Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

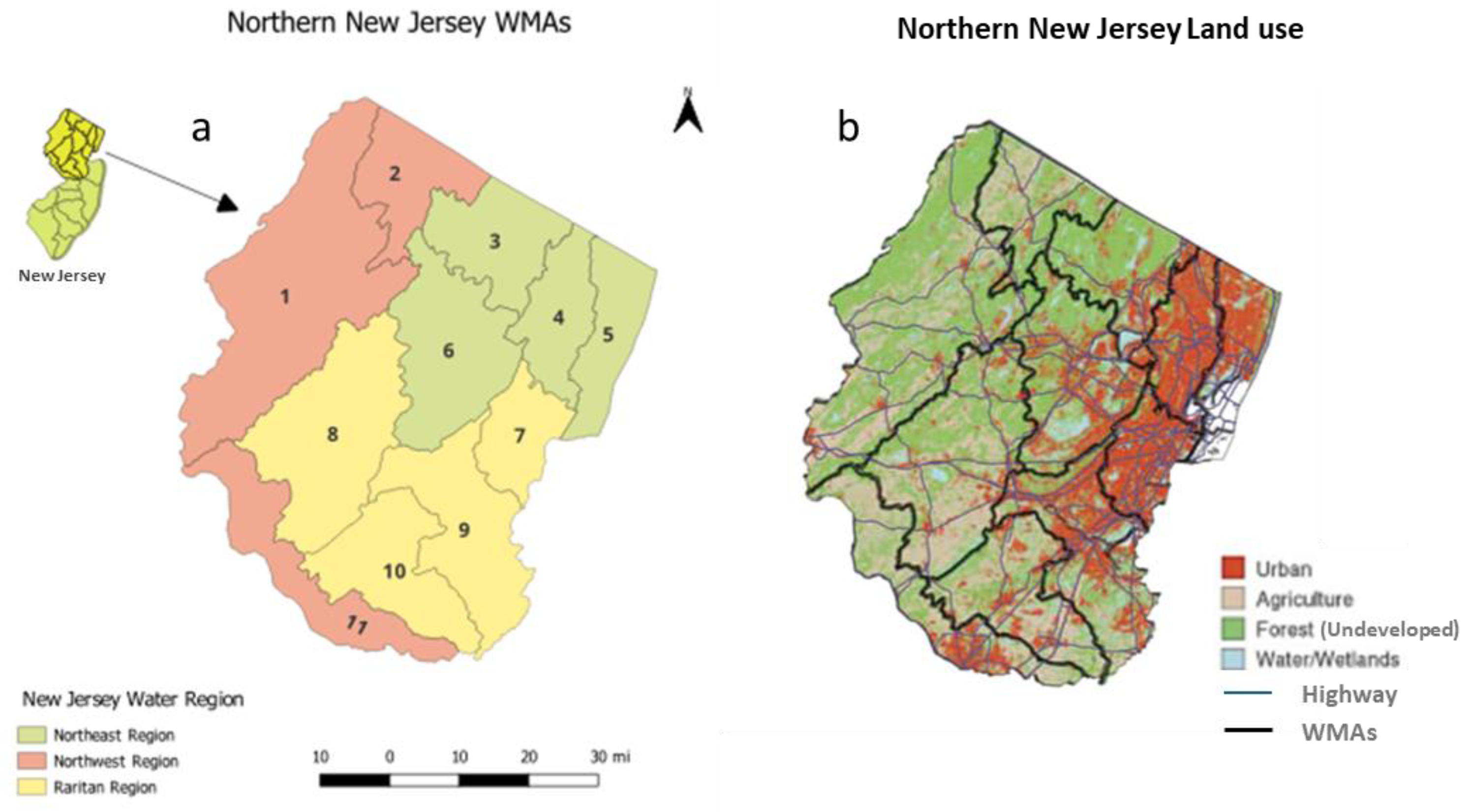

1.1. Study Area

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

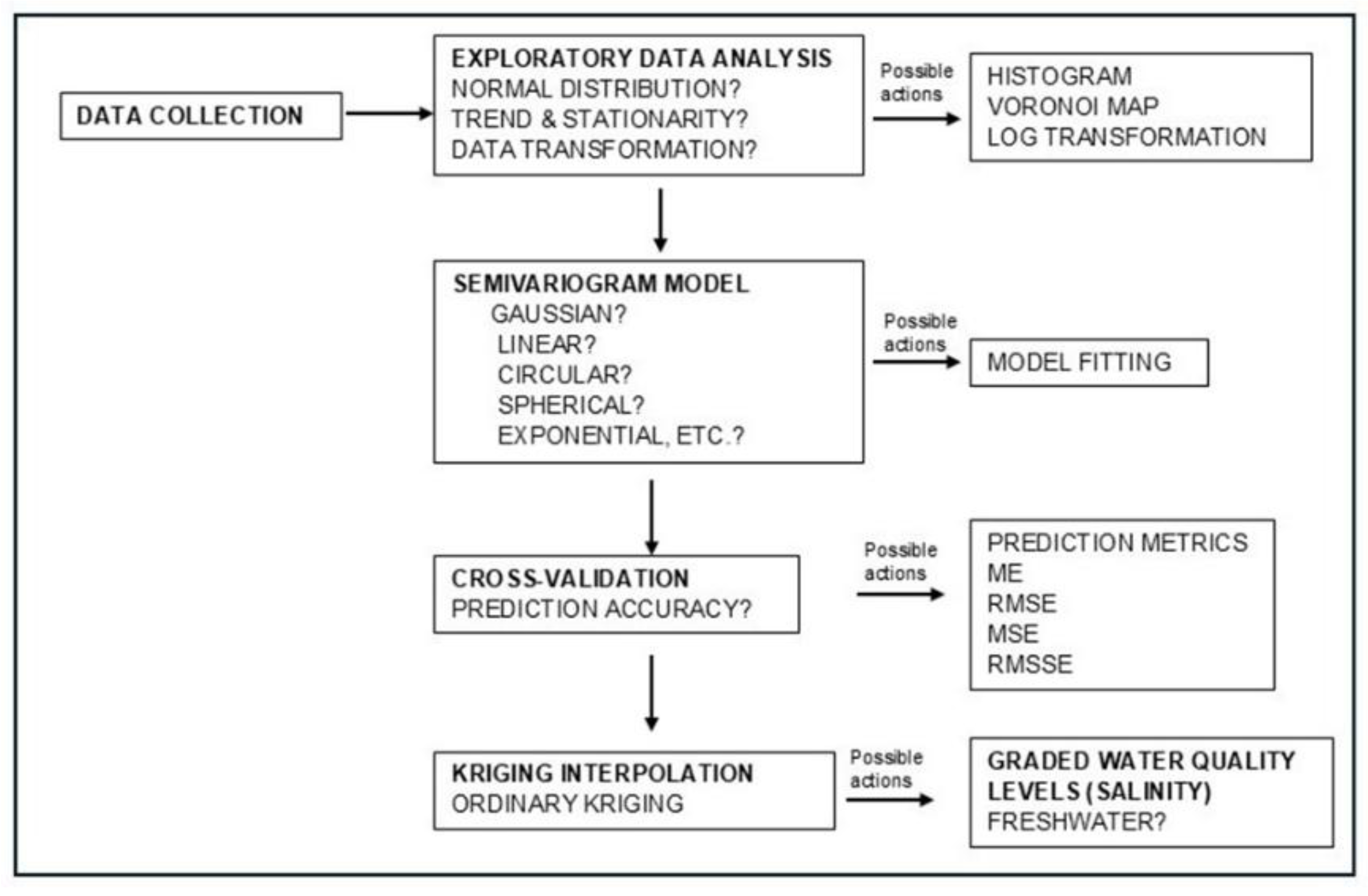

2.2.1. Kriging Interpolation

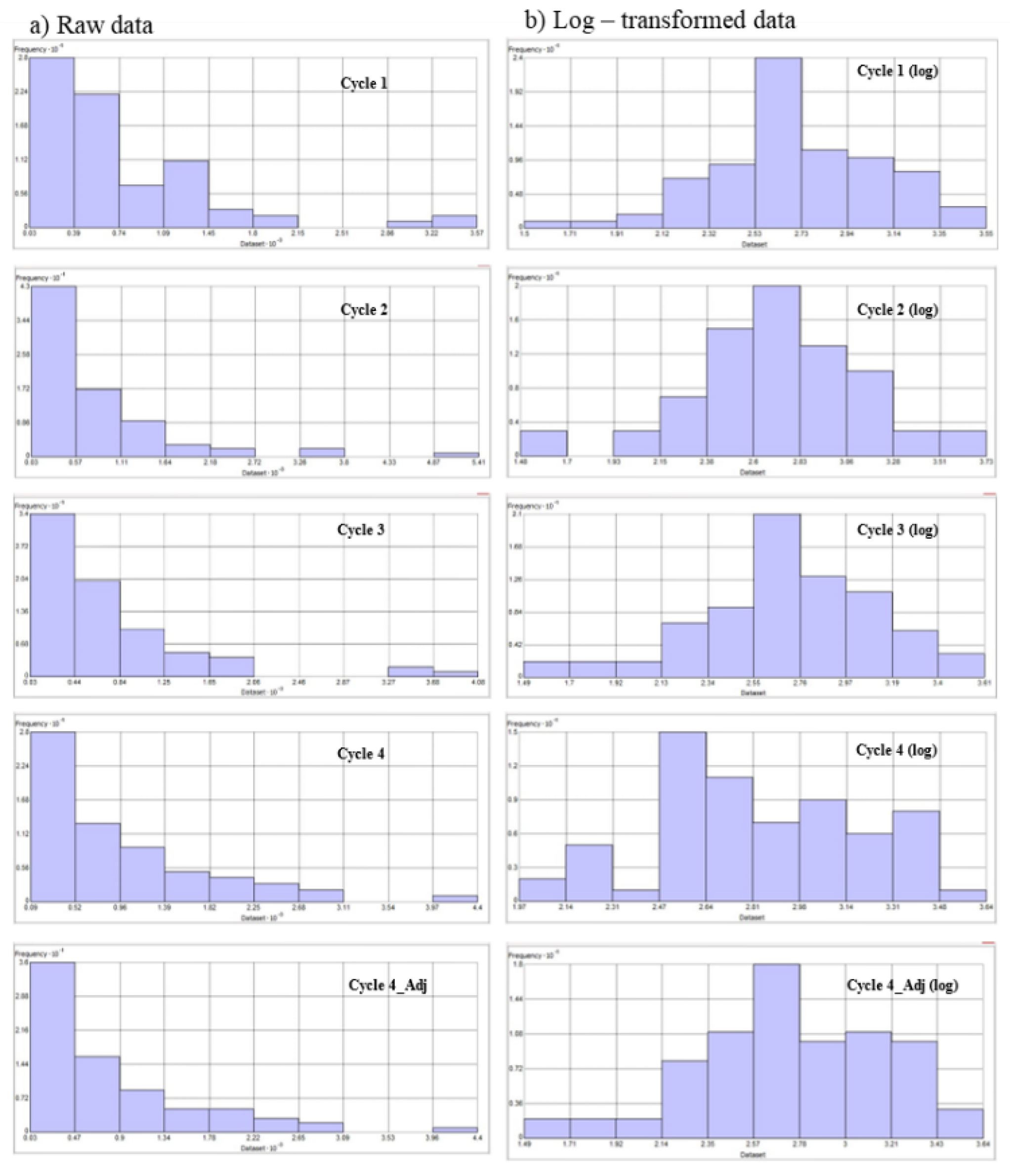

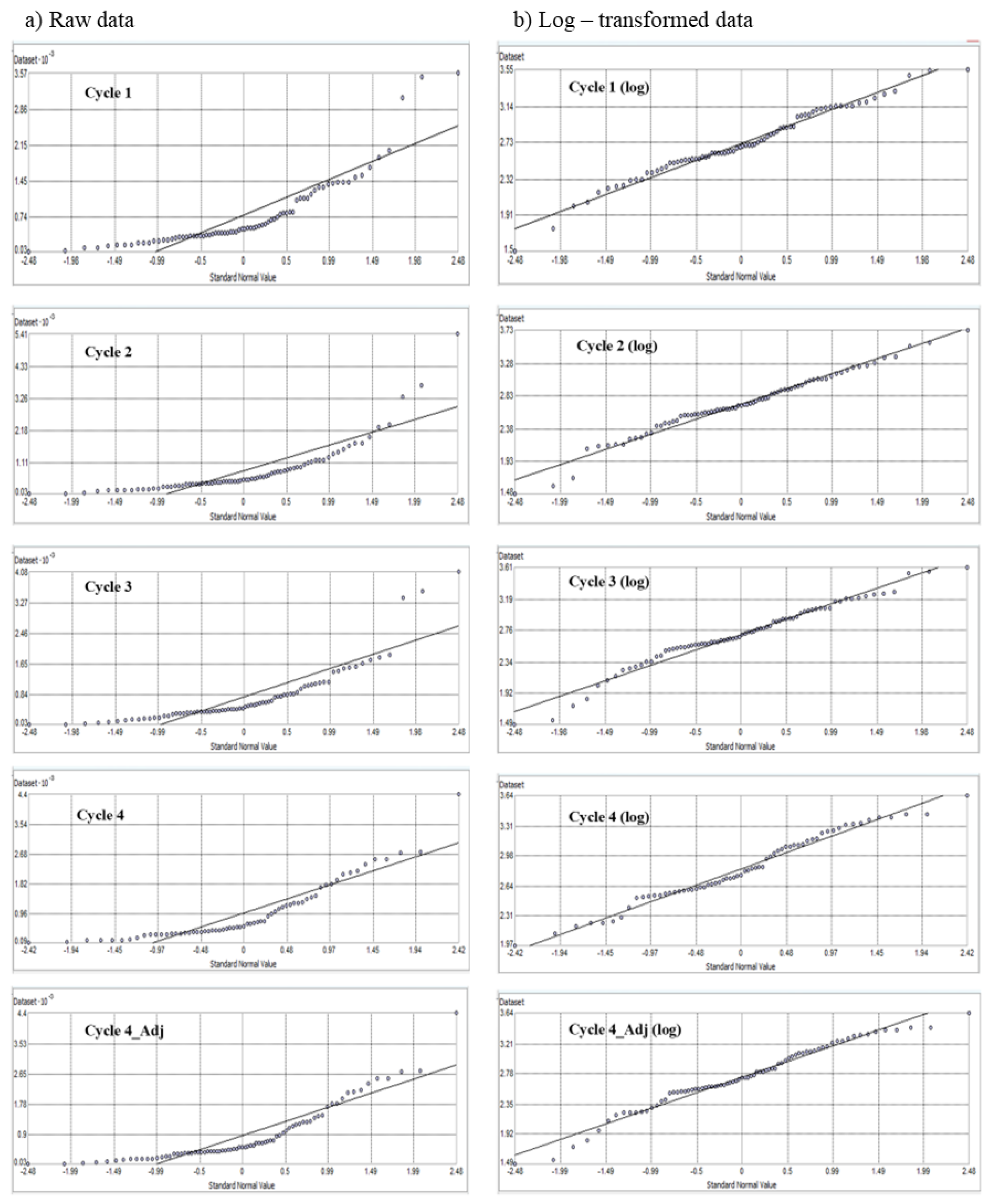

2.2.2. Exploratory Data Analysis

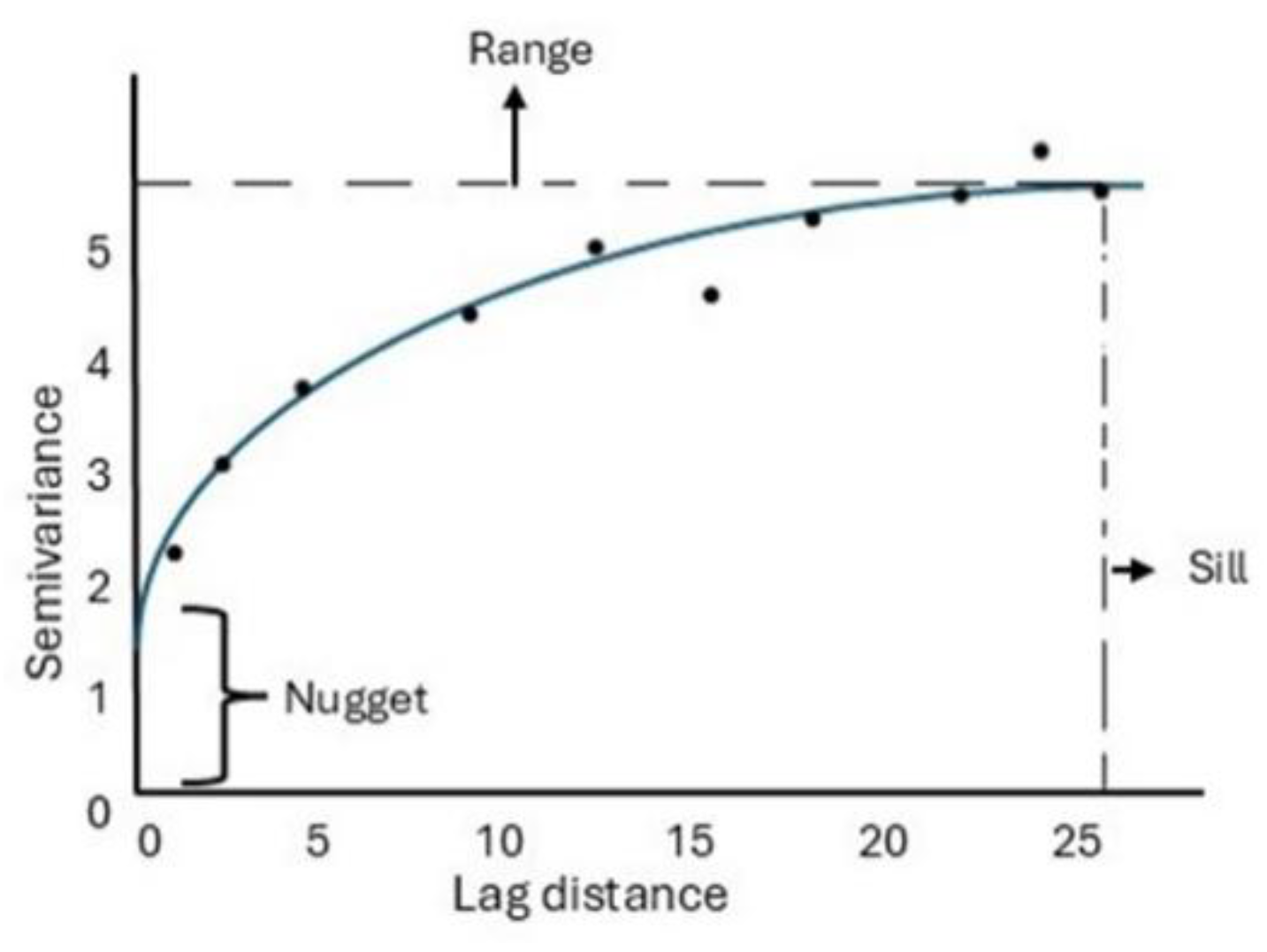

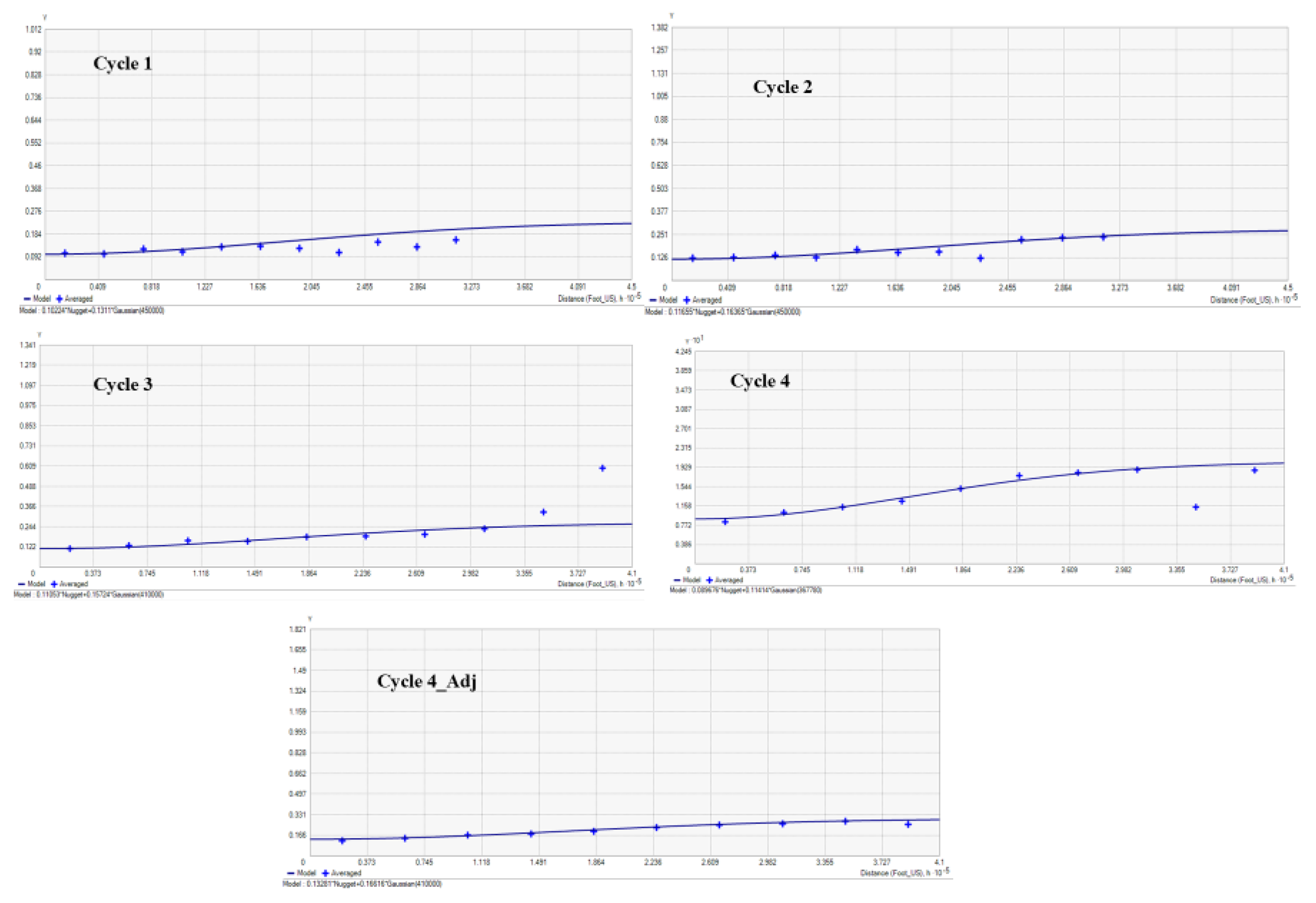

2.2.3. Experimental Semivariogram

2.2.4. Cross-Validation

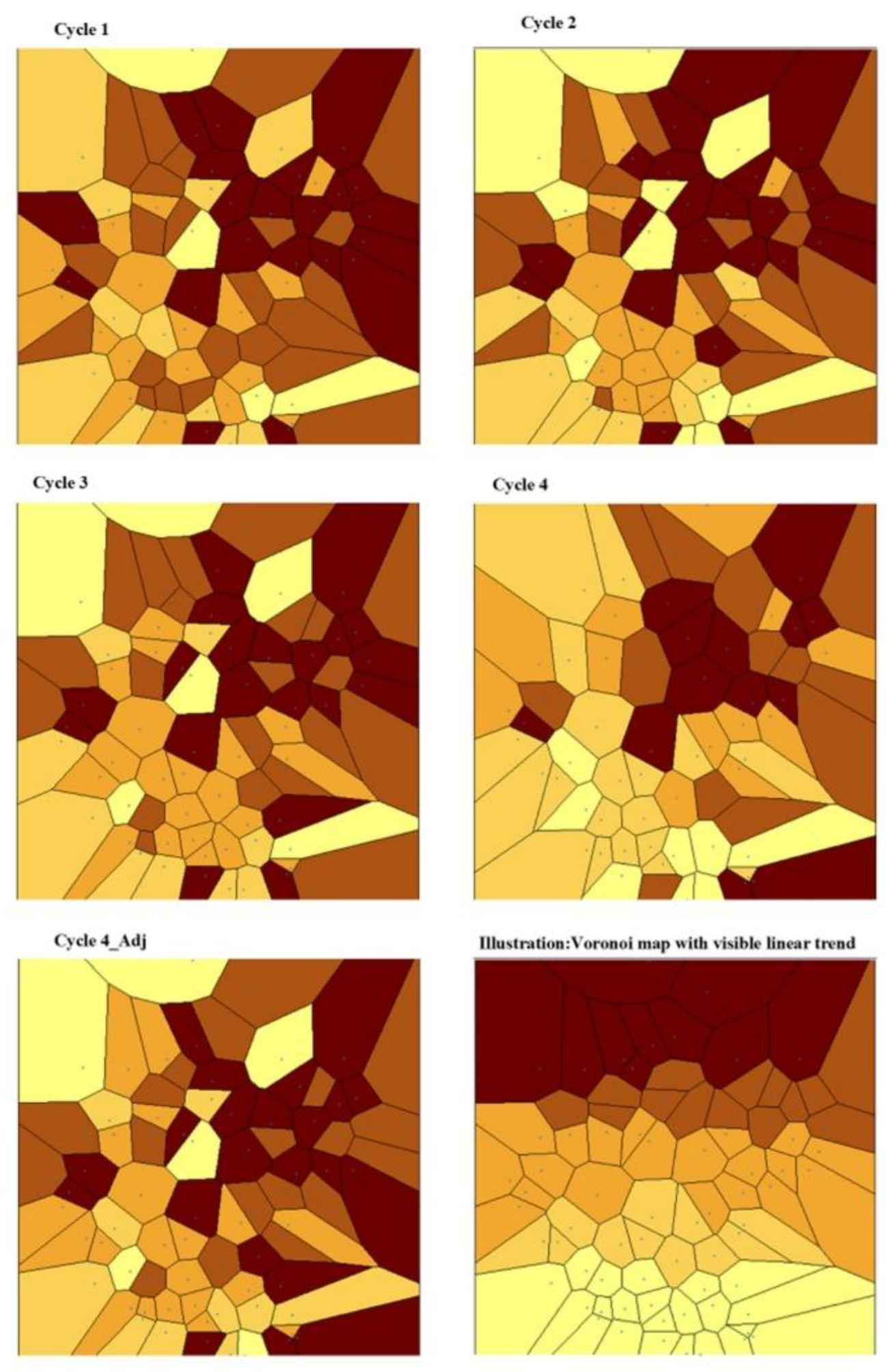

2.2.5. Kriging Map Generation

2.2.6. Limitation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

3.2. Experimental Semi-Variogram

3.3. Cross-Validation

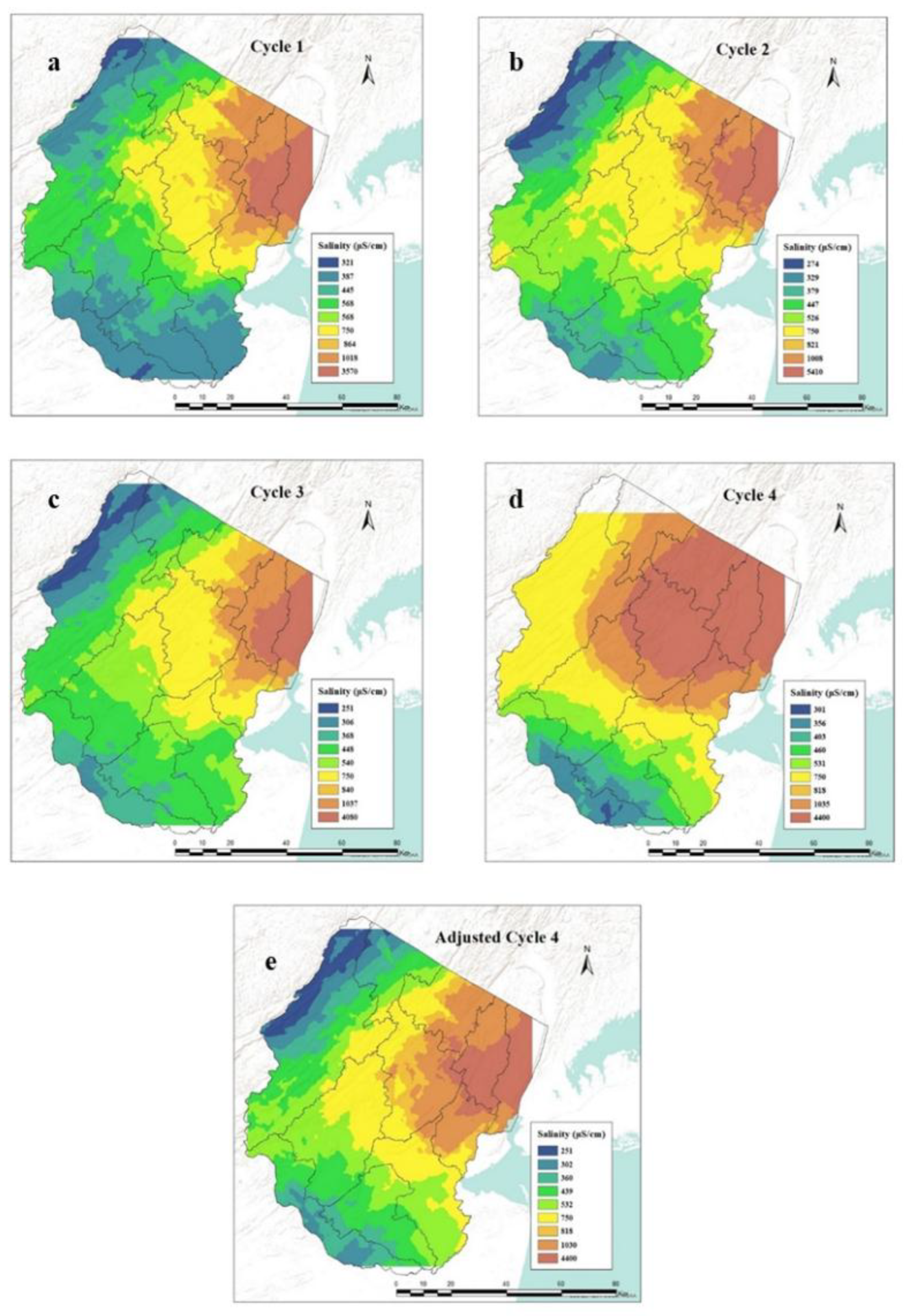

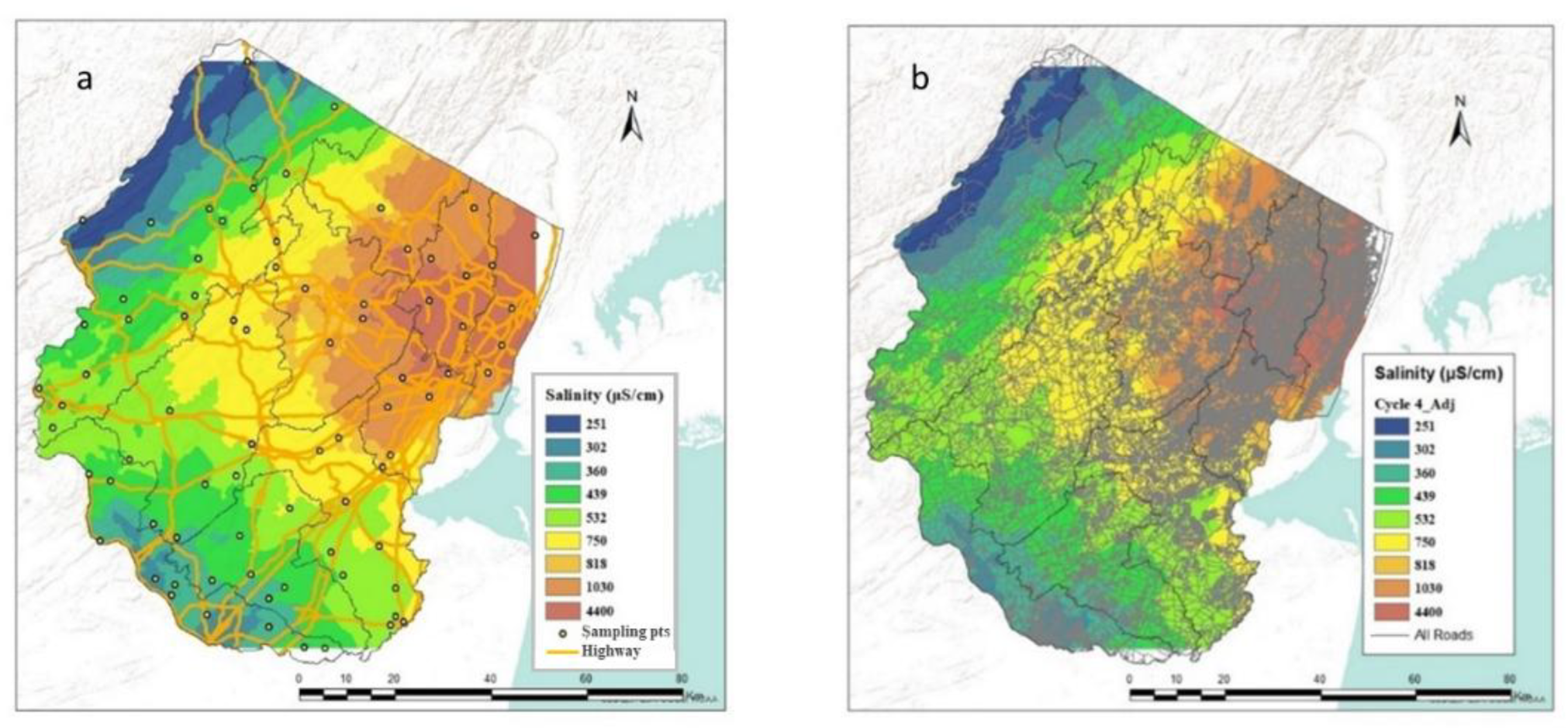

3.4. Kriging Map Generation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dieter, C. A., Maupin, M. A., Caldwell, R. R., Harris, M. A., Ivahnenko, T. I., Lovelace, J. K., Barber, N. L., & Linsey, K. S., Estimated use of water in the United States in 2015, U.S. Geological Survey Circular 2018, 1441, 65. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Almazah, M. M. A., EIlahi, A., Niaz, R., Al-Rezami, A. Y., and Zaman, B., Spatial interpolation of water quality index based on Ordinary kriging and Universal kriging, Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2023, 14, 1. [CrossRef]

- Maupin, M. A., Kenny, J. F., Hutson, S. S., Lovelace, J. K., Barber, N. L., and Linsey, K. S., Estimated use of water in the United States in 2010, U.S. Geological Survey Circular 2014, 1405, 56. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, T. E., Dennehy, K. F., Alley, W. M., and Cunningham, W. L., Ground-Water Availability in the United States, U.S. Geological Survey Circular 2008, 1323, 70 Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1323/pdf/Circular1323_book_508.pdf.

- Kaushal, S. S., Likens, G. E., Pace, M. L., Reimer, J. E., Maas, C. M., Galella, J. G. … Woglo, S. A. Freshwater salinization syndrome: from emerging global problem to managing risks,” Biogeochemistry 2021 154:2, 255–292, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sathe, S. S., and Mahanta, C., Groundwater flow and arsenic contamination transport modeling for a multi aquifer terrain: Assessment and mitigation strategies, J Environ Manage 2019, 231, 166–181. [CrossRef]

- Serfes, M., Bousenberry, R., and Gibs, J., New Jersey Ambient Ground Water Quality Monitoring Network: Status of shallow ground-water quality, 1999-2004, Geological Survey Information Circular 2007. Available: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1408/ML14086A280.pdf.

- Lindsey, B. D., Fleming, B. J., Goodling, P. J., and Dondero, A. M., Thirty years of regional groundwater-quality trend studies in the United States: Major findings and lessons learned, J Hydrol (Amst) 2023, 627, 130427. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey, Groundwater Quality, U.S. Geological Survey Water Science School, 2025. Available: https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/groundwater-quality.

- Kaushal, S. S., Groffman, P. M., Likens, G. E., Belt, K. T., Stack, W. P., Kelly V. R. … Fisher, G. T., Increased salinization of fresh water in the northeastern United States, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 38, 13517–13520. [CrossRef]

- Novotny, E. V., Sander, A. R., Mohseni, O., and Stefan, H. G., Chloride ion transport and mass balance in a metropolitan area using road salt, Water Resour Res 2009, 45, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ophori, D., Firor, C., and Soriano, P., Impact of road deicing salts on the Upper Passaic River Basin, New Jersey: a geochemical analysis of the major ions in groundwater, Environ Earth Sci 2019, 78, 16, 1–13.

- Novotny, V., Muehring, D., Zitomer, D. H., Smith, D. W., and Facey, R., Cyanide and metal pollution by urban snowmelt: impact of deicing compounds, Water Science and Technology 1998, 38, 10, 223–230. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D., Preliminary studies on mercury solubility in the presence of iron oxide phases using static headspace analysis, Environmental Geosciences 2003, 10, 4, 151–155, Dec. [CrossRef]

- Bolen W, P., Mineral Commodity Summaries, U.S. Geological Survey 2020.

- New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), Winter Readiness, Expenditures, About NJDOT, NJDOT 2018, Available: https://www.nj.gov/transportation/about/winter/expenditures.shtm.

- NJDOT, New Jersey’s Roadway Mileage and Daily VMT by Functional Classification Distributed by County, NJDOT 2020, Available: https://www.nj.gov/transportation/refdata/roadway/pdf/hpms2019/VMTFCC_19.pdf.

- Harwell, M. C., Surratt, D. D., Barone, D. M., and Aumen, N. G., Conductivity as a tracer of agricultural and urban runoff to delineate water quality impacts in the northern Everglades, Environ Monit Assess 2008, 147, 1–3, 445–462. [CrossRef]

- Hems, J. D., Study and interpretation of the chemical characteristics of natural water, 3rd ed. U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper, 1985. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/wsp2254/pdf/wsp2254a.pdf.

- McCleskey, R. B., New method for electrical conductivity temperature compensation, Environ Sci Technol 2013, 47, 17, 9874–9881.

- U.S. Geological Survey, Specific conductance: U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods, book 9, chap. A6.3, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, I., Gilfedder, B., and Hofmann, H., Contrasts between estimates of baseflow help discern multiple sources of water contributing to rivers, Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2014, 18, 1, 15–30, Jan. [CrossRef]

- Clean Water Team (CWT), Electrical conductivity/salinity Fact Sheet, FS-3.1.3.0(EC). in: The Clean Water Team Guidance Compendium for Watershed Monitoring and Assessment, California State Water Resources Control Board 2004.

- Balachandar, D., Sundararaj, P., Murthy, K., and Kumaraswamy, K., An Investigation of Groundwater Quality and Its Suitability to Irrigated Agriculture in Coimbatore District, Tamil Nadu, India - A GIS Approach, International Journal on Environmental Sciences 2010, 1, 176-190.

- US EPA, 5.9 Conductivity | Monitoring & Assessment. US EPA 2012, Available: https://archive.epa.gov/water/archive/web/html/vms59.html.

- United States Salinity Laboratory Staff (USSL), Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkaline Soils, Soil Science Society of America Journal 1954, 18, 3, 348–348. [CrossRef]

- Raritan Basin Watershed Management Project, Raritan Basin: Portrait of a Watershed. New Jersey Water Supply Authority – Watershed Protection Programs, 2002. Available: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/17036/.

- Lathrop, R. G., Measuring Land Use Change in New Jersey: Land Use Update to Year 2000, A Report on Recent Development Patterns 1995 to 2000, Grant F. Walton Center for Remote Sensing & Spatial Analysis (CRSSA) 2004, 17-2004-1. Available: https://crssa.rutgers.edu/projects/lc/docs/landuse_upd.pdf.

- Arslan, H., Spatial and temporal mapping of groundwater salinity using ordinary kriging and indicator kriging: The case of Bafra Plain, Turkey, Agric Water Manag 2012, 113, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Belkhiri, L., Tiri, A., and Mouni, L., Spatial distribution of the groundwater quality using kriging and Co-kriging interpolations, Groundw Sustain Dev 2020, 11, 100473. [CrossRef]

- Elubid, B. A., Ahmed, E. H., Zhao, J., Elhag, K. M., Abbass, W., and Babiker, M. M., Geospatial Distributions of Groundwater Quality in Gedaref State Using Geographic Information System (GIS) and Drinking Water Quality Index (DWQI), Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 5, 731. [CrossRef]

- Gharbia, A. S., Gharbia, S. S., Abushbak, T., Wafi, H., Aish, A., Zelenakova, M. & Pilla, F., Groundwater Quality Evaluation Using GIS Based Geostatistical Algorithms, Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection 2016, 04, 02, 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. D., Nandi, A., Joyner, T. A., and Luffman, I., Iron and Manganese in Groundwater: Using Kriging and GIS to Locate High Concentrations in Buncombe County, North Carolina, Groundwater 2018, 56, 1, 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Heap, A. D., Potter, A., Huang, Z., and Daniell, J. J., Can we improve the spatial predictions of seabed sediments? A case study of spatial interpolation of mud content across the southwest Australian margin, Cont Shelf Res 2011, 31, 13, 1365–1376. [CrossRef]

- Jalan, S., Chouhan, D. S., and Chaure, S., Geospatial Analysis of Spatial Variability of Groundwater Quality Using Ordinary Kriging: A Case Study of Dungarpur Tehsil, Rajasthan, India, Journal of Geomatics 2022, 16, 2, 176–187. [CrossRef]

- Van Beers, W. C. M., and Kleijnen, J. P. C., Kriging Interpolation in Simulation: A Survey, in Proceedings of the 2004 Winter Simulation Conference, R. G. Ingalls, M. D. Rossetti, J. S. Smith, and B. A. Peters, Eds., 2004. Available: https://informs-sim.org/wsc04papers/014.pdf.

- Tyagi, A., and Singh, P., Applying Kriging Approach on Pollution Data Using GIS Software, International Journal of Environmental Engineering and Management 2013, 4, 3, 185–190, Available: http://www.ripublication.com/ijeem.htm.

- Siska, P. P., and Hung, I., Assessment of Kriging Accuracy in the GIS Environment, in The 21st Annual ESRI International User Conference, San Diego, CA, 2001, Available: https://proceedings.esri.com/library/userconf/proc01/professional/papers/pap280/p280.htm.

- Royle, J. A., and Nichols, J. D., Estimating Abundance from Repeated Presence-Absence Data or Point Counts - Tulane University, Ecology 2003, 84, 3, 777–790, Available: https://library.search.tulane.edu/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=cdi_proquest_miscellaneous_18770213&context=PC&vid=01TUL_INST:Tulane&lang=en&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&adaptor=Primo%20Central&query=null,,PDF,AND&facet=citing,exact,cdi_FETCH-LOGICAL-c2640-4cc3ab70d55b63c5a41a56af47e37e4d20dae7847301f73cc0489de23a2d78ec3&offset=2.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, New Jersey’s Watersheds, Watershed management Areas and Water Regions, NJDEP Division of Watershed Management 1997. Available: https://dep.nj.gov/earthday/timeline/m1997/.

- Watt, M. K., A Hydrologic Primer for New Jersey Watershed Management, USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report, West Trenton, New Jersey, 2000. Available: https://pubs.usgs.gov/wri/2000/4140/report.pdf.

- Dalton, R. F., Monteverde, D. H., Sugarman, P. J., and Volkert, R. A., Bedrock Geologic map of New Jersey, New Jersey Geological Survey 2014. Available: https://www.nj.gov/dep/njgs/pricelst/Bedrock250.pdf.

- Drake, A. A., Jr., Volkert, R. A., Monteverde, D. H., Herman, G. C., Houghton, H. F., Parker, R. A., & Dalton, R. F., Bedrock geologic map of northern New Jersey, U. S. Geological Survey 1997. [CrossRef]

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Bedrock Geologic Map of New Jersey and Bedrock Geology of New Jersey, NJDEP – New Jersey Geological and Water Survey - U. S. Geological Survey 2016. Available: https://www.nj.gov/dep/njgs/enviroed/freedwn/psnjmap.pdf.

- Dalton, R., Physiographic Provinces of New Jersey, New Jersey Geological Survey Informational Circular 2003. Available: https://www.nj.gov/dep/njgs/enviroed/infocirc/provinces.pdf.

- Bousenberry, R., New Jersey Ambient Ground Water Quality Monitoring Network: New Jersey Shallow Ground-Water Quality, 1999 – 2008, New Jersey Geological and Water Survey Information Circular 2016. Available: https://www.nj.gov/dep/njgs/enviroed/infocirc/NJAGWQMN.pdf.

- R – Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria 2023.

- QGIS.org, QGIS Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project, n.d. Available: https://qgis.org/.

- ESRI, ArcGIS Pro: Understanding how to remove trends from the data, ESRI – ArcGIS n.d. Available: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/help/analysis/geostatistical-analyst/understanding-how-to-remove-trends-from-the-data.htm.

- Almodaresi, S. A., Mohammadrezaei, M., and Dolatabadi, M., Qualitative Analysis of Groundwater Quality Indicators Based on Schuler and Wilcox Diagrams: IDW and Kriging Models, J Environ Health Sustain Dev 2019, 4, 4, 903–915. [CrossRef]

- Boudibi, S., Sakaa, B., and Zapata-Sierra, A. J., Groundwater Quality Assessment Using GIS, Ordinary Kriging and WQI in an Arid Area, PONTE International Scientific Researchs Journal 2019, 75, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hengl, Tomislav, A Practical Guide to Geostatistical Mapping of Environmental Variables. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; JRC38153, 2007. Available: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC38153.

- Johnston, K., Ver Hoef, J. M., Krivoruchko, K., and Lucas, N., Using ArcGIS geostatistical analyst: GIS by ESRI, Redlands, California: Esri Press, 2001.

- Krivoruchko, K., Spatial statistical data analysis for GIS users, 1st ed. Redlands, California: Esri Press, 2011.

- Bajjali, W., ArcGIS for Environmental and Water Issues, Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S. N., Spatial Point Pattern Analysis by using Voronoi Diagrams and Delaunay Tessellations – A Comparative Study, Biometrical Journal 2003, 45, 3, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Nayanaka, V., Vitharana, W., and Mapa, R., Geostatistical Analysis of Soil Properties to Support Spatial Sampling in a Paddy Growing Alfisol, Tropical Agricultural Research 2011, 22, 1, 34. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. O., Spatial evaluation of groundwater quality using factor analysis and geostatistical Kriging algorithm: a case study of Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria, Water Pract Technol 2023, 18, 3, 592–607. [CrossRef]

- Al-Omran, A. M., Aly, A. A., Al-Wabel, M. I., Al-Shayaa, M. S., Sallam, A. S., and Nadeem, M. E., Geostatistical methods in evaluating spatial variability of groundwater quality in Al-Kharj Region, Saudi Arabia, Appl Water Sci 2017, 7, 7, 4013–4023. [CrossRef]

- Trangmar, B. B., Yost, R. S., and Uehara, G., Application of Geostatistics to Spatial Studies of Soil Properties, Advances in Agronomy 1985, 38, 45–94. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C. D., Local models for spatial analysis, 2nd ed. CRC Press, 2010.

- Jarmołowski, W., Wielgosz, P., Ren, X., and Krypiak-Gregorczyk, A., On the drawback of local detrending in universal kriging in conditions of heterogeneously spaced regional TEC data, low-order trends and outlier occurrences, J Geod 2021, 95, 1, 2. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M. L., Kremer, P., Cravotta, C. A., Seng, K. E., and Goldsmith, S. T., Land development and road salt usage drive long-term changes in major-ion chemistry of streamwater in six exurban and suburban watersheds, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1999–2019, Front Environ Sci 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Marghade, D., Malpe, D. B., and Subba Rao, N., Identification of controlling processes of groundwater quality in a developing urban area using principal component analysis, Environ Earth Sci 2015, 74, 7, 5919–5933. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Huffine, M., Husch, J., and Sinpatanasakul, L., Na/Cl molar ratio changes during a salting cycle and its application to the estimation of sodium retention in salted watersheds, J Contam Hydrol 2012, 136–137, 96–105. [CrossRef]

| Sampling cycles | SC | Log SC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | mean | 755.28 | 2.718 |

| n =76 | median | 485 | 2.686 |

| skewness | 2.1455 | -0.2679 | |

| kurtosis | 8.1825 | 3.039 | |

| Cycle 2 | mean | 799.03 | 2.717 |

| n =77 | median | 494 | 2.694 |

| skewness | 2.9129 | -0.362 | |

| kurtosis | 13.645 | 3.773 | |

| Cycle 3 | mean | 759.53 | 2.7043 |

| n =76 | median | 487 | 2.687 |

| skewness | 2.4312 | -0.50483 | |

| kurtosis | 9.8845 | 3.7461 | |

| Cycle 4 | mean | 955.66 | 2.8261 |

| n =65 | median | 577 | 2.761 |

| skewness | 1.616 | 0.00639 | |

| kurtosis | 5.9171 | 2.3403 | |

| Cycle 4Adj | mean | 848.27 | 2.7319 |

| n =77 | median | 527 | 2.7218 |

| skewness | 1.756 | -0.44241 | |

| kurtosis | 6.5282 | 3.1793 |

| Sampling cycles | MSE | RMSSE | RMSE | ASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | - 0.0096 | 1.0899 | 0.3706 | 0.3347 |

| Cycle 2 | - 0.01329 | 1.1382 | 0.4148 | 0.3576 |

| Cycle 3 | - 0.00997 | 1.1478 | 0.4095 | 0.3496 |

| Cycle 4 | - 0.01506 | 1.0265 | 0.3254 | 0.3165 |

| Cycle 4_Adj | - 0.01296 | 1.1094 | 0.4309 | 0.3824 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).