Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definitions and Frameworks

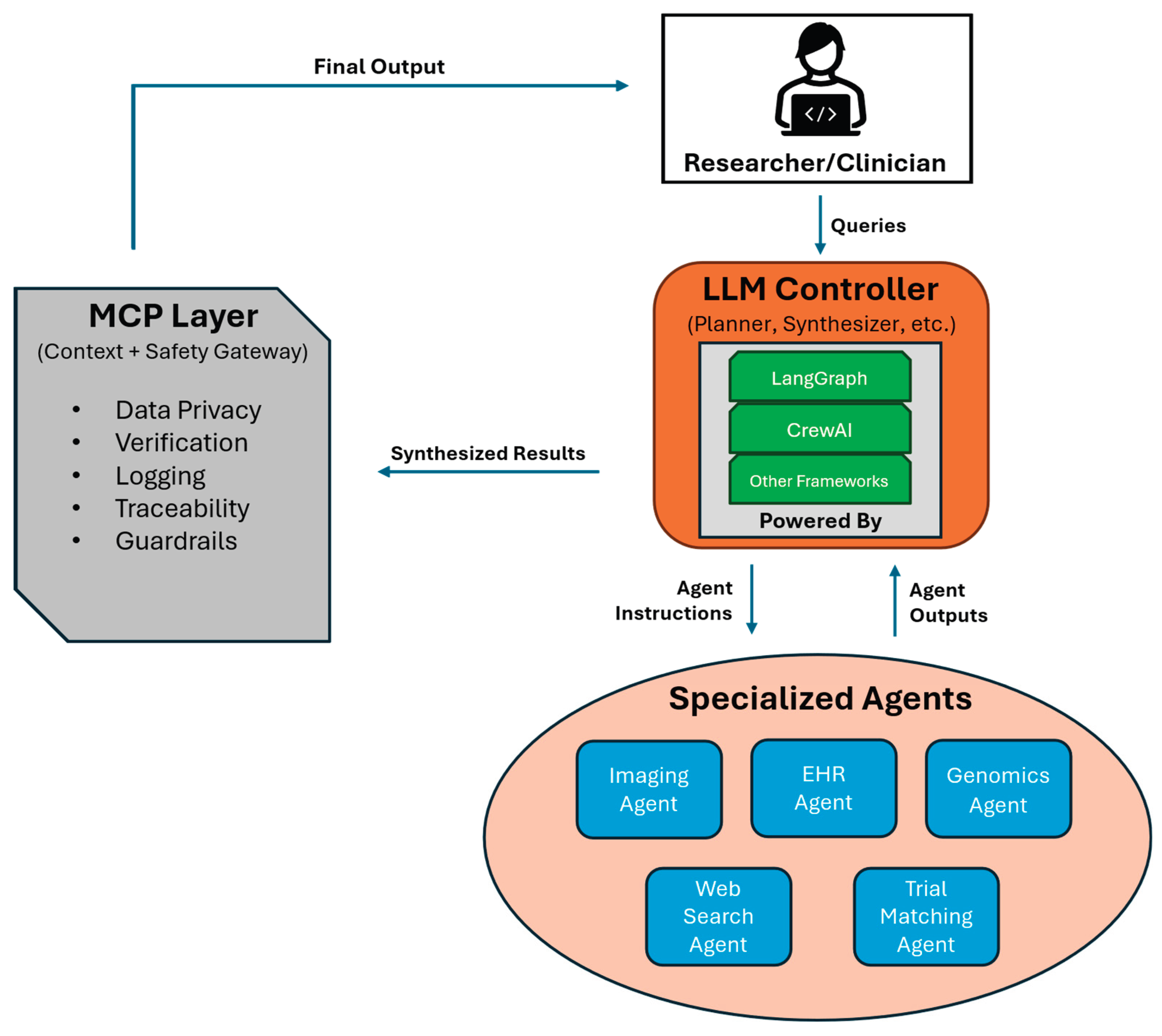

2.1. Agent Definitions and Orchestration Frameworks

2.2. Memory, Guardrails, and Communication Protocols

3. State of the Art in Biomedicine

3.1. Basic Science Applications

3.1.1. Drug Discovery and Pharmacology

3.1.2. Bioinformatics and Multi-Omics Analysis

3.1.3. Cancer Biology

3.2. Clinical Applications

3.2.1. Medical Imaging and Multimodal Diagnosis

3.2.2. Clinical Trials and Evidence Synthesis

3.2.3. Clinical Decision Support and Physician Assistants

4. Opportunities and Underutilized Domains

5. Platforms and Benchmarks

6. Challenges and Future Directions

6.1. Reliability, Verification, and Safety

6.2. Scalability and Efficiency

6.3. Continual Learning and Adaptation

6.4. Ethics, Regulation, and Trust

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Feng, X.; et al. A survey on large language model based autonomous agents. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 18(1), 186345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zeng, S.; Yang, Y. A survey on LLM-based multi-agent systems: workflow, infrastructure, and challenges. Vicinagearth 2024, 1(9), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Chen, W.; Guo, X.; et al. The rise and potential of large language model based agents: a survey. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68(2), 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Fang, A.; Huang, Y.; et al. Empowering biomedical discovery with AI agents. Cell 2024, 187(22), 6125–6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, S.K.; Wrøbel, J.; Ciorba, F.M. Multi-agent text mining: an approach to automated literature analysis in life sciences. PLoS One 2020, 15(2), e0229923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, O.; Johansson, F.; Komorowski, M.; et al. Guidelines for reinforcement learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, M.; Jennings, N.R. Intelligent agents: theory and practice. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 1995, 10(2), 115–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.; Veloso, M. Multiagent systems: a survey from a machine learning perspective. Auton. Robots 2000, 8, 345–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; et al. A survey on multi-agent orchestration frameworks for AI. J. Syst. Archit. 2023, 142, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Fei, Y.; et al. Coordinating multiple LLM-based agents via message exchange: architectures and open challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09327. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. HuggingGPT: solving AI tasks with ChatGPT and its friends in HuggingFace. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17580. [Google Scholar]

- Solving AI tasks with ChatGPT and its friends in HuggingFace (OpenReview Poster). NeurIPS. 2023. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=tgM9dpXQbd (accessed on 1 Oct 2023).

- Wu, S.; Yang, D.; Leng, Y.; et al. AutoGen: enabling next-gen LLM applications via multi-agent conversation frameworks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01524. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liang, J.; Shen, X.; et al. CAMEL: communicator agent framework for multi-agent role-playing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17760. [Google Scholar]

- Derouiche, H.; Brahmi, Z.; Mezni, H. Agentic AI Frameworks: Architectures, Protocols, and Design Challenges . arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Exploration of LLM Multi-Agent Application Implementation Based on LangGraph+CrewAI . arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18241. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, L.; et al. LangChain-Agent: a framework for building multi-agent LLM applications. SoftwareX 2024, 21, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, D.; et al. ReAct: synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 30636–30650. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Bitton, J.; et al. Toolformer: language models can teach themselves to use tools. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; et al. Self-consistency improves chain-of-thought reasoning in language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.11171. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, D.; et al. Tree of thoughts: deliberative reasoning via explicit tree-based planning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10601. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, N.; Labash, M.F.; Tran, T. Reflexion: an autonomous agent with dynamic memory and self-reflection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11366. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, D.; Baral, C.; Huang, S.; et al. Self-refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 3940–3955. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, L.; Zhou, Y. A call for critic models: aligning large language models via self-generated feedback. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.12009. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, R.; Tuyls, K.; Mann, T.; et al. Zero-shot coordination for multi-agent reinforcement learning. ICML 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Safeguarding sensitive data in multi-agent systems: improving Google A2A protocol. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12490. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Announcing the Agent2Agent (A2A) Protocol – a new era of agent interoperability. Google AI Blog. 2023. Available online: https://developers.googleblog.com/2023/09/a2a-a-new-era-of-agent-interoperability.html (accessed on 1 Oct 2023).

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Agent-SafetyBench: evaluating the safety of multi-agent AI systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.00081. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mirchandani, P.; Nayak, A.; Natarajan, S. Cooperative multi-agent systems for biomedical applications: a review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 14, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPCR-Nexus: Multi-Agent Orchestration for Knowledge Retrieval. biorxiv. 2025. Available online: https://submit.biorxiv.org/submission/pdf?msid=BIORXIV/2025/696782.

- Gao, S.; Xie, Z.; Fang, A.; et al. TxAgent: an AI agent for therapeutic reasoning across a universe of tools. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Fang, A.; Huang, Y.; et al. Kempner Institute – TxAgent: AI for therapeutic reasoning (blog). Medium. 5 July 2025. Available online: https://medium.com/@kempnerinstitute/txagent-an-ai-agent-for-therapeutic-reasoning-5bd771d554e5 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Su, H.; Feng, J.; Lu, Y.; et al. BioMaster: multi-agent system for automated bioinformatics analysis workflows. SSRN preprint 5433777; Patterns (under review). 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Feng, J.; Lu, Y.; et al. BioMaster: multi-agent framework for omics workflows (preprint). bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, D.; El Nahhas, O.S.M.; Wölflein, G.; et al. Development and validation of an autonomous artificial intelligence agent for clinical decision-making in oncology. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Editorial: AI agents for oncology decision-making. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 1307–1308. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yi, H.; You, M.; et al. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agent conversational LLMs. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yi, H.; Li, J. Multi-Agent Conversation framework markedly improves medical diagnosis (News). FSU News. 12 May 2025. Available online: https://news.fsu.edu/2025/05/12/fsu-researchers-study-ai-differential-diagnosis-accuracy (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Jin, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gong, C.; et al. Matching patients to clinical trials with large language models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Basu, A.; Nievas, M.; et al. PRISM: Patient Records Interpretation for Semantic clinical trial Matching using LLMs. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7(1), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lai, Y.; Ren, J.; et al. Agent Hospital: a simulacrum of hospital with evolvable medical agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2405.02957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, C.; Jeong, H.; et al. MDAgents: an adaptive collaboration of LLMs for medical decision-making. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.15155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlagi, M.; Chakraborty, I.; Pandya, B.; et al. DORA: a dual-agent system for hypothesis generation in biomedical research. Proc. ACM Int. Conf. Bioinformatics 2023, 12, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitnik, M.; Bean, D.M.; Day, M.; et al. Rise of the AI scientists. Nature 2023, 620, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsentzer, E.; Li, M.M.; Kobren, S.N.; et al. Few shot learning for phenotype-driven diagnosis of patients with rare genetic diseases. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; et al. MedAgentBoard: evaluating multi-agent LLM collaboration for medical training. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00123. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Zhang, A.; Kolouri, S.; et al. AI tutor agents in medical education: a multi-agent role-playing approach. IEEE Conf. Technol. Learn. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Shi, C.; Cai, X.; et al. Lifelong learning of large language model-based agents: a roadmap. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.07278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialon, G.; Xu, B.; Eidnes, L.; et al. Augmented language models: a survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.07842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Doshi, P.; Gholami, S.; et al. Threats without vulnerabilities: evaluating attack surfaces of LLM-based autonomous agents. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12345. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, W.; et al. AI agents vs. agentic AI: taxonomy, applications, and safety implications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07282. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Azhangal, A.; Chakraborty, S.; et al. Scamlexity: exploring malicious autonomy in agentic AI browsers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00567. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Ehtesham, A.; Kumar, S.; Khoei, T. T. A Survey of the Model Context Protocol (MCP): Standardizing Context to Enhance LLMs . Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Model Context Protocol (MCP): Landscape, Security Threats, and Future Research Directions . arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.23278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. High-Level Expert Group on AI, 2019. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 5 Jul 2025).

- U.S. FDA. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to AI/ML-based software as a medical device (Discussion Paper). FDA Digital Health Center of Excellence, 2019. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/122535/download (accessed on 5 Jul 2025).

- Sullivan, H.R.; Schweikart, S.J. Are current tort liability doctrines adequate for addressing injury caused by AI? AMA J. Ethics 2019, 21(2), E160–E166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, M.J. Ethical dimensions of using artificial intelligence in health care. AMA J. Ethics 2019, 21(2), E121–E124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).