Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction—From Inflammation Control to Immune Reprogramming

2. The Immune Tolerance Network in Rheumatology

2.1. Architecture of Immune Tolerance

2.2. Cellular Architecture of Immune Tolerance

2.2.1. T-Cell Regulatory Circuitry

2.2.2. B-Cell Tolerance and Autoantibody Memory

2.2.3. Antigen-Presenting Cells and Myeloid Gatekeepers

2.2.4. Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes and Stromal Integration

2.3. Breakdown of Tolerance Across Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

3. Epigenetic Remodeling in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

3.1. DNA Methylation Dynamics and Regulatory Drift

3.2. Histone Modifications and Chromatin Accessibility

3.3. Three-Dimensional Genome Reorganization

3.4. Epigenetic–Metabolic Coupling as a Tolerance Axis

3.5. Therapeutic Implications: Toward Epigenetic Reprogramming of Tolerance

4. Metabolic Reprogramming and Immune Cell Fate

4.1. Metabolic Determinants of Immune Activation and Regulation

4.2. Glycolytic and Mitochondrial Rewiring in Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease

4.3. Metabolite Signaling and Immunoregulation

4.4. Therapeutic Metabolic Reprogramming

4.5. Systems Perspective: Energetic Homeostasis as a Determinant of Tolerance

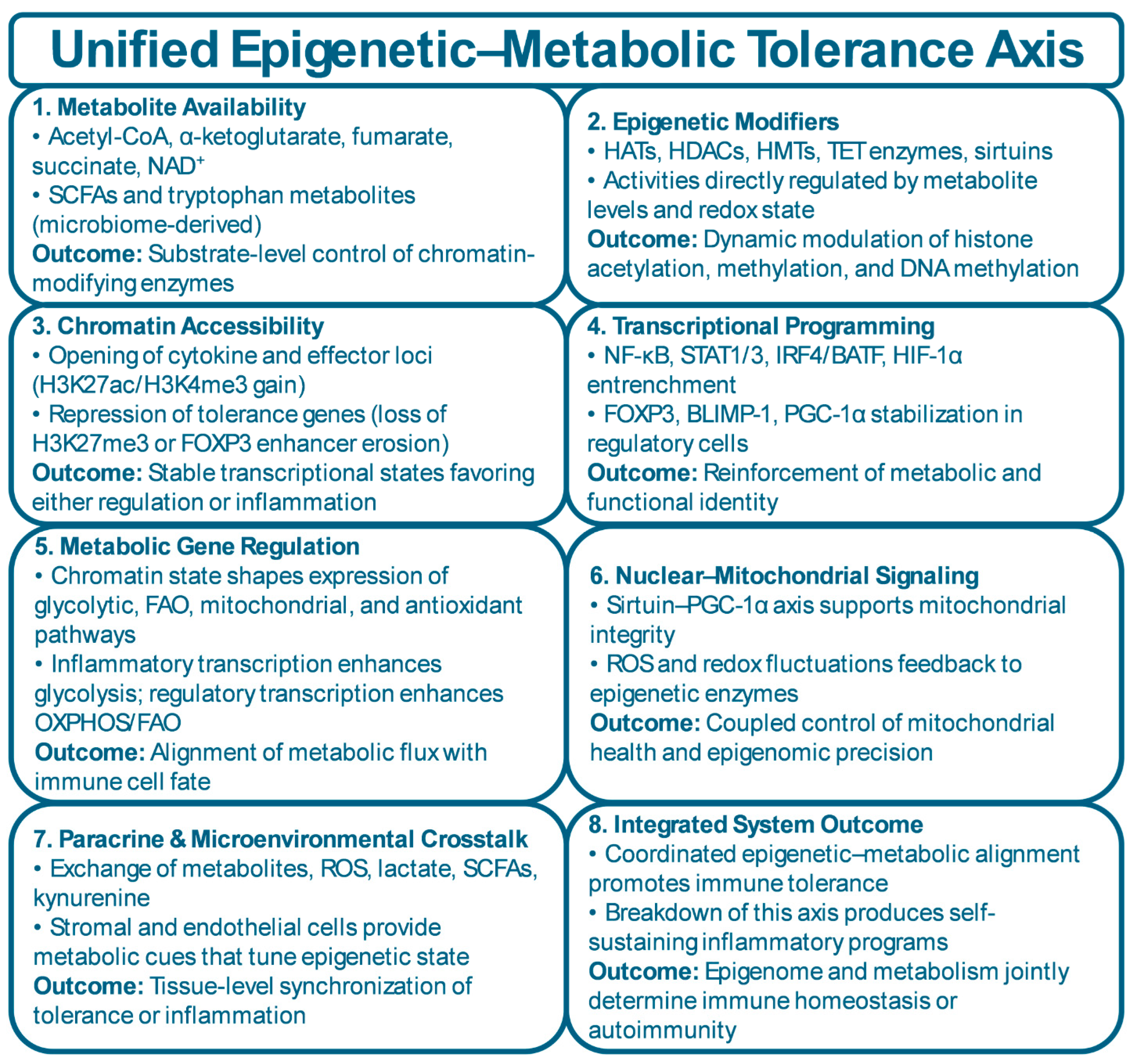

5. The Epigenetic–Metabolic Interface: A Unified Tolerance-Control Axis

5.1. Molecular Convergence of Metabolic and Epigenetic Networks

5.2. Cross-Talk Between Energy Flux and Chromatin Architecture

5.3. Multi-Cellular Integration of Epigenetic–Metabolic Circuits

5.4. Systems and Computational Perspectives

5.5. Epigenetic–Metabolic Reprogramming as a Therapeutic Framework

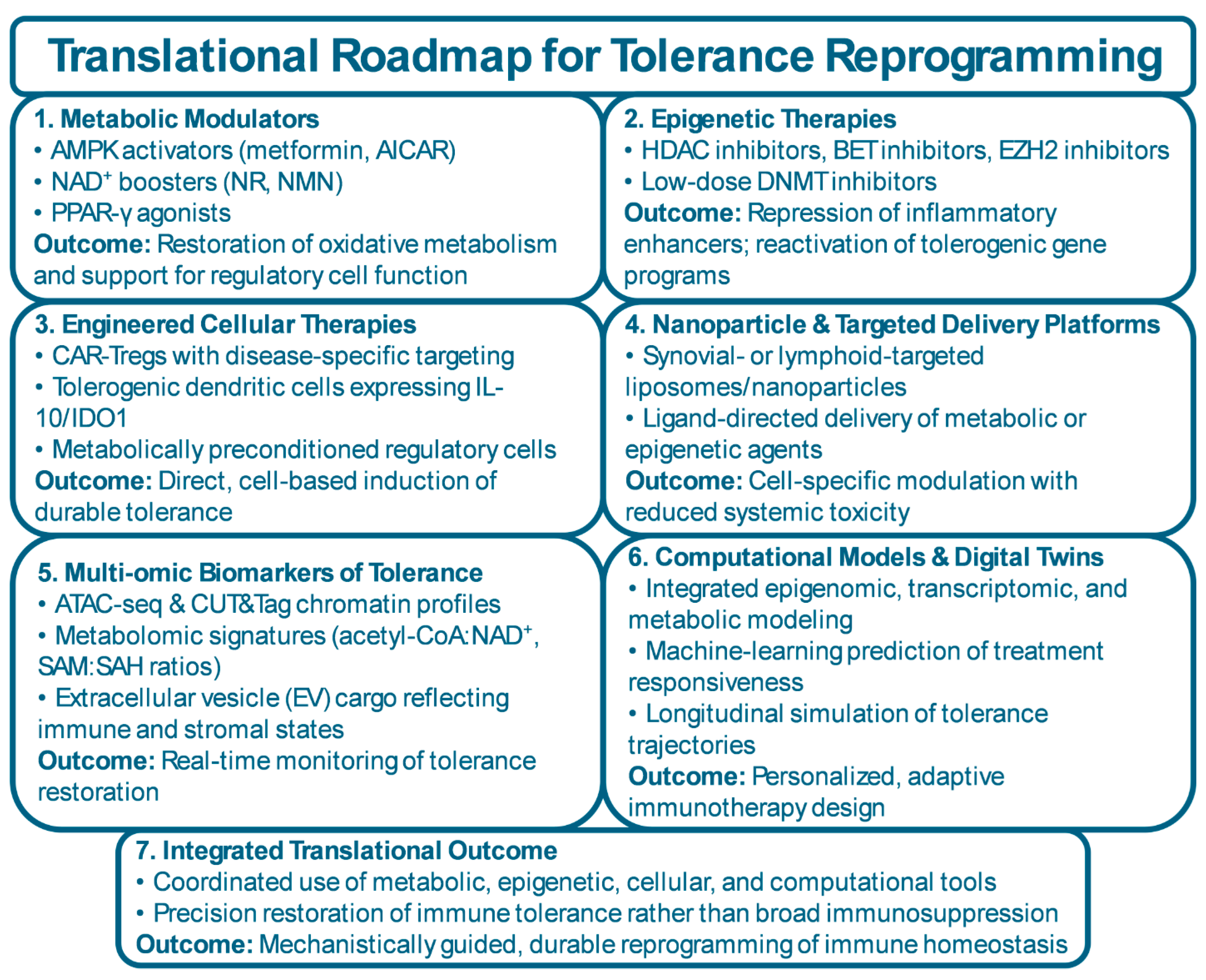

6. Translational Horizons: Reprogramming Tolerance

6.1. Principles of Tolerance Reprogramming

6.2. Epigenetic and Metabolic Therapeutics in Clinical Translation

6.3. Cellular and Bioengineered Therapies

6.4. Biomarkers and Digital Readouts of Tolerance Restoration

6.5. Integrative Systems Medicine and Precision Frameworks

6.6. Future Directions and Translational Outlook

7. Conclusion and Future Perspectives: Toward Programmable Immune Homeostasis

7.1. Conceptual Integration: From Suppression to Re-Education

7.2. Therapeutic Convergence and Cross-Disciplinary Integration

7.3. Challenges, Ethics, and Translational Governance

7.4. Outlook: Toward Rational Engineering of Immune Resilience

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical approval

Consent to participate

Consent to publication

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Jung SM, Kim WU. Targeted Immunotherapy for Autoimmune Disease. Immune Netw. 2022;22:e9. [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen F, Pirzada RH, Ahmad B, Choi B, Choi S. Understanding Autoimmunity: Mechanisms, Predisposing Factors, and Cytokine Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25. [CrossRef]

- Gao Z, Feng Y, Xu J, Liang J. T-cell exhaustion in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: New implications for immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:977394.

- Antony IR, Wong BHS, Kelleher D, Verma NK. Maladaptive T-Cell Metabolic Fitness in Autoimmune Diseases. Cells. 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Carbone F, Colamatteo A, La Rocca C, Lepore MT, Russo C, De Rosa G, et al. Metabolic Plasticity of Regulatory T Cells in Health and Autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2024;212:1859-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi E, Machado CR, Okano T, Boyle D, Wang W, Firestein GS. Joint-specific rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte regulation identified by integration of chromatin access and transcriptional activity. JCI Insight. 2024;9. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Teng XL, Wang F, Zheng Y, Qu G, Zhou Y, et al. Metabolic control of regulatory T cell stability and function by TRAF3IP3 at the lysosome. J Exp Med. 2018;215:2463-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelin WG, Jr., McKnight SL. Influence of metabolism on epigenetics and disease. Cell. 2013;153:56-69. [CrossRef]

- Lu C, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell Metab. 2012;16:9-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid MA, Dai Z, Locasale JW. The impact of cellular metabolism on chromatin dynamics and epigenetics. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1298-306. [CrossRef]

- Peng M, Yin N, Chhangawala S, Xu K, Leslie CS, Li MO. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science. 2016;354:481-4. [CrossRef]

- Fearon U, Canavan M, Biniecka M, Veale DJ. Hypoxia, mitochondrial dysfunction and synovial invasiveness in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:385-97.

- Angelin A, Gil-de-Gomez L, Dahiya S, Jiao J, Guo L, Levine MH, et al. Foxp3 Reprograms T Cell Metabolism to Function in Low-Glucose, High-Lactate Environments. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1282-93 e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang F, Wei K, Slowikowski K, Fonseka CY, Rao DA, Kelly S, et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:928-42.

- Sanchez-Lopez E, Cheng A, Guma M. Can Metabolic Pathways Be Therapeutic Targets in Rheumatoid Arthritis? J Clin Med. 2019;8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang C, Li D, Teng D, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Zhong Z, et al. Epigenetic Regulation in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:859400. [CrossRef]

- Sogkas G, Atschekzei F, Adriawan IR, Dubrowinskaja N, Witte T, Schmidt RE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms breaking immune tolerance in inborn errors of immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:1122-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Lareau CA, Bautista JL, Gupta AR, Sandor K, Germino J, et al. Single-cell multiomics defines tolerogenic extrathymic Aire-expressing populations with unique homology to thymic epithelium. Sci Immunol. 2021;6:eabl5053. [CrossRef]

- Chow A, Brown BD, Merad M. Studying the mononuclear phagocyte system in the molecular age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:788-98.

- Worrell JC, MacLeod MKL. Stromal-immune cell crosstalk fundamentally alters the lung microenvironment following tissue insult. Immunology. 2021;163:239-49.

- Croft AP, Campos J, Jansen K, Turner JD, Marshall J, Attar M, et al. Distinct fibroblast subsets drive inflammation and damage in arthritis. Nature. 2019;570:246-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han L, Wu T, Zhang Q, Qi A, Zhou X. Immune Tolerance Regulation Is Critical to Immune Homeostasis. J Immunol Res. 2025;2025:5006201.

- Hocking AM, Buckner JH. Genetic basis of defects in immune tolerance underlying the development of autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2022;13:972121. [CrossRef]

- Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:10-8.

- Qi Y, Zhang R, Lu Y, Zou X, Yang W. Aire and Fezf2, two regulators in medullary thymic epithelial cells, control autoimmune diseases by regulating TSAs: Partner or complementer? Front Immunol. 2022;13:948259. [PubMed]

- Anderson MS, Su MA. AIRE expands: new roles in immune tolerance and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:247-58. [PubMed]

- Okoreeh MK, Kennedy DE, Emmanuel AO, Veselits M, Moshin A, Ladd RH, et al. Asymmetrical forward and reverse developmental trajectories determine molecular programs of B cell antigen receptor editing. Sci Immunol. 2022;7:eabm1664.

- Pelanda R, Greaves SA, Alves da Costa T, Cedrone LM, Campbell ML, Torres RM. B-cell intrinsic and extrinsic signals that regulate central tolerance of mouse and human B cells. Immunol Rev. 2022;307:12-26. [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi S, Mikami N, Wing JB, Tanaka A, Ichiyama K, Ohkura N. Regulatory T Cells and Human Disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:541-66.

- Veh J, Ludwig C, Schrezenmeier H, Jahrsdorfer B. Regulatory B Cells-Immunopathological and Prognostic Potential in Humans. Cells. 2024;13.

- Nathan A, Asgari S, Ishigaki K, Valencia C, Amariuta T, Luo Y, et al. Single-cell eQTL models reveal dynamic T cell state dependence of disease loci. Nature. 2022;606:120-8.

- Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, Pearce EL. Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell. 2017;169:570-86.

- Shin B, Benavides GA, Geng J, Koralov SB, Hu H, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation Regulates the Fate Decision between Pathogenic Th17 and Regulatory T Cells. Cell Rep. 2020;30:1898-909 e4. [CrossRef]

- Tykocinski LO, Lauffer AM, Bohnen A, Kaul NC, Krienke S, Tretter T, et al. Synovial Fibroblasts Selectively Suppress Th1 Cell Responses through IDO1-Mediated Tryptophan Catabolism. J Immunol. 2017;198:3109-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson S, Coles M, Thomas T, Kollias G, Ludewig B, Turley S, et al. Fibroblasts as immune regulators in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:704-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Han K, Sack MN. Targeting NAD+ Metabolism to Modulate Autoimmunity and Inflammation. J Immunol. 2024;212:1043-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichhart T, Hengstschlager M, Linke M. Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:599-614. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808-12.

- Bradford HF, McDonnell TCR, Stewart A, Skelton A, Ng J, Baig Z, et al. Thioredoxin is a metabolic rheostat controlling regulatory B cells. Nat Immunol. 2024;25:873-85. [CrossRef]

- Wang AYL, Avina AE, Liu YY, Chang YC, Kao HK. Transcription Factor Blimp-1: A Central Regulator of Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025;14.

- Malik AE, Slauenwhite D, McAlpine SM, Hanly JG, Marshall JS, Issekutz TB. Differences in IDO1(+) dendritic cells and soluble CTLA-4 are associated with differential clinical responses to methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1352251. [CrossRef]

- Jia C, Wang Y, Wang Y, Cheng M, Dong W, Wei W, et al. TDO2-overexpressed Dendritic Cells Possess Tolerogenicity and Ameliorate Collagen-induced Arthritis by Modulating the Th17/Regulatory T Cell Balance. J Immunol. 2024;212:941-50.

- Chen J, Liu J, Cao X. Functional and Metabolic Heterogeneity of Dendritic Cells in Self-Tolerance and Autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2025;336:e70068. [CrossRef]

- Palsson-McDermott EM, O'Neill LAJ. Gang of 3: How the Krebs cycle-linked metabolites itaconate, succinate, and fumarate regulate macrophages and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2025;37:1049-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang K, Jagannath C. Crosstalk between metabolism and epigenetics during macrophage polarization. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2025;18:16. [CrossRef]

- Deochand DK, Dacic M, Bale MJ, Daman AW, Chaudhary V, Josefowicz SZ, et al. Mechanisms of epigenomic and functional convergence between glucocorticoid- and IL4-driven macrophage programming. Nat Commun. 2024;15:9000.

- Henry OC, O'Neill LAJ. Metabolic Reprogramming in Stromal and Immune Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis: Therapeutic Possibilities. Eur J Immunol. 2025;55:e202451381. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin R, Zhang J, Wang Y, Chen Z, He X, Zhang X, et al. EZH2 in non-cancerous diseases: Expanding horizons. Protein Cell. 2025;10.1093/procel/pwaf032. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Fu X, Zhang R, Wang Z, Qiu F, Chen X, et al. snoRNA Snord3 promotes rheumatoid arthritis by epigenetic regulation of ESM1 in fibroblast-like synoviocytes in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2025;17:eadt5340. [CrossRef]

- Gautam S, Whittaker JE, Vekariya R, Ramirez-Perez S, Gangishetti U, Drissi H, et al. The distinct transcriptomic signature of the resolution phase fibroblast-like synoviocytes supports endothelial cell dysfunction. Commun Biol. 2025;8:837.

- Giordo R, Posadino AM, Maccioccu P, Capobianco G, Zinellu A, Erre GL, et al. Sera from Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Induce Oxidative Stress and Pro-Angiogenic and Profibrotic Phenotypes in Human Endothelial Cells. J Clin Med. 2024;13.

- Deguine J, Xavier RJ. B cell tolerance and autoimmunity: Lessons from repertoires. J Exp Med. 2024;221.

- Wing JB, Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Human FOXP3(+) Regulatory T Cell Heterogeneity and Function in Autoimmunity and Cancer. Immunity. 2019;50:302-16.

- Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523-32.

- Kennedy A, Waters E, Rowshanravan B, Hinze C, Williams C, Janman D, et al. Differences in CD80 and CD86 transendocytosis reveal CD86 as a key target for CTLA-4 immune regulation. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:1365-78. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Huang L, Liu Y, Yi M, Chu Q, Jiao D, et al. Metabolic profiles of regulatory T cells and their adaptations to the tumor microenvironment: implications for antitumor immunity. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:104.

- Buck MD, O'Sullivan D, Klein Geltink RI, Curtis JD, Chang CH, Sanin DE, et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls T Cell Fate through Metabolic Programming. Cell. 2016;166:63-76.

- Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y, et al. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;146:772-84.

- Hamaidi I, Kim S. Sirtuins are crucial regulators of T cell metabolism and functions. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54:207-15.

- Hu S, Lin Y, Tang Y, Zhang J, He Y, Li G, et al. Targeting dysregulated intracellular immunometabolism within synovial microenvironment in rheumatoid arthritis with natural products. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1403823.

- Armaka M, Konstantopoulos D, Tzaferis C, Lavigne MD, Sakkou M, Liakos A, et al. Single-cell multimodal analysis identifies common regulatory programs in synovial fibroblasts of rheumatoid arthritis patients and modeled TNF-driven arthritis. Genome Med. 2022;14:78.

- Chen J, Li S, Zhu J, Su W, Jian C, Zhang J, et al. Multi-omics profiling reveals potential alterations in rheumatoid arthritis with different disease activity levels. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:74. [CrossRef]

- Rao DA, Gurish MF, Marshall JL, Slowikowski K, Fonseka CY, Liu Y, et al. Pathologically expanded peripheral T helper cell subset drives B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2017;542:110-4. [CrossRef]

- Marks KE, Rao DA. T peripheral helper cells in autoimmune diseases. Immunol Rev. 2022;307:191-202. [CrossRef]

- Palsson-McDermott EM, O'Neill LAJ. Targeting immunometabolism as an anti-inflammatory strategy. Cell Res. 2020;30:300-14. [CrossRef]

- Wardemann H, Nussenzweig MC. B-cell self-tolerance in humans. Adv Immunol. 2007;95:83-110.

- Nemazee D. Mechanisms of central tolerance for B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:281-94. [CrossRef]

- Wiggins KJ, Williams ME, Hicks SL, Padilla-Quirarte HO, Akther J, Randall TD, et al. EZH2 coordinates memory B-cell programming and recall responses. J Immunol. 2025;214:947-57.

- Zhen Y, Smith RD, Finkelman FD, Shao WH. Ezh2-mediated epigenetic modification is required for allogeneic T cell-induced lupus disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:133. [CrossRef]

- Gjertsson I, McGrath S, Grimstad K, Jonsson CA, Camponeschi A, Thorarinsdottir K, et al. A close-up on the expanding landscape of CD21-/low B cells in humans. Clin Exp Immunol. 2022;210:217-29. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernandez VA, Romero-Ramirez S, Cervantes-Diaz R, Carrillo-Vazquez DA, Navarro-Hernandez IC, Whittall-Garcia LP, et al. CD11c(+) T-bet(+) CD21(hi) B Cells Are Negatively Associated With Renal Impairment in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Act as a Marker for Nephritis Remission. Front Immunol. 2022;13:892241. [CrossRef]

- Jenks SA, Cashman KS, Zumaquero E, Marigorta UM, Patel AV, Wang X, et al. Distinct Effector B Cells Induced by Unregulated Toll-like Receptor 7 Contribute to Pathogenic Responses in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Immunity. 2018;49:725-39 e6. [CrossRef]

- Humby F, Bombardieri M, Manzo A, Kelly S, Blades MC, Kirkham B, et al. Ectopic lymphoid structures support ongoing production of class-switched autoantibodies in rheumatoid synovium. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1. [CrossRef]

- Tellier J, Shi W, Minnich M, Liao Y, Crawford S, Smyth GK, et al. Blimp-1 controls plasma cell function through the regulation of immunoglobulin secretion and the unfolded protein response. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:323-30. [CrossRef]

- Qian C, Cao X. Dendritic cells in the regulation of immunity and inflammation. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:3-11.

- Moller SH, Wang L, Ho PC. Metabolic programming in dendritic cells tailors immune responses and homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19:370-83. [CrossRef]

- Wu L, Yan Z, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Du J, Guo L, et al. Metabolic regulation of dendritic cell activation and immune function during inflammation. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1140749. [CrossRef]

- O'Neill LA, Kishton RJ, Rathmell J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:553-65. [CrossRef]

- Netea MG, Joosten LA, Latz E, Mills KH, Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, et al. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science. 2016;352:aaf1098. [CrossRef]

- Xu H, Zheng SG, Fox D. Editorial: Immunomodulatory Functions of Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes in Joint Inflammation and Destruction during Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:955.

- Nygaard G, Firestein GS. Restoring synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:316-33. [CrossRef]

- Falconer J, Murphy AN, Young SP, Clark AR, Tiziani S, Guma M, et al. Review: Synovial Cell Metabolism and Chronic Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:984-99. [CrossRef]

- Biniecka M, Canavan M, McGarry T, Gao W, McCormick J, Cregan S, et al. Dysregulated bioenergetics: a key regulator of joint inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:2192-200. [CrossRef]

- Ai R, Hammaker D, Boyle DL, Morgan R, Walsh AM, Fan S, et al. Joint-specific DNA methylation and transcriptome signatures in rheumatoid arthritis identify distinct pathogenic processes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11849. [CrossRef]

- Oaks Z, Perl A. Metabolic control of the epigenome in systemic Lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2014;47:256-64. [CrossRef]

- Crow MK, Ronnblom L. Type I interferons in host defence and inflammatory diseases. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6:e000336. [CrossRef]

- Dupre A, Pascaud J, Riviere E, Paoletti A, Ly B, Mingueneau M, et al. Association between T follicular helper cells and T peripheral helper cells with B-cell biomarkers and disease activity in primary Sjogren syndrome. RMD Open. 2021;7. [CrossRef]

- Verstappen GM, Pringle S, Bootsma H, Kroese FGM. Epithelial-immune cell interplay in primary Sjogren syndrome salivary gland pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17:333-48. [CrossRef]

- Allanore Y, Distler O. Systemic sclerosis in 2014: Advances in cohort enrichment shape future of trial design. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:72-4. [CrossRef]

- Henderson J, Duffy L, Stratton R, Ford D, O'Reilly S. Metabolic reprogramming of glycolysis and glutamine metabolism are key events in myofibroblast transition in systemic sclerosis pathogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:14026-38. [CrossRef]

- Mazzone R, Zwergel C, Artico M, Taurone S, Ralli M, Greco A, et al. The emerging role of epigenetics in human autoimmune disorders. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:34. [CrossRef]

- Britt EC, John SV, Locasale JW, Fan J. Metabolic regulation of epigenetic remodeling in immune cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2020;63:111-7.

- Sahu V, Lu C. Metabolism-driven chromatin dynamics: Molecular principles and technological advances. Mol Cell. 2025;85:262-75. [PubMed]

- Mei X, Zhang B, Zhao M, Lu Q. An update on epigenetic regulation in autoimmune diseases. J Transl Autoimmun. 2022;5:100176.

- Ha E, Bang SY, Lim J, Yun JH, Kim JM, Bae JB, et al. Genetic variants shape rheumatoid arthritis-specific transcriptomic features in CD4(+) T cells through differential DNA methylation, explaining a substantial proportion of heritability. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:876-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafari P, Yari K, Mostafaei S, Iranshahi N, Assar S, Fekri A, et al. Analysis of Helios gene expression and Foxp3 TSDR methylation in the newly diagnosed Rheumatoid Arthritis patients. Immunol Invest. 2018;47:632-42. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Zhao M, Lu Q. Demethylation of promoter regulatory elements contributes to CD70 overexpression in CD4+ T cells from patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:425-30. [PubMed]

- Correa LO, Jordan MS, Carty SA. DNA Methylation in T-Cell Development and Differentiation. Crit Rev Immunol. 2020;40:135-56.

- Lio CJ, Rao A. TET Enzymes and 5hmC in Adaptive and Innate Immune Systems. Front Immunol. 2019;10:210.

- Feng D, Zhao H, Wang Q, Wu J, Ouyang L, Jia S, et al. Aberrant H3K4me3 modification of immune response genes in CD4(+) T cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;130:111748.

- Zheng QH, Zhai Y, Wang YH, Pan Z. The role of hypoxic microenvironment in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1633406. [CrossRef]

- Sabari BR, Zhang D, Allis CD, Zhao Y. Metabolic regulation of gene expression through histone acylations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:90-101. [CrossRef]

- Matilainen O, Quiros PM, Auwerx J. Mitochondria and Epigenetics - Crosstalk in Homeostasis and Stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:453-63. [CrossRef]

- Hu P, Dong ZS, Zheng S, Guan X, Zhang L, Li L, et al. The effects of miR-26b-5p on fibroblast-like synovial cells in rheumatoid arthritis (RA-FLS) via targeting EZH2. Tissue Cell. 2021;72:101591.

- Allis CD, Jenuwein T. The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:487-500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coda DM, Watt L, Glauser L, Batiuk MY, Burns AM, Stahl CL, et al. Cell-type- and locus-specific epigenetic editing of memory expression. Nat Genet. 2025;57:2661-8. [CrossRef]

- Wen J, Liu J, Wan L, Wang F, Li Y. Metabolic reprogramming: the central mechanism driving inflammatory polarization in rheumatoid arthritis and the regulatory role of traditional Chinese medicine. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1659541. [CrossRef]

- Philippon EML, van Rooijen LJE, Khodadust F, van Hamburg JP, van der Laken CJ, Tas SW. A novel 3D spheroid model of rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue incorporating fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1188835. [PubMed]

- Bacalao MA, Satterthwaite AB. Recent Advances in Lupus B Cell Biology: PI3K, IFNgamma, and Chromatin. Front Immunol. 2020;11:615673. [PubMed]

- Scharer CD, Blalock EL, Mi T, Barwick BG, Jenks SA, Deguchi T, et al. Epigenetic programming underpins B cell dysfunction in human SLE. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1071-82.

- Shivashankar GV. Mechanical regulation of genome architecture and cell-fate decisions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2019;56:115-21. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AB, Denko N, Barton MC. Hypoxia induces a novel signature of chromatin modifications and global repression of transcription. Mutat Res. 2008;640:174-9.

- Mormone E, Iorio EL, Abate L, Rodolfo C. Sirtuins and redox signaling interplay in neurogenesis, neurodegenerative diseases, and neural cell reprogramming. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1073689.

- Corcoran SE, O'Neill LA. HIF1alpha and metabolic reprogramming in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3699-707. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier UH, Wang L, Bhatti TR, Liu Y, Han R, Ge G, et al. Sirtuin-1 targeting promotes Foxp3+ T-regulatory cell function and prolongs allograft survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1022-9. [CrossRef]

- Blagih J, Coulombe F, Vincent EE, Dupuy F, Galicia-Vazquez G, Yurchenko E, et al. The energy sensor AMPK regulates T cell metabolic adaptation and effector responses in vivo. Immunity. 2015;42:41-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014;345:1250684. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein K, Kabala PA, Grabiec AM, Gay RE, Kolling C, Lin LL, et al. The bromodomain protein inhibitor I-BET151 suppresses expression of inflammatory genes and matrix degrading enzymes in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:422-9. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Li M, Zhu Y, Liu K, Liu M, Liu Y, et al. EZH2 inhibition dampens autoantibody production in lupus by restoring B cell immune tolerance. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;119:110155. [CrossRef]

- Grabiec AM, Korchynskyi O, Tak PP, Reedquist KA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors suppress rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte and macrophage IL-6 production by accelerating mRNA decay. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:424-31.

- Li S, Su J, Cai W, Liu JX. Nanomaterials Manipulate Macrophages for Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:699245.

- Parvin N, Joo SW, Mandal TK. Biodegradable and Stimuli-Responsive Nanomaterials for Targeted Drug Delivery in Autoimmune Diseases. J Funct Biomater. 2025;16. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhang C, Hu Y, Peng J, Feng Q, Hu X. Nicotinamide enhances Treg differentiation by promoting Foxp3 acetylation in immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 2024;205:2432-41. [CrossRef]

- Yue Y, Ren Y, Lu C, Li P, Zhang G. Epigenetic regulation of human FOXP3+ Tregs: from homeostasis maintenance to pathogen defense. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1444533. [CrossRef]

- Matias MI, Yong CS, Foroushani A, Goldsmith C, Mongellaz C, Sezgin E, et al. Regulatory T cell differentiation is controlled by alphaKG-induced alterations in mitochondrial metabolism and lipid homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109911. [CrossRef]

- Hilton IB, D'Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, Reddy TE, et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:510-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu XS, Wu H, Ji X, Stelzer Y, Wu X, Czauderna S, et al. Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell. 2016;167:233-47 e17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Zhang Q, Zhou H, Jin L, Liu C, Yang M, et al. GLP-1R activation attenuates the progression of pulmonary fibrosis via disrupting NLRP3 inflammasome/PFKFB3-driven glycolysis interaction and histone lactylation. J Transl Med. 2024;22:954. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J. NAD(+) Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015;22:31-53. [CrossRef]

- Liu PS, Wang H, Li X, Chao T, Teav T, Christen S, et al. alpha-ketoglutarate orchestrates macrophage activation through metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:985-94. [CrossRef]

- Palmer CS, Ostrowski M, Balderson B, Christian N, Crowe SM. Glucose metabolism regulates T cell activation, differentiation, and functions. Front Immunol. 2015;6:1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G, Green DR, et al. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1367-76.

- Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S, Carter R, Finkelstein D, et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 2011;35:871-82. [CrossRef]

- Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM, Shen H, Wang LS, et al. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103-7. [CrossRef]

- Majeed Y, Halabi N, Madani AY, Engelke R, Bhagwat AM, Abdesselem H, et al. SIRT1 promotes lipid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis in adipocytes and coordinates adipogenesis by targeting key enzymatic pathways. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8177. [CrossRef]

- Xin T, Lu C. SirT3 activates AMPK-related mitochondrial biogenesis and ameliorates sepsis-induced myocardial injury. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:16224-37.

- Shi Y, Zhang H, Miao C. Metabolic reprogram and T cell differentiation in inflammation: current evidence and future perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2025;11:123. [CrossRef]

- Palsson-McDermott EM, Curtis AM, Goel G, Lauterbach MAR, Sheedy FJ, Gleeson LE, et al. Pyruvate Kinase M2 Regulates Hif-1alpha Activity and IL-1beta Induction and Is a Critical Determinant of the Warburg Effect in LPS-Activated Macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015;21:347. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmaus PWF, Herrada AA, Guy C, Neale G, Dhungana Y, Long L, et al. Critical roles of mTORC1 signaling and metabolic reprogramming for M-CSF-mediated myelopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2629-47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pap T, Franz JK, Hummel KM, Jeisy E, Gay R, Gay S. Activation of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis: lack of Expression of the tumour suppressor PTEN at sites of invasive growth and destruction. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:59-64. [CrossRef]

- Gergely P, Jr., Niland B, Gonchoroff N, Pullmann R, Jr., Phillips PE, Perl A. Persistent mitochondrial hyperpolarization, increased reactive oxygen intermediate production, and cytoplasmic alkalinization characterize altered IL-10 signaling in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2002;169:1092-101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam JH, Lee JH, Choi HJ, Choi SY, Noh KE, Jung NC, et al. TNF-alpha Induces Mitophagy in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts, and Mitophagy Inhibition Alleviates Synovitis in Collagen Antibody-Induced Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang W, Wang S, Yan D, Wu J, Zhang Y, Li W, et al. The cGAS-STING pathway-dependent sensing of mitochondrial DNA mediates ocular surface inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:371. [CrossRef]

- Iwata S, Hajime Sumikawa M, Tanaka Y. B cell activation via immunometabolism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1155421. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2013;496:238-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundo K, Trauelsen M, Pedersen SF, Schwartz TW. Why Warburg Works: Lactate Controls Immune Evasion through GPR81. Cell Metab. 2020;31:666-8. [CrossRef]

- Mills EL, Ryan DG, Prag HA, Dikovskaya D, Menon D, Zaslona Z, et al. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature. 2018;556:113-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang HC, Chang WC, Lee DY, Li XG, Hung MC. IRG1/Itaconate induces metabolic reprogramming to suppress ER-positive breast cancer cell growth. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:1067-81.

- Carey BW, Finley LW, Cross JR, Allis CD, Thompson CB. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2015;518:413-6. [CrossRef]

- Mentch SJ, Mehrmohamadi M, Huang L, Liu X, Gupta D, Mattocks D, et al. Histone Methylation Dynamics and Gene Regulation Occur through the Sensing of One-Carbon Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;22:861-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghakhani S, Zerrouk N, Niarakis A. Metabolic Reprogramming of Fibroblasts as Therapeutic Target in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Cancer: Deciphering Key Mechanisms Using Computational Systems Biology Approaches. Cancers (Basel). 2020;13.

- Yennemadi AS, Keane J, Leisching G. Mitochondrial bioenergetic changes in systemic lupus erythematosus immune cell subsets: Contributions to pathogenesis and clinical applications. Lupus. 2023;32:603-11. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Sanchez C, Escudero-Contreras A, Cerdo T, Sanchez-Mendoza LM, Llamas-Urbano A, la Rosa IA, et al. Preclinical Characterization of Pharmacologic NAD(+) Boosting as a Promising Therapeutic Approach in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75:1749-61. [CrossRef]

- Han J, Zhou Z, Wang H, Chen Y, Li W, Dai M, et al. Dysfunctional glycolysis-UCP2-fatty acid oxidation promotes CTLA4(int)FOXP3(int) regulatory T-cell production in rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med. 2025;31:310. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Sun L, Yang B, Li W, Zhang C, Yang X, et al. Zfp335 establishes eTreg lineage and neonatal immune tolerance by targeting Hadha-mediated fatty acid oxidation. J Clin Invest. 2023;133. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Mahony CB, Torres A, Murillo-Saich J, Kemble S, Cedeno M, et al. Dual inhibition of glycolysis and glutaminolysis for synergistic therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:176. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Song SG, Kim G, Kim S, Yoo HJ, Koh J, et al. CRIF1 deficiency induces FOXP3(LOW) inflammatory non-suppressive regulatory T cells, thereby promoting antitumor immunity. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadj9600. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Moyado IF, Ko M, Hogan PG, Rao A. TET Enzymes in the Immune System: From DNA Demethylation to Immunotherapy, Inflammation, and Cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2024;42:455-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, LaBapuchi, Liu M, Chen L. The complex link of the folate-homocysteine axis to myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure: from mechanistic exploration to clinical vision. J Adv Res. 2025;10.1016/j.jare.2025.09.026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada M, Kono M. Metabolites as regulators of autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1637436. [PubMed]

- Yan Z, Chen Q, Xia Y. Oxidative Stress Contributes to Inflammatory and Cellular Damage in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Cellular Markers and Molecular Mechanism. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:453-65.

- Cai X, Yao Y. Epigenetic modifications of immune cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Med. 2025;57:2533432.

- Bellanti F, Coda ARD, Trecca MI, Lo Buglio A, Serviddio G, Vendemiale G. Redox Imbalance in Inflammation: The Interplay of Oxidative and Reductive Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025;14.

- Huang H, Li G, He Y, Chen J, Yan J, Zhang Q, et al. Cellular succinate metabolism and signaling in inflammation: implications for therapeutic intervention. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1404441. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Huo C, Liu A, Zhu Y. Mitochondria: a breakthrough in combating rheumatoid arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1439182. [CrossRef]

- Damasceno LEA, Barbosa GAC, Sparwasser T, Cunha TM, Cunha FQ, Alves-Filho JC. PGC1alpha-mediated mitochondrial fitness promotes T(reg) cell differentiation. Cell Immunol. 2025;414:104985. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai Z, Ren J, Liu J, Zhang C, Huang H, Zhao X, et al. DRP1 downregulation impairs mitophagy, driving mitochondrial ROS and SASP production in rheumatoid arthritis CD4(+)PD-1(+)T cells. Redox Biol. 2025;86:103818. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, An H, Liu T, Qin C, Sesaki H, Guo S, et al. Metformin Improves Mitochondrial Respiratory Activity through Activation of AMPK. Cell Rep. 2019;29:1511-23 e5. [CrossRef]

- Bogatkevich GS, Highland KB, Akter T, Silver RM. The PPARgamma Agonist Rosiglitazone Is Antifibrotic for Scleroderma Lung Fibroblasts: Mechanisms of Action and Differential Racial Effects. Pulm Med. 2012;2012:545172. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez D, Bonilla E, Mirza N, Niland B, Perl A. Rapamycin reduces disease activity and normalizes T cell activation-induced calcium fluxing in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2983-8. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Massett MP. Beneficial effects of rapamycin on endothelial function in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Physiol. 2024;15:1446836. [CrossRef]

- Gedaly R, Orozco G, Lewis LJ, Valvi D, Chapelin F, Khurana A, et al. Effect of mitochondrial oxidative stress on regulatory T cell manufacturing for clinical application in transplantation: Results from a pilot study. Am J Transplant. 2025;25:720-33. [PubMed]

- Wu H, Zhao X, Hochrein SM, Eckstein M, Gubert GF, Knopper K, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes the transition of precursor to terminally exhausted T cells through HIF-1alpha-mediated glycolytic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6858. [CrossRef]

- Choi J, Chudziak J, Lee JH. Bi-directional regulation between inflammation and stem cells in the respiratory tract. J Cell Sci. 2024;137.

- Qiu Y, Xu Y, Ding X, Zhao C, Cheng H, Li G. Bi-directional metabolic reprogramming between cancer cells and T cells reshapes the anti-tumor immune response. PLoS Biol. 2025;23:e3003284. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Ge S, Liao T, Yuan M, Qian W, Chen Q, et al. Integrative single-cell metabolomics and phenotypic profiling reveals metabolic heterogeneity of cellular oxidation and senescence. Nat Commun. 2025;16:2740. [CrossRef]

- Keating ST, El-Osta A. Epigenetics and metabolism. Circ Res. 2015;116:715-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghakhani S, Soliman S, Niarakis A. Metabolic reprogramming in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts: A hybrid modeling approach. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022;18:e1010408. [CrossRef]

- Dai Z, Ramesh V, Locasale JW. The evolving metabolic landscape of chromatin biology and epigenetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21:737-53. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Long Y, Paucek RD, Gooding AR, Lee T, Burdorf RM, et al. Regulation of histone methylation by automethylation of PRC2. Genes Dev. 2019;33:1416-27. [CrossRef]

- Chen RR, Li YY, Wu JW, Wang Y, Song W, Shao D, et al. SIRT6 in health and diseases: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic prospects. Pharmacol Res. 2025;221:107984. [CrossRef]

- Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science. 2009;324:1076-80. [CrossRef]

- Canto C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:98-105. [CrossRef]

- Koh JH, Kim YW, Seo DY, Sohn TS. Mitochondrial TFAM as a Signaling Regulator between Cellular Organelles: A Perspective on Metabolic Diseases. Diabetes Metab J. 2021;45:853-65. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Armada MJ, Fernandez-Rodriguez JA, Blanco FJ. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11.

- Imai S, Guarente L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:464-71. [CrossRef]

- Gong L, Lei J, Zhou Y, Zhang J, Wu L, Chen Y, et al. Regulation of Histone Acetylation During Inflammation Resolution. Immunotargets Ther. 2025;14:1145-58. [CrossRef]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiles WJ, Ovens AJ, Kemp BE, Galic S, Petersen J, Oakhill JS. New developments in AMPK and mTORC1 cross-talk. Essays Biochem. 2024;68:321-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao T, Fan J, Abu-Zaid A, Burley SK, Zheng XFS. Nuclear mTOR Signaling Orchestrates Transcriptional Programs Underlying Cellular Growth and Metabolism. Cells. 2024;13. [CrossRef]

- Kristiani L, Kim Y. The Interplay between Oxidative Stress and the Nuclear Lamina Contributes to Laminopathies and Age-Related Diseases. Cells. 2023;12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin Y, Qiu T, Wei G, Que Y, Wang W, Kong Y, et al. Role of Histone Post-Translational Modifications in Inflammatory Diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:852272. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Krol A, Nehring HP, Krause FF, Wempe A, Raifer H, Nist A, et al. Lactate induces metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells. EMBO Rep. 2022;23:e54685. [CrossRef]

- Manoharan I, Prasad PD, Thangaraju M, Manicassamy S. Lactate-Dependent Regulation of Immune Responses by Dendritic Cells and Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2021;12:691134. [CrossRef]

- De Lima J, Boutet MA, Bortolotti O, Chepeaux LA, Glasson Y, Dume AS, et al. Spatial mapping of rheumatoid arthritis synovial niches reveals a LYVE1(+) macrophage network associated with response to therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2025;10.1016/j.ard.2025.07.019. [CrossRef]

- Xie L, Zhou Y, Hu Z, Zhang W, Zhang X. Integrative multi-omics reveals energy metabolism-related prognostic signatures and immunogenetic landscapes in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1679464. [CrossRef]

- Park JH, Sim DW, Kim SY, Choi JY, Hyun SH, Joung JG. Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis Uncovers Immune-Metabolic Interplay in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17.

- Steinberg GR, Carling D. AMP-activated protein kinase: the current landscape for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:527-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang J, Chen W, Hou P, Liu Z, Zuo M, Liu S, et al. NAD(+) metabolism-based immunoregulation and therapeutic potential. Cell Biosci. 2023;13:81. [CrossRef]

- Wu YL, Lin ZJ, Li CC, Lin X, Shan SK, Guo B, et al. Epigenetic regulation in metabolic diseases: mechanisms and advances in clinical study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:98. [CrossRef]

- Sadria M, Layton AT. Interactions among mTORC, AMPK and SIRT: a computational model for cell energy balance and metabolism. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19:57. [CrossRef]

- Saravia J, Raynor JL, Chapman NM, Lim SA, Chi H. Signaling networks in immunometabolism. Cell Res. 2020;30:328-42. [CrossRef]

- Su X, Wellen KE, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolic control of methylation and acetylation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;30:52-60. [CrossRef]

- Calciolari B, Scarpinello G, Tubi LQ, Piazza F, Carrer A. Metabolic control of epigenetic rearrangements in B cell pathophysiology. Open Biol. 2022;12:220038. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Wang G, Li Y, Lei D, Xiang J, Ouyang L, et al. Recent progress in DNA methyltransferase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1072651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Wang Y, Yuan J, Li N, Pei S, Xu J, et al. Macrophage/microglial Ezh2 facilitates autoimmune inflammation through inhibition of Socs3. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1365-82. [CrossRef]

- Maksylewicz A, Bysiek A, Lagosz KB, Macina JM, Kantorowicz M, Bereta G, et al. BET Bromodomain Inhibitors Suppress Inflammatory Activation of Gingival Fibroblasts and Epithelial Cells From Periodontitis Patients. Front Immunol. 2019;10:933. [CrossRef]

- Saouaf SJ, Li B, Zhang G, Shen Y, Furuuchi N, Hancock WW, et al. Deacetylase inhibition increases regulatory T cell function and decreases incidence and severity of collagen-induced arthritis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;87:99-104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong C, Tontonoz P. Coordination of inflammation and metabolism by PPAR and LXR nuclear receptors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:461-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon NJ. The Role of NAD+ in Regenerative Medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:41S-8S. [CrossRef]

- Gongol B, Sari I, Bryant T, Rosete G, Marin T. AMPK: An Epigenetic Landscape Modulator. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan W, Ding Y, Yu X, Ma D, Yang B, Li Y, et al. Metformin mitigates autoimmune insulitis by inhibiting Th1 and Th17 responses while promoting Treg production. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:2393-402.

- Lee SY, Moon SJ, Kim EK, Seo HB, Yang EJ, Son HJ, et al. Metformin Suppresses Systemic Autoimmunity in Roquin(san/san) Mice through Inhibiting B Cell Differentiation into Plasma Cells via Regulation of AMPK/mTOR/STAT3. J Immunol. 2017;198:2661-70. [CrossRef]

- Sano H, Kratz A, Nishino T, Imamura H, Yoshida Y, Shimizu N, et al. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) alleviates the poly(I:C)-induced inflammatory response in human primary cell cultures. Sci Rep. 2023;13:11765. [CrossRef]

- Mann R, Stavrou V, Dimeloe S. NAD + metabolism and function in innate and adaptive immune cells. J Inflamm (Lond). 2025;22:30. [CrossRef]

- Wu CY, Reynolds WC, Abril I, McManus AJ, Brenner C, Gonzalez-Irizarry G, et al. Effects of nicotinamide riboside on NAD+ levels, cognition, and symptom recovery in long-COVID: a randomized controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2025;89:103633. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Gao Y, Aaron N, Qiang L. A glimpse of the connection between PPARgamma and macrophage. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1254317. [CrossRef]

- Liang Y, Wang Y, Xing J, Li J, Zhang K. The regulatory mechanisms and treatment of HDAC6 in immune dysregulation diseases. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1653588. [CrossRef]

- Park JK, Shon S, Yoo HJ, Suh DH, Bae D, Shin J, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 suppresses inflammatory responses and invasiveness of fibroblast-like-synoviocytes in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang ZQ, Zhang ZC, Wu YY, Pi YN, Lou SH, Liu TB, et al. Bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) proteins: biological functions, diseases, and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:420. [CrossRef]

- Zhou D, Tian JM, Li Z, Huang J. Cbx4 SUMOylates BRD4 to regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines in post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56:2184-201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang L, Zhou R. Histone methyltransferase EZH2 in proliferation, invasion, and migration of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2022;40:262-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu L, Liu Z, Cui Q, Guan G, Hui R, Wang X, et al. Epigenetic modification of CD4(+) T cells into Tregs by 5-azacytidine as cellular therapeutic for atherosclerosis treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:689. [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar G, Semenkovich NP, Arra M, Mims DK, Naqvi SK, Peterson T, et al. DNA hypomethylation ameliorates erosive inflammatory arthritis by modulating interferon regulatory factor-8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:e2310264121. [CrossRef]

- Durgam SS, Rosado-Sanchez I, Yin D, Speck M, Mojibian M, Sayin I, et al. CAR Treg synergy with anti-CD154 promotes infectious tolerance and dictates allogeneic heart transplant acceptance. JCI Insight. 2025;10. [CrossRef]

- Dong S, Zhang T, Zhai Y, Naatz LC, Carlson NG, Rose JW, et al. 3-in-one (PD-1)CAR Tregs: A bioengineered cellular therapy for target engagement, activation, and immunosuppression with reparative potential. iScience. 2025;28:113677. [CrossRef]

- Stoppelenburg AJ, Schreibelt G, Koeneman B, Welsing P, Breman EJ, Lammers L, et al. Design of TOLERANT: phase I/II safety assessment of intranodal administration of HSP70/mB29a self-peptide antigen-loaded autologous tolerogenic dendritic cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e078231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long EL, Stanway J, White M, Goudie N, Phillipson J, Morton M, et al. Autologous Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells for Rheumatoid Arthritis-2 (AuToDeCRA-2) study: protocol for a single-centre, experimental medicine study investigating the route of delivery and potential efficacy of autologous tolerogenic dendritic cell (TolDC) therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Trials. 2025;26:278. [PubMed]

- Wong C, Stoilova I, Gazeau F, Herbeuval JP, Fourniols T. Mesenchymal stromal cell derived extracellular vesicles as a therapeutic tool: immune regulation, MSC priming, and applications to SLE. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1355845.

- Gao YF, Zhao N, Hu CH. Harnessing mesenchymal stem/stromal cells-based therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: mechanisms, clinical applications, and microenvironmental interactions. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16:379.

- Jia N, Gao Y, Li M, Liang Y, Li Y, Lin Y, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of proinflammatory macrophages by target delivered roburic acid effectively ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis symptoms. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:280. [PubMed]

- Xu YD, Liang XC, Li ZP, Wu ZS, Yang J, Jia SZ, et al. Apoptotic body-inspired nanotherapeutics efficiently attenuate osteoarthritis by targeting BRD4-regulated synovial macrophage polarization. Biomaterials. 2024;306:122483.

- Zerrouk N, Auge F, Niarakis A. Building a modular and multi-cellular virtual twin of the synovial joint in Rheumatoid Arthritis. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7:379.

- Niarakis A, Laubenbacher R, An G, Ilan Y, Fisher J, Flobak A, et al. Immune digital twins for complex human pathologies: applications, limitations, and challenges. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2024;10:141.

- Hurez V, Gauderat G, Soret P, Myers R, Dasika K, Sheehan R, et al. Virtual patients inspired by multiomics predict the efficacy of an anti-IFNalpha mAb in cutaneous lupus. iScience. 2025;28:111754.

- Beheshti SA, Shamsasenjan K, Ahmadi M, Abbasi B. CAR Treg: A new approach in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;102:108409. [CrossRef]

- Galgani M, De Rosa V, La Cava A, Matarese G. Role of Metabolism in the Immunobiology of Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2016;197:2567-75.

- Hassan M, Elzallat M, Mohammed DM, Balata M, El-Maadawy WH. Exploiting regulatory T cells (Tregs): Cutting-edge therapy for autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;155:114624. [PubMed]

- Maldonado RA, von Andrian UH. How tolerogenic dendritic cells induce regulatory T cells. Adv Immunol. 2010;108:111-65. [PubMed]

- Faas PPM, Scharmann SD, Pishesha N. Antigen-Specific Tolerance: Clinical and Preclinical Approaches in Autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 2025;55:e70067. [PubMed]

- Zhao Z, Zhang L, Ocansey DKW, Wang B, Mao F. The role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome in epigenetic modifications in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1166536. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Lee MJ, Bae EH, Ryu JS, Kaur G, Kim HJ, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Profiles of Functionally Effective MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Immunomodulation. Mol Ther. 2020;28:1628-44. [CrossRef]

- Samavati SF, Yarani R, Kiani S, HoseinKhani Z, Mehrabi M, Levitte S, et al. Therapeutic potential of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Inflamm (Lond). 2024;21:20. [CrossRef]

- Samstein RM, Arvey A, Josefowicz SZ, Peng X, Reynolds A, Sandstrom R, et al. Foxp3 exploits a pre-existent enhancer landscape for regulatory T cell lineage specification. Cell. 2012;151:153-66. [CrossRef]

- Bai L, Hao X, Keith J, Feng Y. DNA Methylation in Regulatory T Cell Differentiation and Function: Challenges and Opportunities. Biomolecules. 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Schvartzman JM, Thompson CB, Finley LWS. Metabolic regulation of chromatin modifications and gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:2247-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alissafi T, Kalafati L, Lazari M, Filia A, Kloukina I, Manifava M, et al. Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage Underlies Regulatory T Cell Defects in Autoimmunity. Cell Metab. 2020;32:591-604 e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu K, Liu Q, Wu K, Liu L, Zhao M, Yang H, et al. Extracellular vesicles as potential biomarkers and therapeutic approaches in autoimmune diseases. J Transl Med. 2020;18:432. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller EA, Bintu L, Rots MG. Epigenetic editing: from concept to clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2025;10.1038/s41573-025-01323-0. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Q, Zhang C, Zhang W, Zhang S, Liu Q, Guo Y. Applications and challenges of biomarker-based predictive models in proactive health management. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1633487. [CrossRef]

- Galvan S, Teixeira AP, Fussenegger M. Enhancing cell-based therapies with synthetic gene circuits responsive to molecular stimuli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2024;121:2987-3000. [CrossRef]

| Cell Type | Metabolic Program | Epigenetic Program | Key Tolerance Function | Breakdown in Disease | References |

| Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) | High OXPHOS and FAO; elevated NAD⁺; AMPK–SIRT1 activation | FOXP3 CNS2 demethylation; repressive histone marks at effector loci | Suppress effector T cells; produce IL-10 and TGF-β; maintain immune homeostasis | FOXP3 enhancer erosion; glycolytic shift; reduced NAD⁺/sirtuin activity → instability and conversion to effector-like cells | [13,38] |

| Regulatory B Cells (Bregs) | Balanced glycolysis/OXPHOS; low ROS | BLIMP-1 / PRDM1–driven chromatin program | IL-10 production; control of germinal-center reactions; restraint of autoantibody formation | Oxidative stress; loss of BLIMP-1 stability; shift toward plasma-cell or inflammatory B-cell fates | [39,40] |

| Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells (tolDCs) | OXPHOS-dominant; IDO1 activation; kynurenine pathway | Low H3K27ac at costimulatory loci; tolerogenic enhancer profile | Induce Tregs; present antigen with low costimulation; promote peripheral tolerance | Upregulation of CD80/CD86; loss of IDO1 activity; switch to glycolytic, pro-inflammatory DC phenotype | [41,42,43] |

| M2-like Macrophages | OXPHOS-driven; low succinate; low HIF-1α | Repressive chromatin at IL1B, TNF, and inflammatory loci | Tissue repair; IL-10 secretion; clearance of apoptotic cells | Succinate accumulation; HIF-1α activation; shift to M1-like inflammatory macrophages | [44,45,46] |

| Homeostatic Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes (FLS) | Low glycolysis; intact mitochondrial function | Closed chromatin at inflammatory genes; retinoic-acid responsive regulatory enhancers | Maintain quiescent synovial environment; structural integrity; anti-inflammatory metabolite release | Increased glycolysis; EZH2-driven repression of regulatory genes; acquisition of invasive, inflammatory FLS phenotype | [47,48,49] |

| Stromal & Endothelial Cells | Provide oxidative tissue niche; produce RA, kynurenine | Repressed ICAM1/VCAM1 under homeostasis | Regulate immune-cell trafficking; sustain tissue-level equilibrium | Mechanical stress, hypoxia, and cytokines induce chromatin opening → increased adhesion molecules and inflammatory recruitment | [50,51] |

| Pathway | Key Metabolite | Chromatin Effect | Immune Fate Effect | Disease Context | References |

| Glycolysis | Lactate, pyruvate | Increased H3K27ac via acetyl-CoA availability; HIF-1α–driven enhancer activation | Promotes Th17 differentiation, effector T-cell expansion, inflammatory macrophages, invasive FLS | RA synovium shows high glycolytic flux; Th17–FLS inflammatory loops | [11,132,151] |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) | NAD⁺, ATP | Sirtuin-dependent histone deacetylation; repression of effector loci; maintenance of FOXP3 enhancer integrity | Supports Tregs, Bregs, tolerogenic DCs, and M2 macrophages | NAD⁺ depletion in RA/SLE reduces Treg stability and mitochondrial fitness | [59,152,153] |

| Fatty-Acid Oxidation (FAO) | Acetyl-CoA, NADH | Promotes SIRT1/3 activity; enhances repressive chromatin landscapes | Stabilizes Treg phenotype; supports long-lived regulatory programs | FAO impairment contributes to Treg instability in autoimmunity | [59,154,155] |

| Glutaminolysis | α-Ketoglutarate (αKG) | αKG supports TET-mediated DNA/histone demethylation; maintains open chromatin at regulatory genes | Enables Treg and Breg epigenetic stability; excessive glutaminolysis drives effector expansion | High glutamine flux in RA FLS; αKG dysregulation affects Treg tolerance | [156,157,158] |

| One-Carbon Metabolism | SAM, SAH | SAM availability regulates DNA/histone methylation; SAM depletion causes global hypomethylation | Controls FOXP3 methylation status; impacts lineage fidelity | SAM:SAH imbalance seen in RA and SLE; influences T-cell differentiation | [159,160] |

| Redox/ROS Regulation | ROS, NAD⁺/NADH | ROS oxidizes 5mC → 5hmC; alters methylation fidelity; NAD⁺ levels dictate sirtuin activity | High ROS favors inflammatory programs; balanced redox supports regulatory phenotypes | Excess ROS in RA/SLE fuels inflammatory memory in T cells and macrophages | [161,162,163] |

| TCA Cycle Dysfunction | Succinate, fumarate | Succinate/fumarate inhibit αKG-dependent demethylases → hyperacetylated, pro-inflammatory chromatin | Enhances IL-1β, TNF expression and effector persistence | Elevated succinate in RA macrophages drives pathologic cytokine output | [44,164] |

| Mitochondrial Integrity & Mitophagy | PGC-1α, NAD⁺ | Healthy mitochondria support epigenetic precision; dysfunctional mitochondria increase ROS & chromatin noise | Supports Treg stability and prevents exhaustion; dysfunction drives inflammatory cell fate | Mitochondrial fragmentation in FLS and T cells reinforces chronic inflammation | [165,166,167] |

| Modality | Target Pathway (metabolic / epigenetic / cellular) | Mechanism of Tolerance Reprogramming | Disease Evidence | Stage (Preclinical / Phase I / Phase II / Clinical Use) | References |

| AMPK Activators (e.g., metformin, AICAR) | Metabolic | Restore OXPHOS, reduce glycolysis, lower ROS; support Treg survival and mitochondrial fitness | RA, SLE, vasculitis (immunometabolic and clinical data) | Clinical use (repurposed); formal tolerance-focused trials mostly Phase II / exploratory | [212,213] |

| NAD⁺ Boosters (NR, NMN, nicotinamide) | Metabolic | Increase NAD⁺ → enhance sirtuin activity; promote histone deacetylation; improve mitochondrial quality and regulatory-cell stability | Preclinical models of arthritis, lupus, and inflammatory aging | Preclinical; early human studies in metabolic/aging contexts | [214,215,216] |

| PPAR-γ Agonists (e.g., pioglitazone) | Metabolic | Reprogram lipid metabolism; suppress NF-κB; favor oxidative and anti-inflammatory phenotypes in immune and stromal cells | Experimental arthritis and fibrosis models; limited rheumatic clinical data | Clinical use in diabetes; preclinical/early translational in rheumatology | [215,217] |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Epigenetic | Increase histone acetylation at regulatory loci; enhance Treg function; compress inflammatory chromatin accessibility | Arthritis and lupus models; small early-phase human data | Preclinical and Phase I/II | [218,219] |

| BET Inhibitors | Epigenetic | Disrupt BRD4/super-enhancer complexes at TNF, IL6, CXCL loci; reduce sustained inflammatory transcription | Preclinical RA and tissue-inflammation models | Preclinical; some early oncology trials, limited immune-tolerance trials | [118,220,221] |

| EZH2 Inhibitors | Epigenetic | Reduce H3K27me3 at silenced regulatory genes (e.g., SOCS3, CDKN1A); relieve repression of tolerogenic programs | B cells and FLS in RA and SLE; strong preclinical rationale | Preclinical and early clinical (mainly oncology); rheumatic use exploratory | [119,222] |

| Low-Dose DNMT Inhibitors | Epigenetic | Partially reverse pathological DNA hypermethylation at tolerance genes; re-open FOXP3 and IL10 loci | Preclinical models of autoimmunity; conceptual alignment with epigenetic drift data | Preclinical; early clinical experience in oncology | [223,224] |

| CAR-Tregs | Cellular | Antigen-specific suppression at inflamed sites; stable FOXP3 expression and local IL-10/TGF-β delivery | Strong preclinical efficacy in arthritis, colitis, transplantation models | Preclinical; early Phase I trials in other immune contexts | [225,226] |

| Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells (tolDCs) | Cellular | Present self-antigen with low costimulation; induce and expand Tregs; dampen effector priming | Phase I/II trials in RA and other autoimmune diseases showing safety and biological activity | Phase I / Phase II | [227,228] |

| MSC-Based and EV-Based Therapies | Cellular / Paracrine | Deliver tolerogenic cytokines, metabolites, and miRNAs; remodel immune and stromal metabolic–epigenetic states | Early trials in RA, SLE, and systemic sclerosis; preclinical evidence of regulatory reprogramming | Phase I / Phase II; some compassionate/controlled clinical use | [229,230] |

| Nanoparticle-Targeted Metabolic/Epigenetic Agents | Delivery / Metabolic / Epigenetic | Cell- or tissue-specific delivery of metabolic/epigenetic drugs to synovium or lymphoid organs; limit systemic toxicity | Robust preclinical data in arthritis and systemic inflammation | Preclinical | [231,232] |

| Integrated Multi-omic / Digital-Twin–Guided Regimens | Systems / Computational | Use epigenomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic signatures to tailor and adapt tolerance-reprogramming therapies over time | Emerging computational and pilot translational studies | Conceptual and early translational; not yet in routine clinical practice | [233,234,235] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).