1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are RNA viruses with a large genome and critical infectivity. CoVs family includes various viruses, with tropism for humans and animals. Among them, two distinct but very similar Feline Coronaviruses (FCoVs) serotypes are widespread in domestic cats: type 1 FCoV, or feline enteric coronavirus (FeCV), and type 2 FCoV, or mutated feline enteric coronavirus, also known as feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) [

1]. To date, these viruses are still considered fatal for young cats, and the therapies are mainly based on antiviral nucleotides like remdesivir and its analogs. However, no prophylaxis or vaccine is available [

2,

3]: in fact, cases of antibodies-dependent enhancement (ADE) of FIPV infectivity have been observed following the development of the humoral response, which facilitates the entry of the virus in the macrophages, where the pathogen amplifies its replication [

4,

5,

6].

FeCV and FIPV share very similar genetic frameworks with the well-known SARS-CoV-2, a highly pathogenic virus for humans whose infection has also been reported in domestic animals but is relatively uncommon in cats [

7,

8]. Currently, the mechanisms underlying the susceptibility of certain animals to SARS-CoV-2 infection are still unclear. We previously demonstrated that the similarity with angiotensin-converting 2 (ACE2), the enzyme responsible for the entry of the virus into the host cells, might be determinant [

9].

The efficiency in the immune response to the viral infection, which is the basis of the virus pathogenicity, includes an interaction of viral antigens with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Two classes of MHC – class I and class II – operate in the capture of antigens deriving from pathogen proteins: class I MHCs bind 8-10 amino acids long antigen peptides to present them to CD8

+CD4

- cytotoxic T lymphocytes to trigger the cell-mediated immune response, while class II MHCs bind 12-24 amino acids long antigen peptides and introduce them to CD4

+ CD8

- T helper cells to stimulate the humoral antibody production by B cells [

10]. Pharmacologically, the importance of MHC as a target for immunodrugs has been widely assessed [

11], and recently, many works reported the use of partial MHC constructs as modulators of T cells and CD74 signalling and thus neuroprotective agents in stroke [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In humans, the group of polymorphic genes encoding for MHCs is also referred to as human leukocyte antigens (HLA). These cell surface receptors are characterized by high sequence variability, mainly in the antigen-binding region. The effectiveness of the immune response depends on the interactions of antigens in the binding pocket of the MHC and how these antigens are presented for interaction with T cells. Recently, it has been demonstrated that an individual susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 is correlated with a specific combination of class I/II HLAs encoded by a specific allele combination. Notably, HLA-C*01 and B*44 alleles have been identified as potential genetic risk factors for COVID-19, contributing to the differences in the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 infection through different populations (e.g., Northern and Southern Italy) [

17].

Analogous to human HLA, the Feline Leukocyte Antigen (FLA), located on the p-arm and the q-arm of the chromosome B2 in cats, mediates the feline immunity response by interacting with antigens derived from pathogens infecting cats [

18,

19].

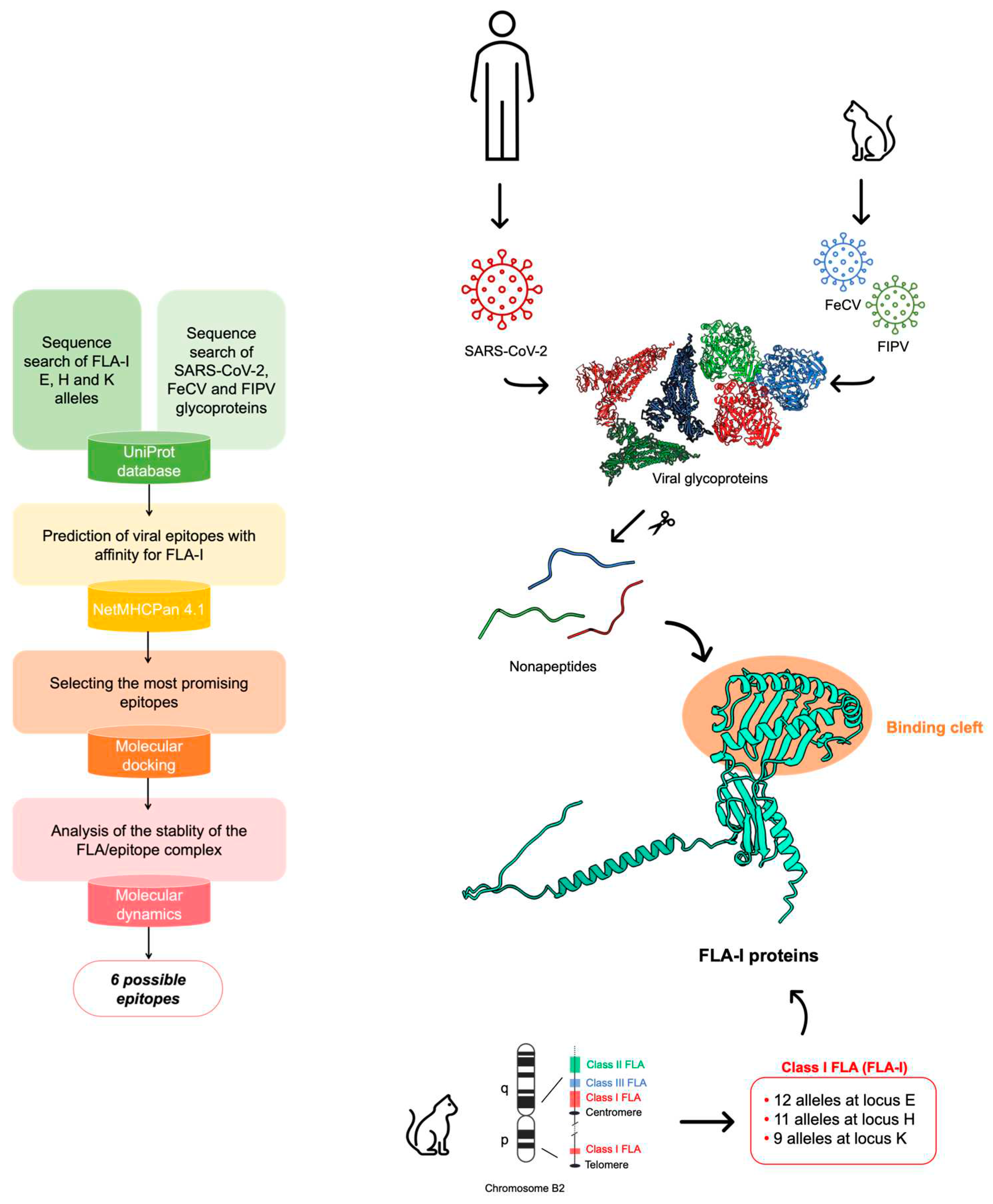

Considering the similarity between these viruses and SARS-CoV-2, in this work, we aim to investigate with a bioinformatic approach whether a specific combination of FLA alleles can favour the individual susceptibility of some cats over others regarding the exposition to FIPV and FeCV. Using SARS-CoV-2 as a model, for which a great amount of structural data is available, we aim to i) identify alleles that potentially correlated with enhanced cell-mediated immunogenic response in domestic cats infected with FCoVs and ii) identify epitopes in CoVs proteins that are most likely to target the proteins encoded by these alleles and iii) conduct a peptide search of the epitopes on viruses infecting with tropism for different species to hypothesize any cross-reaction.

To this aim, we retrieved all the viral glycoprotein sequences belonging to SARS-CoV-2, FeCV, and FIPV to find epitope regions potentially recognized by the MHC receptors encoded in E, H, and K loci of class I FLA (FLA-I). We selected these loci since they were found to restrict antiviral CD8

+ T

-cell effectors [

20], whose response has already been observed to control FIV infections [

21,

22,

23]. Using this biocomputational approach, whose workflow is described in

Figure 1, it was possible to identify six interesting epitopes on viral glycoproteins, together with the most affine proteins encoded by FLA-I alleles that can define a subjective susceptivity of cats with a peculiar genetic makeup over others.

2. Materials and Methods

Epitope mapping, sequence alignment and peptide search

The epitope mapping was performed using the online server NetMHCPan 4.1 [

24] which predicts the affinity of viral epitopes for MHCs using artificial neural networks. The viral glycoprotein sequences retrieved on UniProt database [

25] were uploaded as FASTA type. We selected to restrain nonapeptides from the proteins according to the literature, which suggests that 9-mers are more affine for class-I FLAs [

18,

20,

26]. The sequences of FLA-I loci E, H and K were manually retrieved from UniProt and uploaded in NetMHCPan. The results were analyzed according to the Mass Spectroscopy Elution Score (EL), selecting the epitopes with scores above 0.5.

The sequences with an EL score above 0.8 were aligned using the

Multiple Sequence Alignment tool included in Maestro 2023-2 [

39]. The search of the epitope sequences database was performed using BLAST [

40] included in UniProt, and the peptides with an identity of 90-100% were considered.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking calculations were carried out with HPepDock [

27] for the

ab initio building of the binding complexes and AutoDock CrankPep (ADCP [

28]). FLA-I 3D structures retrieved from UniProt were set as receptor proteins. The grid boxes were centered on the residues included in the two helices that overhang the large binding site. The HPepDock results were used as reference for the refinement of the binding poses performed by ADCP. The peptides were sampled in extended and helix conformations. Results were analysed according to the lowest docking scores (kcal/mol), which indicate the binding poses with the most favourable interaction energies, and lowest values of RMSD, which represent the reproducibility of the poses. Molecular visualization was performed with Maestro [

39].

Protein structure prediction with AlphaFold2

The 3D structure prediction of the unknown moieties of R1ab protein was performed with AlphaFold2 [

30] included in ColabFold server [

31] with the parameters’ multi-sequence alignment mode (MSA mode) set as mmseqs2_uniref_env and pair_mode set as unpaired_paired. The models were ranked according to the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) score and the predicted alignment error (PAE), indicating a distance score between pairs of residues with low values specifying low errors.

Molecular dynamics

To perform MD simulations we prepared the ADCP deriving complexes using the

Protein Preparation Wizard tool included in Maestro [

39], which allowed to add the side chains in the peptides, minimize the energies and optimize the bond angles and lengths. MD simulations were run using GROMACS 2020.3 [

41]. The topology files were generated using CHARMM36 all-atom force field [

42]. The complexes were solvated in cubic boxes with the TIP4P water model. Na

+ and Cl

- ions were added to neutralize the charge of the system. After a minimization using the steepest descent integrator, the system was equilibrated at the average body temperature in cats of 311.65 K for 1 ns as NVT ensemble and at 1 atm pressure using Berendsen algorithm NpT ensemble for 1 ns. The outputs were used for a MD simulation using Particle Mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics under NpT conditions. Coordinates were saved every 100 ps. Trajectory files containing the coordinates of the receptor-ligand complex at different time steps (from 100 ps to 10 ns) were fitted in the box and converted in PDB coordinates by using

trjconv tool of GROMACS. The structures were visualized with Maestro by Schrödinger [

39]. Analyses of RMSD, number of bonds (H-bonds and neighbors within 0.35 nm) and short-range interaction energies (Coulomb and Lennard-Jones) between the two energy groups (set as receptor and peptides) were carried out for the MD simulations of each system using

rms,

hbond and

energy tools of GROMACS.

3. Results

Epitope mapping

We performed an exploratory epitope mapping using the online server NetMHCPan 4.1 [

24]. To predict specific bindings of MHC with epitopes of any length, the service requires the amino acid sequences of the FLA-I of interest. To this purpose, among the entries in UniProtKB database [

25] marked as “reviewed”, i.e. entries with manually annotated records, we selected 12 variants for FLA-I E, 11 for FLA-I H, and 9 for FLA-I K (

Table S1). Concerning the restrained peptide sequences, we considered only the entries marked as “reviewed” of the viral glycoproteins from the three CoVs under scrutiny: SARS-CoV-2, FIPV, and FeCV (

Table S2). The epitope mapping was carried out by restraining the search to 9 amino acid long epitope peptides [

18,

20,

26]. Outcomes were filtered according to their Mass Spectrometry Eluted Ligands (EL) score. Two EL score cut-offs were considered to select the best predictions: 0.5 for all the best results and 0.8 for a refinement of the outputs.

We obtained outputs as follows:

a) the data relative to the 12 FLA-I E allele variants indicate that the protein encoded by E*00101 allele binds viral epitopes with the best EL scores: 41 having EL score > 0.8 and 332 > 0.5. For the remaining alleles in the E locus, very few epitopes are selected with a score > 0.8 (average 3), while a significant number of epitopes are selected with EL score > 0.5 (average 113) (

Table S3).

b) sequences encoded by FLA-I H variants generally interact with a significant number of epitopes with scores > 0.8 (average 25) and a high number with scores > 0.5 (average 334). Epitopes characterized by the best EL scores bind MHC proteins encoded by H*00401, H*008012, H*00701, and H*00501 alleles. (

Table S4)

c) the data relative to FLA-I K variants indicate that 6 out of the nine variants under scrutiny bind none of the epitopes with scores> 0.8 and few epitopes with scores > 0.5 (average 44). Interestingly, the FLA-I K*00801 allele encodes for a sequence binding the highest number of epitopes with a score > 0.9 (15) and, in general, the highest number of peptides with a score > 0.5 (310) (

Table S5).

Regarding the search of epitopes from viral glycoproteins, the analysis indicated that the peptides with the highest EL scores derived from i) - the Spike (S) protein (P0DTC2-SARS CoV-2) (P10033-FIPV) and the Replicase 1ab (R1ab) protein (P0DTD1/P0DTC1-SARS CoV-2) (Q98VG9-FIPV). Research on FeCV proteins did not produce epitopes with significant EL scores.

Sequence alignment

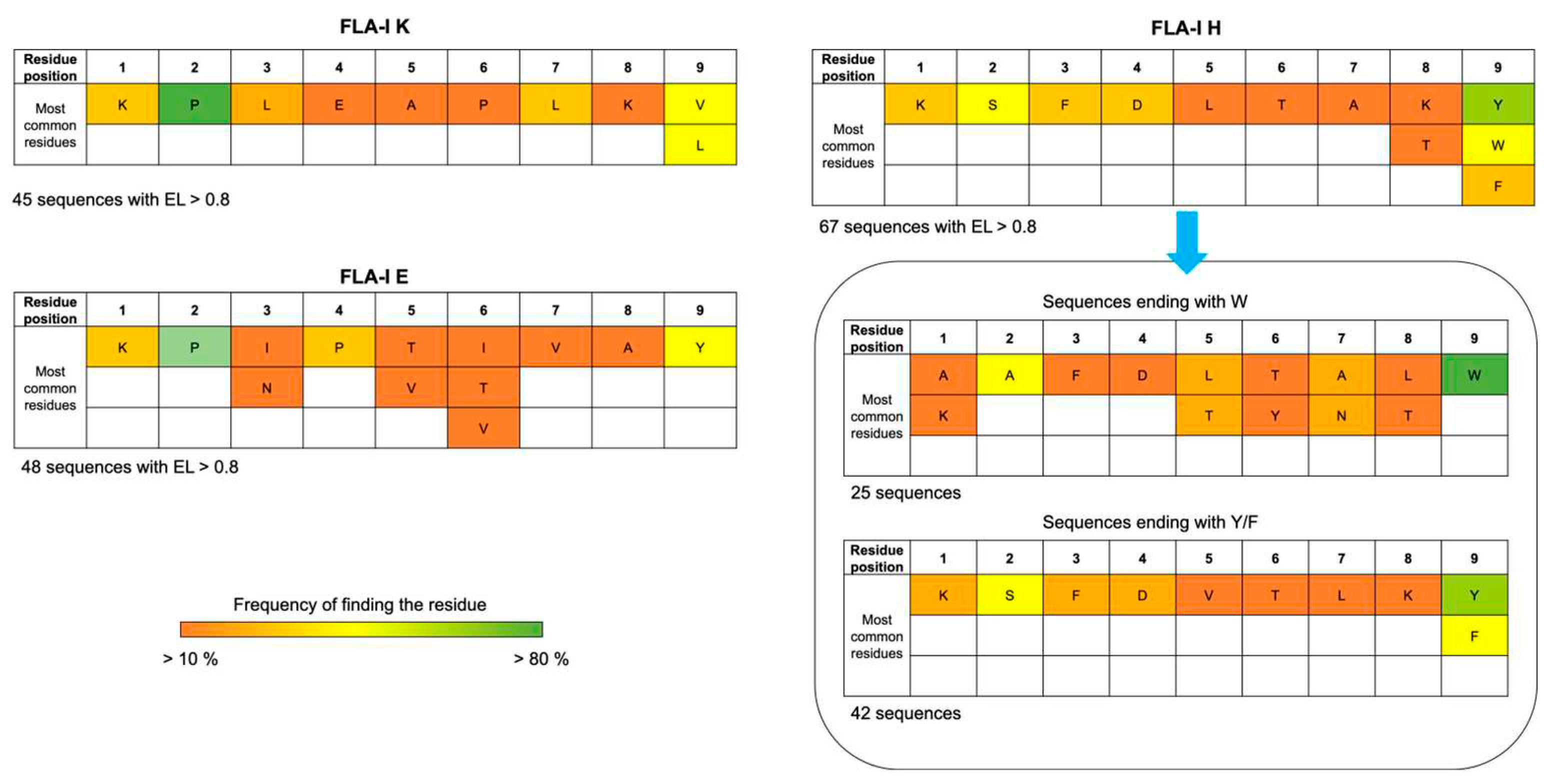

In search of consensus sites, including amino acids essential for interacting with FLA-I receptors, we performed a sequence alignment of the epitopes found, considering the amino acid sequences with the highest EL scores as templates.

Figure 1 shows the frequency of finding a given residue in each position for the epitopes that resulted in binding the three loci of FLA-I with an EL score > 0.8. Accordingly, proline shows a frequency > 80% to occupy position 2 for epitopes recognized by proteins encoded in E and K loci. An aromatic residue is highly recurrent in position 9 for epitopes bound by proteins encoded in E and H loci. Among the epitopes recognized from proteins encoded in the H locus, we identified a set of sequences exhibiting common motifs, consisting of phenylalanine in 3, aspartate in 4, and apolar residues in positions 5 and 6. All the epitopes of the cluster include an aromatic residue at position 9. However, we can identify two subsets, one characterized by an apolar residue in 8 and tryptophan in 9, the other characterized by lysine in 8, and phenylalanine or tyrosine in 9.

Molecular docking

Peptide sequences having EL scores > 0.8 were subjected to molecular docking calculations against the FLA-I proteins. We used HPepDock [

27] for the

ab initio generation of the complexes and AutoDock CrankPep (ADCP [

28]) for the refinement. The peptides were sampled in helix and extended conformations. Considering a docking score lower than -18.0 kcal/mol, the results in

Table 1 report that among the epitopes, the sequence

3574RTIKGTHHW

3582 deriving from SARS-CoV-2 R1a exhibits the best binding parameters in both the conformations against the proteins encoded by alleles FLA-I H*00501, H*00401, H*008012 and FLA-I K*00701. Also, the epitope

6437KQFDTYNLW

6445, derived from SARS-CoV-2 R1ab, is characterized by a consistent binding with FLA-I K*00701 and FLA-I H*00501. Likewise, the epitopes

3756AANELNITW

3764 and

4533RLYYETLSY

4541, deriving from the replicases of FIPV, interact with a remarkable affinity with FLA-I H*00501. Overall, most of the peptides derived from R1ab are characterized by favourable binding parameters against alleles derived from FLA-I H and K loci. On the other hand, the sequences deriving from the spike proteins showed milder yet favourable binding parameters, especially with alleles of FLA-I E and H loci: considering a docking score lower than -15.0 kcal/mol, among FIPV S-deriving epitopes,

1325RPNWTVPEF

1333 was predicted to have good interactions with FLA-I E*00701 and E*00101,

771TTTPNFYYY

779 with H*00501 and

1228TAYETVTAW

1236 with H*00401. Regarding SARS-CoV-2 S-deriving epitopes,

625HADQLTPTW

633 reported the best docking scores in complex with the proteins encoded by the two alleles E*01001 and E*00101, as well as H*008012 and H*00401. Conversely,

321QPTESIVRF

329 reported the best results in complex with the protein encoded by E*00701.

Following these results, the above-mentioned epitopes with the best docking score results will be mentioned in the text as reported in

Table 2:

| Epitope |

Alias |

| SARS-CoV-2 R1a 3574RTIKGTHHW3582

|

sars-rEp1 |

| SARS-CoV-2 R1ab 6437KQFDTYNLW6445

|

sars-rEp2 |

| FIPV R1ab 3756AANELNITW3764

|

fipv-rEp3 |

| FIPV R1ab 4533RLYYETLSY4541

|

fipv-rEp4 |

| SARS-CoV-2 S 625HADQLTPTW633

|

sars-sEp5 |

| SARS-CoV-2 S 321QPTESIVRF329

|

sars-sEp6 |

| FIPV S 1325RPNWTVPEF1333

|

fipv-sEp7 |

| FIPV S 771TTTPNFYYY779

|

fipv-sEp8 |

| FIPV S 1228TAYETVTAW1236

|

fipv-sEp9 |

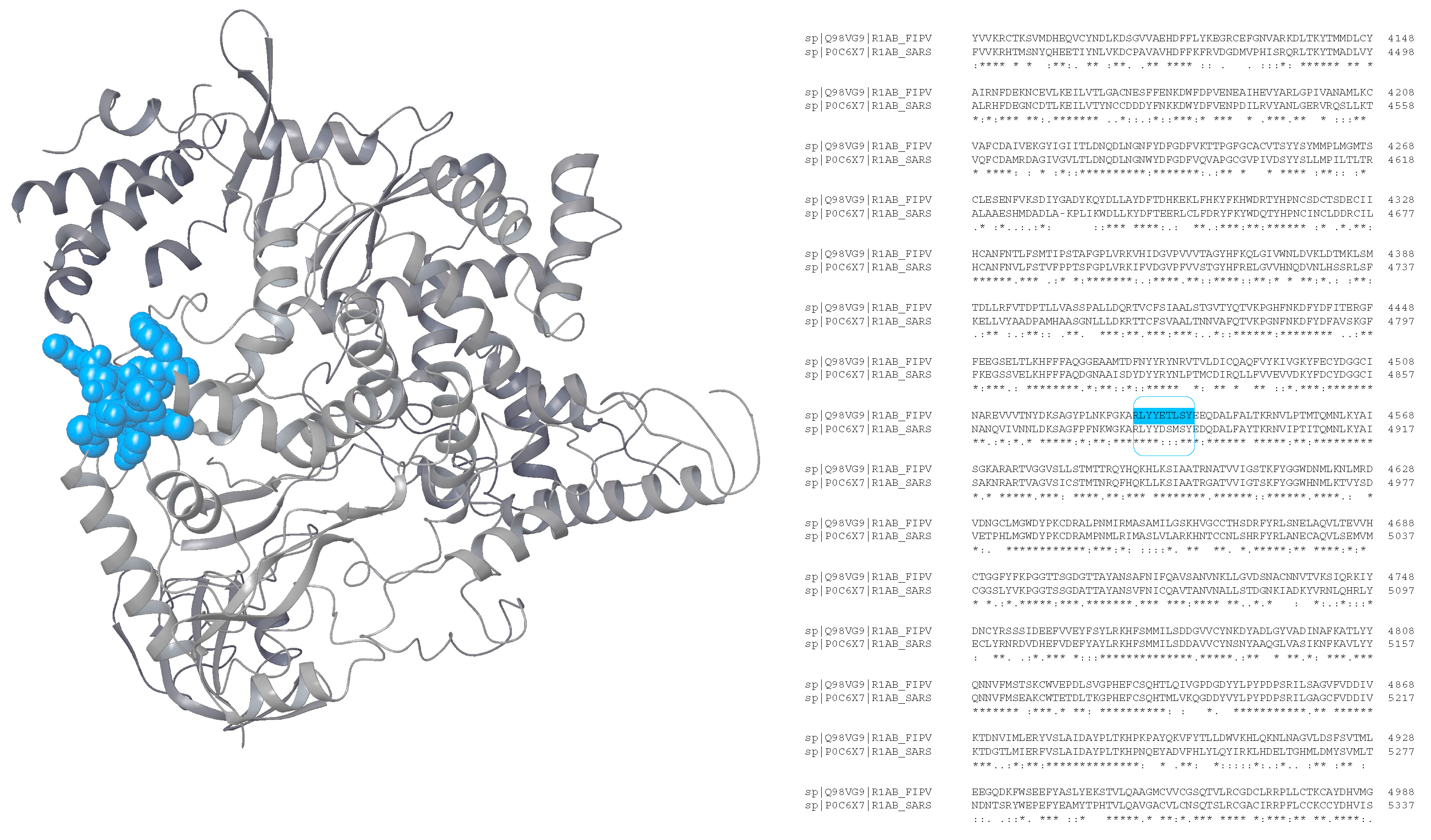

Analysis of possible surface exposition

Analyzing the exposition of the epitopes on a protein is crucial to evaluate their potential immunogenicity and eligibility to be recognized by immunoglobulins. Unfortunately, very little is known about the structural information of the R1ab moieties containing the sequences potentially identified as epitopes. However, it is possible to use SARS-CoV R1ab as a template to analyze the location of the epitopes on the protein surface. Accordingly, the structure having PDB ID 6NUS [

29] was used to locate

fipv-rEp4.

Figure 2 shows the sequence alignments of the R1ab of SARS-CoV and FIPV and the possible localization of

fipv-rEp4 sequence in the folded protein.

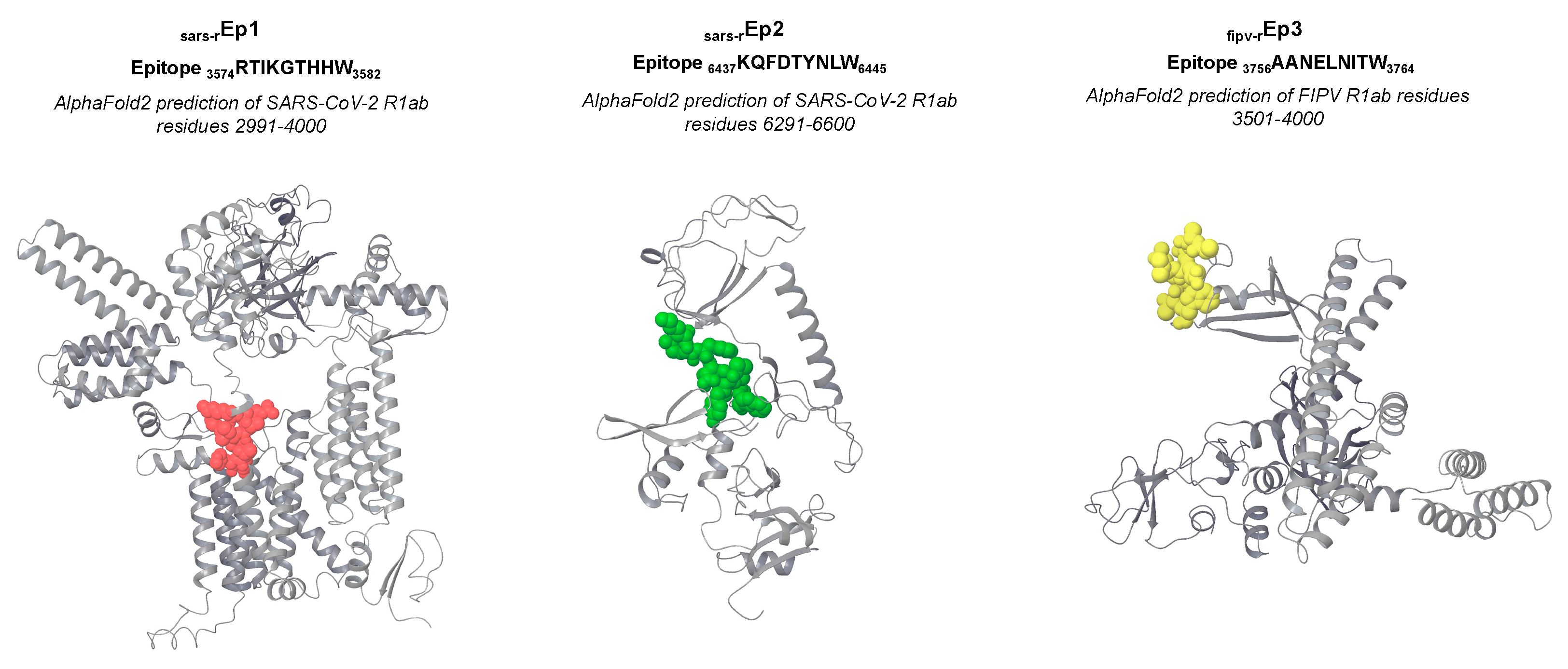

Unfortunately, no experimental structural data matched

sars-rEp1,

sars-rEp2 and

fipv-rEp3. Therefore, we predicted these moieties using AlphaFold2 [

30,

31] and located the epitope on the best-ranked models (

Figure S1), which report a rather good exposition of the epitopes (

Figure 3).

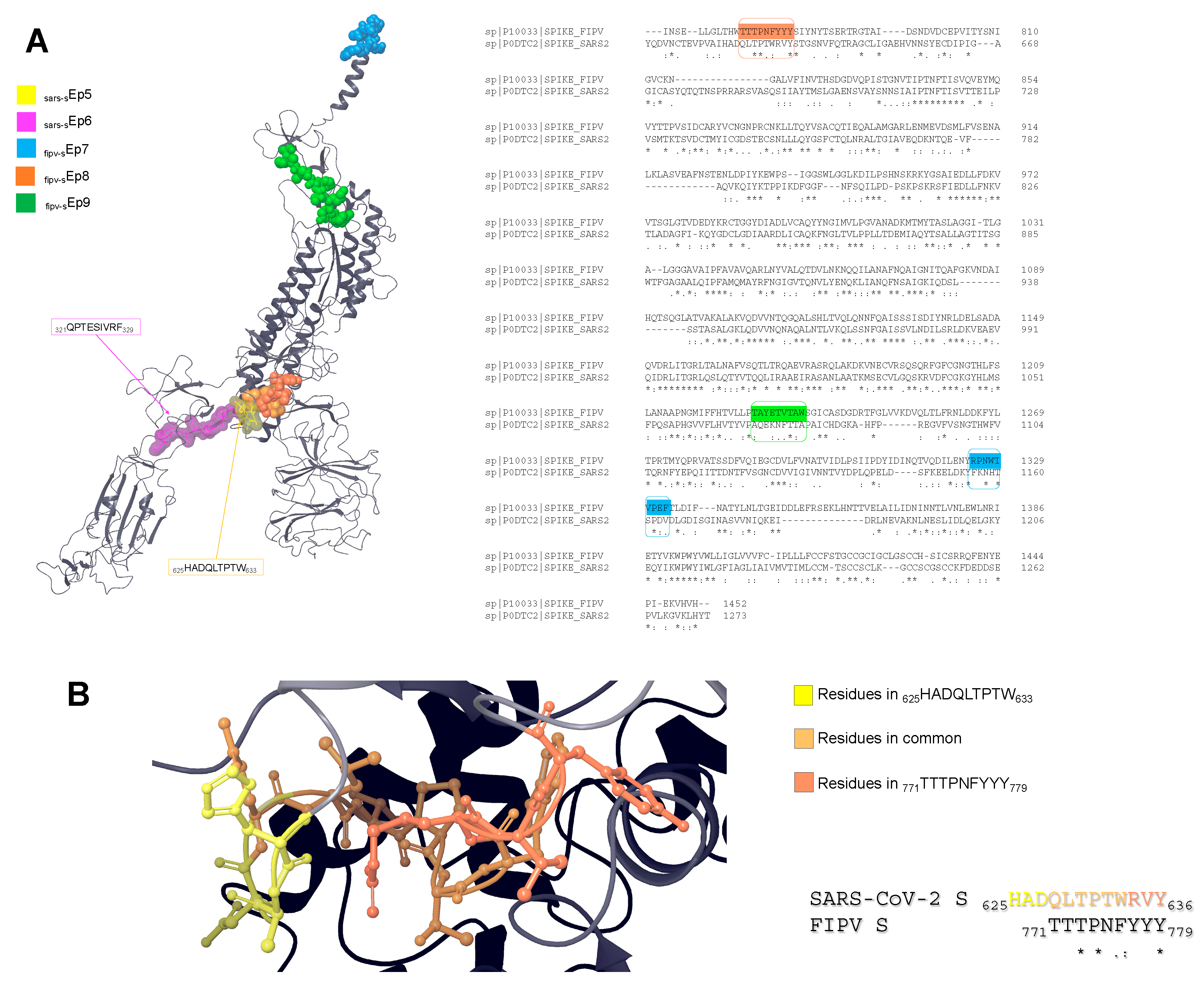

More experimental structural information is available on SARS-CoV-2 S protein, but no structural information is available for FIPV S. Therefore, we aligned FIPV and SARS-CoV-2 S sequences to locate the three FIPV S-deriving epitopes. Then, we searched for the corresponding sequences on the reference SARS-CoV-2 S 3D structure (PDB ID: 7WEB [

32]).

Figure 4 shows the possible localization of the epitopes. Interestingly,

fipv-sEp8 is partially aligned with the SARS-CoV-2 S-deriving epitope

sars-sEp5 (

Figure 4B). Also, the epitope

fipv-sEp9 is well exposed on the protein surface, while

fipv-sEp7 is partly embedded in the transmembrane domain.

Molecular dynamics

The stability of the MHC/peptide complex is essential to develop the immunogenic response. To evaluate the stability of the binding over time, the FLA proteins in complex with some of the peptides previously identified were subjected to 50 ns classical MD simulations in water at the average body temperature of cats (311.65 K). We focused on the epitopes that in the previous analyses reported the best docking scores and the most convenient expositions on the viral glycoprotein surfaces. Accordingly, the binding complexes selected were:

sars-rEp1 with FLA-I H*00501 for the outstanding docking score;

fipv-rEp4 with FLA-I H*00501 for the docking score and the possible localization on the viral glycoprotein surface;

sars-sEp5 with FLA-I E*01001 and sars-sEp6 with FLA-I E*00701 for the docking scores and the position on the viral glycoprotein surface;

fipv-sEp8 with FLA-I H*00501 and fipv-sEp9 with H*00401 for the docking scores and the possible localization on the viral glycoprotein surface.

A total of 12 simulations were run using the peptides in extended and helix conformations derived from the lowest energy docking poses.

From the results in

Figures S2-7, all the epitopes (except for

sars-sEp6) steadily interact with the receptors throughout the simulations in both extended and helix samplings. Only

sars-rEp1 and

fipv-sEp8 bind it in a helix conformation. Overall, the peptides sampled with extended conformations result in higher numbers of established H-bonds and neighbor contacts. Despite the relatively short sequences, peptides bind with low energies and occupy a wider surface in the large MHCs binding site.

Peptide search

We performed a peptide search of the epitopes

sars-rEp1,

fipv-rEp4,

sars-sEp5,

sars-sEp6,

fipv-sEp8 and

fipv-sEp9 on UniProt to understand if the epitopes are unique or repeated on other viral glycoproteins. Our inquiry showed that SARS-CoV-2 deriving epitopes

sars-rEp1,

sars-sEp5 and

sars-sEp6 are unique and only retrieved with little differences in the sequences of other CoVs like bat and pangolin ones. On the other hand, the amino acid composition of the FIPV deriving epitopes is present in different viruses. In particular,

fipv-rEp4 and

fipv-sEp9 are present in canine, porcine, and mink CoVs, while

fipv-sEp8 in canine and porcine CoVs (

Table 2).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The high transmissibility and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in humans have been one of the main factors causing the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, yet SARS-CoV-2 infection has also been reported in domestic animals [

7,

8]; however, human-to-animal transmission seems to be an infrequent event [

7,

9]. Recently, it has been demonstrated in humans that different class I/II HLA alleles may define a distinct susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and its spreading among different populations [

17]. These data suggest that considering the high homology between SARS-CoV-2 and FCoVs genomes, the feline homolog of the HLA, the FLA, may play a role in the transmission of CoVs more commonly reported in this species [

1]. However, while for SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies appear to be effective in controlling the spreading of the COVID-19 disease [

33], in FCoVs an important adverse reaction has been observed when trying to develop the humoral response, namely ADE, which causes a critical improvement of the viral replication in the macrophages [

4,

5,

6].

Following a similar approach, in this work, we presented a bioinformatic investigation to understand the individual susceptibility of domestic cats to develop a cell-mediated immune response after being exposed to epitopes deriving from FeCV and FIPV glycoproteins. Given the large availability of structural information, analysis was performed using SARS-CoV-2 proteins as reference models. This study also aimed to understand the structural keys regulating the interaction of these epitopes with the proteins encoded by the different feline MHC alleles and inducing a distinctive cell-mediated response. The results may allow the design of a strategy to avoid the drawback of ADE derived from the humoral response.

As a first step, an epitope mapping of nonapeptides deriving from viral glycoproteins targeting several proteins encoded by alleles of FLA-I E, H and K loci allowed the selection of the most affine sequences and the most suitable alleles: in fact, this initial analysis indicated that the best resulting epitopes derive from R1ab and S glycoproteins of SARS-CoV-2 and FIPV and that FLA-I H alleles express the most responsive receptors. Analysis of peptide sequences by sequence alignment indicated that in the epitopes with the highest affinity for the protein expressed from FLA-I E and H alleles, it is rather frequent to find an aromatic residue at the end of the sequence, while a proline in position 2 is quite common in epitopes targeting FLA-I E and K; this finding might help in the identification of other viral glycoproteins that are potentially immunogenic in cats, by searching for sequence motifs where proline and aromatic residues are appropriately spaced. Molecular docking of all the epitopes having an EL score > 0.8 with the corresponding receptor evidenced good binding scores for epitopes deriving from the R1ab of SARS-CoV-2 and FIPV in complex with FLA-I H alleles (in particular FLA-I H*00501), and less potent but still favourable binding scores for epitopes deriving from the R1ab of SARS-CoV-2 and FIPV S deriving peptides with FLA-I E and H alleles. To further filter these results, we examined the possible exposition of the epitopes on the protein surface since a better exposition is needed for an epitope to be recognized by the immune system. This analysis led to the selection of well-exposed epitopes on the R1ab surface and, at the same time, to the exclusion of epitopes that are almost embedded in the transmembrane domain of the S protein; moreover, it permitted to discover that

sars-sEp5 and

fipv-sEp8 are possibly situated in the same region, suggesting a high immunogenic potential of this portion. Accordingly, the two mentioned epitopes are located upstream of the receptor binding domain, which is already a known immunogenic moiety for humans [

34,

35,

36]. A total of six epitopes were submitted to 50 ns MD simulations in a complex with the most affine FLA as derived from docking. The epitopes were sampled in the extended and helix conformations to evaluate the effect of the secondary structure on the binding. The results showed that most peptides prefer an extended conformation for a favourable binding, thus managing better to occupy the extended binding cleft of the receptor. Eventually, the study suggests that FLA-H locus is mostly affine for R1ab and FIPV S deriving epitopes, while FLA-I E locus has a good affinity for SARS-CoV-2 S peptides. To understand the possible implications of the epitopes in heterogeneous serological relationships among different coronaviruses, we searched for the six epitope sequences in the UniProt database. SARS-CoV-2 deriving epitopes are rather unique, and slightly different sequences are found in glycoproteins of Bat (RaTG13) and Pangolin (PCoV_GX) coronaviruses, which are closely related and involved in the evolution and cross-species transmission of the virus [

37]. However, these sequences are strictly conserved among all the variants of interest and concern of SARS-CoV-2. FIPV-deriving epitopes were instead retrieved in canine enteric coronavirus (CCoV) and Porcine transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV), confirming the widely demonstrated close relationship between these three coronaviruses [

38].

In conclusion, this investigation suggests that domestic cats expressing FLA-I H*00501 and H*00401 alleles might develop immune responses following the exposition to epitopes deriving from R1ab of FIPV and S of FIPV. In contrast, those expressing FLA-I E*01001 and E*00701 might be more sensitive to epitopes similar to those deriving from SARS-CoV-2 S. Though SARS-CoV-2 is uncommon infection in cats, amino acid sequences derived from SARS-CoV-2 proteins were mainly used as a model in this study [

7]. As a result, they might also help to search for and predict other amino acid sequences with a high affinity for FLAs. Hence, these preliminary findings can be exploited as a tool for predicting CoVs’ sensibility in a wide number of species and, as a future perspective, for developing peptide vaccines able to stimulate the cell-mediated immune systems for untreatable diseases like FIP.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.P., A.G. and A.M.D.; methodology, M.B., D.D.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B., D.D.B. and D.S.; formal analysis, M.B., D.D.B; investigation, D.S.; resources, M.B.; data curation, M.B..; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, D.D.B., A.M.D.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, O.P., A.M.D.; project administration, O.P.; funding acquisition, O.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project entitled “Investigation of the FLA alleles prevalence in cats infected with SARS-CoV-2 and other Coronaviruses” was funded by Fauci Fellowships, National Italian American Foundation, Amb. Peter F. Secchia Building 1860 19th Street, NW Washington, DC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- A. Kipar, M.L. Meli, Feline infectious peritonitis: still an enigma?, Vet Pathol 51(2) (2014) 505-26. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Coggins, J.M. Norris, R. Malik, M. Govendir, E.J. Hall, B. Kimble, M.F. Thompson, Outcomes of treatment of cats with feline infectious peritonitis using parenterally administered remdesivir, with or without transition to orally administered GS-441524, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine (2023). [CrossRef]

- A. Sweet, N. Andre, G. Whittaker, RNA in-situ hybridization for pathology-based diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP): current diagnostics for FIP and comparison to the current gold standard, Qeios (2022). [CrossRef]

- C.W. Olsen, W.V. Corapi, C.K. Ngichabe, J.D. Baines, F.W. Scott, Monoclonal antibodies to the spike protein of feline infectious peritonitis virus mediate antibody-dependent enhancement of infection of feline macrophages, Journal of virology 66(2) (1992) 956-965. [CrossRef]

- N.C. Pedersen, An overview of feline enteric coronavirus and infectious peritonitis virus infections, Feline Practice 23 (1995) 7-20.

- T. Hayashi, K. Doi, K. Fujiwara, Role of circulating antibodies and thymus-dependent lymphocytes in production of effusive type feline infectious peritonitis after oral infection, Molecular biology and pathogenesis of coronaviruses (1984) 383-384. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, Z. Wen, G. Zhong, H. Yang, C. Wang, B. Huang, R. Liu, X. He, L. Shuai, Z. Sun, Y. Zhao, P. Liu, L. Liang, P. Cui, J. Wang, X. Zhang, Y. Guan, W. Tan, G. Wu, H. Chen, Z. Bu, Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2, Science 368(6494) (2020) 1016-1020. [CrossRef]

- T.H.C. Sit, C.J. Brackman, S.M. Ip, K.W.S. Tam, P.Y.T. Law, E.M.W. To, V.Y.T. Yu, L.D. Sims, D.N.C. Tsang, D.K.W. Chu, R. Perera, L.L.M. Poon, M. Peiris, Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2, Nature 586(7831) (2020) 776-778. [CrossRef]

- M. Buonocore, C. Marino, M. Grimaldi, A. Santoro, M. Firoznezhad, O. Paciello, F. Prisco, A.M. D'Ursi, New putative animal reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2 in Italian fauna: A bioinformatic approach, Heliyon 6(11) (2020) e05430. [CrossRef]

- S.J. O'Brien, N. Yuhki, Comparative genome organization of the major histocompatibility complex: lessons from the Felidae, Immunological Reviews 167(1) (1999) 133-144. [CrossRef]

- R.P. Sutmuller, R. Offringa, C.J. Melief, Revival of the regulatory T cell: new targets for drug development, Drug Discov Today 9(7) (2004) 310-6. [CrossRef]

- B.M. Gonzales-Portillo, J.Y. Lee, A.A. Vandenbark, H. Offner, C.V. Borlongan, Major histocompatibility complex Class II-based therapy for stroke, Brain Circ 7(1) (2021) 37-40. [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Lee, V. Castelli, B. Bonsack, A.B. Coats, L. Navarro-Torres, J. Garcia-Sanchez, C. Kingsbury, H. Nguyen, A.A. Vandenbark, R. Meza-Romero, H. Offner, C.V. Borlongan, A Novel Partial MHC Class II Construct, DRmQ, Inhibits Central and Peripheral Inflammatory Responses to Promote Neuroprotection in Experimental Stroke, Transl Stroke Res 11(4) (2020) 831-836. [CrossRef]

- J. Brown, C. Kingsbury, J.Y. Lee, A.A. Vandenbark, R. Meza-Romero, H. Offner, C.V. Borlongan, Spleen participation in partial MHC class II construct neuroprotection in stroke, CNS Neurosci Ther 26(7) (2020) 663-669. [CrossRef]

- G. Benedek, A.A. Vandenbark, N.J. Alkayed, H. Offner, Partial MHC class II constructs as novel immunomodulatory therapy for stroke, Neurochemistry international 107 (2017) 138-147. [CrossRef]

- G. Benedek, W. Zhu, N. Libal, A. Casper, X. Yu, R. Meza-Romero, A.A. Vandenbark, N.J. Alkayed, H. Offner, A novel HLA-DRα1-MOG-35-55 construct treats experimental stroke, Metabolic brain disease 29 (2014) 37-45. [CrossRef]

- P. Correale, L. Mutti, F. Pentimalli, G. Baglio, R.E. Saladino, P. Sileri, A. Giordano, HLA-B*44 and C*01 Prevalence Correlates with Covid19 Spreading across Italy, Int J Mol Sci 21(15) (2020). [CrossRef]

- R. Liang, Y. Sun, Y. Liu, J. Wang, Y. Wu, Z. Li, L. Ma, N. Zhang, L. Zhang, X. Wei, Z. Qu, N. Zhang, C. Xia, Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I (FLA-E*01801) Molecular Structure in Domestic Cats Demonstrates Species-Specific Characteristics in Presenting Viral Antigen Peptides, J Virol 92(6) (2018). [CrossRef]

- T.W. Beck, J. Menninger, W.J. Murphy, W.G. Nash, S.J. O'Brien, N. Yuhki, The feline major histocompatibility complex is rearranged by an inversion with a breakpoint in the distal class I region, Immunogenetics 56(10) (2005) 702-709. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Holmes, S.G. Holmer, P. Ross, A.S. Buntzman, J.A. Frelinger, P.R. Hess, Polymorphisms and tissue expression of the feline leukocyte antigen class I loci FLAI-E, FLAI-H, and FLAI-K, Immunogenetics 65(9) (2013) 675-89. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Aranyos, S.R. Roff, R. Pu, J.L. Owen, J.K. Coleman, J.K. Yamamoto, An initial examination of the potential role of T-cell immunity in protection against feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection, Vaccine 34(12) (2016) 1480-8. [CrossRef]

- M. Omori, R. Pu, T. Tanabe, W. Hou, J. Coleman, M. Arai, J. Yamamoto, Cellular immune responses to feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) induced by dual-subtype FIV vaccine, Vaccine 23(3) (2004) 386-398. [CrossRef]

- R. Pu, M. Omori, S. Okada, S.L. Rine, B.A. Lewis, E. Lipton, J.K. Yamamoto, MHC-restricted protection of cats against FIV infection by adoptive transfer of immune cells from FIV-vaccinated donors, Cell Immunol 198(1) (1999) 30-43. [CrossRef]

- B. Reynisson, B. Alvarez, S. Paul, B. Peters, M. Nielsen, NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data, Nucleic Acids Res 48(W1) (2020) W449-W454. [CrossRef]

- C. UniProt, UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023, Nucleic Acids Res 51(D1) (2023) D523-D531. [CrossRef]

- H.G. Rammensee, Chemistry of peptides associated with MHC class I and class II molecules, Curr Opin Immunol 7(1) (1995) 85-96. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhou, B. Jin, H. Li, S.Y. Huang, HPEPDOCK: a web server for blind peptide-protein docking based on a hierarchical algorithm, Nucleic Acids Res 46(W1) (2018) W443-W450. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, M.F. Sanner, AutoDock CrankPep: combining folding and docking to predict protein-peptide complexes, Bioinformatics 35(24) (2019) 5121-5127. [CrossRef]

- R.N. Kirchdoerfer, A.B. Ward, Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors, Nat Commun 10(1) (2019) 2342. [CrossRef]

- J. Jumper, R. Evans, A. Pritzel, T. Green, M. Figurnov, O. Ronneberger, K. Tunyasuvunakool, R. Bates, A. Zidek, A. Potapenko, A. Bridgland, C. Meyer, S.A.A. Kohl, A.J. Ballard, A. Cowie, B. Romera-Paredes, S. Nikolov, R. Jain, J. Adler, T. Back, S. Petersen, D. Reiman, E. Clancy, M. Zielinski, M. Steinegger, M. Pacholska, T. Berghammer, S. Bodenstein, D. Silver, O. Vinyals, A.W. Senior, K. Kavukcuoglu, P. Kohli, D. Hassabis, Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold, Nature 596(7873) (2021) 583-589. [CrossRef]

- M. Mirdita, K. Schütze, Y. Moriwaki, L. Heo, S. Ovchinnikov, M. Steinegger, ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all, Nature methods 19(6) (2022) 679-682. [CrossRef]

- K. Wang, Z. Jia, L. Bao, L. Wang, L. Cao, H. Chi, Y. Hu, Q. Li, Y. Zhou, Y. Jiang, Q. Zhu, Y. Deng, P. Liu, N. Wang, L. Wang, M. Liu, Y. Li, B. Zhu, K. Fan, W. Fu, P. Yang, X. Pei, Z. Cui, L. Qin, P. Ge, J. Wu, S. Liu, Y. Chen, W. Huang, Q. Wang, C.F. Qin, Y. Wang, C. Qin, X. Wang, Memory B cell repertoire from triple vaccinees against diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants, Nature 603(7903) (2022) 919-925. [CrossRef]

- S. Di Micco, R. Rahimova, M. Sala, M.C. Scala, G. Vivenzio, S. Musella, G. Andrei, K. Remans, L. Mammri, R. Snoeck, G. Bifulco, F. Di Matteo, V. Vestuto, P. Campiglia, J.A. Marquez, A. Fasano, Rational design of the zonulin inhibitor AT1001 derivatives as potential anti SARS-CoV-2, Eur J Med Chem 244 (2022) 114857. [CrossRef]

- S. Weingarten-Gabbay, S. Klaeger, S. Sarkizova, L.R. Pearlman, D.Y. Chen, K.M.E. Gallagher, M.R. Bauer, H.B. Taylor, W.A. Dunn, C. Tarr, J. Sidney, S. Rachimi, H.L. Conway, K. Katsis, Y. Wang, D. Leistritz-Edwards, M.R. Durkin, C.H. Tomkins-Tinch, Y. Finkel, A. Nachshon, M. Gentili, K.D. Rivera, I.P. Carulli, V.A. Chea, A. Chandrashekar, C.C. Bozkus, M. Carrington, M.C.-. Collection, T. Processing, N. Bhardwaj, D.H. Barouch, A. Sette, M.V. Maus, C.M. Rice, K.R. Clauser, D.B. Keskin, D.C. Pregibon, N. Hacohen, S.A. Carr, J.G. Abelin, M. Saeed, P.C. Sabeti, Profiling SARS-CoV-2 HLA-I peptidome reveals T cell epitopes from out-of-frame ORFs, Cell 184(15) (2021) 3962-3980 e17. [CrossRef]

- A. Tarke, C.H. Coelho, Z. Zhang, J.M. Dan, E.D. Yu, N. Methot, N.I. Bloom, B. Goodwin, E. Phillips, S. Mallal, J. Sidney, G. Filaci, D. Weiskopf, R. da Silva Antunes, S. Crotty, A. Grifoni, A. Sette, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination induces immunological T cell memory able to cross-recognize variants from Alpha to Omicron, Cell 185(5) (2022) 847-859 e11. [CrossRef]

- P. Gattinger, K. Niespodziana, K. Stiasny, S. Sahanic, I. Tulaeva, K. Borochova, Y. Dorofeeva, T. Schlederer, T. Sonnweber, G. Hofer, R. Kiss, B. Kratzer, D. Trapin, P.A. Tauber, A. Rottal, U. Kormoczi, M. Feichter, M. Weber, M. Focke-Tejkl, J. Loffler-Ragg, B. Muhl, A. Kropfmuller, W. Keller, F. Stolz, R. Henning, I. Tancevski, E. Puchhammer-Stockl, W.F. Pickl, R. Valenta, Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 requires antibodies against conformational receptor-binding domain epitopes, Allergy 77(1) (2022) 230-242. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, S. Qiao, J. Yu, J. Zeng, S. Shan, L. Tian, J. Lan, L. Zhang, X. Wang, Bat and pangolin coronavirus spike glycoprotein structures provide insights into SARS-CoV-2 evolution, Nat Commun 12(1) (2021) 1607. [CrossRef]

- M.C. Horzinek, H. Lutz, N. Pedersen, Antigenic relationships among homologous structural polypeptides of porcine, feline, and canine coronaviruses, Infection and Immunity 37(3) (1982) 1148-1155. [CrossRef]

- L. Schrödinger, Schrödinger Release 2023-2: Maestro, New York, NY, 2023.

- S.F. Altschul, W. Gish, W. Miller, E.W. Myers, D.J. Lipman, Basic local alignment search tool, J Mol Biol 215(3) (1990) 403-10. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Abraham, T. Murtola, R. Schulz, S. Páll, J.C. Smith, B. Hess, E. Lindahl, GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers, SoftwareX 1 (2015) 19-25. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang, A.D. MacKerell Jr, CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data, Journal of computational chemistry 34(25) (2013) 2135-2145. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).