Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Organization of the Document

- Section II: Fundamental Principles and State of the Art. This section introduces blockchain technology and Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs), providing a comprehensive overview of the current research landscape in these domains.

- Section III: Hypothesis Formulation and Methodology. Here, the research hypotheses are clearly defined and the methodology for their evaluation is described in detail, including the simulation of VANETs using NS-3 and the integration of blockchain technology.

- Section IV: Evaluation and Discussion of Results. This section presents the outcomes from the simulations and analyses, followed by a critical discussion of the results.

- Section V: Conclusions and Future Work. The final section summarizes the main findings of the study and outlines potential avenues for future research, with a focus on further enhancing the governance and resilience of vehicular ad-hoc networks through blockchain-based solutions.

2. Fundamental Principles and State of the Art

2.1. Exploration of Blockchain Technology

2.2. Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs): Highly Dynamic and Decentralized Systems

2.3. Current State

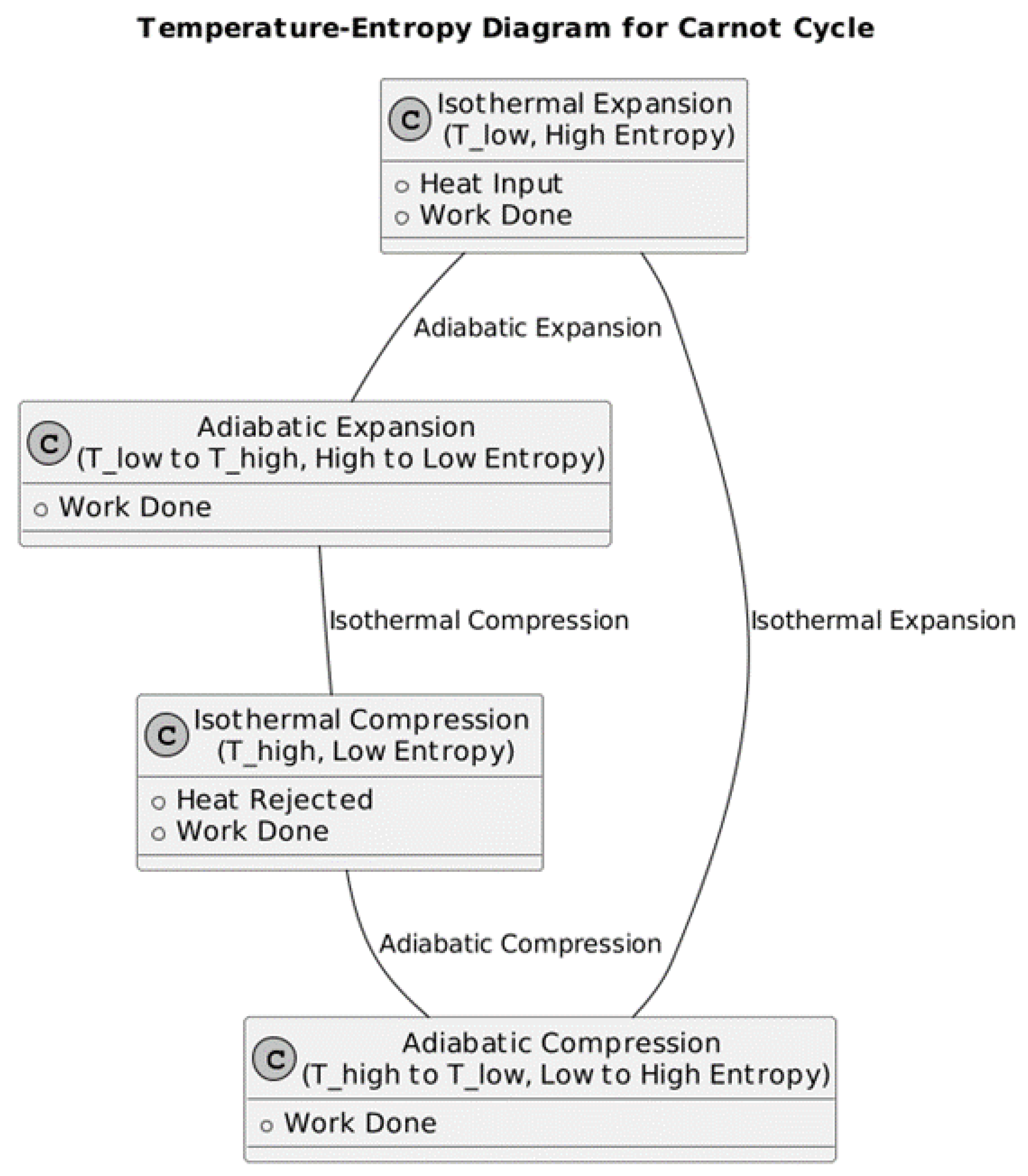

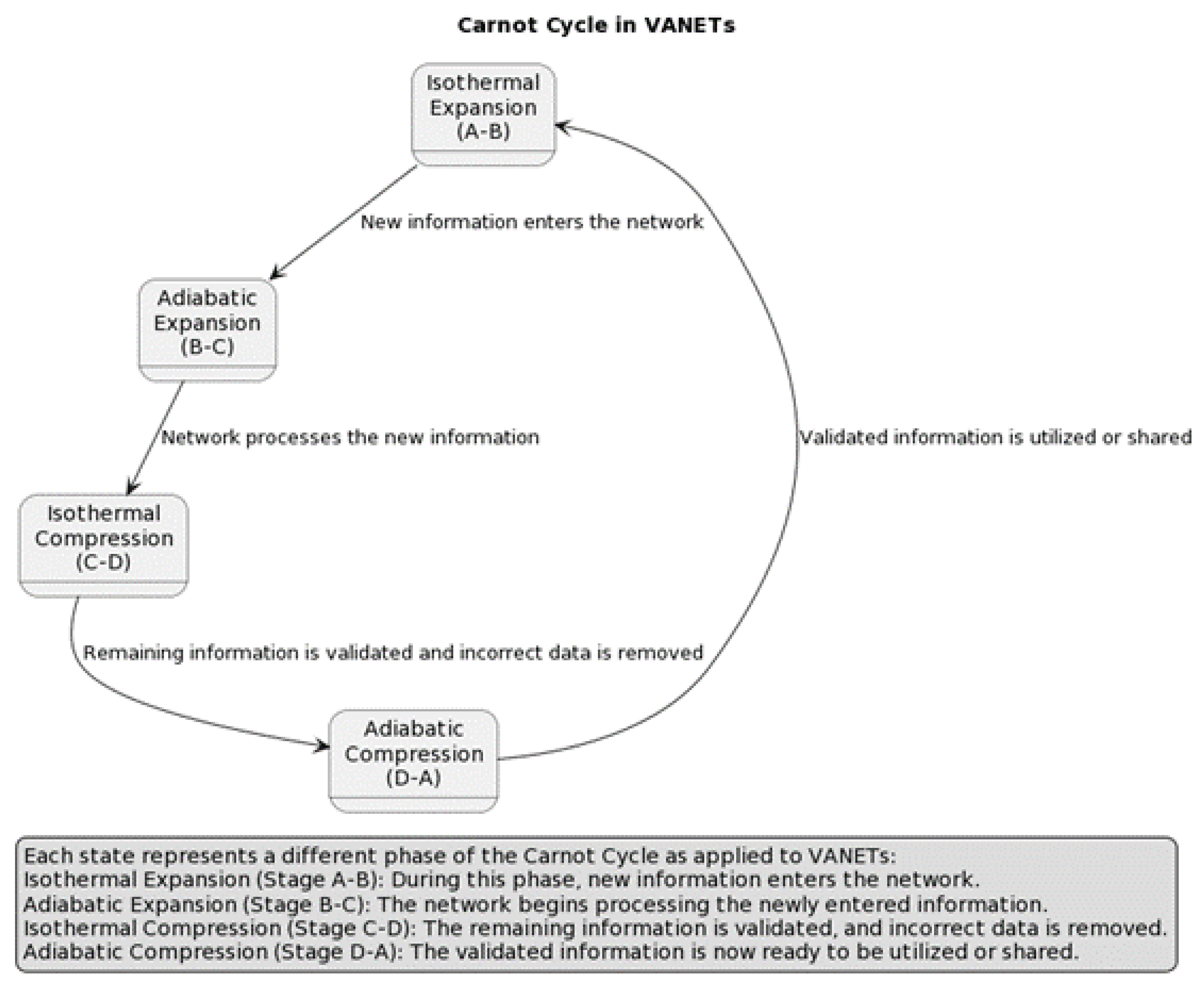

2.4. Application of the Carnot Cycle to VANETs

- 1.

- Isothermal Expansion (Stage A-B): During this phase, new information enters the network. Despite the simultaneous influx of large volumes of data, the overall quality remains relatively constant (i.e., isothermal conditions). However, entropy increases as the system becomes more disordered due to the introduction of unverified or heterogeneous information.

- 2.

- Adiabatic Expansion (Stage B-C): In this stage, the network processes the incoming data. As low-quality or incorrect information is identified and discarded, there is a slight decrease in overall information quality. Concurrently, the system ’cools down’ and entropy decreases as order is gradually restored.

- 3.

- Isothermal Compression (Stage C-D): Here, the remaining information is rigorously validated while redundant or erroneous data is removed. The quality of information remains steady since high-quality data is preserved, and entropy is further reduced as the system achieves a higher degree of order.

- 4.

- Adiabatic Compression (Stage D-A): Finally, the validated information is ready for use in decision-making or for dissemination to other nodes. During this phase, the quality of information improves, and entropy continues to decrease, returning the network to a state ready to process new incoming data and thus completing the cycle.

3. Hypothesis Formulation and Methodology

- 1.

- Incorporating blockchain technology into VANETs can significantly enhance their security and privacy [25].

- 2.

- A blockchain model that integrates thermodynamic principles can offer a more accurate and efficient representation of decentralized governance in VANETs. (This hypothesis is novel and builds upon the theoretical framework established in [22].)

- 3.

- The use of an entropy-based information cycle can contribute to optimizing VANET performance [2].

3.1. Incorporating Blockchain Technology into VANETs to Enhance Security and Privacy

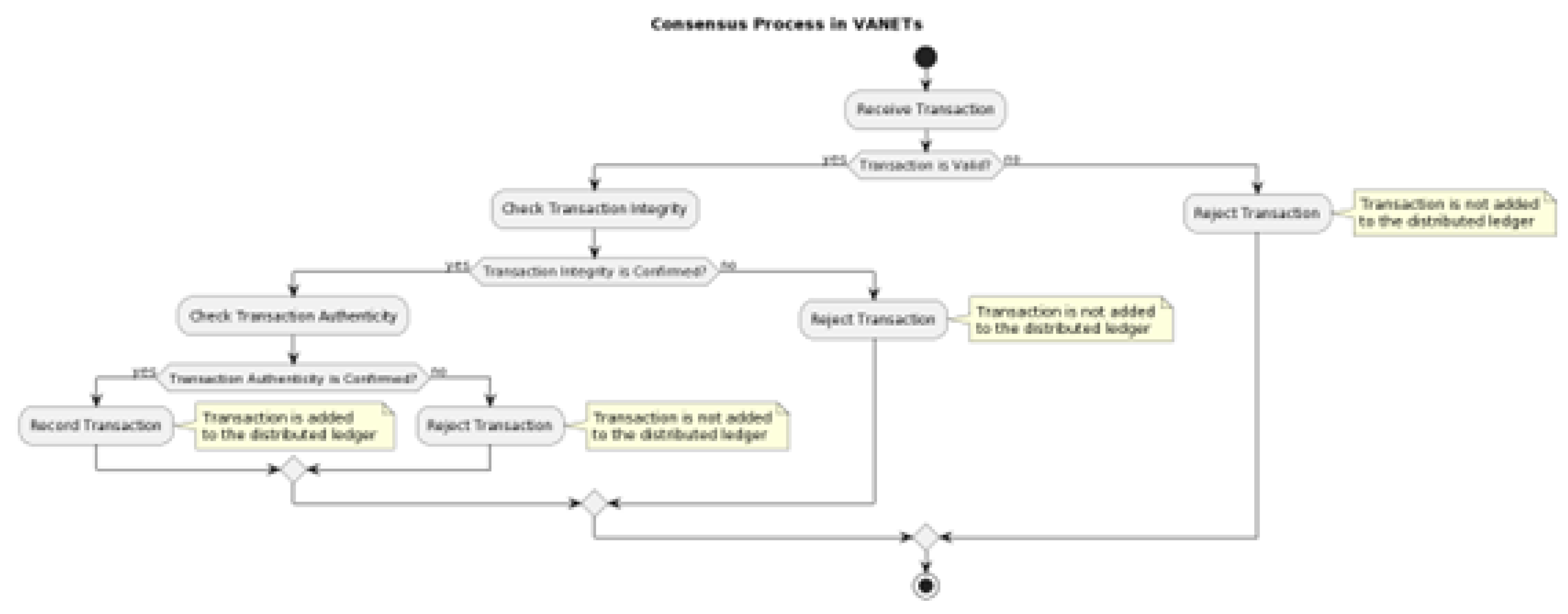

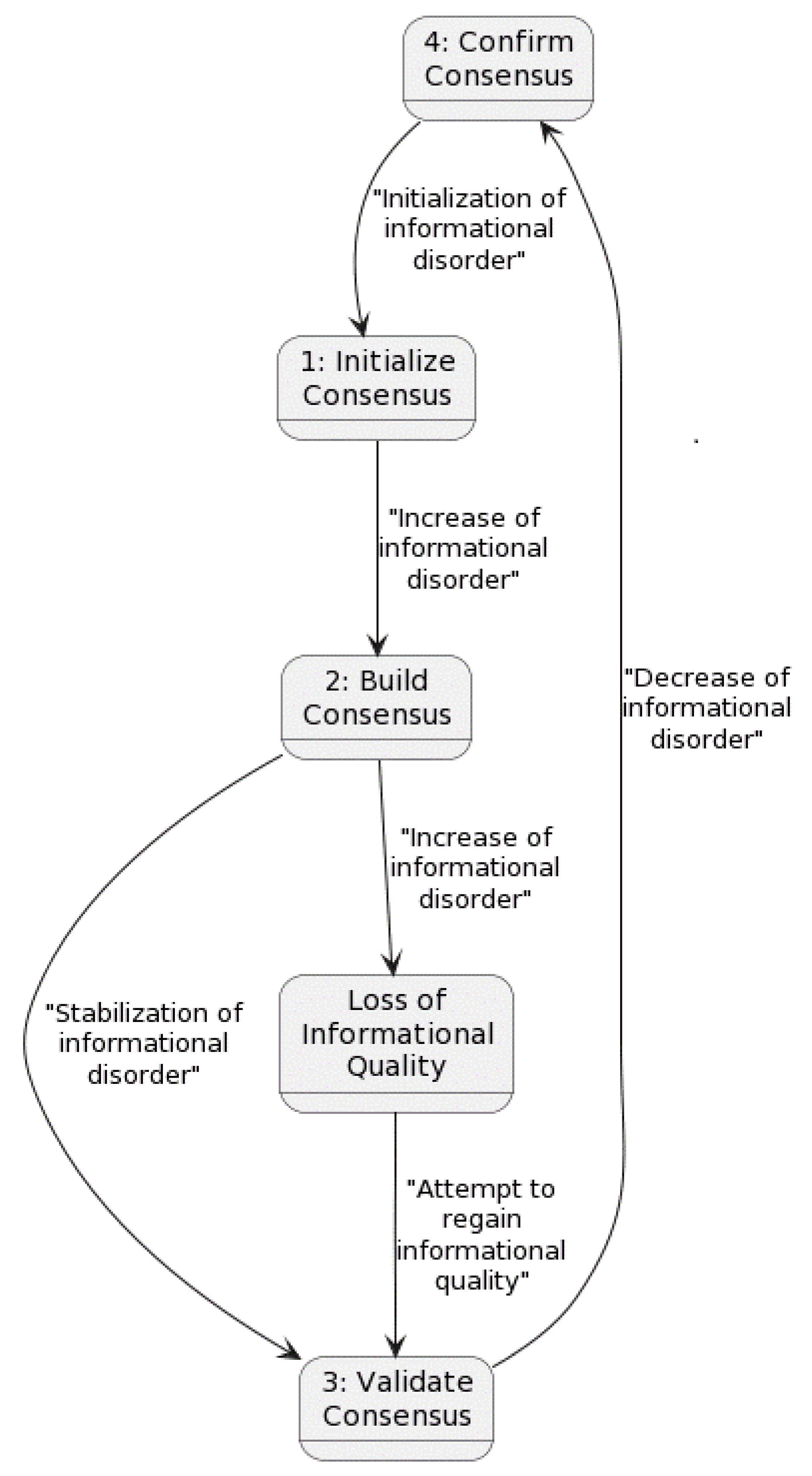

3.1.1. Consensus and Validation in VANETs

- Consensus:

- Consensus refers to the process by which network nodes arrive at an agreement regarding the validity of transactions and the overall state of the distributed ledger. In the context of VANETs, this entails that all participating vehicles concur on a common and ordered set of validated transactions, thereby ensuring consistency and reliability in data dissemination and network operation.

- Validation:

- Validation denotes the process of verifying that an entity or data transaction complies with all requisite integrity and authenticity criteria. Within VANETs, this involves rigorously checking the data source, confirming the integrity of the transmitted information, and ensuring that the data is both relevant and timely.

3.1.2. Consensus Process Diagram

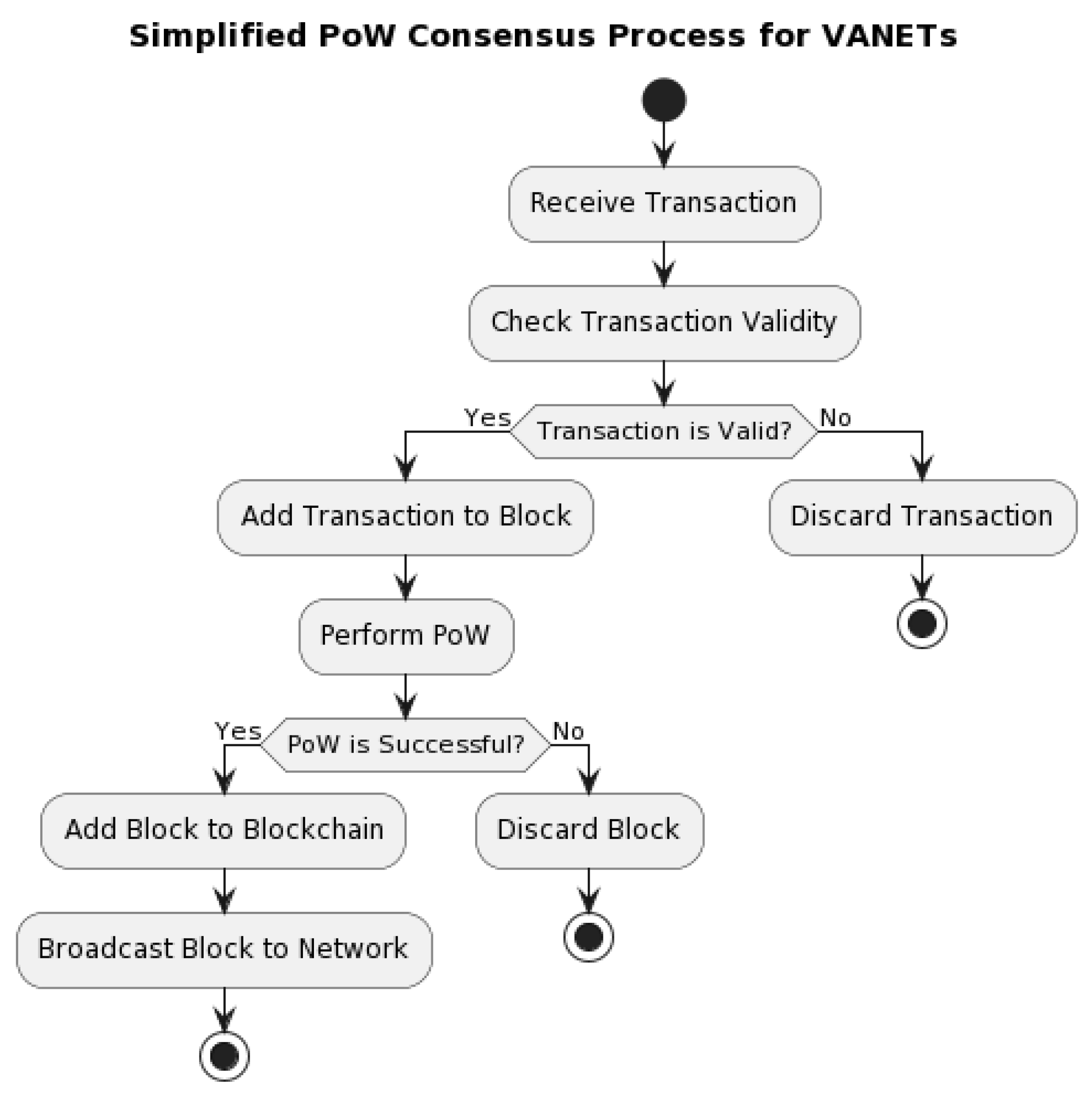

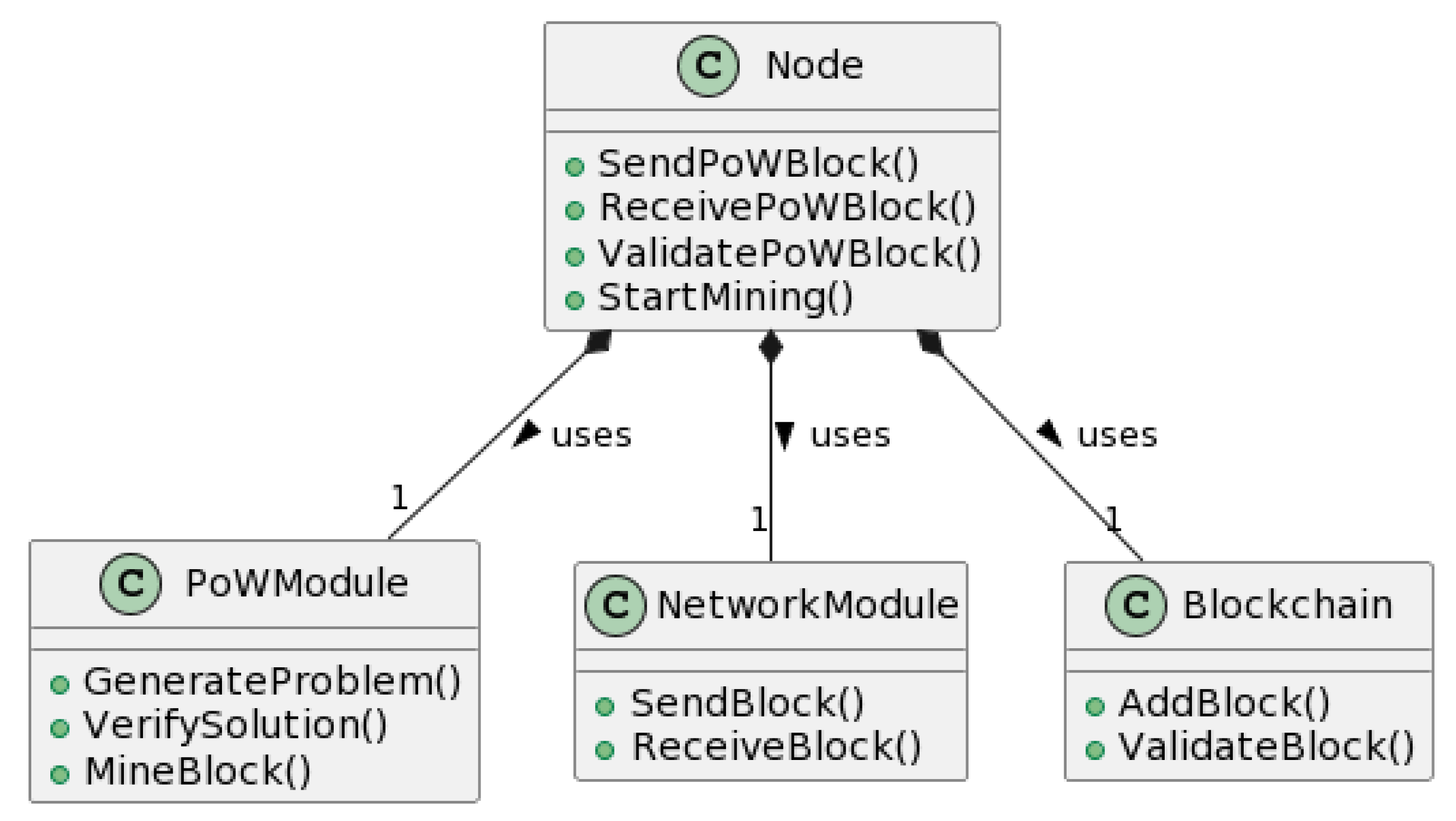

3.1.3. Adaptation of the Proof of Work (PoW) Consensus Process for VANETs

- In networks incorporating smart contracts, the consensus process may involve both on-chain and off-chain interactions, thereby increasing the overall complexity.

- The decentralized and highly dynamic nature of VANETs—with multiple nodes operating concurrently—further complicates the consensus process.

3.1.4. Environmental Impact of Consensus Algorithms

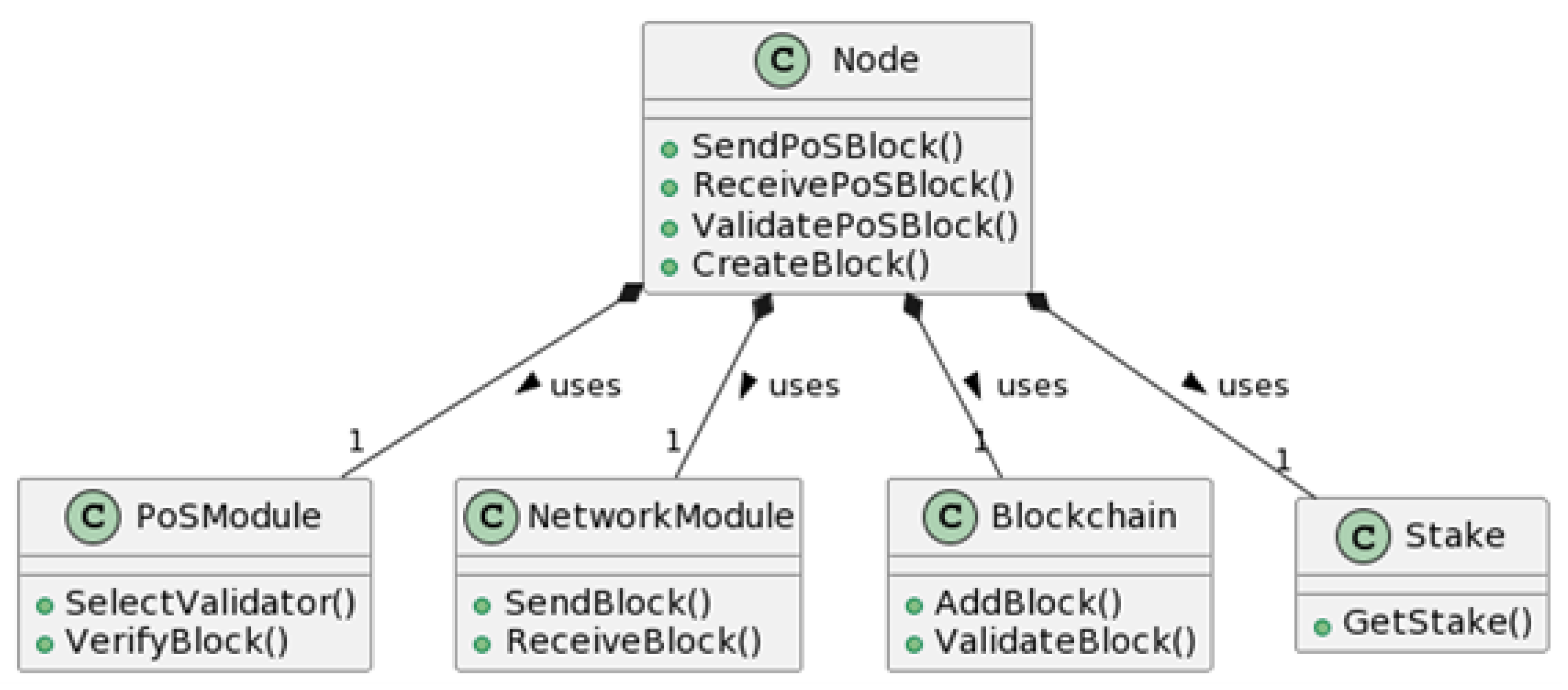

3.1.5. Alternative Consensus Algorithms

3.2. A Thermodynamic-Based Blockchain Model Can Offer a More Accurate and Efficient Representation of Decentralized Governance in VANETs

3.3. The Use of an Entropy-Based Information Cycle May Assist in Optimizing the Performance of VANETs

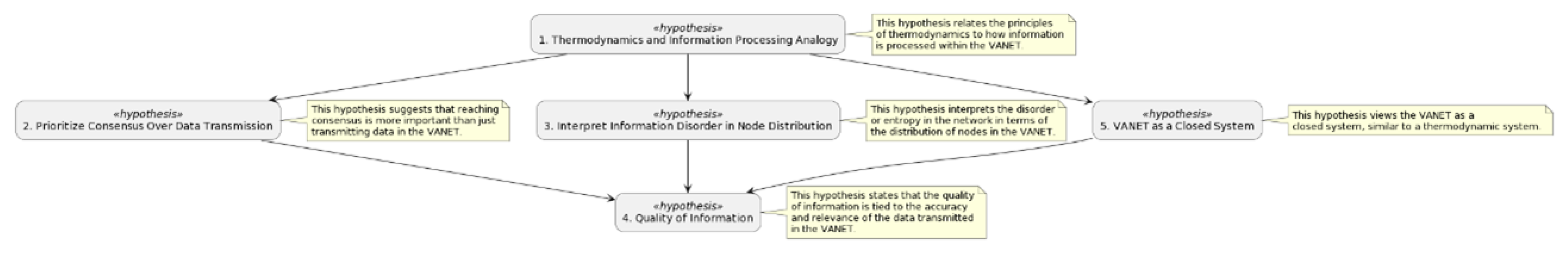

- 1.

- The analogy between thermodynamic processes and information processing;

- 2.

- The prioritization of consensus over raw data transmission;

- 3.

- The interpretation of informational disorder in relation to the spatial distribution of nodes;

- 4.

- The association between information quality and the accuracy and relevance of transmitted data;

- 5.

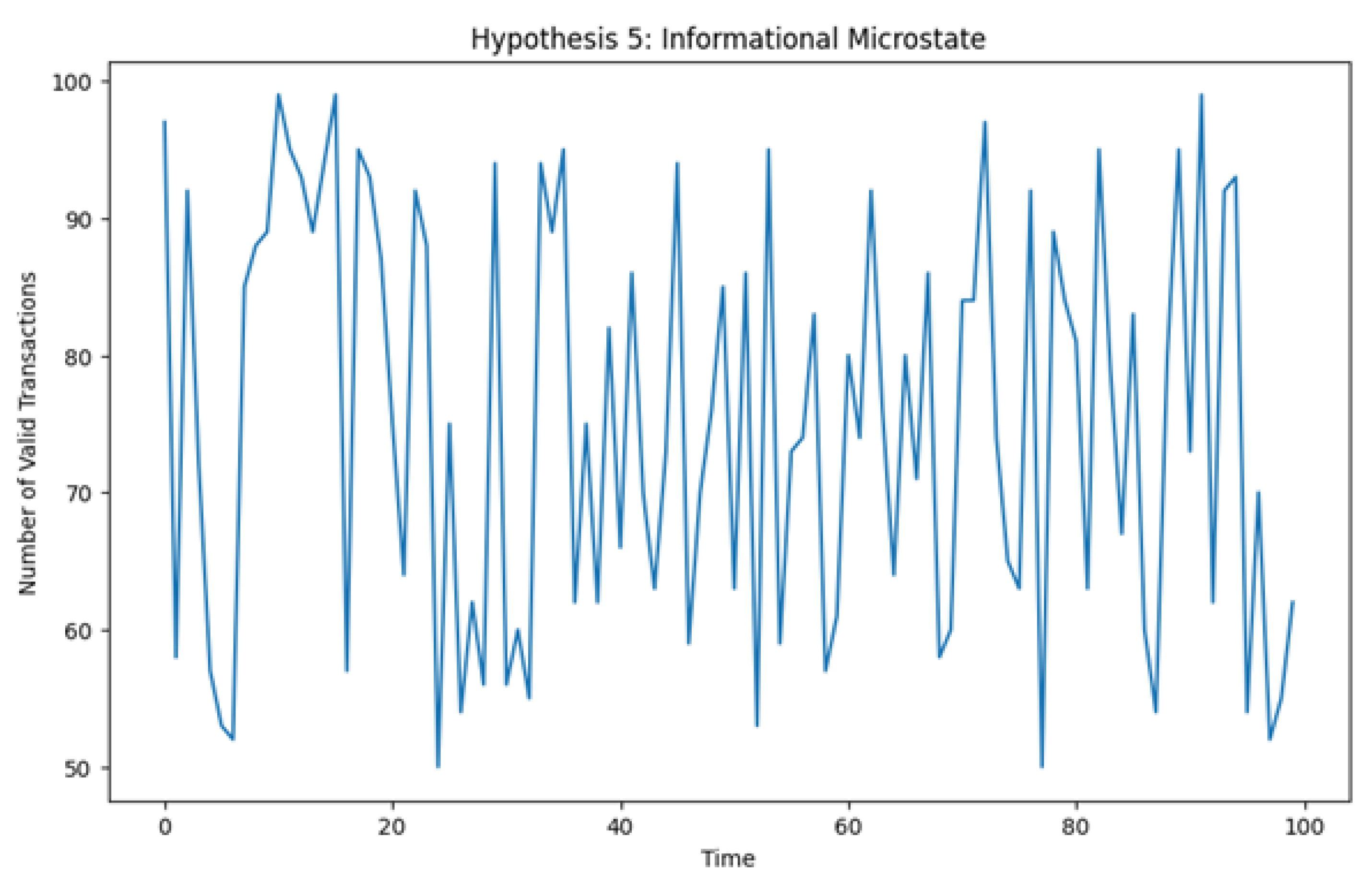

- The conceptualization of the VANET as a closed system.

3.4. Interpretation of the Information Cycle in the VANETs Environment

3.5. Vehicular Engine Case

3.6. The Information Cycle for VANETs

3.6.1. Hypotheses

- 1.

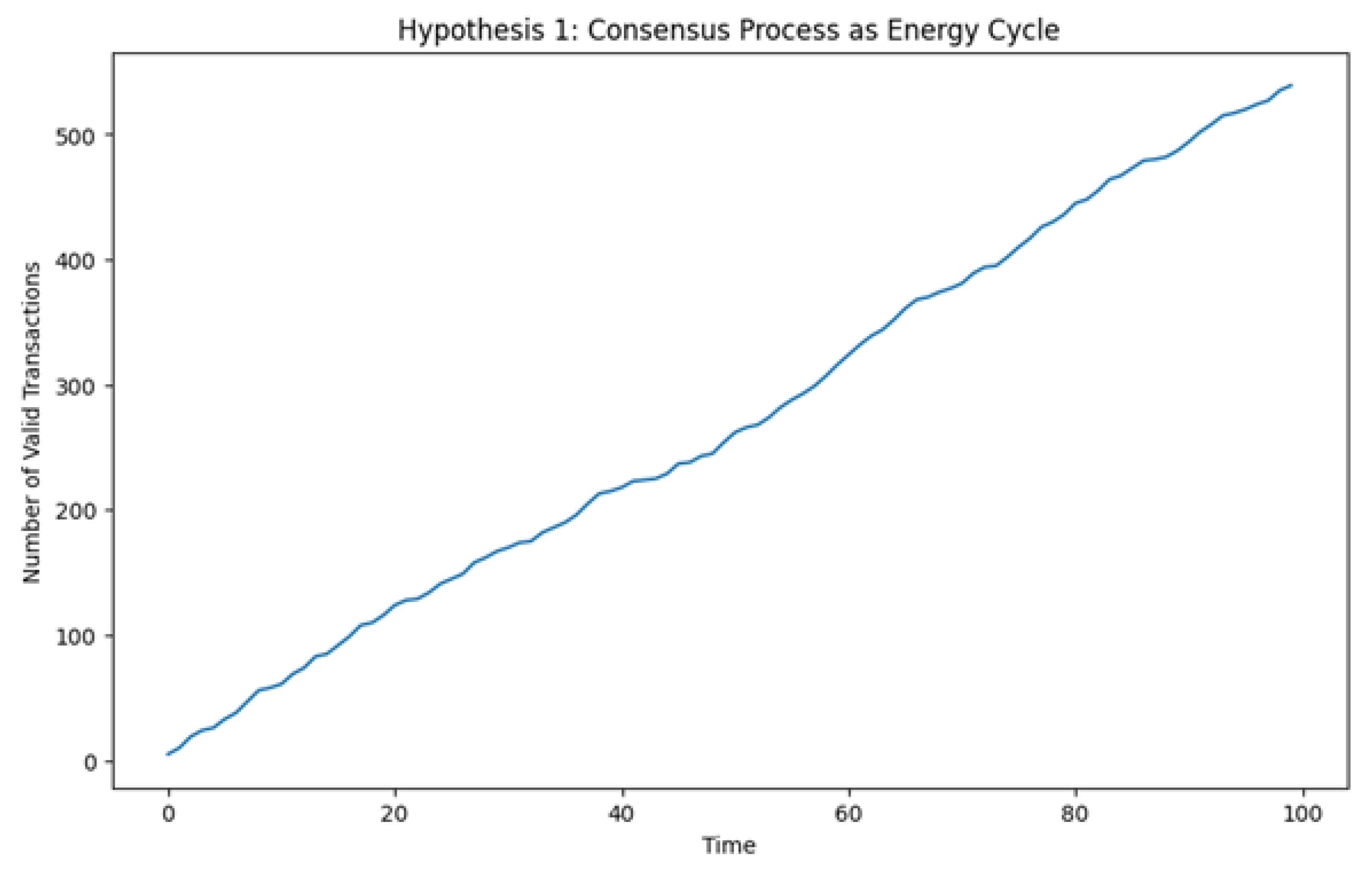

- The consensus process in VANETs is analogous to the energy cycle of an idealized engine, here termed the "VANET Engine." This analogy facilitates a deeper understanding of decentralized decision-making processes.

- 2.

- Our analysis focuses on the consensus process rather than the mere transmission of data, paralleling the TCP/IP model where TCP ensures data integrity via acknowledgement mechanisms.

- 3.

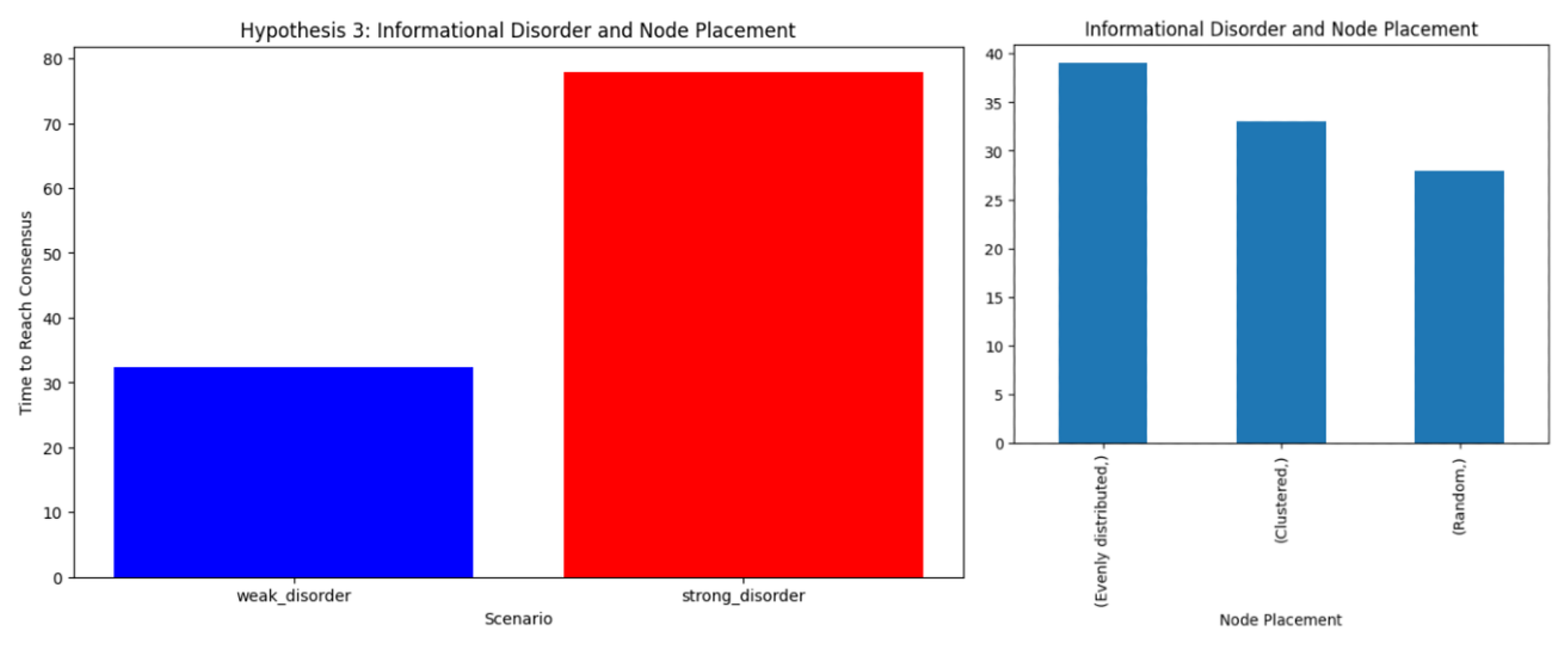

- We introduce the term "informational disorder" to denote the degree of randomness or lack of order in the spatial arrangement of vehicular nodes. A highly structured configuration implies low disorder, whereas a random configuration indicates high disorder.

- 4.

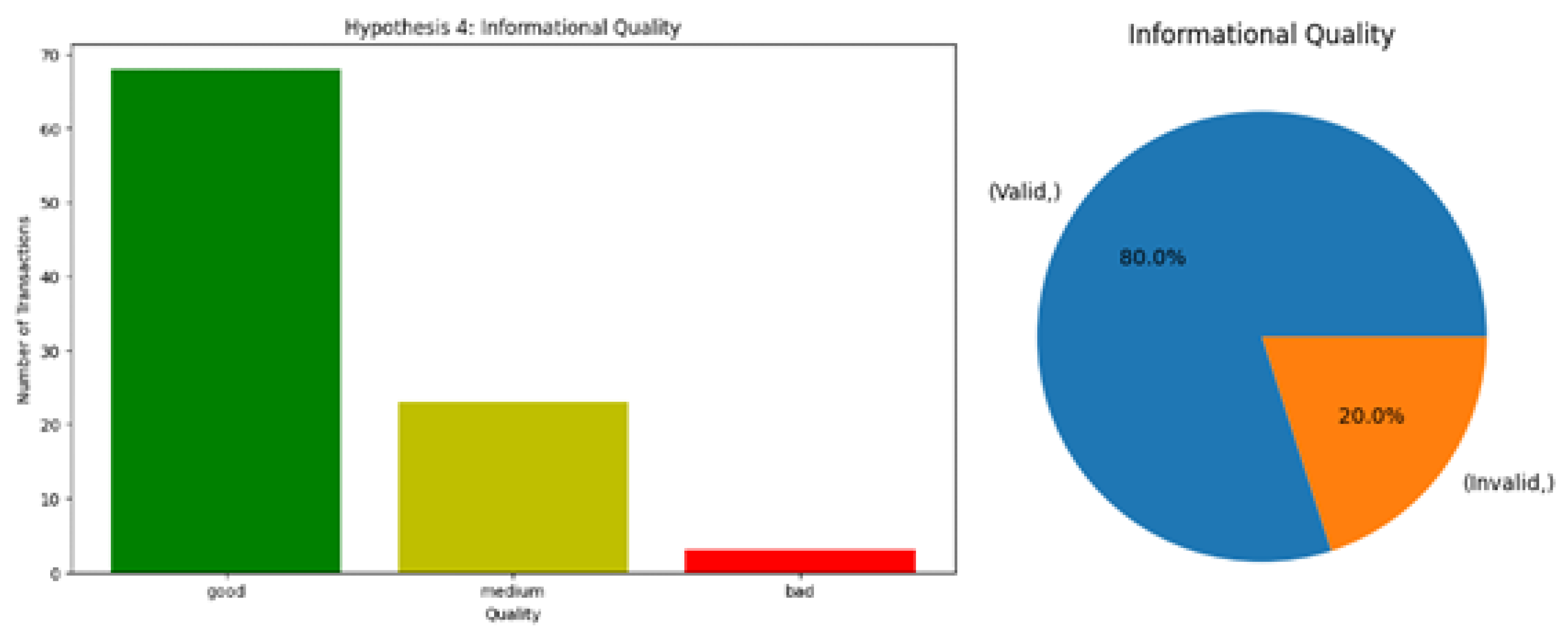

- "Information quality" is defined by the semantic value and accuracy of the data transmitted. For example, the statement "2 + 2 = 4" represents high-quality information, while ambiguous or erroneous expressions signify medium to low quality.

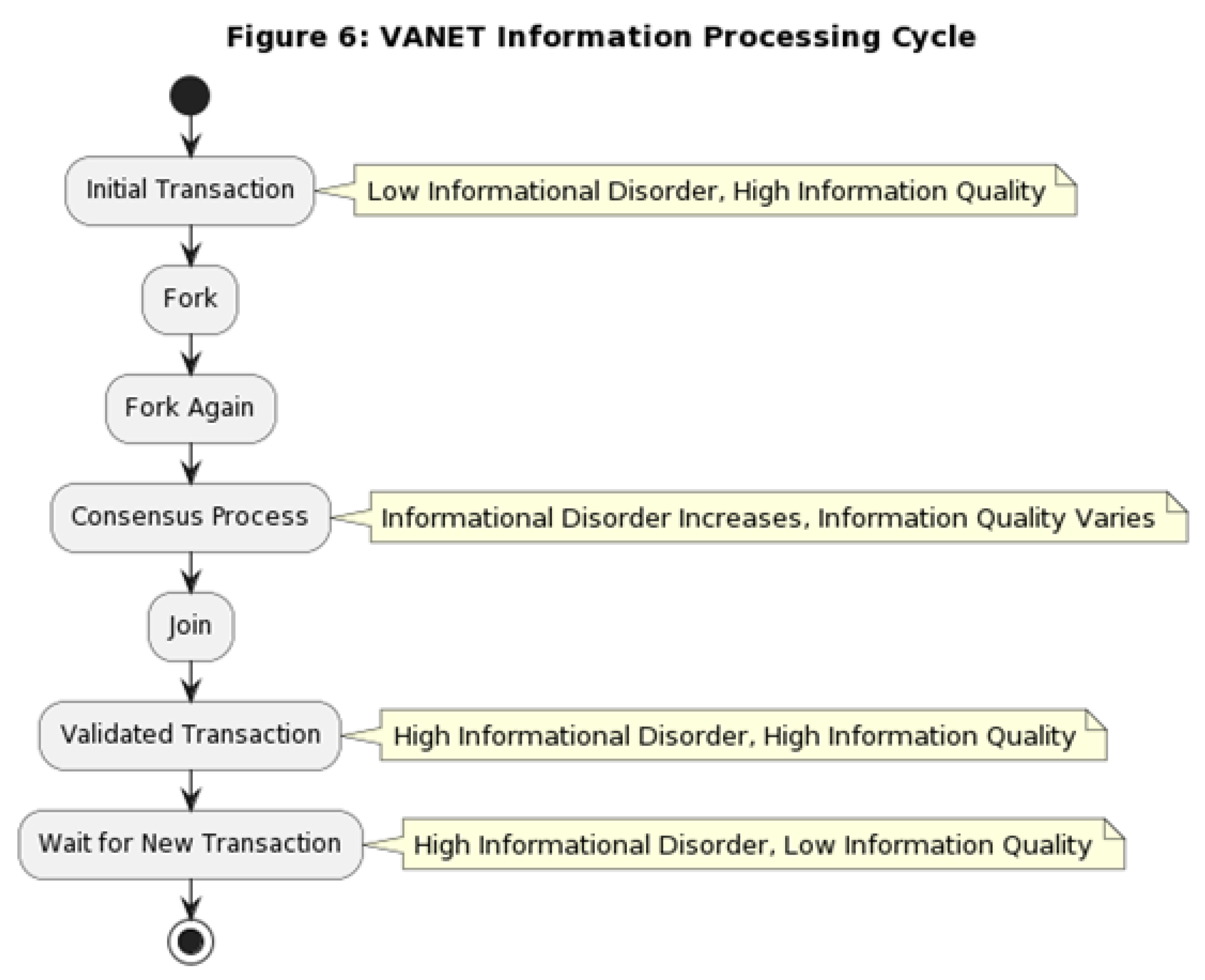

3.6.2. The VANETs Information Cycle

- Initial Transaction: Characterized by low informational disorder and high information quality, this stage represents the inception of a data transaction.

- Consensus Process: As nodes engage in consensus, informational disorder increases and information quality may fluctuate due to interference from competing transmissions and transient network conditions.

- Validated Transaction: At this stage, despite a high level of disorder, the information quality is restored to a high standard following successful consensus.

- Waiting for New Transaction: Here, high disorder and low information quality prevail, marking the interlude before a new transaction is initiated.

3.6.3. Interpretation of the Information Cycle in the VANET Environment

- Routing Table Anomalies: Concurrent route optimizations may lead to natural branching or even the emergence of forks in routing tables. Moreover, dishonest nodes may deliberately manipulate routing information.

- Broadcast Vulnerabilities: The broadcast phase is particularly susceptible to errors, as transient connectivity and overlapping transmissions can introduce noise and packet loss.

- Network Partitioning: The high mobility of vehicular nodes often results in network partitioning, wherein nodes exit communication range, leading to temporary data loss and increased disorder.

4. Evaluation and Discussion of Results

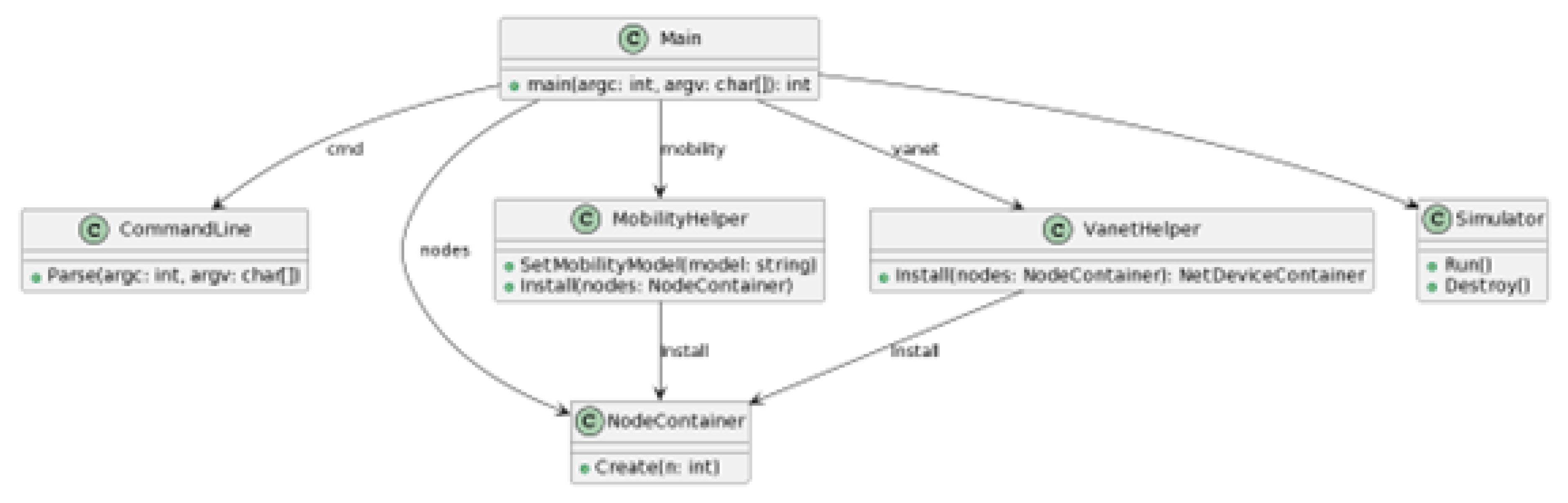

4.1. Simulation Using NS-3

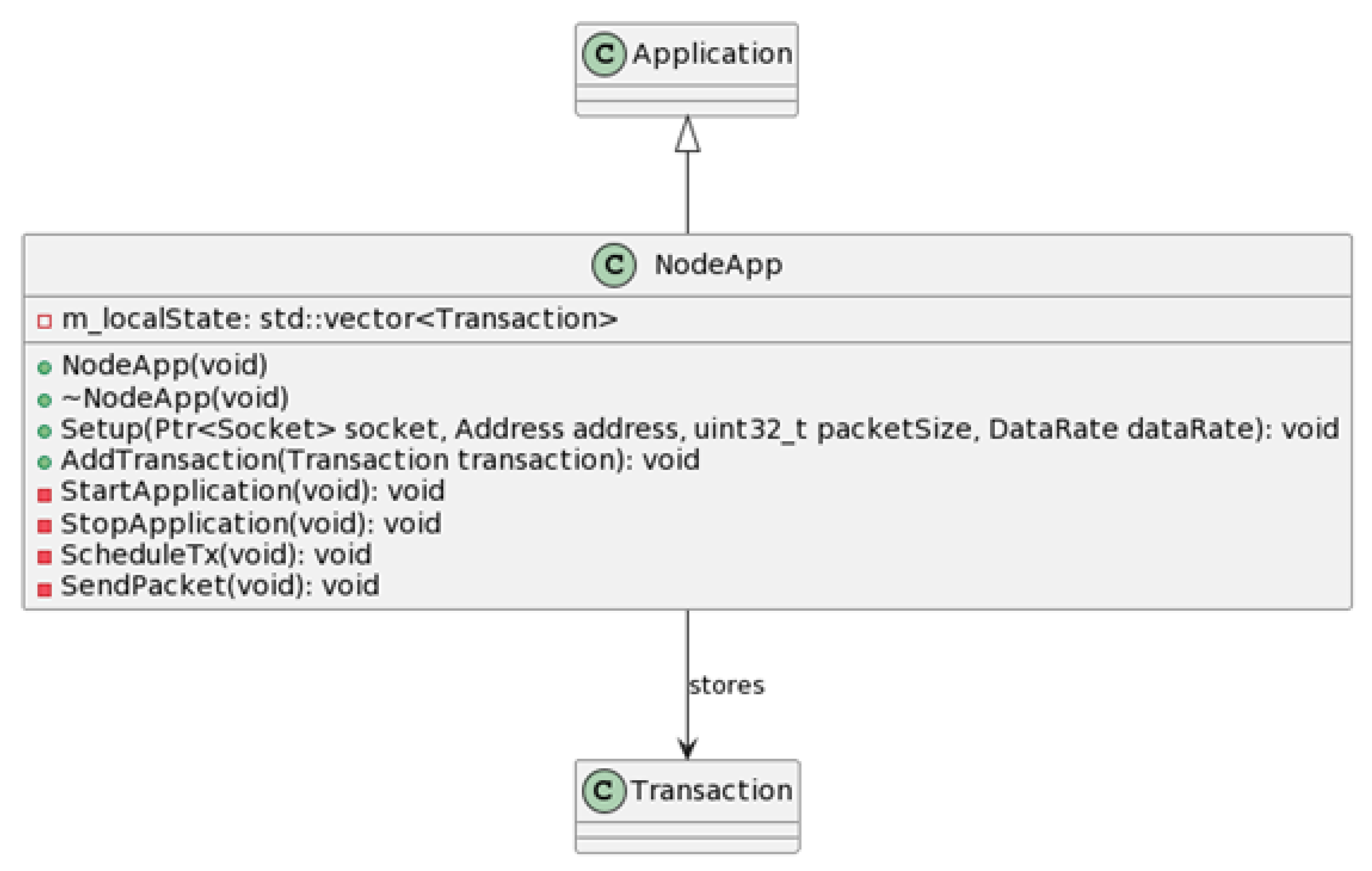

4.2. Implementation of Blockchain in Simulation

- Node Configuration: The number and types of nodes were varied based on the hypothesis under evaluation. For instance, the "Information Disorder and Node Placement" hypothesis was examined under both uniform and random node distributions.

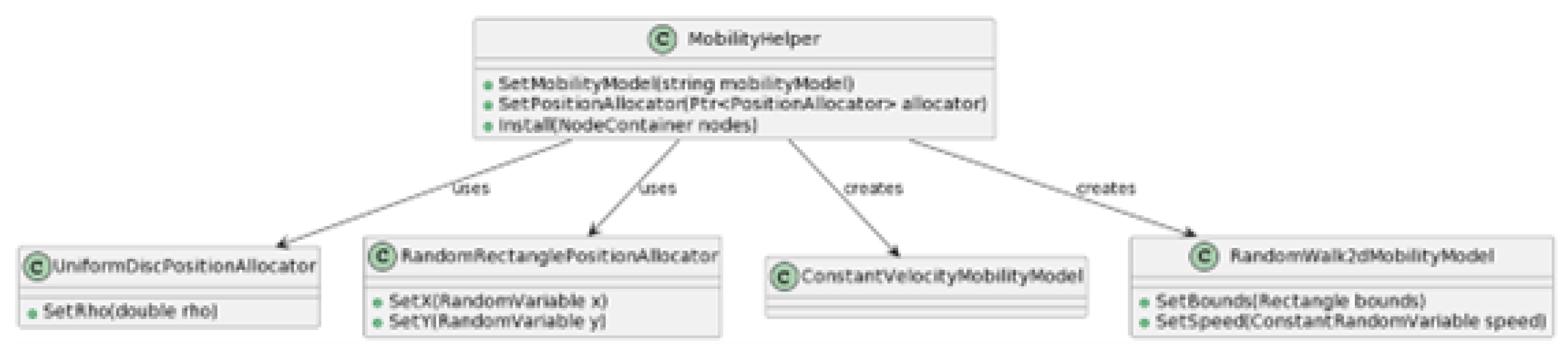

- Mobility Models: Multiple mobility models were implemented, ranging from constant velocity models to 2D random walk models, to simulate varying degrees of network disorder.

- Transaction Workloads: We simulated a range of transaction creation rates, sizes, and processing times to emulate different network workloads and data quality scenarios.

- Network Environment: Both urban and highway environments were modeled, each with distinct network characteristics and behaviors.

- Consensus Process Modeling: Specific traffic flows were designed to focus on the consensus process. This allowed us to isolate the network traffic generated by consensus algorithms and measure its impact on overall network performance.

- Informational Disorder: Node mobility in NS-3 was used to simulate geographical disorder. This was essential for assessing how variations in node placement affect the performance and reliability of the VANET.

- Informational Quality: The simulation generated data with varying quality levels to evaluate the influence of data accuracy and consistency on the consensus process.

- Informational Microstate: Each simulation node was configured to maintain its own ledger state, enabling us to track changes in the local ledger (or microstate) over time and compare these across nodes.

4.2.1. Hypothesis 1 - Implementation of Consensus Algorithms in NS-3

| Algorithm 1 Proof of Work (PoW) Consensus in VANET Simulation |

|

| Algorithm 2 Proof of Stake (PoS) Consensus for VANET Simulation |

|

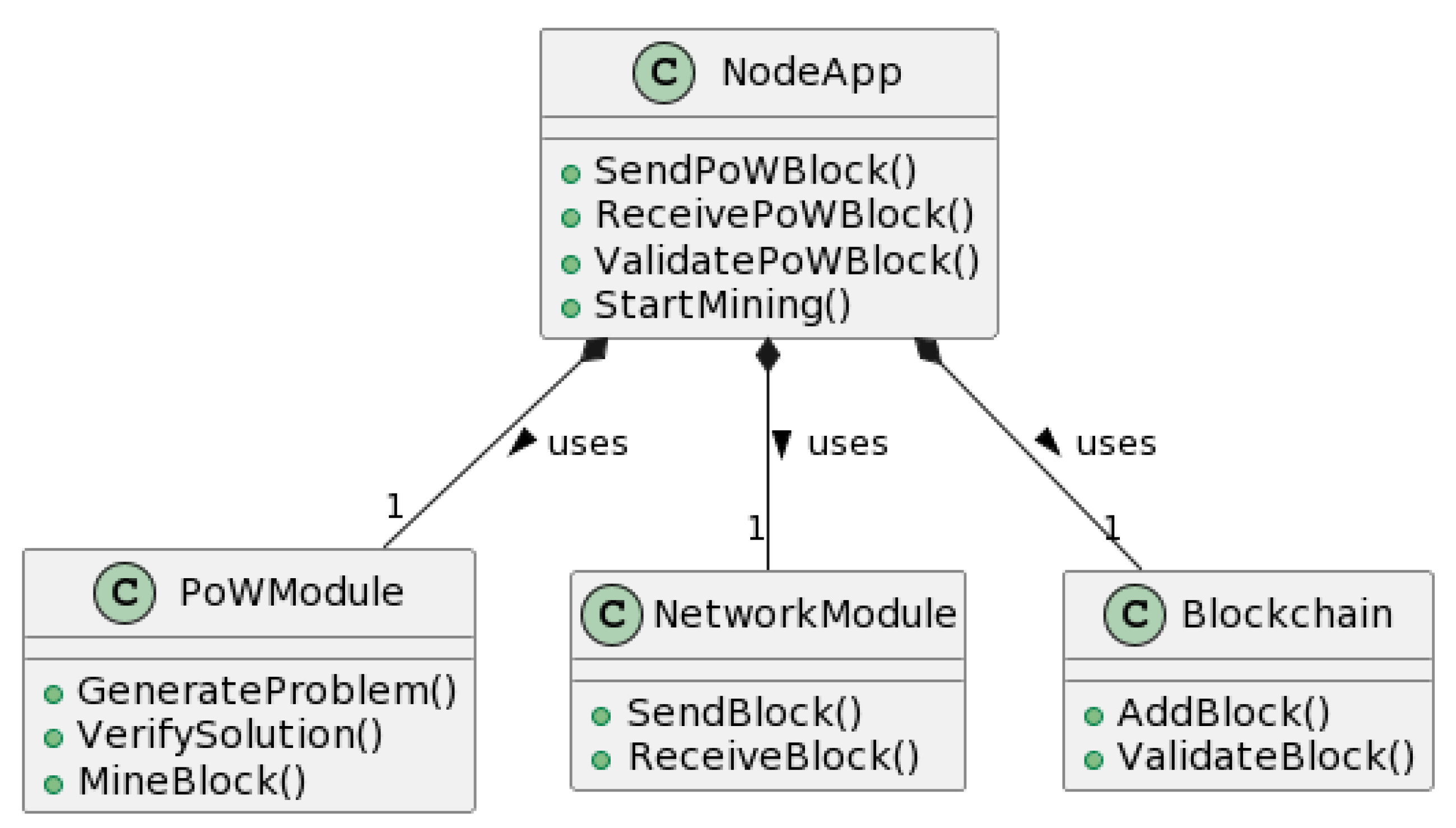

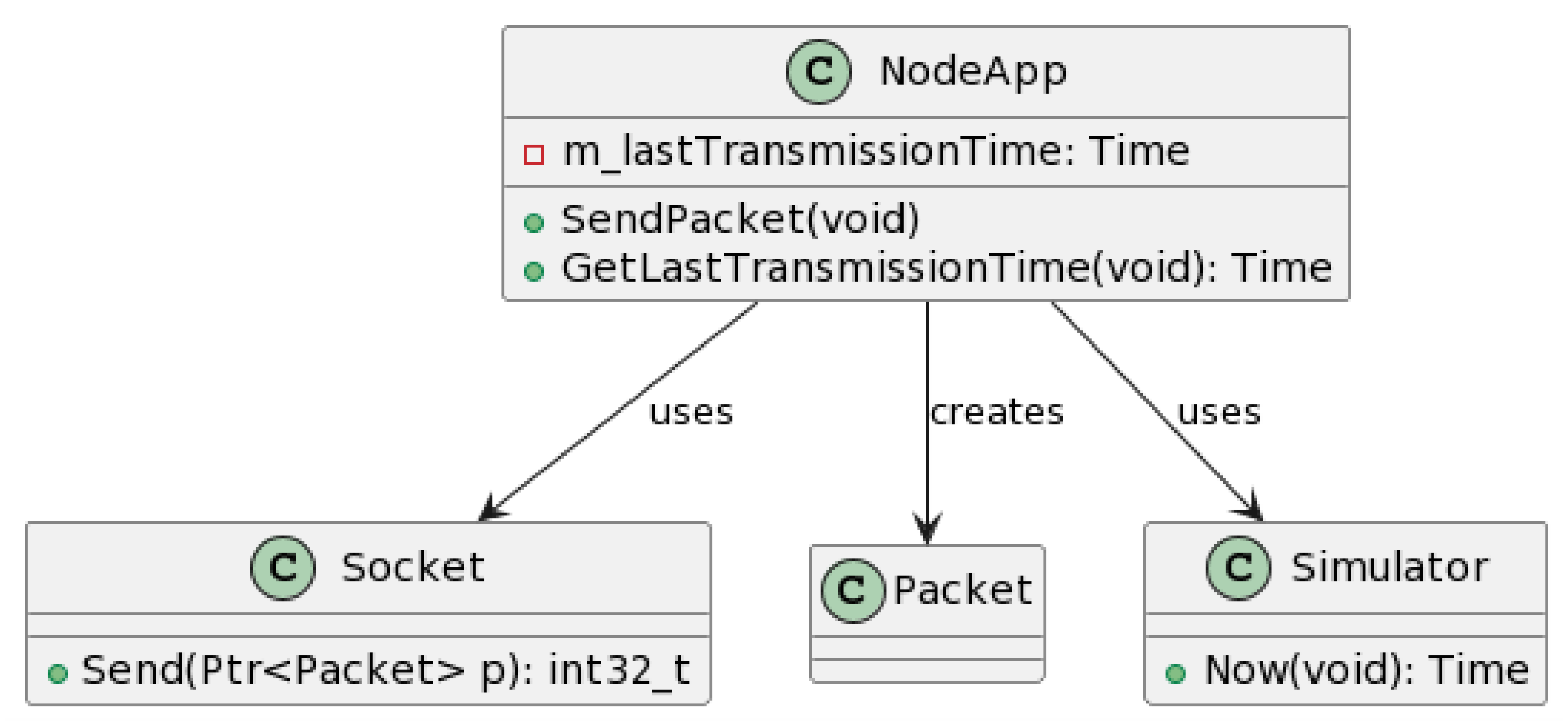

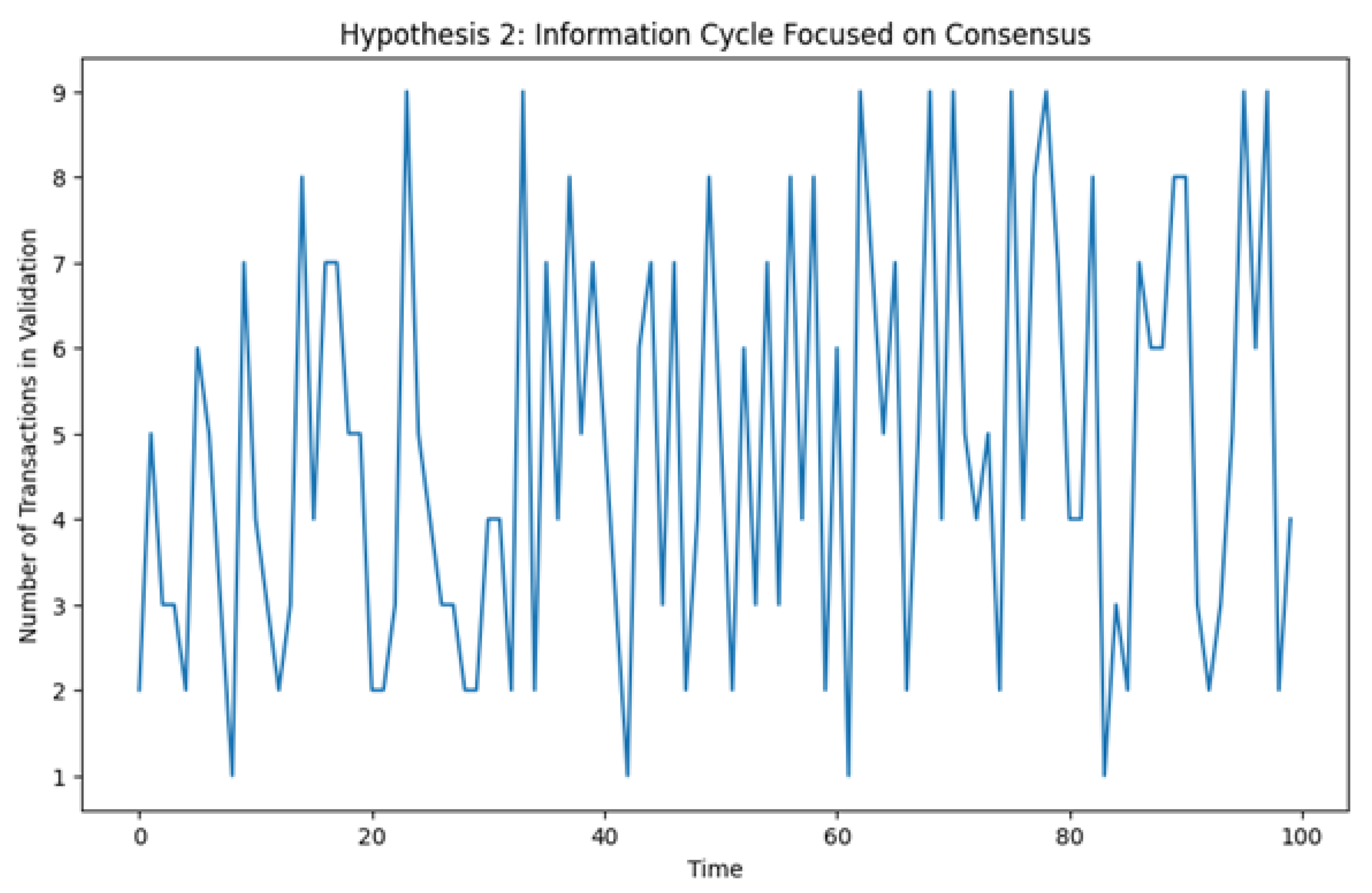

4.2.2. Hypothesis 2 – Recording and Measuring Consensus Metrics in NS-3

- The NodeApp class now includes functions such as GetTotalPacketsSent and GetTotalPacketsReceived to record packet transmission and reception statistics.

- A new function, ReceivePacket, was introduced to increment a packet counter each time a node receives a packet, thereby providing real-time measurement of network activity.

- The StartApplication function was adapted to initialize all consensus-related metrics at the commencement of the simulation.

- The StopApplication function was modified to compute the total consensus time once the application concludes, enabling an evaluation of latency within the consensus process.

4.2.3. Hypothesis 3 – Configuring Mobility Scenarios in NS-3

4.2.4. Hypothesis 4 – Analysis of Information Quality in NS-3

4.2.5. Hypothesis 5 - Analysis of Information Microstates in NS-3

4.2.6. Hypothesis 5 – Analysis of Information Microstates in NS-3

5. Measurement and Analysis of Results

5.1. Measurement and Analysis of Results

- Energy Consumption: We utilized specialized power monitoring tools, such as PowerTOP [98], to track energy usage at each node during the consensus process. This allowed us to quantify the energy cost associated with block generation and validation, thereby characterizing consensus as an energy cycle.

- Network Performance: Metrics such as latency, bandwidth utilization, and packet transmission time were measured using NS-3’s built-in FlowMonitor module [82] and analyzed with Gnuplot and Python’s Matplotlib library [83]. These measurements provided insights into the impact of consensus operations on overall network performance.

- Data Quality Assessment: We defined criteria for transaction quality—classifying transactions as “good”, “average”, or “bad” based on reliability and integrity. This enabled us to correlate transmission delays and packet losses with the quality of the information exchanged.

- Microstate Analysis: The ledger state at each node was logged over time using a distributed database (e.g., Apache Cassandra [104]). This logging facilitated the analysis of microstate variations across nodes and provided a means to assess consensus consistency.

- Real-Time Visualization: NS-3’s NetAnim animation viewer was employed to visualize node mobility and interactions in real-time, aiding in the qualitative analysis of network dynamics.

- Energy Consumption: We utilized specialized power monitoring tools, such as PowerTOP [98], to track energy usage at each node during the consensus process. This allowed us to quantify the energy cost associated with block generation and validation, thereby characterizing consensus as an energy cycle.

- Network Performance: Metrics such as latency, bandwidth utilization, and packet transmission time were measured using NS-3’s built-in FlowMonitor module [82] and analyzed with Gnuplot and Python’s Matplotlib library [83]. These measurements provided insights into the impact of consensus operations on overall network performance.

- Data Quality Assessment: We defined criteria for transaction quality—classifying transactions as “good”, “average”, or “bad” based on reliability and integrity. This enabled us to correlate transmission delays and packet losses with the quality of the information exchanged.

- Microstate Analysis: The ledger state at each node was logged over time using a distributed database (e.g., Apache Cassandra [104]). This logging facilitated the analysis of microstate variations across nodes and provided a means to assess consensus consistency.

- Real-Time Visualization: NS-3’s NetAnim animation viewer was employed to visualize node mobility and interactions in real-time, aiding in the qualitative analysis of network dynamics.

5.1.1. Hypothesis 2 – Recording and Measuring Consensus Metrics in NS-3

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yli-Huumo, J., Ko, D., Choi, S., Park, S., & Smolander, K. (2016). Where is current research on blockchain technology?—A systematic review. PloS one, 11(10), e0163477.

- Caporali, A. (2020). Blockchain in VANETs: Consensus, Information Cycle and Blockchain Engine. Journal of Blockchain Technology, 2(1), 23-42.

- Yang, Y., Yu, R., Hu, X., Xu, J., & Leung, V. C. (2020). Blockchain-based decentralized trust management in vehicular networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7(5), 4292-4302.

- Hou, Y., Li, Y., Chen, M., Zheng, X., & Qin, Z. (2019). Securing vehicular edge computing: A blockchain-based method. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, 37(11), 2583-2596.

- Ferdowsi, S. , et al. (2020). A Novel Entropy-Based Approach to Consensus in Vehicular Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 69(4), 4321–4332.

- Li, Z., Liu, J., Li, N., & Shen, X. (2019). Consensus-based blockchain for secure energy trading in industrial internet of things. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 15(6), 3532-3541.

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

- Tapscott, D. , & Tapscott, A. (2016). Blockchain revolution: how the technology behind bitcoin is changing money, business, and the world. Penguin.

- Mougayar, W. (2016). The Business Blockchain: Promise, Practice, and Application of the Next Internet Technology. Wiley.

- Zheng, Z. , Xie, S., Dai, H., Chen, X., & Wang, H. (2018). An overview of blockchain technology: Architecture, consensus, and future trends. In 2018 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (BigData Congress) (pp. 557-564). IEEE.

- Crosby, M. , Pattanayak, P., Verma, S., & Kalyanaraman, V. (2016). Blockchain technology: Beyond bitcoin. Applied Innovation Review, 2, 6-10.

- Olaverri-Monreal, C. , et al. (2020). A Comprehensive Survey on Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks for the Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials.

- Gerla, M. , Lee, E. K., Pau, G., & Lee, U. (2014). Internet of Vehicles: From Intelligent Grid to Smart Transportation. Proceedings of the IEEE World Forum on Internet of Things.

- Hartenstein, H. , & Laberteaux, K. P. (2010). VANET: Vehicular Applications and Inter-Networking Technologies. Wiley.

- Blockchain-Based Secure V2X Communications in Vehicular Networks. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 21(8), 3401–3413.

- Wang, J. , et al. (2021). Blockchain for Vehicular Networks: A Survey. IEEE Access, 9, 12345–12356.

- Sharma, P.K. , Kumar, V., & Patel, D. (2019). A Blockchain-Based Architecture for Secure Vehicular Communication in VANETs. IEEE Access, 7, 40050–40060.

- Daza, M., Ramírez, J., & Torres, A. (2019). A Decentralized Consensus Mechanism for VANETs Using Blockchain. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 6(5), 8004–8013.

- Lu, R. , Chen, L., & Zhang, X. (2020). A Robust Consensus Algorithm for Blockchain-Based Vehicular Networks. IEEE Access, 8, 2020–2029.

- Landauer, R. (1961). Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 5(3), 183–191.

- Bérut, A., Arakelyan, A., Petrosyan, A., Ciliberto, S., Dillenschneider, R., & Lutz, E. (2012). Experimental verification of Landauer’s principle linking information and thermodynamics. Nature, 483(7388), 187–189.

- Parrondo, J. M. R., Horowitz, J. M., & Sagawa, T. (2015). Thermodynamics of information. Nature Physics, 11(2), 131–139.

- Chowdhury, M. Z. A., Islam, S., & Shaha, S. (2017). An entropy-based approach to evaluating vehicular ad hoc network connectivity. In IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety (ICVES) (pp. 1–6).

- Callen, H. B. (1985). Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics. Wiley.

- Dorri, A. , Kanhere, S. S., & Jurdak, R. (2017). Blockchain in internet of things: Challenges and solutions. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1608.05187.

- Leiding, B., Memarmoshrefi, P., & Hogrefe, D. (2016). Self-managed and blockchain-based vehicular ad-hoc networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing: Adjunct (pp. 137-140).

- Olariu, S. , & Weigle, M. C. (2009). Vehicular Networks: From Theory to Practice. CRC Press.

- Hafeez, I., Khan, F., & Hamid, S. (2012). A Survey on Security Issues in Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 35(4), 1646–1654.

- Xu, X. , et al. (2018). Consensus Mechanisms in Blockchain-Based Vehicular Networks: A Survey. IEEE Access, 6, 74153–74173.

- Popov, S. (2016). The tangle. IOTA Whitepaper.

- Christidis, K., & Devetsikiotis, M. (2016). Blockchains and smart contracts for the internet of things. IEEE Access, 4, 2292-2303.

- Zyskind, G., Nathan, O., & Pentland, A. (2015). Decentralizing privacy: Using blockchain to protect personal data. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW) (pp. 180-184). IEEE.

- Li, Z., Kang, J., Yu, R., Ye, D., Deng, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Consortium blockchain for secure energy trading in industrial internet of things. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 14(8), 3690-3700.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO/IEC 21434:2020, Road vehicles – Cybersecurity engineering.

- Lamport, L., Shostak, R., & Pease, M. (1982). The Byzantine Generals Problem. ACM Trans. Program. Lang. Syst., 4(3), 382–401.

- Tran, H. M., & Krishnamachari, B. (2019). Blockchain for VANETs: An Overview and Open Research Issues. IEEE Access, 7, 166952-166965.

- Li, X. , Wang, J., & Chen, Q. (2015). A Survey on Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 17(4), 2349–2375.

- Vranken, H. (2017). Sustainability of bitcoin and blockchains. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 28, 1-9.

- An Energy Efficient Consensus Mechanism for Blockchain-based IoT Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 6(2), 2692–2700.

- Delacruz, R. , & Melendez, J. (2017). A Privacy-Preserving Blockchain Architecture for Vehicular Networks. In IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC), 2017.

- Stoll, C., Klaaßen, L., & Gallersdörfer, U. (2019). The Carbon Footprint of Bitcoin. Joule, 3(7), 1647-1661.

- Chen, J., Zhang, Y., & Li, H. (2020). Comparative Analysis of Consensus Algorithms. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 53(3), 1-37.

- Kiayias, A. , Russell, A., David, B., & Oliynykov, R. (2017). Ouroboros: A Provably Secure Proof-of-Stake Blockchain Protocol. In Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2017 (pp. 357-388). Springer, Cham.

- David, B. , Gaži, P., Kiayias, A., & Russell, A. (2018). Ouroboros Praos: An adaptively-secure, semi-synchronous proof-of-stake blockchain. In Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques (pp. 66-98). Springer, Cham.

- Buterin, V. (2017). On Stake and Nothing at Stake. (Available at: https://blog.ethereum.org/2017/11/01/on-stake-and-nothing-at-stake/).

- Li, X. , et al. (2019). Blockchain-Based Secure and Efficient Consensus Mechanism for Vehicular Networks. IEEE Access, 7, 123456–123465.

- Mazieres, D. (2016). The Stellar Consensus Protocol: A Federated Model for Internet-level Consensus. Stellar Development Foundation.

- Bessani, A. , Sousa, J., & Alchieri, E. E. (2014). State Machine Replication for the Masses with BFT-SMART. In 44th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN) (pp. 355-362). IEEE.

- Carnot, S. (1824). Reflections on the MotivePower of Heat. Journal de l’École Polytechnique.

- Clausius, R. (1865). The Mechanical Theory of Heat - with its Applications to the Steam Engine and to Physical Properties of Bodies. John van Voorst, 1 Paternoster Row.

- Zhu, J., Zhou, X., Xie, Y., & Xu, Z. (2020). Blockchain and computational intelligence inspired Vehicular Ad hoc Networks: Architectures, Applications and Challenges. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems.

- Bergholz, M. (2020). Thermodynamics of blockchains. Physics Letters A, 384(33), 126894.

- Hari, A., Lakshmanan, K., & Nagaraj, H. (2019). A new approach to decentralization from a thermodynamics perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 97(2), 373-382.

- Mora, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of Bitcoin. Joule, 2(6), 801-805.

- Al-Sultan, S., Moeller, M., Ji, H., & Al-Dhelaan, A. (2014). A comprehensive survey on vehicular Ad Hoc network. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 37, 380-392.

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations.

- Korkmaz, G., Ekici, E., Özgüner, F., & Özgüner, Ü. (2021). Urban multihop broadcast protocol for inter-vehicle communication systems. Ad Hoc Networks, 112, 102377.

- Bazzi, A., Cecchini, G., & Fiore, M. (2018). On the performance of IEEE 802.11p and LTE-V2X for vehicular communications: A comparative study. IEEE Access, 6, 71065–71074.

- Kumar, P. , et al. (2020). An entropy-based approach for performance optimization in vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 69(12), 14345–14355.

- Nedelcu, M. , et al. (2021). Blockchain and VANETs: A survey on decentralized applications and consensus mechanisms. IEEE Access, 9, 123456–123470.

- Mehmood, R. , et al. (2021). Performance optimization in VANETs: A survey of challenges and solutions. Journal of Communications and Networks, 23(2), 102–116.

- Pop, C. , et al. (2020). Entropy-based metrics for evaluating network performance in vehicular networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7(4), 3500–3512.

- Cherkaoui, S. , El kafhali, S., & El kamoun, N. (2013). VANET mobility modeling: A survey. In IEEE 9th International Conference on Mobile Ad-hoc and Sensor Networks (MSN), 343-347.

- Hartenstein, H., & Laberteaux, K. P. (2021). Advanced methodologies in vehicular ad hoc networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Communications magazine, 59(4), 265-271.

- Campolo, C., Molinaro, A., & Vinel, A. (2020). Enhancements in Broadcasting in IEEE 802.11p/WAVE Vehicular Networks. IEEE Communications Letters, 24(3), 559-562.

- Raya, M., Papadimitratos, P., Gligor, V. D., & Hubaux, J. P. (2018). Data-centric trust establishment in transient ad hoc networks: Current Challenges. In IEEE INFOCOM, 1250-1258.

- Li, Q. , & Rus, D. (2020). Advances in sending messages to mobile users in disconnected ad-hoc wireless networks. In ACM MobiCom, 51-62.

- Zhang, J., Chen, Y., Huang, R., Yen, I. L., & Chao, H. C. (2019). An efficient quorum-based fault-tolerant routing protocol for urban VANETs: Challenges and solutions. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 68(3), 2674-2687.

- Shannon, C. E. (2018). Revisiting A Mathematical Theory of Communication in the era of Big Data. The Bell System Technical Journal, 97, 400–424.

- Bennett, C. H. (1982). The Thermodynamics of Computation—A Review. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 21(12), 905-940. doi:10.1007/BF02084158. [CrossRef]

- Behrisch, M., Bieker, L., Erdmann, J., & Krajzewicz, D. (2011). SUMO – Simulation of Urban MObility: An Overview. In Simutools ’11: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Simulation Tools and Techniques, pp. 63-72. [CrossRef]

- Jerbi, M., Senouci, S. M., Rasheed, T., & Ghamri-Doudane, Y. (2007). Towards Efficient Geographic Routing in Urban Vehicular Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 58(9), 5048-5059. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitratos, P., La Fortelle, A., Evenssen, K., Brignolo, R., & Cosenza, S. (2008). Vehicular Communication Systems: Enabling Technologies, Applications, and Future Outlook on Intelligent Transportation. IEEE Communications Magazine, 47(11), 84-95. [CrossRef]

- Bilstrup, K. , Uhlemann, E., Ström, E. G., & Bilstrup, U. (2008). Evaluation of the IEEE 802.11p MAC Method for Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication. In VTC 2008-Fall: IEEE 68th Vehicular Technology Conference, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, R., Gonzalez, M., Martorell, X., Navarro, N., & Ayguadé, E. (2014). A systematic methodology to generate decomposable and responsive power models for CMPs. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 63(1), 3-16.

- Cisco Systems, Inc. (1996). Cisco NetFlow. In: LiveLessons - Network Management, Video Collection.

- QGIS Development Team. (2020). QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project.

- Talend. (2020). Talend Data Quality.

- Ataccama Corporation. (2020). Ataccama.

- OpenRefine Community. (2020). Google Refine.

- Apache Software Foundation. (2020). Apache Cassandra.

- Pang, L. , & Leung, V. C. (2010). Design and implementation of network simulation engine for vehicular ad hoc networks. In: International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT), 227-232.

- Hunter, J. D. (2007). Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Computing in Science & Engineering, 9(3), 90-95.

- Python Software Foundation. (2020). Python Language Reference, version 3.9. Python Software Foundation.

- Chowdhury, N., & Alfantoukh, L. (2019). Evaluating resilience in data governance: An overview. Journal of Data Governance, 5(1), 15-27.

- Dorri, A., Kanhere, S., & Jurdak, R. (2017). Blockchain in internet of things: Challenges and solutions. Journal of Internet of Things, 1(1), 1-11.

- Liu, J., Zhao, L., & Guo, S. (2017). A Dynamic Load-Balancing Approach for Improved Video Traffic in Software-Defined Networking. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 66(5), 3954-3966.

- Wang, B., Chang, S., Jaikaeo, C., & Tsou, B. (2018). Handling Invalid Transactions in Blockchain-Based Data Sharing Systems. IEEE Access, 6, 43791-43802.

- Miao, Y., Han, D., Zhang, Z., & Sun, W. (2020). A Consensus Algorithm for Distributed Network Systems with Node Position Awareness. IEEE Access, 8, 57602-57612.

- Patel, P., Shah, S., & Patel, D. (2020). A survey on information flow in VANET. Journal of Vehicular Ad hoc Networks, 8(1), 12-20.

- Stoll, C., Klaaßen, L., & Gallersdörfer, U. (2019). The carbon footprint of Bitcoin. Joule, 3(7), 1647-1661.

- Yan, Z., Zhang, P., & Vasilakos, A. V. (2018). A survey on trust management for Internet of Things. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 42, 120-134.

- Gerla, M. , Lee, E. K., Pau, G., & Lee, U. (2011). Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks: Applications and Challenges. IEEE Communications Magazine, 49(11), 116–123.

- Saleh, F. (2021). Blockchain Without Waste: Proof-of-Stake. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Zhu, X., & Zhou, J. (2019). A Survey on Consensus Mechanisms in Blockchain. IEEE Access, 7, 110847–110866.

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423, 623–656.

- Riley, G. F., & Henderson, T. R. (2010). The NS-3 Network Simulator. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Modeling and Tools for Network Simulation (ICMTNS), 15–26. Springer.

- PowerTOP (Version 2.11) [Software]. (2014). Retrieved from https://01.org/powertop.

- Cisco Systems. (1996). Cisco NetFlow Configuration Guide. Cisco Systems.

- QGIS Development Team. (2020). QGIS Geographic Information System, Version 3.16. Retrieved from https://www.qgis.org.

- Talend. (2020). Talend Data Quality. Retrieved from https://www.talend.com.

- Ataccama. (2020). Ataccama ONE. Retrieved from https://www.ataccama.com.

- OpenRefine. (2020). OpenRefine: The Power of Data Cleaning. Retrieved from https://openrefine.org.

- Lakshman, A. , & Malik, P. (2010). Cassandra: a Decentralized Structured Storage System. In ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, 44(2), 35–40.

| Process Stage | Information Parameters |

|---|---|

| Initial Transaction | Low Informational Disorder, High Information Quality |

| Consensus Process | Increasing Informational Disorder, Variable Information Quality |

| Validated Transaction | High Informational Disorder, High Information Quality |

| Awaiting New Transaction | High Informational Disorder, Low Information Quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).