Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

| FOX Gene | Biological Process | Disease Association | Key Functions | References |

| FOXA1 | Organogenesis, hepatic development, pioneer transcription factor activity | Prostate cancer, breast cancer, metabolic disorders | Liver specification, pancreatic development, nuclear receptor cofactor | [17,18] |

| FOXA2 | Endodermal organ development, glucose homeostasis | Type 2 diabetes, pancreatic disorders, lung development defects | Pancreatic β-cell function, gluconeogenesis regulation, respiratory development | [19,20] |

| FOXA3 | Hepatic gene expression, metabolism | Cholangiocarcinoma, liver cancer, metabolic syndrome | Liver development, metabolic gene regulation, bile acid synthesis | [21] |

| FOXB1 | Neural development, cell proliferation | Glioblastoma, neural tube defects | Brain development, neural differentiation | [22] |

| FOXD1 | Kidney development, epithelial–mesenchymal transition | Pancreatic cancer, renal disorders | Kidney morphogenesis, EMT regulation, cancer metastasis | [23,24] |

| FOXD2 | Neural crest development | Developmental disorders | Neural crest cell migration, cranial development | [25,26,27] |

| FOXD3 | Neural crest development, stem cell maintenance | Melanoma, developmental disorders | Neural crest specification, stem cell pluripotency | [28,29] |

| FOXD4 | Embryonic development | Unknown pathological significance | Early development, recently duplicated in humans | [30] |

| FOXE1 | Thyroid development, neural development | Thyroid cancer, congenital hypothyroidism | Thyroid morphogenesis, neural tube closure | [31,32,33] |

| FOXF1 | Mesenchymal development, lung development | Alveolar capillary dysplasia, lung disorders | Lung development, angiogenesis | [34,35] |

| FOXF2 | Kidney development, angiogenesis | Renal disorders, vascular malformations | Kidney morphogenesis, vascular development | [36,37] |

| FOXG1 | Brain development, telencephalon formation | Autism spectrum disorders, Rett syndrome-like phenotype | Forebrain development, neurogenesis | [38,39] |

| FOXH1 | Mesoderm formation, nodal signaling | Developmental disorders, cardiac defects | Gastrulation, heart development, TGF-β signaling | [40] |

| FOXJ1 | Ciliogenesis, respiratory epithelium | Primary ciliary dyskinesia, respiratory infections | Cilia formation, respiratory function | [41] |

| FOXJ2 | Cell cycle regulation | Cancer | G2/M transition, DNA damage response | [41] |

| FOXJ3 | Cell cycle progression | Cancer progression | Mitotic regulation, chromosome segregation | [41] |

| FOXK1 | Muscle development, cell cycle | Muscular disorders, cancer | Myogenesis, proliferation control | [42] |

| FOXK2 | Muscle differentiation, metabolism | Metabolic disorders, muscle diseases | Skeletal muscle development, glucose metabolism | [43] |

| FOXL1 | Gastrointestinal development | Gastrointestinal cancers | Intestinal development, GI tract homeostasis | [44] |

| FOXL2 | Ovarian development, granulosa cell function | Ovarian cancer, premature ovarian failure | Ovarian follicle development, sex determination | [45] |

| FOXM1 | Cell cycle progression, DNA repair, mitosis | Multiple cancers, aging-related diseases | G1/S transition, M-phase progression, genomic stability | [46] |

| FOXN1 | Thymic development, hair follicle formation | Severe combined immunodeficiency, alopecia | T-cell development, skin differentiation | [47] |

| FOXN2 | Neural development | Neurodevelopmental disorders | Brain development, neuronal differentiation | [48] |

| FOXN3 | Cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response | Cancer, aging | Cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair | [49] |

| FOXN4 | Retinal development | Retinal disorders, blindness | Retinal neurogenesis, photoreceptor development | [50] |

| FOXO1 | Glucose homeostasis, stress response, apoptosis | Type 2 diabetes, cancer, metabolic syndrome | Gluconeogenesis, insulin sensitivity, cellular stress response | [51] |

| FOXO3 | Aging, stress resistance, apoptosis | Cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, longevity | Oxidative stress response, longevity pathways, apoptosis | [52] |

| FOXO4 | Cell cycle arrest, DNA damage response | Cancer, premature aging | p21 induction, senescence, DNA repair | [53] |

| FOXO6 | Brain function, glucose metabolism | Alzheimer's disease, diabetes | Memory consolidation, hepatic gluconeogenesis | [54] |

| FOXP1 | B-cell development, cardiac morphogenesis | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, intellectual disability | B-cell differentiation, heart valve development | [55] |

| FOXP2 | Language development, neural function | Speech and language disorders, autism | Speech acquisition, motor learning, synaptic plasticity | [56] |

| FOXP3 | Regulatory T-cell function, immune tolerance | Autoimmune diseases, IPEX syndrome, cancer | Treg development, immune suppression, self-tolerance | [57] |

| FOXP4 | T-cell development, cardiac function | Developmental disorders, cardiac defects | T-cell differentiation, heart development | [58] |

| FOXQ1 | Epithelial development | Colorectal cancer, gastric cancer | Epithelial homeostasis, EMT regulation | [59] |

| FOXR1 | Neural development | Cancer | Brain development, cell proliferation | [60,61] |

| FOXR2 | Neural function | Cancer | Neural development, transcriptional regulation | [62,63] |

| FOXS1 | Neural crest development | Developmental disorders | Cranial neural crest formation | [64] |

Experimental

Materials and Methods

Cell Isolation and Culture

Maternal Treatment

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

| Treatment Concentration | RNA Yield (ng/μL) |

| Control (0) | 328.0 |

| 1 pg/mL | 415.0 |

| 100 pg/mL | 353.3 |

| 1 ng/mL | 336.0 |

| 100 ng/mL | 353.2 |

| Gene | Primers | Amplicon Size | Annealing temperature | |

| FOXA1 | F | GCAATACTCGCCTTACGGCTCT | 129 | 65 |

| R | GGGTCTGGAATACACACCTTGG | |||

| FOXA2 | F | GGAACACCACTACGCCTTCAAC | 133 | 65 |

| R | AGTGCATCACCTGTTCGTAGGC | |||

| FOXA3 | F | CTCGCTGTCTTTCAACGACTGC | 122 | 65 |

| R | CGCAGGTAGCAGCCATTCTCAA | |||

| FOXB1 | F | CCACAACCTCTCCTTCAACGAC | 122 | 59 |

| R | AGGAAGCTGCCGTTCTCGAACA | |||

| FOXD1 | F | TGGTTCGGTGTTTTGTTCGC | 154 | 65 |

| R | AGCATAGGTCGGCTTTGCAT | |||

| FOXD2 | F | AACAGCATCCGCCACAACCTCT | 92 | 65 |

| R | CAGCGTCCAGTAGTTGCCCTTG | |||

| FOXD4 | F | CCACTAGCGTTCCTGCTTCT | 217 | 65 |

| R | TCATCTTCCTCCTCTCCCAGG | |||

| FOSD4L1 | F | TACATTTCAGCCTCCTGCCC | 204 | 53 |

| R | ACCTGCCACCAAGGAAGATG | |||

| FOXE1 | F | CTCTGCTCTGGTTGACCTGG | 103 | 65 |

| R | GGTTCAGGTGATGGGACTGG | |||

| FOXF1 | F | CAGGGCTGGAAGAACTCCG | 222 | 65 |

| R | GAAGCCGAGCCCGTTCAT | |||

| FOXF2 | F | CCTACCAGGGCTGGAAGAAC | 212 | 67 |

| R | CACGCGGTGGTACATGGG | |||

| FOXG1 | F | GAGGTGCAATGTGGGGAGAA | 197 | 65 |

| R | GTTCTCAAGGTCTGCGTCCA | |||

| FOXH1 | F | CCTGCCTTCTACACTGCCC | 151 | 62 |

| R | CTTCCTCCTCTTAGGGGGCT | |||

| FOXJ3 | F | TGATAGCCCACGCAGTAGCCTT | 154 | 67 |

| R | ACTGTGGTTGCTGCTGAGGAGT | |||

| FOXL1 | F | TCACGCTCAACGGCATCTACCA | 116 | 67 |

| R | TGACGAAGCAGTCGTTGAGCGA | |||

| FOXL2 | F | CAGTCAAGGAGCCAGAAGGG | 241 | 67 |

| R | CGGATGCTATTTTGCCAGCC | |||

| FOXO1 | F | GCCACATTCAACAGGCAGC | 251 | 65 |

| R | GACGGAAACTGGGAGGAAGG | |||

| FOXO4 | F | CCCGACCAGAGATCGCTAAC | 236 | 67 |

| R | AATGGCCTGGCTGATGAGTT | |||

| FOXP1 | F | CAAGCCATGATGACCCACCT | 252 | 67 |

| R | GGGCACGTTGTATTTGTCTGA | |||

| FOXB2 | F | CGACTGCTTCATCAAGATTCCGC | 104 | 59 |

| R | AGGAAGCTGCCGTTCTCGAACA | |||

| FOXC1 | F | CAGTCTCTGTACCGCACGTC | 189 | 65 |

| R | TGTTCGCTGGTGTGGTGAAT | |||

| FOXC2 | F | GCAGTTACTGGACCCTGGAC | 211 | 65 |

| R | ATCACCACCTTCTTCTCGGC | |||

| FOXD3 | F | AAGCCGCCTTACTCGTACATCG | 159 | 65 |

| R | AGAGGTTGTGGCGGATGCTGTT | |||

| FOXE3 | F | CTTCATCACCGAACGCTTTGCC | 144 | 65 |

| R | CAGCGTCCAGTAGTTGCCCTTG | |||

| FOXI1 | F | GGAGCCTCAGGACATCTTGG | 135 | 47 |

| R | CCGCTCACATAGGCTGTCAT | |||

| FOXI2 | F | CGTGGCTGGTAACTTCCCTT | 211 | 65 |

| R | GGCTTCAGCTCTCCTCTTCC | |||

| FOXI3 | F | AACTCCATCCGCCACAACCTGT | 107 | 62 |

| R | CTCGCAGTTCGGATCAAGAGTC | |||

| FOXJ1 | F | ACTCGTATGCCACGCTCATCTG | 152 | 50 |

| R | GAGACAGGTTGTGGCGGATTGA | |||

| FOXJ2 | F | ACCAGTGGCAAACAGGAGTCAG | 131 | 67 |

| R | TGGGCGATTGTATCCTGCTGAG | |||

| FOXK1 | F | GCCGACAAAGGCTGGCAGAATT | 129 | 65 |

| R | TGGCTTCAGAGGCAGGGTCTAT | |||

| FOXK2 | F | CCAAACTCGCTGTCATCCAGGA | 126 | 59 |

| R | GTGTAGGTGACAGGCTTGATGG | |||

| FOXM1 | F | AGCAGCGACAGGTTAAGGTT | 225 | 62 |

| R | TGTGGCGGATGGAGTTCTTC | |||

| FOXN1 | F | GAGGTCAAAGTCAAGCCCCC | 301 | 65 |

| R | TGTAGATCTCGCTGACGGGA | |||

| FOXN2 | F | ACAGATGCAGAGGGCTGACT | 248 | 65 |

| R | GGCAGCATCAACAGCTTCAG | |||

| FOXN3 | F | GCCCTTCTCCAAGTTCCTCC | 136 | 59 |

| R | AGCTGGTGATGCCATTCCTC | |||

| FOXN4 | F | GGCCACAGAGACAGCATGAG | 236 | 47 |

| R | TTGGGGTAGTGTTTGGGGTG | |||

| FOXO3 | F | CGTCTTCAGGTCCTCCTGTT | 135 | 47 |

| R | GGGAAGCACCAAAGAAGAGAG | |||

| FOXO6 | F | GAAGAACTCCATCCGGCACA | 124 | 65 |

| R | CGGGGTCTTCCCTGTCTTTC | |||

| FOXP2 | F | CAAGCCATGATGACCCACCT | 276 | 62 |

| R | CTGCGCAATATCTGCTGACG | |||

| FOXP3 | F | CCCACTTACAGGCACTCCTC | 254 | 65 |

| R | GGGATTTGGGAAGGTGCAGA | |||

| FOXP4 | F | GCCAAGCAGCCCACAAAG | 277 | 62 |

| R | AGATGGAGCCGACCTGATTG | |||

| FOXQ1 | F | AACCCCTCCTGGGCTCTTTA | 199 | 65 |

| R | GTGTTGGGTGGACTATGGGG | |||

| FOXR1 | F | CAGTCCTCCAGCAAGCGGTCT | 113 | 50 |

| R | AGCCATAGAGGAGCTGTCTTCC | |||

| FOXR2 | F | AAAGTCGCACGAGGAGAGTG | 209 | 67 |

| R | CTCGAGGTTCTCCATGGCTC | |||

| FOXS1 | F | ATCCGCCACAACCTGTCACTCA | 129 | 65 |

| R | GTAGGAAGCTGCCGTGCTCAAA | |||

| GAPDH | F | GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG | 186 | 60 |

| R | ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA |

Quantitative PCR Analysis

Results

Metadichol Induces Dose-Dependent Changes in FOX Gene Expression

| Cell line | Markers | Control | 1 pg/ml | 100 pg/ml | 1 ng/ml | 100 ng/ml |

| PBMC | FOXA1 | 1 | 3.56 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 7.39 |

| FOXA2 | 1 | 1.1 | 2.25 | 0.16 | 6.57 | |

| FOXA3 | 1 | 1.24 | 1.81 | 0.12 | 6.98 | |

| FOXB1 | 1 | 3.16 | 1.01 | 0.3 | 6.79 | |

| FOXD1 | 1 | 0.31 | 4.34 | 0.83 | 1.1 | |

| FOXD2 | 1 | 6.36 | 1.83 | 0.15 | 1.38 | |

| FOXD4 | 1 | 4.67 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 1.36 | |

| FOXD4L1 | 1 | 1.93 | 1.36 | 0.2 | 0.56 | |

| FOXE1 | 1 | 1.64 | 1.66 | 0.15 | 1.43 | |

| FOXF1 | 1 | 1.01 | 0.59 | 0.2 | 2.41 | |

| FOXF2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 1.47 | |

| FOXG1 | 1 | 6.26 | 3.23 | 0.45 | 3.04 | |

| FOXH1 | 1 | 3.09 | 1.49 | 0.55 | 7.22 | |

| FOXJ3 | 1 | 4.02 | 1.09 | 0.4 | 4.24 | |

| FOXL1 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.54 | |

| FOXL2 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.16 | |

| FOXO1 | 1 | 2.51 | 0.96 | 0.27 | 8.74 | |

| FOXO4 | 1 | 0.56 | 1.11 | 0.49 | 0.84 | |

| FOXP1 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.16 | 0.84 | 2.28 | |

| FOXB2 | 1 | 0.2 | 1.41 | 0.22 | 2.58 | |

| FOXC1 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.15 | 2.16 | |

| FOXC2 | 1 | 0.08 | 1.33 | 0.09 | 2.4 | |

| FOXD3 | 1 | 0.12 | 2.63 | 0.11 | 1 | |

| FOXE3 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.75 | 0.6 | 1.49 | |

| FOXI1 | 1 | 0.19 | 5.73 | 0.22 | 1.91 | |

| FOXI2 | 1 | 0.36 | 2.41 | 0.2 | 4.15 | |

| FOXI3 | 1 | 0.17 | 1.16 | 0.22 | 2.74 | |

| FOXJ1 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.7 | |

| FOXJ2 | 1 | 0.77 | 1.57 | 0.54 | 0.98 | |

| FOXK1 | 1 | 0.43 | 2.89 | 0.31 | 1.07 | |

| FOXK2 | 1 | 0.25 | 1.47 | 0.28 | 1.84 | |

| FOXM1 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 4.54 | |

| FOXN1 | 1 | 0.56 | 5.95 | 0.73 | 0.79 | |

| FOXN2 | 1 | 0.15 | 1.69 | 0.17 | 2.77 | |

| FOXN3 | 1 | 0.16 | 1.13 | 0.23 | 1.72 | |

| FOXN4 | 1 | 0.1 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 1.2 | |

| FOXO3 | 1 | 0.38 | 1.58 | 0.3 | 1.23 | |

| FOXO6 | 1 | 0.12 | 1.53 | 0.15 | 0.56 | |

| FOXP2 | 1 | 0.41 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 5.15 | |

| FOXP3 | 1 | 1.48 | 1.38 | 0.21 | 5.46 | |

| FOXP4 | 1 | 0.95 | 2.85 | 1.39 | 6.23 | |

| FOXQ1 | 1 | 0.14 | 1.25 | 0.09 | 2.18 | |

| FOXR1 | 1 | 0.13 | 1.45 | 0.16 | 3.1 | |

| FOXR2 | 1 | 0.23 | 1.38 | 0.27 | 2.11 | |

| FOXS1 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.1 | 3.36 |

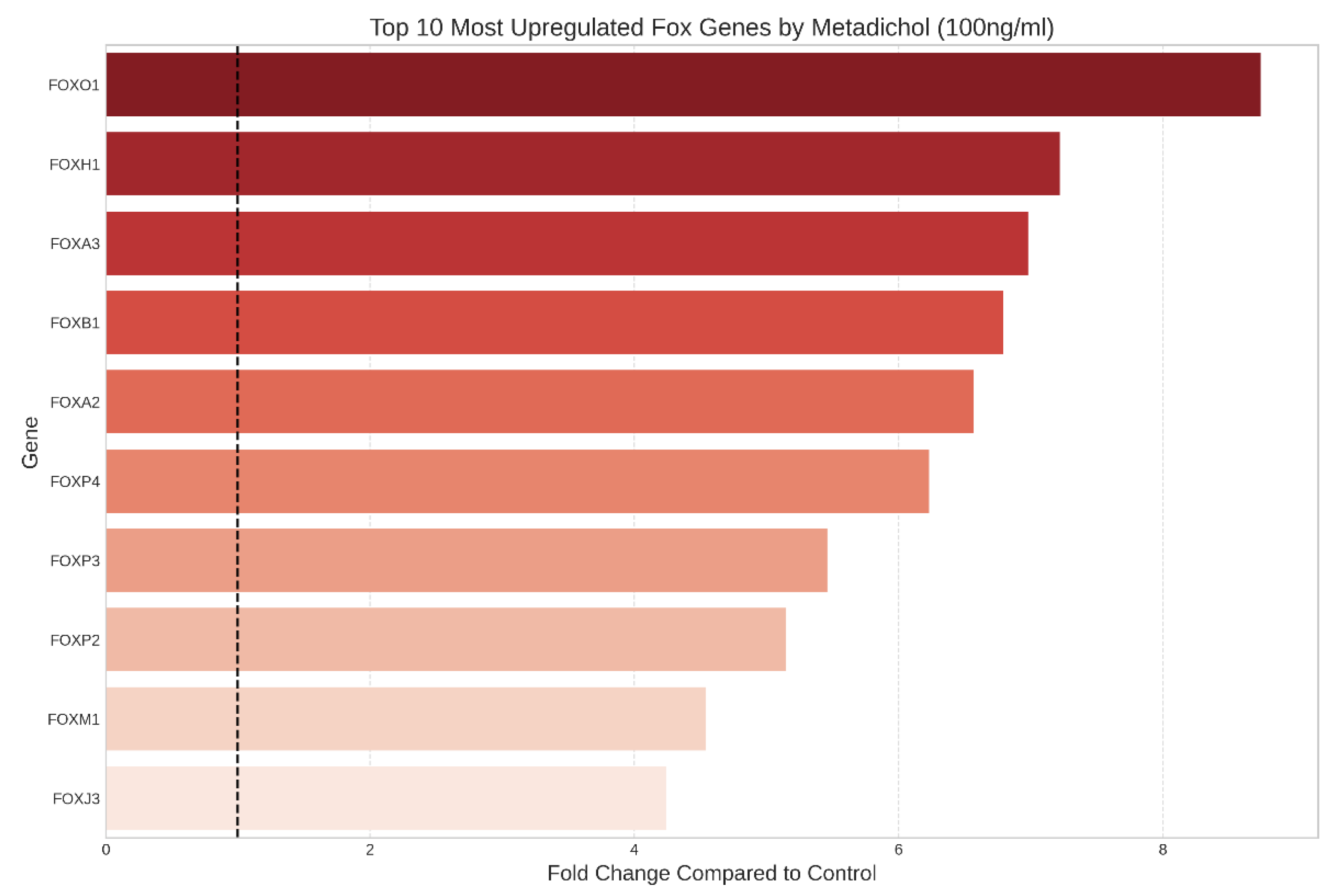

Identification of the most highly responsive FOX genes

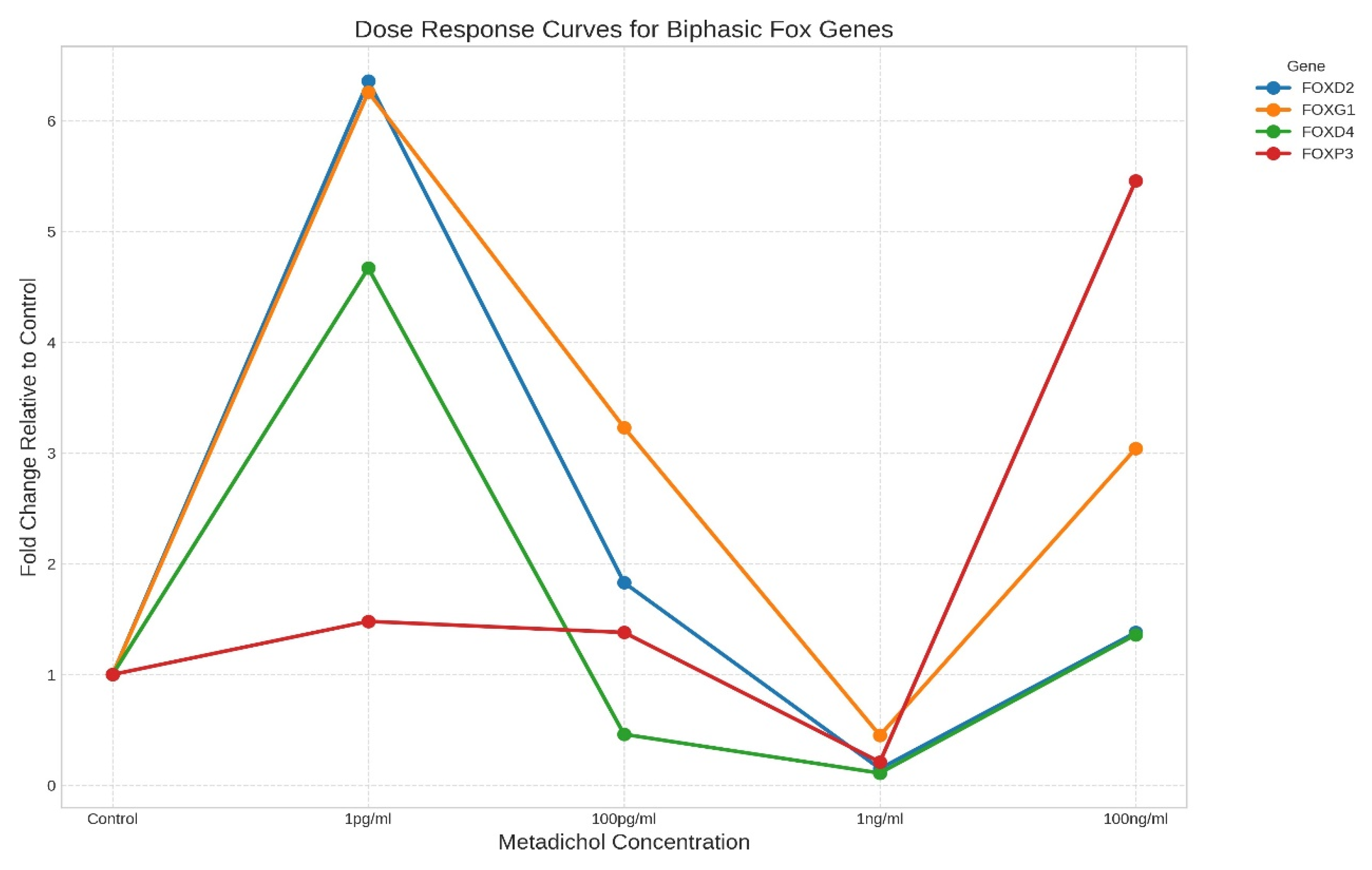

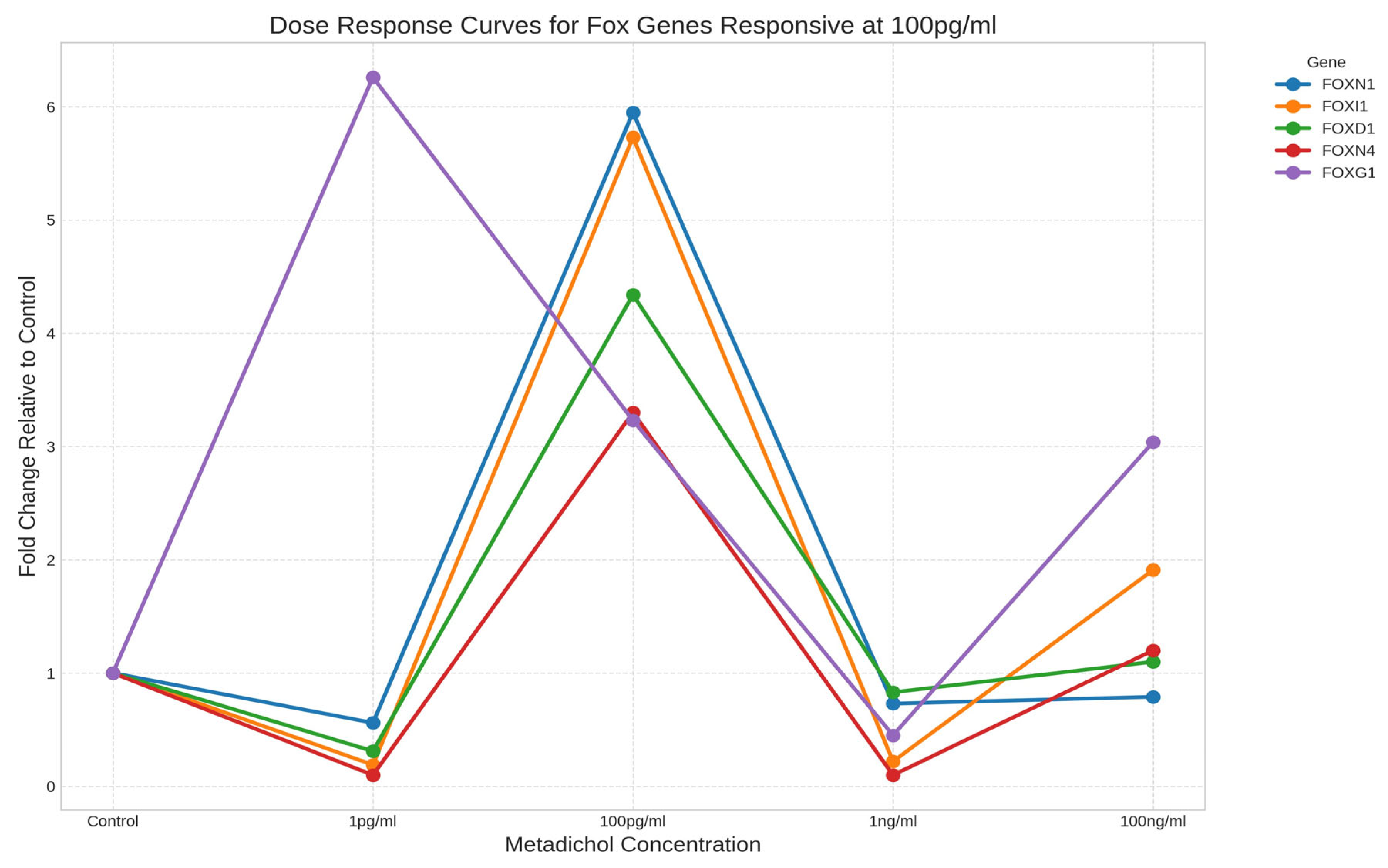

Distinct Dose‒Response Patterns Reveal Gene-Specific Regulation

- High-concentration responders: Genes whose expression was primarily upregulated at 100 ng/ml, with minimal responses at lower concentrations (e.g., FOXO1, FOXH1, FOXA3)

- Biphasic/hormetic responders: Genes whose expression was elevated at both low (1 pg/ml) and high (100 ng/ml) concentrations but whose expression was reduced at intermediate concentrations (Figure 3). Key examples include FOXD2, FOXG1, FOXD4, and FOXP3. This U-shaped response suggests complex, concentration-dependent regulatory mechanisms.

- Intermediate-concentration responders: Genes exhibiting peak expression at the intermediate concentration of 100 pg/ml, including FOXN1 (5.95-fold), FOXI1 (5.73-fold), FOXD1 (4.34-fold), and FOXN4 (3.30-fold).

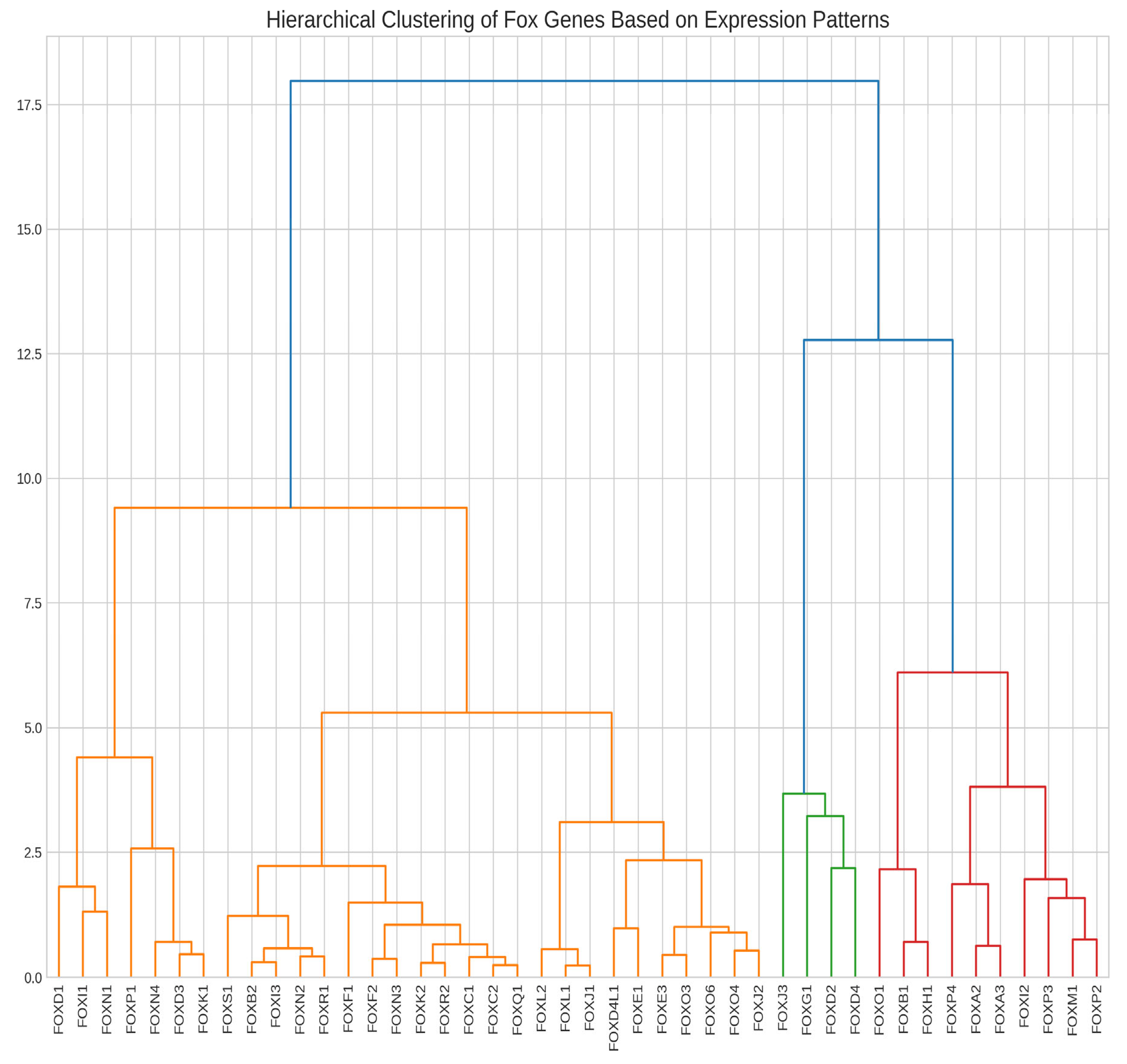

Hierarchical Clustering Reveals Coordinated Gene Expression Patterns

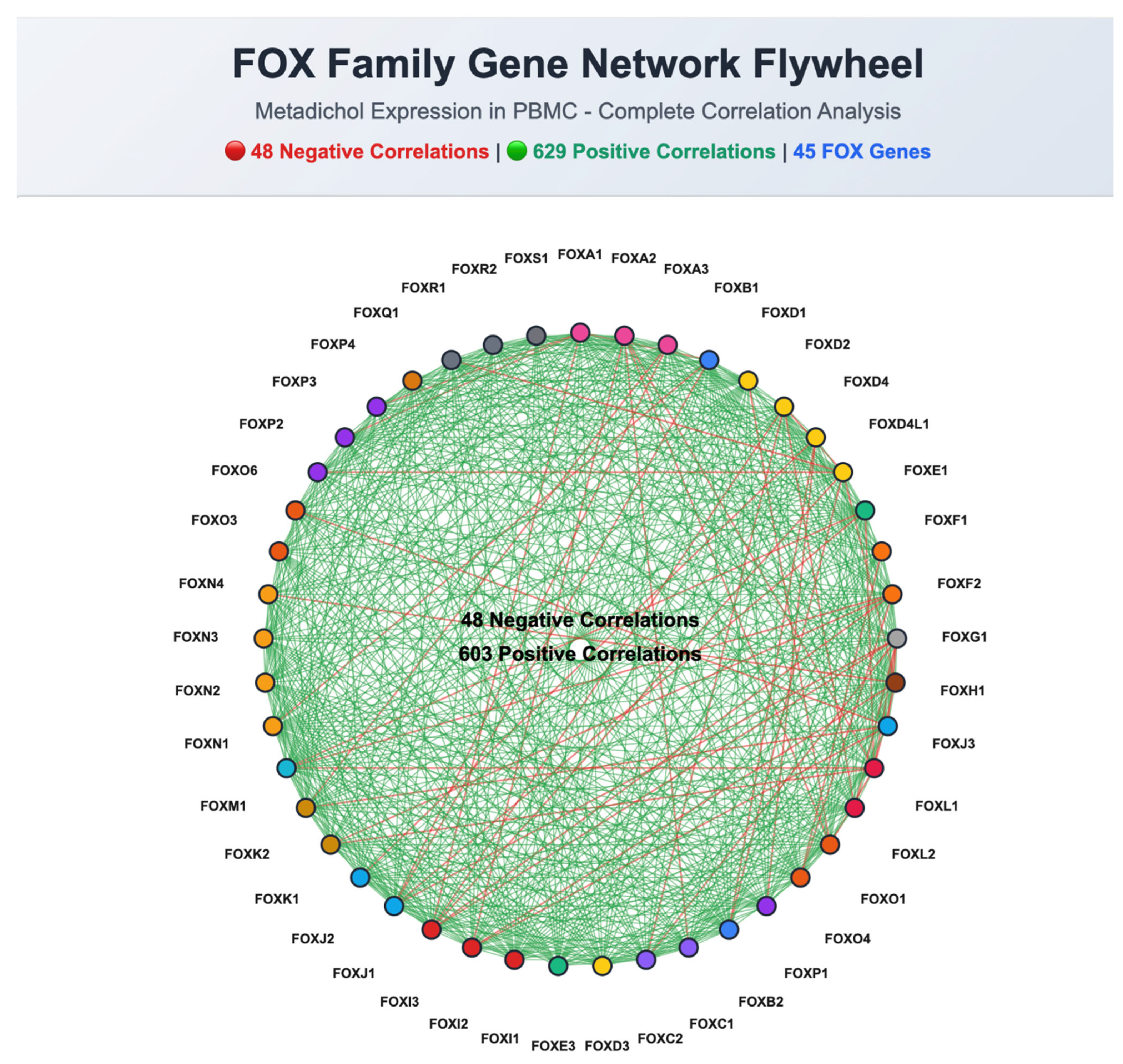

Correlation Analysis Identifies Highly Coordinated Gene Pairs

Significantly Upregulated FOX Genes

Downregulated FOX Genes

Family-Specific Response Patterns

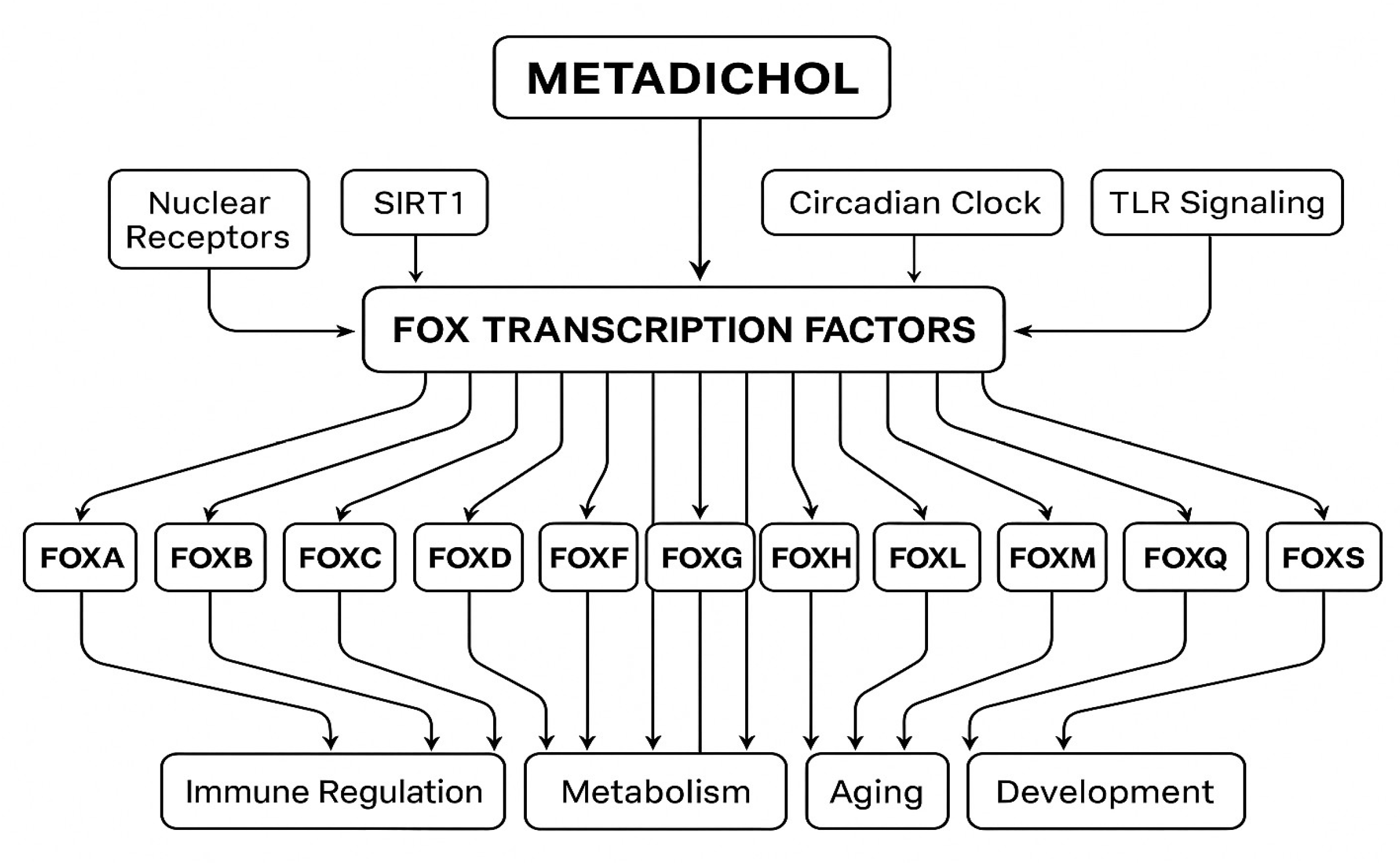

Discussion

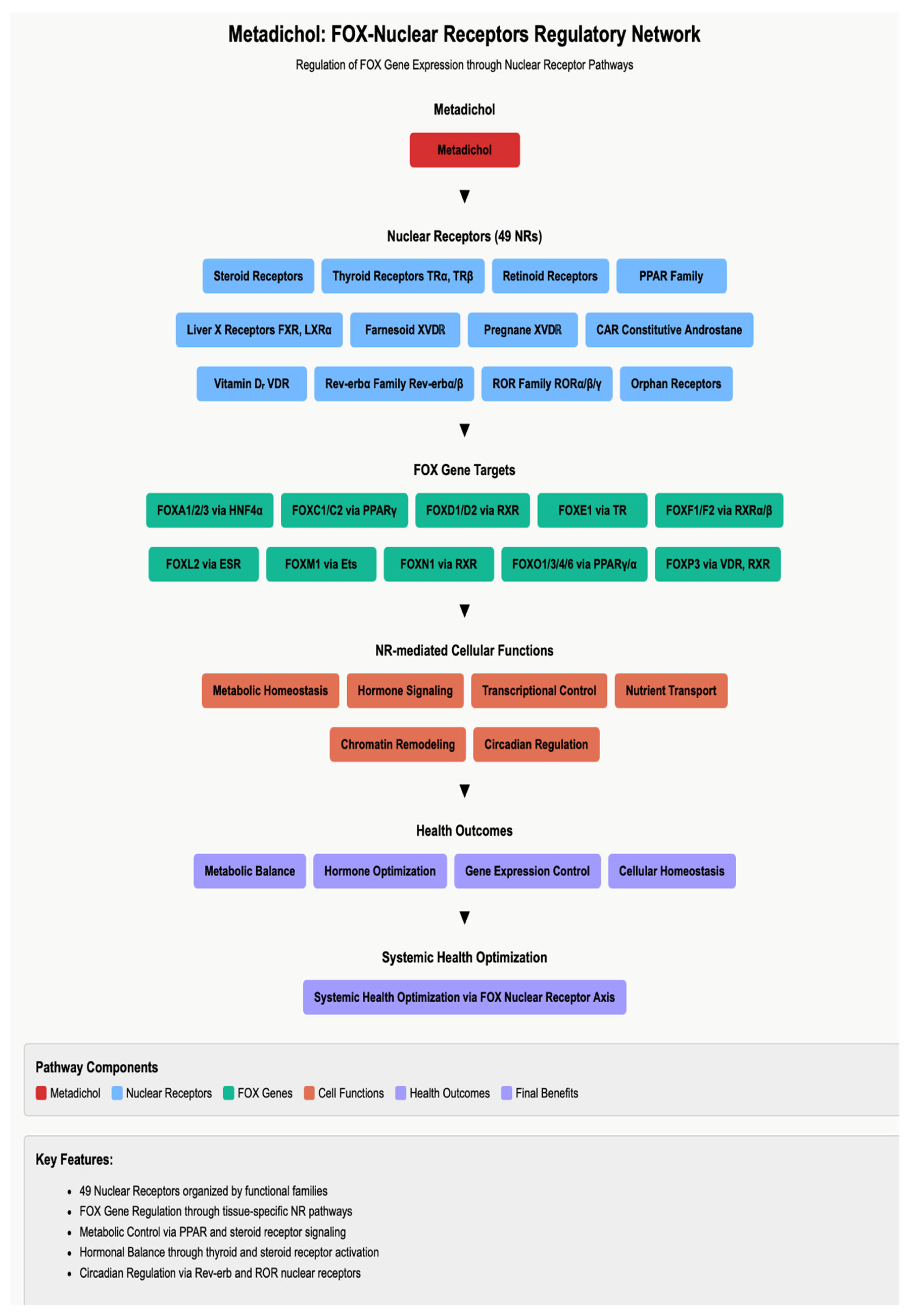

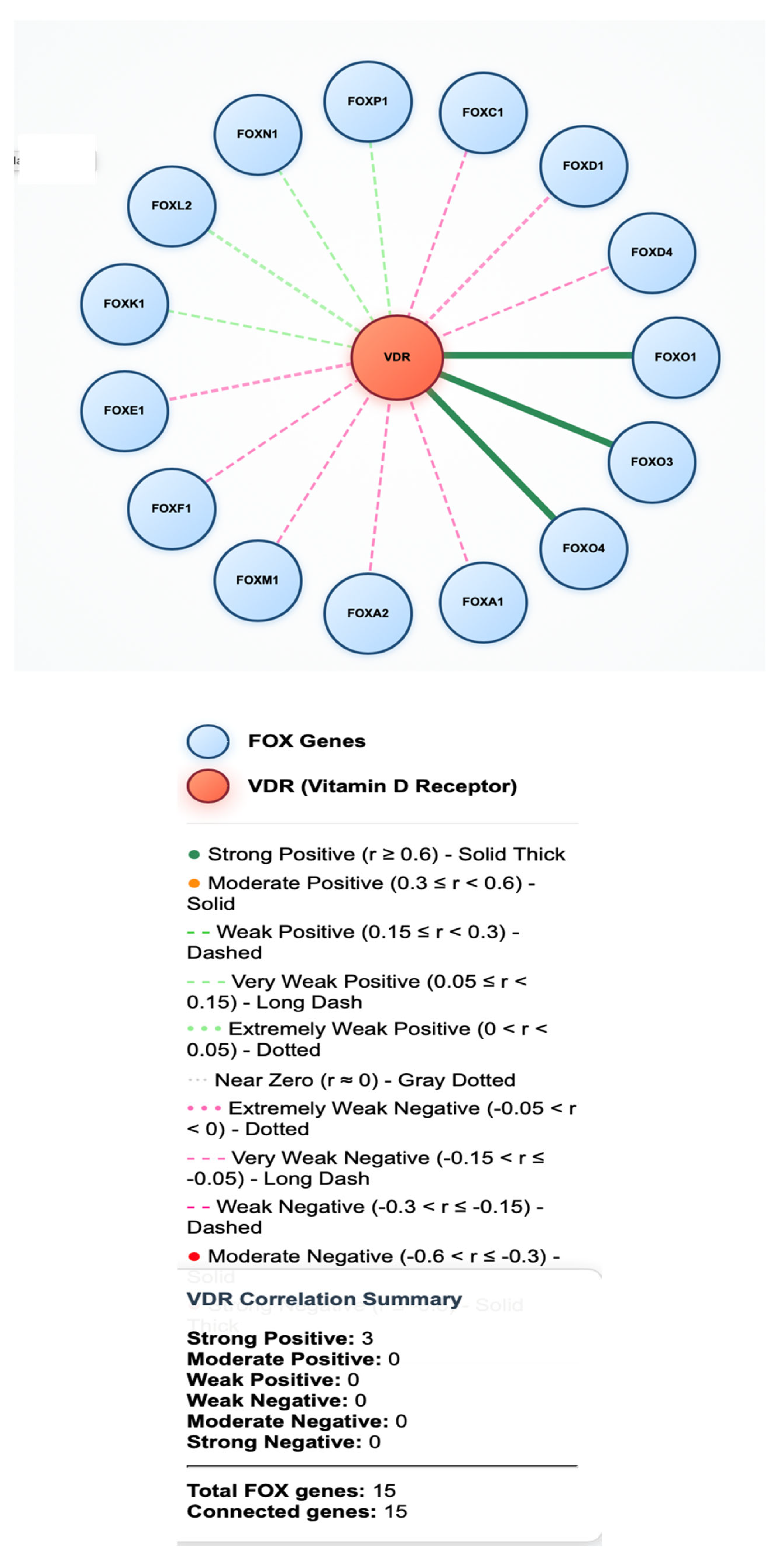

Nuclear Receptor-Mediated FOX Gene Regulation

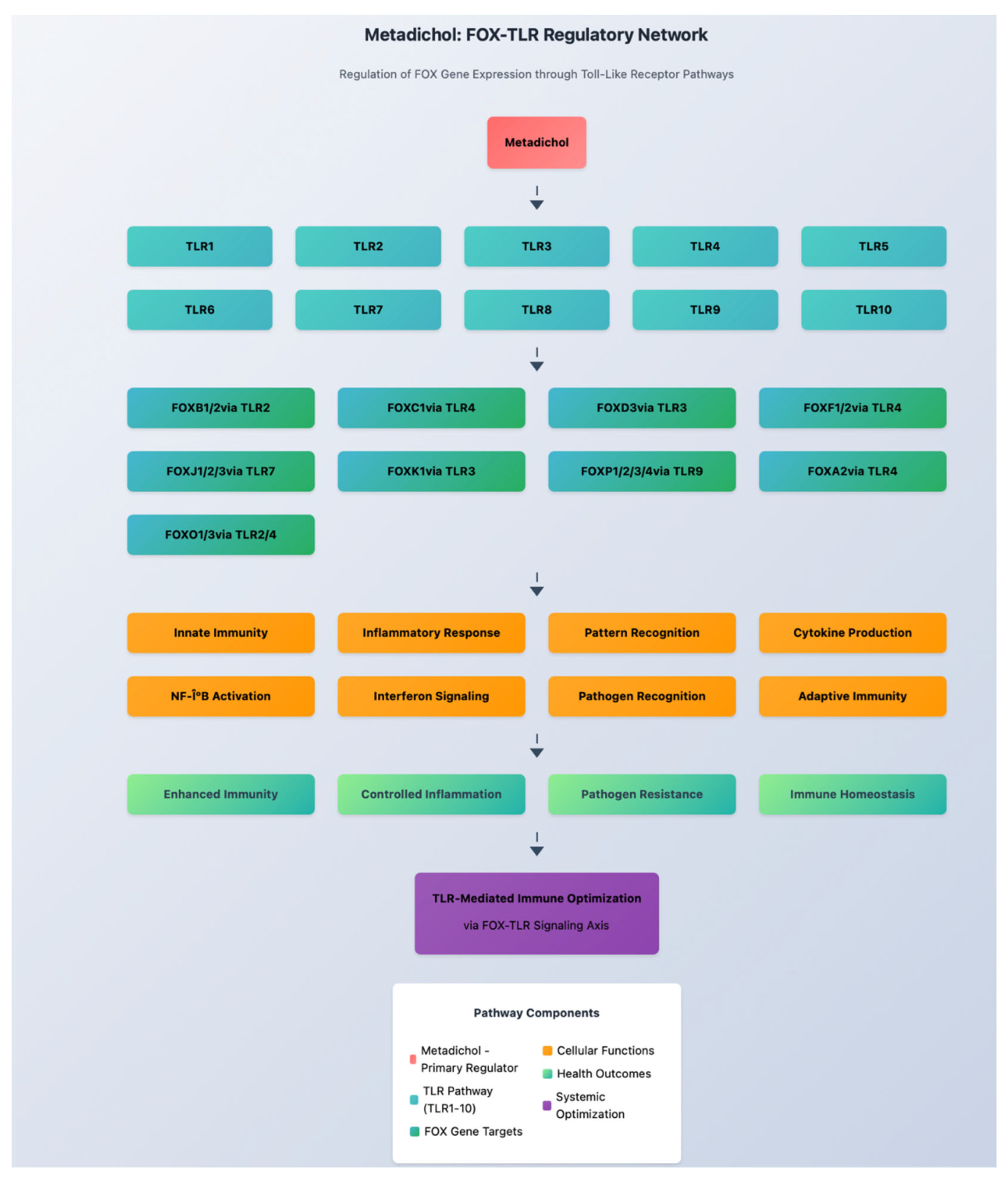

Toll-like Receptor Signaling and FOX Regulation

SIRT1-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation

Krüppel-like Factor Interactions

Circadian Clock Gene Regulation

Klotho-Mediated Anti-Aging Pathways

FOX and Anti-Aging Factors

Telomerase and Cellular Senescence

Growth Differentiation Factor 11 (GDF11) Signaling

Conclusions

Supplementary Information

References

- Hannenhalli S, Kaestner KH. The evolution of Fox genes and their role in development and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(4):233-240. [CrossRef]

- Katoh M, Igarashi M, Fukuda H, Nakagama H, Katoh M. Cancer genetics and genomics of human FOX family genes. Cancer Lett. 2013;328(2):198-206. [CrossRef]

- Coffer PJ, Burgering BM. Forkhead-box transcription factors and their role in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(11):889-899. [CrossRef]

- Friedman JR, Kaestner KH. The Foxa family of transcription factors in development and metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(19-20):2317-2328. [CrossRef]

- Kaestner KH. The FoxA factors in organogenesis and differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20(5):527-532. [CrossRef]

- Zaal A, Nota B, Moore KS, et al. TLR4 and C5aR crosstalk in dendritic cells induces a core regulatory network of RSK2, PI3Kβ, SGK1, and FOXO transcription factors. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102(4):1035-1054. [CrossRef]

- Tia N, Singh AK, Pandey P, et al. Role of Forkhead Box O (FOXO) transcription factor in aging and diseases. Gene. 2018;648:97-105. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhou Y, Graves DT. FOXO transcription factors: their clinical significance and regulation. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:925350. [CrossRef]

- Clark KL, Halay ED, Lai E, Burley SK. Cocrystal structure of the HNF-3/fork head DNA- recognition motif resembles histone H5. Nature. 1993;364(6436):412-420. [CrossRef]

- Laissue P. The forkhead-box family of transcription factors: key molecular players in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda M, Hollander P, Mani SA. Forkhead box transcription factors: double-edged swords in cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82(11):2057-2065. [CrossRef]

- Jiramongkol Y, Lam EW. FOXO transcription factor family in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39(3):681-709. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Wang A, Xue M, et al. FOXA1 and FOXA2: the regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):76. [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Barbi J, Pan F. The regulation of immune tolerance by FOXP3. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(11):703-717. [CrossRef]

- Maiese K. Targeting the core of neurodegeneration: FoxO, mTOR, and SIRT1. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16(3):448-455. [CrossRef]

- Afanas'ev I. Reactive Oxygen Species and Age-Related Genes p66Shc, Sirtuin, FoxO3 and Klotho in Senescence. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3(2):77-85. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ma XL, Wang Y, et al. FOXA1: A Pioneer of Nuclear Receptor Action in Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:8533709.

- Zhao S, Zeng Y, Liao Y, et al. FOXA1 and FOXA2: the regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic implications in steroid hormone-induced malignancies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:11009302.

- Yánez DC, Lau CI, Papaioannou E, et al. The Pioneer Transcription Factor Foxa2 Modulates T Helper Differentiation to Reduce Mouse Allergic Airway Disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:890781. [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Kim H, Park JW. Haploinsufficiency of the FOXA2 associated with a complex clinical phenotype. Front Genet. 2020;11:7284027.

- Vera S, Zaragoza C, Aranda JF, et al. FOXA3 Polymorphisms Are Associated with Metabolic Parameters in Individuals With and Without Subclinical Atherosclerosis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(4):441.

- Shao Z, Mak SH, Wang H, et al. Foxb1 Regulates Negatively the Proliferation of Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells and Promotes Their Differentiation. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:5496944. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Yang L, Liu Y, et al. FOXD1 is a prognostic biomarker and correlated with macrophages infiltration in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(13):8255535. [CrossRef]

- Berenguer M, Fernández-Sánchez N, Aguirre M, et al. Association of FOXD1 variants with adverse pregnancy outcomes in Southern Europeans. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0163673. [CrossRef]

- Long Y, Jin L, Fu Y, et al. Forkhead box protein D2 suppresses colorectal cancer by transactivating p53-responsive genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(9):5052-5069. [CrossRef]

- Ruf R, Kousorn P, Larsen CK, et al. Implication of FOXD2 dysfunction in syndromic congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract via WNT signaling. Kidney Int. 2023;103(4):847-849. [CrossRef]

- Wang XC, et al. Upregulation of lnc-FOXD2-AS1, CDC45, and CDK1 in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology. 2024;29(2):e1539.

- Vasudevan S, Choi M, Boothe T, et al. Emerging Roles and Mechanisms of lncRNA FOXD3- AS1 in Human Diseases: A Review. Front Oncol. 2022;12:8914342.

- Teng Y, Wu X, Wu Y, et al. Requirement for Foxd3 in maintenance of neural crest progenitors. Dev Biol. 2008;314(2):473-486. [CrossRef]

- Sherman LS, Ye D, Merzdorf CS. Foxd4 is essential for establishing neural cell fate and for neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2017;80:37-49. [CrossRef]

- Landa I, Ruiz-Llorente S, Montero-Conde C, et al. The Variant rs1867277 in FOXE1 Gene Confers Thyroid Cancer Susceptibility Through the Recruitment of USF1/USF2 Transcription Factors. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(9):e1000637. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Fariñas M, Du J, Wang Z, et al. Reduced expression of FOXE1 in differentiated thyroid cancer, the role of DNA methylation in T and NT tissues. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:11586194.

- Yu X, Liu R, Li X, et al. Exploration of the association between FOXE1 gene polymorphism and differentiated thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19:100. [CrossRef]

- Dharmadhikari AV, Lopes F, Hamosh A, et al. Genomic and epigenetic complexity of the FOXF1 locus in 16q24.1: implications for development and disease. Hum Genet. 2015;134(7):749-768.

- Stankiewicz P, Sen P, Bhatt SS, et al. Analysis of FOXF1 and the FOX gene cluster in patients with VACTERL association. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(2):273-280. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wang Y, Wu Y, et al. The regulatory roles and mechanisms of the transcription factor FOXF2 in health and disease. Cancer Lett. 2021;498:195-207. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Zhu X, Harada S, et al. Foxf2 plays a dual role during transforming growth factor beta-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibrosis of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):1043. [CrossRef]

- Kortüm F, Caputo V, Bauer CK, et al. FOXG1-Related Disorders: From Clinical Description to Molecular Mechanisms. Brain Dev. 2011;33(10):813-823. [CrossRef]

- Mitter D, Denecke J, Kresimon J, et al. FOXG1 syndrome. GeneReviews®. 2025 May 1; PMID: 31514244.

- Hoodless PA, Pye M, Chazaud C, et al. FoxH1 (Fast) functions to specify the anterior primitive streak in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2001;15(10):1257-1271. [CrossRef]

- Pan W, Hsu Y, Wang Y, et al. The role of Forkhead box family in bone metabolism and diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:772237. [CrossRef]

- Tkatchenko TV, Visel A, Thompson CL, et al. FoxK1 associated gene regulatory network in hepatic insulin action. Mol Metab. 2023;70:101748. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Liu S, Li S, Hu S, Lin J, Mo X. FOXK2 transcription factor and its roles in tumorigenesis (Review). Oncol Lett. 2022;24(6):433. [CrossRef]

- Yang G, Li W, Si T, et al. FOXL1 regulates lung fibroblast function via multiple mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63(4):468-479. [CrossRef]

- Laissue P. The Genetic and Clinical Features of FOXL2-Related Disorders: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):2442. [CrossRef]

- Myatt SS, Lam EW. The emerging roles of forkhead box (Fox) proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(11):847-859. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya HJ, Briones Leon A, Blackburn CC. FOXN1 in thymus organogenesis and development. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(8):1826-1837. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yan C, Li J, et al. FOXN2 inhibits breast cancer progression by suppressing EMT and stemness via inactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(11):472.

- Wang C, Qiu J, Chen M, et al. Novel tumor-suppressor FOXN3 is downregulated in adult acute myeloid leukemia and suppresses tumor cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in vitro. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(2):1044-1054.

- Li S, Mo Z, Yang X, Price SM, Shen MM, Xiang M. Foxn4 controls the genesis of amacrine and horizontal cells by retinal progenitors. Neuron. 2004;43(6):795-807. [CrossRef]

- Liong S, Mu T, Wang G, Jiang X. A Review of FoxO1-Regulated Metabolic Diseases and Related Drug Discoveries. Cells. 2020;9(1):184. [CrossRef]

- Willcox BJ, Donlon TA, He Q, et al. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):13987-13992. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Liu S, Ma Q, et al. Current perspective on the regulation of FOXO4 and its role in disease and metabolic regulation. Exp Cell Res. 2019;381(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- van der Heide LP, Jacobs FM, Burbach JP, Hoekman MF, Smidt MP. FoxO6 transcriptional activity is regulated by Thr26 and Ser184, independent of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Biochem J. 2005;391(Pt 3):623-629. [CrossRef]

- Hisaoka T, Nakamura Y, Senba E. FOXP1: A novel player in neurodevelopmental disorders, including FOXP1 syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2022;67(2):79-90. [CrossRef]

- Fisher SE, Scharff C. FOXP2 as a molecular window into speech and language. Trends Genet. 2009;25(4):166-177. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133(5):775-787. [CrossRef]

- Bonkowski MS, Sinclair DA. FOXP genes: Guardians of tissue identity. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(11):1181-1182. [CrossRef]

- Kaneda H, Arao T, Tanaka K, et al. FOXQ1 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and enhances invasion ability. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(4):541-551. [CrossRef]

- Santo EE, Ebus ME, Koster J, et al. Oncogenic activation of FOXR1 by 11q23 intrachromosomal deletion-fusions in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2012;31(8):928-936. [CrossRef]

- Mota A, Waxman HK, Hong R, et al. FOXR1 regulates stress response pathways and is necessary for proper brain development. PLoS Genet. 2021;17(11):e1009854. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Zhang Y, Kim S, et al. FOXR2 interacts with MYC to promote its transcriptional activities and oncogenic transformation. Cancer Res. 2016;76(12):3471-3482.

- Wang Y, Chen C, Lohr J, et al. FOXR2 Stabilizes MYCN Protein and Identifies non–MYCN- amplified Neuroblastoma Patients With Unfavorable Outcome. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(12):e148076.

- Lin S, Wu R, Zhu X, et al. Pan-Cancer Analysis Predicts FOXS1 as a Key Target in Prognosis and Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:844558.

- Bernardo GM, Keri RA. FOXA1: a transcription factor with parallel functions in development and cancer. Biosci Rep. 2012;32(2):113-130. [CrossRef]

- Grabowska MM, Elliott AD, DeGraff DJ, et al. NFI transcription factors interact with FOXA1 to regulate prostate-specific gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(6):949-964. [CrossRef]

- Lee CS, Friedman JR, Fulmer JT, Kaestner KH. The initiation of liver development is dependent on Foxa transcription factors. Nature. 2005;435(7044):944-947. [CrossRef]

- Domanskyi A, Alter H, Vogt MA, et al. Transcription factors Foxa1 and Foxa2 are required for adult dopamine neurons maintenance. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:275. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Y, Khanna S, Grzenda AL, et al. Polycomb antagonizes p300/CREB-binding protein- associated factor to silence FOXP3 in a Kruppel-like factor-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(13):10021-10031. [CrossRef]

- Hedrick SM, Michelini RH, Doedens AL, Goldrath AW, Stone EL. FOXO transcription factors throughout T-cell biology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(9):649-661. [CrossRef]

- Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303(5666):2011-2015. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang W, Beckett O, Flavell RA, Li MO. An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T-cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30(3):358-371. [CrossRef]

- Konopacki C, Pritykin Y, Rubtsov Y, et al. Transcription factor Foxp1 regulates Foxp3 chromatin binding and coordinates regulatory T-cell function. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(2):232-242. [CrossRef]

- Harada Y, Harada Y, Elly C, et al. Transcription factors Foxo3a and Foxo1 couple the E3 ligase Cbl-b to the induction of Foxp3 expression in induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207(7):1381-1391. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan PR. Policosanol Nanoparticles. US patents 8,722,093 (2014) , 9,006,292(2015).

- Raghavan PR. VDR inverse agonism by metadichol enhances VDBP-mediated immunity. Preprints.org. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan PR. Inhibition of Dengue and other enveloped viruses by Metadichol®, a novel Nano emulsion Lipid. J Sci Heal Outcomes. 2016;14(2):8-17.

- Raghavan PR. In vitro inhibition of zika virus by Metadichol®, a novel nano emulsion lipid. J Immunol Tech Infect Dis. 2016;5:4.

- Raghavan PR. Metadichol®: A Novel Nanolipid Formulation That Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 and a Multitude of Pathological Viruses In Vitro. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:1558860. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan PR. Metadichol® induced high levels of vitamin C: case studies. Vitam Miner. 2017;6:1-7.

- Raghavan PR. The Quest for Immortality: Introducing Metadichol® a Novel Telomerase Activator. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;9:446.

- Raghavan PR. Metadichol Modulates the DDIT4-mTOR-p70S6K Axis: A Novel Therapeutic Strategy for mTOR-Driven Diseases. Preprints. 2025;2025041573.

- Boyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1968;21:77-89. [CrossRef]

- Morgan DM, Ruscetti FW. T lymphocyte colony formation in agar medium. J Immunol. 1970;104(5):1130-1136.

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol‒chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162(1):156-159. [CrossRef]

- Freeman WM, Walker SJ, Vrana KE. Quantitative RT‒PCR: pitfalls and potential. Biotechniques. 1999;26(1):112-125. [CrossRef]

- Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25(2):169-193. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-408. [CrossRef]

- Pike JW, Meyer MB, Lee SM, et al. The vitamin D receptor: contemporary genomic approaches reveal new basic and translational insights. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(4):1146-1154. [CrossRef]

- Michalik L, Auwerx J, Berger JP, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(4):726-741. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Ross-Innes CS, Schmidt D, Carroll JS. FOXA1 is a key determinant of estrogen receptor function and endocrine response. Nat Genet. 2011;43(1):27-33. [CrossRef]

- Pike JW, Meyer MB. The vitamin D receptor: new paradigms for the regulation of gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):255-269. [CrossRef]

- Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, et al. Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell. 2005;122(1):33-43. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Villalta SA, Agrawal DK. FOXO1 mediates vitamin D deficiency-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;164:25-30. [CrossRef]

- Laganière J, Deblois G, Lefebvre C, et al. Location analysis of estrogen receptor alpha target promoters reveals that FOXA1 defines a domain of the estrogen response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S 2005;102(33):11651-11656. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Gong H, Khadem S, et al. PPAR-β/δ agonism upregulates forkhead box A2 to reduce inflammation in C2C12 myoblasts and in skeletal muscle. Front Physiol. 2020;11:222. [CrossRef]

- Dowell P, Otto TC, Adi S, Lane MD. Convergence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and Foxo1 signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(46):45485-45491. [CrossRef]

- Karpen SJ. Nuclear receptor regulation of hepatic function. J Hepatol. 2002;36(6):832-850.

- Nakamura K, Moore R, Negishi M, Sueyoshi T. Nuclear pregnane X receptor cross-talk with FoxA2 to mediate drug-induced regulation of lipid metabolism in fasting mouse liver. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9768-9776. [CrossRef]

- Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science. 2001;294(5548):1866-1870. [CrossRef]

- Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335-376. [CrossRef]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. [CrossRef]

- Doyle S, Vaidya S, O'Connell R, et al. IRF3 mediates a TLR3/TLR4-specific antiviral gene program. Immunity. 2002;17(3):251-263. [CrossRef]

- Fan W, Morinaga H, Kim JJ, et al. FoxO1 regulates Tlr4 inflammatory pathway signaling in macrophages. EMBO J. 2010;29(24):4223-4236. [CrossRef]

- Das S, et al. Dysregulation of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in transforming growth factor-β1-induced gene expression in mesangial cells and diabetic kidney. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(34):12695-12707.

- Raghavan PR. Metadichol induced expression of toll receptor family members in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Med Res Arch. 2024;12(8).

- Loizou L, Andersen KG, Betz AG. Foxp3 interacts with c-Rel to mediate NF-kappaB repression. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18670. [CrossRef]

- Fan W, Imamura T, Sonoda N, et al. FOXO1 transrepresses peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transactivation, coordinating an insulin-induced feed-forward response in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(18):12188-12197. [CrossRef]

- Raghunath A, Sundarraj K, Nagarajan R, et al. Antioxidant response elements: discovery, classes, regulation and potential applications. Redox Biol. 2018;17:297-314. [CrossRef]

- Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Suuronen T, et al. SIRT1 longevity factor suppresses NF-κB- driven immune responses: regulation of aging via NF-κB acetylation? Bioessays. 2008;30(10):939-942. [CrossRef]

- Tanno M, Sakamoto J, Miura T, et al. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6823-6832. [CrossRef]

- Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403(6771):795-800. [CrossRef]

- Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303(5666):2011-2015. [CrossRef]

- Sandri M, Lin J, Handschin C, et al. SIRT1 protein, by blocking the activities of transcription factors FoxO1 and FoxO3, inhibits muscle atrophy and promotes muscle growth. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(42):30515-30526. [CrossRef]

- Fulco M, Cen Y, Zhao P, et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev Cell. 2008;14(5):661-673. [CrossRef]

- Beronja S, Janki P, Heller E, et al. SIRT1 mediates FOXA2 breakdown by deacetylation in a nutrient-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98438. [CrossRef]

- van Loosdregt J, Vercoulen Y, Guichelaar T, et al. Regulation of Treg functionality by acetylation-mediated Foxp3 protein stabilization. Blood. 2010;115(5):965-974. [CrossRef]

- Chang HC, Guarente L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25(3):138-145. [CrossRef]

- Kwon HS, Lim HW, Wu J, et al. Three novel acetylation sites in the Foxp3 transcription factor regulate the suppressive activity of regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(6):2712-2721. [CrossRef]

- Sweet DR, Fan L, Hsieh PN, Jain MK. Krüppel-Like Factors in Vascular Inflammation: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:6. [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb AM, Yang VW. Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4): What we currently know. Gene. 2017;611:27-37. [CrossRef]

- Ohkura N, Hamaguchi M, Morishita H, et al. T-cell receptor stimulation-induced epigenetic changes and Foxp3 expression are independent and complementary events required for Treg cell development. Immunity. 2012;37(5):785-799. [CrossRef]

- Lee HY, Youn SW, Kim JY, et al. FOXO1 impairs whereas statin protects endothelial function in diabetes through reciprocal regulation of Krüppel-like factor 2. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;97(1):143-152. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(3):164-179. [CrossRef]

- Xiong X, Tao R, DePinho RA, Dong XC. Temporal coordination of hepatic gluconeogenesis by FOXO1 and KLF15. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;381(1-2):213-220. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Zhang J, Pope CF, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus resulting from impaired beta- cell compensation in the setting of chronic inflammation in mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53(9):2024- 2032. [CrossRef]

- Cantó C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20(2):98-105. [CrossRef]

- Kondratov RV, Kondratova AA, Gorbacheva VY, Vykhovanets OV, Antoch MP. Early aging and age-related pathologies in mice deficient in BMAL1, the core component of the circadian clock. Genes Dev. 2006;20(14):1868-1873. [CrossRef]

- Bass J, Takahashi JS. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science. 2010;330(6009):1349-1354. [CrossRef]

- Koike N, Yoo SH, Huang HC, et al. Transcriptional architecture and chromatin landscape of the core circadian clock in mammals. Science. 2012;338(6105):349-354. [CrossRef]

- Xiong X, Tao R, DePinho RA, Dong XC. The autophagy-related gene 14 (Atg14) is regulated by forkhead box O transcription factors and circadian rhythms and plays a critical role in hepatic autophagy and lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(46):39107-39114. [CrossRef]

- Lamia KA, Storch KF, Weitz CJ. Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(39):15172-15177. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Fang B, Emmett MJ, et al. Discrete functions of nuclear receptor Rev-erbα couple metabolism to the clock. Science. 2015;348(6242):1488-1492. [CrossRef]

- Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Buhr ED, et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466(7306):627-631. [CrossRef]

- Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, et al. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331(6022):1315-1319. [CrossRef]

- Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling aging. Nature. 1997;390(6655):45-51. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by the anti-aging hormone klotho. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):38029-38034. [CrossRef]

- Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309(5742):1829-1833. [CrossRef]

- Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(10):6120-6123. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan PR. Metadichol-induced expression of sirtuins 1-7 in somatic and cancer cells. Med Res Arch. 2024;12(6). [CrossRef]

- Mencke R, Rijkse E, Ozyilmaz A, et al. Klotho: a potential therapeutic target in aging and neurodegeneration beyond chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17(1):sfad276. [CrossRef]

- Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444(7120):770-774. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science. 2007;317(5839):803-806. [CrossRef]

- Bian A, Neyra JA, Zhan M, Hu MC. Klotho, stem cells, and aging. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1233-1243. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Quan JI, Kinghorn KJ, Bjedov I. Genetics and pharmacology of longevity: the road to therapeutics for healthy aging. Adv Genet. 2015;90:1-101. [CrossRef]

- McCabe MJ, Maier AB, Voight BF, et al. Thyroid transcription factor FOXE1 interacts with ETS factor ELK1 to coregulate TERT. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(12):e1006543. [CrossRef]

- McCabe MJ, Maier AB, Voight BF, et al. Thyroid transcription factor FOXE1 interacts with ETS factor ELK1 to coregulate TERT. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(11):859-872. [CrossRef]

- Jin J, Wang G, Zhang Y, et al. The ETS inhibitor YK-4-279 suppresses thyroid cancer progression by targeting ETS/FOXE1-mediated TERT activation. Front Oncol. 2021;11:649323. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Lee J, Chen Y, et al. Proximal telomeric decompaction due to telomere shortening drives FOXC1-dependent myocardial senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(16):e202345678.

- Martins R, Lithgow GJ, Link W. Long live FOXO: unraveling the role of FOXO proteins in aging and longevity. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;29:206-213. [CrossRef]

- Feng Q, Li X, Sun W, et al. FOXO1-dependent DNA damage repair is regulated by JNK in lung cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2014;44(4):1281-1290. [CrossRef]

- Bellissimo F, Vella V, Nicolosi ML, et al. Regulation of cellular senescence via the FOXO4-p53 axis. Aging Cell. 2024;23(1):e13310. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Gomes AR, Monteiro LJ, et al. Insights into a critical role of the FOXO3a-FOXM1 axis in DNA damage response and genotoxic drug resistance. Front Oncol. 2016;6:127. [CrossRef]

- Oh G, Kim H, Park H, et al. Mst1-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO1 and C/EBP-β stimulates cell protection in the heart. Nat Commun. 2024;15:50393.

- Edalat S, Motamed N, Pournasr B, Baharvand H. Role of FoxO proteins in cellular response to antitumor agents. Oncol Lett. 2019;17(1):1107-1114. [CrossRef]

- Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Jay SM, et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Science. 2013;344(6184):649-654. [CrossRef]

- Katsimpardi L, Litterman NK, Schein PA, et al. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science. 2014;344(6184):630-634. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Sun H, Dan J, et al. GDF11 induces cardiac and skeletal muscle regeneration through Smad2/3-dependent signaling. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Li J, Chen X, et al. GDF11 rejuvenates senescent skeletal muscle via regulation of FOXO3a and autophagy pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(6):630.

- Brun CE, Rudnicki MA. GDF11 and the regulation of muscle regeneration. FEBS J. 2015;282(22):4056-4067. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wei J, Li F, et al. GDF11 treatment improves muscle strength and enhances FOXO signaling in aged mice. Aging Cell. 2017;16(6):1182-1192. [CrossRef]

- Katsimpardi L, Fantin A, de Lagrange P, et al. GDF11 regulates metabolic homeostasis through induction of hepatic FOXA transcriptional programs. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):174-185.

- Egerman MA, Cadena SM, Gilbert JA, et al. GDF11 increases with age and inhibits skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):164-174. [CrossRef]

- Sinha M, Jang YC, Oh J, et al. Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in multiple tissues through FOX network modulation. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):870-878. [CrossRef]

- Nakae J, Kitamura T, Silver DL, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2003;4(1):119-129. [CrossRef]

- Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, et al. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1α interaction. Nature. 2003;423(6939):550-555. [CrossRef]

- Kaestner KH. The FoxA factors in organogenesis and physiology of the liver. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2217-2223.

- Bochkis IM, Schug J, Ye DZ, Kurinna S, Stratton SA, Barton MC, Kaestner KH. Genome-wide responses to FoxA2 reveal its conserved role in regulating liver metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(41):27456-27464. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133(5):775-787. [CrossRef]

- Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531-564. [CrossRef]

- Uda M, Ottolenghi C, Crisponi L, et al. Foxl2 disruption causes mouse ovarian failure by premature follicle depletion. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(6):1486-1499. [CrossRef]

- Boekelheide K, Sigman M, Hall SJ, Hwang K, et al. Nuclear receptors in human disease. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(3):342-430.

- Vaquero A, Scher M, Lee D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Sirtuin regulation of histone methylation and gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(3):138-145. [CrossRef]

- Lamia KA, Sachdeva UM, DiTacchio L, et al. AMPK regulates the circadian clock by cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science. 2009;326(5951):437-440. [CrossRef]

- Martins R, Lithgow GJ, Link W. Long live FOXO: unraveling the role of FOXO proteins in aging and longevity. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;29:206-213. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang W, Li MO. Foxo: in command of T lymphocyte homeostasis and tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(1):26-33. [CrossRef]

- Hsu AL, Murphy CT, Kenyon C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science. 2003;300(5622):1142-1145. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).