Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

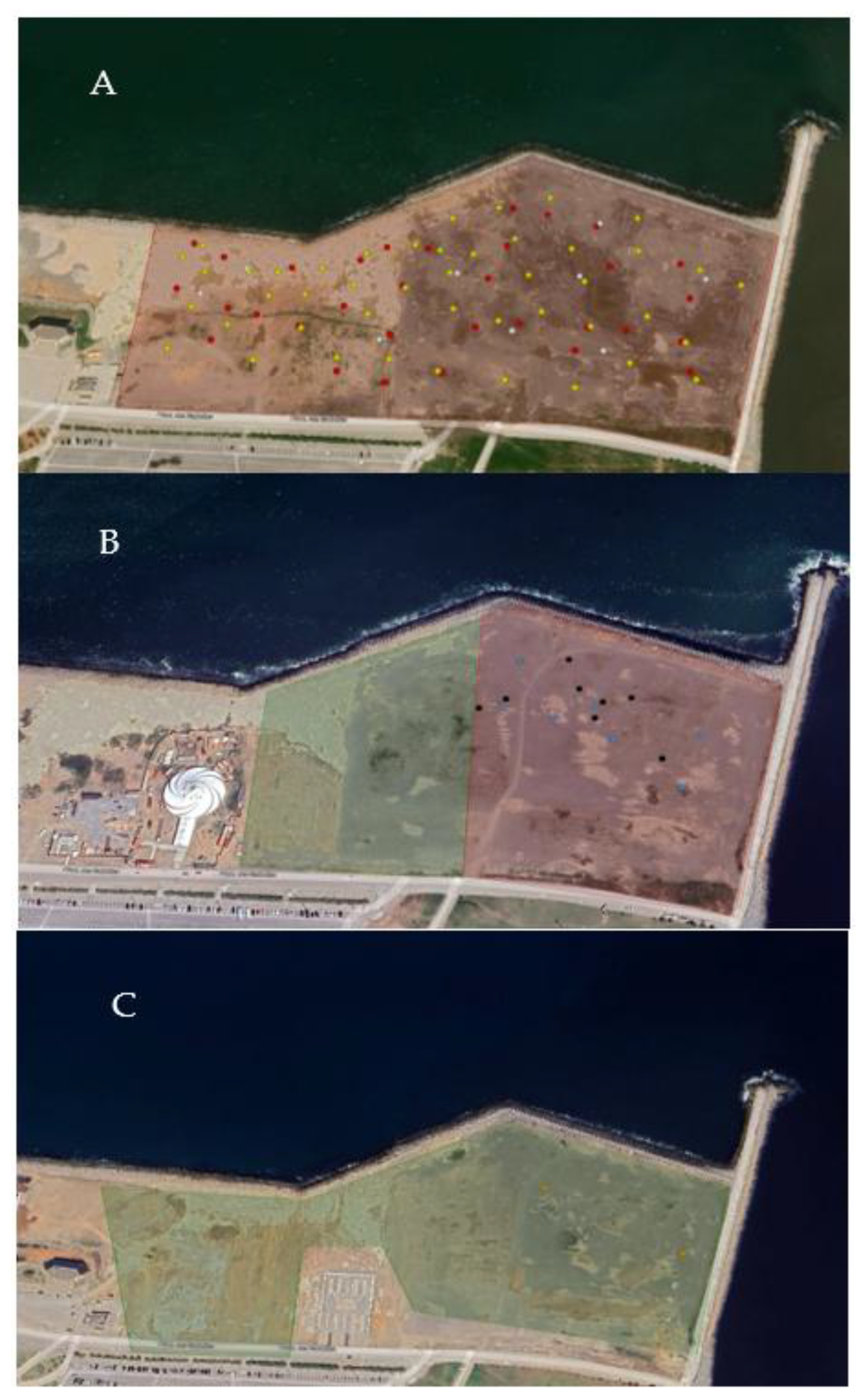

Ground-nesting shorebirds face growing pressure from recreational activities in coastal urban areas. We monitored the breeding success of Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) and Little Ringed Plover (Charadrius dubius) over six consecutive years (2020–2025) at the Promenade of Sablettes, a heavily visited waterfront in Algiers, Algeria. We combined field surveys with multi-sensor remote sensing analysis using Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Dynamic World data to quantify habitat change. A total of 105 nests were recorded across both species. Breeding success reached 70% during the COVID-19 lockdown period (2020–2021), when human visitation dropped sharply. In contrast, complete reproductive failure occurred in 2022 and 2023, coinciding with resumed tourism and unplanned construction activities. Remote sensing revealed that 80–85% of the study area experienced severe habitat degradation between 2020 and 2025, while suitable refuge zones shrank to less than 10% of the total surface. Fledged chicks consistently moved toward a less disturbed vegetated zone, highlighting its functional importance for brood survival. Our results show that human disturbance, rather than intrinsic habitat quality, is the main factor limiting breeding success at this site. When disturbance was reduced during the pandemic, the habitat proved fully functional for both species. These findings suggest that simple management measures such as seasonal access restrictions and symbolic fencing during the April–July breeding period could restore breeding conditions without major habitat engineering. This study provides one of the first integrations of long-term field breeding data with landscape-scale remote sensing to document the effects of the anthropause and subsequent recovery on urban shorebird populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Anthropogenic Pressure

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Remote Sensing

2.4.1. Description Parameters

2.4.2. Remote-Sensing Data

2.4.3. Preprocessing and Composites

2.4.4. Indices and Rationale

2.4.5. Change Detection and Normalization

2.4.6. Composite Habitat Change index

2.4.7. Outputs, Reproducibility and Caveats

2.4.8. Limitations (Overall)

3. Results

3.1. Nest Density and Effort

3.2. Spatial Patterns of Habitat Change (2020-2025)

4. Discussion

Temporal Correlation with Breeding Outcomes

Prospects of Conservation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KP | Kentish Plover |

| LPR | Little Ringed Plover |

References

- Aarif, K.M.; Kaiser, S.A.; Nefla, A.; Almaroofi, S. Over-summering abundance, species composition, and habitat use patterns at a globally important site for migratory shorebirds. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2020, 132, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldareri, F.; Sulli, A.; Parrino, N.; Dardanelli, G.; Todaro, S.; Maltese, A. On the shoreline monitoring via earth observation: An isoradiometric method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Piczak, M.L.; Singh, N.J.; Åkesson, S.; Ford, A.T.; Chowdhury, S.; Lennox, R.J. Animal migration in the Anthropocene: threats and mitigation options. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1242–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramp, S.; Simmons, K.E.L.; Brooks, D.C.; Collar, N.J.; Dunn, E.; Gillmor, R.; Hollom, P.A.D.; Hudson, R.; Nicholson, E.M.; Ogilvie, M.A.; Olney, P.J.S.; Roselaar, C.S.; Voous, K.H.; Wallace, D.I.M.; Wattel, J.; Wilson, M.G. Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Birds of the Western Palearctic: 3. Waders to Gulls; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1983; p. 913p. [Google Scholar]

- Darrah, A.J.; Cohen, J.B.; Castelli, P.M. A decision support tool to guide the use of nest exclosures for Piping Plover conservation. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2020, 44, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemadi, I.; Draidi, K.; Bakhouche, B. Recent established population of tree sparrow in Algeria: palms contributed actively to increasing breeding pairs. Ornithol. Res. 2024, 32, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draidi, K.; Djemadi, I.; Bakhouche, B. A multi-year survey on aquatic avifauna consolidates the eligibility of a small significant peri-urban wetland in northeast Algeria (Boussedra marsh) to be included on the Important Bird Areas network. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 31, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yu, X. Spatial and temporal changes in shorebird habitats under different land use scenarios along the Yellow and Bohai Sea coasts in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautschi, D.; Čulina, A.; Heinsohn, R.; Stojanovic, D.; Crates, R. Protecting wild bird nests against predators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of non-lethal methods. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 61, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Serrano, M.Á. Four-legged foes: dogs disturb nesting plovers more than people do on tourist beaches. Ibis 2021, 163, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Serrano, M.Á.; López-López, P. Deceiving predators: linking distraction behavior with nest survival in a ground-nesting bird. Behav. Ecol. 2017, 28, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.V.; Mott, R.; Delean, S.; Hunt, B.J.; Brookes, J.D.; Cassey, P.; Prowse, T.A. Shorebird habitat selection and foraging behaviour have important implications for management at an internationally important non-breeding wetland. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2024, 5, e12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, V.; Sandercock, B.K.; Székely, T.; Freckleton, R.P. Animal migration to northern latitudes: environmental changes and increasing threats. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 37, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, K.D. Birds at a Southern California beach: seasonality, habitat use and disturbance by human activity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2001, 10, 1949–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, S.J.; Yoon, H.N.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, H.J. Casual birding gone wrong: A case study on the impact of human disturbance on breeding sites of the Kentish plover (Anarhynchus alexandrinus). Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 33, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasinghe, S.; Simpson, G.D.; Newsome, D.; Perera, P. Scoping recreational disturbance of shorebirds to inform the agenda for research and management in Tropical Asia. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2020, 31, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maul, G.A.; Duedall, I.W. Demography of coastal populations. In Encyclopedia of Coastal Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 692–700. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, G.C.; Bede-Fazekas, Á.; Ivanov, A.; Crecco, L.; Székely, T.; Kosztolányi, A. Landscape and climatic predictors of Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) distributions throughout Kazakhstan. Ibis 2022, 164, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation: the impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. Bioscience 2002, 52, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meager, J.J.; Schlacher, T.A.; Nielsen, T. Humans alter habitat selection of birds on ocean-exposed sandy beaches. Divers. Distrib. 2012, 18, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.G.; Gill, R.E., Jr.; Harrington, B.A.; Skagen, S.K.; Page, G.W.; Gratto-Trevor, C.L.; Haig, S.M. Estimates of shorebird populations in North America; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, R.I.G.; Ross, R.K.; Niles, L.J.; Gates, H.R.; Peck, M.K.; Gratto-Trevor, C.L.; Koch, S.L.; Pashley, D.N.; Porter, R.R. Dramatic Declines of Semipalmated Sandpipers on Their Major Wintering Areas in the Guianas, Northern South America. Waterbirds 2012, 35, 120–134. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41432480. [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.; Vargas, J.; Fernández, G.; Reiter, M.E. Impact of human disturbance on the abundance of non-breeding shorebirds in a subtropical wetland. Biotropica 2022, 54, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.G.; Gibson, D.; Alexander, C.R.; Farmer, A.; Jannsen, J.A.M.; Catlin, D.H. Piping plover chick ecology following landscape-level disturbance. J. Wildl. Manag. 2023, 87, e22325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.G.; Black, K.M.; Catlin, D.H.; Wails, C.N.; Karpanty, S.M.; Bellman, H.; Fraser, J.D. Red fox trap success is correlated with piping plover chick survival. J. Wildl. Manag. 2024, 88, e22538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, C.; Loretto, M.C.; Bates, A.E.; Davidson, S.C.; Duarte, C.M.; Jetz, W.; Johnson, M.; Kato, A.; Kays, R.; Mueller, T.; Primack, R.B.; Ropert-Coudert, Y.; Tucker, M.A.; Wikelski, M.; Cagnacci, F. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 1156–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlacher, T.A.; Narayanaswamy, B.E.; Weston, M.A. Spatial Mismatch Between Tourism Hotspots and Anthropogenic Debris on Sandy Beaches in an Iconic Conservation Area. Estuaries Coasts 2025, 48, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlacher, T.A.; Weston, M.A.; Orchard, S.; Kelaher, B.P.; Maslo, B.; Dugan, J.E.; Wiegand, A.N. Adverse impacts of off-road vehicles on coastal dune vegetation are widespread, substantial, and long-lasting: Evidence from a global meta-analysis of sandy beach-dune systems. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 312, 109038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, S.A.; Simons, T.R. Factors affecting the reproductive success of American Oystercatchers Haematopus palliatus on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Mar. Ornithol. 2015, 43, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.A.; Smith, A.C.; Andres, B.; Francis, C.M.; Harrington, B.; Friis, C.; Brown, S. Accelerating declines of North America's shorebirds signal the need for urgent conservation action. Ornithol. Appl. 2023, 125, duad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stantial, M.L.; Cohen, J.B.; Darrah, A.J.; Maslo, B. Predator exclosures increase nest success but reduce adult survival and increase dispersal distance of Piping Plovers, indicating exclosures should be used with caution. Ornithol. Appl. 2024, 126, duad047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigner, M.G.; Beyer, H.L.; Klein, C.J.; Fuller, R.A. Reconciling recreational use and conservation values in a coastal protected area. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, T. Why study plovers? The significance of non-model organisms in avian ecology, behaviour and evolution. J. Ornithol. 2019, 160, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Abundance and Productivity Estimates—2021 Update Atlantic Coast Piping Plover Population. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/media/abundance-and-productivity-estimates-2021-update-atlantic-coast-piping-plover-population (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- VanDusen, B.M.; Fegley, S.R.; Peterson, C.H. Prey Distribution, Physical Habitat Features, and Guild Traits Interact to Produce Contrasting Shorebird Assemblages among Foraging Patches. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Melville, W.; Lei, F.; Lu, W.; Yin, Y.; Cheng, L. Impacts of habitat loss on migratory shorebird populations and communities at stopover sites in the Yellow Sea. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 269, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, M.A.; Ju, Y.K.; Guay, P.J.; Naismith, C. A test of the "Leave Early and Avoid Detection" (LEAD) hypothesis for passive nest defenders. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2018, 130, 1011–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Duan, H.; Yu, X. Land use-driven shifts in shorebird habitat connectivity along the Yellow and Bohai Sea coasts: Dynamics and scenario predictions. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 300, 110462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | KP nest | KP Success | LRP nest | LRP Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 15 | 10 | 18 | 12 |

| 2021 | 22 | 15 | 24 | 18 |

| 2022 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 2023 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2024 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 2025 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).