1. Introduction

Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) enable time-critical vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication to enhance road safety, optimize traffic flows, and support cooperative services [

1,

2]. However, high mobility, rapidly changing topologies, intermittent connectivity, and short-lived communication windows make integrity, availability, and

timely agreement difficult to achieve in practice [

3,

4]. In such environments, the core systems problem is not merely choosing a consensus algorithm but designing

governance: deciding

when and

how strongly to validate and commit information under strict V2X timeliness constraints and mobility-driven fragmentation.

Blockchain-style ledgers have been proposed to improve auditability, integrity, and coordination in VANETs, yet existing approaches typically emphasize isolated objectives: consensus performance under fixed parameters [

5,

6], entropy-inspired indicators without closed-loop control [

7], or single-algorithm evaluations under restricted conditions [

8]. What remains missing is a unified

operational framework that (i) makes injection–validation dynamics explicit under deadline constraints, (ii) measures

spatial dispersion in real time (a key driver of partitions, forks, and coherence loss), and (iii) adapts consensus regime and validation rigor to instantaneous disorder rather than relying on fixed-parameter baselines.

We model VANET ledger governance as a control loop with two antagonistic legs: (i)

message/transaction injection that increases informational disorder, and (ii)

consensus validation that consumes resources to compress disorder and improve an operational Quality-of-Information (QoI) proxy. In our notation, injection tends to increase

S (informational entropy) and is exacerbated by topology fragmentation captured by

(spatial entropy), whereas validation is the “work” leg that reduces effective disorder (rejecting stale/invalid microstates) and stabilizes convergence under deadlines. The

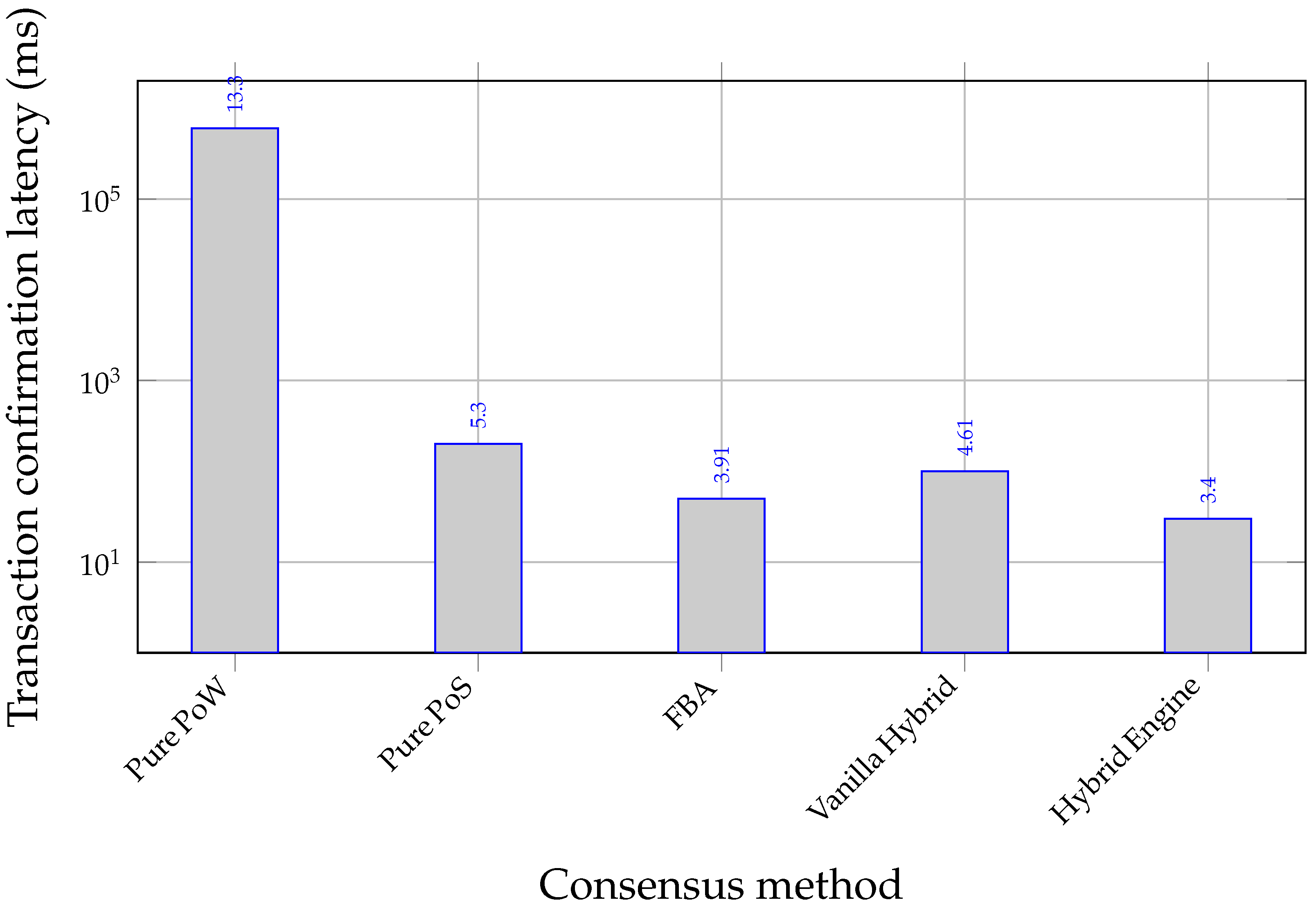

Ideal Information Cycle (

Figure 1) is therefore used strictly as an

operational governance abstraction that motivates the monotonicity/stability constraints imposed during policy-map calibration, rather than as a claim of physical thermodynamic equivalence.

We introduce two complementary constructs: the

Ideal Information Cycle and the

VANET Engine. The cycle is an operational abstraction of injection (disorder growth) and validation (disorder compression) under V2X deadlines. Building on it, the VANET Engine is a decentralized, cluster-local control loop (e.g., per intersection/segment/connected subgraph) that monitors

normalized Shannon entropies: informational entropy

S over active transactions and spatial entropy

over occupancy bins (both on

by normalization to their maxima). The Engine adapts (a) the consensus

mode (PoW vs. signature/quorum-based modes such as PoS/FBA) and (b) key rigor parameters via calibrated policy maps. Governance is cast as a constrained

operational objective trading per-block resource expenditure (radio + cryptography) against a QoI proxy derived from delay/error tiers, under timeliness and ledger-coherence pressure (formal statement in

Section 3.6.8). Cryptographic cost is made explicitly traceable through operation counts,

Our claims are limited to operational security and performance for V2X-oriented ledgers under mobility and churn, with full PHY/MAC fidelity up to

vehicles. We do not claim physical equivalence between thermodynamic and informational quantities; entropies are used strictly as measurable governance signals. Moreover, PoW targets are calibrated to be latency-feasible (to respect freshness constraints) and therefore do not provide cryptocurrency-grade majority-hash security in open permissionless settings. Security implications of the latency-feasible regimes, mode transitions, and entropy manipulation are addressed explicitly in

Section 4.

We do

not claim physical equivalence between thermodynamic variables and network measurements. Entropy is used strictly as an

operational governance signal for real-time adaptation. Our evaluation therefore focuses on measurable VANET objectives: agreement latency, per-block energy, throughput, orphan/fork rates, finality, and ledger coherence under mobility and churn. Furthermore, signature/quorum-based modes (PoS/DPoS/FBA) are interpreted in a

permissioned/consortium sense (validator sets and quorum slices are configured), consistent with realistic V2X deployments involving RSUs and credentialing. PoW, when used, operates under

latency-feasible targets required by V2X timeliness envelopes; it is not presented as cryptocurrency-grade Nakamoto security (see

Section 4).

Governance is expressed as a constrained objective that trades per-block resource expenditure (radio + cryptography) against the QoI proxy, subject to latency and ledger-coherence constraints (formalized in

Section 3.6.8). To implement this objective, the Engine applies adaptive maps

where

D denotes the PoW

target register on a 256-bit scale (dimensionless; smaller implies harder PoW) and

T denotes a dimensionless stake/quorum rigor threshold anchored by

. We instantiate

g and

f via

constrained policy approximation: a function-class search with 5-fold cross-validation on simulation traces (

Section 3.6.5), subject to stability constraints that reflect the control objective, namely (i) a non-decreasing envelope in

S (stronger validation as informational disorder increases) and (ii) a Lipschitz-bounded response in

to avoid unstable reactions under mobility. Low-order Fourier structure in

is included only when it improves out-of-sample fit, capturing empirically observed non-monotone sensitivity (e.g., clustering versus fragmentation). All coefficients, base scales

, and diagnostics are reported once for reproducibility.

Cryptographic cost is made explicitly traceable through operation counts,

so the reported cryptographic energy directly links to PoW hashing effort and/or signature/quorum operations under the selected regime. Total per-block energy combines NS-3 radio models with this analytical cryptographic term (

Section 5.7); no host-side power tools are used in reported figures or statistics.

To match the empirical tests in

Section 6, we evaluate the following hypotheses using matched-seed contrasts:

-

H1:

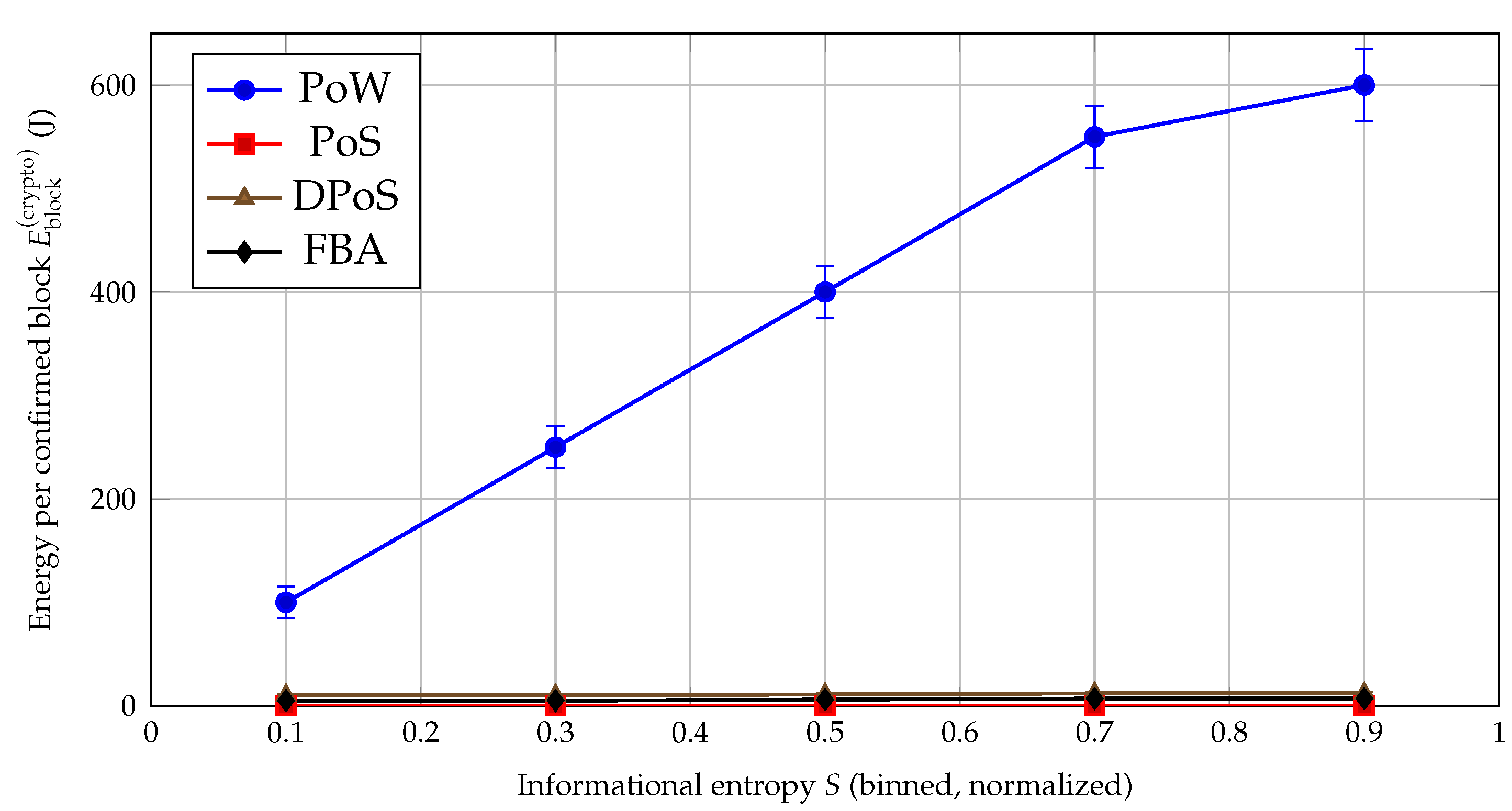

Under PoW, cryptographic energy per block increases with informational entropy S, whereas signature/quorum-based modes (PoS/DPoS/FBA) are comparatively weakly coupled to S in the latency-feasible regime.

-

H2:

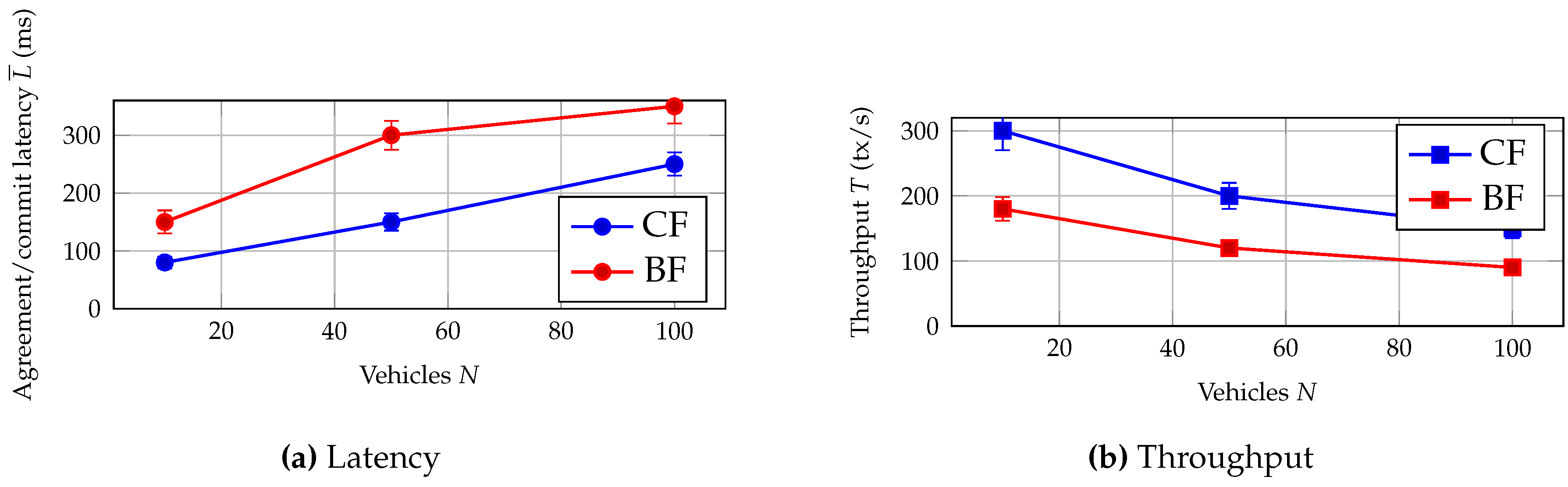

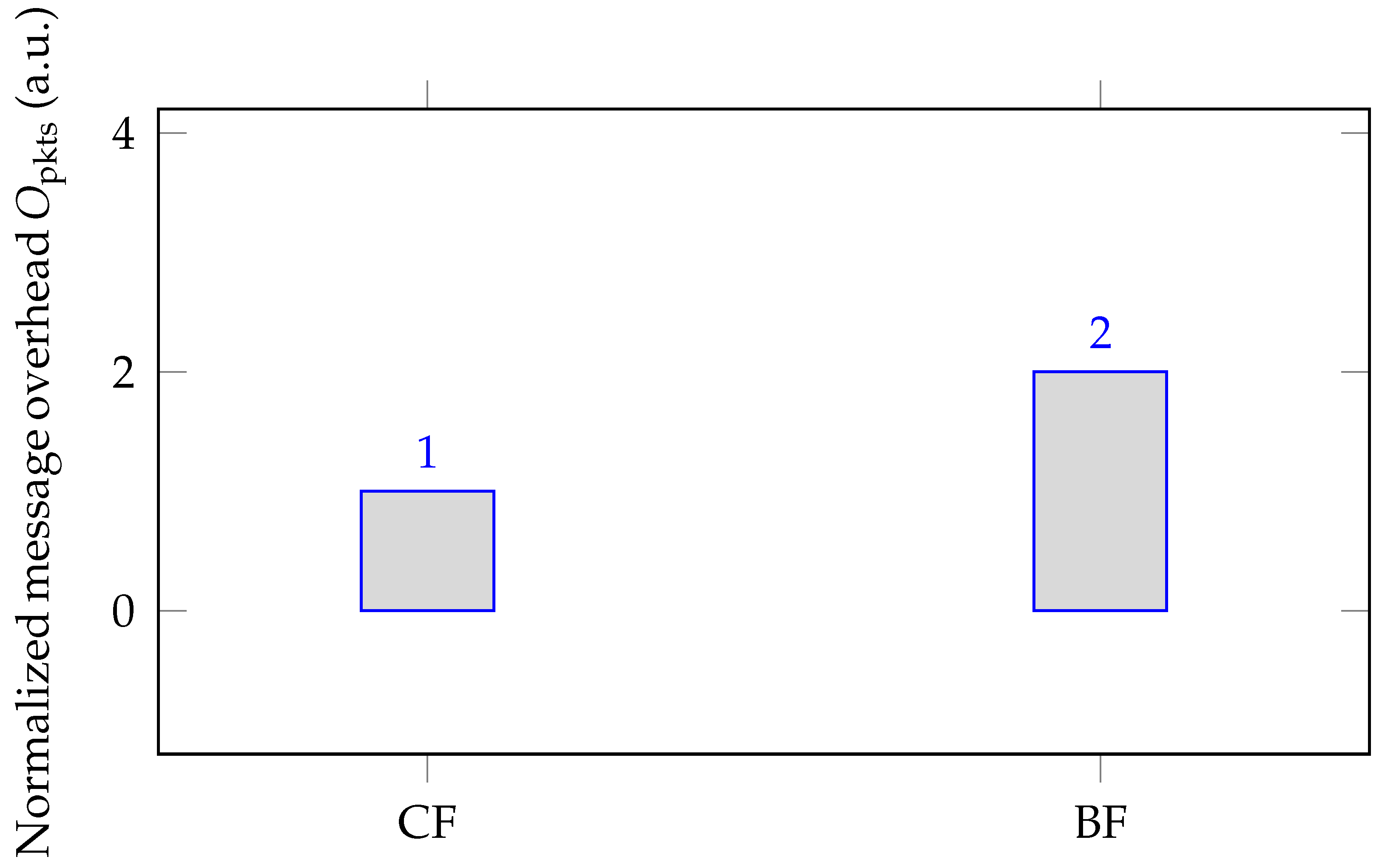

A consensus-first (CF) policy (validate immediately when ) reduces agreement latency and packet overhead and increases throughput relative to broadcast-first (BF) baselines with dwell .

-

H3:

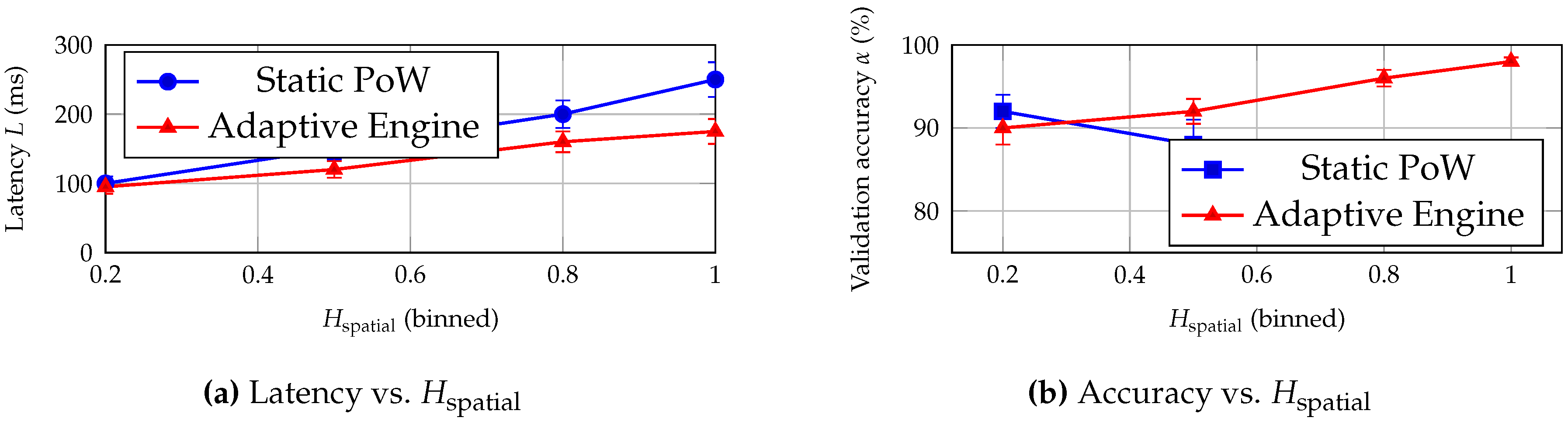

Increasing spatial disorder () degrades timeliness and validation accuracy under static settings; the adaptive Engine mitigates this degradation by tightening rigor where dispersion is highest.

-

H4:

Increasing mobility (speed v) increases orphan/fork rates and finality under static schemes; the adaptive Engine limits these increases via entropy-driven mode/parameter updates.

-

H5:

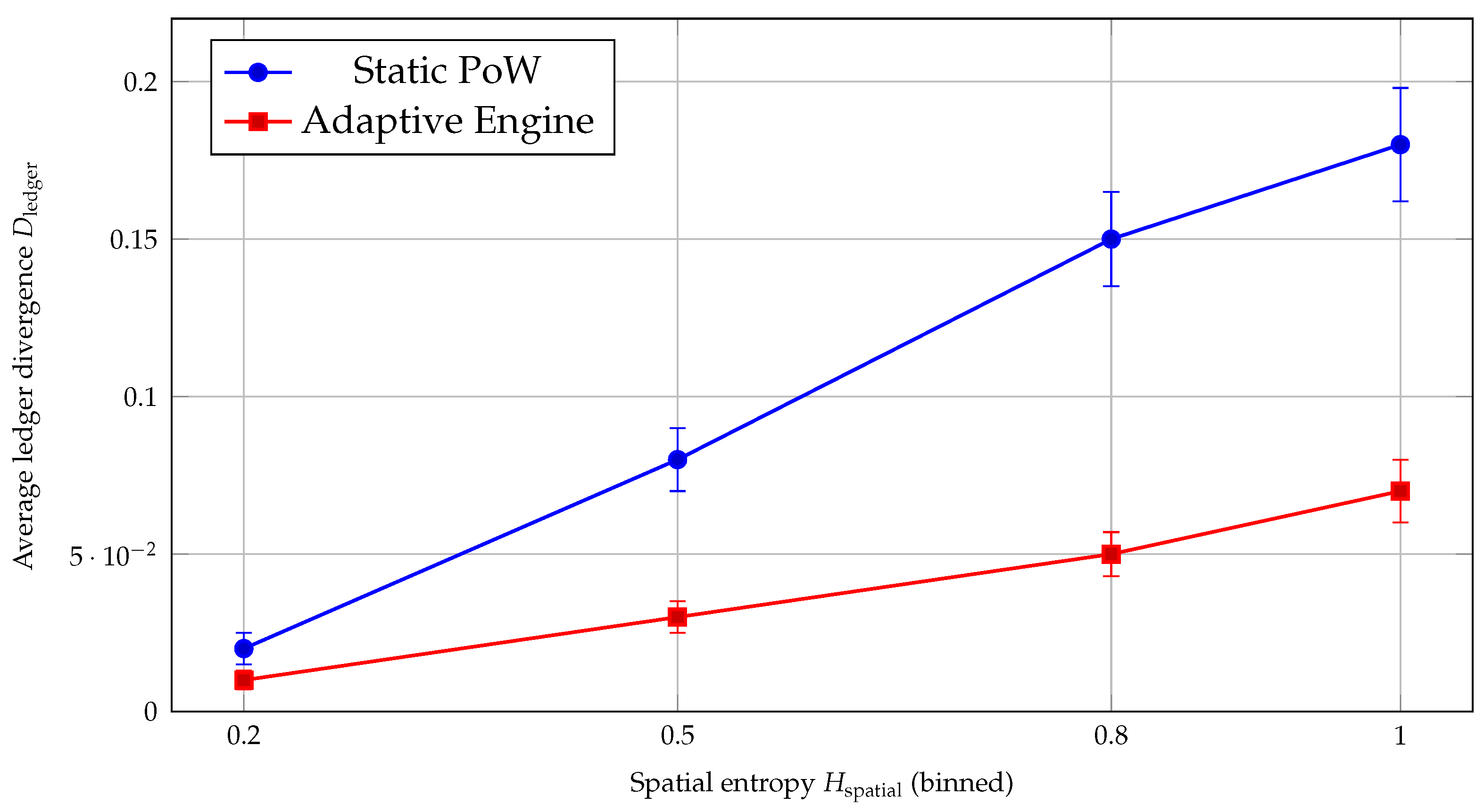

Under high spatial disorder, the adaptive Engine preserves microstate consistency by reducing ledger divergence (LCA-normalized) relative to static baselines.

We implement the Engine [

9] across urban and highway settings with 30 matched random seeds per configuration and 600 s runs (unless otherwise stated), evaluating scenarios up to

vehicles under full PHY/MAC fidelity. We include scheduled partitions (controlled

k-cut disconnections) and bounded adversarial stressors (Sybil-like pseudonyms, Byzantine proposers, and eclipse windows) as sensitivity analyses; parameters and definitions are reported where used (

Section 5 and

Section 3.6.5). Ledger coherence is quantified via an

LCA-normalized divergence metric averaged pairwise across nodes; the exact definition used for all curves and statistics is given in

Section 3.1.1 (and reiterated in

Appendix A for completeness). Reproducibility artifacts (scenario drivers, seed lists, configuration files, and plotting scripts) are released in the public repository snapshot described in

Section 5.6.

Main Contributions

Control-inspired injection–validation abstraction. We introduce an Ideal Information Cycle that provides a consistent operational interpretation of injection, validation effort, and QoI under V2X deadline constraints.

Entropy-aware, decentralized governance loop. We propose a modular VANET Engine that monitors normalized entropies and adapts consensus regimes and rigor parameters in real time.

Stability-constrained policy maps for hybrid consensus. We instantiate non-linear mappings and through cross-validated function-class search under monotonicity and Lipschitz stability constraints, avoiding manual tuning and fixed-parameter hybrids.

Prototype and evaluation under mobility and stressors. We provide an integration and an evaluation with 30 matched seeds and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, reporting latency, per-block energy, throughput, finality, and coherence dynamics under mobility, partitions, and bounded adversarial stressors.

3. Hypothesis Formulation and Methodology

This work targets secure, low-latency governance in VANETs by combining a

control-inspired Ideal Information Cycle—used strictly as an engineering analogy for resource–quality trade-offs—with a modular

VANET Engine deployed per geographic cluster. The Engine actively monitors system disorder to adapt the consensus

mode and

rigor in real time. To minimize redundancy, formal metric definitions are provided in

Section 3.1, while symbols are summarized in

Table 4.

To operationalize the control loop, we utilize two normalized Shannon entropies (mapped to ) as the primary real-time observables:

- (i)

, representing the entropy of the active transaction microstate distribution; and

- (ii)

, representing the entropy over spatial occupancy bins.

These observables quantify the disorder that the system must counteract. The resulting governance cycle, where validation rigor balances the injected disorder to maintain Quality-of-Information (QoI), is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Core Metrics, Normalization, and Boundedness

We operate on four observables. Informational and spatial disorder are captured via normalized Shannon entropies in , while QoI and ledger divergence provide operational performance and coherence signals.

Informational Entropy

Let

be the set of

distinct pending transactions at time

t and let

be the number of nodes currently holding transaction id

. Define the normalized copy distribution

and the bounded Shannon entropy

We apply Laplace smoothing

with

to avoid numerical issues; results are insensitive to

.

We use natural logarithms (nats) and normalize by

so that

by construction. For reviewer traceability, the normalization/boundedness is restated verbatim in

Appendix A.8.

Spatial Entropy

Partition the area into

M spatial bins; let

be the number of vehicles in bin

j and

. With

,

Spatial binning uses a fixed

M per scenario (Table 8), and normalization by

ensures

. For reviewer traceability, the normalization/boundedness is restated verbatim in

Appendix A.8.

QoI Proxy (Delay and Validity Tiers)

For each transaction

, we record (i) end-to-end delay

(ms) and (ii) a binary validity indicator

, where

denotes an invalid signature, stale timestamp, or failed format/consistency check. QoI is operationalized through delay/error tiers (

Section 3.6.5) and used in candidate-set formation (prioritize small

, discard

). QoI is an engineering proxy and is not interpreted as a physical quantity.

3.1.1. Ledger-Divergence Metric and Fork/Orphan Detection

Ledger Divergence .

For nodes

with heads

at time

t, let

be their lowest common ancestor and

block depth. We define the

pairwise normalized divergence

and the instantaneous average

This LCA-normalized form makes

comparable across runs with different block production rates and prevents artificial inflation early in the run when chain depth is small.

Fork/Orphan Rate

We report orphan/fork rate

O as the fraction of produced blocks that do not lie on the final main chain at simulation end (logged via

orphan_flag; see

Table 9).

3.1.2. Ledger Divergence (Microstate Coherence)

Let

denote the ordered block sequence (main-chain view) at node

u at time

t, and let

be its height. For any pair of nodes

, define

as the length of the

longest common prefix of

and

. We quantify instantaneous pairwise divergence as

and define the network-average ledger divergence by

where

is the number of active nodes at time

t.

Interpretation and Edge Cases

implies identical prefixes across all nodes (perfect coherence), while larger values indicate greater disagreement in committed history. The safeguard avoids division by zero during initialization (empty ledgers). In all figures and statistical analyses, “” refers to this LCP-normalized definition.

This is the quantity labeled

in all figures and statistical analyses and matches the definition in

Section 3.1.1.

3.2. Ledger-Divergence Metric and Fork/Orphan Detection

Purpose

We quantify

microstate consistency across nodes through an instantaneous, bounded divergence metric that captures how far node-local ledgers have drifted due to mobility, partitions, and competing commits. This complements the end-of-run orphan/fork rate by providing a time-resolved coherence signal used in

Figure 9 and related analyses.

Ledger Representation

Let denote the ordered block sequence (from genesis to the current head) at node u at time t, where is the node’s current chain height.

Longest Common Prefix and Pairwise Divergence

For two nodes

, let

be the length (in blocks) of their

longest common prefix at time

t, i.e., the maximum

ℓ such that

We define the pairwise, height-normalized divergence

where the

ensures that the normalization is in

blocks (including genesis) and avoids division-by-zero when heights are zero.

Network-Average Divergence

With

active nodes at time

t, the instantaneous ledger divergence is

A value near 0 indicates that most nodes share long common prefixes (high coherence), while larger values indicate persistent forks/partitions or delayed convergence.

Time Aggregation Used in Plots

For seed-wise summaries, we compute

as the discrete-time average over the evaluation window (after warm-up):

where

contains the sampled timestamps (default: 1 s sampling and key events, aligned with

Section 3.4). For

Figure 9, we bin each seed’s samples by

(equal-width bins) and report the mean across seeds with 95% BCa bootstrap confidence intervals.

Fork/Orphan Rate (End-of-Run)

We report orphan/fork rate

O as the fraction of produced blocks that do not lie on the

final main chain at simulation end:

where

are blocks not on the selected main chain at

. This metric is computed from the logged

orphan_flag (

Section 5.5).

Computation from Logs (Reproducibility)

We reconstruct from per-event logs by storing each committed block hash and its parent pointer for every node. The is then obtained by walking back from the heads to the first common ancestor and translating that depth to a prefix length; since blockchain histories form rooted trees, this is equivalent to the depth of the last common block plus one (including genesis). All plots and statistics use this single definition.

3.3. Nomenclature

A compact list of symbols is provided in

Table 4 to avoid re-defining variables throughout the Methods.

3.4. The VANET Engine: Entropy-Driven Governance

Sampling, smoothing, and triggers.

Every

(default 1 s), each cluster-local Engine samples

and

and applies exponential smoothing (EMA) to avoid thrashing around thresholds (

Appendix A, Algorithm A1). If either smoothed observable exceeds its threshold (

or

), the Engine increases validation rigor (e.g., selecting a signature/quorum-based mode and tightening parameters); otherwise it relaxes rigor. Thresholds and

are selected and validated as described in

Section 3.6.5.

Adaptive Mappings (Policy Approximation)

For implementability, consensus rigor is instantiated via calibrated maps:

where

D is the PoW target and

denotes the mode-specific rigor parameter (e.g., stake/quorum threshold, quorum-slice requirements). The maps are selected by cross-validated function-class search under monotonicity and stability constraints (

Section 3.6.5), consistent with the constrained optimization objective in

Section 3.6.8.

Mode Selection

Candidate sets prioritize fresher transactions (small

) and discard invalid/stale ones (

) before consensus.

|

Algorithm 1 VANET Engine (cluster-local control loop) |

- 1:

Repeat every : sample ; compute and

- 2:

if or then

- 3:

mode ← signature/quorum-based - 4:

else - 5:

mode ← PoW - 6:

end if - 7:

Build a QoI-aware candidate set; execute the selected consensus; append block - 8:

Purge invalid transactions; update local state; loop

|

3.5. Hypotheses

We test the following hypotheses using matched-seed contrasts across identical mobility/load conditions.

H1 (Energy vs. informational disorder). As S increases, PoW crypto energy per block increases steeply through the expected hash trials, while signature/quorum-based modes scale primarily with the number of signature/verification operations. An entropy-driven controller therefore reduces total energy under high S by down-selecting PoW and/or tightening rigor efficiently.

H2 (Consensus-first under high disorder). Triggering validation when (Consensus-First) reduces end-to-end agreement latency and packet overhead compared with dwell-based broadcast-first policies.

H3 (Spatial disorder effects). Increasing spatial disorder () degrades propagation and quorum stability, increasing latency and reducing accuracy/coherence in static schemes; localized adaptation mitigates these effects.

H4 (Mobility, orphans, and finality). Under higher mobility, static schemes experience increased orphaning and delayed finality, whereas entropy-adaptive mode/rigor tuning limits orphan rate O and finality F.

H5 (Ledger coherence under extreme disorder). At high S and high , the Engine maintains lower (and thus higher coherence) than non-adaptive schemes.

3.6. Detailed Methodology

3.6.1. Simulation environment and implementation

All reported experiments use

NS-3.35 [

9]. The baseline PHY/MAC stack is IEEE 802.11p/WAVE (

WaveHelper); additional C-V2X experiments, when reported, use an explicitly versioned integration layer described in

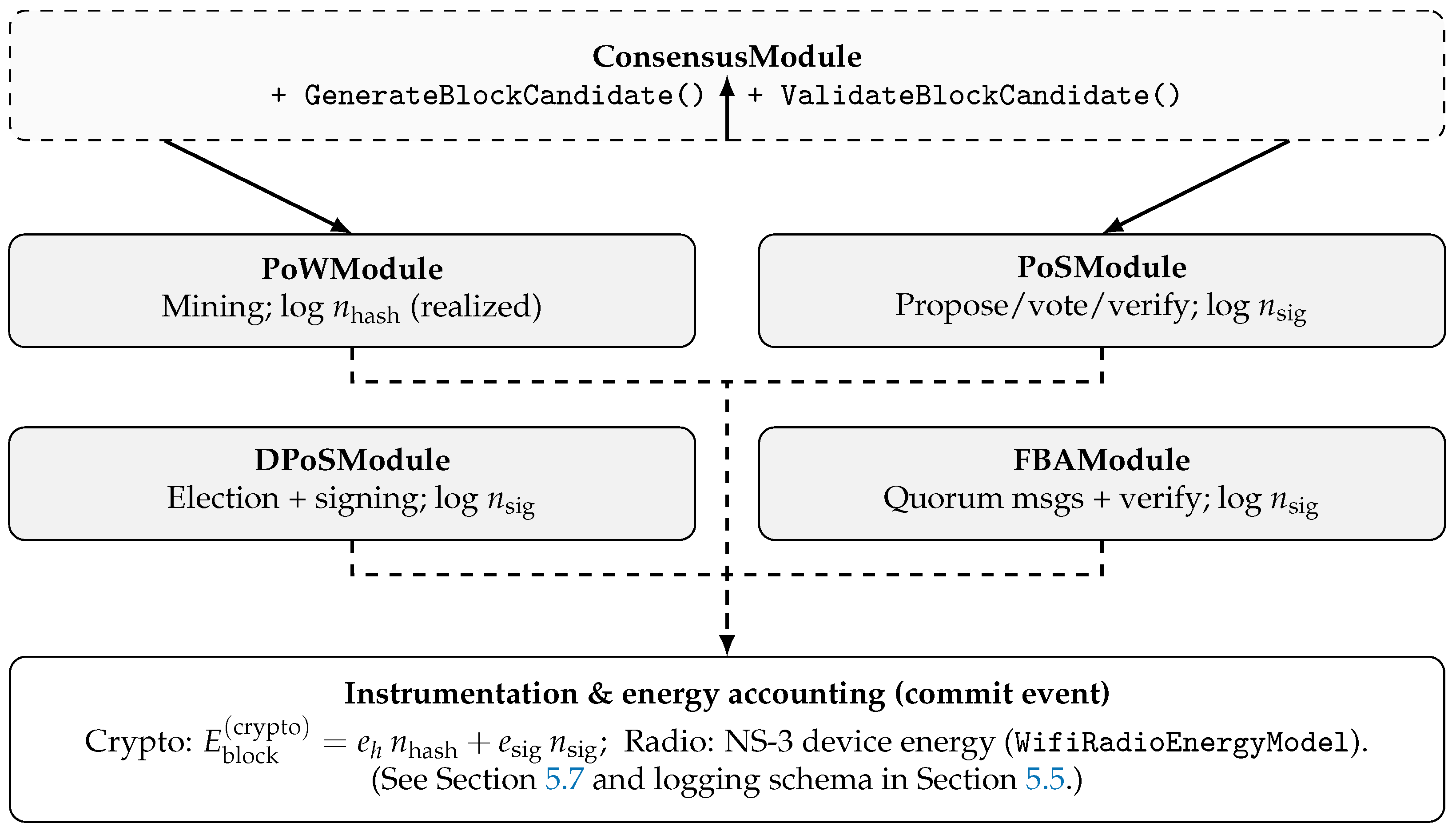

Section 5 (to ensure reproducibility across NS-3 releases). The Engine runs as an application-layer process interfacing with packet sockets and a metrics service; consensus routines are pluggable via a common

ConsensusModule interface (

Appendix A). Radio energy is modeled with

BasicEnergySource and

WifiRadioEnergyModel. Cryptographic energy is added analytically using per-hash and per-signature constants (Table 5). Metrics are sampled at 1 s and on key events (block commit, mode switch) and aggregated per run.

Forks/Orphans and Finality (Operational Definitions)

A block is marked orphaned if it is not on the final main chain at simulation end; the orphan rate O is the fraction of orphaned blocks over produced blocks (logging flag orphan_flag=1). Finality F is measured as time-to-stable-commit: for PoW, the time until the block is buried by k subsequent blocks (default k reported alongside results); for signature/quorum-based modes, the time from proposal to reaching the required quorum/commit threshold. Unless otherwise stated, metrics are computed after a 60 s warm-up (window: 60–600 s).

3.6.2. Mobility and Dynamic Conditions

We generate mobility traces with BonnMotion [

20] for: (i) an

urban grid (1 km×1 km, 50–100 vehicles, 5–15 m/s, pause 0–3 s) and (ii) a

highway (5 km, 100–200 vehicles, 15–30 m/s, pause 0–1 s). Dynamics include churn (join/leave), controlled partitions, and bursty transaction loads. Each configuration runs for 600 s with 30 matched seeds; 95% confidence intervals are computed via bootstrap (

Section 3.6.7).

3.6.3. Partition and Adversarial Stressors (Sensitivity Analysis)

We include scheduled partitions and adversarial stressors to assess sensitivity and failure modes. Parameters are fully disclosed for reproducibility. The emphasized stressor results are reported in

Section 6, while extended cases and implementation hooks are documented in

Appendix A and

Section 5.9.

3.6.4. Experimental Metrics

We record agreement latency (mean; 95% CI), per-block energy (J; radio+crypto), throughput (tx/s), orphan rate O (%), finality F (ms), and ledger divergence . Metrics are computed per run and aggregated across matched seeds.

3.6.5. Parameterization and Calibration

Energy constants and hardware mapping.

Per-hash cost

nJ/hash and per-signature cost

J/op (

Table 5) represent software cryptography on embedded OBU-class hardware. We sweep

nJ and

J in sensitivity checks; qualitative trends remain unchanged. Host-level measurements are not used in reported energy curves or statistics.

PoW Energy Accounting (Difficulty-Traceable)

Let

denote the PoW

target (smaller ⇒ harder). Under uniform hashes, the expected trials satisfy

. Define effective difficulty bits

Targets are calibrated to meet V2X-oriented latency constraints in the simulated environment; security implications of the chosen regimes are discussed in

Section 4.

Targets are calibrated for

timeliness (V2X-oriented confirmation/finality latency constraints) in the simulated NS-3 environment and are not intended to match cryptocurrency-grade PoW hardness. The security implications of these latency-feasible target regimes, under the stated threat model, are discussed in

Section 4.

Trigger Thresholds

We select and via a grid scan over on a training subset of seeds, using knee detection where latency increases nonlinearly and delivery drops below 95%. Robustness is evaluated on held-out seeds; perturbations yield variation in headline metrics.

Policy-Map Selection

To instantiate

g and

f, we perform a constrained function-class search with 5-fold cross-validation over mobility and load profiles. Candidate families include low-order polynomial, exponential/log, and spline bases; Fourier terms in

are admitted only if they improve out-of-sample fit without violating stability constraints. We enforce: (i) a non-increasing PoW target with

S (i.e., higher disorder never makes PoW easier), (ii) bounded sensitivity to

via a Lipschitz cap to prevent thrashing, and (iii) positivity/feasibility of control registers

within

and

. The final fitted coefficients, goodness-of-fit, and stability checks are reported for reproducibility in

Section 3.6.6 and

Appendix B.

3.6.6. Fitted Policy Maps and Coefficients

Final Map Forms (Reported)

We report the final closed-form maps used by the Engine. Both maps are bounded by design to avoid unstable excursions:

PoW target map .

We model the PoW target on a log-scale for numerical stability:

and set

. If Fourier terms are not selected, we set

.

Stake/quorum rigor map .

We model the rigor register as an anchored, dimensionless threshold:

followed by clamping to

.

Coefficient Reporting

Table 6 presents the fitted coefficients employed in the released artifact. The adversary profiles, capabilities, and parameter ranges for the sensitivity analysis are summarized in

Table 7. Furthermore, diagnostics such as fold-wise losses, constraint checks, and sensitivity metrics are reported in

Appendix B.

3.6.7. Statistical Procedures

All figures report means over 30 matched seeds with 95% BCa bootstrap confidence intervals (10,000 resamples). Seeds are matched across conditions (blocking by mobility/load), and Holm–Bonferroni correction is applied for multiple pairwise contrasts. For headline comparisons we additionally report paired contrasts across matched seeds (

Appendix A).

3.6.8. Theoretical Formulation and Validation Protocol

Operational Free-Governance Potential

We model governance as a

control decision taken at discrete times

k (period

), based on the observed disorder state

, where

is normalized informational entropy,

is normalized spatial entropy, and

is the operational QoI proxy (higher is better) derived from delay/error tiers. The governance action is

where

is the consensus mode,

are mode-dependent rigor registers (PoW target

on a 256-bit scale; stake/quorum threshold

in normalized stake units), and

denotes the triggering policy (Consensus-First vs. Broadcast-First dwell

).

We define a

free-governance potential that trades resource cost against QoI under timeliness and coherence pressure:

where

,

L is agreement/commit latency,

is the LCA/LCP-normalized divergence used throughout the paper,

O is orphan/fork rate, and

define the operational envelope for V2X timeliness and coherence.

Traceable energy model.

The total per-block energy decomposes into radio plus analytical crypto cost:

where

is obtained from NS-3 device energy models and

are fixed per-operation constants (

Table 5). PoW logs realized

per committed block; signature/quorum modes log

(proposal+vote/endorsement+verification operations).

Constraints and stability requirements.

Governance choices are constrained to avoid unstable or unsafe control behavior:

(C4) formalizes the design principle that higher transaction disorder should not lead to weaker validation; (C5)–(C6) ensure control-loop stability under mobility-driven fluctuations.

From Constrained Objective to Implementable Maps

The ideal controller would choose

under (C1)–(C6). Because exact online optimization is impractical in VANET control planes, we implement a compact

policy approximation:

where

are EMA-smoothed observables and

are selected by function-class search with 5-fold cross-validation under explicit enforcement of (C4)–(C6) (

Section 3.6.6 and

Appendix B).

Proof Sketch (Formal But Concise)

(i) Boundedness and well-posedness. By (C1) and clamping,

remain in compact intervals for all

k, hence the induced crypto cost in (

2) is finite and the control law is well-defined.

(ii) No chattering (control stability). Let be the decision sequence. EMA smoothing makes a contraction of the raw measurements. Under (C5), is Lipschitz in , so is bounded by a constant times . Together with hysteresis and minimum dwell (C6), the number of mode switches on any finite horizon is finite, preventing oscillations around thresholds.

(iii) Structural monotonicity. The monotone envelope (C4) ensures that increasing disorder

S cannot lead to a weaker PoW target (in

) nor a lower signature/quorum rigor

T, aligning the implemented policy with the directionality implied by (

1) when the latency/coherence penalties dominate in high-disorder windows.

(iv) Validation protocol. We validate the effect of (a) mode adaptation and (b) parameter adaptation by comparing: (1) Adaptive Engine (mode + ), (2) Static PoW (fixed D), (3) Static signature/quorum-based (fixed T), and (4) Vanilla Hybrid (switching with fixed ; formal definition provided alongside the baselines), under matched seeds and identical mobility/load.

State, Controls, and Observables

At cluster scope, the Engine observes at decision instants

t the entropy state

, where

is informational entropy and

is spatial entropy (both normalized to

as defined in

Section 2.4 and

Appendix A). The Engine selects an action

with discrete mode

and mode-specific control register

where

is a 256-bit PoW

target (smaller ⇒ harder) and

is a dimensionless stake/quorum-rigor register anchored at

.

Performance Variables and QoI Proxy

Given

, the simulator yields random outcomes per confirmed block: total energy

, confirmation latency

L, validation accuracy

(fraction of valid payloads admitted), orphan/fork indicator, and ledger divergence

(

Section 3.1.1). The QoI proxy

is computed from delay and validity tiers (

Section 3.6); we use

as a penalty for stale/invalid microstates.

Free-Governance Potential (Variational Objective)

We define an

operational free-governance potential as an expected-cost functional that trades resource expenditure against QoI under timeliness and coherence constraints:

where

and

are Lagrange-style penalty weights. The Engine’s

myopic control law is the pointwise minimizer

This makes explicit the manuscript’s “governance potential” claim: the Engine is the optimizer of (

1) under bounded control registers, with QoI and coherence entering as constraints/penalties (not as thermodynamic conjugates).

A Compact “Proof Sketch” for the Structural Constraints Used in Calibration

The calibration constraints imposed on and (monotone envelope in S and Lipschitz-bounded response in H) follow from mild monotonicity assumptions on the simulator’s risk surfaces.

Assumption A (stress monotonicity). For fixed action

a, expected stress increases with disorder:

These inequalities hold empirically in our sweeps (

Figure 7 and

Figure 9).

Assumption B (rigor reduces coherence risk). Define a scalar

rigor that increases with harder PoW targets or stronger quorum/stake requirements, e.g.,

and assume

(higher rigor reduces divergence and orphaning at the cost of higher crypto/message work).

Claim (monotone optimal rigor). Under Assumptions A–B and bounded registers, any minimizer of (

10) can be chosen such that the selected rigor is non-decreasing in

S:

Sketch. Consider two states

and

with

. If a candidate action at

uses rigor

lower than the optimal rigor at

, then by Assumption A the constraint-penalty terms in (9) cannot decrease, while the energy/QoI penalties cannot improve enough to compensate once

or

activates. Therefore, in any optimal (or Pareto-minimal) solution, the minimal rigor satisfying the active constraints is non-decreasing in

S. This directly motivates the

monotone envelope in S imposed during function-class search.

Lipschitz response in H (stability). Since

H can fluctuate rapidly under mobility, we additionally impose a bounded sensitivity

. With EMA smoothing

(

Appendix A), and a

-Lipschitz policy, the induced control variation satisfies

which prevents threshold thrashing and justifies the stability constraint in calibration.

From the Variational Policy to the Reported Maps g and f

The explicit optimizer (

10) is not computed online; instead we approximate

with parametric maps: (i) a PoW target map

and (ii) a stake/quorum rigor map

(

Section 3.6.6). The function-class search with 5-fold cross-validation selects a low-complexity basis that approximates the minimizer of (

1) over the sampled mobility/load profiles, subject to the monotonicity and Lipschitz constraints justified above. In other words, the maps are

data-fitted approximations of a clearly stated constrained objective, not claims of closed-form thermodynamic laws.

Validation Protocol (Comparators)

Validation compares four policies under identical mobility/load and matched random seeds: (i)

Adaptive (Engine) using the fitted

and mode selection; (ii)

Static PoW with fixed

D; (iii)

Static signature/quorum-based (PoS/FBA) with fixed

T or fixed slices; and (iv)

Vanilla Hybrid (fixed mode thresholds and fixed parameters, i.e., no entropy-conditioned tuning). All reported experiments use NS-3.35 with 600 s runs, 30 matched seeds, and BCa bootstrap confidence intervals (

Section 3.6.7).

Baseline: Vanilla Hybrid (VH) — Fixed-Threshold, Fixed-Parameter Hybrid

We define Vanilla Hybrid as a non-adaptive switching baseline that uses the same mode-selection rule as the Engine (i.e., the same triggers), but keeps all rigor parameters fixed. Concretely, it switches between PoW and signature/quorum-based consensus when or , yet uses constant parameters equal to their nominal mid-range values throughout the run. Thus, Vanilla Hybrid isolates the effect of mode switching alone without the adaptive tuning induced by the learned maps .

To separate the benefit of continuous entropy-conditioned tuning (policy maps ) from the simpler benefit of mode switching, we define a non-adaptive hybrid baseline, termed Vanilla Hybrid (VH). VH observes the same real-time disorder signals as the Engine, namely informational entropy and spatial entropy , but it does not use the fitted policy maps and and does not retune consensus rigor parameters online.

Formally, VH applies a fixed-threshold switching rule

where

are the same thresholds reported in Table 8 (and used by the Engine). Crucially, the

rigor parameters are fixed within each mode:

In other words, VH is a two-regime hybrid with

static and a

binary switching surface in the

plane; it does not implement the Engine’s smooth adaptation, coefficient-calibrated maps, or stability-constrained continuous control. All other shared mechanisms (transaction validation checks and logging/instrumentation) follow the common implementation described in

Section 5.4 and

Section 5.5.

5. NS-3 Implementation

We validate the proposed

entropy-driven governance loop with a modular

NS-3.35 framework [

9]. Our implementation encapsulates the cluster-local

VANET Engine (metric sampling, mode/rigor selection, and state updates) into a reusable helper (

VanetEngineHelper) and a node application (

NodeApp). Consensus is pluggable (PoW, PoS, DPoS, FBA) through a unified

ConsensusModule interface, and a structured logging pipeline records all observables required to reproduce figures and tables.

Reproducible Run Protocol

All results in

Section 6 and

Section 7 use a single execution profile:

NS-3.35,

600 s per run,

30 matched seeds per configuration, and 95% confidence intervals computed via BCa bootstrap (

Section 3.6.7). The exact simulator configuration, command-line flags, and per-event logs are versioned in the public artifact described in

Section 5.6; each run stores a

run_id and the repository

git_commit in the CSV header for traceability.

5.1. General Configuration and Simulation Parameters

We consider two mobility settings with identical communication stacks and Engine sampling policies: an urban grid (1 km×1 km) and a highway segment (5 km). Unless explicitly stated otherwise, the communication stack uses IEEE 802.11p/WAVE via WaveHelper. Experiments involving additional C-V2X/LTE-V2X integrations are reported only when explicitly flagged and are fully versioned in the artifact (to avoid ambiguity across NS-3 releases).

Safety messaging is emulated at the application layer: we generate periodic CAM-like beacons at 10 Hz (100 ms) and DENM-like event-driven alerts, which allows controlled freshness constraints without claiming a full ETSI ITS-G5 stack.

Radio energy is modeled with

BasicEnergySource and

WifiRadioEnergyModel. Cryptographic energy is added analytically using the per-operation constants in Table 10 (

Section 3.6.5). Entropy metrics follow the normalized definitions in

Section 3.1. QoI tiers are derived from delay and validity indicators (

Section 3.1).

Table 8.

NS-3 configuration (aligned with

Section 3.6).

Table 8.

NS-3 configuration (aligned with

Section 3.6).

| Parameter |

Value / Description |

| Simulator / version |

NS-3.35 (IEEE 802.11p/WAVE via WaveHelper; other stacks only if explicitly reported and versioned) |

| Area |

Urban: km; Highway: 5 km two-lane segment |

| Vehicles |

Urban: 50–100; Highway: 100–200 |

| Mobility |

BonnMotion traces [20]; churn (join/leave) |

|

M (spatial bins for ) |

Urban: (5×5 grid over 1 km×1 km); Highway: (50 longitudinal bins over 5 km). Configurable via run flags. |

|

– Informational-entropy trigger (knee-selected under V2X latency constraints) |

|

– Spatial-dispersion trigger (knee-selected to prevent divergence spikes) |

| Speeds |

Urban: 5–15 m/s; Highway: 15–30 m/s |

| Safety messaging |

CAM-like periodic beacons: 10 Hz; DENM-like alerts: event-driven |

| Engine sampling |

Every 1 s and on packet reception events |

| Consensus modes |

PoW, PoS, DPoS, FBA (pluggable modules) |

| Block size |

10 tx per block (QoI-aware candidate selection) |

| Block production trigger |

Attempt commit when 10 or per-mode timeout expires (no fixed ) |

| Energy model |

WifiRadioEnergyModel + analytical crypto term |

| Metrics logged |

S, , QoI tier, consensus latency, orphan flag, finality, , run header (seed, knobs, git_commit) |

| Duration / seeds |

600 s per run; 30 seeds; 95% CIs (BCa bootstrap) |

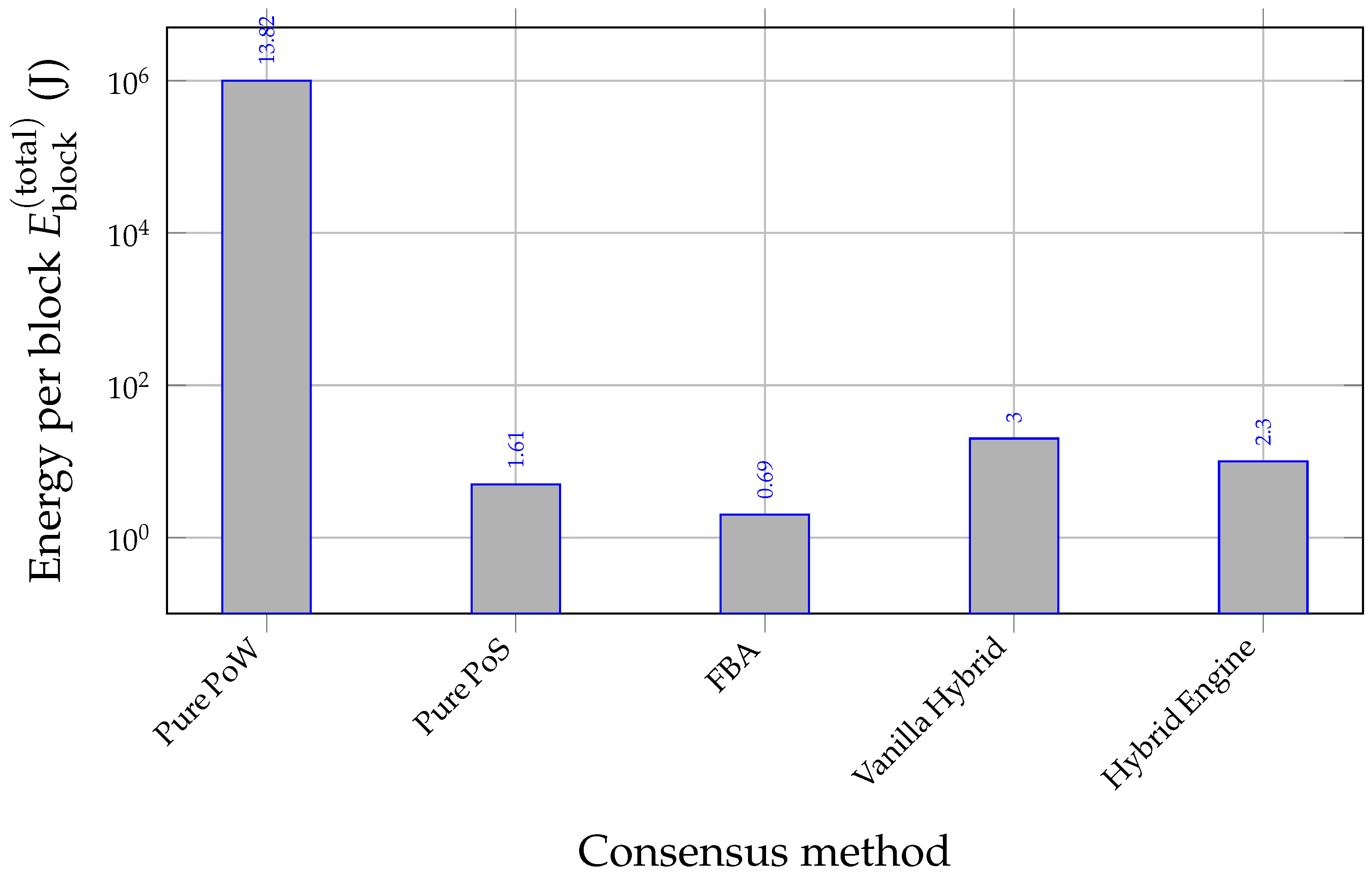

5.2. VanetEngineHelper and NodeApp Workflow

Figure 2 summarizes the helper and application pipelines. Each cluster-local Engine instance retrieves

S and

from a shared metrics service, compares them against

, and selects the active

ConsensusConfig (mode and rigor parameters). To reduce control-plane chatter, our implementation optionally disseminates the selected configuration to neighboring nodes; however, the policy is deterministic given the logged observables, and any node can compute the same decision locally.

The per-tick computational cost is over local pending transactions and spatial bins; in our settings, this overhead is negligible relative to PHY/MAC processing and consensus execution.

5.3. Partition and Adversary Plugins

We expose explicit Partition and Adversary plugins for controlled stress testing.

Partition modeling (k-cuts, claiming).

Our primary (claiming) partition mechanism is a scheduled k-cut over NetDevice links: during a partition window, selected links are programmatically disabled (Tx/Rx) to separate the network into disconnected components, and then re-enabled to measure recovery. All partition schedules (start time, duration, affected link sets, and realized component sizes) are logged per run. Alternative fading-style partitions (e.g., corridor fades) are used only as sensitivity checks and are explicitly flagged when reported.

Adversary hooks (sensitivity analyses).

Sybil identities, Byzantine proposers, eclipse windows, and corrupted transactions are injected via an AdversaryModule wrapper around NodeApp send/receive paths and consensus callbacks. Stressor parameters (e.g., Sybil ratio , Byzantine proposer rate , eclipse probability , and corruption rules) are logged and summarized in the artifact tables. These stressors are used to characterize robustness and failure modes; headline figures focus on baseline mobility/load unless a stressor is explicitly stated.

5.4. Consensus Modules

All algorithms implement a unified

ConsensusModule interface exposing

GenerateBlockCandidate() and

ValidateBlockCandidate(). For PoW, the mining routine iterates hashes until a valid nonce is found, and we log the realized number of hash attempts

for each

committed block. For signature/quorum-based protocols (PoS/DPoS/FBA), we instrument and log the full cryptographic workload—proposal signing, vote/endorsement signing, and all verification operations—aggregated as

. Radio energy is obtained directly from the NS-3 device energy models, while cryptographic energy is added as an analytical per-operation term using

(

Section 5.7).

Figure 3 summarizes the resulting class layout and call/callback relations.

5.5. Instrumentation and Logging

All results are derived from per-event logs written in a normalized CSV schema (

Table 9). Each row corresponds to a single event (transaction receipt, candidate assembly, consensus step, commit, or fork resolution), enabling seed-wise pairing and reproducible post-processing.

Table 9.

Normalized per-event CSV logging schema used for all results (deterministic under fixed seed). Each row corresponds to a key event (tx reception, block proposal, commit, mode switch). The CSV header stores

run_id and

git_commit for traceability (

Section 5.6).

Table 9.

Normalized per-event CSV logging schema used for all results (deterministic under fixed seed). Each row corresponds to a key event (tx reception, block proposal, commit, mode switch). The CSV header stores

run_id and

git_commit for traceability (

Section 5.6).

| Field |

Meaning |

| run_id |

Unique run identifier (stored in header; repeated in post-processing metadata) |

| git_commit |

Repository commit hash (stored in header) |

| seed |

NS-3 RNG seed for matched-seed pairing |

| time_s |

Simulation time (s) at event timestamp |

| node_id |

Node identifier that generated the log entry |

| cluster_id |

Geographic/connected-component cluster identifier |

| event |

Event type: {rx_tx, propose_block, commit_block, mode_switch} |

| S |

Normalized informational entropy

|

| H_spatial |

Normalized spatial entropy

|

| mode |

Active consensus mode: {PoW, PoS, DPoS, FBA} |

| D_target |

PoW target D (256-bit scale; smaller ⇒ harder) if PoW |

| T_rigor |

Stake/quorum threshold T if signature/quorum mode |

| qoi_tier |

QoI tier derived from delay/error bins |

| tx_delay_ms |

Per-transaction delay (ms) at reception/commit |

| tx_valid |

Validity flag (1 valid, 0 invalid/stale; corresponds to ) |

| n_hash |

Realized number of hashes in PoW for the committed block |

| n_sig |

Number of signature operations (proposal+votes+verify) per block |

| block_id |

Committed/proposed block identifier |

| orphan_flag |

1 if block becomes orphan at end-of-run, else 0 |

| finality_ms |

Finality time F (ms) measured per operational definition |

| lcp_len |

Longest common prefix length used to compute

|

Command-Line Reproducibility

All knobs are exposed via NS-3

CommandLine (e.g.,

–Seeds=30 –BlockSize=10 –EngineDt=1s –Sth=0.5 –Hth=0.6 –Adversary=Sybil:0.05). The artifact provides a script enumerating the full factorial design used in the paper (

Section 5.6).

5.6. Reproducibility Artifact

To enable exact replication of all reported figures and tables, we release a versioned artifact that bundles: (i) the NS-3 scenario drivers and helper/application code (VanetEngineHelper, NodeApp); (ii) the full set of configuration files (mobility/load profiles, thresholds, and default parameters); (iii) explicit seed lists per experimental condition (seeds.csv) and the script that enumerates the factorial design used in the paper; (iv) the normalized per-event CSV logging schema and parsers; and (v) the Python post-processing pipeline that generates every plot/table from raw logs.

Provenance Metadata (Run-Level Traceability)

Each simulation run writes a deterministic

run_id and the repository

git_commit hash in the CSV header, together with the full command-line string (all flags) and a normalized configuration snapshot. This provenance block ensures that every data point in

Section 6 can be traced to an immutable code revision and a unique seed/configuration tuple.

Repository Layout (High-Level)

The artifact follows a fixed directory structure: /ns3/ (scenario drivers, helpers, and modules), /configs/ (scenario and policy parameters), /seeds/ (matched seed lists), /logs/ (raw per-run CSV outputs, indexed by run_id), and /analysis/ (Pandas/Matplotlib scripts producing all figures/tables). This layout is used consistently throughout the paper and is sufficient to regenerate all results from raw logs.

Replication Protocol

To reproduce the main results, one executes the provided run script to generate logs for the declared design (600 s runs; 30 matched seeds per configuration), and then runs the plotting pipeline on the generated CSVs. The post-processing uses only the logged observables (including S, , QoI tiers, orphan flags, finality, and chain-prefix fields) and the provenance metadata stored in the CSV header, ensuring that all results are derived from recorded, seed-indexed events rather than from manual interventions.

5.7. Crypto-Energy Accounting

Cryptographic energy per block is computed as

with constants

from

Table 5. For PoW under a 256-bit target scale

D, the hit probability is

and

; we log realized

(attempts until success) and compute per-block crypto energy from the same accounting. For PoS/DPoS/FBA, we set

and count signature operations in

(proposal + votes/endorsements + verifications).

Total energy.

Total per-block energy reported in the Results is

where

is logged from NS-3 radio energy models and aligned to the block-commit event. No host-side power tools are used in reported energy curves, tables, or confidence intervals.

Table 10.

Cryptographic energy constants used in analytical accounting. Values are embedded-class software-level constants on the NS-3 energy scale and are used only for relative comparisons.

Table 10.

Cryptographic energy constants used in analytical accounting. Values are embedded-class software-level constants on the NS-3 energy scale and are used only for relative comparisons.

| Symbol |

Value |

Unit |

Meaning / usage |

|

5 |

nJ/hash |

Energy per hash (PoW). Used in . |

|

1 |

J/op |

Energy per signature/verification op (PoS/DPoS/FBA). Used in . |

|

range |

|

nJ/hash |

Sensitivity span used for robustness checks. |

|

range |

|

J/op |

Sensitivity span used for robustness checks. |

5.8. Default Parameter Rationale and Sensitivity

Table 9 summarizes the rationale for default values and the sensitivity checks used to verify robustness of qualitative trends.

5.9. Post-Processing and Visualization

After each run, CSV logs and FlowMonitor outputs are processed with Python (Pandas [

21], Matplotlib [

22]) to generate all figures and summary tables. The repository organizes raw logs, derived summaries, and plotting scripts in a fixed layout to support exact replication.

5.10. Scalability Harness (Algorithmic Profiling)

To facilitate profiling beyond full PHY/MAC fidelity, we provide an auxiliary harness with simplified PHY and FlowMonitor-only instrumentation to scale to 500+ nodes. Results from this harness are reported only as algorithmic profiling and are not used for the headline claims in this paper.

Reproducibility and measurement scope.

All reported results are produced with NS-3.35 using matched-seed configurations and a single energy accounting pipeline: NS-3 radio device models plus an analytical cryptographic term parameterized by computed from operation counts. No host-side power profilers are mixed with simulated energy values; versioning, seeds, and configuration manifests are provided in the artifact repository.

7. Discussion

The entropy-driven

VANET Engine supports

–

and yields consistent improvements in energy, latency, throughput, validation accuracy, and ledger coherence under realistic urban dynamics. We interpret outcomes through the Ideal Information Cycle (

Figure 1), relate them to the challenge–mitigation matrix (

Table 3), and clarify normalization, units, parameter provenance, and instrumentation. To avoid redundancy, we do not re-state metric definitions already introduced in

Section 3.1 and the detailed protocol in

Section 3.6.

Spatial Dispersion as a Governance Signal

Beyond the hypothesis tests,

Figure 7 demonstrates that

is a strong predictor of consensus stress: dispersion increases latency and degrades validation accuracy under static PoW. The adaptive Engine mitigates this trend by tightening validation and/or switching away from expensive regimes when dispersion is greatest, thereby improving both timeliness and correctness during fragmented connectivity windows.

Normalization, Units, and Terminology

Normalized Shannon entropies. S and

are Shannon entropies computed over normalized distributions (

Section 3.1) and then scaled to

. For readability, plots and text reuse

S and

to denote the normalized quantities.

Observables vs. treatments (binning interpretation). In the Results, and are observed time-varying signals; reported curves represent conditional aggregation (binning) over realized entropy levels rather than externally set treatments.

Ledger divergence. All references to

use the same

LCP-normalized longest-common-prefix definition in

Section 3.1; binning/aggregation and confidence intervals follow that definition consistently.

Consensus outputs. is a PoW target on a 256-bit scale (dimensionless; smaller ⇒ harder). denotes a mode-specific rigor parameter (e.g., quorum/stake threshold, committee size), with coefficients inheriting simulation control scales rather than physical units.

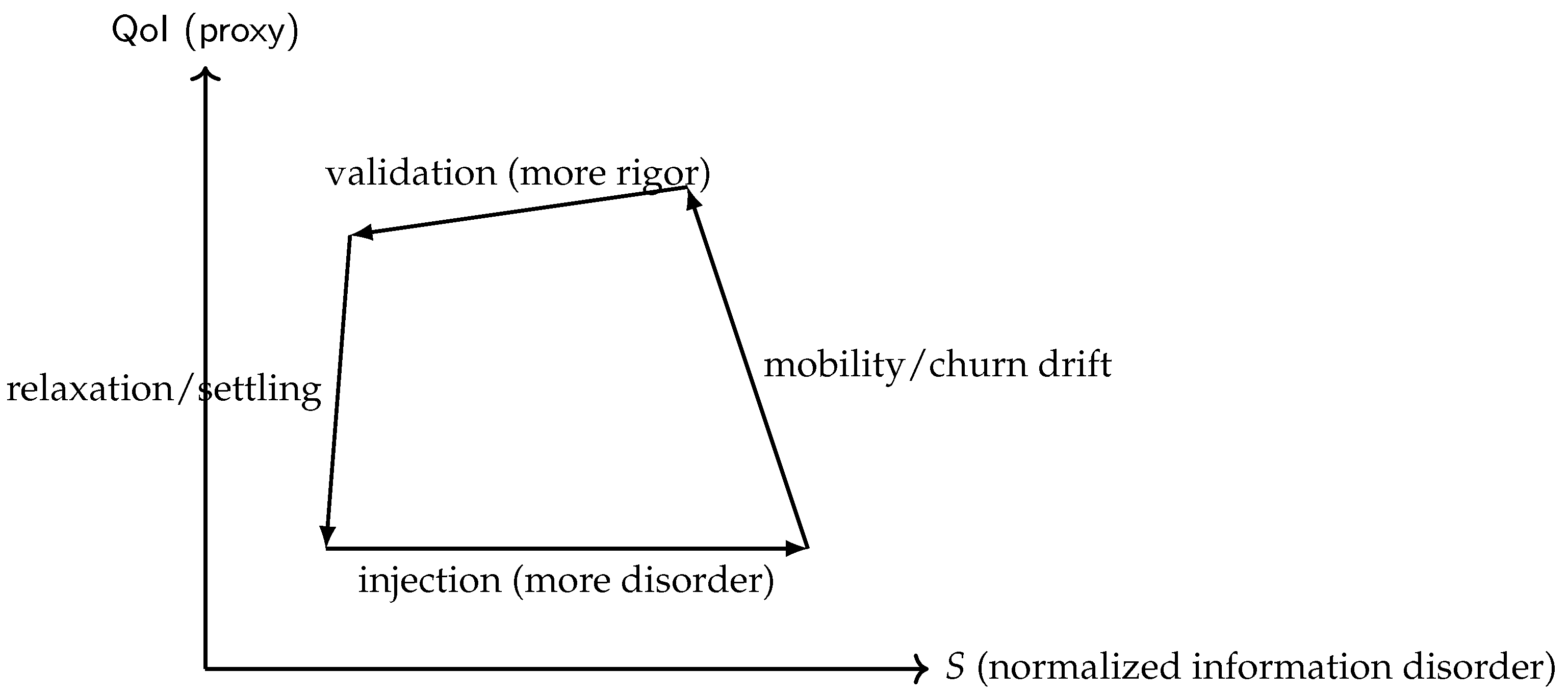

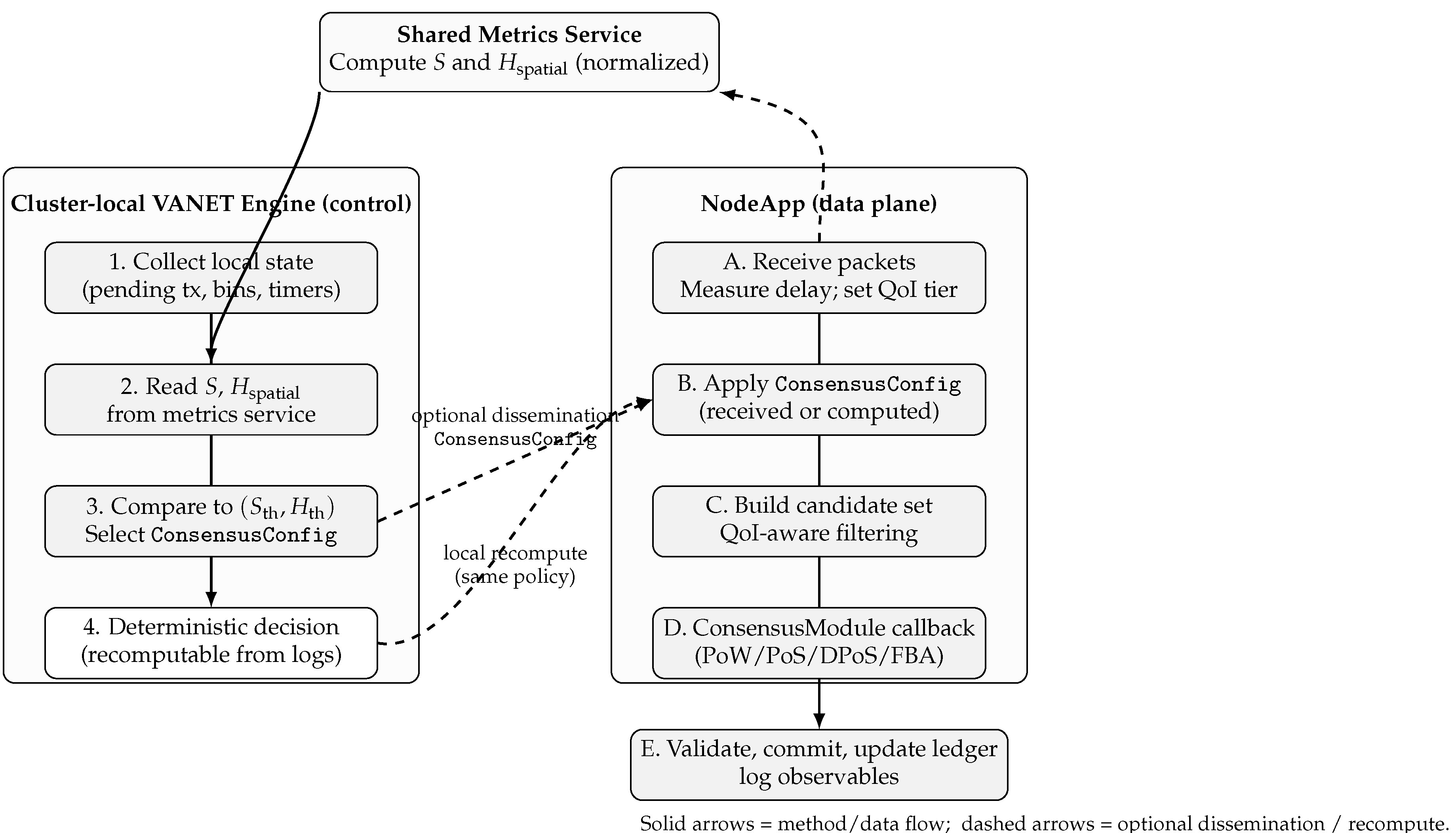

Energy reporting across figures. Figure 4 reports crypto energy only (

) to isolate scaling with

S. The expanded comparison (

Figure 11 and companions) reports

total per-block energy (radio+crypto) in the NS-3 energy-source scale; absolute magnitudes are therefore not directly comparable across those panels, but trends are.

Calibration Anchors, Magnitude Sanity Checks, and Sensitivity

Magnitude sanity check (PoW crypto energy). The

J high-entropy PoW point in

Figure 4 follows directly from

with

nJ/hash (

Table 5) and

aggregate attempts across participants for a confirmed block. Via

, this implies targets far easier than Bitcoin, but consistent with deadline-constrained V2X consensus and with the calibrated map

.

Sensitivity. Reported trends persist under

perturbations of calibrated parameters and across additional traces (logs described in

Section 5.9), indicating that improvements are not brittle to small calibration changes.

Instrumentation Choices and What We Do (and Do Not) Measure

Statistical Validity, Fork Definition, and Stressors

Power and uncertainty. We use

seeds per condition. Bootstrap CIs are reported throughout; seed-wise paired contrasts (Holm–Bonferroni adjusted) support headline comparisons as summarized in

Section 6.10.

Fork metric (no under-claiming). Orphan/fork rate

O is the fraction of blocks not on the final main chain (

Section 6.9). In the urban

case under high mobility, medians remain on the order of 8–

for the Engine: the Engine reduces but does not eliminate forks under stress.

Adversaries and partitions. Stress tests (Sybil, Byzantine proposers, eclipse windows, scheduled

k-cuts) in

Section 6.7 show reduced recovery times and capped divergence spikes under the Engine relative to static baselines; fully adaptive adversaries remain future work.

Version Harmonization and Run Protocol

All reported experiments use

NS-3.35 with

600 s per run and

30 matched seeds per configuration (

Table 8). Shorter pilot sweeps, if any, are not mixed into reported statistics.

Interpreting the Expanded Comparison (Censoring and Practicality)

In the expanded comparative evaluation (

Section 6.8), Pure PoW may fail to confirm within the 600 s simulation horizon in the densest/high-disorder regimes. Reported PoW confirmation latency is therefore right-censored at 600 000 ms when applicable, which should be read as “≥ 600 s” rather than as an exact mean. Under these operating conditions, the Engine’s advantage reflects practical deadline satisfaction rather than marginal improvement under unconstrained convergence.

Implications for the Challenge–Mitigation Map (Table 3)

Mobility/topology churn. Entropy-aware switching lowers orphaning and finality (

Figure 8), operationalizing mitigation under churn.

Congestion and bandwidth fluctuation. CF reduces message overhead (

Figure 6) and increases throughput (

Figure 5), limiting injection-phase amplification.

Integrity/coherence under disorder. Tightening rigor in high-

windows reduces divergence (

Figure 9) and improves validation outcomes (

Table 11).

OBU constraints. Favoring PoS/FBA over PoW in high-

S intervals reduces cryptographic energy by orders of magnitude (

Figure 4) while preserving correctness/coherence.

Limitations and Threats to Validity

This study is simulation-based (NS-3) and omits several physical and deployment effects, including hardware accelerators, GNSS error, clock skew, heterogeneous firmware behaviors, and cross-layer scheduling effects. Adversaries are stylized (sensitivity analyses) and not fully adaptive beyond disorder amplification. Mixed deployments (802.11p with LTE-V2X) may shift the optimal thresholds , but do not negate the central finding: an entropy-conditioned rigor policy improves timeliness and coherence under churn.

Operational Guidance

For dense corridors, trigger CF when to avoid dwell-induced rebroadcast storms. Prefer PoS/FBA (or an adaptive hybrid) in high-S/high- windows to meet V2X-style deadlines and conserve energy. Deploy Engines per cluster/segment in partition-prone areas to preserve convergence and accelerate recovery, while using QoI filtering to reduce invalid admission and wasted work.

Editorial and Reproducibility Adjustments

Definitions centralized. Entropy normalization and

are stated once and cross-referenced (

Section 3.1).

Protocol unified. NS-3.35 is the reference; 600 s/30-seed runs are standard unless explicitly stated (

Table 8).

Energy accounting clarified. Reported energies are simulation-native (radio+analytical crypto) with no host-measurement mixing (

Section 5.7).

Traceability. Logged schemas and scripts ensure that all plots and statistics can be reproduced from per-run artifacts (

Section 5.5–

Section 5.9).

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Several research directions follow naturally from the present results and from the limits of full-fidelity VANET simulation. First, scaling beyond the range evaluated here will require hierarchical governance: cluster-local Engines can be composed into multi-tier control, where intra-cluster consensus remains latency-feasible while inter-cluster reconciliation is performed less frequently and with stronger anchoring to preserve coherence under large-area fragmentation. Such designs can also incorporate sharded validation and selective state dissemination to reduce control-plane load in dense corridors. Second, the current maps and can be extended to account for heterogeneous energy states and device constraints. In realistic fleets, OBUs exhibit varying battery levels, compute capabilities, and duty-cycling policies. Incorporating per-node energy state and harvested-power profiles into the rigor policy would enable explicit energy-aware governance, e.g., shifting expensive validation toward nodes or roadside infrastructure with renewable power while maintaining bounded latency for safety-critical updates. Third, predictive control offers a principled upgrade path. Instead of reacting to spikes in S or , short-horizon forecasting of mobility and topology could pre-emptively adjust validation strength before fragmentation occurs. This can be combined with learning-based QoI filters that detect anomalies or malicious patterns prior to consensus, provided that false-positive rates are bounded to avoid suppressing legitimate safety messages. Finally, security-oriented extensions merit dedicated study under stronger adversarial models. Future work should integrate Sybil-resistant membership services for validator/quorum selection, rotating quorum slices for eclipse resilience, and explicit checkpointing/anchoring strategies to bound reorganization depth after partitions. Evaluations should include adaptive attackers that attempt strategic entropy manipulation and long-lived eclipses, allowing formalization of security guarantees under bounded Byzantine fractions and under mode transitions. City-scale studies with mixed 802.11p/C-V2X stacks and larger N via hierarchical simulation would then quantify control-loop stability and operational trade-offs under heavy bursts and heterogeneous radios.

8.1. Key Conclusions

H1 — Consensus as an energy cycle.

As informational disorder rises, PoW becomes increasingly expensive: in the crypto-only panel (

Figure 4), PoW energy per block grows sharply with

S, reaching

J at high entropy, whereas PoS remains near-constant in the sub-Joule regime (with DPoS/FBA in single-digit Joules). This confirms the central

entropy–work coupling predicted by the Ideal Information Cycle (

Figure 1) and motivates avoiding PoW in high-

S windows. The magnitude is consistent with

and

under the V2X-feasible targets imposed by

(

Section 3.6.5), i.e., difficulties far below cryptocurrency-scale PoW but aligned with deadline constraints.

H2 — Consensus-first triggering improves timeliness and reduces overhead.

In the baseline urban case (

,

),

Consensus-First (CF) reduces agreement/commit latency and increases throughput relative to

Broadcast-First (BF), while reducing packet overhead (

Figure 5Figure 6). Concretely, latency drops from

ms to

ms (95% CI: 135–165 ms), throughput rises from

tx/s to

tx/s (95% CI: 185–215 tx/s), and normalized overhead is roughly halved. This validates H

2 and supports a practical control rule: when

S crosses

, shorten the injection leg by validating immediately rather than accumulating broadcast dwell.

H3 — QoI filtering reduces wasted work.

QoI-aware candidate construction (prioritizing fresher transactions with small

and excluding invalid/stale payloads with

) prevents consensus effort from being spent on low-quality microstates. In the QoI ablation (

Table 11), filtering reduces invalid admissions and invalid-block share, lowers the fraction of cryptographic energy wasted on orphaned/invalid outcomes, and improves confirmation latency under identical network conditions. The directionality is stable across matched seeds and aligns with the Engine’s design goal:

compress disorder while preserving QoI.

H4 — Dynamic tuning improves efficiency and stability.

Adaptive maps

and

yield better operating points than static PoW/PoS and non-adaptive hybrids. In the expanded comparison (

Section 6.8), the proposed

Hybrid Engine achieves the lowest transaction confirmation latency with competitive total per-block energy while sustaining higher throughput than static baselines and a vanilla hybrid (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). These results validate H

4: tuning rigor as a function of

improves throughput-per-energy and reduces coherence loss relative to static parameters.

H5 — Convergence and coherence under high entropy.

Under dispersion and transient disconnections, microstate alignment degrades for static schemes. The Engine maintains markedly lower ledger divergence in high-

regimes (

Figure 9) and recovers faster after partitions and eclipse windows (

Section 6.7), indicating improved convergence under stress. Operationally, this confirms H

5: conditioning rigor on observed disorder yields more coherent ledgers even when connectivity becomes intermittent.

Additional empirical observation: spatial dispersion is a reliable stress signal.

Independent of hypothesis labels, spatial entropy is a strong predictor of governance stress. As

, static PoW exhibits increasing latency and decreasing validation accuracy (

Figure 7). The Engine mitigates this degradation by tightening validation and/or switching away from regimes that amplify forks, thereby preserving both timeliness and correctness in dispersed topology windows.

8.2. Limitations

Scale. The main study evaluates up to

vehicles under full PHY/MAC fidelity; we do not extrapolate beyond this range. An auxiliary profiling harness (

Section 5.10) supports larger-

N algorithmic stress tests but is non-claiming.

Energy model abstraction. Per-hash (

) and per-signature (

) costs (

Table 5) are embedded-class software constants used in an analytical crypto term paired with NS-3 radio energy. Claims focus on

relative scaling with

S and

; absolute magnitudes will shift with accelerators and platform heterogeneity.

PHY/MAC fidelity and channel effects. NS-3’s IEEE 802.11p/C-V2X abstractions omit some physical nonlinearities (e.g., rich multipath/interference coupling in dense urban canyons). Field calibration is needed for deployment-grade parameterization.

Adversary scope. Stressors are stylized sensitivity analyses; fully adaptive collusion (strategic Sybil/eclipsing with learning) is left for future work. Partition events are scheduled

k-cuts in simulation (

Section 5.3); real cities may exhibit more complex, correlated failures.

Right-censoring under impractical regimes. In high-disorder configurations, Pure PoW may fail to confirm within the 600 s horizon; in such cases the plotted “600000 ms” should be read as “≥600 s” rather than an exact mean, reinforcing the practicality motivation for adaptive hybrid governance.

Protocol uniformity. All reported results use NS-3.35, 600 s duration, and 30 matched seeds unless explicitly stated.

8.3. Future Directions

Future work should prioritize scaling the entropy-governed control loop beyond the full-PHY/MAC regime studied here by introducing hierarchical Engines that operate at multiple tiers (intra-cluster and inter-cluster). A natural extension is to assign local Engines to connected components while an upper-tier coordinator (e.g., RSU-backed or infrastructure-assisted) mediates cross-cluster anchoring and conflict resolution, thereby preserving low finality while reducing the coordination burden in dense grids and long corridors.

A second direction is to incorporate heterogeneous energy profiles into the policy maps. In real fleets, OBUs differ in battery state, compute capability, and duty-cycling constraints; thus, and can be augmented with per-node energy state (battery/harvesting) and platform-aware cost coefficients to avoid systematically overloading constrained devices. This would convert the current cluster-level rigor policy into a device-aware governance mechanism that explicitly trades timeliness against the remaining energy budget and the expected contact time within connectivity windows.

Third, deployments can benefit from shifting expensive work to renewable-powered infrastructure through a proof of useful work (PoUW) concept at RSUs. Rather than spending scarce vehicular energy on repeated hashing or excessive endorsements, RSUs could carry out verifiable edge tasks (e.g., aggregation, model updates, or safety analytics) whose outputs are attestable and can serve as a commitment primitive. This would keep OBUs predominantly in low-cost regimes while preserving a stronger operational security envelope than latency-feasible PoW alone.

Fourth, the Engine can be made predictive by integrating mobility and topology forecasting to adjust rigor preemptively before entropy spikes occur. Short-horizon predictors (e.g., based on vehicle density, projected dispersion, and link-quality trends) could modulate or directly regularize so that the control loop reacts before contention and fragmentation inflate orphaning and divergence. This is particularly relevant in urban canyons and merge-lane bottlenecks where entropy rises rapidly and reactive switching may be late.

Fifth, we propose strengthening the QoI layer through bounded-risk learning for pre-consensus filtering. Lightweight anomaly detection or classifier-assisted admission (trained on delay/error tiers and message consistency features) could reduce malicious or low-QoI payloads with controlled false-positive rates. Importantly, such filters should be evaluated under distribution shift and coupled to the Engine with conservative risk bounds so that gains in timeliness do not come at the expense of excluding valid safety-critical messages.

Sixth, large fleets require succinct microstate telemetry to monitor coherence without inflating overhead. Merkle proofs, sketches, or Bloom-filter summaries can approximate divergence and membership state across clusters at low bandwidth cost, enabling -like monitoring and re-convergence triggers without per-event detailed exchanges. This direction complements hierarchical Engines by providing scalable observability.

Finally, future evaluations should expand the adversarial and environmental envelope by analyzing adversary-resilient adaptation under more adaptive attackers and by validating at city scale. This includes combining Sybil-resistant staking (or credential governance), rotating quorum slices, and eclipse detection, as well as studying control-loop stability under heavy burst traffic and heterogeneous radios in mixed C-V2X/802.11p settings. A city-scale campaign (e.g., ) should explicitly separate (i) non-claiming algorithmic stress tests from (ii) claiming regimes with documented fidelity, ensuring that scalability conclusions are supported by appropriately instrumented experiments and by transparent reporting of which effects are simulated at full PHY/MAC versus abstracted.

8.4. Artifacts and Reproducibility

All figures in

Section 6 are generated from per-event CSV logs via the version-controlled Python pipeline described in

Section 5.9. Random seeds (30 per configuration), calibrated parameters (

Section 3.6.5), fork/orphan definitions, and partition schedules are documented in the repository layout.

Energy accounting uses only NS-3’s radio models plus the analytical crypto term (); no host-side power tools are mixed with simulated per-node energy. The

formula used in plots and statistics is the

LCP-normalized definition in

Section 3.1.

8.5. Concluding Remarks and Conceptual Scope

Our thermodynamic language is

operational rather than a claim of physical equivalence:

S and

are measurable disorder observables used to price consensus rigor; the Engine injects

consensus work to compress disorder only when needed. The adaptive maps

g and

f act on dimensionless target/threshold registers anchored by calibration (

Section 3.6.5) and are justified by shape constraints and data-driven selection. Within this scope, governing consensus via entropy observables yields an energy-aware, latency-conscious, and resilient ledger for safety-critical V2X. More broadly, the “information engine” principle may extend to other resource-constrained distributed ledgers (IoT, supply chains, edge systems): dynamically pricing rigor against measured disorder provides a pragmatic blueprint for sustainable and adaptive consensus.