Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Instruments

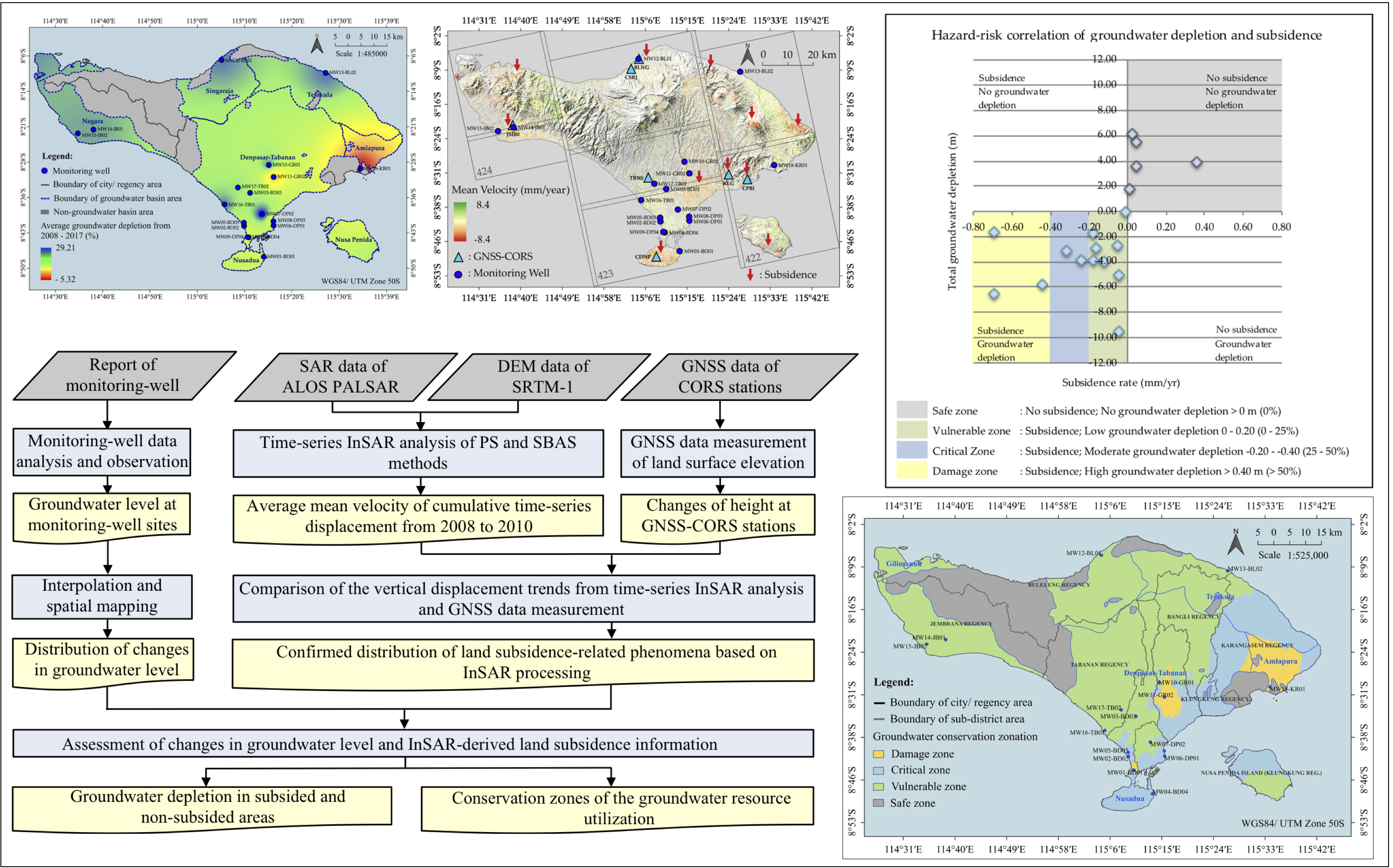

2.3. Research Scheme

2.4. Groundwater Depletion Monitoring

2.5. Land Displacement Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Information of Groundwater Depletion

3.2. Distribution of Land Subsidence

3.3. Hazard Risk Geospatial-Based Assessment of Groundwater Depletion and Land Subsidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, G.; Chen, H.; Chen, D.; Yan, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhou, R. Real-Time Management of Groundwater Resources Based on Wireless Sensors Networks. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2018, 7, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, United Nation Population Database (June 21, 2017) by United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Olli, V. Megacities, Development and Water. Int. J. Water Resour. D 2006, 22, 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Nicholls, R.; Woodroffe, C.; Hanson, S.; Hinkel, J.; Kebede, A.S.; Neumann, B.; Vafeidis, A.T. Sea-Level Rise Impacts and Responses: A Global Perspective; Springer: The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- Amarnath, G.; Ameer, M.; Aggarwal, P.; Smakhtin, V. Detecting Spatio-Temporal Changes in the Extent of Seasonal and Annual Flooding in South Asia Using Multi-resolution Satellite Data. In Earth Resources and Environmental Remote Sensing/GIS Applications III: Proceedings of the International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE), 1–6 July 2012; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Civco, D.L., Ehlers, M., Habib, S., Maltese, A., Messinger, D., Michel, U., Nikolakopoulos, K.G., Schulz, K., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE): Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; pp. 853818-1–853818-11. [Google Scholar]

- ADPC. Assessing the Risk. In Disaster Risk Management in Asia; Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC): Bangkok, Thailand, 2013; Ch. 3; pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. The Nature of Hazards. In Environmental Hazards: Assessing Risk and Reducing Disaster, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; Ch. 1, Sec. 3; pp. 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Trends from the Cases. In From a Reactive to Proactive then People Centered Approach to DDR: Taking Inspiration from the Hyogo Framework for Action to Implement the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 4–7. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/49574_hfacelebrationreport7082015verdana.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Chen, B.B.; Gong, H.L.; Li, X.J.; Lei, K.C.; Ke, Y.H.; Duan, G.Y.; Zhou, C.F. Spatial Correlation Between Land Subsidence and Urbanization in Beijing, China. Nat. Hazards 2014, 75, 2637–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corapcioglu, M.Y.; Bear, J.A. Mathematical Model for Regional Land Subsidence Due to Pumping: 3. Integrated Equations for a Phreatic Aquifer. Water Resour. Res. 1983, 19, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozzi, T.; Wegmiiller, U.; Tosl, L.; Bitelli, G.; Spreckels, V. Land Subsidence Monitoring with Differential SAR Interferometry. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2001, 67, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, T.L.; Galloway, D.L. Impacts of Land Subsidence Caused by Withdrawal of Underground Fluids in the United States. In Humans as Geologic Agents; Ehlen, J., Haneberg, W.C., Larson, R.A., Eds.; Geological Survey of America Reviews in Engineering Geology: Boulder, CO, USA, 2005; Volume XVI, pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, P.A.; Hensley, S.; Joughin, I.R.; Li, F.K.; Madsen, S.N.; Rodríguez, E.; Goldstein, R.M. Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE, New York, NY, USA, 28 March 2000; pp. 333–382. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen, R.F. Radar System Theory and Interferometric Processing. In Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis, Remote Sensing Digital Image Process, 1st ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2001; pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, D.; Hoffmann, J. The Application of Satellite Differential SAR Interferometry-Derived Ground Displacements in Hydrogeology. Hydrogeol. J. 2006, 15, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, D.L.; Burbey, T.J. Review: Regional Land Subsidence Accompanying Groundwater Extraction. Hydrogeol. J. 2011, 19, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungdahl, J. Analysis of Groundwater Level Changes and Land Subsidence in Gothenburg, SW Sweden. Master’s Thesis, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Knight, R.; Zebker, H.A.; Schreuder, W.A. Confined Aquifer Head Measurements and Storage Properties in the San Luis Valley, Colorado, From Spaceborne InSAR Observations. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 3623–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelung, F.; Galloway, D.L.; Bell, J.W.; Zebker, H.A.; Laczniak, R.J. Sensing the Ups and Downs of Las Vegas: InSAR Reveals Structural Control of Land Subsidence and Aquifer-System Deformation. Geology 1999, 27, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Zebker, H.A.; Galloway, D.L.; Amelung, F. Seasonal Subsidence and Rebound in Las Vegas Valley, Nevada, Observed by Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry. Water Resour. Res. 2001, 37, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.W.; Amelung, F.; Ferretti, A.; Bianchi, M.; Novali, F. Permanent Scatterer InSAR Reveals Seasonal and Long-Term Aquifer-System Response to Groundwater Pumping and Artificial Recharge. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.A.; Bürgmann, R. Time-Dependent Land Uplift and Subsidence in the Santa Clara Valley, California, From a Large Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Data Set. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 2416–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussard, E.; Bürgmann, R.; Shirzaei, M.; Fielding, E.J.; Baker, B. Predictability of Hydraulic Head Changes and Characterization of Aquifer-System and Fault Properties from InSAR-Derived Ground Deformation. J. Geophys. Res. 2014, 119, 6572–6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.A.; Knight, R.; Zebker, H.A.; Schreüder, W.A.; Agram, P.S.; Lauknes, T.R. High quality InSAR Data Linked to Seasonal Change in Hydraulic Head for an Agricultural Area in the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.A.; Knight, R.; Zebker, H.A.; Kitanidis, P.K.; Schreüder, W.A. Estimating Temporal Changes in Hydraulic Head Using InSAR Data in the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 4459–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizil, U.; Tisor, L.J. Evaluation of RTK-GPS and Total Station for Application in Land Surveying. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 120, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickle, J.V. GPS for Land Surveyors, 4th ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Northwest Florida, FL, USA, 2015; Ch. 1; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Saghravani, S.R.; Mustapha, S.; Saghravani, S.F. Accuracy comparison of RTK-GPS and automatic level for height determination in land surveying. MASAUM J. Rev. Surv. 2009, 1, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bouraoui, S. Time Series Analysis of SAR Images Using Persistent Scatterer (PS), Small Baseline (SB) and Merged Approaches in Regions with Small Surface Deformation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Earth Sciences, Université de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O.; Cuevas-González, M.; Devanthéry, N.; Crippa, B. Persistent Scatterer Interferometry: A Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampes, B.M. Displacement Parameter Estimation Using Permanent Scatterer Interferometry. Ph.D. Dissertation, Faculty Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, A.; Zebker, H.; Segall, P.; Kampes, B. A New Method for Measuring Deformation on Volcanoes and Other Natural Terrains Using InSAR Persistent Scatterers. Geophy. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Kooij, M.; Hughes, W.; Sato, S.; Poncos, V. Coherent Target Monitoring at High Spatial Density: Examples of Validation Results. In Proceedings of Fringe 2005 Workshop. Frascati, Italy, 28 November–2 December 2005; Available online: http://earth.esa.int/fringe2005/proceedings (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Berardino, P.; Fornaro, G.; Lanari, R.; Sansosti, E. A New Algorithm for Surface Deformation Monitoring Based on Small Baseline Differential SAR Interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali is Sinking Faster, Sea Water Intrusion Has Reached Sanglah Region (13 January 2013) by Bali Post. Available online: http://www.balipost.com/bali (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Bali is Predicted Encountering Severe Water Crisis; Sea Water Intrusion is Getting Worse (15 January 2013) by Bali Post. Available online: http://www.balipost.com/bali (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Sukearsana, I.M.; Dharma, I.G.B.S.; Nuarsa, I.W. Regional Study on Sea Water Intrusion in the Coastal Area in North Kuta District of Badung Regency. ECOTROPHIC J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayantari, I.A.M. Study on Sea Water Intrusion in Candidasa Region of Karangasem (11 January 2017) by Faculty of Engineering, Udayana University, Bali, Indonesia. Available online: https://www.unud.ac.id/en/ (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- BWSBP. Planning of the Improvement and Rehabilitation of Freshwater and Groundwater Supply Networks in Bali Province; River Basin Agency (BWS) of Bali-Penida: Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia, 2017; pp. 2–37. [Google Scholar]

- BPS. Bali Province in Figures; Statistics Agency (BPS) of Bali Province: Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia, 2017; pp. 12–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zebker, H.A.; Hensley, S.; Shanker, P.; Wortham, C. Geodetically Accurate InSAR Data Processor. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 48, 4309–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenqvist, A.; Shimada, M.; Watanabe, M. ALOS PALSAR: Technical Outline and Mission Concepts. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Retrieval of Bio- and Geophysical Parameters from SAR Data for Land Applications, Innsbruck, Austria, 16–24 November 2004; Available online: https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/kyoto/ref (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Sandwell, D.T.; Myer, D.; Mellors, R.; Shimada, M.; Brooks, B.; Foster, J. Accuracy and Resolution of ALOS Interferometry: Vector Deformation Maps of the Father’s Day Intrusion at Kilauea. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 3524–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geodetic Methods—Lab 3: Pseudorange Position Estimation (8 September 2015) by UNAVCO. Available online: http://www.grapenthin.org/teaching/geop572_2015/LAB03_position_estimation.html (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- United States Geological Survey (USGS). USGS EROS Archive—Digital Elevation—Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radar-topography-mission-srtm (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- GMTSAR. Generate DEM Files for Use with GMTSAR. Available online: http://topex.ucsd.edu/gmtsar/demgen (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Adhitya, A.; Effendi, J.; Syafii, A. InaCORS: Infrastructure of GNSS CORS in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the FIG Congress 2014, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 16–21 June 2014; pp. 6853-1–6853-13. [Google Scholar]

- Maciuk, K.; Szombara, S. Annual Crustal Deformation Based on GNSS Observations Between 1996 and 2016. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiglia, D.C.; Pritt, M.D. Two-Dimensional Phase Unwrapping: Theory, Algorithms, and Software; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Ch. 3; pp. 206–298. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, S.; Talbot, N.; Kirk, G. A New System for RTK Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Position Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–23 April 2000; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent Scatterers in SAR Interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykut, N.O.; Gülal, E.; Akpinar, B. Performance of Single Base RTK GNSS Method versus Network RTK. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2015, 19, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS. A Gentle Introduction to GIS. Available online: https://docs.qgis.org/testing/en/docs/gentle_gis_introduction/ (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Mitas, L.; Mitasova, H. Spatial Interpolation. In Geographical Information Systems: Principles, Techniques, Management and Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Ch. 34; pp. 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, A.A.G.P.; Handayani, C.I.M.; Mustafa, F.; Jasmini, M.; Rahmaeni, N.K.D.; Sukarji, M.A.; Amer, L. Status of Ecoregion Environment (SLHE) in Bali and Nusa Tenggara; Center for Ecoregion Management in Bali and Nusa Tenggara: Bali, Indonesia, 2014; pp. 40–68. [Google Scholar]

- DPU. Zonation Map of Groundwater Usage in Bali Province, 2014 Fiscal Year; Public Work Agency (DPU) of Bali Province: Bali, Indonesia, 2014; pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- ESDM. Recapitulation of Groundwater Level at Monitoring Wells, Electrical Conductivity, Total Dissolved Solid, and Salinity Level in 2008–2012; Ministry of Mining and Mineral Resource (ESDM) of Bali Province: Bali, Indonesia, 2013; pp. 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lång, L.; Ojala, L.; Åsman, M. Groundwater Resources in Sweden; Geological Survey of Sweden (SGU): Uppsala, Sweden, 2005. Available online: https://www.bgr.bund.de/EN/ (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Pratt, W.E.; Johnson, D.W. Local Subsidence of the Goose Creek Oil Field. J. Geol. 1926, 34, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleologos, K.; Mertikas, S.P. Evidence and Implications of Extensive Groundwater Overdraft-Induced Land Subsidence in Greece. Eur. Water 2013, 43, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Land Subsidence; United States Geological Survey (USGS): Reston, VA, USA, 2017. Available online: http://water.usgs.gov/edu/earthgwlandsubside.html (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Engdahl, M.; Cecilia, J. Geohazard Description for Göteborg; Version 1; European Geological Data Infrastructure (EDGI): 2013. Available online: http://www.pangeoproject.eu (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Deo, R.; Rossi, C.; Eineder, M. Framework for Fusion of Ascending and Descending Pass Tandem-X Raw DEMs. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 2247–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, A.; Calò, F. A Review of Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) Multi-Track Approaches for the Retrieval of Earth’s Surface Displacements. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1264–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro, P.; Guardiola-Albert, C.; Herrera, G.; Fernández-Merodo, J.A.; Béjar-Pizarro, M.; Bonì, R. Groundwater and Subsidence Modeling Combining Geological and Multi-Satellite SAR Data over the Alto Guadalentín Aquifer (SE Spain). Geofluids 2017, 2017, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsito, D.A.; Susilo; Andreas, H.; Pradipta, D.; Gumilar, I. Regional Phenomena of Vertical Deformation in Southern Part of Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 2nd Geoplanning-International Conference on Geomatics and Planning, Surakarta, Indonesia, 9–10 August 2017; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mahendra, R.S.; Mohanty, P.C.; Bisoyi, H.; Kumar, T.S.; Nayak, S. Assessment and Management of Coastal Multi-Hazard Vulnerability Along the Cuddalore Villupuram, East Coast of India Using Geospatial Techniques. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, M.; Alessandro, P.; Francesca, R.C.; Stefania, A.; Rosa, N.; Paolo, M.D.M. The 2011 Tohoku (Japan) Tsunami Inundation and Liquefaction Investigated Through Optical, Thermal, and SAR Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013, 10, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, K.E.; Belliss, S.E.; Samsonov, S.V.; McNeill, S.J.; Glassey, P.J. A Review of the Status of Satellite Remote Sensing and Image Processing Techniques for Mapping Natural Hazards and Disasters. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2009, 33, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well Number | Monitoring Well ID | Construction Year | Depth (m) | Groundwater Level (m Below Ground Surface) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 1 | 2009 1 | 2010 1 | 2011 1 | 2012 1 | 2013 1 | 2017 2 | ||||

| 1 | MW01-BD01 | 1996 | 50 | 6.25 | 6.40 | 6.00 | 6.35 | 6.50 | 6.00 | 6.10 |

| 2 | MW02-BD02 | 1997 | 50 | 6.30 | 6.86 | 6.70 | 6.80 | 7.82 | 6.35 | 7.74 |

| 3 | MW03-BD03 | 2002 | 40 | 2.15 | 2.20 | 1.75 | 1.84 | 3.01 | 3.50 | 3.20 |

| 4 | MW04-BD04 | 2003 | 40 | 3.60 | 3.80 | 4.05 | 4.38 | 3.78 | 3.70 | 4.58 |

| 5 | MW05-BD05 | 2004 | 65 | 15.75 | 16.57 | 16.20 | 16.75 | 15.05 | 18.20 | 17.66 |

| 6 | MW06-DP01 | 1997 | 50 | 2.85 | 2.67 | 3.25 | 3.37 | 3.87 | 3.20 | 3.18 |

| 7 | MW07-DP02 | 2001 | 40 | 8.45 | 8.45 | 6.25 | 6.38 | 8.45 | 7.00 | 6.30 |

| 8 | MW08-DP03 | 2004 | 60 | 2.55 | 2.66 | 3.16 | 3.25 | 2.85 | 3.20 | 3.63 |

| 9 | MW09-DP04 | 2008 | 60 | - | 6.25 | 9.01 | 9.21 | 7.69 | 8.70 | 10.39 |

| 10 | MW10-GR01 | 1998 | 90 | 39.15 | 39.40 | 39.15 | 39.40 | 40.08 | 39.30 | 39.20 |

| 11 | MW11-GR02 | 2009 | 6060 | 7- | - | 7.85 | 7.85 | 7.16 | 12.10 | 12.00 |

| 12 | MW12-BL01 | 1998 | 40 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| 13 | MW13-BL02 | 2007 | 60 | 7.35 | 7.10 | 6.75 | 7.00 | 7.66 | 7.12 | 7.08 |

| 14 | MW14-JB01 | 2006 | 60 | 10.35 | 10.27 | 9.82 | 9.95 | 10.74 | 9.50 | 10.61 |

| 15 | MW15-JB02 | 2006 | 60 | 17.26 | 17.50 | 17.20 | 16.00 | 16.83 | 16.00 | 17.53 |

| 16 | MW16-TB01 | 2005 | 60 | 8.47 | 8.55 | 7.85 | 7.90 | 8.26 | 8.00 | 8.20 |

| 17 | MW17-TB02 | 2008 | 65 | - | 7.82 | 8.25 | 8.34 | 7.87 | 8.50 | 8.55 |

| 18 | MW18-KR01 | 2007 | 70 | 4.68 | 6.87 | 4.25 | 7.60 | 4.82 | 7.25 | 7.32 |

| Path | Scene ID | Acquisition Date (yyyy/mm/dd) | Number of Days | Baselines for InSAR Processing with a Super Master | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Baseline (days) | Perpendicular Baseline (m) | ||||||

| Row 7000 | Row 7010 | Row 7020 | |||||

| 422 | 05740 | 2007/02/22 | 417 | (Super Master) | - | 0 | 0 |

| 09766 | 2007/11/25 | 693 | 276 | - | −280 | −262 | |

| 11108 | 2008/02/25 | 785 | 368 | - | −566 | −535 | |

| 11779 | 2008/04/10 | 831 | 414 | - | −579 | −543 | |

| 15134 | 2008/11/27 | 1061 | 644 | - | 623 | 597 | |

| 16476 | 2009/02/27 | 1152 | 735 | - | 121 | 107 | |

| 20502 | 2009/11/30 | 1428 | 1011 | - | 26 | 30 | |

| 21173 | 2010/01/15 | 1474 | 1057 | - | −209 | −199 | |

| 21844 | 2010/03/02 | 1520 | 1103 | - | −247 | −231 | |

| 423 | 09343 | 2007/10/27 | 664 | (Super Master) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10014 | 2007/12/12 | 710 | 46 | −274 | −271 | −269 | |

| 10685 | 2008/01/27 | 756 | 92 | −482 | −472 | −464 | |

| 14711 | 2008/10/29 | 1032 | 368 | 770 | 725 | 681 | |

| 15382 | 2008/12/14 | 1078 | 414 | 732 | 691 | 651 | |

| 16053 | 2009/01/29 | 1123 | 459 | 427 | 393 | 358 | |

| 20079 | 2009/11/01 | 1399 | 735 | 103 | 88 | 72 | |

| 21421 | 2010/02/01 | 1491 | 827 | −62 | −66 | −71 | |

| 26118 | 2010/12/20 | 1813 | 1149 | −962 | −943 | −926 | |

| 424 | 05565 | 2007/02/10 | 405 | (Super Master) | - | 0 | 0 |

| 09591 | 2007/11/13 | 681 | 276 | - | −154 | −134 | |

| 11604 | 2008/03/30 | 819 | 414 | - | −992 | −956 | |

| 14959 | 2008/11/15 | 1049 | 644 | - | 838 | 814 | |

| 15630 | 2008/12/31 | 1095 | 690 | - | 279 | 260 | |

| 16301 | 2009/02/15 | 1140 | 735 | - | 279 | 443 | |

| 20327 | 2009/11/18 | 1416 | 1011 | - | −76 | −71 | |

| 20998 | 2010/01/03 | 1462 | 1057 | - | −181 | −171 | |

| 21669 | 2010/02/18 | 1508 | 1103 | - | −301 | −283 | |

| Station | Station ID | Location | Latitude | Longitude | Height (m) | Data Period | Distance (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base station | CSRJ | Singaraja | −8.1497 | 115.0580 | 60.33 | 2008–2010 | - |

| Rover station | CDNP | Denpasar | −8.8181 | 115.1456 | 234.52 | 2008–2010 | 74.97 |

| Rover station | CPBI | Bukit Tengah | −8.5433 | 115.4708 | 278.75 | 2008–2010 | 63.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).