Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Powder Metallurgy Processing

2.3. Shot Peening Treatment

2.4. Surface and Metallographic Characterization

2.5. Corrosion Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Topography Assessment

3.2. Microstructural Evaluation

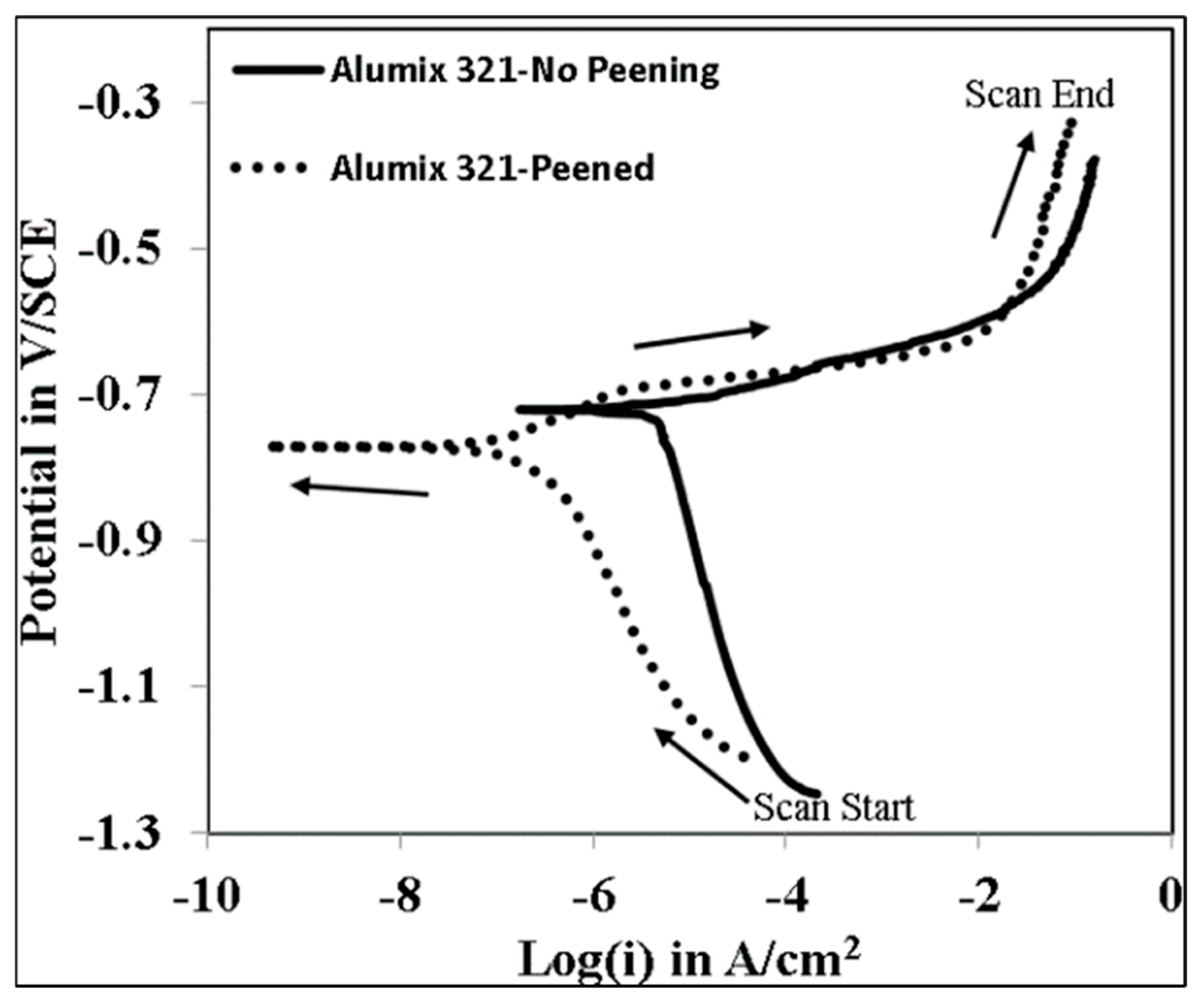

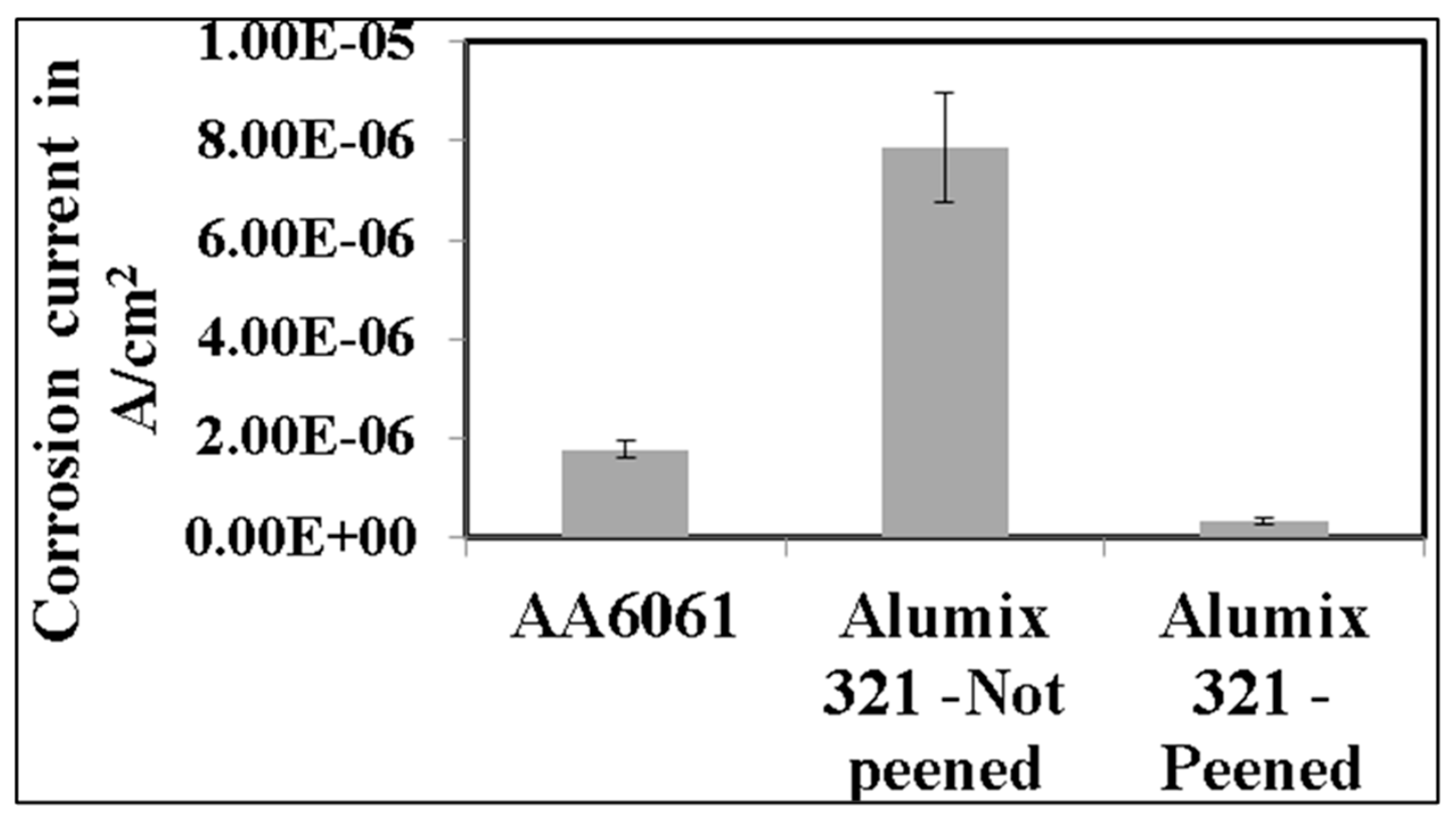

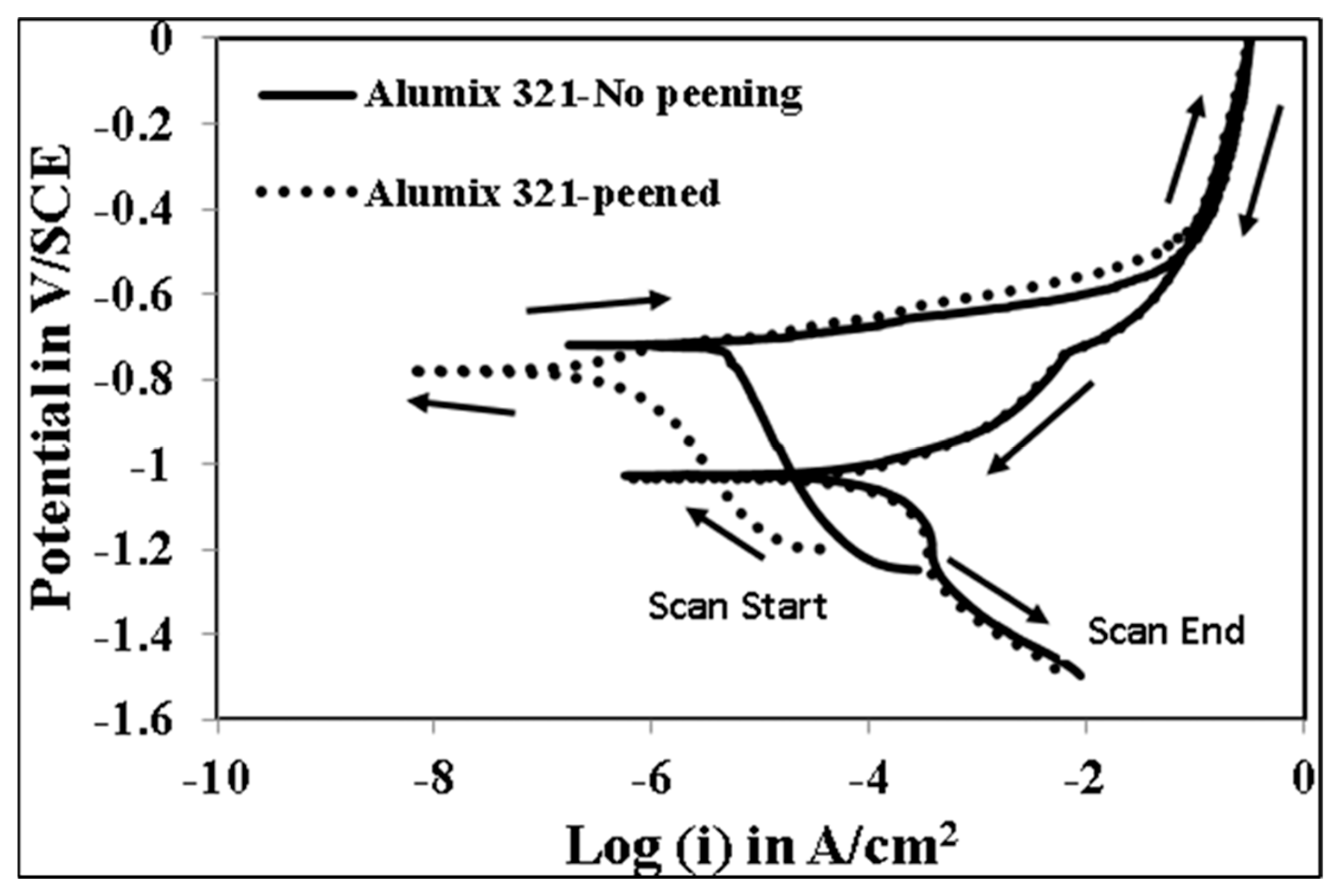

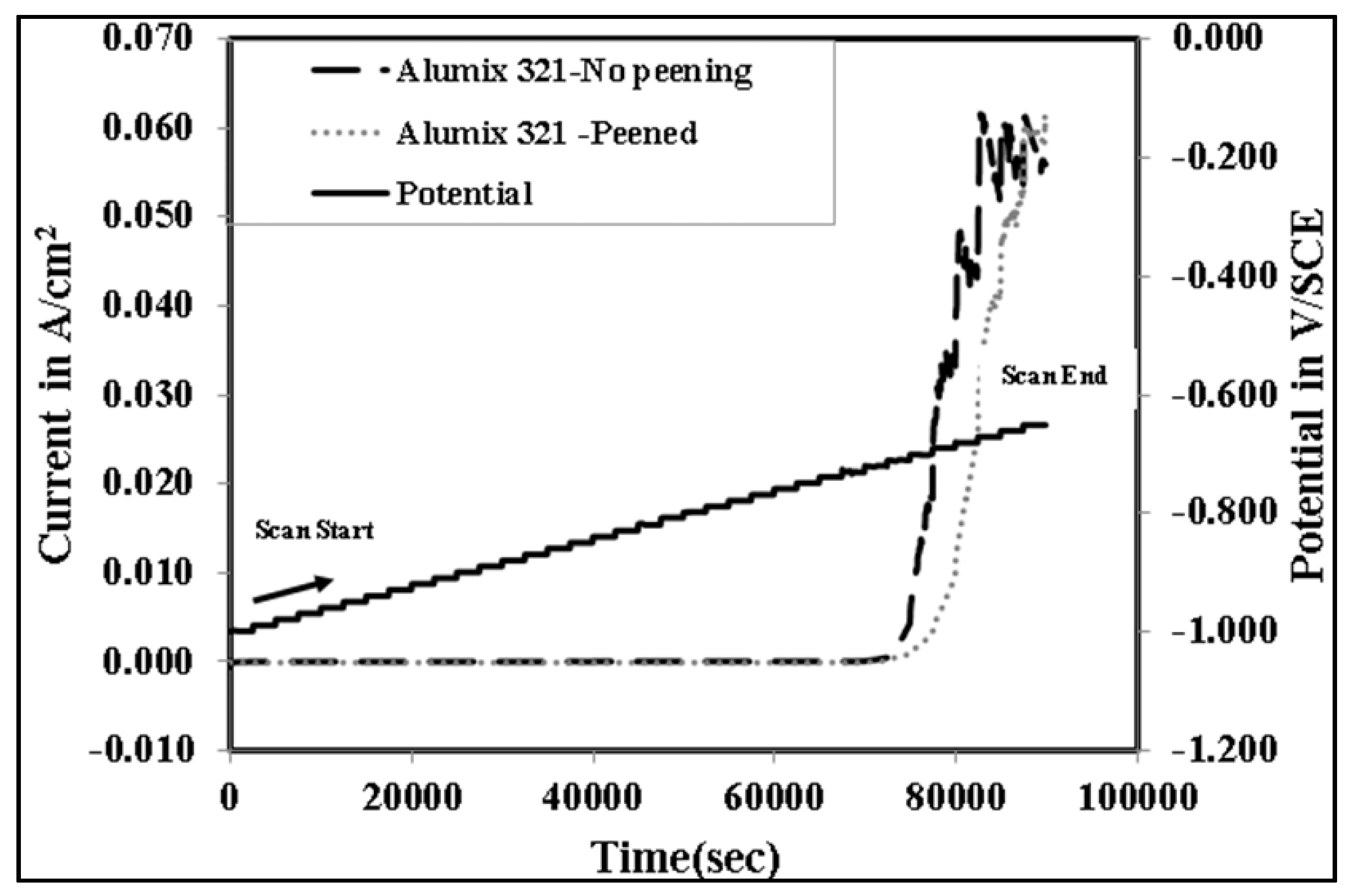

3.3. Electrochemical Behaviour

3.4. Characterization of the Corroded Samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, H.; Zhao, F.; Ma, D.; Zhao, X.; Meng, J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, F. An Improved Process for Solving the Sintering Problem of Al-Si Alloy Powder Metallurgy. Metals 2024, 14(11), 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveez, B.; Jamal, N. A.; Anuar, H.; Ahmad, Y.; Aabid, A.; Baig, M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of metal foams fabricated via melt foaming and powder metallurgy technique: a review. Materials 2022, 15(15), 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edosa, O. O.; Tekweme, F. K.; Gupta, K. A review on the influence of process parameters on powder metallurgy parts. Engineering and Applied Science Research 2022, 49(3), 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Nassef, A.; El-Garaihy, W. H.; El-Hadek, M. Characteristics of cold and hot pressed iron aluminum powder metallurgical alloys. Metals 2017, 7(5), 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, Z.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, W. Microstructure and tensile properties of aluminum powder metallurgy alloy prepared by a novel low-pressure sintering. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 14, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wu, L.; Yan, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, W. Microstructure and mechanical properties of powder metallurgy 2024 aluminum alloy during cold rolling. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 15, 3337–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, G. A.; Amirkhiz, B. S.; Williams, B. W.; Taylor, A.; Hexemer, R. L.; Donaldson, I. W.; Bishop, D. P. Microstructural evolution of a forged 2XXX series aluminum powder metallurgy alloy. Materials Characterization 2019, 151, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, M. D.; Donaldson, I. W.; Hexemer Junior, R. L.; Bishop, D. P. Effects of post-sinter processing on an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu powder metallurgy alloy. Metals 2017, 7(9), 370. [Google Scholar]

- Tünçay, M. M.; Muñiz-Lerma, J. A.; Bishop, D. P.; Brochu, M. Spark plasma sintering and spark plasma upsetting of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2017, 704, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Monchoux, J. P.; Couret, A.; Durand, L.; Voisin, T.; Trzaska, Z.; Thomas, M. Elaboration of metallic materials by SPS: processing, microstructures, properties, and shaping. Metals 2021, 11(2), 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. F.; Donaldson, I. W.; Bishop, D. P. Sinter-swage processing of an Al-Si-Mg-Cu powder metallurgy alloy. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly 2022, 61(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipouros, G. J.; Caley, W. F.; Bishop, D. P. On the advantages of using powder metallurgy in new light metal alloy design. Metall Mater Trans B 2006, 37(12), 3429–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, E.; Samal, P. K. Powder Metallurgy Stainless Steels: Processing, Microstructures, and Properties; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, W.; Kipouros, G. Powder Metallurgy Aluminum Alloys: Structure and Porosity. In Encyclopedia of Aluminum and Its Alloys; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: New York, 2018; pp. 1977–1995. [Google Scholar]

- Steedman, G.; Bishop, D. P.; Caley, W. F.; Kipouros, G. J. Surface porosity investigation of aluminum–silicon PM alloys. Powder technology 2012, 226, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizade, N.; Jarjoura, G.; Kipouros, G. J.; Plucknett, K.; Shakerin, S.; Mohammadi, M. Microstructure, hardness, and tribological properties of AA2014 powder metallurgy alloys: A sizing mechanical surface treatment study. Engineering Failure Analysis 2025, 174, 109550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, H. M.; Elkady, O. A.; Reda, Y.; Ashraf, K. E. Electrochemical surface modification of aluminum sheets prepared by powder metallurgy and casting techniques for printed circuit applications. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 2019, 72, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žagar, S.; Markoli, B.; Naglič, I.; Šturm, R. The Influence of Age hardening and shot peening on the surface properties of 7075 aluminium alloy. Materials 2021, 14(9), 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambor, M.; Trško, L.; Klusák, J.; Fintová, S.; Kajánek, D.; Nový, F.; Bokůvka, O. Effect of severe shot peening on the very-high cycle notch fatigue of an AW 7075 alloy. Metals 2020, 10(9), 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravnikar, D.; Šturm, R.; Žagar, S. Effect of shot peening on the strength and corrosion properties of 6082-T651 aluminium alloy. Materials 2023, 16(14), 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupanc, U.; Grum, J. Effect of pitting corrosion on fatigue performance of shot-peened aluminum alloy 7075-T651. J. Matter. Process. Technol. 2010, 210(9), 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R. M. Powder Metallurgy Science, 2nd ed.; Metal powder industrial federation, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O. Lynen; Eksi, A.; Bircan, D.; Dilek, M. The effects of sintering and shot peening processes on the fatigue strength. MaterialWiss Werkest 2010, 41(4), 202–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Han, Q.; Xu, R.; Zhao, K.; Li, J. Localized corrosion behaviour of AA7150 after ultrasonic shot peening: Corrosion depth vs. impact energy. Corros.Sci 2018, 130, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Vaibhav; Singh, J. K.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Santhi Srinivas, NC; Singh, Vakil. Influence of ultrasonic shot peening on corrosion behavior of 7075 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 723, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Hao; Niu, Jintao; Xing, Xiangtao; Lin, Qichao; Chen, Hongtang; Qiao, Yang. Effects of the Shot Peening Process on Corrosion Resistance of Aluminum Alloy: A Review. Coatings 2022, 12(5), 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trdan, Uroš; Grum, Janez. SEM/EDS characterization of laser shock peening effect on localized corrosion of Al alloy in a near natural chloride environment. Corros.Sci 2014, 82, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Bishop, D. P.; Kipouros, G. J. Sinterability and characterization of commercial aluminum powder metallurgy alloy Alumix 321. Powder Technology 2015, 279, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martı́n, M.; Castro, F. Liquid phase sintering of P/M aluminum alloys: Effect of processing conditions. J. Matter. Process. Technol. 2003, 143–144(0), 814–821. [Google Scholar]

- Youseffi, M. Sintering and mechanical properties of prealloyed 6061 Al powder with and without common lubricants and sintering aids. Powder Metall. 2006, 49(1), 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.; Wilfried, T. Y. A.; Gao, T.; Xue, H. Effects of shot peening with different coverage on surface integrity and fatigue crack growth properties of 7B50-T7751 aluminum alloy. Engineering Failure Analysis 2022, 133, 106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, I.; Sís, J.; Mikulova, D. Short fatigue crack growth in an aircraft Al-alloy of a 7075 type after shot peening. Surface and Coatings Technology 2014, 243, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Hang, B.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Ni, M; Lu, C. Surface nanocrystallization induced by shot peening and its effect on corrosion resistance of 6061 aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. 2014, 29(24), 3002–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, M.; Donaldson, I.; Hexemer, R.; Gharghouri, M.; Bishop, D. Characterization of the microstructure, mechanical properties, and shot peening response of an industrially processed Al–Zn–Mg–Cu PM alloy. J. Matter. Process. Technol. 2015, 221, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodič, P.; Milošev, I.; Frankel, G. S. Corrosion of Synthetic Intermetallic Compounds and AA7075-T6 in Dilute Harrison’s Solution and Inhibition by Cerium (III) Salts. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2023, 170(3), 031503. [Google Scholar]

- Seah, K. H.; Thampuran, R.; Teoh, S. H. The influence of pore morphology on corrosion. Corros. Sci. 1998, 40(4), 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, B. Effects of pH and chloride concentration on pitting corrosion of AA6061 aluminum alloy. Corros.Sci 2008, 50(7), 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylor, D. M.; Patrick, P.J. Pitting corrosion behavior of 6061 aluminum alloy foils in sea water. J.Electrochem. Soc. 1986, 133(5), 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z. A review of corrosion and pitting resistance of Al 6061 and 6013 silicon carbide composites in neutral salt solution and seawater. Corros. Rev. 2001, 19(2), 119–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltz, J. D. S.; Beltrami, L. V. R.; Kunst, S. R.; Brandolt, C.; Malfatti, C. D. F. Effect of the shot peening process on the corrosion and oxidation resistance of AISI430 stainless steel. Materials Research 2015, 18, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C. Q.; Zhong, Q. D.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Y. F.; Li, Y. L. Investigating crevice corrosion behavior of 6061 Al alloy using wire beam electrode. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 14, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Mg | Si | Cu | Fe | Bi | Sn | V | Al |

| Wt-% | 1.31 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | Bal |

| Corrosion parameter | OCP (V.vs.SCE) | Ecorr (V vs.SCE) |

Epit (V vs.SCE) |

Epit -SSP (V vs.SCE) |

Corrosion Current | Corrosion rate (mmpy) |

| Alloy | density (A.cm-2) |

|||||

| AA6061 | -0.736± 0.004 |

-0.714± 0.003 |

-0.714± 0.003 |

------- | 1.77X10-06 | 0.019 |

| Alumix 321 (un-peened) |

-0.753± 0.005 |

-0.719± 0.016 |

-0.714± 0.004 |

-0.711±0.05 | 7.86 X10-06 | 0.079 |

| Alumix 321 (shot peened) |

-0.769± 0.020 |

-0.762± 0.025 |

-0.716± 0.011 |

-0.690±0.03 | 3.20 X10-07 | 0.004 |

| Material | Rs Ω cm2 |

Rpo Ω cm2 |

CPE | Rct Ω cm2 |

CPE | ||||

| Ypo μsnΩ−1cm-2 |

n | Yct | n | W μsnΩ−1cm−2 |

|||||

| Alumix 321 PM Unpeened | 6.92 | 6830 | 24.42 | 0.901 | 9754 | 281.3 | 0.991 | 7.46 | |

| Alumix 321 PM Shot peened | 7.98 | 1311 |

155.8 | 0.757 | 12400 | 101.1 | 0.746 | 264.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).