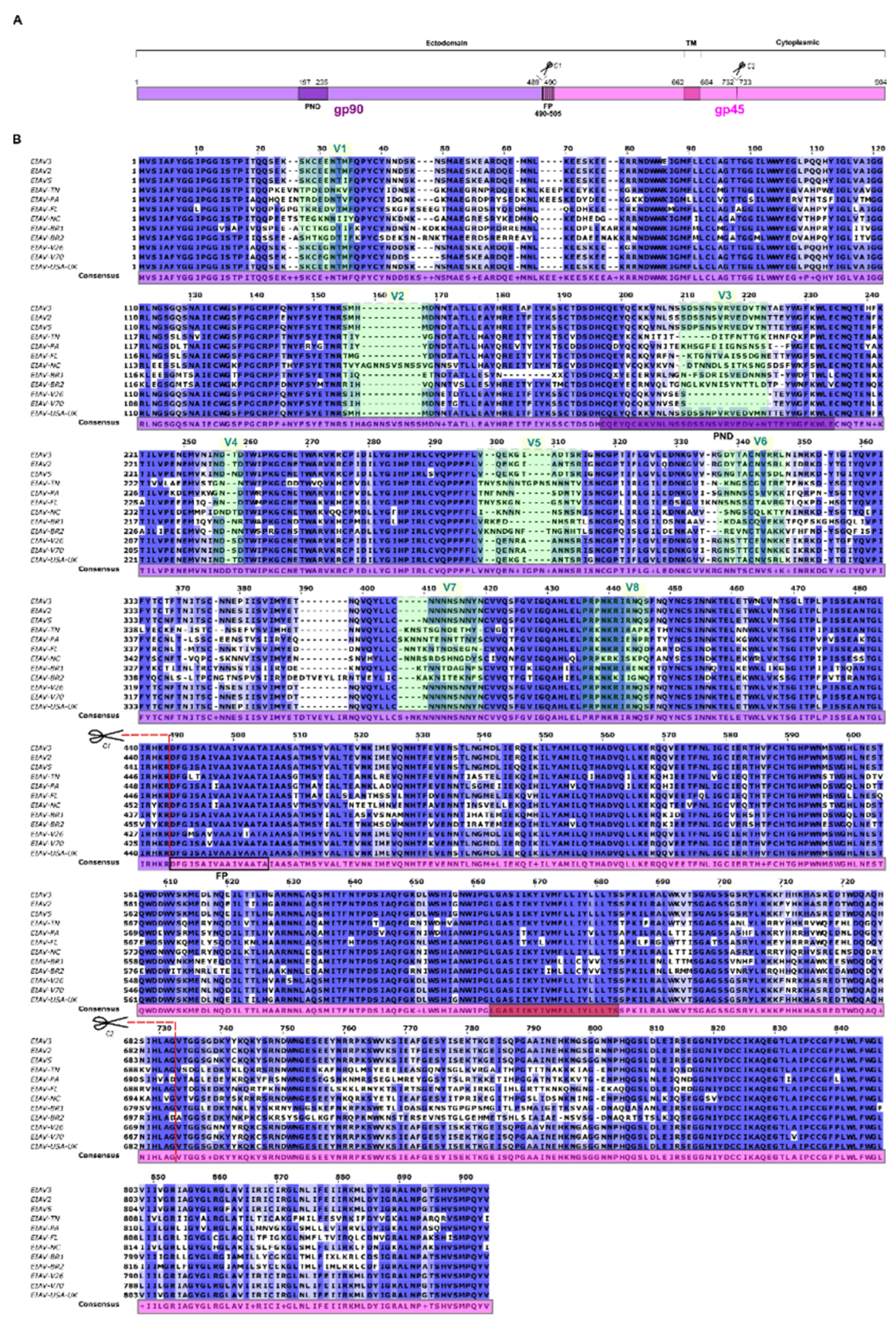

3.2. MSA and Definition of Consensus Sequence

3.3. Epitope Prediction

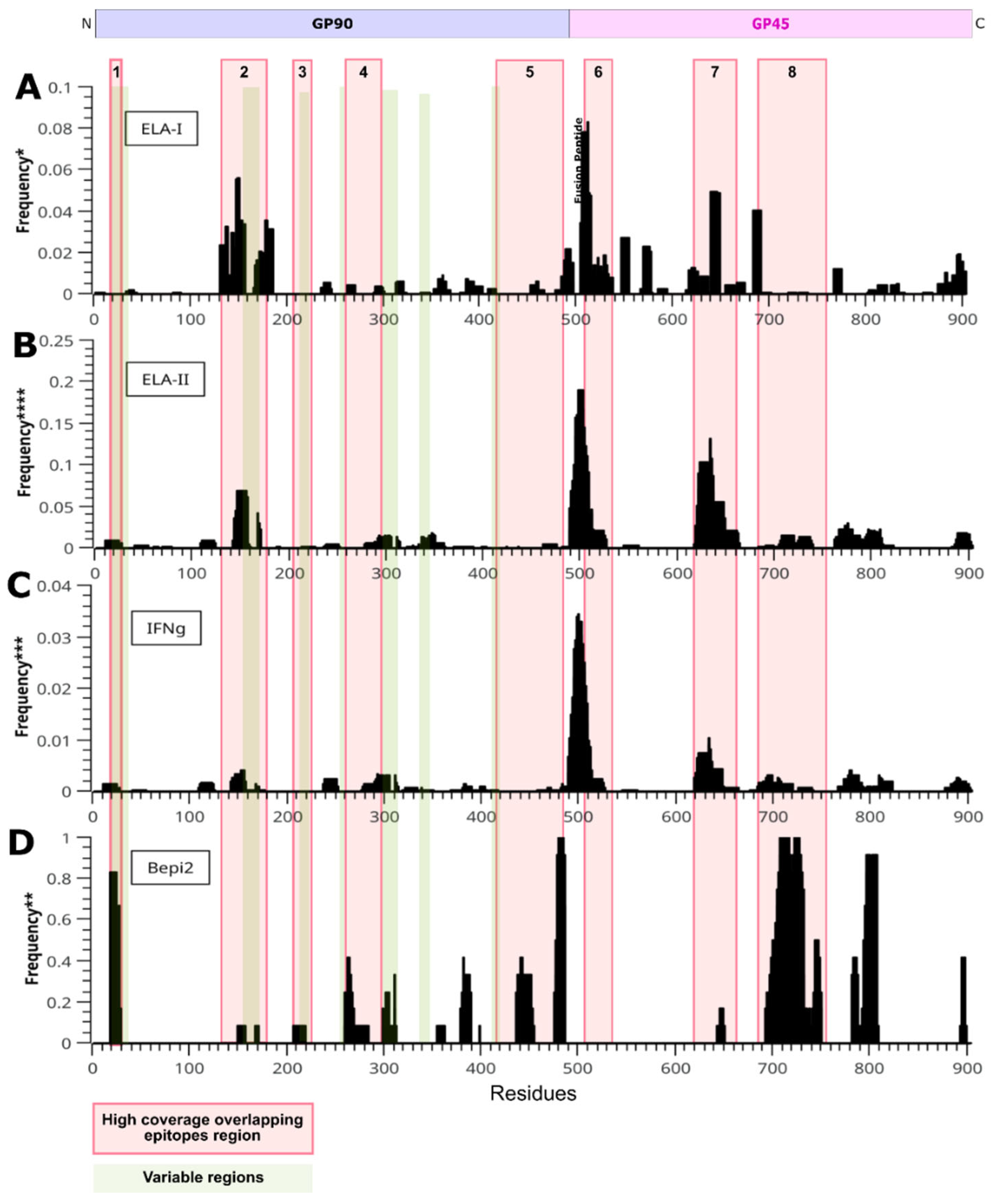

3.3.1. CD8+ T-Cell Epitopes

3.3.2. CD4+ T-Cell Epitopes

3.3.3. IFN-γ Inducing MHC Class II binding Peptides

3.3.4. B-Cell Epitope Prediction

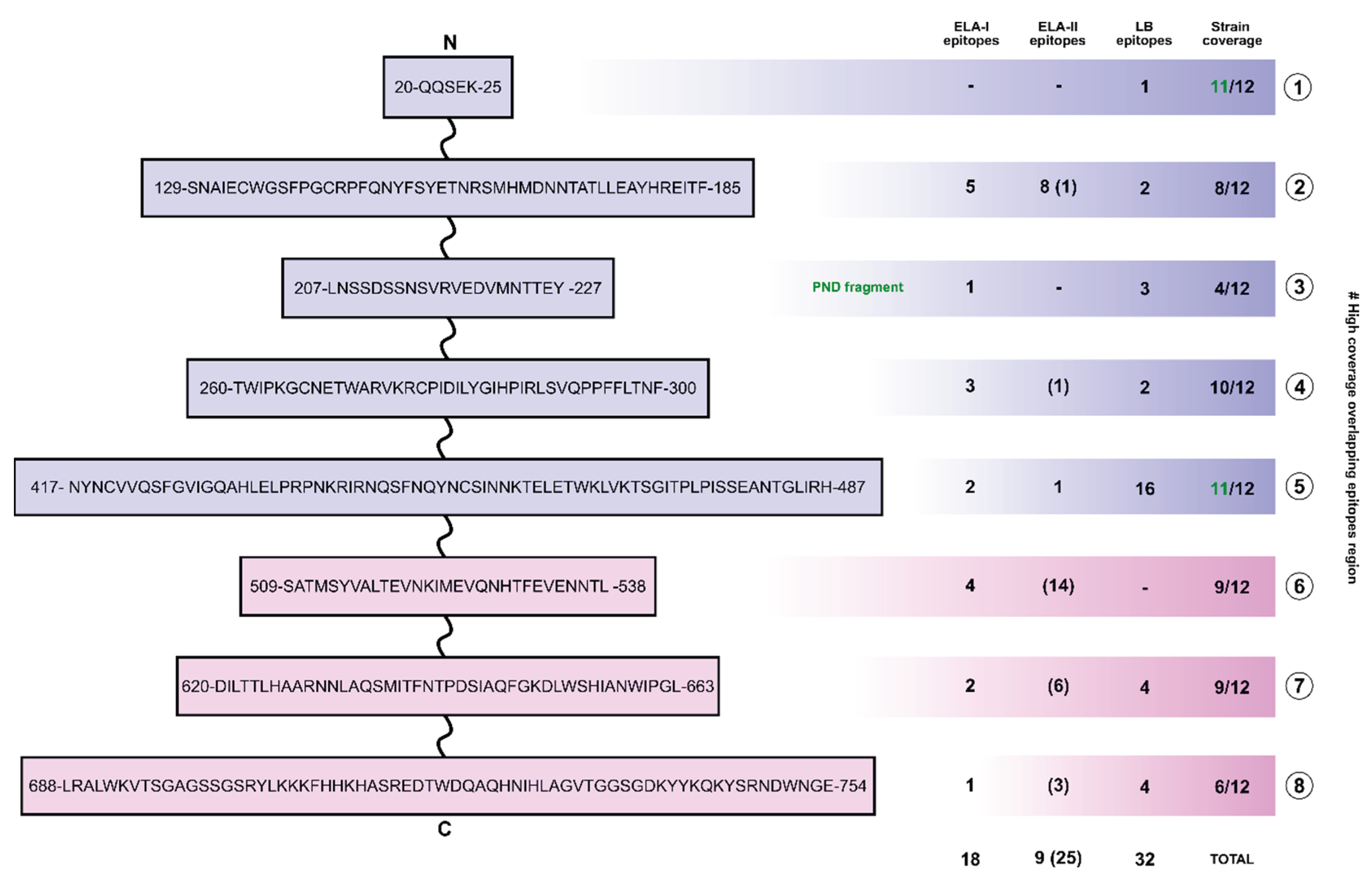

3.4. Selection of Polypeptide Sequences with Overlapping Epitopes

3.5. Vaccinal Antigen Design and in Silico Characterization

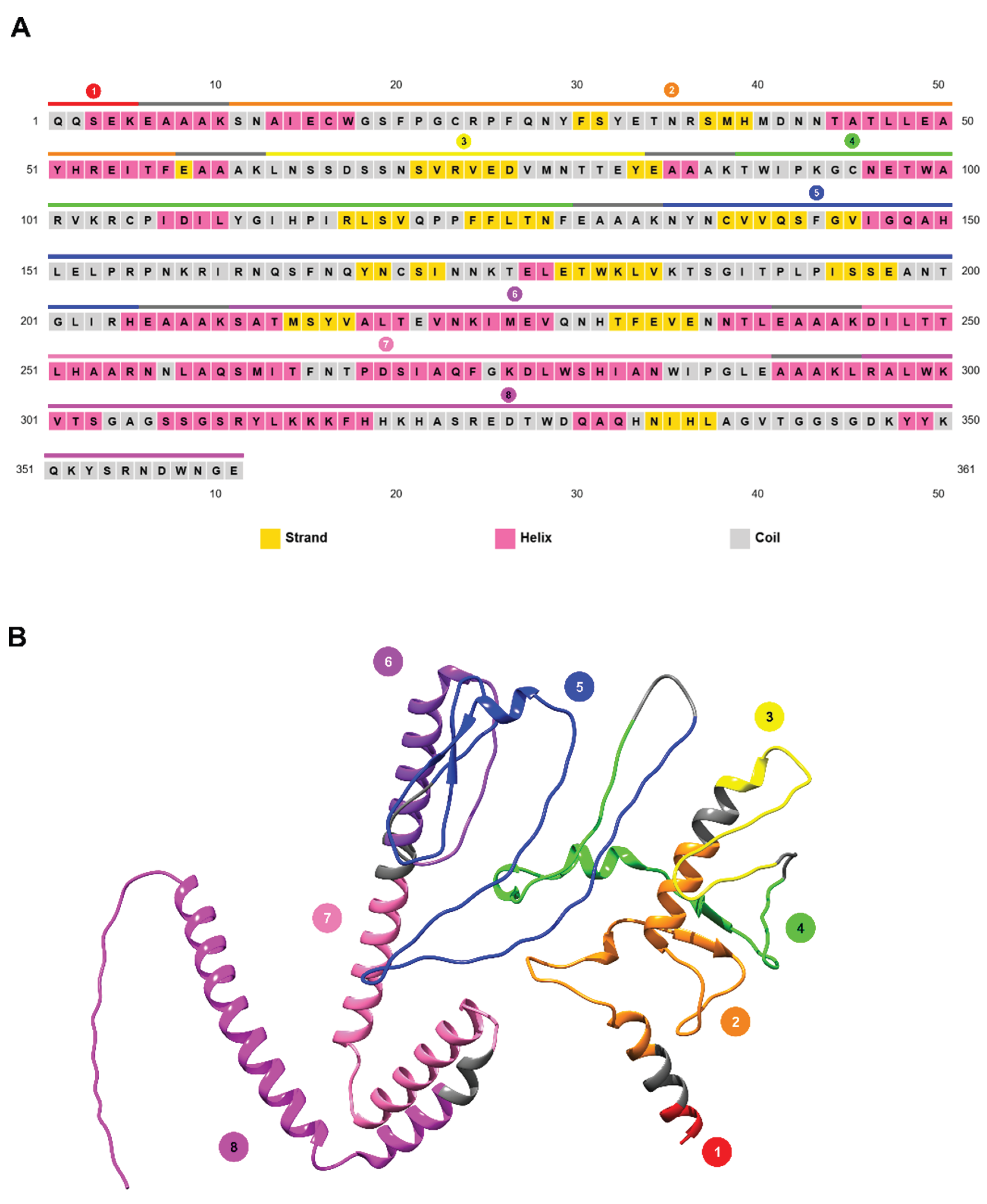

3.5.1. Linker Optimization

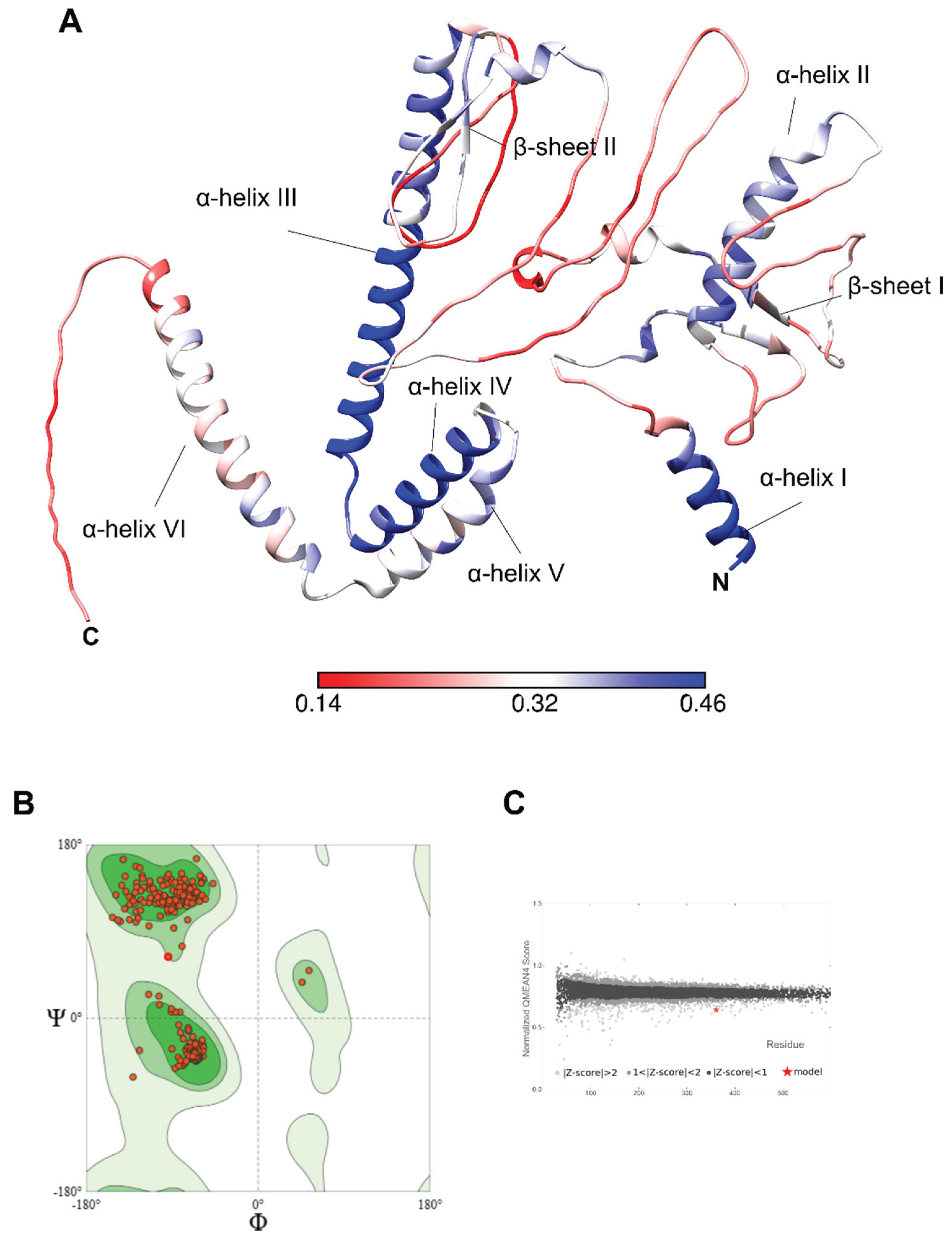

3.5.2. Prediction of the Vaccinal Candidate Structure

| Linker | Residue number | MW | IP | Instability Index | Aliphatic Index | GRAVY | CamSol | SoluProt | Vaxijen 3.0 |

ANTIGEN pro |

Aller TOPv.2 |

AllergenFP | Toxinpred2 |

| Criteria for acceptance | - | - | - | < 40 | > 60 | < 0 | > 0,80 | > 0,50 | > 90% | > 0,90 | Non allergen | Non allergen | (-) |

| AAY | 347 | 39351 | 8.60 | 42.42 | 70.09 | -0.51 | 0,19 | 0,60 | 100% | 0.93 | Probable allergen | Non Allergen | (-) |

| GGGGS | 361 | 39421 | 8.65 | 47.57 | 63.49 | -0.58 | 0,83 | 0,61 | 100% | 0.97 | Non Allergen | Probable allergen | (-) |

| EAAAK | 361 | 40507 | 8.60 | 39.40 | 69.31 | -0.57 | 0,91 | 0,59 | 100% | 0.95 | Non Allergen | Non Allergen | (-) |

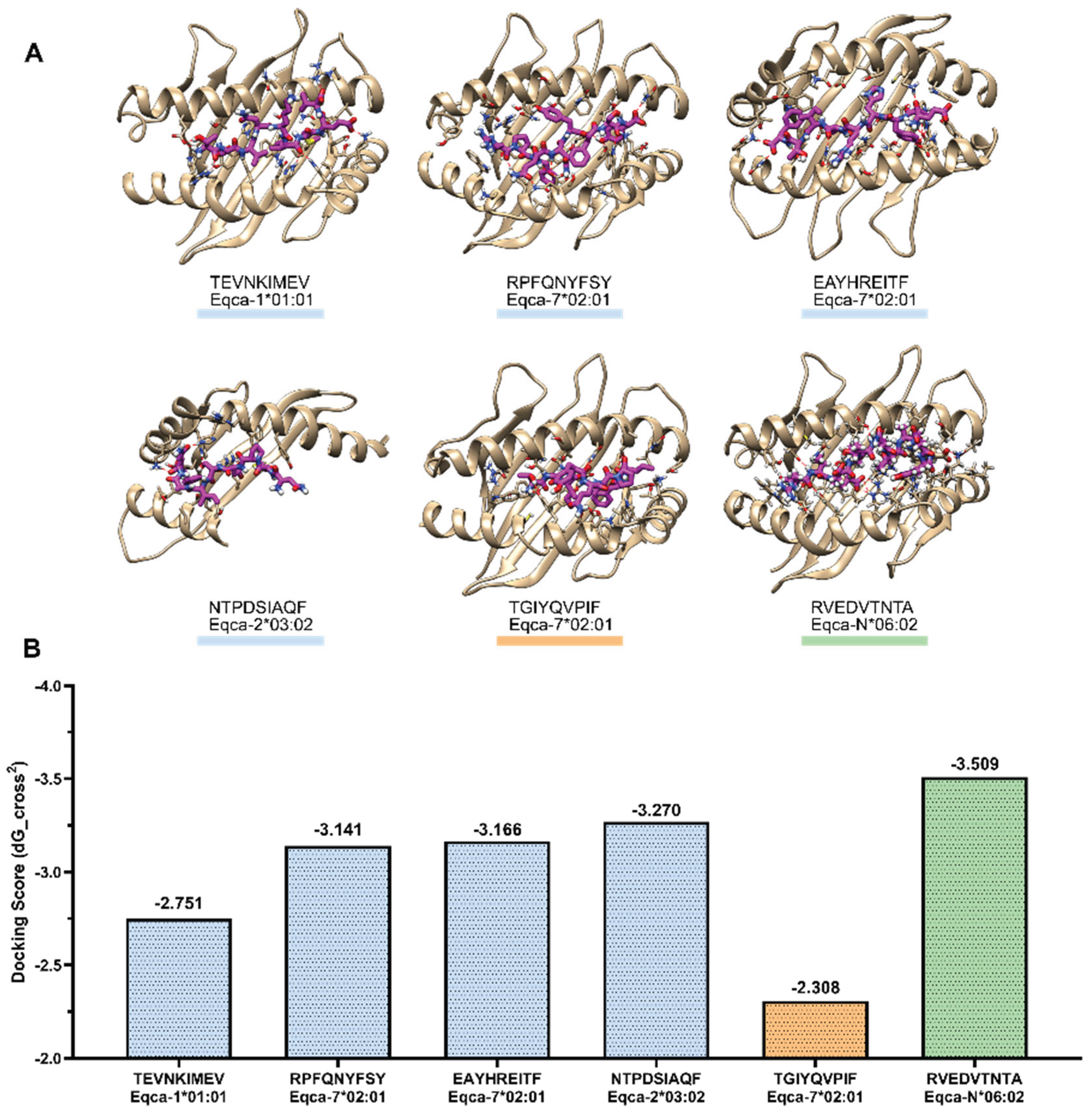

3.6. Docking of CD8+ T-Cell Epitopes on ELA-I

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | aminoacid |

| BCR | B-cell Receptor |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte |

| EIAV | Equine Infectious Anemia Virus |

| ELA | Equine Lymphocyte Antigen |

| ELR-1 | Equine Lentivirus Receptor-1 |

| ENV | Envelope |

| gp45 | Glycoprotein 45 |

| gp90 | Glycoprotein 90 |

| hcENV | High coverage ENV based chimera |

| IFN--γ | Gamma interferon |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MSA | Multiple Sequence Alignment |

References

- Sellon, D.C.; Fuller, F.J.; McGuire, T.C. The immunopathogenesis of equine infectious anemia virus. Virus Res. 1994, 32, 111–138. [CrossRef]

- Montelaro, R.C.; Ball, J.M.; Rushlow, K.E. Equine Retroviruses. The Retroviridae [Internet]. 1993 [cited 2025 Nov 30];257–360. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4899-1627-3_5.

- Hussain, K.A.; Issel, C.J.; Schnorr, K.L.; Rwambo, P.M.; West, M.; Montelaro, R.C. Antigenic mapping of the envelope proteins of equine infectious anemia virus: identification of a neutralization domain and a conserved region on glycoprotein 90. Arch. Virol. 1988, 98, 213–224. [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.H.; Ball, J.M.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C.; E Rushlow, K. Analysis of equine humoral immune responses to the transmembrane envelope glycoprotein (gp45) of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 1013–1018. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jin, S.; Jin, J.; Li, F.; Montelaro, R.C. A tumor necrosis factor receptor family protein serves as a cellular receptor for the macrophage-tropic equine lentivirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 9918–9923. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, B.; Jin, J.; Montelaro, R.C. Binding of equine infectious anemia virus to the equine lentivirus receptor-1 is mediated by complex discontinuous sequences in the viral envelope gp90 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2011–2019. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, X.-F.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Ren, H.; Liu, C.; Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Na, L.; Liu, D.; et al. Env diversity-dependent protection of the attenuated equine infectious anaemia virus vaccine. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1309–1320. [CrossRef]

- Henzy, J.E.; Johnson, W.E. Pushing the endogenous envelope. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120506. [CrossRef]

- Mealey RH, Zhang B, Leib SR, Littke MH, McGuire TC. Epitope specificity is critical for high and moderate avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes associated with control of viral load and clinical disease in horses with equine infectious anemia virus. Virology [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2025 Nov 30];313:537–52. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0042682203003441?via%3Dihub.

- Fraser, D.G.; Oaks, J.L.; Brown, W.C.; McGuire, T.C. Identification of broadly recognized, T helper 1 lymphocyte epitopes in an equine lentivirus. Immunology 2002, 105, 295–305. [CrossRef]

- Tagmyer, T.L.; Craigo, J.K.; Cook, S.J.; Even, D.L.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Envelope Determinants of Equine Infectious Anemia Virus Vaccine Protection and the Effects of Sequence Variation on Immune Recognition. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 4052–4063. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, T.C.; Leib, S.R.; Lonning, S.M.; Zhang, W.; Byrne, K.M.; Mealey, R.H. Equine infectious anaemia virus proteins with epitopes most frequently recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes from infected horses. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 2735–2739. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cook, F.R.; Cook, S.J.; Craigo, J.K.; Even, D.L.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C.; Horohov, D.W. The determination of in vivo envelope-specific cell-mediated immune responses in equine infectious anemia virus-infected ponies. Veter- Immunol. Immunopathol. 2012, 148, 302–310. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, T.C.; Leib, S.R.; Mealey, R.H.; Fraser, D.G.; Prieur, D.J. Presentation and Binding Affinity of Equine Infectious Anemia Virus CTL Envelope and Matrix Protein Epitopes by an Expressed Equine Classical MHC Class I Molecule. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 1984–1993. [CrossRef]

- Soutullo A, Verwimp V, Riveros M, Pauli R, Tonarelli G. Design and validation of an ELISA for equine infectious anemia (EIA) diagnosis using synthetic peptides. Vet Microbiol [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2025 Nov 30];79:111–21. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378113500003527?via%3Dihub.

- Soutullo, A.; García, M.; Bailat, A.; Racca, A.; Tonarelli, G.; Borel, I.M. Antibodies and PMBC from EIAV infected carrier horses recognize gp45 and p26 synthetic peptides. Veter- Immunol. Immunopathol. 2005, 108, 335–343. [CrossRef]

- Bailat, A.S.; Soutullo, A.R.; García, M.I.; Veaute, C.M.; Garcia, L.; Racca, A.L.; Borel, I.S.M. Effect of two synthetic peptides mimicking conserved regions of equine infectious anemia virus proteins gp90 and gp45 upon cytokine mRNA expression. Arch. Virol. 2008, 153, 1909–1915. [CrossRef]

- Russi, R.C.; Garcia, L.; Cámara, M.S.; Soutullo, A.R. Validation of an indirect in-house ELISA using synthetic peptides to detect antibodies anti-gp90 and gp45 of the equine infectious anaemia virus. Equine Veter- J. 2022, 55, 111–121. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Lin, Y.; Ma, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Yang, K.; Zhou, J.; Shen, R.; Zhang, X.; et al. A Pilot Study Comparing the Development of EIAV Env-Specific Antibodies Induced by DNA/Recombinant Vaccinia-Vectored Vaccines and an Attenuated Chinese EIAV Vaccine. Viral Immunol. 2012, 25, 477–484. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-Z.; Shen, R.-X.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Deng, X.-L.; Cao, X.-Z.; Wang, X.-F.; Ma, J.; Jiang, C.-G.; Zhao, L.-P.; Lv, X.-L.; et al. An attenuated EIAV vaccine strain induces significantly different immune responses from its pathogenic parental strain although with similar in vivo replication pattern. Antivir. Res. 2011, 92, 292–304. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ma, J.; Zhao, L.; Lv, X.; Wang, F.; Shen, R.; Kong, X.; et al. Genomic comparison between attenuated Chinese equine infectious anemia virus vaccine strains and their parental virulent strains. Arch. Virol. 2010, 156, 353–357. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.-F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhong, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X. Characterization of EIAV env Quasispecies during Long-Term Passage In Vitro: Gradual Loss of Pathogenicity. Viruses 2019, 11, 380. [CrossRef]

- Korber, B.; Hraber, P.; Wagh, K.; Hahn, B.H. Polyvalent vaccine approaches to combat HIV-1 diversity. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 275, 230–244. [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, J.L.; Bonsignori, M. Multi-Envelope HIV-1 Vaccine Development: Two Targeted Immune Pathways, One Desired Protective Outcome. Viral Immunol. 2018, 31, 124–132. [CrossRef]

- Rappuoli, R.; De Gregorio, E.; Del Giudice, G.; Phogat, S.; Pecetta, S.; Pizza, M.; Hanon, E. Vaccinology in the post−COVID-19 era. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020368118. [CrossRef]

- Oli AN, Obialor WO, Ositadimma M, Ifeanyichukwu, Odimegwu DC, Okoyeh JN, et al. Immunoinformatics and Vaccine Development: An Overview. ImmunoTargets Ther [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Nov 30];9:13–30. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/immunoinformatics-and-vaccine-development-an-overview-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-ITT.

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D480–D489. [CrossRef]

- Kazutaka, K.; Misakwa, K.; Kei-ichi, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Leier, A.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Akutsu, T.; Webb, G.I.; Smith, A.I.; Marquez-Lago, T.; Li, J.; et al. Procleave: Predicting Protease-Specific Substrate Cleavage Sites by Combining Sequence and Structural Information. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2020, 18, 52–64. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell TJ, Rubinsteyn A, Laserson U. MHCflurry 2.0: Improved Pan-Allele Prediction of MHC Class I-Presented Peptides by Incorporating Antigen Processing. Cell Syst [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Nov 30];11:42-48.e7. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2405471220302398.

- Jurtz, V.; Paul, S.; Andreatta, M.; Marcatili, P.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.0: Improved Peptide–MHC Class I Interaction Predictions Integrating Eluted Ligand and Peptide Binding Affinity Data. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3360–3368. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Barker, D.J.; Georgiou, X.; Cooper, M.A.; Flicek, P.; Marsh, S.G.E. IPD-IMGT/HLA Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D948–D955. [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, S.K.; Vir, P.; Raghava, G.P. Designing of interferon-gamma inducing MHC class-II binders. Biol. Direct 2013, 8, 30–30. [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, M.C.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M.; Marcatili, P. BepiPred-2.0: improving sequence-based B-cell epitope prediction using conformational epitopes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W24–W29. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kapoor, P.; Chaudhary, K.; Gautam, A.; Kumar, R.; Raghava, G.P.S. In Silico Approach for Predicting Toxicity of Peptides and Proteins. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cook, S.J.; Craigo, J.K.; Cook, F.R.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C.; Horohov, D.W. Epitope shifting of gp90-specific cellular immune responses in EIAV-infected ponies. Veter- Immunol. Immunopathol. 2014, 161, 161–169. [CrossRef]

- Tagmyer, T.L.; Craigo, J.K.; Cook, S.J.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Envelope-specific T-helper and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses associated with protective immunity to equine infectious anemia virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 1324–1336. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, T.C.; Fraser, D.G.; Mealey, R.H. Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes and Neutralizing Antibody in the Control of Equine Infectious Anemia Virus. Viral Immunol. 2002, 15, 521–531. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Gao, G.F.; Xia, C. Structural Illumination of Equine MHC Class I Molecules Highlights Unconventional Epitope Presentation Manner That Is Evolved in Equine Leukocyte Antigen Alleles. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 1943–1954. [CrossRef]

- Craigo, J.K.; Ezzelarab, C.; Cook, S.J.; Chong, L.; Horohov, D.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Envelope Determinants of Equine Lentiviral Vaccine Protection. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e66093. [CrossRef]

- Burton DR. What Are the Most Powerful Immunogen Design Vaccine Strategies? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Nov 30];9:a030262. Available from: http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/content/9/11/a030262.full.

- Craigo, J.K.; Durkin, S.; Sturgeon, T.J.; Tagmyer, T.; Cook, S.J.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Immune suppression of challenged vaccinates as a rigorous assessment of sterile protection by lentiviral vaccines. Vaccine 2007, 25, 834–845. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Blythe, D.C.; Loyd, H.; Mealey, R.H.; Tallmadge, R.L.; Dorman, K.S.; Carpenter, S. Decreased Infectivity of a Neutralization-Resistant Equine Infectious Anemia Virus Variant Can Be Overcome by Efficient Cell-to-Cell Spread. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 10421–10424. [CrossRef]

- Sponseller, B.A.; Sparks, W.O.; Wannemuehler, Y.; Li, Y.; Antons, A.K.; Oaks, J.L.; Carpenter, S. Immune selection of equine infectious anemia virus env variants during the long-term inapparent stage of disease. Virology 2007, 363, 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.M.; Payne, S.L.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. EIAV genomic organization: Further characterization by sequencing of purified glycoproteins and cDNA. Virology 1988, 165, 601–605. [CrossRef]

- Bastian, F.B.; Roux, J.; Niknejad, A.; Comte, A.; Costa, S.S.F.; de Farias, T.M.; Moretti, S.; Parmentier, G.; de Laval, V.R.; Rosikiewicz, M.; et al. The Bgee suite: integrated curated expression atlas and comparative transcriptomics in animals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D831–D847. [CrossRef]

- Rice, N.R.; E Henderson, L.; Sowder, R.C.; Copeland, T.D.; Oroszlan, S.; Edwards, J.F. Synthesis and processing of the transmembrane envelope protein of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 1990, 64, 3770–3778. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-F.; Wang, Y.-H.; Bai, B.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, M.; Wang, X. Truncation of the Cytoplasmic Tail of Equine Infectious Anemia Virus Increases Virion Production by Improving Env Cleavage and Plasma Membrane Localization. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0108721. [CrossRef]

- Ricotti S, Barcarolo M, Garcia M, Soutullo A. Differences of immune Env-specific responses between newly EIAV infected and inapparent carrier horses. Front Immunol. 2015;6.

- Craigo, J.K.; Zhang, B.; Barnes, S.; Tagmyer, T.L.; Cook, S.J.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Envelope variation as a primary determinant of lentiviral vaccine efficacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 15105–15110. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, H.; Wei, L.; Xiang, W.; Shen, R.; Shao, Y. Correlation between the induction of Th1 cytokines by an attenuated equine infectious anemia virus vaccine and protection against disease progression. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 998–1004. [CrossRef]

- Wagner B, Goodman LB, Babasyan S, Freer H, Torsteinsdóttir S, Svansson V, et al. Antibody and cellular immune responses of naïve mares to repeated vaccination with an inactivated equine herpesvirus vaccine. Vaccine [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Nov 30];33:5588–97. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264410X15012530?via%3Dihub.

- Berg, F.T.v.D.; Makoah, N.A.; Ali, S.A.; Scott, T.A.; Mapengo, R.E.; Mutsvunguma, L.Z.; Mkhize, N.N.; Lambson, B.E.; Kgagudi, P.D.; Crowther, C.; et al. AAV-Mediated Expression of Broadly Neutralizing and Vaccine-like Antibodies Targeting the HIV-1 Envelope V2 Region. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 14, 100–112. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Su, X.; Si, L.; Lu, L.; Jiang, S. The development of HIV vaccines targeting gp41 membrane-proximal external region (MPER): challenges and prospects. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 596–615. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhang X, Zhao X, Yuan M, Zhang K, Dai J, et al. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement: ″Evil″ Antibodies Favorable for Viral Infections. Viruses 2022, Vol 14, Page 1739 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Nov 30];14:1739. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/14/8/1739/htm.

- Ball, J.M.; E Rushlow, K.; Issel, C.J.; Montelaro, R.C. Detailed mapping of the antigenicity of the surface unit glycoprotein of equine infectious anemia virus by using synthetic peptide strategies. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 732–742. [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, V.S.; C., V.T.; K., A.P.; Srirama, K. Design of a multi-epitope-based vaccine targeting M-protein of SARS-CoV2: an immunoinformatics approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 40, 2963–2977. [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhu, N.; Xie, J. Immunoinformatic Identification of Multiple Epitopes of gp120 Protein of HIV-1 to Enhance the Immune Response against HIV-1 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2432. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Lang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Han, X.; Luo, L.; Duan, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; et al. Highly scalable prefusion-stabilized RSV F vaccine with enhanced immunogenicity and robust protection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Kang, Y.-F.; Fang, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-N.; Bu, G.-L.; Wang, A.-J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, C.; et al. A gB nanoparticle vaccine elicits a protective neutralizing antibody response against EBV. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 1882–1897.e10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, W.; Gao, Z.; Chang, Y.; Yang, S.; Peng, Q.; Ge, S.; Kang, B.; Shao, J.; Chang, H. Antigenic and immunogenic properties of recombinant proteins consisting of two immunodominant African swine fever virus proteins fused with bacterial lipoprotein OprI. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Pang, F.; Long, Q.; Liang, S. Designing a multi-epitope subunit vaccine against Orf virus using molecular docking and molecular dynamics. Virulence 2024, 15, 2398171. [CrossRef]

- Tarrahimofrad, H.; Rahimnahal, S.; Zamani, J.; Jahangirian, E.; Aminzadeh, S. Designing a multi-epitope vaccine to provoke the robust immune response against influenza A H7N9. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Abbasi, S.W.; Yousaf, M.; Ahmad, S.; Muhammad, K.; Waheed, Y. Design of a Multi-Epitopes Vaccine against Hantaviruses: An Immunoinformatics and Molecular Modelling Approach. Vaccines 2022, 10, 378. [CrossRef]

- Scheiblhofer, S.; Laimer, J.; Machado, Y.; Weiss, R.; Thalhamer, J. Influence of protein fold stability on immunogenicity and its implications for vaccine design. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2017, 16, 479–489. [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Moreau, V. In silico designing breast cancer peptide vaccine for binding to MHC class I and II: A molecular docking study. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 65, 110–116. [CrossRef]

- I Abdelmageed, M.; Abdelmoneim, A.H.; I Mustafa, M.; Elfadol, N.M.; Murshed, N.S.; Shantier, S.W.; Makhawi, A.M. Design of a Multiepitope-Based Peptide Vaccine against the E Protein of Human COVID-19: An Immunoinformatics Approach. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2683286. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.W. A combination of epitope prediction and molecular docking allows for good identification of MHC class I restricted T-cell epitopes. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2013, 45, 30–35. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.