Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Setup of the Dynamical System

2. Scalar Dynamical System

3. Multivariate Taylor Expansion of

4. General Form with Coefficients

5. Multivariate Taylor Expansion of

6. General Form with Coefficients

7. General Form with Coefficients

- For each total degree from 0 to 5,

- Iterate , and let ,

- Compute .

8. Step-by-Step Coefficient Calculations for Bifurcation Analysis

8.1. Zeroth Order Term

8.1.1. First-Order Terms

8.1.2. Second-Order Terms

8.2. Third-Order Terms

8.3. Fourth-Order Terms

8.4. Fifth-Order Terms

9. Summary Form for Bifurcation Analysis

10. Generic Conditions for Saddle-Node Bifurcation

11. Taylor Expansion of

11.1. Let:

12. Rescaling

13. Choose Normalising Constants

14. Final Normal Form

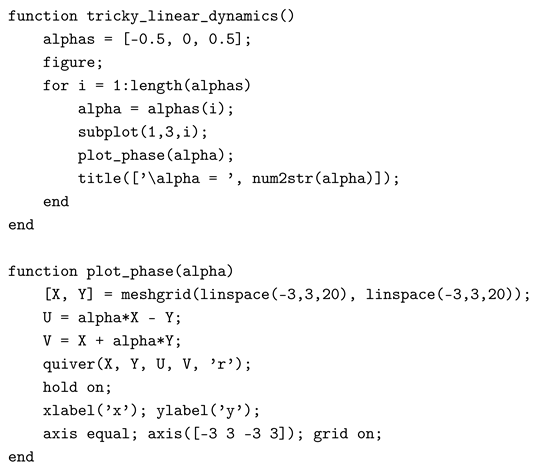

15. Significance of Generic Conditions

- ensures the equilibrium is sensitive to parameter changes.

- ensures the equilibrium bifurcates nonlinearly.

- Absence of these would require higher-order terms for unfolding (codimension ).

16. Derivation of the Normal Form for Transcritical Bifurcation

16.1. Step 1: Taylor Expansion

16.2. Step 2: Rename Coefficients

16.3. Step 3: Rescale Variables

16.4. Step 4: Choose Scaling

16.5. Step 5: Final Form

17. Mathematical Reason for Generic Conditions

- Structural stability: The bifurcation persists under small perturbations.

- Codimension one: Only one parameter is needed to unfold the degeneracy.

- Non-degeneracy: Avoids flat or degenerate dynamics.

17.1. Saddle-node Bifurcation Conditions

17.2. Transcritical Bifurcation Conditions

17.3. Mathematical Foundation

- Singularity theory: Unfoldings of degenerate equilibria.

- Normal form theory: Reduction to simplest system under smooth change of variables.

- Universal unfoldings: E.g., is the universal unfolding of .

18. Example 1: Quadratic System

18.1. Check Generic Conditions

18.2. Equilibria

- If : two real equilibria (saddle-node structure).

- If : one degenerate equilibrium at .

- If : no real equilibria.

18.3. Stability

19. Example 2: Cubic Perturbation System

19.1. Check Conditions at

19.2. Try Another Point

20. Final Remarks

- Verify saddle-node bifurcation criteria.

- Locate bifurcation points.

- Classify stability near bifurcation.

21. Introduction to Hopf Bifurcation

21.1. Generic Conditions for Hopf Bifurcation

- (H1)

- (Equilibrium exists),

- (H2)

- The Jacobian has a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues , with ,

- (H3)

- The real part of the eigenvalues crosses zero with nonzero speed as varies:

22. Example 1: Classical Normal Form

23. System 1: Normal Form of Hopf Bifurcation

23.1. Step 1: Fixed Point

23.2. Step 2: Linearisation

23.3. Step 3: Hopf Conditions

- changes sign at

- Transversality:

23.4. Step 4: Type of Hopf Bifurcation

24. Predator-Prey Type System

25. Predator-Prey with Saturating Functional Response

25.1. Step 1: Fixed Points

25.2. Step 2: Jacobian Matrix

25.3. Step 3: Hopf Conditions

- A pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues appear.

- Trace = 0, Det > 0 at bifurcation.

- Transversality condition holds.

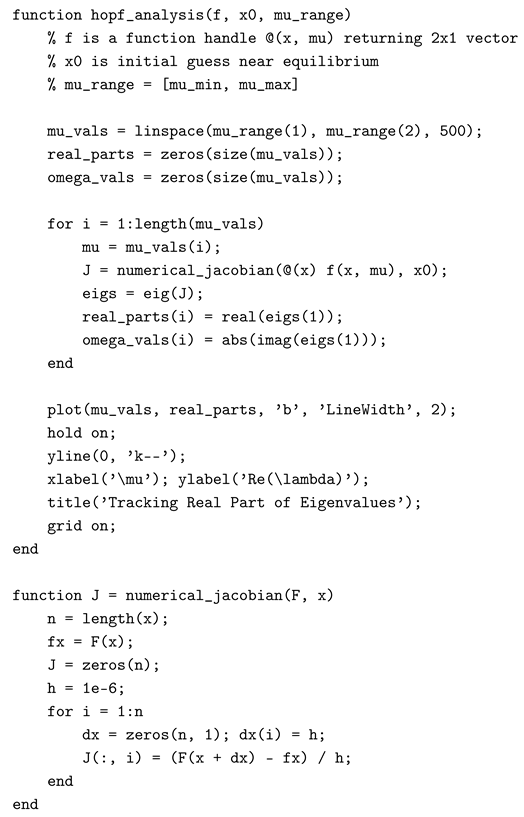

26. MATLAB Code for One-Parameter Hopf Analysis

27. System Description

28. Matrix Form

29. Eigenvalue Calculation

30. Interpretation of Dynamics

- : Spiral source (unstable).

- : Spiral sink (stable).

- : Pure centre (closed orbits).

31. MATLAB Visualisation (R2016 Compatible)

32. Conclusions

References

- Shahrear, P.; Glass, L.; Wilds, R.; Edwards, R. Dynamics in piecewise linear and continuous models of complex switching networks . Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2015, 110, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P Shahrear, L Glass, R Edwards. (2018). Collapsing chaos. Texts in Biomathematics, 35-43.

- Karim, M.D.S.; Shahrear, P.; Rahman, M.D.M.; Ahamad, R. MDS Karim, P Shahrear, MDM Rahman, R Ahamad. Generating formulae for the existing and non-existing numerical integration schemes . Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences 2005, 21, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrear, P.; Faruque, S.B. Shift of the ISCO and gravitomagnetic clock effect due to gravitational spin-orbit coupling . International Journal of Modern Physics D 2007, 16(11), 1863–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, S.B.; Shahrear, P. On the gravitomagnetic clock effect . Fizika B: A Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics 2008, 17(3), 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, F.; Ahamad, R.; Karim, M.S.; Shahrear, P.; Rahman, M.M. Evaluation of Triangular Domain Integrals by use of Gaussian Quadrature for Square Domain Integrals . SUST Studies 2010, 12(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- S H Strogatz. (1994). Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- L Perko. (2001). Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

- Shahrear, P.; Rahman, S.M.S.; Nahid, M.M.H. Prediction and mathematical analysis of the outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19) in Bangladesh . Results in Applied Mathematics 2021, 10, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrear, P.; Habiba, U.; Rezwan, S. The Role of the Poincaré Map is Indicating a New Direction in the Analysis of the Genetic Network . International Review on Modelling and Simulations (I.RE.MO.S.) 2022, 15(5), 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiyaz, C.A.; Shahrear, P.; Shamim, R.A.; Strauss, T.; Khan, T. Comparison of different radial basis function networks for the electrical impedance tomography (EIT) inverse problem . Algorithms 2023, 16(10), 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Srinivas, M.N.; Shahrear, P.; Rahman, S.M.S.; Nahid, M.M.H.; Murthy, B.S.N. Transmission dynamics and control of COVID-19: A mathematical modelling study . Journal of Applied Nonlinear Dynamics 2023, 12(2), 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Shahrear, P.; Saha, G.; Ataullah, M.; Shahidur, M.R. Mathematical Analysis and Prediction of Future Outbreak of Dengue on Time-varying Contact Rate using Machine Learning Approach . Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 178, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Saha, G.; Shahrear, P.; Saha, S.C. Phase change material performance in chamfered dual enclosures: Exploring the roles of geometry, inclination angles and heat flux . International Journal of Thermofluids 2024, 24, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrear, P.; Islam, M.S.; Bakkar, M.A.; Bushra, A.; Hossain, I. Navigating Epidemic Mathematics: Exploring Tools for Mathematical Modelling in Biology . arXiv 2024, arXiv:2501.00035. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrear, P.; Singha, S.; Tareq, B.; Sharma, Z.; Tanmi, Tasnim. Analysis of the Covid-19 Mathematical Model Based on Vaccine Data: A Descriptive Approach to Eradicate the Outbreak . Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AK Saha, G Saha, P Shahrear. (2024). Dynamics of SEPAIVRD model for COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Preprints.

- Junaid, M.; Saha, G.; Shahrear, P.; Saha, S.C. Numerical Evaluation of a Dual Phase Change Material-Integrated Cap for Prolonged Thermal Protection in Extreme Heat . Results in Engineering 2025, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Shahrear, P.; Habiba, U. Impact of bifurcation angle on hemodynamics and oxygen delivery in stenosed arterial junctions . Physics of Fluids 2025, 37(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G Saha, P Shahrear, A Faiyaz, AK Saha. (2025). Mathematical Modeling of Lumpy Skin Disease: New Perspectives and Insights. Partial Differential Equations in Applied Mathematics, 101218.

- Saha, G.; Shahrear, P.; Rahman, S.; Nazi, R.; Srinivas, M.N.; Das, K. Climate change potential impacts on mosquito-borne diseases: a mathematical modelling analysis . Tamkang Journal of Mathematics 2025, 56(3), 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. M. S..; Samanta, F..; Shahrear, P.. Analysis of COVID-19 Disease Transmission: A Blended Appraisal of Quarantine and Vaccination Effects in Bangladesh . GORTERIA 2025, 65(7), 32–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, J..; Shahrear, P..; Chowdhury Ruhel, F.. Analysis of COVID-19 Disease Transmission: A Blended Appraisal of Quarantine and Vaccination Effects in Bangladesh . Journal of Advanced Research in Numerical Heat Transfer 2025, 31(1), 126–150. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrear, P. and Habiba, U. and Islam, M. D. S. and Hussain, F. and Saha, G. (2025). Tracking the Rhythm of Heat: Seasonal SEIR Modelling and Machine Learning for Heat Wave Forecastingh. Preprint.

- Shahrear, P. and Saiki, M. F. H. and Nabi Tareq, M. T. (2024). Analysis of COVID-19 Data Based on Modelling and Descriptive Statistical Approach. Preprint Manuscript.

- H Kielhöfer. (2012). Bifurcation Theory: An Introduction with Applications to Partial Differential Equations. New York, NY: Springer. :contentReference[oaicite:0]index=0.

- S-N Chow, J K Hale. (1982). Methods of Bifurcation Theory. New York, NY: Springer. :contentReference[oaicite:1]index=1.

- Y A Kuznetsov. (2023). Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. :contentReference[oaicite:2]index=2.

- I G Vardoulakis, J Sulem. (1995). Bifurcation Analysis in Geomechanics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. :contentReference[oaicite:3]index=3.

- H A Dijkstra, F W Wubs. (2023). Bifurcation Analysis of Fluid Flows. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. :contentReference[oaicite:4]index=4.

- J-Q Sun, A C J Luo (Eds.). (2006). Bifurcation and Chaos in Complex Systems, Volume 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier. :contentReference[oaicite:5]index=5.

- F Seydel, F W Schneider, T Küpper, H Troger (Eds.). (1991). Bifurcation and Chaos: Analysis, Algorithms, Applications. Basel: Birkhäuser. :contentReference[oaicite:6]index=6.

- A G Wilson. (1981). Catastrophe Theory and Bifurcation: Applications to Urban and Regional Systems. London: Routledge. :contentReference[oaicite:7]index=7.

- A C J Luo. (2019). Bifurcation and Stability in Nonlinear Dynamical Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. :contentReference[oaicite:8]index=8.

- J C Alexander, J A Yorke. (1978). Global bifurcations of periodic orbits. American Journal of Mathematics, 100(2), 263–292. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. :contentReference[oaicite:0]index=0.

- M J Feigenbaum. (1978). Quantitative universality for a class of nonlinear transformations. Journal of Statistical Physics, 19(1), 25–52. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. :contentReference[oaicite:1]index=1.

- M J Feigenbaum. (1979). The onset spectrum of turbulence. Physics Letters A, 74(6), 375–378. Amsterdam: Elsevier. :contentReference[oaicite:2]index=2.

- M J Feigenbaum. (1980). The transition to aperiodic behavior in turbulent systems. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 77(1), 65–86. Berlin: Springer. :contentReference[oaicite:3]index=3. Berlin.

- S N Chow, J Mallet-Paret. (1977). Integral averaging and Hopf’s bifurcation. Journal of Differential Equations, 26(1), 112–159. New York, NY: Academic Press. :contentReference[oaicite:4]index=4.

- S N Chow, J Mallet-Paret. (1978). The Fuller index and global Hopf bifurcations. Journal of Differential Equations, 29(1), 66–85. New York, NY: Academic Press. :contentReference[oaicite:5]index=5.

- J Mallet-Paret, J A Yorke. (1982). Snakes: oriented families of periodic orbits, their sources, sinks and continuation. Journal of Differential Equations, 43(3), 419–450. New York, NY: Academic Press. :contentReference[oaicite:6]index=6.

- Shahrear, P.; Glass, L.; Edwards, R. Chaotic dynamics and diffusion in a piecewise linear equation . Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2015, 25(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P Shahrear, L Glass, N Del Buono. (2015). Analysis of Piecewise Linear Equations with Bizarre Dynamics. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Mathematics, 135.

- Chakraborty, A.K.; Shahrear, P.; Islam, M.A. Analysis of epidemic model by differential transform method . J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol 2017, 4(2), 6574–6581. [Google Scholar]

- MA Islam, MA Sakib, P Shahrear, SMS Rahman. (2017). The Dynamics of Poverty, Drug Addiction and Snatching In Sylhet, Bangladesh.

- Sakib, M.; Islam, M.; Shahrear, P.; Habiba, U. Dynamics of poverty and drug addiction in Sylhet, Bangladesh . Dynamics 2017, 4(2). [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.M.S.; Islam, M.A.; Shahrear, P.; Islam, M.S. Mathematical Model on Branch Canker Disease in Sylhet, Bangladesh . Journal of Mathematics 2017, 13(1 Ver. IV), 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrear, P.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Islam, M.A.; Habiba, U. Analysis of computer virus propagation based on compartmental model . Applied and Computational Mathematics 2018, 7(1-2), 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ahamad, R.; Karim, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Shahrear, P. Finite element formulation employing higher order elements and software for one dimensional engineering problems . SUST Journal of Science and Technology 2019, 29(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).