Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- to construct a computationally efficient yet physically representative 3D model of a vapor chamber using coupled flow and heat transfer physics;

- to quantify thermal spreading and peak temperature reduction under representative chip-level heating;

- to analyze internal temperature, velocity, and pressure fields for improved physical understanding; and

- to establish a modeling framework, with clearly stated assumptions, that can be extended for parametric studies involving geometry, wick properties, and working-fluid selection.

2. Methods and Materials

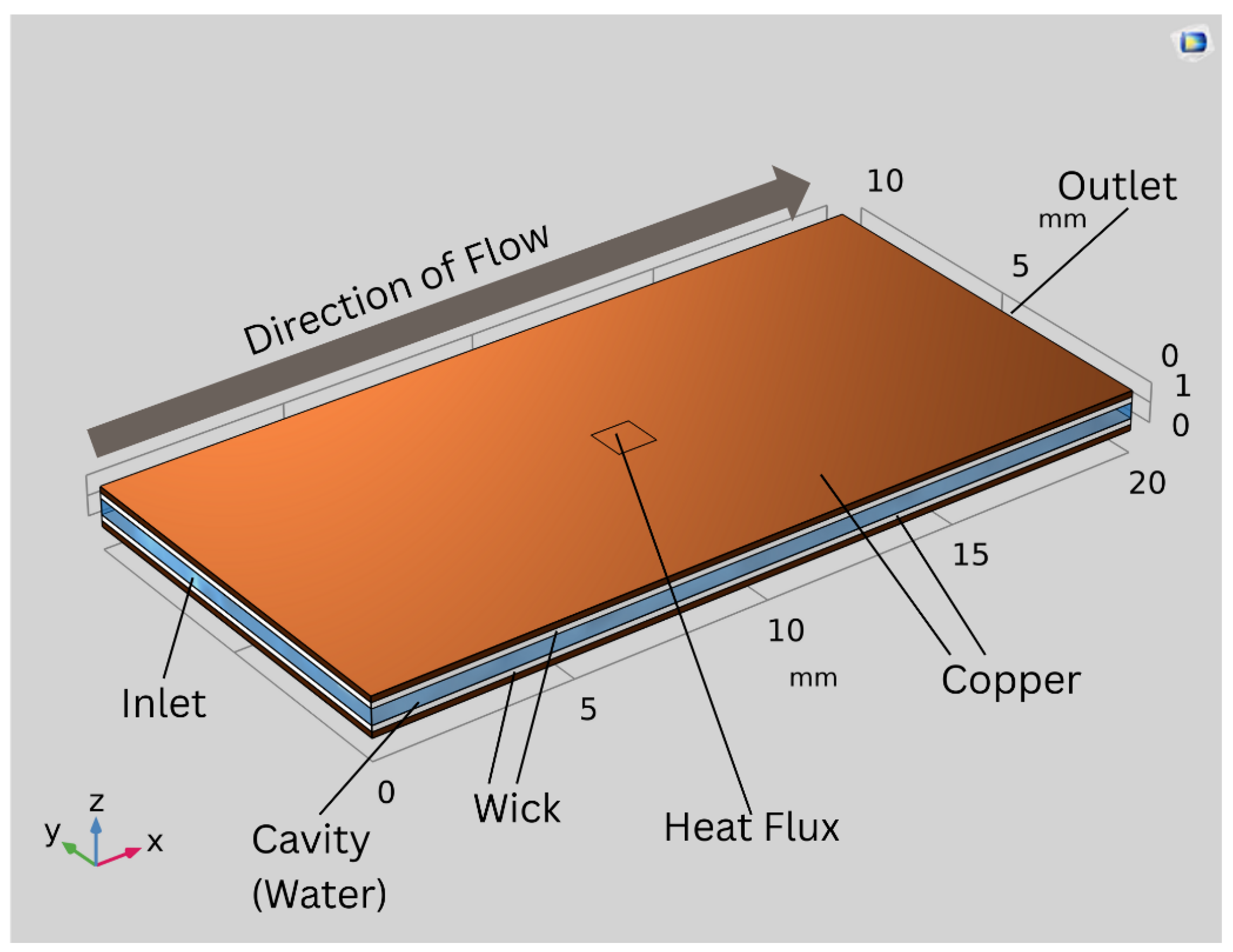

2.1. Model Geometry and Simplifications

| Quantity | Layer name | Material | Thickness (mm) |

| 2 | Copper shell | Copper (solid) | 0.3 |

| 2 | Wick | Porous copper (68% porosity) | 0.3 |

| 1 | Cavity | Water (vapor) | 0.4 |

2.2. Governing Equations

2.2.1. Heat Transfer in Solids and Fluids

2.2.2. Laminar Flow in the Vapor Cavity

2.2.3. Brinkman Flow in the Porous Wick

2.2.4. Effective Thermal Conductivity of the Wick

2.3. Multiphysics Couplings and Boundary Conditions

2.3.1. Nonisothermal Flow

2.3.2. Heat Input and Phase-Change Treatment

- evaporation: liquid absorbs heat to form vapor, acting as a local heat sink in the wick;Table 2. Material properties used in the COMSOL model.

Material Property Symbol Value Units Source Copper (solid) Density 8960 SIkg.m -3 [30] Copper (solid) Specific heat 385 SIJ.kg-1.K-1 [30] Copper (solid) Thermal conductivity k 400 SIW.m-1.K-1 [30] Water (liquid) Density 997 SIkg.m-3 [30] Water (liquid) Specific heat 4180 SIJ.kg-1.K-1 [30] Water (liquid) Thermal conductivity k 0.6 SIW.m-1.K-1 [30] Water (liquid) Dynamic viscosity SIPa.s [30] Water (vapor) Density 0.554 SIkg.m-3 [30] Water (vapor) Specific heat 2010 SIJ.kg-1.K-1 [30] Water (vapor) Thermal conductivity k 0.026 SIW.m-1.K-1 [30] Water (vapor) Dynamic viscosity SIPa.s [30] Porous wick Porosity 0.68 – assumed/design value Porous wick Permeability SIm2 estimated Porous wick Effective conductivity 64.02 SIW.m-1.K-1 from Eq. (6) - condensation: vapor releases heat upon liquefaction, acting as a local heat source at the condenser side.

2.3.3. Convective Cooling and Wall Conditions

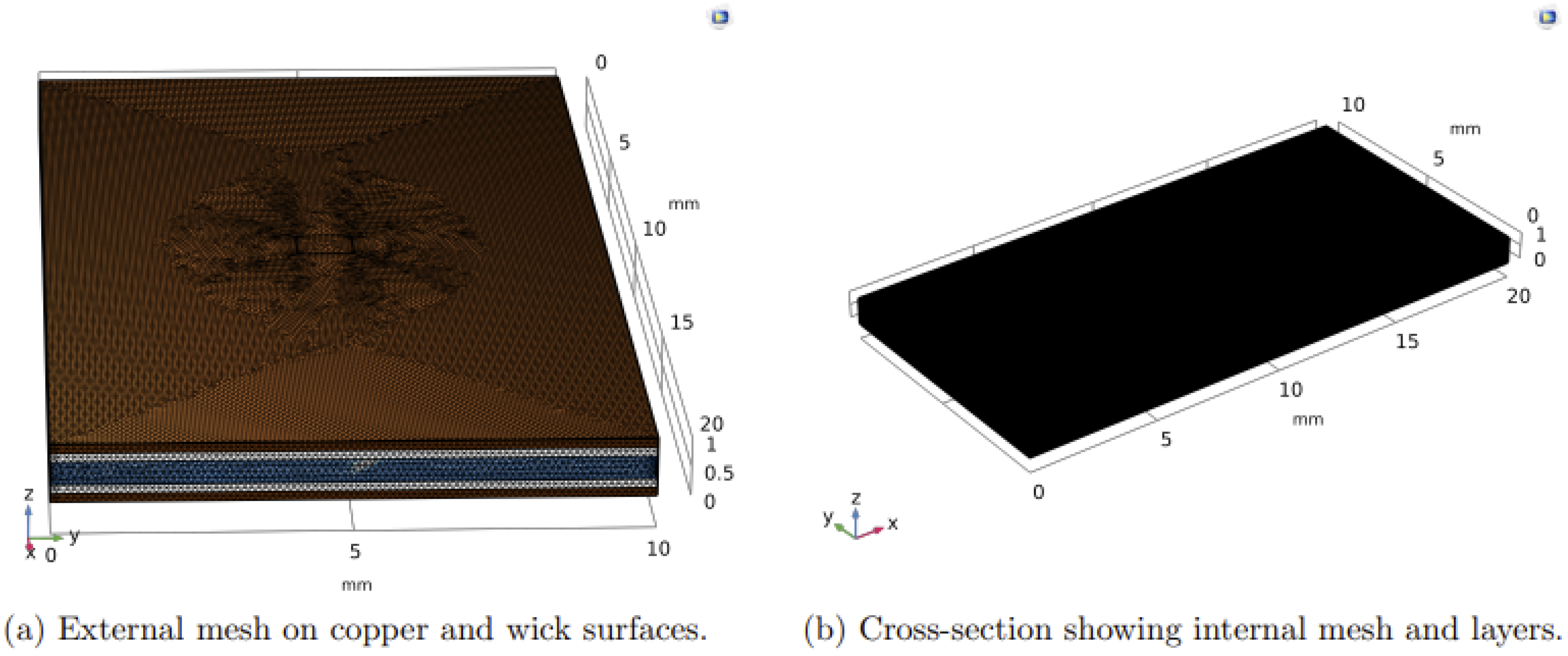

2.4. Mesh Configuration

2.5. Solver Setup

3. Results and Discussion

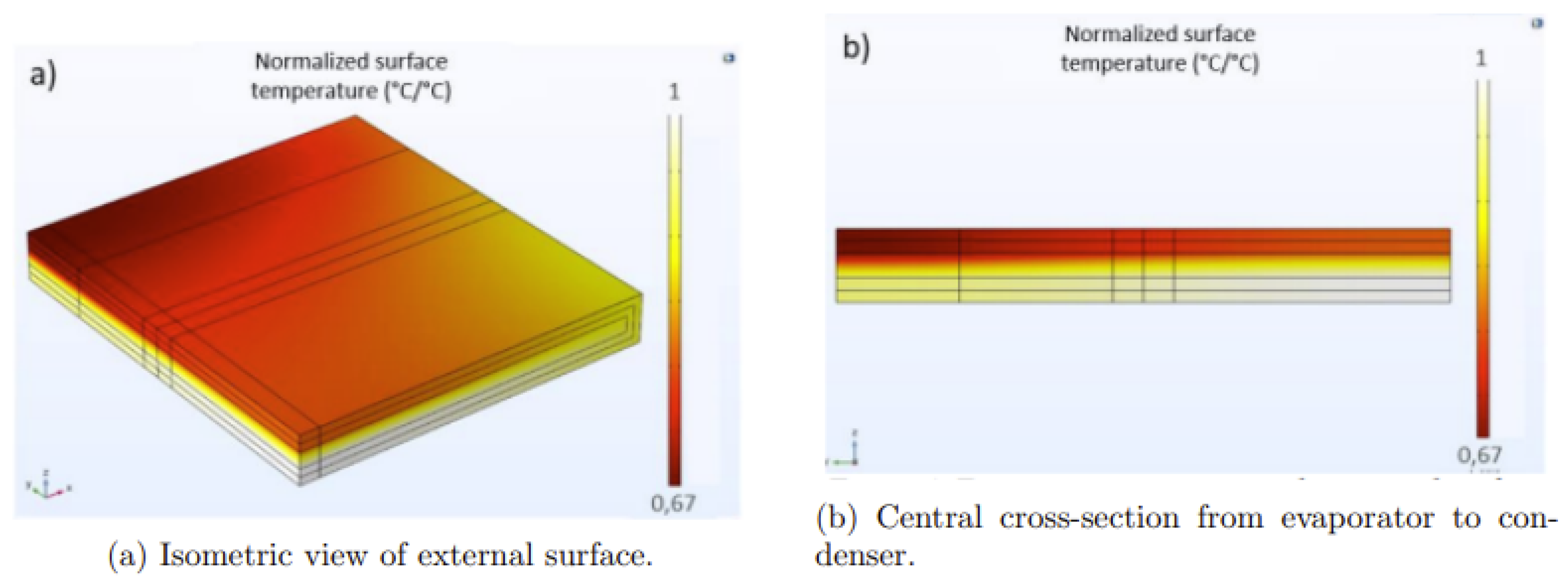

3.1. Surface Temperature Distribution

3.2. Thermal Circuit Interpretation

3.3. Effective Thermal Conductivity

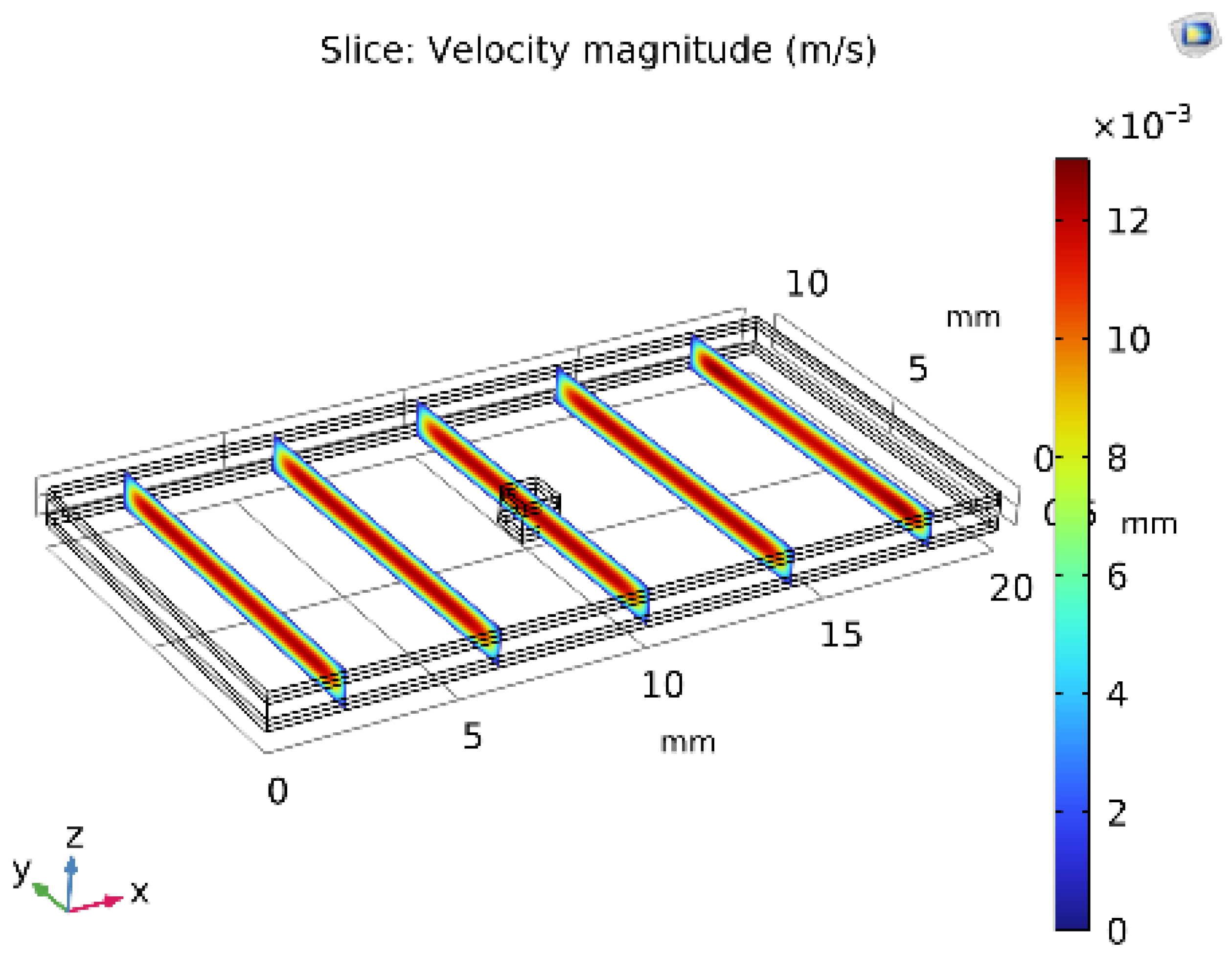

3.4. Velocity Field and Phase-Change-Driven Flow

3.5. Pressure Distribution

4. Conclusions

References

- Bar-Cohen, A. Thermal management of microelectronics in the 21st century. Electronics Cooling 1999, 5, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, R.; Chiu, C.-P.; Chrysler, G. Cooling a microprocessor chip. Proceedings of the IEEE 2006, 94, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckerman, D. B.; Pease, R. F. W. High-performance heat sinking for VLSI. IEEE Electron Device Letters 1981, 2, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozisik, M. N. Heat Transfer: A Basic Approach; McGraw-Hill, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Garimella, S. V. Advances in mesoscale thermal management technologies for microelectronics. Microelectronics Journal 2006, 37, 1165–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A. G.; Viskanta, R. Three-dimensional conjugate heat transfer in the microchannel heat sink for electronic packaging. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2000, 43, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G. P. An Introduction to Heat Pipes: Modeling, Testing, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S. W.; Wu, S. C.; Chen, W. P. Experimental investigation of flat porous heat pipe for cooling electronics. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2009, 33, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. A.; Yesudasan, S.; Chacko, S. Nanofluids for solar thermal collection and energy conversion. Preprints preprint article 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yesudasan, S. The critical diameter for continuous evaporation is between 3 and 4 nm for hydrophilic nanopores. Langmuir 2022, 38, 6550–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesudasan, S. “Thermal dynamics of heat pipes with sub-critical nanopores,” arXiv:2406.xxxxx [physics.flu-dyn], 2024, arXiv preprint.

- Mohammed, M. M.; Yesudasan, S. Molecular dynamics study on the properties of liquid water in confined nanopores: Structural, transport, and thermodynamic insights. Proc. ASEE Northeast Section Conf., 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hotchandani, V.; Mathew, B.; Yesudasan, S.; Chacko, S. Thermo-hydraulic characteristics of novel MEMS heat sink. Microsyst. Technol. 2021, 27, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, T. P. Theory of heat pipes; Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, Rep. LA-3246-MS, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, F. J.; Cheng, P.; Wu, H. S.; Li, H. Y. Development of a flat plate heat pipe with wickless inner grooves. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2009, 23, 830–835. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, M.; Kandlikar, S. G.; Sozbir, N. A review of vapor chambers. Heat Transfer Engineering 2019, 40, 1551–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, J. A.; Garimella, S. V. Recent advances in vapor chamber transport characterization for high-heat-flux applications. InterSociety Conf. on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm), 2013; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, C. A. Theory of the ultimate heat transfer limit of cylindrical heat pipes. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 1973, 16, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M. H. N.; Kandlikar, S. G.; Kaladgi, S. N. S. Heat transfer and fluid flow in heat pipes. Advances in Heat Transfer 2016, 48, 373–427. [Google Scholar]

- An, J. S.; Kim, J. H.; Lee, J. W.; Chang, Y. S. Thermal performance of a vapor chamber heat sink with hybrid wick structure. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2020, 149, 119159. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Z. J.; Faghri, A. A network thermodynamic analysis of the heat pipe. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 1998, 41, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S. W.; Xie, W. L.; Wong, T. N. A three-dimensional numerical model for a vapor-chamber heat sink. Journal of Electronic Packaging 2011, 133, 011008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. Y. Review on thermal transport in high porosity metal foams. Applied Thermal Engineering 2012, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W.; Mudawar, I. Experimental and numerical study of pressure drop and heat transfer in a single-phase micro-channel heat sink. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2002, 45, 2549–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL AB, COMSOL Multiphysics® User’s Guide, Version 6.2. 2023.

- COMSOL AB, CFD Module User’s Guide, Version 6.2. 2023.

- Vasiliev, L. L. Heat pipes in modern heat exchangers. Applied Thermal Engineering 2005, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkan, U.; Garimella, S. V.; Murthy, J. Y. Transport in flat heat pipes at high heat fluxes from multiple discrete sources. Journal of Heat Transfer 2004, 126, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. X.; He, Y. L.; Tao, W. Q.; Zhao, C. Y. Numerical simulation of a vapor chamber with multi-artery wick structure. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications 2018, 74, 1173–1193. [Google Scholar]

- COMSOL AB, Heat Transfer Module User’s Guide, Version 6.2. 2023.

- Fox, R. W.; McDonald, A. T.; Pritchard, G. Introduction to Fluid Mechanics, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nield, D. A.; Bejan, A. Convection in Porous Media, 5th ed.; Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, J. C.; Kardos, J. L. The Halpin–Tsai equations: A review. Polymer Engineering & Science 1976, 16, 344–352. [Google Scholar]

- Murshed, S. M. S.; Nieto de Castro, C. A. A critical review of traditional and emerging techniques and fluids for electronics cooling. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 78, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maydanik, Y. F. Loop heat pipes. Applied Thermal Engineering 2005, 25, 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghri, A. Heat Pipe Science and Technology; Taylor & Francis, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, P. D.; Reay, D. A. Heat Pipes, 5th ed.; Pergamon Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. B.; Peterson, G. P.; Lu, X. J. The influence of vapor-liquid interactions on the liquid pressure drop in triangular microgrooves. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 1994, 37, 2211–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. L.; Jang, S. P.; Lai, C. Y. Thermal performance of flat vapor chamber with hybrid wick structure. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2017, 108, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, K. N. Heat pipe for aerospace applications—an overview. Journal of Electronics Cooling and Thermal Control 2015, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhard, J. H., IV; Lienhard, J. H., V. A Heat Transfer Textbook, 5th ed.; Phlogiston Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Patankar, S. V. Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow; Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H. K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Faghri, A.; Chang, W. S. A numerical analysis of phase-change problems including natural convection. Journal of Heat Transfer 1989, 111, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, V. S.; Dhamneya, A. K.; Mishra, S. C. Numerical investigation of the thermal performance of a vapor chamber heat sink. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2018, 132, 533–543. [Google Scholar]

| Mesh | Elements () | (SIC) | (SIW.m-1.K-1) | Rel. change |

| Coarse | 0.25 | 86.2 | 62.1 | – |

| Medium | 0.50 | 85.3 | 63.5 | 1.0% / 2.3% |

| Fine | 1.00 | 85.0 | 64.0 | 0.4% / 0.8% |

| Very fine | 2.00 | 84.9 | 64.1 | 0.1% / 0.2% |

| Position (mm) | Temperature T (SIC) |

| 0 (Evaporator) | 85.0 |

| 5 | 80.2 |

| 10 | 75.5 |

| 15 | 72.3 |

| 20 (Condenser) | 70.0 |

| Height from bottom (mm) | Velocity (m/s) |

| 0.0 | 0.00 |

| 0.1 | 0.25 |

| 0.2 | 0.45 |

| 0.3 | 0.50 |

| 0.4 | 0.40 |

| 0.5 | 0.20 |

| 0.6 | 0.00 |

| Position (mm) | Pressure (Pa) |

| 0 | 101325 |

| 5 | 101320 |

| 10 | 101315 |

| 15 | 101310 |

| 20 | 101305 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).